#Agro Economics

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nano Fertilizer Market Strategies, Environmental Impact, and Sustainable Agricultural Practices

The global nano fertilizer market size is expected to reach USD 9,377.3 million by 2030, as per the new report by Grand View Research, Inc. The market is expected to grow at a robust CAGR of 14.8% from 2022 to 2030. The industry growth is primarily driven by increasing demand for better crop yields due to a significant rise in the global population and limited availability of key resources like land.

Nano Fertilizer Market Report Highlights

The global market is estimated to advance at a CAGR of 14.8% from 2022 to 2030. This is attributed to the rising demand for food crops due to the increasing population thus creating the need for using high-yield nano fertilizers

North America dominated the global market in 2021 with a revenue share of over 34%. This is owed to advancement in agriculture in developed countries such as Canada and the U.S.

Favorable policies along with technological advancements in the agricultural sector helped make the U.S., the largest consumer of nano fertilizer

Nitrogen emerged as a major raw material used for the production of nano fertilizer in 2021, with a revenue share of over 25%. Easy and cheap availability of Nitrogen makes it the topmost preference among consumers

Soil method of application captured the largest market share of over 70% in 2021. This growth is attributed to the capability of nano fertilizers to release nutrients in the soil, thus, enabling better penetration into the roots of the crops

Cereals & grains are the largest application segment in terms of revenue. It contributed over 40% to the global revenue share. The growth of this segment can be attributed to the fact that it is the major source of iron, dietary proteins, vitamins, and dietary fibers required by the human body. Thus, to fulfill the growing demand for cereals & grains continues to push food growers to purchase nano fertilizers in rising quantities

For More Details or Sample Copy please visit link @: Nano Fertilizer Market Report

Growing focus on increasing the quantity of yield has led to the indiscriminate use of fertilizers in agriculture. This can result in both environmental and agricultural catastrophes by degrading the quality of the soil. According to a report by Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), natural resources such as water and arable land are on the verge of exhaustion. Furthermore, degradation at a high rate continues due to intensive urbanization and excessive use of chemical fertilizers. Thus, the declining nutritional quality of food and degraded quality of soil continues to drive a gradual shift toward nanotechnology in agriculture. Nano fertilizers remains an ideal prospect to maintain the quality of soil while meeting production target.

The use of nano fertilizers can help in reducing chemical fertilizer consumption by 80 to 100 times, thus reducing the reliance on chemical fertilizers. For instance, the demand for nano urea is increasing worldwide as it has the ability to replace regular urea usage at a relatively lower cost while offering high yields to crops. By 2023 nano urea is expected to replace the usage of 13.7 million tons of conventional urea. Thus, the huge demand for nano fertilizer from the agriculture industry along with supportive government policies continues to promote newer and more efficient agriculture techniques.

The importance of policy framework remains paramount to promote sustainable growth, and such framework is already in place for nano fertilizers in key regions. For instance, U.S department of agriculture in 2020 announced to make USD 250 million investment through its new grant program. This initiative was taken to support new innovative and more efficient fertilizer production in the region. Additionally, USDA seeks growth in competition as it aims to allay concerns regarding supply chain. With its new initiatives, the USDA continues to introduce more transparency for consumers to make them aware of the safety of agriculture produce. These initiatives aimed at gauging the use of fertilizers, seeds, retail markets, continue to generate momentum for the eco-friendly and high-yield promising nano fertilizers.

#Nano Fertilizers#Crop Nutrition#Agritech#Fertilizer Technology#Smart Farming#Green Revolution#Agribusiness#Crop Yield Enhancement#Environmental Sustainability#Global Food Security#Nano-technology In Agriculture#Agro-chemicals#Farming Solutions#Future Of Farming#Nutrient Management#Crop Productivity#Nano-Agri Solutions#Agri Tech Trends#Agro Economics#Modern Agriculture#Agri Research#Tech In Farming#Agricultural Science#Eco-Friendly Fertilizers

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cultivating Change: The Impact of Climate-Smart Agriculture on Women’s Economic Empowerment in Kenya

Discover how Christine Krapiwan transformed her life from struggling farmer to thriving entrepreneur through the Women’s Economic Empowerment and Climate-Smart Agriculture (WEE CSA) project, empowering women in Kenya’s Arid and Semi-Arid Lands. Explore the profound impact of the WEE CSA project on women farmers in Kenya, highlighting stories of empowerment, climate-smart agriculture, and…

#Agricultural Innovation#agricultural training#agro-vet shops#capacity building#Christine Krapiwan#Climate resilience#Climate-Smart Agriculture#community transformation#economic sustainability#empowerment stories#Food security#inclusive farming practices#income generation#kenya#local government collaboration#Nutrition#poultry farming#rural entrepreneurship#self-help groups#smallholder farmers#societal impact#sustainable agriculture#Village Savings and Loan Association#WEE-CSA Project#West Pokot County#women empowerment#women in agriculture#Women&039;s Economic Empowerment#women&039;s health.#women&039;s leadership

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pope Francis defended Indigenous Peoples and the preservation of the Amazon

“The original Amazonian peoples have probably never been so threatened in their territories as they are now.” This statement was made by Pope Francis on 19 January 2018 during a meeting with Indigenous people from Brazil, Peru and Bolivia. The event was held in the city of Puerto Maldonado, Peru. The Pontiff, who died this Monday, the 21st, was the Catholic Church’s most active leader in defending Indigenous Peoples and the Amazon.

The meeting was attended by more than 30 Indigenous peoples, from whom the Pope heard reports of violations in their territories and highlighted the richness, knowledge and Indigenous diversity. On the occasion, he also stated that it was necessary to listen to the traditional population living in the Amazon. “Let it now be you yourselves who self-define and show us your identity. We need to listen to you,” he declared.

At the event, the Pontiff warned about the rise of extractivism in the region and the strong pressure from major economic interests, pointing to “greed for oil, gas, timber, gold, agro-industrial monocultures.” The leader of the Catholic Church also mentioned the “perversion of certain policies that promote conservation of nature without taking the human being into account,” which generates “situations of oppression for Indigenous peoples.”

Continue reading.

#brazil#politics#pope francis#religion#environmentalism#brazilian politics#peru#bolivia#peruvian politics#bolivian politics#amazon rainforest#indigenous rights#vatican#geopolitics#image description in alt#mod nise da silveira

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since propaganda against South Africa will be ramping up here's a short reading list about South African history:

The Colonial Period

The Anatomy of a South African Genocide: The Extermination of the Cape San Peoples - The genocide of the indigenous hunter-gatherer people's in South Africa is somewhat overshadowed by apartheid but it's a core part of South Africa's history and a core part of white supremacist rhetoric, who argue the land was empty before they came. They forcibly emptied the land by killing everyone who refused to integrate into the burgeoning agro-pastoral capitalist society. There are some bits of the book I disagree with, such as framing other indigenous groups treatment of foragers being equivalent or worse than the settlers (source: the settlers) and using terms like outdated terms "Khoisan" but it's a good introduction to the topic if you keep that in mind.

Slavery in South Africa: Captive Labor on the Dutch Frontier - From what I have currently read this is the most detailed analysis on slavery in South Africa up to date. It is during the colonial period that much of the apartheid laws find their predecessors and the existence of a large base of slave-holding whites (as well as whites too poor to own slaves but still wanted free labour) really provides a background to why apartheid manifested itself in the way that it did as opposed to other settler-colonies.

Apartheid:

I Write What I Like - A collection of essays by anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko who was killed by the apartheid regime in 1979 at the age of 30. He was a leader of the Black Consciousness Movement during the 60s and 70s which was highly critical of anti-apartheid white liberals (as well as white leftists) which is reflected in these essays.

A Crime Against Humanity: Analysing the Repression of the Apartheid State - This book very neatly describes each and every crime of the apartheid regime in a digestible way. Until I read this it didn't really occur to me that the Apartheid government was responsible for around 2.5 million deaths across Southern Africa minimum through their proxy contra groups and militias and that's only one point made here.

Long Walk To Freedom - It's Nelson Mandela's bibliography. What more can be said?

General:

The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa - Even though the primary chapters of interest are the ones regarding South Africa specifically, the entirety of the book is useful in seeing the different ways that colonisers constructed their own identities and created new identities for indigenous people (often with the help of the colonised elite).

Making Race: Politics and Economics of Coloured Identity in South Africa - Essentially a longer version of one of the chapters in the previous book. Although the book is ostensibly about Coloured identity (and it is about that don't get me wrong), it also shows some of the divisions in the various factions in the National Party in their approaches to white nationalism and the demographic question.

Regarding Muslims: From Slavery to Post-apartheid - A comprehensive look at how Muslims have been portrayed in South Africa both by others and within the community itself.

Coloured: How Classification Became Culture and Coloured by history, shaped by place: New perspectives on coloured identities in Cape Town - Both of these books (along with Making Race) are excellent for understanding Coloured identity and it's relationship to colonialism and apartheid, and how the idenitity emerged in the first place (which is much more complex than Coloureds being just "mixed race". Both are also written in an accessible form (although the former is written for a much more general audience).

Other:

Zimbabwe Takes Back It's Land & Land and Agrarian Reform in Zimbabwe - Although these books aren't directly related to South Africa, they are related to the land reform in Zimbabwe, a country which was not only demonised on the international stage for daring to redistribute land from wealthy landowners to the indigenous people of the nation but has been continually punished for doing so for over 2 decades through sanctions.

Many white South Africans and other white supremacists will bring up Zimbabwe in their propaganda to show the "negative consequences" of land reform, ignoring the sanctions and international isolation that was brought about by the West following these reforms. These two books debunk the mainstream narrative in detail and describe how land reform has changed Zimbabwe entirely (ZTBIL is a lot more accessible for a general audience).

Feel free to make other recommendations in the notes.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day of the Mushroom

The Day of the Mushroom celebration is celebrated on April 16 and honors all things fungi. The fleshy, spore-bearing fruiting body of a fungus, which can grow anywhere above ground, on soil, or its food source, is known as a mushroom. The white button mushroom, which is grown, is the standard fungus to be called a mushroom. Therefore, fungi with a stem, cap, and gills on the underside of their cap are those to which the term “mushroom” is most frequently applied. The name “mushroom” is also relevant to describing the fleshy fruiting bodies of other Ascomycota because it is used to describe a range of different gilled fungi that may or may not have a stem.

History of Day of the Mushroom

Since they first appeared in early European communities, it is generally assumed that people have been gathering mushrooms since the beginning of time, possibly even in prehistoric times. Truffles and other types of mushrooms were prized in classical Greece and Rome. American author Cynthia Bertelsen claims in her book “Mushroom: A Global History” that both well-known historical authors, Pliny the Elder and Aristotle, wrote about fungus. She also claims that the Roman philosopher Galen wrote several paragraphs on the collection of wild mushrooms. Cynthia Bertelsen goes on to add that it is likely that China and Japan were the first places to cultivate mushrooms as early as 600 A.D.

But it took time for Americans to accept and become accustomed to mushrooms. In the cookbook “The Virginia Housewife,” mushrooms are mentioned for the first time in America (1824). Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom Soup, a classic American staple for casserole recipes, was created in the 1930s. Bertelsen adds that there may be archaeological proof of the spiritual usage of mushrooms as early as 10000 B.C. There is proof that various cultures, including the Ancient Greeks, the Mayans, the Chinese, and the Vikings, among many others, used hallucinogenic mushrooms.

Humans now consume edible mushrooms regularly, which has greatly boosted the agricultural and agro-economic development of the areas where they are grown. Around half of all farmed edible mushrooms are produced in China, which also accounts for six pounds of yearly mushroom consumption per person among the world’s 1.4 billion inhabitants. With an estimated 194,000 tonnes of yearly edible mushroom exports, Poland was the leading exporter of mushrooms in 2014.

Day of the Mushroom timeline

600 A.D.

Earliest Known Cultivation of Mushrooms

Mushrooms are said to have been cultivated as far back in time as 600 A.D. in Japan and China.

1824

The Cookbook “The Virginia Housewife” is Published

The popular American cookbook “The Virginia Housewife” is released.

1966

Cynthia Berthelsen is Born

Berthelsen is born on June 1 and becomes an American author, food expert, and photographer.

2013

“Mushroom: A Global History” is Published

Berthelsen’s book “Mushroom: A Global History” is published.

Day of the Mushroom FAQs

What is Day of the Mushroom?

Day of the Mushroom, celebrated on April 16, is an American holiday created to celebrate the mushroom and its health and ecological benefits.

What are mushrooms?

Mushrooms are the fleshy, spore-bearing fruiting bodies of fungi, which are typically produced anywhere above ground, on soil, or the source of their food.

Are mushrooms edible?

Yes. Some mushrooms taste good and are safe for human consumption.

Day of the Mushroom Activities

Go mushroom hunting: It's a good idea to go mushroom hunting on the Day of the Mushroom. Depending on a variety of variables, you can sometimes find mushrooms in your yard or the woods.

Eat some mushrooms: Consume some mushrooms! When used as culinary garnishing, several edible mushrooms are quite a delicacy and are also nutritious.

Share the fun online: Don't forget to use the hashtag #DayOfTheMushroom to share your mushroom-related fun. Participate in the online discussion.

5 Interesting Facts About Mushrooms

They breathe like humans do: Similar to how humans breathe, mushrooms take in oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide.

Fruiting bodies of mycelium: The fruiting body of the mycelium, not the mushroom, is the primary part.

Mushrooms can be edible: Some mushrooms taste good and are safe for human consumption.

China produces the most mushrooms: In terms of producing edible mushrooms, China leads the world, followed by Japan and then the United States.

Mushroom spores can survive in space: Mushroom spores can survive the radiation and vacuum in space.

Why We Love Day of the Mushroom

Some mushrooms are edible: Some, if not most, mushrooms are edible. That’s just one more source of food for us humans!

Edible mushrooms are tasty: Edible mushrooms are actually tasty as well, and they definitely make a good vegan snack. Go pick some today!

Mushrooms can be healthy: Mushrooms are fungi, and as such, their consumption is healthy. We love this!

Source

#steak with mushrooms#Bacon Wrapped Mushrooms#tapas#Spain#USA#Switzerland#Chicago Special Stuffed Pizza#Roasted Mushrooms#travel#Brix Restaurant & Gardens#Sweden#Verduras del labrador#food#restaurant#Day of the Mushroom#street food#original photography#tourist attraction#landmark#Canada#16 April#DayOfTheMushroom#Mushroom Soup#Champños Serranos#Kimchi Mandu Jeongol Hot Pot#Truffled Parmesan Chicken#Bacon Mushroom Mikeburger#Hot Mushroom Sandwich#vacation

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

While Marx often shows enthusiasm for the potentiality of enhanced forms of human cooperation enabled by globalizing production, already in the nineteenth century, he observed an antagonistic separation of town and country and suggested that production chains were overstretched and wasting resources. Today, lessening the spatial disjuncture between production and consumption must be an explicit feature and aim of sustainable and just transition and, in this context, calls on the left for partial deglobalization, including the shortening of commodity chains, have merit and are quite consistent with Marx’s analysis. In a process of partial deglobalization, production for local and domestic needs—rather than production for export—would again become the center of gravity of the economy. A move away from the export orientation of domestic corporations and a process of renationalization could also allow enterprises to begin to develop their own strategies, moving away from the whims of the global market and choices taken by corporate controllers. Such transformation could enable spaces for independent development in the Global South. To do so, they could focus on shifting agrarian systems, orienting their production away from agro-export (which is a source of tremendous ecological irrationality and unequal exchange) toward food sovereignty. Such shifts would need to be accompanied by simultaneous, coordinated shifts toward enhanced local and domestic food production in Global North, alongside a move from high-input agriculture to agroecology, and, in settler colonial contexts, enhanced Indigenous sovereignty. Within domestic spaces or regions, efforts must simultaneously be made to mend a rift between the city and the country. For a model of the environmentalist city, one could look to Havana for inspiration. During Cuba’s Special Period in the 1990s, organic, low-input agriculture was developed both in the countryside, as well as in the island’s capital through urban farms. Urban agriculture is here not niche or small-scale—it covers large expanses within and at the outskirts of the city, where rich land is located. In the transition to renewables, energy production should also be localized as much as possible. This is a potentiality inherent in renewable energy “flow,” in contrast to concentrated energy “stock,” or fossil fuels. While lessening the spatial disjuncture between production and consumption is part of developing ecologically rational production, this aim should be recognized to be in some tension with economic planning (at least in the longer term), insofar as expansive planning is potentiated by the socialization of production. Thus, calls for localization of production imply a diminishment in productive association across firms and regions and the potential to plan such interconnections. Practically, it is important to recognize that such a process confronts material interdependencies, as existing productive networks and infrastructural configurations support and sustain huge swaths of human life. Different regions and cities also have different specializations and different ecological capacities. In an existing world of evolved economic interdependencies, the reproductive needs of various communities require continued global resource flows. Climate change also creates severe survival and livelihood challenges on a highly uneven basis, and global trade and divisions of labor can act as safeguards against issues such as pandemics related to water-supply failures and reduced agricultural yields. More broadly, we should carefully consider Marx’s suggestion that well-organized territorial divisions of labor are collective powers and can be a part of collaboration in human affairs. This extends to territorial specialization, which, consciously organized, could involve a collaborative partitioning of resources and capacities.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

A.3.2 Are there different types of social anarchism?

Yes. Social anarchism has four major trends — mutualism, collectivism, communism and syndicalism. The differences are not great and simply involve differences in strategy. The one major difference that does exist is between mutualism and the other kinds of social anarchism. Mutualism is based around a form of market socialism — workers’ co-operatives exchanging the product of their labour via a system of community banks. This mutual bank network would be “formed by the whole community, not for the especial advantage of any individual or class, but for the benefit of all … [with] no interest … exacted on loans, except enough to cover risks and expenses.” Such a system would end capitalist exploitation and oppression for by “introducing mutualism into exchange and credit we introduce it everywhere, and labour will assume a new aspect and become truly democratic.” [Charles A. Dana, Proudhon and his “Bank of the People”, pp. 44–45 and p. 45]

The social anarchist version of mutualism differs from the individualist form by having the mutual banks owned by the local community (or commune) instead of being independent co-operatives. This would ensure that they provided investment funds to co-operatives rather than to capitalistic enterprises. Another difference is that some social anarchist mutualists support the creation of what Proudhon termed an “agro-industrial federation” to complement the federation of libertarian communities (called communes by Proudhon). This is a “confederation … intended to provide reciprocal security in commerce and industry” and large scale developments such as roads, railways and so on. The purpose of “specific federal arrangements is to protect the citizens of the federated states [sic!] from capitalist and financial feudalism, both within them and from the outside.” This is because “political right requires to be buttressed by economic right.” Thus the agro-industrial federation would be required to ensure the anarchist nature of society from the destabilising effects of market exchanges (which can generate increasing inequalities in wealth and so power). Such a system would be a practical example of solidarity, as “industries are sisters; they are parts of the same body; one cannot suffer without the others sharing in its suffering. They should therefore federate, not to be absorbed and confused together, but in order to guarantee mutually the conditions of common prosperity … Making such an agreement will not detract from their liberty; it will simply give their liberty more security and force.” [The Principle of Federation, p. 70, p. 67 and p. 72]

The other forms of social anarchism do not share the mutualists support for markets, even non-capitalist ones. Instead they think that freedom is best served by communalising production and sharing information and products freely between co-operatives. In other words, the other forms of social anarchism are based upon common (or social) ownership by federations of producers’ associations and communes rather than mutualism’s system of individual co-operatives. In Bakunin’s words, the “future social organisation must be made solely from the bottom upwards, by the free association or federation of workers, firstly in their unions, then in the communes, regions, nations and finally in a great federation, international and universal” and “the land, the instruments of work and all other capital may become the collective property of the whole of society and be utilised only by the workers, in other words by the agricultural and industrial associations.” [Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, p. 206 and p. 174] Only by extending the principle of co-operation beyond individual workplaces can individual liberty be maximised and protected (see section I.1.3 for why most anarchists are opposed to markets). In this they share some ground with Proudhon, as can be seen. The industrial confederations would “guarantee the mutual use of the tools of production which are the property of each of these groups and which will by a reciprocal contract become the collective property of the whole … federation. In this way, the federation of groups will be able to … regulate the rate of production to meet the fluctuating needs of society.” [James Guillaume, Bakunin on Anarchism, p. 376]

These anarchists share the mutualists support for workers’ self-management of production within co-operatives but see confederations of these associations as being the focal point for expressing mutual aid, not a market. Workplace autonomy and self-management would be the basis of any federation, for “the workers in the various factories have not the slightest intention of handing over their hard-won control of the tools of production to a superior power calling itself the ‘corporation.’” [Guillaume, Op. Cit., p. 364] In addition to this industry-wide federation, there would also be cross-industry and community confederations to look after tasks which are not within the exclusive jurisdiction or capacity of any particular industrial federation or are of a social nature. Again, this has similarities to Proudhon’s mutualist ideas.

Social anarchists share a firm commitment to common ownership of the means of production (excluding those used purely by individuals) and reject the individualist idea that these can be “sold off” by those who use them. The reason, as noted earlier, is because if this could be done, capitalism and statism could regain a foothold in the free society. In addition, other social anarchists do not agree with the mutualist idea that capitalism can be reformed into libertarian socialism by introducing mutual banking. For them capitalism can only be replaced by a free society by social revolution.

The major difference between collectivists and communists is over the question of “money” after a revolution. Anarcho-communists consider the abolition of money to be essential, while anarcho-collectivists consider the end of private ownership of the means of production to be the key. As Kropotkin noted, collectivist anarchism “express[es] a state of things in which all necessaries for production are owned in common by the labour groups and the free communes, while the ways of retribution [i.e. distribution] of labour, communist or otherwise, would be settled by each group for itself.” [Anarchism, p. 295] Thus, while communism and collectivism both organise production in common via producers’ associations, they differ in how the goods produced will be distributed. Communism is based on free consumption of all while collectivism is more likely to be based on the distribution of goods according to the labour contributed. However, most anarcho-collectivists think that, over time, as productivity increases and the sense of community becomes stronger, money will disappear. Both agree that, in the end, society would be run along the lines suggested by the communist maxim: “From each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs.” They just disagree on how quickly this will come about (see section I.2.2).

For anarcho-communists, they think that “communism — at least partial — has more chances of being established than collectivism” after a revolution. [Op. Cit., p. 298] They think that moves towards communism are essential as collectivism “begins by abolishing private ownership of the means of production and immediately reverses itself by returning to the system of remuneration according to work performed which means the re-introduction of inequality.” [Alexander Berkman, What is Anarchism?, p. 230] The quicker the move to communism, the less chances of new inequalities developing. Needless to say, these positions are not that different and, in practice, the necessities of a social revolution and the level of political awareness of those introducing anarchism will determine which system will be applied in each area.

Syndicalism is the other major form of social anarchism. Anarcho-syndicalists, like other syndicalists, want to create an industrial union movement based on anarchist ideas. Therefore they advocate decentralised, federated unions that use direct action to get reforms under capitalism until they are strong enough to overthrow it. In many ways anarcho-syndicalism can be considered as a new version of collectivist-anarchism, which also stressed the importance of anarchists working within the labour movement and creating unions which prefigure the future free society.

Thus, even under capitalism, anarcho-syndicalists seek to create “free associations of free producers.” They think that these associations would serve as “a practical school of anarchism” and they take very seriously Bakunin’s remark that the workers’ organisations must create “not only the ideas but also the facts of the future itself” in the pre-revolutionary period.

Anarcho-syndicalists, like all social anarchists, “are convinced that a Socialist economic order cannot be created by the decrees and statutes of a government, but only by the solidaric collaboration of the workers with hand and brain in each special branch of production; that is, through the taking over of the management of all plants by the producers themselves under such form that the separate groups, plants, and branches of industry are independent members of the general economic organism and systematically carry on production and the distribution of the products in the interest of the community on the basis of free mutual agreements.” [Rudolf Rocker, Anarcho-syndicalism, p. 55]

Again, like all social anarchists, anarcho-syndicalists see the collective struggle and organisation implied in unions as the school for anarchism. As Eugene Varlin (an anarchist active in the First International who was murdered at the end of the Paris Commune) put it, unions have “the enormous advantage of making people accustomed to group life and thus preparing them for a more extended social organisation. They accustom people not only to get along with one another and to understand one another, but also to organise themselves, to discuss, and to reason from a collective perspective.” Moreover, as well as mitigating capitalist exploitation and oppression in the here and now, the unions also “form the natural elements of the social edifice of the future; it is they who can be easily transformed into producers associations; it is they who can make the social ingredients and the organisation of production work.” [quoted by Julian P. W. Archer, The First International in France, 1864–1872, p. 196]

The difference between syndicalists and other revolutionary social anarchists is slight and purely revolves around the question of anarcho-syndicalist unions. Collectivist anarchists agree that building libertarian unions is important and that work within the labour movement is essential in order to ensure “the development and organisation … of the social (and, by consequence, anti-political) power of the working masses.” [Bakunin, Michael Bakunin: Selected Writings, p. 197] Communist anarchists usually also acknowledge the importance of working in the labour movement but they generally think that syndicalistic organisations will be created by workers in struggle, and so consider encouraging the “spirit of revolt” as more important than creating syndicalist unions and hoping workers will join them (of course, anarcho-syndicalists support such autonomous struggle and organisation, so the differences are not great). Communist-anarchists also do not place as great an emphasis on the workplace, considering struggles within it to be equal in importance to other struggles against hierarchy and domination outside the workplace (most anarcho-syndicalists would agree with this, however, and often it is just a question of emphasis). A few communist-anarchists reject the labour movement as hopelessly reformist in nature and so refuse to work within it, but these are a small minority.

Both communist and collectivist anarchists recognise the need for anarchists to unite together in purely anarchist organisations. They think it is essential that anarchists work together as anarchists to clarify and spread their ideas to others. Syndicalists often deny the importance of anarchist groups and federations, arguing that revolutionary industrial and community unions are enough in themselves. Syndicalists think that the anarchist and union movements can be fused into one, but most other anarchists disagree. Non-syndicalists point out the reformist nature of unionism and urge that to keep syndicalist unions revolutionary, anarchists must work within them as part of an anarchist group or federation. Most non-syndicalists consider the fusion of anarchism and unionism a source of potential confusion that would result in the two movements failing to do their respective work correctly. For more details on anarcho-syndicalism see section J.3.8 (and section J.3.9 on why many anarchists reject aspects of it). It should be stressed that non-syndicalist anarchists do not reject the need for collective struggle and organisation by workers (see section H.2.8 on that particular Marxist myth).

In practice, few anarcho-syndicalists totally reject the need for an anarchist federation, while few anarchists are totally anti-syndicalist. For example, Bakunin inspired both anarcho-communist and anarcho-syndicalist ideas, and anarcho-communists like Kropotkin, Malatesta, Berkman and Goldman were all sympathetic to anarcho-syndicalist movements and ideas.

For further reading on the various types of social anarchism, we would recommend the following: mutualism is usually associated with the works of Proudhon, collectivism with Bakunin’s, communism with Kropotkin’s, Malatesta’s, Goldman’s and Berkman’s. Syndicalism is somewhat different, as it was far more the product of workers’ in struggle than the work of a “famous” name (although this does not stop academics calling George Sorel the father of syndicalism, even though he wrote about a syndicalist movement that already existed. The idea that working class people can develop their own ideas, by themselves, is usually lost on them). However, Rudolf Rocker is often considered a leading anarcho-syndicalist theorist and the works of Fernand Pelloutier and Emile Pouget are essential reading to understand anarcho-syndicalism. For an overview of the development of social anarchism and key works by its leading lights, Daniel Guerin’s excellent anthology No Gods No Masters cannot be bettered.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Business Opportunities for Agri & Food Processing Sector in Rajasthan: Col Rajyavardhan Rathore

Rajasthan, known for its rich cultural heritage and vast arid landscapes, is rapidly emerging as a hub for the agriculture and food processing sector. With its unique agricultural produce, favorable policies, and increasing investment in food processing infrastructure, the state offers a wealth of business opportunities for entrepreneurs and investors. Col Rajyavardhan Rathore, a prominent leader from Rajasthan, has consistently emphasized the importance of leveraging this sector to drive sustainable economic growth and uplift rural livelihoods.

Why Rajasthan is a Prime Destination for Agri & Food Processing Ventures

Rajasthan’s diverse agro-climatic zones and rich agricultural traditions make it a prime destination for ventures in agriculture and food processing. Key factors driving this growth include:

Abundant Agricultural Produce: Rajasthan is a leading producer of crops like millet, wheat, mustard, and pulses, as well as horticultural produce like guava, pomegranate, and ber (Indian jujube).

Strategic Location: Proximity to major markets like Delhi, Gujarat, and Maharashtra enhances logistics efficiency.

Government Support: Favorable policies and incentives to promote food processing industries.

Key Opportunities in Rajasthan’s Agri & Food Processing Sector

1. Cereal and Grain Processing

Rajasthan is the largest producer of bajra (pearl millet) and a significant producer of wheat and barley.

Opportunities include milling, packaging, and exporting these staples to domestic and international markets.

2. Oilseed Processing

The state is India’s top producer of mustard seeds, making it ideal for setting up mustard oil extraction and processing units.

Value-added products like mustard oil cakes for animal feed also present lucrative business opportunities.

3. Dairy Industry

With a strong livestock population, Rajasthan has immense potential in milk production and processing.

Opportunities include setting up dairy plants for products like butter, cheese, and flavored milk.

4. Horticulture-Based Businesses

Rajasthan is known for its high-quality pomegranates, kinnows, and dates.

Processing units for juices, jams, and dried fruits can tap into both domestic and export markets.

5. Spice Production and Processing

The state is a significant producer of spices like coriander, cumin, and fenugreek.

Setting up spice grinding and packaging units can cater to increasing demand from urban markets and exports.

6. Herbal and Medicinal Plants

Rajasthan’s arid climate supports the cultivation of medicinal plants like aloe vera, isabgol, and ashwagandha.

Opportunities include producing herbal extracts, essential oils, and ayurvedic medicines.

7. Organic Farming and Products

With growing awareness of health and sustainability, organic farming is gaining traction.

Export of organic grains, vegetables, and processed foods is a high-potential area.

8. Cold Storage and Logistics

Lack of adequate cold storage infrastructure poses a challenge, creating an opportunity for investment.

Businesses can also invest in modern logistics systems for efficient transportation of perishable goods.

Policy Support for Agri & Food Processing in Rajasthan

The Rajasthan government has introduced a host of initiatives to promote investment in the sector:

Rajasthan Agro-Processing, Agri-Business & Agri-Export Promotion Policy: Offering incentives like capital subsidies, tax rebates, and single-window clearances.

Mega Food Parks Scheme: Establishment of food parks to support processing industries with shared infrastructure.

Cluster-Based Development: Promotion of crop-specific clusters like the mustard cluster in Bharatpur and spice cluster in Jodhpur.

Subsidies for Startups: Financial support for agri-tech startups and small-scale food processing units.

The Role of Technology in Driving Growth

1. Precision Farming

Use of drones, IoT devices, and satellite imagery for better crop management.

2. Food Processing Automation

Adoption of automated equipment for sorting, grading, and packaging ensures efficiency and quality.

3. Blockchain in Agri-Supply Chains

Enhancing transparency and traceability from farm to fork.

4. Digital Marketplaces

Platforms like eNAM are helping farmers connect directly with buyers, ensuring better prices.

Col Rajyavardhan Rathore: Advocating for Agri-Business Growth

Col Rathore has been a strong advocate for leveraging Rajasthan’s agricultural strengths to create employment and boost the economy. His initiatives include:

Promoting Agri-Entrepreneurship: Encouraging youth to explore opportunities in modern farming and food processing.

Farmer Outreach Programs: Regular interactions with farmers to address challenges and introduce them to new technologies.

Policy Advocacy: Ensuring that government policies align with the needs of farmers and agri-businesses.

Challenges and Solutions in the Sector

Challenges

Water Scarcity: Dependence on rain-fed agriculture in many regions.

Post-Harvest Losses: Lack of proper storage and transportation facilities.

Market Access: Difficulty in connecting small farmers to larger markets.

Solutions

Drip Irrigation and Water Conservation: Efficient irrigation methods to tackle water scarcity.

Investment in Cold Chains: Preventing wastage of perishable goods.

Digital Platforms for Farmers: Expanding access to markets through e-commerce and digital supply chains.

A Promising Future for Agri & Food Processing in Rajasthan

Rajasthan is poised to become a leader in the agriculture and food processing sector, thanks to its diverse produce, supportive policies, and visionary leadership. With growing investments and technological advancements, the state offers endless opportunities for entrepreneurs and businesses.

Under the guidance of leaders like Col Rajyavardhan Rathore, Rajasthan is moving steadily toward a future where its agricultural wealth is fully harnessed to benefit farmers, consumers, and the economy at large.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rising Rajasthan Global Investment Summit 2024: Col Rajyavardhan Rathore

The Rising Rajasthan Global Investment Summit 2024 commenced on December 9, 2024, in Jaipur, inaugurating a three-day event aimed at showcasing Rajasthan’s potential as a premier investment destination. The summit brings together global investors, industry leaders, and policymakers to explore opportunities across various sectors.

The Rising Rajasthan Global Investment Summit 2024, held in Jaipur, has set the stage for Rajasthan’s emergence as a global investment powerhouse. With leaders, entrepreneurs, and policymakers converging to envision a brighter economic future, the summit reflects the state’s ambitions to lead in innovation and growth. Colonel Rajyavardhan Rathore, a prominent voice in Rajasthan’s development, highlighted the transformative potential of this landmark event.

Rajasthan: A Land of Opportunities

Known for its rich heritage and cultural diversity, Rajasthan is now making significant strides in economic development. The state, with its abundant resources and strategic location, aims to attract global investors by showcasing its potential in various sectors.

Key Objectives of the Summit

1. Attracting Investments Across Sectors

The summit focuses on industries such as renewable energy, tourism, IT, startups, and agriculture, providing a platform for stakeholders to explore collaborations.

2. Promoting Sustainable Development

With a strong emphasis on sustainability, the summit aims to balance economic growth with environmental responsibility, positioning Rajasthan as a leader in green energy.

3. Creating Employment Opportunities

By facilitating large-scale investments, the event is expected to generate thousands of jobs, particularly for Rajasthan’s youth.

Highlights of the Event

1. Inauguration by PM Narendra Modi

The summit was inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who emphasized Rajasthan’s potential as a global investment destination and unveiled key development projects.

2. Col Rajyavardhan Rathore’s Visionary Leadership

Col Rathore played a pivotal role in organizing the summit, aligning it with the aspirations of Rajasthan’s people. In his address, he stated: “Rajasthan is ready to redefine its economic landscape. This summit is a testament to our resilience and readiness to lead.”

3. International Participation

Delegates from over 25 countries attended, bringing a global perspective to discussions and forging international partnerships.

4. Policy Announcements

The Rajasthan government unveiled investor-friendly policies, including tax incentives, streamlined approval processes, and infrastructure development plans.

Key Sectors in Focus

1. Renewable Energy

Rajasthan, with its abundant solar and wind resources, is a prime location for green energy projects. The summit highlighted initiatives to make the state a leader in renewable energy.

2. Tourism and Heritage

The event underscored Rajasthan’s potential as a global tourism hub, with investments aimed at upgrading infrastructure while preserving its cultural heritage.

3. Startups and IT

Encouraging innovation and technology, the summit showcased the state’s burgeoning startup ecosystem and plans for IT hubs.

4. Agro-Industries

The agricultural sector remains a cornerstone of Rajasthan’s economy, and the summit focused on modernizing agro-industries and boosting food processing.

Impact on Rajasthan’s Economy

Billions in Investment Commitments

The summit secured substantial investment pledges, set to drive economic growth and industrialization across the state.

Infrastructure Development

Key projects, including industrial parks and improved connectivity, were announced to enhance Rajasthan’s appeal to investors.

Job Creation and Skill Development

With new industries entering the state, a significant boost in employment opportunities is anticipated, along with initiatives to upskill the workforce.

Col Rajyavardhan Rathore: A Catalyst for Change

As a visionary leader, Col Rajyavardhan Rathore has been instrumental in Rajasthan’s development journey. His relentless efforts to attract investments and empower local communities have made him a key figure in the state’s transformation.

A Bright Future for Rajasthan

The Rising Rajasthan Global Investment Summit 2024 marks a turning point in the state’s economic narrative. With strategic leadership from personalities like Col Rajyavardhan Rathore and support from the central government, Rajasthan is poised to achieve unprecedented growth and prosperity. The summit is not just an event but a milestone in Rajasthan’s journey toward global recognition as a leading investment hub.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Farmers in Greece and Romania are protesting, joining a wave of unrest in the farming community that has affected several countries in Europe.

In Karditsa, Evros, Patras, Peloponnese, and in Serres, northern Greece, farmers took to the streets on Wednesday with tractors. They have also threatened to close highways, media reported.

A bigger demonstration is planned for Friday in Thessaloniki on the occasion of the 30th Agrotica, the largest exhibition of the agro-economic sector in the country. Farmers warn that if the government does nothing by next Monday, roads will be closed.

Government spokesman Pavlos Marinakis said things should not go to such extremes. “No matter how serious the demands of a professional group are, they must not lead to the punishment of all citizens and violate the rights of society. This government has proven that it is trying, without leading to extreme tension, to solve problems,” Marinakis told the public broadcaster ERT.

Farmers, among others, demand compensation for those who haven’t received it for the damage caused by Storm Daniel, which destroyed houses, businesses, animal and plant production and roads in Thessaly region in September.

They want the construction of infrastructure projects to protect against weather phenomena, reductions in production costs and a change in the Agricultural Insurance Organisation’s regulation so that the production and capital are compensated 100 per cent for all such risks.

The Ministry of Climate Crisis and Civil Protection has already granted 33.9 million euros to 16,400 agricultural holdings and livestock units that applied for “first aid,” with payments to be completed in the next period. PM Kyriakos Mitsotakis said there will be a second cycle of aid worth 5,000 to 10,000 euros for farmers affected by the extreme flooding of September 2023 in Thessaly and other areas.

Farmers in Romania meanwhile continue to protest and demand relief from high fuel and insurance prices and better selling prices for their products. The government has devised some solutions to the demands, but many are unconvinced and continue to protest.

Large-scale protests took place on Tuesday in Brasov and Sibiu, central Romania, whwre farmers took 50 agricultural machines to the streets and staged a march. An authorized protest was also organised by farmers from Sibiu, who started in a column with tractors, trucks and cars across the municipality.

Such protests are taking place in all major cities in Romania, including on the ring road of Bucharest, where farmers have been protesting for weeks and hindering traffic. They were not allowed to enter Bucharest to protest in front of the government building to avoid disrupting the already heavy traffic in the capital.

Farmers in France, Belgium and Germany have been holding demonstrations blocking highways, with Reuters reporting that Spanish and Italian farmers will now join the movement.

They are complaining about EU measures to create “solidarity corridors” in order to provide Ukraine with income from agricultural exports, especially wheat. These products have flooded neighbouring countries and caused local production prices to fall.

The protesters also demand the cancellation of measures to limit agricultural production due to its carbon footprint and affect on climate change. They want the restoration of fuel tax exemptions. Far-right parties in Germany and in France have expressed vocal support for farmers’ demands.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Driven by utilitarian concerns with scarcity and fears of cascading environmental degradation, colonial officials implemented tree-planting programs of all sorts -- seed farms, erosion control projects, school forests and so on. [...] Imperial forestry describes a shared set of practices, convictions and institutions that bound Japanese forestry professionals into a network that spanned the Japanese empire itself. [...] Japanese woodsmen (with a venerable forestry tradition all their own) came to terms with Western notions of natural resource management and "scientific forestry." [...] Japanese foresters tailored European ideas about ecology, sustainability, and industrial development to the particular needs of the Japanese empire and the different biomes it encompassed. [...] Japan has played an outsized role in the management and control of Asia's forests. To understand how Japan has maintained such verdant hillsides at home, [...] we need to more fully appreciate its control of sylvan landscapes abroad -- be they in the colonial empire before 1945 or in Southeast Asia thereafter. [...] [W]e ought to place tenant farmers in colonial Korea and shifting cultivators in Kalimantan in the same analytical frame. [...]

---

The most obvious legacies are material: flora introduced during colonial occupation that still grow in Korea today. [...] As part of a campaign to supposedly "beautify" the Korean landscape [...], Japanese settlers planted [...] cherry blossoms along streets, in squares, and within parks across Korea. [...] Another impact can be found in the forestry institutions founded during colonial rule. The flagship Forestry Research Station established by the colonial government, for example, only grew after liberation, becoming a hub of agro-forestry research that underpinned South Korea's economic take-off under Park Chung-hee. Many of the architects of South Korea's so-called "forest miracle" -- the wildly successful project of reforestation in the 1960s and 70s -- were trained in colonial scientific institutions. This is not to suggest that the dense forests that today blanket South Korea are somehow due to colonial rule. Reforestation under Park was born of markedly different circumstances -- its Cold War context, authoritarian rule and energy portfolio. But that doesn't mean that foresters on either side of 1945 weren't united by the same sets of anxieties and aspirations. [...] [A] set of abiding concerns [...] have animated forest conservation measures across the full sweep of the tumultuous twentieth century in Korea. [...]

---

[R]eferences to the ondol (the radiant heated floors conventional to Korean dwellings) are everywhere in the forester's archive. Japanese woodsmen quickly marked the ondol and its associated lifestyle as ground zero of deforestation. By the 1920s, forestry officials had launched an ambitious campaign to gain control over the energy consumption patterns of the home -- a crusade on caloric inefficiency that furthered the reach of the colonial state into the domestic sphere. In this sense, the ondol provides an illuminating lens through which to examine how forestry touched the lived, even bodily, experience of colonial rule in a sometimes bitterly cold environment. This is especially true of the civilian experience of the Asia-Pacific War in Korea, a period of fuel scarcity that resulted in draconian programs of caloric control. [...]

[W]e have much to gain by looking beyond the boundaries of the islands of Japan to write its environmental history. Understanding the tree-smothered hillsides of the so-called "green archipelago" requires that we pay close attention to its material linkages with the rest of Asia. It demands that we track commodity chains, supply lines, and resource politics across the Pacific.

---

All words above are the words of David Feldman. As interviewed and transcribed by Office of the Dean, School of Humanities at University of California, Irvine. Transcript titled “Seeing the forest for the trees.” Published online in the News section of UCI School of Humanities. 21 May 2020. [Some paragraph breaks and contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: The Employment System in Bihar: Challenges and OpportunitiesIntroduction: Bihar, a state in eastern India, has a unique employment landscape characterized by its demographic diversity and a mix of challenges and opportunities. In this blog, we will delve into the key aspects of Bihar's employment system, highlighting the state's strengths and areas that require improvement.Demographics and Workforce: Bihar boasts a large and youthful population, making it a potential labor powerhouse. The state's workforce comprises a mix of skilled and unskilled labor, contributing to various sectors of the economy.Government Initiatives: The Bihar government has initiated several programs to enhance employment prospects. Some of the notable schemes include:Mukhyamantri Nischay Swayam Sahayata Bhatta Yojana (MNSSBY): A financial assistance program for unemployed youth.Jeevika: A self-help group program promoting women's entrepreneurship and livelihoods.Skill Development Initiatives: Efforts to improve the skills of the youth for better employability.Challenges in Bihar's Employment System: Despite the potential, Bihar faces various challenges in its employment landscape, including:Low Industrialization: A limited industrial base compared to its population size.Agriculture Dominance: A significant reliance on agriculture, which is vulnerable to climate-related risks.Migration: Seasonal migration of labor to other states for employment opportunities.Opportunities: There are promising opportunities in Bihar's employment system:Agro-Based Industries: Leveraging the state's rich agricultural resources for agro-processing and food industries.Education and Skill Development: Investing in education and skill development to create a skilled workforce.Infrastructure Development: Building infrastructure to attract investments and create job opportunities.Conclusion: Bihar's employment system is a complex landscape with both challenges and opportunities. With strategic planning, skill development, and investment in key sectors, the state can harness the potential of its young and diverse workforce to drive economic growth and improve employment prospects for its citizens.Disclaimer: This information is based on data available up to September 2021. For the most up-to-date information, please refer to official government sources and recent news articles.

Here are the glimpse of some employees working for Automobile industry.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indigenous groups go after Lula coalition amid veto vote

With Congress set to analyze a presidential veto of a landmark indigenous land bill this week, Brazil’s Indigenous People Articulation (Apib) has launched a manifesto decrying the “anti-indigenous” sectors of the current governing coalition, affirming that traditional communities’ rights are “non-negotiable.”

In September, pro-agro sectors of Congress pushed through a bill establishing the so-called “time-frame argument” for indigenous land claims in Brazil. Said argument stipulates that traditional communities would only be able to demand ownership of territory if they could prove that they effectively inhabited it on October 5, 1988 — the day Brazil’s current Constitution was enacted.

The approval was in direct response to a Supreme Court decision that ruled the time-frame argument as unconstitutional. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva vetoed most of the bill in October, and Congress is set to ratify or overrule those vetoes this week.

While Apib hails Lula’s election last year as a “collective achievement,” it complains that the electoral context forced him to form a “broad ideological alliance, encompassing conservative and anti-indigenous economic and political sectors.”

Continue reading.

#brazil#brazilian politics#politics#environmental justice#indigenous rights#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

🇧🇪 Princess Astrid of Belgium, Archduchess of Austria-Este

Tuesday, May 23, 2023

“The first Belgian economic mission to Senegal started yesterday under the leadership of Princess Astrid. The aim is to strengthen economic and trade relations with the country, which is an important gateway to West Africa.

Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hadja Lahbib, Vice President of the Wallace Government, Willy Borsus, and Brussels Secretary of State, Pascal Smet, are on the mission, as are 155 Belgian companies and various academic institutions.

The mission will visit Dakar, Diamniado and the Fatick-Mbellacadiao region and will focus on a number of key sectors: logistics, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, agro-food, renewable energy, water management, environment and creative industries.

After an opening seminar on women entrepreneurship, in the presence of the Senegalese Minister of Foreign Affairs, Aïssata Tall Sall, the official Belgian delegation yesterday met with President Macky Sall and Prime Minister Amadou Ba.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

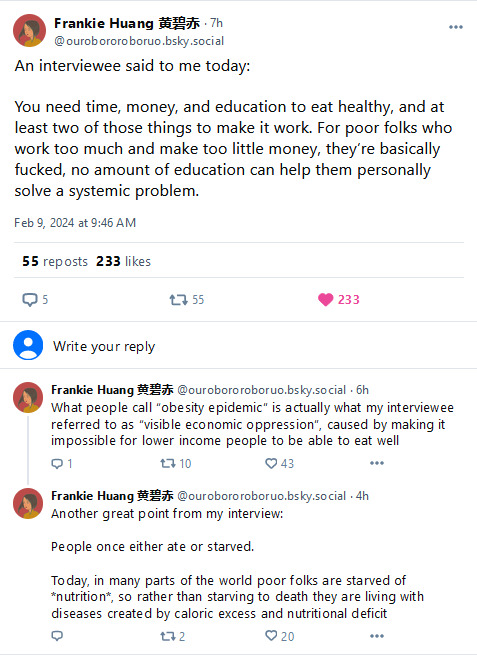

They're absolutely right. 'Personal responsibility' is, in this context, a rightoid made-up talking point for the sole purpose of shielding certain financial interests.

Like we also have to talk about the 'production' side of things. Big Agro is a blight upon the Earth and upon humanity as a whole.

Oligarchs' and latifundists' production techniques are not predicated on providing, say, NUTRITIOUS CROPS/FOOD or anything like that. God forbid. Instead, they've linked up with gigantic multinational and national trash food companies to absolutely dominate all food supply chains. That is to say, they make sure that not only you consume their product, but that you have NO OTHER CHOICE. That's (partly) why food deserts exist.

Of course healthy food is going to be expensive if most of the prime agricultural land is dedicated to cultivating bottom-of-the-barrel crops like African palm and sugar cane. They aren't just taking space, they're actively STEALING it. The whole industry is build on unethical colonization techniques and heritage.

Of course the 'obesity epidemic' is going to be a thing if all the food production systems and chains are an absolute disaster only meant to extract maximum value from land until it's absolutely fucked and left barren for generations to come, leaving the mess to the people who originally lived there while the corps move on to annihilate some other land area. The absolute distortion of economic and ethical priorities thanks to capitalism is having nefarious effects on our health from all sides.

I don't know what that person was interviewing for but I hope they got it, because bullseye.

#i hope you get the point. fuck agro#nothing is isolated. food production impacts us all directly#also Big Food has such a cultural stronghold on all of us that it's crazy to even think about#apart from the financial aspects they're deliberately pushing misinfo EVERYWHERE#too bad bocado.lat went down. it was a goldmine of a site that exposed A LOT

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

I.3.5 What would confederations of syndicates do?

Voluntary confederation among syndicates is considered necessary by social anarchists for numerous reasons but mostly in order to decide on the policies governing relations between syndicates and to co-ordinate their activities. This could vary from agreeing technical standards, to producing guidelines and policies on specific issues, to agreeing major investment decisions or prioritising certain large-scale economic projects or areas of research. In addition, they would be the means by which disputes could be solved and any tendencies back towards capitalism or some other class society identified and acted upon.

This can be seen from Proudhon, who was the first to suggest the need for such federations. “All my economic ideas developed over the last twenty-five years,” he stated, “can be defined in three words: Agro-industrial federation” This was required because ”[h]owever impeccable in its basic logic the federal principle may be … it will not survive if economic factors tend persistently to dissolve it. In other words, political right requires to be buttressed by economic right”. A free society could not survive if “capital and commerce” existed, as it would be “divided into two classes — one of landlords, capitalists, and entrepreneurs, the other of wage-earning proletarians, one rich, the other poor.” Thus “in an economic context, confederation may be intended to provide reciprocal security in commerce and industry … The purpose of such specific federal arrangements is to protect the citizens … from capitalist and financial exploitation, both from within and from the outside; in their aggregate they form … an agro-industrial federation” [The Principle of Federation, p. 74, p. 67 and p. 70]

While capitalism results in “interest on capital” and “wage-labour or economic servitude, in short inequality of condition”, the “agro-industrial federation … will tend to foster increasing equality … through mutualism in credit and insurance … guaranteeing the right to work and to education, and an organisation of work which allows each labourer to become a skilled worker and an artist, each wage-earner to become his own master.” The “industrial federation” will apply “on the largest scale” the “principles of mutualism” and “economic solidarity”. As “industries are sisters”, they “are parts of the same body” and “one cannot suffer without the others sharing in its suffering. They should therefore federate … in order to guarantee the conditions of common prosperity, upon which no one has an exclusive claim.” Thus mutualism sees “all industries guaranteeing one another mutually” as well as “organising all public services in an economical fashion and in hands other than the state’s.” [Op. Cit., p. 70, p. 71, p. 72 and p. 70]

Later anarchists took up, built upon and clarified these ideas of economic federation. There are two basic kinds of confederation: an industrial one (i.e., a federation of all workplaces of a certain type) and a regional one (i.e. a federation of all syndicates within a given economic area). Thus there would be a federation for each industry and a federation of all syndicates in a geographical area. Both would operate at different levels, meaning there would be confederations for both industrial and inter-industrial associations at the local and regional levels and beyond. The basic aim of this inter-industry and cross-industry networking is to ensure that the relevant information is spread across the various parts of the economy so that each can effectively co-ordinate its plans with the others in a way which minimises ecological and social harm. Thus there would be a railway workers confederation to manage the rail network but the local, regional and national depots and stations would send a delegate to meet regularly with the other syndicates in the same geographical area to discuss general economic issues.

However, it is essential to remember that each syndicate within the confederation is autonomous. The confederations seek to co-ordinate activities of joint interest (in particular investment decisions for new plant and the rationalisation of existing plant in light of reduced demand). They do not determine what work a syndicate does or how they do it:

“With the factory thus largely conducting its own concerns, the duties of the larger Guild organisations [i.e. confederations] would be mainly those of co-ordination, or regulation, and of representing the Guild in its external relations. They would, where it was necessary, co-ordinate the production of various factories, so as to make supply coincide with demand… they would organise research … This large Guild organisation… must be based directly on the various factories included in the Guild.” [Cole, Guild Socialism Restated, pp. 59–60]

So it is important to note that the lowest units of confederation — the workers’ assemblies — will control the higher levels, through their power to elect mandated and recallable delegates to meetings of higher confederal units. It would be fair to make the assumption that the “higher” up the federation a decision is made, the more general it will be. Due to the complexity of life it would be difficult for federations which cover wide areas to plan large-scale projects in any detail and so would be, in practice, more forums for agreeing guidelines and priorities than planning actual specific projects or economies. As Russian anarcho-syndicalist G.P. Maximov put it, the aim “was to co-ordinate all activity, all local interest, to create a centre but not a centre of decrees and ordinances but a centre of regulation, of guidance — and only through such a centre to organise the industrial life of the country.” [quoted by M. Brinton, For Workers’ Power, p. 330]

So this is a decentralised system, as the workers’ assemblies and councils at the base having the final say on all policy decisions, being able to revoke policies made by those with delegated decision-making power and to recall those who made them:

“When it comes to the material and technical method of production, anarchists have no preconceived solutions or absolute prescriptions, and bow to what experience and conditions in a free society recommend and prescribe. What matters is that, whatever the type of production adopted, it should be the free choice of the producers themselves, and cannot possibly be imposed, any more than any form is possible of exploitations of another’s labour… Anarchists do not a priori exclude any practical solution and likewise concede that there may be a number of different solutions at different times.” [Luigi Fabbri, “Anarchy and ‘Scientific’ Communism”, pp. 13–49, The Poverty of Statism, Albert Meltzer (ed.), p. 22]

Confederations would exist for specific reasons. Mutualists, as can be seen from Proudhon, are aware of the dangers associated with even a self-managed, socialistic market and create support structures to defend workers’ self-management. Moreover, it is likely that industrial syndicates would be linked to mutual banks (a credit syndicate). Such syndicates would exist to provide interest-free credit for self-management, new syndicate expansion and so on. And if the experience of capitalism is anything to go by, mutual banks will also reduce the business cycle as ”[c]ountries like Japan and Germany that are usually classifies as bank-centred — because banks provide more outside finance than markets, and because more firms have long-term relationships with their banks — show greater growth in and stability of investment over time than the market-centred ones, like the US and Britain … Further, studies comparing German and Japanese firms with tight bank ties to those without them also show that firms with bank ties exhibit greater stability in investment over the business cycle.” [Doug Henwood, Wall Street, pp. 174–5]

One argument against co-operatives is that they do not allow the diversification of risk (all the worker’s eggs are on one basket). Ignoring the obvious point that most workers today do not have shares and are dependent on their job to survive, this objection can be addressed by means of “the horizontal association or grouping of enterprises to pool their business risk. The Mondragon co-operatives are associated together in a number of regional groups that pool their profits in varying degrees. Instead of a worker diversifying his or her capital in six companies, six companies partially pool their profits in a group or federation and accomplish the same risk-reduction purpose without transferable equity capital.” Thus “risk-pooling in federations of co-operatives” ensure that “transferable equity capital is not necessary to obtain risk diversification in the flow of annual worker income.” [David Ellerman, The Democratic Worker-Owned Firm, p. 104] Moreover, as the example of many isolated co-operatives under capitalism have shown, support networks are essential for co-operatives to survive. It is no co-incidence that the Mondragon co-operative complex in the Basque region of Spain has a credit union and mutual support networks between its co-operatives and is by far the most successful co-operative system in the world. The “agro-industrial federation” exists precisely for these reasons.

Under collectivist and communist anarchism, the federations would have addition tasks. There are two key roles. Firstly, the sharing and co-ordination of information produced by the syndicates and, secondly, determining the response to the changes in production and consumption indicated by this information.

Confederations (negotiated-co-ordination bodies) would be responsible for clearly defined branches of production, and in general, production units would operate in only one branch of production. These confederations would have direct links to other confederations and the relevant communal confederations, which supply the syndicates with guidelines for decision making (see section I.4.4) and ensure that common problems can be highlighted and discussed. These confederations exist to ensure that information is spread between workplaces and to ensure that the industry responds to changes in social demand. In other words, these confederations exist to co-ordinate major new investment decisions (i.e. if demand exceeds supply) and to determine how to respond if there is excess capacity (i.e. if supply exceeds demand).

It should be pointed out that these confederated investment decisions will exist along with the investments associated with the creation of new syndicates, plus internal syndicate investment decisions. We are not suggesting that every investment decision is to be made by the confederations. (This would be particularly impossible for new industries, for which a confederation would not exist!) Therefore, in addition to co-ordinated production units, an anarchist society would see numerous small-scale, local activities which would ensure creativity, diversity, and flexibility. Only after these activities had spread across society would confederal co-ordination become necessary. So while production will be based on autonomous networking, the investment response to consumer actions would, to some degree, be co-ordinated by a confederation of syndicates in that branch of production. By such means, the confederation can ensure that resources are not wasted by individual syndicates over-producing goods or over-investing in response to changes in production. By communicating across workplaces, people can overcome the barriers to co-ordinating their plans which one finds in market systems (see section C.7.2) and so avoid the economic and social disruptions associated with them.

Thus, major investment decisions would be made at congresses and plenums of the industry’s syndicates, by a process of horizontal, negotiated co-ordination. Major investment decisions are co-ordinated at an appropriate level, with each unit in the confederation being autonomous, deciding what to do with its own productive capacity in order to meet social demand. Thus we have self-governing production units co-ordinated by confederations (horizontal negotiation), which ensures local initiative (a vital source of flexibility, creativity, and diversity) and a rational response to changes in social demand. As links between syndicates are non-hierarchical, each syndicate remains self-governing. This ensures decentralisation of power and direct control, initiative, and experimentation by those involved in doing the work.

It should be noted that during the Spanish Revolution successfully federated in different ways. Gaston Leval noted that these forms of confederation did not harm the libertarian nature of self-management:

“Everything was controlled by the syndicates. But it must not therefore be assumed that everything was decided by a few higher bureaucratic committees without consulting the rank and file members of the union. Here libertarian democracy was practised. As in the C.N.T. there was a reciprocal double structure; from the grass roots at the base … upwards, and in the other direction a reciprocal influence from the federation of these same local units at all levels downwards, from the source back to the source.” [The Anarchist Collectives, p. 105]

The exact nature of any confederal responsibilities will vary, although we “prefer decentralised management; but ultimately, in practical and technical problems, we defer to free experience.” [Luigi Fabbri, Op. Cit., p. 24] The specific form of organisation will obviously vary as required from industry to industry, area to area, but the underlying ideas of self-management and free association will be the same. Moreover, the “essential thing … is that its [the confederation or guild] function should be kept down to the minimum possible for each industry.” [Cole, Op. Cit., p. 61]

Another important role for inter-syndicate federations is to even-out inequalities. After all, each area will not be identical in terms of natural resources, quality of land, situation, accessibility, and so on. Simply put, social anarchists “believe that because of natural differences in fertility, health and location of the soil it would be impossible to ensure that every individual enjoyed equal working conditions.” Under such circumstances, it would be “impossible to achieve a state of equality from the beginning” and so “justice and equity are, for natural reasons, impossible to achieve … and that freedom would thus also be unachievable.” [Malatesta, The Anarchist Revolution, p. 16 and p. 21]

This was recognised by Proudhon, who saw the need for economic federation due to differences in raw materials, quality of land and so on, and as such argued that a portion of income from agricultural produce be paid into a central fund which would be used to make equalisation payments to compensate farmers with less favourably situated or less fertile land. As he put it, economic rent “in agriculture has no other cause than the inequality in the quality of land … if anyone has a claim on account of this inequality … [it is] the other land workers who hold inferior land. That is why in our scheme for liquidation [of capitalism] we stipulated that every variety of cultivation should pay a proportional contribution, destined to accomplish a balancing of returns among farm workers and an assurance of products.” In addition, “all the towns of the Republic shall come to an understanding for equalising among them the quality of tracts of land, as well as accidents of culture.” [General Idea of the Revolution, p. 209 and p. 200]

By federating together, workers can ensure that “the earth will … be an economic domain available to everyone, the riches of which will be enjoyed by all human beings.” [Malatesta, Errico Malatesta: His Life and Ideas, p. 93] Local deficiencies of raw materials, in the quality of land, and, therefore, supplies would be compensated from outside, by the socialisation of production and consumption. This would allow all of humanity to share and benefit from economic activity, so ensuring that well-being for all is possible.