#Assam Accord

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Current Affairs - 7 September 2024

1. Assam Accord Context:The Assam government has decided to implement most of the recommendations made by a high-powered committee appointed by the Union Ministry of Home Affairs to enforce Clause 6 of the Assam Accord (1985). What is the Assam Accord?The Assam Accord was signed in 1985 between the Government of India, the Government of Assam, the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), and the All…

View On WordPress

#Africa Urban Forum#Assam Accord#Kerala&039;s Business-Centric Reforms#Law Commission of India#National Exit Test

0 notes

Text

CAA: Issues in the legal challenge to the law

The CAA - 2019 amends India's Citizenship Act of 1955. Explore recently notified rules under the CAA by Ministry of Home Affairs, sparking further debate and scrutiny.

#Citizenship#Citizenship Amendment Act#2019#CAA-2019#Citizenship Act of 1955#India's citizenship policy#Against muslims#religious minorities#citizenship by naturalisation#Inner Line Permit (ILP)#equality#secularism#protest#unrest#Section 6A of The Citizenship Act - 1955#Assam Accord.

0 notes

Text

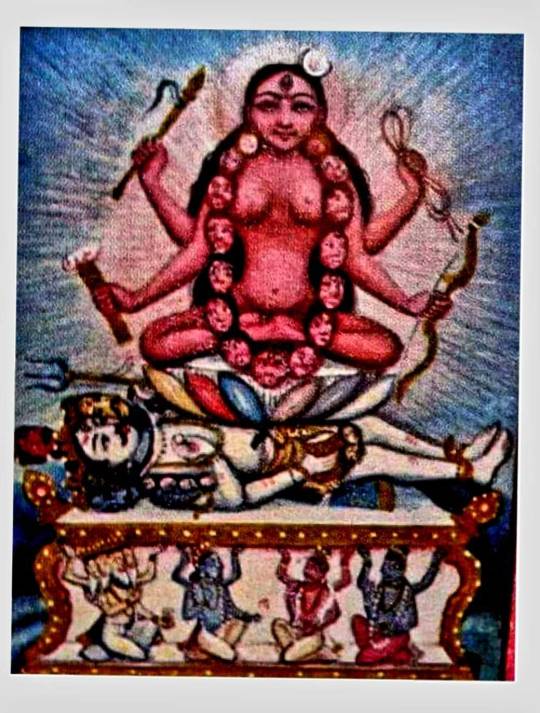

Shiva and Shakti Talon Abraxas Shiva and Shakti - The Divine Union of Consciousness and Energy

Shiva Shakti Story

The legend of the marriage of Shiva and Shakti is one the most important legends related to the festival of Mahashivaratri. The story tells us how Lord Shiva got married for the second time to Shakti, his divine consort. According to legend of Shiva and Shakti, the day Lord Shiva got married to Parvati is celebrated as Shivaratri – the Night of Lord Shiva.

The Legend goes that once Lord Shiva and his wife Sati or Shakti were returning from sage Agastya’s ashram after listening to Ram Katha or story of Ram. On their way through a forest, Shiva saw Lord Rama searching for his wife Sita who had been kidnapped by Ravana, the King of Lanka. Lord Shiva bowed his head in reverence to Lord Rama. Sati was surprised by Lord Shiva’s behavior and inquired why he was paying obeisance to a mere mortal. Shiva informed Sati that Rama was an incarnation of Lord Vishnu. Sati, however, was not satisfied with the reply and Lord asked her to go and verify the truth for herself.

Using her power to change forms, Sati took the form of Sita appeared before Rama. Lord Rama immediately recognized the true identity of the Goddess and asked, “Devi, why are you alone, where′s Shiva?” At this, Sati realized the truth about Lord Ram. But, Sita was like a mother to Lord Shiva and since Sati took the form of Sita her status had changed. From that time, Shiva detached himself from her as a wife. Sati was sad with the change of attitude of Lord Shiva but she stayed on at Mount Kailash, the abode of Lord Shiva.

Later, Sati’s father Daksha organised a yagna, but did not invite Sati or Shiva as he had an altercation with Shiva in the court of Brahma. But, Sati who wanted to attend the Yagna, went there even though Lord Shiva did not appreciate the idea. To her great anguish, Daksha ignored her presence and did not even offer Prasad for Shiva. Sati felt humiliated and was struck with profound grief. She jumped into the yagna fire and immolated herself.

Lord Shiva became extremely furious when he heard the news of Sati’s immolation. Carrying the body of Sati, Shiva began to perform Rudra Tandava or the dance of destruction and wiped out the kingdom of Daksha. Everybody was terrified as Shiva’s Tandava had the power to destroy the entire universe. In order to calm Lord Shiva, Vishnu severed Sati′s body into 12 pieces and threw them on earth. It is said that wherever the pieces of Shakti’s body fell, there emerged a Shakti Peetha, including the Kamaroopa Kamakhya in Assam and the Vindhyavasini in UP.

Lord Shiva who was now alone, undertook rigorous penance and retired to the Himalayas. Shakti took a re-birth as Parvati in the family of God Himalaya. She performed penance to break Shiva’s meditation and win his attention. It is said that Goddess Parvati found it hard to break Shiva’s meditation but through her devotion and the persuasion by sages and devas, Parvati, also known as Uma, was finally able to lure Shiva into marriage and away from asceticism. Their marriage was solemnized a day before Amavasya in the month of Phalgun. This day of union of God Shiva and Shakti is celebrated as Mahashivratri every year.

There is no Shiva without Shakti and yoga is a realization of the unity of all things. That is not to say that everything in tantrik texts is figurative; many describe practices which are said to bring about this realization.

Shiva Shakti Mantras Separator - Divider - Red

Shiva Shakti Panchakshari Mantra

“Om Hrim Namah Shivaya”

Important Shiva Shakti Mantra

(i) “Om Shiva Om Shakti” (ii) “Namah Shiva Namah Shakti” (iii) “Om Sarva Mangal Mangaley Shivay Sarvarth Sadhike

Sharanye Trambhake Gauri Narayani Namostutey”

Therefore, Shakti is the dynamic power of Siva through which he manifests the worlds and their myriad objects and beings. He brings forth the worlds and their beings through his will and his dynamic energy, Shakti.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Overflowing Heart

I will tell you how I made this witch’s token, but you will have to find a way of your own. It is as Grandmother Wren told us,

“Remember always that some portion of magic is yours to wield, and that the world contains many, many truths.”

the recipe:

3/4 oz Kazuki gin

1 1/2 oz. Sake + tea mixture

1 oz. fresh squeezed grapefruit

3/4 oz. Strega

shake over ice, and serve in your finest or favourite tea cup

garnish with dried rose petals

notes:

Sherringham Kazuki gin— a collaboration of one of my favourite distilleries and my favourite local tea shop, Westholme Tea Farm. Made from Japanese cherry blossoms, and locally grown tea leaves with notes of yuzu, grapefruit, and juniper. I first visited Sherringham in a trio of my own, on a day long adventure, visiting a beach someway up the island. Westholme is run by an old coworker of my Aunt’s, and his partner who makes gorgeous pottery. I could not put words to my excitement when I first heard whispers of their collaboration.

Sake + Tea Mixture— I can never fully recreate this just the same. There is magic in that, I think. I have little left. I made it by taking a sprinkling of the following teas from Westholme, and cold steeping them in a mason jar with a large ice cube, topped with sake and a splash of moon bathed witch water.

featuring:

Blossom: (jasmine green, floral), for the cottage’s calendar

Bi Luo Chun: (green, delicate and earthy), for i thought it was grown here, over seven long years (I rolled a nat 1 on my perception check)

Pur-eh: (fermented, earthy), for its mushroominess and it’s connection therin

Dog: (black assam, vanilla and cardamon, from the Chinese Zodic series), the cardamom pod and a few leaves, for our beloved Fox

Witch Water: the witch water used in this potion was bathed in the Friday, October 13th New Moon (a day so witchy I thought for sure the class would be released that day!) in an empty kazuki gin vessel

~

Grapefruit— because it was pink and in season and a citrus I love dearly

Strega— the witch liqueur! According to legend, Giuseppe Alberti was given the recipe for this elixir after saving a witch falling out of the sacred walnut tree, under which witches would convene to dance and perform their rituals.

for the cocktail chapter of the @worldsbeyondpod unofficial cookbook

#worlds beyond number#wbn unofficial cookbook#wbn#the wizard the witch and the wild one#ame the witch#grandmother wren#cw alcohol#styling inspired by artwork featured in the witch class playtest im pretty sure by Tucker Donovan#if this turns into a hit post play go play Wickedness and stream Ghost Quartet#how the fuck do i condense this recipe into a tweet who the fuck knows#feat. all of my magic witch’s tokens and my principles of green witchcraft book in the background#sometimes a witch character and a cocktail inspired by her is something that can be so personal#check out the Neat the Boozecast episode on Strega for all the cool witchy details and history!!!!

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to google translate on the teas from the Dungeon Meshi cafe, Mithrun’s tea is Darjeeling, Marcille is Earl Grey, and Thistle is Assam.

I like that Thistle’s tea is the one with the highest caffeine content, especially with how much the anime is emphasizing the permanent bags under his eyes. I wanna try to find reasons Marcille and Mithrun’s teas fit them, but I am tired and not a tea expert, alas.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

A walk through Bengal's architecture

Bengali architecture has a long and rich history, fusing indigenous elements from the Indian subcontinent with influences from other areas of the world. Present-day Bengal architecture includes the nation of Bangladesh as well as the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, and Assam's Barak Valley. West Bengal’s architecture is an amalgamation of ancient urban architecture, religious architecture, rural vernacular architecture, colonial townhouses and country houses, and modern urban styles. Bengal architecture is the architecture of Wind, Water, and Clay. The Pala Empire (750–1120), which was founded in Bengal and was the final Buddhist imperial force on the Indian subcontinent, saw the apex of ancient Bengali architecture. The majority of donations went to Buddhist stupas, temples, and viharas. Southeast Asian and Tibetan architecture was influenced by Pala architecture. The Grand Vihara of Somapura, which is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was the most well-known structure erected by the Pala rulers.

The Grand Vihara of Somapura

According to historians, the builders of Angkor Wat in Cambodia may have taken inspiration from Somapura. Bengal architecture became known for its use of terracotta due to the scarcity of stone in the area. Clay from the Bengal Delta was used to make bricks.

The temple architecture has distinct features like the rich wall decoration, often known as the terracotta temples, which was one of the remarkable elements of Bengali temple architecture. The double-roofed architecture of thatched huts was replicated by Bengali temples. Square platforms were used to construct the temples. Burnt brick panels with figures in geometric patterns or substantial sculptural compositions served as the temples' adornment.

Dochala style

These served as models for many temples that were built in undivided Bengal. Construction materials used in ancient times included wood and bamboo. Bengal has alluvial soil, so there isn't a lot of stone there. The bricks that were utilized to build the architectural components were made from stone, wood, black salt, and granite. Bengal has two different types of temples: the Rekha type, which is smooth or ridged curvilinear, and the Bhadra form, which has horizontal tiers that gradually get smaller and is made up of the amalaka sila. Mughal architecture, including forts, havelis, gardens, caravanserais, hammams, and fountains, spread throughout the area during the Mughal era in Bengal. Mosques built by the Mughals in Bengal also took on a distinctive regional look. The two major centers of Mughal architecture were Dhaka and Murshidabad. The do-chala roof custom from North India was imitated by the Mughals.

Jorasako thakurbari

The Rasmancha is a heritage building located at Bishnupur, Bankura district, West Bengal.

Influence of the world on Bengal architecture: Although the Indo-Saracenic architectural style predominated in the area, Neo-Classical buildings from Europe were also present, particularly in or close to trading centers. While the majority of country estates had a stately country house, Calcutta, Dacca, Panam, and Chittagong all had extensive 19th and early 20th-century urban architecture that was equivalent to that of London, Sydney, or other British Empire towns. Calcutta experienced the onset of art deco in the 1930s. Indo-Saracenic architecture can be seen in Ahsan Manzil and Curzon Hall in Dhaka, Chittagong Court Building in Chittagong, and Hazarduari Palace in Murshidabad.

Hazarduari Palace in Murshidabad

The Victoria Memorial in Kolkata, designed by Vincent Esch also has Indo-Saracenic features, possibly inspired by the Taj Mahal. Additionally, Kolkata's bungalows, which are being demolished to make way for high-rise structures, have elements of art deco. The 1950s in Chittagong saw a continuation of Art Deco influences. The Bengali modernist movement, spearheaded by Muzharul Islam, was centered in East Pakistan. In the 1960s, many well-known international architects, such as Louis Kahn, Richard Neutra, Stanley Tigerman, Paul Rudolph, Robert Boughey, and Konstantinos Doxiadis, worked in the area.

The Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban

This iconic piece of contemporary Bangladeshi architecture, was created by Louis Kahn. Midsized skyscrapers dominate the cityscapes of contemporary Bengali cities, which are frequently referred to as "concrete jungles." With well-known architects like Rafiq Azam, architecture services play a key role in the urban economies of the area. Overall Bengal architecture was influenced by various contemporaries of their time and continues to evolve.

Gothic architectural style seen in St. Paul's Cathedral in Kolkata.

Zamindar era buildings in ruin.

Belur Math in Howrah

#bengali#bangla#west bengal#bangladesh#tripura#assam#desi#বাংলা#india#architecture#tales#bengal architecture#history#kolkata#international#technology#information#temple#asia#bricks

192 notes

·

View notes

Text

[C]elebrated Victorian travel writer[s] [...] recounted the wilful behaviour of these captive animals [...] [in] a growing corpus of travel writings attempting to capture and relay the sites and scenes of the colony for a wider British audience. [...] [A] range of colonial-era writings - including veterinary texts, memoirs, diaries, fiction and travel writings - [...] [demonstrates] the entangled histories of elephants working in Burma's timber trade [...] [and] trace[s] the development of imperial knowledge about the Asian elephant [...]. The specific configuration of animal agency within the [British imperial] timber trade was a prerequisite factor for the generation of scientific knowledge about elephants. [...]

Teak operations in British Burma during the second half of the nineteenth century had resulted in the decimation of easily accessible forests. Timber firms now had to push their operations into more remote regions of the colony. This necessitated capital-intensive operations involving the purchase of elephants whose labour made possible the logging and transport of this harder-to-reach teak. By the period between 1919 and 1924, elephants represented the largest assets owned by the biggest timber firm operating in the colony [...]. This animal capital, of around three thousand creatures, represented between five and six million rupees annually, the equivalent of roughly a third of the corporation's liabilities. [...]

And these elephants must have been busy. This five-year period saw half a million tons of teak exported out of the colony, the overwhelming majority of which was exported by a handful of large British-owned firms. Their ownership of these beasts of burden gave imperial trading firms a considerable advantage over smaller-scale Burmese outfits and, according to some, over the government of Burma. [...] [T]his expanding and increasingly monopolized animal workforce, mostly employed in camps located in the colony's borders with Siam and Assam, brought unprecedented numbers of Asian elephants into the purview of the colonial scientific gaze. It made colonial Burma an important site for the study of elephants. [...]

---

Within the camps the ‘crush’ was the principal site for exacting discipline. The crush was a wooden structure [...]. Efforts to escape would tire and demoralize the animal, who would have been weakened through deliberate starvation. [...] Supplementing these physical impediments were pharmacological restraints. Opium was used to make elephants more amenable to human direction, particularly to tranquilize elephants for medical interventions. [...] These disciplinary techniques produced knowledge of individual elephants and their characters. Descriptive rolls were maintained providing the physical details of each elephant, giving information on its origins, listing any ailments and recording any misdemeanours, especially episodes of violence.

These documents were held by European supervisors employed by the timber firms to oversee operations. They were used to monitor the Burmese staff too, [...] reinforcing the imperial racial hierarchy in the everyday routines of the camps. The self-serving idea of the white officer protecting the elephants from indigenous cruelty was repeated throughout the early twentieth century. [...]

---

The contingent way that elephants’ bodies changed in the camps mattered for the generation of scientific knowledge. The question of how long elephants could live, and the difficulties of judging an elephant's age, demonstrate this point. [...] The sportsman Fitzwilliam Pollok claimed to have never found the remains of an elephant that had died of natural causes in all of his travels in the colony. This apocryphal but famed longevity stood in contrast to their lifespans in the camps, where elephants over the age of forty were considered elderly [...]. Imperial elephant knowledge was based upon these camp-conditioned bodies [...]. The elephant camps and timber yards were sites that enabled imperial authors to make their studies.

The development of a vaccine against anthrax in elephants illustrates the global significance of the colony's industry in contributing to scientific knowledge. [...] The outcome of these discussions, in 1928, was the employment of a veterinary research officer paid by both the state and the big timber firms. Revealing the wider imperial networks at play in this process, it was determined swiftly after establishing this agreement that the research officer should be a South African. This reflected the status that this settler colony had acquired for expertise in veterinary medicine within the British Empire by the interwar years, particularly for diseases affecting livestock, such as anthrax. [...]

---

Elephants in colonial Burma's teak industry were vital actors, in both senses of the word 'vital'. [...] The agency of imperial corporations to exploit Burma's resources was the effect of relationships between humans and elephants, and other animals. [...] Racial hierarchies and divisions of labour segmented the human workers. [...] Scientific knowledge of animals was not innocent of the structural position of a species in the empire. Certain creatures became available to imperial researchers through the specific relationships engendered by imperial expansion.

---

All text above by: Jonathan Saha. "Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma". BJHS Themes, 2017 (2), 169-189. Published online: 24 April 2017. At: doi dot org slash 10.10016/bjt dot 2017.6. BJHS Themes is a companion journal of the British Journal for the History of Science. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#multispecies#ecologies#tidalectics#geographic imaginaries#indigenous#abolition#ecology#elephants and tigers#british in india#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies#agents of empire

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bak

Also known as Baak or Bák, the Bak is a malevolent creature from Assam folklore. They usually are found near still bodies of water, like ponds or even wells. Unlike many creatures in Assam folklore, the Bak is not delegated to one specific spot, but rather is seen in myths across the state.

The Bak can be deadly, drowning victims and either possessing their bodies, or simply taking their form after death. It will then go on to live with the victim’s family, and try to kill them, too. If you’re afraid of falling victim to a Bak, carrying a torn fishnet is said to scare them off. However, it should be noted that not all Bak are murderous. A more benign Bak will simply possess a living human, or play tricks on them, especially when it comes to children.

One can gain control over a Bak, according to some myths. This is done by stealing a bag they’re said to carry around, containing their powers.

There is one more interesting part about this creature: Baks love fish. So much so, in fact, that even in the current era, some people will take fish from the market or from one house to another with garlic and mirchi (red chilies) to protect it… or even themselves.

#nox hawthorne#artist#writers on tumblr#artists on tumblr#writer#writeblr#writing#art#artwork#bak#cryptids#creature feature friday

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

CAA: Issues in the legal challenge to the law

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of 2019, passed by the Parliament of India, seeks to amend the Citizenship Act of 1955, which provides for the acquisition and determination of Indian citizenship.

Recently, the Ministry of Home Affairs notified the Citizenship Amendment Rules under the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA).

Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019

The CAA amends the Citizenship Act of 1955 to incorporate these provisions, marking a significant change in India's citizenship policy.

Aim:

To give citizenship to the target group of migrants even if they do not have valid travel documents as mandated in The Citizenship Act, 1955.

To address the issue of persecution faced by religious minorities in neighbouring countries and provide them with refuge and citizenship in India.

The act provides a fast-track path to Indian citizenship for religious minorities – Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian – from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

The act has also cut the period of citizenship by naturalisation from 11 years to 5 i.e. eligible immigrants from these countries who entered India before December 31, 2014, can apply for citizenship under the CAA.

Thus, the amendment relaxed the requirements for certain categories of migrants, specifically based on religious lines, originating from three neighbouring countries with Muslim-majority populations.

It is noteworthy that the act does not include Muslims among the eligible religious groups for expedited citizenship.

Criticism: The act violates the secular principles enshrined in the Indian Constitution by discriminating against Muslims and undermining the idea of equal treatment under the law.

Exempted Areas: Certain categories of areas, such as tribal areas in Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Tripura, as well as areas safeguarded by the 'Inner Line' system, were excluded from the scope of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA).

Eligibility

Under the CAA Rules, migrants from these nations are required to demonstrate their country of origin, their religion, the date of their entry into India, and proficiency in an Indian language as prerequisites for applying for Indian citizenship.

Additionally, any document indicating that "either of the parents or grandparents or great-grandparents of the applicant is or had been a citizen of one of the three countries" is also acceptable.

The Rules specify 20 documents that can establish the date of entry into India for admissible proof.

Challenges in the implementation of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA)

Legal Challenges:

Constitutional Validity: The CAA has faced legal challenges regarding its constitutionality, particularly with respect to Articles 14 (equality before law) and 15 (prohibition of discrimination) of the Indian Constitution. By providing preferential treatment to certain religious groups while excluding others, the CAA contravenes these fundamental rights and is seen as discriminatory and contrary to the principle of equality.

Against Secularism: The CAA's focus on granting citizenship based on religious lines, specifically excluding Muslims, is seen as contrary to the secular ethos of the Indian Constitution.

State Opposition: Several states have opposed the implementation of the CAA, leading to potential legal conflicts between the central government and state governments.

Administrative Challenges:

Documentation Verification: Verifying the authenticity of documents proving the eligibility criteria specified in the CAA can pose a significant administrative burden.

Infrastructure: Lack of adequate infrastructure and resources in government departments responsible for processing citizenship applications may hinder the smooth implementation of the CAA.

Social and Political Challenges:

Communal Tensions: The exclusion of Muslims from the purview of the CAA has led to communal tensions and polarization, affecting social harmony in various parts of the country.

Citizenship Criteria: The religious-based criteria for citizenship under the CAA have sparked debates about the secular nature of the Indian state and have been criticized for undermining the principles of equality and inclusivity.

Protest and Opposition: Widespread protests against the CAA have created political challenges for the government, leading to public unrest and opposition from various civil society groups and political parties.

International Relations:

Diplomatic Fallout: The CAA has strained relations with neighbouring countries like Bangladesh, which have expressed concerns about its impact on bilateral relations and regional stability.

Refugee Crisis: The CAA's focus on granting citizenship to persecuted minorities from neighbouring countries could exacerbate refugee crises and strain India's relations with international bodies and humanitarian organizations.

Economic Challenges:

Resource Allocation: Implementing the CAA may require significant financial resources for processing citizenship applications, accommodating new citizens, and addressing potential socio-economic challenges arising from demographic changes.

Section 6A of The Citizenship Act, 1955 and Assam:

Section 6A was incorporated into the Citizenship Act subsequent to the signing of the Assam Accord in 1985. The Accord outlines the criteria for identifying foreigners in the state of Assam, establishing March 24, 1971, as the cutoff date, which contradicts the cutoff date specified in the CAA 2019.

#Citizenship#Citizenship Amendment Act#2019#CAA-2019#Citizenship Act of 1955#India's citizenship policy#Against muslims#religious minorities#citizenship by naturalisation#Inner Line Permit (ILP)#equality#secularism#protest#unrest#Section 6A of The Citizenship Act - 1955#Assam Accord.

0 notes

Text

Shiva and Shakti - The Divine Union of Consciousness and Energy

Shiva Shakti Story

The legend of the marriage of Shiva and Shakti is one the most important legends related to the festival of Mahashivaratri. The story tells us how Lord Shiva got married for the second time to Shakti, his divine consort. According to legend of Shiva and Shakti, the day Lord Shiva got married to Parvati is celebrated as Shivaratri – the Night of Lord Shiva.

The Legend goes that once Lord Shiva and his wife Sati or Shakti were returning from sage Agastya’s ashram after listening to Ram Katha or story of Ram. On their way through a forest, Shiva saw Lord Rama searching for his wife Sita who had been kidnapped by Ravana, the King of Lanka. Lord Shiva bowed his head in reverence to Lord Rama. Sati was surprised by Lord Shiva’s behavior and inquired why he was paying obeisance to a mere mortal. Shiva informed Sati that Rama was an incarnation of Lord Vishnu. Sati, however, was not satisfied with the reply and Lord asked her to go and verify the truth for herself.

Using her power to change forms, Sati took the form of Sita appeared before Rama. Lord Rama immediately recognized the true identity of the Goddess and asked, “Devi, why are you alone, where′s Shiva?” At this, Sati realized the truth about Lord Ram. But, Sita was like a mother to Lord Shiva and since Sati took the form of Sita her status had changed. From that time, Shiva detached himself from her as a wife. Sati was sad with the change of attitude of Lord Shiva but she stayed on at Mount Kailash, the abode of Lord Shiva.

Later, Sati’s father Daksha organised a yagna, but did not invite Sati or Shiva as he had an altercation with Shiva in the court of Brahma. But, Sati who wanted to attend the Yagna, went there even though Lord Shiva did not appreciate the idea. To her great anguish, Daksha ignored her presence and did not even offer Prasad for Shiva. Sati felt humiliated and was struck with profound grief. She jumped into the yagna fire and immolated herself.

Lord Shiva became extremely furious when he heard the news of Sati’s immolation. Carrying the body of Sati, Shiva began to perform Rudra Tandava or the dance of destruction and wiped out the kingdom of Daksha. Everybody was terrified as Shiva’s Tandava had the power to destroy the entire universe. In order to calm Lord Shiva, Vishnu severed Sati′s body into 12 pieces and threw them on earth. It is said that wherever the pieces of Shakti’s body fell, there emerged a Shakti Peetha, including the Kamaroopa Kamakhya in Assam and the Vindhyavasini in UP.

Lord Shiva who was now alone, undertook rigorous penance and retired to the Himalayas. Shakti took a re-birth as Parvati in the family of God Himalaya. She performed penance to break Shiva’s meditation and win his attention. It is said that Goddess Parvati found it hard to break Shiva’s meditation but through her devotion and the persuasion by sages and devas, Parvati, also known as Uma, was finally able to lure Shiva into marriage and away from asceticism. Their marriage was solemnized a day before Amavasya in the month of Phalgun. This day of union of God Shiva and Shakti is celebrated as Mahashivratri every year.

There is no Shiva without Shakti and yoga is a realization of the unity of all things. That is not to say that everything in tantrik texts is figurative; many describe practices which are said to bring about this realization.

Shiva Shakti Mantras

Separator - Divider - Red

Shiva Shakti Panchakshari Mantra

“Om Hrim Namah Shivaya”

Important Shiva Shakti Mantra

(i) “Om Shiva Om Shakti” (ii) “Namah Shiva Namah Shakti” (iii) “Om Sarva Mangal Mangaley Shivay Sarvarth Sadhike Sharanye Trambhake Gauri Narayani Namostutey”

Therefore, Shakti is the dynamic power of Siva through which he manifests the worlds and their myriad objects and beings. He brings forth the worlds and their beings through his will and his dynamic energy, Shakti.

Shiva and Shakti by Talon Abraxas

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Royal Bengal Tiger’s Struggle: Blinded by Conflict and Ignorance”

In November 2024, a heart-breaking incident unfolded in the Indian state of Assam, where a three-year-old Royal Bengal Tigress became the victim of a violent attack by local villagers. The tigress, who had been spotted

in the area before, without incident and was deemed a gentle giant, had ventured into a nearby human settlement. Despite her calm and non-threatening demeanour, the sight of the tigress sent panic and fear through the villagers, leading them to respond with hostility instead of caution.

Rather than trying to manage the situation peacefully, the villagers began throwing stones at the tigress. Frightened and trying to protect herself, the tigress jumped into the pond. However, the villagers continued their onslaught, pelting her with stones even as she sought safety in the water. The attack was so severe, leaving the tigress with catastrophic injuries. The brutal assault caused irreversible damage to the tigress, leaving her permanently blind in both eyes. Furthermore, she also suffered serious bruising to her skull.

Wildlife Aid rescuers quickly responded to the incident, rushing to the scene to provide immediate care and rehabilitation to the injured animal. Despite their best efforts to treat the tigress and offer her comfort, the damage was too severe. The loss of her sight, coupled with the trauma, means she will never be able to return to the wild. Due to her blindness and the physical injuries she sustained during the attack, this majestic creature will now be forced to live the remainder of her life in captivity, a tragic fate for an animal that was once free to roam the forests of Assam.

Current Tiger Numbers

India holds over 75% of the world’s estimated 5,574 adult wild tigers. According to the 2023 tiger estimation by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), released by the Government of India on 29th July 2023, the current tiger population in India is estimated at 3,682 (ranging between a minimum of 3,167 to a maximum of 3,925 tigers). While such numbers show recovery and growth, the numbers are still far too low to be considered as a conservation success story. With each tiger being a victim of human-wildlife conflict, the numbers will continue to decline.

What can be done?

What we urgently need is comprehensive community education and awareness, particularly in rural areas of India that share borders and lands with tigers. The lack of education, generational myths, folklore, superstitions, and the general absence of awareness regarding species conservation are some of the key reasons why human-wildlife conflict persists in many regions of India. These communities, often living in close proximity to tiger habitats, are crucial to breaking the cycle of fear and misunderstanding that fuels conflict. For many rural residents, tigers are viewed through a lens of fear and folklore, where they are depicted as malevolent creatures that attack without reason and venture into human settlements to feast on human flesh. Such perceptions are often passed down through generations, fuelled by superstition and a lack of understanding of the tiger’s true behaviour and its ecological role in the ecosystem. This creates the perfect breeding ground for misinformation that eventually leads to panic and hostility, especially when tigers venture into human settlements, resulting in violent retaliation. By implementing targeted educational programs that focus on dispelling myths and promoting a deeper understanding of tiger behaviour, we can begin to shift this mindset.

Communities need to be informed about the importance of tigers in maintaining ecosystem balance, how these animals typically avoid human contact, and the factors that might lead to a tiger straying into human areas i.e. increasing human populations, encroachment on habitat and depletion of the natural resources that the tiger depends upon. Furthermore, fostering a sense of pride and stewardship for local wildlife can inspire communities to protect rather than harm these animals. As the national animal of India with a commanding name the Royal Bengal Tiger, communities should be taught to view tigers with a sense of pride and respect and not fear and hostility. When villagers understand the ecological, cultural, and economic value of tigers, such as through tiger eco- tourism or their role in maintaining forest health, they are more likely to see these majestic creatures as assets rather than threats.

1. Creating Awareness Programs: Educational programs must be specifically designed for rural communities living in proximity to tiger habitats. These programs should focus on educating villagers about the crucial role tigers play in maintaining ecosystem balance and the importance of conserving these majestic creatures. Much like initiatives implemented by local groups in Ladakh to protect snow leopards, and in Australia to safeguard the Indo-Pacific saltwater crocodile and great white sharks, community awareness and engagement are essential. Such initiatives, which have been successful in these regions, aim to educate the public about how to coexist with wildlife by adopting safe practices, like “Shark Safe” and “Croc Wise.” For tigers, similar programs can promote “Tiger Safe” behaviour, teaching communities how to recognise tiger movements, prevent conflicts, and remain safe when living near tiger habitats. These programs should also educate people about the need to protect the forest ecosystems that sustain tigers, which directly impacts their livelihoods and well-being. Community-based initiatives, such as working with local leaders and involving rural populations in wildlife monitoring and protection efforts, have shown success in reducing conflict in other parts of the world.

2. Utilising Technology for Monitoring and Prevention: Advancements in technology such as AI can greatly assist in mitigating human-wildlife conflict. The use of camera traps, drones, and satellite footage to monitor tiger movements around human settlements can offer real-time alerts to communities that share spaces with tigers. These technologies will allow villagers to take proactive measures by staying alert and avoiding areas where tigers might be present. Applications that alert citizens of a large predator nearby as well as regular monitoring will also help authorities identify potential problem animals that may require relocation or other interventions before they come into contact with humans. Funding should be provided to wildlife authorities and NGOs to impart the knowledge and tools to local populations.

3. Emergency Training and Legal Protection: Training communities on how to respond in emergencies, such as when a tiger is spotted near human settlements, is highly critical. Villagers should be educated on how to stay calm, alert local authorities, and evacuate safely in the presence of a tiger. In addition, retaliatory killings and attacks on tigers should be strongly prohibited by law. Offenders should face severe consequences, including hefty fines and long-term prison sentences, to deter future acts of violence. This legal framework is vital to protect tigers from senseless killings motivated by fear, hostility or misunderstanding.

4. Relocation of Problem Animals: In cases where a tiger poses a significant threat to human safety, relocation can be an option. However, it must be carried out with expertise, caution and proper planning. Relocating a tiger to a suitable habitat away from human settlements can help resolve conflicts without resorting to violence or killing. Such measures should always be consulted with wildlife experts to ensure the well-being of both the animals and the local populations. Such initiatives have produced significant success in countries like Australia where problem estuarine crocodiles have been safely relocated to sanctuaries or zoos to prevent unnecessary culling of the crocodiles and human-wildlife conflict.

5. Changing Perceptions: Respect, Not Fear: The portrayal of tigers in media and education needs to be urgently re-framed. It is important to acknowledge that tigers are powerful predators. The media`s role in depicting them as mindless killing machines or as “cute” animals that can be approached without caution has contributed to the misrepresentation of the tiger`s image. As a community, we must understand that tigers are highly adaptable and occasionally dangerous, which is crucial. Fear and hostility should be replaced with respect and reverence. Understanding their role in the ecosystem and recognising their value is essential for fostering peaceful coexistence. Tigers should not be feared or romanticized but respected for the vital role they play in maintaining the health of forests and ecosystems.

6. The Consequences of Inaction: Without such initiatives, the consequences are grim. If human-wildlife conflict continues, many more tigers will suffer, either being injured or killed due to the encroachment of humans on their natural habitats. If these conflicts persist, the future of tigers in the wild is uncertain.

By embracing education, technology, governance reforms, and community engagement, we can create a safer, more harmonious coexistence between tigers and the people who share their environment. These efforts must be scaled up across India, ensuring that everyone, regardless of literacy level, has the tools and knowledge to protect both themselves and the wildlife with which they share their land. The fate of tigers depends on the actions we take today or the day may come when we can only see these magnificent animals in the pages of a book or a magazine, lost to extinction because of avoidable conflicts with humans.

Sources

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/guwahati/3-year-old-tigress-finds-home-in-assam-zoo-after-blinded-by- mob/articleshowprint/116774452.cms

https://www.hindustantimes.com/trending/tiger-blinded-in-vicious-attack-after-wandering-into-village-in- assam-report-101732367908945.html

https://www.etvbharat.com/en/!state/man-animal-conflict-attacked-by-mob-assam-tigress-loses-eye-unlikely-to- return-to-wild-enn24121002841

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

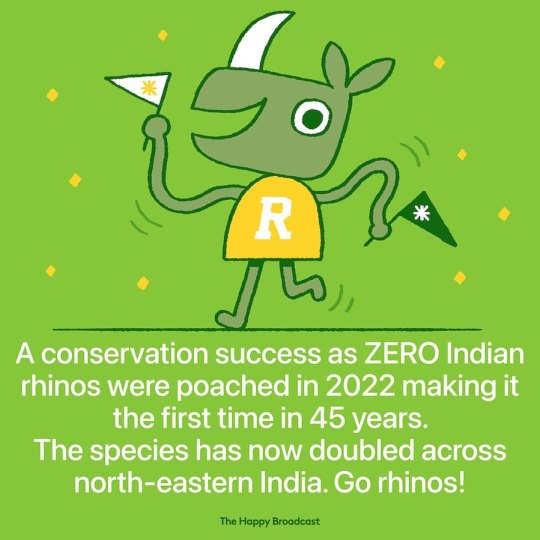

No rhinos were poached last year in the world's largest reserve for the endangered great one-horned rhinoceros, India's Assam state, in what authorities said was the first time since 1977.

Poachers killed more than 190 rhinos in Assam between 2000 and 2021 but none was killed last year, according to data shared by the Assam Police. According to IFAW, the greater one-horned rhino, also known as the Indian rhino, were once widespread across the entire northern region of India until they were decimated in the early 19th century due to the popularity of sport hunting. As a result, it is estimated that in 1908 there were only 12 rhinos left in Kaziranga, India. Thankfully, Assam, is now home to the world’s largest population of greater one-horned rhinos, with nearly 2,900 across the region today. Thanks to conservation efforts, the species has now doubled across north-eastern India. Source: World Animal News (link in bio)

#conservation #rhino #india https://www.instagram.com/p/CoH6aYer6n2/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Srividya: the twists and turns of a tantric tradition : Phil Hine

In the last two issues of my Unfoldings newsletter, I have been engaging in an in-depth analysis of Kenneth Grant’s representation of Tantric mysteries in his books – using his 1999 book, Beyond the Mauve Zone as the main reference point. In support of this series of essays, I thought it would be helpful for those reading the essays to attempt a general overview of the historical development of the Tripurāsundarī traditions, known nowadays as Śrīvidyā. In this first post, I’m going to focus on the roots of this tradition – the Nityā

The term Śrīvidyā is a compound formed from Śrī – an honorific denoting auspiciousness (also an epithet of the Goddess), and Vidyā – a feminine mantra.

Exoterically, Vidyā can denote knowledge or wisdom. The early texts of the tradition do not use this term though, rather, the tradition referred to itself as the traipuradarśana (doctrine of Tripurā) or sometimes, the Saugbhāgyavidyā (Saugbhāgya denotes good fortune, happiness, and success). According to Anna A. Golovkova (2020), the term Śrīvidyā first appears in a fourteenth-century commentary on the Yoginīhṛdaya. The tradition is sometimes referred to as the ‘last sampradāya’ – the most recent of the nine classical Śaiva tantric traditions. The principal or ‘root’ text of the tradition, the Vāmakeśvarīmata tantra has been dated to between the 10th-11th century CE.

The Nityā Tradition

Contemporary scholars have identified the antecedents of the worship of Tripurāsundarī within a lost Kaula tradition, known as the Nityā (‘eternal’). Much of what is known about this tradition has been gleaned from references in tantric scriptures.

As Golovkova points out, there are no references to the Nityā in works of the Trika tradition, but there are in the later Kubjika tradition, such as the Kubjikāmata (tenth century), the vast Manthānabhairava Tantra, and the Ciñciṇīmatasārasamuccaya. Only one scripture of the Nityā has survived – the Nityākaula. Chapter 30 of the Manthānabhairava Tantra which largely concerns the rules for writing and transmitting scripture, names the Nityākaula as one of the scriptures it considers valid.

In the Nityā tradition, the principal goddess is Kāmeśvarī, and her consort is the god of love, Kāmadeva, accompanied by eleven subordinate Nityā goddesses (see this long essay for some related discussion of Kāma, his weapons, particularly the Sugarcane Bow).

These Nityā goddesses are placed around a triangle (identified with the yoni) and intermediate points of an enclosing hexagram. The points of the triangle are identified with three pīṭhas (seats) of the goddess: Jālandhara, Pūrṇapīṭha, and Uḍḍiyāna. The fourth pīṭha, Kāmarūpa, is the centre of the triangle and the abode of Kāmeśvarī. Hence Kāmarūpa is considered to be the greatest of the śaktī pīṭhas.

The Kālikāpurāṇa (c.10-11th century) gives a lengthy description of Kāmarūpa (Assam) as a kind of divine wonderland, where death cannot enter; where there are no temples or images, but the deities are present as mountains, ponds, trees, and streams. After the terrible events of Dakṣa’s sacrifice, Śiva’s spouse, Satī took her own life. The grieving Śiva carted her body about with him until the other gods sliced up her body. The goddess’ yonimaṇḍala fell at Kāmarūpa, on Mount Kāmagiri (mountain of desire).

The Kāmākhyā temple complex is a centre of Śakta Tantra, and the goddess Kāmākhyā is worshipped there in the form of a yoni-stone, submerged in a natural stream, located in an underground chamber beneath the temple. According to the Kālikāpurāṇa, bathing in the waters of this stream results in release from rebirth and instant liberation. The Kaulajñānanirṇaya says that all of the women who reside in Kāmarūpa are Yoginīs who can reveal secrets and grant siddhis.

Kāmeśvarī is described as being of red hue, bearing weapons the weapons of Kāmadeva (noose, goad, bow, flower-arrows), and extensively ornamented (see these posts for some related discussion of ornamentation).

According to Golovkova, many of these elements appear in the Vāmakeśvarīmata (and later scriptures) – such as the goddess’ red hue; her bearing of the weapons of Kāma; the triangle and her triadic form; and her identification with the pīṭhas. Although, in the later tradition, Kāma has been supplanted by Śiva, there are many references to Kāma – particularly in the names of the groups of subsidiary goddesses populating the layers of the Śricakra (here’s a quick tour through the Śricakra).

In her paper, Golovkova gives a very insightful comparison between a passage she has translated from the Nityākaula and a very similar passage from the Vāmakeśvarīmata. Both passages show that the worship of the goddesses necessitates that the (male) adept should, having installed the goddess in his own body using Nyāsa, must dress in red clothing, adorn himself with flowers, smear his body with red unguent, apply eyeliner (collyrium), chew betel and spices, and equip himself with the weapons of Kāma. He is trying to further identify himself with the goddess by taking on her physical characteristics. Similar practices, albeit directed at emulating the fury of Bhairava are described in the mudrākośa section of the Jayadrathayāmala. This kind of ritualistic male performance of femaleness can be found in early tantric scriptures -even those of the orthodox Śaiva Siddhanta.

The attraction of female partners – human, or otherwise (nāgas, gāndharvas, yakṣinīs, for example) is a core concern of the Nityākaula, and again, as Golovkova shows, this is a focus of the Vāmakeśvarīmata. I concur. There is a great deal of emphasis on not only attracting women but gaining wealth, and power, destroying enemies, and obtaining siddhis in the Vāmakeśvarīmata – and relatively little directed towards what we think of as spiritual liberation.

Locating female agency is always a tricky proposition in regards to the tantras. In this respect, Golovkova argues that in these early scriptures, women have no agency at all – they are highly sexualized, mere objects for the male ritual gaze and acquisition, subjects of practices that aim at attracting and subordinating them."

Sources:

- Bagchi, P.C., Magee, Mike. 1986. Kaulajnana-nirnaya of the The School of Matsyendranatha. Prachya Prakashan.

-Dyczkowski, Mark S.G. (2009). Manthanabhairavatantram Kumarikakhandah (The Section Concerning the Virgin Goddess of the Tantra of the Churning Bhairava In Fourteen Volumes). Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts and D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd.

-Golovkova, Anna A. 2020. ‘The Forgotten Consort: The Goddess and Kāmadeva in the Early Worship of Tripurasundarī’. International Journal of Hindu Studies. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11407-020-09272-6

-Magee, Mike. 2011. The Mysteries of the Red Goddess. Prakasha Publishing.

-Rosati, Paolo E. 2023. ‘Crossing the boundaries of sex, blood and magic in the Tantric cult of Kāmākhyā’ in Acri, Andrea and Rosati, Paolo E. (eds) Tantra, Magic, and Vernacular Religions in Monsoon Asia. Routledge."

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things are bleak when even the insatiable businesses, industrialists, and colonial governors of the British Empire say that wealth and profit should be secondary goals compared to the most important mission and guiding principle of provoking "pain, dread, and terror".

---

[There was] development of a penal order or prison disciplinary system in nineteenth-century colonial India designed to extract the labour of convicts [...]. Colonial authorities, particularly in Bengal, the largest presidency of India, which then included the present-day states of West Bengal, Assam, [...] and the nation-state of Bangladesh, increasingly deployed prisoners in intramural [indoor] instead of extramural [outdoor] work. [...] The shift to handicrafts production resulted from the efforts of the colonial state to increase the severity of the conditions of incarceration as per the recommendations of the influential Prison-Discipline Committee of the late 1830s that found the existing penal disciplinary system wanting [...]. According to this Committee, whose report became the primer for penal and judicial reform in the nineteenth century, the employment of prisoners in public works, especially road construction, was definitely ‘the worst method of treatment … ever … provided under the British Government for this class of persons'. [...] In its estimation, [...] such outdoor work [...] had the additional [...] [quality] of developing ‘frightful’ rates of mortality.

Particularly in Bengal, the initial experiments [...] gave way to [...] employment of prisoners indoors in handicrafts production [...]. No one championed that practice more enthusiastically than F. J. Mouat, a medical officer who became the inspector-general of prisons in Bengal in 1855 and convened the first ever province-wide exhibition in Calcutta in 1856 to celebrate and stimulate jail handicrafts in the region. [...] That began to change, however, as administrators at different levels of government raised concerns about the lack of severity of indoor penal regimens [...]. An 1877 conference convened to improve jail discipline concluded that colonial authorities needed to reconsider the merits of public works [favored as a more severe punishment, 'the worst method of treatment ever'] [...]. In the early 1880s Calcutta followed up with a directive urging local officials [...] to employ more inmates in public works [outdoors]. [...] Indeed, colonial debates about mobilizing convict labour to work indoors or outdoors were always centred on concerns about ensuring and maximizing the severity of imprisonment and not the rehabilitation of prisoners. [...]

---

At the turn of the nineteenth century [early 1800s], prisoners in Bengal, as in the other presidencies of Bombay and Madras, worked [outdoors on "public works"] [...]. Even at this early juncture, authorities at the highest level of the colonial and imperial government [...] worried that their disciplinary practices were not tasked with chores requiring greater exertion [...]. Consequently, London and Calcutta encouraged local officials to employ prisoners in [...] roads in particular [because the conditions were more brutal] [...]. They also broached the possibility of moving convicts away from their home districts so that they would not have access to friends and family. [...] And with local officials eager to capitalise on prison labour, judicial authorities helped increase convict numbers [...] in the first decade of the nineteenth century that authorized courts to tack on hard labour (and banishment) for particular offences. [...]

[T]he Prison-Discipline Committee [made the] proposal to make imprisonment 'a terror to evil-doers' by compelling inmates to engage in 'dull, wearisome, monotonous tasks' [...].

---

[But] Mouat’s plan was to transform jails into ‘schools of industry’ [...]. [He wanted to make jails profitable, de facto businesses. To do this, he advocated indoor handicrafts production.] [H]e singled out certain jails for their productivity, Alipore [...] in particular [...] producing 'an actual profit of £74,232 [...]'. He boasted that this record was unmatched 'in any country or in any prison of the whole world'. [...] Not everyone shared Mouat’s faith in ‘industrial training’ as a punishment [...].

But the 1864 Committee [...], [m]uch more so than the Bengal inspector-general [Mouat] ever did, [in] its report emphasized making imprisonment 'a matter of dread, apprehension, and avoidance'.

Everything was to be secondary to that guiding principle, including making penal labour profitable [...].

---

As the lieutenant-governor put it, the prevailing system focused overly on manufactures and sanitary conditions and not enough on the ‘penal effect of imprisonment’. Therefore, it needed revamping to make the punishment of short-term prisoners more ‘stinging’, labour more penal, [...] so that Bengal jails would not be ‘a complete liberty hall’. [...]. For colonial officials, the [initial] interest in establishing [...] [indoor] hand labour in prisons was prompted primarily by their concern with [...] lessening the high costs of incarceration which resulted from the added expenses of employing extra guards to watch over inmates labouring outdoors. [But the government was willing to pay more, and to lose a source of profit, for the sake of making the punishment more severe.] [...] To his [Mouat's] detractors, intramural work in handicrafts production did not add up to hard labour -- it was not rigorous enough, [...] and therefore diminished the severity of imprisonment as a punishment, particularly in comparison to the demands of labouring outdoors on the roads or operating the treadwheels that some authorities wished to introduce to indoor labour.

His opponents also questioned his emphasis on profitability, which they believed distracted prison officials from ensuring that incarceration entailed pain and deprivation.

---

Text above by: Anand A. Yang. "The prison-handicraft complex: Convict labour in colonial India". Modern Asian Studies, Volume 57, Issue 3, May 2023, pages 808-834. Published online: 27 February 2023. At DOI: 10.1017/S0026749X22000324 [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Italicized first heading/sentence in this post added by me. Text within brackets added by me for clarity. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#it is usually said that imperial violence is kinda impersonal in the sense that its a means to an end to achieve wealth#in this case they see the cruelty itself as valuable#abolition#ecology#imperial#colonial#carceral#intimacies of four continents#tidalectics#victorian and edwardian popular culture#carceral geography

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rotary 6 Head ROPP Capping Machine

Company Overview: Shiv Shakti Machtech is a Supplier, Exporter, and Manufacturer of Rotary 6 Head ROPP Capping Machine in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India A Rotary 6 Head ROPP capping machine is an automated system designed to apply ROPP caps to bottles using six rotating capping heads. The rotary mechanism allows for continuous operation and high-speed capping, making it suitable for medium to large-scale production lines. The machine features advanced controls and adjustments to ensure accurate and consistent sealing of bottles. Key Features: Rotary Design: Ensures continuous capping process, enhancing productivity. 6 Head Configuration: Allows simultaneous capping of multiple bottles, maximizing throughput. ROPP Sealing: Provides tamper-evident closure with aluminum caps, ensuring product integrity. Adjustable Speed and Torque: Enables customization according to bottle size and cap type. Stainless Steel Construction: Durable and hygienic material suitable for pharmaceutical and food applications. User-Friendly Interface: Intuitive controls for easy operation and maintenance. Safety Features: Built-in mechanisms for operator safety and operational reliability. Applications: Beverage Industry Pharmaceutical Industry Cosmetic Industry Food Industry Shiv Shakti Machtech is a Rotary 6 Head ROPP Capping Machine in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India, Including Kathwada, Vadodara, Changodar, Gota, Naroda, Nikol, Mehsana, Palanpur, Deesa, Patan, Vapi, Surendranagar, Bhavnagar, Jamnagar, Junagadh, Rajkot, Amreli, Mahuva, Surat, Navsari, Valsad, Silvassa, Porbandar, Mumbai, Vasai, Andheri, Dadar, Maharashtra, Aurangabad, Kolhapur, Pune, Rajasthan, Jaipur, Udaipur, Kota, Bharatpur, Ankleshwar, Bharuch, Ajmer, Delhi, Noida, Baddi, Solan, Himachal Pradesh, Una, Jammu Kashmir, Haryana, Hisar, Gurgaon, Gurugram, Madhya Pradesh, Indore, Bhopal, Ratlam, Jabalpur, Satna, New Delhi, Kolkata, West Bengal, Assam, Asansol, Siliguri, Durgapur, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, Brahmapur, Puri, Goa, Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, Visakhapatnam, Hyderabad, Guntur, Chittoor, Kurnool, Vizianagaram, Srikakulam, Karimnagar, Ramagundam, Suryapet, Telangana, Medak, Bengaluru, Bangalore, Mangaluru, Hubballi, Vijayapura, Davanagere, Kalaburagi, Chitradurga, Ballari, Kolar, Chennai, Coimbatore, Madurai, Tiruchirapalli, Tiruppur, Salem, Erode, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram, Kozhikode, Thrissur, Kollam, Alappuzha, Kottayam, Kannur, Malappuram, Bharatpur, Jodhpur, Bikaner, Alwar, Bhilwara, Nagpur, Amravati, Solapur, Malegaon, Navi Mumbai, Thane, Wardha, Vasai-Virar, Gondia, Hinganghat, Barshi, Ulhasnagar, Nandurbar, Bhusawal, Pimpri-Chinchwad, Kalyan, Satara, Yamuna Nagar, Chhachhrauli. For further details or inquiries, feel free to reach out to us. View Product: Click Here Read the full article

#Ahmedabad#Ajmer#Alappuzha#Alwar#Amaravati#Amravati#Amreli#Andheri#AndhraPradesh#Ankleshwar#Asansol#Assam#Aurangabad#Baddi#Ballari#Bangalore#Barshi#Bengaluru#Bharatpur#Bharuch#Bhavnagar#Bhilwara#Bhopal#Bhubaneswar#Bhusawal#Bikaner#Brahmapur#Changodar#Chennai#Chhachhrauli

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

First day of the #Aloukik event.

I'm from Assam, India so I'll be sharing some folktales and lores from my state.

But today I just wanna tell y'all the story of how we got the name of our state. Not the name Assam, but its original names- Kamarupa and Pragjyotishpura, the names that our state was referred to as in the epics of our country.

As for the first name, Kamarupa, this is what happened according to the scriptures-

The mythology regarding the origin of the name Kamarupa tells us the story of Sati who died due to the discourtesy shown to her husband by her father Daksha. Overcame by grief, Shiva carried her dead body and wandered throughout the world. In order to put a stop to this, Vishnu used his discus to cut the body into pieces, which then fell into different places. One such piece fell down on Nilachal hills near Gauhati and the place was henceforth held sacred as Kamakhya. But Shiva’s penance did not stop, so the Gods sent Kamdev, the cupid to break his penance by making him fall in love. Kamdev succeeded in his mission, but Siva enraged at this result, burnt Kamdev to ashes. Kamdev eventually regained his original form here and from then onward the country came to be known as Kamarupa (Where Kama regained his Rupa or form).

In case of the second name, Pragjyotishpura, this was the case.

Bhagadatta was the son of Narakasura, and he named his city Pragjyotishpura, where 'prag' means 'eastern', 'jyotish' means 'star' or 'astrology' and 'pura' means 'city'. So the meaning behind the name of this kingdom was the City of Eastern Star or City of Eastern Astrology.

In case of the modern name, Assam, formerly called Axom or Asom, the sources of its origin are vague so I'm not gonna talk about it.

Welp that's it for the first day I guess. A goof introductory history rant on how my state got its ancient names.

@kathaniii

27 notes

·

View notes