#wilmer mclean

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Wilmer McLean is one of the funniest and unluckiest historical figures to me because his house got fucked up by a cannonball during the first major battle of the American Civil War, and so he moved to a completely different city to be safe from the war, but 4 years later, the very last battle of the war occurred in and his house was commandeered by the Union army as a place that Lee could formally surrender, after which the army just stole all his shit.

"The war began in my front yard and ended in my front parlor."

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

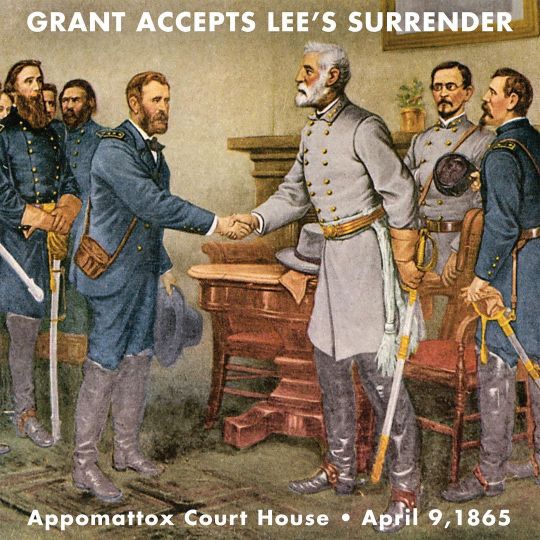

Newspapers brought the story of Appomattox into people’s homes, using descriptive language that set the scene and gave special attention to the attire of both men. “Gen. [Robert E.] Lee was sitting by the table, dressed in a suit of gray—coat, pants, and vest all of gray,” wearing “an elegant sword,” while Ulysses S. Grant had “left his sword behind,” appearing “in the same suit he had worn in the field through the eventful days—a plain blue frock, with double row of buttons, and shoulder straps bearing the three silver stars—the insignia of his rank as Lieut. General.” The vivid description of these men at this momentous event confirmed the popular opinion of them: Lee was a southern gentleman, and Grant was a no-nonsense soldier. It should come as no surprise. . . that the uniforms. . . were important details in the recounting of the surrender of Lee’s army. Although no photographer documented the exact moment of this historic event, engravings and portraits of the scene in Wilmer McLean’s parlor remain popular to the present, as has the appearance of these two generals. The contrast between the uniforms worn by Lee and Grant has become shorthand for each man’s character, a thumbnail sketch of two sides of the conflict. We know the story of what they wore that day better than we know the story of what they said.

The Fabric of Civil War Society, by Shae Smith Cox

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐋𝐞𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐚𝐧 𝐀𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐧

On April 8, 1865, General Ulysses S. Grant was having a hard night.

His army had been harrying Confederate General Robert E. Lee's for days, and Grant knew it was only a question of time before Lee had to surrender. The people in the Virginia countryside were starving, and Lee's army was melting away. Just that morning a Confederate colonel had thrown himself on Grant's mercy after realizing that he was the only man in his entire regiment who had not already abandoned the cause. But while Grant had twice asked Lee to surrender, Lee still insisted his men could fight on.

So, on the night of April 8, Grant retired to bed in a Virginia farmhouse, dirty, tired, and miserable with a migraine. He spent the night "bathing my feet in hot water and mustard, and putting mustard plasters on my wrists and the back part of my neck, hoping to be cured by morning." It didn't work. When morning came, Grant pulled on his clothes from the day before and rode out to the head of his column with his head throbbing.

As he rode, an escort arrived with a note from Lee requesting an interview for the purpose of surrendering his Army of Northern Virginia. "When the officer reached me I was still suffering with the sick headache," Grant recalled, "but the instant I saw the contents of the note I was cured."

The two men met in the home of Wilmer McLean in the village of Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Lee had dressed grandly for the occasion in a brand new general's uniform carrying a dress sword; Grant wore simply the "rough garb" of a private with the shoulder straps of a lieutenant general.

But the images of the wealthy, noble South and the humble North hid a very different reality. As soon as the papers were signed, Lee told Grant his men were starving and asked if the Union general could provide the Confederates with rations. Grant didn't hesitate. "Certainly," he responded, before asking how many men needed food. He took Lee's answer—"about twenty-five thousand"—in stride, telling the general that "he could have...all the provisions wanted."

By spring 1865, the Confederates who had ridden off to war four years before boasting that their wealthy aristocrats would beat the North's moneygrubbing shopkeepers in a single battle were broken and starving, while, backed by a booming industrial economy, the Union army could provide rations for twenty-five thousand men on a moment's notice.

The Civil War was won not by the dashing sons of wealthy planters, but by men like Grant, who dragged himself out of his blankets and pulled a dirty soldier's uniform over his pounding head on an April morning because he knew he had to get up and get to work.

—

𝐀𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐥 𝟖, 𝟐𝟎𝟐𝟑

𝐇𝐄𝐀𝐓𝐇𝐄𝐑 𝐂𝐎𝐗 𝐑𝐈𝐂𝐇𝐀𝐑𝐃𝐒𝐎𝐍

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wilmer McLean was a grocer in Virginia in the 1860s, where his home in rural Manassas was right in the middle of the First Battle of Bull Run, one of the first armed conflicts of the War. So, to try and keep out of the way of the war, he moved to Appamattox, Virginia, coincidentally the site of the last battle of the War four years, and his new house was commandeered by the military as the place where Lee would formally surrender to Grant, ending the War.

1 note

·

View note

Text

April History

April 9, 1865 - After over 500,000 American deaths, the Civil War effectively ended as General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant in the village of Appomattox Court House. The surrender occurred in the home of Wilmer McLean. Terms of the surrender, written by General Grant, allowed Confederates to keep their horses and return home. Officers were allowed to keep their swords and side arms.

April 9, 1866 - Despite a veto by President Andrew Johnson, the Civil Rights Bill of 1866 was passed by Congress granting blacks the rights and privileges of U.S. citizenship.

Birthday - African American actor and singer Paul Robeson (1898-1976) was born in Princeton, New Jersey. Best known for his performance in The Emperor Jones, he also enjoyed a long run on Broadway in Shakespeare's Othello. In 1950, amid ongoing anti-Communist hysteria, Robeson was denied a U.S. passport after refusing to sign an affidavit on whether he had ever been a member of the Communist Party.

0 notes

Text

The Battle of Appomattox Court House, fought in Appomattox County, Virginia, on the morning of April 9, 1865, was one of the last battles of the American Civil War. It was the final engagement of Confederate General in Chief, Robert E. Lee, and his Army of Northern Virginia before it surrendered to the Union Army of the Potomac under the Commanding General of the US, Ulysses S. Grant.

He, having abandoned the Confederate capital of Richmond, after the nine-and-a-half-month Siege of Petersburg and Richmond, retreated west, hoping to join his army with the remaining Confederate forces in North Carolina, the Army of Tennessee under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston. Union infantry and cavalry forces under Gen. Philip Sheridan pursued and cut off the Confederates’ retreat at the central Virginia village of Appomattox Court House. Lee launched a last-ditch attack to break through the Union forces to his front, assuming the Union force consisted entirely of lightly armed cavalry. When he realized that the cavalry was now backed up by two corps of federal infantry, he had no choice but to surrender with his further avenue of retreat and escape now cut off.

The signing of the surrender documents occurred in the parlor of the house owned by Wilmer McLean on the afternoon of April 9. On April 12, a formal ceremony of the parade and the stacking of arms led by Southern Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon to federal Brig. Gen. Joshua Chamberlain of Maine marked the disbandment of the Army of Northern Virginia with the parole of its nearly 28,000 remaining officers and men, free to return home without their major weapons but enabling men to take their horses and officers to retain their sidearms, and effectively ending the war in Virginia.

This event triggered a series of subsequent surrenders across the South, in North Carolina, Alabama, and finally Shreveport, for the Trans-Mississippi Theater in the West by June, signaling the end of the four-year-long war. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

1 note

·

View note

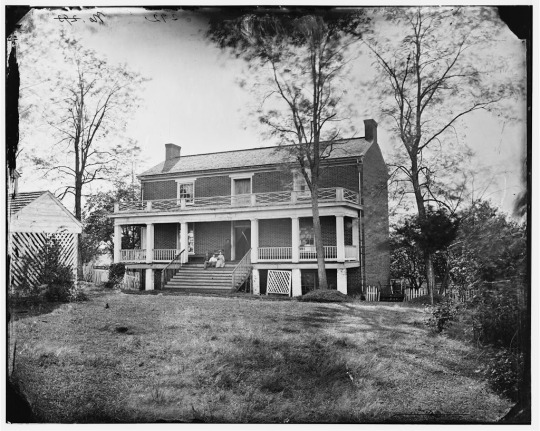

Photo

Wilmer McLean said the Civil War started in his front yard and ended in his front parlor. The Virginia grocer was living in Manassas in 1861 when the first Battle of Bull Run began and dropped a cannonball into his fireplace. He moved to Appomattox and, four years later, Lee surrendered to Grant in his parlor. Spectators carried off most of his furniture and other possessions as souvenirs.

#civil war#wilmer mclean#virginia#battle of bull run#military history#u.s. history#appomattox#robert e. lee#ulysses s grant

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just finished my history class work for today and learned about a funny man from the Civil War that I pity.

His name was Wilmer McLean. He was a man from the south who was originally broke, but he married a rich woman. He had a lovely plantation with a lovely river going through it called Bull Run. This was later the site of the first major battle of the American Civil War.

McLean left with his family to Virginia, to a little hamlet called Appomattox Courthouse. He thought the war would never find him there, but it did. One day, Union soldiers waltzed in and asked if they could have a meeting there. McLean tried to point them to another building, but it was too run down.

So McLean had to let the Union have their meeting with Robert E. Lee in his house. This was where Robert E. Lee surrendered, ending the war. The soldiers tore the house apart, grabbing whatever they could as souvenirs. McLean had to put the property up for sale a year later, but no one wanted to buy it. So he moved back to Yorkshire where this all began. The only things he gained were the bragging rights of "The war started in my yard and ended in my front parlor!"

1 note

·

View note

Text

So the story of Wilmer and Virginia McLean and the Battle of Appomattox Court House is.... an adventure.

So Wilmer McLean was a moderately successful Alexandria businessman, who was always looking for ways to move up in the world. The best way he could see fit to do this was to marry a Southern Socialite, which he found in a young widow named Virginia Hooe Mason.

What Wilmer did not bargain for was the fact that Virginia knew exactly what he was after, so days before the wedding she issued a legal ultimatum: She’d marry him, but she keeps all the rights to her property. All her money is hers, all her land is hers, and upon her death, everything she owns goes straight to her daughters instead.

She essentially gave him a pre-nup.

And rather than face looking like a total heel to Northern Virginian society as a whole, Wilmer McLean took the deal and married her anyway.

They had two homes, one of his in Alexandria, and her large plantation in a small town called Manassas. And this is a technicality, perhaps, but an important one. The McLean farm at the outbreak of Bull Run belonged to her, not him.

So yes, the Battle of Bull Run breaks out in 1861, and General Beauregard uses her plantation as Headquarters, and pays them rent, so Virginia is getting paid while all this is going on.

But of course, Manassas is now a war zone, and Alexandria is Union occupied. So Wilmer and the family are now in a difficult spot. But... there’s a silver lining too. Because for a moderately successful businessman who does NOT have access to his wife’s funds without her permission, a war could be the best thing in the world for him.

His brother owned a sugar plantation down in the Caribbean, and Wilmer helped to smuggle the sugar through the blockade and sell it to the Confederate Army/pro-Confederate locals. He made an absolute fortune doing this, but since living in Alexandria and being pro-Confederate was becoming increasingly difficult to manage, and the fact that the whole area was the center of fighting, in 1863 the family moved to the small town of Appomattox Court House.

Fast forward two years, and this sleepy town is the center of fighting between the Grant and Lee’s armies, and the McLeans spent the whole battle hiding out and waiting for it to be over. Early on the morning of the 9th, Lee sent a note to Grant offering to meet to discuss terms of surrender, and sent out Charles Marshall to find a suitable place to hold the meeting. Marshall stumbled onto the town itself, and noticed Wilmer McLean looking around trying to figure out what the fuck was going on.

Marshall walked over to him, explained the situation, and asked if there was a place for the generals to meet. McLean immediately offered an abandoned building, but when Marshall went inside he was disgusted, and McLean reluctantly offered his house up instead.

Not long after, Lee arrived and went into the sitting room to wait. Grant and his staff showed up around 1:00, and the meeting officially began. This resulted in the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia and the parole of over 28,000 Confederate soldiers. And McLean losing every single thing in the room the surrender took place in, as the Union officers bought or stole everything in sight- even his daughter’s doll.

The next day, Wilmer ran into the husband of his wife’s niece- Edward Porter Alexander, and tore him a new one about everything that was going on, and complaining about how the war started in his front yard and ended in his living room. Which isn’t completely accurate for a lot of reasons, but it makes a hell of a story all the same.

With no reason to live in the middle of nowhere Virginia anymore, not long after this the McLeans moved back to Alexandria, and officially put the war behind them when Grant helped to get McLean a federal job during his administration.

Because of course that happened. Of course.

Source:

The Biography of Wilmer McLean A Stillness at Appomattox The Appomattox NPS Guidebook The Appomattox Campaign The Passing of the Armies Grant’s Memoirs I worked there

#personal post#Appomattox#Appomattox Court House#Wilmer McLean#history#Civil War#American Civil War#Virginia McLean

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

*rolls eyes jokingly*

I know, I know. But he doesn’t have to be so boring about it.

The guys name was Wilmer McLean.

*nods head eagerly and takes a paddle*

I would love to play ping pong with you!

*holds up the paddle at the ready*

*knocking on your front door*

Mary pulled the door to the penthouse open, she looked over to Pietro, her eyes widening a little in surprise. "Oh hello, Pietro!" She greeted with a bright smile. "What brings you by?"

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In retreat from the Union army’s Appomattox campaign, which began in March 1865, the Army of Northern Virginia stumbled westward through the Virginia countryside stripped of food and supplies. At one point, Union cavalry forces under General Philip Sheridan had outrun General Lee’s troops, blocking their retreat and taking approximately 6,000 prisoners at Sayler’s Creek.

Confederate desertions were mounting daily, and by April 8 the Rebels were almost completely surrounded. Nonetheless, early on the morning of April 9, Confederate troops led by Major General John B. Gordon mounted a last-ditch offensive that was initially successful. Soon, however, the Confederates saw that they were hopelessly outnumbered by two corps of Union soldiers who had marched all night to cut off the Confederate advance.

Later that morning, Lee—cut off from all provisions and all support—famously declared that “there is nothing left me to do but to go and see Gen. Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths.” But Lee also knew his remaining troops, numbering about 28,000, would quickly turn to pillaging the countryside in order to survive.

With no remaining options, Lee sent a message to General Ulysses Grant announcing his willingness to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia. The two war-weary generals met in the front parlor of the Wilmer McLean home at one o’clock that afternoon.

Lee and Grant, both of whom held the highest rank in their respective armies, had known each other slightly during the Mexican-American War (1846-48) and began their dialogue by exchanging awkward personal inquiries. Characteristically, Grant had arrived in his mud-splattered field uniform while Lee had turned out in full dress attire, complete with sash and sword.

Lee asked for the terms of surrender, and Grant hurriedly wrote them out. Generously, all officers and men were to be pardoned, and they would be sent home with their private property–most important to the men were the horses, which could be used for a late spring planting. Officers would keep their side arms, and Lee’s starving men would be given Union rations.

Quieting a band that had begun to play in celebration, Grant told his officers, “The war is over. The Rebels are our countrymen again.” Although scattered resistance continued for several weeks—the final skirmish of the Civil War occurred on May 12 and 13 at the Battle of Palmito Ranch near Brownsville, Texas—for all practical purposes the Civil War had come to an end.

#american civil war#ulysses s grant#appomattox#us civil war#civil war#history#acw#happy surrender day folks~~~#side note the building in the 2nd actual photo i believe is the courthouse#which is still there if you go visit today#when i went it was really cool to get a perspective of just how small this little village was

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

April 9, 2022 (Saturday)

On April 9, 1865, General Ulysses S. Grant got out of bed with a migraine. The pain had hit the day before as he rode through the Virginia countryside, where the United States Army had been harrying the Confederacy’s Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee, for days.

Grant knew it was only a question of time before Lee had to surrender. After four years of war, the people in the South were starving, and Lee’s army was melting away as men went home to salvage whatever they could of their farm and family. Just that morning, a Confederate colonel had thrown himself on Grant’s mercy after realizing that he was the only man in his entire regiment who had not already abandoned the cause. But while Grant had twice asked Lee to surrender, Lee continued to insist his men could fight on.

So Grant had gone to bed in a Virginia farmhouse on April 8, dirty, tired, and miserable with a migraine. He spent the night “bathing my feet in hot water and mustard, and putting mustard plasters on my wrists and the back part of my neck, hoping to be cured by morning.” His remedies didn't work. In the morning, Grant pulled on his clothes from the day before and rode out to the head of his column with his head throbbing.

As he rode, an escort arrived with a note from Lee requesting an interview for the purpose of surrendering the Army of Northern Virginia. “When the officer reached me I was still suffering with the sick headache,” Grant recalled, “but the instant I saw the contents of the note I was cured.”

The two men met in the home of Wilmer McLean in the village of Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Lee had dressed grandly for the occasion in a brand new general’s uniform carrying a dress sword; Grant wore simply the “rough garb” of a private with the shoulder straps of a lieutenant general. But the images of the noble South and the humble North hid a very different reality. As soon as the papers were signed, Lee told Grant his men were starving and asked if the Union general could provide the Confederates with rations. Grant didn’t hesitate. “Certainly,” he responded, even before he asked how many men needed food. He took Lee's answer—“about twenty-five thousand"—in stride, telling the general that "he could have... all the provisions wanted."

Four years before, southerners defending their vision of white supremacy had ridden off to war boasting that they would beat the North’s misguided egalitarian levelers in a single battle. By 1865, Confederates were broken and starving, while the United States of America, backed by a booming industrial economy that rested on ordinary women and men of all backgrounds, could provide rations for twenty-five thousand extra men on a moment’s notice.

The Civil War was won not by the dashing sons of wealthy planters, but by people like Grant, who dragged himself out of his blankets and pulled a dirty soldier's uniform over his pounding head on an April morning because he knew he had to get up and get to work.

THEY WERE TRAITORS THEN AND ANY COMMEMORATION OF CONFEDERATE ANYTHING IS TREASON NOW!

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day in 1865 Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant, effectively ending the Civil War. Heather Cox Richardson writes: “The two men met in the home of Wilmer McLean in the village of Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Lee had dressed grandly for the occasion in a brand new general's uniform carrying a dress sword; Grant wore simply the "rough garb" of a private with the shoulder straps of a Lieutenant General. But the images of the noble South and the humble North hid a very different reality. As soon as the papers were signed, Lee told Grant his men were starving, and asked if the Union general could provide the Confederates with rations. Grant didn't hesitate. "Certainly," he responded, before asking how many men needed food. He took Lee's answer-- "about twenty-five thousand"-- in stride, telling the general that "he could have... all the provisions wanted." https://www.instagram.com/p/CNdBqn3Dr7O/?igshid=vtvxo922azml

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Appomattox - Part 2

Part 1

The thundering of artillery ceased. Birds began to chirp as Alfred strode into the small village, his general walking beside him. Just earlier that morning, Grant had been plagued with a debilitating migraine. But upon receiving the first of Lee’s correspondence for negotiations, his health had greatly improved.

They were to meet at the home of Wilmer McLean, a man who had moved out this far to avoid the noise and turmoil of war. In a way, it was oddly fitting that a surrender would occur here. He could escape the war permanently.

The two generals couldn’t be any more different. Despite the Confederates having borne the brunt of the losses, Lee stood in his finest ceremonial whites while Grant wore his mud-stained sack-coat and trousers. While his general didn’t carry in his side arm, Alfred kept his hand close to his own. Not that he really expected anything to happen. These were gentlemen.

The house was comfortable. Two floors and a wide porch, upon which Lee stood, resting a hand against a pillar. An aide stood nearby, and Alfred spotted a few more aides and officers for both sides milling about the premises, keeping as close a watch on each other as the surrounding land. But there was one person that Alfred didn’t see. Perhaps he was mistaken. Perhaps she was inside already, preparing the ink and paper. That would be a fitting task for her, given all the trouble she’s caused! He almost laughed at the thought of it. Striding into that house, seeing her put in her place again. He’d ask her to get him a glass of water, no! A shot of whiskey! Just to see the defeat in her eyes as she knew she really had no choice but to obey. What a delicious image! He could hardly keep the laughter back behind his teeth as he strode up the steps to meet Lee.

The two old men, however, didn’t share his youthful amusement. They shook hands, speaking in low voices, too low for Alfred’s distracted mind to pay any attention to. He had a rebel to torment! He pushed open the door, looking around the home.

Inside, he did indeed find a woman. But it was not the one he expected. She looked older, perhaps in her late-thirties, and determinedly hostile. She glared at Alfred as he entered the house, her arms crossed. “I told that damn general I didn’t want any enlisted in my house! You turn tail right now!”

Alfred took a step back, surprised, his hands raised. “I’m one of General Grant’s aides, ma’am.” Before she had an opportunity to berate him again, he quickly backed out toward the porch, still looking into the various visible rooms for his target. “Did Lee bring a girl here with him? A Miss Caitlyn Montgomery?”

“The last thing I need in this house is a camp-following whore!” She barked, advancing on Alfred with a wooden spoon in hand. If this woman had been chosen to defend the entirety of the South, Alfred thought, Cait might have stood a chance. He felt some strange heat rise in his chest at the word she used to describe his adversary. Anger? No, that didn’t make any sense. Why would he be angry about the insult? He should be laughing! Something was wrong.

Safely back on the porch, he rejoined the generals, who were now beginning to meander toward the interior of the home. During a brief lull in their conversation on their previous encounter during the war against Mexico, Alfred cleared his throat. “General Lee, where is Miss Montgomery? My latest reports say she is still with your army as of yesterday.”

The generals stopped, both staring at Alfred as if he had asked why the sun had not yet set at mid-day. And there was something else - an uncommon darkness in Lee’s expression, a drawing down of his lips that deepened the wrinkles around his eyes. “Oh… my poor boy. No one told you?” He finally spoke, reaching out to place a hand on Alfred’s shoulder, unsuccessful as Alfred jerked back, panic rising.

“Jones,” Grant began, then lowered his voice as he looked around, “she isn’t coming. She died this morning.” The words made sense separately, but together? “I’m sorry.”

The earlier laughter bubbled up again, a strange mirth releasing itself from his chest. “South? Dead? Perhaps for a moment, or even a day at most. Our kind don’t die!” He took another step back from the men, looking around for a horse. “I’ll just go find her. She probably got lost on her way here. She’s very stupid, after all. The stupidest girl I know!” His boots thudded against the wood of the porch, his breath freezing in his lungs as he fell, the steps below him giving way to hard earth. A grey-uniformed man caught him, just moments before he would have tumbled onto the road below. Still, that incessant laughter followed. “I’ll find her! I’ll bring her here!” He promised, his heart pounding in his chest. “Don’t start without me, General! I’ll be back in under an hour!”

#drabble#sometimes you just write things because you want to express something that's been in your head for months#but you know your writing ability doesn't do the scene justice#so you're stuck between writing something mediocre and not writing at all#so you write the mediocre thing and move on with your life#and that's valid

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

History

April 9, 1865 - After over 500,000 American deaths, the Civil War effectively ended as General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant in the village of Appomattox Court House. The surrender occurred in the home of Wilmer McLean. Terms of the surrender, written by General Grant, allowed Confederates to keep their horses and return home. Officers were allowed to keep their swords and side arms.

April 9, 1866 - Despite a veto by President Andrew Johnson, the Civil Rights Bill of 1866 was passed by Congress granting blacks the rights and privileges of U.S. citizenship.

Birthday - African American actor and singer Paul Robeson (1898-1976) was born in Princeton, New Jersey. Best known for his performance in The Emperor Jones, he also enjoyed a long run on Broadway in Shakespeare's Othello. In 1950, amid ongoing anti-Communist hysteria, Robeson was denied a U.S. passport after refusing to sign an affidavit on whether he had ever been a member of the Communist Party.

0 notes

Link

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

April 8, 2021 Heather Cox Richardson

On April 8, 1865, General Ulysses S. Grant was having a hard night. His army had been harrying Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s for days, and Grant knew it was only a question of time before Lee had to surrender. The people in the Virginia countryside were starving and Lee’s army was melting away. Just that morning, a Confederate colonel had thrown himself on Grant’s mercy after realizing that he was the only man in his entire regiment who had not already abandoned the cause. But while Grant had twice asked Lee to surrender, Lee still insisted his men could fight on.

So, on the night of April 8, Grant retired to bed in a Virginia farmhouse, dirty, tired, and miserable with a migraine. He spent the night “bathing my feet in hot water and mustard, and putting mustard plasters on my wrists and the back part of my neck, hoping to be cured by morning.” It didn’t work. When morning came, Grant pulled on his clothes from the day before and rode out to the head of his column with his head throbbing.

As he rode, an escort arrived with a note from Lee requesting an interview for the purpose of surrendering his Army of Northern Virginia. “When the officer reached me I was still suffering with the sick headache,” Grant recalled, “but the instant I saw the contents of the note I was cured.”

The two men met in the home of Wilmer McLean in the village of Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Lee had dressed grandly for the occasion in a brand new general’s uniform carrying a dress sword; Grant wore simply the “rough garb” of a private with the shoulder straps of a Lieutenant General.

But the images of the noble South and the humble North hid a very different reality. As soon as the papers were signed, Lee told Grant his men were starving, and asked if the Union general could provide the Confederates with rations. Grant didn’t hesitate. “Certainly,” he responded, before asking how many men needed food. He took Lee’s answer– “about twenty-five thousand”– in stride, telling the general that “he could have… all the provisions wanted.” By spring 1865, Confederates, who had ridden off to war four years before boasting that they would beat the North’s money-grubbing shopkeepers in a single battle were broken and starving, while, backed by a booming industrial economy, the Union army could provide rations for twenty-five thousand men on a moment’s notice.

The Civil War was won not by the dashing sons of wealthy planters, but by men like Grant, who dragged himself out of his blankets and pulled a dirty soldier’s uniform over his pounding head on an April morning because he knew he had to get up and get to work.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

Heather Cox Richardson

1 note

·

View note