#tropical forest arthropods

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Cozy Up to the Madagascar Hissing Cockroach

One of twenty hissing cockroach species, the Madagascar hissing cockroach or simply the hisser (Gromphadorhina portentosa) is found only on the island of Madagascar. There, it prefers the dry leaf litter and rotting logs of lowland tropical rainforests, though it can also be found in cool, damp, dark areas of buildings. These habitats are ideal as they can offer both refuge from predators like rodents and birds, and food: hissing cockroaches are detritovores, feeding exclusively on decaying plant and animal matter. This makes them important members of the ecosystem as they recycle nutrients back into the soil.

G. portentosa is one of the largest species of cockroach in the world, reaching up to 7 cm (3 in) and 24 g (0.8 oz) when fully grown. Unlike other cockroaches, the hisser lacks wings and travels exclusively over the ground. Fortunately their hard, dark brown exoskeleton provides excellent camoflage against the forest floor. Males and females are nearly identical; the only difference is the pair of horns, or pronatal humps, found just behind the male’s head.

Though they may live in close quarters, madagascar hissing cockroaches are largely individualistic. Males fiercely guard small territories, only leaving occasionally to find food and water. Females and young are somewhat more social, and move in and out of these territories freely. As their name implies, hissers communicate primarily by hissing. This sound is produced by expelling air through their bodies. Four distinct hisses have been identified, each with different meanings; territorial displays, mating calls, and an alarm hiss to warn away predators.

Hissers reproduce all year round, provided the weather is warm enough. Males attract females by hissing loudly, and fight off rival males through hissing competitions and posturing. When a female enters a male’s territory, she emits a chemical to attract a mate. When the pair meet, they enter a brief courtship ritual involving vocalizations and touching each other’s antennae; they then position themselves end to end and remain there for upwards of 30 minutes.

The female will carry her fertilized egg case, or ootheca, for about two months. Up to 40 nymphs will hatch from the case while still inside their mother, who then expells her young all at once. These nymphs resemble adults in structure, but are smaller and lack reproductive organs. Initially they are white, but quickly turn brown or black as they grow, molting about once a month until fully grown. Sexual maturity is reached at about seven months of age, but individuals can live for up to 5 years.

Conservation status: The Madagascar hissing cockroach has not been evaluated by the IUCN, and populations are considered to be stable. In addition, many zoos and private collectors maintain hissing cockroaches for display or food for other animals, as the species is low maintenence and easy to breed in captivity.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

Liz West

Lincoln Park Zoo

Alexandria Zoo

#madagascar hissing cockroach#Blattodea#Blaberidae#hissing cockroaches#cockroaches#insects#arthropods#tropical forests#tropical forest arthropods#tropical rainforests#tropical rainforest arthropods#africa#madagascar#biology#zoology#animal facts

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coconut crabs are extraordinary creatures that inhabit tropical islands across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, captivating researcher with their impressive size and unique behaviors. Known as the largest land-dwelling arthropods on Earth, these crustaceans play a crucial ecological role in their island habitats, despite their intimidating reputation.

One of the most striking features of coconut crabs is their immense size. Adult specimens can weigh up to 4 kilograms (9 pounds) and measure over 1 meter (3 feet) in length from leg to leg. This substantial size enables them to dominate their environment, including climbing trees to hunt for food and find shelter.

Coconut crabs are renowned for their remarkable ability to crack open coconuts with their powerful pincers. This feat, which requires immense strength and dexterity, allows them to access the nutritious meat inside the coconut, making them well-adapted scavengers in their coastal and forested habitats. Beyond coconuts, they have been observed feeding on a variety of foods, including fruits, nuts, and even carrion.

Despite their predominantly herbivorous diet, coconut crabs have earned a fearsome reputation for their occasional predatory behavior. They have been documented climbing trees to capture and consume seabird chicks and even small rodents, showcasing their opportunistic feeding habits and adaptability in resource-scarce environments.

665 notes

·

View notes

Text

the orange-throated sunangel is a member of the hummingbird family found solely in venezuela and colombia. known for their bright orange throat (which is more reddish-brown in females), this sunangel is a sedentary species often found in tropical or subtropical forest. like other hummingbirds, they primarily feed on nectar, but they will also feed on small insects and arthropods.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

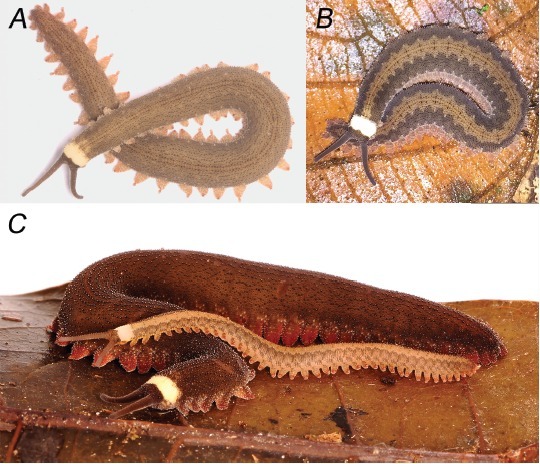

Oroperipatus tiputini: A new species of Velvet Worm from the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Velvet Worms, Onychophora, are a unique group of elongate, soft bodied, many legged Animals, given phylum status and considered to be among the closest living relatives to the Arthropods. They are currently the only known phylum of Animals known entirely from terrestrial species, both living and fossil, although they may be related to the Lobopodans, an entirely marine group known only from Early Palaeozoic fossils. The 230 living Velvet Worm species are divided into two groups, the Peripatidae, found in the tropics of Central and South America, the Antilles Islands, Gabon, India, and Southeast Asia, and the Peripatopsidae, found in Chile, South Africa, Papua New Guinea, Australia, and New Zealand. All South American members of the Peripatidae are placed within a single clade, the Neopatida, which is further divided into two lineages, the 'Andean' genus Oroperipatus, and the 'Caribbean' lineage, comprising all other genera. Read the paper: (https://zse.pensoft.net/article/117952/) The new species is described from five male, three female, and three juvenile specimens collected in the vacinity of the Tiputini Biodiversity Station of the Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Orellana Province, Ecuador, between 2001 and 2023, as well as one youngling, which one of the female specimens gave birth to in captivity. The new species is named Oroperipatus tiputini, in reference to the location where it was discovered. Adult female specimens of Oroperipatus tiputini very between 46 and 65.3 mm in length, while the adult males are smaller at 22.7 to 39.8 mm. Females have between 37 and 40 pairs of legs, while the males have between 34 and 37, although one male specimen had a different number of legs on each side, with 35 legs on the right and 36 legs on the left. The species shows considable colour variation, with one adult male being a light brown colour with a faint rhomboid pattern, two adult males and one adult female being brown with orange diamonds, and another female (the one which produced a youngling) being a plain dark orange colour. The youngling itself was yellowish with a diamond pattern. All specimens were darked on their heads and antenae, had orange or brown legs, and a distinctive white band on the head. Most specimens of Oroperipatus tiputini were found on small herbaceous Plants within old growth, closed canopy upland forests around the Tiputini Biodiversity Station. Other specimens were found in leaf litter, or on the butress roots of trees to a height of about 70 cm above the ground. One specimen was found in a Bromiliad. The Worms were more active at night.

IMAGE: Colour variation in the life of Oroperipatus tiputini. (A) Adult male paratype, ZSFQ-i8270; (B) adult male paratype, ZSFQ-i5151; (C) adult female holotype, ZSFQ-i8248, and youngling paratype, ZSFQ-17794, a few days after being born. All photographs were taken at the Tiputini Biodiversity Station. Photographs by Pedro Peñaherrera (A), (C) and Diego Cisneros-Heredia (B).

299 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lepidopterans, the insect clade including butterflies and moths, were among the invertebrate species seeded onto the planet's biome, in order to act as pollinators that allowed the numerous introduced plants to survive. While most of them adhered to this lifestyle and ecological niche, as ravenous leaf-eaters that metamorphosed into flying pollinators, a few began to experiment with more unconventional lifestyles.

Some of the stranger kinds included the caterpedes: a group of neotenic species that matured simply as larger larvae and skip metamorphosis altogether: filling niches as forest floor detritivores, folivores or occasionally even predators of other insects. And perhaps more unusual are the clade known as the Hemimetamorpha, or "half-changed", which do pupate and emerge as adults with proboscises: yet retain their silk glands ejecting silk through a spinneret located directly below the proboscis and between the labial palps, allowing them to construct nests or wrap their eggs in silk sacs for protection.

Many of the Hemimetamorpha do not develop wings, and instead, thanks to their piercing and sucking mouthparts, fill the niches of true bugs on Earth: as sap-suckers akin to aphids, leafhoppers or cicadas, predators of small arthropods, or even as as flea-like parasites on larger animals. And in the case of one clade, the spooders, they use their retained silk glands to spin webs to catch their prey, in a manner akin to their arachnid namesake.

The red-spotted skeeter (Arachnopapilo rubrum) is one widespread Middle Temperocene species, ranging well across the tropics and temperate zones of Gestaltia and Arcuterra. Despite appearances, it sports two ocelli, one next to each compound eye, large feathery antennae possessing olfactory receptors, and a proboscis, albeit a short, sharp one rather than the long, coiled ones of nectar-feeders, all of which mark its lepidopteran ancestry despite the otherwise lack of resemblance to them.

Female red-spotted skeeters spin webs among grasses and branches, waiting to ensnare flying insects that they then immobilize with digestive enzymes in their saliva, while males are smaller and nomadic, instead hunting by pouncing on their prey and traveling across larger areas of territory compared to the more sedentary females who prefer to stay in their webs. They are also more brightly colored, in order to entice a mate, as the larger female is not above preying upon a suitor she does not like, though occasionally, a male may resort to restraining a female with his own silk, immobilizing her long enough to successfully mate and fleeing before she escapes.

Once mated, the female wraps her eggs into a silk pouch, searches out a safe place with plenty of food, and leaves the egg sac there to develop with no further intervention. The young hatch out as fairly typical caterpillars, yet are carnivores like the adults, tracking down and ambushing other small insects, in particular ants due to their foraging trails being a reliable source of food that comes to them as they lie in wait, as well as their toxic compounds being sequestered by the larva for its own defense. With a nutritious protein-rich diet, the larva matures faster than a leaf-eating caterpillar, and is ready to pupate within a week or two, producing a camouflaged chrysalis that is attached to branches and stems and further disguised by bands of silk. After another 5-7 days it emerges as an adult, and is immediately ready to hunt for a meal within minutes, being wingless and thus bypassing the long vulnerable phase of waiting of their wings to unfold. Within the span of a month, another generation is fully-fledged and ready to breed: a rapid turnover vital for a species with high mortality rates and many enemies-- including members of its own species in both their larval and adult forms.

------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#species profile

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Velvet Worms!

Velvet worms, also known as Onychophora, are fascinating and unique creatures.

Ancient Lineage: Velvet worms are considered "living fossils" and have been around for about 500 million years, surviving from the time of the early Cambrian period.

Soft, Velvety Appearance: They are named for the velvety texture of their skin, which is covered in fine, hair-like structures called setae. These give them their soft, often glistening appearance.

Arthropod Relatives:They share common ancestry with the ancestors of arthropods.

Habitat: They are typically found in moist environments like leaf litter, forest floors, and under rocks. They are mainly tropical or subtropical but can also be found in temperate regions.

Carnivorous Diet: Velvet worms are predatory and feed on small invertebrates. They capture their prey by ejecting a sticky, mucous-like substance from specialized glands, which entangles the prey, making it easier to consume.

Unique Locomotion:Velvet worms move slowly and deliberately, using their many, stubby legs (usually 13–43 pairs) to crawl along surfaces. They have a unique form of locomotion, described as "loping," which is different from other arthropods.

Reproduction: Velvet worms reproduce sexually, and some species exhibit interesting forms of parental care. For example, some mothers carry their young on their backs until they are old enough to fend for themselves.

Excretion: Velvet worms excrete waste through small openings on their underside, and their waste can provide important nutrients for the ecosystem.

Resilient Survivors: Despite their delicate appearance, velvet worms can survive harsh conditions like desiccation. In extreme dryness, they can enter a state of dormancy, allowing them to endure until conditions improve.

Global Distribution: There are around 200 species of velvet worms, distributed in regions around the world, particularly in rainforests, but they are more common in areas with high humidity.

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I saw you have an inbox for arthropod suggestions so here's mine: Typhochlaena seladonia.

Top left: "Brazilian jewel tarantula (Typhochlaena seladonia) is a species of aviculariine tarantula. They are found in Bahia and Sergipe, Brazil in rainforest parts. It is unique as an arboreal spider that constructs trapdoors in the bark of trees. Doesn't really like human contact much. They are generally more docile, although some individuals are particularly defensive."

Top middle: "Purple pink toe or purple tree tarantula (Avicularia purpurea) are mainly present in Ecuador in the Amazon Region. This species can be found in very different habitats, but frequently it is present in agricultural areas, especially in the field of grazing cattle. Sometimes it can be found in holes of walls of buildings or in the spaces below the roofs. They builds their nests primarily in hollows in the trees, sometimes in the vicinity of epiphytic plants. They eat mostly crickets, cockroaches, meal worms, waxworms and darkling beetles, but they also can catch small rodents."

Top right: "Trinidad dwarf tiger (Cyriocosmus elegans) is a New World Terrestrial Tarantula that comes from the tropical climates of Trinidad, Tobago and Venezuela. They are venomous. Also, due to being a such a small tarantula, females have an average lifespan of around 7 years while males tend to only live about 2 years."

Down left: Golden Brown Baboon Spider "Augacephalus breyeri is a species of harpactirine theraphosid spider, found in South Africa, Mozambique and Eswatini. They live in a hole that takes it between five to seven years to construct. They feed on a variety of small invertebrates such as beetles, grasshoppers, millipedes, cockroaches, crickets, and other spiders!"

Down right: "Gooty Sapphire Ornamental Tarantula (Poecilotheria metallica) also known as the peacock tarantula, is an Old World species of tarantula. This is the only blue species of the genus Poecilotheria. Like others in its genus it exhibits an intricate fractal-like pattern on the abdomen. The species' natural habitat is deciduous forest in Andhra Pradesh, in central southern India. They live in holes of tall trees where it makes asymmetric funnel webs. The primary prey consists of various flying insects."

Here's some more tarantula for you guys! Also from now on every species I make will have short description about em. Thank you for suggestion!

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bird of the Week: the Kaua’i ō’ō! 🪶

The kaua’i ō’ō (Moho braccatus), was a member of the Mohoidae family of honeyeaters. These birds, along with the rest of the Mohoidae family, are now extinct. The last recorded sighting of the kaua’i ō’ō was in 1987 by David Boyton. They would be officially declared extinct in 2000.

The cause of their extinction was due to multiple factors. Primarily, human impact played a huge role in their disappearance by causing habitat loss and introducing invasive species. Disease (avian malaria) and tropical storms also played a part in the extinction of the Mohoidae family.

The kaua’i ō’ō was found through forested areas of the island of Kaua’i, Hawaii. Here, they feed upon nectar, seeds, flower bracts and small invertebrates such as arthropods.

These birds were known for their highly territorial behavior; they could once be observed chasing after other bird species that breached their territories.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fish of the Day

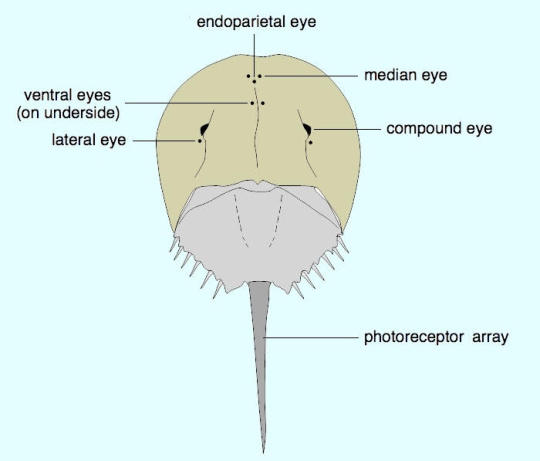

Today's fish of the day is the mangrove horseshoe crab!

The mangrove horseshoe crab, also known as the round-tailed horseshoe crab, and scientific name Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda is one of the four living species of horseshoe crab remaining. The mangrove Horseshoe crab is closely related to the other 2 Asian horseshoe crabs: The Indo-Pacific Horseshoe crab (Tachypleus gigas), and the Chinese Horseshoe crab (Tachypleus tridentatus), but is the only member of the Carcinoscorpius genus. These three horseshoe crabs are separate from the American Atlantic Horseshoe crab, which separated between 130 to 400 million years ago! Now, Horseshoe crabs are horribly named, as they're not crabs at all. Instead, they belong to subphylum Chelicerata, which is in the Arthropod phylum, directly relating them to spiders and ticks.

Like its name implies, the mangrove horseshoe crab lives in brackish waters in mangrove forests. They can be found across Southeastern Asia, down to the Indo-Pacific in Tropical and subtropical climates. This animal spends its time in shallow waters, preferring sandy areas. The mangrove Horseshoe is benthopelagic, meaning it lives its life on the seafloor, and although they rarely do so, horseshoe crabs can swim, albeit, upside down. I'd recommend looking up a video on them swimming, it's very cool to see!

As benthic creatures, the mangrove horseshoe crabs diet is limited to what it can find on the seabed. Not only that, but, like all parts of the Chelicerata subphylum, it lacks jaws and teeth, and so it must feed in another method. Horseshoe crabs eat by grabbing prey with chelicerae, a pair of appendages in front of its legs, and passing prey to a food grove that runs from the furthest back legs, and up to the mouth. Well in the food grove, the bases of the legs are used to grind prey with teeth like structures, simultaneously passing further forward. Due to horseshoe crabs being so unchanged over the years, it is thought that this feeding method may have belonged to some of the earliest Arthropods. The diet of the mangrove horseshoe crab in particular is made up of insect larvae, small fish, marine worms, and mollusks. Although mangrove horseshoe crabs in particular have a strong preference for insect larvae above other prey.

Anatomically horseshoe crabs get stranger yet. They contain 10 eyes: 2 compound eyes, which can be seen on the top of the head, used primarily for finding mates. Then, there is a pair of lateral eyes, on the underside, ventral eyes, used for finding prey, an endoparetial eye, and median eyes. Horseshoe crabs can see both visible and ultraviolet light, but are particularly sensitive to light amounts and changes in their surroundings. The tail, as opposed to some common thought, is not poisonous or a weapon, but rather it is used for flipping over easily, and some movement well swimming. In Mangrove horseshoe crabs the tail is far more rounded than its relatives.

Have a good day everyone!

#fish of the day#mangrove horseshoe crab#horseshoe crab#carcinoscorpius rotundicauda#fish#fishblr#crab#arthropod

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Driophlox Scott et al., 2024 (new genus)

(An individual of Driophlox gutturalis, photographed by Christoph Moning, under CC BY 4.0)

Meaning of name: Driophlox = thicket flame [in Greek]

Species included: D. gutturalis (sooty ant tanager, type species, previously in Habia), D. atrimaxillaris (black-cheeked ant tanager, previously in Habia), D. cristata (crested ant tanager, previously in Habia), and D. fuscicauda (red-throated ant tanager, previously in Habia)

Age: Holocene (Meghalayan), extant

Where found: Forest undergrowth in Middle and South America

Notes: The name "ant tanager" is used for several species of tropical songbirds closely related to cardinals. Despite often being brightly colored, they are generally secretive. They feed primarily on insects and some fruits, and as their common name suggests, are known to occasionally follow swarms of army ants to capture fleeing arthropods.

Current taxonomic authorities classify all of the ant tanagers in the genus Habia. However, recent genetic studies have found that the red-crowned ant tanager (Habia rubica) is more closely related to the genus Chlorothraupis than to other ant tanagers. Given that H. rubica is the type species of Habia, a new genus is needed for the other ant tanagers, so the authors of a new paper coin the name Driophlox for this purpose.

Reference: Scott, B.F., R.T. Chesser, P. Unitt, and K.J. Burns. 2024. Driophlox, a new genus of cardinalid (Aves: Passeriformes: Cardinalidae). Zootaxa 5406: 497–500. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.5406.3.11

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Worst Ant Video on the Internet

I did it. I found the worst ant video on youTube. I'm not going to link to it because it's *so* bad that I can't rule out the very real possibility that someone made it this bad just to bait people into watching it. But, let me give you a little taste of the horror. The calamity starts with the title:

"Most Dangerous Ant Spices"

Yes. "Spices."

Dangerous ant spices? Are we talking tarragon and cumin? Are these spices dangerous to ants? Or is this a warning about the dangers of ant cooking?

The spelling error is bad enough, but also the whole concept of such a list is a little... gauche? Why is there this idea that the only thing that makes insects interesting is thinking about how much they could kill you?

But-- even this I could excuse. After all there are a few ants with dangerous stings. But, what do you think is on the list? Do you want to know? Too bad I'm telling you anyways:

10. Harvester ant (This ant has a sting as bad as a bee. So, not a terrible entry for the bottom of this list...But the photo they used)

That is NOT a harvester ant. That is a weaver ant, genus Oecophylla. Weaver ants are tropical and use silk to make their nests in trees. Harvester ants are from the families Pogonomyrmecini and Stenammini, these are desert-dwelling ants who collect seeds and live underground. They don't even look alike at all. They do both have a sting, that's about as bad as a bee sting.

Maybe the next ant on the list will be better...? (of course not)

9. Redwood ant (What did wood ants do to deserve this??)

I don't even know what ant they meant by this. They showed an image of Formica rufa, the wood ant, and rufa do have a reddish color ... so maybe they are also called "redwood ants" But, why are these ants on a list of "Dangerous Ants" ?? They are a protected species that lives in the pine forests of Europe! They don't sting and can't even effectively bite a person. Their colonies are huge. They build mound nests of pine needles a meter in height and live in groups of 100s of thousands. They are gentle custodians of the forest enriching the soil and keeping the arthropod populations under-control. Beneficial ants that are so well loved they are protected from poaching since without them the forests would not thrive as well.

8. Odorous house ant (lol what?)

A few years back there was a recurring argument online about if ants have a smell. People who grew up in areas with the odorous house ant know that some ants, when crushed smell like coconut... or rotten face cream. The smell isn't exactly overwhelming and it's only around when the ants are crushed or injured. But it's very distinctive nothing is exactly like it. Most ants have no real smell. So people argued about this online.

But other than the smell there isn't much to say about these little ants. They are tiny, can't sting, can't bite. They can be house pests. So they are dangerous to your poptarts. Might smell a little odd for a few moments if you step on one. If this is "Dangerous" I don't even know.

7. Leafcutter ant

These ants are remarkable but they can't sting, they do have a powerful bite so I guess that's a little "dangerous" ... the majors could draw blood biting you. And they can defoliate a tree overnight ... so that's kinda ... "dangerous" ... at least they used the correct image.

6. Argentine ant

(is this a list of ants... most dangerous to other ants?)

Another ant that can't sting or bite. Linepithema humile is an invasive species and a huge threat to ant diversity in some parts of the world. This makes it even more unfortunate that the video, like many "resources" online used the incorrect photo for this ant. If you search for this ant with the common name "Argentine Ant" you will probably find a photo of another species incorrectly identified as an Argentine ant-- and, since it's invasive, incorrectly identifying one of your local beneficial species of ant as Argentine could lead to killing off the wrong ants. So. I edited this photo as it's not just misinformation... it is destructive misinformation.

Neither the ant in the photo, nor Linepithema humile are in any way "dangerous" except for the danger posed to native ants.

5. Carpenter ant (YES every single one!)

They did at least use a photo of one of the thousands of carpenter ants (Genus Camponotus) for this one. But that doesn't make up for labeling a harmless Campontus as an invasive in the last list item.

None of the Carpenter ants can sting or be dangerous. Some have a significant bite, but not as bad as the leafcutter ants lower on this list.

4. African ant (You aren't even trying anymore.)

I've decided making up something called an "African ant" putting it on a list of "dangerous ants" then using a photo of a trapjaw ant (Odontomachus speceis) that isn't even from Africa is probably racist ... somehow.

I think they meant to show the most famous ants from Africa, the driver ants. (Genus Dorylus) This is a genus of army ant that roves through the forests in columns of thousands. Their majors look vaguely like trap jaw ants. And they are a little "dangerous" ... though they are also well-loved since they will clean your home and land of pests.

3. Red fire ant (Guess what the photo showed. GUESS.)

Oh. NOW they show a harvester ant. I think that people don't think that real fire ants look as formidable as their reputation. So they use photos of the larger more beefy looking harvester ant instead. The common name "fire ant" refers to Solenopsis invicta, and invasive species with the ability to sting.

The sting of one fire ant isn't much... but they sting in great numbers and can be a problem. But this photo is a harvester ant, which is a much larger ant and beneficial. Harvester ants also sting. This may be why these ants are so often confused.

They had correct images for the last two items in their list. And both of these ants have significant stings and bites. That said neither is hunting humans for food or planning to take over your school board and ban books or anything.

2. Bulldog ant 1. Bullet ant

List is hot mess.

#ants#antposting#bugblr#bugs#insects#ant#invertebrates#myrmecology#antblr#antkeeping#pedantry#mistakes#misinformation#ant misinformation#insect identification#identification#bug identification#top ten#top ten list#tiktok

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grab A Drink with the Asian Tiger Mosquito

As its name implies, Aedes albopictus, also known as the forest mosquito, is endemic to Southeast Asia, where it thrives in the humid tropics and subtropics. There, and in similar regions, this species is active year-round. Where it has been introduced in more temperate regions, the tiger mosquito is only active during the warmer months of the year. Currently it is found on every continent except Antarctica, spread unintentionally by humans throughout the globe.

The Asian tiger mosquito is among the smaller mosquito species, at only 10 mm (0.39 in) long at the maximum. Males are typically smaller than females, and have much bushier antennae, as well as functional auditory receptors. Conversely, females have a longer probiscus Otherwise, the two sexes are largely similar; both have black bodies with white markings along the abdomen and legs. Like all mosquitos, the forest mosquito has two sets of wings, but they aren't very good fliers and rarely stray more than 500 m (0.3 miles) from their breeding grounds.

As with other parasitic mosquito species, only the female feeds on blood. Female forest mosquitos are generalists, in that they can feed on both mammals and birds. In addition, they will also consume nectar and sap along with the males. Females seek out their hosts using their antennae, which carry receptors for carbon dioxide as well as scent and humidity. Both sexes are active mainly during the day, but will hunt and forage at night as well given ample opportunity. This species is also an important food source for many other animals, especially when they're in their larval phase. As adults, bats and birds are their primary predators.

Forest mosquito females only feed on blood when they are in the egg-production phase of their reproductive cycle. They can mate up to four times, producing over 200 eggs over their lifespan,although those in temperate regions have a shorter reproductive period. When they're ready to mate, males will form large swarms, or leks, a few feet above the ground. This attracts females, whose wingbeats produce an audible buzz that males can pick up and hone in on. Males and females mate while in flight, and once they've finished the female departs to lay her eggs in a stagnant or slow-moving body of water.

On average eggs take about 7-10 days to hatch, though some clutches may take up to a month. Once they hatch, the larvae feed on small bits of detritus and bacteria, while developing through four stages of growth called instars. The time this process takes is also variable, ranging from 4 days to 42. At the end, the larvae forms a pupa, from which it emerges 2 days later as a mature adult.

Conservation status: This species has not been evaluated by the IUCN; however, given their large population and adaptability, they are considered stable in their home range. In other parts of the world where they've been introduced, they are considered a pest species both for their irritating bites and their role as disease carriers.

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip or buying me a ko-fi!

Photos

James Gathany via Wikipedia

James Gathany

Ary Farajollahi

#Asian tiger mosquito#Diptera#Culicidae#mosquitoes#flies#insects#arthropods#tropical forests#tropical forest arthropods#tropical rainforests#tropical rainforest arthropods#generalist fauna#generalist arthropods#asia#southeast asia

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's bug: Tailless whip scorpion!

Sorry I haven't been active for so long.. anyways I got a new pet today - this female tailless whip scorpion (likely Phrynus whitei), so I'll tell you about them!

Tailless whip scorpions are arachnids in the Order Amblypygi (am-BLIP-idge-eye) and they're quite ancient! They even look a bit prehistoric, I think. There's about 150 species of tailless whip scorpion.

Adapted for crawling around dark forests and cave walls, these arthropods are nearly blind - their simple eyes giving them only vague information, like the level of surrounding light. That's where their loooong 2nd pair of legs come in!

(image source: Wikimedia)

See those long "whips" from which they get their name? Those are for feeling their surroundings. When active, they'll be constantly moving around them around to sense their environment. The whips are very fragile and can break easily, but can be regrown every molt!

(image source: Frank Deschandol on iNaturalist)

Tailless whip scorpions are NOT scorpions, nor are they spiders. And those terrifying front claws aren't legs either - they're heavily modified mouthparts, pedipalps to be precise. Speaking of scorpions, their grabby claws are also their pedipalps! In spiders, these are those cute little appendages right next to the chelicerae (the things that have the fangs).

Unlike both scorpions and spiders, however, a tailless whip scorpion cannot bite or sting. They're almost totally harmless! Practically the posterchild for "don't judge a book by its cover," these are some of the friendliest arachnids in the world. You have to seriously to make one angry (which is basically abuse, so don't do that), and even then they'll only try smacking you with their thorny pedipalps, never biting with their fangs.

About the only truly scary part of handling them (once you get past their appearance) is their speed. These things normally move very slowly (on account of the "blind and has to touch everything" thing), but if startled, they'll bolt in the opposite direction with incredible speed! They really, really would rather not confront you at all. I cannot emphasize enough how completely NOT dangerous these arachnids are, despite their look!

(image source: Jonathan's Jungle Roadshow)

Btw, did you know the mommas make great parents? Like many other large arachnids, the mothers will take their young with them until they're large enough to hunt on their own. They hatch from an egg pouch carried on the underside of the abdomen, which looks absolutely alien - in the source for the above image, you can find pictures of the whole process.

You may have seen this meme ^ Their pedipalps, usually folded up, can also unfold to catch prey or defend themselves (in the original video for this pic, the owner is provoking this reaction - something I don't condone, even if it showcases their grab ability very well). Tailless whip scorpions are carnivores, and the prey they catch are usually small insects like crickets or flies.

Tailless whip scorpions are found in almost every warm, tropical part of the world - Central/South America, Africa, Asia, and even some islands like the Phillipines!

Here's my t.w.s.' habitat. They're very easy pets to take care of! Just make sure you have a habitat that favors verticality - they need to be able to climb to feel at home! Cork board is best, either just on the back, or 2-3 sides of the enclosure. Humidity is a must, so have the base be filled with cocofiber, then add water and perhaps a heating pad set on low to maintain moisture. Moss helps too! All that's left is to feed them - just once or twice a month is enough.

The light on my display is too hot, and heats up the plastic really quickly, so I only use it briefly to find and observe her. They don't actually need light since they're used to being in the dark!

I hope you liked these facts on tailless whip scorpions. If you know more facts, lmk or just add it to the post! I'm still learning things myself - like for example, you can tell males/females apart by the size of their pedipalps (the males have reaaaally long pedipalps, like the one in that meme, the females have much shorter ones).

#bugs#bug#nature#insect#insects#entymology#forest#zoology#arachnid#arachnids#spiders#spider#whip scorpion#tailless whip scorpion#creepy

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippine tarsier (Carlito syrichta)

Tarsiers are tiny, nocturnal primates found in Southeast Asia. They may be cute, with eyes almost as large as their brains, but they are actually the most carnivorous primates. They hunt mostly small arthropods, like insects and arachnids. This species is perhaps the best known tarsier, living in lowland tropical forests of the Philippines. They are large enough to occasionally prey on small reptiles and birds!

#markhors-menagerie#primates#basal primates#animal facts#fun facts#animals#biology#Philippine tarsier#tarsier

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life in the Carboniferous

(first row: Diplocaulus, Lepidodendron, Arthropleura; second row: Meganeura, Hylonomus, Walchia, Pulmonoscorpius; third row: Tullimonstrum, Calamites, Edestus; fourth row: Pederpes, Eryops, Stethacanthus)

Art by:

Pederpes - Ntvtiko

Lepidodendron - Richard Bizley

Calamites - Jonathan Hughes

Walchia - Dinoraul

Arthropleura - Vladislav Egorov

Meganeura - Walking with Monsters

Pulmonoscorpius - Plioart

Hylonomus - John Sibbeck

Diplocaulus - Sergey Krasovskiy

Eryops - mmuyano

Tullimonstrum - Nobu Tamura

Edestus - Julio Lacerda

Stethacanthus - Ja Chirinos

It‘s the age of giant bugs!

But before I get to talk about giant bugs, we have to take a moment and appreciate the real stars of the Carboniferous: The plants! The whole reason it is called Carboniferous (“coal-bearing“) is because of them. The forests of the time got flooded repeatedly, decayed, rotted and over the ages have turned into coal deposits that we use today. So whenever you hear people talk about fossil fuels coming from dinosaurs you can “well-actually“ them and talk about ancient plants instead.

During the Carboniferous earth was a warm, humid place with lots of tropical swamp forests. Some of the plants you would have seen there are roughly familiar to us today, like ferns. Similar looking were the seed ferns, which are extinct today. They reproduced by making seeds (shocking, I know), unlike “regular“ ferns, that reproduce via spores.

In some cases the plant groups are still around today, but they look nothing like their Carboniferous counterparts. Calamites for example was a horsetail that grew into more than 30 m high tree-like structures. Closely related to the small modern clubmosses were the Lepidodendrales (“scale trees“, named after their bark, which looked like scaly reptile skin). Lepidodendron could grow up to 50 m tall and would have spend most of its life as a single unbranched stem, which definitely added to the weird alien feel of Carboniferous forests. A more familiar sight were the earliest conifers, like Walchia, which lived during the late Carboniferous. Many other modern plants including grasses, flowers or hardwood trees, like maples or oaks, weren‘t around yet and wouldn‘t be for many millions of years.

Now that we have established that the forests of the time were strange and alien filled with plants of all kinds of weird shapes and unusual sizes, let‘s look at the bugs, which were also having all the wrong sizes:

Among many others there was the dragonfly cousin Meganeura with a wingspan of more than 70 cm, Pulmonoscorpius, an about 70 cm long scorpion and Arthropleura, a truly gigantic millipede, more than 2 m long. It was comparable in size to the biggest sea scorpions and one of the biggest arthropods that ever lived.

The questions is of course, why were insects and other arthropods this big? The main answer is oxygen. Insects have a very different breathing system than we do and it doesn‘t scale well with size. Because of that they have a size limit. At some point, they just can‘t get enough oxygen into their bodies (thankfully, because I don‘t need giant spiders or mosquitos or whatever). During the Carboniferous however, there was a lot more oxygen in the atmosphere than there is today, so the arthropods could grow much bigger than they do today.

Another reason for the giant bugs might be, that they didn‘t really have a lot of competition. There was nothing to keep them in check, so evolution just went wild with them. You have to remember that, while insects were already taking to the skies, the proudest accomplishment of our tetrapod ancestors was crawling from one puddle to another. To say that arthropods had a head start would be an understatement. So for future references, remember that every time I mention a cool thing any vertebrate does, there probably was an insect that did the same thing millions of years earlier.

But speaking of the tetrapods: They were getting better at crawling between puddles. We get the first true amphibians like boomerang-headed Diplocaulus and the giant Eryops, one of the biggest land animals of the time (you know, roughly milliped-sized). Maybe even more exciting was that during this time we see the first amniots! That‘s right, there are animals that lay eggs now. Real, actual eggs, that can survive without water. These lizard-like creatures (they aren‘t actual lizards, those will take a lot longer to evolve) can finally leave the puddles and rivers their amphibian cousins have been bound to.

It‘s probably a good thing, that they can leave the water behind, because there was some very weird shit going on in the oceans. After the placoderms went extinct during the late Devonian mass extinction (rip), a lot of bizarre shark relatives showed up, like Stethacanthus with its anvil shaped dorsal fin or the absolute horror that is Edestus.

But the weirdest thing of the Carboniferous (maybe one of the weirdest things ever) has to be the Tully monster (btw, not really a monster, only about 35 cm long). I mean, just look at it. It has a mouth that is separated from the rest of its body by a proboscis. It has stalked eyes. It is weird as fuck. We also have absolutely no idea what it is. Science agrees that it is an animal, and that‘s about it. There are arguments for it being a vertebrate, an arthropod, a mollusc, a worm and pretty much anything else you could think of. Honestly I just love it because of how strange and fake it looks.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The caterpedes are a group of abundant and diverse insects found well across HP-02017 in the Middle Therocene. They are, as their name would suggest, the larval forms of moths: yet, oddly, they never actually become moths at all: they are neotenic, maturing and mating in a larval form without ever undergoing pupation.

A misplaced hormonal signal that halted their metamorphosis but allowed them to grow functional gonads has enabled the caterpedes to spread far and wide in a world that, in its inception, was filled with the essential insect life such as pollinators and detritivores, but had many ecological vacancies left unoccupied. Thus, these mutant, non-metamorphosing caterpillars came to fill the niches of various other arthropods: in the case of the caterpedes, some became scavengers on the leaf litter feeding on dead vegetation like millipedes, while others became predators that hunted smaller insects, much as centipedes or arachnids would.

But even still, this was a world where predators abounded, even the founding hamsters that were present since the beginning. As such, the caterpedes have had to innovate with various defenses since day one: and in the Temperocene, few are as remarkable as the fiery blackbuff (Pseudophiops caudatucephalus).

Fiery blackbuffs share their habitat, the damp tropical forest floors of Mesoterra, with the five-eyed whipwyrm (Pyrophimys pentoculus): one of the most lethal of the burrowurms delivering a deadly sting in its front claws that can incapacitate an animal the size of a piggalo and kill anything else smaller. The five-eyed whipwyrm is generally a placid insectivore: yet it is this diet of ants, slurped up with its long flexible tongue and narrow mouth, that provides it with the toxins it needs to produce and concentrate an even more powerful paravenom.

As such, the distinctive arrangement of three false eye-spots and red stripes on a black background is one recognized and feared by every creature that lives in those same forests that the whipwyrm frequents: and the fiery blackbuff takes full advantage of it. Mimicking the distinctive conical head and five false eye spots on its posterior end, the blackbluff flashes its distinctive behind when bothered by predators: primarily small ground-dwelling ratbats. The sight of something resembling a deadly burrowurm sends many would-be attackers fleeing: and they usually do not return to confirm, allowing the otherwise-defenseless caterpedes to inch along another day.

------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#ask#species profile

66 notes

·

View notes