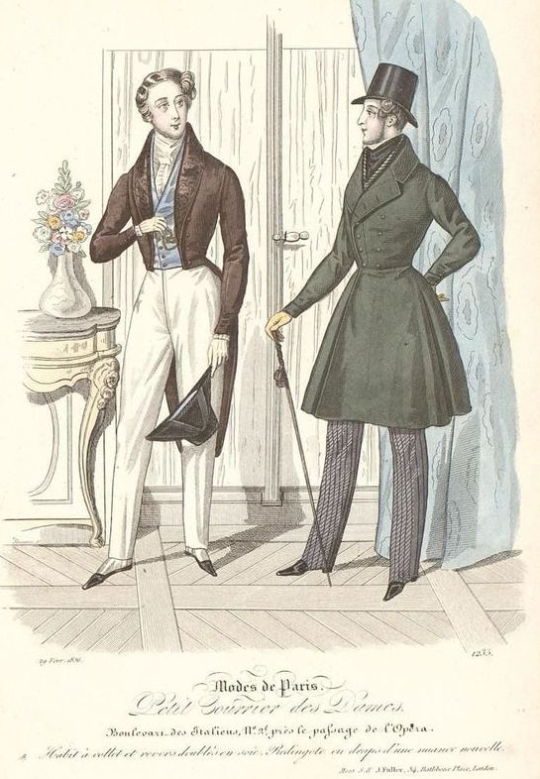

#19th c mens fashion

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

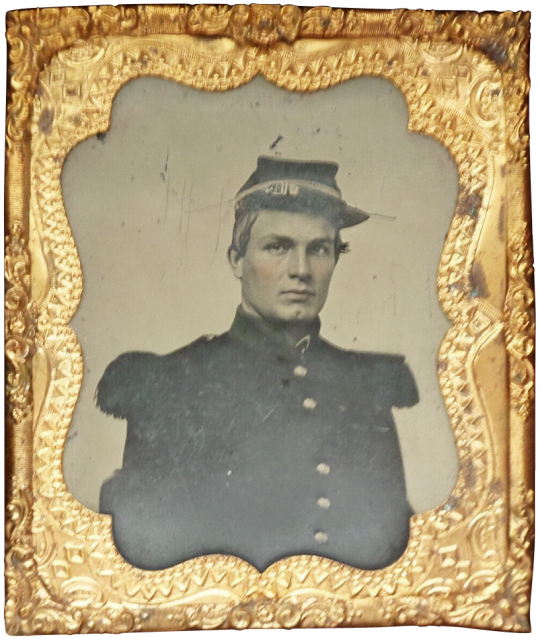

Ambrotype of a Union soldier with a manly chin dimple and a missing button, c. 1860s

#perhaps he gave the button to a sweetheart—I feel like I've once read that in some 19th c. novel or other#then again I love the idea of him having primped and pomaded for picture day only to lose a button at the last minute#19th century#1800s#1860s#American Civil War#19th century fashion#historical fashion#men's fashion#uniforms#military fashion#military history#19th century photography#ambrotype#19th century men#vintage men

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

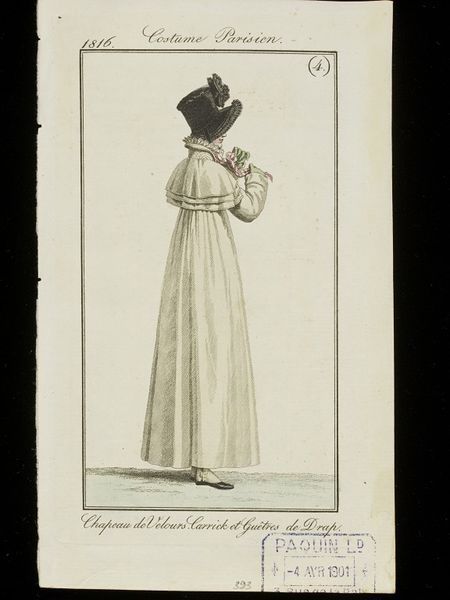

The Carrick Coat

James Tissot (French, 1836-1902) • On the Ferry Waiting • c.1878 • Private collection

A Carrick or Garrick (in Great Britain) is an overcoat with three to five cape collars, worn by both men and women primarily for travel and riding, in the 19th century.

Artist unknown. Costume Parisien. Chapeau de Velours. Carrick et Guêtres de Drap., 1816. Hand-coloured engraving. London: Victoria and Albert Museum

Sources:

Fashion History Timeline

Metropolitan Museum of Art

#art#painting#james tissot#french artist#art history#fashion history#art & fashion#the resplendent outfit blog#carrick coat#19th century fashion trends#19th century art#oil painting#fine art#victorian fashion#victorian era#19th century fashion

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey bb, I am in need of costume help! I am searching for some long bloomers for a photoshoot. I'm gonna make my guy friend wear armor, bloomers and put on lipstick. It's gonna be great, I just don't know what the correct name of long bloomers would be? Or where to find them for men. He's a long boy (for context).

Hi! Sounds like a fun shoot! Undergarment terms are confusing but you’ve a few options to look up! (Note: I’m not sure if you’re looking for something medieval as per the armour or something around the time of bloomers so I’ll just yap and hopefully something helps)

“Bloomers” is a specifically Victorian-era coined word and garment but probably refers to the thing you have in mind, and probably the only thing Etsy or google will recognise to show you results. It’s complicated, but bloomers weren’t necessarily ladies “underpants” in the way we’d understand them. They were initially more akin to long, ballooned trousers and gathered at the ankle, meant to be visible below a dress or otherwise. As time went on, it started to refer to any ballooned trouser-like women’s garment that ended somewhere between the knee and ankle. Because of this, some drawers (rightmost photo) were referred to as bloomers no matter if plain or frilly/embroidered simply because they were puffy even if they weren’t worn exposed. The important difference is that Bloomers in the trouser sense were a fashion response in the fight for women’s rights, the term Bloomer came from their eventual association with the Victorian social advocate Amelia Bloomer.

They were different from pantaloons. Pantaloons were an early 19th c. men’s item, longer, and figure hugging ending at about the ankle and they replaced 18th c. breeches which fastened just below the knee (Left pic: breeches, right pic: pantaloons). Funnily enough, when searching images of “pantaloons” you’ll get a variety of women’s Victorian and Edwardian drawers, but pantaloons are the men’s garment, I’m not sure why it’s also used to refer to women’s underpants now.

Pantalettes were a type of women’s undergarment meant to be slightly seen and are generally slimmer and less balloony than bloomers (which didn’t technically exist yet) and were lightly frilled/embroidered and usually reached about the mid calf or ankle. Though their origins are quite old, they were most prevalent in the early-mid 19th century, stayed a bit longer for children’s fashion, then kinda fell out of fashion, not that any trouser-like underpants were popular and widely accepted with western women’s fashion to begin with. (Pantalettes below)

Then you have the word “drawers” which sort of refers to any period underpants in general. For women, drawers used to be just a fairly plain linen or cotton pair of short trousers starting somewhere in the 14th-15th c. but were also not widely adopted outside of specific regions, modesty occasions, or sport until the late 19th century, until they eventually became a staple for Edwardian women’s undergarments and became quite frilly in French designs. The term now loosely encompasses any women’s long underpants, so both bloomers and pantalettes and a variety of other underpants are all “drawers”. A lot of women’s drawers were also split-crotch, you didn’t tend to see them completely sewn closed as it made it easier to use the toilet.

I know I’ve referenced mainly women’s clothes here but there are some men’s clothing that has a slightly similar look to Victorian drawers. A basic pair of linen or cotton open leg drawers would suffice, you might look at 18th c. Western European underpants that looked very similar to drawstring linen breeches. If you want something more medieval to compliment the armour, I might also suggest Braies which were essentially just lower waisted breeches (Braies below)

Point is, because of the overlap and appearance, you’ll see bloomers that are technically pantalettes, pantalettes labelled as pantaloons, drawers that are bloomers, it’s all a bit confusing, but I hope that narrows down what you might be looking for.

As for where to find any of these for someone very tall, your best bet might be to get your hands on a pattern for Victorian drawers (I’ve seen some off Etsy or EBay) and see if it’s possible to attach the split legs if it has them and allow for some extra length in the legs for height as they may end more at the knees on a tall person rather than the mid calves. Or have a look about medieval reproduction sites for the Braies style. The good news is that because drawers are basically just plain pants made from white fabric, they’re quite a simple thing to cobble together and have it still be clear it’s old drawers.

Best of luck to your photoshoot!

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

BRIEF NOTES ON DRACULA BALLET COSTUMES

At the beginning we see Mina dancing with Dracula in a sort of dream sequence; she's wearing an 18th-century gown with a pannier and an inverted conical flat-chested silhouette suggestive of boned stays; the fabric is, if not identical to, at least reminiscent in pattern and material to the pseudo-Boyar cloak we see Dracula wearing later. Costumes work a LOT with temporal pastiche in this ballet and it's very very cool--this touch reminded me of Queen Charlotte's court, how she kept court fashions tethered to the 18th-century styles of her youth well into the Regency era.

Speaking of temporal pastiche--extends to dance and costumes simultaneously. There's a ball before we meet the vampires, everyone is waltzing, the costumes are early/mid-19th c. "period drama," the dance is ballet and ballroom. Jonathan departs to Dracula's castle, and Dracula's retinue are dressed like a 70s glam vampsploitation interpretation of the 1830s--glitter, leather pants, ruffled poet/pirate shirts, the works. Clash of "period-accurate" Jonathan and genre fiction vampires. BUT!!!!!!! As Jonathan is seduced by his surroundings, a BLACK NECKTIE is added haphazardly over his cravat--these didn't become part of men's formalwear until after WWI. It's the only black detail on his costume--black signifies vampirism--and it's a motif of encroaching modernity as threat. MOREOVER, the dance with Jonathan, Dracula, and the brides incorporates elements of contemporary/modern dance for the first time.

THE BRIDES. Their costumes are very Swan Lake/Leda and the Swan, which is [chef's kiss] intertext-wise, and they shift back and forth from black to white depending on the scene. There are also three bridegrooms of Dracula. Bisexual representation

MORE LATER

Oh also when Mina is turned into a vampire and Jonathan finds her they have this dance sequence that is like an inverted mirror of their engagement dance at the ball and vampire!Mina brings movements from modern/contemporary dance into their "duet." They also dance beside each other, doing mirror-motions, rather than dancing together as partners or doing any reciprocal choreography. They've both been transformed by their encounters with Dracula in the way they inhabit their bodies and relate to one another

Dracula has a black wig when he dances with Mina and a blond wig when he dances with Lucy. He appears differently to each of them!!!!!!!!!!!

Not a costume note but this ballet REALLY leans into the homoeroticism between Lucy and Mina. They're figured as doppelgangers almost. Lucy's death scene was blocked in a way that made me wonder if this director watched puppet theater Dracula Lucy's Dream, because it was nearly "verbatim," except vampire!Mina stood in for Lucy's other self lurking in the shadows, then acting out a tug-of-war between Lucy's body and the vampire

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

thai language question! what do tongthap and atom call each other in MLMU TH? it sounds like ‘nai’ or maybe ‘ngai’? it’s translated to both of their names several times on the YT subs. i’ve tried to look it up but i’m not sure i’m hearing it right 🙈

Thai pronoun: Nai

They are indeed using nai. Hold on I know I posted about that one at some point... AH HA here it is:

you want this section: (but I'll c&p it over here add to it at the bottom)

Nai & the Mafia

So in 2022 Thai BLs seriously started moving setting outside of the school systems and thus added new pronouns (for us watchers) into the mix. KinnPorsche, Even Sun, and Unforgotten Night all use the pronoun nai (นาย) for you between men. Like many honorifics & pronouns, it’s derived from a minor title of nobility. In the 19th century it was declared the official courtesy title for adult males - regarded as a direct translation of “Mr”.

It has several different uses today.

As a title, it only appears before the real given name (not surname), in official/formal contexts, e.g. when writing down one’s name on an exam paper, job application, or government form. If used with a nickname, it implies a bit of irony (like a teacher calling out a misbehaving student).

As a pronoun, it’s usually an informal second-person pronoun used with males of equal status. It’s a decidedly non-rude word, so it’ll be used among friends/classmates if they don’t feel close enough to use gu/mueng (or if a person just doesn’t use rude pronouns, like swear words there are people who don’t feel comfortable ever saying guu/mueng).

Rao/nai as pronouns used to be the default mode of address on TV before gu/mueng became acceptable to broadcast in the 2010s.

When used by females, nai is pretty much equivalent to males using ter with females - so an old fashioned but intimate and sweet, loving.

On TV, the use of ter/nai is probably most often associated with straight dramas in the acquaintance phase of courting.

Nai also has the meaning “boss” (similarly to the combined form เจ้านาย (jao nai/chao nai). If it’s being used as a pronoun in a more formal or deferential context (like organized crime), it is used in this sense.

Usage number 2 & 6 are the ones we see in Thai BL. All that said I understand as a tourist in Thailand, you will hear nai but not all that often. It’s fine to use khun instead/back, but good to know to identify nai.

Nai & My Love Mix Up

So My Love Mix Up is using #2.

With adult males, nai is actually often paired with chan. (I know, right, but it's what they use. See any of the mafia shows.)

But in this high school setting, Atom & Kongthap seem to be using pom or sometimes even tan. (I haven't touched on tan at all because I find it the most confusing pronoun.)

Atom & Half use guu/mueng. Atom use rao/name with Mudmee, and she does they same with him. Although I think she shifts to chan with Half when they get closer.

Kongthap doesn't seem to ever use informal. Even Half uses nai with him.

So I think the use of polite nai in this relationship is being dictated by Kongthap's character's reserved gentlemanly stiffness (much as in the original show). In other words, were it not for Kongthap's personality, this show in this setting (and with this pair) would be using guu/mueng. But because of the original IP and the extreme reserve of Ida in Kieta Hatsukoi (who also uses quite formal Japanese) we are seeing a linguistic characterization of one half of a couple carry through to the tenor of the whole relationship.

In other words, the use of nai was dictated by Kongthap's personality.

Frankly put, Kongthap would simply not use guu/mueng so they had to find some other way for these two to communicate. Rao/ter is too sweet and cute and old fashioned out the gate (these boys could graduate to it, I suppose, like in college or after).

Now they might have used khun instead of nai. If this were set in uni or the office that would have worked fine. Or even if this were a high school in Bangkok. But I'm not surprised they reached for nai.

In fact, since the announcement of the adaptation I was curious about how they were going to approach Kongthap's pronouns. I thought they might make Kongthap older to solve the issue with phi but they wanted to do the "going away to college together?" part of the plot, so yeah... nai is the solution.

This couple sounds a bit stiff and distanced from each other when speaking together as a result, but I understand why the script chose it.

Hope that explains.

(source)

#my love mix up#thai linguistics#thai pronouns#formal pronouns#thai honorifics#honorigics#Kieta Hatsukoi#my love mix up th#my love mix up thailand#my love mix up thai#thai bl#couple language#nai pronoun

88 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello! i’m looking into adopted yet another 19th century man. i’ve owned several others, and am looking for something unique. are there any unique and peculiar breeds you recommend?

Sure! These heritage and unique 19th century men may not be for everyone, but I want them to get more love.

French soldier left behind on the field of battle during the 1870 Franco-Prussian War.

Poor sweetheart!! True story: the model for this 1872 painting, real French soldier Théodore Larran, met the artist Émile Betsellère many times because Betsellère was so touched by his story. Absolutely the type of 19th century man you want to rescue and love.

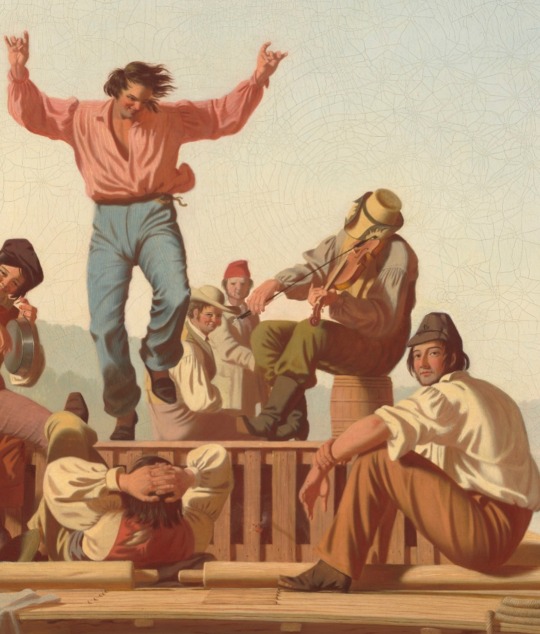

A jolly flatboatman.

From The Jolly Flatboatmen by artist George Caleb Bingham, 1846.

A good 19th century man doesn't have to be wealthy or formal, as these charming working class fellows attest. Perfect for the aficionado of lively, active 19th century men.

British Army 41st Regiment of Foot Soldier, c. 1800-1815.

Who doesn't have "a passion for a scarlet coat," as Jonathan Swift phrased it! Your soldier needs a lot of exercise and structure, but he's not picky about his food or bedding. Comes with his own blanket and water bottle! He's a lover, he's a fighter, I recommend delousing him before you bring him into your home.

Cossack Trowsers King.

Strutting his stuff in 1827, he has an insouciant attitude and a bold, fashion-forward look. You may want to address the fact that he's also a major source of air pollution.

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

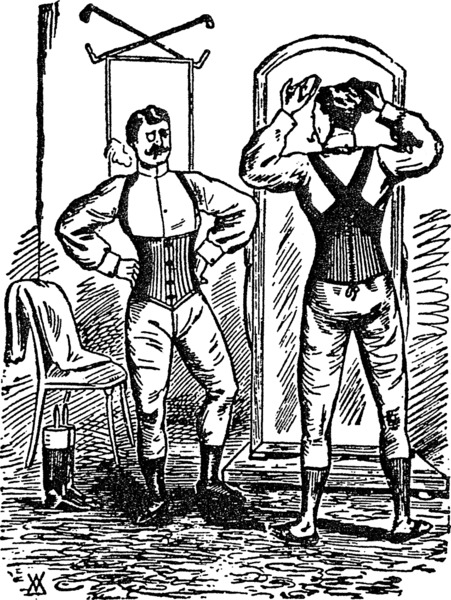

so many words about historical men's corsetry

(This got way too long to send via Discord -- Dangimace in the Renegade Bindery server asked about men's corset sewing/resource recs so here is my half-assed and non-exhaustive rundown. Most of my historical sewing is focused on fashions of the UK, US, and Europe for the second half of the 18th century and first half of the 19th century, so that bias is reflected here; also disclaimer overall that "menswear"/"womenswear" are socially constructed categories and real people's bodies have always looked a wider variety of ways than fashion and other social forces would dictate. I sew historical garments with enthusiastic disregard for the historical gender binary and I'm barrel-chested, thick-waisted, and narrow-hipped no matter what I'm wearing.)

Onward, lads!

Ok wrt men's corsetry: there's a whole lot of fogginess around how historical men's corsets were constructed for a bunch of annoying reasons but that means there's lots of possibilities to explore in pattern drafting and project planning. Stays and other stiffened body-shaping garments have a whole complex conceptual relationship to the body basically as soon as they start appearing. 16th and 17th century garments do a whole lot of shaping (both compressing and building up) for men and women alike, but things really kick off in the 18th century in terms of the symbolic weight placed on stays and (later) corsets. Whole lot of stuff about gender, social class, race, fatness, morality, etc. getting projected onto these garments. So I'm a little leery about people taking obviously satirical illustrations of fashion-victim dandies or Gross Corpulent Libertines getting laced into corsets as truthful and indicative of the way men were really dressing -- scurrilous gossip and exaggeration are both a pain to sift through if we want to know which men wore corsets, what kind, and why.

In the very late 18th/early 19th century corsets were part of the repertoire for achieving highly fashionable shapes in menswear. (Along with a whole lot of padding.) They weren't mandatory for all dudes, but for fashion-forward dandies and equally fashion-forward military men, male corsets/stays were definitely a thing. The whole Romantic-era pigeon-breasted, narrow-waisted silhouette can be emulated by shapewear worn beneath the clothes, pads in the garments themselves, or both; in addition to waist reduction it helped to maintain smooth visual lines underneath close-fitting garments.

(look at these minxy 1830s dudes and their tiny waists)

As the century goes on the desired menswear silhouette becomes boxier and less fitted, and male corsetry recedes into the background; we start to see patents and advertisements for men's corsetry, so they still seem to have been worn, but there's a lot more language around vigorous manly athleticism and supporting the structures of the body. It can be hard to tell whether a particular piece is intended to be worn primarily for some medical purpose or for its perceived aesthetic benefits. This is giving me such flashbacks to trying to find post-surgical compression garments.

(Side note: there's also a vigorous tradition of fetishist writing about corsetry all through the 19th century, in fairly mainstream channels, which is fascinating. Due to the relatively private and deeply horny nature of fetish tightlacing we don't necessarily know as much about what those same letter-writers may have "really" worn at home, but I hope they were having fun.)

I've seen very few specifically men's corsetry patterns from historical pattern-makers-- not even really big names like Redthreaded. I sewed my 19thc menswear corsets from the men's underbust pattern in Laughing Moon Mercantile #113 which afaik is speculative rather than reproducing a specific historical garment, but it's not too different from the women's late-19th-century underbust patterns in the same pattern pack.

(image credit: LMM)

However, a lot of underbust and waist-cincher patterns from more general historical patternmakers could be made suitable with some minor alterations. Here I'd also rec books like Jill Salen's Corsets: Historical Patterns And Techniques and Norah Waugh's Corsets & Crinolines, though their focus is definitely on womenswear and you need to be relatively comfortable scaling up or drafting from pattern diagrams.

The structural features and desired results for a man's corset are pretty much the same as any other corset (back support, compression in some areas, etc.) even when the desired silhouette is different; commercially-created patterns are drafted with the expectation of certain bodily proportions so like with all corset-sewing it's important to make a mockup for fitting purposes. (I ended up liking one of my mockups so much I finished the process and made it a whole separate corset.) I don't know much about this area but I seem to see a lot more belt-and-buckle closures and criss-crossing straps in corsets designated as being for men -- this might be a byproduct of gendered differences in how people got dressed, but it might be nothing.

There's some weird and wonderful historical examples, both extant and in images -- I appreciated this post at Matsuzake Sewing, "A Brief Discussion Of Men's Stays", and its accompanying roundup of images on Pinterest though the tone wrt historical fetishwear corsets in the blog post is a little snippy. I really want to make a replica of Thomas Chew's 1810s corset (which you can read more about here at the USS Constitution Museum) but it incorporates stretch panels made with a shitload of metal springs and I'm not ready for all the trial and error trying to replicate that.

(image credit: USS Constitution Museum Collections)

There's a pretty rich vein of modern men's corset patterns which seem like they could be easily pattern-hacked for historical costuming purposes, like these with shoulder straps from Corsets By Caroline or DrobeStoreUpcycling's waist cincher which also looks like it could be altered pretty easily to cinch with straps and buckles like some 19thc men's corsetry does. This pattern for a boned chest binder in vest form by KennaSewLastCentury is also really cool but I didn't get a chance to sew it pre-top-surgery. (I think I've also seen someone who made a chest-compressing variation on Regency short stays, but I can't find it now.)

In general a lot of underbust and waist-cincher patterns should work just fine for silhouette-shaping without much bust/hip emphasis -- my usual resource for free corset patterns (Aranea Black) recently took down all her free patterns but they're definitely still circulating out there. For general fashion purposes the sky is the limit and there are a lot of enthusiastic dudes in corsets out there. This Lucy Corsetry round-up shows a variety of modern corsetiers' styles designated as being for men or more masculine silhouettes (including a SUPER aspirational brocaded corset with matching waistcoat made by Heavenly Corsets that I'd love to sew a historical spin on) and you can see some commonalities and possibilities for body-shaping.

I can also give some more general corset-sewing resources but I'm very much in the learning process here and I'd love any recs or input from people more experienced in pattern-drafting and corset-sewing.

124 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m obsessed with John Leech’s illustrations of swells and other ridiculous fashionable men. Do you have any sources of images or further information you can point me to?

Do I ever!

I love to recommend the collection of John Leech's cartoons that I have used heavily for @is-the-19thcentury-man-okay: John Leech's Pictures of Life and Character, Volume 1 on Google Books. At this time it looks like the John Leech Archive web site is down. That's really a shame because it was searchable by year and (limited) keywords/subjects. It's still on the Internet Wayback Machine although I'm not sure how much is preserved.

The Victorian writer and entertainer Albert Smith (sadly forgotten today) is another great source for 1840s and 1850s fashions and foibles. I highly recommend The Natural History of the Gent and The Natural History of the Idler Upon Town.

For fashion history references to go with the cartoons, you can't go wrong with A History of Men's Fashion by Farid Chenoune, and the classic Handbook of English Costume in the 19th Century by Phillis Cunnington and C. Willett Cunnington.

Thanks for the question, this subject is dear to my heart.

#asks#fashion history#john leech#albert smith#gents#swells#1840s#1850s#historical men's fashion#caricatures#cartoons#early victorian era#resources#btw the illustration is by john leech for 'mr sponge's sporting tour' by r.s. surtees

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of Bánhida by Feszty Árpád 19th-20th C. CE

"Whatever may have happened in 901, Hungarians definitely returned to Italy in 904 as allies and auxiliaries of Berengar. Earlier in this year, Louis of Provence had entered Lombardy once again, had taken Pavia, and was in the process of occupying Verona when swarms of Hungarians attacked the territory under his control. As those forces wasted the upper Po, Berengar retook Verona and captured his rival, whom he blinded. The hapless Louis was then allowed to return with his men to Provence. Even in this miserable state, we are told, his forces were harassed by Magyars until he disappeared on the other side of the Alps never to return to the peninsula again. As for Louis's supporters in Lombard cities, many of which were unfortified and, therefore, extremely vulnerable to steppe nomads, Berengar allowed his Hungarian allies to loot them without mercy.

According to Magyar traditions, it was in 904 or 905 when Arpad, who was now emerging as the sole leader of the Hungarian confederation, arranged for his son Zolta to marry a Moravian princess. If this was indeed the case, then it was at this time that the 'old' Moravian regnum, the megale Moravia of Constantine Porphyrogenitus, came under Hungarian rule. For some time there had been certain elements among the Moravians who wanted to throw their lot with the Magyars rather than with the Bavarians. Evidence of this is found in a letter that Theotmar of Salzburg (Dietmar I, also Theotmar I, was archbishop of Salzburg from 874 to 907. He died fighting against the Hungarians at Brezalauspurc on July 4, 907.) and the other Bavarian bishops sent to Rome around 900. This epistle complains that Moravians were relapsing into heathen practices, shaving their heads in the Hungarian fashion, and conspiring with the Pagans, 'so that in all of Pannonia, our largest province, almost no church is to be seen.'"

-Charles R. Bowlus. Franks, Moravians, and Magyars: The struggle for the Middle Danube

...

I couldn't find more details about what this "Hungarian fashion" haircut was since I couldn't find a full account of Theotmar's letter. However, Mark of Kalt in the 14th century gives more possible details in his description of the Vata Pagan Uprising:

"...Vata was the name of who first offered himself to the devil, shaved off his head, and left three pigtails according to the Pagan custom..."

— Márk Kálti: Illuminated Chronicle

#hungarian art#hungarian history#european art#history#european history#medieval history#fine art#paintings#pagan#paganism#finno ugric#magyar#middle ages

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is it about the Victorian era that interests you the most? Specific decades, and also things like technology, social and intellectual movements, fashion history, etc. What do you wish was more well-known about the Victorians?

This is such a fun question! I've made two passes at this and they both turn out essay length, so apologies in advance for the beast of a post here, haha.

The overarching thing that I'd say fascinates me is that to study the Victorian era is to ingest a heady blend of modernity and antiquity--in so many ways the people of the 19th century were the architects of the modern day, and I'm continually surprised by the tiny ways in which the Victorian era feels so much closer than ~150ish years ago. And yet it's also so distant in so many ways, and particularly early in the period or in rural areas, the rhythms of life are quite alien to us. Madame Bovary is a novel about the wife of a doctor who mounts his horse to make house calls; the pharmacist in it keeps a jar of arsenic on his shelf; yet it's also a book where I thought "I know someone exactly like this" about pretty much every character. That to me is the fascinating thing about history generally, but especially about the 19th century, so far and yet so close.

I think this extends to pretty much everything. The books of the 19th century use mostly familiar words and the same punctuation as today, but across genres and authors there's such a distinct 19th century tone and style and word choice. Technologically the century is full of so many interesting first passes and middle chapters; the steel pen superseded the quill but is generally obsoleted today by the ballpoint, as an archetypal example. The list goes on.

In more specific terms: one thing I love is Victorian print culture. I'm a printing and typography nerd; I love the neat hairline strokes of 19th century body text typefaces, the wild maximalism of the era's display fonts. I love the seven column broadsheets that jam as much news as possible into four pages with zero pictures; I love the magazines and periodicals lavishly illustrated with steel and copper engravings. I love to imagine what they would have felt like to read when they were first printed, try to put myself in the shoes of the people of the past, get in their heads. (As my writing style probably indicates I have read far too many old books and newspapers, and as a result Victorian sentence structure and phraseology has irreversibly seeped into my brain.)

Fashion history is another big interest of mine. My big interest is in men's clothing, particularly around midcentury—the pinched waists and long hair, the puffy shirts and narrow pants. I like 19th century clothing generally, of course, and I like the Regency tailcoats and breeches, and the boxy sack coats of century's end, as much as the next guy; but something about that midcentury style is just my favorite. I don't have too much philosophy or deeper meaning on this one, if I'm being perfectly honest; I mostly just like the look, here. But I think fashion and textiles history is a pretty interesting field and well worth study in its own right. Learning what exactly broadcloth is, for instance, helped me understand much more intimately why one of the underpinnings of the Industrial Revolution was the textiles industry.

There's a lot of artistic and literary movements that I'm interested in; Victorian medievalism is always fascinating, I'm fond of Romanticism, and, well, maybe not quite so much Gothic proper, per se, but the post-Gothic echoes of Victorian literature, The Signalman and In A Glass Darkly and The Picture of Dorian Grey and Dracula, anything by Poe, the 'golden age' of ghost stories c. 1890-1920.

I could list off a great many other things that interest me—I'm fascinated by the early history of socialism (now and then lately I've been reading Karl Marx's correspondence and his old New York Herald articles,) I'm of course always interested in that historian's holy grail of Trying To Better Understand Everyday Life, I like architectural and art history, maritime history is a perennial favorite—but to write down every last thing would be to make this absurdly long post even longer, so I'll have to make this highlights reel suffice.

Things I wish were more well-known... I think this is maybe one of those topics where I know enough that my idea of what the "average person" knows is skewed, so I might have to sit on that one for a while before I can think up something interesting; I encounter a lot of odd and interesting misconceptions at work, but none of them are fresh in my mind. I suppose a classic go-to would be that 19th century clothing (and, honestly, historical clothing more generally) is way more comfortable than it looks.

#long post#history#reread this hours later and realized i went way overboard with the semicolons again. oh well

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A hot comb (also known as a straightening comb or pressing comb) is a metal comb that is used to straighten moderate or coarse hair and create a smoother hair texture. A hot comb is heated and used to straighten the hair from the roots. It can be placed directly on the source of heat or it may be electrically heated.

History

The hot comb was an invention developed in France as a way for women with coarse curly hair to achieve a fine straight look traditionally modeled by historical Egyptian women.

Parisian Francois Marcel Grateau is said to have revolutionized hair styling when he invented and introduced heated irons to curl and wave his customers' hair in France in 1872. His Marcel Wave remained fashionable for many decades. Britain's Science and Society Library credits L. Pelleray of Paris with manufacturing the heated irons in the 1870s. An example of an 1890s version of Pelleray's curling iron is housed at the Chudnow Museum in Milwaukee.

Elroy J. Duncan is believed to have invented and manufactured the first hot comb or heated metal straightening comb in America.[citation needed] Sometimes the device is called a "pressing comb." During the late 19th century, Dr. Scott's Electric Curler was advertised in several publications including the 1886 Bloomingdale's catalog[6] and in the June 1889 issue of Lippincott's Magazine[7] Marketed to men to groom beards and moustaches, the rosewood-handled device also promised women the ability to imitate the "loose and fluffy" hairstyles of actress Lillie Langtry and opera singer Adelina Patti, popular white entertainers of the era.

Mme. Baum's Hair Emporium, a store on Eighth Avenue in New York with a large clientele composed mostly of African American women, advertised Mme. Baum's "entirely new and improved" straightening comb in 1912. In May and June 1914, other Mme. Baum advertisements claimed that she now had a "shampoo dryer and hair straightening comb," said to have been patented on April 1, 1914. U.S. Patent 1,096,666 for a heated "hair drying" comb – but not a hair straightening comb – is credited to Emilia Baum and was granted on May 12, 1914.

In May 1915, the Humania Hair Company of New York marketed a "straightening comb made of solid brass" for 89 cents. That same month, Wolf Brothers of Indianapolis advertised its hair straightening comb and alcohol heater comb for $1.00. The La Creole Company of Louisville claimed to have invented a self-heating comb that required no external flame. In September 1915, J. E. Laing, owner of Laing's Hair Dressing Parlor in Kansas City, Kansas claimed to have invented the "king of all straighteners" with a 3/4 inch wide, 9 1/2 inches long comb that also had a reversible handle to accommodate use with either the left or right hand. Indol Laboratories, owned by Bernia Austin in Harlem, offered a steel magnetic comb for $5.00 in November 1916.

Walter Sammons of Philadelphia filed an application for Patent No. 1,362,823 on April 9, 1920. The patent was granted on December 21, 1920. Poro Company founder Annie Malone has been credited by some sources with receiving the first patent for this tool in that same year but the Official Gazette of the U. S. Patent Office does not list her as a holder of a hot comb patent in 1920.

The Patent Office Gazette of May 16, 1922, however, includes Annie M. Malone of St. Louis in a list of patentees of designs as being granted Patent No. 60,962 for "sealing tape," which Chajuana V. Trawick describes in a December 2011 doctoral dissertation as an ornamental tape used to "secure the closure of the box lid of Poro products" to prevent others from selling products in packages made to look like Poro products.

Hair care entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker never claimed to have invented the hot comb, though often has been inaccurately credited with the invention and with modifying the spacing of the teeth, but there is no evidence or documentation to support that assertion. During the 1910s, Walker obtained her combs from different suppliers, including Louisa B. Cason of Cincinnati, Ohio, who eventually filed patent application 1,413,255 on February 17, 1921 for a comb Cason had developed some years earlier. The patent was granted on April 18, 1922 though Cason had been producing the combs for many years without a patent.

Potential consequences

It is not uncommon to burn and damage hair when using a traditional hot comb. A hot comb is often heated to over 65 degrees Celsius (149 degrees Fahrenheit), therefore if not careful severe burns and scarring can occur.

The hot petrolatum used with the iron was thought to cause a chronic inflammation around the upper segment of the hair follicle leading to degeneration of the external root sheath.

In 1992, a hot comb alopecia study was conducted, and it was discovered that there was a poor correlation between the usage of a hot comb and the onset and progression of disease. The study concludes that the term follicular degeneration syndrome (FDS) is proposed for this clinically and histologically distinct form of scarring alopecia.

Hot comb alopecia and follicular degeneration syndrome are irreversible alopecia of the scalp that was believed to occur in people who straighten their hair with hot combs, but this idea was later debunked.

0 notes

Text

Explore the Evolution of Chemise Lingerie: A Historical Perspective on Its Design and Cultural Significance

The chemise lingerie is one of the most enduring and transformative garments in the history of fashion and lingerie. Its evolution reflects shifts in cultural norms, beauty ideals, and functionality. Below is a historical perspective on its design evolution and cultural significance:

Origins in Antiquity Era: Ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome (c. 3000 BCE – 500 CE) Design: The earliest chemise-like garments were simple, loose-fitting tunics made of linen. They were worn under outer garments to protect them from sweat and body oils. Cultural Role: These undergarments served a utilitarian purpose rather than a decorative one. In many cultures, they symbolized modesty and hygiene.

Medieval Era (5th–15th Century) Design: The chemise became a staple undergarment for both men and women. Made of linen, it was loose, long-sleeved, and extended to the ankles. Function: It was worn beneath heavy garments like gowns and tunics to keep outerwear clean and to provide a barrier between coarse fabrics and the skin. Cultural Significance: Modesty was paramount, and the chemise remained an unseen, functional item rather than an expression of sensuality.

Renaissance and Baroque Periods (15th–17th Century) Design Evolution: The chemise grew more intricate, often adorned with lace or embroidery, especially at the neckline and cuffs. It was still modest but began to reflect the wearer's status and wealth. Cultural Shift: While still hidden, the chemise's detailing hinted at the growing intersection of practicality and aesthetic appeal. Wealthier women often showcased embroidered chemise collars and cuffs as a subtle statement of luxury.

18th Century: Rococo and Romanticism Design: The chemise evolved into a softer, more feminine garment, often made from finer fabrics like muslin or silk. It gained popularity as part of leisurewear and even outerwear for aristocratic women. Cultural Significance: Marie Antoinette popularized the "chemise à la reine," a loose, flowing, chemise-inspired dress. This was revolutionary, signaling a departure from rigid corsetry and elaborate gowns toward a more natural silhouette. Lingerie Influence: The chemise began to symbolize elegance, intimacy, and the romantic ideals of femininity.

Victorian Era (19th Century) Design: The chemise became an essential part of a woman's layered wardrobe. It was worn beneath corsets and petticoats and typically made of cotton or linen. Functionality: Its primary role was protective, providing a barrier between the skin and corset bones. Cultural Role: As modesty remained highly valued, chemises reflected Victorian ideals of chastity and femininity. However, the lace and ruffled trims hinted at a growing awareness of lingerie as a personal indulgence.

Early 20th Century: The Edwardian Period to the Roaring Twenties Design Evolution: The chemise became sleeker and shorter to accommodate new fashions like the looser, columnar dresses of the 1920s. Silk and satin became popular materials, adding luxury and sensuality to the design. Cultural Significance: The chemise started transitioning from a purely utilitarian undergarment to a piece of intimate apparel that embraced freedom and movement. This was reflective of the era's progressive attitudes toward women's independence.

Mid-20th Century: Hollywood Glamour Design: Chemises embraced more tailored, figure-flattering designs during the 1940s and 1950s. Think silk slips with bias cuts that accentuated curves. Pop Culture Influence: Hollywood stars like Marilyn Monroe and Rita Hayworth popularized the chemise as a seductive, glamorous piece, cementing its role as a symbol of sensuality. Cultural Role: The chemise was no longer just lingerie—it became a representation of the idealized female form in media and fashion.

Late 20th Century: Lingerie as Outerwear Design Trends: The chemise took on bold, modern interpretations, including shorter lengths, sheer fabrics, and daring necklines. It began to blur the lines between lingerie and daywear, thanks to designers like John Galliano and Dolce & Gabbana. Cultural Shift: The rise of lingerie-inspired fashion challenged traditional notions of modesty. The chemise became a tool for self-expression, empowerment, and the celebration of femininity.

Contemporary Chemise Lingerie Design Today: Chemises now cater to a diverse range of preferences, from minimalist designs in organic cotton to elaborate pieces featuring lace, mesh, and intricate embroidery. They can be worn as sensual nightwear or as statement pieces in fashion. Cultural Significance: The chemise embodies both comfort and sensuality, representing the modern woman’s dual desires for practicality and self-expression. It has also become more inclusive, with brands offering chemises in a wide variety of sizes, styles, and fabrics.

Cultural Significance Across Eras Modesty to Sensuality: The chemise has transitioned from a symbol of modesty to an emblem of sensuality and self-expression. Practicality to Luxury: What began as a purely functional garment evolved into a canvas for artistry and indulgence. Empowerment: In its modern form, the chemise celebrates individuality, body positivity, and the freedom to define one’s own femininity.

0 notes

Text

It's getting chilly, so let's crank up the Fashion History Time Machine and savor a few lovely jackets and a cape from the Victorian era.

Silk velvet jacket with jet beads • c. 1895 • Cohasset Historical Society, Cohasset, Massachusetts, U.S.

House of Worth • silk, jet beads, linen • c. 1890 • Metropolitan Museum of Art

This is an excellent example of late 19th-century dress imitating men's wear of the late 18th century. This Worth jacket eloquently imitates the silhouette and the ostentatious quality of court costume of the previous century. The extraordinary jet beadwork embroidery is stylized to represent the elaborate silk floss embroidery of the past to great effect. – Metropolitan Museum of Art

#fashion history#women's fashion history#historical clothing#victorian era fashion#capes & jackets of the victorian era#house of worth#19th century fashion#metropolitan museum of art fashion institute#the resplendent outfit blog#fashion design

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Get ready to take a wild journey down the rabbit hole of historical unmentionables! We’re about to unveil 50 mind-boggling, jaw-dropping, and downright hilarious underwear stories that’ll leave you wondering if fashion history had a secret naughty side. From scandalous royal undergarments to the unexpected origin stories of our favorite skivvies, prepare to have your underpinnings of knowledge rocked! So, sit back, relax (preferably in your most comfortable undies), and get ready to be schooled in the fascinating, often cheeky, world of historical underthings. The Birth of Modern Corsetry! Minoan Snake Goddess Curious about the earliest signs of modern corsetry? Look no further than the Minoans of ancient Crete during the Bronze Age. Flourishing in a matriarchal society where women held sway while men were off engaged in seafaring trade, Minoan women exhibited remarkable style. Adorned in intricate bell-shaped wool skirts, adorned with jewelry, sporting exotic hairstyles, and donning what seemed to be early versions of corsets. In fact, the famous statue of Minoan Snake Goddess proudly wears a gold corset-style waist cincher and a flounced skirt with resembles a crinoline. When the intrepid seafaring men of Minoa returned from their voyages, they brought back more than just exotic goods – they brought a wave of inspiration that swept through the island’s fashion scene. Laden with luxurious fabrics and novel styling techniques from distant lands, these sailors sparked a sartorial revolution among Minoan women. Their return heralded an era of cosmopolitan glamour, where each new arrival from the sea whispered secrets of distant lands into the eager ears of Minoa’s fashionistas, shaping the island’s chic and setting trends ablaze with each incoming tide. Minoan trading shipsThe Secret Symbolism of the Lady’s Garter The origin of the order of the Garter. Illustration by Raphael Tuck, c 1920 What started as a wardrobe malfunction turned into a royal fashion statement, immortalizing the garter as a symbol of honor and chivalry! The “Order of the Garter” is one of the oldest and most prestigious orders of chivalry in England, dating back to the 14th century. According to legend, during a medieval court ball, the Countess of Salisbury’s garter slipped off her leg while she was dancing near King Edward III. As courtiers snickered at the mishap, the king gallantly picked up the garter and placed it on his own leg, declaring “honi soit qui mal y pense” (shamed be the person who thinks ill of it). A Surprising Reveal: English Ladies and the Missing Underpants!” cartoon by Thomas Rowlandson The ladies’ tumble down a steep staircase reminds us that English ladies did not wear any underpants until the 19th century! The lack of underpants in earlier times led to quite a few blush-inducing moments for English ladies of the past. Picture this: no protective layer to shield them from the unexpected gust of wind or a misstep on uneven terrain. These accidental exposures caused more than a few crimson cheeks, Meanwhile, across the channel, the French were perfecting the art of “les caleçons” (which translates roughly as ‘knickers’) centuries BEFORE the English adopted underpants. In fact, French fashionistas have been flaunting sexy lace lingerie since the 18th century, whereas British gals may still be wearing the ubiquitous Marks & Spencer’s plain cotton undies to infinity and beyond! Unveiling the Can-Can’s Secret: The Scandalous French Open Drawers The Can-Can dance, known for its high kicks and lively energy, originated in the working-class ballrooms of Paris in the early 19th century. It was initially a social dance performed by both men and women. However, it gained notoriety for its risqué and provocative nature, especially when performed by female dancers in cabarets and music halls wearing the French “open drawers”, guaranteeing that the final high kick would deliver quite a titillating view. The Can-Can remained a popular spectacle for decades, and the prospect of risqué undergarments added an extra “ooh-lah-lah” factor to its allure. CAN-CAN DANCERS Bottoms up, Ladies! Accidental exposures may have shaped the famous British Reserve. The great British reserve These accidental exposures caused more than a few crimson cheeks, which may have had a hand in the development of the infamous British reserve. In fact, those breezy and embarrassing mishaps perhaps contributed to the stiff upper lip that is now so closely associated with British. Who knows if underpants (or the lack thereof) played a role in shaping cultural demeanor? Victorian Petticoats Were a Fiery Fashion Disaster! The menace of death caused by the highly flammable six-foot-wide petticoats fueled one of the most vociferous, widely argued, and persistent objections to the garment – vulnerable to the open flames of fireplaces, candles, oil lamps, and matches, the huge crinoline skirts and petticoats frequently caught fire with fatal results. It’s estimated that between 1850 and 1860, approximately 3,000 deaths resulted from crinoline-related fires, as reported by the British medical journal, ‘The Lancet’. Colored lithograph (1860) via The Wellcome Collection.Fashion Mysteries: What Secrets did Queen Joan of Portugal Conceal under her Hoop Skirt in the 15th Century? Ah, the crinoline – not just a fashion statement, but a versatile tool for concealing life’s awkward little surprises! Who needs to be sent away for an inconvenient pregnancy when you can just let your expanding belly blend seamlessly into your wide-skirted ensemble? The crinoline’s voluminous layers were designed not just to fluff up dresses, but to keep society blissfully unaware of impending motherhood. Queen Joan of Portugal The hoop skirt first appeared in women’s fashion during the 15th century when Queen Joan of Portugal wore a circular mechanism, called a farthingale, rumored to disguise her pregnancy in 1468! Why bother with those awkward conversations when you can just swish around in your crinoline fortress, deflecting curious glances and inquiries with every rustle of fabric? Fashion’s Influence on Fairytales: The Brothers Grimm and the Corset Controversy! The Brothers Grimm, famous for their collection of dramatic German fairy tales, decided to add a little twist to the storybook narrative. In their classic tale of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, there’s a scene where the wicked stepmother attempts a rather unconventional murder weapon: a corset pulled way too tight. Snow White in a tight corset! In fact, this was in line with the 19th century opinion of German doctors who were vociferously opposed to corsets. They thought those waist-squeezing contraptions were a one-way ticket to organ displacement, restricted breathing, and even some seriously distorted body shapes – nevertheless, those waist-squeezers remained a hot commodity in the fashion scene. So, while the doctors may have had their reservations, it didn’t stop the corset craze from cinching its way into German closets (and fairytales) everywhere! Steel Corsets: Not Just for Tightening Waistlines, but Also Deflecting Daggers Catherine de’Medici During the 15th century, Catherine de’ Medici revolutionized fashion at the French court by introducing extremely tight 13-inch waist corsets – she even banned thick waists from her court! Additionally, she pioneered the use of metal corset covers made of thin steel plate. These steel covers were designed in a basket weave pattern with drilled holes to pass a needle and thread through to attach luxurious velvets and silks. These covers served a practical purpose, providing protection against the prevalent knife attacks of the time. Miracle workers: crinolines sometimes saved lives! Featured in the pages of Frank Leslie’s Weekly, a renowned American illustrated literary and news publication, an extraordinary incident from 1858 recounts the tale of a young woman who, while stepping onto a boat, found herself abruptly slipping into the water. In the midst of battling a powerful current that threatened to sweep her away, fortune smiled upon her due to her attire—a crinoline. Astonishingly, this undergarment turned into an impromptu flotation aid, guiding her safely downstream until a vigilant boatman came to her rescue. Satire on the fashion for crinolines, The British Museum c.1850In another news report, in 1867, a young girl skating in Canada faced a precarious situation when the ice beneath her feet unexpectedly cracked. Yet, her dependable crinoline astonishingly morphed into an unlikely savior, ensuring her dress remained buoyant and her morale stayed high until timely assistance arrived. Hidden in the Hoops: The secret role of Crinolines in the art of smuggling. During the 19th century, crinolines not only shaped women’s fashion but also played a surprising role in smuggling endeavors. These voluminous hoop skirts, known for their expansive and often impractical design, provided an ingenious cover for individuals involved in smuggling goods. Underneath the layers of fabric and wire, creative smugglers found ample space to conceal all kinds of contraband items, from expensive cuts of meat to luxury goods and valuable documents. “Lobster Larceny: A Crinoline Caper”The exaggerated silhouette of crinolines allowed for hidden compartments, making it difficult for authorities to detect the illicit activities. This unconventional use of fashion allowed individuals to bypass strict regulations and border controls, turning crinolines into unexpected accomplices in the world of smuggling. As fashion history intertwines with tales of subterfuge, the crinoline’s role in smuggling adds a unique and intriguing layer to its already captivating narrative. Before reliable birth control: the unspoken reason for wearing unattractive nightwear! In the Victorian era, regardless of class, the preferred nightgown style was long, white, and as modest as a prudish aunt at a tea party. Anything fancier was deemed a sign of improper bedtime behavior. Handmade nightgowns from the Victorian era. Image source: Metropolitan Museum of Art.But perhaps, before the days of reliable birth control, unattractive nightwear wasn’t just a style choice – it was a clever strategy rooted in an unspoken goal: limiting the quantity of intimate relations that could lead to a bun in the oven. Victorian parents with a crying baby These ugly sleepwear choices provided a shield of coverage. So, while it might seem like women were sporting less appealing sleepwear back then, they were actually masterfully navigating a world where bedtime was a landmine. The original purpose of underwear: to protect the outer clothes from the wearer’s unwashed body! Imagine a time when people rarely bathed, laundry day was an ordeal, and outer clothes were handmade, often with elaborate embroidery and hand tatted lace. In these bygone days, undergarments – known as ‘body linen’ – emerged as unsung heroes, protecting precious outer garments from the perils of the unwashed body. They bravely intercepted sweat and odor, preserving the integrity of fashionable attire. Even washing underclothes was no simple task. According to household manuals of the time, the process typically began with an overnight soak before moving on to a series of rigorous steps the following day: soaping, boiling or scalding, thorough rinsing, wringing out, mangling, drying, starching, and ironing, often necessitating repetition to achieve desired cleanliness. Laundry day in the Victorian age It’s worth mentioning that this extensive washing regimen was exclusively for undergarments and household linens such as bedding, towels, and kitchen cloths. Due to the harshness of the laundering process, most outer clothing was typically cleaned through brushing rather than washing. The popularity of silk underwear originally stemmed from the belief that silk was less liable to harbor lice! In bygone eras, the popularity of silk lingerie was not for its sensual appeal. Believe it or not, historical records reveal a surprising function of silk undergarments: they were thought to be a robust defense against the uninvited companionship of lice! While it might sound like an odd and amusing notion today, there was some logic behind this belief. Silk’s smooth texture was believed to be less hospitable to lice, making it a preferred choice for those aiming to avoid these unwanted guests. This unique twist in the history of undergarments adds a layer of intrigue to the evolution of lingerie, showcasing how functionality and fashion often intertwined in fascinating ways. The peculiar legal reason behind the unpopularity of woolen underwear! In the quirky annals of fashion history, the realm of undergarments presents us with an unexpected tale of woolen woes and legal mandates. In the days of yore, undergarments crafted from wool were the norm – and one imagines a degree of itchiness and discomfort that accompanied this choice. However, wool underwear was often finely knitted and may have been quite snuggly! Burial in wool affidavitNonetheless, an unfortunate stigma attached itself to wool – a backlash from the infamous “Burial in Woolens Act” of 1678, a legislation designed to boost the British wool trade. This peculiar law mandated that people be buried in woolen shrouds to support the local wool industry. This law unwittingly left its mark on fashion history. This wooly burial requirement was repealed in 1814, however, woolen undergarments did not return to its former heights of popularity until the end of the century. Off with their heads – or at least their corsets! Following the French Revolution, a wave of anti-aristocratic sentiment swept through fashion, prompting women to shed their corsets and discard heavy, rigid dresses in favor of draped, lightweight muslin cotton garments reminiscent of classic Greek styles. Embracing a more natural silhouette, they adopted the practice of wearing pink stockings and slips underneath to create the illusion of being naked. Some even dampened their dresses for a transparent, wet T-shirt effect. However, this trend proved short-lived, as the thin fabric was ill-suited for colder European climates. By the early 19th century, women began covering up once again, with the resurgence of the whalebone corset by 1830. 18th Century wet t-shirt contest! Leg fashions for Men with skinny legs – when faced with short pants, calf pads became all the rage! Men have had their fair share of creative enhancement throughout history! In the dapper days of the 1700s and 1800s, the male pursuit of shapely legs took a rather innovative turn – the rise of artificial calves. Just as women embraced corsets, petticoats, and other magical fashion tricks, men strutted around with these cunning contraptions snugly strapped to their lower limbs. These faux calves weren’t just for the sake of a good leg day; muscular legs were a symbol of virility and prestige. Imagine the Victorian-era gentlemen showcasing their sculpted calves, the pads adding an extra oomph to their swagger. So, while padded fashion has often been associated with women’s wear, let’s give a round of applause to the gents who dared to play the fashion game with style and flair, even if it meant donning a pair of cheeky artificial calves. Regal Rumps: Queen Victoria’s Oversized Underwear Fetches a Royal Sum! It seems Queen Victoria’s knickers were quite the royal flush at auction, fetching a whopping £12,090 ($16,000) by an anonymous collector! With a waistband measuring 45 inches, those knickers could probably double as a sail for a small boat. Who knew that under all those layers of regal attire, Her Majesty was sporting some roomy undergarments fit for a queen-sized comfort? We’re certain the late queen would be blushing royally if she knew about this! Queen Victoria’s royal insignia embroidered on her knickers. Children in Corsets: A Victorian Prescription for Proper Posture. Yes, believe it or not, children were not exempt from the corset craze of yesteryears! While the notion of corsets for children might raise eyebrows today, for the Victorians, it was considered a matter of health rather than fashion. In an era where maintaining warmth and proper posture were deemed essential for well-being, corsets were considered a practical garment even for the young ones. Believed to provide warmth to the body and support to maintain an upright posture, corsets were seen as pillars of health in Victorian society. While modern sensibilities may view such practices skeptically, it underscores the vastly different perspectives on health and fashion that prevailed in the past. Read on…for MORE Astonishing Underwear Stories from History You Probably Never Knew! “Bloomers” were named after Amelia Jenks Bloomer, an American suffragette! Amelia Jenks Bloomer, a 19th-century American women’s rights advocate and suffragette, is famously associated with her namesake “bloomers,” a revolutionary style of clothing that challenged traditional Victorian dress norms. Inspired by the desire for greater comfort and mobility, as well as the emerging women’s rights movement, Amelia Bloomer advocated for a change in women’s fashion to promote practicality and freedom of movement. Amelia Jenks Bloomer in her eponymous ‘bloomers’. The “bloomers” consisted of a loose-fitting knee-length dress worn over a pair of loose trousers gathered at the ankles, which allowed women to engage in physical activities and pursue an independent lifestyle. Though the bloomers faced public controversy and criticism, Amelia Bloomer’s efforts contributed to the ongoing evolution of women’s fashion and the broader fight for women’s rights. Barbie Pink Underwear – in the 18th Century! The advent of chemical dyes in 1860 introduced the vibrant ‘magenta,’ dubbed the ‘queen of colors,’ ushering in a new era of fashion. Emerging as a trendsetter in the 18th century, pink was seen in everything from opulent gowns to daring undergarments, raising eyebrows and breaking convention. The vibrant color shocked elders, who predicted the downfall of civilization, but pink persisted as a symbol of beauty and luxury. Barbie pink corset from the Victoria & Albert Museum Stepping into the Ladies’ Boudoir: The Industrial Revolution’s Fashionable Entrance! The evolution of crinolines traces a fascinating journey through fashion history, progressing from the early horsehair versions to the sturdier steel designs, and ultimately culminating in the lightweight and innovative cage crinoline. Each iteration represented a significant advancement in structure and support, reflecting the changing tastes and needs of women’s fashion during that era. And when cage crinolines strutted onto the scene, it was as if engineering and fashion had a whirlwind romance. As steel frames replaced horsehair, it was like upgrading from a heavy and cumbersome garment to a lightweight, high-tech marvel. The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Crinoline Cage Crinolines: Sheffield’s Steel Industry’s Weekly Wire Extravaganza! Factory workers making crinolines. Ah, the cage crinoline of the 19th century – a real social equalizer. This fascinating contraption united people from all walks of life, from the aristocrats to the factory-floor workers. The popularity was so insane that Sheffield factories were cranking out enough crinoline wire to wrap around the Earth…okay, maybe not that much, but by 1859 they were producing enough wire for half a million of these fashion wonders every week! Gentlemen Lost in a Land of Giants! But hey, let’s not forget, not everyone was applauding this trend. Shop workers wearing crinolines faced a significant backlash as their voluminous skirts obstructed aisles and posed safety hazards, leading to accidents and damage to merchandise. Employers often enforced strict rules against wearing crinolines to work, opting for more practical and streamlined attire to ensure efficiency and safety in the workplace. And you can’t blame the gentlemen for feeling a bit miffed – they must have been wondering if they had entered a land of giants because, let’s be honest, where’s a guy supposed to fit when the ladies have transformed into towering fashion colossi? Dressed to kill! How the many layers of Victorian underwear (inadvertently) protected ladies from arsenic poisoning! In Victorian England, arsenic wasn’t just a danger lurking in the shadows—it was a key player in the world of fashion. ‘Thanks’ to the Industrial Revolution’s innovations, arsenic became the go-to for creating eye-popping dyes, like the infamous “Scheele’s Green” and later the lighter toned “Paris Green” invented by Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. Because these hues were very cheap to produce, they found their way into everything from gowns to wallpaper, paints, toys, confectionary, and even beauty products. However, a silent peril lurked: with some garments packing up to a staggering 900 grams of arsenic, the line between fashion and fatal toxicity was alarmingly thin, reminding us that sometimes, style came at a deadly cost. A Skeleton Gentleman Invites a Lady to Dance: A Humorous Depiction of the Arsenic-laced Clothing TrendHowever, the inadvertent benefit of the many layers of Victorian ladies’ underwear was avoiding prolonged contact with arsenic-infused fabric. This was largely due to the sheer number of undergarments required during that era, including pantalettes, bloomers, corsets, petticoats, and crinolines. With each layer acting as a barrier, women had added protection against direct contact with poisonous dye, unintentionally safeguarding their health amidst the fashion trends of the time. Romantic Sailors Carved the Corset Busk as a Token of Affection! The busk, a long paddle-shaped piece, served as a stabilizing force down the center front of corsets and were often carved by sailors on their long sea voyages. They were crafted from an array of materials like wood, ivory, and bone. Interestingly, because of their intimate nature and proximity the heart and breasts, these doubled as sentimental tokens given from men to their lovers, inscribed with heartfelt messages or love poems that could be worn in secrecy. Scrimshaw busk showing whaling ships sailing into port. Charles Whipple Greene Museum, Smithsonian Institute’s whalebone busk with a love poem on the back. Snug as a Bug: The Cozy Charm of Union Suits! Ah, the ubiquitous union suit, a men’s underwear staple for years – but it was originally designed for the ladies! Affectionately known as the “emancipation suit,” it was championed by pioneering women advocating for dress reform. While the typical image of the onesie might conjure thoughts of red flannel, complete with a cheeky bum flap favored by rugged lumberjacks or mustachioed gentlemen, and immortalized in cowboy movies, it’s fascinating to note that this garment once played a significant role in the women’s rights and dress reform movements of the 19th century. Revolution on Two Wheels: How the Bicycle Ushered in an Era of Snug-Fitting Underwear! For centuries, fashion was a battleground of restriction, but beneath the surface simmered a yearning for freedom. Then, like a breath of fresh air, the bicycle arrived, offering not just movement but change. As women embraced this newfound freedom, they needed snugger underwear for activities like biking and tennis. The closer they pedaled to freedom, the smaller their undergarments became! The bicycle propelled women into an era of empowerment, where clothing choices were driven by progress, not societal norms. The origins of ‘Athleisure’! Doctor Jaeger introduced his groundbreaking ‘sanitary woolen system.’ based on his belief that wearing wool against the skin was necessary to absorb perspiration. “But surely a gentlewoman does not perform any activity that would produce such an unpleasant result!” complained someone writing to a lady’s magazine. It’s fascinating how Dr. Jaeger’s vision from over a century ago continues to resonate in contemporary fashion.Dr. Jaeger’s emphasis on utilizing wool for its breathability and moisture-wicking properties was quite ahead of its time. Industrial knitting machines became the unsung heroes of hygiene in fashion, cranking out Dr. Jaeger’s woolly wonders with efficiency and flair – and laid the groundwork for what we now recognize as the athleisure trend, where clothing seamlessly transitions from athletic activities to everyday wear. By promoting garments that supported an active lifestyle while prioritizing hygiene, Dr. Jaeger essentially anticipated the modern fusion of performance and leisurewear. The Famous Bikini Girls of Ancient Greece! The “bikini girls” of ancient Greece, found in the Tomb of the Diver frescoes, depict women sporting two-piece garments remarkably similar to modern bikinis. Dating back to the 5th century BC, these playful artworks offer a charming glimpse into ancient Greek leisure and fashion. But the ancient Greek “bikini girls” weren’t just beach babes. A lesser-known fun fact is that their depictions weren’t just about showcasing physical beauty; they also represented athletic prowess and the celebration of the female form in sports. These depictions highlight the significance of athleticism and physical fitness in ancient Greek culture, where sports were not only recreational but also integral to education and social life. Bikini Babes vs. Victorian Wallflowers: A Swimwear Saga From the agile grace of ancient Greek bikini-clad athletes to the restrained movements of Victorian women, the contrast in athleticism couldn’t be starker! “Mermaids at Brighton” by William Heath c. 1829 In the Victorian era, the trend for swimming wasn’t just about leisure; it was rooted in the belief in the therapeutic benefits of water. However, like many Victorian pursuits, swimming came with its own set of elaborate customs and rituals. Swimwear of the time was far from simple, consisting of intricate skirted tunics, bloomers, and dark stockings. Victorian bathing machines on the beach. Adding to the spectacle were the infamous “bathing machines,” specialized carriages rolled into the water to preserve modesty and provide privacy for bathers. These contraptions remained in use well into the 19th century, offering a discreet means of entering the water directly instead of wading in. Their design was praised for its ability to maintain modesty while enjoying the pleasures of bathing. This elaborate approach to swimming underscored the Victorian penchant for ceremony and tradition in every aspect of life. Making Waves: Annette Kellerman’s Aussie Swimwear Revolution! In a splash heard ’round the world, Annette Kellerman, the Australian professional swimmer found herself in hot water—quite literally—when she got arrested for daring to sport her scandalously sensible one-piece bathing suit in 1907. While the fashion police were busy worrying about decency, Kellerman was busy making waves in the swimwear scene, proving that sometimes you have to break the rules to make a splash. In an era when women’s bathing attire consisted of cumbersome layers and restrictive garments, Kellerman dared to challenge the status quo. Advocating for freedom of movement and practicality, she championed the one-piece bathing suit as the ideal solution for women eager to enjoy aquatic activities without constraints. Annette Kellerman’s one piece bathing suit revolution! Her eponymous line of swimwear, aptly named “Annette Kellermans,” signaled a seismic shift in women’s fashion, propelling swimwear into the modern age. Crafted with innovation and designed for performance, her swimsuits not only liberated women from the burdensome attire of the past but also empowered them to embrace their athleticism and independence. And in true Aussie spirit, she wasn’t afraid to make waves – both in and out of the water! Two WW1 Battleships Built with Corset Steel! World War I dealt a blow to the corset’s reign, nudging it aside in favor of the bra. As part of the war effort, women were urged to ditch their corsets to free up steel. They complied willingly, sacrificing their 28,000 tons of steel from their shapewear – enough to build two battleships. Who knew corsets could be so patriotic? Bra-volution Begins: The First Patent that Started it All! Socialite Mary Phelps encountered a wardrobe dilemma when her floaty debutante ball gown was ruined by the rigid whalebone corset, which caused unsightly bulges under the sheer fabric. In a stroke of innovation, she improvised a solution by fashioning a makeshift, corset-free undergarment using two handkerchiefs and ribbons. This ingenious creation earned her a patent for the “backless bra” in 1914 – in fact, the American patent office created a brand new category named ‘the brassiere’ – and laid the foundation for her business venture, ‘Caresse Crosby.’ Warner Brothers Corset later acquired her invention for $1500, reaping immense profits from her innovative design over the ensuing decades. Mary Phelps bra patentBikini Blast: A Fashion Explosion! In 1946, French fashion took a daring leap as Jacques Heim unveiled the “Atome” (French for “atom”) 2-piece swimsuit, intended to stir the same shockwaves as the recent atomic bombings in Japan. Just two days later, rival designer Louis Réard upped the ante with an even skimpier creation—the “bikini.” With a wink to nuclear testing on the Bikini Atoll Islands, Réard succeeded in igniting a fashion own explosion. His design, featuring a daring newspaper print, signaled a radical departure in swimwear style. The first ‘bikini’The provocative naming choices of the “Atome” and “bikini” swimsuits might not be met with the same enthusiasm today. While they certainly made a splash in their time, their association with atomic imagery and nuclear testing raises eyebrows in contemporary contexts. The Sexy Revolution: Frederick’s of Hollywood Redefining Underwear Before the 1940s, women’s underwear was all about shaping the body. But then along came Frederick’s of Hollywood, shaking up the scene with a whole new vibe. It wasn’t for comfort or function – it was all about oozing sex appeal, designed to appeal to men, bored housewives, and exotic dancers alike! Vibrating Bra In March 1971, at the 20th International Show of Inventions in Brussels, one particularly curious product caught the eye: the “vibrating brassiere.” This contraption featured two spiraling metal bands linked to a small electric motor worn discreetly on the back. According to its creator, the device promised to strengthen and develop the bust with its innovative design. Struck by Fashion: The Shocking Truth About Underwire Bras and Lightning Fact or urban legend? In 1999 two friends tragically met their end in Hyde Park, London, struck by lightning allegedly conducted through the wire in their bras. The incident sparked debates over the safety of underwire bras during thunderstorms, with unconfirmed reports suggesting the metal components may have attracted the fatal discharge. The question lingers. Triumph’s Fishbowl Bra Keeps You Cool in Summer Swiss lingerie maker, Triumph, introduced its innovative “Super Cool Bra” at a grand reveal in Tokyo on May 9, 2012. Inspired by a miniature fishbowl, this unique bra incorporates gel material in its cups, aimed at extracting excess body heat to keep wearers feeling refreshed, especially during the sweltering summer months. The lingerie maker envisions women enjoying a cooler and more comfortable experience with this cutting-edge design – presumably, it went to market without the fish! Source: REUTERSJockey’s Cellophane Wedding & Hitler‘s Surprise Reaction Before 1934, men were limited to either boxer shorts or union suits (you know, the full-length ones with the infamous “back door” flap). But all that changed with the invention of the supportive knit Jockey brief. However, there was a small problem: decency laws of the time prohibited live models from just wearing underwear. So, in a stroke of marketing genius, the company came up with the idea of dressing their models in cellophane to showcase their innovative new product. Jockey’s advertising campaign – the ‘Cellophane Wedding” In 1938, they went all out at the National Association of Retail Clothiers and Furnishers convention, decking everyone out in full cellophane glory. The stunt made headlines, even catching the attention of Adolf Hitler, who used it as an excuse to rant about America’s supposed moral decline. Talk about making an impression! Nylon Stockings for Donkeys, Horses and Camels Animal loving Mrs. F.K. Hosall from England sparked a charitable sensation in February 1926. Her ingenious plan? To gather old silk stockings from generous women and ship them off to northern Africa. But these stockings weren’t destined for glamorous legs; they were intended as a quirky solution to protect donkeys, mules, and camels from pesky fly bites! If you ever find yourself in the company of a well-dressed camel, perhaps you’ll catch a glimpse of those silk-clad legs and think of Mrs. Hosall’s legacy. Mouse-shocking Pantyhose In a peculiar showcase of innovation at the Annual Congress of the Inventors of America in Los Angeles in September 1941, a rather electrifying invention stole the spotlight: women’s pantyhose designed to fend off mice! Dubbed the “shocking stockings,” these unconventional garments boasted a unique construction of fine-spun copper mesh, with hidden batteries nestled within the wearer’s shoes. Intriguingly, wires snaked through the stockings to a coil concealed in the girdle, ready to deliver a zap of voltage upon contact with a mouse. Despite the shocking premise, the inventor assured that these electrifying stocking posed no harm to the wearer – but they never appear to have gone into commercial production. Burning the Bra – Unraveling the Myth Last, but not least in the world of underwear stories, the legend of bra-burning feminists in the 1960s has more twists than a pretzel! Turns out, the fiery protest never actually happened. It was all the brainchild of Lindsy Van Gelder, a reporter with a knack for storytelling. Covering a feminist rally against the 1968 Miss America pageant, she spun a tale of women tossing bras into a “freedom trash can” alongside girdles, high heels, makeup, and Playboy magazines – all symbols of female oppression. But as Van Gelder later lamented, she inadvertently sparked a myth that stuck to her like a stubborn bra strap saying that she shuddered to think that her epitaph will be ‘she invented burning the bra’. The myth of Bra-burning feminist! Read Next: Secrets of Time Travel Source link

0 notes

Photo