#thomas howard 3rd duke of norfolk

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

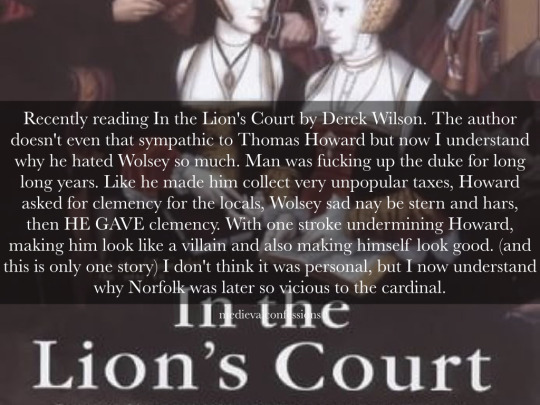

[In an] undated engimatic letter from the period which has survived [...] [the King instructed Wolsey to][...] 'make good watch on the Duke of Suffolk, the Duke of Buckingham, on my lord of Northumberland, on my lord of Derby, on my lord of Wiltshire and on others which you think suspect to see what they do with this news. No more to you at this time but these few discreet words.' It is unlikley that this referred to anything of the nature of a nascent plot, but it does indicate that Henry and his chancellor were both aware of ill-feeling among the leading nobles and that the King was fully behind Wolsey in his determination to keep an eye on them. Buckingham was especially a marked man and he would eventually be destroyed by his own intemperance or Wolsey's malice or a combination of the two. But he was no faction leader. He was [not][...] adept at intrigue and Wolsey was far from being the only man he had turned into an enemy. Among others with whom he was on bad terms was his son-in-law, the Earl of Surrey.

Wilson, Derek. In the Lion’s Court : Power, Ambition, and Sudden Death in the Reign of Henry VIII.

#edward stafford duke of buckingham#thomas howard#thomas howard 3rd duke of norfolk#(altho this is before he's a duke...obviously#there's often a continuity drawn which i think came from both the commonality of names and the tudors showtime conflating the two#it was thomas howard 2nd duke of norfolk that presided over buckingham's trial and gave the verdict with 'tears streaming' down his face#and thomas howard 3rd duke of norfolk that presided over his niece's trial with the same. but not the same person#derek wilson#thomas wolsey#cardinal wolsey#henrician#henry viii#and idk if that was thomas boleyn...? was he called the lord of wiltshire before he was made earl? honestly don't know#but it'd be interesting if it was#it would suggest he was looking particularly at not just buckingham but those related to him by degrees#the lord of northumberland (at that time; the more infamous henry percy's father)#was the brother of eleanor percy; the wife of the duke of buckingham#white rose faction#(idk? maybe? im just trying to keep my research organized lol#for want of a firmer tag)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#fancast#thomas howard 3rd duke of norfolk#charles dance#thomas wolsey#michael mckean#thomas more#steve carrell#thomas cromwell#jared harris#stephen gardiner#mark gatiss#john fisher#peter cushing#tudor history#16th century#english history#medieval confessions

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can't help just writing "Oh, this asshole" in the margin whenever a book mentions Thomas Howard 3rd Duke of Norfolk for the first time

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

tudor gothic:

the lord chancellor is called thomas. he runs the country. he wants no part in where england goes from now. the lord chancellor is being arrested for treason. the lord chancellor was executed. the lord chancellor was never arrested. there is no lord chancellor.

the crown is dissolving monasteries. this is standard practice. all the monasteries are shutting down. this is thomas's fault. you have no idea which thomas. the crown wants the monasteries back. the monasteries are never coming back. you visited an intact monastery just yesterday. when you blinked, the ruins gave alms to the poor.

the wars of the roses have just ended decisively. the wars of the roses have been over for decades. the legacy of civil war haunts england. you've watched shakespeare's wars of the roses plays. the wars of the roses must have been over when the throne passed peacefully to henry viii. when you close your eyes, you can somehow hear reginald pole laughing at you.

the duke of somerset was beheaded for treason. so was the duke of buckingham. so was the duke of northumberland. so was the duke of norfolk. so was the duke of suffolk. the duke of suffolk never lost the king's affection. all the dukes are vying for power. but then you remember: there are no dukes. perhaps there never were.

the howards are not to be trusted. thomas howard was thrown in the tower. thomas howard was executed for treason. thomas howard lived out his life peacefully. thomas howard only narrowly escaped henry viii's reign with his life. you are drowning in thomases. they never end. one thing you are certain of, though: thomas howard is long dead. thomas howard will outlive us all.

you know the names of every courtier in the kingdom, and yet more go missing with every passing day. you try to note down the name of thomas wryth, but you cannot put quill to parchment. how is it spelt? wriothesley? you have always known that. you know it deep in your bones. and yet, when you try to say it out loud, words fail you. words fail everyone, where the earl of southampton is concerned. somewhere dark and terrible, an ancient beast awakens from its slumber. like everything else, it is also called thomas.

you turn to noting down the name of the queen. kateryn parr. this is a simple task. your subconscious whispers catalina to you in a distinctly spanish accent. your hand shakes. you try to write down catherine, but it morphs into a k against your will. you drop your quill, hand trembling. nonetheless, there is a name before you. whose name it is is anyone's guess.

mary is queen. which mary? which queen? suddenly, you are not so sure.

the bible is written in latin. the bible has always been written in latin. you flick through the pages of your bible, and greek letters swim before your eyes. you check the book again, and find you are holding a book of hours. all the words are in english. you cannot read any of them.

the king of england has ruled for many years. he is nine years old. the king of england is a foreign power. elizabeth was king; now james is queen. long live queen james!

#thomas howard will outlive us all is a reference to the 3rd duke of norfolk#but like. there's enough of thomas howards it could be several of them#none of them dodged death as well as he did though#inspired by my teacher being unable to decide how to spell kateryn parr's name#historyposting#*casually skips between reigns*

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne Boleyn & Elizabeth I by Tracy Borman

So far the book reminded me to these insane things:

1 Stephen Gardiner forged a fake warrant to kill Elizabeth. And all he got for it was a slap on his wrist.

2 Anne tried to name her daughter Mary... These are my daughters Mary and Mary.

3 Thomas Howard and Anne Boleyn visited baby Elizabeth, and Norfolk slipped away to say hi to Mary.

4 The father of Jane Boleyn was some kind of scholar.

Bonus: Not from the book but recently hit me that John Foxe was in the Howard household (hired by Mary Howard) until Norfolk came out of the Tower. And one of his first things was to kick him out. Which is understandable.

#tracy borman#anne boleyn#elizabeth i#thomas howard#3rd duke of norfolk#stephen gardiner#john foxe#mary i#mary howard

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lulworth Castle - Dorset County - England

Lulworth Castle, in East Lulworth, Dorset, England, situated south of the village of Wool, is an early 17th-century hunting lodge erected in the style of a revival fortified castle, one of only five extant Elizabethan or Jacobean buildings of this type. It is listed with Historic England as a scheduled monument. It is also Grade I listed. The 18th-century Adam style interior of the stone building was devastated by fire in 1929, but has now been restored and serves as a museum. The castle stands in Lulworth Park on the Lulworth Estate. The park and gardens surrounding the castle are Grade II listed with Historic England.

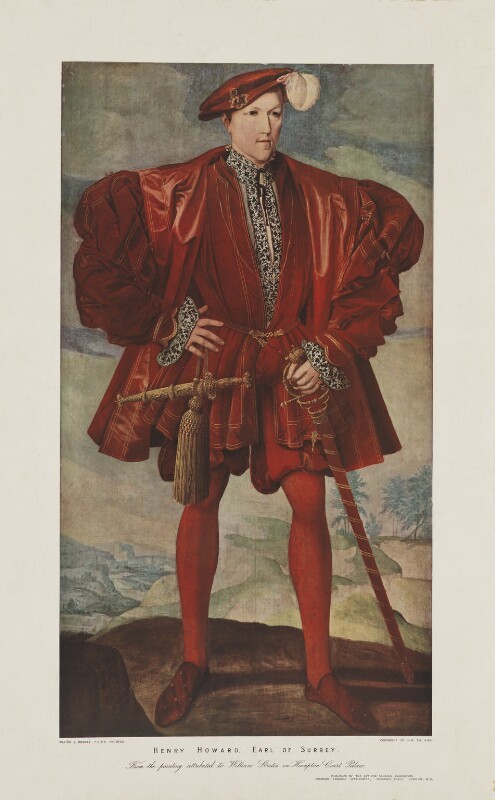

The foundations for Lulworth Castle were laid in 1588, and it was completed in 1609, supposedly designed by Inigo Jones. It was built as a hunting lodge by Thomas Howard, 3rd Viscount Howard of Bindon, a grandson of the 3rd Duke of Norfolk. In 1607 Viscount Bindon wrote to Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, crediting him with the origins of the design:

Archive tourist image

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Part Four

Thar she blows!

II. Norfolk and His Enemies

(First Half)

Ever since I became interested in history I've always believed Norfolk brought down Cromwell in revenge for Anne and George, as to me that's the most natural explanation.

To be clear, when I talk of his 'killing' them, I mean he cooked up the allegations and arranged the show trials, but was 'only following orders' as it were, and Henry is truly responsible.

I am NOT the type to whine that he was The Real Victim in all this: just a wide-eyed, gullible babe-in-arms who Jenwinlee Bleevd Ur Giltee thanks to moustache-twirling Cromwell's diabolical mind games.

But since the King can't be caught (invasion don't look so bad now), we might as well get his second in command.

It's my default assumption, and yet I've never seen it suggested elsewhere, as if it's literally impossible when 'we all know' Anne and Norfolk despised one another.

Worse, it upends two long-held lumps of received wisdom:

1. No one was bothered when Anne died (certainly not Elizabeth!)

2. Norfolk was evil and only cared about himself.

The most noble motivation anyone can accept is him acting out of rage when Thetford Priory was razed to the ground, and how Cromwell degraded the Howards by disturbing their eternal rest.

So people don't mind the idea Norfolk swore vengeance on behalf of these long-dead relatives who died in their beds, but feeling the same sense of outrage for a niece and nephew Cromwell shamed and murdered a mere four years ago is out of the question.

Yet even if Chapuys was right, there's an entire world of difference between bust-ups breaking out within close family units and some outsider taking their lives.

No one would tolerate such a blatant attack on their own kind, because it goes against every masculine instinct to defend the tribe from danger.

This Thomas Howard saw action at Flodden and in the French wars, plus the Pilgrimage of Grace and Wyatt's Rebellion: prepared to kill and be killed in defence of the country.

But now his own flesh and blood are being butchered, and you're telling me such a military man doesn't mind?

Oh no. Instead we should accept Cromwell and the Cardinal were simply perfect angels who no one could ever dislike for any respectable reason.

Regarding Wolsey, I shouldn't think this incident helped.

Norfolk was dispatched to Ireland in 1520 and took Elizabeth and the children along for the entire campaign.

As both of their fathers were still alive there really is no reason they couldn't have remained at home in much more secure conditions; so perhaps wanting their company could be a sign of at least some affection for his young family.

Norfolk arrived in May but three months later:

'There is marvellous death in all this country, 'which is so sore that all the people be fled out of their houses into the fields and woods, where they in like wise die wonderfully; so that the bodies lie dead, like swine, unburied'.'

By 'marvellous' and 'wonderful', Norfolk doesn't mean it's 'nice', or that he likes it; it's his own expression of horror.

As what he describes there sounds like absolute Hell made visible: a glimpse of the End Times playing out all around him in suffocating proximity.

The populus is rapidly declining before his eyes: people forced to abandon ailing relatives to die alone to save themselves, having nowhere else to go but resort to shivering vagrancy in the undefended wilderness, only to soon realize they too are infected and doomed beyond all mortal help.

And those coming along later, seeking safety, being met with the putrefying yet still-recognizable corpses of friends, family and neighbours, stepping through the rancid sea in hopes of finding a sheltered little spot to sit, in full knowledge it will be where they too shall die.

And the stench and the screaming and the ever-present throbbing terror of it creeping closer and closer until there's only you left to go.

'Wishes to have leave to send his wife and children into Wales or Lancashire, to remain near the seaside till this death cease.'

Well it's no place for loved ones to be, so Norfolk writes asking permission to send them off without him, therefore no royal business will be affected.

It's a rather poor show when a husband and father can't simply act immediately to protect his family, and is instead obliged to go through this insufferable rigmarole of writing and waiting, with the implication that even after the long, drawn-out silence they still might refuse.

They could be dead b' then!

'Anxiously desires a letter, 'for never sith [since] my departure from London [have] I had [a] letter from the King's grace nor you; and also to continue my good lord...'

If he's had no news in three entire months, what's the likelihood Wolsey will bother to open this particular message, no matter how desperate the situation might be?

Norfolk's grand plan isn't even to ship the wife all the way home, but for Elizabeth and the little 'uns to hide on this side of the Irish Sea, as he's intending for them to come back later.

(I enjoy thinking of him arranging their stay 'near the seaside', as if it's a holiday to Blackpool to build sandcastles and have ice creams!)

He must truly value both their welfare and company, so wants the separation to be of as short a duration as is possible, which has certain strange implications for his marriage.

Did you...did you actually love her at one point, Norfolk?

And she loved you?

In the first letter Norfolk was working himself up into a state, and here we are, one month later, and nothing's bloody improved.

'Eighteen soldiers have conspired to steal a fisher-boat of sixteen tons, go to sea, get a better ship, and turn rovers.'

In fact it's worse, as now he's dealing with mutiny and piracy—

'Victuals are so dear, the soldiers cannot live on 4d. a day.'

—Brought on by poverty and starvation, which he can do nothing about—

'Wishes he had the same authority as Dorset had in Spain, or as he has upon the the sea; otherwise he cannot keep order.'

—Because despite being marooned without news from the outside world, no one even bothered to grant him sufficient power to run the place.

'The death continues in the English Pale.'

To top it all, that stinking disease never went away—

'Has had no answer to his letters, and wants money.'

—But he didn't move the family as them heartless bastards never bloody wrote back!

He'll be tearing his hair out, man!

Damn straight, 'cause for all he knows they might sicken and die before him at any time, being:

• Elizabeth, aged about 23, heavily pregnant or recovering from childbirth;

• Catherine, aged 4 or 5;

• Henry, aged 2 or 3;

• Mary, aged under or about 1;

• Thomas, either a newborn or still expected.

Elizabeth is in a very vulnerable state and the children are young enough to be carried away by any slight chill, yet we're facing a veritable apocalypse not so much at the gates as ringing the doorbell.

This is a man whose entire first family were wiped out as if they never lived at all, and now his second wife and crop of children are in the path of some old Biblical malady that's cutting through the population like the scythe of the Grim Reaper.

Someone who's buried at least four kids WILL get jumpy at the first sniffle, regardless of severity, and you can't say he was wrong when Catherine died at fourteen.

There's also the fifth child, Muriel, about whom nothing is known, not even when she ceased to be.

But if she died right then, precisely because Norfolk never had permission to send her away, I couldn't fault any murderous urges in him.

All in all, compared to the previous letter promising life-long devotion and service—

'...And during my life, to the uttermost of my little power, I shall endeavour myself to serve and please the King's grace and you'.'

—Now bitterness over that same 'little power' and the sense of going unappreciated are creeping in to the text.

And given the mentality at the time was never to blame Henry for his own boorish behaviour, Wolsey's the obvious scapegoat.

Now between the deaths of Anne and FitzRoy comes the destruction of Lord Thomas Howard, but whereas the attainder against him arose in Parliament on the 8th of June (No. 1087), this seemingly was kept secret given he attended William's wedding on the 29th (No. 1222) and wasn't questioned until the 8th of July (above), at which point Mary Howard was also implicated.

Even if it took time to show up in the parliamentary schedule (being of a peculiar order), and so wasn't passed on the first day, whoever's pushing for it had to know it was coming long before to prepare it for the June sitting, and it sounds as if Margaret at least suspected something by warning Thomas Smyth.

(And I want to see this 'phisnayme' (the old word is 'phisnomy', as in the face) of Margaret so badly.)

The only explanation for this delay would be that Thomas was under surveillance during the intervening month, no doubt to see what else could be dug up even after his condemnation.

At a quick glance, the summons to Parliament went out before the 7th of May (No. 815), with Henry making ominous reference to the succession before Anne was even convicted or her marriage annulled (EE JENWINLEE BLEEVD!!!), and so I'd assume its list of business was mostly settled by that date, as with his fate.

If therefore he was being watched by May at the least, then no sooner were the Boleyns annihilated than the net went out again to ensnare any other related parties, and even perhaps in parallel.

Is that not...somewhat revealing?

Should Norfolk have turned on Anne and thus supported the plot against her, if merely in spirit, one would expect he'd be sufficiently secure for this never to be an issue in the first place.

For it would no longer be a case of the King's niece marrying the disgraced Queen's uncle, but affiancing the younger brother of the most esteemed Duke of Norfolk, and might even count as his reward for treachery.

It's always said that with Mary and Elizabeth disinherited and James being a foreigner, then Margaret Douglas was technically heiress, and so Thomas Howard was accused of plotting to seize the throne for himself.

But I don't think Margaret was even considered legitimate under English law, hence why she ended up omitted from Henry's will in due course.

And the attainder is in the same batch as the Second Succession Act, which is recorded as having passed on the 8th of June, with his interrogation occurring only ten days before it received royal assent on the 18th of July, alongside the Treason Act, meaning anything Thomas did before June wasn't even a crime, whilst events between June and July happened within a legally grey timeframe where either might theoretically apply, but unofficially.

(That last link doesn't even record when the Treason Act passed, as if it didn't, and was instead fast-tracked for Henry's unchallenged approval, which is all very fishy.)

Yet if the order given in the archives is correct, then Parliament condemned him (7th) before the succession (41st) even came up, and good old Henry prioritised murdering harmless youths over the security of the realm.

By their own admission Thomas wasn't trying to marry the heir, as that was still Princess Elizabeth, both when he first loved Margaret and at the exact moment they attainted him, because although her parents' marriage was already annulled, Elizabeth was made heiress by one Act and so it took another to remove her.

Instead the rumour goes (from Chapuys, so we have to tread carefully) that the purpose of this Act clearing the decks and letting Henry name anyone heir (a very suspicious clause in itself) was to make FitzRoy king, but he put the kibosh on that by kicking the bucket.

In June (No. 1069, a few paragraphs down) Euse claimed Robert Radclyffe, 1st Earl of Sussex (father of Norfolk's brother-in-law) proposed before the Privy Council that since Mary and FitzRoy were both bastards (and Elizabeth don't count) that they might as well prefer a male over a female, an idea which Henry failed to oppose.

Yeah right. That's what Sussex got told to say so Henry could put on a show of 'bravely' heeding the wisdom of his advisors by doing what he wanted to do regardless.

Adding it up, the idea Thomas was mistakenly arrested for treason, as if those behind it meant well, is utter nonsense, and he was crushed by the evil just as Anne was before him.

Come on, they've convicted him before the new law he 'broke' about marrying royalty even arrived, and which was drawn up because of this situation, as with Katherine Howard, so how can that be explained unless they purposely wanted him dead?

Interestingly, the John Ashley questioned here is probably Kat's future husband, plus the 'John Asheley' close enough to Anne to borrow £100 (No. 912), which was still on loan at the time of her murder.

I bet he coughed up sharpish.

And the 'Lady Boleyn' they're avoiding must be Elizabeth Wood, John's aunt and wife to James Boleyn, who's at her fetid tricks spying and preying upon innocent people again, as if that's her default setting.

It makes me imagine she was so notorious for her creeping, conniving ways that's exactly why they chose her to betray Anne, and I daresay she heard nothing more about this thanks to services rendered.

Isn't it a bit too much of a coincidence that this 'scandal' (No. 147) was only officially discovered after Anne's arrest, apparently, or at least, a long-standing love affair suddenly became a problem then, because somehow no one noticed it during the previous twelve months?

And THEN Mary Howard gets a mention, despite them envisioning her as the next Queen of England, and so you'd assume everything would be done to keep her out of it.

'The King is much mortified "devant mariage dicelle sa nyece;" much more because he has no hope that the Duke of Richmond can live long, whom he certainly intended to make his successor, and but for his illness, would have got him declared so by Parliament; and this was one of the reasons why he was so very urgent that the Princess [Mary] should approve the statutes that made her a bastard.'

Everyone was cast down and humiliated to smooth the golden path for FitzRoy, but no one expected him to collapse along the way.

I also wonder that if Thomas was now considered unsuitable if Mary Howard might also have been under the same shadow once Anne was gone, particularly as it was a marriage she arranged.

It's all very well a duke marrying a duke's daughter when that's the most he's ever gonna be, but if Fitzy's facing kingship it's simply not a good enough match anymore, so who knows what would've become of her.

After all, is this really much different to Lady Rochford's later activities?

'...And they have condemned to death...the younger brother of the Duke of Norfolk for having treated a marriage par parolles de present with the daughter of the Queen of Scots and Earl of Angus.'

Whilst Chapuys is only mentioning Norfolk so Charles can understand who Thomas is, doing so gives the impression Henry's outrage is firmly laid at the Duke's door.

'A statute has also been passed making it treason to treat for marriage with anyone of the blood royal without the King's consent.

The said personage of the blood royal was also to die, but for the present has been pardoned her life considering that copulation had not taken place...'

Henry was ready to cut his own niece's head off after she broke a law he invented precisely as an excuse to kill her.

I suppose in the end Mary survived just as Margaret did, i.e. non-consummation of either union, whilst Thomas was kindly left to suffer and die in gaol as a treat.

Here is an extremely sad letter from Margaret (No. 294) grovelling in gratitude to Cromwell and promising to throw Thomas's impoverished servants out on Henry's orders.

(I do hope she found the pair another home as I hate to imagine what happened to them otherwise.)

'Desires Cromwell 'not to think that any fancy doth remain in me touching him.'

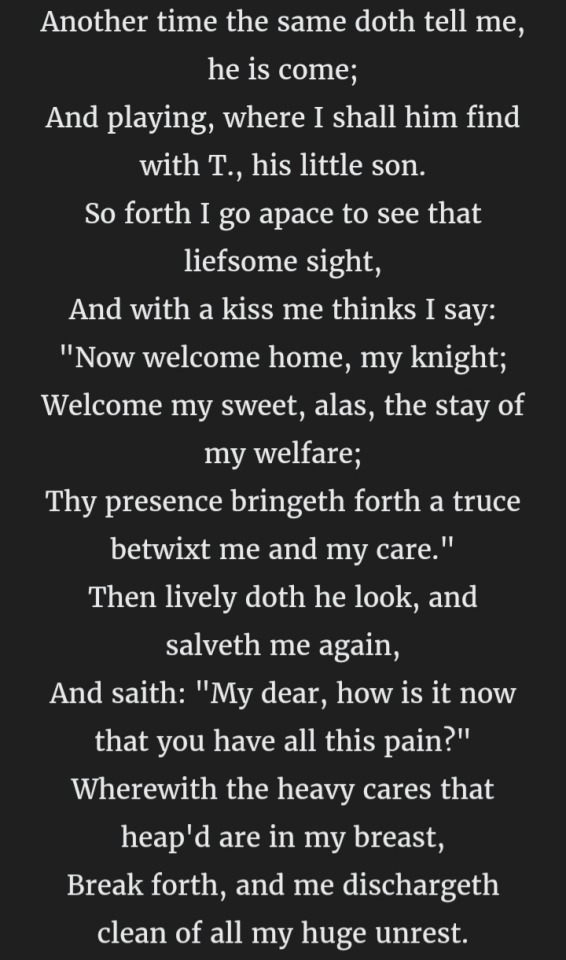

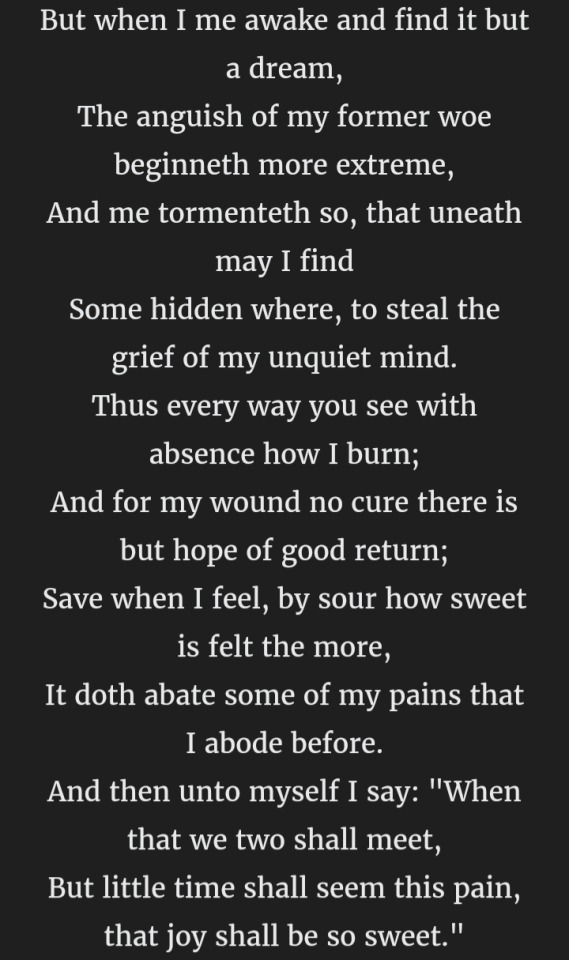

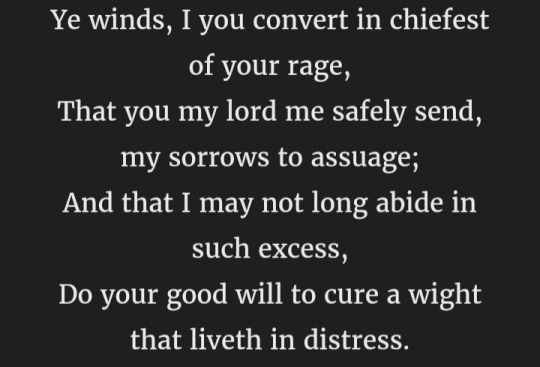

I refer you to her poem from Part Two for how much I believe that.

Still, Margaret caved immediately, and no wonder with Anne's example before her, besides Princess Mary almost going the same way.

On that note, people too readily overlook the horror of Henry almost murdering his wife, niece and daughter in sequence (Anne in May, Mary in June, Margaret in July), besides his palpable eagerness to do so, as they want you to see him as a big ol' cuddly teddy bear who Didn't Do Nuffin.

But the period between May 1536 and October 1537 is much underrated in terms of all-out, no-holds-barred utter lunacy:

A queen's just been decapitated; there's no designated heir, and for half of it no sign of one; the kingdom's about to tip into civil war and a thousand years of Christianity and near enough all English art and beauty that's ever existed is being battered and burnt before their eyes.

And all those who thought time would turn back so obligingly and it'd be endless sunshine and rainbows once they brought down that pesky Anne Boleyn are coming around to the realization that's it's got so much worse without her.

The tale of Thomas, Margaret and their doomed romance may only seem an insignificant portion of it, but there's something unnerving about how it slotted together so simply at the most opportune moment, where the one remaining claimant had to be erased before the grand plan took shape.

I kid you not: the rumour at the time (No. 532 & No. 533) was that Henry wanted Cromwell (!) to be king, as he 'loved [him] so', and handed over Margaret behind the scenes like a tearful virgin sacrifice, and therein lay Cromwell's motivation to be rid of his 'love rival' forever, which also casts him intervening for her in a very different light.

EEEEEEEEEEEEEEE! Like bloody Frollo and Esmeralda!

Now Cromwell being next in line is plainly absurd, and as he didn't marry Margaret once the fuss died down, we must presume that was never his intention; unless of course the discovery of everyone's violent opposition put him off.

(And good on the boys for wanting to avenge Thomas and defend Margaret's honour.)

It's a bit much painting Cromwell as the kind of creaking old pervert who'd accept young girls as gifts, or bribes even, yet these rebels are fixated with blaming anyone but Henry for his own actions, as was the fashion.

Ironically, this is nevertheless almost the exact same charge Cromwell went down for, except then it was having designs on Princess Mary, implying Henry kept the accusation in mind for future usage.

(And that rumour supposedly went about in July 1536 (No. 41, at the end) 'cause Henry ain't got no new ideas.)

Still, imagine if we could prove the epically beautiful Margaret really was the ultimate lip-smacking prize Henry dangled before Cromwell to goad him into spilling Anne's blood.

For I can't help sensing a genuine malice to proceedings where Henry wasn't about to let anyone be happy without his permission, to the level that a quick death was deemed too good for Thomas and so he can languish alone and in pain knowing he'll never see Margaret again.

And she's too useful to squander upon the scaffold, so let her live and remember.

On the one hand, Chapuys has no reason to 'embellish' the truth these days, but on the other, how can you ever trust anything a liar says again?

But his belief in FitzRoy's imminent elevation makes more sense than leaving the succession empty for the foreseeable future, especially as from June onwards he insists Henry's gone sterile and definitely won't get kids off Jane, who's barren.

Give 'em chance to breathe, man!

He also defends Margaret, which makes a change:

'...And certainly if she had done much worse she deserved pardon, seeing the number of domestic examples she has seen and sees daily...'

That'll be a dig at Anne no doubt, yet it's in the plural, so I'd love to know who else he means.

'...And that she has been for eight years of age and capacity to marry.'

Too much information there, love.

It's one thing to observe Margaret's over the legal marital threshold, but how does he know what her 'capacity' for it is, exactly?

I'll bet he's considered Princess Mary's 'capacity' before now.

I'll bet he has. Dirty bastard.

Margaret being his best beloved's old mate makes her 'one of the good guys' and so he's willing to talk her up, ignoring she was also Anne's lady-in-waiting, friend and companion for three years and so must've been cheerfully covering for all that beastly incest that was definitely going on.

But that's alright. Obviously Anne the Slag was corrupting Margaret.

Euse is coming out of two really long months of his 'EN IZ UH HOR' routine, leading the oh-so righteous charge against 'the Concubine' and salivating over her brutal murder, not to mention rubbing his claws together at the thought of 'the Little Bastard' being disowned as the daughter of George / Norris / random peasants and slung into the streets to starve to death.

But the moment a REAL secret affair gets exposed and it's all:

Well, what d'yer expect?

According to him, if Margaret's twenty then it's only natural any woman THAT much over twelve is gonna have certain urges and want to explore them, so even if she had slept with Thomas in or out of wedlock then Henry should just get over it as it's his own fault for keeping her single.

Ooooooh, very liberal!

Yeah man, these things just happen, don't they? It's no big deal.

Anne's a whore, tho.

'Since the case has been discovered she has not been seen, and no one knows whether she be in the Tower, or some other prison.'

Not sinister at all!

Yeah. Margaret's just vanished off the face of the earth after her uncle spared her 'for the present', but that's not saying he won't change his mind.

So yer'd best watch yerself, love!

This may not seem directly related to Norfolk, but I'd have thought if he'd had any part in killing Anne that the State might have stopped persecuting his family by now.

The Jane Parker fans like to highlight her financial woes during these months as proof she couldn't have testified against George, but if so, I'd have said Norfolk witnessing his brother done for treason was a bigger vote in his favour.

Mary Howard's connection is very worrying, especially as she's chaperoned Margaret 'divers times', and is therefore more in on it than the other friends and servants, and in doing so openly concealed and facilitated 'traitors' longer than any of them.

You'd almost say she was second in command after Thomas and Margaret themselves, so it's difficult to believe she got out of it just because the couple under sentence of death covered up for her.

Had FitzRoy survived, I wonder if they'd want rid of her quietly with a nice annulment to make way for a prime foreign alliance, with this threat pushing her father to agree.

And maybe she and Margaret escaped serious punishment thanks to the scheme fizzling out altogether, despite handing Henry another excuse not to support her, as if he needed one.

I wish more attention were paid to such a blatant stitch-up, as whilst it may not be a nefarious conspiracy on par with the one that took down Anne, none of this happened by accident.

Chapuys wrote of FitzRoy's decline on the 23rd of July, meaning he was conking out at that very second.

You'd think laying him to rest might be a matter for his own father to arrange, but no!

Turns out he's too tight to even finance the burial of the bloke that could've been his heir five minutes ago, and shunts it on to someone else instead, as usual.

In the normal run of things a family is patrilineal; that's why a wife takes her husband's name and so do the children as the next generation of his 'house'.

Yet as a bastard, them rules don't apply, and the child reverts to the mother's line.

But it's as if calling him 'FitzRoy', being an invented surname bellowing his illegitimate status, specific to him and him alone, more or less cut the boy off from both sides to stand alone as an entirely brand-new dynasty that simply popped out of the ether one morning.

Yet as it only contains him, then he was almost grafted on to the Howards upon marriage to give him a group to which he belonged, that is until Mary had children to expand the surname, whereupon he'd break away and she'd join his 'kind', if you will.

But having carked prior to all that he finished life as a quasi Howard adoptee, and so into the family vault he went.

'The King wished the body conveyed secretly in a closed cart to Thedford, 'and at my suit thither', and so buried...'

Seems Henry wanted a cloak-and-dagger job where they snook the stiff down to Thetford all hush-hush and the like, specifying a 'closed cart' to hide the grisly contents from snooping onlookers, which makes it sound like Fitzy can't even got a flamin' coffin these days and got tossed not just hither, but also thither (which is important), in the nice-and-airy boot of a clapped-out Robin Reliant.

'...Accordingly I ordered both the Cottons to have the body wrapped in lead and a close cart provided, but it was not done, nor was the body conveyed very secretly.'

What a come down, eh?

One day it's all kind hearts and coronets and the next you're nowt but any old cadaver rolled up snug in Norfolk's much-frequented, cast-off dayglo hearth rug.

But yer just can't get the staff these days and once the bloomin' Chuckle Brothers get hold of 'im they bunged the boy wonder in the back of the local ice cream van (between the soft scoop and Soleros) and trundled into town blaring bloody Greensleeves luring all and sundry out to have a good gawp at proceedings.

Worst of all (No. 164), turns out Richard and George Cotton were Fitzy's out-of-work home helps who were badgering Henry for black cloth and job offers before their previous boss was even propped up on the beaded seat cover.

Chapuys's version (No. 221) is that they dumped him in a wagon and draped a load of straw over the eight-day-old corpse in the middle of summer (eee) and just had the Cotton-Eye Joes (?) skipping along behind in full Lincoln Green like it was bloody Robin Hood themed.

'Few are sorry for his death because of the Princess.'

But that's okay as no one gave a toss about him and everyone's actually totally glad he's dead as they've also all worn themselves arthritic fantasizing about Mary sliding on to their throne.

'...And thank God she now triumphs, and it is to be hoped that the dangers are laid with which she has been surrounded to make her a paragon of virtue, goodess, honour and prudence: I say nothing of beauty and grace, for it is incredible.'

If Mary don't get a restraining order he's gonna start drinking her bath water.

'May God raise her soon to the Crown for the benefit of his Majesty and of all Christendom!'

I presume he's now referring to the Emperor, else he's saying he wishes Henry would hurry up and die as being dead would really do him the world of good.

'Even Secretary Cromwell has congratulated her in his letters...'

Watch out Euse! Yer got competition!

Whilst I doubt Cromwell, whatever he felt, would dare say on paper that he was glad Henry's only son was dead, and most likely this is Chapuys projecting his own revolting personality on to others, I'm grimly fascinated by the idea of Mary attracting all these unwanted ancient admirers who'd think Philip never had it so good.

And now Norfolk's gotta go cap in hand begging this rather macabre Cromwell for forgiveness even when the latter's apparently glad to see the back of poor Fitzy.

'I trust the King will not blame me undeservedly.'

Well think on, flower.

I don't know why the Cottons gleefully flouted instructions and risked their livelihoods.

I don't know why Norfolk would dare disobey his 'Master' and not supervise proceedings with obsessive scrutiny.

And I certainly don't know why Henry demanded all this whispered fannying about as if he was suddenly ashamed of FitzRoy's existence.

Some say this shifty attitude suggests Junior was bumped off, where because his stepfather's men joined the Pilgrims he would've done too, so Senior soon put a stop to that.

But that's silly.

First, if Henry somehow got wind of rebellion brewing months in advance I'd have thought he'd do a bit more to quell it than killing his own son, as if that's gonna help.

Secondly, he hasn't spent close to three decades gagging for a male heir simply to stuff the only one he has got.

If anything, I'd say FitzRoy could've whipped up insurrection himself and led the revolution, and Henry wouldn't have done much more than shake his fist at him.

He's not angry. He's just disappointed.

And from Fitzy's view, why bother?

He must've heard he was heading for the big time by now, so should he ever sympathise with the Cause, then all he need do is wait for Henry to pop his clogs and he's got free reign to do whatever he wants.

Yet imagine FitzRoy living, and being promised the earth; then Edward shows up.

What a kick in the teeth!

So even though this theory is absolute gibberish, I can't think of an alternative.

'This night at 8 o'clock came letters from my friends and servants about London, all agreeing in one tale: that the King was displeased with me because my lord of Richmond was not buried honourably.'

As for the oh-so confident assertion that 'everyone' judged Norfolk to be 'a twat', I marvel at how all these 'friends and servants' inundated him with warning messages then, as if they were worried about him.

Sounds like the perfect opportunity to be rid of the old git, eh? Most curious.

I suppose they're all 'twats' too.

There's another letter to Cromwell on the 6th where Norfolk's really tipping into panic after two more pals sent him word, and that's loads worse as they're sober old gentlemen who 'would not write with some ground'.

And mailing missives one day after the next is a sure sign something's up; usually you only see back-and-forth correspondence in the records once a week.

'I desire to know the truth by this bearer, who shall meet me ere I come to London; spare not to be plain to me.'

This is on Sunday night, he plans to reach London by midday on Thursday, and in that time the postman's gotta race to Cromwell and almost all the way back as he meets with Norfolk on the road to tell him what's up.

It's THAT serious.

And God bless Norfolk for riding into the jaws of Hell in full knowledge this could be it for him, as it's fairly obvious to read the gist of the friends' letters from his own, where it's not:

Ooh-ho-ho-ho-ho, you'll get a good ticking off this time, mate!

But more:

HE'S GONNA KILL YER, MAN!!!

'It is further written to me that 'a bruit [rumour] doth run that I should be in the Tower of London.'

This appears to be an unrelated topic, as the average Londoner won't know anything of the burial yet, if ever, so what's he done to deserve this?

The aggression is entirely Henry's own evil predisposition swelling up again, so the idea 'the people' are also gunning for Norfolk for no reason is far too coincidental.

An obsessive, paranoid and murderous tyrant craves insider knowledge on public opinion, especially when his own behaviour has triggered so much upheaval and ill-feeling.

Wouldn't he, in such an uncertain era, really need a fair few informants mixing in with the hoi polloi to gauge popular reaction, and round 'em up if they looked likely?

(Henry personally orders spies to prey upon and betray his people later in the year (No. 1178), so the idea is not unknown to him.)

And once we're there, what's stopping said subversive from manipulating mob sentiment for some higher (or rather, lower) purpose?

All he need do is start spreading a few scripted slanders, and when it gets around his employer can claim 'everyone' thinks it because it was spoken aloud once.

This is Henry's own personal vendetta, and whether it be solely down to his son's send-off (which he himself commanded to be as miserable and lonely as possible) or goes much further back, the idea that Londoners miraculously agree with him, and right at this very moment, meaning if he kills Norfolk it can be paraded as 'the will of the people', with Henry a merciful public servant devoted to his subjects' wellbeing, is freakishly unnatural.

'When I shall deserve to be there Tottenham shall turn French.'

Eeeeeeee! No, not that!

'I would he that began first that tale of mine, he being a gentleman, and I, were only together on Shooter's Hill, to see who should prove himself the more honest man'.

Yeah! Just you wait, lads! He'll have that meddling whipper-snapper over his knee then DUEL HIM TO THE DEATH before you can say 'Howard the Duck'.

Note he's quite sure only one fella is responsible, implying a deliberate attempt to whip up trouble, whereas a real general unpopularity would arise in many people at once as they all instinctively react to the same information.

I wonder if describing the shady figure as a 'gentleman' is a coy social nicety, or an actual belief the man belongs in the gentry with lofty connections.

If idle talk's going round London, I'd picture some loosed-tongued workman shouting the odds, or even a bunch of housewives regaling one another with tall tales.

Why then would Norfolk assume any tavern tittle-tattle was the work of a 'gentleman', which implies respectability, and thus honesty, when he could instead belittle them as a 'knave' or 'ruffian', and so undermine their words to aid his own plight?

And does the advertised threat of violent retaliation in a letter to Cromwell signify more than it seems?

After all, Norfolk made a point of saying his 'friends' were writing en masse to warn him of Henry's savage intentions, but Cromwell wasn't one of them.

Because he didn't want him warned.

As the Boleyns and the Howards were meant to all come down together.

'Your son is in good health here...'

The oft-repeated blabber of Norfolk hating Cromwell from day one never includes Gregory's madcap holiday hijinks.

'Cause it ain't enough to lay prostrate before the powerful but now yer gotta bankrupt yerself putting their kids up with bed, board and entertainment like a bloody five-star hotel now.

Yer house ain't yer own!

Is Greg supposed to be grand pals with Surrey and Bindon, and no hard feelings later?

Or are they on their best behaviour pretending to like him whilst flicking the Vs behind his back?

What's Mary's opinion?

He could've snapped her up if he'd played his cards right!

Speaking of which, did Greg attend Fitzy's funeral?

Did Greg report on Fitzy's funeral?

(Well how else did Henry find out?)

Is he a spy?

Yes!

Does Norfolk know?

'Course he bloody does!

So the Duke loses three relatives to the King's ravenous hatred, and then leaves Court taking an enemy informant back home with him?

They've a taste for blood!

And for this extra-special mission, Cromwell selected the one bloke he trusts the most to be certain of the utmost loyalty and fullest correspondence; all whilst Greg feeds off the very family they're desperate to destroy.

Can't even flamin' speak yer mind in yer own gaff these days!

Greg's a knob.

'...With the hand of him that is full, full, full, of choler [anger] and agony.'

Ooooooooh, camp!

'P.S. I have at this hour finished my will...'

Bloody hell, Norfolk! We're tryna have a cup o' tea here without you bringing us all down!

The heavy postal load this evening obviously put him in a right old morbid fit, where the SHADOW OF DEATH stalks his every waking thought.

The real irony is how it gives him a mind to settle his affairs before it's too late, even when should the worst happen, the entire point is they'll be robbing him blind first.

What a feckin' waste of time that was!

'...And written it twice...'

He's obviously gotta make two in case Henry produces a substitute scratched on a beer mat where Norfolk just so happens to leave all his worldly possessions to that dear Master o' his.

But don't tell 'em there's a copy, man!

They'll be turning yer house over ter lay hands on it!

'...And shall leave one part with you as my principal executor whom I trust next [to] my master...'

So not a bit then.

'...Whom I have made supervisor of the whole.'

As a will is utterly useless where he's going, this could be an elaborate ploy for sympathy.

Come on, lads! I'm just a poor little old fella teetering on the edge of death!

You don't wanna be killing me! I'll be gone soon anyway!

Crafty sod outlived the pair of 'em.

'I trust when I die you both will consider I have been to the one a true servant and to the other a faithful friend.'

Translation:

I'm a good girl, I am!

He's both implying his passing is imminent, and so hurrying it on is an needless extravagance, but also that when it happens they'll both miss him, thereby planting the idea it will be a natural death, that it should, and must be, even, and changing that would go against the natural order.

As I peruse these letters I have the fancy that Norfolk spent a lot of time watching and observing human behaviour, and developed a fair grasp of psychology long before its invention.

In doing so he learnt the exact method of provoking pity, or at least doubt and hesitation, which bought him enough of a reprieve to survive until the political situation shifted to his advantage.

I can think of no other courtier who had THIS many close shaves but nevertheless died of old age when so many young men and women begged and pleaded for their lives and yet received no such mercy.

'Sic transit gloria mundi.'

Or 'So passes the glory of the world', as I would say.

Is this Norfolk's opinion on his own demise?

Ooooooh, get you!

Whatever he said to Henry must've done the trick as here we are on the brink of civil war, which you could say ended up saving Norfolk's bacon in the long run.

But it's not all glamour.

This link leads to one of the most densely-packed fatboy collections I've come across, which gives you an idea of the sheer pandemonium unleashed as reports start flooding in from all sides.

It feels like combing through week upon week of correspondence and it's only five bloody days, albeit five days of insanity; ranging from the fun stuff where Bess Holland's uncle John Hussey, 1st Baron Hussey of Sleaford, won't leave the house in case the rebels look at him (No. 561), to horrors beyond belief where one of Cromwell's men was ripped apart by dogs (No. 567).

I'm trying to make sense of where Norfolk came into it, but it's such a mess I haven't really got a grasp on matters.

On the 7th of October (No. 579; 2) Norfolk's to prepare the assembled forces for Henry's inspection:

'That my lord of Norfolk be sent immediately to Ampthill to exercise the office of High Marshal, and to set the army which shall be then arrived in order, that the King at his repair thither on Monday may view them and dismiss them from time to time with thanks and good entertainment.'

Sounds like when Henry got thither he expects a table of cream cakes and a flamin' juggling routine.

Then on the same day (No. 580; 2), Norfolk's designated as on Henry's defence team and must supply 600 fighting men to boot.

(Presuming I've read it correctly, do note how much bigger his protection squad is compared to Section 1's list of those to be sent north, whilst Jane's bodyguards are practically non-existent, and that hoity-toity Henry insists on being guarded by his highest ranking subjects.)

Further down, Section 5 lowers the quota to 500 men, being diminished along with everyone else's, suggesting conscripts were already hard to come by.

And now we've only got to the 8th, and Norfolk's staying home instead!

'...Received the King's letters, the most 'discomfortable' that ever came into his hands...'

He wasn't saying that a couple o' months back when all the pen pals frightened him into hysterics.

Nah, but he's givin' it good grease, where the most soul-devouring fate imaginable is not serving and dying to protect Henry VIII.

'...Commanding him to send his son with as many horses as he can furnish, and himself to stay at home.'

Daft old Norfolk's knightly pride is imperilled when it turns out he'll be missing out on all the action, as that spells the eternal pipe and slippers.

There comes a phase in any man's life when the ever-pressing flow of time compels him to pass the torch on to the next generation, to lie at rest in the twilight of his years as those youthful fresh faces make a name for themselves in his stead.

OH NO YOU DON'T!

'If he sends away his horses, can do no service in repressing the people here, nor come to the King when commanded.'

Given his role of royal attendant appears to have vanished within a day, talking of what should happen when Henry calls on him is more wishful thinking rather than any concrete expectation of such.

You never know: one snub like this and it could be curtains on his career.

Well Norfolk ain't 'avin none o' that, for he's raring to get stuck in:

'Does not wish to sit still like a man of law while other noblemen either come to the King or go towards his enemies.'

Or in other words:

Eee! There may be snow on the roof but there a fire in the hearth!

It's easy to mock, but let's not ignore Norfolk volunteering for what could be certain death at his age.

In fact he's so mortally affronted by being kept out of danger he posts THREE grumbling letters on the 8th, and to anyone who might listen.

We only get given the gist of the second (No. 602), in which he sends Surrey up to vouch for him, as if, despite all his bloody-minded bluster, he's still too frightened to meet Henry whilst in this insubordinate mood.

(Bindon meanwhile, who's all of sixteen, will not only have to take care of Mary, Frances, Bess, his own wife Elizabeth and any little children whilst his dad's away (No. 659), but the whole population and property portfolio!)

For no matter how much of a sugary-sweet veneer Norfolk paints into every epistle, the shiny façade always cracks as his overpowering resentment bleeds into his words:

'My lords of Oxford and Sussex might have stayed [in?] this country as well as the writer.'

It's either 'stayed' as in they're just as qualified to keeping watch over the area as him, therefore don't pick on Norfolk for all the boring jobs.

Or 'stayed in', by which the Duke suggests they too be retired from service when they're both a decade younger than him.

The 'as well' I suspect doesn't signify 'alongside', where Norfolk wants some company, but more that they're 'as fit' and 'as suited' to be left out, and that they haven't been, with two earls preferred over a duke, smacks of naked favouritism.

Sussex was the one chosen to suggest FitzRoy be the next king, which in itself implies Norfolk knew nothing of the scheme for all that it concerned his own daughter, although perhaps it wouldn't have done for long.

As for John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford (Surrey's father-in-law), well to this day the De Veres are remembered as ardent Lancastrians who stood by Henry VII, whereas the Howards didn't, so I wonder if Norfolk believed his grandfather's unfortunate loyalties were being dragged up again as an excuse.

In the sense that, when someone falls from favour, everyone 'suddenly' remembers old missteps and long-held animosities to pile upon the victim and bury them beneath.

Well if the 1st Duke destroyed the family in battle, whilst the 2nd restored them to glory, then the only way for Norfolk to get 'em out of this current situation is to charge in when the chance arises and hope he either succeeds or at least goes down fighting like a hero, where his sacrifice can't make things any worse.

Besides, this will be Surrey's first taste of war, and we shouldn't discount any fatherly urge to keep a boy company as he steps into manhood, teaching him and helping out if he falls into danger.

And yer gotta maintain an eye on your own fine fleet of stallions, as I wouldn't trust them bastards to ever give 'em back.

'Unless he hears again by Tuesday night, will rather set forward to the enemy, though he has only 40 horses with him, than remain at home with so much shame.'

Whilst selected to serve Henry originally, when it comes to disobeying orders Norfolk opts for the more lethal option, and will simply turn up for a fight anyway, as I suppose that's the best way to show defiance and yet not cause offence.

(With him taking that many steeds off the property I'm envisioning Bindon and the birds trapped in the house until he comes home!)

Now Norfolk's birthdate is given as the 10th of March 1473, making him sixty-three at the time these words were written.

You'd therefore assume this is Henry's uncharacteristically gentle hint of nudging Norfolk into retirement, and it's about time the younger lads like Surrey earned their spurs to prepare 'em to take over full-time in the future.

(Two days after this letter, for example, is one from William Howard (No. 636) fretting about pestering his mam to supply soldiers to fill his quota.

And I daresay the other Thomas Howard would've been summoned alongside him, had he not just been inconveniently sentenced to death.)

But THEN you have to consider that, if he's past it by 1536, what the bloody hell was Mary doing dragging him out in 1554 at the grand old age of EIGHTY-ONE to take on Wyatt's Rebellion, when he'd just done a six-year stretch inside and was well out of condition?

So how much of this is Henry's entirely reasonable expectation that his army comprise the fittest men available (Surrey's nineteen) and how much is a personal animus towards the Duke, mere months after they've almost fatally fallen out?

The day before this (No. 576) we get yet another dispatch of Chapuys's best gossip-mongering, if you can trust anything from him.

It certainly would make a change to be able to quote another ambassador and thus assume they're telling the truth, rather than needing to comb through each and every syllable to work out what the motivation is this time.

Given his willingness to enter into private (and, as he imagines, revealing) conversations with Norfolk and Cromwell, he necessarily needed to maintain at least the bare minimum of civility towards both; but from his comments he seems to actually like them, and so one would assume these reports were essentially truthful.

But I can't believe that!

According to Chap, Anne's all-consuming obsession in life was to kill Katherine and Mary and then cackle maniacally as she bathed in their bluest of blue blood, and yet The Bitch just never got round to it, for some reason.

Cromwell however, is pathetically devoted to Mary and The Cause (having strangely never shown it during the previous decade) and telling her it's a pity she can't be put to death (No. 1110) is as friendly as it gets.

When Anne apparently toyed with marrying Mary to Surrey (a future duke) this was sheer vindictive evil, as no way would espousing her to gutter-dwelling filth like that be acceptable.

But when there's a rumour Henry wants to give her to Cromwell, that's fine as Chapuys simply won't credit it; and besides Crom's such a top bloke he'd clearly refuse any such offer regardless.

He Knows His Place.

When Elizabeth merely existing deprives Mary of her title, it's the most abominable crime of the age; and now Anne's dead the long-for happy ending is here at last when Cromwell keeps on lying about Mary being declared princess and sole heiress next week (No. 1069, all the way through).

Yet when she isn't, suddenly it never mattered at all as 'princesses' are an entirely alien concept that don't even exist in England (No. 219, second paragraph) and so who actually cares about these meaningless baubles?

Then for Norfolk, we all know how he really worshipped The True Queen and is famed abroad as a 'powerful friend' to Mary (No. 1212), and he WOULD have betrayed Anne eventually, but the chance just never came up.

And even if he vowed to crack Mary's head open (No.7, a long way down), this is such a complete non-issue Chapuys buries it within mountains of text and never brings it up again, so how can it be true?

With Henry, Euse's saccharine lovey-dovey dross on how Mary's never been better treated and how Daddy dotes on his icky-wicky best girl is habitually interrupted with the odd reference to Henry sharpening the axe, but you've gotta accept these little personality quirks, eh?

One informant even tries to tell him Henry was openly nasty to Mary and brought 'a dram of gall' into their conversation (No. 41), but he defends it as a 'father's authority', which they ought to 'condone'.

So how can we say Chapuys's pathological hatred of Anne was her own doing for treating Mary so 'badly', when he does nothing but excuse reported ill-treatment when it's done by anyone else?

Somehow in three years Anne couldn't bully Henry into killing her, and yet the moment she's dead Henry freely elects to do it himself, for he don't faff about.

And that's after Chap heard Henry was slinging snot around over the 'accursed whore' plotting to poison Mary and Fitzy (No. 908, a bit down), but what's wrong with the wife 'avin a bash first?

So whilst Anne lived, everything was all her fault, but now she's dead, things 'just happen', as it's no longer convenient to hold anyone responsible.

Although I don't see Chap rising to his former frothing glory again, he's too comfortable spinning the blackest of black fantasies to quibble over slipping in a few white lies whenever he wants, and so the day will never come when he proves an honest man.

'He has sent for the Duke of Norfolk, although it was rather against the grain, for he has been somewhat angry with him at Cromwell's suggestion, and it was said that he was half-banished [from] the Court but urgent necessity has caused him to be recalled.'

Euse claims Norfolk was 'half-banished' from court thanks to Henry being 'somewhat angry with him', but then again it was an entirely synthetic emotion felt 'at Cromwell's suggestion'.

Eh?

Reading these archives has ruined my ability to tell the difference between sincere appreciation and the more oily end of buttering 'em up, as when Norfolk wrote to Cromwell in September (No. 470) offering him 'a million of thanks for [his] pains in [the Duke's] affairs', you'd almost believe Cromwell was the great champion who smoothed things over with the King and saved Norfolk's life.

Then here, if Cromwell's egging Henry to hate him, suddenly he's the shady puppet master working behind the scenes with his hand up the Aris like Jim Henson on Miss Piggy.

Every retelling of this relationship is always Norfolk's one-way stream of flowing hatred, with not a word on if Cromwell reciprocated.

But given what we've seen, maybe there really was something to Chap's claim (in Part Three) that Cromwell promised to 'lower the great ones'.

...Today he [Norfolk] has dined with the Bishop of Carlisle [John Kite], and they have done me the honour to send for my wine.'

Norfolk: "How 'bout a swift 'alf, here, lad? I'm gasping."

Bishop: "No go, mate. Me cellars are drunk dry."

Norfolk: [Pause]

Norfolk: "You really need to see someone about this, love."

Apparently Norfolk wanted to beat Mary to death, and yet it's still a bloody 'honour' when he raids yer drinks cabinet!

'Immediately after dinner he left in great haste for Norfolk...'

Yer can't have time ter bloomin' disgest here!

'The Bishop tells me the Duke does not think much of the said commotion—'

Heh!

'—And believes it will be easily remedied, saying that the rebels cannot exceed 5,000 men.'

Well that's a laugh: eyewitnesses are putting it at eight times as much.

'The Bishop has also sent to me to say that he never saw the Duke so happy as he was today...'

Flitting around with a spring in his step and a song in his heart!

'...Which I attribute...'

Chapuys hasn't spoken to Norfolk, Cromwell, Henry, or even the Bishop directly, therefore the excerpt is based on second-hand testimony at best, and what follows is merely guesswork: spinning events to suit his own warped worldview of how they should be.

'...Either to his reconciliation with the King...'

He can't even keep to a single narrative in the same story!

How can it be that Henry's finally let bygones be bygones and we're all pals now, when calling him to court was 'rather against the grain', where Henry begrudgingly accepted it as an 'urgent necessity'?

...'Or to the pleasure this report itself has given him...'

And now Norfolk's so unhinged news of violent rebellion is music to his ears!

'...Thinking that it will be the ruin of his rival Cromwell...'

Describing Crom as a 'rival' implies their enmity was a well-known feature of court life, and therefore both knew their (presumably) mutually penned flattery was all a game of dancing about the truth.

So you're pandering to an enemy to survive, and they know it's wholly insincere, yet you do it anyway!

And they do it back!

'...To whom the blame of everything is attached, and whose head the rebels demand...'

Here's an example of where Chap's cock-eyed view leads into yet more of his smug fantasies.

He's adamant Norfolk's cheering for the uprising on the sly, as that fits with the ever-present insistence that ONE DAY he'll ride to everyone's rescue (you'll see!), whereas Howard protests he's dusting off the broadsword and begging to give 'em Hell personally, and indeed objects to missing out on the fun.

If the Duke longed for regime change so badly, he would've waited at home as Henry ordered him to, not risked his life charging into the fray, but supposedly he's peering into a golden future where the Pilgrims do all the dirty work of killing Crom whilst he picks up the pus-plagued pieces of Halibut's hairy heart.

Henry VIII: "WAAAAAAAGH!!!!!!!!!!!"

Norfolk: "There, there. I'll look after you now."

Henry VIII: [Sniffs] "Hold me."

Norfolk: "Only if you hold me."

Problem is that Henry's a puffed-up sanctimonious berk who starts ree-ing himself silly at the mere mention of heeding those howwid plebs, and reportedly said 'he [would] not forego my lord of the Privy Seal for no man living' (No. 1042), so the only way Crom's getting culled is if the rebellion grew so powerful Henry's own throne was endangered, whereupon he would be obliged to do as told.

And in that situation, if Norfolk hasn't perished amid the onslaught then he'd soon find himself banged up and beheaded for failing to settle the unrest earlier.

Therefore, if he's in any way cheered by the news of war, it's on the hope he can reclaim all recently lost favour by putting down the danger, no doubt with the misty-eyed memory of his father's return to glory in mind.

'...Also that it may be the means of stopping the demolition of the churches and the change in matters of religion, which is not to his mind.'

Norfolk never lets up telling everyone how fervently he holds to Henry's own personal theology, to the extent he has no opinion of his own barring the one Master grants him this week.

And yet everywhere he goes, and no matter what he says, they all refuse to believe he's anything but the valiant Catholic warrior come to purge the land of heresy!

It's like they're pushing the old Duke down into the pit of martydom whilst he's still clinging on to the door frame.

'It was because he declared a part of his wishes in these matters that he incurred the King's displeasure.'

If there's one thing Norfolk ain't doing it's spouting the odds about religion, especially when he's only just dragged himself back from certain death, but pretending he would suits Chapuys and his bizarre hero fantasy, although you can tell it's nonsense straight away.

We know Henry really took the bloody hump because of FitzRoy's funeral, with perhaps some lingering resentment of the entire Howard clan thrown in for good measure; otherwise you'd have to believe he somehow forgave it, and Norfolk returned to court, only to be kicked out immediately for mouthing off.

As if!

And how can he have spoken so boldy if Henry didn't mind in the least until Cromwell suggested he find it offensive?

Not that I credit that either, for it's not as if the old git ever needed help blowing his top, and he certainly doesn't hold back on Norfolk once Cromwell's dead.

'The Duke was one of those whom the good lord [Thomas Darcy, 1st Baron Darcy de Darcy] of whom I formerly wrote, counted as willing, when occasion required, to defend the cause of the Church...'

Leave him alone!

Why are they all determined to drag Norfolk into their own whipped-up daydreams of treason?

'...Though he did not rely much upon him, considering his inconsistency.'

I'd say he's been remarkably consistent in wanting to keep out of trouble.

What they mean is it's always a surprise when a stroppy, over-emotional pensioner fails to live up their vision of an iron-willed, steely-boned Roman Catholic juggernaut crushing all heretical challengers, which they've chosen to project on to him.

'The King does wisely in using every effort to remedy it, otherwise all would go to ruin; yet there may be a danger that when the King has assembled a number of men, several may pass over to the rebels, as 500 have lately done whom the husband of the mother of the Duke of Richmond has raised.'

First Henry hates Norfolk, and booted him out the castle when the latter played his face once too often.

Then Henry's obliged to recall the Duke to save the kingdom, but only when pushed to the extreme, and moans about it constantly.

Now suddenly Henry's doing all he can to woo Norfolk back to his side: bowing and scraping and letting everyone know who's really running the joint.

And even though Norfolk's apparently made it plain how much he objects to the Dissolution, and consequently is open about his rebellious leanings, the best way to defeat 'em is to put a confirmed sympathiser in charge of the army!

Not only that, but as well as being led by a potential traitor, all the new recruits are liable to switch sides too!

What could go wrong here?

If Chapuys is such a inconsistent loon he's staggering from one self-contradictory barmpot assertion to the next, and all this from a brief snippet of his usual waffling reports, then how can he be trusted on anything?

Look at the timeline:

• 5th of October: Norfolk answers the summons and arrives at Court.

• 7th of October: Norfolk gets fed by a bishop and goes home to prepare; and also has his name put down for bodyguard duties and assembling the lads.

• 8th of October: Norfolk opens a letter ordering him not to come back.

That messenger must've been hot on his heels for the rejection to hit him so quickly, as if Henry changed his mind the moment Norfolk set foot out the door, which would therefore mean the Duke wasn't so essential upon reflection.

Well what was the bloody point of all this then?!

Henry don't even want him fighting he hates him so much, and hang the country.

Unless it's supposed to be that the moment Norfolk left, Cromwell set to work persuading Henry otherwise, which if so, was an imbecilic turn for the pair of 'em, as obviously the sensible thing to do is propel Norfolk into the heat of battle.

Not only does that ensure you've got the best man in charge of a situation, but he'll probably die doing it as a bonus, and thus save everyone the bother.

Right at the end of Chapuys's excessive babbling (not that I can talk) is a rather interesting little anecdote:

'I forgot that the Duke of Norfolk had requested the Bishop of Carlisle and a merchant here to get some rich merchants of London to buy a great quantity of cloths which were here; otherwise it would compel those who made the cloths to dismiss their servants, who would pass over to the rebels.'

Norfolk himself references the cloth-making in his third letter of the 8th, meaning Chap actually told the truth for once.

Well so much for 'snobbery', as follow that brain-dead analysis and you'd expect Norfolk never to give the welfare of the lower orders a moment's consideration.

Except his first move in putting an end to rebellion isn't going on the attack, but assisting the poor and providing employment, thereby fulfilling his main role as a nobleman.

Rather than dining with the Bishop constituting one last day of peace before he rode into chaos, turns out that slap-up dinner was in fact a preliminary business deal trying to if not calm the situation, then at least prevent it from spiralling out of control.

The idea is if there's a sudden mass order for clothing, then all the suppliers will be rushed off their feet, and not only need the current staff to work non-stop, but might even recruit more to meet the deadline, and in doing so keep yet more fellas occupied.

'The Bishop has promised to lend 5,000 or 6,000 ducats to one of the said merchants to be spent on the said purchase, and I doubt not several other bishops will be compelled to do the same.'

The clergy are specified to have lent the required funds, meaning someone will need to reimburse them all at a later date, and yet once given, they can't get it back from the clothiers.

Would this mean Norfolk nagged the Bishop to turn up his purse as a patriotic duty, one which the King would look kindly upon and pay him back in reward, being a promise Norfolk could never really guarantee?

Or is the Duke himself pledged to repay the debt, given it'll ultimately increase his chance of survival?

Well he does reference his money problems quite a bit once in the thick of the action: how he had to supply £1,500, including digging into his pension to kit out and pay the men (No. 800), so this may be a further complication.

I am truly baffled at how he came to be remembered as this stiff, snooty caricature far removed from the harsh suffering of everyday life, when unlike Anne, he doesn't even have a hostile observer blackening his name for posterity.

At least he understood most of the rebels won't be fiery zealots but poor people driven to desperation, and so the best and most humane way to scupper unrest is to alleviate the very hardship that drove them into take up arms in the first place.

That in turn ensures more men remain alive and we don't have a sudden surge in widows and fatherless children sinking into beggary, theft, and future violence, and so contributes to the common good.

And I bet this budding plan somehow got back to Henry's ever-eager lugholes and that's why the Duke ended up kicked to the kerb, as his way of doing things was just too bloody benevolent.

For contrast, Henry's letters of the time read like nutcase anti-monarchy propaganda: wailing at the sheer affrontery of the vile plebs having the audacity to question their supreme betters (No. 780; 2)—

'Never heard that princes' counsellors and prelates should be appointed by ignorant common people nor that they were meet persons to choose them.

"How presumptuous then are ye, the rude commons of one shire, and that one of the most brute and beastly of the whole realm and of least experience, to find fault with your prince for the electing of his counsellors and prelates?"

Thus you take upon yourself to rule your prince.'

—Ordering Brandon to visit genocide upon entire settlements, right down to the children (No. 780)—

'After this, if it appear to you by due proof that the rebels have since their retires from Lincoln attempted any new rebellion, you shall, with your forces run upon them and with all extremity "destroy, burn, and kill man, woman, and child [to] the terrible example of all others, and specially the town of Louth because to this rebellion took his beginning in the same."'

—And chiding Norfolk for showing too much mercy when he ought to be chopping 'em up and decorating the place with their mutilated body parts (No. 479):

'We approve of your proceedings in the displaying of our banner, which being now spread, till it is closed again, the course of our laws must give place to martial law; and before you close it up again you must cause such dreadful execution upon a good number of the inhabitants, hanging them on trees, quartering them, and setting their heads and quarters in every town, as shall be a fearful warning, whereby shall ensue the preservation of a great multitude.'

But Ee Nevah Lost Duh Luv Ov Duh Peepull, dontcha know!

Whilst I am glad Anne's charities are given greater publicity as the years go by, it'd be strange indeed if she was the only one to care.

The Pilgrims themselves also have nothing but good will towards the Duke (No. 1371):

'Every where the people are very sorry for their offences against the King, and right joyous that the Duke of Norfolk shall come amongst them to do justice to the poor.'

Do justice, eh?

So he wasn't famed as a peasant-hating brute in his own time, then?

One of the rebels' core motivations is to 'purify' the nobility of all low-born sorts like Cromwell (No. 705 & 705; 4) and only be ruled by genuine aristocrats, so they take to the Duke as right up their street.

But because it's Norfolk, every positive you find is always twisted and distorted through the most negative lens; and so his plan will be mocked as an entirely selfish act to make his own job easier.

Even if that were true, and we can never know if it is, isn't this still the right thing to do?

'Since my coming to this town I have learned that light persons rejoice at this business in Lincolnshire, and that if I had not come, and the proclamation for clothmaking [not] been made, "some business might have chanced".'

And if Norfolk wasn't right all along!

Consider: he plotted this manœuvre on the 7th, and we're only in the 8th now, so the job offers went out at the earliest opportunity, and it was still a close call, as the blokes were packing their pitchforks when he rode into town.

'Sir Thomas Rushe, being sick of an ague, has written that the young clothiers are very light.

I have sent to him for particulars.'

Gimme them names, Tommo!

'...After the tales shown me here I dare not leave these parts without the King's command...'

Since he can't employ everyone, Norfolk's perching nearby to keep an eye on 'em instead.

I like how carefully he frames this as the strong, unbroken soldier, standing firm in eternally unblinking vigil, where nothing but the siren song of his King could ever draw him away—

'Notwithstanding my letter to you from Esterford...'

—When this follows him acknowledging he's only there from defying Henry's orders in the first place—

'...Nor send away my son with my horses...'

—And precedes disobeying them yet again by refusing to part with Surrey and his steeds.

'I think I had much wrong offered me to send my son and servants from me...'

Still going!

I know it's the same day, but it feels so long ago, based on scrolling.

A senseless daughterly pride comes over me when Norfolk's usual 'faithful minion' mask slips and he ventures to criticize Henry in print, in full awareness of the vengeful beast his prodding, as then I know I'm not wrong about him.

I especially like that this example concerns his loved ones, pets and dependents, and maybe I was right to suggest he worried for their safety and couldn't bear Surrey to go to war without him.

'In any other place I could be ready at a day's warning, and would, my lord of Oxford being sent down, leave these parts in good order.'

COME HERE, DE VERE!

I suspect he intensely disliked Oxford, despite having Frances waiting at home, given he specifically objected to the royal favour shown to him earlier and seems to want to force Henry to bend and soothe his injured honour by publicly demoting Oxford to guard duty.

Well before the 15th Earl inherited he heavily associated with his cousin the 14th Earl (another John de Vere), and deliberately sowed discord between the latter and his wife Anne Howard, Norfolk's sister.

According to Nicola Clarke (page 178):

'Out of all of [the 14th Earl of] Oxford’s bad habits, Anne was most disturbed by the company that he kept, notably his cousin and heir, Sir John [de] Vere [the 15th].

Vere was fifteen years older than Oxford and appears to have had considerable influence over him – Anne wrote that ‘my lord wyll do nothing without the counsel off Sir John Vere’.

He stood to inherit the earldom unless Oxford and Anne produced an heir and was understandably keen to do so.

However, the way he went about ensuring this was akin to bullying.

Anne wrote to Wolsey that ‘they [Oxford’s friends] care letyll ffor hys comyng forward so the inherytannce meyt be saved for Sir John Wer hath spoken largely to my fface’.

This suggests that Oxford’s friends, led by [De] Vere, were actively stirring trouble between him and Anne so that they might not produce an heir.

Unfortunately she does not specify how they went about this, but her complaint and continued childlessness suggest that they were successful.'

Anne thus turned to Norfolk for help (page 180):

'Later in the sequence of letters she also mentioned her half-brother Thomas, later 3rd Duke of Norfolk.