#Chinese astrology system

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Why Is Vedic Astrology better than other types of Astrology?

There are three main types: Vedic, Chinese, and Western (Tropical). Within each one, there are further specialised astrology types.

Know about the different types of Vedic Astrology. Get an online astrology consultation by the world-renowned Astrologer Mr. Alok Khandelwal.

Western Astrology

Between 2,000 and 3,000 years ago, the Greeks and the Babylonians invented Western astrology. They held that the relationship between the Earth and the Sun is extremely important since the Sun is the Solar System’s center of gravity. The Tropical Zodiac—which includes the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn—is what truly determines how close the Sun is to the tropics of the Earth. The 12 Western signs also include Ram, Bull, Twins, Crab, Lion, Virgin, Scales, Scorpion, Centaur, Sea-Goat, Water Bearer, and Fish.

Chinese astrology system

Two of the five elements of the Chinese astrology system are distinct from those in Western astrology, but all five are connected to powerful forces in your life, much like the Western concept. Each element is related to a birth year. For instance, people born under the influence of fire, earth, or metal elements are driven to excitement. In contrast, those born underwater, metal, or wood elements are drawn to emotional attachments and the security that security provides. Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Goat, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, and Pig are among the 12 signs in Chinese astrology.

Read Also:- Akshaya Tritiya 2023: Its Significance, Story, and Puja

Vedic astrology (Jyotish)

Literally translated, Vedic astrology (Jyotish) is “the science of light.” The Vedas, one of India’s oldest spiritual texts that date back to roughly 1,500–2,000 BCE, is the source of Vedic science. Vedic astrologers are well known for their spiritual wisdom as well as their ability to predict the future with precision. This is a closer look at Vedic astrology, which differs greatly from both Western and Chinese systems.

Indian or Hindu astrology is the ancient name for the discipline; Vedic astrology is the current label given to it by Vedic astrologer David Frawley. The planets are regarded as the soul’s karmas in Vedic astrology. Karma is actually the main focus of Vedic astrology because it can have either positive or negative effects based on our previous life.

As was already established, karma can have both positive and bad meanings, but the good news is that the planets can help to balance karmic activity by easing suffering and assisting a person through a trying time so that progress can take place.

As was already established, karma can have both positive and bad meanings, but the good news is that the planets can help to balance karmic activity by easing suffering and assisting a person through a trying time so that progress can take place.

As was already mentioned, Vedic astrology uses the Sidereal zodiac, which is “pertaining to the stars,” as opposed to Western astrology, which uses the Tropical zodiac. The link between the planets and the zodiac star constellations is the foundation of the sidereal system. Every 72 years or so, these fixed stars rotate or gently move toward the Earth.

Unlike some of the other types of astrology, Vedic astrology does not consider the angle between the earth and the sun to be an appropriate way to measure the signs. This is due to the precession of the equinoxes, which essentially requires the signs to move backward one day every 72 years in order to maintain their correct astronomical alignment.

The use of planetary periods of influence is one of the best features of Vedic astrology. This is crucial because these times can be quite useful for generating forecasts. It is simple for a reader to provide specifics on how a person might anticipate living during a planetary period by looking at a planet’s chart (sign, house, conjunctions, aspects, house lordship, and strength). Each period is further broken down into shorter sub-periods that can last up to three years, resulting in a stronger and longer prediction. This might relate to one’s future job, romantic relationships, health, and other things.

If you wish to know more about Jyotish or want to resolve personal problems, you can get a free online consultation with our world-renowned astrologer, Mr. Alok Khandelwal.

#Chinese astrology system#Differences between Western & Vedic#talk to astrologer#types of Astrology#vedic astrologer in usa#Vedic astrology#vedic astrology consultation#Vedic astrology predictions#vedic astrology usa#Western & Vedic Astrology#Western Astrology#astrology#asttrolok

1 note

·

View note

Text

April 14, Xi'an, China, Shaanxi History Museum, Qin and Han Dynasties Branch (Part 1 - Political Structure, Laws, and Military):

This was the final museum I went to while in Xi'an, and despite its name, it is not the Shaanxi History Museum/陕西历史博物馆. It is a new branch that's in a separate location from the main museum, so it's also referred to as the "Qin/Han Branch"/秦汉馆 (ugh I wish I could've gone to the main branch), and the museum building and its gates were supposed to imitate the look of Qin/Han-era palaces. It was raining cats and dogs the night before, so the ground still bear traces of that. I had fun though.

This museum doesn't have a lot of unique artifacts that other museums don't have, but instead focuses on the political structure, thought, life, and technologies from Qin and Han dynasties, so there were a lot of tables, maps, and diagrams in the museum. I will only be giving a brief summary of each thing here so these posts won't get too long (and take too much effort to make). If you understand Chinese though, these may be helpful worldbuilding references.

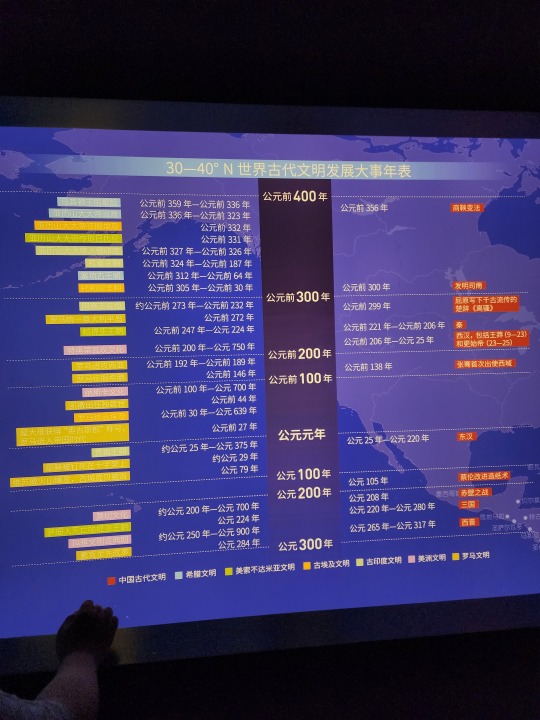

First is a rough timeline of the history Qin dynasty (221 - 207 BC) to Han dynasty (202 BC - 220 AD) (right side of timeline) and how it fits within the overall ancient world history (left side of timeline) in the same time frame, just as a general reference so museum visitors can have an idea of when these dynasties and events took place. The timeline included events starting from when Qin was still a state (Warring States period, 476 - 221 BC) until after the end of Han dynasty (Three Kingdoms period, 220 - 280 AD; and Western Jin dynasty, 265 - 317 AD). Here, 公元元年 means 1 CE/AD, so 公元前 means BCE/BC, and 公元 means CE/AD. Also I know the left side is hard to read, sorry about that, it was easier to read in person. There is a key at the bottom though:

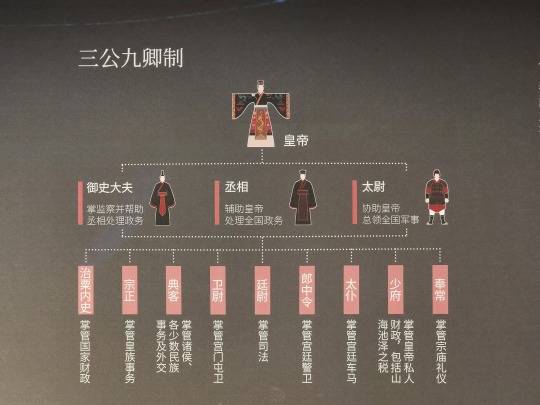

A diagram of the Three Lords and Nine Ministers system (三公九卿制) that was used as the central political structure of ancient China during Qin and Han dynasties, which was replaced by the Three Departments and Six Ministries system (三省六部制) in Sui dynasty (581 - 618 AD). There are many translations for the same positions, here I used what I think fits best for each position.

The Three Lords/三公 are (left to right on chart) : the Imperial Secretary/御史大夫 (handles the audit system and helps the chancellor), the Chancellor/丞相 (helps emperor handle national political affairs), and the Grand Commandant/太尉 (helps emperor handle military affairs).

The Nine Ministers/九卿 are (left to right): the Minister of Finance/治粟内史 (oversees public finance and tax system), the Minister of the Imperial Clan/宗正 (handles affairs within imperial clan), the Grand Herald/典客 (handles foreign policy), the Minister of the Guards/卫尉 (controls imperial guards), the Minister of Justice/廷尉 (oversees judicial system), the Minister of Attendants/郎中令 (controls palace guards, oversees imperial household, serves as imperial advisor, etc.), the Minister Coachman/太仆 (oversees the care, training, use, and purchase of horses; horses were an important resource in ancient times), the Lesser Treasurer/少府 (oversees the emperor's personal finances and some taxes), and the Minister of Ceremonies/奉常 (handles official ceremonies, worship, and rituals, oversees court astrologers and court scribes/historians).

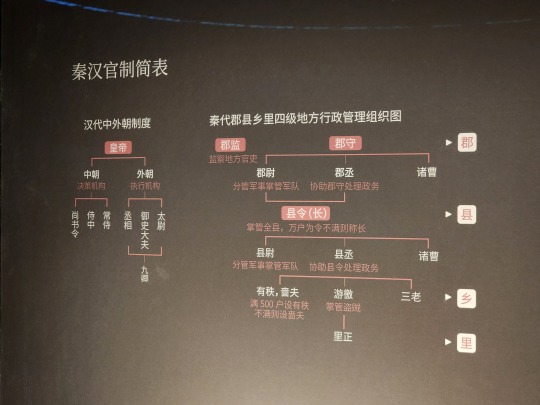

Qin and Han dynasty bureacratic systems. Right is Qin dynasty's system of commanderies/郡, counties/县, townships/乡, and villages/里 (levels of local government from highest to lowest). Left is Han dynasty's central government system, which designated the Three Lords and Nine Ministers system as the Outer Court/外朝 (executes policies), and added a Central Court/中朝 (decides policies).

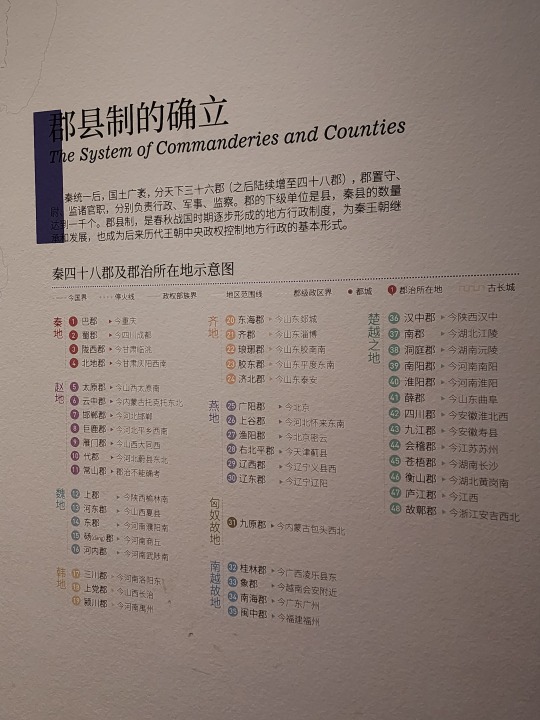

A list of the 48 commanderies during Qin dynasty and their locations today, grouped by where they were located before Qin dynasty (for example 7 of these groups were states during the Warring States period). A few of the names of these commanderies continue to be place names today, and some others often make appearances in modern novels.

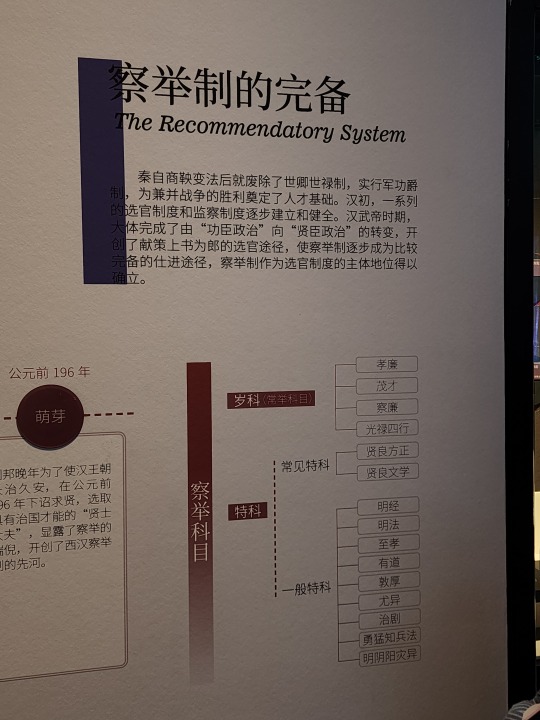

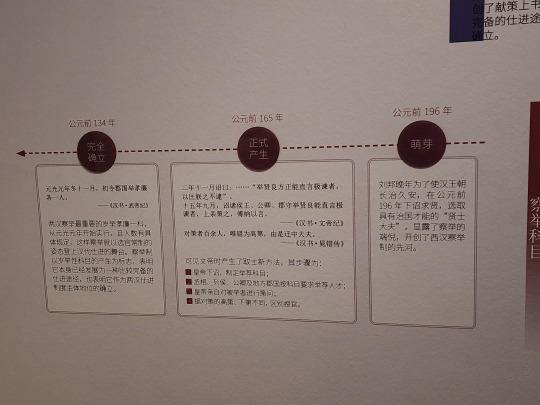

The Recommendatory System/察举制 of Han dynasty, which was how officials were selected. Basically this process consists of a few steps: first the emperor would set what categories of talents are needed, then local government would recommend people to the central government accordingly. The emperor would ask the recommendees how they would deal with current issues, and then gave them positions based on how good their policy ideas were. Ideally the local officials would be impartial with recommendations, but in reality the local officials often belonged to powerful local clans, so these recommendations gradually became a way for the powerful clans to stay in power. This system was replaced by the Imperial Examination System/科举制 in later dynasties, which put more emphasis on exams as a way to select talents.

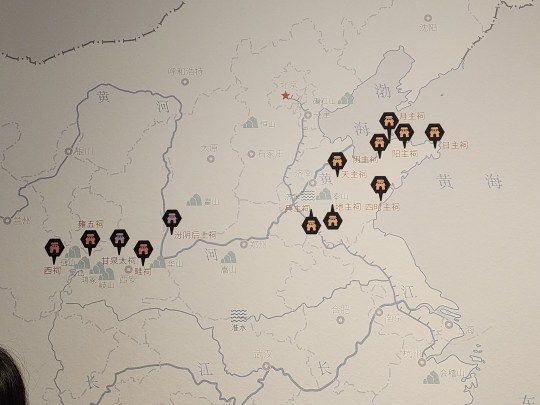

The locations of Qin and Han dynasty national temples, sacred mountains, and sacred bodies of water on a modern map. Of these, the temples marked in yellow were the temples dedicated to eight deities worshipped by the state of Qi, so they are collectively called the Eight Deities of Qi/齐地八神. Although the state of Qin eventually defeated the state of Qi, worship of these deities continued through Qin dynasty into Han dynasty. The temples marked in red were dedicated to deities worshipped by the state of Qin. The temples marked in purple were temples built in Han dynasty. The sacred waters are marked with wavy lines. The sacred mountains are marked in light blue-gray (a few are outside of this picture). MDZS fans may recognize Qishan/岐山 on this map, and Three Kingdoms enthusiasts may recognize jieshishan/碣石山 as the place Cao Cao visited when he wrote the line "东���碣石,以观沧海" in his famous poem.

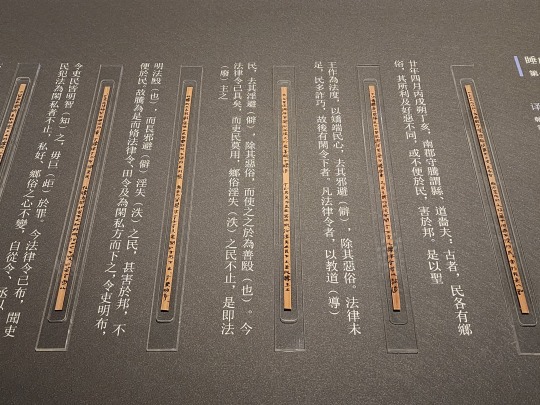

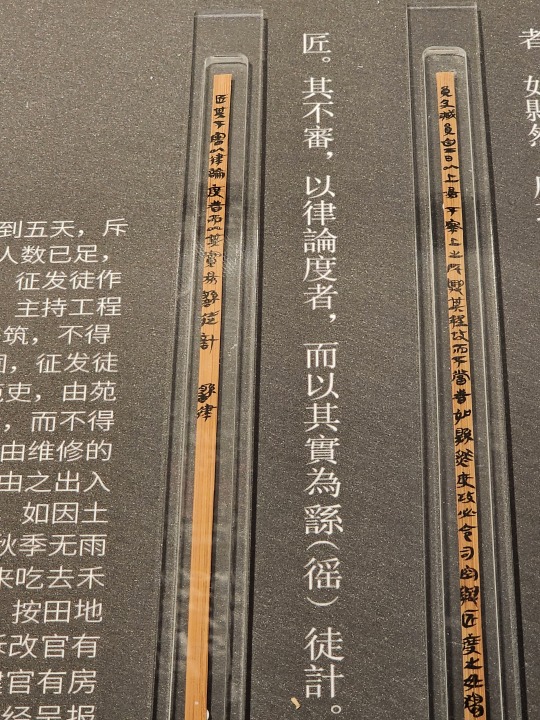

Replicas of a small part of the Qin-era bamboo texts found in a tomb of a Qin dynasty official at Shuihudi (睡虎地秦简). The originals are at Hubei Provincial Museum/湖北省博物馆. Many of these texts concern laws and decrees of Qin dynasty, and in another tomb in the same area there were also the oldest letters ever found in China (link goes to the full digitized text). These bamboo slips are meant to read from top to bottom, right to left, and the construction of bamboo scrolls are actually the very reason why Chinese texts read this way traditionally even on printed texts during later dynasties.

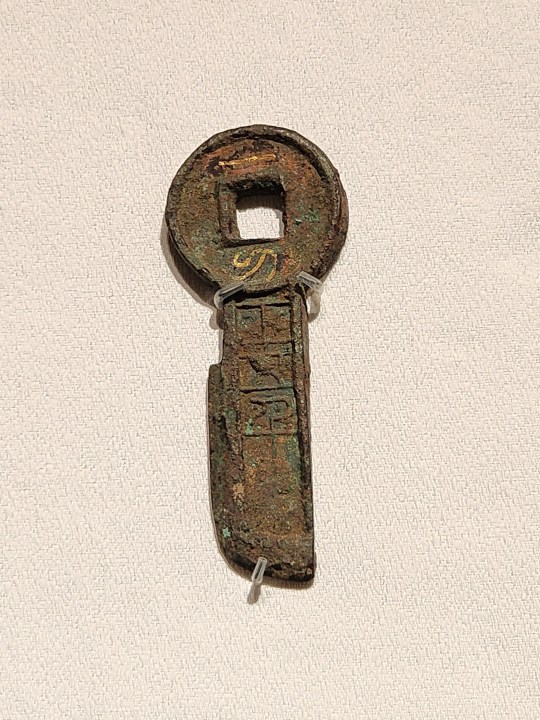

This was something I'd written about in the MDZS posts a few years ago, and now I've finally seen the real thing with my own eyes: the Tiger Tally/虎符 (I translated it as "Tiger Amulet" in that post but in fact "Tally" is the correct translation). Tiger tallys have two halves, each with gilded gold text upon them. This particular artifact is the left half of a tiger tally from late Warring States period (state of Qin), and reads:

"This is a tally of the armed forces, right half goes to the ruler of Qin, left half goes to (the official of) Du county. When the need to dispatch armored troops of over 50 soldiers arises, this half must find the other half held by the ruler in order to authorize this military activity. In case of emergency, there is no need to wait for this authorization." (“兵甲之符,右才君,左才杜。凡兴士披甲用兵五十人以上,必会君符,乃敢行之。燔燧之事,虽毋会符,行殹。”)

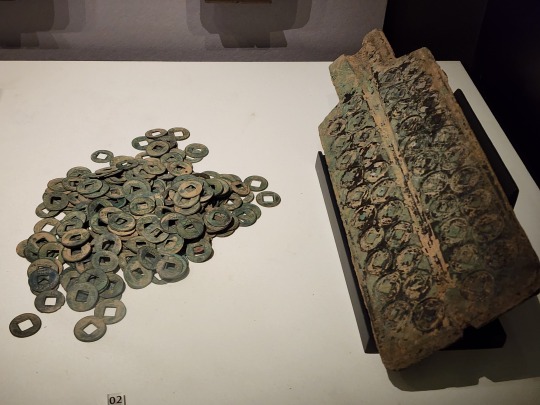

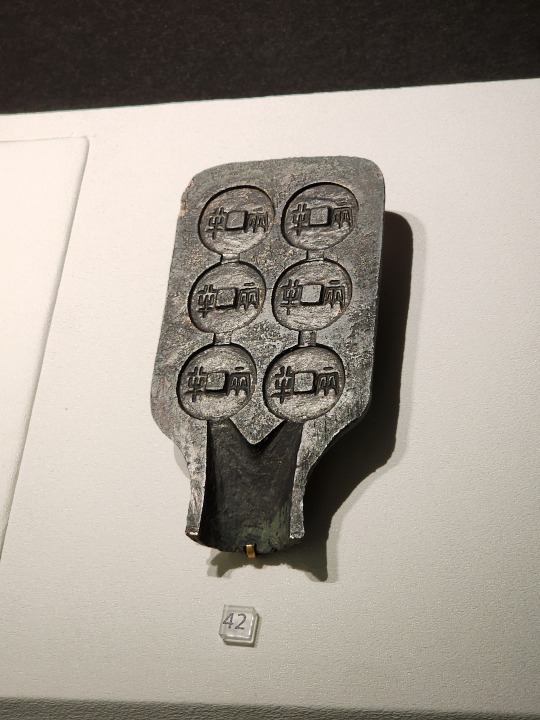

The different currencies (coins) of the states of Warring States period:

The different coins and coin molds during Qin and Han dynasties:

Left: Han dynasty disk-shaped gold ingots; these were rare currencies at the time and were mainly exchanged between the imperial family and nobility as gifts. Right: a standard weight from Qin dynasty that reads "weighs 30 jin/斤". Since Qin dynasty unified systems of measurements, and this weight is known to weigh 7.5 kg, we can easily convert the Qin-era jin to the modern kg (1 Qin-era jin = 0.25 kg).

Terra cotta soldier and horse from Qin Shihuang's mausoleum. As some people have pointed out, these terra cotta soldiers were fully painted and colorful when they were first excavated, but when exposed to air, the paint quickly peeled and the colors faded, leaving the sculptures in their familiar clay-color. Few of these sculptures still have their original colors intact, thanks to preservation efforts. The immense difficulty of preservation is also a reason why modern Chinese archaeology has that rule of "don't excavate unless absolutely necessary".

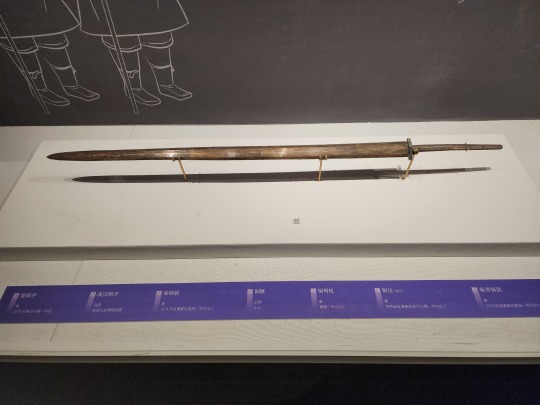

A Qin-era bronze jian/剑 (double-edged straight sword) from Qin Shihuang's mausoleum:

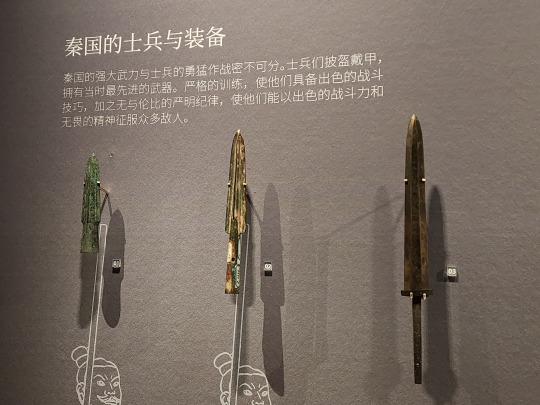

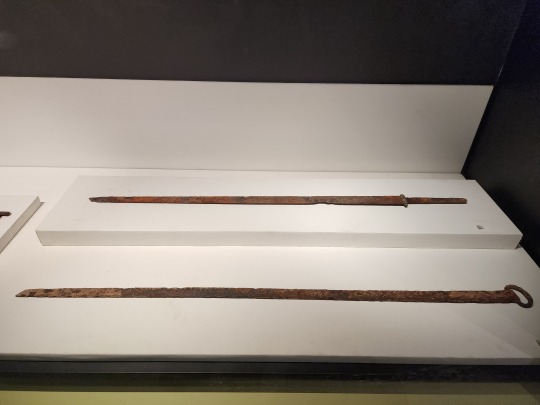

Left: Qin-era bronze spear heads and a pi/铍 head (on the right; pi is a type of ancient Chinese polearm). Right: Han-era ring-pommel dao/环首刀 (dao is a single-edged sword that can be straight or curved; interestingly, many ring-pommel dao artifacts exhibit a forward curve). Ring-pommel dao continued to be used in the military after Han dynasty.

A suit of armor made out of stone from Qin Shihuang's mausoleum. These armor sets weigh about 18 kg or 39.7 lbs each, which is........actually not too bad. There are specialized armor sets in later dynasties that can weigh 30 kg or 66 lbs.

#2024 china#xi'an#china#shaanxi history museum qin and han dynasties branch#chinese history#qin dynasty#han dynasty#warring states period#three kingdoms#history#archaeology#mdzs

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝟷𝟶 𝚏𝚞𝚗 𝚏𝚊𝚌𝚝𝚜 𝚊𝚋𝚘𝚞𝚝 𝚊𝚜𝚝𝚛𝚘𝚕𝚘𝚐𝚢

1. sign ≠ house- the reason this is, is because they both have their own characteristics and also represent different meanings. the signs represent more of a personality and the houses represent aspects of your life. they correspond but they aren’t the same thing. this is because when you think about it, aries has qualities such as leadership and impulsivity, but the 1st house doesn’t represent those things. therefore they’re not the same thing. when you see post that say aries/ 1st house, it’s usually because they try to add aspects of both placements

2. there’s multiple kinds of astrology- most people that live in america follow western astrology, but there’s vedic astrology which is said to be the most accurate, chinese astrology, medical astrology, and more. they are all different but also similar and some ways

3. there’s multiple charts in astrology- this is one of my favorite parts about astrology but it can also get confusing lol. there’s your natal chart, which everyone knows about, but then there’s persona charts, transit charts, progressive charts, draconic charts and more. then synastry and composite charts which takes 2 people’s birth information to create

4. asteroids- you don’t have to only learn about planets, you can learn about asteroids too. asteroids usually fall between 2 planets, which somewhat helps form a personality for them. not all of them though, some of them are in the outskirts of our solar system and some have meanings that don’t necessarily relate to the planet it’s closest to

5. there’s thousands of asteroids- there’s so many asteroids out there, that have been discovered with in depth meanings, some that have been discovered with no clear meaning, and obviously some that still aren’t discovered. that’s why there’s so many different elements to your chart, and so many different things can dictate your personality in a natal chart

6. greek mythology and astrology- greek mythology and astrology have a lot of points where they correlate. especially with asteroids, if you read into greek mythology, you will start to understand why certain asteroids and placements mean the things they do

7. cusp- if you believe in degrees in astrology, then you don’t believe in cusp. cusp basically means when you were born “between” 2 signs. so people born on may 20th or 21st could say they’re a taurus/gemini cusp, but that’s not true if you believe in degrees. degrees can go from 0 to 29

8. no such thing as a bad placement- no placement is bad, some are just harder to deal with than others and that’s okay. it doesn’t mean parts of you or bad or that your cursed for the rest of your life. everyone has rough edges, you just have to smooth them out if that makes sense lol

9. astrology and tarot- some major arcana cards actually represent the zodiac signs. not all of them but about half of them do. like gemini is the lovers, aquarius is the star, libra is judgement, and so on

10. empty houses- technically no house is empty because like i mentioned earlier, there’s thousands of asteroids out there, and all of them fall in a house. but as for your natal chart, having an empty house doesn’t mean anything negative, it just means that’s an aspect of yourself you don’t really need to focus on or pay attention to, or nothing is really going to happen in those areas of life. if you have an empty 4th house it can mean that nothing significant or out of the ordinary or specific is going to happen to your family or children. i hope that made sense 💀

#astro community#astro observations#astro placements#astro posts#astrology#zodiac shit#gemini#capricorn#aries#scorpio#astrology ask#astrology community#astrology notes#astrology aspects#astrology stuff#astro notes#astrology chart#natal astrology#astrology signs#astroblr

278 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shikigami and onmyōdō through history: truth, fiction and everything in between

Abe no Seimei exorcising disease spirits (疫病神, yakubyōgami), as depicted in the Fudō Riyaku Engi Emaki. Two creatures who might be shikigami are visible in the bottom right corner (wikimedia commons; identification following Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage, pp. 57-58)

In popular culture, shikigami are basically synonymous with onmyōdō. Was this always the case, though? And what is a shikigami, anyway? These questions are surprisingly difficult to answer. I’ve been meaning to attempt to do so for a longer while, but other projects kept getting in the way. Under the cut, you will finally be able to learn all about this matter.

This isn’t just a shikigami article, though. Since historical context is a must, I also provide a brief history of onmyōdō and some of its luminaries. You will also learn if there were female onmyōji, when stars and time periods turn into deities, what onmyōdō has to do with a tale in which Zhong Kui became a king of a certain city in India - and more!

The early days of onmyōdō In order to at least attempt to explain what the term shikigami might have originally entailed, I first need to briefly summarize the history of onmyōdō (陰陽道). This term can be translated as “way of yin and yang”, and at the core it was a Japanese adaptation of the concepts of, well, yin and yang, as well as the five elements. They reached Japan through Daoist and Buddhist sources. Daoism itself never really became a distinct religion in Japan, but onmyōdō is arguably among the most widespread adaptations of its principles in Japanese context.

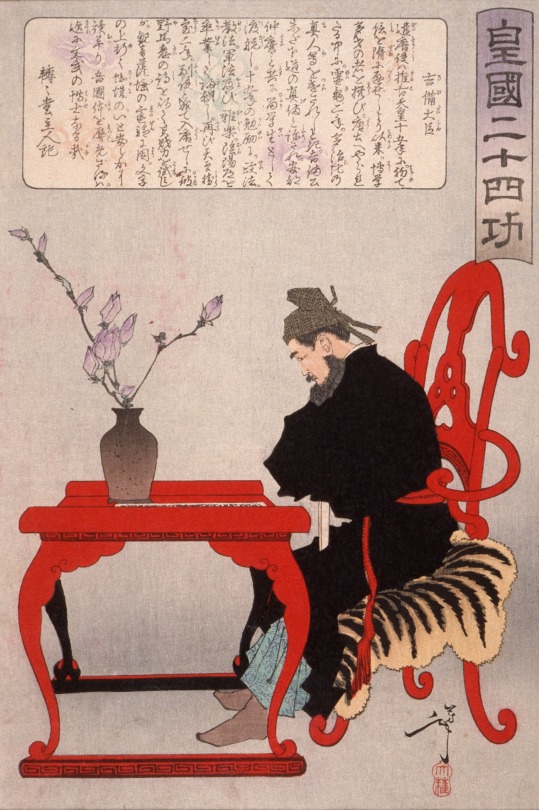

Kibi no Makibi, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

It’s not possible to speak of a singular founder of onmyōdō comparable to the patriarchs of Buddhist schools. Bernard Faure notes that in legends the role is sometimes assigned to Kibi no Makibi, an eighth century official who spent around 20 years in China. While he did bring many astronomical treatises with him when he returned, this is ultimately just a legend which developed long after he passed away.

In reality onmyōdō developed gradually starting with the sixth century, when Chinese methods of divination and treatises dealing with these topics first reached Japan. Early on Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje were the main sources of this knowledge. We know for example that the Soga clan employed such a specialist, a certain Gwalleuk (観勒; alternatively known under the Japanese reading of his name, Kanroku).

Obviously, divination was viewed as a very serious affair, so the imperial court aimed to regulate the continental techniques in some way. This was accomplished by emperor Tenmu with the formation of the onmyōryō (陰陽寮), “bureau of yin and yang” as a part of the ritsuryō system of governance. Much like in China, the need to control divination was driven by the fears that otherwise it would be used to legitimize courtly intrigues against the emperor, rebellions and other disturbances. Officials taught and employed by onmyōryō were referred to as onmyōji (陰陽師). This term can be literally translated as “yin-yang master”. In the Nara period, they were understood essentially as a class of public servants. Their position didn’t substantially differ from that of other specialists from the onmyōryō: calendar makers, officials responsible for proper measurement of time and astrologers. The topics they dealt with evidently weren’t well known among commoners, and they were simply typical members of the literate administrative elite of their times.

Onmyōdō in the Heian period: magic, charisma and nobility

The role of onmyōji changed in the Heian period. They retained the position of official bureaucratic diviners in employ of the court, but they also acquired new duties. The distinction between them and other onmyōryō officials became blurred. Additionally their activity extended to what was collectively referred to as jujutsu (呪術), something like “magic” though this does not fully reflect the nuances of this term. They presided over rainmaking rituals, purification ceremonies, so-called “earth quelling”, and establishing complex networks of temporal and directional taboos.

A Muromachi period depiction of Abe no Seimei (wikimedia commons)

The most famous historical onmyōji like Kamo no Yasunori and his student Abe no Seimei were active at a time when this version of onmyōdō was a fully formed - though obviously still evolving - set of practices and beliefs. In a way they represented a new approach, though - one in which personal charisma seemed to matter just as much, if not more, than official position. This change was recognized as a breakthrough by at least some of their contemporaries. For example, according to the diary of Minamoto no Tsuneyori, the Sakeiki (左經記), “in Japan, the foundations of onmyōdō were laid by Yasunori”.

The changes in part reflected the fact that onmyōji started to be privately contracted for various reasons by aristocrats, in addition to serving the state. Shin’ichi Shigeta notes that it essentially turned them from civil servants into tradespeople. However, he stresses they cannot be considered clergymen: their position was more comparable to that of physicians, and there is no indication they viewed their activities as a distinct religion. Indeed, we know of multiple Heian onmyōji, like Koremune no Fumitaka or Kamo no Ieyoshi, who by their own admission were devout Buddhists who just happened to work as professional diviners.

Shin’ichi Shigeta notes is evidence that in addition to the official, state-sanctioned onmyōji, “unlicensed” onmyōji who acted and dressed like Buddhist clergy, hōshi onmyōji (法師陰陽師) existed. The best known example is Ashiya Dōman, a mainstay of Seimei legends, but others are mentioned in diaries, including the famous Pillow Book. It seems nobles particularly commonly employed them to curse rivals. This was a sphere official onmyōji abstained from due to legal regulations. Curses were effectively considered crimes, and government officials only performed apotropaic rituals meant to protect from them. The Heian period version of onmyōdō captivated the imagination of writers and artists, and its slightly exaggerated version present in classic literature like Konjaku Monogatari is essentially what modern portrayals in fiction tend to go back to.

Medieval onmyōdō: from abstract concepts to deities

Gozu Tennō (wikimedia commons)

Further important developments occurred between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. This period was the beginning of the Japanese “middle ages” which lasted all the way up to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. The focus in onmyōdō in part shifted towards new, or at least reinvented, deities, such as calendarical spirits like Daishōgun (大将軍) and Ten’ichijin (天一神), personifications of astral bodies and concepts already crucial in earlier ceremonies. There was also an increased interest in Chinese cosmological figures like Pangu, reimagined in Japan as “king Banko”. However, the most famous example is arguably Gozu Tennō, who you might remember from my Susanoo article.

The changes in medieval onmyōdō can be described as a process of convergence with esoteric Buddhism. The points of connection were rituals focused on astral and underworld deities, such as Taizan Fukun or Shimei (Chinese Siming). Parallels can be drawn between this phenomenon and the intersection between esoteric Buddhism and some Daoist schools in Tang China. Early signs of the development of a direct connection between onmyōdō and Buddhism can already be found in sources from the Heian period, for example Kamo no Yasunori remarked that he and other onmyōji depend on the same sources to gain proper understanding of ceremonies focused on the Big Dipper as Shingon monks do.

Much of the information pertaining to the medieval form of onmyōdō is preserved in Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), a text which is part divination manual and part a collection of myths. According to tradition it was compiled by Abe no Seimei, though researchers generally date it to the fourteenth century. For what it’s worth, it does seem likely its author was a descendant of Seimei, though. Outside of specialized scholarship Hoki Naiden is fairly obscure today, but it’s worth noting that it was a major part of the popular perception of onmyōdō in the Edo period. A novel whose influence is still visible in the modern image of Seimei, Abe no Seimei Monogatari (安部晴明物語), essentially revolves around it, for instance.

Onmyōdō in the Edo period: occupational licensing

Novels aside, the first post-medieval major turning point for the history of onmyōdō was the recognition of the Tsuchimikado family as its official overseers in 1683. They were by no means new to the scene - onmyōji from this family already served the Ashikaga shoguns over 250 years earlier. On top of that, they were descendants of the earlier Abe family, the onmyōji par excellence. The change was not quite the Tsuchimikado’s rise, but rather the fact the government entrusted them with essentially regulating occupational licensing for all onmyōji, even those who in earlier periods existed outside of official administration.

As a result of the new policies, various freelance practitioners could, at least in theory, obtain a permit to perform the duties of an onmyōji. However, as the influence of the Tsuchimikado expanded, they also sought to oblige various specialists who would not be considered onmyōji otherwise to purchase licenses from them. Their aim was to essentially bring all forms of divination under their control. This extended to clergy like Buddhist monks, shugenja and shrine priests on one hand, and to various performers like members of kagura troupes on the other.

Makoto Hayashi points out that while throughout history onmyōji has conventionally been considered a male occupation, it was possible for women to obtain licenses from the Tsuchimikado. Furthermore, there was no distinct term for female onmyōji, in contrast with how female counterparts of Buddhist monks, shrine priests and shugenja were referred to with different terms and had distinct roles defined by their gender. As far as I know there’s no earlier evidence for female onmyōji, though, so it’s safe to say their emergence had a lot to do with the specifics of the new system. It seems the poems of the daughter of Kamo no Yasunori (her own name is unknown) indicate she was familiar with yin-yang theory or at least more broadly with Chinese philosophy, but that’s a topic for a separate article (stay tuned), and it's not quite the same, obviously.

The Tsuchimikado didn’t aim to create a specific ideology or systems of beliefs. Therefore, individual onmyōji - or, to be more accurate, individual people with onmyōji licenses - in theory could pursue new ideas. This in some cases lead to controversies: for instance, some of the people involved in the (in)famous 1827 Osaka trial of alleged Christians (whether this label really is applicable is a matter of heated debate) were officially licensed onmyōji. Some of them did indeed possess translated books written by Portuguese missionaries, which obviously reflected Catholic outlook. However, Bernard Faure suggests that some of the Edo period onmyōji might have pursued Portuguese sources not strictly because of an interest in Catholicism but simply to obtain another source of astronomical knowledge.

The legacy of onmyōdō

In the Meiji period, onmyōdō was banned alongside shugendō. While the latter tradition experienced a revival in the second half of the twentieth century, the former for the most part didn’t. However, that doesn’t mean the history of onmyōdō ends once and for all in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Even today in some parts of Japan there are local religious traditions which, while not identical with historical onmyōdō, retain a considerable degree of influence from it. An example often cited in scholarship is Izanagi-ryū (いざなぎ流) from the rural Monobe area in the Kōchi Prefecture. Mitsuki Ueno stresses that the occasional references to Izanagi-ryū as “modern onmyōdō” in literature from the 1990s and early 2000s are inaccurate, though. He points out they downplay the unique character of this tradition, and that it shows a variety of influences. Similar arguments have also been made regarding local traditions from the Chūgoku region.

Until relatively recently, in scholarship onmyōdō was basically ignored as superstition unworthy of serious inquiries. This changed in the final decades of the twentieth century, with growing focus on the Japanese middle ages among researchers. The first monographs on onmyōdō were published in the 1980s. While it’s not equally popular as a subject of research as esoteric Buddhism and shugendō, formerly neglected for similar reasons, it has nonetheless managed to become a mainstay of inquiries pertaining to the history of religion in Japan.

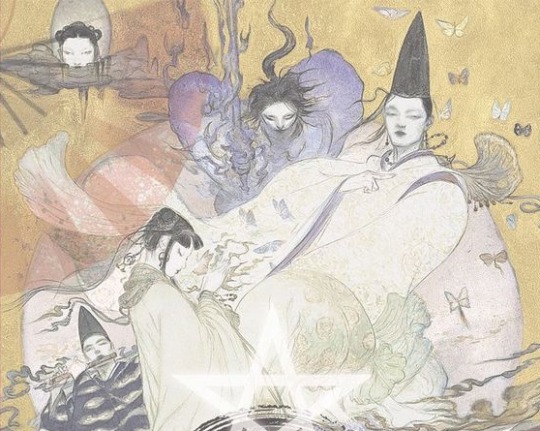

Yoshitaka Amano's illustration of Baku Yumemakura's fictionalized portrayal of Abe no Seimei (right) and other characters from his novels (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Of course, it’s also impossible to talk about onmyōdō without mentioning the modern “onmyōdō boom”. Starting with the 1980s, onmyōdō once again became a relatively popular topic among writers. Novel series such as Baku Yumemakura’s Onmyōji, Hiroshi Aramata’s Teito Monogatari or Natsuhiko Kyōgoku’s Kyōgōkudō and their adaptations in other media once again popularized it among general audiences. Of course, since these are fantasy or mystery novels, their historical accuracy tends to vary (Yumemakura in particular is reasonably faithful to historical literature, though). Still, they have a lasting impact which would be impossible to accomplish with scholarship alone.

Shikigami: historical truth, historical fiction, or both?

You might have noticed that despite promising a history of shikigami, I haven’t used this term even once through the entire crash course in history of onmyōdō. This was a conscious choice. Shikigami do not appear in any onmyōdō texts, even though they are a mainstay of texts about onmyōdō, and especially of modern literature involving onmyōji.

It would be unfair to say shikigami and their prominence are merely a modern misconception, though. Virtually all of the famous legends about onmyōji feature shikigami, starting with the earliest examples from the eleventh century. Based on Konjaku Monogatari, there evidently was a fascination with shikigami at the time of its compilation. Fujiwara no Akihira in the Shinsarugakuki treats the control of shikigami as an essential skill of an onmyōji, alongside the abilities to “freely summon the twelve guardian deities, call thirty-six types of wild birds (...), create spells and talismans, open and close the eyes of kijin (鬼神; “demon gods”), and manipulate human souls”.

It is generally agreed that such accounts, even though they belong to the realm of literary fiction, can shed light on the nature and importance of shikigami. They ultimately reflect their historical context to some degree. Furthermore, it is not impossible that popular understanding of shikigami based on literary texts influenced genuine onmyōdō tradition. It’s worth pointing out that today legends about Abe no Seimei involving them are disseminated by two contemporary shrines dedicated to him, the Seimei Shrine (晴明神社) in Kyoto and the Abe no Seimei Shrine (安倍晴明神社) in Osaka. Interconnected networks of exchange between literature and religious practice are hardly a unique or modern phenomenon.

However, even with possible evidence from historical literature taken into account, it is not easy to define shikigami. The word itself can be written in three different ways: 式神 (or just 式), 識神 and 職神, with the first being the default option. The descriptions are even more varied, which understandably lead to the rise of numerous interpretations in modern scholarship. Carolyn Pang in her recent treatments of shikigami, which you can find in the bibliography, has recently divided them into five categories. I will follow her classification below.

Shikigami take 1: rikujin-shikisen

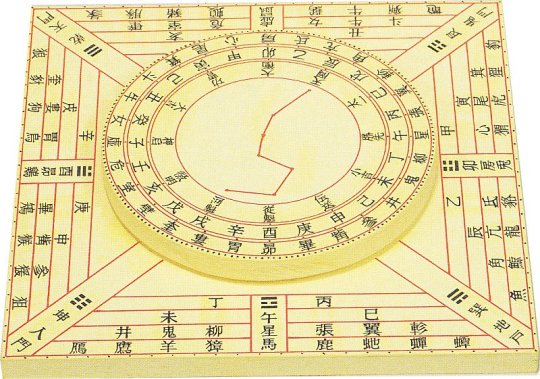

An example of shikiban, the divination board used in rikujin-shikisen (Museum of Kyoto, via onmarkproductions.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

A common view is that shikigami originate as a symbolic representation of the power of shikisen (式占) or more specifically rikujin-shikisen (六壬式占), the most common form of divination in onmyōdō. It developed from Chinese divination methods in the Nara period, and remained in the vogue all the way up to the sixteenth century, when it was replaced by ekisen (易占), a method derived from the Chinese Book of Changes.

Shikisen required a special divination board known as shikiban (式盤), which consists of a square base, the “earth panel” (地盤, jiban), and a rotating circle placed on top of it, the “heaven panel” (天盤, tenban). The former was marked with twelve points representing the signs of the zodiac and the latter with representations of the “twelve guardians of the months” (十二月将, jūni-gatsushō; their identity is not well defined). The heaven panel had to be rotated, and the diviner had to interpret what the resulting combination of symbols represents. Most commonly, it was treated as an indication whether an unusual phenomenon (怪/恠, ke) had positive or negative implications. It’s worth pointing out that in the middle ages the shikiban also came to be used in some esoteric Buddhist rituals, chiefly these focused on Dakiniten, Shōten and Nyoirin Kannon. However, they were only performed between the late Heian and Muromachi periods, and relatively little is known about them. In most cases the divination board was most likely modified to reference the appropriate esoteric deities.

Shikigami take 2: cognitive abilities

While the view that shikigami represented shikisen is strengthened by the fact both terms share the kanji 式, a variant writing, 識神, lead to the development of another proposal. Since the basic meaning of 識 is “consciousness”, it is sometimes argued that shikigami were originally an “anthropomorphic realization of the active psychological or mental state”, as Caroline Pang put it - essentially, a representation of the will of an onmyōji. Most of the potential evidence in this case comes from Buddhist texts, such as Bosatsushotaikyō (菩薩処胎経).

However, Bernard Faure assumes that the writing 識神 was a secondary reinterpretation, basically a wordplay based on homonymy. He points out the Buddhist sources treat this writing of shikigami as a synonym of kushōjin (倶生神). This term can be literally translated as “deities born at the same time”. Most commonly it designates a pair of minor deities who, as their name indicates, come into existence when a person is born, and then records their deeds through their entire life. Once the time for Enma’s judgment after death comes, they present him with their compiled records. It has been argued that they essentially function like a personification of conscience.

Shikigami take 3: energy

A further speculative interpretation of shikigami in scholarship is that this term was understood as a type of energy present in objects or living beings which onmyōji were believed to be capable of drawing out and harnessing to their ends. This could be an adaptation of the Daoist notion of qi (氣). If this definition is correct, pieces of paper or wooden instruments used in purification ceremonies might be examples of objects utilized to channel shikigami.

The interpretation of shikigami as a form of energy is possibly reflected in Konjaku Monogatari in the tale The Tutelage of Abe no Seimei under Tadayuki. It revolves around Abe no Seimei’s visit to the house of the Buddhist monk Kuwanten from Hirosawa. Another of his guests asks Seimei if he is capable of killing a person with his powers, and if he possesses shikigami. He affirms that this is possible, but makes it clear that it is not an easy task. Since the guests keep urging him to demonstrate nonetheless, he promptly demonstrates it using a blade of grass. Once it falls on a frog, the animal is instantly crushed to death. From the same tale we learn that Seimei’s control over shikigami also let him remotely close the doors and shutters in his house while nobody was inside.

Shikigami take 4: curse As I already mentioned, arts which can be broadly described as magic - like the already mentioned jujutsu or juhō (呪法, “magic rituals”) - were regarded as a core part of onmyōji’s repertoire from the Heian period onward. On top of that, the unlicensed onmyōji were almost exclusively associated with curses. Therefore, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that yet another theory suggests shikigami is simply a term for spells, curses or both. A possible example can be found in Konjaku Monogatari, in the tale Seimei sealing the young Archivist Minor Captains curse - the eponymous curse, which Seimei overcomes with protective rituals, is described as a shikigami.

Kunisuda Utagawa's illustration of an actor portraying Dōman in a kabuki play (wikimedia commons)

Similarities between certain descriptions of shikigami and practices such as fuko (巫蠱) and goraihō (五雷法) have been pointed out. Both of these originate in China. Fuko is the use of poisonous, venomous or otherwise negatively perceived animals to create curses, typically by putting them in jars, while goraihō is the Japanese version of Daoist spells meant to control supernatural beings, typically ghosts or foxes. It’s worth noting that a legend according to which Dōman cursed Fujiwara no Michinaga on behalf of lord Horikawa (Fujiwara no Akimitsu) involves him placing the curse - which is itself not described in detail - inside a jar.

Mitsuki Ueno notes that in the Kōchi Prefecture the phrase shiki wo utsu, “to strike with a shiki”, is still used to refer to cursing someone. However, shiki does not necessarily refer to shikigami in this context, but rather to a related but distinct concept - more on that later.

Shikigami take 5: supernatural being

While all four definitions I went through have their proponents, yet another option is by far the most common - the notion of shikigami being supernatural beings controlled by an onmyōji. This is essentially the standard understanding of the term today among general audiences. Sometimes attempts are made to identify it with a specific category of supernatural beings, like spirits (精霊, seirei), kijin or lesser deities (下級神, kakyū shin). However, none of these gained universal support. Generally speaking, there is no strong indication that shikigami were necessarily imagined as individualized beings with distinct traits.

The notion of shikigami being supernatural beings is not just a modern interpretation, though, for the sake of clarity. An early example where the term is unambiguously used this way is a tale from Ōkagami in which Seimei sends a nondescript shikigami to gather information. The entity, who is not described in detail, possesses supernatural skills, but simultaneously still needs to open doors and physically travel.

An illustration from Nakifudō Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

In Genpei Jōsuiki there is a reference to Seimei’s shikigami having a terrifying appearance which unnerved his wife so much he had to order the entities to hide under a bride instead of residing in his house. Carolyn Pang suggests that this reflects the demon-like depictions from works such as Abe no Seimei-kō Gazō (安倍晴明公画像; you can see it in the Heian section), Fudōriyaku Engi Emaki and Nakifudō Engi Emaki.

Shikigami and related concepts

A gohō dōji, as depicted in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The understanding of shikigami as a “spirit servant” of sorts can be compared with the Buddhist concept of minor protective deities, gohō dōji (護法童子; literally “dharma-protecting lads”). These in turn were just one example of the broad category of gohō (護法), which could be applied to virtually any deity with protective qualities, like the historical Buddha’s defender Vajrapāṇi or the Four Heavenly Kings. A notable difference between shikigami and gohō is the fact that the former generally required active summoning - through chanting spells and using mudras - while the latter manifested on their own in order to protect the pious. Granted, there are exceptions. There is a well attested legend according to which Abe no Seimei’s shikigami continued to protect his residence on own accord even after he passed away. Shikigami acting on their own are also mentioned in Zoku Kojidan (��古事談). It attributes the political downfall of Minamoto no Takaakira (源高明; 914–98) to his encounter with two shikigami who were left behind after the onmyōji who originally summoned them forgot about them.

A degree of overlap between various classes of supernatural helpers is evident in texts which refer to specific Buddhist figures as shikigami. I already brought up the case of the kushōjin earlier. Another good example is the Tendai monk Kōshū’s (光宗; 1276–1350) description of Oto Gohō (乙護法). He is “a shikigami that follows us like the shadow follows the body. Day or night, he never withdraws; he is the shikigami that protects us” (translation by Bernard Faure). This description is essentially a reversal of the relatively common title “demon who constantly follow beings” (常随魔, jōzuima). It was applied to figures such as Kōjin, Shōten or Matarajin, who were constantly waiting for a chance to obstruct rebirth in a pure land if not placated properly.

The Twelve Heavenly Generals (Tokyo National Museum, via wikimedia commons)

A well attested group of gohō, the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō), and especially their leader Konpira (who you might remember from my previous article), could be labeled as shikigami. However, Fujiwara no Akihira’s description of onmyōji skills evidently presents them as two distinct classes of beings.

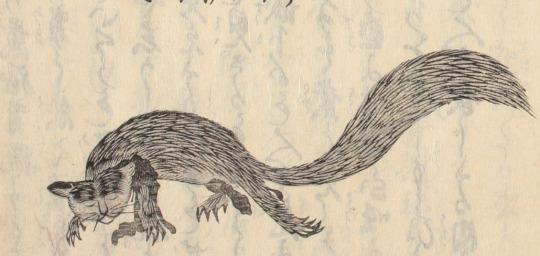

A kuda-gitsune, as depicted in Shōzan Chomon Kishū by Miyoshi Shōzan (Waseda University History Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Granted, Akihira also makes it clear that controlling shikigami and animals are two separate skills. Meanwhile, there is evidence that in some cases animal familiars, especially kuda-gitsune used by iizuna (a term referring to shugenja associated with the cult of, nomen omen, Iizuna Gongen, though more broadly also something along the lines of “sorcerer”), were perceived as shikigami.

Beliefs pertaining to gohō dōji and shikigami seemingly merged in Izanagi-ryū, which lead to the rise of the notion of shikiōji (式王子; ōji, literally “prince”, can be another term for gohō dōji). This term refers to supernatural beings summoned by a ritual specialist (祈祷師, kitōshi) using a special formula from doctrinal texts (法文, hōmon). They can fulfill various functions, though most commonly they are invoked to protect a person, to remove supernatural sources of diseases, to counter the influence of another shikiōji or in relation to curses.

Tenkeisei, the god of shikigami

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

The final matter which warrants some discussion is the unusual tradition regarding the origin of shikigami which revolves around a deity associated with this concept.

In the middle ages, a belief that there were exactly eighty four thousand shikigami developed. Their source was the god Tenkeisei (天刑星; also known as Tengyōshō). His name is the Japanese reading of Chinese Tianxingxing. It can be translated as “star of heavenly punishment”. This name fairly accurately explains his character. He was regarded as one of the so-called “baleful stars” (凶星, xiong xing) capable of controlling destiny. The “punishment” his name refers to is his treatment of disease demons (疫鬼, ekiki). However, he could punish humans too if not worshiped properly.

Today Tenkeisei is best known as one of the deities depicted in a series of paintings known as Extermination of Evil, dated to the end of the twelfth century. He has the appearance of a fairly standard multi-armed Buddhist deity. The anonymous painter added a darkly humorous touch by depicting him right as he dips one of the defeated demons in vinegar before eating him. Curiously, his adversaries are said to be Gozu Tennō and his retinue in the accompanying text. This, as you will quickly learn, is a rather unusual portrayal of the relationship between these two deities.

I’m actually not aware of any other depictions of Tenkeisei than the painting you can see above. Katja Triplett notes that onmyōdō rituals associated with him were likely surrounded by an aura of secrecy, and as a result most depictions of him were likely lost or destroyed. At the same time, it seems Tenkeisei enjoyed considerable popularity through the Kamakura period. This is not actually paradoxical when you take the historical context into account: as I outlined in my recent Amaterasu article, certain categories of knowledge were labeled as secret not to make their dissemination forbidden, but to imbue them with more meaning and value.

Numerous talismans inscribed with Tenkeisei’s name are known. Furthermore, manuals of rituals focused on him have been discovered. The best known of them, Tenkeisei-hō (天刑星法; “Tenkeisei rituals”), focuses on an abisha (阿尾捨, from Sanskrit āveśa), a ritual involving possession by the invoked deity. According to a legend was transmitted by Kibi no Makibi and Kamo no Yasunori. The historicity of this claim is doubtful, though: the legend has Kamo no Yasunori visit China, which he never did. Most likely mentioning him and Makibi was just a way to provide the text with additional legitimacy.

Other examples of similar Tenkeisei manuals include Tenkeisei Gyōhō (天刑星行法; “Methods of Tenkeisei Practice”) and Tenkeisei Gyōhō Shidai (天刑星行法次第; “Methods of Procedure for the Tenkeisei Practice”). Copies of these texts have been preserved in the Shingon temple Kōzan-ji.

The Hoki Naiden also mentions Tenkeisei. It equates him with Gozu Tennō, and explains both of these names refer to the same deity, Shōki (商貴), respectively in heaven and on earth. While Shōki is an adaptation of the famous Zhong Kui, it needs to be pointed out that here he is described not as a Tang period physician but as an ancient king of Rajgir in India. Furthermore, he is a yaksha, not a human. This fairly unique reinterpretation is also known from the historical treatise Genkō Shakusho. Post scriptum The goal of this article was never to define shikigami. In the light of modern scholarship, it’s basically impossible to provide a single definition in the first place. My aim was different: to illustrate that context is vital when it comes to understanding obscure historical terms. Through history, shikigami evidently meant slightly different things to different people, as reflected in literature. However, this meaning was nonetheless consistently rooted in the evolving perception of onmyōdō - and its internal changes. In other words, it reflected a world which was fundamentally alive. The popular image of Japanese culture and religion is often that of an artificial, unchanging landscape straight from the “age of the gods”, largely invented in the nineteenth century or later to further less than noble goals. The case of shikigami proves it doesn’t need to be, though. The malleable, ever-changing image of shikigami, which remained a subject of popular speculation for centuries before reemerging in a similar role in modern times, proves that the more complex reality isn’t necessarily any less interesting to new audiences.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, A Religion in Search of a Founder?

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Makoto Hayashi, The Female Christian Yin-Yang Master

Jun’ichi Koike, Onmyōdō and Folkloric Culture: Three Perspectives for the Development of Research

Irene H. Lin, Child Guardian Spirits (Gohō Dōji) in the Medieval Japanese Imaginaire

Yoshifumi Nishioka, Aspects of Shikiban-Based Mikkyō Rituals

Herman Ooms, Yin-Yang's Changing Clientele, 600-800 (note there is n apparent mistake in one of the footnotes, I'm pretty sure the author wanted to write Mesopotamian astronomy originated 4000 years ago, not 4 millenia BCE as he did; the latter date makes little sense)

Carolyn Pang, Spirit Servant: Narratives of Shikigami and Onmyōdō Developments

Idem, Uncovering Shikigami. The Search for the Spirit Servant of Onmyōdō

Shin’ichi Shigeta, Onmyōdō and the Aristocratic Culture of Everyday Life in Heian Japan

Idem, A Portrait of Abe no Seimei

Katja Triplett, Putting a Face on the Pathogen and Its Nemesis. Images of Tenkeisei and Gozutennō, Epidemic-Related Demons and Gods in Medieval Japan

Mitsuki Umeno, The Origins of the Izanagi-ryū Ritual Techniques: On the Basis of the Izanagi saimon

Katsuaki Yamashita, The Characteristics of On'yōdō and Related Texts

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

My OCs' jersey number explanations ramblings ^_^

Tsubasa - #13 (usual jersey)

Tsubasa's birthday is February 13. So purely in terms of personality, Tsubasa is egocentric and self-absorbed enough to use his birth date as his preferred jersey that he insists on wearing

Now onto the meta stuff:

Well we all know 13 is the cliched bad luck number in Western culture. Tsubasa in his backstory has many unlucky circumstances surrounding his life. Btw I know Gesner is #13 in BM but let's be honest Tsubasa is more important (my beloved oshi). I think it can also have a double meaning, unlucky number 13 as in you're unlucky to be against him rather than the sole fact that he, himself, is unlucky.

Tsubasa is a self-reliant person & player who always preserves so it can be a case of someone "making their own luck" no matter the circumstance as well.

He has a lot of strange beliefs and conventions so being symbolized by a superstitious number also fits him thematically. For example he believes in angels and the death-rebirth cycle and other such not scientifically proven to exist things.

Tsubasa's character has a theme surrounding an obsession with "death" both literal and symbolic (as his goal of self-realization and also his definition of "change" lies in "death" in his own mind, hence the obsession with "dying", and to him "death" is "repentance" for what he "has done", which according to him is "being born").

The death-rebirth cycle samsara is a Buddhist belief. In Japanese beliefs about Buddhist deities, there are thirteen Buddhas who also play an important role in traditional funerals (once again bringing it back to the theme of death and rebirth in his own personal belief system + as well as the fact that he veers spiritual).

The number 13 itself in astrology and tarot readings is sometimes associated with transformation and rebirth, and the End of one cycle onto the beginning of another. The "Death" card is number 13 in the major arcana - the card itself also symbolizes renewal.

In Japanese & Chinese numerology: 1 + 3 = 4, "shi" = death, traditonally four is considered unlucky in Japanese culture even if 13 itself isn't.

#42 - U-20 match jersey specifically

4 + 2 = "shini" = "to death", again considered an unlucky number, in Tsubasa's case more so means "I'll play to death", i.e. "I'll play until I'm renewed". It's also pretty edgy and contrarian all things considered since a superstitious Japanese person would usually avoid having this as a jersey number.

Mael - #5

Mael's jersey number as well as most things about him are meant to be ironic in some way/bully him.

In Japanese numerology, it's considered a lucky number. It's also associated with the Chinese concept of the "five elements"/Wuxing, so it is said sometimes that number 5 brings luck and blessings, which Mael lacks from birth.

The deficient destructive cycle in Wuxing is the fifth phase "counteracting" (fire evaporates water, water destabilizes earth, etc) -> Mael has a reactive and explosive personality that is harmful to him and others lying within his trigger prone behavior.

In Christian numerology, number 5 symbolizes grace and God's unwavering love towards humankind, which is again ironic because Mael is born in an unfavorable situation and struggles to move on.

God's fifth commandment is "Honor your mother and your father" -> Mael was born into an abusive household to drug addicts who neglected him and later on disowned him. Since birth they gave him nothing and were nobodies to him. Number 5 symbolizes God's favor culturally, but Mael was not born in his favor, and afterwards he fails to adjust to a normal and stable self and living.

In Buddhism there are also five precepts that serve as the base morality principle for enlightenment and the path so salvation.

The five precepts forbid the following: killing of both animals and humans, theft and other things along those lines (fraud, forgery), sexual misconduct (i.e. sexual acts which are either forceful, unethical or adulterous in nature), spoken falsehood (lying, gossiping, verbal aggression), intoxication (alcohol, drugs, occasionally smoking is counted).

Out of those Mael is guilty - and often! - of theft, verbal aggression/malicious speech, intoxication (both as someone who uses stimulants and drinks frequently and even sold substances in the past).

TL;DR MAEL IS NOT MAKING IT TO NIRVANA WITH THIS ONE 😂😂😂 HE IS STUCK IN THE CYCLE 😂😂😂😂

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

🧿🔮 An Outline of Contemporary Psychic Abilities- A-Z

⭐️ Aeromancy: Interpreting the shapes of clouds

⭐️ Afterlife Communication: Connecting with those who are deceased

⭐️ Alomancy: Reading the patterns of salt cast into the air after it falls to the floor

⭐️ Apantomancy: Interpreting meaning in chance meeting with animals

⭐️ Astral Projection: Out-of-body travel; other related terms are lucid dreaming, soul journeying, and remote viewing

⭐️ Aura Reading: Intuitively perceiving the hey is occurring in the auric field

⭐️ Automatic Writing: Writing a message from an outside intelligence through the subconscious mind

⭐️ Bibliomancy: Interpreting a passage chosen at random from a book

⭐️ Catoptromancy: Telling fortunes with the help of a mirror

⭐️ Channeling: Delivering a message from a separate intelligence that enters the practitioner’s body

⭐️ Chirmancy: Palmistry; divination done by interpreting the lines on someone’s hands

⭐️ Clairalience: Ability to smell what’s not present

⭐️ Clairaudience: The ability to psychically hear events

⭐️ Claircognizant: The sense of clear knowing

⭐️ Clairempathy: The ability to sense others’ emotions

⭐️ Clairgustance: The ability to psychically taste what isn’t physically present

⭐️ Clairsentience: Ability to sense others’ feelings or senses

⭐️ Clairtangecy/Clairsensitivity: The ability to read energy through touch or from objects in your presence

⭐️ Clairvoyance: The ability to psychically see nonphysical realties

⭐️ Cleromancy: Casting stones, bones, or dice to perform divination

⭐️ Crystallomancy: Seeing the future in a crystal ball

⭐️ Déjà vu: Sensing that a current event has already occurred

⭐️ Demonomancy: Summoning demons to answer questions

⭐️ Divination: Use of psychic gifts to obtain answers

⭐️ Dowsing (Radiesthesia): Using an instrument to detect water, metals, missing people, and other things in the ground

⭐️ Dream Interpretation: Interpreting the meaning of dreams

⭐️ Empathy: Ability to sense others’ feelings, illnesses, sensations, knowledge, and more

⭐️ Exorcism: Release of negative entities.

⭐️ Feng Shui (Geomancy): Shifting the environment to bring about desired effects

⭐️ Gyromancy: Divination performed by making a circle’s perimeters with letters of the alphabet; ouija boards employ a similar concept

⭐️ Healing: Creating more wholeness within the other; includes faith, healing, the laying on of hands, and more

⭐️ Horoscopy: Interpretation of astrological horoscopes

⭐️ Hydromancy: Divining by observing changes in water

⭐️ Hypnosis: Creation of a trance state in another to evoke answers or healing

⭐️ I Ching: An ancient Chinese system of divination

⭐️ Intuition: A catchall word for managed use of psychic abilities

⭐️ Levitation: Flotation of objects or the body above the ground

⭐️ Libanomancy: Interpreting shapes in smoke

⭐️ Mediumship: Serving as a conduit for otherworldly beings

⭐️ Megagnomy: Use of psychic ability while in a hypnotic state

⭐️ Oculomancy: Divination by observing another’s eyes

⭐️ Past-Life Regression: Use of a meditative state to remember a previous life

⭐️ Precognition: Ability to foretell the future

⭐️ Prophecy: Knowledge of divine will

⭐️ Psychometry: Gaining knowledge through touch of objects

⭐️ Pyrokensis: Sparking fire with the mind

⭐️ Scrying: Using an object to see psychically

⭐️ Tarot Reading: Use of tarot cards or archetypes to prophesize

⭐️ Tasseography: Cup divination; interpreting tea leaves or coffee grains

⭐️ Telekinesis: Ability to move objects without touching them

⭐️ Telepathy: Hearing mind-to-mind information

⭐️ Transfiguration: Superimposition of a face on a medium

⭐️ Voodoo: Practices from the Voodoo religion, such as the use of rituals to ask spirits for advice, protection, or help, and contact with spirits through their possession of a medium

⭐️ Xenoglossy: Speaking in a language that is not one’s own

~ Source ~

-Cyndi Dale (Llewellyn's Complete Book of Chakras: Your Definitive Source of Energy Center Knowledge for Health, Happiness, and Spiritual Evolution)

#spirituality#psychic abilities#divination#esoteric#mysticism#mystical#spiritual journey#spiritual healing#witchcraft#witchblr#writerblr#shadow work#book qoute#esoteric knowledge#third eye#kundalini#spiritual awakening#higher self

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legends of the humanoids

Reptilian humanoids (5)

Wuxing – the connections between the Five Dragon Kings (Ref) and the Five Elements philosophy

To better understand the origins of the Five Dragon Kings and the ancient Chinese legend, it is worth mentioning the wuxing of natural philosophy, which states that all things are composed of five elements: fire, water, wood, metal and earth.

The underlying idea is that the five elements 'influence each other, and that through their birth and death, heaven and earth change and circulate'.

The five elements are described as followed:

Wood/Spring: a period of growth, which generates abundant vitality, movement and wind.

Fire/Summer: a period of swelling, flowering, expanding with heat.

Earth is associated with ripening of grains in the yellow fields of late summer.

Metal/Autumn: a period of harvesting, collecting and dryness.

Water/Winter: a period of retreat, stillness, contracting and coolness.

The wuxing system, in use since the Han dynasty (2nd century BCE), appears in many seemingly disparate fields of early Chinese thought, including music, feng shui, alchemy, astrology, martial arts, military strategy, I Ching divination, and traditional medicine, serving as a metaphysics based on cosmic analogy.

The wuxing originally referred to the five major planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, Mars and Venus), which were thought of as the five forces that create life on earth. Wu Xing litterally means moving star and describes the five types of Qi (all the vital substances) cycles through various stages of transformation. As yin and yang continuously adjust to one another and transform into one another in a never-ending dance of harmony, they tend to do so in a predictable pattern.

The lists of correlations for the five elements are diverse, but there are two cycles explaining the major interaction. The yin-yang interaction, which by increasing or decreasing the qualities and functions associated with a particular phase, it may either nourish a phase that is in deficiency or drain a phase that is in excess or restrain a phase that is exerting too much influence (see below):

The Creation Cycle (Yang)

Wood feeds Fire

Fire creates Earth (ash)

Earth bears Metal

Metal collects Water

Water nourishes Wood

The Destruction Cycle (Yin)

Wood parts Earth

Earth dams (or absorbs) Water

Water extinguishes Fire

Fire melts Metal

Metal chops Wood

The Huainanzi (2nd BCE) describes the five colored dragons (azure/green, red, white, black, yellow) and their associations (Chapter 4: Terrestrial Forms), as well as the placement of sacred beasts in the five directions (the Four Symbols beasts, dragon, tiger, bird, tortoise in the four cardinal directions and the yellow dragon.

伝説のヒューマノイドたち

ヒト型爬虫類 (5)

五方龍王(参照)と五行思想の関連性

ここで、五方龍王の起源、そして古代中国の伝説をよく理解するために、万物は火・水・木・金・土の5種類の元素からなる、という自然哲学の五行思想について触れておきましょう。 5種類の元素は「互いに影響を与え合い、その生滅盛衰によって天地万物が変化し、循環する」という考えが根底に存在する。

五行は次のように説明されている:

木は、春の豊かな生命力、動き、風を生み出す成長期。

火は、夏の太陽の暖かさの下で行われる成熟の過程、熱で膨張する時期。

土は、晩夏の黄色い野原での穀物の成熟に関連している。

金は、秋の収穫、収集、乾燥の時期。

水は、冬の雪に覆われた暗い大地の中に潜む新しい生命の可能性と静寂の時期。 漢の時代 (紀元前2世紀頃) から使用されてきた五行説は、音楽、風水、錬金術、占星術、武術、軍事戦略、易経、伝統医学など、中国初期の思想の一見バラバラに見える多くの分野に登場し、宇宙の類推に基づく形而上学として機能している。

五行とは文字通り「動く星」を意味し、五種類の気(生命維持に必要なすべての物質)が様々な変容の段階を経て循環することを表している。陰と陽は絶え間なく互いに調整し合い、調和の終わりのないダンスで互いに変化していくため、予測可能なパターンで変化する傾向がある。

五行の相関関係は多様だが、主要な相互作用を説明する2つのサイクルがある。陰陽の相互作用は、特定の相に関連する資質や機能を増減させることで、不足している相に栄養を与えたり、過剰な相を排出したり、影響力を及ぼしすぎている相を抑制したりする (以下参照):

相生(陽)のサイクル

木は燃えて火を生む

火が土 (灰) をつくる

土は金属を産出する

金属は表面に水���集める

水は木を育てる

相克(陰)のサイクル

木は大地を構成する

土は水を堰き止める

水は火を消す

火は金属を溶かす

金属が木を切る

『淮南子』(紀元前2世紀)には、五色の龍(紺碧・緑、赤、白、黒、黄)とその関連性 (第4章: 地の形)、五方位への聖獣の配置(四枢の四象徴獣、龍、虎、鳥、亀、黄龍)が記述されている。

#wuxing#5 dragon kings#5 elements#taoism#yin yang#humanoids#legendary creatures#hybrids#hybrid beasts#cryptids#therianthropy#legend#mythology#folklore#dragon#nature#art

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yelling about this again since it's a big pet peeve of mine but please be aware!!! that "kill the wolf" is not!! a valid translation of Sha Po Lang!! it's not even a "literal translation" it's just MTL gibberish trying to make sense of a term with no English translation

pasting the explanation I gave on twt below the cut-

杀破狼/sha po lang corresponds to three different stars 七杀/qi sha ('seven killings'), 破军/po jun ('vanquisher of armies'), and 贪狼/tan lang ('greedy wolf'), which are significant in a system of Chinese astrology called 紫微斗数/zi wei dou shu

when these three stars appear in certain positions in a natal star chart, they compose the 'sha po lang' star formation, which foretells change and revolution, a turbulent fate which could lead to one making a name for oneself in chaotic times, or ending up destitute

famous generals are often born under this star formation as well - as you can see, there are a lot of ties with the themes of the novel itself

but, however, it doesn't really have a proper english translation, hence why i'm in favor of the 'stars of chaos' version of the title

if you want to look at the actual stars (look closer at the vol 1 cover for a little easter egg!)

qi sha = polis/mu sagittarii

po jun = alkaid/eta ursae majoris

tan lang = dubhe/alpha ursae majoris

thank you minirant complete

#sha po lang#spl#shapolang#stars of chaos#priest#danmei#7s is using stars of chaos for a reason yall

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

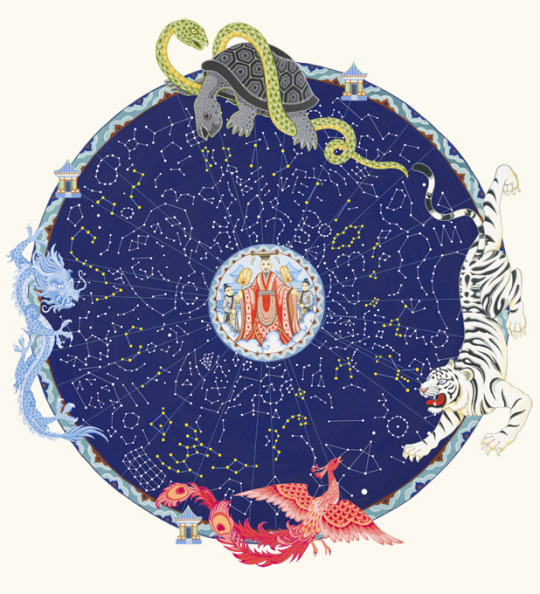

The Four Symbols

"According to the archaeological evidence, the concept of the Four Symbols may have existed as early as China’s Neolithic period (some 6,000 years ago). This is based on some clam shells and bones forming the images of the Azure Dragon and the White Tiger that were found in a tomb in Henan." "I Ching (易經), a Chinese divination text also known as the Book of Changes, traces the roots of the Four Symbols back to the beginnings of the world. It alleges that they were bred from the famous ring of yin-yang (陰陽), which instils order upon the chaotic spirit of Taiji (太極)."

Four Guardians, Four Gods, Four Auspicious Beast

Each corresponds to a quadrant in the sky, with each quadrant containing seven seishuku, or star constellations (also called the 28 lunar mansions or lodges; for charts, see this outside site). Each of the four groups of seven is associated with one of the four celestial creatures. There was a fifth direction -- the center, representing China itself -- which carried its own seishuku.

The four Symbols hold significant symbolic meaning in cosmology and culture. They represent harmony and balance od the universe. The represent the harmony and balance of the universe. Each symbol governing a specific direct , season and set of elements. The symbols are associated with the five elements theory, which is crucial in traditional medicine , Feng Shui, and astrology. The also represent the cyclical nature of time, as they are closely tied to the Chines zodiac and the twelve Earthy branches.

The Four symbols paly a significant role in Shines astrology particularly in the Chinese zodiac, each symbol is associated with the specific year within the 12-year zodiac cycle, along with the five elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, and water) The combination of the symbol and the element determines the characteristics and destiny of individuals born in the particular year. The four symbol also influence their astrological systems, such as the Eight Characters (BaZi) and the Four Pillars of Destiny.

I thought I compare the LMK versions of them to the real mythology.

Vermilion Bird: Symbol of the South

Vermilion Bird aka Phoenix or Zhuniao, is the symbol of the southern direction. It is associated with the season of summer and represents the element of fire. It is the symbol of rebirth, immortality, and prosperity. It is also often associated with love, beauty, and passion.

Color- Red

Time of Day - Midady

Appearance: said to have chicken’s head, swallow’s chin, snake’s neck, fish’s tail, and five-color feather. ;or A mythical bird with colorful plumage and radiant feathers.

Its seven mansions are the Well, Ghosts, Willow, Star, Extended Net, Wings and Chario

Black Tortoise: The Symbol of the North

The Black Tortoise aka Black Warrior, Xuanwu is the symbol of the northern direction. Associated with the season of winter and element of water. Believed to bring protection and longevity. It is also associated with knowledge and wisdom and the control of water.

Color- Black

Time of Day- Midnight

Appearance: A giant tortoise with a snake wrapped around its back

Its seven mansions are the Dipper, Ox, Girl, Emptiness, Rooftop, Encampment and Wall.

Azure Dragon: Symbol of the East

Azure Dragon aka Blue Dragon or Qinglong, representing the easter direction. The ruler of the sky and is associated with the season of spring, the element of wood and is believed to being harmony and good fortune to those who embrace its energy.

Color: Blue- green

Time of Day - Dawn

Looks – serpent like body, deer-like antlers, fish-like scales and eagle-like claws.

The Azure Dragon as it is said that when the seven mansions in that area (Horn, Neck, Root, Room, Heart, Tail, and Winnowing Basket) are joined up, they form the shape of a dragon

White Tiger: The Symbol of the West

White tiger aka Baihu, is the guardian of the western direction. Associated with the season of autumn and the element of metal. Believed to represent strength, courage, and protection. Its is also associated with the celestial guardian of the west a powerful deity known as Xuanwu

Color- White

Time of Day- Dusk

Appearance: a creature with a tiger's body and lions' mane.

the White Tiger, and its seven mansions are the Legs, Bond, Stomach, Hairy Head, Net, Turtle Beak and Three Stars.

it was held to be the God of War. In this capacity, the White Tiger was seen as a protector and defender, not just from mortal enemies, but also from evil spirits.

A symbol of force and army, and so many things entitled White Tiger in ancient China are related to military affairs. For instance, the white tiger banner in the ancient army and the white tiger image on the Commander’s Tally. In the Han Dynasty, the White Tiger was usually carved on the stone relief of a tomb door, or on the lintel of a tomb passage with the Azure Dragon, to ward off evil spirits.

This puts a lot together and I'm impressed with the details that the show animators and designers put into their character designs.

Also..

Yellow Dragon: Symbol of Central

Yellow Dragon aka Qilin the symbol if the Central direction, and is associated with the season Midsummer and the element earth.

Color: Yellow

--

Comparing them they share the colors with the stones and the yellow dragon (central) seems to correspond with the jade emperor's yellow stone. Once again love the show details.

Nearly forgot about this and left it in the drafts wanted to post this then completely forget them.

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I read your posts about Su Daji, and I believe one of them were about her being the literal incarnate of the Moon Fox of the 28 mansions.

I was wondering if there's any lore surrounding the 28 mansions, and if there are any incarnates of them other than her

I more specifically wanted to know about the Moonbird of Net, but I wouldn't mind learning about the others!

Well, tiny correction: Su Daji is not the incarnate of the Heart Moon Fox, but Wu Zetian, China's one and only female emperor, is said Lunar Mansion incarnate in Flowers in the Mirror, a Qing dynasty novel.

In another Qing dynasty novel, Shuoyue Quanzhuan (说岳全传), the notoriously corrupt historical figure, Qin Hui's wife, was the Maiden Earth Bat (女土蝠) incarnate: having been killed by the Golden-winged Peng for farting during Buddha's lecture, she would take revenge on his reincarnation, the heroic general Yue Fei.

About the 28 Lunar Mansions themselves: originally, they are kinda like the Chinese equivalent of the 12 zodiac in western astronomy.

Like, think of the sky as a belt, divided into 4 quadrants, each quadrant containing a giant constellation that represents the Divine Beasts of the Four Directions: Azure Dragon(E), White Tiger(W), Vermillion Bird(S), Black Turtle(N).

Each of these giant constellations can then be broken down into 7 smaller stars/star clusters, corresponding to a section of the sky. They are used to mark the position of the moon during a given month, as well as determine the seasons via the sun's location in a given mansion.

Azure Dragon: 角(Jiao)、亢(Kang)、氐(Di)、房(Fang)、心(Xin)、尾(Wei)、箕(Ji)

White Tiger: 奎(Kui)、娄(Lou)、胃(Wei)、昴(Mao)、毕(Bi)、觜(Zi)、参(Shen)

Vermillion Bird: 斗(Dou)、牛(Niu)、女(Nv)、虚(Xu)、危(Wei)、室(Shi)、壁(Bi)

Black Turtle: 井(Jing)、鬼(Gui)、柳(Liu)、星(Xing)、张(Zhang)、翼(Yi)、轸(Zhen)

However, like many things astronomy, they were later appropriated by astrology and used in divinations, by assigning an element/phase and an animal to each of these stars, making them into the "Beast Stars" (禽星) who can faciliate or obstruct each other, with different implications on your best course of action that day.

Now, look back at the list above. Each vertical column is assigned an element, in this order: Wood, Metal, Earth, Sun, Moon, Fire, Water.

So Star Lord Mao of the White Tiger Quadrant would be the "Sun Rooster Star", Star Lord Xin of the Azure Dragon Quadrant would be the "Moon Fox Star", etc.

But wait, there is more! Outside of the Beast Star divination system, traditional Chinese astrology also viewed the starry sky as the Heavenly Emperor's palace, with each constellation representing an area/building/resident of said palace.

Following that line of thought, people in the Tang dynasty came up with a catchy poetic star catalogue, 步天歌("Song of the Sky Pacers"), in which the 28 Lunar Mansions are kinda like managers who watch over their own group of stellar officials.

And the big 4 quadrants they are part of? Well, they are like four departments, each with their own general themes.

These themes aren't absolute; for example, the Azure Dragon Quadrant represents the front gate all the way up to the main palace halls, so they have a lot of stellar officials in charge of chariots, gates and honor guards, but also...grain baskets.

As for the Moonbird of Net, a.k.a. Bi Yuewu the Moon Crow Star: well, ain't this the damnest coincidence, I actually had an old OC concept based on this very Lunar Mansion!

Bi the Moon Crow

In traditional Chinese astrology, the Bi star was the god of rain, the "Master Rain"(雨师) to the "Duke Wind"(风伯) of Ji star: it was believed that whenever the moon came near this star, there would be a huge storm.

Since the Grand Compendium of the Three Religions' Deities stated that "Master Rain" was actually a one-legged divine bird called Shang Yang, who first appeared in 孔子家语 as this little creature who'd dance before every downpour like a goofy weather forecast guy, I drew his Stellar Beast form as a one-legged crow.

(OC-specific stuff below, not mythos canon)

He is very skilled at creating cloud formations, to the point where he got "borrowed" by the Wind and Thunder Bureau more than some of the Water-aligned Lunar Mansions.

After the Havoc, he has also become the new guy in charge of the Peach Garden(one of the constellations falling under Bi's section of the sky is Tianyuan, the Celestial Garden).

Anyways, traditional Chinese astrology is super fascinating, and I've only gone into a tiny fraction of it here. Hope it helps, though!

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are various types of Astrology. In the West, a very common type of Astrology that people study is Western Astrology. This is one type of system to look at the zodiac and the stars to understand someone's psychological make-up, personality and emotional state. This system is based on looking at the zodiac from a tropical lens. In simple terms, this is based on the position of the sun from the earth.

Sidereal Astrology is based on the earth's position in relation to constellations. Another very important aspect of Astrology is the Lunar Calendar. The moon has a 27-28 day cycle that mirrors the woman's menstrual cycle (not a coincidence) so understanding the 27 Lunar Mansions as they move through the phases each day, and which Lunar Mansion the moon was in at birth, can explain a telling aspect of one's mental state and personal outlook. The Lunar Mansions have stories behind them. Some people will refer to these stories as myths. The hidden knowledge and wisdom is often played out in a similar story for the native's life. This is also a technique to understand someone's underlying motivations and soul desires beneath a zodiac sign.

Chinese Astrology uses the Lunar Calendar and Vedic Astrology uses the Lunar Phases, Lunar Mansions and sideral alignments at birth to reveal the placements within one's life map. Some might say Western Astrology is about telling people what they already know about themselves, while Vedic Astrology is more of a prediction system that advises people about their potential, spiritual path and areas of focus for this birth. Both offer similar benefits and can help people arrive at the same conclusion. There are many other types of systems for Astrology. Over time, various cultures and spiritual traditions have come up with different ways of reading the planetary energies and the stars.

Many claim that Astrology is not always accurate and that it is not a real science. This is often a claim that is made without intense and in-depth study into any of the systems. In addition, when we are looking at the occult (be it tarot, various systems of Astrology, Numerology, etc.) it will most often come to life more when we use our intuition. Simply trying to rely on intellect and formulas will not aid you in understanding. People with a deep reverence for the divine intelligence as well as a humble attitude when it comes to human limitation, are often granted even deeper access to secret knowledge and wisdom.

We will share different astrological insights from a variety of traditions. Our readers come from a range of knowledge and systems on the topic. Truth can be revealed no matter which system you prefer.

Namaste...