#American 🇺🇸 History

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Twenty-Five Years Before The Wright Brothers Took To The Skies, This Flying Machine Captivated America

First Exhibited in 1878, Charles F. Ritchel’s Dirigible Was About As Wacky, Dangerous and Impractical as Any Airship Ever Launched

— June 11, 2024 | Erik Ofgang

“When I Was Making It, People Laughed at Me a Good Deal,” Charles F. Ritchel Later Said. “But Do They Did at Noah When He Built the Ark.” Illustration by Meilan Solly/Images via Wikimedia Commons under public domain, Newspapers.com

Charles F. Ritchel’s Flying Machine Made a Sound Like a Buzzsaw as its pilot turned a hand crank to spin its propeller. It was June 12, 1878, and a huge crowd, by some accounts measuring in the thousands, had gathered at a baseball field in Hartford, Connecticut. The spectators had each paid 15 cents for a chance to witness history.

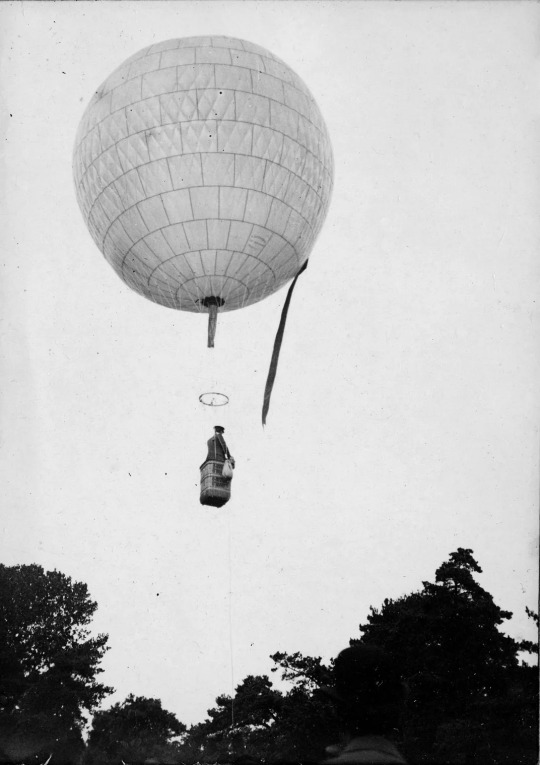

The flying machine—if one could really call it that—was an unsightly jumble of mechanical parts. It consisted of a 25-foot-long, 12-foot-wide canvas cylinder filled with hydrogen and bound to a rod. From this contraption hung a framework of steel and brass rods that the Philadelphia Times likened to “the skeleton of a boat.” The aeronaut would sit on this framework as though it were a bicycle, controlling the craft with foot pedals and a hand crank that turned a four-bladed propeller.

The device did not inspire confidence.

“When I was making it, people laughed at me a good deal,” Ritchel later said. “But so they did at Noah when he built the ark.”

A self-described “professor,” Ritchel was the inventor of such wacky, weird and wild creations that a recounting of his career reads as though it were torn from the pages of a Jules Verne novel. Supposedly friends with both P.T. Barnum and Thomas Edison, Ritchel for a time made a living working for a mechanical toy company in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where he designed talking dolls, model trains and other playthings. But he was more than just a toymaker.

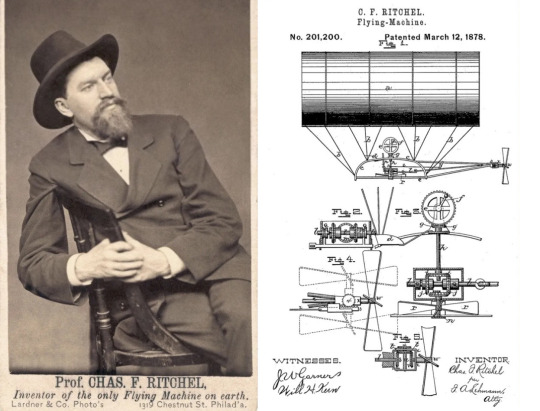

Left: Charles F. Ritchel filed more than 150 patents over his lifetime. Right: Ritchel's 1878 patent for his flying machine — Photographs: Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

Some years after the flying machine demonstration, the inventor proposed an ambitious attraction for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World’s Fair): a “telescope tower” that would rival France’s Eiffel Tower. The design consisted of a 500-foot-wide base topped by multiple nested structures that rose up over the course of several hours, eventually reaching a height of about 1,000 feet. After this proposal was rejected, Ritchel launched a campaign to raise funds to build a life-size automaton of Christopher Columbus, which the Chicago Tribune reported would speak more than 1,000 phrases in a human-like voice, rather than the “far-away, metallic sounds produced by a phonograph.”

By the mid-1880s, Ritchel claimed to have filed more than 150 patents. Not all of them were fun. He invented more efficient ways to kill mosquitos and cockroaches, a James Bond-esque belt that assassins could use to inject poison into their targets, and a gas bomb for use in land or naval warfare.

Yet never in his career was his quirk-forward blend of genius and foolishness more apparent than on that June day in Hartford. Because the balance of weight and equipment was so delicate, Ritchel was too heavy to fly the craft. Instead, he employed pilot Mark W. Quinlan, who tipped the scale at just 96 pounds. Quinlan was a 27-year-old machinist and native of Philadelphia, but little else is known about him. The record, however, is crystal clear on one count: Quinlan was very, very brave.

When preparations for the craft were complete, the crowd watched in eager anticipation as Quinlan boarded the so-called pilot’s seat. The airship rose 50 feet, then 100 feet, then 200 feet. Such a sight was uncommon but not unheard of at the time. The real question was: Once the craft was in the air, could it be controlled?

The first heavier-than-air flight (in which airflow over a surface like a plane wing creates aerodynamic lift) only took place in 1903, when the Wright Brothers conducted their famous flight in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. But by the late 19th century, flying via lighter-than-air gases was already close to 100 years old. (This method involves heating the air inside of a balloon to make it less dense, leading it to rise, or filling the balloon with a low-density gas such as helium or hydrogen.) On November 21, 1783, Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent d’Arlandes completed the first crewed, untethered hot-air balloon flight, passing over Paris on a craft built by the Montgolfier brothers. Later, balloons were used for reconnaissance during the French Revolutionary Wars and the American Civil War.

A drawing of the Montgolfier brothers' hot-air balloon Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

But free-floating balloons were, and still are, at the mercy of the winds. While balloon aeronauts can achieve limited control by changing altitude and attempting to catch different currents, they can’t easily return to the spot where they took off from, which is why even today, they have teams following them on the ground. Mid-1800s aviation enthusiasts dreamed of fixing this problem, which led to the development of dirigibles—powered, steerable airships that were inflated with lighter-than-air gases. (The word dirigible comes from the French word diriger, “to steer”; contrary to popular belief, the term, which is synonymous with airship, is not derived from the word “rigid.”) While some early aeronauts successfully steered dirigibles, none of these rudimentary airships could truly go against the wind or provide a controlled-enough flight to take off and land at the same point consistently.

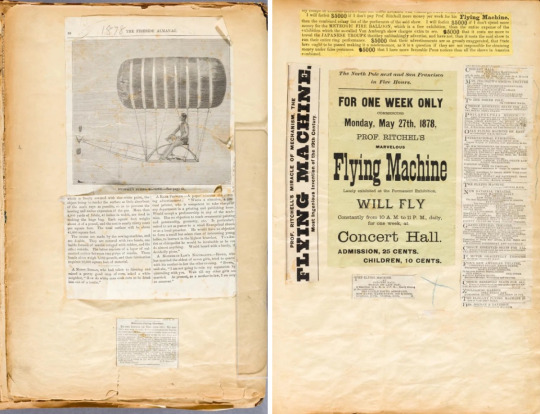

In 1878, Ritchel was unaware of anyone who had successfully taken off in a dirigible and landed at the same spot. He hoped to change that with his baseball field demonstration. A month earlier, Ritchel had exhibited the airship’s capabilities during indoor flights at the Philadelphia Main Exhibition Hall, a massive structure built for that city’s 1876 Centennial Exposition. But there is no wind indoors, and the true test of his device would have to be performed outdoors.

After rising into the air, Quinlan managed to steer the craft out over the Connecticut River. To onlookers, it was clear that the aeronaut was in control. But as he flew, the wind picked up, and it began to look like a storm was gathering. To avoid getting caught in the poor weather and facing an almost-certain disaster, Quinlan steered the craft back toward the field, cutting through the “teeth of the wind until directly over the ball ground whence it had ascended, and then alighted within a few feet of the point from which it had started,” as the New York Sun reported.

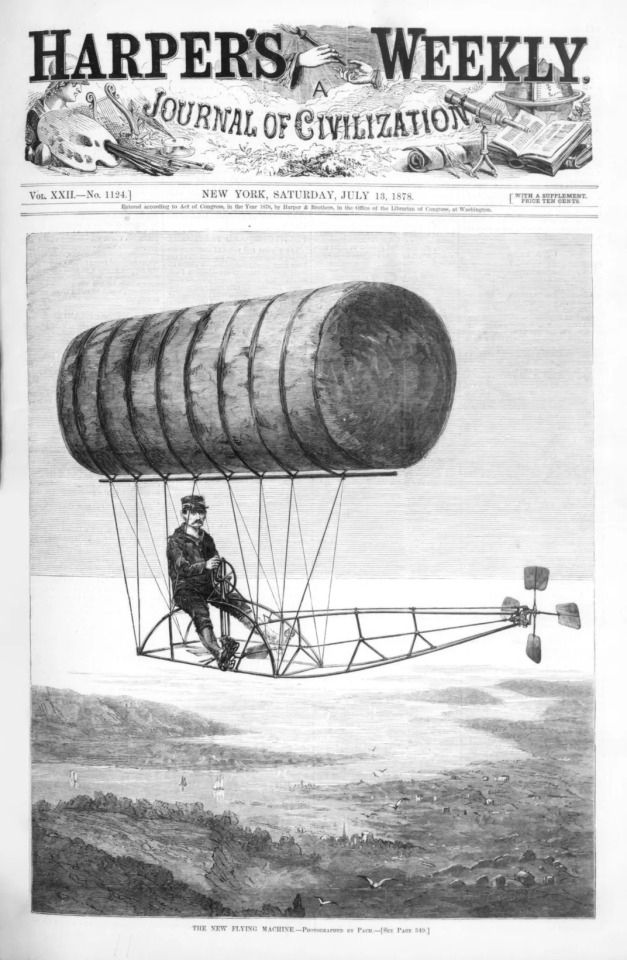

Ritchel's dirigible, as seen on the July 13, 1878, cover of Harper's Weekly Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

The act was hailed far and wide as a milestone. An illustration of the impressive-looking flying machine was featured on the cover of Harper’s Weekly.

“The great problem which inventors of flying machines have always before them is the arrangement by which they shall be able to propel their frail vessels in the face of an adverse current,” the magazine noted. “Until this end shall have been achieved, there will be little practical value to any invention of the kind. In Professor Ritchel’s machine, however, the difficulty has been in a great measure overcome.”

Across the country, observers hailed Ritchel’s odd but impressive milestone in flight. In the years and decades that followed, this achievement was forgotten by almost all except a select group of aviation historians.

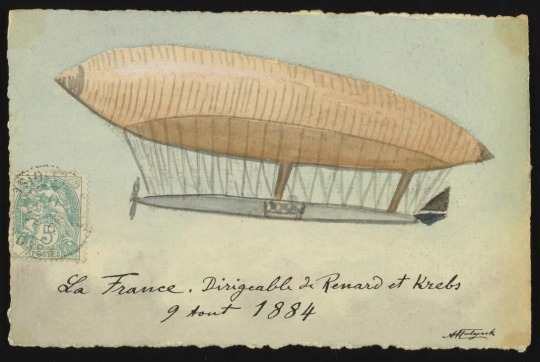

Wikipedia incorrectly lists the flight of the French army dirigible La France as the first roundtrip dirigible flight. But this event took place six years after Ritchel’s Hartford demonstration, in August 1884. Why has a flight so seemingly monumental in its time been relegated to the dustbin of history?

Given his eccentric nature and creativity, it’s easy to root for Ritchel and think of him as a Nikola Tesla-like genius robbed of his rightful place in history. The reality of why his feat was forgotten is more complicated. As Tom Crouch, an emeritus curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, says, it’s possible Ritchel’s craft was the first to complete a round-trip dirigible flight. But other aircraft in existence at the time probably could have accomplished the same feat in favorable conditions. “La France made the first serious round-trip,” Crouch says.

Additionally, while Ritchel’s machine worked to a point, it wasn’t a pathway to more advanced dirigibles. Richard DeLuca, author of Paved Roads & Public Money: Connecticut Transportation in the Age of Internal Combustion, points out that the hand-cranked nature of Ritchel’s craft made it nearly impossible to operate with any kind of wind. “On the first day, he got away with it and directed the ship out and over the river and back to where he started, and that was quite an accomplishment,” DeLuca says. “But the conditions were just right for him to do that.”

Dan Grossman, an aviation historian at the University of Washington, has never come across evidence that any later pioneers of more advanced dirigible flights were influenced by Ritchel. “There are a lot of firsts in history that got forgotten because they never led to a second,” Grossman says.

An artist's depiction of the La France airship Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

The day after their first successful public outdoor flight in Hartford, Quinlan and Ritchel tried again at that same ballfield. This time, the weather was less cooperative, and the wind came in sharp gusts. Still, the pair persisted in their attempt. “Little Quinlan, even if he does only weigh 96 pounds, has confidence and nerve enough to go up in a gale,” the Sun reported. Up he went about 200 feet, but this time, the wind carried him away with more force. Quinlan was “seen throwing his vertical fan into gear, and by its aid, the aerial ship turned around, pointing its head in whatever direction he chose to give it.” Although he could move the ship about, “he could not make any headway against the strong wind.”

Quinlan descended about 100 feet, trying to catch a different current, but the wind still pushed him away from the ballfield. He raised the craft, this time going higher than 200 feet, but still couldn’t overcome the wind and was soon swept off toward New Haven, vanishing from sight like some real-world Wizard of Oz.

Eventually, Quinlan safely brought the airship down in Newington, about five miles away from Hartford. The inventor and his pilot were unfazed by this setback. They held more public exhibitions that year with a mix of success and failure—including an incident that nearly cost Quinlan his life. During a July 4 exhibition in Boston, the machine malfunctioned and continued to rise, soaring to what the Boston Globe estimated to be 2,000 feet. Quinlan couldn’t get the propeller to work, and the craft continued to rise, reaching as high as 3,000 feet.

youtube

Terrified but quick-thinking, Quinlan tied his wrist and ankle to the craft and swung out of his seat to fix the propeller, using a jack-knife he happened to have on him as a makeshift tool. The daring midair repairs worked, and the craft gradually descended. Quinlan landed in Massachusetts, 44 miles from his starting destination, after a 1-hour, 20-minute flight.

Per Grossman, the human-powered method Ritchel attempted to utilize was doomed from the start. “In the absence of an internal combustion engine, there really was no control of lighter-than-air flight,” he says.

Ritchel stubbornly refused to consider powering dirigibles with engines and did not foresee how powerful a better-designed aircraft truly could be.

“I have overcome the fatal objection of which has always been made to the practicability of aerial navigation—that is, I have made a machine that can be steered,” Ritchel told a reporter in July 1878. “I claim no more. I have never pretended that a balloon can be made to go against the wind, and I am sure it never could. It is as ridiculous as a perpetual motion machine, and the latter will be invented just as soon as the former.”

Left: A page from Ritchel's ballooning scrapbook National Air and Space Museum Archives. Right: The scrapbook covers the years 1878 to 1901. Photographs: National Air and Space Museum Archives

Even so, Ritchel was influential in his own way. “He was one of the first to really come up with the notion of a little one-man, bicycle-powered airship, and those things were around into the early 20th century,” says Crouch. After Ritchel, other daring inventors launched similar pedal-powered airships. Carl Myers, for example, held demonstrations of a device he called the “Sky-Cycle” in the 1890s.

Ritchel stands as one of the fascinating early aeronauts whose work blurred the line between science and the sideshow. “I refer to them as aerial showmen, these guys who came up with the notion of making money [by] thrilling people [with] their exploits in the air,” Crouch says.

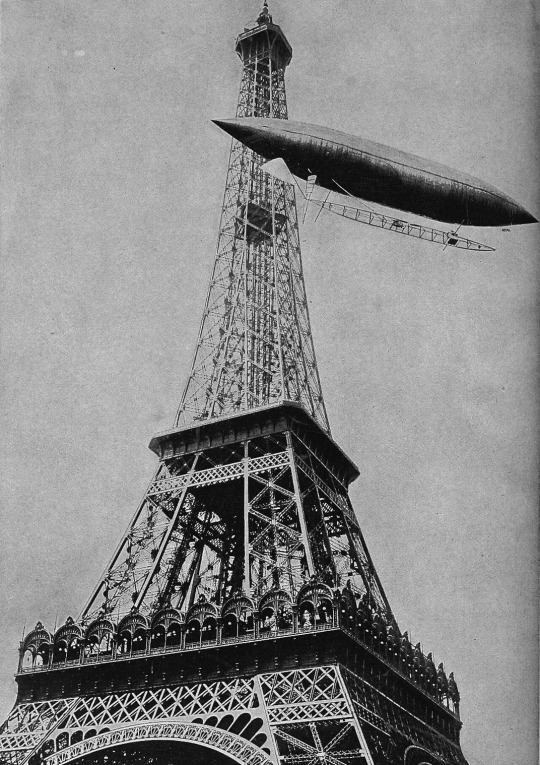

According to Crouch’s 1983 book, The Eagle Aloft: Two Centuries of the Balloon in America, Ritchel and Quinlan took the airship on tour with a traveling circus in the late 1870s. Ritchel also operated his machine at Brighton Beach near Coney Island. He sold a few replicas of his device and later attempted to develop a larger, long-distance version of the craft powered by an 11-person hand-cranking crew. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this idea failed to gain momentum, and Ritchel faded from the headlines. Soon, the exploits of new aeronauts would upstage him, among them Alberto Santos-Dumont’s circumnavigation of the Eiffel Tower in 1901.

Left: Alberto Santos-Dumont's first balloon, 1898. Right: Santos-Dumont circles the Eiffel Tower in an airship on July 13, 1901. Photographs: Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

Despite many earlier dirigible flights, Crouch and Grossman agree that the technology only became practical when German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin built and flew the first rigid dirigible in the early 1900s. Over the first decade of the new century, Zeppelin perfected his namesake design, which featured a fabric-covered metal frame that enclosed numerous gasbags. “By 1913, just before [World War I] begins, Zeppelin is actually running sightseeing tours over German cities,” Crouch says, “so the Zeppelin at that point can safely carry passengers and take off and land from the same point.”

For a brief period, airships ruled the sky. (The spire of New York City’s Empire State Building, built in the 1930s, was famously intended as a docking station for passenger airships.) But the vehicles, which use gas to create buoyancy, were quickly eclipsed by airplanes, which achieve flight through propulsion that generates airflow over the craft’s wings.

While the 1937 Hindenburg disaster is often viewed as the end of the dirigible era, Grossman says that’s a misconception: The real death knell for passenger airships arrived when Pan American Airways’ China Clipper, a new breed of amphibious aircraft, flew from San Francisco to Manila in November 1935. “Partly because they flew faster, they could transport more weight, whether it’s people or cargo, mail, whatever, in the same amount of time,” Grossman explains. “They were less expensive to operate, they required much, much smaller crews, [and] they were less expensive to build.”

Airplanes were also safer. “Zeppelins have to fly low and slow,” Crouch says. “They operate in the weather; airplanes don’t. An airplane at 30,000 feet is flying above the weather. Weather, time after time, is what brought dirigibles down.”

Today, niche applications for passenger airships endure, including the Zeppelin company’s European tours, as well as ultra-luxury air yachts and air cruises. But “it’s always going to be a tiny, tiny slice of the transportation pie,” Grossman says.

Crouch agrees. “People still talk about bringing back big, rigid airships. That hasn’t happened yet, and I don’t think it will,” he says.

The USS Los Angeles, a United States Navy airship, in 1931. Photograph Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

In some ways, Ritchel’s flying machine was a microcosm of the larger history of dirigibles: fascinating, fun and the perfect fodder for fiction, but ultimately eclipsed by more efficient technology.

As for Ritchel, he died, penniless, of pneumonia in 1911 at age 66. “Although during his lifetime he had perfected inventions that, in the hands of others, had brought in great wealth, he died a poor man, as he lacked the business ability to turn the children of his brain to the best advantage to himself,” wrote the Bridgeport Post in his obituary.

Even so, the public had not forgotten the brief time three decades earlier when Ritchel and his airship ruled the skies. As the Boston Evening Transcript reported, his flights captured “the attention of the world. In every country and in every language, newspapers and magazines of the day printed long stories of the wonderful feats performed by the Bridgeport aviator and his marvelous machine, of which nothing short of a cruise to the North Pole was expected.”

— Erik Ofgang is the co-author of The Good Vices: From Beer to Sex, The Surprising Truth About What’s Actually Good For You and the author of Buzzed: A Guide to New England's Best Craft Beverages and Gillette Castle: A History. His work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Atlantic, Thrillist and the Associated Press, and he is the senior writer at Tech & Learning magazine.

#Youtube#Air & Space Museum#Air Transportation#Airplanes ✈️ ✈️ ✈️#American 🇺🇸 History#Invention#Newspapers 📰 🗞️#Smithsonian Institution#Toys#Transportation#Wright Brothers#Flying Machine#Charles F. Ritchel#Airship#Professor Charles F. Ritchel#Inventer of the Only Flying Machine on Earth 🌎#Lardner & Co | 1319 Chestnut Street | Philadelphia | Pennsylvania

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering Malcolm X on the anniversary of his assassination

#n.e.w.s. brand#n.e.w.s.#n.e.w.s#news brand 88#n.e.w.s.brand#malcolm x#malik shabazz#el hajj malik el shabazz#Malcolm Little#anniversary#assassination#detroit red#2025#winter#winter solstice#88#black excellence#black people#black history month#black history#fba#foundational black american#foundational#black american#america#🇺🇸

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

1978 Dodge Trucks 🇺🇸

#dodge#american 🇺🇸#american legend#american history#road warriors#auto show#merry chrysler#plymouth#pick up#dodge truck#i#off road

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

I cried my eyes out when I saw this 😭😭😭

It's almost too much 💔

The world does look away and not care what was done to the Jewish people on Oct 7th.

Their eyes and hearts are closed or hardened and they can't feel anything but hate .

They side with savages who sexually assaulted, murdered,kidnapped innocent men women and children!

It absolutely makes me sick to my stomach 🤮

So called " innocent 'civilians celebrating their deaths like psychopaths .

Disgusting!

I don't have posts sympathizing with gazans and Palestinians..

No way !

I won't sympathize with people who took part on Oct 7th with Hamas or the gazans who held them hostage .

Who celebrated 🎉 the murder of two innocent children and Holocaust victims ,not to mention the sexual assaults .

I side with Israel and I hope Israel gets Gaza back .

It belongs to the Jewish people!

Not America not Hamas or Gazans who took part on Oct 7th massacre !

The Jewish people

PERIOD!

#jewish history#jewish roots#israel#gaza#palestine#🇮🇱💙🫂#israel you are not alone !#many Americans love you and support you#🇺🇸❤️🫂🇮🇱💙#i am sorry 😔#hamas#oct 7 2023#never forget

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

#hebrew#jewish life#jewish people#jewish history#jewish heritage#israel#jewish nation#true americans support israel#🇺🇸❤️🇮🇱💙

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

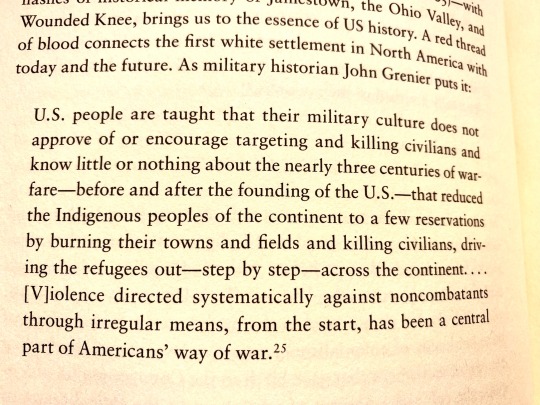

“U.S. people are taught that their military culture does not approve of or encourage targeting and killing civilians and know little or nothing about the nearly three centuries of war-fare-before and after the founding of the U.S.-that reduced the Indigenous peoples of the continent to a few reservations by burning their towns and fields and killing civilians, driving the refugees out--step by step--across the continent....Violence directed systematically against noncombatants through irregular means, from the start, has been a central part of Americans' way of war. “

Military Historian John Grenier

Excerpt from Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s book:

An Indigenous People’s History of the United States

#us history#wounded knee#sand creek#trail of tears#the long walk#bear river#thanks taking#in Country#🇺🇸#land back#crazy horse#tecumseh#sitting bull#Geronimo#chief joseph#emiliano zapata#Joaquin murrieta#Pó Pay#captain Jack#war crimes#enthic cleansing#Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz#american history

283 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Kennedy Layouts

﹑ 𓏵 ﹒ f2u ﹒+ creds aren't needed ◞ 🇺🇸

#🌷੭ layouts#edit#free to reblog#sfw post#john f kennedy#usa#usa news#usa network#usa national team#usa nt#usa politics#usa president#usa people#usa history#us presidents#presidential debate#🇺🇸#usa 🇺🇸#united states#united states of america#🦅#raaahhh#rahhhh 🦅#🗽#america#american#60s#he's an icon#twitter layout#layout

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lindsay Lohan (American, born July 2, 1986).

Series I, White and Blue Flower Shapes, between 1919 and 1920. Georgia O'Keeffe (American, 1887-1986).

#lindsay lohan#georgia o'keeffe#flower painting#modernist art#fangledeities#woman painter#art history#🇺🇸 painter#american actress#american actor

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE BIRTH OF THE MODERN BULL DYKE? LOL! AN AMERICANA MASTERPIECE, NONETHELESS.

PIC INFO: Resolution at 1512x2000 -- Spotlight on "Rosie the Riveter" oil on canvas painting by American master, Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), first published as cover art to the "Saturday Evening Post" on May 29, 1943.

OVERVIEW: "Norman Rockwell's "Rosie the Riveter" received mass distribution on the cover of the "Saturday Evening Post" on Memorial Day, May 29, 1943. Rockwell's illustration features a brawny woman taking her lunch break with a rivet gun on her lap, beneath her a copy of Hitler's manifesto, "Mein Kampf" and a lunch pail labled "Rosie". Rockwell based the pose to match Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling painting of the prophet Isaiah.

Rockwell's model was a Vermont resident, then 19-year-old Mary Doyle Keefe who was a telephone operator near where Rockwell lived, not a riveter. Rockwell painted his "Rosie" as a larger woman than his model, and he later phoned to apologize. The Post's cover image proved hugely popular, and the magazine loaned it to the U.S. Treasury Department for the duration of the war, for use in war bond drives."

-- NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM

Source: https://sararedeghieri.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/rosietheriveter_rosie1.jpg.

#Rosie the Riveter Norman Rockwell#War Effort#United States#USA#Norman Rockwell Art#American history#Saturday Evening Post#Saturday Evening Post 1943#Paintings#Norman Rockwell Artist#Bull dyke#U.S. history#War history#Americana#Mary Doyle Keefe#Bull dike#WW2#Rosie the Riveter 1943#WW2 history#🇺🇸#American War Effort#Norman Rockwell Museum#U.S. War Effort#Painting#World War 2#American Style#WWII#World War II

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

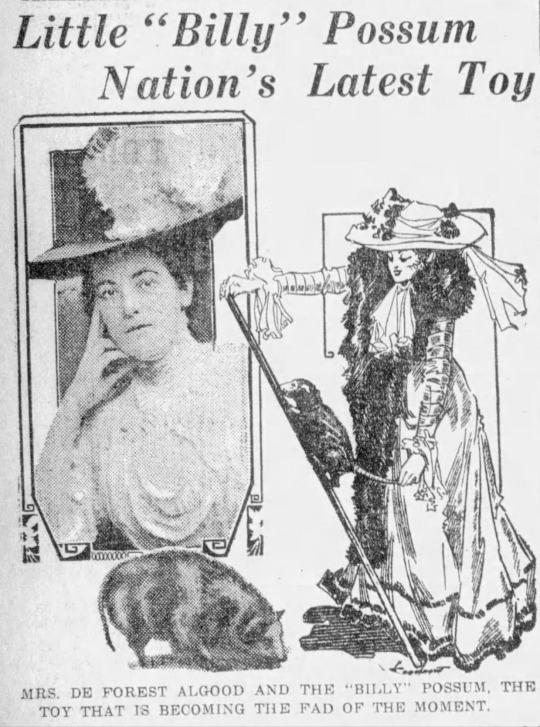

How A Stuffed Animal Named Billy Possum Tried—And Failed—To Replace The Teddy Bear As America’s National Toy

In 1909, wealthy widow Susie W. Allgood marketed a plush marsupial inspired by President William Howard Taft. But children thought the toy looked “too much like a rat,” and it sold poorly

— Howard Dorre | March 3, 2025

The New Jersey Morning Call said Billy Possum had “a head that is likely to give a baby [a] nightmare.” Illustration By Meilan Solly. Images via Newspapers.com and Espacenet

“If ‘Teddy Bear,’ why not ‘Billy Possum’?”

That was the question posed by a political cartoon in the January 10, 1909, issue of the Atlanta Constitution.

Inspired by a highly anticipated “possums and taters” banquet that the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce was hosting for incoming President William Howard Taft, the cartoon told the teddy bear to “beat it!” and declared Billy Possum “the new national toy.”

It might seem ridiculous to suggest that the beloved teddy bear, named for the story of Theodore Roosevelt’s refusal to shoot a restrained bear, could be replaced by a plush version of the 18-pound opossum served to Taft for dinner on January 15.

A 1909 Political Cartoon About Billy Possum Versus the Teddy Bear Atlanta Constitution via Newspapers.Com

But where most people saw a joke, wealthy Georgia widow Susie Wright Allgood saw a serious business opportunity. She would take Billy Possum from Georgia all the way to Broadway and the New York Supreme Court, and within six months, she would find the answers to the question “Why not ‘Billy Possum’?”

Allgood and her son Andrew P. Allgood, a Wall Street broker, quickly formed the Georgia Billy Possum Company with an office in the Flatiron Building in New York City. Within a week, Allgood met with patent lawyers, designers and manufacturers to get opossum toys into production in time for Taft’s March 4 inauguration. She planned for each Georgia delegate to wear a little Billy Possum in the parade.

Then Allgood went to work charming the press, quickly becoming the “storm center” of the possum fad, in the words of the Tennessee Journal and Tribune. She demurely referred to herself as “just a plain Georgia cracker,” but outlets like the Journal and Tribune disagreed, calling the 49-year-old “a remarkable woman in more respects than one, the gods having looked upon her with especial favor and partiality … with their gifts of wealth and beauty.” In 1896, the Constitution had reported that she was “notably one of the most beautiful women in the South.”

Susie Wright Allgood Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Press coverage of Billy Possum didn’t delve into Allgood’s tragic past, but it would have been familiar to Atlanta readers. An 1898 article in the Constitution noted that Allgood’s personal experiences with loss had uniquely prepared her for her volunteer work during the Spanish-American War, when she attended to wounded soldiers and consoled mothers who’d lost their sons. In 1890, Allgood’s husband, cotton mill owner DeForest Allgood, was murdered by his sister’s husband, leaving his wife to care for their two young children. One of those sons, 5-year-old DeForest Jr., died of croup three years later.

Allgood fully dedicated herself to the success of Billy Possum. She faced a “weird duality,” says Angel Kwolek-Folland, a historian at the University of Florida. “The possum thing is an interesting mix, because it’s a soft toy, which is for kids, except it’s also for politics. You have this national resonance with the political scene.” In 1909, Allgood couldn’t vote—she couldn’t even attend the possum dinner that inspired her business. But here she was, launching a toy as ambitious as she was, a toy the Constitution predicted to be “the petted darling of young America, the fad of the modish woman and the mascot of the incoming administration.”

A "Possum and Taters" Dinner Served to Incoming President William Howard Taft in January 1909 Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons

Both Allgood and her son Andrew came up with some innovative ideas to market Billy Possum. Most of the publicity was handled with live opossums under the bold assumption that seeing the creature in person would help. Billy Possum’s first stop was Broadway.

In an early form of influencer marketing, Allgood arranged for a live opossum to appear onstage with Anna Held, Broadway’s most popular musical comedy star. The actress was a pioneer of publicity stunts and product endorsement. Fans could buy Held-branded corsets, face powders and cigars. She had previously appeared onstage with life-size teddy bears, so she was the perfect choice to reveal the stuffed animal’s successor. Held walked out with the opossum during the last verse of her number “I’ve Lost My Little Brown Bear”—a surprise said to bring down the house.

Anna Held Performing with Teddy Bears in 1906 or 1907 Folger Shakespeare Library

Meanwhile, Andrew was working behind the scenes to popularize the possum in his own way. According to the press, he put together a “real possum party” at the King Edward Hotel in New York for the chorus girls of The Queen of the Moulin Rouge, a risqué show with song titles like “The Pleasure Brigade” and “Take That Off, Too.”

The evening kicked off with a “christening party” where two live opossums were dipped into a punchbowl of champagne. This was followed by a supper of pickled possum, possum soup, roast possum and possum pudding, and capped off by a “kissing party” where each girl “paid her respects” to the surviving opossums, a wire service reported.

Billy Possum Toy! This Rare Billy Possum Toy Sold at Auction in 2005 for £1,560. Courtesy of Christie's

The publicity stunt inspired headlines like “‘Possum Meat Am Good to Eat,’ Say Girlies Sweet,” but the stories failed to mention the Allgoods’ company or its stuffed toy.

Another aspect of Allgood’s marketing plan was the publication of a Billy Possum book, touted in the press as the next “national child’s book.” In the spirit of Joel Chandler Harris’ popular Uncle Remus stories, in which the formerly enslaved title character recounts African American folktales of animal characters such as Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox, Allgood planned to make a photobook that would lean into Southern stereotypes about eating possums that were rooted in white supremacy.

Allgood recruited a friend, poet Leonora Monteiro Martin, to write the book’s text and accompany her in taking original photographs. As Martin told the Knoxville Sentinel, “I met every possum in Georgia, and Mrs. Allgood and myself had some unique experiences touring the country in the neighborhood of Atlanta looking for typical Negro types and for possums.” The book was never published, but Allgood copyrighted several photos, some of which were published in a spread in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

By the end of January 1909, the Georgia Billy Possum Company was producing thousands of opossums advertised in three somewhat confusing sizes: life-size, medium and four inches long. Allgood had innovative plans for a new version that took advantage of the marsupial’s unique anatomy, patenting a “toy in the form of an opossum carrying its young” that would feature a pouch full of baby opossums.

Almost as soon as production began, it stalled when Billy Possum landed in the Supreme Court of New York. The Allgoods accused one of their manufacturers, Harry Nadler, of violating their exclusive contract and making Billy Possums for other companies. In late February, the judge issued a temporary injunction barring Nadler from making possums for anyone except the Georgia Billy Possum Company.

Allgood's Patent For a Billy Possum toy Espacenet

Just over a month later, on April 1—a night some children would never forget—a fire broke out at Nadler’s warehouse in New York’s Greenwich Village neighborhood.

Firefighters climbed to the top floor of the building to battle the blaze but found their path blocked by boxes of stuffed toys. They cleared the way by dumping hundreds of stuffed animals out the sixth-floor windows. According to newspaper reports, neighborhood children flocked to the scene to see the flaming teddy bears rain down upon Wooster Street. They eagerly scooped up the scorched, smoky bears. Opossum toys went unmentioned in the reports.

Nadler’s company filed for bankruptcy, and its remaining inventory of Billy Possums, teddy bears and other toys was sold at auction.

By May 1909, the future of Billy Possum looked bleak. Production problems aside, Billy Possum just wasn’t selling. There was little demand and stiff competition, especially when the German toy company Steiff debuted its own Billy Possum, albeit reluctantly.

“I don’t believe in mixing toys and politics,” Richard Steiff, the nephew of the company’s founder, told the American Stationer in 1912. He had designed a stuffed toy bear in 1902, before the teddy bear became associated with Roosevelt. “But they kept at me to make the ‘Billy Possum’ and then nobody wanted it.” The company sold 10,028 units in its first year but only a few hundred over the next several years.

Original Steiff opossums are in high demand today. “I’ve handled a couple in terrible condition, and they still bring in five grand,” says Rebekah Kaufman, a historian of the Steiff company. “That’s how rare they are.”

Steiff believed aesthetics were to blame for the toy’s failure. “The American youngster instinctively turns away from what is ugly or grotesque,” he told the American Stationer. “That was the trouble with the Billy Possum—it was too ugly an animal.” As Kaufman explains, Billy Possum was “so out of [the company’s] purview of the aesthetic of what they were making.”

That seemed to be the consensus. Allgood’s beauty may have been legendary, but the toy she championed was considered repulsive. The New Jersey Morning Call said the stuffed opossum had “a head that is likely to give a baby [a] nightmare.”

It looks “too much like a rat, is the complaint we get,” one toy importer told the Spokane Press. “They don’t go worth a cent. The kids won’t stand for ’em. … And we spent thousands of dollars on the chance that they would be a hit.”

In July 1909, just six months after Allgood launched her company, the Spokane Press declared, “Billy Possum a Failure but Teddy Bear Still a Joy With Little Ones.” That same week, Allgood, who had just sold 12 lots of her late husband’s Atlanta property for $82,267.70 (nearly $3 million today), left for Europe.

The White House Historical Association. June 15, 2016. In May 1929, an opossum found its way onto the White House grounds and was adopted by President and Mrs. Hoover. It resided outdoors in White House accommodations originally used by Rebecca, the pet raccoon of President and Mrs. Coolidge. Coincidently, the Hyattsville, Maryland High School Athletic Association had recently lost “Billy,” their opossum mascot. Many Hyattsville students believed the opossum at the White House was indeed their symbol. After a visit to the White House, they were disappointed to discover the White House opossum would not come to them when called, and thus was probably not their beloved mascot. Nevertheless, President Hoover let the team borrow his newly adopted opossum for good luck. After a successful athletic season, the student athletes gratefully returned the opossum to the White House. In the photo below, two young men, possibly students from Hyattsville, pose with the good luck opossum outside the White House. (FaceBook)

Billy Possum lived on during Taft’s presidency in songs and postcards—ephemera that did not depend on a child’s affection—and even made a brief return to politics. In 1929, President Herbert Hoover adopted a wild opossum found wandering the White House grounds and named it Billy Opossum.

When Allgood returned to the United States in the fall of 1910, she found herself in the papers once again, this time as a “woman smuggler.” The U.S. Customs Service accused her of grossly undervaluing her imported Parisian gowns, and her trunks were held for more than five months until the duties issue was resolved.

When she finally got her attire back, Allgood threatened to sue the government for damages, saying it had kept her clothes for so long that they were no longer in fashion.

She knew, better than most, that no amount of effort, money or marketing could force something to be in style.

A 1909 Newspaper Article About Allgood and Billy Possum Kentucky Post Via Newspapers.Com

#American 🇺🇸 History#American 🇺🇸 Presidents#Animala 🦔🦓🦒🐘🐆🐪🐫 🫏 🐕 🐈⬛ 🐈#Collecting#Entertainment#Fashion#Marsupials#Theodore Roosevelt#Toys#William Howard Taft#Women’s History#Smithsonian Magazine#Howard Dorre

0 notes

Text

Happy Black History Month! 2025

🍾 🪅 🥳 🎊 🍾

#n.e.w.s. brand#n.e.w.s.#n.e.w.s#news brand 88#n.e.w.s.brand#steer your destiny#los angeles#california#black excellence#black people#fba#foundational#foundational black american#2025#winter#black history month#February#88#america#USA#United States#United States of America#🇺🇸

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The legend of Harley’s lives on!. 🏍️

#harley davidson#road warriors#🚴 🏍️#american 🇺🇸#for america#american legend#american heritage#american history#classic motorcycle#motorcycle

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

an excerpt from the essay I wrote about country music because I'm an autistic little nerd boy

#country music#country#american civil war#american history#murica 🇺🇸🇺🇸#i know too much about this#hehe

1 note

·

View note

Text

What Black History Has To Do With The Cretaceous Period

Known Today As The “Black Belt,” The Southeastern United States Was Once Covered by an Ancient Sea—One That Continues To Shape Modern History.

— By James Edward Mills | February 26, 2025

A man with warm brown skin and a short tapped hair gazes upward and head tilted with one hand placed on top of the other. He is wearing a uniform with an emblem that is not fully visible. Photograph By Kris Graves

Frank Toland is a park ranger for Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site at Moton Field in Alabama. It is here where the Tuskegee Airmen started training for aerial combat in 1941 during World War II. Nearby is a site historians say is "where the South as we know it today begins." Photograph By Kris Graves

As a public historian and National Geographic Explorer, I’m constantly on the trail of interesting stories that connect a series of events dating back several centuries but continue to resonate into modern times. On a recent road trip through the American South, my partner, National Geographic photographer Kris Graves, and I drove through Tuskegee, Alabama, where we found a connection to a time long before human beings walked the Earth.

It’s a story of how the geology of the Cretaceous Period, between 70 and 100 Million years ago, emphatically changed the course of American history.

Where The South As We Know It Began

About 80 miles from Tuskegee, along highway 431, we approached Horseshoe Bend National Military Park. Not to be confused the "Horseshoe Bend" segment of the Colorado River in Arizona, this site, established in 1959, is the site of the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. My first assumption was that this was a battlefield from the Civil War. But as it turns out, I was off by more than 50 years.

A Map that Shows Fortifications and Troop Positions During War with Native Americans in 1814. Map Via Library Of Congress, Geography And Map Division

It was here in 1814, during the War of 1812, that General Andrew Jackson came to national prominence by defeating the Muscogee Indians. The Native People who had settled on the land surrounding the Tallapoosa River watershed, offered the last resistance against the expansion of the newly founded United States of America into this southeastern corner of the continent.

After the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the Treaty of Fort Jackson ceded more than 23 million acres of Native land to the U.S. Government and opened the Mississippi Territory for pioneer settlement. This area ultimately created the states we now call Alabama and Georgia. It has been suggested by historians that this is where the South as we know it today begins.

This was a geographic flash point of American history. After the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the Muscogee Indians were summarily displaced and sent to reservations in Oklahoma and other points on the map west of the Mississippi River. From 1816 to 1840 native people were forced to travel west along a path known commonly as the Trail of Tears.

Once removed, Native People were replaced with white settlers who quickly discovered the rich soil in this location was perfect for the cultivation of cash crops such as indigo, corn, rice and cotton. In letters to his wife, Rachel, Andrew Jackson writes about the soil of Alabama: "The lands through which we passed are some of the richest this country can boast—well watered and abundantly fertile, they will no doubt soon be settled by a happy and prosperous people."

Left: A vintage, open-cockpit biplane called the PT-13D Stearman Kaydet was used to train the first generation of Black American combat pilots at the Tuskegee Institute. Photograph By Kris Graves. Right: A group of soldiers lined up with a plane in the background Tuskegee airmen training in 1942. Photograph By Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office Of War Information Black-And-White Negatives

Ancient Organism Laid The Foundation For The South’s Fertile Land

There’s a deep reason for the richness of the soil they remarked on there.

Over 70 million years ago, during the late Cretaceous period, the southeastern U.S. was a warm, subtropical region covered by a vast shallow sea known as the Western Interior Seaway. Much of the area was a coastal plain with swamps, rivers, and dense vegetation. Dinosaurs like hadrosaurs, tyrannosaurs, and ceratopsians roamed the land, while giant marine reptiles such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs dominated the waters. The climate was humid, and the region was rich in diverse plant and animal life, resembling modern coastal wetlands and estuaries.

Over millions of years, marine organisms like plankton and shellfish accumulated on the seafloor, forming thick deposits of calcium-rich limestone. When the sea receded, these limestone deposits weathered into fertile, alkaline soils that became ideal for agriculture. This rich, dark soil gave the Black Belt—an area that stretches from east-central Mississippi through central Alabama and into western Georgia--its name and later made the region a prime area for cotton farming in the 19th century.

The National Memorial For Peace and Justice in Montgomery Alabama is dedicated to Black Americans who were terrorized by lynching throughout the late 19th and 20th Centuries. A series of pillars hang in the display to represent the many counties across the U.S. where incidents of public execution were perpetrated. The name of each victim is inscribed on the pillar of the county in which they were killed. Photograph By Kris Graves

The Ancient History Still Leaves An Imprint On The Present

The geological landscape of the Black Belt created the physical environment where Black Americans would be subjected to the cruel exploitation of their labor. First through chattel slavery, then by a system of inequitable sharecropping and convict leasing programs, people of African descent would be made to work the soil of this region so rich in fossil decay.

But labor-intensive commodities like cotton require a great many hands to reap their benefits. The necessity for a dedicated workforce provided the economic incentive to expand and intensify the institution of slavery. In this place, at this time, through the Civil War, we see an ever-increasing concentration of enslaved Black Americans. And, their descendants still live there today.

In the 21st Century, the descendants of the formerly enslaved make up large segments of the population in these areas. The Black Belt's geological, historical and demographic legacy, combined with ongoing advocacy efforts, has made it a critical region for Black voter registration and political empowerment throughout the United States.

Coretta Scott King, John Lewis and a crowd of 5,000, march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge from Selma, Alabama Saturday, March 8, 1975. The historic march takes place on land that was made fertile by an ancient sea. Photograph By Associated Press

The geographic footprint of the Black Belt directly overlays the route of the U.S. Civil Rights Trail. Defined by a series of historic parks and monuments managed by the National Park Service, this path traces a timeline through critical moments in Black American history. From the murder of Emmitt Till near Greenwood, Mississippi, to where Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, to the site of the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing in Birmingham, to where John Lewis led the march for voting rights in Selma across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, to the training base of the Tuskegee Airmen, each of these locations and corresponding events can be traced back in history to the formation of soil made fertile almost 100 million years ago.

Despite the passage of time, even ions of geological transformation, history never gets old. There is always something new to learn from the past.

— James Edward Mills is a Freelance Journalist and National Geographic Explorer who Specializes in Stories about the History our National Parks and Environmental Conservation on Public Land.

#History & Culture#Indigenous Peoples#African Americans#Native Americans#Black History#Cretaceous Period#“Black Belt”#Southeastern United States 🇺🇸#Ancient Sea#Modern History#Ancient Organism#South’s Fertile Land#James Edward Mills

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

President Trump Hosts a Reception Honoring Black History Month

#n.e.w.s. brand#n.e.w.s.#n.e.w.s#news brand 88#n.e.w.s.brand#steer your destiny#usa#us#united states#united states of America#donald trump#donald j trump#black people#black history month#speech#winter#winter solstice#winter '25#foundational black american#fba#black america#america#🇺🇸#President#presidential#88#2025

2 notes

·

View notes