#Geoffrey the Devout

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

*screams into eternity* LOOK AT HIIIIIIMMMMMMM LOOK AT HIM MY BOY MY BABY BOY I LOVE HIM, YOU DID SUCH A GOOD JOB I'M GONNA GO CRY NOW THANK YOUUUUUU 😭💜😭💜😭💜😭💜😭

Lovingly dedicated to Geoff’s second biggest fan @justablah56 ♥️

And I guess @crazydreamer6 can also look at it

Everyone go read Lily and Honeysuckle on ao3 right now. And also Water Lily. And also First Citadel (Geoff isn’t there because he hasn’t been born yet but everyone should read it anyway)

#Friend art#My fics#Lily and honeysuckle#Geoffrey the Devout#LOOK AT MY BOOOOYYYYYY#He's so pretty#I love him#😭💜

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

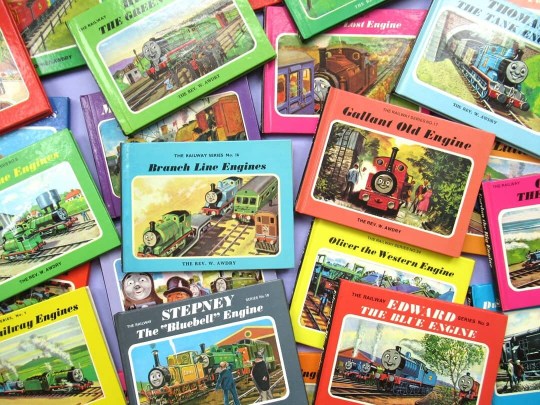

Traintober 2023: Day 17 - Holiday

How Sudrian Tourism has Evolved:

Sodor has changed majorly thanks to the publication of the Railway Series and the subsequent Television Series, both of which propelled the island and its railways from being just another part of the UK into a tourism juggernaut. But the fact of the matter is that Sodor did not immediately transform from being an insignificant island on the coast of Cumbria to one of the most popular tourist destinations in the United Kingdom overnight – so how did it all change?

To understand, we must go back to the 1500s, and the Protestant Reformation in England. At the time, Sodor was part of the English Crown – but far looser than its Irish and Welsh neighbours. Due to its small size, rough terrain and low population, King Henry VIII was far less interested in confiscating Catholic land on the island than its surrounding areas. This was in part due to the both Sir Geoffrey Regaby and Bishop Michael Colden, who managed to guide Sodor away from the Lincolnshire Rising and the Pilgrimage of Grace. Due to their remote location and general poverty, Thomas Cromwell never visited Sodor, and Cronk Abbey was never closed. For its part, St Luoc’s Cathedral at Suddery was ‘converted’ to a Protestant Cathedral in 1537, but continued holding Catholic mass. This was done by holding the two religious ceremonies one after the other.

As Sodor was now one of the few parts of the British Isles that had a Catholic church and direct line to the Papacy in Rome, it became an ‘underground’ tourist destination as a new British site of pilgrimage, frequented by Catholics looking to attend mass at the Suddery Cathedral. In return for continuing these ceremonies, Sudrians became more devout to the crown – in particular to Queen Elizabeth I, and by 1603 the Catholic mass had been all but forgotten. This did not end the attractiveness of Sodor as a religious destination, due to the caves of Saint Machan and several other holy sites that litter the island; the numbers were not large, but they did lead to a number of important connections, especially with Ireland, the Isle of Man and English ports.

The next phase of Sudrian tourism came in the 1860s, when the Skarloey Railway found the long-forgotten Skarloey lake and hidden hollow. Rather than explain it, I think I’ll just use the description that the Reverend Wilbert Awdry did:

“Spas were popular at the period and offered the possibility of a lucrative passenger business. Skarloey’s mineral springs and sheltered situation took hold on the minds of some members of the Board, among them Shamus Tebroc who conceived the idea of developing Skarloey as a spa. An hotel and a number of villas were built as a speculation, and the gravity worked incline which had been installed for the conveyance of materials was retained and up-graded for coals, merchandise, and passengers’ luggage.”

Skarloey became the first of the Island of Sodor’s tourist hotspots, especially due to its proximity to Culdee Fell and Saint Machan’s cave. The popularity of the spas was good for a time, but began to fall off as the bad fortunes of the Sodor & Mainland Railway continuously hurt the Skarloey Railway’s tourism campaign with delayed and cancelled trains, ratty carriages and even standoffish staff. This led to Skarloey becoming a local holiday destination instead, but even that began to slow down as WWII loomed.

On the other side of the island, the Mid Sodor Railway also began heavily advertising their railway to holidaymakers across the UK, but to a somewhat better result. The Isle of Man Steam Packet contract the railway picked up led to a large influx of tourists across the late 1800s and early 1900s, up until the 1920s. The railway’s ability to reach the walled city of Peel Godred and the cave of Saint Machan (via the Culdee Fell Railway) made it a very attractive destination for tourists, though this would change at the end of WWI.

The advent of relatively cheap international travel via ferries in the 1920s did a lot of damage to Sodor’s tourism economy, as their major markets in England preferred to travel to either the Continent or the Lake District – or even as far afield as the United States. Sodor instead switched to being primarily an agricultural and resource-extraction economy, with some manufacturing. This continued throughout WWII.

Which leads us to May 12th, 1945. The Three Railway Engines was published – in colour – in the UK. It achieved enough success to lead to the continuation of the series in 1946, and again in 1948, and then again continuously until 1972. These twenty-seven years’ worth of publicity for the island and its railways had a massive effect. Skarloey was rediscovered and the budget-conscience holiday maker of the 1960s chose it for its low prices, high quality, and picturesque scenery, turning around the railways needed to reach it. The Culdee Fell Railway also saw an uptick in traffic as the Peel Godred Railway brought in more passengers than the old Mid Sodor Railway had.

Furthermore, tourists came to see the engines, a phenomenon not seen before in the island’s tourism industry. Insignificant towns such as Dryaw, Brendam, Crosby and Glennock became infinitely more popular as the sites of incidents in the Railway Series, or as convenient locations to stay for travelling the island. The biggest success story of the island’s cities was Cronk however. Cronk grew massively from the tourism trade as the most central location on the NWR to reach the various tourist destinations of Sodor – even Awdry takes a moment to mention ‘The Crown of Sodor’ Hotel on Sigmund Street due to its prominence as a hotel on the island.

This large influx of tourists was however of a majorly local source – the UK, parts of continental Europe and a relatively low number from North America. It wasn’t until the advent of cheap international jetplane flights in the mid-1970s and the debut of the TV series on October 9, 1984.

This debut is what changed everything.

The Thomas and Friends Television series was an international success, with translations into a number of languages (eleven by Wikipedia’s count) and broadcast around the globe. This, coupled with the opening of an enlarged airport at Vicarstown (which had been constructed in 1941 by the RAF and expanded by Vickers in the 1960s. The airport itself had been bought by the NWR in 1982 (probably in anticipation of the TV series) and began receiving jetliners from across the world as early as 1986.

Today, Sudrian tourism is one of the largest income producers in northern England due to its international status crafted by the Thomas & Friends series. The island is a popular tourist attraction for both railfans and Thomas fans, as well as religious pilgrims, spa enthusiasts, hikers, ramblers and historians. The airport at Vicarstown has been linked into the NWR via a spur line, and more recently a number of signs on the island have been converted to include secondary and tertiary languages, for better interpretation.

Sodor reached its best numbers for international tourists in 2019, when over 1.5 million people visited the island, making it the third most visited tourist destination within England, beating out Birmingham. The secret to it’s recent further uptick in visitors is the opening of a number of museums, galleries and other cultural sites on the island, as well as a strong advertising campaign that focused on the island’s major tourist draws, which are:

The North Western Railway, Skarloey Railway, Culdee Fell Railway and Arlesdale Railway from the Railway Series book and subsequent Television series

A pre-Norman era Abbey at Cronk, one of the oldest of its kind in Britain

Suddery Cathedral, which continues to be one of the few remaining pre-reformation cathedrals in Britain

Several Norman-era castles, including a completely intact castle at Harwick

The Walled City of Peel Godred

The caves of Saint Machan

Culdee Fell

Henry's Forest National Park

Skarloey and its spas

Museums, galleries, and cultural centres

The Standing Stones of Killdane.

This advertising campaign brought a greater variety of tourists to the island, especially those from North America.

The island was badly affected by the advent of the Coronavirus pandemic, which saw the high tourist numbers of the previous decade prop by over eighty percent, which forced the island to once again consider restructuring their economy around agriculture, manufacturing, and resource extraction. This eventually was decided against, as tourist numbers have slowly picked back up through 2022.

Sodor has been greatly affected by its rise to one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the UK, including a number of hotels being built on the island – many of which are converted manorhouses – as well as several upgrades made to the transport systems of the island, with updated ferry services between the island’s major ports and locations in the UK and Ireland, as well as the railway building a special line to the island’s main airport, new tram and bus services within the major cities on the island. The island’s railway system has also seen upgrades throughout the latter half of the 20th century, including a third track being added to the mainline, new signalling systems and a number of extra connecting services to cities in the UK, such as Manchester, Birmingham, Carlisle and Preston.

Sodor has grown drastically as a result of its tourism industry and is today an international tourism hotspot. The island continues to be popular into the modern day, as a result of strong advertising and a pointed diversification of tourist offerings on the island to help the island’s tourism industry grow and bring in profits for the island’s people.

Back to Master Post

#fanfiction writer#weirdowithaquill#railway series#thomas the tank engine#railways#RWS analysis#Thomas and friends analysis#island of sodor#tourism#mid sodor railway#skarloey railway#traintober 2023#traintober

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prester John came up in conversation on the way to a local Medieval reenactment village and it put me in mind of a somewhat ancient piece of medieval nerd shit on the internet:

TO: GEOFFREY CHAUCER ([email protected])

FROM: ABALIA OF SUSA ([email protected])

RE: MAIL ORDER BRIDE FROM THE REAUME OF PRESTER JOHN

Good daye! Ich ben ycleped Abalia. XXVII yeeres haue ich dwelt yn thys worlde, far awey yn the lande of Prester John, yn Inde, wher the riveres of paradise do flowe ynto a see of gravel. Althogh thys be a fayre contree ful of precious stones and tables ymade of solid emeralde, wher even the tiniest tchotchke ys ycrafted of diamonde (seriouslie, ich haue an adamantine shoe-horne), yet ther are fewe worthy men that dwelle herein. In deed, a lord hight Gatholonabes doth convince alle the yonge men for to joyne his cult of Assasines and they spende ther tyme lernynge to kille silentlye and hide in shadowes. And thus no gentil man ys lefte for a yonge damosel swich as myn selfe, save for the wilde menne of the deserte who haue hornes of beestes and speke no human tongue, and thatte ys juste totallie nastie and gross. Perhaps yt semeth nyce to yow, but ich devoutely wisshe to fynde the blessinges of love matrimoniale! Ich do looke for a man riche nat wyth worldlie goodes, but riche yn corage and vertu, and thus ich haue emailed yow. If liketh yow my message, and ye haue nat hornes and be nat an assasin, may it plese yow to sende an replye to me at [email protected].

Source: Geoffrey Chaucer Hath a Blog

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Development of Arthur - Geoffrey of Monmouth

1138 - Historia regum Britanniae and 1150 - Vita Merlini, by Geoffrey of Monmouth

Physical appearance

In battle, wore "a golden helmet with the carved likeness of a dragon upon the crest"

Carried the shield Pridwen, "which had the image of blessed Mary, Mother of God, painted upon it, keeping him always mindful of her"

Wielded Caliburn, "greatest of swords, which had been made in the isle of Avalon"

In his right hand during battle, carried the spear known as Ron, "long and broad and keen in warfare"

Personality

At 15 years old, described as "a youth of outstanding virtue and largesse. His innate goodness made him exhibit such grace that he was beloved by all the people". Possessed "both great courage and generosity".

"Such an outstanding man that no one could match him in virtue" according to Merlin

Takes counsel from advisors and vassals, listens to them, takes their advice into consideration.

Willing to engage in mercy if asked sufficiently, but more inclined to mercilessness as a default, and swift to punish treachery. E.g.: let the surrendering Saxons go back to Germany, then hanged all the Saxon hostages when the Saxons turned back around and attacked the Briton countryside. E.g.: had made the decision to let none of the Picts and Scots live, but the bishops and clergy of those lands approached him and begged for mercy, such that "pity finally moved him to tears".

Fierce fighter and battle-leader, even at a young age, often even rushing into the front lines to inspire and rally the troops and successfully killing… lots of men. (470, in one of his first campaigns.)

Loyal and protective of his vassals.

Rejoiced at being universally feared after his conquests, and desired to "submit all Europe to his rule", so he conquered Norway, Denmark, and Gaul (over the course of a 9-year campaign). Eventually also fought and defeated the forces of Rome (though didn't get to conquer all of Rome due to Mordred interrupting by taking over Britain).

Unhesitant to accept single combat, and would even seek out challenges (for example, fighting two different giants in single combat and winning). "For King Arthur possessed such strength and courage that he scoffed at bringing the entire army against such monsters. He wanted to impress his men by vanquishing the creature himself" and so would do stuff like get Bedivere and Kay to steal away with him so he can fight a giant in single combat

Eloquent and well-spoken, able to give speeches "bedecked with a truly Ciceronian eloquence".

Intelligent and well-educated.

Had a portentous dream (about a dragon and bear fighting), not very good at interpreting it though.

Reasonably devout Christian.

Family

Wife: Guinevere, "from a noble Roman family", who had been brought up in the household of Duke Cador of Cornwall and "surpassed all the other women of the isle in beauty."

Mother: Igerna, married to Gorlois the duke of Cornwall when Arthur was conceived. Her "beauty surpassed that of all the other women of Britain".

Father: Uther Pendragon, who was disguised as Gorlois when Arthur was conceived, then later married Igerna after Gorlois' death. Poisoned to death by the Saxons after defeating them. Buried in Stonehenge (the "Ring of Giants") next to his brother Aurelius.

Sister: Anna, "whose sons and grandsons will later rule the kingdom of Britain" per Merlin's prophecy. Married Loth of Lothian, lord of Leis, "a most experienced soldier, wise and mature".

Another sister? Possibly a half-sister from Igerna and Gorlois? Unclear and unnamed, but married Budicus the king of the Armorican Britons over in what's now part of France.

Nephew: Hoel, king of the Armorican Britons. Arthur and Hoel were very fond of one another, "united by love and a common blood", and Hoel was a strong ally. Arthur dropped everything to rally to his rescue when he was ill and besieged, and they showed affection to each other more than Arthur is described as doing with anyone else in Geoffrey's narrative. (I get the sense based on the timeline and interactions that they're of similar ages, but I don't have evidence of that.)

Nephew: Gawain, son of Loth of Lothian and Arthur's sister Anna.

Nephew: Mordred, son of Loth of Lothian and Arthur's sister Anna.

Brother-in-law: Loth of Lothian, Earl of Lothian and King of Norway

Paternal uncle: Constans, eldest brother of Uther, prior king of Britain before Vortigern and Vortimer, former monk, puppet of Vortigern, deceased before Arthur's birth.

Paternal uncle: Aurelius Ambrosius, older brother of Uther, prior king of Britain after Vortigern and before Uther, deceased before Arthur's birth.

Grandfather: Constantine, king of Britain before Constans, deceased before Arthur's birth

Grandmother: Unnamed woman from a noble family "who Guithelin had personally raised"

Timeline

Arthur's birth prophesied by Merlin to Uther, along with the birth of his sister Anna.

Conceived at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall when Uther lay with Igerna while disguised by Merlin as her husband Gorlois, who he was at war with at the time (because he wanted Igerna).

Uther and Igerna marry shortly thereafter, as Gorlois died in battle while Uther and Igerna were conceiving Arthur. They "lived together as equals bound by mutual affection".

Arthur's sister Anna is born to Uther and Igerna.

Uther becomes ill and places Loth of Lothian in charge of the armies to fight the invading Saxons. Uther is carried in a litter to command the battle when Loth is unable to command the Britons successfully, manages to mostly succeed until the Saxons assassinate him by poisoning a spring.

The leaders of the various provinces of Britain ask Archbishop Dubricius of Caerleon to crown 15-year-old Arthur as king.

Arthur "upheld the ancient custom" of gift-giving to soldiers who joined him until he ran began to run out of gifts, so then he attacked the Saxons to distribute their riches among his men.

Drove out the Saxons, then also the Picts, Scots, and Irish from Britain (the Britain of the time, which is now Wales and some of England).

Rebuilt the churches that the Saxons had destroyed.

Married Guinevere.

Subdued Ireland and Iceland, and then the kings of Gotland and Orkney surrendered to him before they could get invaded.

12 years of peace, during which Arthur invited "all the bravest men from the farflung reaches of his domain to join his household," and cultivated "such refinement in his court so that people far and wide sought to emulate it," and "every young nobleman was tempted to hang himself unless he could dress or bear arms like the knights of King Arthur's court".

Possibly around this time is when Arthur fights the giant Retho atop Mount Aravius, when Retho challenges him to single combat to add to Retho's kingly beard collection? (Retho was collecting beards of kings to make a fur coat.) Timeline is unclear here.

Conquers Norway and Denmark. Establishes Loth as king.

Spends 9 years conquering Gaul, holds court at Paris, gives Neudtria (Normandy) to Bedivere and gives the province of Anjou to Kay.

Big fancy feast/tournament/celebration at Caerlon, is ceremoniously bestowed the royal crown. Rome sends a delegation to threaten Britain, tell Arthur to come to Rome in August, and that Britain still owes Rome tribute. The Britons are outraged, Arthur tells Rome they should give Britain tribute instead.

Rome advances towards Britain. Arthur leaves Britain under custodianship of Mordred and Guinevere and invades Rome.

Arthur sneaks off with Bedivere and Kay to fight and kill an unnamed giant in single combat while waiting in Gaul for the rest of his armies to arrive.

The Britons defeat the Roman forces somewhere between Paris and Rome. Arthur winters in the Allobroges, continuing to conquer the area, and wants to cross the mountains to invade Rome when summer comes.

Arthur receives word that Mordred has "proven himself to be a tyrant and a traitor", seized the throne of Britain, and "now took his wicked pleasure with Guinevere, who had broken her marriage vows".

Arthur returns to Britain and wages war against Mordred, who's allied with the Scots, Picts, Irish, and Saxons. Guinevere joins the nuns at a church in Caerleon when hearing of Arthur's arrival and victories.

~542 C.E.: Battle of Camlann. Mordred is killed Arthur is carried off by Merlin, Barinthus, and maybe others to Avalon to be healed by Morgen. Constantine, son of Duke Cador of Cornwall, becomes king.

Other notes

"The Boar of Cornwall" in Merlin's prophecies refers to Arthur.

Most described court events were at Tintagel or Caerleon.

Merlin does not show up in Arthur's story after his conception. In "The Life of Merlin", Merlin implies that he helped bring Arthur's body to Avalon as well.

#geoffrey of monmouth#resources#arthurian character development#arthuriana#arthurian literature#arthurian development - arthur#vita merlini#historia regum britanniae#arthur#mordred#guinevere#merlin#arthurian development - historia regum britanniae#arthurian development - vita merlini#might adjust these tags later as I refine this project

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

January 5th: Pope Clement VII Says No

Henry the VIII should be a name that most recognize, thanks to him being the reason that England split from the church and him having six wives. (Thank you Broadway musical SIX for being entertaining as well as a good look into history in a fun way.) But what event caused the split, or is at least attributed by many to cause the split? Well, Pope Clement VII specifically forbidding Henry from divorcing his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

From an American stand point, Henry is played out to be a horrible man who is more worried about getting an heir to the throne, and blaming his wives for not helping him with that, thus going out and trying to find a woman who will give birth to a “legitimate” heir. I’m going to say this first, I still don’t think he’s a good guy….he just doesn’t seem to be as terrible as the American education system plays him out to be based on the research I’ve done for this episode. I could be totally wrong though.

Anyway, the basic story goes that Henry was concerned by his failure to produce a legitimate heir, and wanted to find a way to end his marriage in a manner consistent with his faith. Doing so was extremely important for political reasons as if he had violated Catholic doctrine, he risked disgrace and condemnation by the pope. It’s actually been recorded that Henry was a fairly devout Catholic; he had believed his marriage was against the biblical injunction forbidding marriage with a brothers widow.

That didn’t exactly go as planned; Clement said no in a letter on January 5th, 1531. Though Clement most likely would have done so if it weren’t for the fact that Clement was scared of Charles V, current Holy Roman Emperor. How does Charles play into this? Well….Catherine was his aunt, and Charles had strong feelings of familial honor and barred any concession to Henry’s Wishes. Due to Charles role into the issue, and with Clement being former literal prisoner in 1527-28 of Charles, he never dared resist him in any form after.

Henry’s attempt to break his marriage legally were pretty much doomed from the start unfortunately. Which, as we all know, did not exactly stop him from continuing on. Though he did not want to due to the fact he knew it would lead to excommunication, and meaning supporting Martin Luther who he despised, he decided to send Catherine off and marry Anne Boleyn.

Though he was separated from the Catholic Church and the Church of England now took it’s place, Henry prided himself on his learnings and gave much time and thought into the new religious structure. With the exception of a pope in the system, he didn’t give up on many of the main tenets of which he grew up with.

Sources:

Michael de Ferdinandy. “Charles v | Biography, Reign, Abdication, & Facts.” In Encyclopædia Britannica, February 20, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-V-Holy-Roman-emperor. Morrill, John S, and Geoffrey R Elton. “Henry VIII | Biography, Wives, & Facts.” In Encyclopædia Britannica, August 17, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Henry-VIII-king-of-England.

0 notes

Text

The Canterbury Tales: General Prologue

By Geoffrey Chaucer

Here bygynneth the Book of the tales of Caunterbury

Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote, The droghte of March hath perced to the roote, And bathed every veyne in swich licóur Of which vert�� engendred is the flour; Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth Inspired hath in every holt and heeth The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne Hath in the Ram his halfe cours y-ronne, And smale foweles maken melodye, That slepen al the nyght with open ye, So priketh hem Natúre in hir corages, Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages, And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes, To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes; And specially, from every shires ende Of Engelond, to Caunterbury they wende, The hooly blisful martir for to seke, That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

Bifil that in that seson on a day, In Southwerk at the Tabard as I lay, Redy to wenden on my pilgrymage To Caunterbury with ful devout corage, At nyght were come into that hostelrye Wel nyne and twenty in a compaignye Of sondry folk, by áventure y-falle In felaweshipe, and pilgrimes were they alle, That toward Caunterbury wolden ryde. The chambres and the stables weren wyde, And wel we weren esed atte beste. And shortly, whan the sonne was to reste, So hadde I spoken with hem everychon, That I was of hir felaweshipe anon, And made forward erly for to ryse, To take oure wey, ther as I yow devyse.

But nathelees, whil I have tyme and space, Er that I ferther in this tale pace, Me thynketh it acordaunt to resoun To telle yow al the condicioun Of ech of hem, so as it semed me, And whiche they weren and of what degree, And eek in what array that they were inne; And at a Knyght than wol I first bigynne.

A Knyght ther was, and that a worthy man, That fro the tyme that he first bigan To riden out, he loved chivalrie, Trouthe and honóur, fredom and curteisie. Ful worthy was he in his lordes werre, And thereto hadde he riden, no man ferre, As wel in cristendom as in hethenesse, And evere honóured for his worthynesse. At Alisaundre he was whan it was wonne; Ful ofte tyme he hadde the bord bigonne Aboven alle nacions in Pruce. In Lettow hadde he reysed and in Ruce,— No cristen man so ofte of his degree. In Gernade at the seege eek hadde he be Of Algezir, and riden in Belmarye. At Lyeys was he, and at Satalye, Whan they were wonne; and in the Grete See At many a noble armee hadde he be.

At mortal batailles hadde he been fiftene, And foughten for oure feith at Tramyssene In lyste thries, and ay slayn his foo. This ilke worthy knyght hadde been also Somtyme with the lord of Palatye Agayn another hethen in Turkye; And evermoore he hadde a sovereyn prys. And though that he were worthy, he was wys, And of his port as meeke as is a mayde. He nevere yet no vileynye ne sayde, In al his lyf, unto no maner wight. He was a verray, parfit, gentil knyght.

But for to tellen yow of his array, His hors weren goode, but he was nat gay; Of fustian he wered a gypon Al bismótered with his habergeon; For he was late y-come from his viage, And wente for to doon his pilgrymage.

With hym ther was his sone, a yong Squiér, A lovyere and a lusty bacheler, With lokkes crulle as they were leyd in presse. Of twenty yeer of age he was, I gesse. Of his statúre he was of evene lengthe, And wonderly delyvere and of greet strengthe. And he hadde been somtyme in chyvachie In Flaundres, in Artoys, and Pycardie, And born hym weel, as of so litel space, In hope to stonden in his lady grace. Embrouded was he, as it were a meede Al ful of fresshe floures whyte and reede. Syngynge he was, or floytynge, al the day; He was as fressh as is the month of May. Short was his gowne, with sleves longe and wyde; Wel koude he sitte on hors and faire ryde; He koude songes make and wel endite, Juste and eek daunce, and weel purtreye and write. So hoote he lovede that by nyghtertale He sleep namoore than dooth a nyghtyngale. Curteis he was, lowely and servysáble, And carf biforn his fader at the table.

A Yeman hadde he and servántz namo At that tyme, for hym liste ride soo; And he was clad in cote and hood of grene. A sheef of pecock arwes bright and kene, Under his belt he bar ful thriftily— Wel koude he dresse his takel yemanly; His arwes drouped noght with fetheres lowe— And in his hand he baar a myghty bowe. A not-heed hadde he, with a broun viságe. Of woodecraft wel koude he al the uságe. Upon his arm he baar a gay bracér, And by his syde a swerd and a bokeler, And on that oother syde a gay daggere, Harneised wel and sharp as point of spere; A Cristophere on his brest of silver sheene. An horn he bar, the bawdryk was of grene. A forster was he, soothly as I gesse.

Ther was also a Nonne, a Prioresse, That of hir smylyng was ful symple and coy; Hire gretteste ooth was but by seinte Loy, And she was cleped madame Eglentyne. Ful weel she soong the service dyvyne, Entuned in hir nose ful semely; And Frenssh she spak ful faire and fetisly, After the scole of Stratford atte Bowe, For Frenssh of Parys was to hire unknowe. At mete wel y-taught was she with-alle: She leet no morsel from hir lippes falle, Ne wette hir fyngres in hir sauce depe. Wel koude she carie a morsel and wel kepe Thát no drope ne fille upon hire brist; In curteisie was set ful muchel hir list. Hire over-lippe wyped she so clene That in hir coppe ther was no ferthyng sene Of grece, whan she dronken hadde hir draughte. Ful semely after hir mete she raughte. And sikerly she was of greet desport, And ful plesáunt and amyable of port, And peyned hire to countrefete cheere Of court, and been estatlich of manere, And to ben holden digne of reverence. But for to speken of hire conscience, She was so charitable and so pitous She wolde wepe if that she saugh a mous Kaught in a trappe, if it were deed or bledde. Of smale houndes hadde she, that she fedde With rosted flessh, or milk and wastel breed; But soore wepte she if oon of hem were deed, Or if men smoot it with a yerde smerte; And al was conscience and tendre herte.

Ful semyly hir wympul pynched was; Hire nose tretys, her eyen greye as glas, Hir mouth ful smal and ther-to softe and reed; But sikerly she hadde a fair forheed; It was almoost a spanne brood, I trowe; For, hardily, she was nat undergrowe. Ful fetys was hir cloke, as I was war; Of smal coral aboute hire arm she bar A peire of bedes, gauded al with grene, And ther-on heng a brooch of gold ful sheene, On which ther was first write a crowned A, And after, Amor vincit omnia.

Another Nonne with hire hadde she, That was hire chapeleyne, and Preestes thre.

A Monk ther was, a fair for the maistrie, An outridere, that lovede venerie; A manly man, to been an abbot able. Ful many a deyntee hors hadde he in stable; And whan he rood, men myghte his brydel heere Gýnglen in a whistlynge wynd als cleere, And eek as loude, as dooth the chapel belle, Ther as this lord was kepere of the celle. The reule of seint Maure or of seint Beneit, By-cause that it was old and som-del streit,— This ilke Monk leet olde thynges pace, And heeld after the newe world the space. He yaf nat of that text a pulled hen That seith that hunters ben nat hooly men, Ne that a monk, whan he is recchelees, Is likned til a fissh that is waterlees,— This is to seyn, a monk out of his cloystre. But thilke text heeld he nat worth an oystre; And I seyde his opinioun was good. What sholde he studie and make hymselven wood, Upon a book in cloystre alwey to poure, Or swynken with his handes and labóure, As Austyn bit? How shal the world be served? Lat Austyn have his swynk to him reserved. Therfore he was a prikasour aright: Grehoundes he hadde, as swift as fowel in flight; Of prikyng and of huntyng for the hare Was al his lust, for no cost wolde he spare. I seigh his sleves y-púrfiled at the hond With grys, and that the fyneste of a lond; And for to festne his hood under his chyn He hadde of gold y-wroght a curious pyn; A love-knotte in the gretter ende ther was. His heed was balled, that shoon as any glas, And eek his face, as he hadde been enoynt. He was a lord ful fat and in good poynt; His eyen stepe, and rollynge in his heed, That stemed as a forneys of a leed; His bootes souple, his hors in greet estaat. Now certeinly he was a fair prelaat. He was nat pale, as a forpyned goost: A fat swan loved he best of any roost. His palfrey was as broun as is a berye.

A Frere ther was, a wantowne and a merye, A lymytour, a ful solémpne man. In alle the ordres foure is noon that kan So muchel of daliaunce and fair langage. He hadde maad ful many a mariage Of yonge wommen at his owene cost. Unto his ordre he was a noble post. Ful wel biloved and famulier was he With frankeleyns over al in his contree, And eek with worthy wommen of the toun; For he hadde power of confessioun, As seyde hym-self, moore than a curát, For of his ordre he was licenciat. Ful swetely herde he confessioun, And plesaunt was his absolucioun. He was an esy man to yeve penaunce There as he wiste to have a good pitaunce; For unto a povre ordre for to yive Is signe that a man is wel y-shryve; For, if he yaf, he dorste make avaunt He wiste that a man was répentaunt; For many a man so hard is of his herte He may nat wepe al-thogh hym soore smerte. Therfore in stede of wepynge and preyéres Men moote yeve silver to the povre freres. His typet was ay farsed full of knyves And pynnes, for to yeven faire wyves. And certeinly he hadde a murye note: Wel koude he synge and pleyen on a rote; Of yeddynges he baar outrely the pris. His nekke whit was as the flour-de-lys; Ther-to he strong was as a champioun. He knew the tavernes wel in every toun, And everich hostiler and tappestere Bet than a lazar or a beggestere; For unto swich a worthy man as he Acorded nat, as by his facultee, To have with sike lazars aqueyntaunce; It is nat honest, it may nat avaunce Fór to deelen with no swich poraille, But al with riche and selleres of vitaille. And over-al, ther as profit sholde arise, Curteis he was and lowely of servyse. Ther nas no man nowher so vertuous. He was the beste beggere in his hous; [And yaf a certeyn ferme for the graunt, Noon of his brethren cam ther in his haunt;] For thogh a wydwe hadde noght a sho, So plesaunt was his In principio, Yet wolde he have a ferthyng er he wente: His purchas was wel bettre than his rente. And rage he koude, as it were right a whelpe. In love-dayes ther koude he muchel helpe, For there he was nat lyk a cloysterer With a thredbare cope, as is a povre scolér, But he was lyk a maister, or a pope; Of double worstede was his semycope, That rounded as a belle, out of the presse. Somwhat he lipsed for his wantownesse, To make his Englissh sweete upon his tonge; And in his harpyng, whan that he hadde songe, His eyen twynkled in his heed aryght As doon the sterres in the frosty nyght. This worthy lymytour was cleped Hubérd.

A Marchant was ther with a forked berd, In motteleye, and hye on horse he sat; Upon his heed a Flaundryssh bevere hat; His bootes clasped faire and fetisly. His resons he spak ful solémpnely, Sownynge alway thencrees of his wynnyng. He wolde the see were kept for any thing Bitwixe Middelburgh and Orewelle. Wel koude he in eschaunge sheeldes selle. This worthy man ful wel his wit bisette; Ther wiste no wight that he was in dette, So estatly was he of his gouvernaunce, With his bargaynes and with his chevyssaunce. For sothe he was a worthy man with-alle, But, sooth to seyn, I noot how men hym calle.

A Clerk ther was of Oxenford also, That unto logyk hadde longe y-go. As leene was his hors as is a rake, And he nas nat right fat, I undertake, But looked holwe, and ther-to sobrely. Ful thredbare was his overeste courtepy; For he hadde geten hym yet no benefice, Ne was so worldly for to have office; For hym was lévere háve at his beddes heed Twénty bookes, clad in blak or reed, Of Aristotle and his philosophie, Than robes riche, or fíthele, or gay sautrie. But al be that he was a philosophre, Yet hadde he but litel gold in cofre; But al that he myghte of his freendes hente On bookes and on lernynge he it spente, And bisily gan for the soules preye Of hem that yaf hym wher-with to scoleye. Of studie took he moost cure and moost heede. Noght o word spak he moore than was neede; And that was seyd in forme and reverence, And short and quyk and ful of hy senténce. Sownynge in moral vertu was his speche; And gladly wolde he lerne and gladly teche.

A Sergeant of the Lawe, war and wys, That often hadde been at the Parvys, Ther was also, ful riche of excellence. Discreet he was, and of greet reverence— He semed swich, his wordes weren so wise. Justice he was ful often in assise, By patente, and by pleyn commissioun. For his science and for his heigh renoun, Of fees and robes hadde he many oon. So greet a purchasour was nowher noon: Al was fee symple to hym in effect; His purchasyng myghte nat been infect. Nowher so bisy a man as he ther nas, And yet he semed bisier than he was. In termes hadde he caas and doomes alle That from the tyme of kyng William were falle. Ther-to he koude endite and make a thyng, Ther koude no wight pynche at his writyng; And every statut koude he pleyn by rote. He rood but hoomly in a medlee cote, Girt with a ceint of silk, with barres smale; Of his array telle I no lenger tale.

A Frankeleyn was in his compaignye. Whit was his berd as is the dayesye; Of his complexioun he was sangwyn. Wel loved he by the morwe a sop in wyn; To lyven in delit was evere his wone, For he was Epicurus owene sone, That heeld opinioun that pleyn delit Was verraily felicitee parfit. An housholdere, and that a greet, was he; Seint Julian he was in his contree. His breed, his ale, was alweys after oon; A bettre envyned man was nowher noon. Withoute bake mete was nevere his hous, Of fissh and flessh, and that so plentevous, It snewed in his hous of mete and drynke, Of alle deyntees that men koude thynke, After the sondry sesons of the yeer; So chaunged he his mete and his soper. Ful many a fat partrich hadde he in muwe, And many a breem and many a luce in stuwe. Wo was his cook but if his sauce were Poynaunt and sharp, and redy al his geere. His table dormant in his halle alway Stood redy covered al the longe day. At sessiouns ther was he lord and sire; Ful ofte tyme he was knyght of the shire. An anlaas, and a gipser al of silk, Heeng at his girdel, whit as morne milk. A shirreve hadde he been, and a countour; Was nowher such a worthy vavasour.

An Haberdasshere, and a Carpenter, A Webbe, a Dyere, and a Tapycer,— And they were clothed alle in o lyveree Of a solémpne and a greet fraternitee. Ful fressh and newe hir geere apiked was; Hir knyves were chaped noght with bras, But al with silver; wroght ful clene and weel Hire girdles and hir pouches everydeel. Wel semed ech of hem a fair burgeys To sitten in a yeldehalle, on a deys. Éverich, for the wisdom that he kan, Was shaply for to been an alderman; For catel hadde they ynogh and rente, And eek hir wyves wolde it wel assente, And elles certeyn were they to blame. It is ful fair to been y-cleped Madame, And goon to vigilies al bifore, And have a mantel roialliche y-bore.

A Cook they hadde with hem for the nones, To boille the chiknes with the marybones, And poudre-marchant tart, and galyngale. Wel koude he knowe a draughte of Londoun ale. He koude rooste, and sethe, and broille, and frye, Máken mortreux, and wel bake a pye. But greet harm was it, as it thoughte me, That on his shyne a mormal hadde he; For blankmanger, that made he with the beste.

A Shipman was ther, wonynge fer by weste; For aught I woot he was of Dertemouthe. He rood upon a rouncy, as he kouthe, In a gowne of faldyng to the knee. A daggere hangynge on a laas hadde he Aboute his nekke, under his arm adoun. The hoote somer hadde maad his hewe al broun; And certeinly he was a good felawe. Ful many a draughte of wyn hadde he y-drawe Fro Burdeux-ward, whil that the chapman sleep. Of nyce conscience took he no keep. If that he faught and hadde the hyer hond, By water he sente hem hoom to every lond. But of his craft to rekene wel his tydes, His stremes, and his daungers hym bisides, His herberwe and his moone, his lode-menage, Ther nas noon swich from Hulle to Cartage. Hardy he was and wys to undertake; With many a tempest hadde his berd been shake. He knew alle the havenes, as they were, From Gootlond to the Cape of Fynystere, And every cryke in Britaigne and in Spayne. His barge y-cleped was the Maudelayne.

With us ther was a Doctour of Phisik; In all this world ne was ther noon hym lik, To speke of phisik and of surgerye; For he was grounded in astronomye. He kepte his pacient a ful greet deel In houres, by his magyk natureel. Wel koude he fortunen the ascendent Of his ymáges for his pacient. He knew the cause of everich maladye, Were it of hoot, or cold, or moyste, or drye, And where they engendred and of what humour. He was a verray, parfit praktisour; The cause y-knowe, and of his harm the roote, Anon he yaf the sike man his boote. Ful redy hadde he his apothecaries To sende him drogges and his letuaries; For ech of hem made oother for to wynne, Hir frendshipe nas nat newe to bigynne. Wel knew he the olde Esculapius, And De{"y}scorides, and eek Rufus, Old Ypocras, Haly, and Galyen, Serapion, Razis, and Avycen, Averrois, Damascien, and Constantyn, Bernard, and Gatesden, and Gilbertyn. Of his diete mesurable was he, For it was of no superfluitee, But of greet norissyng and digestíble. His studie was but litel on the Bible. In sangwyn and in pers he clad was al, Lyned with taffata and with sendal. And yet he was but esy of dispence; He kepte that he wan in pestilence. For gold in phisik is a cordial; Therfore he lovede gold in special.

A Good Wif was ther of biside Bathe, But she was som-del deef, and that was scathe. Of clooth-makyng she hadde swich an haunt She passed hem of Ypres and of Gaunt. In al the parisshe wif ne was ther noon That to the offrynge bifore hire sholde goon; And if ther dide, certeyn so wrooth was she That she was out of alle charitee. Hir coverchiefs ful fyne weren of ground; I dorste swere they weyeden ten pound That on a Sonday weren upon hir heed. Hir hosen weren of fyn scarlet reed, Ful streite y-teyd, and shoes ful moyste and newe. Boold was hir face, and fair, and reed of hewe. She was a worthy womman al hir lyve; Housbondes at chirche dore she hadde fyve, Withouten oother compaignye in youthe; But ther-of nedeth nat to speke as nowthe. And thries hadde she been at Jérusalem; She hadde passed many a straunge strem; At Rome she hadde been, and at Boloigne, In Galice at Seint Jame, and at Coloigne. She koude muchel of wandrynge by the weye. Gat-tothed was she, soothly for to seye. Upon an amblere esily she sat, Y-wympled wel, and on hir heed an hat As brood as is a bokeler or a targe; A foot-mantel aboute hir hipes large, And on hire feet a paire of spores sharpe. In felaweshipe wel koude she laughe and carpe; Of remedies of love she knew per chauncé, For she koude of that art the olde daunce.

A good man was ther of religioun, And was a povre Person of a Toun; But riche he was of hooly thoght and werk. He was also a lerned man, a clerk, That Cristes Gospel trewely wolde preche; His parisshens devoutly wolde he teche. Benygne he was, and wonder diligent, And in adversitee ful pacient; And swich he was y-preved ofte sithes. Ful looth were hym to cursen for his tithes, But rather wolde he yeven, out of doute, Unto his povre parisshens aboute, Of his offrýng and eek of his substaunce; He koude in litel thyng have suffisaunce. Wyd was his parisshe, and houses fer asonder, But he ne lafte nat, for reyn ne thonder, In siknesse nor in meschief to visíte The ferreste in his parisshe, muche and lite, Upon his feet, and in his hand a staf. This noble ensample to his sheep he yaf, That first he wroghte and afterward he taughte. Out of the gospel he tho wordes caughte; And this figure he added eek therto, That if gold ruste, what shal iren doo? For if a preest be foul, on whom we truste, No wonder is a lewed man to ruste; And shame it is, if a prest take keep, A shiten shepherde and a clene sheep. Wel oghte a preest ensample for to yive By his clennesse how that his sheep sholde lyve. He sette nat his benefice to hyre And leet his sheep encombred in the myre, And ran to Londoun, unto Seinte Poules, To seken hym a chaunterie for soules, Or with a bretherhed to been withholde; But dwelte at hoom and kepte wel his folde, So that the wolf ne made it nat myscarie; He was a shepherde, and noght a mercenarie. And though he hooly were and vertuous, He was to synful man nat despitous, Ne of his speche daungerous ne digne, But in his techyng díscreet and benygne. To drawen folk to hevene by fairnesse, By good ensample, this was his bisynesse. But it were any persone obstinat, What so he were, of heigh or lough estat, Hym wolde he snybben sharply for the nonys. A bettre preest I trowe that nowher noon ys. He waited after no pompe and reverence, Ne maked him a spiced conscience; But Cristes loore and his apostles twelve He taughte, but first he folwed it hymselve.

With hym ther was a Plowman, was his brother, That hadde y-lad of dong ful many a fother; A trewe swynkere and a good was he, Lyvynge in pees and parfit charitee. God loved he best, with al his hoole herte, At alle tymes, thogh him gamed or smerte. And thanne his neighebor right as hymselve. He wolde thresshe, and therto dyke and delve, For Cristes sake, for every povre wight, Withouten hire, if it lay in his myght. His tithes payede he ful faire and wel, Bothe of his propre swynk and his catel. In a tabard he rood upon a mere.

Ther was also a Reve and a Millere, A Somnour and a Pardoner also, A Maunciple, and myself,—ther were namo.

The Millere was a stout carl for the nones; Ful byg he was of brawn and eek of bones. That proved wel, for over-al, ther he cam, At wrastlynge he wolde have alwey the ram. He was short-sholdred, brood, a thikke knarre; Ther nas no dore that he nolde heve of harre, Or breke it at a rennyng with his heed. His berd as any sowe or fox was reed, And therto brood, as though it were a spade. Upon the cop right of his nose he hade A werte, and thereon stood a toft of herys, Reed as the brustles of a sowes erys; His nosethirles blake were and wyde. A swerd and a bokeler bar he by his syde. His mouth as greet was as a greet forneys; He was a janglere and a goliardeys, And that was moost of synne and harlotries. Wel koude he stelen corn and tollen thries; And yet he hadde a thombe of gold, pardee. A whit cote and a blew hood wered he. A baggepipe wel koude he blowe and sowne, And therwithal he broghte us out of towne.

A gentil Maunciple was ther of a temple, Of which achátours myghte take exemple For to be wise in byynge of vitaille; For, wheither that he payde or took by taille, Algate he wayted so in his achaat That he was ay biforn and in good staat. Now is nat that of God a ful fair grace, That swich a lewed mannes wit shal pace The wisdom of an heep of lerned men? Of maistres hadde he mo than thries ten, That weren of lawe expert and curious, Of whiche ther weren a duszeyne in that hous Worthy to been stywardes of rente and lond Of any lord that is in Engelond, To maken hym lyve by his propre good, In honour dettelees, but if he were wood, Or lyve as scarsly as hym list desire; And able for to helpen al a shire In any caas that myghte falle or happe; And yet this Manciple sette hir aller cappe

The Reve was a sclendre colerik man. His berd was shave as ny as ever he kan; His heer was by his erys round y-shorn; His top was dokked lyk a preest biforn. Ful longe were his legges and ful lene, Y-lyk a staf, ther was no calf y-sene. Wel koude he kepe a gerner and a bynne; Ther was noon auditour koude on him wynne. Wel wiste he, by the droghte and by the reyn, The yeldynge of his seed and of his greyn. His lordes sheep, his neet, his dayerye, His swyn, his hors, his stoor, and his pultrye, Was hoolly in this reves governyng; And by his covenant yaf the rekenyng Syn that his lord was twenty yeer of age; There koude no man brynge hym in arrerage. There nas baillif, ne hierde, nor oother hyne, That he ne knew his sleighte and his covyne; They were adrad of hym as of the deeth. His wonyng was ful fair upon an heeth; With grene trees shadwed was his place. He koude bettre than his lord purchace; Ful riche he was a-stored pryvely. His lord wel koude he plesen subtilly, To yeve and lene hym of his owene good, And have a thank, and yet a cote and hood. In youthe he hadde lerned a good myster; He was a wel good wrighte, a carpenter. This Reve sat upon a ful good stot, That was al pomely grey, and highte Scot. A long surcote of pers upon he hade, And by his syde he baar a rusty blade. Of Northfolk was this Reve of which I telle, Biside a toun men clepen Baldeswelle. Tukked he was as is a frere, aboute. And evere he rood the hyndreste of oure route.

A Somonour was ther with us in that place, That hadde a fyr-reed cherubynnes face, For sawcefleem he was, with eyen narwe. As hoot he was and lecherous as a sparwe, With scaled browes blake and piled berd,— Of his visage children were aferd. Ther nas quyk-silver, lytarge, ne brymstoon, Boras, ceruce, ne oille of tartre noon, Ne oynement that wolde clense and byte, That hym myghte helpen of his whelkes white, Nor of the knobbes sittynge on his chekes. Wel loved he garleek, oynons, and eek lekes, And for to drynken strong wyn, reed as blood. Thanne wolde he speke, and crie as he were wood. And whan that he wel dronken hadde the wyn, Than wolde he speke no word but Latyn. A fewe termes hadde he, two or thre, That he had lerned out of som decree,— No wonder is, he herde it al the day; And eek ye knowen wel how that a jay Kan clepen "Watte" as wel as kan the pope. But whoso koude in oother thyng hym grope, Thanne hadde he spent al his philosophie; Ay "Questio quid juris" wolde he crie. He was a gentil harlot and a kynde; A bettre felawe sholde men noght fynde. He wolde suffre for a quart of wyn A good felawe to have his concubyn A twelf month, and excuse hym atte fulle; And prively a fynch eek koude he pulle. And if he foond owher a good felawe, He wolde techen him to have noon awe, In swich caas, of the erchedekenes curs, But if a mannes soule were in his purs; For in his purs he sholde y-punysshed be: "Purs is the erchedekenes helle," seyde he. But wel I woot he lyed right in dede. Of cursyng oghte ech gilty man him drede, For curs wol slee, right as assoillyng savith; And also war him of a Significavit. In daunger hadde he at his owene gise The yonge girles of the diocise, And knew hir conseil, and was al hir reed. A gerland hadde he set upon his heed, As greet as it were for an ale-stake; A bokeleer hadde he maad him of a cake.

With hym ther rood a gentil Pardoner Of Rouncivale, his freend and his compeer, That streight was comen fro the court of Rome. Ful loude he soong, "Com hider, love, to me!" This Somonour bar to hym a stif burdoun; Was nevere trompe of half so greet a soun. This Pardoner hadde heer as yelow as wex, But smothe it heeng as dooth a strike of flex; By ounces henge his lokkes that he hadde, And therwith he his shuldres overspradde. But thynne it lay, by colpons, oon and oon; But hood, for jolitee, wered he noon, For it was trussed up in his walét. Hym thoughte he rood al of the newe jet; Dischevelee, save his cappe, he rood al bare. Swiche glarynge eyen hadde he as an hare. A vernycle hadde he sowed upon his cappe. His walet lay biforn hym in his lappe, Bret-ful of pardoun, comen from Rome al hoot. A voys he hadde as smal as hath a goot. No berd hadde he, ne nevere sholde have, As smothe it was as it were late y-shave; I trowe he were a geldyng or a mare. But of his craft, fro Berwyk into Ware, Ne was ther swich another pardoner; For in his male he hadde a pilwe-beer, Which that, he seyde, was Oure Lady veyl; He seyde he hadde a gobet of the seyl That Seinte Peter hadde, whan that he wente Upon the see, til Jesu Crist hym hente. He hadde a croys of latoun, ful of stones, And in a glas he hadde pigges bones. But with thise relikes, whan that he fond A povre person dwellynge upon lond, Upon a day he gat hym moore moneye Than that the person gat in monthes tweye; And thus with feyned flaterye and japes He made the person and the peple his apes. But trewely to tellen atte laste, He was in chirche a noble ecclesiaste; Wel koude he rede a lessoun or a storie, But alderbest he song an offertorie; For wel he wiste, whan that song was songe, He moste preche, and wel affile his tonge To wynne silver, as he ful wel koude; Therefore he song the murierly and loude.

Now have I toold you shortly, in a clause, Thestaat, tharray, the nombre, and eek the cause Why that assembled was this compaignye In Southwerk, at this gentil hostelrye That highte the Tabard, faste by the Belle. But now is tyme to yow for to telle How that we baren us that ilke nyght, Whan we were in that hostelrie alyght; And after wol I telle of our viage And al the remenaunt of oure pilgrimage.

But first, I pray yow, of youre curteisye, That ye narette it nat my vileynye, Thogh that I pleynly speke in this mateere, To telle yow hir wordes and hir cheere, Ne thogh I speke hir wordes proprely. For this ye knowen al-so wel as I, Whoso shal telle a tale after a man, He moot reherce, as ny as evere he kan, Everich a word, if it be in his charge, Al speke he never so rudeliche and large; Or ellis he moot telle his tale untrewe, Or feyne thyng, or fynde wordes newe. He may nat spare, althogh he were his brother; He moot as wel seye o word as another. Crist spak hymself ful brode in hooly writ, And wel ye woot no vileynye is it. Eek Plato seith, whoso kan hym rede, "The wordes moote be cosyn to the dede."

Also I prey yow to foryeve it me, Al have I nat set folk in hir degree Heere in this tale, as that they sholde stonde; My wit is short, ye may wel understonde.

Greet chiere made oure Hoost us everichon, And to the soper sette he us anon, And served us with vitaille at the beste: Strong was the wyn and wel to drynke us leste.

A semely man Oure Hooste was with-alle For to been a marchal in an halle. A large man he was with eyen stepe, A fairer burgeys was ther noon in Chepe; Boold of his speche, and wys, and well y-taught, And of manhod hym lakkede right naught. Eek thereto he was right a myrie man, And after soper pleyen he bigan, And spak of myrthe amonges othere thynges, Whan that we hadde maad our rekenynges; And seyde thus: "Now, lordynges, trewely, Ye been to me right welcome, hertely; For by my trouthe, if that I shal nat lye, I saugh nat this yeer so myrie a compaignye At ones in this herberwe as is now. Fayn wolde I doon yow myrthe, wiste I how; And of a myrthe I am right now bythoght, To doon yow ese, and it shal coste noght.

"Ye goon to Canterbury—God yow speede, The blisful martir quite yow youre meede! And wel I woot, as ye goon by the weye, Ye shapen yow to talen and to pleye; For trewely confort ne myrthe is noon To ride by the weye doumb as a stoon; And therfore wol I maken yow disport, As I seyde erst, and doon yow som confort. And if you liketh alle, by oon assent, For to stonden at my juggement, And for to werken as I shal yow seye, To-morwe, whan ye riden by the weye, Now, by my fader soule, that is deed, But ye be myrie, I wol yeve yow myn heed! Hoold up youre hond, withouten moore speche."

Oure conseil was nat longe for to seche; Us thoughte it was noght worth to make it wys, And graunted hym withouten moore avys, And bad him seye his verdit, as hym leste.

"Lordynges," quod he, "now herkneth for the beste; But taak it nought, I prey yow, in desdeyn; This is the poynt, to speken short and pleyn, That ech of yow, to shorte with oure weye In this viage, shal telle tales tweye, To Caunterbury-ward, I mene it so, And homward he shal tellen othere two, Of aventúres that whilom han bifalle. And which of yow that bereth hym beste of alle, That is to seyn, that telleth in this caas Tales of best sentence and moost solaas, Shal have a soper at oure aller cost, Heere in this place, sittynge by this post, Whan that we come agayn fro Caunterbury. And, for to make yow the moore mury, I wol myselven gladly with yow ryde, Right at myn owene cost, and be youre gyde; And whoso wole my juggement withseye Shal paye al that we spenden by the weye. And if ye vouche-sauf that it be so, Tel me anon, withouten wordes mo, And I wol erly shape me therfore."

This thyng was graunted, and oure othes swore With ful glad herte, and preyden hym also That he wolde vouche-sauf for to do so, And that he wolde been oure governour, And of our tales juge and réportour, And sette a soper at a certeyn pris; And we wol reuled been at his devys In heigh and lough; and thus, by oon assent, We been acorded to his juggement. And therupon the wyn was fet anon; We dronken, and to reste wente echon, Withouten any lenger taryynge.

Amorwe, whan that day gan for to sprynge, Up roos oure Hoost and was oure aller cok, And gadrede us togidre alle in a flok; And forth we riden, a litel moore than paas, Unto the wateryng of Seint Thomas; And there oure Hoost bigan his hors areste, And seyde, "Lordynges, herkneth, if yow leste: Ye woot youre foreward and I it yow recorde. If even-song and morwe-song accorde, Lat se now who shal telle the firste tale. As ever mote I drynke wyn or ale, Whoso be rebel to my juggement Shal paye for all that by the wey is spent. Now draweth cut, er that we ferrer twynne; He which that hath the shorteste shal bigynne. Sire Knyght," quod he, "my mayster and my lord Now draweth cut, for that is myn accord. Cometh neer," quod he, "my lady Prioresse. And ye, sire Clerk, lat be your shamefastnesse, Ne studieth noght. Ley hond to, every man."

Anon to drawen every wight bigan, And, shortly for to tellen as it was, Were it by áventúre, or sort, or cas, The sothe is this, the cut fil to the Knyght, Of which ful blithe and glad was every wyght; And telle he moste his tale, as was resoun, By foreward and by composicioun, As ye han herd; what nedeth wordes mo? And whan this goode man saugh that it was so, As he that wys was and obedient To kepe his foreward by his free assent, He seyde, "Syn I shal bigynne the game, What, welcome be the cut, a Goddes name! Now lat us ryde, and herkneth what I seye." And with that word we ryden forth oure weye; And he bigan with right a myrie cheere His tale anon, and seyde in this manére.

0 notes

Text

J6 Political Prisoner and Devout Christian Geoffrey Sills Sits in Prison without Trial for Nearly 2 Years - FBI Raided His Home at 6 AM and Brought Robot to Search Under House - PLEASE HELP IF YOU ARE ABLE

0 notes

Text

https://www.thegatewaypundit.com/2023/02/j6-political-prisoner-devout-christian-geoffrey-sills-sits-prison-without-trial-nearly-2-years-fbi-raided-home-6-brought-robot-search-house-please-help/

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

J6 Political Prisoner and Devout Christian Geoffrey Sills Sits in Prison without Trial for Nearly 2 Years – FBI Raided His Home at 6 AM and Brought Robot to Search Under House – PLEASE HELP IF YOU ARE ABLE https://www.thegatewaypundit.com/2023/02/j6-political-prisoner-devout-christian-geoffrey-sills-sits-prison-without-trial-nearly-2-years-fbi-raided-home-6-brought-robot-search-house-please-help/

0 notes

Text

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, contrary to popular belief, were not a declaration of a split from Rome (I promise this is getting back to Sandman and, eventually, a fic idea but you’re just gonna have to bear with me for a second). At the time, a Thesis was simply a statement to be debated and that was Luther’s original intention. Luther had studied theology and taught at the University of Wittenberg. He was a devout Catholic and had begun to question a lot of the Catholic teachings. He took issue with a lot of Rome’s policies and beliefs (indulgences weren’t the main issue, in fact they were fairly low on the list of Luther’s concerns) and the use of Theses to be able to discuss concerns within the Catholic church was fairly commonplace. Erasmus and More, lifelong Catholics, also criticized the church heavily in order to better understand faith, the bible, and theology as a whole. The only reason that Luther’s Theses garnered so much attention is that someone (no one knows who) took his copy of the Theses off of the church door where he nailed them and printed copies on the printing press, distributing them widely. This would snowball into Luther’s bold and public break from Rome, changing the course of religion in Europe forever.

Now here’s my fic idea: Hob was the person to print Luther’s 95 Theses. Now, you might be saying ‘but Crow! Luther was in the Holy Roman Empire and Hob was in England!’ And you’d be right; every time we see Hob, he’s in London. But that doesn’t mean that he can’t travel. He’s not chained to England, and he had 100 years to do whatever the fuck he wanted in between each meeting. It’s not completely impossible that Hob found himself in Wittenberg, Germany in the year 1517 and had easy access to a printing press. ‘But Crow!’ you say again, ‘Why would Hob do that?’ To which I say: Hob is an instigator at heart. By 1517, he’s come to terms with the fact that he can’t die. He’s fully embraced his immortal status. He’s also started to learn what a little something I like to call a pivotal moment looks like and as soon as he sees those Theses on that church door, it’s almost like a video game side quest marker appears. “Oh,” he thinks to himself, “oh, this could be fun.” Because I think Hob is devoutly Catholic, but so was Luther, and maybe Hob genuinely agreed with Luther’s questions, maybe he genuinely wanted to spread the ideas, not out of any malicious intent but out of curiosity and a desire to spread what he thought were valid points of debate

I just really want Hob to be majorly involved in historical events simply because he was there, because he happened to be in the right place at the right time (I mean, let’s be honest, he has, at different points in his life, been in the same room as Geoffrey Chaucer AND William Shakespeare, the man attracts major historical figures to him like moths to a flame). I want Hob to be able to look back at history and pinpoint the major turning points that he had a hand in. I want Hob to be in the middle of a lecture about Luther and when someone asks who spread Luther’s ideas, I want Hob to smile enigmatically and say “you know? no one really knows,” and know deep down in his heart of hearts that, for better or worse, his fingerprints were on those pages, that his fingerprints and impacts span 600 years of history

#this got out of hand#I just wanted Hob to see Luther’s Theses and go ‘hehehe’ like a little gremlin#because he’s a fighter and an instigator first and foremost#hob gadling#hob gadling thoughts and rambles#the sandman#sandman netflix

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...In one way, the marriage of Eleanor and Louis was unusual, for he was also a teenager (born c.1120–23) and little older than his bride. In numerous aristocratic marriages, the bride was much younger than her spouse; it was not uncommon for teenaged noble maidens to be married to men in their thirties or older. The couple’s similar ages likely gave Eleanor higher expectations that their marriage had more likelihood of turning into a true love match than other aristocratic marriages with great age disparities. No doubt, their similar ages also led Eleanor to assume that their marriage would be a true partnership; and she would feel more free to express her opinions to her young husband and to persuade him to accept her ideas than if he had been a mature, experienced man.

In several ways, however, the bride and groom were mismatched. Louis the Younger, apparently a good-looking youth with shoulder-length hair, was quiet, serious, and exceedingly devout. The second son of Louis VI and Adelaide of Maurienne, his upbringing had aimed at preparing him for an ecclesiastical career with studies at the school attached to Notre-Dame Cathedral on the Île de la Cité in Paris not far from the royal palace. Louis’s elder brother Philip, heir to the throne, was killed when he was thrown to the ground and crushed by his falling horse after it “stumbled over a diabolical pig” in the road. This unexpectedly elevated Louis to the position of heir to the French throne.

The boy left Notre-Dame’s cloisters at about age ten to be crowned king in accordance with the custom established by the second Capetian king of installing the current monarch’s heir in his own lifetime to ensure a smooth succession. Twelve days after his brother’s death, Louis’s consecration as king took place at Reims Cathedral in October 1131 in the presence of a great council of prelates presided over by the pope. Louis VII apparently returned to his religious studies after his coronation, and his clerical education would make a powerful impression on him throughout his life, imprinting on him simple tastes in dress and manners and an earnest piety.

His Capetian predecessors had sought to present themselves as models of Christian kingship, stressing their close relations with the Church as compensation for their modest military power. Louis’s reputation for piety and spirituality surpassed that of earlier French monarchs, however. As one contemporary wrote, “He was so pious, so just, so catholic and benign, that if you were to see his simplicity of behaviour and dress, you would think . . . that he was not a king, but a man of religion.”

Young Louis thought of kingship as a religious vocation, and he felt called to govern according to Christian principles. In his first years as king, his confidence that he was God’s agent as French monarch gave him an unrealistic notion of his power, and he tended to over-reach, pursuing excessively ambitious political goals. In his youthful enthusiasm, he often displayed an inclination toward rash decisions taken in anger and without reflection. Yet he sometimes seemed sluggish and unenthusiastic for his task of governing, partly due to a distaste for political intrigue, and partly due to a lack of perseverance, his ardor rapidly cooling and giving way to periods of indecision and inactivity.

Although he held a very high view of the monarchical office, he could be timid, and he allowed himself to fall under the influence of members of his entourage. Most prominent among those seeking to influence this impressionable youth was his young wife Eleanor, and he readily allowed her to take part in political decision-making. Such a mild husband as Louis VII was unlikely to find happiness with a wife such as Eleanor of Aquitaine. His young bride had already seen more of life than his sheltered upbringing had allowed him. A girl brought up at a sophisticated and lively court where no more than conventional piety was observed and whose own grandfather had lived openly for years with his paramour would find the Capetian royal court’s piety and repression confining.

If Eleanor had been too young to remember life at William the Troubadour’s court, she grew up surrounded by people who had tasted its pleasures willing to tell her about it. Looking back on her earliest childhood while in Paris “through the prism of her imagination,” she could only compare the austere Capetian royal court unfavorably with an idealized image of her grandfather’s court. A widely quoted quip ascribed to Eleanor that she felt that she “had married a monk, not a king,” while hardly an authentic quotation, captures the feeling that she surely came to hold for Louis.

Although his clerical education had not prepared him for a fulfilling marital relationship, Eleanor’s beauty and charm captivated him at once and soon he fell deeply in love with her. Indeed, some observers of the couple’s marriage described the king’s love for his wife as “almost childish” and passionate beyond reason. The intensity of Louis’s love for his bride may have made him an anxious husband, easily roused to jealousy. Despite evidence of Louis’s attraction to his bride, the Church’s notoriously misogynist view of women and teachings of the early Fathers had ill-equipped him for the robust sexual relationship that Eleanor expected. Louis, brought up in a clerical environment, was prudish and repressed in a way that the queen could not understand.

…The royal bridegroom and his entourage reached Limoges on 1 July 1137, and after stopping there for prayers at the shrine of Saint Martial, Louis and his party arrived at Bordeaux on 11 July. They raised tents and camped on the banks of the Garonne river across from the city, where they waited for boats to cross the wide waters. The entry into Bordeaux of Louis the Younger, crowned king six years earlier, marked the first French monarch’s visit there in three centuries. The wedding took place on 25 July in the cathedral of Saint André, constructed around the end of the eleventh century. Today only its surprisingly plain façade survives from Eleanor’s time.

In full summer heat, a great throng of nobles of all ranks came from throughout Eleanor’s lands to witness the couple’s exchange of vows. As part of the ceremony, Louis had his bride “crowned with the diadem of the kingdom.” To commemorate the occasion, young Louis had brought along lavish gifts for his bride that a chronicler asserted would have required the mouth of a Cicero or the memory of a Seneca to expose their richness and variety. Usually aristocratic marriages were preceded by lengthy negotiations between the couple’s parents about financial arrangements.

…In the case of young Eleanor, she was bringing to her husband a great duchy, and no other wedding gift was expected. No doubt she retained revenues from her ancestral estates in Poitou, and it seemed pointless to designate lands from the limited French royal domain as her dowerland. As the young couple set out on their journey to Paris, she offered her new husband another splendid present, however—a vase carved from rock crystal, one of her few possessions that survives today. The vase was a cherished possession, connecting her to her grandfather William IX, who had brought it back to Poitiers after an expedition to Spain.

Louis VI marked the marriage of his son and heir to Eleanor with grants of important privileges to the ecclesiastical province of Bordeaux, acting quickly to secure the support of the bishops in Aquitaine. Before Louis the Younger set out for Aquitaine, the king renounced any claim to rights of lordship over the dioceses of the province of Bordeaux, allowing them free episcopal elections. This concession ended the traditional ducal privilege of playing a part in the selection of bishops in the six dioceses of the province of Bordeaux.

…As soon as the wedding celebrations ended in the evening of 25 July, the newly-weds lost no time in beginning their journey toward Paris. Eleanor and Louis stopped to spend their first night together at Taillebourg, a formidable castle looming over the Charente river, where their host was its lord, Geoffrey de Rancon. The most powerful of lords in the Saintonge, Geoffrey held wide lands stretching from his castle of Taillebourg eastward to La Marche, to Poitou proper in the north, and southward into the Angoumois. He and his heirs would be important players in Poitevin politics throughout Eleanor’s lifetime. Whether the young couple consummated their marriage that first night at Taillebourg cannot be known, but royal retainers surely looked for evidence, since both the Church and popular opinion held no marriage to be an indissoluble union until it was consummated.

By the beginning of August, the couple arrived at Poitiers, where a week later Suger organized a formal investiture of young Louis in the cathedral of Saint Pierre, a religious ceremony signaling the Church’s sanction for his ducal title. Young Louis, already crowned and anointed king of the French, did not adopt the titles “count of Poitou” or “duke of Gascony” on his marriage; instead, he had only the additional title “duke of Aquitaine” engraved on his seal. The title that he adopted implied that his bride’s duchy, though under Capetian administration, was not to be absorbed into the French Crown lands, but would preserve a separate identity with distinct institutions.

Barely after the ceremony had ended, a messenger arrived from Paris with the sad news that King Louis VI had died on 1 August, aged almost sixty. The intense summer heat demanded his immediate burial at the abbey of Saint Denis without waiting for the arrival of Louis the Younger and his bride from Poitou. Young Louis, already a crowned and anointed king on his father’s death, had to take on royal responsibilities at once, and the newly married Eleanor became a queen. Now King Louis VII, he had to leave his bride in the care of Bishop Geoffrey of Chartres to continue her progress toward Paris, while he led a force to subdue the rebel townspeople of Orléans, who had taken advantage of the old king’s death to proclaim their city a commune, taking rights of self-government for themselves.”

- Ralph V. Turner, “Bride to a King, Queen of the French, 1137–1145.” in Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England

#eleanor of aquitaine#eleanor of aquitaine: queen of france queen of england#ralph v. turner#history#high middle ages#medieval#french#louis vii of france

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun fact – Philip’s sobriquet “the Prudent” (el Prudente) first appeared in the work Historia general del Mundo del tiempo del Señor Rey don Felipe II, el Prudente written by Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas, first published in 1601. Herrera was commissioned to write an official history of Philip’s reign. After Philip’s death he made a suggestion to the new king Philip III to give some sobriquet to Philip II in this work because according to Herrera many rulers of the world had used them. Among the variants he offered were “el Religioso (the Religious), el Compuesto (the Composed), el Bueno (the Good), el Prudente (the Prudent), el Honesto (the Honest), el Justo (the Just), el Devoto (the Devout), el Modesto (the Modest), el Constante (the Constant).” Someone who read this suggestion, made a sign next to “the Prudent”, the choice was made and approved, and since then Philip is known as “el Rey Prudente” – “the Prudent king”.

Source: Felipe II: La biografía definitiva by Geoffrey Parker

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Grand Ducal Family Attends Winterfest Service!

Among the many devout who spent part of this snowy Winterfest morning at Notre-Dame de Esten Cathedral was the extended Grand Ducal family of Estenbourg. The service, administered by Cardinal Geoffrey Bequet, Archbishop of Estenbourg, was also broadcast publicly via both radio and television.

His Royal Highness, Grand Duke Mathew and Her Royal Highness, Grand Duchess Alixandrine are seen here leading the family’s exit from the Cathedral, followed closely by HRH Prince Wilhelm, Hereditary Grand Duke, who can be seen carrying his young first cousin once removed, Countess Maria Louisa of Vergiess-Huel, whose grandmother, HRH Princess Mathilde, Dowager Countess of Vergiesss-Huel, walks a few paces away. Rounding out the group are HRH Princess Amelia and HRH Prince Jerome, the Grand Ducal couple’s younger two children.

The family, escorted by only mild security, walked the mile from the cathedral to Wenceslaus Palace, with the Grand Duke stopping at a few points to pass out chocolate oranges and other small gifts to children watching the procession.

After finishing Winterfest celebrations with his family, HRH Prince Wilhelm will be travelling to Krasnoyarsk for a brief state, and longer personal, visit with their Imperial Family. While distant relations of the Shakhovsky family, The Hereditary Grand Duke counts them amongst his closest friends.

(Happy belated winterfest, more than a month later! Thank you to @krasnoyarsk-nobility for hosting the upcoming visit - I’m looking forward to what we have in store!)

#sims royalty#sims legacy#simblr#grandducalsims#ts4#ts4 story#sims gameplay#sims 4 royal#simsroyalty#ts4 gameplay

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

For @apsaraqueen

This was written as cheerupemofic for BAMF a few weeks-ish ago, I think? Never got around to posting it but here it goes. Somewhat experimental R/J. Some angst but... it’s, uh, for BAMF? So. Yeah.

***

“Love is so short, forgetting is so long.” - Pablo Neruda

I.

The Moon is beautiful and stately, all marble palaces and graceful domes, but leached of colour in an eerie wash of silvery white. Jikokuten takes a knee in the throne room and looks askance at the royals, for even they blend into this ghostly dream-world with their pearlescent gowns and platinum locks. The weather and grounds are flawless, not a single leaf or stone out of place. It’s almost too perfect-- ominously so-- and to one whose kingdom only dons white for mourning, it’s jarring.

And then he sees the High Queen’s court file in, the warrior princesses of legend, flanking the throne two by two, and there she is, a spot of scarlet in the sea of white. Ebony hair and auspicious red skirts, eyes like the twilight sky before it turns full dark. He blinks, and his heart stutters.

II.

The sheep are languishing in the heat, and getting leaner by the day with nothing but dry brush to eat, and Jochi coaxes some of his own water onto the littlest and weakest of the lambs. It’s foolish, and more than likely the little animal would die anyway, too malnourished to survive the drought which had blighted the steppes this summer. His father had always railed at him for being too soft-hearted, too foolish and un-Mongolian, but a part of Jochi always had perhaps too much sympathy for the foundlings and the weaker ones. There is a nebulous memory, perhaps not his own, of standing up for a boy with eyes like the open sky and a shock of black hair from-- what? He doesn’t quite know.