#vladimir sorokin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

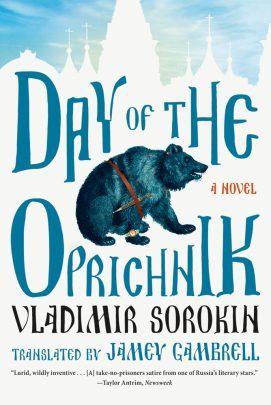

Vladimir Sorokin, Day of the Oprichnik

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

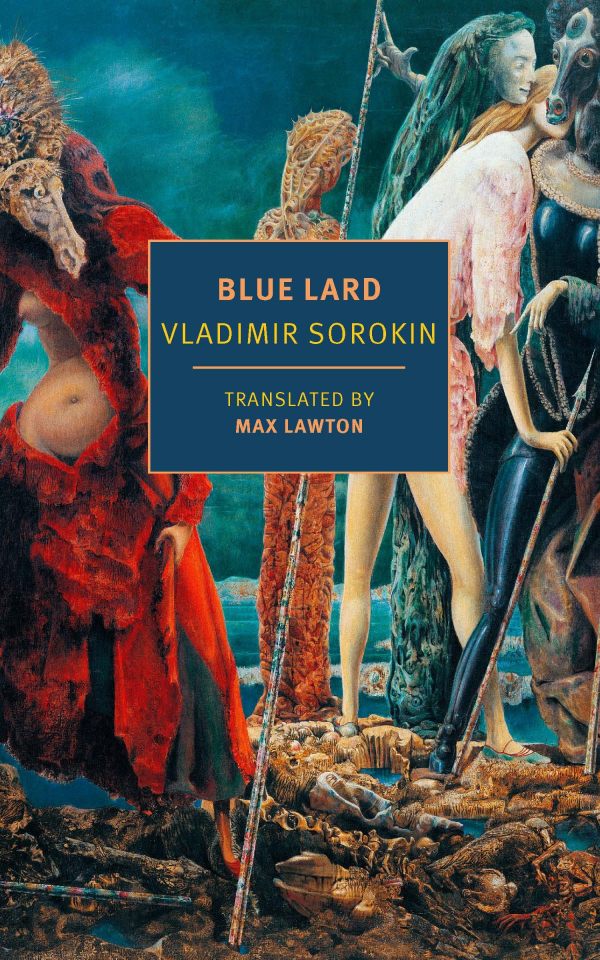

Title: Blue Lard | Author: Vladimir Sorokin | Publisher: NYRB Classics (2024)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog about some recent reading

What an interesting few weeks it’s been! Here’s (some of) what I’ve been reading so far this year: I’m in the middle of Stephen Dixon’s novel Interstate. It is a devastating, ugly, addictive, beautiful novel; I have no idea if it is “good” or not but I love it. I can’t really think of a single person I know (in real life) I could recommend it to. We played cards with some friends and one of them…

View On WordPress

#Art#Blog about#Briana Loewinsohn#Dino Buzzati#Dispatches from the District Committee#Interstate#Jane Bowles#Raised by Ghosts#Remedios Varo#Stephen Dixon#Vladimir Sorokin#Werner Herzog

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

As our Batya says, there are three things you want to look at continuously: fire, the sea, and other people’s work.

Day of the Oprichnik (Vladimir Sorokin)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In Russia, power is a pyramid. This pyramid was built by Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century – an ambitious, brutal tsar overrun by paranoia and a great many other vices. With the help of his personal army – the oprichnina – he cruelly and bloodily divided the Russian state into power and people, friend and foe, and the gap between them became the deepest of moats. His friendship with the Golden Horde convinced him that the only way to rule the hugeness of Russia was by becoming an occupier of this enormous zone. The occupying power had to be strong, cruel, unpredictable and incomprehensible to the people. The people should have no choice but to obey and worship it. And a single person sits at the peak of this dark pyramid, a single person possessing absolute power and a right to all.

Paradoxically, the principle of Russian power hasn’t even remotely changed in the last five centuries. I consider this to be our country’s main tragedy. Our medieval pyramid has stood tall for all that time, its surface changing, but never its fundamental form. And it’s always been a single Russian ruler sitting at its peak: Pyotr I, Nicholas II, Stalin, Brezhnev, Andropov … Today, Putin has been sitting at its peak for more than 20 years. Having broken his promise, he clutches on to his chair with all his might. The Pyramid of Power poisons the ruler with absolute authority. It shoots archaic, medieval vibrations into the ruler and his retinue, seeming to say: “you are the masters of a country whose integrity can only be maintained by violence and cruelty; be as opaque as I am, as cruel and unpredictable, everything is allowed to you, you must call forth shock and awe in your population, the people must not understand you, but they must fear you.”

(…)

Alas, Yeltsin, who came to power on the crest of the wave of perestroika, did not destroy the pyramid’s medieval form; he simply refurbished its surface: instead of gloomy Soviet concrete, it became colorful and was covered over with billboards advertising western goods. The Pyramid of Power exacerbated Yeltsin’s worst traits: he became rude, a bully and an alcoholic. His face turned into a heavy, motionless mask of impudent arrogance. Toward the end of his reign, Yeltsin unleashed a senseless war on to Chechnya when it decided to secede from the Russian Federation. The pyramid built by Ivan the Terrible had succeeded in awakening the imperialist even in Yeltsin, only a short-lived democrat; as a Russian tsar, he sent tanks and bombers into Chechnya, dooming the Chechen people to death and suffering.

Yeltsin and the other creators of perestroika surrounding him not only didn’t destroy the vicious Pyramid of Power, they didn’t bury their Soviet past either – unlike the post-war Germans who buried the corpse of their nazism in the 1950s. The corpse of this monster, which had annihilated tens of millions of its own citizens and thrown its country back 70 years into the past, was propped up in a corner: it’ll rot on its own, they thought. But it turned out not to be dead.

(…)

The Pyramid of Power was vibrating and its vibrations stopped time. Like a huge iceberg, the country was floating through the past – first its Soviet past, then only its medieval past.

Putin declared that the collapse of the USSR was the greatest catastrophe of the 20th century. For all clear-headed Soviet people, its collapse had been a blessing; it was impossible to find a single family unscathed by the red wheel of Stalinist repressions. Millions were annihilated. Tens of millions were poisoned by the fumes of communism – an unattainable goal requiring moral and physical sacrifices by Soviet citizens. But Putin didn’t manage to outgrow the KGB officer inside of him, the officer who’d been taught that the USSR was the greatest hope for the progress of mankind and that the west was an enemy capable only of corruption. Launching his time machine into the past, it was as if he were returning to his Soviet youth, during which he’d been so comfortable. He gradually forced all his subjects to return there as well.

The perversity of the Pyramid of Power lies in the fact that he who sits at its peak broadcasts his psychosomatic condition to the country’s entire population. The ideology of Putinism is quite eclectic; in it, respect for the Soviet lies side by side with feudal ethics, Lenin sharing a bed with Tsarist Russia and Russian Orthodox Christianity.

Putin’s favorite philosopher is Ivan Ilyin – a monarchist, Russian nationalist, anti-Semite, and ideologist of the White movement who was expelled by Lenin from Soviet Russia in 1922 and ended his life in exile. When Hitler came to power in Germany, Ilyin congratulated him hotly for “bringing the Bolshevization of Germany to a halt.

(…)

In his articles, Ilyin hoped that, after the fall of Bolshevism, Russia would have its own great führer, who would bring the country up from its knees. Indeed, “Russia rising from its knees” is the preferred slogan of Putin and of his Putinists. It was also taking his cue from Ilyin that he spoke contemptuously of a Ukrainian state “created by Lenin”. In fact, the independent Ukraine was not created by Lenin, but by the Central Rada in January 1918, immediately after the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly by Lenin. This state arose because of Lenin’s aggression, but not thanks to his efforts. Ilyin was convinced that if, after the Bolsheviks, the authorities in Russia were “[to become] anti-national and anti-state, obsequious toward foreigners, [to dismember] the country, [to become] patriotically unprincipled, not exclusively protecting the interests of the great Russian nation without any regard for whorish Lesser Russians [Ukrainians], to whom Lenin gave statehood, then the revolution [would] not end, but enter its new phase of perishing from western decadence.”

“Under Putin, Russia has gotten up from its knees!” his supporters often chant. Someone once joked: the country got up from its knees, but quickly got down onto all fours: corruption, authoritarianism, bureaucratic arbitrariness and poverty. Now we might add another: war.

A lot has happened in the last 20 years. The president of the Russian Federation’s face has turned into an impenetrable mask, radiating cruelty, anger, and discontent. His main instrument of communication has become lies – lies small and big, naively superficial and highly structured, lies he seems to believe himself and lies he doesn’t. Russians are already accustomed to their president’s lie-filled rhetoric. But, now, he’s also inured Europeans to those lies. Yet another head of a European country flies to the Kremlin so as to listen through their traditional portion of fantastical lies (now at an enormous, totally paranoid table), to nod their head, to say that “the dialogue turned out to be fairly constructive” at a press conference, then to just fly away.

(…)

Putin’s inner monster wasn’t just brought up by our Pyramid of Power and the corrupt Russian elite, to whom Putin, like the tsar to the satraps, throws fat, juicy bits of corruption from his table.

It was also cultivated by the approval of irresponsible western politicians, cynical businessmen and corrupt journalists and political scientists.

(…)

For Putin, life itself has always been a special operation. From the black order of the KGB, he learned not only contempt for “normal” people, always a form of expendable matter for the Soviet Moloch-state, but also the Chekist’s main principle: not a single word of truth. Everything must be hidden away, classified. His personal life, relatives, habits – everything has always been hidden, overgrown with rumors and speculation.

Now, one thing has become clear: with this war, Putin has crossed a line – a red line. The mask is off, the armor of the “enlightened autocrat” has cracked. Now, all westerners who sympathize with the “strong Russian tsar” have to shut up and realize that a full-scale war is being unleashed in 21st century Europe. The aggressor is Putin’s Russia. It will bring nothing but death and destruction to Europe. This war was unleashed by a man corrupted by absolute power, who, in his madness, has decided to redraw the map of our world. If you listen to Putin’s speech announcing a “special operation”, America and Nato are mentioned more than Ukraine. Let us also recall his recent “ultimatum” to Nato. As such, his goal isn’t Ukraine, but western civilization, the hatred for which he lapped up in the black milk he drank from the KGB’s teat.

Who’s to blame? Us. Russians. And we’ll now have to bear this guilt until Putin’s regime collapses. For it surely will collapse and the attack on a free Ukraine is the beginning of the end.

Putinism is doomed because it’s an enemy of freedom and an enemy of democracy. People have finally understood this today. He attacked a free and democratic country precisely because it is a free and democratic country. But he’s the one who is doomed because the world of freedom and democracy is far bigger than his dark and gloomy lair. Doomed because what he wants is a new Middle Ages, corruption, lies and trampling on human freedoms. Because he is the past. And we must do everything in our power to make this monster remain there – in the past – for all time, together with his Pyramid of Power.”

“The Russian president is facing the most serious threat to his hold on power in all the 23 years he’s run the nuclear state. And it is staggering to behold the veneer of total control he has maintained all that time – the ultimate selling point of his autocracy – crumble overnight.

It was both inevitable and impossible. Inevitable, as the mismanagement of the war had meant only a system as homogenously closed and immune to criticism as the Kremlin could survive such a heinous misadventure. And impossible as Putin’s critics simply vanish, or fall out of windows, or are poisoned savagely. Yet now the fifth-largest army in the world is halfway through a weekend in which fratricide – the turning of their guns upon their fellow soldiers – was briefly the only thing that could save the Moscow elite from collapse.

(…)

Much of this sudden resolution is as curious and inexplicable as the crisis it solved. Prigozhin appears – thus far – to have had none of his demands heeded. The top brass of Russia’s defense ministry is still in place. He has done incalculable damage to Putin’s control over the Russian state, and shown how easy it is to take control of the key military city of Rostov-on-Don and then move fast towards the capital. And it took the intervention of Lukashenko, an ally whom Putin treats more as a subordinate than an equal, to engineer an end to this ghastly of weekends for the Kremlin.

(…)

The rage and tension that has been building for months has not suddenly been assuaged. It has instead been accentuated.

So accustomed are we to viewing Putin as a master tactician, that the opening salvos of Prigozhin’s disobedience were at times assessed as a feint – a bid by Putin to keep his generals on edge with a loyal henchman as their outspoken critic. But what we have seen – with Putin forced to admit that Rostov-on-Don, his main military hub, is out of his control – puts paid to any idea that this was managed by the Kremlin.

(…)

Perhaps Prigozhin dreamt he could push Putin into a change at the top of a ministry of defense the Wagner chief has publicly berated for months. But Putin’s address on Saturday morning has eradicated that prospect. This is now an existential choice for Russia’s elite – between the president’s faltering regime, and the dark, mercenary Frankenstein it created to do its dirty work, which has turned on its masters.

(…)

This is not the first time this spring we have seen Moscow look weak. The drone attack on the Kremlin in May must have caused the elite around Putin to question how on earth the capital’s defenses were so weak. Days later, elite country houses were targeted by yet more Ukrainian drones. Among the Russian rich, Friday’s events will remove any question about whether they should doubt Putin’s grip on power.

(…)

As this rare Jacobean drama of Russian basic human frailty plays out, it is not inevitable that improvements will follow. Prigozhin may not prevail, and the foundations of the Kremlin’s control may not ultimately collapse. But a weakened Putin may do irrational things to prove his strength.

He may prove unable to accept the logic of defeat in the coming months on the frontlines in Ukraine. He may be unaware of the depth of discontent among his own armed forces, and lack proper control over their actions. Russia’s position as a responsible nuclear power rests on stability at the top.

A lot more can go wrong than it can go right. But it is impossible to imagine Putin’s regime will ever go back to its previous heights of control from this moment. And it is inevitable that further turmoil and change is ahead.”

“No one should be naive and think that any new Russian leader would automatically be better.

For their part, it is understandable that Ukrainians hope that liberation may be at hand if Russians fall out among themselves. But the chilling truth is that Prigozhin has made it clear that he is rebelling because the aggression against Ukraine has been mismanaged, not because it is a war crime. Prigozhin’s unrestrained brutality means that if he succeeds in bending the Russian state and army to his will, the war against Ukraine could be plunged into new depths of horror.

So far, Putin has used bluster about using nuclear weapons but don’t count on a criminal such as Prigozhin to show restraint. For this is a man who has used a sledgehammer to smash the head of an insubordinate soldier.

Would such a beast bother considering the consequences before unleashing nuclear weapons on the world?

Make no mistake, the fate of Russia’s vast nuclear arsenal is now in play. As bad for Russia and the world as Putin’s regime has been, a new power struggle for control of the Kremlin risks putting the world on the brink of atomic catastrophe. We have never witnessed a civil war inside a nuclear-armed state before.

(…)

Nuclear-armed anarchy is a terrifying prospect. But there is little in practice that the West can do to control the situation.

However much Putin deserves a grim reckoning, those who may yet topple him are even less predictable and self-controlled. Yesterday’s chaos suggests his coming fall would still set in train a worse time of troubles for all of us.”

#vladimir sorokin#sorokin#putin#russia#ukraine#russo ukrainian war#power#yevgeny prigozhin#wagner#russian coup#ivan ilyin#mark almond

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

a few kind listeners who work in bookshops/places that tolerate flyers asked if there's something they can print out and put up to promote the show. The result is below. I would really appreciate anyone who felt like doing this but no pressure at all, ofc. (yes, this is my big year three promo push)

.

also:

#sf ultra podcast#books#literature#sci fi and fantasy#science fiction#weird fiction#art#Tanith Lee#J.G. Ballard#Kathe Koja#Rammellzee#Antoine Volodine#Vladimir Sorokin#Ishmael Reed#Barry Malzberg#Jacqueline Harpman#Anna Kavan#David Ohle#Joanna Russ#Stanisław Lem#Sarah Kane#Ursula K Le Guin#Thomas M Disch#Jody Scott#Alasdair Gray#Flann O'Brien#Katie Jean Shinkle#Christopher Zeischegg#Samuel R Delany#Brian Evenson

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

'Day of the Oprichnik' by Vladimir Sorokin – The Three R's – Raucous, Ribald, and Reckless

‘Day of the Oprichnik’ by Vladimir Sorokin (2006) – 191 pages Translated from the Russian by Jamey Grambrell The year is 2028. Modern Russia has now returned to leadership by an all-powerful Czar who is referred to only as “His Majesty”. The modern Russian leader is much like Russian leaders from the past like Genghis Khan and Ivan IV, also known as Ivan the Terrible. “How glorious it is…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In Russland hat ein neues Expertenzentrum für Bücher durch seine Empfehlungen erreicht, dass der Großverlag Eksmo-AST den jüngsten Roman von Vladimir Sorokin „Das Erbe“ (Nasledie) sowie zwei aus dem Englischen übersetzte Titel, „Ein Zuhause am Ende der Welt“ von Michael Cunningham und „Giovannis Zimmer“ von James Baldwin, nicht mehr verkauft. Das Zentrum, das in die Verlagsvereinigung „Russische Buchunion“ installiert wurde, besteht aus Vertretern der Medienaufsichtsbehörde Roskomnadsor, der offiziösen Russischen Geschichtsgesellschaft und der Militärhistorischen Gesellschaft, der Russisch-Orthodoxen Kirche, der Geistlichen Organisation Russischer Muslime und anderen Gremien. Seine Experten prüfen, ob Buchpublikationen mit der russischen Gesetzgebung konform sind. Im Fall der Romane von Baldwin und Cunningham dürfte die Thematik von Homosexualität Anstoß erregt haben. Bei Sorokin, der in eine dystopische Zukunft Russlands versetzt, werden zudem Gewaltexzesse geschildert, auch an scheinbaren (freilich zwanzig Jahre alten) Kindern.

AST habe um den im vorigen November erschienenen Roman „Das Erbe“ gekämpft, sagt Sorokin der F.A.Z. am Telefon. Der Verlag habe eine unabhängige Expertise in Auftrag geben wollen. Doch ultranationalistische Organisationen wie die militante Kirchenbewegung „Sorok sorokow“ und die Verfolger kritischer Popmusiker von „Ruf des Volkes“ (Sow naroda), aber auch die den Ukrainefeldzug befürwortende Autorin Olga Uskowa hatten AST wegen des Romans denunziert. Das Innenministerium habe auf den Verlagsleiter Druck ausgeübt, dem er sich schließlich beugte, sagt Sorokin. Immerhin sei die Startauflage von 20.000 Exemplaren fast vollständig verkauft.

„Das Erbe“ vollendet eine Trilogie, die mit dem „Schneesturm“ einsetzte, worin ein Arzt sich in einer mittelalterlich-hochtechnologischen russischen Winterlandschaft verirrt, und von dem unlängst auf Deutsch herausgekommenen „Doktor Garin“ mit dessen weiteren Abenteuern fortgesetzt wird. Im dritten Buch ist Russland in Teilregionen zerfallen, wo Riesen und Zwerge mit normalgroßen Menschen koexistieren, ebenso wie archaische Rituale und Orgien mit Gentechnik und Atombomben. Zerfallen ist auch die russische Sprache, die Figuren reden in einer Mischung aus lokalen Dialekten, Neologismen, Archaismen und chinesischen Lehnwörtern. Eine Verbindung der Regionen stiftet ein transsibirischer Panzerzug, der marodierende Partisanen abwehrt, aber Menschen als Treibstoff verbraucht, die im letzten Waggon umgebracht, zuvor aber noch gefoltert werden. Staatssicherheitsleute sortieren die buchstäblich zu verheizenden Renegaten aus, unter ihnen ein Autor satirischer Gedichte. Assoziationen zu gegenwärtigen russischen Repressionen und Gewaltorgien drängen sich auf, auch etwa wenn ein Heizer mit Vorschlaghammer den Unglücklichen die Köpfe zertrümmert. Der Text dürfte sich daher auch der „Russophobie“ schuldig machen.

0 notes

Text

Tw: non consenting pet play,sex as rewards and just masochistic reader

Imagine being kidnapped by makarov and made to be his pet

like you saw something you weren't supposed to and you piqued his interest in some way

that's the only way I see it to be honest

He'll have sex with you as a reward

Probably carve his Initials in your skin with a knife

Maybe he'll have yuri join in too ( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)

your usually Perceived as bad when he's having a moment and you'll be not allowed to touch yourself or anything

(I pictured him having a shock collar for you on those occasions)

He'll probably make you wear a tight black dress no matter what gender

You'll even wear a collar and be forced to call him daddy or master in Russian

It could just be me desperately wanting to be owned or something

#vladimir makarov#cod makarov#vladimir makarov x reader#cod imagines#call of duty x reader#call of duty#yuri sorokin#Cod thirst#Not horangi stuff#my posts

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

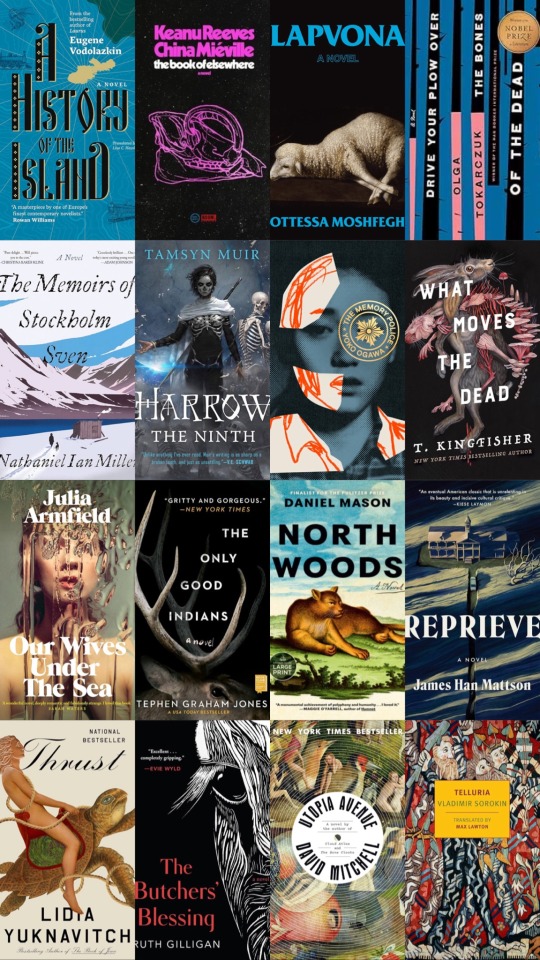

i made this on instagram today and have decided to post it here…. 16 favorite fiction books published (or translated into english!) in the last 5 years. titles under the cut:

a history of the island by eugene vodolazkin

the book of elsewhere by keanu reeves and china miéville

lapvona by ottessa moshfegh

drive your plow over the bones of the dead by olga tokarczuk

the memoirs of stockholm sven by nathaniel ian miller

harrow the ninth by tamsyn muir

the memory police by yoko ogawa

what moves the dead by t kingfisher

our wives under the sea by julia armfield

the only good indians by stephen graham jones

north woods by daniel mason

reprieve by james han masson

thrust by lidia yuknavitch

the butchers’ blessing by ruth gilligan

utopia avenue by david mitchell

telluria by vladimir sorokin

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

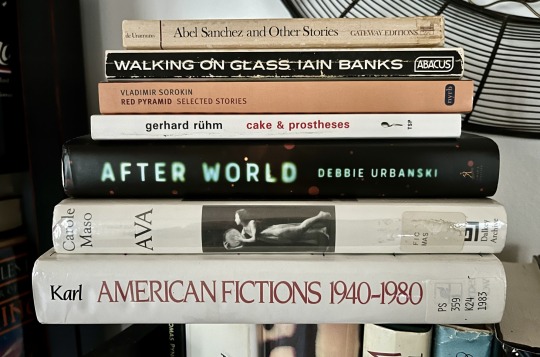

Blog about some recent reading

A few weeks ago, I picked up Anthony Kerrigan’s translation of Miguel de Unamuno’s Abel Sanchez and Other Stories based on its cover and the blurb on its back. I wound up reading the shortest of the three tales, “The Madness of Dr. Montarco,” that night. The story’s plot is somewhat simple: A doctor moves to a new town and resumes his bad habit of writing fiction. He slowly goes insane as his…

View On WordPress

#Carole Masso#Debbie Urbanski#Frederick Karl#Gerhard Rühm#Iain Banks#Max Lawton#Miguel de Unamuno#Vladimir Sorokin

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In short, the SOBs locked themselves in, and Batya forbade us to use fireworks—the house wasn’t in disgrace. Couldn’t use gas or lasers either. So we did things the old way—in the lower quarter: this and that, the enemies are upstairs. We asked them statesmanlike, officially, they came out with suitcases and icons, we singed them, began to smoke the upstairs ones out. We thought they’d open up, but they jumped out the window. The elder landed on the fence—the spike went straight through his liver—the younger broke his leg but survived, and then he gave evidence…”

Day of the Oprichnik (Vladimir Sorokin)

#Day of the Oprichnik#Vladimir Sorokin#books#quotes#dictatorship#V#Seeing Grishaverse in other works#because if the Darkling should've been a tyrant#why not write ~his~ oprichniki like this?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyiv Independent's WTF is wrong with Russia? - Thursday, November 14, 2024

On Nov. 12, the Russian parliament voted to ban "childfree propaganda" in the latest wave of government-sponsored restrictions.

The sole exception, at the request of the Russian Orthodox Church, was made for monks, who are allowed to promote celibacy. Everyone else in Russia now must want to have children or pay a fine if they don't.

Hi, my name is Oleksiy Sorokin, I'm the deputy chief editor of the Kyiv Independent, and this is the latest issue of our Russia-themed newsletter.

Today we will talk about why the Russian government continues to impose additional restrictions on a population that for the most part agrees with its policies and has little to no desire to oppose the regime.

According to the new legislation, still formally requiring the signature of Russian President Vladimir Putin, speaking in support of not having children is a misdemeanor that will result in a hefty fine.

It's now illegal in Russia to say that you don't want kids, and it's illegal to advertise it online in any way and form, which also effectively bans any promotion and advertising of contraceptives. The right to abortion is now also put into question.

For an individual, the fine will be up to $4,000; for an official, the sum rises to $8,000, while the fine for businesses can hit up to $50,000 and get the company's license revoked for 90 days.

You must want to have kids if you are in Russia. Or become a monk.

In Russia, 8.5% of the population is living below the poverty line, while the minimum wage is $220. The lack of financial means isn't an excuse to have kids. Medical conditions are also irrelevant in this case — if you risk giving birth to an unhealthy child or your life is at risk, this can't be an excuse for not wanting to try.

In our recent story on this issue, Dr. Valerie Sperling, professor of political science at Clark University in Massachusetts, asked the same question I was asking when I first heard of this initiative — "The law is striking in the sense that it seems so completely unnecessary; it seems like a response to something that doesn't really exist," Sperling said.

The ban on expression and the state-sponsored attacks on certain groups of people had been ongoing in Russia for over a decade, accelerating since the start of the country's full-scale war against Ukraine.

In November 2023, the Russian Supreme Court imposed a ban on what it described as "the international LGBT movement,” labeling it as an "extremist organization." The ruling effectively outlawed the LGBTQ+ community and any visual representation of such, including the pride flag, public showing of affection between people of the same sex, and so on.

Since then, being homosexual has been de facto illegal in Russia, with people persecuted for holding hands, kissing, and even living together.

In the Chechen Republic, led by warlord Ramzan Kadyrov, the LGBTQ+ community is hunted down, tortured, and, in some instances, killed. We had an entire newsletter on the inhumane brutality that is taking place in contemporary Chechnya.

Russians themselves are helping the state to persecute those who the state sees as undesirable. According to a June report from the IStories media outlet, Russians wrote at least 3,500 denunciations since the start of the all-out war. The media outlet says it's a conservative estimate based on data available online.

So why does this happen? Why does the state continue to impose new restrictions on the passive population? And why do people take it a step further and help the restrictive state do more damage?

In the Oct. 3 edition of this newsletter, we spoke about the accelerating spiral of repression. If you take away the rights and freedoms and impose tight control over the population, any decrease in restrictions may be seen as a sign of weakness, thus, a need to impose new restrictions on a regular basis seems like the most logical step for the regime.

Minorities, unprotected, and secluded groups are usually the primary targets. Such attacks are meant to create a common enemy that will tie the disenfranchised population closer to the ruling class.

Have you noticed that autocrats and strongmen often use hate as the main appeal?

It's usually “us against them,” and it's “them that are guilty of our own misfortunes.”

Contemporary Russia is fighting "Americans and the collective West" and their "imposed values" represented, according to the Kremlin, by LGBTQ+, multiculturalism, and people who don’t want children. By blaming everyone else for the country's own faults, the government shifts the dissatisfaction onto those who don't have a say.

Absurd? Yes. Does it work? Yes.

If you are barely making ends meet, if your life is hard (for any given reason) — it's someone else's fault.

Russian propaganda was successful in shifting the blame for the country's problems onto the "evil West," while people in Russia are themselves successfully shifting the blame for their problems onto "foreign agents," "homosexuals," and everyone else.

A popular meme in the 2010s was that then-U.S. President Barack Obama was responsible for the bad smell in Soviet apartment buildings that no one dared to clean. The meme was meant to ridicule the overall notion that the West is somehow responsible for the streets being dirty, public transportation being old and having a bad smell, and local officials taking bribes.

Yet, many in Russia do believe "it's Obama's fault."

This also creates a window of opportunity. If there's a common enemy, attacking this enemy might improve your social standing and earn you benefits otherwise out of reach.

In 1963, historian Hannah Arendt wrote the book — Eichmann in Jerusalem — which followed the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi war criminal who oversaw the execution of the Holocaust.

Eichmann was abducted from Argentina, where he was hiding, brought to Israel, and tried for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and membership in a criminal organization. He was found guilty on all 15 counts and hanged in June 1962.

Arendt, who was present at the trial, coined the term "the banality of evil." The term referred to the fact that, according to Holocaust survivor Arendt, Eichmann wasn't evil, he was spineless. He saw joining the Nazi Party (NSDAP) as a career development, and he took on more work as his career progressed. Murdering innocent people en masse in gas chambers was a mundane job for Eichmann.

"Eichmann obeyed orders," "Eichmann obeyed the law."

Millions of Russians work 9 to 5 jobs, watch movies or sports on TV, kiss their loved ones goodnight, then write or call the police to tell them that their neighbor or colleague at work has a pride flag or told them in a private conversation that he or she doesn't want children.

They effectively make the lives of some people miserable, but "they are simply following the law."

12 notes

·

View notes