#voynichese

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

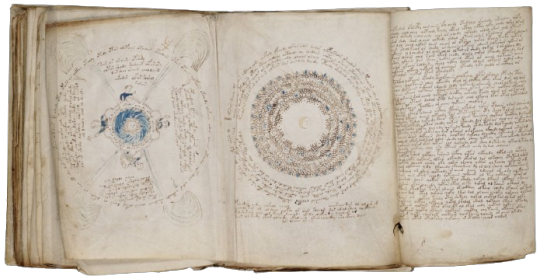

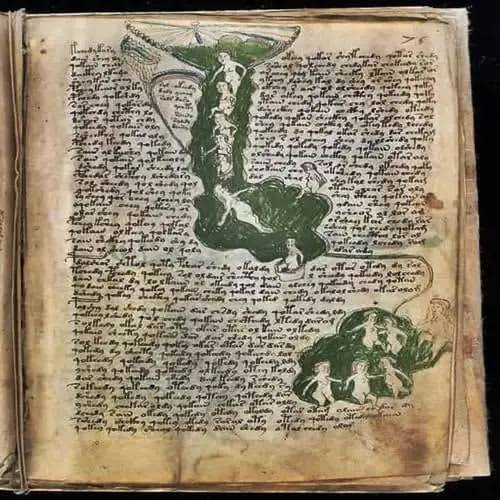

Voynich Manuscript - illustrated 15th century codex, hand-written in a strange unknown script, that has not been deciphered, referred to as Voynichese. The vellum on which it is written has been carbon-dated to the early 15th century (1404–1438).

#voynich manuscript#illustrated#codex#15th century#early 15th century#early 1400s#voynichese#unknown script#vellum

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think I have a new favorite book

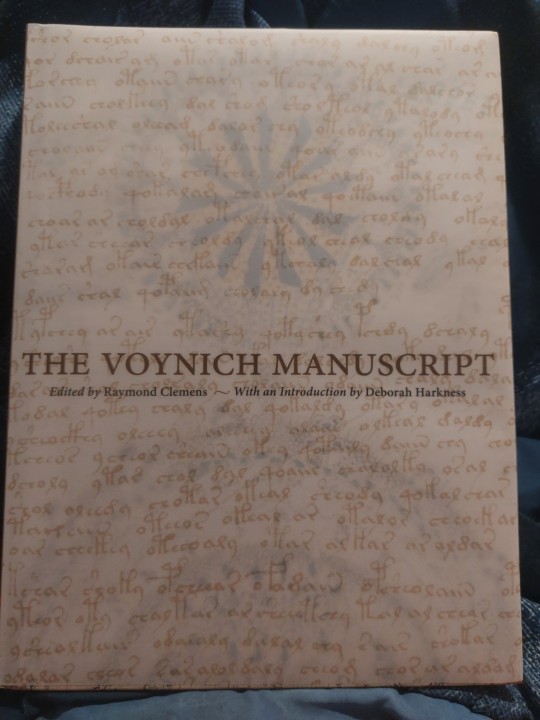

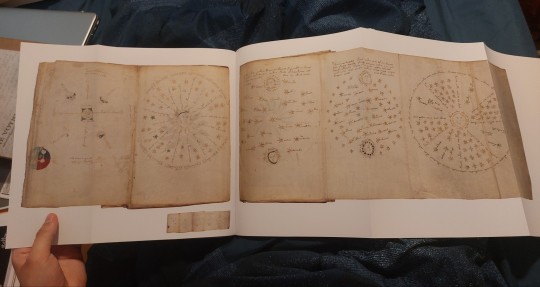

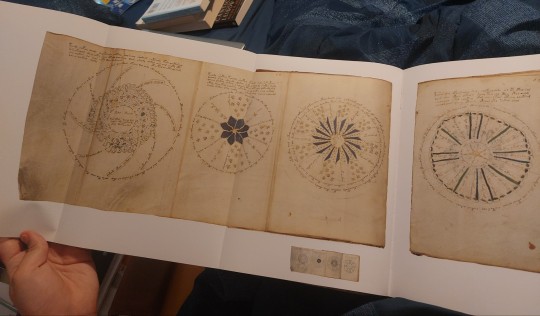

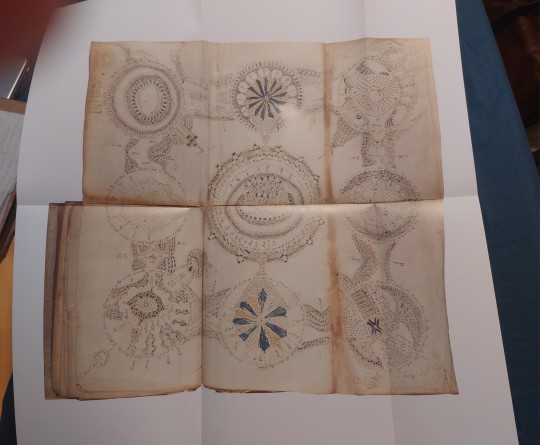

A high-quality scanned reproduction of the Voynich Manuscript with essays explaining its history and the attempts to decipher it.

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

if you do transvocab/transnativelanguage terms, then could i request transvoynichese, transmichitonese, and transrohoncian?

Trans Voynichese

Very sorry , but i could only find info about Voynichese :^( For whatever specified / unspecified reasons .

If already coined consider as an alt . Requested . No DNI . Just be nice / civil about it . Free for anyone .

#you stepped on a landmine#transid#transid coining#transid coinings#transid coins#transid coin#transid flags#transid flag#transid community#pro transid#pro radqueer#radqueers please interact#pro radq#pro transx#radq safe#radqueer#radqueer community#rq community#radqueer safe#transid safe#radqueer coining#rqc#rq safe#rqc🌈🍓#rq 🌈🍓#pro rq 🌈🍓#rq please interact#rq interact#rq coining#pro rqc

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

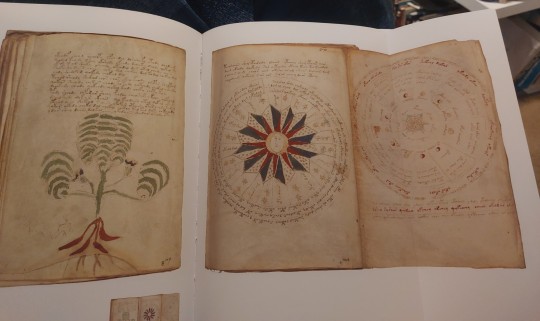

A floral illustration on page 32

The Voynich manuscript is an illustrated codex, hand-written in an unknown script referred to as 'Voynichese.' The vellum on which it is written has been carbon-dated to the early 15th century. Stylistic analysis has indicated the manuscript may have been composed in Italy during the Italian Renaissance.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

mysterious and bat for the spooky season ask game!

Bat - What’s your favorite creature associated with Halloween?

^ Myotis nimbaensis, but all its brethren are cool. This little guy is just extra spoopy.

Mysterious - What’s your favorite unsolved mystery? - Today's favourite is...

The Voynich manuscript.

...an illustrated codex, hand-written in an unknown script referred to as 'Voynichese.' The vellum on which it is written has been carbon-dated to the early 15th century (1404–1438). Stylistic analysis has indicated the manuscript may have been composed in Italy during the Italian Renaissance. While the origins, authorship, and purpose of the manuscript are still debated, hypotheses range from a script for a natural language or constructed language, an unread code, cypher, or other form of cryptography, or perhaps a hoax, reference work (i.e. folkloric index or compendium), or work of fiction (e.g. science fantasy or mythopoeia, metafiction, speculative fiction) currently lacking the translation(s) and context needed to both properly entertain or eliminate any of these possibilities.

Was the author just fucking around? Or is it actually something?

Come ask me bro.

1 note

·

View note

Note

The girl watches him eat with unfiltered fascination, studying the muscles of his tongue and the ebbing of his throat. A deformed face, instinctively terrifying to her primitive mind, but still human enough to maintain its base functions. Or so she hoped.

To her disappointment, he displayed none of the pleasure or excitement she might have in his place... Was it disgusting? Or was he above such things? Her shoulders deflate. Fine... Fine. She would offer him lore, instead, and see how that took.

❝ ... In ancient Terra, they called these marshmallows. Originally, they came from the Althaea officinalis plant, and was useful in treating ulcers and mucosa irritation... There exist some on this planet. ❞

Luna turns, returning her attention to the etched inscription. Leaving her back to one so tainted by Chaos made all the sense in her body scream —— but what choice had been left to her? A body too weak to do half of what a woman should, her weaponry broken by the massacre of the cultists; feigned ignorance and fluttering eyelashes would be her shield now.

❝ We have shared bread. That puts you under my protection while you stand beneath my ro... Ah. There is no roof. Uhm... Well! Just pretend we're in a proper house. Or... Do you live in ships? A ship, then.

This poetry implies there is some kind of city beneath here. But the word for city and labratory are the same in Voynichese... Do you want to come with me, lord angel? ❞

However the Astarte expected this woman to respond, this clearly wasn't a reaction he had anticipated. She could have threatened him or launched into a rehearsed speech about "treason" and "heresy", but chose to chide him about manners? She stood close enough that she could stab or shoot a gap in his armor with relative ease, but instead offered him a small piece of food?

Looking down at the small woman posturing in front of him, the Astarte couldn't help but tilt his head like a curious dog. Either she was buying time for reinforcements in the strangest way possible or she was living evidence of the Changer's incomprehensible schemes---as well as his sense of humor, potentially. Whatever the case, playing along was the better option.

"...Thank you," he muttered, taking the candy from her palm as gently as a thickly-armored forefinger and thumb could.

Holding the piece up to his eye, he examined it for a moment. Food and dining culture wasn't something taught to his legion or encouraged by his patron. The woman would have similar results giving a tech-priest a potted flower and expecting them to sniff it on instinct.

The Astarte couldn't confirm anything meaningful with his tactical display or internal sensors---mostly because they weren't made to analyze foodstuffs. If he wanted to understand candy, he needed to accept the risk and actually taste it.

Reaching under his chin, the Astarte unlocked an airtight seal with a hiss and removed his helmet. His skin was pallid and the whites of his eyes were black, though these could be "cosmetic" gene-flaws rather than evidence of substantial mutation. But when he held the candy to his mouth and licked it, his tongue was revealed to be forked.

Again, his head tilted in quiet contemplation. He couldn't quite place the taste, having very few experiences to recall. Whether this candy was only mildly sweet or some rich delicacy, he didn't know.

With a gentle flick, the piece flew into his mouth for further examination. The woman could see him working on it, though it would be quickly dissolved by acidic saliva. Whatever poison may have been inside was either destroyed or completely ineffective---if there was any to begin with.

#in character.#stories-from-the-warp#luna crying and sliding down the wall because the borderline demon didn't go yippee for sugar...#truly an evil creature smh.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honestly I have better luck trying to solve the Voynich Manuscript than I do at getting a girlfriend so why the fuck not.

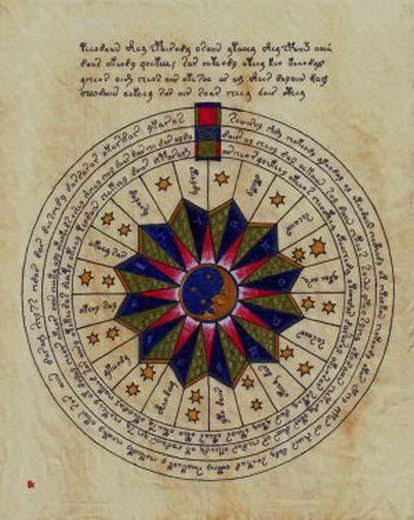

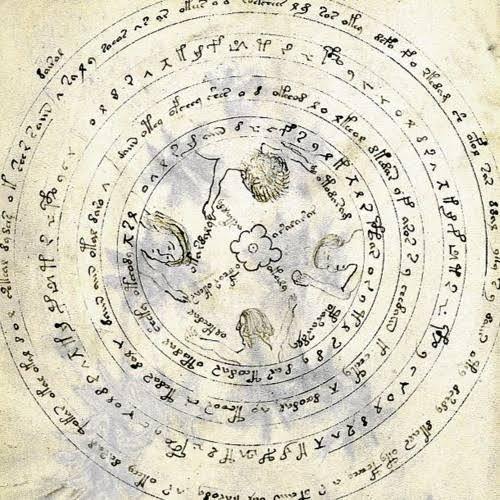

The above are what I feel to be the zodiac signs, or at least the "the bull, the fish, the scales, etc". From this I can reasonably infer that aii? and 9 are some form of ending, whether verb or noun ending I'm not sure but I'm heavily leaning to be a noun ordeal. Because of how common the 9 ending is in the text parts I've seen, im guessing it's a Masculine ending, so im assuming Voynichese has noun genders.

I'm also assuming this is located somewhere either in or east of Italy, but still in Europe. If not at least West Asia.

^ this general area, 15th century ^

Also making a guess that the bench symbol might be a vowel due to frequency in one of the pages I'm looking into at this point. I'm assuming the 2 looped H looking symbol could be an aspiration, and the hook above the bench a diacritic.

My random Latin character assignment doesnt help much but it does help me look at this all with sounds I'm familiar with.

My loving use of highlighter is for the sole purpose of trying to find a pattern a little easier, if there is one.

I figured some color coming to the situation would help, and it seems to.

I'm guessing SVO, SOV, OSV, or OVS for sentance structure, but I'm also considering conditional irregular structure. Not knowing any of the words doesnt help that a damn bit but I figured if a pattern in order can be found I could infer what the verb and subject are.

I figure this language could be compared to trying to translate Hebrew and all you have of it is a Torah. Nothing more than a Torah, can you figure out what kind of structure the language has and then compare it to language families to see if theres a match.

I may be in way over my head, I may have no idea what I'm doing and just making some guesses to the best of my ability, but at least it's easier than this trans lesbian finding a girlfriend.

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plus Ultra

It was hard to choose our favourite destination. In a universe full of wonders, we were pretty much spoiled for choice. We marvelled at the exotic flora of the Voynichese jungles; hiked the low-gravity mountains of Gontera; swam in the freshwater oceans of Lonhoea. Our hosts were as perfect as their homes, welcoming us with open spines and tentacles, excited to show off their landmarks to new tourists who had come so far to visit them.

But the wormhole was definitely our least favourite. It was the only way of travelling to such distant galaxies, but it came at a price. Not only the millennia of technological advancement that had bought us access to its mysterious pathways, but the nausea of hurtling through space at speeds our bodies weren't designed to bear, distances our minds weren't built to comprehend.

We travelled this way, that way, forward and backwards across countless galaxies, and completely lost track of time - or it lost track of us. It dilated with the gravity of passing stars, supernovae, supermassive black holes, faltering in the presence of gods. We travelled in stasis, not ageing through the light years and decades that rolled past, and expected to arrive back to a much older Earth, moved on since our departure all of those years ago.

Instead, we found the opposite. We were due to return to the base that had first launched our shuttle into the abyss, but we found it gone, its co-ordinates occupied by bobcats and panthers instead. At first, we assumed it had been lost to time, the island reclaimed by nature after humanity's collapse, but then we realised the reverse was true. This was a world before the Kennedy Space Centre. Before Kennedy. Before mankind had even looked to sail amongst the stars.

We crashed. There was no landing strip, but the ship's computers didn't know that, and dutifully returned us to the programmed destination, totalling itself in the process. We were fine, though. In fact, we slept through the whole thing: without the computer or mission control to revive us from stasis, we had no choice. We slept through the collision, and kept on dreaming as scavengers began dissembling the wreckage, and carried us out in our cryogenic pods.

It was another century before they could revive us. At least, that's what they told us, a century on. Their technology had not been advanced enough, when they first stumbled across our craft, and it must have seemed as foreign to them as the Gonteran kite-ships were to us. They were pre-industrial revolution, pre-space race, pre-AI. But that all quickly changed.

The arrival of our craft, as a cornucopia of technology, a mine of rare metals, and an endless supply of power from our onboard generators, had supercharged their development. Within a decade, they had mastered heavier than air flight. In just one more, they managed faster than light travel. Progress was easier, with the answers laid out in front of them. It may have taken us into the past, but our ship had carried them into the future.

It was towards the end of that curve that they worked out how to bring us back to life. I was dragged coughing and spluttering into the seventeenth century, my sarcophagus was whisked away for further study, and I was taken into meetings for the same. Our universal translators, well tested by alien tongues (or, in the case of the Voynichese, the vibrating of their hind limbs), made short work of the ancient Spanish, and even managed to spell out our concepts without direct equivalents in terms they understood.

Finally, my crewmates and I were left to get our own bearings on a world that was as unfamiliar as many we had come across. It was both new and old at the same time, and we only had each other to remember where we'd come from, not to mention where we'd been. We had shared our stories with the locals here, but it was nice to reflect on those memories with each other, trading pieces of the same mosaic to fill out the whole.

"This is wild, right?" I said. "Arriving at the dawn of American colonisation. I suppose we're not allowed to change the course of history?"

"I think we already have," one of the engineers pointed out. "The Spanish Empire were already dominant in this hemisphere, but think of the technological advantages we've given them. All of this knowledge, centuries ahead of schedule... that has to have drastically altered the world as we know it."

We walked through a newly constructed airstrip. Its bays hosted a dozen ships much like our own, but resplendent in royal red and golden weld, their hulls emblazoned with the Empire's motto: Plus Ultra. That retort had taken on new meaning now. Out in the wider universe, the Pillars of Hercules felt a distant memory.

The fledgling astronauts hurried between their craft, but we caught snippets of their own conversations, their translators now working just as well as ours. A discovery to surpass Columbus, one of them was saying; stumbling across a hundred New Worlds. To surpass Copernicus, his companion replied; for it will once again establish Earth as the centre of the universe.

"Not just our world," I realised. I thought about our peaceful, simple hosts, the Gonterans and Lonhoei and Voynichese, the way they'd welcomed us with open arms. The way our ship's guns could have easily dispatched them all, if we'd been that way inclined. The way we hadn't been. "We just gave intergalactic travel to the conquistadors... and, by extension, the known universe. An empire on which a dozen suns will never set."

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

THAT WOULD MAKE PERFECT SENSE I THINK YOURE RIGHT there are instances of us doing similar with language we don't understand, like linear A and the voynich manuscript (in the case of voynichese in particular one of the prevailing theories is that it was a work of fiction). I'll double check, but i know they refer to the meter the poetry is written in but I don't know about the language coming off as archaic. Unrelated but the fact that THOSE are the books that survived for them is just one of my favorite things, they got some bangin literature from the pre-res era.

tlt lang analysis update: it's driving me crazy thinking about sixth house linguists. like. i havent looked for it yet but im aware on new rho House is referred to as, well, House. if it's ever referred to as english im gonna go insane because they have greek and latin in canon so they absolutely have a way to decipher that word, but do they have enough knowledge of pre-resurrection history to know WHY it's called english? also, what in terms of a lingua franca? is it only the Houses that have a lingua franca? are there other languages within the Houses? im losing my fucking mind

288 notes

·

View notes

Note

31 39 43 49 💕

Thank you my dear Tulip!

31: What your last text message says

Not sure if this is supposed to be a text message I sent or received.

From my sister:

Oh that I so her. That’s nice sweetheart>

(I bought my mom some new inexpensive jewelry to wear.)

39: My favorite ice cream flavor

Cookies & Cream

43: Sexiest person that comes to my mind immediately

Eddie Diaz...lol

44: A random fact about anything

The Voynich manuscript is an illustrated codex hand-written in an unknown script referred to as 'Voynichese'.[18] The vellum on which it is written has been carbon-dated to the early 15th century (1404–1438). The origins, authorship, and purpose of the manuscript are debated. Hypotheses suggest that it is a script for a natural language or constructed language; an unread code, cypher, or other form of cryptography; or a meaningless hoax.

The manuscript consists of around 240 pages, but there is evidence of pages missing. Some pages are foldable sheets of varying sizes. Most of the pages have fantastical illustrations or diagrams, some crudely coloured, with sections of the manuscript showing people, fictitious plants, astrological symbols, etc.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mysterious Book that is written in an alien language : The voynich manuscript

The Voynich manuscript is an illustrated codex hand-written in an otherwise unknown writing system or script with. Very little use of Latin, referred to as 'Voynichese'. The vellum on which it is written has been carbon-dated to the early 15th century (1404–1438), and stylistic analysis indicates it may have been composed in Italy during the Italian Renaissance. The origins, authorship, and purpose of the manuscript are debated. Various hypotheses have been suggested, including that it is an otherwise unrecorded script for a natural language or constructed language; an unread code, cypher, or other form of cryptography; or simply a meaningless hoax.

It's contents are herbal, astronomical, balneological, cosmological and pharmaceutical sections + section with recipes

#the voynich manuscript#renaissance period#mystery books#alien Book#secret book#history#the secret book

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you seen Stephen Bax's partial decoding of Voynich's alphabet and its extension by Volder Z? Both are on Youtube. The punchline is "Voynich is an Indic diaspora language written in a descendant of the Syriac alphabet". I'm curious what think of them.

Seen Bax, haven’t seen Volder before now. I think Bax is making a reasonable attempt. But any decoding is going to have to fit with the known statistical properties of the letters… except we don’t even know what the letters are!

This could be one letter instead of two, for example – as could the id-looking thing at the end here:

As for the statistical stuff, everyone’s looking for a separation into vowels and consonants, but I don’t know if the assumption that the Voynichese script is an alphabet has been questioned! The manuscript comes from a cultural region where people are Christian and use alphabets, but the existence of a cultural region where people are Christian and use alphabets dates to what, the 1960s, when Nasser got all zunwang rangyi and France had its huge demerger because the alternative was open borders with its empire?

The voynich.nu analyses all seem to assume it’s an alphabet, but that’s not a safe assumption! It could be descended from, or otherwise patterned on, Syriac, or some other abjad, with or without matres lectiones…

OK – Volder. The Latin comparison looks basically reasonable to me; the problem is that Voynichese doesn’t act like Latin. Here’s his Syriac comparison:

And here are his letter value assignments:

The three left over he says might not have sound values.

The letters with straight minims (the two on the top right and the ‘®’) mostly appear word-finally, and the 4-looking thing mostly appears word-initially. (See here.)

I don’t think a curved minim (‘o’) is necessarily one letter – you also get ‘oo’ and ‘ooo’ sequences. (Cf. medieval hands where ‘i’, ‘n’, and ‘m’ were one, two, and three minims respectively – which is why English writes ‘o’ instead of ‘u’ next to ‘n’ and ‘m’.)

The nonrhoticity is a little weird:

As are these rules:

Is /z/ ever borrowed as /v/ in languages with /v/ but not /z/ – or a pharyngeal fricative as /kh/? How much precedent is there (other than English) for alternations between /r/ and /w j/? Why would /m n/ not be distinguished, and voicing and aspiration written on peripheral plosives but not coronal ones?

Overall, it looks like there are a lot of degrees of freedom here. But it’s at least testable! What happens if we apply the readings?

kas xakhn wbwⁱⁱᵈ abwⁱⁱᵈ hapwsn nbwⁱᵈ nbws abws abwstwⁱⁱᵈtwⁱr ar ?xwⁱⁱᵈ gwⁱr n ˀagwsatn cwⁱⁱᵈ akoatn ˀagwⁱr wr wsar arkngatws ˀagwⁱᵈ xaokooon ˀakoas akon ˀakwshws twsn wr wⁱRar wⁱⁱᵈ akwⁱr n twⁱrws ˀakws ˀakwⁱⁱᵈ ˀakwsn akwr askwsn akwspwⁱⁱr opwrwr ˀagwⁱⁱᵈ xasn ˀagwⁱⁱᵈ nˀakwsn akws ˀakwsn akwsnˀakwⁱr wr wsn xar twⁱⁱᵈ hasn tws nkwⁱⁱᵈ arR phon akwsn aknn taⁱⁱᵈ ˀakoon ˀakwr shotn ˀakwsar xoasc agoar wⁱⁱᵈ hokngwⁱⁱᵈ čon twstn ˀakwⁱr wswr ngwn wⁱⁱᵈ agwⁱⁱᵈ nkwⁱⁱᵈ nkwsn taⁱRtwsws ˀaswⁱⁱᵈ hačon ghasn ˀakwⁱⁱᵈ ˀakwⁱⁱᵈac arhoon aswsn…kon ǧasn ˀagwso? ˀakwsc ˀakwⁱⁱᵈ akws akwntn? arn

I don’t think so. What if we ignore all the superscripts?

kas xakhn wbw abw hapwsn nbw nbws abws abwstwtwr ar ?xw gwr n agwsatn cw akoatn agwr wr wsar arkngatws agw xaokooon akoas akon akwshws twsn wr wRar w akwr n twrws akws akw akwsn akwr askwsn akwspwr opwrwr agw xasn agw n akwsn akws akwsn akwsnakwr wr wsn xar tw hasn tws nkw arR phon akwsn aknn ta akoon akwr shotn akwsar xoasc agoar w hokngw čon twstn akwr wswr ngwn w agw nkw nkwsn taRtwsws asw hačon ghasn akw akw ac arhoon aswsn…kon ǧasn agwso? akwsc ˀakw akws akwntn? arn

I don’t know a whole lot about Romani, but akws akw akwsn akwr askwsn akws doesn’t look like any kind of natural language. Any solution to the Voynich manuscript is going to have to explain the qokedy qokedy qocheedy daiin daiiin shit, and I don’t think this does, even with possibly representing any non-back vowel plus an optional following resonant.

Well, hell, that’s one of the Currier languages. I don’t know which one because I just pulled the picture from voynich.nu, but let’s try some Currier B text:

tar wⁱs hokn kwr atwⁱⁱᵈ nks ws aooc wsarwskwRnbhotn akwⁱⁱr abhootn ˀakwⁱr twr kws agwr as ˀakws kar arasbhon aparntngoon agotwⁱⁱᵈ agwr as hotn got ˀagwr agoatwr agwR ngotn agwⁱⁱᵈ agaⁱⁱr hot wⁱⁱᵈ agwⁱr agwsn

I don’t think so. How about Currier A text?

gxooar voas čn bhas čon nbhas har hasn ˀagaǧon ˀkarncas xoas koxon ˀakooan hc hon twshon ǧoon twⁱⁱᵈ hoa Rtwⁱⁱᵈ hooakoon hočon twr asta xoan koatn akooon c wⁱⁱᵈ wscˀakon hkoon hon čon čon nkoon aⁱⁱᵈ hatn ačcn

Still looks a little weird, but maybe with severe underspecification… do any of y’all know anything about Romani?

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

In a vault in the basement of a library in Connecticut lies a book no one can read. The Voynich Manuscript, an early 15th-century codex that belongs to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, presents an irresistible medieval mystery. The tome is written using an otherwise unknown collection of symbols known to those who study the codex as “Voynichese,” with what appear to be roots, prefixes and suffixes as well as repeating spelling and grammatical patterns. Then there are the illustrations, which include unidentifiable but detailed and realistic plants, circular zodiacal and astronomical diagrams, crowned nude women bathing in green or blue pools and other images that defy description.

For centuries, the Voynich Manuscript has resisted interpretation, which hasn’t stopped a host of would-be readers from claiming they’ve solved it. In June 1921, the monthly magazine Hearst’s International announced that University of Pennsylvania Professor William Newbold had “come upon the key to the secret cipher of the [Voynich] Manuscript … and the truth of six hundred years ago is coming out!” Newbold surmised that 13th-century English scientist Roger Bacon had written the manuscript with the aid of a microscope and a telescope, centuries before the invention of either instrument. Newbold’s solution was debunked in 1931 by University of Chicago classicist John Matthews Manly in a journal of medieval studies called Speculum, leaving Newbold posthumously disgraced. Although they had once been close friends, Manly felt a moral imperative to publicly denounce Newbold’s work in the “interests of scientific truth.” “In my opinion,” he wrote, “the Newbold claims are entirely baseless and should be definitely and absolutely rejected.”

Sound familiar? It should. Every few months, it seems, a new theory is trumpeted by the news media beneath a breathless headline along the lines of “Has the Voynich Manuscript Really Been Solved?” (Spoiler alert: No, it hasn’t.) I’ve seen them all.

I’ve been critiquing Voynich theories since I was a PhD student at Yale in the early 1990s and had a job at the Beinecke Library. In addition to my other responsibilities, I was tasked with handling Voynich-related correspondence. Ever since I first laid eyes on the manuscript 30 years ago, I have been captivated not only by the object itself but also by the hold it has on both the public and the persistent and devoted “Voynichologists” who can’t get enough.

Like modern-day Newbolds, we all want to know what the Voynich means. But most would-be interpreters make the same mistake as Newbold: By beginning with their own preconceptions of what they want the Voynich to be, their conclusions take them further from the truth. Their attempts to demystify the medieval past only serve to mystify it further, making the Voynich into a telling avatar of our vexed relationship with the past.

In addition to my own work on the Voynich, which involves a detailed study of the scribes who wrote the manuscript, I’ve been increasingly called upon by the media in recent years to comment on various theories. Every solution I have seen falls apart under scrutiny, from wishful foundations to illogical conclusions.

Recent proposals that were reported worldwide argued that it was written in “Proto-Romance” (something that was not an actual language in the early 15th century), in ancient Hebrew (this theory depends in part on Google Translate, which can’t really handle medieval languages), or — as publicized just last month — in an Italian dialect transcribed using a well-known medieval shorthand system called Tironian Notation. (In fact, there is no resemblance between Voynichese and Tironian Notes.) Like others before them, these authors tend to go public prematurely — and without proper review by the real experts. Word of each new solution spreads across the globe in minutes. While it took years for Manly to call out Newbold, today’s refutations are posted within hours on Twitter or other platforms.

What is it about the Voynich Manuscript that keeps us clicking? Why do we fall for the breathless announcements, only to see them denounced within hours or days? And why should we care about the Voynich Manuscript at all?

There is, in fact, no medieval manuscript that has been seen, studied, analyzed and debated more than Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library MS 408. Dozens of solutions have been proposed in the past century alone, most of them more aspirational than they are substantive. In addition to Roger Bacon, the manuscript has been credited to Leonardo da Vinci or attributed to 16th-century Mesoamerica. Recent chemical analyses, however, concluded that the oak gall ink and the mineral and botanical pigments are consistent with medieval recipes, and Carbon-14 analysis has dated the parchment to between 1404 and 1438. That rules out Roger Bacon (who was already dead), da Vinci (who hadn’t been born), and the peoples of post-contact Mesoamerica.

I regularly receive Voynich “solutions” by email with requests for feedback. That feedback and my public comments are not always accepted in the constructively critical spirit in which they are given. I recently received an ugly and threatening direct message from a fake Facebook account referring in detail to my critique of the Proto-Romance theory, claiming that the author of the theory “will go down in history,” while I will be remembered as a “backwards looking troglodyte” who tried to slow “the advancement of knowledge and human progress” and who will “fade into obscurity.” For some, apparently, the stakes appear to be irrationally high.

The proliferation of demonstrably false Voynich solutions is indicative of a larger issue. As executive director of the Medieval Academy of America, the largest organization in the world dedicated to the study of the Middle Ages, I am acutely aware of the importance of the humanities as a discipline and the urgency of addressing the increasing threats to the study of history, languages and literature in the United States.

In this context, what are we to make of the widespread popular interest in a 600-year-old manuscript that no one can read? While it is the mystery of the Voynich that appeals, that grabs and holds the attention of a curious public, undercooked solutions presented without context lead readers down a rabbit hole of misinformation, conspiracy theories and the thoroughly unproductive fetishization of a fictional medieval past, turning an authentic and fascinating medieval manuscript into a caricature of itself.

Every new Voynich theory offers an opportunity for readers to exercise healthy, critical skepticism instead of accepting publicized solutions at face value. Proposed solutions shouldn’t automatically be rejected (the default reaction of most medievalists), but they should be approached with caution. Seek out expert opinions, and do some follow-up reading. It shouldn’t take a Voynichologist to spot a leap of logic or an argument based on wishful thinking instead of solid facts. It is only by engaging with the critical reading and interpretive skills imparted by the study of the humanities that consumers of media can deconstruct methodologies, assess hypotheses and judge for themselves the reliability of what they read. And I’m not just talking about the Voynich Manuscript.

When we approach an ancient object such as the Voynich Manuscript, we tend to bring our preconceptions with us to the table. The more we burden the manuscript with what we want it to be, the more buried the truth becomes.

The missteps of historical preconception are particularly problematic when dealing with the Middle Ages. We watch “Game of Thrones,” we read “Lord of the Rings,” we play medieval-themed video games, and therefore we think we know something about the Middle Ages. Nationalists and white supremacists misappropriate medieval symbols, imagery and narrative to serve their own vicious agendas. Using a contemporary cultural megaphone to talk over history threatens to drown out that which might otherwise be heard on its own terms. To truly understand the past, we have to let it speak for itself. The Voynich Manuscript has a voice — we just need to listen.

#Voynich Manuscript#medieval manuscripts#The Washington Post#Lisa Fagin Davis#Medieval Academy of America#Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library#Yale University#August 2019

0 notes

Text

The Unsolvable Mysteries of the Voynich Manuscript

The word “ink” is a child of the Latin incaustum, which means “having been burned.” In the Middle Ages, people thought that ink burned its way into parchment, because iron-gall inks go onto the page pale, then darken. This is not what’s happening, physically, but it makes sense as a metaphor: a medieval manuscript, because it was made by hand, is necessarily an original, even when it is a copy of something else. It cannot be standardized any more than a thing can be unburned.

The Voynich Manuscript is a special kind of original. We know, thanks to carbon dating, that it was put together in the early fifteenth century. But no living person has ever, as far as we know, understood it. Nobody can decode the language the book is written in. It has no title and no author. A new facsimile, edited by Raymond Clemens and published by Yale University Press, draws attention to the way that we think about truth now: the book invites guesses, conspiracy theory, spiritualism, cryptography. The Voynich Manuscript has charisma, and charisma has lately held a monopoly on our attentions.

The manuscript is two hundred and twenty-five millimetres tall, a hundred and sixty wide, and five centimetres thick. Yale’s new facsimile is somewhat larger, as it includes wide white margins for the amateur cryptographer’s own marginalia. The manuscript’s Renaissance-era cover (it was rebound) is made of what the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, at Yale, calls a “limp vellum.” The book has resided at Yale’s library since 1969.

Turn the covers—as Umberto Eco once did; it was the only book in the Beinecke’s famous collection that he cared to see—and you are greeted by writing in brown ink accompanied by strange diagrams and paintings of plants. The writing will not be decipherable to you. The book was made in the ordinary medieval way, but the script—the form of its letters, the language itself—was apparently invented by whoever made it. Some call the language and its script “Voynichese.” The letters loop prettily, and the text runs from left to right, top to bottom.

The first half of the book is filled with drawings of plants; scholars call this the “herbal” section. None of the plants appear to be real, although they are made from the usual stuff (green leaves, roots, and so on; search a word like “botanical” in the British Library’s illuminated-manuscript catalogue and you’ll find several texts that are similar to this part). The next section contains circular diagrams of the kind often found in medieval zodiacal texts; scholars call this part “astrological,” which is generous. Next, the so-called “balneological” section shows “nude ladies,” in Clemens’s words, in pools of liquid, which are connected to one another via a strange system of tubular plumbing that often snakes around whole pages of text. These scenes resemble drawings in the alchemical tradition, which gave rise to a now debunked theory that the thirteenth-century natural philosopher Roger Bacon wrote the book. Then we get what appear to be instructions in the practical use of those plants from the beginning of the book, followed by pages that look roughly like recipes.

Voynich is not a word from the book but, rather, the name of an eccentric book dealer, Wilfrid Michael Voynich, who bought the manuscript, in 1912. When Voynich purchased the text, it was accompanied by a letter by Johannes Marcus Marci (1595-1667), of Prague, who claimed that the book had been “sold to Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II at a reported price of 600 ducats and that it was believed to be a work by Roger Bacon.” (Voynich would later say that the seller was the occult philosopher John Dee; Clemens points out that he was nudged toward this hypothesis by a historical novel.) The book appears to have bounced around Prague for a while—in 1639, a person named Barchius described it as “a certain riddle of the Sphinx, a piece of writing in unknown characters,” and guessed that “the whole thing is medical.” The book’s historical trail vanishes in 1670, up until the time that Voynich purchased it.

Yale’s new edition affords Voynich a profile, by Arnold Hunt, which turns out to be warranted by his strong and odd personality. Voynich was born in 1864, in Telšiai, to a Polish family. He supposedly spoke twenty languages fluently. He was arrested in Kovno, in 1885, for his membership in the Proletariat Party, a social-revolutionary group, and sentenced, without trial, to exile in Siberia for five years. He got a lot of reading done there, and then he escaped, travelling widely and ultimately bartering his waistcoat and glasses for a spot on a boat from Hamburg to England. There, he became part of the intellectual circle that surrounded the Russian agitator Sergei Kravchinsky, known as Stepniak. Once his adventuring days were over, Voynich became a book dealer—a good one, although he once accidentally (one hopes) sold a forgery to the British Museum. “Voynich in later life would sometimes point dramatically to the wounds he had received” on his youthful adventures, Hunt notes: “Here I have sword, here I have sword, here I have bullet.”

In 1903, the Jesuits decided to sell a group of texts from the Collegio Romano collection to the Vatican; the sale took nine years to complete. For reasons unknown, and under conditions of total secrecy, Voynich managed to procure some of the books before they entered the Vatican Library. One of them was the Voynich Manuscript. Voynich believed that his impenetrable book contained authentic wisdom—or, at least, he said so during publicity kicks in the States, trying to make his treasured book famous. “When the time comes,” he told the Times, “I will prove to the world that the black magic of the Middle Ages consisted in discoveries far in advance of twentieth-century science.”

Voynich never cracked the code, if one indeed exists. In “Cryptographic Attempts,” another essay that accompanies the Yale facsimile, William Sherman notes that “some of the greatest code breakers in history” attempted to unlock the manuscript’s mysteries; the impenetrability of Voynichese became a professional problem for those in the code game. William Romaine Newbold, a professor of intellectual and moral philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania in the early part of the twentieth century, “persuaded himself that the writing used both a cipher common from Bacon’s alchemical manuscripts along with a separate—and far more complicated—system best described as an anagrammed micrographic shorthand.” This system of cipher “requires transposition (changing the order of the letters), abbreviation (using a system taken from ancient Greece), and microscopic notation (whereby individual pen strokes within a single character, when magnified, serve as shorthand symbols for other letters).” This theory was initially endorsed by the eminent medievalist John Matthews Manly, who had worked as one of the U.S. Army’s chief cryptologists during the First World War. But it did not hold up to closer scrutiny, and Manly eventually concluded that Newbold’s “decipherments were not discoveries of secrets hidden by Roger Bacon but the products of his own intense enthusiasm and his learned and ingenious subconscious.”

The next great mind to apply itself to the manuscript’s code belonged to William F. Friedman, another Army cryptographer, who was among the first people to use computers for textual analysis. In 1925, Manly connected Friedman and his wife, Elizebeth, also a cryptographer, with the manuscript, sending them photographs. They worked on the project for forty years. Friedman and his colleagues broke Japan’s code Purple during the Second World War, and Friedman became the chief cryptanalyst for the War Department and head of the Signals Intelligence Service in the forties and fifties. The historian David Kahn called him the “world’s greatest cryptologist.” By 1944, Friedman had formed the Voynich Manuscript Study Group with some colleagues.

The group never cracked the code. The Friedmans did, however, provide an enigmatic message about the manuscript in an article in Philogical Quarterly, “Acrostics, Anagrams, and Chaucer,” published in 1959. The article included a long excursus on the pointlessness of looking for anagrammatic ciphers; a note revealed that the statement itself was an anagram. The authors had left the solution to the anagram in a sealed envelope with the P.Q. editor. After William died in 1970, that editor revealed the message along with a reprint of the piece: “The Voynich MS was an early attempt to construct an artificial or universal language of the a priori type.—Friedman.”

According to Sherman, the majority of those who have tried their hand at the manuscript’s code “have been amateurs, and many have more interest in conspiracy theories than cryptographic systems.” Nowadays, you can find people trying to crack the code on Reddit. There are many competing theories. Some suggest that the manuscript might be part of a “conworld,” or constructed fantasy—but then one poster responds, “I don’t see why someone would create such an expensive manuscript if this were the case.” Another Redditor asks, “Anyone else wondering if this is material from a lost Mayan codex?”

You can find serious scholarly work among the Redditors’ posts, but most of it is just fun speculation. It is interesting nonetheless, because it’s written in a voice that has shaped communal understanding in our time. Speculative knowledge flourishes in moments of uncertainty and fear. “They don’t want you to know the truth,” the speculators say to their faithful, on the left and on the right. 9/11 conspiracy theories are less frightening than the truth, which is that our lives are always in danger. Astrologers point to an invisible world, freeing its subscribers from the visible one that oppresses them. Tarot facilitates healing conversations. Whether code breaker or spiritualist or amateur historian, the Voynich speculators are linked by their common interest in the past, quasi-occult mystery, and insoluble problems of authenticity. When the book was featured in a recent episode of the Sherlock Holmes-inspired television show “Elementary,” Clemens writes, it stood in “for a mysterious but learned reference to past mysteries that somehow hold important meaning for the present.”

Readers will probably never stop forming communities based on the manuscript’s secrets. Humans are fond of weaving narratives like doilies around gaping holes, so that the holes won’t scare them. And objects from premodern history—like medieval manuscripts—are the perfect canvas on which to project our worries about the difficult and the frightening and the arcane, because these objects come from a time outside culture as we conceive of it. This single, original manuscript encourages us to sit with the concept of truth and to remember that there are ineluctable mysteries at the bottom of things whose meanings we will never know.

Dig Deeper: https://youtu.be/SQTzbk0qBpw

Digital Copy of the Voynich Manuscript: https://archive.org/details/TheVoynichManuscript

Solved? https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/09/has-the-voynich-manuscript-really-been-solved/539310/

*Dedicated to Maggie*

0 notes

Link

ふ〜ん。そうなんだ(゚Д゚) で、あなたの解読は? AとBの2タイプがあって、アルファベットより少ない文字なんでしょ? 違う、って言うだけなら誰でも言えるよ? (信じてない訳では無いのでちゃんと反証を願う)

0 notes

Text

Linear A and Voynichese are a little different in that no one knows a damn thing about what they fucking mean, but I think it's the same idea? Let me clarify just so I know we're on the same page.

Like, the Resurrected woke up and learned English from John with zero context for anything, but they had some translations of the Iliad and so on written in archaic English, as even more modern translations of the Iliad tend to be, so they went "Oh, I guess that's how that kind of poetry is written. This is a dialect used only for epic poetry. Cool. We'll write poetry in it, too!"

So the Noniad could be written Like That because it's poetry, and no one in the Nine Houses ever really talked like that. Now there is evidence against this in that Nonius does talk Like That in the River, but I submit as counter-counter evidence that Wake also starts speaking Like That when the rules of the setting are under the influence of the Noniad. Nonius may be influenced by his conduit, and is speaking using grammar and vocabulary a House speaker would usually expect to only find in poems.

Is that the same direction you were going with the Linear A comparison, or is there some new and exciting connection in there that I'm not quite getting yet?

tlt lang analysis update: it's driving me crazy thinking about sixth house linguists. like. i havent looked for it yet but im aware on new rho House is referred to as, well, House. if it's ever referred to as english im gonna go insane because they have greek and latin in canon so they absolutely have a way to decipher that word, but do they have enough knowledge of pre-resurrection history to know WHY it's called english? also, what in terms of a lingua franca? is it only the Houses that have a lingua franca? are there other languages within the Houses? im losing my fucking mind

#I was thinking of stuff like Japanese Keigo#grammatical forms that are context dependent#and these grammatical forms would be used in context: poetry#the locked tomb#tlt lang analysis#tlt meta#long post

288 notes

·

View notes