#the white ribbon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Charcoal on Paper. 2019

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The White Ribbon

Albert Lynch

oil on canvas

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe I should have a Young Torless and The White Ribbon double feature. Have a bad time.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The White Ribbon (2009) dir. Michael Haneke

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The White Ribbon (2009) dir. Michael Haneke

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE WHITE RIBBON (2009) dir. Michael Haneke

#the white ribbon#michael haneke#moviegifs#filmedit#cinematicsource#filmgifs#dailyworldcinema#dailyflicks#cinemaspam#blackandwhiteedit#usersugar#useradie#usergina#userelissa#usercande#userlera#userfilm#useravalone#my edit#2009

217 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Will she take it? Can I drag her even lower?”

Susanne Lothar in The White Ribbon [Das weiße Band] (2009).

#the white ribbon#susanne lothar#michael haneke#gif edit#movie edit#film edit#german film#gifs by me#great character#counting down 'til susanne's bday

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

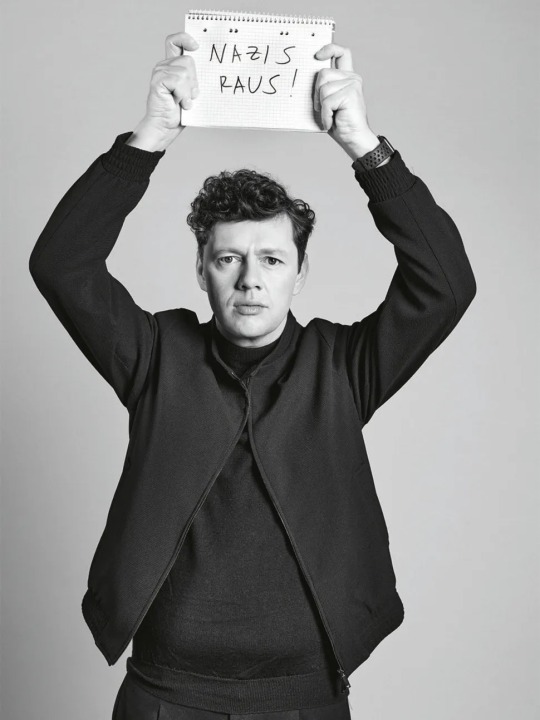

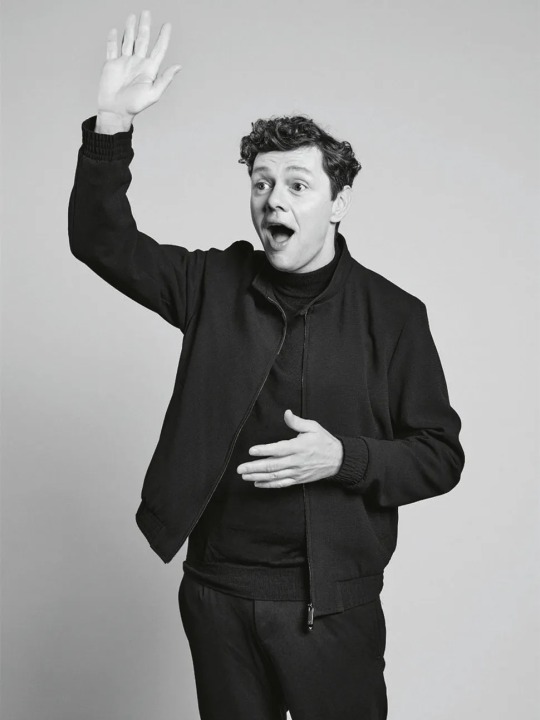

Christian Friedel for Süddeutsche Zeitung

Detailed Explanation about the photos below the cut:

This is a famous column of the news paper where they ask actors to answer the questions only with facial expressions/ poses etc.

The 10 questions were:

1. You say about yourself that you have a “historical face”. Could you show us?

2. Going to a demonstration or staying home?

3. Your mood at the Berlinale?

4. What interests you of horror?

5. Since your first movie was The White Ribbon, how can you top that?

6. Private: Cinema or Netflix?

7. How does it look like when you go out fully?

8. You learned how to ride for The Zone of Interest. How do you feel on a horse?

9. What does an actor do to combat a growing ego?

10. How do you react when something does not go according to your plan?

#christian friedel#süddeutsche zeitung#sz#interview#the zone of interest#photoshoot#the white ribbon#babylon berlin#germany#woods of birnam#german actor#hamlet#macbeth#dorian#düsseldorfer schauspielhaus#shakespeare#oscars 2024#reinhold gräf#period drama#world war 2

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

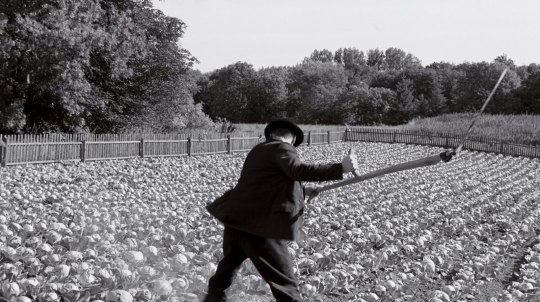

Film #916: 'The White Ribbon', dir. Michael Haneke, 2009.

If there's one mood that unites everything produced by the Austrian director Michael Haneke, it's that of disquiet. He gained global notoriety for his alarming and confrontational Funny Games (1997), which he remade in English in 2007, and achieved a string of successes with bleak films such as The Piano Teacher (2001), Caché (2005), and Amour (2012), the latter of which gave Haneke his first Academy Award nomination for Best Director. The White Ribbon, which was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film, is also a tremendous example of Haneke's stately and discomforting style of filmmaking. Like many of his feature films, it's about a world in which violence erupts suddenly and seemingly without cause.

In a small German village in 1913, we follow the stories of three families - headed, respectively, by the doctor, the pastor, and the baron - and the experiences of the midwife and the schoolteacher whose lives intersect with the events of the village. In the opening moments, the doctor rides up to his gate at speed. The horse falls in a spectacular fashion, and the doctor is thrown, injuring himself so badly that he will spend months, unseen, in hospital. Someone has stretched a wire between two trees, but before an investigation can begin, the wire has been removed. Further accidents befalls the town: a woman is killed falling through a rotten floor; her son takes vengeance on the baron by destroying the cabbage fields on the day of the harvest festival. The baron's son goes missing that same day, and is found injured the next morning, in the sawmill where the woman died. A barn burns down.

Haneke's screenplay chooses to leave these events mostly unexplained, but the violence spreads. The pastor's daughter, humiliated in front of her siblings, gets vengeance by murdering his parakeet. The steward's son at the baron's estate jealously attacks the baron's son. The midwife's son is also abducted, but his injuries are more severe and the boy may go fully blind. Whether his recovery is helped or hindered by the doctor is an open question, as the doctor has abruptly ended his affair with the midwife. The parade of mysteries and recriminations is so unrelenting that, when a scene is suddenly interrupted by the announcement that Archduke Ferdinand has been shot, we realise that we'd completely forgotten that was on the way. The outbreak of the war understandably eclipses all other concerns, but stymies the audience, who are denied any real answers - especially as the story culminates with several main characters completely disappearing.

'Watch who comes to help', the film seems to instruct us, and we gain partial access to the film's events through the eyes of the schoolteacher, our narrator. Suspicious at the interest the pastor's children have taken in Karli, the blinded boy's, convalescence, the schoolteacher intuits that the children of the village are responsible for many of the mishaps. There is certainly no shortage of motive against the men who run the town - the doctor abuses his daughter, the pastor severely punishes his children to try and keep them pure, the baron seems indifferent to everyone who works his land or populates his life - but many of these details are unknown to the schoolteacher, or to the gossips who formulate a different theory about the midwife and the doctor. What the outbreak of war does mean is that the schoolteacher is drafted, never returning to the village again and unable to provide any closure.

After watching the film, I discussed with the people in our viewing party our best guesses of whodunit. Our immediate suspicions also fell on the children of the village, because we'd been given enough insights into what was really going on that the schoolteacher's suspicions seemed well-founded. Despite this, I can't be entirely sure, which is certainly the point of Haneke's film. The idle speculation of the village's gossips is, on the face of it, as plausible as any other explanation, and this ambiguity is exacerbated by the extremity of some of the events. Children can burn down a barn, of course. They could possibly descend to blinding another child. They probably couldn't make multiple adults disappear, though... could they? Do we even think those disappearances are malevolent? Or are they the reasonable actions of the doctor, a man who fears he's about to be exposed as a molester, and the midwife, a woman who sees a village spiralling out of control and threatening her son?

Haneke is no stranger to this type of ambiguity. Caché revolves around a family being threatened by anonymous videotapes, but although we get some good suspicions of who is responsible, we can never be entirely sure of it, or even that the videotapes are meant to be menacing at all. In The White Ribbon, a similar type of uncertainty occurs. The film's narrative is even framed as the remembrances of an old man, so we can't even be certain that details aren't embellished within the world of the story, despite the precision of the film's black and white cinematography and objective, locked-off shot framings.

The experience of the film is also a test of the viewer's ability to recall and differentiate information. Is the girl fired from the baron's employ the same as the farmer's daughter, who was earlier described as having a job that keeps the family afloat? For a film that takes so much care with its imagery and sound, it's surprisingly disorienting - even Roger Ebert's review mistakenly remembers the murder of a child. We're eased into The White Ribbon as an experience of a whodunit - mysteries are posed, and we've been taught that with careful attention we can tease apart the riddles a film presents. But, as with Haneke's other films, no amount of note-taking or diagramming can explain things beyond the shadow of a doubt.

So what is the film, at long last, about? Haneke described the film in an interview as being about the inhumanity of rigid ideas, and how these strong moral ideas become the basis for evil. Ironically, the pastor attempts to teach his children right and wrong, and punishes them for even the most minor of infractions, not realising that this treatment might be causing his children to commit even worse sins. Meanwhile, the adults of the village, supposedly old enough to know right from wrong, inflict their own kinds of atrocities on each other and the children.

The results of this inhumanity spare nobody. Some characters, either explicitly or implicitly, realise that the only way to save themselves from the creeping damage, is to leave entirely. This could explain what happens to the midwife and her son although, of course, Haneke will not tell us for sure. It certainly explains the baroness's decision to leave her husband, shortly before the Archduke's assassination is announced. "I'm going so that my children don't grow up in surroundings dominated by malice," she tells her astonished husband, confessing that she has fallen in love with another man who, evidently, shows more interest in her and the children than her husband does.

It's not just the floor of the sawmill that has rotted away - "it's all rotten", a character warns another. When these horrible events befall the town, there is a natural tendency to seek answers, and to punish the culprits, but Haneke suggests that there is no easy way of doing this, and perhaps no point even if there was. The problem is not entirely with the children, if they were the ones responsible for doing these things, but rather with rigid morals handed down, which stunt them and drive them to further violence. The pastor, suspecting his son is masturbating, has him tied to his bed each night until his cravings pass. His children wear white ribbons when they need to be reminded to preserve their innocence, but these states of grace are short-lived, and the pastor relents and gives his children communion anyway. He learns nothing about what he is responsible for, and when he is confronted by the schoolteacher in one of the final scenes, he threatens to have the schoolteacher imprisoned.

The power structures of the village have rotted through, and tainted another generation who, having learned the difference between right and wrong, appoint themselves magistrates. In order to achieve this, though, they have to injure others to protect themselves, and the cycle continues. The outbreak of war doesn't stop this cycle - Haneke seems to see it as a different outlet of the same eternal poisons.

The White Ribbon is, funnily enough, one of the more accessible of all Michael Haneke's films, if you can stomach the oppressive feeling that lies over everything. It's less explicit than Funny Games, for example - most of the violence in this film is offscreen, which makes the moments of violence we do see all the more jarring - and more eventful than Caché. Like his other films, though, it lingers: knowing the message that Haneke seems to be trying to send doesn't put The White Ribbon to rest. "To function, art has to rub salt in the wounds", he says. "What interests me when I read a book or a movie are works that make me uneasy, that make me think of new problems, instead of those that reassure me. The films that I retain are those that disturb me."

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The White Ribbon

directed by Michael Haneke, 2009

#The White Ribbon#Das weiße Band Eine deutsche Kindergeschichte#Michael Haneke#movie mosaics#Fion Mutert#Ulrich Tukur#Leonie Benesch#Ursina Lardi

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The White Ribbon

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

#aesthetic#pink#coquette#girlblogging#girlhood#moodboard#korean#hyper feminine#makeup#femininity#divine feminine#im just a girl#i am just a girl#just girly thoughts#just girly posts#just girly things#girly blog#girly#girly aesthetic#ribbons and bows#girly things#pink aesthetic#soft aesthetic#soft girl#sparkles#softcore#pastel#pink and white#angel#angelic

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: Two photos at slightly different angles of a ribbon seal sitting on an ice floe. The background is of pure blue water with smaller ice floes in it.] via

10K notes

·

View notes