#American Deaf History

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Deaf History

I mentioned in an earlier post that I am a part of the deaf community. Being labeled CODA (child of deaf adult(s)) is what a person like myself is called. I am hearing, I can hear, but both of my parents, two of my three brothers, and vast majority of my maternal relatives are deaf. I grew up in that community, I grew up feeling more at home in that community than I ever did in the hearing community.

There's a whole culture to being deaf. There's the language, reading body language to convey tone, there's a whole thing about being deaf that goes beyond just knowing Sign Language. This is why when learning Sign Language, being immersed in it is the best way to learn. (But then, this is true of any and all languages.)

In so many ways, ASL (American Sign Language) is my first language. I learned how to sign first before I learned how to speak with my voice. I frequently found myself wishing I could go to the deaf school instead of the public school because I was more comfortable around deaf people than I was hearing people. (And no, I would not have been allowed to attend deaf school; it's restricted for deaf students only.)

I grew up accustomed to watching television, movies, etc, with captioning or subtitles. In fact, it's weird for me to watch them without. My mother didn't believe me at first until she asked an interpreter who was also CODA. The interpreter said it was the same for her.

My parents met at Gallaudet, the country's first, and so far, only deaf university. In fact, it's the first in the world. The history of Gallaudet, of American Sign Language, was all because of one man.

Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet's life was forever changed because of a deaf little girl named Alice.

Alice wasn't playing with other children and that drew his attention. Concerned as to why, Thomas found out that Alice was deaf and could not communicate at all. Determined to teach her, Thomas taught Alice what different objects were called by writing their names and drawing pictures of them with a stick in the dirt. Alice's father was impressed and hired Gallaudet to continue teaching Alice through the summer.

Alice's father, along with several businessmen and clergy, asked Gallaudet to travel to Europe to study methods for teaching deaf students. There was a family in Scotland that they wanted to work with, but that family refused for whatever reason. Plus, Gallaudet found their preference for oral communication extremely limited and did not produce desirable results.

While in Great Britain, Gallaudet met Abbé Sicard, head of the Institution Nationale des Sourds-Muets à Paris, and two of its deaf faculty members, Laurent Clerc and Jean Massieu. Gallaudet was invited to Paris to study the school's method of teaching the deaf using manual communication. Gallaudet studied the teaching methodology under Sicard, learning sign language from Massieu and Clerc.

Gallaudet sailed back to America with Clerc. The two men toured the New England region and raised funds for a deaf school in Hartford, Connecticut. It later became known as the American School for the Deaf in 1817. Alice was one of the first seven students.

One of Gallaudet's children, his youngest, founded the first college for the deaf, in 1864.

It is due to Gallaudet that American Sign Language even exists. Despite many an indigenous tribe having their own form of sign language, none ever became the official form of sign language for the United States.

Almost each country have their own form of sign language. No, it is not the same, and language barriers exists for deaf people as well. There was even an invention of an International Sign Language that was used during the Deaf Olympics to help bridge communication issues.

I love sign language. It is the third most widely used language in the United States. First is English, second is Spanish, and third is Sign Language. No, deaf people are not dumb (I honestly hated that old saying and am happy to see it finally phasing out). They can read, write, live independently, work, drive, you name it--there are solutions to each of their problems. Accessible solutions.

Having visible celebrities such as Shoshannah Stern, Marlee Matlin, and so forth help bring attention to such existence. Switched At Birth, a television show, also spotlighted deaf characters. Recently, a movie called CODA, helped spotlight--and it won an award, too.

I continue to be proud of my heritage. I hope to continue to teach my son how to sign--and taught him the most important one.

The one that says "I love you".

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

Guys, the Delaware ACLU is trying to push oralism-first in Deaf education. PLEASE sign this petition to stop that. The U.S. has a bad history with oralism based in eugenics beliefs and attempted cultural genocide. Please help preserve access to American Sign Language for Deaf students in Delaware.

Here's where you can sign the petition.

UPDATE: The Delaware ACLU is reviewing their claim. Their new petition claims that they don't support any form of education that limits access to American Sign Language. They reference the backlash from the Deaf community and the influx of complaints they've received in part of their decision to review the lawsuit. Thanks so much to everyone who signed!

FURTHER UPDATE: The Delaware ACLU has amended their complaint. They now want broader Deaf education for students who can't get to the Delaware School for the Deaf. They also apologize for saying that oral education was the "gold standard". The new complaint argues that ASL is incredibly important for Deaf students, as well. They amended the complaint to say that Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing children in Delaware should have more options when it comes to education.

Community action works! Signing petitions works!

youtube

(Video in American Sign Language with English subtitles)

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

another thing that i just noticed is that the dwarves have now had done to them by the elves what we’d thought the elves had done to them by humans, at least before inquisition. cut down in their peak and permanently ruined, left to scrabble for the broken pieces of their history

not to say it’s an inherently bad choice because oppression isn’t that straightforward, but it sure was an interesting choice to shift the “they destroyed our way of life and fractured our society and we ARE allowing ourselves to feel angry about it and reclaim our history and maybe use that to rebuild what we once had” narrative from the elves to the dwarves. like if that’s the story you really wanted to tell, you could have also given it to like. bellara

#the fall of the titans feels very similar to what we had originally thought the sacking of arlathan was#so there may be more there to uncover. and i dont lnow that i trust them like that again lmao#and it feels especially. i dont want to say insidious but tone deaf at the very least#to shift that from elves (long history of racial coding and marginalization in this series) to dwarves (much less of that)#AND it being told from harding’s POV when she’s not really part of any dwarven society and never has been#feels very much like. white person whose family has been in north america for a few generations reading about european traditions and#trying to incorporate them into their life. anger over how their ancestors were coerced into abandoning their culture to be considered white#so youre left with nothing and are trying to reclaim That. listen it’s also a valid desire i guess but very telling that youre choosing#to tell this story while actively destroying the chance to tell the other kind of story#and also there’s something about how culture doesnt exist in a vacuum#i know some europeans accuse americans of cosplaying their culture and while on one hand that might just be refusal to acknowledge that#culture isnt a monolith and might evolve differently somewhere else. there is a bit of truth to it imo#anyway what im saying is this is absolutely what underground dwarves think of harding#we dont know enough about stalgard#kinda got the impression he was just a guy who lived there rather than part of kal sharok’s government or shaperate#he’s one guy and his opinion doesnt reflect kal sharok. i dont think orzammar is necessarily wrong for not cooperating#they are famously a very closed society and also this is someone from outside that trying to instruct them on their shit#same as when solas tried to ‘’’reason’’’ with the dalish#mine#datv spoilers

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recently learned about the existence of PISL, and the history, reach/use as a lingua franca, and connection to spoken indigenous languages are all fascinating! As with all indigenous languages right now, it is endangered due to the genocidal colonization of this continent.

Full text of the article pasted below the cut.

One summer, when the theatre artist Floyd Favel was in his early 20s, he went to a Sun Dance ceremony in the Qu’Appelle Valley of southern “Saskatchewan.” An Assiniboine Elder from “Montana” spotted him and gestured for him to come over.

Intrigued, Favel did. The Elder made more gestures with his hands. Favel was astounded. “And so I asked him, ‘Do you know that sign language?’ And he said, ‘Yes!’ And I said, ‘Show me some more signs!’ And so he showed me some more signs.”

As a child and young man, Favel, whose first language is Cree, had seen his Deaf grandmother, Philomine Star, make similar gestures. But it was a revelation to him to see an Elder from a different part of the Prairies who was not Deaf use the same motions to communicate.

“Deep down, it opened up a doorway of learning and possibility,” Favel says over Zoom from the Chief Poundmaker Museum, about 200 kilometres northwest of Saskatoon.

In the nearly four decades since, Favel has unearthed a great deal more information about the gestures that both his grandmother and the Assiniboine Elder made. He has also learned the language himself.

It turns out that the signs are part of an ancient lingua franca, or common tongue, used by generations of Indigenous Peoples across the Great Plains area of “North America” to communicate when they did not share a spoken language. This universal sign language, which evolved long before English, French and Spanish colonizers arrived, was a thread that kept far-flung communities linked. Often mobile over long distances, community members needed to share information about trade, buffalo, hunting, food, water, directions, movements, war and even relationships. But because their languages were often so different from each other, Plains Indian Sign Language emerged from these interactions. The language was also used during sacred ceremonies, oratory and storytelling sessions.

It’s likely that at one time, children learned to sign as a second mother tongue, interwoven with spoken language. Once, most Indigenous Peoples in “North America,” whether they were Deaf or not, could communicate with their hands, says Melanie McKay-Cody, a linguist and anthropologist at the University of Arizona. She is one of the world’s few scholars of Indigenous Deaf and North American Indian Sign Languages.

Today, that thread has nearly been severed. Along with so many other Indigenous languages, Plains Indian Sign Language has almost disappeared. Perhaps as few as 1,000 people are fluent in it and many of them are elderly. Some who have held onto the language stumbled onto it by sheer happenstance. For many, the knowledge that the language even existed is more a hazy dream than a certainty, if it is there at all.

“It might be a memory. That would be most of the younger generation. It’s like a collective memory of grandparents,” McKay-Cody, who is Cherokee Deaf, explains over Zoom through an American Sign Language interpreter.

And yet, a fragile movement has emerged not just to recover the long, remarkable history of Plains Indian Sign Language, but to reclaim the language itself. Favel, for example, not only holds yearly workshops to teach it but has also created an original Indigenous theatre method that relies on the language, and he teaches it to international theatre-makers. He dreams that one day, he may be able to coax the language into a cross-cultural symbol of reconciliation.

“I believe in sign language. I believe in it as a vision, as a method, as an art,” he says.

Language is not just words. A language encodes information within itself from the time and place and society in which it emerges. It contains values and ideas. It gives us connection to history, culture and land, to ritual and family. It is our human birthright.

“What would we be without language, as humans? I don’t really know,” says Christopher Hammerly, a professor of linguistics at the University of British Columbia.

Hammerly studies the grammar of his ancestral language Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) as a scientific endeavour. But his subject is much more than an academic enterprise. “I can say from the Ojibwe perspective,” he says, “language is also the way that you communicate with your ancestors … So it also takes on a spiritual dimension in many cases.”

That means losing language is richly symbolic, especially in an era when the threat of other losses is so pervasive, whether it be species, climate certainty or ancient ways of life.

“Lots of diversity is in decline in various ways,” Hammerly says. “And so maybe part of it is, in a very general way, the feeling that the nuance of human experience and culture is at risk.”

Not only that, but the dwindling of Plains Indian Sign Language tracks the larger colonial impulse to eradicate Indigenous knowledge. The language grew precisely because of the connections among different communities. As those communities were torn from each other and from the buffalo that bound them, from trade and from commerce, the language itself faded. And then, as people were driven from their lands and confined to reserves, as children were taken away and oral Indigenous languages fell silent, sign language ebbed even more.

“One woman who lives in northern Montana, she said, ‘You know, sign language was the first to go,’” says McKay-Cody. “That was her quote… And it’s … heartbreaking.”

But how did Plains Indian Sign Language begin? Its history is still being pieced together, says McKay-Cody. She knows that Plains Indian Sign Language was not the only sign language used in past eras — nor is it now. It is, however, unique in being used over such a vast swath of the continent and across so many linguistic families.

According to the classification system McKay-Cody developed, Plains Indian Sign Language is a regional variation of the overarching language family North American Indian Sign Language, also known as Hand Talk. In addition to the regional variations, some communities also have their own tribal sign languages. McKay-Cody, for example, was taught Kiowa, Northern Cheyenne and Crow sign languages and is still learning them as she works with tribal signers.

But long before North American Indian Sign Language evolved, Indigenous Peoples incorporated much earlier versions of signs into rock panels, McKay-Cody has found. She worked with the Colorado-based archeologist Carol Patterson examining rock art. Among other sites, Patterson analyzed symbols likely as many as 1,600 years old at the McConkie Ranch in northeastern Utah. McKay-Cody identified signs, while Patterson determined the age of the art.

On the Zoom call, McKay-Cody demonstrates the rock-art symbol for where to find water: a horizontal line ending in a half-circle. The signed symbol for water is similar: the horizontal line of the forearm ending in a cupped hand. The rock-art symbol for an Elder — the shape of a person with a wiggly stick for a cane — also matches the signed symbol.

Some of the rock panels date back to between about 8,000 and 4,000 years ago, McKay-Cody says. Plains Indian Sign Language evolved at some point after that, but it’s not clear when.

What is clear is that the language is linguistically unusual — and fascinating, says Elaine Gold, director of the Canadian Language Museum at the Glendon campus of York University in “Toronto.” She became aware of the language’s reach a few years ago when the museum put together an exhibit of sign languages used in “Canada.”

Most other species of lingua franca, or languages used to communicate by people who do not share a spoken tongue, are not signed. Some examples: creoles or pidgins. Most have a dominant language that provides most of the vocabulary. For example, Haitian Creole, which, along with French, is now an official language of Haiti, emerged from interactions between enslaved Africans and French colonizers in Saint-Domingue during the 17th and 18th centuries. Such linguistic dominance reflected social hierarchy, Gold says. By contrast, Plains Indian Sign Language has no dominant linguistic influence.

“It’s kind of a meeting of equals,” she says.

Other non-verbal languages tend to be tightly linked to a specific language rather than being a lingua franca, Gold says. For example, the Yorùbá of southwestern Nigeria communicate not just feelings but also Yorùbá words and grammar through a family of different sizes of drums called dùndún. People on the island of La Gomera in the Canary Islands communicate across distances in Spanish through whistles. And, unlike other sign languages, Plains Indian Sign Language was not developed for the Deaf.

Another anomaly? It is not a traditional mother tongue. That means, apart from Deaf people, those who use it, even though they are culturally connected to it, may not have the same deep emotional attachment they have for their own first language.

“It’s easier for these types of languages to slip away,” Gold says.

But its history is long and deep and rich. One of the earliest non-Indigenous references to Plains Indian Sign Language is in accounts from a trip in 1528 by the Spanish colonizer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. He reported that Indigenous Peoples of Tampa Bay used signs and that he was able to communicate by signing during his following eight years of travel through what is now Texas and Mexico — no matter which spoken language he encountered.

That same century, the Spanish colonizers Christopher Columbus and Francisco Vázquez de Coronado also recorded the use of sign language among Indigenous Peoples. By the 19th century, formal scholarship of Plains Indian Sign Language had exploded. Military officers and European anthropologists learned its history from Indigenous Peoples and documented individual signs. Several even created dictionaries.

Many tried to figure out how widespread it had once been. The British anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor wrote in 1865 that the “same signs serve as a medium of converse from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico.” Reports from Canadian government officials before 1879 describe the use of sign language among both the Ktunaxa (Kootenay) and the Séliš (Salish) in “British Columbia.”

In 1881, the American ethnologist Garrick Mallery concluded after much study that Plains Indian Sign Language was at one time a universal language across “North America.” (Others, including McKay-Cody, say it was not that widespread.) The first effort to document the number of signers in the U.S. — McKay-Cody says it was also the last — came in 1890, long after usage peaked. Lewis Hadley, an American missionary, found 102,460 signers in 29 tribes in the Plains area and outside it. (His addition was wrong, McKay-Cody discovered. The actual figure was nearly 111,000.)

Perhaps the most astonishing record of the language is a film made nearly a century ago by Major-General Hugh L. Scott. Scott, then nearing 80, had been the U.S. Army’s chief of staff. He became fascinated with Plains Indian Sign Language. It was, he told a reporter from The New York Times in 1931, “an essential part of the culture of the plains, derived from the buffalo.” Scott studied it, practiced it wherever he could and frequently exchanged coffee and sugar for signing lessons from White Bear, a Cheyenne acquaintance. He even used signs during his wedding ceremony to ensure that Indigenous spectators could understand it.

Alarmed at the language’s swift decline, Scott persuaded Congress to give him US$5,000 (equivalent to about US$120,000 today) and invited chiefs from many tribes to sit in front of a movie camera at a three-day council in 1930 at the Blackfeet Agency in “Browning, Montana.” Eighteen chiefs gathered in headdresses and intricately decorated traditional regalia in a huge tipi, while many other members of their communities gathered off camera. The result is not just vocabulary but an archive of stories, jokes and even wisecracks fluently communicated in Plains Indian Sign Language.

“The sign language of the Plains is filled with poetry, dramatic thought and oratorical fire,” Scott told The Times. He wanted Boy Scouts around the world to learn the language, telling The Times that the language could then have “an even greater career than it had with the plains Indians.” Sir Robert Baden Powell, the Boy Scouts’ founder, endorsed the group’s use of the language as a means of creating cohesion among the troops. The Scouts’ universal salute is adapted from the signs for “wolf” and “scout.” For a time, Plains Indian Sign Language was a requirement for both first-and second-class scouts.

That international attention nearly a century ago helped document the language, says McKay-Cody. But it was also the appropriation of a complex Indigenous tradition for the purpose of training boys to succeed in a colonizers’ world. Modern Boy Scouts no longer learn the language, she says, based on her research.

It may not have been just the Boy Scouts who used signs developed by Indigenous Peoples. McKay-Cody’s research suggests some elements of American Sign Language, the most widely used sign language of the Deaf in “North America,” may have come from an Indigenous sign language she calls Northeast Indian Sign Language. It was used from the eastern seaboard of the continent past the Great Lakes and south, almost to what is now “Florida” and “Texas.”

While history teaches that American Sign Language developed after the educator Thomas Gallaudet brought a French version back from Paris and founded what is now the American School for the Deaf, McKay-Cody points out that French traders had a lot of contact with Indigenous traders in “Canada.”

“If you look back, there is the question of: is this more of a circuitous route? Of the language actually starting in the Northeast from those Indians and then being spread over to France and coming back?” she says. She is involved in research to track how American Sign Language evolved.

Today, though, it’s a race against time to find people who still use any Indigenous sign language. In “Canada,” since 2019 the federal government has formally recognized Plains Indian Sign Language as an Indigenous language, all of which are considered endangered. McKay-Cody wrote in her PhD dissertation in 2019 that the Plains version of sign language is “on the verge of dying.” Most people who use it today are older than 60, McKay-Cody tells me, and some are frail. An Elder who was in her research group died recently — a huge personal as well as linguistic loss.

But every now and then, McKay-Cody is astonished all over again by the secret reach of the language. She tells me about being in an Indigenous grocery store in small-town Montana and realizing that a couple of shoppers were casually chatting it up with their hands.

“I could see them signing to each other, and it was amazing,” she says.

Favel started to focus on Plains Indian Sign Language in 2019. He had spent decades studying and performing theatre, including stints in Denmark and Italy. But he wanted to create an original Indigenous theatre method. Sign language was at its core.

“It gave me a guidance and a light,” he tells me, adding: “Sign language has been the binding tool of a lifetime of theatrical and cultural work and research. Sign language brought it all together.”

It’s woven into his artistic practice in multiple ways and for many reasons. In one example, he uses a signed story as the central image of a play, and his students build the dramaturgy and choreography around it. He has built a stage that is a physical manifestation of his Indigenous worldview. The ideas underpinning the language are pre-colonial, formed long before settlers arrived.

“Sign language is a spirit-given way of communication,” he says. “That’s how we got our culture was through our stories and myths and through dreams and visions and communication.”

The language is also intimately connected with Cree, Favel’s mother tongue, and other Indigenous languages because it evolved with them. But they are intrinsically differently constructed than English. “This is an Indigenous way that is very different from English. How we compose our internal images and verbs is very different,” Favel says.

For example, Cree is a verb-based language that describes how and when a person did something, Favel explains. But the order of the words is interchangeable. In fact, the art of the Cree language is in putting sentences together in an original way. Modern methods of teaching language are based on English, the tongue of the settlers, which organizes grammar differently. That makes it difficult to teach Cree — and revitalize it.

Favel’s insight was to realize that spoken Cree is also roughly half sign and gesture. So, learning Plains Indian Sign Language, in which every sign is accompanied by movement, is a shorthand way to learn Cree.

“By reviving sign language, you are doing a cultural healing, because now you’re making it okay for people to express themselves, gesture, move, sign,” Favel says. “You are giving them permission to move their bodies and their hands and to revive 50 per cent of Cree language.”

He turned for advice to Lanny Real Bird, a Crow Elder who lives on the Crow Agency in “Montana” and is one of the few people fluent in Plains sign language.

When Real Bird was a child, sign language was common among Crow Elders, he tells me over the phone. He used to watch signers and memorize their motions, building vocabulary. An uncle taught him how to communicate with signs when they were hunting and needed to be silent, and how to use signs as they prepared for ceremonies.

But it was only when he was a preteen at regional powwows and rodeos that he realized people in other communities with many other spoken languages used signs, too. He started asking questions and came to realize the signs formed an international language embodying Indigenous spiritual teachings.

“This language is beautiful because it has a lot to do with the environment,” he says. “It has a lot to do with how we view the world, how we appreciate nature, how we understand the universe, how we interpret the meaning of the water and wind and fires and the earth.”

Eventually, Real Bird, who has a doctorate in education, began making an illustrated book of the language and teaching others, both Deaf and hearing. Like Favel, he uses sign language to teach others his own mother tongue, Crow. His YouTube channel has 13 videos and more than 900 subscribers. He’s become one of the most prominent teachers of Plains Indian Sign Language in the world, teaching in schools in “Montana” and “North Dakota.”

Recently, Real Bird walked into the lunchroom of a school in “North Dakota.” Thirty students turned to look at him, and 10, recognizing him from the videos, began signing to him. It was inspiring. But despite his efforts, and despite a “North American” movement aimed at revitalizing Indigenous languages, the use of sign language is dropping off in his community as Elders die, he says.

Favel has made it his task to reverse those losses. He presents university lectures and webinars on the language. And for the past five summers, he has held four-day Plains Indian Sign Language workshops at the Poundmaker Performance Festival at Poundmaker Cree First Nation in “Saskatchewan” as part of his Indigenous performance method. He says his is the only consistent workshop in North America to offer instruction in the language. Real Bird teaches the classes. They are open to all.

Participants learn between 40 and 100 signs in the four days, depending on their interest. Favel says a person who knows 500 signs can carry on a functional conversation, Indigenous or not, Deaf or hearing.

He has bold dreams. What if non-Indigenous people could actively communicate with Indigenous people using Plains Indian Sign Language? If it takes off, he says, it could open new doors, not just to language but to something even more profound.

“It verges into movement, communication, intuition, dance, openness and trust. Because that’s what you need in a sign language…. You must always be listening with your eyes [to] that person’s face and hands and body — so you’re truly engaged with them. It offers us a way of communication that goes beyond existing structures.”

It is, he says, nothing less than entering the ancient Indigenous worldview, unscarred by the bias encoded in the language of colonizers.

#pisl#plain indian sign language#indigenous#indigenous languages#endangered languages#indigenous history#linguistics#sign language#sign#Deaf#indiginews#indigineous people#native american#native people

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

Happy Deaf History month!!! (April)

There are a few important hallmark dates celebrated every year by Deaf communities in April.

National ASL Day

Celebrated on April 15, the day in history when American School for the Deaf was founded in Hartford, Connecticut in 1817.

learn more about ASD here: American School for the Deaf

Here are some great presenters briefly explaining different aspects of ASL. (with closed captions for non-signers)

youtube

Deaf LGBTQ+ week

Celebrated in the second and third weeks of April, usually alternating dates, with many events and celebrations to highlight the rich heritage of Deaf queer people everywhere. (has closed captions for non-signers)

youtube

Also, April 8 is noted, as it is the day in 1864 when Gallaudet University, the only university in the world specifically for deaf and hard-of-hearing students, was chartered.

Lastly, I should say that even though this is not (NOT) a post for sharing resources to learn ASL, I did want to add one final part which specifically relates to Deaf culture, & how to interact respectfully with deaf and hard-of-hearing people. It’s by Chrissy from The Essential Sign:

youtube

(and yes, you guessed it, does have CC for non-signers. 😉)

Happy Deaf History month!

#deaf#hard of hearing#deaf culture#deaf community#deaf history month#deaf history month 2023#deaf history#deaf queer#deaf lgbtq#deaf lgbtqia#asl#american sign language#sign language#deaf pride#closed captions

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

9/11 birthdays are rlly something else in that I remember this one time my sister told me when she was in kindergarten her teacher said smth like “today is a very important day, I don’t expect any of you to know this but does anyone know the reason?” And she raised her hand and excitedly said “It’s my sister’s birthday!!”

#9/11#9/11 birthday#rambling#I’m not even American so that’s interesting#well#I’m Canadian though which is still p close geographically and history-wise#hopefully this isn’t tone deaf#it really was a tragic loss of life#and also tragic how ppl still today are the target of racism bc of it#just thought I’d share a funny awkward story

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

if ur putting antin*t*list shit on my dashboard while Palestinians are going thru a literal genocide i will wish endless skinnings to u and urs. i dont rock with that shit.

#im so fucking sick and tired of white ppl having their 'innocent' opinions on the existence of human#life. could not be more fucking tone deaf rn#if u dont wanna have kids thats great. i dont either.#to not even consider what’s going on in the actual world OF suffering.#and to plague this morning with ur ‘optimism’ abt how to stop child suffering is for ppl not to be born?#instead of i dont fucking know u daft american cunt. looking at our systems? looking at our inflictions on our own ppl and others??#to suggest and fucking yap about how dear children are to u and to draw an obvious line#on who u actually care about: the ones Not suffering. the obvious ones who have all the resources in the world to#show ur pure heart they can raise the perfect unharmed child? fuck off#im not saying everything perfectly but i just believe there is some insidious ignorance in those that believe there is innocence in#elimination#that ignorance of Actual Peoples from history of great suffering will crush you tenfold for what little u think of life#and life as an applicant to only those who Dont Have It Bad#fuck off

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the last four days I have been staring at The Other Side of Silence, a book I have been wanting to read since I got it and my brain keeps going "no. Not today. Stars, can't do it" and like breh I just want to read about deaf education in America ok.

#winters ramblings#i gotta find myself some canadian centric stuff i read too much shit about America lmao. but also America is Very Loud#and canada is less so. also American history is FASCINATING im literally watching a video on Iran Contra as i type#but also ive watched or listened to a couple podcasts/ vids on koko the gorilla and the book talks about that#and how fucked up it is hearing people were stoked about a GORILLA using sign while ACTIVELY FORCING DEAF KIDS NOT TO SIGN#because yeah that IS fucked up tell me more

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond Just Hand Gestures

Discover the vibrant world of Deaf culture and the rich language of sign language in our latest post, a journey into the heart of a unique and diverse community.

Exploring the Depths of Sign Language Introduction The Multidimensional Nature of Sign Language Hand Gestures: The Foundation Facial Expressions: The Emotional Context Body Language: The Supporting Pillar The Diversity of Sign Languages The Role of Culture in Sign Language Technology and Sign Language Conclusion Summary Further Reading Book Recommendations Featured…

View On WordPress

#Accessibility#American Sign Language (ASL)#Behavioral Norms#Communication Rights#Community Engagement#Cultural Identity#Cultural Values#Deaf Community#Deaf Culture#Deaf History#Educational Resources#Human Rights#Inclusion#Inclusivity in Society#language preservation#linguistic diversity#Non-Verbal Communication#Sign Language#Social Norms#Visual Language

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can I PLEASE find the people who agree with me when I say Alexander Graham Bell is a meanie pants (understatement)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

being on this website right now is just like im being so brave by blacklisting the tags for a new movie thats very popular right now and not responding to any of the gifsets i still see of it with what is rightful criticism of it for being tone-deaf

#kai rambles#i just think that if the premise of you book/movie is that steeped in politics#you have to engage with them rather than kicking it under the rug and pushing it into another room#especially the queer history of both countries in relation to politics and one specific institution if it is a gay love story#and the political institutions in both countries are catalysts or components of the plot#if youre not going to actually engage with it and explore it in relation to your romance why is it even in your book?#its justa magnet on a fridge to make it look unique#and since its a gay romance its intrinsically linked to the politics you are not engaging with#gay marriage is not codified in law in america#and like maybe its being a queer brit who has spoken to people who arent terminally online baby gays#but i think its so fucking tone-deaf and honestly a little offensive to write a gay romance where one of them is a royal without#even mentioning princess fucking diana#you know the one who was post-humously honoured as a queer icon because of all the work she did surrounding aids#whete she famously held hands with an aids patient when most people didnt even want to go near them#where she set up trusts and charities and led campaigns to fund research into a treatment#where the queen didnt fucking support her and suggested she choose ''something more pleasant''#she is a queer icon in britain and the royal family treated her like fucking shit and probably had her killed#like i get that the author is american and might not know about it butidk casey you could do some fucking research#i honestly think its disgusting to write a queer story about a british royal without even mentioning her and the impact she had

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think I'm losing my mind. I swear I saw several sources say that the Congress of Milan didn't apply to religious education but I can no longer find those sources.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

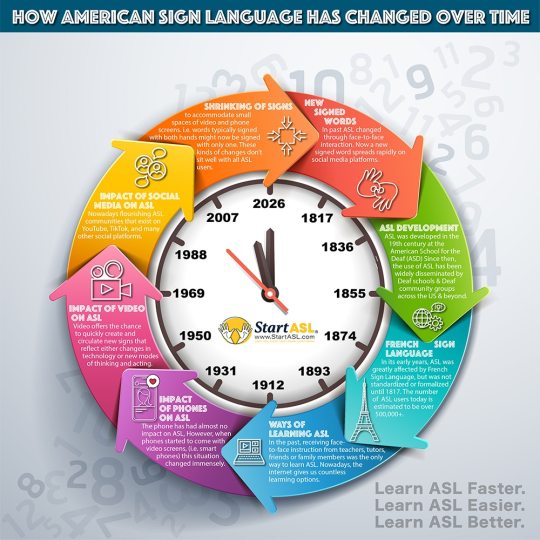

How American Sign Language has Evolved Over Time

During the past decades, American Sign Language transformed mainly by means of face-to-face interaction. Yet presently, a whole new signed word can easily spread out like wildfire on social media platforms like YouTube or TikTok.

This article examines the transformations occurring in ASL, largely attributed to the extensive use of smartphones and video technology. As a result of these advancements, there has been a substantial increase in American Sign Language communications.

Early Development Stages of American Sign Language

American Sign Language was developed in the early 19th century at the American School for the Deaf (ASD) in West Hartford, Connecticut, through language connection with English. Ever since then, the usage of ASL has been widely disseminated by Deaf schools and Deaf community groups throughout the United States and beyond.

During its initial stages, French Sign Language significantly affected American Sign Language, but it wasn't formalized or standardized right up until 1817. The volume of ASL users these days is estimated at 500,000, but it might be a lot higher.

Methods of Learning ASL Now Versus Before

During the past decades, receiving face-to-face instruction from educators, tutors, close friends, or relatives was practically the only way to learn ASL. But in the present day, many method of learning the language are readily available, such as the following.

Participating in a face-to-face classroom setting

Enrolling in an internet based virtual course

Acquiring knowledge through online video tutorials

Signing up for a Deaf club or an ASL group

Visiting a Deaf café

Getting a personal tutor

Watching and mimicking interpreters

Utilizing an educational application and

Being taught by Deaf family members or friends

Regardless of what method of learning ASL you choose, it is necessary to have fun and work together frequently with many other ASL users. This process will speed up your language procurement and facilitate your access to the D/HoH community.

Impact of Phones on ASL

The cell phone has brought a considerably less remarkable impact on American Sign Language. Then again, when mobile phones began to feature video displays (i.e. smartphones),this situation changed immensely.

Impact of Video Technology on ASL

Video technology has empowered ASL users to connect more easily and teach the language to lots more people. It also increases the possiblity to rapidly create and circulate brand new signs that reflect either modifications in technology or completely new modes of acting and thinking.

Influence of Social Media on ASL

These days, thriving ASL communities can be found on YouTube, TikTok, and various other social media networks.

The Current State of American Sign Language

Shrinking of Signs

To fit the small spaces of video and cell phone screens, words usually signed with both hands might currently be signed with just one. These particular kinds of changes only sit well with some ASL users.

New Signed Words

In earlier times, ASL evolved through face-to-face interaction. Now, a whole new signed word spreads rapidly on social networking platforms.

Preserving American Sign Language

Whatever issues might develop as ASL grows, preserving the language for future generations is vital. Doing this can help to safeguard Deaf culture and ensure that Deaf/HoH people have access to their method of self-expression and communication in the decades to come.

youtube

#American Sign Language#American Sign Language education#ASL history#asl#deaf#deaf community#learn american sign language#learn asl#learn asl online#learn sign language#sign language#Sign Language Class#Sign Language Classes#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poetry, Pastries, & Pies: The Signs of Poetry Podcast

Poetry, Pastries, & Pies: The Signs of Poetry Podcast #ASL #SignLanguage #DeafCommunity #PodcastCommunity #DeafCulture #Poetry #PoetryCommunity

Image Credit: Kym Gordon Moore What is it like to watch mouths move as conversations abound with emotion that only facial expressions and hand gestures can reveal? Can we still speak when we cannot hear or utter a word? Of course, we can. Communication is universal regardless of what language you speak or what form of engagement you use. National Deaf History Month runs annually from March 13 to…

View On WordPress

#American Sign Language#Deaf Awareness#Deaf Community#Deaf Culture#Deaf Poets#Hearing Loss#National Deaf History Month#Podcast#Podcast Community#Poetry

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

All this over a damn cardigan. It’s why I don’t take the vast amount of online activists seriously

#it’s not tone deaf#it’s tone deaf for white folks to be saying this is the worst week in American history- protections are just now rolled back on white people#it’s a damn cardigan for Valentine’s Day#no she shouldn’t have to donate cardigan profits and if she did I’m pretty sure ppl would call it rainbow washing#god forbid people have something to be happy about#I’m not saying all online activism is pointless but I think a lot is performative now#especially when it comes from very privileged groups and this election is further proof#Americans also aren’t the only fans

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tone deaf, 'a state of death and destruction' bruh we know the administration is the one making these decisions, but now you want to villainise a whole state. You are not helping the situation

A reminder. It's a state of death and destruction.

#this is so tone deaf#come after russias administration causing ll this shit#but if you're going after an entire country#which does not really control their admin cause of russias political system#just dump on a whole nations history like that#americans and western europe are so good at villainising whole groups instead of the singular cause#this shit is about Putin and his legacy#come after all of russian culture#its just not intelligent politics man#fucks sake and all the sanctions being placed on my country rn#south africa#like man we did not ask our admin to make those choices#the west wants south africa to arrest Putin regardless of how his admin could fuck us over for breaking the BRICS alliance like that#and how china could do us dirty for that choice as well#do you know how many deals South Africa has riding on china

387 notes

·

View notes