#Catherine Merridale

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

6thofapril1917's Eastern Front Reading List

So, you're an HBO War fan who wants to learn more about the Eastern Front. Maybe you, like me, wanted to know why Masters of the Air's depiction of the Nazis was so much darker than in Band of Brothers. Below is a list of books on the topic that I've been assigned during my time studying Eastern European and Soviet History. Most of these are scholarly monographs, not pop history, but I found them gripping regardless. I've provided Internet Archive links when available, and links to booksellers when not. If anyone else has suggestions, feel free to add them in reblogs - I focus primarily on Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine.

The Eastern Front, 1941-1945, German Troops and the Barbarisation of Warfare; 2nd edition by Omer Bartov (Palgrave Macmillan, 2001). Available on Internet Archive.

Originally published in 1985. The first book in English to comprehensively challenge the Clean Wehrmacht myth. Examines the experiences, indoctrination, and crimes of Wehrmacht soldiers.

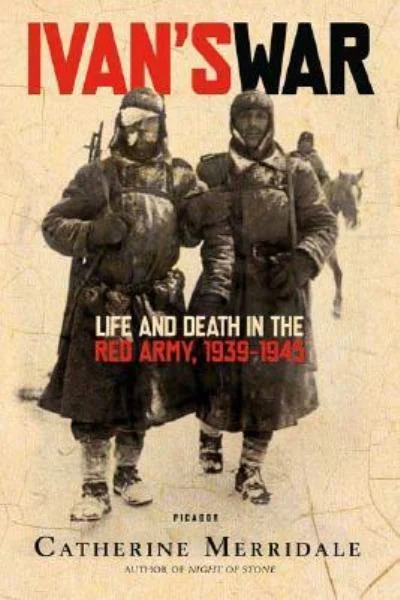

Ivan's War: Life and Death in the Red Army, 1939-1945 by Catherine Merridale (Picador, 2007).

Looks into the day-to-day life and experiences of soldiers in the Red Army. Probably the most accessible of the books on this list in terms of writing style.

A Writer at War: A Soviet Journalist with the Red Army, 1941-1945 by Vasily Grossman, trans. Anthony Beevor and Luba Vinogradova (Pantheon, 2007).

A collection of primary sources and writings from Soviet journalist Vasily Grossman, who was embedded with the Red Army.

Russia at War, 1941-1945: A History by Alexander Werth (Barrie & Rockliff, 1964).

Similar to Grossman, Werth was a British journalist for the BBC and the Sunday Times during the war. Details his experiences while embedded with the Red Army.

The Unwomanly Face of War by Svetlana Alexievich, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volkhonsky (Random House, 2017).

Originally published in the USSR in 1983. Nobel Prize winner Alexievich's Groundbreaking oral history of women who served in the Red Army during the Great Patriotic War. One of my personal favorites.

Last Witnesses: an Oral History of the Children of World War II by Svetlana Alexievich, trans. Pevear and Volkhonsky (Random House, 2019).

Originally published in the USSR in 1985. Covers the experiences of Soviet children on the Eastern Front, soldier, partisan, and civilian alike.

Marching into Darkness: The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust in Belarus by Waitman Wade Beorn (Harvard University Press, 2014).

Examines the Wehrmacht and its crucial role in carrying out the Holocaust in Belarus.

Fortress Dark and Stern: The Soviet Home Front during World War II by Wendy Z. Goldman and Donald Filtzer (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Comprehensive overview of the Soviet home front over the course of the war, including the mass evacuations of people and industry into Siberia and Central Asia. An absolutely fascinating read.

The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture by Ronald Smelser and Edward J. Davies II (Cambridge University Press, 2008). Available on Internet Archive.

Analyzes the creation of the Clean Wehrmacht myth by German war veterans, the myth's popularization in American culture, and its impact on Americans' understanding of the Eastern Front. Spoiler: Band of Brothers does not come out of this unscathed.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I read in 2022

A little late. 2023 to follow soon.

* * *

Ying Shih Yü, Chinese History and Culture, Volume 1

Yuen Yuen Ang, China’s Gilded Age

Lucia Berlin, A Manual for Cleaning Women

Stephan Körner, Kant

Alexander Herzen, My Past and Thoughts, Vol 5

Leonard Susskind & George Hrabovsky, Classical Mechanics: The Theoretical Minimum

Frank Dikotter, Mao’s Great Famine

Alexander Herzen, My Past and Thoughts, Vol 6

George Orwell, 動物農莊(港豬版)

Tom Hopkins, Sales Prospecting for Dummies

Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

Paul Gilroy, There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack

Kenn Amdahl, There Are No Electrons

Gianfranco Poggi, The Development of the Modern State

Ehrhard Bahr & Ruth Goldschmidt Kunzer, Georg Lukacs

Gianfranco Poggi, Forms of Power

Thomas Gordon, Parental Effectiveness Training

Robert Heinlein, Starship Troopers

James Fok, Financial Cold War

Angela Carter, The New Eve

Elizabeth Strout, My Name is Lucy Barton

Ying Shih Yü, Chinese History and Culture, Volume 2

Bill Hayton, The Invention of China

Murasaki Shikibu, The Tale of Genji

Hannah Arendt, The Life of the Mind

林匡正, 香港足球史

Karl Ulrich & Lele Sang, Winning in China

Harry Morgan, Sunny Places for Shady People

Elizabeth Strout, Amy and Isabelle

Naomi Standen (ed), Demystifying China

Angela Carter, Wise Children

Elizabeth Strout, The Burgess Boys

John Gribbin, Get a Grip on Physics

Chris Waring, An Equation for Every Occasion

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition

Mary McCarthy, Birds of America

Mary McCarthy, The Company She Keeps

Lisa Taddeo, Three Women

Hon Lai-chiu, The Kite Family

Jim Breithaupt, Physics

John Gribbin, Seven Pillars of Science

John Gribbin, Six Impossible Things

Barry Lopez, Horizon

Elizabeth Strout, Olive Kittridge

Elizabeth Strout, Anything is Possible

Elizabeth Strout, Oh William!

Mike Goldsmith, Waves

Monica Ali, Untold Story

Catherine Merridale, Ivan’s War

Jessica Andrews, Saltwater

Val Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature

AM Homes, May We Be Forgiven

Gaia Vince, Adventures in the Anthropocene

Ho-fung Hung, City on the Edge

Richard Feynman, QED

Fredric Raichlen, Waves

Angela Carter, The Magic Toyshop

Karen Cheung, The Impossible City

Adam Tooze, The Deluge

Celeste Ng, Everything I Never Told You

Sean Carroll, The Biggest Ideas in the Universe

Louisa Lim, The Indelible City

Gavin Pretor-Pinney, The Wave Watcher’s Companion

Adam Tooze, The Wages of Destruction

Adam Tooze, Shutdown

Annie Ernaux, A Frozen Woman

Ursula Le Guin, The Lathe of Heaven

Virgina Woolf, The Waves

Ursula Le Guin, Tehanu

Ursula Le Guin, The Telling

Gaia Vince, Nomad Century

Janna Levin, How the Universe Got Its Spots

Lara Alcock, Mathematics Rebooted

Donella Meadows, Thinking in Systems

Emily St John Mandel, The Glass Hotel

Anon, 伊索傳 & 驢仔

Elizabeth Kolbert, Under a White Sky

Emily St John Mandel, Station Eleven

Gary Gerstle, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order

Bruno Mansoulié, All Of Physics (Almost) In 15 Equations

1 note

·

View note

Text

2024 books read

Jan

The Wind Done Gone - Alice Randall

If This is a Man/The Truce - Primo Levi

Flesh and the Word: An Anthology of Erotic Writing - ed. John Preston

Wintergirls - Laurie Halse Anderson

Feb

Hello Cruel World: 101 Alternatives to Suicide for Teens, Freaks, and Other Outlaws - Kate Bornstein

The Hunger Artist - Franz Kafka

Mar

Living a Feminist Life - Sara Ahmed

Lenin on the Train - Catherine Merridale

Flesh and the Word 2 - ed. John Preston

Apr

Call for the Dead - John Le Carré

Trust The Plan: The rise of QAnon and the conspiracy that unhinged America - Will Somer

The Tragedy of Heterosexuality - Jane Ward

A Murder of Quality - John Le Carré

May

The Spy Who Came In From The Cold - John Le Carré

Jun

Dungeon Meshi - Ryōko Kui

Fear and Loathing in La Liga: Barcelona, Real Madrid, and the world's greatest sporting rivalry - Sid Lowe

Christie Malry's Own Double-Entry - B S Johnson

Jul

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy - John Le Carré

Aug

Blindsight - Peter Watts

Sep

Echopraxia - Peter Watts

Monarchs of the Sea: The extraordinary 500 million year history of cephalopods - Danna Staaf

0 notes

Text

In Soviet films, on Soviet posters, in Soviet poetry and songs, the typical Red Army soldier was hale and hearty, simple and straightforward, untroubled by trauma or fear. He cheerfully marched all day, slept on the ground at night, never complained, and never even used swear words. When the British historian Catherine Merridale was collecting the lyrics of Red Army songs for her 2005 book, Ivan’s War, she ran into a wall: Even decades later, ethnographers and veterans could not or would not share with her any satirical, obscene, or subversive lyrics, because no one dared to repeat “disrespectful versions” of the sainted soldiers’ songs.

In the official accounts, the Red Army soldier did not brutalize civilians, rape women, or loot property either. Famously, a staged photograph of soldiers waving a Soviet flag on top of the Reichstag in May of 1945 had to be doctored, because one of them was wearing two wristwatches (they were stolen from Germans; Soviet soldiers typically did not own several wristwatches). Many years later, when another British historian, Antony Beevor, published archival evidence of looting—children as young as 12 traveled to Berlin for that purpose—and the mass rape of 2 million German women, the Russian ambassador to the U.K. accused him of “lies, slander, and blasphemy.”

— World War II Is All That Putin Has Left

#anne applebaum#world war ii is all that putin has left#history#military history#propaganda#photography#misogyny#rape#war crimes#ww2#battle of berlin#ussr#russia#catherine merridale#antony beevor

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Literackie Biuro Podróży [sezon 3 odc.6]

Literackie Biuro Podróży [sezon 3 odc.6]

ROSJA SOWIECKA W audycji: Thierry Wolton „Historia komunizmu na świecie. Tom 1: Kaci” Wydawnictwo Literackie Leonid Józefowicz „Zimowa droga. Powieść dokumentalna” Wydawnictwo Noir-sur-Blanc Yuri Slezkine “Dom władzy” PIW PRZERYWNIK MUZYCZNY: Ilugdin Trio „Tamed loneliness” z albumu “My Story” Jazzists Catherine Merridale, „Wojna Iwana. Armia Czerwona 1939-1945” Wydawnictwo Znak Mark…

View On WordPress

#Borys Sokołow#Catherine Merridale#Dom Wydawniczy Rebis#Ilugdin Trio#Jazzists#Leonid Józefowicz#Literackie Biuro Podróży#Mark Sołonin#Novae Res#Oficyna Wydawnicza Noir sur Blanc#PIW#Talgat Jaissanbayev#Thierry Wolton#Wydawnictwo Literackie#Wydawnictwo Znak#Yuri Slezkine

0 notes

Quote

Se Lenin non avesse conquistato il proprio partito, e se non si fosse guadagnato un seguito anche al di fuori di esso nei due mesi successivi, forse le "Tesi di Aprile" sarebbero state dimenticate nell'angolo polveroso di un archivio. Uno dei motivi del suo trionfo fu la forza delle sue convinzioni. Mentre altri discutevano e negoziavano sottili concessioni, procedendo sulla strada della rivoluzione come se cercassero di schivare delle mine, Lenin sapeva dove voleva arrivare e sapeva precisamente perché. La sua energia era prodigiosa, ed era infaticabile nello scrivere e nel dibattere, ripetendo le stesse tesi finché i suoi avversari non si stancavano di escogitare nuovi modi per confutarle. "Lenin diede prova di una forza così straordinaria", scrisse Suchanov, "di un tale, sovrumano impeto, che la sua colossale influenza sui socialisti e i rivoluzionari era assicurata". Il Partito bolscevico era una sua creazione, e storicamente Lenin aveva sempre trionfato su qualsiasi antagonista interno. Per il resto, a volte erano le sue stesse idee a risultare convincenti, ma a garantirgli la lealtà dei seguaci, quando ogni altro metodo falliva, era soprattutto quel suo dinamismo energico.

Catherine Merridale, Lenin sul treno, Utet 2017.

#Catherine Merridale#Lenin#Storia#Comunismo#Urss#Storia sovietica#Utet#Storiografia#1917#Rivoluzione russa#Libri

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: ‘Lenin on the Train’

George Martin Fell Brown | Socialist Alternative | March 29th 2017 Lively prologue to events which changed the world When the February revolution broke out in Russia in 1917 and the Tsar was overthrown, Vladimir Lenin was living in exile in Switzerland. Given his implacable opposition to the imperialist World War One, it was always going to be a major feat for the Bolshevik leader to return to Russia across […]

→ READ MORE ←

Get your Latest News From The Leftist Front on LeftPress.tk → Support Us On Patreon! ←

#leftpress#news#resistance#politics#Centenary of the Russian Revolution#Culture#History#Alexander Helphand#Book Review#Books#Catherine Merridale#Georgi Plekhanov#Review#Russia#Russian Revolution#Vladimir Lenin#George Martin Fell Brown#Socialist Alternative#Book Review: ‘Lenin on the Train’

1 note

·

View note

Text

Catherine Eddowes timeline

1842 – Catherine is born at 20 Merridale Street, Graisley Green, Wolverhampton, West Midlands, to tinplate worker George Eddowes and his wife cook Catherine née Evans (April 14).

1848 – Catherine’s father George and uncle William leave their jobs in Wolverhampton, and with their families they walk to Berdmondsey, in the London borough of Southwark.

1855 – Catherine’s education at St John’s Charity School, Patters Field, Tooley Street, ends.

1855 – When Catherine is 13, her mother Catherine Evans Eddowes dies (October).

1857 – Her father George dies when she’s around 15, and she goes to live with an aunt.

Ca. 1860 – She eventually returns to finish her education at Dowgate Charity School and to care for her aunt in Biston Street, Wolverhampton, and to work as a tinplate stamper, a colour stover and a grainer at the Old Hall Works.

1860/61 – When about eighteen years old, Catherine moves to Birmingham, where she briefly lives with an uncle, shoe maker Thomas Eddowes. She works as a tray polisher for some months before returning to Wolverhampton, where she lives for a time with her grandfather also named Thomas Eddowes. Some months later, she moves to Birmingham again.

1862 – Catherine leaves home at 19 to live with ex-soldier Thomas Conway aka Thoas Quinn.

1862/63 – Catherine and Thomas earn a living around Birmingham and other West Midland towns by selling “Penny Dreadfull”s and Gallows Ballads penned by him.

1863 – Catherine Ann “Annie”, Catherine’s and Thomas’s first child is born atYarmouth Workhouse in Norfolk (April 18).

1865 – The family resides in Wolverhampton, and Thomas is also writing music hall ballads.

1867 – Catherine’s and Thomas’ second child, son Thomas Lawrence, is born (December 8).

1868 – Catherine and Thomas, and their children Annie and Thomas live in Westminster, London.

1871 – The family has settled at 1 Queen Street, Southwark, Catherine works as a laundress.

1873 – Their third child, George, is born at St George’s Workhouse, Mint Street, St Saviour’s (August 15).

1877 – Catherine’s and Thomas’ fourth and last child, Frederick William, is born at the Union Infirmary, Greenwich (February 21).

1877 – Catherine, aged 36 and working as a washerwoman, is convicted at Lambeth of ‘Drunk &c’. She receives a 14 day sentence which she serves in Wandsworth with her infant son Frederick (August 6).

1878 – Laundress Catherine is sentenced at Southwark to 7 days in Wandsworth Prison for being ‘drunk in a thoro'fare’ (August 17).

1881 – The family has moved to 71 Lower George Street, Chelsea, but it appears that their ‘marriage’ breaks up soon after. Thoas takes their sons with him, and Catherine and her daughter Annie go to Spitalfields to live near Catherine’s sister Eliza Gold.

Ca. 1881/82 – Catherine meets Irish jobbing market porter John Kelly. They eventually move in together at Cooney’s common lodging-house at 55 Flower and Dean Street, Spitalfields.

1886 – Catherine’s daughter Annie is bedridden and pays her mother to attend her. That is the last time Annie, aged 21, sees her mother (September).

1888 – Catherine and John go hop picking as every year to Hunton-near-Maidstone, in Kent with their friend Emily Birrell and her common-law husband, but as this season is not good,they come home earlier than expected and split their last sixpence between them; he takes fourpence to pay for a bed in the Cooney’s common lodging-house, and she takes twopence, just enough for her to stay a night at Mile End Casual Ward in the neighbouring parish (September 27).

1888 – Catherine goes at Cooney’s loding house and has breakfast in the kitchen with her common-law husband John Kelly (September 29).

1888 – Catherine is found lying drunk in the road on Aldgate High Street by PC Louis Robinson. She is taken into custody and then to Bishopsgate police station, where she is detained (September 29).

1888 – She is sober enough to leave at 1 a.m. on the morning (September 30).

1888 – Catherine’s mutilated body is found in the south-west corner of Mitre Square in the City of London, she was 46 (September 30).

Your life was difficult and cut short. You were free at last… 🌼

#Catherine Eddowes#Kate Conway#Kate Kelly#victim#victims#timeline#1842#1840s#1848#1850s#1855#1857#1860s#1860#Thomas Conway#1861#1862#Thomas Eddowes#1865#Thomas Quinn#1868#1867#1870s#1871#1873#1877#Wandsworth prison#1878#1880s#1881

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

How many notes before it’s fair to assume I’ve contributed to the sale of Catherine Merridale’s shitty Lenin book

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Night of Stone by Catherine Merridale

Night of Stone by Catherine Merridale is an extraordinary book, one of life and death and Russia, writes Doug (@bagatsen).

Night of Stoneis a book for deep and dark December, and an amazing work of history. Carrying the subtitle “Death and Memory in Russia,” it focuses on the twentieth century, when there was more than enough of the first, and the second existed under the particular pressures of the Bolshevik revolution and Soviet governance. Merridale started by looking at the rituals surrounding death as a way of…

View On WordPress

#Catherine Merridale#Communism#Doug#Fabulous Ones#History#Horror#Politics#Religion#Russia#What Is To Be Done

0 notes

Photo

National Unity Day Fiction Historical Fantasy Viktor Sigolayev, The Fatal Wheel: Crossing the Same River Twice (Alfa Kniga, 2012) No one understood how our contemporary, an officer in the reserves and a history teacher, ended up in his own past, back in the body of a seven-year-old boy, and back in the period of triumphant, …

#"popadantsy"#airbrushing history#Brezhnev era#Catherine Merridale#celebration#centenary#commemoration#developed socialism#historical fantasy fiction#KGB#Mikhail Zygar#October Revolution#real socialism#ressentiment#rewriting history#Russian National Unity Day#search for enemies#stagnation#Tikhon Shevkunov#Vladimir Lenin#Vladimir Putin

0 notes

Text

A fateful journey...

A fateful journey…

Lenin on the Train by Catherine Merridale After my recent prolonged bout of fiction, I really felt I needed a complete change in the form of something very, very factual – and fortunately I had just the thing standing by, in the form of a book I picked up on a recent jaunt to London. While there I popped into Bookmarks, the left-wing bookshop almost opposite the Bloomsbury Oxfam, and it felt…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Review of ‘Ivan’s War: Life and Death in the Red Army’

By Catherine Merridale

484 Pages

Published by Metropolitan Books

Released on April 1, 2007

4.5 out of 5 Stars

The number of books that existed that gave a picture of the Soviet Army during World War II was rather limited in the West during the Cold War. Much of what we understood about the Soviet Army and the Eastern Front came to us through the prism of the German experience, as men such as Erich Von Manstein, and Franz Hadler wrote a view of the war in the East that bore little resemblance to the reality (as much to whitewash the crimes of the Wehrmacht in the East as to “restore the reputation of the German soldier.”)

These works portrayed the Soviet Army as a faceless, remorseless horde in the vein of the Terminator. Recent scholarship, such as this book and Mr. Glantz’s works, have done much to reverse this view. Ms. Merridale has done a fine job in this “grunt’s eye” view of the Soviet Army in World War II, demonstrating her skill as a researcher and writer.

It has only been since the collapse of the Berlin Wall, and opening of the Soviet archives, and the availability of Soviet veterans to Western researchers that this balanced picture has emerged. Thirty million served in the Soviet Armed Forces during the entirety of the war, and Ms. Merridale has put a human face on this seeming mass of millions. These were ordinary folks, for the most part, caught between two totalitarian systems, who died in the millions to stop a cruel invader. But, as we shall see, the Soviet Union could mete out a large amount of cruelty of its own. Ms. Merridale has shown in a masterwork that the stereotypical “Ivan” of the Soviet Army never really existed. Soviet soldiers came from one of fifteen Soviet republics, and many of these young men knew little to no Russian, which was the dominant language of the military.

The book portrays a Soviet army that, in 1939, was large, crippled by Stalin’s purges, and amateurish in the extreme. Worse, living conditions were nothing short of disease-ridden and bestial, with corruption and outright theft common. A system of politruks -political officers, who were the eyes and ears of the party were everywhere, seeking out the slightest whiff of potential disloyalty. There were shortages of equipment, and when the Soviet army invaded Finland, it showed a large behemoth that was far competent or capable. It was this campaign that convinced Hitler that the Soviet state was on shaky ground and:

We have only to kick in the door, and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down (Hitler, June 1941)

However, the size of the disaster in Finland never reached the ears of the Soviet people, and their views were cynically fueled by clumsy state propaganda that convinced the Soviet people that if war came, they would bring glorious revolution to the world, all this came to a crashing end in June 1941. Merridale shows a state that was like Jekyll and Hyde. It was a seeming paradise to its citizens and a blood-soaked nightmare to its enemies - all carried out by the overzealous secret police apparatus working overtime to murder millions and crush any form of dissent. But this clumsy colossus had feet made of clay, and not every Soviet soldier was all that motivated to fight for communism before the invasion of June 1941, as this passage describes:

“…Two young deserters whose unit was also bound for the north were locked up when they were returned to base. ‘As soon as we get to the front,’ one of them said ‘I’ll kill the deputy Politruk.’ It may have been to spite the party that soldiers daubed swastikas on their barracks walls The fact that many politruks, whose education tended to be better than the average, were Jews, was probably a factor too.” (Merridale p.66)

Ms. Merridale then goes on to show the Soviet army on the brink of disaster as the Germans invade and confusion reigns. The Soviets were seemingly unable to stop the Germans no matter what they did until they were at the very gates of Moscow itself. But what comes through is a Soviet army that learned on the job and did a good job of digesting these lessons. It learned the lessons the Germans taught and then did a fine job of applying what they had learned. By 1943, with the Battle of Kursk, the student had indeed become the master.

The rest of the book goes into the feelings of Soviet troops in their march westward into what the contemporary Soviet press referred to as the “lair of the fascist beast.” The veterans Ms. Merridale speaks to aren’t shy about talking about witnessing individual Soviet soldiers and groups of Soviet soldiers take revenge on German civilians for the atrocities of the German military in the Soviet Union. Murder and especially rape were common, and Ms. Merridale manages to get more than a few sources to confirm it.

We get a look at Soviet women in the military and how they were really seen versus the wartime propaganda and how they earned their own place in the ranks. We see stories of loss, death, and life in the Soviet Army, all told masterfully. We hear stories unfiltered by Soviet officialdom and the lens of the Cold War.

The book also gets into what happened to the veterans when the war ended, and how their hopes for a better Soviet Union were dashed, most of them shunted aside by a cynical Soviet government (at one point, Stalin rounded up all the amputee beggars, many of them wounded at the front, and had them sent to Siberia), till Brezhnev mythologized the war that the Soviet veteran began to get his due. But even at the time of the book’s writing, most of them had not received any sort of pension or assistance now that they were in their old age.

How is This Book Useful to Wargamers?

While this book is a social history on the “softer” side of the Soviet army and dealing more with a conscript’s view of the war, it’s important to remember that this book is of value to the wargamer in that it tells a balanced view of the Soviet soldier. He wasn’t a remorseless Terminator who was indifferent to loss and bereft of any tactical skill. Nor was he the perpetually cheerfully brave fellow of Soviet propaganda. He was most likely a peasant, far from home, serving a state he didn’t particularly care for that would kill him if he demonstrated the slightest disloyalty. Many wargame rules are still caught in that “Hadler” trap of how they handle the Soviets. If this book does one thing, let it destroy those self-serving myths.

The tactical skill of the Soviets improved as the war went on, and it helped that the German skill declined as well. Like my review of Case Red, this book does a fine job of making ground beef out of the sacred cow and does so in a very readable style.

While there is some stuff that is not of interest to the wargamer, most of this book is good meat for any wargamer interested in the Eastern Front, and especially the Soviet soldier. Aside from it’s minor flaws, I would give this book 4.5 out of 5 stars. The book is available in hardback, softback, and Kindle from Amazon.

--

At Epoch Xperience, we specialize in creating compelling narratives and provide research to give your game the kind of details that engage your players and create a resonant world they want to spend time in. If you are interested in learning more about our gaming research services, you can browse Epoch Xperience’s service on our parent site, SJR Research.

--

(This article is credited to Jason Weiser. Jason is a long-time wargamer with published works in the Journal of the Society of Twentieth Century Wargamers; Miniature Wargames Magazine; and Wargames, Strategy, and Soldier.)

0 notes

Note

Any books on the history of Russia you would (highly) recommend?

All of these are Russian Revolution, pardon:

The Russian Revolution by Sean McMeekin

Lenin on the Train by Catherine Merridale

The Last of the Tsars: Nicholas II and the Russian Revolution by Robert Service

The Romanov Sisters: The Lost Lives of the Daughters of Nicholas and Alexandra by Helen Rappaport

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catherine Merridale, „Wojna Iwana. Armia Czerwona 1939-1945”

Catherine Merridale, „Wojna Iwana. Armia Czerwona 1939-1945”

Wydawnictwo Znak, 2020

Wydawnictwo Znak wznowiło, wydaną po raz pierwszy kilkanaście lat temu książkę Catherine Merridale poświęconą Armii Czerwonej czasów II wojny światowej. I choć wydawać by się mogło, że jedna z licznych przecież publikacji na ten temat nie może niczym czytelnika zaskoczyć, to książka brytyjskiej historyczki niewątpliwie wyróżnia się oryginalnym ujęciem tematu.

„Wojna…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Ottobre Russo

youtube

Ottobre. Il nome di un mese che diventa un simbolo di ribellione e di sovvertimento. Vai a sapere poi che in Russia utilizzano un altro calendario e quello che da noi è novembre, loro lo chiamano ottobre. Sempre in autunno siamo comunque, cadono le foglie ed esattamente cento anni fa cadeva anche l'ultimo impero che si proclamava discendente di Roma. La Grande Guerra che sta divorando l'Europa apre una crepa profonda nei secolari muri portanti dell'assolutismo zarista. Da lì un progressivo, inesorabile e disastroso crollo che in pochi mesi tavolge monarchia, governo liberale, esperimenti democratici, spinte riformiste e risvolti anarchici. Tutto viene spazzato via dalla ferrea determinazione di un uomo che nella primavera di quel fatidico 1917 ha rimesso piede sul suolo natio dopo un lungo periodo all'estero. E' Vladimir Il'ič Ul'janov, noto ai più con il nome di Lenin. Gli bastano davvero pochi mesi e la leadership di un gruppo coeso di militanti per rovesciare il rovesciabile ed instaurare quella che forse impropriamente viene definita “dittatura del proletariato”. Con i nostri libri vi riportiamo a quel periodo cruciale della storia del '900.

Seguiamo il futuro capo della rivoluzione, prima nell'insolita location descritta in Scacco allo Zar da Gennaro Sangiuliano. Il sole e il mare dell'isola di Capri fanno da sfondo al maturare di alcune idee chiave del bolscevismo. Tra un discorso incendiario ed un articolo sul suo giornale “La Scintilla”, il nostro trova il tempo per un amore che la storia ha quasi cancellato. Merito di Ritanna Armeni aver rievocato la figura delicata di Inessa Armand nel saggio Di questo amore non si deve sapere. Poi prendiamo posto nella carrozza “piombata” che lo trasporta da Zurigo a Pietrogrado per quel famoso “ritorno a casa destinato a cambiare il mondo intero”. Lenin sul treno di Catherine Merridale. Segnatevi questo titolo davvero particolare perché è in arrivo sui nostri scaffali.

Per il momento cruciale della rivolta facciamo una scelta che potrà anche far storcere il naso per la sua smaccata faziosità ma che dire... lui c'era ed era dannatamente bravo con la penna. John Reed giornalista e comunista americano è stato tra i pochi occidentali a capire nel '17 che la Storia stava per passare da Pietrogrado. Si precipita e segue passo passo gli sviluppi dell'Ottobre nei Dieci giorni che sconvolsero il mondo. Pochi titoli possono vantare tante imitazioni. Lasciatevi tranquillamente prendere anche dall'epica del film Reds diretto ed interpretato nel 1981 da uno straordinario Warren Beatty, tanto stiamo per riportarvi con i piedi per terra. Una narrazione critica, asciutta e al contempo godibilissima è quella contenuta nella prima parte della Storia dell'URSS dal 1917 a Eltsin di Mihail Heller e Aleksandr Nekric. Non fatevi spaventare dalle dimensioni importanti. Difficilmente vi fermerete alla prima parte. Grazie al meticoloso lavoro di scavo sulle fonti compiuto da Guido Carpi Russia 1917 è in grado di offrire uno spettro completo delle posizioni allora assunte dai più diversi attori in campo. Sorprendentemente tutta questa accuratezza si traduce in una scrittura scorrevole che incuriosisce e coinvolge. Interessante anche l'esperimento di Marcello Flores che in 1917, la rivoluzione si sforza di guardare a fatti così lontani nel tempo attraverso il filtro della nostra contemporaneità.

Un centenario importante che abbiamo voluto ricordare con questo percorso a tema storico. Ma non è il solo avvenimento fondamentale che spegne cento candeline. Un anno denso di eventi epocali che hanno cambiato il corso del secolo appena trascorso. Per una panoramica degli anniversari e tanti inediti riferimenti al presente non perdete 1917 L'anno della rivoluzione di Angelo d'Orsi.

до свидания!

1 note

·

View note