#Battle of Trenton

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Captain Alexander Hamilton: A Timeline

As Alexander Hamilton’s time serving as Captain of the New York Provincial Company of Artillery is about to become my main focus within The American Icarus: Volume I, I wanted to put a timeline together to share what I believe to be a super fascinating period in Hamilton's life that’s often overlooked. Both for anyone who may be interested and for my own benefit. If available to me, I've chosen to hyperlink primary materials directly for ease. My main repositories of info for this timeline were Michael E. Newton's Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton and The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series on Founders Online, and the Library of Congress, Hathitrust, and the Internet Archive. This was a lot of fun to put together and I can not wait to include fictionalizations of all this chaos in TAI (literally, 20-something chapters are dedicated to this) hehehe....

Because context is king, here is a rundown of the important events that led to Alexander Hamilton receiving his appointment as captain:

Preceding Appointment - 1775:

February 23rd: The Farmer Refuted, &c. is first published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer. The publication was preceded by two announcements, and is a follow up to a string of pamphlet debate between Hamilton and Samuel Seabury that had started in the fall of 1774. The Farmer Refuted would have wide-reaching effects.

April 19th: Battles of Lexington and Concord — The first shots of the American War for Independence are fired in Lexington, Massachusetts, and soon followed by fighting in Concord, Massachusetts.

April 23rd: News of Lexington and Concord first reaches New York. [x] According to his friend Nicholas Fish in a later letter, "immediately after the battle of Lexington," Hamilton "attached himself to one of the uniform Companies of Militia then forming for the defense of the Country by the patriotic young men of this city." It is most likely that Hamilton enlisted in late April or May of 1775, and a later record of June shows that Hamilton had joined the Corsicans (later named the Hearts of Oak), alongside Nicholas Fish and Robert Troup (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 127; for Fish's letter, Newton cites a letter from Fish to Timothy Pickering, dated December 26, 1823 within the Timothy Pickering Papers of the Massachusetts Historical Society).

June 14th: Within weeks of his enlistment, Hamilton's name appears within a list of men from the regiments throughout New York that were recommended to be promoted as officers if a Provencal Company should be raised (pp. 194-5, Historical Magazine, Vol 7).

June 15th: Congress, seated in Philadelphia, establishes the Continental Army. George Washington is unanimously nominated and accepts the post of Commander-in-Chief. [x]

Also on June 15th: Alexander Hamilton’s Remarks On the Quebec Bill: Part One is published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer.

June 22nd: The Quebec Bill: Part Two is published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer.

June 25th: On their way to Boston, General Washington and his generals make a short stop in New York City. The Provincial Congress orders Colonel John Lasher to "send one company of the militia to Powle's Hook to meet the Generals" and that Lasher "have another company at this side (of) the ferry for the same purpose; that he have the residue of his battalion ready to receive" Washington and his men. There is no confirmation that Alexander Hamilton was present at this welcoming parade, however it is likely, due to the fact that the Corsicans were apart of John Lasher's battalion. [x]

Also on June 25th: According to a diary entry by one Ewald Shewkirk, a dinner reception was held in Washington's honor. It is unknown if Hamilton was present at this dinner, however there is no evidence to suggest he could not have been (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 129; Newton cites Johnston, Henry P. The Campaigns of 1776 around New York and Brooklyn, Vol. 2, pg. 103).

August 23-24th: According to his friend Hercules Mulligan decades later in his “Narrative” (being a biographical sketch, reprinted in the William & Mary Quarterly alongside a “Narrative” and letters from Robert Troup), Hamilton and himself took part in a raid upon the city's Battery with a group composed of the Corsicans and some others. They managed to haul off a good number of the cannons down in the city Battery. However, the Asia, a ship in the harbor, soon sent a barge and later came in range of the raiding party itself, firing upon them. According to Mulligan, “Hamilton at the first firing [when the barge appeared with a small gun-crew] was away with the Cannon.” Mulligan had been pulling this cannon, when Hamilton approached and asked Mulligan to take his musket for him, taking the cannon in exchange. Mulligan, out of fear left Hamilton’s musket at the Battery after retreating. Upon Hamilton’s return they crossed paths again and Hamilton asked for his musket. Being told where it had been left in the fray, “he went for it, notwithstanding the firing continued, with as much unconcern as if the vessel had not been there.”

September 14th: The Hearts of Oak first appear in the city records. [x] Within the list of officers, Fredrick Jay (John Jay’s younger brother), is listed as the 1st Lieutenant, and also appears in a record of August 9th as the 2nd Lieutenant of the Corsicans. This, alongside John C. Hamilton’s claims regarding Hamilton’s early service, has left historians to conclude that either the Corsicans reorganized into the Hearts of Oak (this more likely), or members of the Corsicans later joined the Hearts of Oak.

December 4th: In a letter to Brigadier General Alexander McDougall, John Jay writes “Be so kind as to give the enclosed to young Hamilton.” This enclosure was presumably a reply to Hamilton’s letter of November 26th (in which he raised concern for an attack upon James Rivington’s printing shop), however Jay’s reply has not been found.

December 8th: Again in a letter to McDougall, Jay mentions Hamilton: “I hope Mr. Hamilton continues busy, I have not recd. Holts paper these 3 months & therefore cannot Judge of the Progress he makes.” What this progress is, or anything written by Hamilton in John Holt’s N. Y. Journal during this period has not been definitively confirmed, leaving historians to argue over possible pieces written by Hamilton.

December 31st: Hamilton replies to Jay’s letter that McDougall likely gave him around the 14th [x]. Comparing the letters Hamilton sent in November and December I will likely save for a different post, but their differences are interesting; more so with Jay’s reply having not been found.

These mentionings of Hamilton between Jay and McDougall would become important in the next two months when, in January of 1776, the New York Provincial Congress authorized the creation of a provincial company of artillery. In the coming weeks, Hamilton would see a lot of things changing around him.

Hamilton Takes Command - 1776:

February 23rd: During a meeting of the Provincial Congress, Alexander McDougall recommends Hamilton for captain of this new artillery company, James Moore as Captain-Lieutenant (i.e: second-in-command), and Martin Johnston for 1st Lieutenant. [x]

February-March: According to Hercules Mulligan, again in his “Narrative”, "a Commission as a Capt. of Artillery was promised to" Alexander Hamilton "on the Condition that he should raise thirty men. I went with him that very afternoon and we engaged 25 men." While it is accurate that Hamilton was responsible for raising his company, as acknowledged by the New York Provincial Congress [later renamed] on August 9th 1776, Mulligan's account here is messy. Mulligan misdates this promise, and it may not have been realistic that they convinced twenty-five men to join the company in one afternoon. Nevertheless, Mulligan could have reasonably helped Hamilton recruit men between the time he was nominated for captancy and received his commission.

March 5th: Alexander Hamilton opens an account with Alsop Hunt and James Hunt to supply his company with "Buckskin breeches." The account would run through October 11th of 1776, and the final receipt would not be received until 1785, as can be seen in Hamilton's 1782-1791 cash book.

March 10th: Anticipating his appointment, Hamilton purchases fabrics and other materials for the making of uniforms from a Thomas Garider and Lieutenant James Moore. The materials included “blue Strouds [wool broadcloth]”, “long Ells for lining,” “blue Shalloon,” and thread and buttons. [x]

Hamilton later recorded in March of 1784 within his 1782-1791 cash book that he had “paid Mr. Thompson Taylor [sic: tailor] by Mr Chaloner on my [account] for making Cloaths for the said company.” This payment is listed as “34.13.9” The next entry in the cash book notes that Hamilton paid “6. 8.7” for the “ballance of Alsop Hunt and James Hunts account for leather Breeches supplied the company ⅌ Rects [per receipts].” [x]

Following is a depiction of Hamilton’s company uniform!

First up is an illustration of an officer (not Hamilton himself) as seen in An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Uniforms of The American War For Independence, 1775-1783 Smith, Digby; Kiley, Kevin F. pg. 121. By the list of supplies purchased above, this would seem to be the most accurate depiction of the general uniform.

Here is another done in 1923 of Alexander Hamilton in his company's uniform:

March 14th: The New York Provincial Congress orders that "Alexander Hamilton be, and he is hereby, appointed captain of the Provincial company of artillery of this Colony.” Alongside Hamilton, James Gilleland (alternatively spelt Gilliland) is appointed to be his 2nd Lieutenant. “As soon as his company was raised, he proceeded with indefatigable pains, to perfect it in every branch of discipline and duty,” Robert Troup recalled in a later letter to John Mason in 1820 (reprinted alongside Mulligan’s recollections in the William & Mary Quarterly), “and it was not long before it was esteemed the most beautiful model of discipline in the whole army.”

March 24th: Within a pay roll from "first March to first April, 1776," Hamilton records that Lewis Ryan, a matross (who assisted the gunners in loading, firing, and spounging the cannons), was dismissed from the company "For being subject to Fits." Also on this pay roll, it is seen that John Bane is listed as Hamilton's 3rd Lieutenant, and James Henry, Thomas Thompson, and Samuel Smith as sergeants.

March 26th: William I. Gilbert, also a matross, is dismissed from the company, "for misbehavior." [x]

March-April: At some point between March and April of 1776, Alexander Hamilton drops out of King's College to put full focus towards his new duties as an artillery captain. King's College would shut down in April as the war came to New York City, and the building would be occupied by American (and later British) forces. Hamilton would never go back to complete his college degree.

April 2nd: The Provincial Congress having decided that the company who were assigned to guard the colony's records had "been found a very expensive Colony charge" orders that Hamilton "be directed to place and keep a proper guard of his company at the Records, until further order..." (Also see the PAH) According to historian Willard Sterne Randall in an article for the Smithsonian Magazine, the records were to be "shipped by wagon from New York’s City Hall to the abandoned Greenwich Village estate of Loyalist William Bayard." [x]

Not-so-fun fact: it is likely that this is the same Bayard estate that Alexander Hamilton would spend his dying hours inside after his duel with Aaron Burr 28 years later.

April 4th: Hamilton writes a letter to Colonel Alexander McDougall acknowledging the payment of "one hundred and seventy two pounds, three shillings and five pence half penny, for the pay of the Commissioned, Non commissioned officers and privates of [his] company to the first instant, for which [he has] given three other receipts." This letter is also printed at the bottom of Hamilton’s pay roll for March and April of 1776.

April 10th: In a letter of the previous day [April 9th] from General Israel Putnam addressed to the Chairmen of the New York Committee of Safety, which was read aloud during the meeting of the New York Provincial Congress, Putnam informs the Congress that he desires another company to keep guard of the colony records, stating that "Capt. H. G. Livingston's company of fusileers will relieve the company of artillery to-morrow morning [April 10th, this date], ten o'clock." Thusly, Hamilton was relieved of this duty.

April 20th: A table appears in the George Washington Papers within the Library of Congress titled "A Return of the Company of Artillery commanded by Alexander Hamilton April 20th, 1776." The Library of Congress itself lists this manuscript as an "Artillery Company Report." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors calendar this table and describe the return as "in the form of a table showing the number of each rank present and fit for duty, sick, on furlough, on command duty, or taken as prisoner." [x]

The table, as seen above, shows that by this time, Hamilton’s company consisted of 69 men. Reading down the table of returns, it is seen that three matrosses are marked as ���Sick [and] Present” and one matross is noted to be “Sick [and] absent,” and two bombarders and one gunner are marked as being “On Command [duty].” Most interestingly, in the row marked “Prisoners,” there are three sergeants, one corporal, and one matross listed.

Also on April 20th: Alexander Hamilton appears in General George Washington's General Orders of this date for the first time. Washington wrote that sergeants James Henry and Samuel Smith, Corporal John McKenny, and Richard Taylor (who was a matross) were "tried at a late General Court Martial whereof Col. stark was President for “Mutiny"...." The Court found both Henry and McKenny guilty, and sentenced both men to be lowered in rank, with Henry losing a month's pay, and McKenny being imprisoned for two weeks. As for Smith and Taylor, they were simply sentenced for disobedience, but were to be "reprimanded by the Captain, at the head of the company." Washington approved of the Court's decision, but further ordered that James Henry and John McKenny "be stripped and discharged [from] the Company, and [that] the sentence of the Court martial, upon serjt Smith, and Richd Taylor, to be executed to morrow morning at Guard mounting." As these numbers nearly line up with the return table shown above, it is clear that the table was written in reference to these events. What actions these men took in committing their "Mutiny" are unclear.

May 8th: In Washington's General Orders of this date, another of Hamilton's men, John Reling, is written to have been court martialed "for “Desertion,” [and] is found guilty of breaking from his confinement, and sentenced to be confin’d for six-days, upon bread and water." Washington approved of the Court's decision.

May 10th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington recorded that "Joseph Child of the New-York Train of Artillery" was "tried at a late General Court Martial whereof Col. Huntington was President for “defrauding Christopher Stetson of a dollar, also for drinking Damnation to all Whigs, and Sons of Liberty, and for profane cursing and swearing”...." The Court found Child guilty of these charges, and "do sentence him to be drum’d out of the army." Although Hamilton was not explicitly mentioned, his company was commonly referred to as the "New York Train of Artillery" and Joseph Child is shown to have enlisted in Hamilton's company on March 28th. [x]

May 11th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington orders that "The Regiment and Company of Artillery, to be quarter’d in the Barracks of the upper and lower Batteries, and in the Barracks near the Laboratory" which would of course include Alexander Hamilton's company. and that "As soon as the Guns are placed in the Batteries to which they are appointed, the Colonel of Artillery, will detach the proper number of officers and men, to manage them...." Where exactly Hamilton and his men were staying prior to this is unclear.

May 15th: Hamilton appears by name once more in General George Washington’s General Orders of this date. Hamilton’s artillery company is ordered “to be mustered [for a parade/demonstration] at Ten o’Clock, next Sunday morning, upon the Common, near the Laboratory.”

May 16th: In General Washington's General Orders of this date, it is written that "Uriah Chamberlain of Capt. Hamilton’s Company of Artillery," was recently court martialed, "whereof Colonel Huntington was president for “Desertion”—The Court find the prisoner guilty of the charge, and do sentence him to receive Thirty nine Lashes, on the bare back, for said offence." Washington approved of this sentence, and orders "it to be put in execution, on Saturday morning next, at guard mounting."

May 18th: Presumably, Hamilton carried out the orders given by Washington in his General Orders of May 16th, and on the morning of this date oversaw the lashing of Uriah Chamberlain at "the guard mounting."

May 19th: At 10 a.m., Hamilton and his men gathered at the Common (a large green space within the city which is now City Hall Park) to parade before Washington and some of his generals as had been ordered in Washington's General Orders of May 15th. In his Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene (on page 57), William Johnson in 1822 recounted that, (presumably around or about this event):

It was soon after Greene's arrival on Long Island, and during his command at that post, that he became acquainted with the late General Hamilton, afterwards so conspicuous in the councils of this country. It was his custom when summoned to attend the commander in chief, to walk, when accompanied by one or more of his aids, from the ferry landing to head-quarters. On one of these occasions, when passing by the place then called the park, now enclosed by the railing of the City-Hall, and which was then the parade ground of the militia corps, Hamilton was observed disciplining a juvenile corps of artillerist, who, like himself, aspired to future usefulness. Greene knew not who he was, but his attention was riveted by the vivacity of his motion, the ardour of his countenance, and not less by the proficiency and precision of movement of his little corps. Halt behind the crowd until an interval of rest afforded an opportunity, an aid was dispatched to Hamilton with a compliment from General Greene upon the proficiency of his corps and the military manner of their commander, with a request to favor him with his company to dinner on a specified day. Those who are acquainted with the ardent character and grateful feelings of Hamilton will judge how this message was received. The attention never forgotten, and not many years elapsed before an opportunity occurred and was joyfully embraced by Hamilton of exhibiting his gratitude and esteem for the man whose discerning eye had at so early a period done justice to his talents and pretensions. Greene soon made an opportunity of introducing his young acquaintance to the commander in chief, and from his first introduction Washington "marked him as his own."

Michael E. Newton notes that William Johnson never produced a citation for this tale, and goes on to give a brief historiography of it (Johnson being the first to write about this). While it is possible that General Greene could have sent an aide-de-camp to give his compliments to Hamilton after seeing his parade drill, there is no certain evidence to suggest that Greene introduced Hamilton to George Washington. Newton also notes that "John C. Hamilton failed to endorse any part of the story." (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 150-152).

May 26th: Alexander Hamilton writes a letter to the New York Provincial Congress concerning the pay of his men. Hamilton points out that his men are not being paid as they should be in accordance to rules past, and states that “They do the same duty with the other companies and think themselves entitled to the same pay. They have been already comparing accounts and many marks of discontent have lately appeared on this score.” Hamilton further points out that another company, led by Captain Sebastian Bauman, were being paid accordingly and were able to more easily recruit men.

Also on May 26th: the Provencal Congress approved Hamilton’s request, resolving that Hamilton and his men would receive the same pay as the Continental artillery, and that for every man he recruited, Hamilton would receive 10 shillings. [x]

May 31st: Captain Hamilton receives orders from the Provincial Congress that he, “or any or either of his officers," are "authorized to go on board any ship or vessel in this harbour, and take with them such guard as may be necessary, and that they make strict search for any men who may have deserted from Captain Hamilton’s company.” These orders were given after "one member informed the Congress that some of Captain Hamilton’s company of artillery have deserted, and that he has some reasons to suspect that they are on board of the Continental ship, or vessel, in this harbour, under the command of Capt. Kennedy." Unfortunately, I as of writing this have been unable to find any solid information on this Captain Kennedy to better identify him, or his vessel.

June 8th: The New York Provincial Congress orders that Hamilton "furnish such a guard as may be necessary to guard the Provincial gunpowder" and that if Hamilton "should stand in need of any tents for that purpose" Colonel Curtenius would provide them. It is unknown when Hamilton's company was relieved of this duty, however three weeks later, on June 30th, the Provincial Congress "Ordered, That all the lead, powder, and other military stores" within the "city of New York be forthwith removed from thence to White Plains." [x]

Also on June 8th: the Provincial Congress further orders that "Capt. Hamilton furnish daily six of his best cartridge makers to work and assist" at the "store or elaboratory [sic] under the care of Mr. Norwood, the Commissary."

June 10th: Besides the portion of Hamilton's company that was still guarding the colony's gunpowder, it is seen in a report by Henry Knox (reprinted in Force, Peter. American Archives, 4th Series, vol. VI, pg. 920) that another portion of the company was stationed at Fort George near the Battery, in sole command of four 32-pound cannons, and another two 12-pound cannons. Simultaneously, another portion of Hamilton's company was stationed just below at the Grand Battery, where the companies of Captain Pierce, Captain Burbeck, and part of Captain Bauman's manned an assortment of cannons and mortars.

June 17th: The New York Provincial Congress resolves that "Capt. Hamilton's company of artillery be considered so many and a part of the quota of militia to be raised for furnished by the city or county of New-York."

June 29th: A return table, reprinted in Force, Peter's American Archives, 4th Series, vol. VI, pg. 1122 showcases that Alexander Hamilton's company has risen to 99 men. Eight of Hamilton's men--one bombarder, two gunners, one drummer, and four matrosses--are marked as being "Sick [but] present." One sergeant is marked as "Sick [and] absent" and two matrosses are marked as "Prisoners."

July 4th: In Philadelphia, the Continental Congress approves the Declaration of Independence.

July 9th: The Continental Army gathers in the New York City Common to hear the Declaration read aloud from City Hall. In all the excitement, a group of soldiers and the Sons of Liberty (who included Hercules Mulligan) rushed down to the Bowling Green to tear down an equestrian statue of King George III, which they would melt into musket balls. For a history of the statue, see this article from the Journal of the American Revolution.

Also on July 9th: the New York Provincial Congress approve the Declaration of Independence, and hereafter refer to themselves as the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York. [x]

July 12th: Multiple accounts record that the British ships Phoenix and Rose are sailing up the Hudson River, near the Battery, when as Hercules Mulligan stated in a later recollection, "Capt. Hamilton went on the Battery with his Company and his piece of artillery and commenced a Brisk fire upon the Phoenix and Rose then passing up the river. When his Cannon burst and killed two of his men who I distinctly recollect were buried in the Bowling Green." Mulligan's number of deaths may be incorrect however. Isac Bangs records in his journal that, "by the carelessness of our own Artilery Men Six Men were killed with our own Cannon, & several others very badly wounded." Bangs noted further that "It is said that several of the Company out of which they were killed were drunk, & neglected to Spunge, Worm, & stop the Vent, and the Cartridges took fire while they were raming them down." In a letter to his wife, General Henry Knox wrote that "We had a loud cannonade, but could not stop [the Phoenix and Rose], though I believe we damaged them much. They kept over on the Jersey side too far from our batteries. I was so unfortunate as to lose six men by accidents, and a number wounded." Matching up with Bangs and Knox, in his own journal, Lieutenant Solomon Nash records that, "we had six men cilled [sic: killed], three wound By our Cannons which went off Exedently [sic: accidentally]...." A William Douglass of Connecticut wrote to his wife on July 20th that they suffered "the loss of 4 men in loading [the] Cannon." (as seen in Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 142; Newton cites Henry P. Johnston's The Campaigns of 1776 in and around New York and Brooklyn, vol. 2, pg. 67). As these accounts cobberrate each other, it is clear that at least six men were killed. Whether these were all due to Hamilton's cannon exploding is unclear, but is a possibility. Hamilton of course was not punished for this, but that is besides the point.

One of the men injured by the explosion of the cannon was William Douglass, a matross in Hamilton's company (not to be confused with the William Douglass quoted above from Connecticut). According to a later certificate written by Hamilton on September 14th, Douglass "faithfully served as a matross in my company till he lost his arm by an unfortunate accident, while engaged in firing at some of the enemy’s ships." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors date Douglass' injury to June 12th, but it is clear that this occurred on July 12th due to the description Hamilton provides.

July 26th: Hamilton writes a letter to the Convention of the Representatives (who he mistakenly addresses as the "The Honoruable The Provincial Congress") concerning the amount of provisions for his company. He explains that there is a difference in the supply of rations between what the Continental Army and Provisional Army and his company are receiving. He writes that "it seems Mr. Curtenius can not afford to supply us with more than his contract stipulates, which by comparison, you will perceive is considerably less than the forementioned rate. My men, you are sensible, are by their articles, entitled to the same subsistence with the Continental troops; and it would be to them an insupportable discrimination, as well as a breach of the terms of their enlistment, to give them almost a third less provisions than the whole army besides receives." Hamilton requests that the Convention "readily put this matter upon a proper footing." He also notes that previously his men had been receiving their full pay, however under an assumption by Peter Curtenius that he "should have a farther consideration for the extraordinary supply."

July 31st: The Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York read Hamilton's letter of July 26th at their meeting, and order that "as Capt. Hamilton's company was formally made a part of General Scott's brigade, that they be henceforth supplied provisions as part of that Brigade."

A Note On Captain Hamilton’s August Pay Book:

Starting in August of 1776, Hamilton began to keep another pay book. It is evident by Thomas Thompson being marked as the 3rd lieutenant that this was started around August 15th. The cover is below:

For unknown reasons, the editors of The Papers of Alexander Hamilton only included one section of the artillery pay book in their transcriptions, being a dozen or so pages of notes Hamilton wrote presumably after concluding his time as a captain on some books he was reading. The first section of the book (being the first 117 image scans per the Library of Congress) consists of payments made to and by Hamilton’s men, each receiving his own page spread, with the first few pages being a list of all men in the company as of August 1776, organized by surname alphabetically. The last section of the pay book (Image scans 181 to 185) consists of weekly company return tables starting in October of 1776.

As these sections are not transcribed, I will be including the image scans when necessary for full transparency, in case I have read something incorrectly. Now, back to the timeline....

August 3rd: John Davis and James Lilly desert from Hamilton's company. Hamilton puts out an advertisement that would reward anyone who could either "bring them to Captain Hamilton's Quarters" or "give Information that they may be apprehended." It is presumed that Hamilton wrote this notice himself (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 147-148; for the notice, Newton cites The New-York Gazette; and the weekly Mercury, August 5, 12, and September 2nd, 1776 issues).

August 9th: The Convention of the Representatives resolve that "The company of artillery formally raised by Capt. Hamilton" is "considered as a part of the number ordered to be raised by the Continental Congress from the militia of this State, and therefore" Hamilton's company "hereby is incorporated into Genl. Scott's brigade." Here, Hamilton would be reunited with his old friend, Nicholas Fish, who had recently been appointed as John Scott's brigade major. [x]

August 12th: Captain Hamilton writes a letter to the Convention of the Representatives concerning a vacancy in his company. Hamilton explains that this is due to “the promotion of Lieutenant Johnson to a captaincy in one of the row-gallies, (which command, however, he has since resigned, for a very particular reason.).” He requests that his first sergeant, Thomas Thompson, be promoted as he “has discharged his duty in his present station with uncommon fidelity, assiduity and expertness. He is a very good disciplinarian, possesses the advantage of having seen a good deal of service in Germany; has a tolerable share of common sense, and is well calculated not to disgrace the rank of an officer and gentleman.…” Hamilton also requested that lieutenants James Gilleland and John Bean be moved up in rank to fill the missing spots.

August 14th: The Convention of the Representatives, upon receiving Hamilton’s letter of August 12th, order that Colonel Peter R. Livingston, "call upon [meet with] Capt. Hamilton, and inquire into this matter and report back to the House."

August 15th: Colonel Peter R. Livingston reports back to the Convention of the Representatives that, "the facts stated by Capt. Hamilton are correct..." The Convention thus resolves that "Thomas Thompson be promoted to the rank of a lieutenant in the said company; and that this Convention will exert themselves in promoting, from time to time, such privates and non-commissioned officers in the service of this State, as shall distinguish themselves...." The Convention further orders that these resolutions be published in the newspapers.

August ???: According to Hercules Mulligan in his "Narrative" account, Alexander Hamilton, along with John Mason, "Mr. Rhinelander" and Robert Troup, were at the Mulligan home for dinner. Here, Mulligan writes that, after Rhineland and Troup had "retired from the table" Hamilton and Mason were "lamenting the situation of the army on Long Island and suggesting the best plans for its removal," whereupon Mason and Hamilton decided it would be best to write "an anonymous letter to Genl. Washington pointing out their ideas of the best means to draw off the Army." Mulligan writes that he personally "saw Mr. H [Hamilton] writing the letter & heard it read after it was finished. It was delivered to me to be handed to one of the family of the General and I gave it to Col. Webb [Samuel Blachley Webb] then an aid de Champ [sic: aide-de-camp]...." Mulligan expresses that he had "no doubt he delivered it because my impression at that time was that the mode of drawing off the army which was adopted was nearly the same as that pointed out in the letter." There is no other source to contradict or challenge Hercules Mulligan's first-hand account of this event, however the letter discussed has not been found.

August 24th: Alexander Hamilton helped to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Herman Zedwitz from committing treason. On August 25th, a court martial was held (reprinted in Force, Peter. American Archives, 5th Series, vol. I, pp. 1159-1161) wherein Zedwitz was charged with "holding a treacherous correspondence with, and giving intelligence to, the enemies of the United States." In a written disposition for the trial, Augustus Stein tells the Court that on the previous day [this date, August 24th] Zedwitz had given him a letter with which Stein was directed "to go to Long-Island with [the] letter [addressed] to Governour Tryon...." Stein, however, wrote that he immediately went "to Captain Bowman's house, and broke the letter open and read it. Soon after. Captain Bowman came in, and I told him I had something to communicate to the General. We sent to Captain Hamilton, and he went to the General's, to whom the letter was delivered." By other instances in this court martial record, it is clear that Stein had meant Captain Sebastian Bauman (and to this, Zedwitz's name is also spelled many different times throughout this record), which would indicate that the "Captain Hamilton" mentioned was Alexander Hamilton, Bauman's fellow artillery captain. Bauman was the only captain serving by that name in the army at this time (see Heitman, Francis B. Historical Register of the Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution, pg. 92). It could be possible that Alexander Hamilton personally delivered this letter into Washington's hands and explained the situation, or that he passed it on to one of Washington's staff members.

August 27th: Battle of Long Island — Although Alexander Hamilton was not involved in this battle, for no primary accounts explicitly place him in the middle of this conflict, it is significant to note considering the previous entry on this timeline.

May-August: According to Robert Troup, again in his 1821 letter to John Mason, he had paid Hamilton a visit during the summer of 1776, but did not provide a specific date. Troup noted that, “at night, and in the morning, he [Hamilton] went to prayer in his usual mode. Soon after this visit we were parted by our respective duties in the Army, and we did not meet again before 1779.” This date however, may be inaccurate, for also according to Troup in another letter reprinted later in the William & Mary Quarterly, they had met again while Hamilton was in Albany to negotiate the movement of troops with General Horatio Gates in 1777.

September 7th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington writes that John Davis, a member of Alexander Hamilton's company who had deserted in early August, was recently "tried by a Court Martial whereof Col. Malcom was President, was convicted of “Desertion” and sentenced to receive Thirty-nine lashes." Washington approved of this sentence, and ordered that it be carried out "on the regimental parade, at the usual hour in the morning."

September 8th: In his General Orders of this date, Washington writes that John Little, a member of "Col. Knox’s Regt of Artillery, [and] Capt. Hamilton’s Company," was tried at a recent court martial, and convicted of “Abusing Adjt Henly, and striking him”—ordered to receive Thirty-nine lashes...." Washington approved of this sentence, and ordered it, along with the other court martial sentences noted in these orders, to be "put in execution at the usual time & place."

September 14th: Hamilton writes a certificate to the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York regarding his matross, William Douglass, who “lost his arm by an unfortunate accident, while engaged in firing at some of the enemy’s ships” on July 12th. Hamilton recommends that a recent resolve of the Continental Congress be heeded regarding “all persons disabled in the service of the United States.”

September 15th: On this date, the Continental Army evacuated New York City for Harlem Heights as the British sought control of the city. According to the Memoirs of Aaron Burr, vol. 1, General Sullivan’s brigade had been left in the city due to miscommunication, and were “conducted by General Knox to a small fort” which was Fort Bunker Hill. Burr, then a Major and aide-de-camp to General Israel Putman, was directed with the assistance of a few dragoons “to pick up the stragglers,” inside the fort. Being that Knox was in command of the Army’s artillery, Hamilton’s company would be among those still at the fort. Major Burr and General Knox then had a brief debate (Knox wishing to continue the fight whereas Burr wished to help the brigade retreat to safety). Aaron Burr at last remarked that Fort Bunker Hill “was not bomb-proof; that it was destitute of water; and that he could take it with a single howitzer; and then, addressing himself to the men, said, that if they remained there, one half of them would be killed or wounded, and the other half hung, like dogs, before night; but, if they would place themselves under his command, he would conduct them in safety to Harlem.” (See pages 100-101). Corroborating this account are multiple certificates and letters from eyewitnesses of this event reprinted in the Memiors on pages 101-106. In a letter, Nathaniel Judson recounted that, “I was near Colonel Burr when he had the dispute with General Knox, who said it was madness to think of retreating, as we should meet the whole British army. Colonel Burr did not address himself to the men, but to the officers, who had most of them gathered around to hear what passed, as we considered ourselves as lost.” Judson also remarked that during the retreat to Harlem Heights, the brigade had “several brushes with small parties of the enemy. Colonel Burr was foremost and most active where there was danger, and his con-duct, without considering his extreme youth, was afterwards a constant subject of praise, and admiration, and gratitude.”

Alexander Hamilton himself recounted in later testimony for Major General Benedict Arnold’s court martial of 1779 that he “was among the last of our army that left the city; the enemy was then on our right flank, between us and the main body of our army.” Hamilton also recalled that upon passing the home of a Mr. Seagrove, the man left the group he was entertaining and “came up to me with strong appearances of anxiety in his looks, informed me that the enemy had landed at Harlaam, and were pushing across the island, advised us to keep as much to the left as possible, to avoid being intercepted….” Hercules Mulligan also recounted in his “Narrative” printed in the William & Mary Quarterly that Hamilton had “brought up the rear of our army,” and unfortunately lost “his baggage and one of his Cannon which broke down.” [x]

September ???: As can be seen in Hamilton's August 1776-May 1777 pay book, while stationed in Harlem Heights (often abbreviated as "HH" in the pay book), nearly all of Hamilton's men received some sort of item, whether this be shoes, cash payments, or other articles.

October 4th: A return table for this date appears in Alexander Hamilton’s pay book, in the back. These return tables are not included in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton for unknown reasons.

The table, as seen above, provides us a snapshot of Hamilton’s company at this time, as no other information survives about the company during October. His company totaled to 49 men. Going down the table, two matrosses were “Sick [and] Present,” one bombarder, four gunners, and six matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent,” and two matrosses were marked as “On Furlough.” Interestingly, another two matrosses were marked as having deserted, and two matrosses were marked as “Prisoners.”

October 11th: In Hamilton’s pay book, below the table of October 4th, another weekly return table appears with this date marked.

The return table, as seen above, again records that Hamilton’s company consisted of 49 men. Reading down the table, two matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] Present,” one bombarder and four matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent,” and one captain-lieutenant [being James Moore], one sergeant, and two matrosses were marked as being “On Furlough.”

To the right of the date header, in place of the usual list of positions, there is a note inside the box. The note likely reads:

Drivers. 2_ Drafts_l?] 9_ 4 of which went over in order to get pay & Cloaths & was detained in their Regt [regiment]

Drafts were men who were drawn away from their regular unit to aid another, and it’s clear that Hamilton had many men drafted into his company. This note tells us that four of these men were sent by Hamilton to gather clothing for the company, and it is likely that they had to return to their original regiment before they could return the clothing. This, at least, makes the most sense (a huge thank you to @my-deer-friend and everyone else who helped me decipher this)!! In the bottom left-hand corner of the page, another note is present, however I am unable to decipher what it reads. If anyone is able, feel free to take a shot!

October 25th: Another weekly returns table appears in Hamilton’s company pay book. Once more, this table of returns was not transcribed within The Papers of Alexander Hamilton.

The table, as seen above, shows that Hamilton’s company still consisted of 49 men. Reading down the table, it can be seen that one matross and one drummer/fifer were “Sick [but] present,” and one sergeant, two bombarders, one gunner, and four matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent.” Interestingly, one matross was noted as being “Absent without care”. Two matrosses were listed as “Prisoners” and again two matrosses were listed as having “Deserted.”

Underneath the table, a note is written for which I am only able to make out part. It is clear that two men from another captain’s company were drafted by Hamilton for his needs.

October 28th: Battle of White Plains — Like with Long Island, there is no primary evidence to explicitly place Alexander Hamilton, his men, or his artillery as being involved in this battle, contrary to popular belief. See this quartet of articles by Harry Schenawolf from the Revolutionary War Journal.

November 6th: Captain Hamilton wrote another certificate to the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York regarding his matross, William Douglass, who was injured during the attacks on July 12th. This certificate is nearly identical to the one of September 14th, and again Hamilton writes that Douglass is “intitled to the provision made by a late resolve of the Continental Congress, for those disabled in defence of American liberty.”

November 22nd: As can be seen in Hamilton's pay book, all of his men regardless of rank received payments of cash, and some men articles, on this date.

December 1st: Stationed near New Brunswick, New Jersey, General Washington wrote in a report to the President of Congress, that the British had formed along the Heights, opposite New Bunswick on the Raritan River, and notably that, "We had a smart canonade whilst we were parading our Men...." Alexander Hamilton's company pay book placed he and his men at New Brunswick in around this time (see image scans 25, 28, 34, and others) making it likely that Hamilton had been present and helped prevent the British from crossing the river while the Continental Army was still on the opposite side. In his Memoirs of My Own Life, vol. 1, James Wilkinson recorded that:

After two days halt at Newark, Lord Cornwallis on the 30th November advanced upon Brunswick, and ar- Dec. 1. rived the next evening on the opposite bank of the Rariton, which is fordable at low water. A spirited cannonade ensued across the river, in which our battery was served by Captain Alexander Hamilton,* but the effects on eitlierside, as is usual in contests between field batteries only, were inconsiderable. Genei'al Washington made a shew of resistance, but after night fall decamped...

Though Wilkinson was not present at this event, John C. Hamilton similarly recorded in both his Life of Alexander Hamilton [x] and History of the Republic [x] that Hamilton was part of the artillery firing the cannonade during this event. Though there is no firsthand account of Hamilton's presence here, it is highly likely that he and his company was involved in holding off the British so that the Continental Army could retreat.

December 4th?: Either on this date, or close to it, Alexander Hamilton’s second lieutenant, James Gilleland, left the company by resigning his commission to General Washington on account of “domestic inconveniences, and other motives,” according to a later letter Hamilton wrote on March 6th of 1777.

December 5th: Another return table appears in the George Washington Papers within the Library of Congress. This table is headed, "Return of the States of part of two Companeys of artilery Commanded by Col Henery Knox & Capt Drury & Capt Lt Moores of Capt Hamiltons Com." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors calendar this table, and note that Hamilton's "company had been assigned at first to General John Scott’s brigade but was soon transferred to the command of Colonel Henry Knox." They also note that the table "is in the writing of and signed by Jotham Drury...." [x]

The table, as seen above, notes part of the "Troop Strength" (as the Library of Congress notes) of Captain Jotham Drury and Captain Alexander Hamilton's men. As regards Hamilton's company, the portion that was recorded here amounted to 33 men.

December 19th: Within his Warrent Book No. 2, General George Washington wrote on this date a payment “To Capn Alexr Hamilton” for himself and his company of artillery, “from 1st Sepr to 1 Decr—1562 [dollars].” As reprinted within The Papers of Alexander Hamilton.

December 25th: Within Bucks County, Pennsylvania, hours before the famous Christmas Day crossing of the Delaware River by Washington and the Continental Army, Captain-Lieutenant James Moore passed away from a "short but excruciating fit of illness..." as Hamilton would later recount in a letter of March 6th, 1777. According to Washington Crossing Historic Park, Moore has been the only identified veteran to have been buried on the grounds during the winter encampment. His original headstone read: "To the Memory of Cap. James Moore of the New York Artillery Son of Benjamin & Cornelia Moore of New York He died Decm. the 25th A.D. 1776 Aged 24 Years & Eight Months." [x] In his aforementioned letter, Alexander Hamilton remarked that Moore was "a promising officer, and who did credit to the state he belonged to...." As Hamilton and Moore spent the majority of their time physically together (and therefore leaving no reason for there to be surviving correspondence between the two), there is no clear idea of what their working relationship may have looked like.

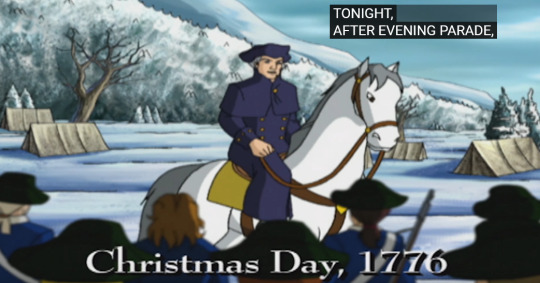

December 26th: Battle of Trenton — Alexander Hamilton is believed to have fought in he battle with his two six-pound cannons, having marched at the head of General Nathanael Greene's column and being placed at the end of King Street at the highest point in the town. Michael E. Newton does note however that there is no direct, explicit evidence placing Hamilton at the battle, but with the knowledge of eighteen cannons being present as ordered by George Washington in his General Orders of December 25th, it is highly likely the above was the case (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 179-180; Newton cites a number of sources for circumstantial evidence: William Stryker's The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, Jac Weller's "Guns of Destiny: Field Artillery In the Trenton-Princeton Campaign" [Military Affairs, vol. 20, no. 1], and works by Broadus Mitchell).

December ???: Within Hamilton’s pay book, a note appears for December on the page dedicated to Uriah Crawford, a matross in his company. See a close up of the image scan below.

The note likely reads:

To Cash [per] for attendance during sickness [ampersand?] funeral expenses —

This note would thus indicate that Crawford likely passed away sometime during the month, and a funeral was held. That Hamilton paid the expenses for the funeral is quite a telling note. Crawford was also provided a pair of stockings in December.

Final Months - 1777:

January 2nd: Battle of Assumpink Creek — Near Trenton, the Continental Army positioned itself on one side of the Assumpink Creek to face the approaching British, who sought to cross the bridge into Trenton. In a letter of January 5th to John Hancock, Washington explained that "They attempted to pass Sanpink [sic: Assumpink] Creek, which runs through Trenton at different places, but finding the Fords guarded, halted & kindled their Fires—We were drawn up on the other side of the Creek. In this situation we remained till dark, cannonading the Enemy & receiving the fire of their Field peices [sic: pieces] which did us but little damage." According to James Wilkinson, who was present at this battle, Hamilton and his cannons were present. [x] Corroborating this, Henry Knox wrote in a letter to his wife of January 7th that, "Our army drew up with thirty or forty pieces of artillery in front", and an anonymous eyewitness account which noted that "within sevnty of eighty yards of the bridge, and directly in front of it, and in the road, as many pieces of artillery as could be managed were stationed" to stop the crossing of the British (see Raum, John. History of the City of Trenton, New Jersey, pp. 173-175). Further, another eyewitness account from a letter written by John Haslet reported a similar story (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 181; for Haslet's account, Newton cites Johnston, Henry P. The Campaigns of 1776 around New York and Brooklyn, Vol. 2, pg. 157). This surely would have been a sight to behold.

January 3rd: Battle of Princeton -- Overnight, the Continental Army marched to Princeton, New Jersey with a train of artillery. Once more, Alexander Hamilton was not explicitly mentioned to have been present at the battle, however with 35 artillery pieces attacking the British (see again Henry Knox's letter of January 7th), and the large role these played in the battle, there is little doubt that Hamilton and his men played a part in this crucial victory (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 182). According to legend, one of Hamilton's cannons fired upon Nassau Hall, destroying a painting of King George II. However, this has been disproven by many different scholars and writers, including Newton.

January 20th: In a letter to his aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hansen Harrison, George Washington requests Harrison to “forward the Inclosed to Captn Hamilton….” Unfortunately, the letter Washington intended to be given to Alexander Hamilton has not been found. It is believed by both the editors of Washington and Hamilton’s papers that this letter contained Washington’s request for Hamilton to join his military family.

Also on January 20th: Many of Hamilton’s men received payments of cash on this date. Alongside cash, one man, John Martim, a matross in Hamilton’s company, was paid cash “per [Lieutenant] Thompson” for his “going to the Hospital.” The hospital in particular, and the circumstances surrounding Martim’s stay are unknown. [x]

January 25th: As printed in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, an advertisement appeared in the Pennsylvania Evening Post directly naming Hamilton. Only one sentence, the advertisement alerts Hamilton that he “should hear something to his advantage” by “applying to the printer of this paper….” Presumably this regarded George Washington wishing to make Hamilton his newest aide-de-camp.

January 30th: Alongside cash, a greatcoat, and cash per “Doctor [Chapman?]” and a cash balance due to him, Alexander Hamilton paid his third lieutenant Thomas Thompson for gathering “sundries in Philadelphia” and for his “journey to Camp”. See close up of the image scan below. [x]

Several other later pages in the pay book indicate that Hamilton and his men were in Philadelphia at some point in January and February. It is thus plausible that Hamilton went to see the printer of the Pennsylvania Evening Post and it may be possible that Lieutenant Thompson had accompanied him and have had picked up his items while in the city, however whether or not Hamilton actually made that journey, and Thompson’s involvement are my speculation only. It is also entirely possible that Thompson's "journey to Camp" was in reference to seeing the doctor, and had picked up the "sundries" then.

March 1st: At Morristown, New Jersey, in his General Orders of this date, George Washington announces and appoints Alexander Hamilton “Aide-De-Camp to the Commander in Chief,” and wrote that Hamilton was “to be respected and obeyed as such.”

March 6th: Alexander Hamilton writes a letter to the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York regarding his artillery company for the last time. Hamilton explains a delay in writing due to having only “recently recovered from a long and severe fit of illness.” He goes on to explain the state of the company—that only two officers, lieutenants Thomas Thompson and James Bean, remained with the company and that Lieutenant Johnson "began the enlistment of the Compan⟨y,⟩ contrary to his orders from the convention, for the term of a year, instead of during the war" which, Hamilton explained, "with deaths and desertions; reduces it [the company] at present to the small number of 25 men." Hamilton then requests that Thomas Thompson be raised to Captain-Lieutenant, for Lieutenant Bean, "is so incurably addicted to a certain failing, that I cannot, in justice, give my opinion in favour of his preferment."

Remarkably, the New York Provincial Company of Artillery still survives to this day, and is the longest (and oldest) continually serving regular army unit in the history of the United States. For a deeper history of the company up to the present day, see this article from the American Battlefield Trust. The company are commonly referred to as “Hamilton’s Own” in honor of the young man who raised the company in 1776.

#I put WAY too much effort into this 😭#I really hope this is useful to someone and not just me lol#grace's random ramble#alexander hamilton#amrev#historical alexander hamilton#captain hamilton#amrev fandom#timelines#the new york provincial company of artillery#american history#american revolution#the american revolution#battle of trenton#battle of princeton#ten crucial days#historical timelines#historical research#george washington#continental army#reference#the american icarus#TAI#historical hamilton#aaron burr#hercules mulligan#robert troup#nathanael greene#18th century correspondence#18th century history

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Battle of Trenton day to all who celebrate, please watch this scene from The Crossing.

youtube

#there’ll be a quiz on this in the survey class I’ll teach 15 years from now#battle of Trenton#amanda speaks#said it before and i'll say it again#amrev movie OF ALL TIME.#Youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Feuding Presidents of Westmoreland County, Virginia

Of all the Founding Fathers, it would seem like George Washington and James Monroe would have been the closest comrades. The two men were born just miles apart from one another in Westmoreland County, Virginia. They both were large men physically, not known primarily for their intellect, but instead for their hard work, their courage, and their devotion to the Revolutionary cause. They were the two Presidents who saw the most action during the Revolutionary War and Monroe served bravely under Washington. To top it all off, Washington and Monroe kind of looked like each other, too.

On Christmas Day in 1776, Lieutenant James Monroe was one of those legendary soldiers who famously crossed the frigid Delaware River with General George Washington to engage the British at the Battle of Trenton. Monroe led a charge in that battle to help capture some cannons that were about to be fired upon the Americans and was wounded in the shoulder, a severe injury that would have resulted in him bleeding to death if it weren’t for the fortunate presence of a local doctor in New Jersey. Monroe’s heroism led to a promotion as Captain and he continued serving bravely during the war and was amongst those troops who survived the terrible winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge. It would seem as if none of the Presidents could have established more of a bond than the two Virginians who helped fight in the Revolution. Indeed, General Washington wrote that Monroe “has, in every instance, maintained the reputation of a brave, active, and sensible officer.”

So why did they despise each other? And did James Monroe indirectly help kill George Washington? After the Revolution, Monroe entered politics and supported the national government being formed under George Washington despite the fact that Monroe had voted against the ratification of the Constitution in 1788. As one of Virginia’s first U.S. Senators, Monroe continued his support of Washington, who was now President, but began to fear that too much power was being placed in the hands of the chief executive and found himself opposing Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality. When Washington appointed Monroe as Minister to France in 1794, something snapped. Monroe, like his friend and mentor Thomas Jefferson, loved France. He loved the country itself and, as an American Revolutionary, he found himself in love with the French Revolution. President Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality insisted on American impartiality towards France and the countries that France was at war with at the time – Britain, The Netherlands, Austria, Prussia, and Sardinia. Monroe was vehemently opposed to neutrality because the French were the first and most important allies of the United States during the Revolution. Plus, James Monroe loved France. In fact, Monroe loved France so much that Secretary of State Edmund Randolph was forced to officially reprimand him due to his glowing compliments about France when Monroe presented his credentials in Paris. From there, things continued going downhill between Washington and Monroe. Monroe rescued Thomas Paine – another one of America’s early Revolutionaries — who had been thrown into prison in France for criticizing the execution of Louis XVI. Paine was very sick and believed to be close to death, so after securing his release, Monroe arranged for Paine to stay with him at the American Ministerial residence. Paine recovered and proceeded to brutally attack George Washington verbally for allowing him to rot in prison instead of rescuing him as Monroe did. President Washington felt Monroe should have muzzled Paine, or at least repudiated Paine’s disrespectful language towards Washington.

When the United States signed Jay’s Treaty with Great Britain, easing tensions between the U.S. and it’s former colonial power, Washington expected Monroe to be a good Federalist and support the rather unpopular treaty. Monroe opposed it and refused to speak out in support of the treaty. His silence on Jay’s Treaty was the last straw for Washington. The President was furious and noting that he expected a diplomat who would “promote, not thwart, the neutral policy of the Government” recalled Monroe as Minister and ordered him to return to the United States. When Monroe learned of his recall, he said that Washington was “insane”. Over the next few years, Monroe spent his time at home in Virginia and worked to undermine Washington and criticize the first President. Monroe questioned Washington’s capacity as a leader and felt that he had sold out the French, who had done so much to help the Americans during the Revolutionary War. Washington felt that Monroe was unqualified to critique his Presidency and that Monroe was a hopeless Francophile. In 1797, long before Monroe was considered to be Presidential timber, Washington cautioned, “If Mr. Monroe should ever fill the Chair of Government he may (and it is presumed he would be well enough disposed) let the French Minister frame his speeches”. Washington added, “There is abundant evidence of his being a mere tool in the hands of the French government.” Monroe wasn’t ready for the “Chair of Government” on a national level, but after Washington retired to Mount Vernon and handed the Presidency over to John Adams, Monroe decided to aim for the “Chair of Government” on a state level. In 1799, Monroe campaigned to become Governor of Virginia and as Monroe’s candidacy was promoted by his friends and supporters, 67-year-old George Washington maintained his estate in Virginia in retirement and tried to do whatever he could to prevent Monroe’s rise. If Monroe was going to be Governor of Washington’s beloved Virginia, then it would practically have to happen over Washington’s dead body. Washington wasn’t powerful enough to prevent Virginia’s state legislature from electing Monroe as Governor in December 1799, however. On a cold and snowy day, George Washington learned of his former lieutenant’s victory and took off on horseback to tend to Mount Vernon. When Washington returned to his home, cold and soaking wet, he got into an animated discussion with guests about Monroe’s victory and angrily denounced the newly elected Governor. Washington continued his discussions without removing his wet clothing. Already ill with a cold, Washington’s illness worsened. On December 14, 1799, George Washington said his last words, “Tis well” and died. Monroe continued his public service as Governor of Virginia, a special envoy to France to secure the Louisiana Purchase for Thomas Jefferson, Minister to Great Britain, Governor of Virginia once again, and Secretary of State and Secretary of War under his close friend James Madison. In 1817, it was finally Monroe’s turn to take the “Chair of Government” as Washington had so feared. Supported by Jefferson and Madison, Monroe easily defeated Rufus King and became President, kicking off “The Era of Good Feelings” where Monroe’s popularity was almost unparalleled by any other President and the nation was unified and free of almost any partisan bickering.

In 1820, Monroe ran for re-election and was so enormously popular that no one dared to run against him. In Massachusetts, 85-year-old John Adams -- a stalwart Federalist and George Washington's Vice President -- even supported Monroe. Yet Washington got the last laugh. Running unopposed, Monroe was not only certain of victory, but it looked like he would become the only President besides Washington be elected unanimously by the Electoral College. However, Governor William Plumer of New Hampshire decided to deny Monroe that honor and reserve it for Washington and Washington only. Some stories allege that Plumer did it solely to prevent Monroe from joining Washington as unanimous Electoral College victors and some stories note that Plumer truly disliked President Monroe and voted for John Quincy Adams as a protest. Either way, the records will always show that George Washington was the only President elected unanimously and I think it's pretty clear that Washington would have appreciated that Monroe of all people was prevented from joining him in that exclusive club.

#History#Presidents#George Washington#President Washington#General Washington#James Monroe#President Monroe#Death of George Washington#Virginia#Virginia Presidents#Westmoreland County#1820 Election#American Revolution#Revolutionary War#Crossing the Delaware#Washington Crossing the Delaware#Washington's Crossing of the Delaware#Battle of Trenton#Continental Army#Military History#Presidential Rivals#Politics#Presidential Politics#Presidential Relationships#Presidential Feuds#Federalist Party#Proclamation of Neutrality#France#French Revolution#Thomas Paine

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

At least I now have less stuff going on

LK 119: Along the Delahow?

(pt1)(pt2)(pt3)(pt4)

Who could have known this would happen??? Not me!!!

Man is *gasping* he didn't know the first rule of Colonialland. Those magnificent cheekbones can't save you now!

youtube

She wasn't readyyyyyyyy.

timeout here but why do american conservatives like flags so much. Is it because they're loud and flap about?

"not exactly" girl shut up, you said "Do we have a chance" and "God help us" like a month ago.

Oh fuck you, art department, for making this look cute. I know its probably not supposed to be an S/J moment but I swear to god y'all were torturing us.

oh my god Y'ALL ABOUT TO LOSE ONE IF YOU DON'T GET YOUR FROSTBITTEN MULLETY ASS IN FRONT OF THE FIRE, HUGHES.

Ok but this is kind of cute in a Brothers Being Bros kind of way.

Well he certainly didn't pull you straight, amirite

He just fucken. Leaves. No goodbyes, no verbal cue that he's leaving the convo. Just turns around and walks away. Wow we must be related

You should probably share your intel with the rest of the agency, James.

LOLOLOLOL that kid who leaked US military shit in that forum NEVER watched LK and it shows.

And yet you still haven't answered my question about the kettle corn!

There we go.

Why is he allowed to do this, Retreats Georg wasn't done.

Sarah: "Are you fucking kidding me rn"

He ships it.

Hey now! Baltimore's all right! ...Sort of!

She has a point!

Quit. Gazing. At. Each other. Actually pls continue, its making my inner 11-year-old squeal.

Honestly the battles of Trenton and Princeton have gotta be in Amrev's top ten most Roadrunner/Wiley Coyote moments. A true benny hill vibe.

why the fuck does this 15-year-old-18-year-old have a miniature of George Number 3 and why is it making eyes at her.

Anyway byeee

#liberty's kids#amrev#18th century#Battle of Trenton#tricorn on the cob watches LK and makes inane commentary#tricorn watches

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

HERE’S AN ANGST REVOLUTIONARY WAR FIC FOR YALL ABOUT HOW JERSEY NEARLY DIED-

How Jersey nearly died:

(This took place after the Battle of Trenton)

It was a cold December night when New Jersey decided to take a walk through the dark woods to get to his house (that was for some reason in the middle of f**king nowhere-). He needed to get home to patch up a few wounds that he had received during the Battle of Trenton and get some rest. After about half an hour of walking, he stopped in a clearing when he heard the sound of a twig snapping behind him.

"Is somebody there?" He called out. There was no answer. "Hello?" He called out again, but still no answer. He just shrugged and continued walking. About 10 minutes later, he heard the same sound again.

"Hel-" He started as he turned around, but he stopped talking halfway through when he saw what had been following him this whole time. His heart started racing as he backed up a few steps.

"Hello, my dear son." England said with a sneer that quickly turned into a cruel smile. There he stood (well- not exactly seeing as he was on horseback), the a-hole himself, along with two other British soldiers on horseback, all three of them wielding a rifle and a sword.

"Wha- What do you want?" Jersey asked, trembling slightly due to fear and the fact that it was December at night.

"Now, now I raised you better than that~ As for why I am here, I heard about your little… attack earlier today." England with faux sadness that quickly returned to his usual cruel smile that sent shivers down the spine of the colony in front of him. "I’ve got to say, I’m quite disappointed in you." He hopped down from his horse and snapped his fingers, and then the two guards hopped off their horses as well. The two soldiers ran at Jersey and grabbed him by the arms, and preventing him from being able to escape from them.

The Garden State struggled a bit and tried to escape, but alas he couldn’t. He looked back at his father confused, only for all the color in his face drain when he saw that England had a whip, chain, and bayonet in his hands. He started struggling again as his father walked over to him.

…

…

The next evening:

New York had been instructed to go check up on his brother, seeing as they hadn’t heard from him since the night before. So here he was; riding horseback through a dark creepy forest on a cold December evening. He wrapped his jacket further around himself and shivered a bit. ‘Ugh… whyyyyy…. Wait- what is that?’ York thought to himself as he stumbled upon some random house/cabin. He decided to investigate, thinking that maybe Jersey had decided to just stop there instead of going the entire way to his house in the cold.

He tied his horse to a random nearby tree and walked into the house. He took a look around; it seemed like a cozy little place, and there were even a few lanterns hanging on the walls, though it seemed to be kinda messy and was that… BLOOD ON THE FLOOR-?! This was kinda concerning to York, so he sped up his search. He went through a few different rooms before finding the one Jersey was in. Except he didn’t find him in the way he hoped to have found him…

"JERSEY!"

He ran over to where his brother was, all the color drained from his face. Jersey was laying cold and unconscious on the floor, surrounded by blood. York looked over Jersey’s body a bit carefully and physically cringed at how bruised and bloody he was. There was a puddle of blood under his head and another leaking out from under Jersey’s jacket, which was stained with blood. York reached a hand over to Jersey’s neck to check for a pulse, and was surprised when he found a small pulse and how cold he was. He tried shaking the older to wake him up, which slowly but surely, he did start waking up.

"Y-York…?" Jersey said quietly, immediately coughing and whimpering after.

"Shhh..ur alright… Yea it’s me. What the h*ll happened?" York responded quietly. He moved his hand from Jersey’s shoulder to his knee, but then instantly moving his hand away when the let out a small yelp/cry. He looked over and his jaw dropped when he saw what seemed to be half of his brother’s bayonet shoved in his knee and the other half laying next to him. "Why the f**k do you have half a bayonet shoved in your damn knee?!"

"E-England h-h-happened…." Jersey responded, but his voice was really quiet and cracking due to lack of use and pain.

"HE DID THIS TO YOU?!" York yelled, but lowering his voice when Jersey flinched and raised his arm to cover his face. F**k England… He took off his jacket and draped it over Jersey’s body. He picked up his brother and walked outside to his horse, where he put Jersey in front of where he would be sitting. He untied the horse and mounted it. "Aight Jers. You know this place betta’ than I do, so I’m gonna need yous to tell me who’s land is closest to here, and what direction we have to go."

"P-Penn’s house is c-closest to here i-if we are where I t-think we are…"

"So east?"

"Y-yea…"

"Ok. Try to stay awake and don’t you dare die on me. If yous die, I’m gonna kill ya."

"I-I’ll t-try…" Jersey said with a slight chuckle that quickly turned into a choked whimper. York adjusted the older to be closer to him for warmth and then started to Pennsylvania’s house.

…

When they got there:

York hopped off the horse and gathered Jersey in his arms after tying his horse to a post. He ran to Penn’s shed where he heard his voice and what sounded to be Mass, Delaware, and Virginia. He knocked on the door and was greeted by Penn who let him after taking one look at the bloody beaten colony in his arms.

"Woah what the f(speaks Boston) happened?!" Mass asked/shouted.

"First off, lower ya damn voice. Second, England happened. What it seems like, is England found him, beat the living s(speaks northeast) out of him and left him there in the cold to die." York said, taking the blanket that Virginia offered him and wrapping it around himself and Jersey, whom he was still holding. He let Mass take Jersey from his arms and set him on a mat that Penn had placed on the ground.

"Can yous explain wth happened? Ya don’t hafta to right now if you don’t feel like it, but ya need to tell us at some point." Mass said as he took

"Godd*mn…." Mass muttered under his breath as he looked over his twin’s injuries and removed his jacket. Jersey started to slowly stir awake and blink his eyes open. "Hey dumb**s, good to see ya alive I guess." Mass said, putting a hand on his twin’s head and running a gentle hand through his hair. He managed to get Jersey’s jacket off without hurting him too badly.

"Good to see ya too… w-where am I?" Jersey asked.

"Yer at my house, well- in my shed." Penn said, walking over and kneeling down next to the injured colony opposite of Mass. "It’s honestly a wonder that you’re still alive after what looks like a beating that was meant to kill you."

"Yea even I was surprised." York piped up from the back.

"Can ya tell us what happened? Ya don’t hafta right now, but you need to at some point. And Jesus Christ is that ur rifle shoved in your knee?!" Mass said, shouting a bit when he saw the bayonet in his brother’s leg (PS: it was the blade end of a bayonet).

"Wellllll- half of it at least….?" Jersey said with a face that had "well maybe…?" written all over it.

Mass sighed. "That doesn’t exactly make it better!"

"I know. As for what happened… Well; I was walking home after the battle, and I don’t know how, but E-England found me in the middle of that clearing that we always hang out in along with two redcoats. Next thing I know, the two guards have a hold of me and England has a whip, chain, and his rifle in his hands. After that everything went dark. I woke up in some random house with England standing in front of me with the whip and rifle. And then started beating me w-with it… and the rifle. That continued for a while and the last thing t-that I r-remembered seeing before going unconscious was him jamming my gun in my knee and snapping it in half… I’m gonna guess that some of the bruising was from the chains cuz’ that’s what he used to knock me out before beating whatever bejeezus I had left out of me…"

There was silence throughout the entire room.

"G-guys?" Jersey said, uncomfortable with the deafening silence.

"Ima kill im’."

"Mass no!" Virginia shouted, grabbing Mass by the arm to keep him from leaving.

"Don’t tell me what to do! Look what he did to my brother!! He’s gotta pay!" Mass shouted back as he tried to twist his way out of Virginia’s grasp.

"I understand, and we will get revenge eventually. We are in the middle of what could be the biggest revolution in history after all. But right now, your brother needs you." Virginia said, putting a hand on the smaller’s shoulder.

"Fine…" Mass said, shaking his wrist a bit when Virginia let go. He walked over to his brother started to help patch him up. When he finished with everything else, it was now time to pull the gun out of his brothers knee. He helped his brother sit up against one of the posts in the shed so that Penn could pull out the gun.

"Aight Jersey. This is probably the most painful part of this whole thing, so I’m gonna need you to tell me whether you want me to knock you out or not." Pennsylvania said, putting a hand on Jersey’s good leg.

"I’ll be fine. Please just pull it out so we can get this over with."

"Ok…" Penn said. He put his hand on Jersey’s knee and grabbed the bayonet with the other. With one swift pull he yanked it out, muttering an apology when the other let out a small cry and whimpered. He quickly used a nearby rag to help stop the bleeding, and ten minutes later they had Jersey’s leg wrapped up in a bandage. Around twenty minutes later, they all went to sleep somewhat peacefully. At least, more peacefully than they have in a long time….

#welcome to the statehouse#welcome to the table#wttt massachusetts#wttt new york#wttt new jersey#wttt pennsylvania#wttt delaware#wttt virginia#countryhumans england#Battle of Trenton

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the time we wastin', We could get away...

#bantuotaku#picrew#jersey club#vogue ballroom#doechii#Jt#music#soundcloud#edm#house music#jersey club music#dance music#electronic music#jerseyclub#club music#jerz#jersey dance#new jersey#trenton new jersey#vogue dance#vogue fem#vogue battle#jersey

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You're seriously studying?"

Y/N turned to the sound of the voice and found Clark Kent standing in the doorway of the now empty classroom. He looked like Clark Kent. And he even sounded like Clark Kent, but he wasn't dressed like Clark Kent. The farm boy traded in his jeans and flannel for leather and Armani suits.

"Clark, hey. I'm just studying for the history test tomorrow. I think I've got most of the dates memorized, but I'm still having trouble between the Cold War and the Battle of Trenton." Y/N said as Clark took a seat next to him, glanced at his books, and wrinkled his nose. "That's boring. Let's go do something fun."

"Like what? Have another basketball game with Pete on the courts? Help Chloe rearrange her bedroom again?"

"I was thinking we'd go to a bar. Maybe to a club and find some nice chicks to hang out with."

"Okay, who are you, and what planet are you from? In what universe does Clark Kent want to go clubbing and drinking?" Y/N asked.