#Afro Congo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#capitalism#palestine#economy#imperialism#colonialism#israel#congo genocide#genocide#africa#marginalization#marginalizedcommunities#marginalized groups#marginalized people#black women#black voices#afrofuturism#melanin#afrocentric#afropessimism#afro surrealism#amplify#leftist#socialism#communism#anarchist#left wing#anti capitalism#white leftists#yt#uplifting

440 notes

·

View notes

Text

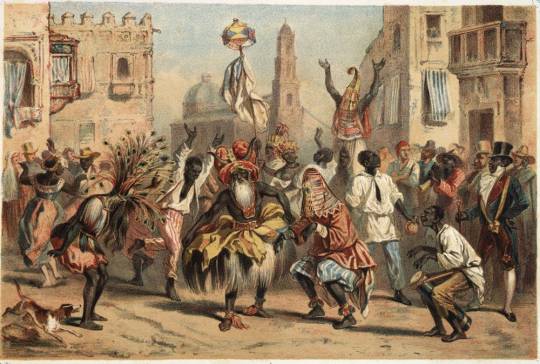

Music of African heritage in Cuba derives from the musical traditions of the many ethnic groups from different parts of West and Central Africa that were brought to Cuba as slaves between the 16th and 19th centuries. Members of some of these groups formed their own ethnic associations or cabildos, in which cultural traditions were conserved, including musical ones. Music of African heritage, along with considerable Iberian (Spanish) musical elements, forms the fulcrum of Cuban music.

Much of this music is associated with traditional African religion – Lucumi, Palo, and others – and preserves the languages formerly used in the African homelands. The music is passed on by oral tradition and is often performed in private gatherings difficult for outsiders to access. Lacking melodic instruments, the music instead features polyrhythmic percussion, voice (call-and-response), and dance. As with other musically renowned New World nations such as the United States, Brazil and Jamaica, Cuban music represents a profound African musical heritage.

Clearly, the origin of African groups in Cuba is due to the island's long history of slavery. Compared to the USA, slavery started in Cuba much earlier and continued for decades afterwards. Cuba was the last country in the Americas to abolish the importation of slaves, and the second last to free the slaves. In 1807 the British Parliament outlawed slavery, and from then on the British Navy acted to intercept Portuguese and Spanish slave ships. By 1860 the trade with Cuba was almost extinguished; the last slave ship to Cuba was in 1873. The abolition of slavery was announced by the Spanish Crown in 1880, and put into effect in 1886. Two years later, Brazil abolished slavery.

Although the exact number of slaves from each African culture will never be known, most came from one of these groups, which are listed in rough order of their cultural impact in Cuba:

The Congolese from the Congo Basin and SW Africa. Many ethnic groups were involved, all called Congos in Cuba. Their religion is called Palo. Probably the most numerous group, with a huge influence on Cuban music.

The Oyó or Yoruba from modern Nigeria, known in Cuba as Lucumí. Their religion is known as Regla de Ocha (roughly, 'the way of the spirits') and its syncretic version is known as Santería. Culturally of great significance.

The Kalabars from the Southeastern part of Nigeria and also in some part of Cameroon, whom were taken from the��Bight of Biafra. These sub Igbo and Ijaw groups are known in Cuba as Carabali,and their religious organization as Abakuá. The street name for them in Cuba was Ñáñigos.

The Dahomey, from Benin. They were the Fon, known as Arará in Cuba. The Dahomeys were a powerful group who practised human sacrifice and slavery long before Europeans arrived, and allegedly even more so during the Atlantic slave trade.

Haiti immigrants to Cuba arrived at various times up to the present day. Leaving aside the French, who also came, the Africans from Haiti were a mixture of groups who usually spoke creolized French: and religion was known as vodú.

From part of modern Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire came the Gangá.

Senegambian people (Senegal, the Gambia), but including many brought from Sudan by the Arab slavers, were known by a catch-all word: Mandinga. The famous musical phrase Kikiribu Mandinga! refers to them.

Subsequent organization

The roots of most Afro-Cuban musical forms lie in the cabildos, self-organized social clubs for the African slaves, and separate cabildos for separate cultures. The cabildos were formed mainly from four groups: the Yoruba (the Lucumi in Cuba); the Congolese (Palo in Cuba); Dahomey (the Fon or Arará). Other cultures were undoubtedly present, more even than listed above, but in smaller numbers, and they did not leave such a distinctive presence.

Cabildos preserved African cultural traditions, even after the abolition of slavery in 1886. At the same time, African religions were transmitted from generation to generation throughout Cuba, Haiti, other islands and Brazil. These religions, which had a similar but not identical structure, were known as Lucumi or Regla de Ocha if they derived from the Yoruba, Palo from Central Africa, Vodú from Haiti, and so on. The term Santería was first introduced to account for the way African spirits were joined to Catholic saints, especially by people who were both baptized and initiated, and so were genuine members of both groups. Outsiders picked up the word and have tended to use it somewhat indiscriminately. It has become a kind of catch-all word, rather like salsa in music.

The ñáñigos in Cuba or Carabali in their secret Abakuá societies, were one of the most terrifying groups; even other blacks were afraid of them:

Girl, don't tell me about the ñáñigos! They were bad. The carabali was evil down to his guts. And the ñáñigos from back in the day when I was a chick, weren't like the ones today... they kept their secret, like in Africa.

African sacred music in Cuba

All these African cultures had musical traditions, which survive erratically to the present day, not always in detail, but in the general style. The best preserved are the African polytheistic religions, where, in Cuba at least, the instruments, the language, the chants, the dances and their interpretations are quite well preserved. In few or no other American countries are the religious ceremonies conducted in the old language(s) of Africa, as they are at least in Lucumí ceremonies, though of course, back in Africa the language has moved on. What unifies all genuine forms of African music is the unity of polyrhythmic percussion, voice (call-and-response) and dance in well-defined social settings, and the absence of melodic instruments of an Arabic or European kind.

Not until after the Second World War do we find detailed printed descriptions or recordings of African sacred music in Cuba. Inside the cults, music, song, dance and ceremony were (and still are) learnt by heart by means of demonstration, including such ceremonial procedures conducted in an African language. The experiences were private to the initiated, until the work of the ethnologist Fernando Ortíz, who devoted a large part of his life to investigating the influence of African culture in Cuba. The first detailed transcription of percussion, song and chants are to be found in his great works.

There are now many recordings offering a selection of pieces in praise of, or prayers to, the orishas. Much of the ceremonial procedures are still hidden from the eyes of outsiders, though some descriptions in words exist.

Yoruba and Congolese rituals

Main articles: Yoruba people, Lucumi religion, Kongo people, Palo (religion), and Batá

Religious traditions of African origin have survived in Cuba, and are the basis of ritual music, song and dance quite distinct from the secular music and dance. The religion of Yoruban origin is known as Lucumí or Regla de Ocha; the religion of Congolese origin is known as Palo, as in palos del monte.[11] There are also, in the Oriente region, forms of Haitian ritual together with its own instruments and music.

In Lucumi ceremonies, consecrated batá drums are played at ceremonies, and gourd ensembles called abwe. In the 1950s, a collection of Havana-area batá drummers called Santero helped bring Lucumí styles into mainstream Cuban music, while artists like Mezcla, with the lucumí singer Lázaro Ros, melded the style with other forms, including zouk.

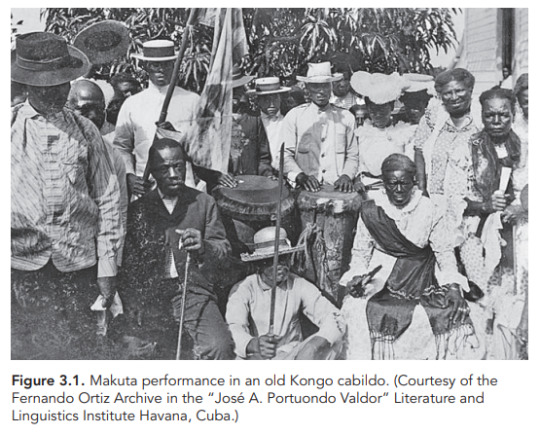

The Congo cabildo uses yuka drums, as well as gallos (a form of song contest), makuta and mani dances. The latter is related to the Brazilian martial dance capoeira

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#african culture#fitness#afrakan spirituality#afro cuban music#afro cuban#igbo#yoruba#congo#african music

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Des pierres chargées électriquement découvertes en République démocratique du Congo (RDC).

C’est pourquoi ils ne permettront jamais au Congo de devenir pacifique, en raison de ses riches minerais.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brown liquor, brown sugar, brown face

Brown liquor, brown sugar, brown face

Black skin, black Benz, black plays

Black molasses, blackberry the masses

Just sittin’ here foolin’ around

We just sittin’ here coolin’ around

We just sittin’ here high, coming down

— Almeda, Solange ft. Playboi Carti

#letz-smoke-zaza#this is a girlblog#girlblogging#girlblogger#black girlblogger#happy juneteenth#juneteenth#africa#afro american#black skin#almeda#solange knowles#gold#fruits#summer#divine feminine#brown sugar#free congo#free sudan#free palestine#dark skin#brown skin#anti colonialism#colorism#every month is black month#brown liquor#moodboard#summer moodboard#black people#woc

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Congo faces

#african beauty#african style#african women#african fashion#dark skin beauty#afro sexy#portrait photography#african smile#curly hair#african braids#congolese#congolaise#congo#beautiful black women

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the album Congolese Funk, Afrobeat & Psychedelic Rumba 1969 - 1978 via Analog Africa - essential!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like I should be doing more than I am. like I told myself I was doing what I could with donating and sharing links, but now I feel like I should be capable of more. I see people doing art and raffles for Palestine and Sudan and Congo and like... It took so much effort doing the three I did, so I can't confidently do commissions. Maybe I could come up with an art for someone's GFM? I've seen that, and (unfortunately) it seems like people care more when posts have art. But my art is kinda goofy and doesn't feel serious enough for drawing people 😬. I wanna contribute to something though.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Instagram: Caroline.manya

#africanbeauty#black women#black girl magic#africa#congolese#beauty#black beauty#classy black women#modelling#afrique#congolaise#democratic republic of the congo#jawline#braids#fulani#afro hair#african princess#african beauty#african it girl#black girl#black girls are beautiful#beautiful black women#almond eyes#almond#supermodel aesthetic#black supermodels#black it girl#black makeup#blackgirlsmagic#90s supermodels

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palo Mayombe: Kongo-derived Afro-Cuban Spirituality — Lawrence Talks!

“This complexity described in the Bantu-Kongo word for person, muntu is a ‘set of concrete social relationships ... a system of systems; the pattern of patterns in being.’ The person is contextualized as a system participating in other systems, a pattern, a ripple that is sourced and from a source.”

— Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, African Cosmology 42

Dr. Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, a Congolese native and scholar of African religion, captures the essence of Kongo cosmology with this quote, and from this cosmological structure lies the roots of the African diasporic religion Palo Mayombe. Just as a person is “a system of systems; the pattern of patterns in being,” ancestral reverence and inclusion positions humans through a multitude of bodies that have come before them. Ancestral veneration is at the core of many African Diasporic spiritualities. Many individuals who grew up in traditional Christian churches are leaving beliefs of Christendom in search for traditional religions that help them connect with their ancestors. Religious and spiritual systems like Ifa, Santeria, Vodou and Conjure have been popularized, sometimes in negative ways by the media, but for the most part these are the spiritualities that people turn to first in their exploration of African traditional religions (ATR). And what is known of Palo Mayombe by the general public is not a large amount of information by any chance. A Google search locates some articles which picture Palo as the “dark side” of Santeria, which is far from the truth. However, to understand Palo as a distinct spiritual system outside of other African diasporic religion, one must understand its BaKongo cosmological foundations.

History of ancient Kongo cosmology

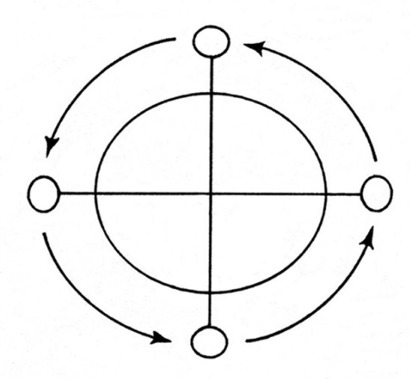

Figure 1: Kongo cosmogram (dikenga)

Fortunately, there is a symbol that captures the essence of Kongo cosmology. The Kongo cosmogram is a cosmological symbol that represents the very patterning of the life process. This symbol is a pre-colonial representation of the cosmogram, as it was conceptualized before European colonization in 1482[1]. It is called the dikenga in the KiKongo language, literally meaning “the turning;” it stands for the cycling of the sun around four cardinal points: dawn, noon, sunset, and midnight when the sun is shining in the world of the dead. Composed of a cross, a circle, and usually arrows, this symbol was found in Kongo material culture well before the contact of colonial Christianity and its cross motif. Anthropologist Robert Farris Thompson, a scholar of Kongo art and religion, says that the “dikenga represents the ultimate graphic design, containing key concepts of Bakongo religious belief, oral history, cosmogony, and philosophy, and depicting in miniature the Bakongo conceptual world and universe” (Thompson 110). The key principle of the dikenga is that nothing ever survives “intact” because nothing ever survives in a fixed form. It is this spiral that is the basic element of Kongo spirituality.

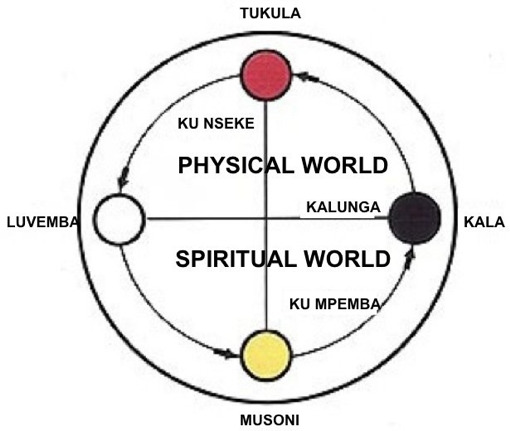

Figure 2: Dikenga

In his seminal piece on Kongo cosmology entitled African Cosmology of the Bantu-Kongo: Principles of Life & Living, Dr. Fu-Kiau explains the motion of the dikenga as the process of ancestralization, of dying and being reborn as an ancestor, through the heating and cooling of existence. This explanation of death and ancestralization is at the core of Palo Mayombe.

Origins of Palo Mayombe

Palo Mayombe is a Kongo derived religion from the Bakongo Diaspora. This religion was transported to the Caribbean during the Spanish slave trade and sprouted in Cuba mostly and in some places in Puerto Rico in the 1500. As the enslaved were forced out of their homelands, their beliefs went with them. Spanish colonialists in Cuba initiated a strategy in the sixteenth century to create mutual aid societies, called cabildos or cofradías, which served to cluster Afro-Cubans into different ethnic categories. This was a strategy of “divide and rule” designed to foster social differences across groups within the enslaved population so that they would not find a unifying focus through which to rebel against the colonial government. In contrast to the extensive blending of diverse African cultures that would be seen in Haiti and Brazil, Cuban cabildos contributed to rich continuations of Yoruba culture in the development of Santería and to largely separate developments of BaKongo beliefs in Palo Mayombe (Fennel). Elements of Catholic beliefs were incorporated into both Santería and Palo Mayombe due to the imposition of the Spanish colonial regime and the cabildo system.

Figure 3 Palo Mayombe Ceremony

Palo Mayombe is very nature-based. Although most African Diasporic religions base rituals and practices in nature, palo (meaning “stick” or “segment of wood” in Spanish) solely depends on the material elements of nature to access the spiritual realm. In Cuba, the Kongo ancestor spirits are considered fierce, rebellious, and independent; they are on the “hot” scale of natural forces. Just as the importance of ancestralization mentioned above, the ancestors are present and inclusive in the practitioner’s life. Nzambi Mpungo is the greatest force in which paleros or paleras (Palo practitioners) call God. Nzambi Mpungo is literally the first ancestor, the initial iteration which all human life flows. Nzambi was viewed as having created the universe, people, spirits, transformative death, and the power of minkisi (ritualized, material objects). The Godhead was thus viewed as being removed from mortal concerns, and supplications were made instead to the ancestor spirits or the intermediary spirits created by Nzambi. Below Nzambi are the mpungus (elemental forces), the ancestors, and the spirits of natural forces (Bettelheim). Each mpungu is similar to an orisha from Yoruba culture due to shared African derived origins, but the two are not the same entity by any means. The mpungu are Afro-Cuban spirits, specific to their diasporic groundings and to the lands of the Diaspora. However, due to their origin

The material tools of Palo Mayombe

Cigars are used to enter into a trance-like state in order to more easily connect with spirits. Special machetes and chains are also used in spirit pots. Candles and rum are essential elements for any Palo ritual. The nganga is used to describe an iron cauldron filled with dirt and specialized sticks; this aids the palero/a in communication with the spirit. In Central America, Cuba and the Caribbean, this cauldron is called a Nganga-Prenda because the culture of modern day and the influence of Latin American's spiritualism in Palo Mayombe.

Figure 4: Prenda de Lucero

The Muertos are important entities in the Palo religion. The house of the dead is where the Palo spirits and the ancestors reside. As illustrated through the Kongo cosmogram above, Palo cosmology does not believe in death, but a continual cycle through various forms. It is the process of ancestralization that makes communication with the spirits of the dead accessible. In the Kongo tradition, ancestors, who have access to invisible forces, have the duty to protect the living. In exchange, the ancestor’s descendants have the obligation to take care of the ancestor’s memory and to venerate their earthly representation. This is why bones are another central tool in Palo. After a person has passed, the bones remain, and the bones carries the essence of a soul long after a person is gone. Bones are thus a sacred item in Palo Mayombe and are usually incorporated in Palo rituals. Usually an ancestor altar is an essential piece in the house of a palero/a, along with offerings of food, drink, and special itemize to venerate their ancestors.

Like many ATR’s and magical system, initiation of some kind is needed in order to practice. Guidance from the elders of the religion is highly encouraged, especially since the ways of the spiritual system is nothing like physical realms.

Palo Mayombe and Other Religious Connections

The influence of Palo Mayombe can be found in Central America, Brazil, and Mexico and in the United States. There are different sects of Palo (Palo Monte, Christian-based Palo, Jewish-based Palo) that come from different lineages and distinct engagements with the cultural environment around the practice. There is another Kongo-derived religion in Brazil is Quimbanda, which is a mixture of traditional Kongo, indigenous in India and Latin American spiritualism. Palo Mayombe is the engagement of Kongo influence in the Caribbean and the wider Diaspora. It has its own priesthood and set of rules and regulations. Rules and regulations will vary according to the Palo Mayombe house to which an individual has been initiated into.

Some people who practice Palo might mix other African-derived systems, like Ifa, Vodou, or Santeria, but Palo is a religion in its own right. For example, Yemoja, the orisha of the ocean and motherhood, may be seen as the same energy as Madre de Agua, the mpungo of the ocean and of motherhood. Although these spirits may have similar functions within the religions, they are two separate entites from particular cultural origins and with specific needs. It is quite common for spiritual seekers to be initiated in multiple religions, so it is of great importance to make sure each path is approached. Although there are other religious elements in Palo, it is all included in the practice and not separated within the religion. When Portuguese missionaries brought the message of Christianity to the Kongo/Bantu, the natives embraced it…while continuing their own native practices (Jason R. Young, Rituals of Resistance). So, this pattern of centripetal inclusion is also present in Palo Mayombe. As Iya TeeDee Oshún, a priestess of African diasporic religions, commented in a recent Facebook post:

“Palo is a beautiful road for those of us that it is for. It's also not just some shit you get done real quick before you ‘elevate’ because that's what Iya's spirit guide said to her in the shower. (Not making that up at all.) It's definitely not Iya nor Baba's "witchcraft pot" in the closet or behind the washing machine or above the grease stain in the garage. It's rarely what I hear when people talk to me in Yorabalese” (2019).

Iya’s mention of “Yorbalese” speaks to a common trend of people in the Diaspora making all of African-derived religions about orisha Ifa/Nigeria, but Palo is of the BaKongo Diaspora. The only system close in origin and practice to Palo is African American Hoodoo, which uses similar elements of the heating and cooling of herbs in spiritual work.

Conclusion

When one decides to take a step into the spirituality of Palo Mayombe, the journey really is a deep engagement with their ancestors and with the raw elemental forces of nature. It is a spiritual awareness that provides protection for the community and the self. The ancestors are the root of one’s existence; the root is the culminating point from which all life springs. This Afrocentric view of cosmology in which Palo Mayombe is grounded, deals with the consciousnesses of nature and of ancestry. Anyone who claims Palo Mayombe as a “dark” or unorthodox religion does not understand the Kongo origins of which Palo operates.

[1] The Kongo cosmogram is a pre-Christian symbol, but due to the iconography of the Christian cross, many people overlap their meanings

#Palo Mayombe Kongo-derived Afro-Cuban Spirituality#Palo#ATR#Congo#African Cosmology#Ancestry#African Religions#IFA#Palo Monte#Kongo

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

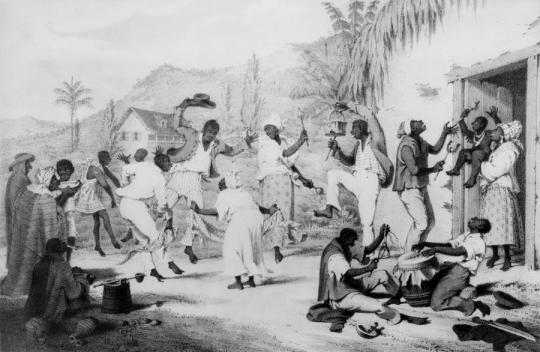

Long before it arose in New York City and became an influential style of music around the world, salsa music has its seeds in African rhythms and traditions that came to the Caribbean through the slave trade. Centuries of enslavement caused many cultural changes in Cuba, including the music that led to salsa.

Some people know Bobby Day’s 1958 “Rockin’ Robin” or Michael Jackson’s remake but the origin of the song goes back to the days of slavery.

The majority of the Africans that were enslaved and brought to the Americas were of West African descent where the drum was used as a form of communication. In the Americas, enslaved Africans used the drum in the same way — communicating with the enslaved on distant plantations and ultimately planning uprising.

The enslavers caught wind of this and enacted a ban.

It is absolutely necessary to the safety of this Province, that all due care be taken to restrain Negroes from using or keeping of drums, which may call together or give sign or notice to one another of their wicked designs and purposes. — Slave Code of South Carolina, Article 36

That ban went down in 1740 and soon spread throughout Colonial America.

But the beat is in the heart of the African.

We soon found other ways to imitate the sound of the drum; stomping, playing spoons, washboards, or anything other household item. We also “slapped Juba” or played “hambone” where the body became an instrument where the player slaps their thighs and chest for the drum beat. (How did young boys in 1980s Park Hill, Denver know “Hambone?”)

Although we kept the beat, we lost the tradition, a cultural marker snatched away from us.

While the American enslaver worked feverishly to destroy any vestige of African culture, the Spanish enslaver of Cuba felt that it was in his best interest to allow the enslaved African to maintain his culture. In support of that, the Spanish allowed the Africans to organize Cabildos (or social groups) based on their nation of origin. Thus you had the Abakua (or Ekpe) from the nations known as Nigeria and Cameroon, the Madinga (or Malinke) from Sierre Leone, etc.

Our focus is primarily on the Lucumi, the Cabildo founded for the Yoruba of Benin and Nigeria. This lineage would be the cornerstone and origin point for what is now called “Salsa.” And what is this “Salsa?”

When we spoke of the drum being forbidden among the enslaved Africans in America, we forgot to mention that there was one place that didn’t enact that ban. That place was the port city of New Orleans, Louisiana — some even call New Orleans the Northernmost Caribbean city.

Similar in the way that the Spanish allowed for Cabildos in Cuba, the Louisiana enslavers permitted Sundays off and were okay with the dance and celebration so long as the enslaved African did so outside of the city limits in a place called Place des Negres (eventually known as Congo Square).

After the Civil War, Africans in America were able to get a hold of surplus brass instruments and shortly thereafter began composing music based on the popular music in the Caribbean at the time, the Cuban Habanero. Many say that this is one of the foundations of jazz music itself and the basis of the habanero, the tressilo, can be heard in second lines. Self-proclaimed jazz inventor, Jelly Roll Morton had this to say:

Now take the habanero “La Paloma”, which I transformed in New Orleans style. You leave the left hand just the same. The difference comes in the right hand — in the syncopation, which gives it an entirely different color that really changes the color from red to blue. Now in one of my earliest tunes, “New Orleans Blues”, you can notice the Spanish tinge. In fact, if you can’t manage to put tinges of Spanish in your tunes, you will never be able to get the right seasoning, I call it, for jazz. Jelly Roll Morton

Because of those qualities, a young musical prodigy from Cuba, Mario Bauzá recognized the similarities between jazz and Cuban music straightaway. Bauzá fell in love with jazz having heard it on Cuban radio but it was his trip to Harlem, NYC in 1927 that convinced him that New York was where he wanted to be and jazz was the music that he wanted to play.

Bauzá returned to New York in 1930, immediately found work, eventually landing a gig in the Cab Calloway band. Here he brought on the legend in the making, Dizzy Gillespie, and the two became fast friends. Bauzá attempted to play his “native” music to many in the band but they dismissed it as “country” music. Gillespie, on the other hand, embraced it.

For the next eight years Bauzá played in predominately African jazz bands having seen discrimination from white Cubans. Yet he longed to start a group that incorporated the music from his home and his second love, jazz. He shot this idea to his childhood friend/brother-in-law and in 1939 at the Park Palace Ballroom the Machito Afro-Cubans would debut.

“I am Black, which means my roots are in Africa. Why should I be ashamed of that?” Bauzá said in reference to the name.

Bauzá replaced the drum kit, which at that time had only been around for 20 years, with the hard to find congas, timbales, and toms. “The timbales play the bell pattern, the congas play the supportive drum part, and the bongos improvise, simulating a lead drum”. In the 40s these drums could only be found at Simon Jou’s bakery, La Moderna, locally known in East Harlem simply as Simon’s.

Next, the Afro-Cubans needed a home and they would find that not in Harlem nor the Bronx, but instead in Midtown Manhattan, a club called the Palladium.

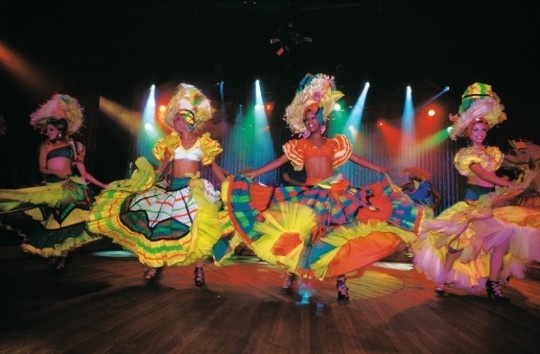

Salsa is a set of Afro-Caribbean rhythms fused with jazz and other styles. The truth is that its origins have always been much debated, although as a general rule it is mentioned that it comes from a fusion that came from Africa in the Caribbean when they heard European music and wanted to mix it with their drums

These origins focus especially on mambo, danzó, cha cha chá, guaracha and son montuno, later enriched with instruments such as saxophone, trumpet or trombone.

It was the Cuban exiles and those from Puerto Rico who popularized salsa in New York back in the 1950s. But it wasn't until the last third of this century that salsa dancing began to take off all over the world.

Cuba played a leading role in the origin of salsa. Already in the 1930s, melodies and rhythms from Africa were playing on the Caribbean island. Among them was the danzón, a musical piece acquired by the French who had fled Haiti.

History tells us that it was these first rhythms that were then mixed with rumbas such as guagancó and sonero to begin to create their own Afro-Cuban rhythms, including Afro-Cuban jazz, mambo, guaracha, Cuban son and montuno.

The exquisite melody of these new rhythms soon set in other Latin American countries. Puerto Rico and Colombia were the first to welcome these new sounds from the Cuban country.

However, it was not until their appearance in the United States, and more specifically in the Bronx neighborhood of New York, when these rhythms acquired a greater impact. It was the moment in which new musical instruments were added that today form an indissoluble part of salsa.

The great Cuban musicians who moved to New York along with the wave of these new rhythms created the famous tumbadoras, congas or son montuno, and were responsible for introducing trombones and guaracha.

The Origin of the Salsa Dance Steps

Once salsa was defined as a musical genre in the 1970s, the movements and steps of its dance were collected through a fusion of the African with the European.

These steps and movements of salsa fundamentally reflect the influence of the dances that the Africans brought to the Caribbean and the European dances that have been danced in Cuba since the 1930s.

So much so that the basic steps of salsa are precisely the same steps as the Cuban son, just as it also includes steps that can be seen in rumba, danzón and mambo.

The origin of these variants is in the regions where this style comes from, which are the ones that developed each dance, always under the same umbrella of the term salsa.

It is not surprising, then, that salsa is defined as the result of a series of social conditions and the evolution of a series of rhythms and melodies from Cuba, which were developed and achieved repercussion in the United States.

There are those who assure against this mixture that salsa is neither a rhythm nor a style, but rather a term that serves to represent all the music of Afro-Cuban origin that emerged in the first decades of the twentieth century.

In short, the origin of salsa has always been, and will continue to be, much discussed. American musician Tito Puente was right when he said, "Salsa doesn't exist. What they now call salsa is what I have played for many years, and this is mambo, guaracha, cha cha chá and guagancó".

#salsa#cuba#congo#nigeria#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#brownskin#africans#afrakans#brown skin#african culture#afrakan spirituality#nigerian#nigerians#ghana#niger#cameroon#senegal#west africa#afro cuban#american#african american#african american history#american history#dance#african dance#congo dance#ekik#yoruba

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Synth Punk#Central African Music#Post-Punk#Afro House#Dance-Punk#2010s#Democratic Republic of Congo#body horror tw

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

#free congo#free palestine#free gaza#free sudan#free haiti#boycott disney#african art#afrocentric#black artists on tumblr#blerdshit#drums of liberation#eyes on rafah#one piece#all eyes on rafah#anime art#humanitarian aid#allah#afro#save sudan#boycott divest sanction#save congo#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#free sudan free palestine#freepalastine🇵🇸#smiling friends pim#freedom#smiling friends charlie#oc free palestin#boycott marvel

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#11: Sabú - Palo Congo (1957)

Genre(s): Afro-Cuban, Rumba, Jazz

This is the first album in 1001 Albums to really blindside me. I've listened to a hell of a lot of Blue Note albums over the years (and bought and sold even more) but I've never seen this thing in my damn life. That being said, I'll admit that Rumba (and Afro-Cuban music at large) is a musical blind spot for me. I've heard enough bits and pieces over the years to recognize the sound, but it's not something I've ever had the chance to go deep on.

Palo Congo, according to my scholarly Google research, is the first album by conguero Sabú Martínez (credited here simply as Sabú), and his first and only release on Blue Note. It features Arsenio Rodríguez on guitar, a name that I recognize but can't quite place, but who is apparently a Real Big Deal in the world of Afro-Cuban music. Like most Blue Note records, and a large chunk of jazz at the time, it was recorded by legendary recording & mastering engineer Rudy Van Gelder (if you've ever seen "RVG" in the dead wax of a record that's your cue that he did the master for your pressing, and it probably sounds damn good as a result).

I was really surprised by this one. This is a great listen. Most of the album is comprised of a dense layer of percussion with call and response vocals, with some stringy bass and scuzzy guitar (and, I believe, some other Cuban string instruments) sneaking in around the edges. The percussion section is covered in a thick layer of cavernous reverb, which is an odd choice for RVG (who usually is of the recording school of presenting the music as-it-is with a realistic live sound), but it creates a fascinating atmosphere in this case. The percussion hits are clean, followed by watercolor reverb trail as the tails of the drums all bleed into each other. On some tracks the vocals are more sung, on some they're closer to shouts. The string instrumentation is sparse, sometimes playing a melodic ostinato, sometimes providing rhythmic stabs, always with a gnarly, lo-fi sound to it when it creeps in. There's something very forward-thinking about the sounds here, particularly on an aesthetic/timbral level. Many moments call decades forward in time to early post-punk groups like Savage Republic and Joy Division. Other times the dense, layered atmosphere creates the feel of an African Head Charge track.

Unfortunately this album seems to be out of print across the board. I'd clock it as a prime candidate for a reissue in Blue Note's Tone Poet series, which primarily focuses on bringing long OOP titles back into print on vinyl with some of the best quality pressings on the market today, with a focus on these sorts of beloved deep cuts. Regardless, it's a shame it's not more readily available today. Luckily it's at least on streaming (for the nerds, I listened in hi-res on Qobuz). I'll definitely have to keep an eye out for a copy of this one.

More to the point, MUST you hear Palo Congo before you die? I'm sure glad I did, that's for sure. This album is absolutely killer. I don't know enough about the history of Afro-Cuban music to judge it on a historical or cultural basis, but I think it makes the cut on aesthetic value alone. It's an incredibly fun listen, and one that is sonically forward-thinking in a way that's truly rare to hear.

Next time, we stay in the Afro-Cuban vein with Cubop artist Machito and his album Kenya!

#1001 albums#1001 albums you must hear before you die#1001albumsrated#album review#now spinning#jazz#Afro-Cuban#rumba#Blue Note#Sabu#Sabu Martinez#Palo Congo

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Makuta performance in an old Kongo cabildo.

Source: Robin D. Moore - Fernando Ortiz on Music: Selected Writing on Afro-Cuban Culture (2018: 101)

18 notes

·

View notes