#Ashigaru

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sundew clothing, based off Ashigaru, Japanese light infantry! The helmet is called a jingasa, and the straw raincoat a mino. I headcanon that the poisonwings lop off their horns when drafted into the military, to make it easier to fit helmets onto their heads, to use the horns for composite bows, and for a symbolic reason as well. I also like the idea of Pantalan dragons using primitive fire arms, though not quite effective enough to completely phase out melee weapons and bows.

#dragon#wof#wings of fire#art#dragons#fantasy#wof fanart#fanart#wingsoffire#armor#Mino#jingasa#Clothing design#dragon armor#Ashigaru

586 notes

·

View notes

Text

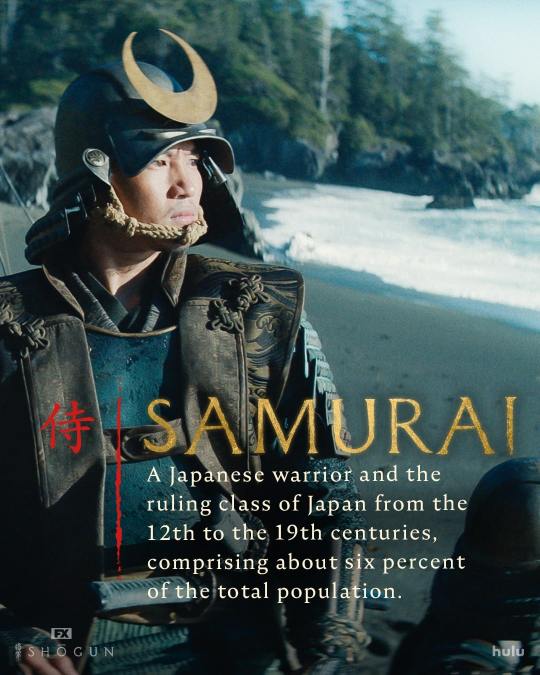

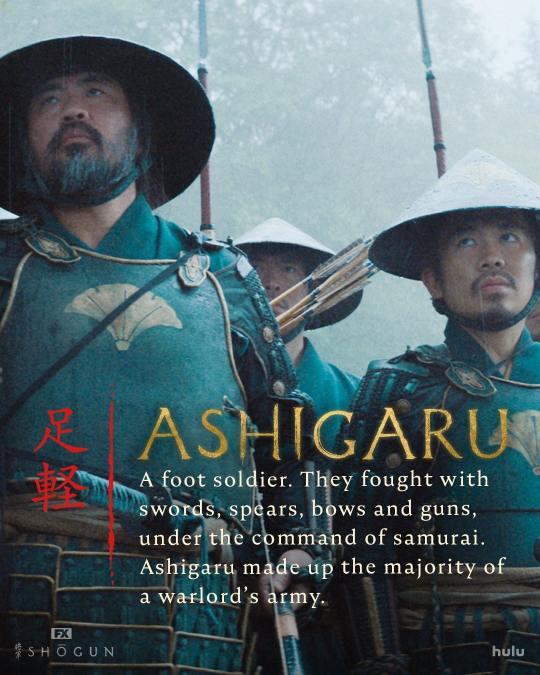

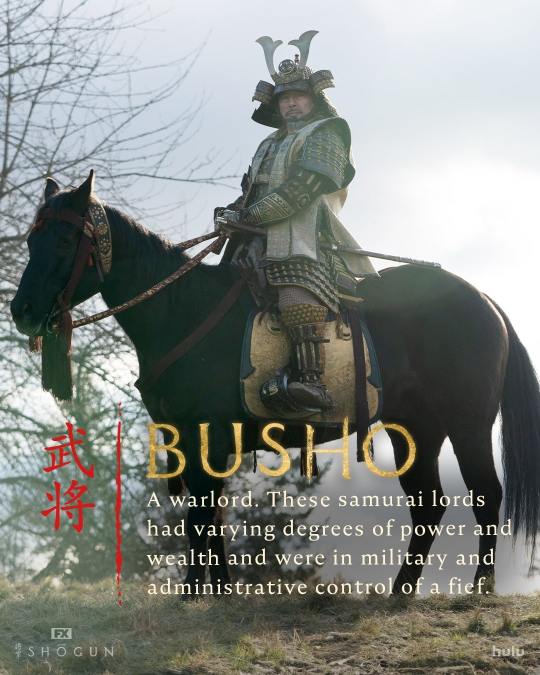

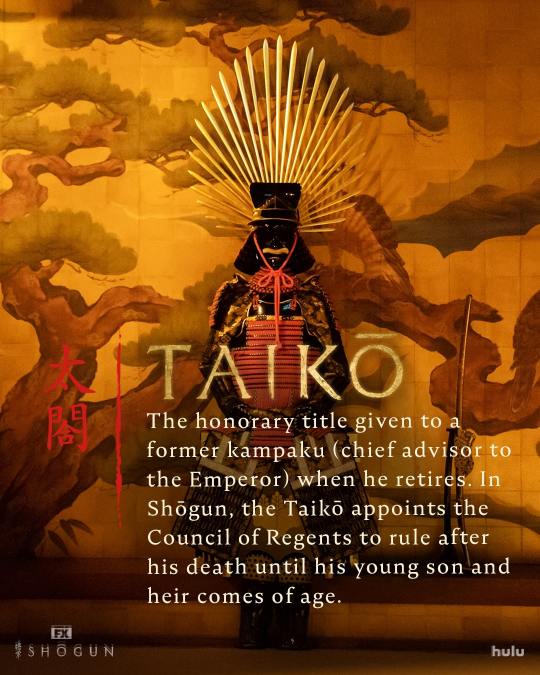

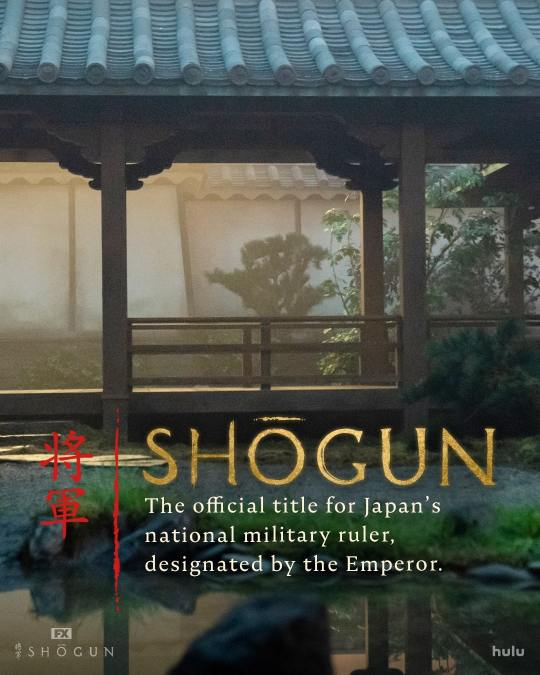

The ranks and titles in Feudal Japan by FX's Shogun

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some 10mm Wargames Atlantic ashigaru

Comically fragile yari aside, was a pretty fun and easy paintjob

I should paint small scale stuff more often

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

A vault of creative treasures! Explore our latest projects featuring Darkeater Midir, Cyberpunk, Space Cats, Test of Honour, Orks 👉 Dreaming of epic-painted models? Contact us at [email protected] and start your journey with us today!

#paintingwarhammer#paintingminis#paintingminiatures#historicalwargaming#clashofkatanas#testofhonour#ashigaru#feudaljapan#scalemodel#cyberpunk2077#cyberpunk#Orks#Gorkanaut#Morkanaut#tytans#spacecats#Nemesis#boardgames#Darkeater#Midir#darksouls

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

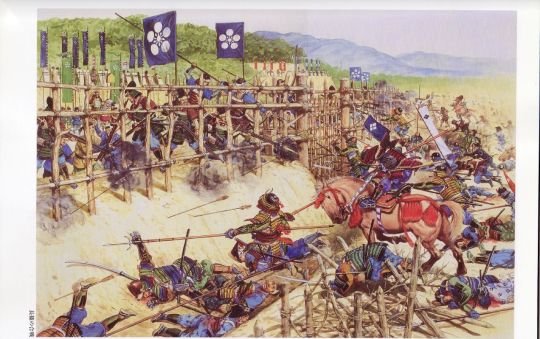

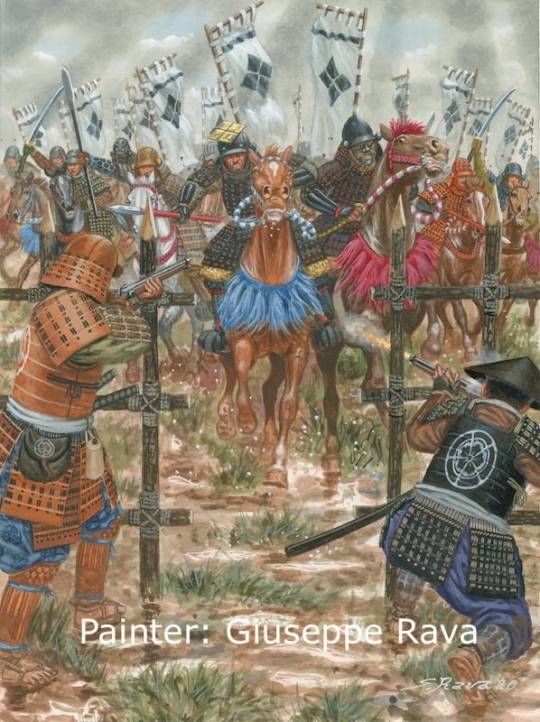

Ten Depictions of the Battle of Nagashino (1575)

Artists are identified in captions

#sengoku period#warring states#japanese history#samurai#oda nobunaga#tokugawa ieyasu#honda tadakatsu#takeda katsuyori#ashigaru#tanegashima#matchlock muskets#historical reconstruction#historical art#1500s#16th century#ritta nakanishi#angus mcbride#johnny shumate#osprey#richard hook#james field#brian palmer#howard gerrard#dan escott#giuseppe rava#gerry embleton#firearms#cavalry

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

FireForge Games - Ashigaru Shooters by Omar Samy

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

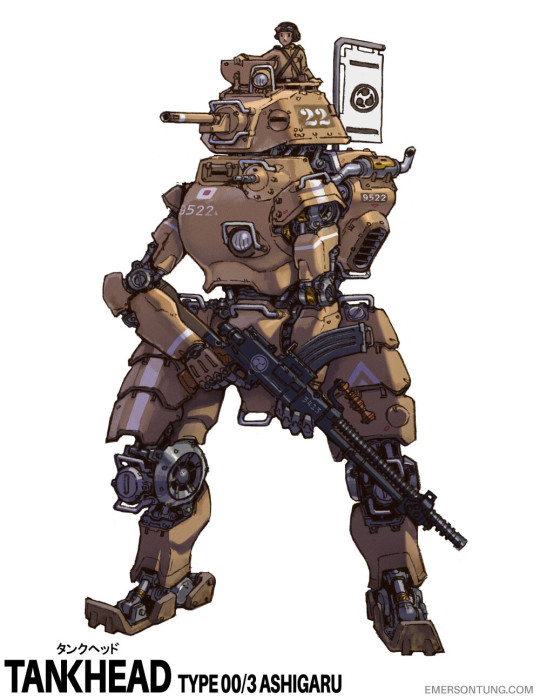

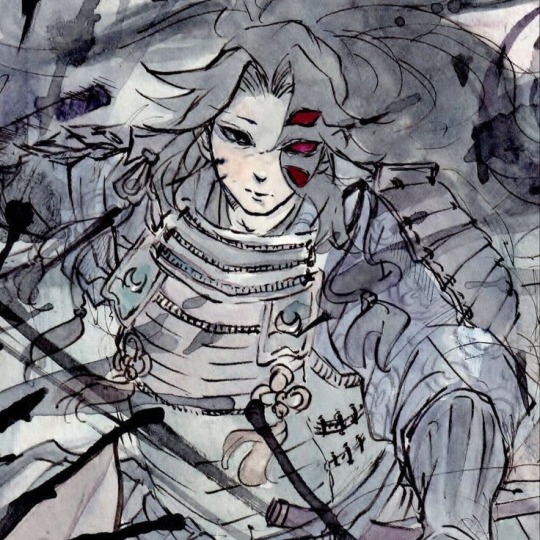

Light Tankhead Ashigaru by Emerson Tung

490 notes

·

View notes

Text

trying to read abut japanese weaponry is extremely annoying because people very rarely distinguish between samurai stuff (which is like, half ceremonial LARP) and ashigaru stuff (real war). MANY SUCH CASES

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michikatsu Tsugikuni in a Sengoku Era Battlefield

Warnings⌇ Violence, mentions of beheading

▪︎In the battleground, Michikatsu would be positioned on horseback, flanked by about two foot soldiers [in accordance to my previous theory posts]. It is also worth mentioning that warfare during the Sengoku period did not involve immediate charges; rather, it initially commenced at a gradual pace.

▪︎The two rival armies would steadily move towards each other, accompanied by the rhythm of war drums echoing throughout. As the adversaries neared, it fell to Michikatsu to uphold discipline within his troops, skillfully guiding them and directing their movements.

▪︎Michikatsu would ensure that none of his more tender-hearted or inexperienced soldiers succumbed to fear; he would bolster their resolve. With a firm and authoritative voice, he would motivate them, ensuring that none would flee before the battle even commenced.

▪︎As the adversaries closed in, the front line of ashigaru would engage in combat with precision and coordination, while the yari samurai provided support to the yari ashigaru. Should the Ashigaru succeed in holding their position, the samurai would then advance from both flanks to strike at the enemy.

It is alo important to note that during these wars, capturing the heads of high-ranking individuals was rewarded. This became a common practice among the samurai during that era.

▪︎Michikatsu would be present, equipped, and ready to assist his troops if necessary. Should he decide to engage, he would move forward to confront the enemy in close combat. At this point, the drums would resonate with full intensity, mirroring the tense atmosphere of the battle.

▪︎Michikatsu would then be locked in with another high ranking samurai; their weapons would clash and clash to get a strike, soon ditching their weapons and wrestling each other to the mud where Michikatsu dominates him; discarding his sword to draw out a dagger instead to ensure the grim task at hand-- ▪︎Pinning him down with his full body weight, ensuring the warrior beneath was completing caged under his imposing form--yanking of the man's head guard as he'd wrap his hand in his hair, pulling at it as he would start working on his neck using his dagger

▪︎As Michikatsu conducted his affairs, his men would stand guard around him, ready to tackle and kill off any intruders who dared to come near.

▪︎Once an enemy head would be taken, Michikatsu would promptly remount on his horse, with his infantry shielding his retreat. This pattern would continue; with Michikatsu chosing to engage any high-ranking or formidable adversary he believed his soldiers could not manage, taking control of the situation himself.

▪︎Ultimately, the opposing army would face a humiliating defeat, leaving them with no other option but to retreat.

▪︎The surviving warriors would gather to present the heads, or at the very least, the upper lips or noses of their befallen foes, as they assembled along with Michikatsu before the taisho [commander], who awaited their arrival in full armor for inspection.

▪︎With a deep bow, Michikatsu would declare his achievements, offering the head of a high-ranking samurai to the lord, and possibly presenting a prestigious sword he might have picked up as part of his tribute.

▪︎ With all the formalities set aside, the night would then ensue in celebrations, and lots and lots of drinking—Michikatsu and his fellow comrades getting drunk before gathering for a big meal

#🌙 ᴄɪᴠɪʟɪᴢᴇ ᴛʜᴇ ᴍɪɴᴅ ʙᴜᴛ ᴍᴀᴋᴇ sᴀᴠᴀɢᴇ ᴛʜᴇ ʙᴏᴅʏ║ 𝐌υ𝗌𝗂𐓣𝗀𝗌#michikatsu tsugikuni#kimetsu no yaiba#kokushibou#michikatsu#tsugikuni michikatsu#demon slayer michikatsu#kny michikatsu#Michikatsu x reader#Michikatsu war scenario#Sengoku era#samurai#kokushibo x reader#kny kokushibo#demon slayer#Michikatsu headcanons

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shōgun Historical Shallow-Dive: the Final Part - The Samurai Were Assholes, When 'Accuracy' Isn't Accurate, Beautiful Art, and Where to From Here

Final part. There is an enormous cancer attached to the samurai mythos and James Clavell's orientalism that I need to address. Well, I want to, anyway. In acknowledging how great the 2024 adaptation of Shōgun is, it's important to engage with the fact that it's fiction, and that much of its marketed authenticity is fake. That doesn't take away from it being an excellent work of fiction, but it is a very important distinction to me.

If you want to engage with the cool 'honourable men with swords' trope without thinking any deeper, navigate away now. Beyond here, there are monsters - literal and figurative. If you're interested in how different forms of media are used to manufacture consent and shape national identity, please bear with me.

I think the makers of 2024's Shōgun have done a fantastic job. But there is one underlying problem they never fully wrestled with. It's one that Hiroyuki Sanada, the leading man and face of the production team, is enthusiastically supportive of. And with the recent announcement of Season 2, it's likely to return. You may disagree, but to me, ignoring this dishonours the millions of people who were killed or brutalised by either the samurai class, or people in the 20th century inspired by a constructed idea of them.

Why are we drawn to the samurai?

A pretty badly sourced, but wildly popular history podcast contends that 'The Japanese are just like everybody else, only more so.' I saw a post on here that tried to make the assertion that the show's John Blackthorne would have been exposed to as much violence as he saw in Japan, and wouldn't have found it abnormal.

This is incorrect. Obviously 16th and 17th century Europe were violent places, but they contained violence familiar to Europeans through their cultural lens. Why am I confidently asserting this? We have hundreds of letters, journals and reports from Spaniards, Portuguese, Dutch and English expressing absolute horror about what they encountered. Testing swords on peasants was becoming so common that it would eventually become the law of the land. Crucifixion was enacted as a punishment for Christians - first by the Taiko, then by the Tokugawa shogunate - for irony's sake.

Before the end of the feudal period, battles would end with the taking of heads for washing and display. Depending on who was viewing them, this was either to honour them, or to gloat: 'I'm alive, you're dead.' These things were ritualised to the point of being codified when real-life Toranaga took control. Seppuku started as a cultural meme and ended up being the enforced punishment for any minor mistake for the 260 years the ruling samurai class acted as the nation's bureaucracy. It got more and more ritualised and flowery the more it got divorced from its origin: men being ordered by other men to kill themselves during a period of chaotic warfare. I've read accounts of samurai 'warriors' during the Edo period committing seppuku for being late for work. Not life-and-death warrior work - after Sekigahara, they were just book-keepers. They had desk jobs.

Since Europe's contact with Japan, the samurai myth has fascinated and appalled in equal measure. As time has gone on, the fascination has gone up and the horror has been dialled down. This is not an accident. This isn't just a change in the rest of the world's perception of the samurai. This is the result of approximately 120 years of Japanese government policies. Successive governments - nationalist, military authoritarian, and post-war democratic - began to lionize the samurai as the perfect warrior ideal, and sanitize the history of their origin and their heydey (the period Shōgun covers). It erases the fact that almost all of the fighting of the glorious samurai Sengoku Jidai was done by peasant ashigaru (levies), who had no choice.

It is important to never forget why this was done initially: to form an imagined-historical ideal of a fighting culture. An imagined fighting culture that Japanese invasion forces could emulate to take colonies and subdue foreign populations in WWI, and, much more brutally, in WWII. James Clavell came into contact with it as a Japanese Prisoner of War.

He just didn't have access to the long view, or he didn't care.

The Original Novel - How One Ayn Rand Fan Introduced Japan to America

There's a reason why 1975's Shogun novel contains so many historical anachronisms. James Clavell bought into a bunch of state-sanctioned lies, unachored in history, about the warring states period, the concept of bushido (manufactured after the samurai had stopped fighting), and the samurai class's role in Japanese history.

For the novel, I could go into great depth, but there are three things that stand out.

Never let the truth get in the way of a good story. He's a novelist, and he did what he liked. But Clavell's novel was groundbreaking in the 70's because it was sold as a lightly-fictionalised history of Japan. The unfortunate fact is the official version that was being taught at the time (and now) is horseshit, and used for far-right wing authoritarian/nationalist political projects. The Three Unifiers and the 'honour of the samurai' magnates at the time is a neat package to tell kids and adults, but it was manufactured by an early-20th century Japanese Imperial Government trying to harness nationalism for building up a war-ready population. Any slightly critical reading of the primary sources shows the samurai to be just like any ruling class - brutal, venal, self-interested, and horrifically cruel. Even to their contemporary warrior elites in Korea and China.

Fake history as propraganda. Clavell swallowed and regurgitated the 'death before dishonour', 'loyalty to the cause above all else', 'it's all for the Realm' messages that were deployed to justify Imperial Japanese Army Class-A war crimes during the war in the Pacific and the Creation of the Greater East Asian Co-Properity Sphere. This retroactive samurai ethos was used in the late Meiji restoration and early 20th century nationalist-military governments to radicalise young Japanese men into being willing to die for nothing, and kill without restraint. The best book on this is An Introduction to Japanese Society by Sugimoto Yoshio, but there is a vast corpus of scholarship to back it up.

Clavell's orientalism strays into outright racism. Despite the novel Shōgun undercutting John Blackthorne as a white savior in its final pages - showing him as just a pawn in the game - Clavell's politics come into play in every Asia Saga novel. A white man dominates an Asian culture through the power of capitalism. This is orthagonal to points 1 and 2, but Clavell was a devotee of Ayn Rand. There's a reason his protagonists all appear cut from the same cloth. They thrust their way into an unfamiliar society, they use their knowledge of trade and mercantilism to heroically save the day, they are remarked upon by the Asian characters as braver and stronger, and they are irresistible to the - mostly simpering, extremely submissive - caricatures of Asian women in his novels. Call it a product of its times or a product of Clavell's beliefs, I still find it repulsive. Clavell invents (nearly from whole cloth, actually) the idea that samurai find money repulsive and distasteful, and his Blackthorne shows them the power of commerce and markets. Plus there are numerous other stereotypes (Blackthorne's massive dick! Japanese men have tiny penises! Everyone gets naked and bathes together because they're so sexually free! White guys are automatically cool over there!) that have fuelled the fantasies of generations of non-Japanese men, usually white: Clavell's primary audience of 'dad history' buffs.

2024's Shōgun, as a television adaptation, did a far better job in almost every respect

But the show did much better, right? Yes. Unquestionably. It was an incredible achievement in bringing forward a tired, stereotypical story to add new themes of cultural encounter, questioning one's place in the broader world, and killing your ego. In many ways, the show was the antithesis to Clavell's thesis.

It drastically reigned in the anachronistic, ahistorical referencees to 'bushido' and 'samurai honor', and showed the ruling class of Japan in 1600 much more accurately. John Blackthorne (William Adams) was shown to be an extraordinary person, but he wasn't central to the outcome of the Eastern Army-Western Army civil war. There aren't scenes of him being the best lover every woman he encounters in Japan has ever had (if you haven't read the book, this is not an exaggeration). He doesn't teach Japanese warriors how to use matchlock rifles, which they had been doing for two hundred years. He doesn't change the outcome of enormous events with his thrusting, self-confident individualism. In 2024's Shōgun, Blackthorne is much like his historical counterpart. He was there for fascinating events, but not central. He wasn't teaching Japanese people basic concepts like how to make money or how to make war.

On fake history - the manufactured samurai mythos - it improved on the novel, but didn't overcome the central problems. In many ways, I can't blame the showrunners. Many of the central lies (and they are deliberate lies) constructed around the concept of samurai are hallmarks of the genre. But it's still important to me to notice when it's happening - even while enjoying some of the tropes - without passively accepting it.

'Authenticity' to a precisely manufactured story, not to history

There's a core problem surrounding the promotion and manufactured discussion surrounding 2024's Shōgun. I think it's a disconnect between the creative and marketing teams, but it came up again and again in advertising and promotion for the show: 'It's authentic. It's as real as possible.'

I've only seen this brought up in one article, Shōgun Has a Japanese-Superiority Complex, by Ryu Spaeth:

'The show also valorizes a supreme military power that is tempered by the pursuit of beauty and the highest of cultures, as if that might be a formula for peace. Shōgun displays these two extremes of the Japanese self, the savagery and the refinement, but seems wholly unaware that there may be a connection between them, that the exquisite sensibility Japan is famous for may flow from, and be a mask for, its many uses of atrocious domination.'

Here we come to authenticity.

'The publicity surrounding the series has focused on its fidelity to authenticity: multiple rounds of translation to give the dialogue a “classical” feel; fastidious attention to how katana swords should be slung, how women of the nobility should fold their knees when they sit, how kimonos should be colored and styled; and, crucially, a decentralization of the narrative so that it’s not dominated by the character John Blackthorne.'

It's undeniable that the 2024 production spent enormous amounts of energy on authenticity. But authenticity to what? To traditional depictions of samurai in Japanese media, not to history itself. The experts hired for gestures, movement, costumes, buildings, and every other aspect of the show were experts with decades in experience making Japanese historical dramas 'look right', not experts in Japanese history. But this appeal to 'Japanese authenticity' was made in almost every piece of promotional material.

The show had only one historical advisor on staff, and he was Dutch. The numerous Japanese consultants, experts and specialists brought on board (talked about at length in the show's marketing and behind the scenes) were there to assist with making an accurate Japanese jidaigeki. It's the difference between hiring an experienced BBC period drama consultant, and a historian specialising in the Regency. One knows how to make things look 'right' to a British audience. The other knows what actually happened.

That's fine, but a critical viewing of the show needs to engage with this. It's a stylistically accurate Japanese period drama. It is not an accurate telling of Japanese history around the unification of Japan. If it was, the horses would be the size of ponies, there would be far more malnourished and brutalised peasants, the word samurai would have far less importance as it wasn't yet a rigidly enforced caste, seppuku wouldn't yet be ritualised and performed with as much frequency, and Toranaga - Tokugawa - would be a famously corpulently obese man, pounding the saddle of his horse in frustration at minor setbacks, as he was in history.

The noble picture of restraint, patience, refinement and honour presented by Hiroyuki Sanada as Toranaga/Tokugawa is historical sanitation at its most extreme. Despite being Sanada's personal hero, Tokugawa Ieyasu was a brutal warlord (even for the standards of the time), and he committed acts of horrific cruelty. He ordered many more after gaining ultimate power. Think a miniseries about the Founding Fathers of the United States that doesn't touch upon slavery - I'm sure there have been plenty.

The final myth that 2024's Shōgun leaves us with is that it took a man like Toranaga - Tokugawa Ieyasu - to bring peace to a land ripped assunder by chaos. This plays into 19th century notions of Great Man History, and is a neat story, but the consensus amongst historians is if it wasn't Tokugawa, it would have been some other cunt. In many cases, it very nearly was. His success was historical contingency, not 5D chess.

So how did this image get manufactured, to the point where the Japanese populace - by and large - believes it to be true? Very long story short: after a period of rapid modernisation, Japan embraced nationalism in the late 19th century. It was all the rage. Nationalism depends on a glorified past. The samurai (recently the pariahs of Japanese history) were repurposed as Japan's unique warrior heroes, and woven into state education. This was especially heated in the 1920s and 30s in the lead up to the invasion of Manchuria and Japan's war of aggression in the Pacific. Nationalism + militarism = the modern Japanese samurai myth, to prepare men to obey orders unquestioningly from a military dictatorship.

This persists in the postwar period. Every year since 1963, Japan's state broadcaster NHK commissions a historical drama - a Taiga Drama, where many of this show's actors got their starts - that manufactures and re-enforces the idea of samurai as noble, artful, honourable people. Read a book - read a Wikipedia article! - and you'll see that most of it stems from Tokugawa-shogunate era self-propaganda. It's much like the European re-interpretation of chivalry. In Europe's case, chivalry in actual history was a set of guidelines that allowed for the sanctioned mass-rape and murder of civilians, with a side of rules regarding the ransoming of nobles in scorched-earth military campaigns. In Japan's case, historical figures that regularly backstabbed each other, tortured rival warriors and their lessers, and inflicted horrific casualties on the peasants that they owned (we have a term for that) are cast as noble, honourable, dedicated servants of the Empire.

Why does this matter to me? Samurai movies and TV shows are just media, after all. The issue, for me, is that the actors, the producers - including Hiroyuki Sanada - passionately extoll 'accuracy' as if they genuinely believe they're telling history. They talk emotionally about bushido and its special place in Japanese society.

But the entire concept of bushido is a retroactive, post-conflict, samurai construction. Bushio is bullshit. Despite being spoken of as the central tenet of 2024's Shōgun by actors like Hiroyuki Sanada, Tadanobu Asano, and Tokuma Nishioka, it simply didn't exist at the time. It was made up after the advent of modern nationalism.

It was used to justify horrendous acts during the late Edo period, the Meiji restoration, and the years leading up to the conclusion of Japan's war of aggression in the Pacific. It's still used now by Japan's primarily right-wing government to deny war crimes and justify the horrors unleashed on Asia and the Pacific during World War II as some kind of noble warrior crusade. If you ever want your stomach turned, visit the museum attached to Yasukuni Shrine. It's a theme park dedicated to war crimes denial, linked intimately to Japan's imagined warrior past. Whether or not the production staff, cast, and marketing team of 2024's Shōgun knew they were engaging with a long line of ahistorical bullshit is unknown, but it is important.

It's also important to acknowledge that, having listened to many interviews with Rachel Kondo and Justin Marks, they were acutely aware that they weren't Japanese, to claim to be telling an authentically Japanese story would be wrong, and that all they could do was do their best to make an engaging work that plays on ideas of cultural encounter and letting go. I think the 'authenticity!' thing is mostly marketing, and judicious editing of what the creators and writers actually said in interviews.

So... you hate the show, then? What the hell is this all about?

No, I love the show. It's beautiful. But it's a beautiful artwork.

Just as the noh theatre in the show was a twisting of events within the show, so are all works of fiction that take inspiration from history. Some do it better than others. And on balance, in the show, Shōgun did it better than most. But so much of the marketing and the discussion of this adaptation has been on its accuracy. This has been by design - it was the strategy Disney adopted to market the show and give it a unique viewing proposition.

'This time, Shōgun is authentic!*

*an authentic Japanese period drama, but we won't mention that part.

And audiences have conflated that with what actually happened, as opposed to accuracy to a particular form of Japanese propaganda that has been honed over a century. This difference is crucial.

It doesn't detract from my enjoyment of it. Where I view James Clavell's novel as a horrid remnant of an orientalist, racist past, I believe the showrunners of 2024's Shōgun have updated that story to put Japanese characters front and centre, to decentralise the white protagonist to a more accurate place of observation and interest, and do their best to make a compelling subversion of the 'stranger in a strange land' tale.

But I don't want anyone who reads my words or has followed this series to think that the samurai were better than the armed thugs of any society. They weren't more noble, they weren't more honourable, they weren't more restrained. They just had 260 years in which they worked desk-jobs while wearing two swords to write stories about how glorious the good old days were, and how great people were.

Well... that's a bleak note to end on. Where to from here?

There are beautiful works of fiction that engage much closer with the actual truth of the samurai class that I'd recommend. One even stars Hiroyuki Sanada, and is (I think) his finest role.

I'd really encourage anyone who enjoyed Shōgun to check out The Twilight Samurai. That was the reality for the vast majority of post-Sekigahara samurai

For something closer to the period that Shogun is set, the best film is Seppuku (Hara-Kiri in English releases). It is a post-war Japanese film that engages both with the reality of samurai rule, and, through its central themes, how that created mythos was used to radicalise millions of Japanese into senseless death during the war. It is the best possible response to a romanticisation of a brutal, hateful period of history, dominated by cruel men who put power first, every single time.

I want to end this series, if I can, with hope. I hope that reading the novel or watching the 1980 show or the 2024 show has ignited in people an interest in Japanese culture, or society, or history. But don't let that be an end. Go further. There are so many things that aren't whitewashed warlords nobly killing - the social history of Japan is amazing, as is the women's history. A great book for getting an introduction to this is The Japanese: A History in 20 Lives.

And outside of that, there are so many beautiful Japanese movies and shows that don't deal with glorified violence and death. In fact, it makes up the vast majority of Japanese media! Who would have thought! Your Name was the first major work of art to bridge some of the cultural animosity between China and Japan stemming from WW2, and is a goofy time travel love story. Perfect Days is a beautiful movie about the simple joy of living, and it's about the most Tokyo story you can get.

Please go out, read more, watch more. If you can, try and find your way to Japan. It's one of the most beautiful places on earth. The people are kind, the food is delicious, and the culture is very welcoming to foreigners.

2024's Shōgun was great, but please don't let that be the end. Let it be the beginning, and I hope it serves as a gateway for you.

And I hope our little fandom on here remembers this show as a special time, where we came together to talk about something we loved. I'll miss you all.

#shōgun#shogun#shogun fx#toda mariko#john blackthorne#anjin#adaptationsdaily#perioddramasource#hiroyuki sanada#yoshii toranaga#akechi mariko#history#history lesson#japan#world war ii#japanese culture#tokugawa ieyasu#hosokowa gracia#william adams#sengoku jidai#writer stuff#book adaptation#women in history#social history#period drama

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I know I haven't been so active in the Napoleonic community in recent months, as I've been pretty absorbed with studying Japanese history and the Japanese language, but the more I've learned about Hideyoshi, the more I found myself comparing him to Napoleon, so here's a post where my two main historical interests get to intersect. :)

Toyotomi Hideyoshi has often been referred to as Japan’s Napoleon Bonaparte. Perhaps a bit Eurocentric given that Hideyoshi was born in 1537, 232 years before Napoleon--if anything it could be said that Napoleon was France’s Hideyoshi, but unfortunately Hideyoshi is not a name most Westerners recognize—otherwise it’s an excellent comparison. I’ve read a great deal about Napoleon over the past several years, and, although my studies on Sengoku Japan are only really in their infancy, I couldn’t help but notice a striking number of parallels and similarities between the lives and military/political careers of Hideyoshi and Napoleon.

Both men came from relatively humble origins and experienced meteoric rises through the ranks via their military service. Napoleon’s family on Corsica were minor nobility—they were not wealthy by any means but at least possessed enough connections to get Napoleon into a military academy; once his training was completed, he was commissioned as an artillery officer. Hideyoshi was born a peasant; his father was an ashigaru (foot soldier) who served a samurai. Hideyoshi followed in his father’s footsteps and became an ashigaru himself, which at the age of 26 brought him into the service of Lord Oda Nobunaga, who was soon the most powerful daimyo in Japan. His talents and intelligence impressed Nobunaga, and Hideyoshi rose to become one of his top generals and retainers by his early thirties. When Nobunaga was betrayed and assassinated in 1582, Hideyoshi, then 35, moved quickly to step into the ensuing power vacuum; within three years he had defeated his main rivals, consolidated his power, and become the most powerful man in Japan himself. Napoleon Bonaparte became a general at age 24 and crowned himself Emperor of the French at age 35. Hideyoshi was never Emperor, nor, being from a peasant background, did he receive the title of shogun, but he was designated kampaku (Imperial Regent) by the Emperor at age 38 and was the real power in the land from this point until his death in 1598.

As a result of their respective meteoric rises and remarkable military successes, both men came to view themselves as destined for greatness. Napoleon frequently spoke of destiny and believed himself guided by it. “Is there a man so blind,” he wrote in December of 1798, “as not to see that destiny itself guides all my operations? Is there anyone so faithless as to doubt that everything in this vast universe is bound to the empire of destiny?” (Broers, Napoleon: Soldier of Fortune, 195) This belief, which pervaded through his life, also made him take great risks, convinced that he was destined to succeed in his endeavors. Hideyoshi came to genuinely believe his own rise was divinely inspired and even developed his own backstory, giving himself celestial origins, and making sure to mention them frequently in his letters to others as a means of convincing them of the rightness of his cause. “At the time my mother conceived me,” he wrote on one occasion, “she had an auspicious dream. That night, a ray of sun filled the room as if it were noontime. All were overcome with astonishment and fright and when the diviners had gathered, they interpreted the event saying: when he reaches the prime of life, his virtue will illuminate the four seas, his authority will emanate to the myriad peoples.” (Berry, Hideyoshi, 9). He even went so far as bringing up his supposedly heavenly origins in a letter to the King of Korea, in hopes of pushing his case to the King to permit his armies safe passage through Korea so he could carry out his planned conquest of Ming China.

Both were regarded as military geniuses by their contemporaries. Napoleon’s quick, dominant successes in Italy, and his crushing victories against Austria, Russia, and Prussia between 1805-1807, solidified his reputation as one of the greatest generals in European history, and arguably the best military commander of his time. Hideyoshi never suffered a defeat in the numerous campaigns he waged over the years to complete the work of unifying Japan that had begun under Nobunaga.

Likewise, both men’s reputations for military genius were severely tarnished by campaigns driven out of an increasingly megalomaniacal drive for conquest abroad. Hideyoshi, his confidence bolstered by his string of military successes, began setting his sights on China, and even hinted in his correspondence that one day, after China had submitted as his vassal, he might even attempt to conquer India. To begin his conquest of China, he first needed to bring his armies through Korea. He attempted to negotiate with the King of Korea to gain safe passage for his armies, but Korea had strong ties to the Ming Dynasty, the negotiations soon broke down, and Hideyoshi sent his armies to invade Korea in 1592. The Japanese initially smashed through the pitiful Korean defenses and made a rapid drive up the peninsula, but with Ming reinforcements soon arriving to turn the tide, and the Japanese navy being repeatedly pummeled by the brilliant Admiral Yi Sun-Sin, the Japanese advance was soon stalled. Eventually the Japanese forces retreated to the southern coastline, where they hunkered down in hastily-built fortifications while peace negotiations dragged out for years between Hideyoshi’s court and the Ming court. When these negotiations also eventually broke down, Hideyoshi launched a second invasion of Korea, less for the sake of conquering China this time than simply for punishing Korea as much as possible for thwarting his initial plans. Hideyoshi himself never actually personally led his armies in Korea—he never went to Korea at all—but relied instead on the reports of his generals and inspectors, whose reports often downplayed or whitewashed the truth of Japanese defeats out of fear. Additionally, some of his primary commanders (like Konishi Yukinaga and Kato Kiyomasa) openly hated each other and their quarrels and personal rivalries occasionally hampered military operations, not unlike the quarrels of Napoleon’s commanders in Russia. The second invasion was turning into a stalemate when Hideyoshi abruptly died in September of 1598 at the age of 61. The remnants of the Japanese army eventually returned to Japan, and a six-year period of nearly relentless horrors and atrocities in Korea had all been for nothing. Napoleon, of course, launched his infamous 1812 invasion of Russia, which, while of much shorter duration than Hideyoshi’s war(s) in Korea, led to a much more thorough destruction of his armies and arguably contributed to his fall from power in 1814. Not that the Korean conflicts left the Toyotomi forces unscathed, and it can also be argued that the extent to which the Western armies had bled themselves out in Korea helped contribute to the victory of Hideoyoshi’s rival, Tokugawa Ieyasu, against his Toyotomi-loyalist enemies at Sekigahara in 1600, as Ieyasu, based in Japan’s eastern Kanto region, had pointedly kept his own forces out of the war.

Both men enacted sweeping reforms in their respective societies which long outlasted either them or the dynasties they both failed to leave behind. Both initiated nationwide cadastral surveys and land registries to make tax collection more accurate and efficient. In 1595, six leading daimyo under Hideyoshi drafted, on his behalf, a code comprised of fourteen brief articles, all of which were centered around keeping the peace, carrying out justice, and governing the behavior of the various social classes in Japan. Napoleon issued his civil code (also not written by himself), now known as the Napoleonic Code, in 1804. While not as brief as the Toyotomi regime’s code, it was written in the vernacular to make it more accessible to the average person.

Both were patrons of the arts; in Hideyoshi’s case, of Noh theater (which he became so passionate about he eventually even performed in plays in front of his subordinates), tea ceremonies, and painting; Napoleon also patronized painters, established art museums and, while not up to becoming a performer in his own right like Hideyoshi, he did attend the opera regularly.

Both Hideyoshi and Napoleon struggled to produce an heir. Hideyoshi’s only son, Tsurumatsu, died at the age of 2 in 1591. Hideyoshi named his nephew Hidetsugu his heir in the meantime, but hoped to have another son. Neither his wife nor his considerable number of concubines were able to give him a child, leading historians to speculate that Hideyoshi may have been sterile by this point, possible as the result of a sexually transmitted disease. In 1592 his concubine Yodo-dono, also known as Chacha, gave birth to a son, Hideyori, who would become Hideyoshi’s only heir (the unfortunate nephew, Hidetsugu, was soon charged with treason and forced to commit seppuku not long after Hideyori’s birth). Hideyoshi’s inability to create an heir with so many other women led to rumors spreading, even before he died, that Hideyori was not really his child. Napoleon also struggled to produce an heir for years after crowning himself Emperor, but, as he demonstrated no problem creating sons with his mistresses, the problem was attributed to his wife’s infertility. He divorced Josephine, married a much younger princess, and soon enough had an heir of his own.

When Hideyoshi died in 1598, his heir was only five years old; when Napoleon fell from power in 1815, his heir was four years old. Both Hideyoshi’s heir and Napoleon’s heir died at the age of 21.

#Toyotomi Hideyoshi#Napoleon Bonaparte#Napoleon#Napoleonic wars#Sengoku Jidai#history#military history#Japanese history#samurai

55 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

A Female and an African Ashigaru who respect each other.

Ashi Girl (Ep 2)

Yuinosuke (Yuina Kuroshima) is a Ashigaru (foot soldier) who wishes to serve the Lord and prove her worth by winning a race against a rival Clan.

Akumaru (Max) is the Ashigaru of the rival clan who is her competitor. His master wants him to win by any means necessary, even by cheating.

But Akumaru refuses to cheat as he respects his competitor as being earnest. His honourable attitude earns the respect of Yuinosuke.

This is what Netflix’s Yasuke should’ve been. It would’ve been interesting to focus on the relationship between Yasuke and Natsumaru.

It doesn’t have to be anything romantic. A relationship can be based on mutual respect like in the film, The Great Wall between William and Lin Mae.

#ashi girl#yuina kuroshima#kuroshima yuina#max#ashigaru#japanese drama#j drama#jdrama#dorama#japan#asian drama#yasuke#the great wall

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ashigaru archers done

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

a little wip of tr!sneeg fakemon :3 but i like to call it the newer version of his previous design cause i don't like it anymore

am going for a samurai inspiration(a bit funny cause i also based his design off of the american dagger moth caterpillar lmao) i am not so sure about this design tbh. it might just be the colors, which i based it off the ashigaru btw! since from what i've seen they are the lowest ranked samurai? feel free to correct me if i'm wrong though! anyways i am super tired rn so i'll go mimir and see how i feel about it after :P

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern movies and tales portray #ninjas using #shuriken, but they were mainly used by #samurai and ashigaru soldiers. The major varieties of shuriken are the bō shuriken (棒手裏剣, stick shuriken) and the hira shuriken (平手裏剣, flat shuriken) or shaken (車剣, wheel shuriken, also read as kurumaken).

Shuriken were supplementary weapons to the sword or various other weapons in a samurai's arsenal, although they often had an important tactical effect in battle. The art of wielding the shuriken is known as shurikenjutsu and was taught as a minor part of the martial arts curriculum of many famous schools, such as Yagyū Shinkage-ryū, Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū, Ittō-ryū, Kukishin-ryū, and Togakure-ryū.

25 notes

·

View notes