#Centenary of the Russian Revolution

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

5 Iconic Architectural Landmarks

Five Iconic Buildings and Their Significance

Throughout history, architectural landmarks have served as symbols of human ingenuity, cultural expression, and artistic achievement. These structures not only reflect the architectural styles of their times but also stand as enduring testaments to the creativity and ambition of their creators. Here, we explore five of the most iconic architectural landmarks in the world, each with its own unique significance.

1. Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, Spain

The Sagrada Familia is perhaps most renowned for its association with the legendary Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí. Gaudí’s visionary interpretation of Gothic architecture, combined with elements of Art Nouveau, makes the Sagrada Familia a truly unique masterpiece. Though construction began in 1882, the cathedral remains unfinished, with efforts underway to complete it by 2026, marking the centenary of Gaudí’s death. Gaudí’s influence is evident throughout Barcelona, and visitors to the city are encouraged to explore his other works as well.

2. Taj Mahal, Agra, India

The Taj Mahal, a stunning white marble mausoleum, was commissioned in the mid-17th century by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal. Located in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, the Taj Mahal is one of the most revered architectural marvels in the world, celebrated for its intricate design and breathtaking symmetry. In addition to the Taj Mahal, visitors should also explore the nearby Agra Fort, which offers spectacular views of the Taj Mahal and provides a deeper insight into the rich history of the Mughal Empire.

3. Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France

The Palace of Versailles, located just outside Paris, served as the primary residence of French royalty from 1682 until the French Revolution in 1789. This opulent palace is famous for its lavish architecture, expansive gardens, and the iconic Hall of Mirrors. Versailles is easily accessible from Paris and offers various tour options, including a visit to the King’s Bedchamber, the State Apartments, and the historic collection of royal carriages. A stroll through the palace gardens is a must for any visitor.

4. Forbidden City, Beijing, China

The Forbidden City in Beijing was the imperial palace of China during the Ming and Qing dynasties. As one of the most significant cultural landmarks in China, the Forbidden City consists of nearly 1,000 buildings, each steeped in history. The Palace Museum now manages the complex, offering visitors a chance to explore exhibitions showcasing artifacts from the Ming and Qing periods. It is essential to purchase tickets online in advance due to government regulations.

5. Saint Basil’s Cathedral, Moscow, Russia

Located in the heart of Moscow, Saint Basil’s Cathedral is often mistaken as part of the Kremlin, but it actually stands just outside the Kremlin walls on Red Square. Commissioned by Tsar Ivan the Terrible in 1561, the cathedral’s distinctive onion domes and vibrant colors make it one of the most recognizable examples of Russian architecture. Although affiliated with the Russian Orthodox Church, the cathedral is state property, offering tours nearly every day of the year for visitors to experience its historical and cultural significance.

These five architectural landmarks are not only physical structures but also cultural treasures that have stood the test of time. Each landmark tells a story of the people who built them, the societies they served, and the artistic and engineering marvels they represent. Visiting these iconic buildings offers a glimpse into the rich tapestry of human history and the enduring legacy of architectural brilliance

#architectdesign#home interior#interior design#interiordoor#architecture#design#interior decorating#interiors#interiorstyling#home#landmark#residential architects#architecturephotography#amazingarchitecture

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

@themousefromfantasyland @tamisdava2 @mask131 @professorlehnsherr-almashy @princesssarisa

A historic rehabilitation (Moacyr Scliar)

(Published on 07/01/2006 in Zero Hora's Caderno Cultura Understand why, one hundred years later, the Dreyfus Affair – in which an innocent man was sentenced to exile – still reverberates in the consciousness of Europe and the world)

Next July 12th will be important in France, but, we hope, it will have nothing to do with the World Cup. The date marks the centenary of the acquittal of Alfred Dreyfus, an event that ended the judicial part of one of the most controversial cases in modern history.

Remembering: in 1894, Alfred Dreyfus, artillery captain of the French army, was accused of passing military secrets to German embassy in Paris.

The incident soon had great repercussions, because of one detail: Alfred Dreyfus was Jewish, which immediately triggered an anti-Semitic movement of large proportions. Intimidated, the French high command immediately put the officer on trial. The evidence was controversial, to say the least, and the miscarriages of justice numerous, but Dreyfus was nevertheless sentenced to five years in prison on Devil's Island in French Guiana, a place that, due to the terrible conditions, it justified the name.

Two years later, Colonel Georges Picquart took over French counterintelligence and, without delay, managed to find the real spy, an officer named Ferdinand Esterhazy.

He informed his superiors, who, however, decided not to tarnish the honor of the armed forces with a new trial, “because of a Jew.” Picquart protested and was, in turn, arrested. But the evidence in favor of Dreyfus's innocence was growing, released by the Dreyfusards. In 1898, the writer Émile Zona published, in the newspaper L’Aurore, an open letter addressed to the French presidency and which became known by the title given to it by journalist and politician Georges Clemenceau: “J’Accuse”.

The following year, Dreyfus was tried again – and sentenced to 10 years in prison. In 1906, absolution came and along with it moral compensation, in the form of the Legion of Honor.

The Dreyfus case had major repercussions. Firstly, it showed the strength and virulence of the anti-Semitic right in France, a right that would later collaborate with the Nazis, helping in the deportation of thousands of Jews to the extermination camps.

This fact deeply impressed an Austrian journalist who, in Paris, covered the process.

Theodor Herzl was an assimilated Jewish Ma., but, faced with that tide of intolerance, he concluded that for the Jewish Peoplsthere was only one possible solution, the creation of a national State, an objective to which he dedicated his life and which would become a reality with the creation of the State of Israel, in 1948.

On the other hand, the entire debate showed that men of thought, artists, writers can and should take a stand on major political and social issues.

This gave rise to the term intellectual, whose creation is sometimes attributed to Georges Clemenceau, sometimes to right-wing activists.

It referred to a group that was never very well characterized and that soon showed a tendency for splits; thus, the First War opposed nationalists and pacifists, the Russian Revolution created a deadly rivalry between Trotskyists and Stalinists. The prestige of intellectuals reached its peak in the years after World War II, with Jean-Paul Sartre and existentialism.

However, Sartre himself was criticized for his political stances, which included a militant adherence to Maoism.

One hundred years after the Dreyfus case, we see that the dilemmas of that time remain current. Anti-Semitism and other forms of intolerance continue to exist, as evidenced by the statements made by the president of Iran when denying the Holocaust.

The twists and turns of History (the fall of communism, for example) have resulted,��for intellectuals, in perplexity, and it is no wonder that a seminar recently held in our country had as its motto The Silence of Intellectuals.

But perplexity is not defeat, on the contrary. Only fanatics are immutable in their position.

We need the lucidity of men and women who combine intelligence, culture, common sense and emotional balance in analyzing the great dilemmas of our time.

We need the intellectuals.

A warm autumn night in '48 (Moacyr Scliar)

04/30/1998

If I remember correctly, and I think I remember correctly, it was a warm autumn night, that one.

I was walking, somewhat distracted, along the João Telles Street, when I heard, through the open windows, shouts of joy. I didn't immediately realize the reason for the celebration; It was only the next day, I think, that I found out: the State of Israel had been proclaimed.

Bom Fim was not exactly the sounding board for an event that would mark our century, among other reasons because the small Jewish community was very focused on itself.

I don't remember hearing anyone talk about the Holocaust; It is true that sometimes the adults, eyes red with tears, whispered among themselves, but apparently it was only over the years that people realized the magnitude of the tragedy.

But as the days went by, pride took over everyone.

The metamorphosis was visible; emotion took over the Jewish People, a new emotion: pride, born of recovered dignity.

It was no longer a human group that was persecuted and humiliated, threatened by the fires of the Inquisition, pogroms and crematoriums.

Israel appeared on the Jewish horizon like a bright beacon in the dark night.

Even this sensation, however, was marked by uncertainty: the war had begun immediately and the new State seemed helpless in the face of its powerful neighbors.

Day by day we followed the conflict on the radio and in the newspapers and I remember the apprehension with which I read the news about the sending of Czech weapons to Israel. Wouldn't communist support be counterproductive?

An issue that, like many others, was swallowed up by History: the war ended, communist countries stopped supporting Israel and started attacking it, and one day they stopped being communist. Israel defeated its neighbors again in 1967, obtaining territories, but not peace, which continues to be, as it was in 1948, the great objective to be achieved.

The kibbutz, which for us young people meant the materialization of socialist utopia, reached its peak and went into crisis.

On the other hand, religious orthodoxy, which was once more an object of curiosity than anything else, is now an important political force.

Work on the land, seen by the pioneers as the way of redemption for an anomalous people, lost in importance to ultra-sophisticated industry; The export of technology is a source of wealth that has raised Israel's GDP per capita to 17 thousand dollars.

Fifty years later I remember with nostalgia the little boy who walked along João Telles Street. Where was I going again?

Home.

In May 1948, the Jewish people began to have a home.

Many homes: in Israel, in the United States, in Europe, in Porto Alegre.

The world had stopped being strange and hostile for us.

In May 1948 Judaism was reborn from the ashes. To remake its house.

I will get hate because of this: but what's happening?

TW: Antisemitism and Child Trafficking

I know Zionists like to label all criticisms of them as Antisemitism, but these days I'm seeing a huge wave of actual, virulent antisemitism on social media, and even as a non-Jewish person, this is scaring me.

People leaving hundreds of comments containing slurs at any post about Jewish culture and faith, insulting Jewish people at the street, throwing antisemitic slurs even at anti-zionist Jews, treating all Jewish people, even those in diaspora, as if they are all responsible for Israel actions, calling people "Zionist" for just being Jewish.

The worst of the worst is people unironically sharing updated versions of Blood Libel conspiracy theories as if they were absolute truth.

I seeing posts about how Jewish people kidnap children, how secretly they have tunnels underground where they rape the kidnapped children, how the Talmud is a sorcery book containing rituals of child sacrifice.

Now, Jeffrey Epstein is seen as part of a secret Jewish conspiracy of child trafficking.

Forgive my naivety, but I actually thought we had overcome this insanity.

The worst part is that I'm seeing "progressive" and "leftist" accounts sharing and supporting this garbage as well.

The thing that made me write this post, is seeing someone justify hating Jewish people, but Leaftisly.

"They are all rich, white pedophiles. They are a cancer on this world. They are all racist and they all deserve what they got."

The cold and callousness way to dismiss and justify the racism against the victims of one of the most famous mass genocides in History makes me sick. And they used Left wing rhetoric to justify that.

Again, non-Jewish person here, but this is freaking me out.

@ariel-seagull-wings @tamisdava2 @mask131 @princesssarisa @angelixgutz @amalthea9

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Legacy of October Today

Calvin Priest | Socialist Alternative | November 15th 2017 In a world dominated by billionaires and big business, with widespread poverty, racism, sexism and environmental destruction, the question of who runs society is a vital one. One hundred years ago, in October 1917 in Russia, that question was answered decisively when ordinary working people took power and held onto it for the first time […]

→ READ MORE ←

Get your Latest News From The Leftist Front on LeftPress.News → Support Us On Patreon! ←

#leftpress#news#resistance#politics#Centenary of the Russian Revolution#History#Top Stories#Bernie Sanders#Donald Trump#Russian Revolution#Calvin Priest#Socialist Alternative#The Legacy of October Today

1 note

·

View note

Photo

"My son! Go and save your Motherland!" A recruiting poster for the White Volunteer Army in South Russia.

#ww1#ww1 history#ww1 centenary#1918#history#world war one#first world war#great war#russian civil war#russian revolution#white army

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bolsheviks Kill the Czar and His Family

The site of the execution. Most of the damage to the wall was done by investigators after the Whites took Ekaterinburg later in the month.

July 17 1918, Ekaterinburg--After his abdication, the Czar and his family remained at his palace at Tsarskoye Selo, under what amounted to lavish house arrest, while the Provisional Government figured out what to do with him. They had no particular interest in charging him for any crimes, and really just wanted him out of the country. However, he was unpopular abroad as well, and both France and Britain refused to take him in. In August 1917, the Romanovs were transferred to Tobolsk in Siberia, with the eventual hope of moving them to Japan. What luxuries they had were forfeit after the Bolsheviks took power; they no longer had any servants, were put on reduced rations, and, at the end of April 1918, were moved to a modest house in Ekaterinburg.

After the Romanovs’ arrival in Ekaterinburg, however, the Bolsheviks’ fortunes in Siberia took a turn for the worse. The first fighting between the Czechs and the Bolsheviks began in mid-May in Chelyabinsk, just over 100 miles to the south. By July, they had linked up with the Czechs across the Urals in Samara, and were advancing north towards Ekaterinburg to prevent the Bolsheviks from making any move on the Trans-Siberian Railway. The local Bolsheviks believed the Czechs were on their way to liberate the Czar and help to reinstall him on his throne, and decided to execute the Romanovs to prevent this. How much involvement the Bolsheviks in Moscow had with this decision is unclear; official Soviet history held that it was a local decision, but Trotsky and others held that it was decided in Moscow. If it was Lenin’s decision, he was very careful to make sure no paper trail was left.

In the wee hours of July 17, the Romanovs were woken by their doctor and summoned down to the basement of the house, on the pretext that they were to be moved out of Ekaterinburg. At around 2AM, the commandant of the house, Yakov Yurovsky, entered with a Cheka squad and read their sentence: “Nikolai Alexandrovich, in view of the fact that your relatives are continuing their attack on Soviet Russia, the Ural Executive Committee has decided to execute you.” After repeating the order, the firing began. Most of the men aimed at Nicholas or Alexandra, and the children were protected from incidental fire by the large number of gems sewn into their clothing. The guns did not use smokeless powder and it soon became too smoky to continue in the confined space, so they soon turned to bayonets to kill the children, then pistol shots to the head when that failed.

The bodies were disposed of two days later, and the execution of the Czar was publicly announced. The fate of the rest of the family was not discussed openly, but the Whites were able to piece together what happened after they captured Ekaterinburg a week later. They were unable to find the bodies, however, so wild speculation continued until glasnost.

Today in 1917: Churchill Returns; House of Windsor Established Today in 1916: Serbian Army Returns to the Frontline Today in 1915: Women’s Right to Serve March in London Today in 1914: Berchtold Not To Discuss Plans With Italian Allies

#wwi#ww1#ww1 history#ww1 centenary#world war 1#world war i#world war one#the first world war#the great war#Czar Nicholas II#russian civil war#bolsheviks#russian revolution#july 1918

295 notes

·

View notes

Photo

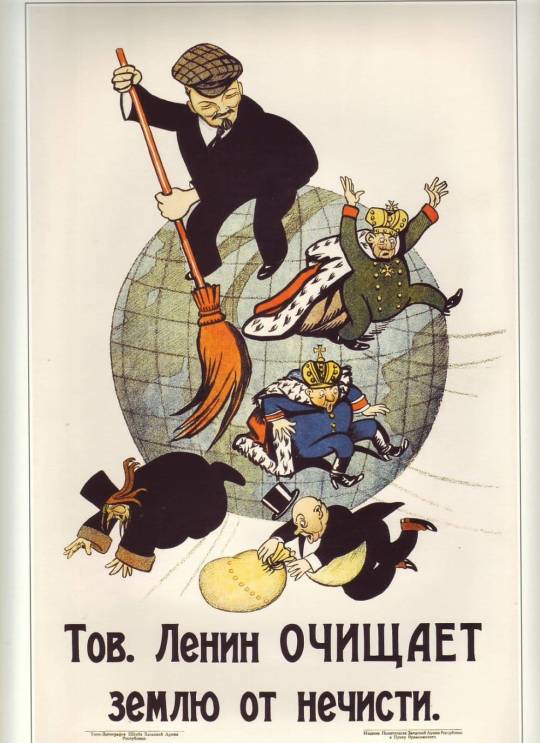

On November 7, 1917 (October 25 by the old Russian calendar), the workers, soldiers and sailors of Petrograd stormed the Winter Palace and put power in the hands of the revolutionary soviets led by Lenin’s Bolshevik communist party.

The world’s first successful socialist uprising literally changed the world – inaugurating the era of national liberation and socialist revolutions.

All Power to the Soviets: a resource on the Russian Revolution The website “All Power to the Soviets,” assembled throughout the revolution’s centenary in 2017, is a great resource on this world historic event that continues to inspire revolutionary workers and oppressed peoples around the world.

"Ten Days the Shook the World" By John Reed

"The History of the Russian Revolution" By Leon Trotsky

"Lessons of October: The Struggle Against Imperialist War" By Sam Marcy

279 notes

·

View notes

Photo

November 6 2017 - Despite the police reinforcements in the centre of the capital, several dozen anarchists marched on the centenary of the revolution. Near Chistye Prudy metro station, the anarchists unfurled a banner that read: ‘Dictatorship, Poverty and Corruption, Only One Way Out – Revolution!’, and briskly marched through the dark streets yelling out slogans calling for class struggle, solidarity, social revolution and the construction of a new, just world.

The action was not permitted – we do not consider it necessary to ask the authorities for permission to march in the street. We can walk and breathe more freely without the accompaniment of a police convoy. Also, in the current conditions of the dictatorship, people are encouraged to participate in actions coordinated by the authorities, where all participants will be recorded and monitored by the police – stupidity and provocation.

Remember, the real social revolution of liberation which the anarchists and revolutionaries of the past dreamed of is not left in the past, but is waiting in the future. Revolution is the only solution to solve all the contradictions and problems that the capitalist system generates. The struggle against individual manifestations of capitalism and the state such as poverty, corruption, police lawlessness and the arbitrariness of the authorities have no prospects unless we take into account the true source of social ills – the state and capitalism.

Otherwise, when trying to solve social contradictions by changing government without destroying the state and creating a new democratic system, new thieves and dictators will simply replace the old ones – which is proven by the experiences of the two revolutions of 1917. And of course this needs to be taken into account in the future.

[video]

#russia#moscow#anarchism#anarchy#revolution#flare#fireworks#gif#2017#black bloc#1917#centenary#russian revolution

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPOILERS FOR THE CENTENARY EP:

Me, after being obsessed with doctor who most of my life and the Russian Revolution being my main historical interest, seeing the Master as Rasputin rumours:

#screaming shaking in excitement#so you're telling me the master is partially responsible for the downfall of the romanovs?? fucking beautiful#aahaahahhhaha i hope they handle this well because if my favourite historical event is fucked up by my favourite show ill scream#dr who#doctor who

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

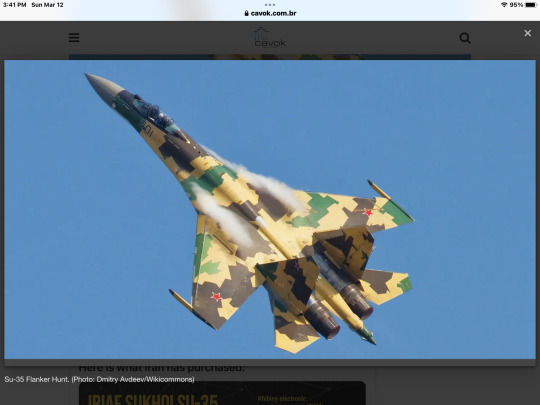

Iran closes agreement with Russia to buy Su-35 fighters

Fernando Valduga By Fernando Valduga 03/11/2023 - 11:15 PM in Military

Iran has reached an agreement to buy advanced Su-35 fighter jets from Russia, Iranian state media said on Saturday, expanding a relationship that saw Iran-made drones used in Russia's war against Ukraine.

"The Sukhoi-35 fighter planes are technically acceptable to Iran and Iran has finalized a contract for their purchase," said the IRIB broadcaster, citing Iran's mission to the United Nations in New York.

The report did not bring any Russian confirmation of the agreement, the details of which were not disclosed. The mission said that Iran also asked about the purchase of military aircraft from several other unidentified countries, IRIB reported.

Su-35 Flanker Hunt. (Photo: Dmitry Avdeev/Wikicommons)

“Russia announced that it was ready to sell them” after the end, in October 2020, of the restrictions on the purchase of conventional weapons by Iran under UN Resolution 2231, said the statement released on Friday by the official IRNA news agency.

Russian President Vladimir Putin met with Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in Tehran last July, emphasizing closer ties in the face of Western pressure on the war in Ukraine.

The reported agreement could include the 24 Su-35SEs once destined for Egypt before the threat of U.S. sanctions and an offer of F-15s.

Kiev accuses Tehran of providing Moscow with "kamikaze" Shahed-136 drones used in attacks on civilian targets since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February last year - an allegation that the Islamic republic denies.

Iran has acknowledged the sending of drones to Russia, but says they were sent before the Moscow invasion of Ukraine last year. Moscow denies that its forces use Iranian-made drones in Ukraine, although many have been shot down and recovered there.

The United States expressed concern about the growing military cooperation between Iran and Russia, with Pentagon spokesman John Kirby warning in December that Russia would probably sell its fighters to Iran.

Kirby stated that Iranian pilots were learning to fly Sukhoi warplanes in Russia and that Tehran could receive the aircraft next year, which would “significantly strengthen Iran’s air force in relation to its regional neighbors.”

Iran's air force has only a few dozen attack aircraft: Russian jets, as well as old U.S. F-4 and F-14 models acquired before the Iranian revolution of 1979.

In 2018, Iran said it had started production of the locally designed Kowsar fighter for use in its air force. The jet is a copy of an F-5 first produced in the United States in the 1960s.

Tags: Military AviationIRIAF - Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force/Iran Air ForceRussiaSu-35 Flankersukhoi

Fernando Valduga

Fernando Valduga

Aviation photographer and pilot since 1992, he has participated in several events and air operations, such as Cruzex, AirVenture, Dayton Airshow and FIDAE. He has works published in specialized aviation magazines in Brazil and abroad. Uses Canon equipment during his photographic work throughout the world of aviation.

Related news

MILITARY

F-104 Starfighter jet will fly in the Italian Air Force centenary air show

12/03/2023 - 16:00

WAR ZONES

Which fight is best for Ukraine while fighting Russia?

12/03/2023 - 13:39

MILITARY

VIDEO: Prototypes of South Korea's KF-21 fighter perform first night flights

11/03/2023 - 19:45

MILITARY

F-35s operate in Denmark for the first time as the country prepares for the arrival of its first JSF

11/03/2023 - 15:11

WAR ZONES

Important Antonov officials prevented Ukrainian forces from protecting the An-225 aircraft

11/03/2023 - 14:02

MILITARY

Spain becomes the largest European PC-21 operator with new order for 16 aircraft

11/03/2023 - 11:44

homeMain PageEditorialsINFORMATIONeventsCooperateSpecialitiesadvertiseabout

Cavok Brazil - Web Creation Tchê Digital

Commercial

Executive

Helicopters

HISTORY

Military

Brazilian Air Force

Space

Specialities

Cavok Brazil - Web Creation Tchê Digital

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Editor's Note: Fiona Hill delivered the fourth and final 2022 Reith Lecture for the BBC on the "Freedom from Fear" on November 15, 2022. Her Reith Lecture aired on December 21, 2022 and may be found on the BBC Radio 4 website.

2022 is the centenary of the BBC. It is also the 100th anniversary of the creation of the USSR from the remnants of the Russian Empire. In 1922, Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks cemented power in Russia after five years of revolution and civil war, all against the backdrop of World War I and the Great Influenza. 1922 was the end of one tumultuous period and the beginning of another, an era that saw the rise of the Soviet Union and other authoritarian states, and a second outbreak of world war.

Today, we are in a similar period of turmoil. Our world is disrupted by a multi-year global pandemic, mounting climate disasters, and wracked by the fear of a nuclear conflict sparked by Vladimir Putin’s efforts to reforge the Russian empire. Since February 24, 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine, we have found ourselves embroiled in what Russian President Putin has called a “Special Military Operation.” In reality, this is a full-blown war. It is the third major power conflict over territory in Europe in just over a century. And like the others before it, this war has global reverberation, threatening the energy, food, and climate security of populations far away from Europe, in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

The hundred-year timespan we acknowledge today, is infused with an eerie parallelism. 1914 saw the beginning of World War I when the German army invaded the “Low Countries” of Belgium and Luxembourg and then France. 2014 was the beginning of the current war in Ukraine, initiated by Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in March that year and the manufacturing of a conflict in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has upended the European and global institutions that underpinned international security after World War II, governed relations among states, and prevented great power conflict during the Cold War. Just as Adolf Hitler seized the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, annexed Austria and invaded Poland in the late 1930s, overturning the post-World War I order, Vladimir Putin has repudiated and violated international norms and agreements. This includes guarantees of Ukraine’s territorial integrity that Russia itself undertook together with the United States and the United Kingdom in 1994.

To “restore” or establish peace again, we will have to come up with some new security arrangements. But, in the meantime, we are at war.

Modern war is fought by a range of means, not just by military forces. It is fought with economic measures, financial sanctions, cyber-attacks, political influence operations, disinformation, and propaganda. Nonetheless, the trench warfare of World War I has its analogues in trenches on the frontlines in Ukraine. Plenty of heavy weapons, men and ammunition have gone to the front. There are high levels of violence. And like the invading German armies of the two previous world wars, Russia has laid waste to Ukrainian cities, towns, and villages. Its military has committed atrocities against civilians. Both the Russian and the Ukrainian sides have incurred significant casualties. Their political rhetoric is increasingly zero-sum, win or lose, with nothing in between. On September 30, 2022, in a speech announcing Russia’s annexation of still-four contested Ukrainian regions: Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson, Russian President Vladimir Putin explicitly declared war on the West.

Putin’s annexation speech also evoked parallels between 1922 and 2022. Putin has said his invasion of Ukraine was necessary to right a historical wrong, correct a mistake made by Lenin and the Bolsheviks when they created a separate Ukrainian socialist republic as part of the Soviet Union in 1922. Ukraine, Putin claims, is a state that should never have existed. And so, Putin is forcing Europe to go back in time. He will now try to make sure that Ukraine is erased from the map.

In another unsettling echo of those times, the stories of Russian soldiers on the battlefield in Ukraine, captured on their phones by Ukrainian military intercepts as they talked to their families, align with the tales of Russian soldiers talking to each other and terrorizing Ukrainian civilians during the Russian civil war in the 1920s. These earlier discussions and exploits were captured by an astute observer of that period, the celebrated Russian writer, Isaac Babel, who was embedded with the revolutionary troops. He recounted them in his famous collection of short stories, “Red Cavalry.”

In these parallel accounts of the 2020s and 1920s, time loops back on itself. Perhaps it even stands still. Or, more likely, the violent patterns of men simply persist, and the fears they engender. Fear has always been a weapon of war as well as a political commodity.

In waging his war in Ukraine, Putin has raised anew the age-old fear of the end of the world, not just the biblical Apocalypse, but the literal end of the world in a nuclear cataclysm. After more than 70 years of the world renouncing the use of nuclear weapons, Putin has threatened the use of one on the battlefield, citing the precedent of the United States detonating atomic weapons over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Putin says he may resort to a nuclear response if Ukraine retakes territory annexed by Russia since 2014.

“Nuclear Armageddon” is emblazoned in newspaper headlines, discussed in political gatherings, featured in academic reports, and provoking nightmares. Ordinary citizens in Europe are stockpiling iodine tables and scoping out Cold War-era fallout shelters. In one report from Rutgers University in the United States, researchers predicted that 5 billion worldwide could starve in the wake of a nuclear conflict between Russia and America. because of the catastrophic disruption of global food supplies.

Vladimir Putin has transformed himself into the much-feared, biblical “four horsemen of the Apocalypse.” In this instance, he is one pale, bare-chested rider, as he was often photographed by Kremlin propagandists during staged “action” holidays in Siberia, but now he’s carrying the banner of a war of conquest in Ukraine, and of a nuclear holocaust that will bring global famine and death in the wake of the coronavirus pestilence.

Putin’s goals in conjuring the Apocalypse are not biblical. They are base and tactical. Russia is not like the United States in the Second World War, seeking to end a brutal, devastating multi-year war in Asia that Japan began. Nor is Putin even pursuing the Soviet Union’s Cold War aim to uphold deterrence and prevent a ruinous superpower conflict by reviving the fear of mutually assured destruction. Putin is not seeking to maintain great power nuclear parity nor strategic stability with the United States. There has been no change in the nuclear balance. The United States has not threatened Russia, nor has any other nuclear power.

Instead, Putin threatens a pre-emptive, one-sided, use of a nuclear weapon because he is losing the war that he himself started in Ukraine in February 2022. Putin’s Nuclear Armageddon is nothing more than nuclear blackmail. Putin is playing on “the sum of everyone’s fears.” His aim is to end American and European military support to Kyiv, to force the capitulation of Ukraine’s government, and to ensure the surrender of Ukrainian territory to Russia.

Now, of course, this threat of Nuclear Armageddon is not new; dire predictions have been made before. And during the Cold War, the world teetered on the precipice of a superpower nuclear conflict at least twice, first during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, and again during the Euromissile War Scare in 1983. Indeed, the 1980s were replete with academic studies and government reports describing how a nuclear conflict would lead to sun-blocking soot and ash killing crops. Then, the already looming threat of climate change faded into the insignificance against the threat of a “nuclear winter.” TV series like “The Day After” in the United States in 1983, and films like “Threads” in the United Kingdom in 1984, horrified and terrified American and British publics with harrowing depictions of the aftermath of a nuclear exchange.

Now, I was a teenager in the 1980s, filled with fear at the prospect of imminent nuclear war. My teenage self checked out hiding spots. Under the dining room table, in the cupboard under the stairs, and behind the thick yellow curtains my parents hung in the front room to protect our eyes from the blinding flash of the first explosion. I contemplated cowering in a ditch, if I was caught outside when the missiles struck but nothing seemed much of a defence in those circumstances. Safety was an illusion. Fears crowded my mind and fogged my brain. I had my own frequent nightmares of Nuclear Armageddon, although Vladimir Putin, the pale horseman was still a long way off in the future.

At the suggestion of an elderly relative who had survived the horrors of World War II, I decided to confront the fears head-on. I would study Russian and try to visit the USSR. I would assert my own agency, and fight fear with information and knowledge. I began my studies in 1984 and I ended up as an exchange student in Moscow in 1987 and 1988. The nightmares disappeared as soon as I got there and saw the place and met the people for myself. These nightmares have never returned, despite Vladimir Putin’s best efforts. And after years of studying Russian and Russia, and decades of closely analyzing Putin, I know he is just a man, operating in his own specific context. He has predictable patterns. He can be countered. And resorting to the use of a nuclear weapon would be an enormous gamble, even for someone who can be as reckless and ruthless as Putin.

Nonetheless, Vladimir Putin is a master at manipulating fear. He knows fear’s value as a political commodity. He knows how to deploy fear for maximum effect. Putin has long threatened to play the nuclear card, because he knows the psychological impact it has and the sense of helplessness and hopelessness it engenders. During a bilateral U.S.-Russian meeting at the G20 in Osaka in 2019, where I was present, Putin warned President Donald Trump that he, Putin, would stir up all the old fears of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Euromissile Crisis if the U.S. did not engage in arms control negotiations on his terms. He bragged that Russia had developed sophisticated nuclear weapons systems that the U.S. still did not have. He was ready to press his nuclear advantage even before the war in Ukraine, and to play on our fears.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who we celebrate in this lecture series’ focus on the “Four Freedoms,” outlined in his 1941 State of the Union address all of the fears and the freedoms. He fully understood the political salience of fear. FDR knew that people could be paralyzed by the fear of poorly understood events. They were prone to the manipulation of their fears and thus intimidation and exploitation. If people were filled with fear, they were incapable of taking the necessary individual and collective action to deal with a disaster.

Now fear, of course, is a normal response to a real or perceived threat. All animals exhibit fear, both predators and prey. And a sense of fear is essential to prepare for risk and act in the case of danger ahead but fear is often engendered by something more imagined than real. We fear what we don’t know, not just what we do, like the danger of nuclear weapons.

In the case of real dangers, a healthy dose of fear is critical to living with their ever-present possibility. You can’t have freedom from danger, but you can have freedom from fear. There will always be hidden dangers, but you can do something about them. You can prepare yourself for danger, insure against danger. Freedom from fear is essential for personal and societal resilience in the face of peril.

This takes me back to my studies of Russian. The Russian word for insurance is actually based on this very concept that I’ve just outlined, the idea of protection from fear or strakh. The word “insurance” in Russian is proof or preparation against fear, strakhovaniye. And indeed, having insurance in any form helps to relieve fear through the knowledge that you are prepared for the inevitability of danger and the risk of something happening. You are ready to deal with it.

In contrast to this pleasing synergy between the word and its meaning, the Russian word for security is less satisfying and a lot more troubling. Security is something Vladimir Putin always craves, and states it is his imperative in everything that he does, including invading Ukraine. He’s invaded Ukraine to ensure Russia’s security by taking Ukraine off the map. Now, the Russian word for security is bezopasnost’ or literally, “without danger.” In effect, the Russian word for security is “safety” in absolute terms. This suggests that the Russian idea or concept of security seeks the impossible, the creation of a world without danger, where everyone can be completely safe at all times.

The sense of that kind of security or safety will always be false, as false as the words of leaders who promise it to themselves and their followers. In this conception of security, there can be no freedom from fear. Danger will always be there. It cannot be eliminated. And fear will also always be present because we can never be in complete control. We cannot have absolute safety; we can only have insurance and prepare ourselves to deal with danger.

Just as Vladimir Putin wants his version of security, he also wants control of events. Indeed, most of us would like the same thing. We are afraid of the sudden loss of control in our ever-complex world. At times of conflict, or when major societal changes happen rapidly and in combination, fear predominates. We are plunged into what the insightful scholar of the twentieth century, Fritz Stern, called “cultural despair.” Stern focused on the fears that roiled Germany in the turbulent period between World War I and World War II. He described cultural despair as the sense of loss, grievance, and anxiety that occurs when people feel dislocated from their communities and broader society, as everything and everyone shifts around them.

Cultural despair leads to populism in politics, and from there to authoritarianism, as Stern noted in tracking the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany. Populism and authoritarianism are rooted in fear; fear of loss, fears from the past and fears of the future, fears of the other, like refugees, migrants, people who are simply different, and people who might think differently from the mainstream. All these fears emerge when societies undergo change. Populism shaped European and U.S. politics in the 1920s and 1930s after World War I and the 1918 influenza epidemic and the Great Depression. It arose again in the 1960s and in the 1980s during generational and technological shifts. Vladimir Putin is a populist who came to power after a decade of political turmoil and economic collapse in Russia. Putin promised to provide security and safety, as well as prosperity, as long as Russians acquiesced to his ultimate authority.

And throughout history, fear has been used by more powerful people to prey on the weak during difficult times. Populists today, like Putin in Russia, Donald Trump in the United States, Narendra Modi in India, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, and also Xi Jinping in China, appeal to people who fear they have lost their livelihoods along with their identities and their cultural moorings at times of rapid social change and political and economic uncertainty. They present themselves as strongmen leaders who can restore order from the chaos.

Back in the 1920s, populism spurred the emergence of the Soviet Union, an authoritarian propagandist state whose Bolshevik leaders established power through intimidation and violence and then ruled by fear. The Soviet Union rose alongside fascist Germany, Italy, and Spain. And in these authoritarian states, fear prevented people from achieving self-actualization and deprived them of individual agency. The fear that authoritarianism could also take root in the United Kingdom or the United States, inspired George Orwell’s novel, 1984.

Orwell’s statue stands outside the entrance to the BBC in London’s Portland Place. He worked there in the 1940s, during the Second World War, having fought against fascism in Spain in the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s. One of Orwell’s quotes, etched on the wall behind his statue, and it reads: “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.” Or perhaps what they fear to hear, which is often the same thing. And perhaps Orwell’s greatest fear was the loss of freedom. In the novel, 1984, fear of the truth leads to the imposition of state control and the loss of the individual.

As I mentioned, 1984 was the year I went to university, right after the Euromissile war scare of 1983. One of first novels I read at university, in my Russian literature class, was from the 1920s, Yevgeniy Zamyatin’s Miy, or “We,” which, it turned out, was the literary precursor of Orwell’s 1984.

The mass societies of the United States, United Kingdom and the USSR all rose and came together in the 1920s. Zamyatin was an astute observer of the rapid societal changes that accompanied the development of heavy industry and large-scale manufacturing in the early 20th Century. He spent time working in the shipyards of Newcastle and Tyne in the North East of England, not far from my hometown, just before the Bolshevik Revolution. The focus of Zamyatin’s book is the creation of an impersonal authoritarian system built on the deprivation of knowledge and manipulation of fear. In “We,” individuals in a mass society are manipulated by “Him,” “The Benefactor,” a strongman on high. They are transformed into a homogenous, cowed collective. And Zamyatin soon found himself in the same situation. He fell victim to Stalin’s repression and purges in the late 1930s, just around the time that George Orwell was beginning his own explorations of working-class life in northern England.

Orwell’s fear of the loss of individual freedom, the degeneration of the state and the rise of tyranny seems as relevant today as it did in the 1940s or in the actual 1984. In this context, it is worth bearing in mind that the BBC was the product of this same emergent mass society that Zamyatin and Orwell observed, but the BBC was ultimately intended to liberate the masses from the deprivation of knowledge and the manipulation of fear.

Because the BBC is framed around the idea of equal access to information. It is rooted in the concept that knowledge and reasoning are the antidote to fear. The importance of having an educated, self-motivated and responsible population was actually at the heart of the BBC’s creation. In 1919, the British government issued its “Final Report on Adult Education in the UK,” which advocated the “permanent national necessity” of establishing a system of adult education to keep up with the unfolding democratic, societal, and industrial challenges of the post-World War I era.

The report concluded that British people should be able to decide what they wanted to learn for themselves. They should think for themselves and make informed judgements. The British educational system should facilitate individual agency and critical thinking and the BBC was intended as an informational instrument, a tool for people to gain useful knowledge.

So, confronting fear involves access to knowledge, reasserting agency. And as I learned through studying Russian, we can dispel and manage fears through education, advance preparation, and training. Dealing with danger requires paying attention and asking questions. And no great achievement by individuals or humanity throughout history has ever been possible without this combination of elements.

So, in concluding, let us consider again the current war in Ukraine. Despite the horrors of the conflict, Ukrainians have confronted their fear and exercised their own agency. They have learned from their mistakes as well as from Russia’s and Vladimir Putin’s. Ukrainians have refused to be cowed or intimidated. They have taken collective action to fight back against tyranny and authoritarianism. The odds are stacked against them, but they have turned fear into courage.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snow White, Revolutionary Red

Explore the life of a British Spy #BLRussia1917 @BritishLibrary #1917Live #ArthurRansome

Marking the centenary of 1917, the British Library’s Russian Revolution: Hope, Tragedy, Myths traces the revolution through the paper ephemera left behind. With its almost textbook layout, the exhibition untangles the revolution from its earliest roots in 1896 to the aftermath and final victory of the Red Army in 1924 and lays it out in a series of cause and effect. © Nick Wood Despite the…

View On WordPress

#1917#20th Century#Arthur Ransome#British LIbrary#Centenary#China Mieville#Espionage#Historical fiction#London#Marcus Sedgewick#October Revolution#Russia#Russian Civil War#Russian Revolution#Spies#Storytelling#World War One

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This year marks the centenary of the beginning of the Russian Revolution, a two-stage revolution in 1917 which overthrew Russia’s tsarist autocracy and prompted the rise of the Soviet Union. To mark the anniversary, we’ve put together a reading list examining the social, political, and economic aspects of the revolution:

"Youth, It's Your Turn!": Generations and the Fate of the Russian Revolution, Journal of Social History

The fiscal background of the Russian Revolution, European Review of Economic History

Towards a New Structural Theory of Revolution: Universalism and Community in the French and Russian Revolutions, The English Historical Review

Bone of Contention: Bolsheviks and the Struggle against Relics 1918-1930, Past & Present

Did Ivan’s vote matter? The political economy of local democracy in Tsarist Russia, European Review of Economic History

Image credit: St. Petersburg by MariaShvedova. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

#Russian Revolution#centenary of Russian Revolution#Russia's tsarist autocracy#Soviet Union#Tsarist Russia#St. Petersburg#French and Russian Revolutions#Bolsheviks#Journal of Social History

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

September 9, 1918 - “Red Terror” in Full Swing

Pictured - The chief targets of the 1918 Red Terror were the Russian bourgeois. Many Russians saw a chance to get even with a bourgeois class that had trampled over them for centuries.

After surviving a failed assassination attempt in August, Lenin ordered for extreme counter-measures to be taken. A state of “terror” was legalized, under which all enemies of the Bolshevik revolution were to be punished. Lenin’s first targets were the Socialist Revolutionaries, a left-wing party but one which opposed the Bolsheviks. It had been an SR named Fanny Kaplan that had tried to shoot Lenin.

The Bolshevik’s internal security force, the Cheka, went to work with relish. In Kiev, the Cheka news organ announced the Terror as a period of regenerative violence.

"We reject the old morality and ‘humanity’ invented by the bourgeoisie in order to oppress and exploit the lower classes. Our morality does not have a precedent, our humanity is absolute because it rests on a new ideal: to destroy any form of oppression and violence. To us, everything is permitted because we are the very first to raise our swords not to oppress and enslave, but to release humanity from its chains... Blood? Let blood be shed! Only blood can dye the black flag of the pirate bourgeoisie, turning it once and for all into a red banner, flag of the Revolution. Only the old world's final demise will free us forever from the return of the jackals."

For many Russians, however, the Terror was not about ideology, but about getting even with a monarchy that had oppressed them and kept them in miserable conditions for centuries. (Such as in Finland, where a failed revolution that summer led to thousands of workers being executed.) The bourgeois were the chief victims of the Terror. Several thousand bourgeois prisoners were massacred in the first weeks. Years of resentment bubbled up into two months of ultraviolent bloodshed, with the Cheka executing perhaps 10-15,000 by the end of October 1918.

#ww1#ww1 history#ww1 centenary#1918#history#world war one#first world war#great war#russian revolution#russian civil war#russian history

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

Left SRs Assassinate German Ambassador

Maria Spiridonova (1884-1941), head of the Left SRs. On July 6, she announced the assassination of Count Mirbach to the Congress of Soviets. Shortly thereafter, the Bolsheviks took her and the other Left SR members present there hostage.

July 6 1918, Moscow--The last non-Bolshevik party still supporting Lenin’s Sovnarkom was the Left SRs, the faction of Socialist Revolutionaries that did not opposed the October Revolution. However, by mid-1918, relations were strained. The Bolsheviks, not wanting to share power with them, had tried to sideline Left SR-dominated soviets. Furthermore, they had key differences on agricultural policy, and above all, the relationship with Germany; the Left SRs firmly opposed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

In the early afternoon of July 6, two Left SR agents assassinated the German Ambassador, Count Mirbach. Later that day, the Left SR Central Committee justified the action:

Count Mirbach, torturer of the Russian toilers, friend and favorite of [Kaiser] Wilhelm, has been killed by the avenging hand of a revolutionary in accordance with the resolution of the Central Committee of the Left SR Party. German spies and traitors demand the death of the Left SRs. The ruling group of Bolsheviks, fearing undesirable consequences for themselves, continue to obey the orders of German hangmen.

The Left SRs’ motivations remain unclear. Soviet historiography always painted the incident as the start of a general uprising against the Bolsheviks. However, the Left SRs took few open steps against the Bolsheviks. They did mobilize some of their military units as a precautionary measure, briefly occupied the telegraph exchange, and took Felix Dzerzhinsky (head of the Cheka) hostage after he came looking for the assassins. However, otherwise, the Left SRs took no hostile action against the Bolsheviks, and did nothing beyond criticizing their foreign policy in their rhetoric. It seems most likely that the Left SRs simply wanted to provoke a break with Germany and stop the Bolsheviks from continuing to give active aid to the Germans under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

The Left SRs’ case was not helped by a simultaneous uprising of Right SRs in Yaroslavl under Boris Savinkov. Savinkov had been in contact with the Allies, and believed they would soon land at Archangelsk and send him aid by railway. However, the Allies would not land there for another month, by which time the Bolsheviks had retaken Yaroslavl.

In Moscow, Lenin gathered what loyal troops he could, mainly consisting of various detachments of the Latvian Rifles. Late in the morning of July 7, the Latvians attacked the Left SR headquarters, and the “uprising” in Moscow was soon over.

Today in 1917: Kornilov Continues Kerensky Offensive Today in 1916: Lloyd George Made Minister of War Today in 1915: Franco-British Conference at Calais Today in 1914: Kaiser Wilhelm Departs on Cruise to Norway.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War.

#wwi#ww1#ww1 history#ww1 centenary#world war 1#world war i#world war one#the first world war#the great war#socialism#bolsheviks#russian civil war#russian revolution#lenin#vladimir lenin#july 1918#moscow

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

All Power to the Soviets: a resource on the Russian Revolution

Nov. 7 is the anniversary of the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia, which marked the beginning of the era of socialist revolutions and national liberation.

The website “All Power to the Soviets,” assembled throughout the revolution’s centenary in 2017, is a great resource on this world historic event that continues to inspire revolutionary workers and oppressed peoples around the world. https://allpowertothesoviets.wordpress.com

#Russian Revolution#bolsheviks#soviets#communist#socialism#revolution#Russia#USSR#Soviet Union#Marxism#Lenin#Trotsky

54 notes

·

View notes

Quote

…another triad of the universal, the particular, and the singular should be brought into play: the triad of (universal) mass uprising, the (particular) political organization, and … what should stand for the singular? This third element brings us back to Lenin, with whom we began the chapter. In the overflow of celebratory reactions to the centenary of the October Revolution in 2017, its central lesson for today passed unnoticed (or was mentioned as a proof that the October Revolution was a coup performed by a secretive group and not a true popular uprising at all). This lesson concerns the unique collaboration between Lenin and Trotsky. The kernel of Lenin’s ‘utopia’ arises out of the ashes of the catastrophe of 1914, in his settling of accounts with the Second International orthodoxy: the radical imperative to smash the bourgeois state, which means the state as such, and to invent a new communal social form without a standing army, police or bureaucracy, in which all could take part in the administration of social matters. This was for Lenin no theoretical project for some distant future – in October 1917, Lenin claimed that ‘we can at once set in motion a state apparatus constituting of ten if not twenty million people.’42 This urge of the moment is the true utopia. What one should stick to is the madness (in the strict Kierkegaardian sense) of this Leninist utopia – if anything, Stalinism stands for a return to the realistic ‘common sense’. One cannot overestimate the explosive potential of The State and Revolution – in this book, ‘the vocabulary and grammar of the Western tradition of politics was abruptly dispensed with.’43 What then followed can be called, borrowing the title of Althusser’s text on Machiavelli, La solitude de Lénine: the time when he basically stood alone, struggling against the current in his own party. When, in his ‘April Theses’ of 1917, Lenin discerned the Augenblick, the unique chance for a revolution, his proposals were first met with stupor or contempt by a large majority of his party colleagues. Within the Bolshevik party, no prominent leader supported his call to revolution, and Pravda took the extraordinary step of dissociating the party, and the editorial board as a whole, from Lenin’s ‘April Theses’ – far from being an opportunist flattering and exploiting of the prevailing mood of the populace, Lenin’s views were highly idiosyncratic. Bogdanov characterized the ‘April Theses’ as ‘the delirium of a madman’,44 and even Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin’s wife, concluded that ‘I am afraid it looks as if Lenin has gone crazy.’45 In February 1917 Lenin was stranded in Zurich, with no reliable contacts in Russia, learning about events there mostly from the Swiss press; in October, he led the first successful socialist revolution – so what happened in between? In February, Lenin immediately perceived the revolutionary chance, the result of unique contingent circumstances – if the moment wasn’t seized, the chance for revolution would be forfeited, perhaps for decades. Even a couple of days before the October Revolution, Lenin wrote: ‘The triumph of both the Russian and the world-revolution depends on a two or three days’ struggle.’ In his stubborn insistence that one should take the risk and pass to the act, Lenin was alone, ridiculed by the majority of the Central Committee members of his own party. However, indispensable as Lenin’s personal intervention was, one should not modify the story of the October Revolution into that of the lone genius confronted with the disoriented masses and gradually imposing his vision. Lenin succeeded because his appeal, while bypassing the party nomenklatura, found an echo in what one is tempted to call revolutionary micropolitics: the incredible explosion of grass-roots democracy, of local committees popping up all around Russia’s big cities and, while ignoring the authority of the ‘legitimate’ government, taking things into their hands. This is the untold story of the October Revolution, the obverse of the myth of the tiny group of ruthless, dedicated revolutionaries accomplishing a coup d’état … On the other hand, the notion that a tiny group of ruthless, dedicated revolutionaries accomplished a coup d’état is not just a myth – there is a crucial grain of truth in it. When popular dissatisfaction grew and Lenin’s idea that a revolutionary situation was emerging began to be accepted, the majority of the Bolshevik party leaders wanted to organize a mass popular uprising. Trotsky, however, advocated a view that, to traditional Marxists, couldn’t but appear as ‘Blanquist’: a narrow, well-trained elite should take power. After a short oscillation, Lenin defended Trotsky, specifying why Trotsky is not advocating Blanquism: In [a] letter of October 17, Lenin defended Trotsky’s tactics: ‘Trotsky is not playing with the ideas of Blanqui,’ he said. ‘A military conspiracy is a game of that sort only if it is not organized by the political party of a definite class of people and if the organizers disregard the general political situation and the international situation in particular. There is a great difference between a military conspiracy, which is deplorable from every point of view, and the art of armed insurrection.’46 In this precise sense, ‘Lenin was the “strategus”, idealist, inspirer, the deus ex machina of the revolution, but the man who invented the technique of the Bolshevik coup d’état was Trotsky.’47 Against later ‘Trotskyite’ defenders of an (almost) ‘democratic’ Trotsky who advocates authentic mass mobilization and grass-roots democracy, one should emphasize that Trotsky was all too aware of the inertia of the masses – the most one can expect of the ‘masses’ is chaotic dissatisfaction. A tightly defined, well-trained revolutionary force should use this chaos to strike at power and thereby open up the space in which the masses can really organize themselves … Here, however, the crucial question arises: what does this narrow elite do? In what sense does it ‘take power’? The true novelty of Trotsky becomes visible here: the striking force does not ‘take power’ in the traditional sense of a palace coup d’état, occupying government offices and army headquarters, it does not focus on confronting the police or the army on the barricades. Let us quote some passages from Curzio Malaparte’s unique The Technique of Coup d’État (1931) to get the taste of it: 'Kerenski’s police and the military authorities were especially concerned with the defence of the State’s official and political organizations: the Government offices, the Maria Palace where the Republican council sat, the Tauride Palace, seat of the Duma, the Winter Palace, and General Headquarters. When Trotsky discovered this mistake he decided to attack only the technical branches of the national and municipal Government. Insurrection for him was only a question of technique. ‘In order to overthrow the modern State,’ he said, ‘you need a storming party, technical experts and gangs of armed men led by engineers.’ While Trotsky was organizing the coup d’état on a rational basis, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party was busy organizing the proletarian revolution. Stalin, Sverdlov, Boubrov, Ouritzki, and Dzerjinski, the members of this committee who were developing the plan of the general revolt, were nearly all openly hostile to Trotsky. These men felt no confidence in the insurrection as Trotsky planned it, and ten years later Stalin gave them all the credit for the October coup d’état. On the eve of the coup d’état, Trotsky told Dzerjinski that Kerenski’s government must be completely ignored by the Red Guards; that the chief thing was to capture the State and not to fight the Government with machine-guns; that the Republican Council, the Ministries and the Duma played an unimportant part in the tactics of insurrection and should not be the objectives of an armed rebellion; that the key to the State lay, not in its political and secretarial organizations nor yet in the Tauride, Maria or Winter Palaces, but in its technical services, such as the electric stations, the telephone and telegraph offices, the port, gasworks and water mains Trotsky thus targeted the material (technical) grid of power (railways, electricity, water supply, post, etc.), the grid without which state power hangs in the void and becomes inoperative. Let the mobilized masses fight the police and storm the Winter Palace (an act without any real relevance): the essential move is accomplished by a tiny, dedicated minority … Instead of indulging in a miserable moralist-democratic rejection of such a procedure, one should rather analyse it coldly and think about how to apply it today, since this insight of Trotsky has gained new actuality with the progressive digitalization of our lives in what could be characterized as the new era of posthuman power. Most of our activities (and passivities) are now registered in some digital cloud that also permanently evaluates us, tracing not only our acts but also our emotional states; when we experience ourselves as free to the utmost (surfing the web, where everything is available), we are totally ‘externalized’ and subtly manipulated. The digital network gives new meaning to the old slogan ‘the personal is political’. And it’s not only the control of our intimate lives that is at stake: everything is today regulated by some digital network, from transport to health, from electricity to water. That’s why the web is now our most important commons, and the struggle for its control is the struggle today. The enemy is the combination of privatized and state- controlled commons, corporations (Google, Facebook) and state security agencies (NSA). But we know all this, so where does Trotsky enter? The digital network that sustains the functioning of our societies as well as their control mechanisms is the ultimate figure of the technical grid that sustains power – and does this not confer a new lease of life on Trotsky’s idea that the key to the State lies not in its political and secretarial organizations but in its technical services? Consequently, in the same way that, for Trotsky, taking control of the post, electricity, railways and so on was the key moment of the revolutionary seizure of power, is it not the case that today the ‘occupation’ of the digital grid is absolutely crucial if we are to break the power of the state and capital? And, in the same way that Trotsky required the mobilization of a tight, disciplined ‘storming party, technical experts and gangs of armed men led by engineers’ to resolve this ‘question of technique’, the lesson of the last decades is that neither massive grass-roots protests (as we have seen in Spain and Greece) nor well-organized political movements (parties with elaborated political visions) are enough – we also need a narrow, striking force of dedicated ‘engineers’ (hackers, whistle-blowers …) organized as a disciplined conspiratorial group. Its task will be to ‘take over’ the digital grid, to rip it out of the hands of corporations and state agencies that now de facto control it. WikiLeaks was here just the beginning, and our motto should be here a Maoist one: Let a hundred WikiLeaks blossom! The panic and fury with which those in power, those who control our digital commons, reacted to Assange is a proof that such an activity hits the nerve. There will be many blows below the belt in this fight – our side will be accused of playing into the enemy’s hands (like the campaign against Assange for being in the service of Putin), but we should get used to it and learn to strike back with interest, ruthlessly playing one side against another in order to bring them all down. Were Lenin and Trotsky also not accused of being paid by the Germans and/or by Jewish bankers? As for the scare that such an activity will disturb the functioning of our societies and thus threaten millions of lives: we should bear in mind that it is those in power who are ready to selectively shut down the digital grid to isolate and contain protests – when massive public dissatisfactions explode, the first move is always to disconnect the internet and mobile phones. We need thus the political equivalent of the Hegelian triad of the universal, the particular, and the singular. Universal: a mass upheaval, in the Podemos style. Particular: a political organization that can translate the dissatisfaction into an operative political programme. Singular: ‘elitist’ specialized groups which, acting in a purely ‘technical’ way, undermine the functioning of state control and regulation. Without this third element, the first two remain impotent.

Like A Thief In Broad Daylight: Power in the Era of Post-Human Capitalism,

by Slavoj Žižek

#Slavoj Žižek#zizek#books#quotes#philosophy#politics#cyberpunk#digital#culture#rebellion#revolution#protest#socialism#communism

4 notes

·

View notes