#élisabeth de france

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Élisabeth de France (1764-1794) par Adélaïde Labille-Guiard.

#royaume de france#maison de bourbon#Adélaïde Labille Guiard#élisabeth de france#princesse de france#fille de france#fils et filles de france#kingodom of france#house of bourbon

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Passive resistance

Condé feared that the king would become the tool of a nonentity or coquette, but it did not enter his head that the monarch could use the crutch of a friendship to realize his own political goals. Marie was even less astute, reportedly devising the strategty of surrounding him with persons of "mediocre capacity and little spirit." Among these was the man who would help Louis overthrow his mother and her favorite.

His name was Charles d'Albert, sieur de Luynes. Stories circulated that Luynes and his two younger brothers shared the same best suit, and that a hare could quickly jump across their family lands. Yet they were of the same lesser nobility that had predominated at the Estates General. Henri IV's friendship for Luynes' father, a soldier of fortune, caused him to place the younger Luynes among the dauphin Louis's noble comrades. The gentilhomme began to look after the heir's birds of prey; and the young boy's fondness for the gentle, handsome, and supportive middle-aged man grew.

By the end of 1614 Louis's attachment was so strong that it bothered Queen Mother Marie, her Italian favorite Concini, and the king's former governor, Souvré. Yet Luynes remained in Louis's favor and his brothers also gained easy access to the king. How did the king prevent a sequel to his mother's earlier banishment of Alexandre de Vendôme? We need follow only one example. In October 1614, Souvré made the Albert brothers stay away from the royal bedchamber, even during the ceremonial lever and coucher, hoping to supplant the gentleman-favorite with his own son, Courtenvaux. Someone told the king that his former governor was responsible, and Louis countered by treating Souvré with silence and dark looks, until the mortified man got the queen mother to negotiate an accommodation.

In employing passive resistance here, Louis had discovered the only way he could assert himself, considering the queen mother's imperiousness and his own timidity. The son also held his ground in refusing to tell his mother who had told him of Souvré's maneuver against Luynes, until she promised not to punish that individual. Equally revealing was the fact that Louis did not bear a grudge against Souvré or Courtenvaux, both of whom he actually liked. He paid for all this agitation with a soaring pulse and symptoms of illness. This powerful combination of indirect strategy, fierce loyalty, forgiveness, and sacrifice of personal health, then, separates the real adolescent Louis XIII from both the weakling and the vindictive Louis of historical fiction and scholarship.

If the court was baffled by the dynamics of Louis's friendships, it was equally unaware that his interests always had a serious element, even when they appeared frivolous. When he sketched with pen and ink, it was of horses pulling cannon, although incongruously placed in a child's setting of trees, churches, and village brides. Louis dutifully took part in court masques and ballets; however, his dislike of elaborate protocol and showing off caused him to refuse outright to lead his sister Elisabeth in a dance before the Spanish ambassador. The Spaniards were disconcerted by this affront so close to the marriages of Louis and Elisabeth to the children of King Philip III of Spain, Anne of Austria and the future Philip IV. The French court poet, Malherbe, could only comment: "If age and love don't change his ways, he will be inquisitive only of things that are solide."

A. Lloyd Moote - Louis XIII the Just

#xvii#a.lloyd moote#louis xiii the just#louis xiii#marie de médicis#charles d'albert de luynes#henri ii de bourbon-condé#concino concini#gilles de souvré#alexandre de vendôme#élisabeth de france#anne d'autriche#philippe iv d'espagne#malherbe

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Édouard Debat-Ponsan (French, 1847-1913) Portrait de mademoiselle Élisabeth de Vilmorin (future comtesse d'Estienne d'Orves) au bouquet de fleurs, 1891 Paris, Société nationale d’horticulture de France

#Édouard Debat-Ponsan#French#France#portrait de mademoiselle elisabeth d'orves#mademoiselle Élisabeth de Vilmorin#countess#aristocracy#royalty#royal#aristocrat#lady#noble#nobility#french art#france#art#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#fine arts#oil painting#europa#paris#brunette#woman#female

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oil Painting, 1787, French.

By Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.

Portraying Marie Antoinette in a red velvet dress with black fur trim, with her children.

Château de Versailles.

#élisabeth vigée le brun#marie antoinette#marie Thérèse de France#Louis Charles de France#womenswear#1780s womenswear#1787#1780s#1780s painting#1780s France#red#louis Joseph of France#dress#1780s dress#royalty#ancien regime#château de versailles

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

france is gonna have a late celebration of the ides of march and i'm so here for it

#france#ides of march#allez les députés on fait passer la motion de censure on dégage élisabeth “dolores umbrige” bornes#après on assiège l'élysée on décapite macron et on interne brigitte

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's random fanfiction is from the L'Échange des princesses | The Royal Exchange (2017) fandom. Rien à voir. by AngelicaR2

Chapters: 1/1 Words: 336 Fandom: 18th Century CE RPF, L’Échange des princesses | The Royal Exchange (2017) Rating: General Audiences Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Relationships: Mme de Ventadour & Marie Anne Victoire d'Espagne Characters: Mme de Ventadour, Marie Anne Victoire d'Espagne, Louis XV de France, Louise-Élisabeth d'Orléans Additional Tags: Spain, Versailles - Freeform, 18th Century, Drabble, Hope, Travel, differences Language: Français Summary: [L’Échange des princesses] : Drabble. “Marie Anne Victoire n'a rien à voir avec Louise-Elizabeth, et Mme de Ventadour espère sincèrement que cela ne va pas changer.”

#fic rec#random fanfiction#random#random recs#fanfic#ao3#fanfiction recommendation#fanfic rec#fanfiction#ao3 fanfic#18th Century CE RPF#L’Échange des princesses | The Royal Exchange (2017)#Mme de Ventadour & Marie Anne Victoire d'Espagne#Mme de Ventadour#Marie Anne Victoire d'Espagne#Louis XV de France#Louise-Élisabeth d'Orléans#Spain#Versailles - Freeform#18th Century#Drabble#Hope#Travel#differences

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do we know the favorite books that the French revolution figures liked to read? (It could be anyone, Robespierre or Saint just or Louis xvi it doesn't matter).

Much like this old ask about revolutionaries’ favorite dishes, I can’t say I know of any instance of someone exclaiming: ”this is 100% my favorite book,” but at tops people mentioning books that they thought were good or bad:

In his memoirs, Brissot writes he’s picking up Rousseau’s Confessions for the sixth time, so I guess that could qualify as a favorite book? send help

We have this list of books seized at Robespierre’s place after his death.

According to the memoirs of Élisabeth Duplay, Robespierre would read ”the works of Corneille, Voltaire and Rousseau” for her family in the evenings.

In a short biography over Desmoulins written in 1834, Marcellin Matton claims his favorite book was René Aubert de Vertot’s Histoire des révolutions arrivées dans le gouvernement de la République romaine (1719), of which he always carried a copy. Matton is an infamous romanticizer it’s from him we have the stupid leaf myth for example, but I’m willing to give him some leeway here since he could have obtained the information from Camille’s mother-in-law and sister-in-law, who were his friends:

In one of his first classes, he received Vertot's Révolutions romaines as a prize. Reading this work transported him with admiration; in the future, he always had a volume in his pocket. It was for him an indispensable companion, it was his vade mecum. He used or lost at least twenty volumes. It is perhaps to this excellent work and to the particular work that he did on the discourses of Cicero and especially on his Philippics, that we owe the lively and sharp style which distinguishes all the writings coming from the pen of Camille .

Desmoulins was however less fond of Rousseau’s Confessions, in number 55 (December 1790) of Révolutions de France et de Brabant he admits that he abandoned the book after getting infuriated by it:

Not that I idolize J.J. as I did in the past, since I saw in his Confessions that he had become an aristocrat in his old age. How far he was from looking at an Alexander with the pride of this Cynic, to whom he is compared, and how painfully I saw that he united the opposite faults of Diogenes and Arisippus! It is a pleasant thing to hear the author of the Social Contract protest in his Confessions about the simplicity of the commerce of such great lords (M. and Madame de Luxembourg) he cries with joy, he wants to kiss the feet of this good marshal, because he wanted to accompany one of his friends, an office clerk, for a walk. Is there anything smaller, more ridiculous? I received, he says elsewhere, the greatest honor that a man can receive, the visit of the Prince de Conti, (an honor that Rousseau shared with all the girls of the Palais-Royal.) At this point I tossed away the book out of spite, and I admit, that I had to reread the speech on equality of conditions, and Julie's novel, in order to not hate the philosopher of Geneva, like Durosoy and Mallet du Pan; for the same principles, in the mouth of such a great man, are more condemnable and worthy of aversion than in the mouths of our two gazetteers, whom God created poor in spirit, and predestined as such to the kingdom of heaven.

In a diary kept over the summer of 1788, Lucile Desmoulins mentions reading L’Âge d’Or (1782) by Sylvain Maréchal (of which she also copied two verses, Le Trésor and Le contrat de mariage devant la nature, in a notebook the year earlier), Les Idylles et poèmes champêtres (1762) by Salomon Gessner, L’Hymne au soleil, suivi de plusieurs morceaux du même genre qui n’ont point encore paru (1782) by Abbé de Reyrac (where she wrote down the verse La Gelée d’avril), Nouvelles lettres anglaises, ou Histoire du Chevalier Grandisson (1754) by Samuel Richardson and Les Noces patriarchales, poëme en prose en cinq chants (1777) by Robert Martin Lesuire.

In his memoirs, Buzot mentions enjoying the works of Rousseau and Plutarch:

With what charms I still remember this happy period of my life which can no longer return, when, during the day, I silently roamed the mountains and woods of the city where I was born, reading with delight some works of Plutarch or of Rousseau, or recalling to my memory the most precious features of their morality and their philosophy. Sometimes, sitting on the flowering grass, in the shade of some thick trees, I indulged, in a sweet melancholy, in the memories of the sorrows and the pleasures which had in turn agitated the first days of my life. Often the cherished works of these two good men had occupied or maintained my vigils with a friend of my age whom death took from me at thirty, and whose memory, always dear and respected, has preserved from many errors!

Wow any chance you can sound even more like an 18th century man stereotype, Buzot?

…and that’s basically all I can come up with for the moment. But add on if you know anything more! @louis-antoine-leon-saint-just @lazarecarnot maybe you would like to share your favorite books with us if you have any?

#frev#ask#robespierre#desmoulins#lucile desmoulins#buzot#brissot#camille actually being the only sane person

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madame Françoise de France, 1895

**DO NOT REPOST**

Artist: Tintexture (twi: Tintexture)

Reference:

Clothes - A Worth evening gown once belonged to Countess Élisabeth Greffulhe, Proust's Muse

Facial feature - young Catherine Deneuve

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical Portraits of Children // The Truth is a Cave – The Oh Hellos

Four Children Making Music – attributed to the master of the Countess of Warwick, 1565 // Three Children with a Dog or Two Sisters and a Brother of the Artist – Sofonisba Anguissola, 1570-1590 // The Children of Philip III of Spain (Ferdinand, Alfonso, and Margarita) – Bartolomé González y Serrano, 1612 // Three Children with a Goat-Cart – Frans Hals, 1620 // The Balbi Children – Anthony van Dyck, 1625-1627 // The Three Eldest Children of Charles I – Anthony van Dyck, 1635-1636 // Five Eldest Children of Charles I – Anthony van Dyck, 1637 // Portrait of the Children of Habert de Montmor – Philippe de Champaigne, 1649 // Group Portrait of Charlotte Eleonora zu Dohna, Amalia Louisa zu Dohna, and Friedrich Christoph zu Dohna-Carwinden – Pieter Nason, 1667 // The Graham Children – William Hogarth, 1742 // Portrait of Sir Edward Walpole’s Children – Stephen Slaughter, 1747 // The Bateson Children – Strickland Lowry, 1762 // The Gower Family: The Five Youngest Children of the 2nd Earl Gower – George Romney, 1776-1777 // Marie-Antoinette de Lorraine-Habsbourg, Queen of France, and Her Children – Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, 1787 // The Marsham Children – Thomas Gainsborough, 1787 // The Oddie Children – William Beechey, 1789 // Three Siblings – Johann Nepomuk Mayer, 1846 // Happy Children – Paul Barthel, 1898 // My Children – Joaquín Sorolla, 1904 // The Truth is a Cave – The Oh Hellos

#this line makes me feel Very Normal and not at all Deranged 🥴😵💫#portraiture#family portrait#portrait#portrait painting#sofonisba anguissola#frans hals#anthony van dyck#philippe de champaigne#william hogarth#george romney#elisabeth vigee le brun#elisabeth louise vigee le brun#thomas gainsborough#joaquin sorolla#the truth is a cave#the truth is a cave song#the truth is a cave the oh hellos#through the deep dark valley#through the deep dark valley album#through the deep dark valley the oh hellos#the oh hellos#art history#art#lyrics#lyric art#long post

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of the Marquise de Grollier, nee Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny Damas

Artist: Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755 – 1842)

Genre: Portrait

Date: 1788

Description

Charlotte Eustace Sophie de Fuligny-Damas, more commonly known as the Marquise de Grollier (21 December 1741, Paris – 1828, Épinay-sur-Seine), was a French flower painter.

In 1760, de Fuligny-Damas married Pierre Louis de Grollier, Marquis de Grollier and Treffort (1730-1793), the Governor of Pont-d'Ain and Deputy of the Nobility. The couple would have three children before separating. Later, they lived at the court in Versailles, where the Marquise de Grollier became friends with the portrait painter Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun. Le Brun would often mention Grollier in her diaries, describing her as “always simple and natural, and never showed any pretension, nor an ounce of pedantry.” The Marquise was attracted to the gardens at Versailles and later created one of her own in Lainville-en-Vexin.

In 1793, de Fuligny-Damas lost her husband to the guillotine and was forced to leave France. She went to Switzerland, then Germany and, finally, Italy. In Florence, her talent was soon recognized. The sculptor, Antonio Canova, once referred to her as the "Raphael of flowers". At this time, she also created some mosaics. Joseph-Marie Vien, Director of the French Academy in Rome, arranged for her return to France. She settled in with her nephew, Alexandre-Charles-Emmanuel de Crussol, at his château in Épinay-sur-Seine, where she practiced horticulture as well as painting. After his death, she began to give large sums to charity in his name.

In 1823, she prevailed upon the engineer, Louis-Georges Mulot, to create an artesian aquifer in the château's park to provide clean drinking water for the local villagers. The work lasted for three years. In recognition for her efforts, she was named one of the founding members of the "Société d'Horticulture". She died shortly after, aged 86.

#portrait painting#french nobility#marquise de gollier#french painter#flower painter#blue dress#elisabeth vigee le brun#18th century painting

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755-1842)

Elisabeth-Philippe-Marie-Hélène de France dite Madame Elisabeth

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Louise Elisabeth of France (1727-1759), Duchess of Parma, in court dress. By Jean-Marc Nattier.

#royaume de france#fille de france#maison de bourbon#louise élisabeth de france#duchese de parme#Madame Première#madame infante#princesse de france#jean marc nattier#court dress#kingdom of france#house of bourbon#regno d'italia#kingdom of italy#fils et filles de france#fils et filles de louis xv

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

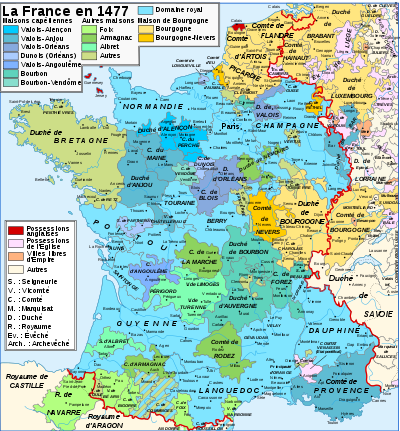

Expansion of the royal domain

The way in which the kingdom was ruled in its different provinces had always varied according to the degree that power had been permanently or temporarily devolved to apanage princes and great nobles or that representative assemblies continued to function. It is therefore axiomatic that there was no 'system of government' in the France of the Renaissance. The question is: was there a tendency for the kingdom to become more centralised? R. Bonney has wisely cautioned against the over-use in French history of the term 'centralisation', a term coined in 1794. The main distinction drawn in the early modern period, as Mousnier made clear, was that between the king's 'delegated' and 'retained' justice, the latter covering all the public affairs of the kingdom in which the crown was supreme and the former the private affairs of his subjects. No one would pretend, however, that a clear line of division was ever established between the two.

If we consider the case of the apanages and' great fiefs, for instance, the century from the reign of Louis XI is usually considered definitive in their suppression. In 1480, there were around 80 great fiefs. By 1530 around half of these still existed. The rest were in abeyance or held by members of the royal family. Within the royal house, the apanage of Orleans was reunited to the crown on the accession of Louis XII, although thereafter used periodically for the endowment of the king's younger son, permanently so after the reign of Louis XIV. The complex of territories held by the Bourbon and Bourbon-Montpensier families fell by the treason of the Constable in 1523. Burgundy (and temporarily Artois and Franche-Comté) were taken over in 1477. Among the great fiefs, the county of Comminges was united to the crown on the death of count Mathieu de Foix in 1453, the domains of the Armagnacs (such as the county of Rodez) were confiscated on the destruction of Jean V at Lectoure in 1473. They found their way by the reign of Francis I into the hands of the royal family, through the marriage of Jean V's sister to the count of Alençon. The last Alençon duke, Charles, married Francis I's sister, Marguerite of Angoulême, and Alençon's sister, Françoise, married duke Charles of Vendôme, grandfather of Henry IV. Brittany was acquired through war and marriage alliance in the 1490s, Provence and the domains of the house of Anjou after the death of king René and then of Charles d'Anjou in 1481. The archives of the Chambre des comptes of Anjou for the early 1480s give ample evidence of the king's determination to exploit his new acquisition as soon as possible.

It should not be assumed that the crown pursued a consistent determination to lay hands on all these territories and rule them directly. There was usually a more or less lengthy period of adjustment to a new status. Some apanages and territories taken over by Louis XI were absorbed into the general administration of the rest of the kingdom. This was clearly the case with Burgundy and Picardy-Artois in 1477, both of them in the area under the jurisdiction of the Parlement of Paris. Yet even here, Louis XI had to tread warily in winning over the support of the regional nobility and discontent was apt to break out until the end of the fifteenth century. On Louis's death, for instance, a rising occurred in Picardy at Bertrancourt near Doullens, with cries of 'there is no longer a king in France, long live Burgundy!' The absorption of Artois proved to be an impossible undertaking and had to be renounced in 1493.

Elsewhere, absorption of apanages that were distant from the centre of royal power left affairs locally much as they had been before. The little Pyreneen county of Comminges was governed much as it had been under its counts, with privileges confirmed by Charles VIII in 1496. Only with the work of royal commissioners in the tax-assessing process in the 1540s, the first time an outside power had actively intervened in the affairs of the local nobility, did this begin to change. Auvergne, an apanage raised to a duchy in 1360, was confirmed to the Bourbons in 1425 on condition that their whole domain became an apanage. The duchy was confiscated from the Constable in 1523 but transferred by the king to his mother in 1527 and only absorbed into the royal domain in 1531. Even after that, it formed the dower of Charles IX's queen and then part of the apanage of François d'Anjou, his brother. In the contiguous county of Forez, also confiscated in 1523, little local opposition emerged to the change of regime; although the local chambre des comptes was shortly suppressed, most local judicial officials, along with the entire administrative structure, were retained. Except for a few partisans of the Constable, it seems that there was no great upheaval. Louise de Bourbon, the Constable's sister and princess of La Roche-sur-Yon, demanded a share of the inheritance - Forez, Beaujolais and Dombes. Beaujolais and the principality of Dombes eventually went to Louise's son, Montpensier.

The county of Auvergne, enclaved in the duchy, was held by the duke of Albany in his wife's name, and was then inherited from the last of the La Tour d'Auvergne family by Catherine de Medici. Catherine brought it to the crown by her marriage with Henri II in 1533 but she continued to administer it as her own property. She left it to Charles IX's bastard, Charles de Valois, but her daughter Marguerite made good her claim to it in 1606 and it only entered the royal domain definitively when she willed it to Louis XIII.

After her marriage to Charles VIII in 1491, Brittany was administered as her own property by queen Anne, technically still duchess but in reality sharply circumscribed in her power, until her husband's death restored some of her freedom of action in 1498. Having already established friendly relations with Louis XII when he was still duke of Orleans, she was prepared to accept his offer of marriage after the annulment of his marriage to Louis Xl's daughter, Jeanne, had been agreed. The contract which accompanied the marriage in January 1499 tied the duchy to the crown provisionally on condition that it always passed to the second son of the marriage, while in the absence of issue the duchy was to revert to Anne's heirs on her own side. Anne was able to act rather more independently during her marriage to Louis XII though the conditions of the contract were not observed. On her death Brittany was inherited by her elder daughter Claude, wife of Francis I, who transmitted her rights to her son the dauphin. The queen had, however, transferred the government of the duchy to her husband in 1515 and he continued to rule it in the name of his son François on Claude's death, entitling acts as 'legitime administrateur et usufructuaire' of his son's property. When the dauphin's majority in 1532 brought the question of the imminent personal union of the duchy to the kingdom to the foreground, it was arranged for the Breton estates to 'request' full union with France but on terms which guaranteed Breton privileges and maintained the principle that the dauphin would be duke of Brittany. Only in 1536, on the death of the dauphin, was the union with the kingdom complete and no more dukes were crowned at Rennes. What had been done was the annulment of the Breton succession law, which included females, in favour of the French royal succession law. Late in 1539, it was decided that the new dauphin Henri would have the government of Brittany 'to govern as he pleases', though the documents were delayed by the king's illness. A 'Declaration' transferring Brittany to Henri was drawn up in 1540. In practice, the government of the duchy seems not to have been much changed.

The lands of the house of France-Anjou posed a complex problem. René of Anjou, titular king of Jerusalem, Sicily, Aragon and Naples, was count of Provence in his own right, of Maine and Anjou as apanagiste and Guise by succession. As early as 1478, Louis was scheming to ensure that king René, who had no surviving son, did not leave his territories of Anjou, Provence and Bar to his grandson, René II of Lorraine, warning the general of Languedoc that his region would be 'destroyed' if Provence fell into other hands. On the 'good' king's death in 1480, most of his domains passed to his cousin Charles IV d'Anjou, count of Maine, who died childless in 1481, when Maine and Anjou reverted to the crown, thereafter to be granted out to members of the royal family such as Louise of Savoy. At the same time Provence was acquired by Louis XI by Charles IV's will and the county of Guise was disputed between the houses of Armagnac-Nemours, Lorraine (heirs of René I of Anjou and successors as titular kings of Jerusalem and Sicily) and Pierre de Rohan, marshal de Gié. From 1481, however, the king ruled in Provence as 'count of Provence and Forcalquier'. The lord of Soliès, Palamède de Forbin, who had persuaded Charles d'Anjou to leave the county to the king, was rewarded with the post of governor. The major change came in 1535 with the edicts of Joinville and Is-sur-Tille on the government of Provence, limiting the scope of the old institutions of the Estates and the Sénéchal and increasing that of the Parlement of Aix in justice and of the royal governor in administration. Curiously, Francis I was reported as having said that he felt an obligation to 'ceux de Guise', the house of Lorraine in France, since Louis XI had despoiled them of their inheritance of Provence and Anjou.

The major surviving complex of apanage lands by the middle of the sixteenth century was that held by Antoine de Bourbon, now first prince of the blood and next in line to the throne after the immediate royal family, and his wife Jeanne d'Albret. These involved a group of territories held by different tenures. The Albret inheritance brought the titular kingship of Navarre with a small fragment of the ancient kingdom of Navarre north of the Pyrénées that was held in sovereignty. In the counties of Foix, Albret and Béarn, the family held effective sway under only the most distant royal sovereignty, though Louis XI saw fit to pose as the protector of the young François-Phébus in 1472. In 1476, he sought to revise local tariffs against Albret interests and in 1480 attempts to levy a taille for the gendarmerie there stirred up a rebellion. In western France, the duchy of Vendôme, erected as late as 1515 to detach it from dependence on the duchy of Anjou, was held as an apanage under rather closer royal supervision. In the north, the complex of lands administered from La Fère-sur-Oise and centring the county of Marle was held directly of the king or of the Habsburg ruler of the Netherlands, rendering the family, to some, unreliable. Practical power stemmed from the holding of the governorships of Picardy and of Guyenne by the Bourbons and Henri d'Albret.

Other independent territories persisted, such as the vicomté of Turenne, where the vicomte (of the La Tour d'Auvergne family) ruled with regalian rights until the eighteenth century, could raise taxes, coin money, make war and render justice as a limited monarch in conjunction with very active local estates.

David Potter - A History of France, 1460-1560- The Emergence of a Nation State

#xv#xvi#david potter#a history of france 1460 1560: the emergence of a nation state#louis xi#louis xii#charles iii de bourbon#mathieu de foix#jean v d'armagnac#françois i#charles iv d'alençon#marguerite d'angoulême#rené d'anjou#charles viii#charles ix#élisabeth d'autriche#louise de bourbon#gilbert de montpensier#catherine de medici#house of la tour d'auvergne#charles de valois#louis xiii#anne de bretagne#jeanne de france#claude de france#charles iv d'anjou#louise de savoie#house of guise#capetian house of bourbon#antoine de bourbon

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755-1842) Portrait de la princesse Radziwill (Aniela Czartoryska, née Radziwiłł), 1801 Musée des beaux-arts de la ville de Paris

#Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun#french#france#french art#Portrait de la princesse Radziwill#princess#princesse Radziwill#1800s#aristocrat#aristocracy#noble#royal#royality#nobility#art#fine art#european art#brunette#woman#classical art#europe#european#oil painting#fine arts#mediterranean#europa

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

eucanthos

Frans Pourbus the Younger: Élisabeth of France, ca. 1615

Jean-Baptiste Marc Bourgery anatomy table

François Gérard Portrait de Juliette Récamier [arm]

Alexandra Von Fuerst photography [snake]

Flower Fairies I / 1, 2020 by Kathrin Linkersdorff

Fly from Portrait of a Woman of the Hofer Family 1470

Nose shaping tool 1944 US add

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Collaborative Masterpost on Saint-Just

Primary Sources

Oeuvres complètes available online: Volume 1 and Volume 2

A few speeches

L'esprit de la révolution et de la constitution de la France (1791)

Transcription of the Fragments sur les institutions républicaines (1800) kept at the BNF by Pierre Palpant

Alain Liénard's edition and transcription of his works in Théorie politique (1976)

Some letters kept in Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint-Just, Payan, etc. (1828)

Fragment autographe des Institutions républicaines

Une lettre autographe signée de Saint-Just, L. B. Guyton et Gillet (not his writing but still interesting)

Two files at the BNF with his writing (and other strange random stuff):

Notes et fragments autographes - NAF 24136

Fragments de manuscrits autographes, avec pièces annexes provenant de Bertrand Barère, de V. Expert et d'H. Carnot - NAF 24158

Albert Soboul's transcription of the Institutions républicaines + explanation of what's in these files at the BNF

Anne Quenneday's philological note on the manuscript by Saint Just, wrongly entitled De la Nature (NAF 12947)

Masterpost (inventory, anecdotes, etc.) - by obscurehistoricalinterests

Chronology

Chronology from Bernard Vinot's biography

Testimonies

Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas on Saint-Just, as reported by David d'Angers - by frevandrest and robespapier

Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas corrects Alphonse de Lamartine’s Histoire des girondins (1847) - by anotherhumaninthisworld

Many testimonies by contemporaries (in French) on antoine-saint-just.fr

Representations

Everything Wrong with Saint-Just's Introductory Scene in La Révolution française (1989) - by frevandrest

On Saint-Just's strange representation of "throwing tantrums" - by saintjustitude and frevandrest

Saint-Just as "goth/emo boy"? - by needsmoreresearch, frevandrest and sieclesetcieux

Recommended Articles

Bernard Vinot:

"La révolution au village, avec Saint-Just, d'après le registre des délibérations communales de Blérancourt", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, No. 335, Janvier-Mars 2004, p. 97-110

Alexis Philonenko:

"Réflexions sur Saint-Just et l'existence légendaire", Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale, 77e Année, No. 3, Juillet-Septembre 1972, p. 339-355

Miguel Abensour:

"Saint-Just, Les paradoxes de l'héroïsme révolutionnaire", Esprit, No. 147 (2), Février 1989, p. 60-81

"Saint-Just and the Problem of Heroism in the French Revolution", Social Research, Vol. 56, No. 1, "The French Revolution and the Birth of Modernity", Spring 1989, p. 187-211

"La philosophie politique de Saint-Just: Problématique et cadres sociaux". Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 38e Année, No. 183, Janvier-Mars 1966, p. 1-32. (première partie)

"La philosophie politique de Saint-Just: Problématique et cadres sociaux", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 38e Année, No. 185, Juillet-Septembre 1966, p. 341-358 (suite et fin)

Louise Ampilova-Tuil, Catherine Gosselin et Anne Quennedey:

"La bibliothèque de Saint-Just: catalogue et essai d'interprétation critique", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, No. 379, Janvier-mars 2015, p. 203-222

Jean-Pierre Gross:

"Saint-Just en mission. La naissance d'un mythe", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, Année 1968, no. 191 p. 27-59

Marie-Christine Bacquès:

"Le double mythe de Saint-Just à travers ses mises en scène", Siècles, no. 23, 2006, p. 9-30

Marisa Linton:

"The man of virtue: the role of antiquity in the political trajectory of L. A. Saint-Just", French History, Volume 24, Issue 3, September 2010, p. 393–419

Misc

Saint-Just in Five Sentences - by sieclesetcieux

On Saint-Just's Personality: An Introduction - by sieclesetcieux

Pictures of Saint-Just's former school, with the original gate - by obscurehistoricalinterests

Saint-Just vs Desmoulins (the letter to d'Aubigny and other details) - by frevandrest

Saint-Just's sisters - by frevandrest

On Thérèse Gellé and Henriette Le Bas - by frevandrest

Saint-Just and Gellé being godparents - by frevandrest and robespapier

On Saint-Just "stealing" and running away to Paris and the correction house - by frevandrest and sieclesetcieux

How was/is Saint-Just pronounced - Additional commentary in French by Anne Quenneday

#saint-just#antoine saint just#saint just#to be updated#masterpost#refs#sources#frev sources#testimonials and commentaries

128 notes

·

View notes