#weston richmond

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Rain City Drive // Concrete Closure

#rain city drive#concrete closure#things are different now#matt mcandrew#zachary baker#felipe sanchez#weston richmond#colin vieira#bands#lyrics#dayseeker#bad omens#spiritbox#point north#beartooth#the ghost inside#against the current

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mafioso

__

Warnings: Murder, manipulation, drugs and violence

Terry Richmond X OC!Marina

__

__

The collective clink of champagne glasses filled the large venue as self-made millionaire and philanthropist Terry Richmond concluded his speech at the second annual charity event for Black women and children. Thunderous claps and cheers bounced off the walls as he exited the stage and came down to thank each and every single person that had come out to support and donate to the amazing cause. He was elated and proud of the turnout; truly grateful.

At 43 Terry felt at the height of his career. The comings and goings of life reflected well on his face and he carried all those trials and triumphs with him on his sleeve next to his heart. His story was a story of the people.

The night was a huge success. A large volume of high profile people had pledged and donated to this cause right along with him. Close family and friends came out in support and he circled around the room checking in on them and taking breaks to hit a shimmy or two on the dance floor.

He had also allowed some of his favorite black journalists and reporters to give interviews, but he was most interested in one in particular that had been very vocal and fierce about the safety of black children in spaces that society deemed not fit for them. How many times had a black child been harmed or put in a traumatic situation due to racism? Far too many times to count and they deserved a space to perfect their crafts without fear or judgement.

Marina Evans was a woman of poise, integrity, and culture, and at 25 she was at the top of her game. Not many could deny her journalistic credentials. She was the first person he wanted to give an interview to tonight and he sought her out quickly through the sea of people. The bold black gown had been a wondrous choice against her bronzed skin. Honey blond braids highlighting the warm undertones of her skin and dark expressive eyes styled with a natural set of wispy lashes. She was a show stopper. A true beauty.

She had just ended an interview with Weston Troy, a filthy rich middle aged man that owned a few hospitals in the area. Her eyes drifted over to him and she began to set up for his interview. A warm welcoming smile graced her face and he made sure to return it. Cameras and microphone ready, Terry adjusted his black suit and freed his mind.

“Tonight I am here speaking with local philanthropist and founder of ‘Hearts of Grace’ a charity founded to give aid and relief to underprivileged families…and without further ado I’d like to welcome Mr. Terry Richmond. How are you feeling about the turnout tonight… did you project the earnings for year two to surpass year one by so much?”

“ I’m feeling amazing tonight, the turnout was more than I could have ever imagined. When I initially started this charity I had no idea that anyone would ever give money to the cause at such a high volume, it's too often that things within the affiliation of the black community are not taken seriously or into consideration… I would like to change that, and with all the resources at my hand I'd be foolish not to invest it into people who look like me and sound like me.”

“I love that, what you did here tonight was jaw dropping. The kind of things I want to see more of, what does it mean for you to give back and support black families,businesses, and neighborhoods?” He pondered a bit before answering and pulled his lip from his teeth.

“It means that I have an opportunity to cater to and serve these underprivileged families, I too come from very humble beginnings. I grew up in a single parent household, it was just me and my mother so sharing this wealth with many people is top priority.”

“Terry, that is just amazing, I’m excited for more people to hear your story… for you it's been a long time coming, but for many of us this is our first time seeing someone who we relate to so much do as many great things as you have…and that brings me to my next question. How does being a role model to the younger generation speak to you?” Her questions were definitely living up to her reputation, she asked the real shit and he paused to gather his words, this was a passionate subject for him so finding the right words was essential.

“Being a role model for the younger generation entails a particular type of character and finesse… I want them to know that yes hard work and dedication can afford you the luxuries of life, but I also want them to understand that mental health is just as important um..if not more important than any career field or industry they choose.”

“I also saw that you named your charity after your mother Grace, how does it feel tonight to share this with her… I’m sure she is so proud of you.”

“My mother means the world to me…for any time I was ever in trouble or needed her she picked up the phone, she lifted me up, and she molded me into the man I am today. I don’t care how old I get or how many things I achieve, I'll always be her baby.”

“It was such a pleasure to interview you tonight, I thank you so much for taking the time out of your busy schedule to allow me to talk and pick your brain.” Marina had interviewed many men and women of different backgrounds and profiles, but none had ever struck her as truly genuine people quite as he did. He truly meant those words.

“Oh no anytime..you’ve had the best questions I thank you for that. And when I’m ready for another interview I know how to find you, thank you for coming out tonight Ms.Evans I truly appreciate it.” Terry left it plainly at that. He didn’t wanna seem weird by telling the young girl that he was an avid viewer of her podcast and hadn’t missed any episodes thus far.

The night carried on and people filled their bellies to the brim with liquor and a catered banquet of savory mouth watering food. Terry was on his second plate of food and had been cackling loudly in his mothers ear, all tipsy and giggly from the constant glasses of champagne.

“Boy you are just tickled to death ain’t you, what’s so funny son?” He rested his head onto her shoulder and squeezed her into a warm hug.

“I’m just happy ma..that’s it. Tonight turned out amazing and I get to honor you right along with it..I hope you’re proud.”

“Son is proud even the word for what I feel? You make me ecstatic, I hoped and prayed for so many long nights for you to have something…anything to call your own, and look at you now.” Grace pressed a kiss to her son's forehead before standing from her seat.

“Walk your mama to her car, I’m going to turn in for the night.”

Terry walked his mother to her car and watched her disappear into the distance before he walked back into the building. Standing with his hands in the pockets of his smooth slacks, he surveyed the area with calm eyes. He was looking for someone. Ahh there she is. Honey blond braids swaying gently behind her as she rocked in her chair to the music. Headed in her direction he grabbed a freshly poured glass of champagne from the table and handled the delicate glass in his hands carefully.

Cognac eyes met his as he finally made it into her line of vision. “Champagne? I wasn’t aware you were still here Ms.Evans.” Her pretty manicured hand accepted the drink from him and she sipped a little before answering him.

“Yeah I guess I’m a bit of a recluse…I prefer to fade into the background at events like these. Sometimes it’s better to just watch.” Terry hummed in his throat before taking a seat in front of her crossing his left leg over his right.

“And on that point we do agree…for causes such as these I can show up no questions asked, otherwise I’m home nose deep in a good podcast.” His deep rumbling laugh coaxed a cute chuckle from her mouth.

She sipped a little more of the sweet champagne before she answered him. ”Oh wow me too , so you have a favorite one you listen too?”

“Yes…yours. It’s the only one I can sit through and enjoy without a missed episode. You’re great at what you do Ms.Evans…very captivating topics.” Terry watched a hand press to her chest in shock as her mouth fell in shock.

“You watch lil ole’ me, wow Terry I really appreciate that. And I try to make things interesting as well as informative… I'm happy it reaches you well.”

“There’s nothing little about the work you do, remember that.” Maria shyly tilted her head to the side, peeking up into his face from under her lashes.

”Thank you so much Terry, you have the kindest eyes by the way…sorry if that was weird.” He dropped his head and let his eyes lock onto hers and watched her skin heat up under his gaze.

“No no, not weird at all. I receive that..thank you beautiful.”

Terry enjoyed picking her head for the reminder of their time together. By 9pm the event had wrapped and everyone filed out of the large double doors to head home. Terrys large hand graced the small of her back not wanting to lose her in the crowd of people, he hated that their time was cut short because he had really enjoyed chatting with the smart woman.

“Did you drive here?” He looked down at her once they’d made it outside, the middle of people around them creating the perfect bubble for tj to talk.

“Mhmh I did.. I’m right over there, the black Acura.” Her dainty finger pointed at the sleek Acura suv that was coincidentally parallel parked behind his Manhattan Green BMW X6.

“ I’ll walk you..we’re parked right by each other.” Her heels clicked against the dark asphalt and she let a yawn escape her pretty lips.

“Tired Ms.Evans? Sorry to keep you so late, I’m sure you have other obligations.”

“Mhm it’s all the food and champagne getting to me, and no please don’t apologize I had such a nice time tonight… thank you again for extending an invitation to me.” The two stopped in front of her suv and it had Terry wishing he could turn back time.

“And miss an opportunity to talk to the gorgeous and seriously intelligent Marina Evans… not a chance. Thank you for your support, and drive safe.” He helped her step into her vehicle before he closed her door and watched her leave before pulling out his phone to make a call.

“Yeah she just left..keep close to the plan and do exactly what I told y’all to do. I find out you niggas did anything other than what I asked…yall are finished.” He hung up the phone and hopped into his car heading to his house. He knew what he was doing was fucked up, but rarely did Terry ever not get what he wanted. Only this time he wanted Marina Evans and he was willing to stage whatever freak incident he could think of to appear as the white shining knight in her story.

The contemporary home was a perfect mix of neutral earth times and dark greys. Features within the home had donned it with eco friendly and smart house features putting it at a price point of a whopping 1.2 million dollars. A price point Terry would pay and then some for a house that was exclusive to him. The story he told the public about his upbringing was slightly altered and fabricated. The money was only halfway clean, but his appearance needed to be crystal. No past offenses or charges, no run-ins with the police, and no witnesses.

He put people in the dirt for a living and that was just the true facts. The true underground king with an empire spanning throughout the states.A dr. Jekyll and Hyde if you will. The boogeyman. An assassin with the precision to kil. Right now his cousins were ransacking the cute little craftsman style house that belonged to Marina Evans. A sick way of pushing her into his arms he knew but having her would make it all worth the risk.

A new obsession had squirmed its way into Terrys head one night during a masturbation session. The video practically screamed out at him and he had nutted enough that night to fill the Mississippi River; twice,his eyes were glued to the computer screen as he watched the younger woman be pumped full of grown mature dick. The idea had crossed his mind plenty of times, something young and hot to trick on and fuck whenever he wanted to. It seemed maybe he’d be getting his wish sooner or later.

__

Paranoia and fear gripped Marina in the coming days after the charity ball. When she had made it home and into her driveway that night she knew something was off. The linen curtains that lined her French doors to her kitchen blew in the night winds, signaling the doors had been smashed. Eyes wide with fear and shock she held her hand over her mouth in disbelief. She frantically dialed 911 to report a burglary. Her house was a mess, picture frames broken and everything rummaged through. The following nights she spent in the guest room at her moms house, too afraid to sleep in her own house.

She had called into the local newspaper that she worked for letting them know of her unfortunate situation. Work would have to be put on the back burner for a few days right along with her podcast episode. She was still practically new to this neighborhood having only just closed on her home two months prior. It was a quiet safe neighborhood, and all her neighbors had kindly welcomed her into it. But now she wasn’t so sure about it being safe. What if she had been home When this happened, would she have lived to tell the tale?

She felt hopeless and the police had no leads yet. What was life without a curveball? She was currently wrapped up in her mothers guest room

sick with the flu. Coughs and sniffles were the soundtrack of life right now and the pungent smell of Lysol was in the air. She had no appetite and a slight migraine sat at her temples, and yet her phone began to ring excessively loud into her ear.

|“Hello?” She was sure she sounded as stuffy as she looked.

|”Marina..hey sweetheart it’s Terry. I called as soon as I heard the bad news, I’m so sorry.” His deep voice sounded apologetic over the phone and she had almost forgotten the exchanging of numbers almost a week ago at the charity event.

[-My uncle works at the police department..he mentioned your name and burglary in the same sentence and I just had to call and check in on you. I hope I’m not overstepping.

[-No not at all I appreciate you calling me..um yeah it hasn't been the best week for me so far it’d be better if I could find out who did this to my house…and now I’m sick with the flu.She heard shuffling and muffled talking on his end and she sat up further on the headboard of the bed.

[-Let me send you something Marina, a little get well soon basket…if that’s okay with you I can have my assistant drop it to you. Marina pondered a bit, and honestly what was the harm in accepting it?

[-I don’t know Terry, I couldn’t ask you to do that. One day you'll have to let me repay you back for your kindness.

[-I insist, and pay me back in good health.. and let me take you out some time when you’re feeling better. Some time had lapsed and he had seriously caught her off guard with the question.

[-Marina? You don’t have to give me an answer right now… my ego can handle it, trust me.

[-Sometime when I’m better definitely, I’m completely in the dumps right now..but I could definitely use that basket if it’s still on the table.

[-It is..I’ll get my assistant to contact you and get everything delivered to you. Get well Marina I’ll talk to you soon.

The call ended and she finally felt some strength in her to get up and tend to herself. Her braids had been in her bonnet for the last 48 hours and her face looked drained of all her color. She definitely wasn’t in any shape to look Terry’s handsome ass in his face. Her moms house was quiet, and she knew her mother wouldn’t be home from the hospital until 7 that evening so trying to get better was definitely the plan for the next few hours.

As he said, Terry had his assistant message her about her location to send the basket. It arrived well packaged with an aroma that was clearing her nasal passage. Two dozen crimson red roses and a large woven basket was on the front porch waiting for her in less than an hour. She hurriedly sat it on her mothers dining table and pulled the contents from the basket. Each item she was excited to use. Multiple face masks to bring back the color to her face, an expensive looking full body massager, a cozy pajama set, and a container of chicken noodle soup that was still piping hot from the deli uptown.

“How freaking sweet, now these are gifts worth having for sure.”

She sent a picture over to Terry letting him know that everything was revived with the highest appreciation. He hearted her message but didn’t send back a written reply.

__

“Didn’t I tell you to stay out my fucking city?!” Terry let his bloodied fist fly into the man’s face for a third time, he winced and shook his hand quickly before his phone vibrated in his pocket. A picture from Marina showing him the basket had made it to her and would be used gratefully. But she'd have to wait. Terry was in his mode. The kill a nigga and ask questions later mode, he had two run ins prior to this one with the same pesky ass excuse for a human being.

“Pass me my shit, I’m ending this. Motherfuckers need to know that I don’t speak twice.” The heavy gun was laid in his hand and he screwed on the silencer. The man in front of him cried and begged for his life, but time was out for him.

“Mario Brown…I’m sentencing you to death for not obeying the nigga that owns you.” A quick pull of the trigger put a silver bullet right through his head. His crew needed no words as they immediately rolled the body into a tarp to be burned.

Terry shrugged off his suit using it to wipe the blood from his face and neck. He had a warehouse stacked to the brim with cocaine that needed to make it to El Paso, Texas. Terry wasn’t a cliche in the world of drugs, he chose the mafia life willingly; it didn’t choose him. It was all he knew and it was all he’s ever done outside of his coverups, that consisted of real estate and stocks. All three things he needed to know the ins and outs of to keep up the facade. He was no good person and he was no angel. He maneuvered through this life cunning and forcefully, and yet he did so with grace.

Drugs had afforded him the type of access he wanted in life. A payroll full of law enforcement, cars and houses, and the baddest bitches on the continent. But he was getting older and more irritable with it all, and that was bad for business. A man that stayed irritated was a man bad for business, he had stacked and put so much money away his grandchildren’s grandchildren would be rich. And yet having all he had he still longed for a woman to call his, someone to marry and give his last name and kids too. Marina Evans was what he wanted-no needed, and he would pull out any stop to have her.

His clothes would be a pile of ash by the time he finished using the warehouse shower, black and purple bruises littering his back and side from a recent brawl with a new business partner who would ultimately be his way out. He didn’t believe the old heads that told him he only had one way out of this kinda life, he refused to put that shit on himself. Death was not the only way out, past men just didn’t have his sharp mindset and it showed because they all rested eternally in cemeteries.

His matte black Range Rover practically drove itself home. He was worn out and needed food and sleep. Public speakings to keep the wool over the public’s eye and the night time escapades that always ended in a dead body or two lying around, were getting the best of him. For the next month he planned to pull back from the public slowly but surely, only popping out to speak when absolutely necessary. The only person he cared to be around was her. What a fucking joke. Terry knew better about this situation and still refused to do better, he wanted what he wanted. Marina… Just the sound of her name rolling off his tongue enticed him and his dick had jumped multiple times in his pants when she complimented him at the ball.

A pretty lil thing with a good head on her shoulders and outside of wanting to put her through his mattress he was actually genuinely intrigued by her. And when he finally laid down it was her pictures and voice that invaded his privacy so badly he stalked all her socials. Her vibrant colorful pictures on her Instagram page pulled a smile from him, such an interesting girl.

__

The next morning came to Terry in peace. No nightmares and no tossing and turning, he felt well rested above all else and the pain he felt from his bruised body had subsided and drowned out without painkillers. His morning routine came effortlessly and he ended it all with a 30 minute meditation to thoroughly decompress his body to prepare for his day.

He scarfed down a savory bagel sandwich and washed it down with his herbal tea. His agenda for the day was light as planned, he was to be kept updated on the whereabouts of his drugs every hour on the hour and not a second late. A large sum of money was headed his way if shit went smoothly.

His fingers itched to message Marina; so he did. He wanted another try at seeing her. To his surprise she had responded quickly and said she was feeling well enough to meet at her house. She spoke of wanting to replace the broken glass on her French doors so he dressed casually and responded letting her know he’d see her shortly.

His Ford Raptor rounded the block into a cute quaint neighborhood. Children rode their bikes and sprayed each other with water hoses as their parents watched, and the background noise of barking dogs made it all full circle. He spotted Marina’s suv quickly and pulled in alongside it in her driveway. Getting out he noticed her still sitting inside and tapped on her window lightly.

“Hi Terry… I know I look weird still sitting in here. I’m just scared to go alone.” She gave him a bashful smile and opened her driver side door. Black biker shorts showing off her thick thighs and plush lower half, had him shaking his head. A Tupac graphic tee shirt and white sneakers completed her looks and her neat braids rested atop her head in a tight bun.

“Come on I’ll go with you, nobody will mess with you while I’m here I promise.” She obliged and walked side by side with him to the side of her house where the doors were. Terry measured where the glass was supposed to be and got the measurements for replacements and let the tape measure shoot back into itself before turning to Marina.

“I have a guy that does this kind of work. I'll get in contact with him for you. No cost to you, but for now I’d say invest in security cameras…they’ll bring you a good peace of mind.”

“Will do, that’s not even out of the question anymore… thank you for extending this kind of generosity to me.”

A smirk graced his face as he stared down at her, hands itching to touch her. “Let’s get lunch and you can thank me all you want afterwards.” He helped her up into his truck with a hand on her waist, green eyes going wide at her ass in his face, and on his way around the truck he was silently praying to god.

She was definitely chatty when she got comfortable, but he didn’t mind listening. They filled their bellies with Korean bbq and sushi and Terry was still ordering appetizers.

“Please no more, are you trying to stuff me?” In more ways than one he thought to himself, he just loved watching her eat. When she tried something new amongst the appetizers she hit a little happy dance if she liked it. They had ate their fill in food with plenty to bring home, Terry paid the bill and carried their Togo bags and she kept up beside him sipping quietly on her lychee tea. His phone buzzed in the console a few times and he ignored it knowing it was about his shipment, he would get to it when she was no longer around.

“Do you need to get that… am I intruding or something? You can let me know, I’m sure you’re practically booked and busy. Please don’t let me hold you up.”

“They can wait, you’re more important right now.” She turned slightly in her seat and her cognac eyes held his for what felt like hours. And she leaned closer into his space, holding that eye contact.

“You have the most beautiful eyes… they just seem never ending.” His stare intensified and he watched her smile dreamily at him, whatever effect he thought he had on her had been confirmed.

“You keep complimenting me like that and I’ll start to think you got a little crush on me Ms.Evans.”

“Would that be so bad…me liking you?” He shook his head and tucked a braid back into her bun fingers slowly grazing her neck. How bold of her,

“Only if I didn’t like you back.” He smirked and rubbed his fingers against her open palm watching her fingers twitch slightly. “You’re an amazing woman Marina… I’ve been interested in you for a while, but things just didn’t make sense then.” He thought back to a few months ago when he had initially intended on meeting her but he was busy trying to wipe a whole bloodline out at the time and that was time consuming.

Her eyes danced around his face as she listened to him intently, and his right hand rose to her chin to focus them, letting her lean into him to initiate a kiss. But she put her hands up pulled back slowly.

“But Terry what if-“

“Shh.. put your hands down and let it happen, let me in.”

His hands found her face and he pressed his lips to hers in a rush. Her tongue tasted sweet from her drink and the strawberry flavored lip gloss had him sucking her lips into his mouth like a savage. She gripped his shirt and he pulled her into him with a hand on her waist hand rubbing along her back soothingly, chest to chest heads turning left to right to increase the experience. He pulled away from her reluctantly and brought a hand to his lips to kiss.

“Give me a chance to court you and prove myself…if you don’t like what I offer you, then that’ll be it and I won’t bother you again, but if you do..I have so much to show you.”

“A deal is a deal Mr.Richmond..let the games begin.”

__

A/N: The girls called for Mafia!Terry??? HERE HE GO😗. Like and reblog if you enjoyed this🫶🏾

@venusincleo @grlsbstshot @yassbishimvintage @avoidthings @pocketsizedpanther @writingsbytee @melodichaeuxx-lacritquexx @simplyzeeka @zillasvilla @blowmymbackout @kimuzostar @playgurlxoxo @kumkaniudaku @megamindsecretlair @theereina @keyaho @brattyfics @hotgrlcece @henneseyhoe @starcrossedxwriter @nahimjustfeelingit-writes @uzumaki-rebellion @blackmoonchilee @invisiblegiurl @blackerthings @19jammmy @ovohanna24 @talkswithdesi @notc0rtez @becauseimswagman1 @prettyisasprettydoes1306 @mysteryuz

#terry richmond #aaron pierre #terry richmond x blackoc #rebrl ridge

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

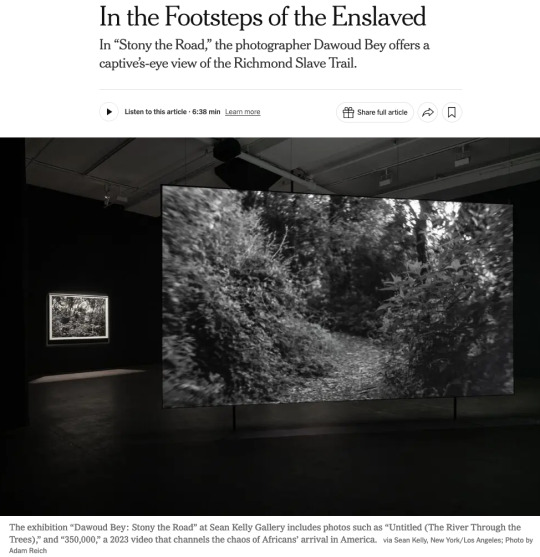

Happy to see my review of Dawoud Bey's great show at Sean Kelly Gallery getting nice play in the New York Times. The full text is below (click on "Keep reading") but one thing I didn't have room to dwell on, as much as I would have liked, is the vitally important tension between Bey's video and his stills. That's a tension (as I see it) between the “gaze” of the enslaved, in the fractured video, and of Europeans, in the elegant, traditionally artistic, even "sublime," prints. It would be so easy for someone to think the prints were just elegant, knock-off commodities meant to fund the more truly important, more challenging video. But I think the reflection back and forth, between the settled elegance and the unsettling challenge, is vital to the entire project.

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE ENSLAVED - THE NEW YORK TIMES

CRITIC’S PICK

By Blake Gopnik

Jan. 30, 2025, 5:00 a.m. ET

The terrifying first capture in Africa.

The deadly crossing of the Middle Passage.

The brutality of slave markets and servitude.

It’s almost impossible to imagine, let alone depict, the full horrors of American slavery, although writers, directors and artists have tried.

But there’s one moment that seems to have caught their attention less often: the first encounter of kidnapped Africans with the strange new land where they were marched into enslavement.

In a remarkable exhibition called “Stony the Road,” at Sean Kelly Gallery in New York, the artist Dawoud Bey takes us on the path that tens of thousands were forced to walk, from the slave ships that landed at the James River’s docks to Richmond’s slave pens and markets.

With 14 still photos and a vast, two-sided video projection, Bey explores the Richmond Slave Trail that extends for several miles in Virginia’s capital. At Sean Kelly, Bey’s stills

are the first art you encounter. Those deluxe black-and-whites, almost a yard across, show various wooded spots along the trail, avoiding any details that speak of our era. (In fact, the trail now crosses many modern settings.) We get a view of trees and ground, of bits of river and patches of distant sky, such as an African might have encountered 250 years ago.

The images were shot on old-fashioned film and printed on traditional photographic paper, so we’re treated to the velvety blacks and sparkling whites of landscapes by Ansel Adams and Edward Weston and other pioneers of American photography. It’s tempting to linger with those tasteful, orderly images — in the gallery, and in this review — but I discovered that they get a whole new meaning after seeing Bey’s video at the gallery’s rear.

That video is titled “350,000,” an estimate of the total number of enslaved people who passed through Richmond’s trading markets. (The piece was originally commissioned for a major Bey show at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond in 2023.) Ten minutes of black-and-white footage appear on a screen that bisects a big space and reaches almost to its high ceiling. It shows the same wooded path as in Bey’s prints, but to utterly different effect.

The piece works hard to put us in the place — physical, but above all psychological — of one of Richmond’s newly disembarked. The images are projected at “life scale,” Bey told me, so that the path’s tree trunks and branches are the same size on the screen as they would be if they were there before us in life. And the trip down the path is captured in a single take, without edits, by a Steadicam held at an adult’s head-height, giving a captive’s-eye view of the passage up the trail.

But the goal isn’t to create a crisp, immersive substitute for a past reality. (Bey insists that his piece isn’t about faking some kind of long-lost documentation.) It’s about using the visible artifice of fine art to encourage a trip into a past we need to confront. In some ways Bey’s video has more in common with a poet’s evocative description than with a Spielbergish attempt at historical re-enactment.

So Bey’s cinematographer, Bron Moyi, shot all the footage with a century-old Petzval lens, once used for dream sequences in silent movies. It blurs all but the middle of the scene it shows, giving an almost drunken effect to Bey’s footage, which is also shown in somewhat slow-motion. Real vision never really works quite like that, but the Petzval provides an excellent metaphor for the kind of disorientation Africans must have felt on first being shoved ashore in Virginia.

They couldn’t have known quite where they were going, or what the endgame might be — most couldn’t understand their tormentors’ language — and “350,000” has a similar lack of plot or endpoint. Its camera’s “eye” rarely looks straight down the path toward some far-off goal. Instead, it veers from earth to treetops; from river, down at right, to undergrowth that hems the path at left.

No one knows if captives would really have looked anywhere but at their own stumbling feet or at the back of the chained figure ahead, but the camera’s wandering eye evokes the fracturing of any normal they might have known. Even the flora in Bey’s video, sure to strike most Americans as an average woodland scene, must have seemed foreign.

Bey makes his disjunctive technique stand for the utter confusion — physical, cognitive, spiritual — that captives must have felt. A soundtrack, commissioned by Bey from the dance scholar E. Gaynell Sherrod, adds to the effect: It’s a mash-up of random footfalls and birdcalls, of heartbeats and hoofbeats, of grunts and sighs and clinking chains. It doesn’t quite reproduce what the enslaved might actually have heard, but it sometimes adds Hollywood melodrama that the visuals smartly avoid. However, Sherrod’s soundtrack, and its lack of obvious sync to Bey’s visuals, maps onto how trauma can fracture our perceptions.

“Bey’s installation doesn’t recreate a single moment in someone’s pain,” our critic writes. “It condenses all the moments that thousands of subjects might have suffered on the Richmond Slave Trail.” via Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles; Photo by Adam Reich

In a final touch, Bey gives art viewers a more immediate taste of that same bewilderment: The occasional visitor who peers around to the other side of Bey’s screen will eventually realize that the view there is actually the same path but seen on a different trudge down it. That gives a sense that Bey’s installation doesn't recreate a single moment in someone’s pain; it condenses all the moments that thousands of subjects might have suffered on the Richmond Slave Trail.

And then, leaving the video behind, you encounter Bey’s stills once again, and now they seem to play a different role in his story. After witnessing the splintered sights in his video, his stills now seem to stand for the very firm and settled present that today’s art world lives in, at so many removes from an enslaved person’s view.

They give us something like the stable, settled view favored by Europe’s artistic culture, circa 1800, when wild nature promised escape from the everyday into the sublime. It’s almost as though Bey’s prints offer a bright light at the end of their forest path, so that, as in many an Ansel Adams photo, the white of the immaculate silver print becomes the white of escape and transcendence. The prints have a stable authority, in their confident choice of subject, the snapping of the shutter, their deluxe printing, that isn’t there in the video.

Bey’s show gets its name from a passage in the second stanza of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the hymn by James Weldon Johnson that premiered in 1900 and is known as the Black national anthem: “Stony the road we trod/Bitter the chastening rod.”

Here’s how the stanza ends: “Out from the gloomy past/’Til now we stand at last/Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast.”

Now, 125 years later, Bey’s gloom seems to cast new light on art’s gleam.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy 248th Birthday to the US Navy!

The bravery of four Catholic chaplains in the line of duty has been recognized by US Navy vessels named in their honor:

Father Aloysius H. Schmitt and the USS Schmitt

Aloysius H. Schmitt was born in St. Lucas,Iowa on December 4, 1909, and was appointed acting chaplain with the rank of Lieutenant (Junior Grade) on June 28, 1939. Serving on his first sea tour, he was hearing confessions on board the battleship USS Oklahoma when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. When the ship capsized, he was entrapped along with several other members of the crew in a compartment where only a small porthole provided a means of escape. He assisted others through the porthole, giving up his own chance to escape, so that more men might be rescued. He received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal posthumously for his courage and self-sacrifice. St. Francis Xavier Chapel, erected at Camp Lejeune in 1942, was dedicated in his memory.

The destroyer escort USS SCHMITT was laid down on February 22, 1943, launched on May 29, 1943, and was commissioned on July 24, 1943. The USS Schmitt was decommissioned and placed in reserve on June 28,1949 and struck from the Navy list on May 1,1967.

Father Joseph T. O'Callahan and the USS O'Callahan

Joseph T. O'Callahan was born in Boston, Massachusetts on May 14, 1905. He received his training for the Roman Catholic priesthood at St. Andrews College, Poughkeepsie, New York and at Weston School of Theology, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Prior to his commissioning as a Navy chaplain on August 7, 1940, he was head of the mathematics department at Holy Cross College. His earlier duty stations included the Naval Air Station, Pensacola, Florida, the USS Ranger, and Naval Air Station, Hawaii.

Chaplain O'Callahan was the Senior Chaplain aboard the aircraft carrier USS Franklin when the Japanese attacked it off the coast of Kobe, Japan, on March 19, 1945. After the ship received at least two well-placed bomb hits, fuel and ammunition began exploding and fires were rampant. The final casualty count listed 341 dead, 431 missing and 300 wounded. Captain L.E. Gehres, commanding officer of the carrier, saw Chaplain O'Callahan manning a hose which laid water on bombs so they would not explode, throwing hot ammunition overboard, giving last rites of his church to the dying, organizing fire fighters, and performing other acts of courage. Captain Gehres exclaimed, "O'Callahan is the bravest man I've ever seen in my life."

Chaplain O'Callahan received the Purple Heart for wounds he sustained that day. He and three other heroes of the war were presented the Congressional Medal of Honor by President Harry S. Truman. He was the first chaplain of any of the armed services to be so honored. He was released from active duty 12 November 1946 to resume his teaching duties and died in 1964.

The destroyer escort USS O'Callahan was laid down on February 19, 1964 and launched on October 20, 1965. Chaplain O'Callahan's sister, Sister Rose Marie O'Callahan, was the sponsor, the first nun tosponsora U.S. Navy ship. The commissioning took place July 13, 1968, at the Naval Shipyard in Boston, Massachusetts. The USS O'Callahan had its shakedown cruise out of San Diego and later operated largely in anti-submarine training and reconnaissance in the Western Pacific. In 1982-83, the ship had an eight-month deployment in the Indian Ocean. The USS O'Callahan was decommissioned on December 20,1988.

Father Vincent R. Capodanno and the USS Capodanno

Vincent R. Capodanno was born in Richmond County, New York, on February 13, 1929. He was an avid swimmer and a great sports enthusiast. After receiving his training at Fordham University in New York City, Maryknoll Seminary College in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, and Maryknoll Seminaries in Bedford, Massachusetts and New York City, New York, he was ordained on June 7, 1957 by Francis Cardinal Spellman, Archbishop of New York and Military Vicar of the Roman Catholic Military Ordinariate. Shortly thereafter, he began an eight-year period of service in Taiwan and Hong Kong under the auspices of the Catholic Foreign Mission Society.

Chaplain Capodanno received his commission with the rank of Lieutenant on December 28, 1965. Having requested duty with Marines in Vietnam, he joined the First Marine Division in 1966 as a battalion chaplain. He extended his one-year tour by six months in order to continue his work with the men. While seeking to aid a wounded corpsman, he was fatally wounded on September 4, 1967 by enemy sniper fire in the Quang Tin Province. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor "for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty...." He had previously been awarded the Bronze Star Medal for bravery under battle conditions.

The destroyer escort USS Capodanno keel was laid down on February 25, 1972; the ship was christened and launched on October 21, 1972 and commissioned on November 17, 1973. The USS Capodanno was designed for optimum performance in anti-submarine warfare. Deployments included operations in the Western Atlantic, West Africa, the Mediterranean, and South America. The USS Capodanno was decommissioned on July 30, 1993.

Father John Francis Laboon, SJ and the USS Laboon

John Francis Laboon, Jr., a Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, native, born April 11, 1921, was a member of the Class of 1944 at the U.S. Naval Academy and a distinguished athlete. In World War II, Ensign Laboon was awarded the Silver Star for bravery for diving from his submarine, the USS PETO, to rescue a downed aviator while under heavy fire. Lieutenant Laboon left the Navy after the war to enter the Jesuits. With the Navy never far from his thoughts, he returned to his beloved "blue and gold" as a chaplain in 1958. For the next twenty-one years, he served the Navy-Marine Corps team in virtually every community and location including tours in Alaska, Hawaii, Japan, and Vietnam, where he received the Legion of Merit with Combat "V" for his fearless action as battlefield chaplain. He was the first chaplain assigned to a Polaris Submarine Squadron and Senior Catholic Chaplain at the Naval Academy. Captain Laboon retired in in 1979 as Fleet Chaplain, U.S. Atlantic Fleet and died in 1988.

The launching of the guided missile destroyer Laboon nicknamed the "Fearless 58" took place on February 20, 1993, at Bath Iron Works. The highlight of the event was the presence of the honoree's three sisters and brother. Christening the ship were sisters De Lellis, Rosemary, and Joan, all members of the Sisters of Mercy. Rev. Joseph D. Laboon of the V.A. Medical Center of New Orleans offered the invocation. Former Chief of Navy Chaplains and the then-current Archbishop of New York, Cardinal John O'Connor, offered remarks. The commissioning of the USS Laboon took place on March 18,1995 in Norfolk, VA. Throughout a lifetime of service to God and Country, Chaplain Laboon was an extraordinary example of dedication to Sailors and Marines everywhere.

[all information from the USCCB website]

#catholic#catholic history#us navy#us navy history#naval history#us navy birthday#military history#military ships

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Role of Location in Choosing the Best Motorhome Storage Facility

When it comes to finding the perfect storage solution for your motorhome, location plays a crucial role. Convenience, accessibility, and proximity to major roads or destinations often determine whether a facility is right for you. For RV owners searching for motorhome storage facility, Texas offers a variety of well-equipped facilities designed to meet every storage need.

Capital RV & Boat Storage, with its strategically placed locations in Katy Hockley, Cinco Ranch, Richmond (FM 359), Tomball, and Cypress, provides unmatched accessibility and top-tier amenities for motorhome owners. Below, we’ll explore why location matters and highlight the features of each Capital RV & Boat Storage facility.

Why the Location Matters for Motorhome Storage?

1. Weather Issues

Having a storage facility near major highways or your home reduces the hassle of driving long distances just to pick up your motorhome. Locations near well-connected roads make it easier to plan trips and access your RV at any time.

2. Accessibility

Convenient access to the facility is vital for RV owners. Facilities offering wide driveways, 24-hour access, and user-friendly entry systems make storage and retrieval seamless.

3. Climate Considerations

Texas weather can be extreme, with intense heat, storms, and occasional hail. A well-located facility with covered or enclosed storage options can protect your motorhome from these elements.

4. Security

Facilities located in safe neighborhoods with advanced security measures like gated access and surveillance cameras provide peace of mind for RV owners.

Continue the Conversation on Why is Texas an Ideal Location for Storing RVs and Boats?

Capital RV & Boat Storage Locations

1. Katy Hockley: Comprehensive Vehicle Storage Solutions

We are located in Katy Hockley. This facility offers both covered and uncovered storage for RVs, boats, trailers, and semi-trucks. It’s ideal for those needing a reliable vehicle storage solution close to major routes like Highway 99 and I-10.

Features:

1. Large angled parking for easy move

2. Electricity available for covered units

3. Fenced and gated perimeter with 24-hour video surveillance

4. 24/7 facility access and night-lighted driveways

Service Areas:

Katy Hockley serves a broad range of areas, including Katy Cinco, Cypress, Richmond, Rosenberg, Fulshear, Waller, and Tomball. It is a preferred choice for residents near Cinco Ranch, Lake of Bella Terra, Westheimer Lakes, Cross Creek Ranch, Weston Lakes, Candela, and other neighborhoods along major routes like Highway 290, Highway 249, and the 99 Tollway.

Ready to store your RV or boat? Check the directions here and reserve a unit today.

2. Cinco Ranch: Covered Storage Unit in Katy Cinco

The Cinco Ranch location specializes in covered storage for RVs and boats, offering added protection from weather elements. Situated conveniently near local neighborhoods and travel routes, this facility is perfect for those seeking a covered storage unit in Katy Cinco.

Features:

1. Wide driveways with back-in and pull-through options

2. Electricity hookups for covered units

3. Fenced and gated for enhanced security

4. 24-hour video Surveillance which is locally managed.

Service Areas:

Cinco Ranch serves residents in Katy, Richmond, Rosenberg, Fulshear, and nearby neighborhoods such as Lake of Bella Terra, Westheimer Lakes, Cross Creek Ranch, Weston Lakes, Candela and others. Its strategic location ensures accessibility for all RV and boat owners in the area.

Ensure your motorhome stays protected. Check the directions here and reserve your unit today.

3. Richmond (FM 359): Fully Enclosed Vehicle Storage

The Richmond facility, located along FM 359, provides fully enclosed storage options, offering maximum protection for your motorhome or boat. If you’re looking for fully enclosed vehicle storage in Richmond (FM 359), this location ensures your vehicle is shielded from harsh Texas weather.

Features:

1. Fully enclosed storage units

2. Electricity for maintenance needs

3. Fenced and gated access with video surveillance

4. 75' Foot Wide Driveways

Service Areas:

Richmond serves the communities of Richmond, Fulshear, Katy, Cross Creek, Cinco Ranch, Lakes of Bella Terra, Long Meadow Farms, Waterside Estates, Texana, Pecan Grove and nearby areas. It is conveniently situated to cover a wide range of neighborhoods.

Reserve your spot at our vehicle storage facility. Check the directions here for location details.

4. Tomball: Self Storage RV & Boat Facility

The Tomball location offers fully enclosed & self storage facility for RV & Boat in Tomball, providing an excellent option for those needing extra protection and security. This facility is perfect for long-term storage, keeping your motorhome safe from both weather and theft.

Features:

1. Surface Parking Available

2. All The storage Units With Electric Outlet & Lights

3. Fenced and gated perimeter

4. 24-hour video surveillance with 24/7 facility access

Service Areas:

Tomball serves residents in Cypress, Tomball, Magnolia and The Woodlands apart from several other neighborhoods. Its location near FM 2920, Highway 249, and Toll 99 makes it accessible to many communities in the area.

Be among the first to store your RV here. Check the directions here and reserve your storage unit

5. Cypress: Enclosed RV & Boat Storage in Cypress, TX

The Cypress location specializes in enclosed RV & boat storage in Cypress, TX, offering enclosed and covered options. With advanced security features and convenient access, this facility is ideal for those wanting high-level protection for their RV or boat.

Features:

1. Enclosed and covered storage options

2. Electricity for covered units

3. Fenced and gated access with surveillance

4. Wide driveways and 24/7 accessibility

Service Areas:

Cypress serves residents in Cypress, Katy Hockley, Waller, Tomball, and surrounding regions. Its proximity to Highway 290, Highway 249, and the 99 Tollway ensures convenient access for customers.

Reserve your spot early by joining the waitlist. Check the directions here to find this facility.

Pre-book Your Spot Today

How Capital RV & Boat Storage Stands Out

Capital RV & Boat Storage facilities are designed with the needs of RV and boat owners in mind. Here’s why we’re the top choice for motorhome storage facility in Texas:

1. Flexible Contracts: We offer month-to-month rentals, providing flexibility without long-term commitments.

2. Comprehensive Security: All facilities feature gated access, 24-hour video surveillance, and well-lit areas to ensure the safety of your motorhome.

3. Convenient Amenities: Electricity for covered units, large angled parking, and wide driveways make our facilities user-friendly.

4. Accessible Locations: With multiple locations near major routes and neighborhoods, accessing your storage unit is easy and stress-free.

5. Variety of Options: From covered to fully enclosed units, we cater to various storage needs to keep your RV or boat in excellent condition.

Read More About : Top 10 Reasons to Choose a Local Vehicle Storage in Katy, TX

Final Thoughts

Choosing the right location for the storage of your motorhome is essential for convenience, protection, and peace of mind. Whether you need a covered storage unit in Katy Cinco, fully enclosed vehicle storage in Richmond (FM 359), or covered RV storage in Cypress, TX, Capital RV & Boat Storage offers top-tier facilities across Texas.

With flexible contracts, state-of-the-art security, and strategically placed locations, Capital RV & Boat Storage ensures your motorhome or boat stays secure and ready for your next adventure. Reserve a unit or join the waitlist today to experience the best storage solutions Texas has to offer.

The article was originally published on Capital RV & Boat storage. Read the original Article here: Motorhome Storage Facility

0 notes

Text

"LAKE SHORE TOWNS LEAD VICTORY LOAN," Toronto Star. October 26, 1942. Page 8. ---- Etobicoke, Mimico, New Toronto, Long Branch Reach. 57 p.c. of Objective. --- Etobicoke township and the Lakeshore municipalities of Mimico, New Toronto and Long Branch led all of Ontario today when returns from the first week's sale of victory bonds were tabulated. General canvass and employee payroll deduction subscriptions in the Etobicoke-Lakeshore unit exceeded $1,000,000 or 57 per cent. of an objective of $1,775,-000, officials said. Subscriptions by sub-divisions, with objective shown in brackets, up to Saturday night were: New Toronto, $384.150 ($633,000); Long Branch, $212,450 ($332,000); Kingsway-Lambton Mills, $194,700 ($265,- 000); Mimico. $96.350 ($240.000); Islington, $60.750 ($125,000); North Etobicoke, $34.000 ($75,000); South Etobicoke, $27.850 ($105,000). In the York township-Swansea unit subscriptions today had almost reached one-third of the general canvass objective of $2,225,000, officials reported. The combined total, including bonds bought by large industries, was 56 per cent. of the total objective of $3,475,000 for the area, they said. Bonds to the value of $522.000 were sold up to Saturday in the North York township - Weston Swansea campaign unit. This is more than 27 per cent. of the general canvass objective of $1,925,000, officials said. In the York county north area, including the municipalities of Newmarket, Aurora, Richmond Hill, Sutton, Woodbridge, Stouffville, Markham, and the rural townships, subscriptions np to Saturday were) $329,150 against an objective of $1,600,000, H. L. Trapp, unit organizer at Newmarket, reported.

#victory bond campaign#victory bonds#etobicoke#mimico#long branch#york township#mobilization of wealth#canada during world war 2#total war#home front

0 notes

Text

#affordable hvac rental contracts#ontario hvac service provider#end-to-end hvac service guelph#attic insulation mississauga#hvac contractors in weston#hvac provider markham#home heating protection plan#fire alarms richmond hill

0 notes

Text

Mrs. Churchill: The Most Unfairly Maligned Woman in Jane Austen

We never meet Mrs. Churchill in Jane Austen’s Emma, everything we know about her is second- (Frank) or third- (Mr. Weston) hand. But once you read the book a second or tenth time, it becomes clear that Mrs. Churchill was getting progressively worse, ending in her death and Frank knew this.

Mrs. Churchill is far more sick than Frank ever admits. He often uses her as an excuse to neglect visiting his father. Everyone in Highbury thinks Mrs. Churchill is faking because it's so convenient that she's sick when Frank is supposed to visit. But we know the truth, he doesn't visit until Jane comes to Highbury, he is staying away on purpose.

But she does decline during the course of the novel

Evidence of her decline:

We know that the Churchills go to London yearly with Frank, “He saw his son every year in London” and yet, Frank says to Emma, “and if my uncle and aunt go to town this spring—but I am afraid—they did not stir last spring—I am afraid it is a custom gone for ever.” This custom has happened every year of Frank’s life and now is suddenly ended. Sounds like Mrs. Churchill was too sick to go the year prior and Frank does not expect her to get better.

According to Mr. Weston, Frank can come if the Churchills do not visit a family called the Braithwaites, “But I know they will, because it is a family that a certain lady, of some consequence, at Enscombe, has a particular dislike to: and though it is thought necessary to invite them once in two or three years, they always are put off when it comes to the point.” But the Churchills do actually go for the visit. As if they are saying goodbye and seeing people for the last time.

Mrs. Churchill does allow Frank to stay in Highbury for the ball, and then suddenly withdraws consent, “A letter arrived from Mr. Churchill to urge his nephew’s instant return. Mrs. Churchill was unwell—far too unwell to do without him; she had been in a very suffering state (so said her husband) when writing to her nephew two days before, though from her usual unwillingness to give pain, and constant habit of never thinking of herself, she had not mentioned it; but now she was too ill to trifle, and must entreat him to set off for Enscombe without delay.” This seems like a petty power play until we remember that she does actually die at the end of the book. Several close calls are normal for a person experiencing hospice care or a sudden decline in health.

Then Mrs. Churchill suddenly decides to go to London, which makes sense if she’s been getting much worse and wants to consult the London physicians:

“The evil of the distance from Enscombe,” said Mr. Weston, “is, that Mrs. Churchill, as we understand (in italics in the text), has not been able to leave the sofa for a week together. In Frank’s last letter she complained, he said, of being too weak to get into her conservatory without having both his arm and his uncle’s! This, you know, speaks a great degree of weakness—but now she is so impatient to be in town, that she means to sleep only two nights on the road.—So Frank writes word. Certainly, delicate ladies have very extraordinary constitutions, Mrs. Elton. You must grant me that.”

Frank actually stays away from Jane against his inclination when Mrs. Churchill is in Richmond. Mrs. Churchill is actually getting worse and he's not a complete dick, he stays with her:

This was the only visit from Frank Churchill in the course of ten days. He was often hoping, intending to come—but was always prevented. His aunt could not bear to have him leave her. Such was his own account at Randall’s. If he were quite sincere, if he really tried to come, it was to be inferred that Mrs. Churchill’s removal to London had been of no service to the wilful or nervous part of her disorder. That she was really ill was very certain; he had declared himself convinced of it, at Randalls. Though much might be fancy, he could not doubt, when he looked back, that she was in a weaker state of health than she had been half a year ago. He did not believe it to proceed from any thing that care and medicine might not remove, or at least that she might not have many years of existence before her; but he could not be prevailed on, by all his father’s doubts, to say that her complaints were merely imaginary, or that she was as strong as ever.

and later: The black mare was blameless; they were right who had named Mrs. Churchill as the cause. He had been detained by a temporary increase of illness in her; a nervous seizure, which had lasted some hours—and he had quite given up every thought of coming,

Also, let us consider how much hatred is directed at Mrs. Churchill for wanting her adopted nephew to stay by her while she is dying, whilst Mr. Woodhouse, who basically imprisons his daughter with all his fancies of ill health, is widely loved. Mrs. Churchill is the alleged hypochondriac who is actually sick, while Mr. Woodhouse worries about his health, but has no recorded illness through the entire book.

To sum up, Mrs. Churchill was getting progressively worse over the course of the novel. She very reasonably wanted her adopted child to be near her. Frank does actually do his duty to his aunt, indicating that he is well aware of how sick she has become. Mrs. Churchill’s death was not sudden, it happens at the end of a decline lasting about a year, or a bit longer.

#emma#frank churchill#mrs churchill#most unfairly maligned woman#she probably had a very painful progressive disease#and is pilloried for wanting her kid near her#it's her kid#she raised him#mr. weston#yet no one is mad at mr. woodhouse for never allowing emma to go anywhere#frank has been to weymouth and other places#I suspect sexism#jane austen memes#emma the book not the character

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunday, 26th June: Mrs. Churchill is no more

Read the post and comment on WordPress

Read: Vol. 3, ch. 9 [45]; pp. 254–255 (“The following day” to “with mutual forbearance”).

Context

An express arrives at Randalls telling of Mrs. Churchill’s death.

In July, Frank writes a letter referencing this as “‘the event of the 26th ult. [of last month]’” (vol. 3, ch. 14 [50]; p. 289); an express sent from Richmond to Highbury would arrive the same day it was sent.

An “express” is a letter that is carried directly from sender to receiver, rather than being carried from post office to post office; it is thus quicker to arrive and more expensive to send. Mr. Weston’s resolution “that his mourning should be as handsome as possible” and Mrs. Weston’s contemplation of “hems” are in reference to a tradition of wearing mourning clothes for some time after the death of a family member. The reference to Goldsmith (“when lovely woman stoops to folly, she has nothing to do but to die”) is drawn from The Vicar of Wakefield.

The Norton edition has “not spoken of with compassionate allowances” (p. 254); the 1816 publication has (what seems to be more compliant with the context) “now spoken of” (p. 156).

Note that the section “Murder, She Wrote” contains spoilers.

Readings and Interpretations

Murder, She Wrote

Leland Monk gives a summary of the events of the past few days as they impacted Jane and Frank, which is worth quoting at length:

Frank Churchill’s engagement to Jane Fairfax had to be kept secret while his aunt was alive because Mrs. Churchill would certainly not approve of such a connection and would no doubt deprive Frank of the considerable fortune he stood to inherit if he married against her wishes. Mrs. Churchill had been in ill health for awhile and apparently Frank and Jane were holding out until her death, at which time they could appeal to her more tractable husband.

[...] All the tension and aggravation of their secret understanding came to a head in a quarrel that made both of them seriously consider ending the engagement. The private quarrel between the two lovers was played out in the public arena the next day during the disastrous picnic to Box Hill. Jane was cold and severe, while Frank flirted outrageously with Emma in front of his fiancée. Jane conveyed to him “in a form of words perfectly intelligible” that she was quite willing to end their acquaintance: “I would be understood to mean, that it can be only weak, irresolute characters, (whose happiness must always be at the mercy of chance,) who will suffer an unfortunate acquaintance to be an inconvenience, an oppression for ever.” Frank responded by proposing to Emma (but for Jane’s ears) that he would go abroad for a couple of years—the usual way gentlemen who can afford to do so extricate themselves from unpleasant intimacies. Frank left Highbury that afternoon, returning to Richmond without patching things up, and Jane wrote to him next day breaking off the engagement. Their relationship under the conditions of secrecy had reached a dead end. If those conditions did not somehow change, they were almost certainly going to part forever. (pp. 343–4)

Monk goes on to argue that Emma is a mystery in a different way than other critics suggest—rather than asking us to solve riddles such as “whom does this charade designate” and “who is Harriet in love with,” it is a murder mystery. He writes:

Mrs. Churchill died two days later, not only at a suspiciously convenient time but of a suspiciously unknown cause. Here is Jane Austen’s announcement of her death; and notice the unusual attention given to time and circumstance: “Though her nephew had had no particular reason to hasten back on her account, she had not lived above six-and-thirty hours after his return. A sudden seizure of a different nature from anything foreboded by her general state, had carried her off after a short struggle. The great Mrs. Churchill was no more” [vol. 3, ch. 9 [45]; p. 254]. In the same sentence we are told of Frank’s return and his aunt’s death; the syntax would seem to suggest a cause and effect relationship—Frank’s return precipitated his aunt’s unexplained death.

[...] The evidence suggesting that Mrs. Churchill was murdered by her nephew is not conclusive, but given the timing of her death and the motive, opportunity, and psychology of Frank Churchill, it is remarkable that even his most severe critics consider his aunt's passing simply “fortuitous,” a bit of “luck,” “a happy and timely accident.” (pp. 344, 349)

This oversight may be caused in part by our understanding that a novelist may “kill” characters off for plot reasons (“the possibility of actual murder in Emma is subsumed by novelistic conventions which have inured us to death as a way of resolving plot complications”), as well as by our assumption that murder is not something that can happen in an Austen novel (however much we are used to the “constant and corrective ‘mortification’ of an Austen character,” a more everyday type of violence that is “especially directed against women,” p. 350). For Monk, though, the most interesting aspect of this reading is how

the suggestion of murder in Emma indicates how completely Jane Austen practices what she preaches against, making her in many ways Frank Churchill’s accomplice in crime. That which the novel’s moral code condemns in Frank is clearly evident in his creator’s own novelistic practices: all of the puzzles in the novel, and especially those posed by the writer to the reader, show how Austen, like her character, enjoys playing games that mystify and deceive. (ibid.)

The Hypochondriacs Are All Right

Anita Soloway writes that Mrs. Churchill’s death is one example of how the “war, illness, accident, painful reversals of fortune—so prominent in Persuasion—already hover on [Emma’s] periphery” (n.p.). Mr. Woodhouse, who “warns us of the precariousness of life,” therefore seems worth paying some attention to:

Whatever the source of his anxieties may be, Mr. Woodhouse functions at once as a classic comic killjoy—“’The sooner every party breaks up, the better’” [vol. 2, ch. 7 [25]; p. 136]—and as a foreboding voice, persistently warning both the other characters and the readers of how fragile our lives really are. His warnings are vindicated not only by Jane Fairfax’s nearly fatal accident but also by the unexpected death of Mrs. Churchill from “[a] sudden seizure of a different nature from any thing foreboded by her general state” [p. 254]. (ibid.)

These peripheral “examples of the vulnerability of our lives,” however, are softened precisely by the fact that they are peripheral:

Arguably the most pitiable figure of Emma, John Abdy never actually appears in it but is only mentioned once in passing by Miss Bates. While talked of much more frequently, Mrs. Churchill, the only character who dies in the course of Emma, also never actually appears. […] Jane’s [accident] predates the action of the novel, and the information about it is buried in Miss Bates’s chatter. The deaths of Lieutenant Fairfax and of the mothers of Emma, Jane, and Frank occurred, of course, many years before the novel begins. By creating temporal and emotional distances between the reader and these characters and events, by relegating them to the outskirts of the novel, Austen carefully subordinates the vision of the fragility of our lives to the novel's primary focus on Emma’s moral development. (ibid.)

DA Miller similarly notes Austen’s “proscription […] that no major character may die, and no character whatsoever may die ‘on stage,’” arguing that it “frustrate[s] any possible development of the large-looming, but abidingly static, theme of hypochondria” (p. 79). “[T]he decease of the hypochondriac Mrs. Churchill” does, however, make the dual-edged point that hypochondria is pointless foolishness that nonetheless has some basis in reality (FN 37, p. 106):

For only [hypochondria’s] antiphrasis of death could unfold the folly of hypochondria: the ultimate irrelevance of our minor or mendacious maladies to the great killer that, despite the fuss we make over them, they don't even have the merit of preparing us for [“of a different nature than any thing foreboded…”]. And only the antiphrasis of death could let us grasp the grain of truth that, in among its salts and vials, hypochondria nonetheless contains: that we are indeed always suffering from something that will be ‘the death of us’—life. But like disaster, death […] is “news… to throw every thing else into the back-ground.” (pp. 79–80)

Can Mrs. Churchill be assumed to be a hypochondriac, though, as these critics take for granted? Mr. Weston has seemed to think so—but as her illness, real or imaginary, is standing in the way of his seeing Frank, his personal stake in the matter needs to be considered. And, as we have already seen, Frank once “could not be prevailed on by all his father’s doubts, to say that her complaints were merely imaginary” (because he was more familiar with the nature of her complaints than Mr. Weston was? or because he was trying to present himself as the image of respectful gratitude?) (vol. 3, ch. 1 [19]; p. 206). The evidence that Mr. Weston tries to summon, that Mrs. Churchill was one day “too weak to get into her conservatory” under her own power and another day “so impatient to be in town, that she means to sleep only two nights on the road” means just about nothing, given that it is in the nature of much chronic illness to be changeable [vol. 2, ch. 18 [36]; p. 200]. John Wiltshire writes:

The mystery, or undecidability, of Mrs Churchill’s illness is not resolved, either, by her death. ‘Mrs Churchill, after being disliked at least twenty-five years, was now spoken of with compassionate allowances. In one point she was fully justified. She had never been admitted before to be seriously ill. The event acquitted her of all the fancifulness and all the selfishness of imaginary complaints’ [p. 254]. She is now admitted into Highbury discourse on its own terms as ‘Poor Mrs Churchill!' But Highbury is obtuse and the ambiguity persists, since she is carried off, as the narrator makes occasion to say, ‘by a sudden seizure of a different nature from any thing foreboded by her general state’. How one reads Mrs Churchill’s illness depends then upon one’s own interests, position and point of view—perhaps one’s own state of health. (p. 122)

At any rate it seems foolish to assume that one knows the truth either way, regarding a novel that not only makes a motif out of robust versus ill health (see Wiltshire) but also repeatedly dramatizes the dangers of assuming that one knows how to decode the world around oneself.

She Stoops to Folly

The narrator paraphrases Oliver Goldsmith in an aside upon Mrs. Churchill’s death: “Goldsmith tells us, that when lovely woman stoops to folly, she has nothing to do but to die; and when she stoops to be disagreeable, it is equally to be recommended as a clearer of ill fame” (p. 254). Marvin Mudrick attributes offhand remarks about death of this sort to “cruelty” and “malice” on Austen’s part (qtd. in Johnson, p. 159); Frances Restuccia, though she does not condemn Austen for the joke, attributes the sentence to “a surprising snide reference against [Mrs. Churchill]” from the narrator (p. 453).

For Claudia Johnson, however, the aside is not an insult but “a stunning, deadly serious piece of social criticism” (p. 160). She elaborates on the literary and social context of Goldsmith’s remark:

“Stooping to folly” is, of course, a euphemism for being seduced and abandoned. In English novels of sensibility, the deaths of lovely women—through an act of suicide or, which amounts to a similar thing, through a mortal or near-mortal superabundance of remorseful feeling—almost always follow this form of disgrace, although death also awaits women of feeling who have been wronged by an unfeeling world in less compromising ways. (ibid.)

Thus “Austen’s novels defy and discredit this call [for the death of women who do not satisfy a set of narrow conventions], not because death is impolite, as Janeites might have it, but because to satisfy readers’ cravings for deathbed scenes would mean consenting to social assumptions that make such scenes appear desirable and natural in the first place” (ibid.).

Discussion Questions

Is it feasible that Frank Churchill could have murdered his aunt? What evidence should such a case be tried on (textual evidence, evidence of motive, evidence of genre)?

Does Mrs. Churchill’s death prove, as Highbury at large professes, that she has not been a hypochondriac all along? What is Emma’s stance on hypochondria?

What is the purpose of the Goldsmith reference in this section?

Bibliography

Austen, Jane. Emma (Norton Critical Edition). 3rd ed. Ed. Stephen M. Parrish. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, [1815] 2000.

Johnson, Claudia L. “A ‘Sweet Face as White as Death’: Jane Austen and the Politics of Female Sensibility.” Novel 22.2 (Winter 1989), pp. 159–74. DOI: 10.2307/1345801.

Miller, D. A. Jane Austen, or the Secret of Style. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2003).

Monk, Leland. “Murder She Wrote: The Mystery of Jane Austen’s Emma.” The Journal of Narrative Technique 20.3 (Fall 1990), pp. 342–53. DOI: 10.2307/30225305.

Restuccia, Frances L. “A Black Morning: Kristevan Melancholia in Jane Austen’s Emma.” American Imago 51.4 (Winter 1994), pp. 447–69.

Soloway, Anita. “The Darkness of Emma.” Persuasions 38 (2016), pp. 81–94.

Wiltshire, John. “Emma: The Picture of Health.” In Jane Austen and the Body. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1992), pp. 110–54. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511586248.005.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

FOLK TALES AND FAIRY TALES FROM INDIA. Cover design by Patricia Richmond (2017).

———

Heroic Works, Designers Bookbinders International Competition 2017 was a travelling exhibition that ran from July 18 through August 20, 2017, in Weston Library at the University of Oxford. #bookbinders competition

source

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first Commanding Officer of USS TEXAS (BB-35) was Captain Albert Weston Grant. In 1913, he took command of TEXAS during her builder's trials. He was her Captain from March 12, 1914 till June 10, 1915 and retired on April 6, 1920, Vice Admiral Grant. He passed away in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on September 30, 1930.

He was born on April 14, 1856 at East Benton, Maine and grew up at Stevens Point, Wisconsin. "He was appointed to the United States Naval Academy in 1873. Until 1913 the law required that Naval Academy graduates serve two years at sea before being commissioned ensign.

Upon graduation in 1877, Graduated Midshipman Grant served his two years in the old Civil War veteran ship USS PENSACOLA (1859) before transferring to USS LACKAWANNA (1862) and receiving his commission in 1879.

He had a long, distinguished career in the Navy, serving in a great many ships before being assigned to TEXAS. His early years as a young naval officer saw the transformation of the United States Navy from the age of wooden-hulled vessels, some still driven by sail, to modern all-steel, steam-powered ships. In fact, Grant later participated personally in the Navy’s modernization efforts by helping to bring electrical power to his venerable old ship Pensacola.

As important as the technological changes that were taking place in the Navy during Grant’s time, and the expansion of the numbers and types of ships in the Navy, was the need to transform the 'mind set' of officers and sailors alike. Naval vessels had always operated as independent entities responsible for carrying out the Navy’s mission at home and abroad. It was now becoming necessary to operate in units, with coordinated movements, to face the potentia threat of other nation’s navies in more complex combat actions than the simple line of ships. The creation of the Naval War College was part of the process of training naval officers in the new strategy and tactics of a modern navy.

Grant was one of the early student naval officers, and when completed the course at the War College he was sent back to sea in USS TRENTON (1876) (operating as part of the Asiatic Fleet), USS RICHMOND (1860) (Asiatic Fleet), USS SARATOGA (1842) (operating as a school ship) and then USS YORKTOWN (PG-1) (operating on the Atlantic Station). The latter two ship names will one day be much more familiar when assigned to aircraft carriers. Following his time in those four vessels, Lt (now full lieutenant) Grant returned to the Navy Yard at Norfolk. It was during this stint that he was part of the team bringing electricity onto Pensacola.

After a three-year posting as an instructor at the Naval Academy, an assignment reserved for the most impressive of young officers, Lt. Grant returned to sea duty, and soon found himself serving on USS MASSACHUSETTS (BB-2), during the Spanish-American War. Aboard Massachusetts, Grant experienced his first naval combat. As part of the initial blockade of Cuba, MASSACHUSETTS shelled Spanish forts and fought with Spanish ships. While missing the actual Battle of Santiago, she fought alongside USS TEXAS (1892) against Reina Mercedes, forcing that Spanish cruiser to ground herself.

That same year, 1898, he was transferred to the gunboat USS MACHIAS (PG-5). MACHIAS also fought in in the Spanish-American War, and at the end of 1899 steamed to Washington to participate in ceremonies honoring American naval hero Admiral George Dewey. While in MACHIAS, Grant was promoted to lieutenant commander, and then sent back to the Naval Academy to resume his role as instructor of future naval officers. Returning to sea in 1902, Lieutenant Commander Grant served in the battleship USS OREGON (BB-3), as Executive Officer (XO) and then was made Captain (CO) of USS FROLIC (1892) in 1903, operating in the Philippines.

In 1904, he returned to the Naval Academy again as an instructor, was promoted to Commander and soon put in charge of the Department of Seamanship. While in that capacity, he wrote the textbook for naval tactics, 'School of the Ship: Prepared for the use of Midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy', published in 1907 (Annapolis: United States Naval Institute, 1907). His would be the textbook used by many other future captains of battleship TEXAS during their times at the Academy. Soon, the instructor became a student as he left the Academy and took the advanced course at the Naval War College.

Finishing there, Grant was given command of the supply ship USS ARETHUSA (AO-7), one of the support vessels for the upcoming Great White Fleet, sent around the world by President Theodore Roosevelt to show off the United States Navy.

When that fleet set out on its two-year cruise, Commander Grant was made the fleet Chief of Staff, onboard USS CONNECTICUT (BB-18). During the cruise he was promoted to captain, and then named commander of CONNECTICUT. When the cruise ended in 1910, he returned to shore duty and was made commander of the 4th Naval District and then commander of the Philadelphia Naval Yard. In 1912 he was given command of the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, and in 1913 was named supervisor of the 3rd, 4th and 5th Naval Districts before being relieved of those jobs and transferred to the Newport News Shipbuilding Company.