#themroc

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#polls#movies#themroc#70s movies#claude faraldo#michel piccoli#miou miou#béatrice romand#francesca romana coluzzi#jeanne herviale#requested#have you seen this movie poll

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023.20 : Themroc

J'ai évalué Themroc (1973), de Claude Faraldo 7/10

Film sans dialogue autre que des grognements, des cris ou des onomatopées. Film symbolique interdit initialement au moins de 18 ans, il est encré dans son époque post-mai 68. Proche du film "l'An 01", il a une mise en scène très cartoonesque, ce qui le rapproche aussi de la BD et de l'époque Hara-Kiri. Léger par sa forme, pas de prise de tête, mais profond par son message contestataire. Contre les normes sociales, contre la propriété, pour la libération sexuelle, c'est un appel a la révolte, qui se propage à travers le personnage principal joué par Michel Piccoli. Il y'a aussi un super casting, Miou-Miou, Deware, Coluche etc...

C'est un appel à devenir sauvage dans ce monde oppressif, mais avec les défauts que cela engendre : les femmes deviennent aussi des morceaux de chair, la force viril du personnage incarne une figure héroïque indépassable.

Des murs qui se brisent, la destruction du mobilier, des flics qui volent, qui se font rôtir puis manger, des décors de ruine, des ouvriers qui se tapent dessus pour un travail aliénant et absurde.

0 notes

Text

Please 🙏

@marquisdelafayetteforreal @degocraft-952

-952 @zingtimestwo-blog @sporesgalaxy

@friendly-neighborhood-sociopath

@angrymorganite930 @draw-your-ocs-as @ninjakathy @spudmen

@blackcurrantsweettea @wildcardsag

@uayv @zeojak @skil @qatheauthoress74

@just-to-comment-in-fanpages @sayruq

@lul @terry @bunnymilki

@gaymantaraysblog @cutiesncantrips

@albisluvzkaty @themroc @dullahaunts

@boopdeshmoop @aurasoulhikari

@gnollbardcreates @sarahmeeps

@sappho114 @starthistletea @dunksteinandslamough

@hashashafashasha @xliyluna

@dumbhero @numberonepartyboy

@anastasiatasou @bunnymilki @aerdeth

@gaza-evacuation-funds @ghostofanonpast @gallade-x-treme @xielians

@xsuicunee-blog @memehumor @memeuplift

@loish @lastoneout @litsy-kalyptica

@expressionmemeschallenge

The genocide in Ghazzah has caused permanent effects on those who survived it. Many Ghazzans have lost their homes, their health, and their loved ones. Many survivors are still at risk of more serious health effects due to being deprived of food, shelter, and medical care for so long. However, with swift action and support for Ghazzans, you can help them heal and avoid more suffering.

One person you can help is Suham Bader. Suham's arm was injured over a year ago, but she was not able to recieve treatment for it as her family was forced to flee their home. Without medical treatment, her bone fused incorrectly. During a year of suffering through cold and pain, Suham's condition has kept getting worse. Her parents and her uncle @hashembadr are very worried for her. If Suham does not recieve surgery soon, she will lose her arm entirely.

Hashem and his family have been fundraising for almost a year now, but they have only reached 14% of their goal so far. They urgently need funds for Suham to get the surgery she require, but donations keep stopping for days at a time. They still need to raise around £4900 to cover the price of surgery and the transfer costs.

Suham is just a kid. She's lost her home and has gone through a year of unimaginable trauma. Please, help her get the surgery she needs. It's all her family is asking right now. Your donation and sharing their campaign both make a difference in her life.

Vetted #102 by @/gazavetters

@nekomacbeth @ashirpa @relelvance @drag-on-dragoon @redphienix

@beefchurger @booblover1992 @lyctorgideon @lizardbytheriver @pallegina

@superwariomaker @zafiros @joshpeck @lukewarm-lesbian @bioh4zards

@familyguyyaoimoments @fogsvr @lucky-lesbian @noorionoodles @zapmolcunos

@3lawzdef1ant @danaharlowe @prettyfatigue @spamtime @chingaderita

@b1sexual @chemiosmotic @kashisun @anarcho-dykeism @marsupial1998

@jinnazah @pomodoko @theygender @kagrenacs @professionalchaoticdumbass

@imlizy @duncebento @littlestpersimmon @samuraisharkie @bisexuel

@captain-lovelace @spideypeterparkers @damiel-of-real @pettydisco @underthejollyroger

@a-shade-of-blue @galactic-mermaid @noble-kale @ramshackledtrickster @imjustheretotrytohelp

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Kosmos Mail from Karsten.Haecker

… mehr Tage als Essen übrig. Jetzt wird gespart. Oder ich brat mir ‘n Hiker (Themroc-mäßig). 😋 Haltet durch ihr da draußen. 😎

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Forgive me, tagging for reach again, please share I beg you

@marquisdelafayetteforreal @degocraft-952 @zingtimestwo-blog @sporesgalaxy @friendly-neighborhood-sociopath @angrymorty @draw-your-ocs-as @ninjakittens @spudmen @blackcurrantsweettea @wildcardsag @uayv @zeojak @skil @qatheauthoress74 @just-to-comment-in-fanpages @sayruq @lul @terry @bunnymilki @gaymantaraysblog @albisluvzkaty @themroc @dullahaunts @boopdeshmoop @aurasoulhikari @gnollbardcreates @sar-soor @sappho114 @starthistletea @dunksteinandslamough @hashashafashasha @xliyluna @dumbhero @numberonepartyboy @anastasiatasou @bunnyfood @aerdendios @gazavetters @ghost-roads @gallade-x-treme @xielianss @xsuicunee-blog @memehumor @memeuplift @loish @lastoneout @litsy-kalyptica @expressionmemeschallenge

Single mother with 2 injured children trapped under IOF fire in north Gaza—evacuation and treatment needed NOW!!

Maha and the children were not able to evacuate before the IOF surrounded their area. They are under fire NOW.

Little Khalil has been injured after the lOF rigged a nearby house to explode. Then while seeking shelter, the lOF fired gas canisters at them. They were unable to escape the gas, and now Joan is struggling to breathe!

They need funds for transportation, rent, and treatment for Joan’s breathing problems! In total, this means the amount they require is $2,300 USD. However, we are going to split this goal up. We will focus first an raising funds for transport and rent, totaling $1,700 USD

PLEASE share the family's situation and GFM link across all your social media accounts!

Current: €26,655 EUR

New temporary goal: €28,148 EUR

Need to raise: $1,700 USD, about €1,493 EUR

#ngu*#gaza genocide#gaza strip#free gaza#gaza under attack#ahs murder house#from the river to the sea palestine will be free#maha ibrahim#palestinian genocide#stop the genocide#stop gaza genocide#stop genocide#stop gazan genocide#save rise of the tmnt#end genocide#supernatural#save the children#gaza support#israel is committing genocide#israeli war crimes#save north gaza#north gaza aid#aid for palestine#aid for north gaza#palestine aid#aid for gaza#humanitarian aid#gaza aid#support

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Themroc (1973)

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Themroc - 1973 (Trailer)

1 note

·

View note

Text

End of month update - March

Hello, all! This is the end-of-month update, where I post Tumblr’s current top four films that have received the highest percentage of “yes,” “no,” and “haven’t even heard of this movie” votes.

As of today, the top four films with the highest percentage of “yes” votes are:

Finding Nemo (2003) | Shrek (2001) |The Lion King (1994) | Toy Story (1995)

Next, the top four films with the highest percentage of “no” votes are:

Mulan (2020) | Fifty Shades of Grey (2015) | Sausage Party (2016) | Pinocchio (2019)

Finally, the top four films with the highest percentage of “haven’t even heard of this movie” votes are:

Seer the Movie 3: Heroes Alliance (2013) | Gaz Bar Blues (2003) | Faat Kiné (2001) | Zumiriki (2019) | Kisapmata (1981)

This top four changed through the new additions of Gaz Bar Blues (2003), which replaced Kisapmata (1981).

That’s it for March’s end-of-month update! Remember that you can view last month’s update by clicking here. Additionally, you can view the full ranked Letterboxd lists of movies that have come up on this blog by clicking the following links:

This list is ranked from highest-to-lowest percentage of “yes” votes.

This list is ranked from highest-to-lowest percentage of “no” votes.

This list is ranked from highest-to-lowest percentage of “haven’t even heard of this movie” votes.

Remember to vote on the polls that are currently running: Pinocchio (1940) | The Adventures of Food Boy (2008) | Sonic: Night of the Werehog (2008) | Pokémon the Movie: Diancie and the Cocoon of Destruction (2014) | Carry On Doctor (1967) | The Grapes of Wrath (1940) | Underworld: Blood Wars (2016) | A Shot in the Dark (1964) | Elgar: Portrait of a Composer (1962) | Gamera: Guardian of the Universe (1995) | Rebecca (1940) | Taxi (2015) | The Namesake (2006) | Pajama Party (1964) | Eating Raoul (1982) | The Mortal Storm (1940) | Themroc (1973) | District 9 (2009) | The Lovely Bones (2009) | Return to Oz (1985) | Dance, Girl, Dance (1940) | We Are the Night (2010) | House of Tolerance (2011) | Kandukondain Kandukondain (2000) | Beverly Hills Cop (1984) | Fantasia (1940) | (A)sexual (2011) | The Mark of Zorro (1940) | Zack Snyder's Justice League (2021) | Knock Knock (2021) | The Bank Dick (1940) | Soft Top Hard Shoulder (1992) | In the Loop (2009) | Wild Rose (2018) | Girl with a Suitcase (1961)

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#rainerwernerfassbinder #klauslemke #herbertachternbusch #andreitarkovsky #mirandajuly #miriamcahn #marlenedumas #gabriellekbrown #agnesmartin #senganengudi #davidhammons #themroc #permanentvacation #erasorhead #nftart #nft #randomircosmotisch #sketchbookdrawing #sketchbook #skizzenbuch https://www.instagram.com/p/CpsyezgIa1i/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#rainerwernerfassbinder#klauslemke#herbertachternbusch#andreitarkovsky#mirandajuly#miriamcahn#marlenedumas#gabriellekbrown#agnesmartin#senganengudi#davidhammons#themroc#permanentvacation#erasorhead#nftart#nft#randomircosmotisch#sketchbookdrawing#sketchbook#skizzenbuch

0 notes

Text

Penne Arrabbiata - Eine kleine Mafia Geschichte

Penne Arrabbiata – Eine kleine Mafia Geschichte

von Holger Obenaus Die 80iger und frühen 90iger waren von drei Dingen geprägt. Schnelle Autos, gute Schüsse (wie man in Köln sagte) und Mafia-Filme. Die Kreise, in denen ich mich zu dieser Zeit rumtrieb, durchlebten Schneestürme im Hochsommer und Cold Turkey im Winter. Die besten Filmzitate passten auf jede Lebenslage und Joe Pesci war mein persönlicher Held! Unser Leben war am Limit, der…

View On WordPress

#Hans Maria Jürgen#Henry Hill#Holger Obenaus#Joe Pesci#Köln#Kriminelles Millieu#Organisierte Kriminalität#Penthouse Unicenter Köln#Plaat#Scorsese#Themroc#Tony Montana#Uni-Center#Uni-Center Penthouse

0 notes

Photo

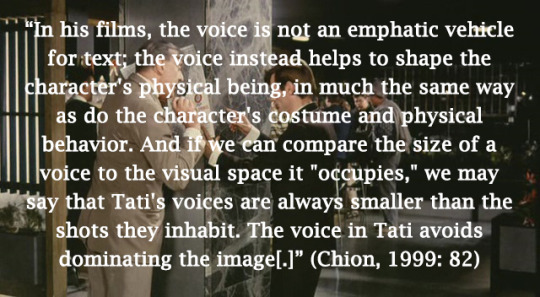

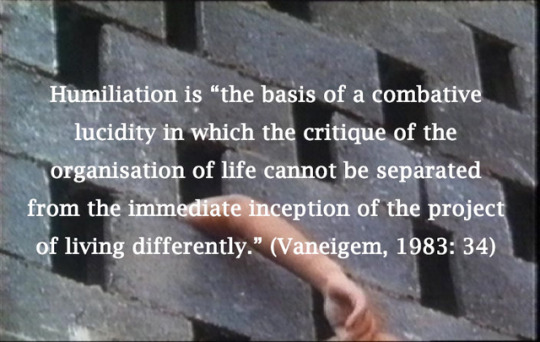

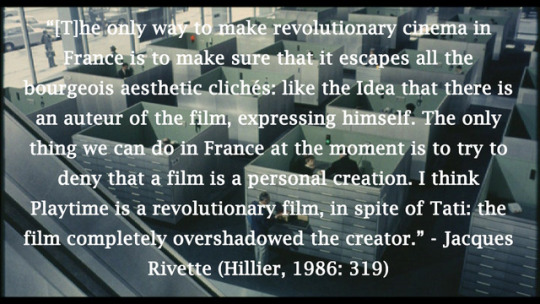

A 2015 film.factory essay of mine has appeared online. I put it there. It is about how the marvellous films Playtime and Themroc reflect ideas about urbanism, modernity, and revolution through their sound design. Fascinating!

#Playtime#Themroc#jacques tati#claude faraldo#situationists#urbanism#sound design#film.factory#raoul vaneigem#quotes#french cinema

1 note

·

View note