#Erich Müller

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ansichtskarte

Neu Fahrland Heinrich-Heine-Sanatorium, Waldhaus

Reichenbach (Vogtl): VEB BILD UND HEIMAT Reichenbach i.V. (III/26/117 - A 246/59 - DDR Best.-Nr. 4/843 188/59)

Foto: [Erich] Müller, Böhlitz-Ehrenberg

1959

#Neu Fahrland#Bezirk Potsdam#Philokartie#DDRPhilokartie#GesundheitswesenDerDDR#Ansichtskartenfotografie#akNeuFahrland#BezirkPotsdam#AnsichtskartenfotografieDerDDR#deltiology#VintagePostcard#1950er#1959#Erich Müller#BILD UND HEIMAT#Sanatorium#Gesundheitswesen

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just as we turn into animals when we go up to the line, because that is the only thing which brings us through safely, so we turn into wags and loafers when we are resting.

We can do nothing else, it is a sheer necessity.

[...] But our comrades are dead, we cannot help them, they have their rest--and who knows what is waiting for us? We will make ourselves comfortable and sleep, and eat as much as we can stuff into our bellies, and drink and smoke so that hours are not wasted. Life is short.

(ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT by Erich Maria Remarque)

#all quiet on the western front#erich maria remarque#resting#green fields of france#paul bäumer#franz müller#tjaden stackfleet#stanilaus katczinsky#albert kropp#im Westen nichts Neues#AQOTWF#illustration#my art#fanart#those scenes in the book when the small group were resting together behind the frontlines and talked about the senselessness of this war

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albrecht Schuch and Edin Hasanović being cuties during the premier of All Quiet on the Western Front

Bonus:

Felix cute waving ~

The Boys (TM) looking dandy in their outfits!

#albrecht schuch#edin hasanovic#felix kammerer#jakob schmidt#aaron hilmer#moritz klaus#all quiet on the western front#im westen nichts neues#paul bäumer#stanislaus katczinsky#albert kropp#frantz Müller#adrian grünewald#ludwig behm#tjaden stackfleet#germany#erich maria remarque#gif#oscars#2023#german actor#period movie#period drama#world war 1#premier#berlin#netflix

106 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Karl Erich Müller - Self portrait

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sin novedad en el frente

Capítulo 1

Nos encontramos en la retaguardia, a nueve kilómetros del frente.

-Erich Maria Remarque

#Novela histórica#primera guerra mundial#Literatura alemana#Horrores de la guerra#Pérdida de la inocencia#Sin novedad en el frente#Novela antibélica#Erich Maria Remarque#Literatura clásica#Paul Bäumer#Tjaden Müller Albert Kropp Katczinsky#Guerra de trincheras

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

*

youtube

pogo 1104, wigbert wicker 1984

#pogo 1104#tv series#wigbert wicker#1984#anja schüte#ralf richter#erich bar#richy müller#richie#pirate radio#radio störtebecker#hamburg#material#flyweight#buw#about photography#das arche noah prinzip#katz und maus#sansibar oder der letzte grund#über filmfinanzierung

0 notes

Text

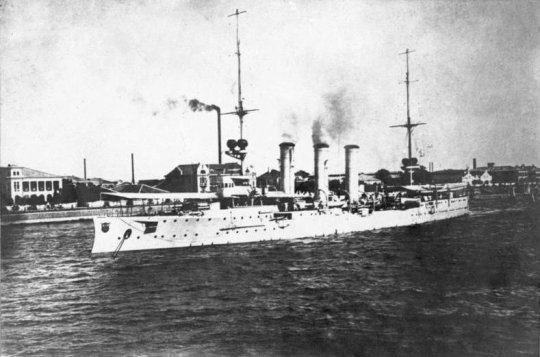

SMS „Emden“ versenkt die „Diplomat“

Gefürchtet und geachtet Die kurze Geschichte einer weltberühmten Kaperfahrt Ich habe lange überlegt, ob ich zu SMS „Emden“ einen Artikel machen soll, da es wirklich genug Literatur und Verfilmungen über das wahrscheinlich bekannteste Schiff des Ersten Weltkrieges gibt. Nachdem aber Kapitän R. J. Thomson, der die „Fürth“ mit seiner Mannschaft von Colombo nach London überführte, mit seinem Schiff…

View On WordPress

#Cocos Inseln#Colombo#Dampfschiff Fürth#Diplomat#Direction Island#Diyatalawa#Erich Hupka#Freudenberg#HMAS Sydney#Kabinga#Kalkutta#Karl von Müller#SMS Emden#T & J Harrison#Tsingtau

0 notes

Text

Already for centuries the book is a primary means for architects to present their work and ideas about architecture. Accordingly there literally are thousands and thousands of architecture books spanning centuries and styles. In 2016 architect and researcher André Tavares published his fabled book „The Anatomy of the Architectural Book“ with Lars Müller Publishers who have recently published the second edition of the long out of print book.

In line with the book’s title it isn’t a history of the architecture book but an exploration of its anatomy as a reflection of architecture. Beginning with two case studies, namely the 1851 Chrystal Palace exhibition in London and Sigfried Giedion’s „Befreites Wohnen“ from 1929, Tavares showcases how in the first example chromolithography allowed color illustrations and involved the publication in the contemporary discourse about the appropriate use of color in architecture. The second example in turn represents an object in its own right with which Giedion supported his arguments for modern housing.

In part two of the book Tavares dives deeper into the anatomy of the architectural book by analyzing a wealth of books. On basis of the five characteristics texture, surface, rhythm, structure and scale he examines books by the likes of Giovanni Battista da Sangallo, Gottfried Semper, Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Gropius and Erich Mendelsohn. The latter’s book „Amerika“ from 1926 is one of the examples in the rhythm section: as Tavares explains, Mendelsohn translated his experience of the perceptual dynamism in the USA to the book by organizing the its pages cinematically. This means that he immerses the reader in the American city and its architecture by gradually moving from piercing contrasts to sequences of street views to make the reader aware of its physical qualities.

Although the previous example represents just one of the three methods of organization showcased by the author it demonstrates his in-depth analyses of the architecture book’s development over time. This amalgam of book, architectural and media history makes Tavares’ publication a fantastic read that is highly recommended!

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a little of a week ago was the anniversary of the Wannsee Confrence. Fifteen men decided the fate of millions. Barely more than a scratch of a pen against paper and people were doomed.

While there are a few well-known names on here, most of them you won't recognize.

Reinhard Heydrich

Otto Hofmann

Heinrich Müller

Karl Eberhard Schongarth

Gerhard Klopfer

Adolf Eichmann

Rudolf Lange

Georg Leibbrandt

Alfred Meyer

Josef Bühler

Roland Freisler

Wilhelm Stuckart

Erich Neumann

Friedrich Wilhelm Kritzinger

Martin Luther

15 men sealed the fate of those they never met and would never meet.

It didn't take 90 minutes.

#know their names#reichblr#ww2 history#wwii#wwii era#ww2#ww2 germany#wwii germany#3rd reich#heydrich#reinhard heydrich

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 Days of La Fayette - The Shadow of Olmütz

Day 1: All the world’s a stage …

As soon as you enter the busy tavern you are met with lively chatter. You exhale, trying to reign your ever rising tension in. If this goes wrong, even attending this meeting can bring you in a potentially deadly predicament. The Austrian government is not known to be kind to those they suspect of sympathizing with French Revolutionaries. You square your shoulders; you have thought about the risks and are willing to take them – your shaking hands be dammed. Your view wanders through the packed room. This is certainly not the finest inn the town has to offer but also not the shabbiest. You spot a group of men sitting together in the far-right corner, seven of them altogether. No, you were told to meet with only two others. On the other side there sits a couple with three young children – a fourth on its way by the looks of the women. You try to further scan your surroundings, as inconspicuous as possible, when someone calls your name. Startled, you turn around. On the table behind you sits Martin Müller, you know him from Church, with his mates. He raises a hand in greeting, and you reciprocate the gesture. Don’t lose your nerves! Suddenly you spot them, two men, both still in their twenties, sitting alone on a table, partially obscured by the bar. You walk over to them, deliberately slow, and take a seat. Both men look up at you and the older one gives you a skeptical look. “We were waiting for a friend to join us”, he informs you. “So was I”, you explain before adding “the fire burns so merrily these days.” An expression of recognition passes over the younger man’s feature after hearing the agreed upon code, and he zealously declares “They say the firewood is imported from Prussia!” You simply nod and allow your glance to wander from one man to the other – you just found your co-conspirators in this endeavor! “I am Francis, Francis Kinloch Huger”, the younger man introduces himself and shakes your hand. You already admire and dread his passion in equal terms. Huger’s father had lodged the Marquis de La Fayette when he first came to America. The son is now a student of medicine in Vienna. “And my name is Justus Erich Bollmann. Pleased to make you acquaintance”, the older, sterner, man introduces himself but does not offer you his hand. You nod again. You know Doctor Bollmann by reputation since he has already served as a messenger for the Marquis’ clandestine notes. You know that he is trustworthy – but now is the time to introduce yourself and show Huger and Bollmann that you are just as trustworthy and dependable as they are!

I am Friedrich Willerich, a physician, just like Bollmann and Huger!

I am Georg Oltmanns, a lawyer in training with some connections to the local officials! (If you choose this option, I might surprise you with a part in Plattdüütsch ;-))

I am Hugo Curie, a French Chaplain, but left my home country many years ago!

#24 days of la fayette#polls#marquis de lafayette#french history#la fayette#american history#history#lafayette#french revolution#alternative history#francis kinloch huger#justus erich bollmann#lafayette in prison#olmütz#the shadow of olmütz#choose your own adventure#choose your own story

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ansichtskarte

FDGB Ferienort Schmannewitz Waldbad

Leipzig: Erich Müller, Böhl.-Ehrgb.(III/18/162T 424 57)

1957

#Schmannewitz#Bezirk Leipzig#Erich Müller#1950er#1957#Philokartie#DDRPhilokartie#FerienkulturDerDDR#WaldbadSchmannewitz#akSchmannewitz#BezirkLeipzig#AlltagskulturDerDDR#Ansichtskartenfotografie#AnsichtskartenfotografieDerDDR#deltiology#VintagePostcard#Freibad

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#all quiet on the western front#behind the scenes#AQOTWF#amazing cast#albrecht schuch - stanislaus katczinsky#moritz klaus - franz müller#felix kammerer - paul bäumer#aaron hilmer - albert kropp#adrian grünewald - ludwig behm#edin hasanovic - tjaden stackfleet#wonderful picture#im westen nichts neues#erich maria remarque

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erich Dieckmann, "Custom armchair,"

Berliner Metallgewerbe Joseph Müller, Germany, 1930,

Painted tube steel, wicker, lacquered wood,

24¾ h × 23½ w × 35 d in (63 × 60 × 89 cm).

The Boyd Collection

#art#design#sculpture#furniture#minimal#seat#bauhaus#armchair#erich dieskmann#1930#steel#paint#wicker#wood#theboydcollection

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flipped through one if my pigeon books to figure out what pigeon i wanted to draw. Settled on the Prachen Kanik

Pic from the book Fancy Pigeons by Erich Müller and Ludwig Schrag

#pigeon#birblr#art#bird#birb#purple pigeon art#pigeons#pigeon art#bird art#artist#prachen kanik#birdblr#artblr#pigeonblr#artists of tumblr#artists on tumblr#fancy pigeon

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herta Müller. L.M. Montgomery. Charles Perrault. Milan Kundera. Jack London. Betty Smith. Erich Maria Remarque. Jean de La Fontaine. Günter Wilhelm Grass. François de La Rochefoucauld. Wisława Szymborska. Elfriede Jelinek.

#literature#quotes#writeblr#writing prompt#star signs#zodiac signs#herta muller#lm montgomery#charles perrault#milan kundera#jack london#berry smith#erich maria remarque#jean de la fontaine#gunter wilhelm grass#francois de la rochefoucauld#wislawa szymborska#elfriede jelinek

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Members of the first German South Polar Expedition (1901 - 1903) on board the "Gauss"

Source: Drygalski 1904 (25-56)

Scientific Staff

Erich von Drygalski (Expedition Leader)

Friedrich Bidlingmaier (Physicist for Geomagnetism and Meteorology)

Hans Gazert (Surgeon)

Emil Philippi (Geologist)

Ernst Vanhöffen (Biologist)

Officers

Hans Ruser (Captain)

Wilhelm Lerche (1. Officer)

Richard Vahsel (older 2. Officer)

Ludwig Ott (younger 2. Officer)

Albert Stehr (Senior Engineer)

Ships Crew

Sailors

Josef Müller I (1. Boatswain)

Hans Dahler (2. Boatswain)

August Reimers (1. Carpenter)

Willy Heinrich (2. Carpenter and Diver)

Georg Noack (Sailor and taxidermist)

Max Fisch (Sailor)

Karl Klück (Sailor)

Albert Possin (Sailor)

Paul Björvig (norwegian Sailor und ice pilot)

Daniel Johannsen (norwegian Sailor)

Wilhelm Lysell (swedish Sailor, gets called „Adolf Lusen“ by Bjørvig)

Lenart Reuterskjöld (swedish Sailor, Assistent for magnetic measurements)

Curt Stjernblad (swedish Sailor)

Engine Staff

Reinhold Marek (1. Engineer assitant)

Paul Heinacker (2. Engineer assistant)

Emil Berglöf (Stoker)

Leonard Müller II Stoker

Gustav Bähr (Stoker and Sailor)

Karl Franz (Stoker and Sailor)

Reinhold Michael (Stoker and Sailor)

Galley and Mess Staff

Wilhelm Schwarz (Chef)

August Besenbrock (Steward)

4 notes

·

View notes