#the sacking of Carthage

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

An easy way to remember the salt affecting the soil is to remember what the Romans supposedly did to the people of Carthage.

After the Roman legions won the Third Punic War in 146 BCE, they sacked the city. Burned Carthage to the ground—which there is historical record of happening. The added myth to the sacking that became popular was that the Roman general of the campaign ordered the ground to be salted.

The reasoning was that salting the ground would ensure that no crops would grow ensuring that the city of Carthage would never rise again.

Salt is protective and purifying, yes. But not for the soil.

WITCHY PSA

STOP SALTING THE GROUND.

Don't cast a circle of salt in the dirt, don't salt the soil to cleanse it, use something else. Eggshells, rosemary, wood ash, etc, but not salt!

Salt will mess up the soil and make it impossible for anything to grow for generations. On that same note, don't litter while doing witchcraft! Stop burying non-biodegradable satchels and jars or throwing them in the lake/ocean!

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

When the Greeks sacked Troy, Aeneas retreated to Mount Ida, carrying his father Anchises on his shoulders and carrying his son Ascanius. His wife Creusa died in flight. He reigned for a time in Ida, then undertook a long voyage across the Mediterranean.

This Trojan hero went through several adventures in which different deities participated including his mother, Venus (Afrodita) . After his father's death in Sicily, a storm blew him astray and washed him onto the shores of Carthage.

Aeneas tells Dido the misfortunes of the Trojan city. Oil on canvas by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1815) Louvre, Paris.

With the intervention of the goddess Venus, queen Dido of Carthage fell in love with Aeneas and wanted them to marry, uniting their lineages. But Jupiter opposed it and sent Mercury to warn him that he must continue his journey and fulfill his destiny.

Dido, outraged at being abandoned , cast a curse declaring that her people and the people descended from Aeneas would be enemies. After this, she stabbing herself with a sword on a pyre.

Death of Dido. Oil on canvas by Guercino (1631)

Back in Sicily, Aeneas celebrated great funeral games in memory of his father, who appeared to him to tell him that he must go to Cumae and descend into the underworld. In Cumae, Aeneas succeeded in having the Sibyl open the gates of Hades for him.

There he met the shadow of Dido, but he also saw his father, who in the Elysian Fields revealed to him the glorious destiny of the people he was to found in Italy.

Aeneas and the Cumaean Sibyl. Oil on canvas by François Perrier (1646)

He reached the mouth of the Tiber and finally entered a city called Pallantium on the Palatine Hill. There, after going through several epic situations, he married Lavinia, only daughter of Latinus, king of the Latins, and founded the city of Lavinium, named after his wife.

Aeneas disappeared in the middle of a storm and was taken to Olympus and crowned by his mother Venus. His eldest son Lullius, from whom the Julii descend, founded Alba Longa the hometown of Romulus and Remus.

According to Livy, Lullius is the son of Aeneas and Lavinia, and seems to distinguish him from Ascanius son of Aeneas and Creusa. Silvius, son of Lullius, succeeded him on the throne of Alba Longa. Dionysius of Halicarnassus is the one who says that Silvius was the son of Aeneas and Lavinia, and therefore half-brother of Lulilus (Ascanius)

Years later, Numitor, maternal grandfather of Romulus and Remus and direct descendant of Silvius would be king of Alba Longa

Roman bas-relief, 2nd century: Aeneas lands in Latium leading his son Lullius (Ascanius); the sow identifies the place to found his city : Alba Longa

Over time, coming into contact with civilizations in the Eastern Mediterranean, the Romans realized that while everyone else had legends of heroes, epic wars, and several divinities interacting with humans at each event, they only had Mars in their founding story; twins thrown into a river, suckled by a wolf in a cave, adopted by a humble shepherd. And one of the twins ends up dying in a fight with the other.

Romulus and Remus, suckled by the wolf, found by Faustulus on banks of Tiber. Fresco by Giuseppe Cesari (1568-1640)

Augustus commissioned the great Roman poet Virgil to create a epic worthy of Rome, but without annulling its legendary founding history.

Through the Aeneid, Rome acquired a prestigious past; a mystical explanation of the three Punic Wars and the destruction of Carthage. Julia gens obtained a divine origin, giving even more legitimacy to the ruling dynasty. Furthermore, this epic exalts the Roman virtues that Augustus so wanted to restore and impose by law.

According to Roman historians, Augustus' sister Octavia faint from emotion upon hearing Virgil reading the Aeneid.

Virgil Reading the Aeneid to Augustus and Octavia. Neoclassical painting by Jean-Joseph Taillasson, 1787

In the story of the Trojan War as told by Homer, Aeneas appears as a secondary character, after heroes such as the Greek Achilles or the Trojan Hector. Meanwhile Virgil made him a protagonist in an epic that linked the fall of Troy and the founding of Rome.

The Siege of Troy. Oil on canvas by French School ( 17th century)

#ancient rome#history#mythological painting#oil painting#oil on canvas#fresco#the aeneid#roman empire#greco roman

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rich Votive Deposit Discovered in Sicily's Valley of the Temples

At least sixty terracotta figurines, female protomes, and busts, oil lamps, and small vases, a rich votive deposit of bronze fragments were found in the Valley of the Temples in Agrigento, on the southwest coast of Sicily.

The objects were found in House VII b, which forms part of the housing complex north of the temple of Juno. The campaign is fully funded and supported by the Sicilian Region through the Valley of the Temples Archaeological Park, directed by Roberto Sciarratta, and is led by archaeologist Maria Concetta Parello.

In an announcement published by the Sicilian Region Institutional Portal: “The findings allow us to understand the dynamics of the destruction of Agrigentum in 406 BC by the Carthaginians, when the inhabitants had to flee in exodus towards the city of Gela.”

The votive deposit, which would appear to have been arranged above the destruction levels of the house, may tell the story of the time when its objects were recovered by the Akragantines after the destruction. To define with certainty the function of the interesting deposit will require further research, paying close attention to the stratigraphic connections between the deposit and the living and abandonment levels of the house.

The Valley of the Temples forms part of the ancient city of Agrigentum, situated in the province of Agrigento, Sicily. Since 1997, the Valley of the Temples (covering 3212 acres) has been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

According to the Greek historian, Thucydides, Agrigentum was founded around 582-580 BC by Greek colonists from Gela in eastern Sicily, with further colonists from Crete and Rhodes. It was routed by the forces of Carthaginian general Himilko in 406 B.C. Agrigento’s residents fled to nearby Gela when Himilko sacked their city, but then he took Gela too. All of the Greek colonies on Sicily fell to Himilko and were made vassals of Carthage. Punic primacy would not last long, however. Timoleon of Corinth defeated Carthage in Sicily and liberated the Greek cities in 399 B.C.

By Leman Altuntaş.

#Rich Votive Deposit Discovered in Sicily's Valley of the Temples#Valley of the Temples in Agrigento#temple of Juno#terracotta figurines#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient sicily#ancient greece#greek history#greek art

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun fact: if one looks up the poems and a map, they can find every single location of The Odyssey. That's literally how Schliemann, an amateur, found Troy in an era everyone was convinced it never existed: he read the Homeric description, looked on a map which place on the Anatolian west coast resembled it, and dug on Hisarlık hill, finding not one but MULTIPLE settlements one over the other.

And we can do the same for almost every other location:

Troy: Truva archeological site, Hisarlık, modern day Turkey.

Ismara, ally of Troy, sacked by Odysseus while the army was away on one last attempt to save the city and was now marching back after finding out it had already fallen because he didn't feel like paying for the food: near modern day Maroneia-Sapes, in Greek Thrace, or possibly the same place as ancient Maroneia in the same place (Odysseus met the founder of Maroneia at Ismara, after all).

Land of the Lotus Eaters: Syrtes Gulf, between modern day Tunisia and Libya, or Djerba, an island in modern day Tunisia right off the Syrtes coast.

Land of the Cyclops: Sicilyan coast, near Mount Etna (another place where you could find a different group of Cyclops being inside the vulcan, working in Ephaestus' forge). Remember this gorgeous island and Italy in general, we'll be back more than once - the giant boot of the Italian peninsula literally bars his way home after the mishap with the winds. But Achememeis, one of Odysseus' men, was too slow to run back to the ships and was left for dead. But don't worry, other voyagers will find him and save him after he survives the stroke at the identity of his saviours.

Aeolia, the floating island of the Wind God Aeolus: Apparently it's in the Aeolian Islands off the coast of Sicily. Guess he decided to stop there at some point...

Laestrygonia, the land of the giants: Gallura, in modern day Sardinia, inhabited in historic times by a Nuragic people called the Lestriconi. And now you know how they made such short work of a fleet of veterans from the Trojan War, it was Sardinians (if you are Italian or from Corsica, you get it. If you are French not from Corsica, until relatively recently Sardinians and Corsi were the same people, you know how hard it was to fully conquer the Island of Beauty. If you aren't any of the above, just know that Rome took over Corsica and Sardinia in 238 BC and Nuragic pirates still raided Pisa in 10 AD. Or that Napoleon was born and raised in Corsica, and it was the Sardinians to give him his only defeat in direct battle until Leipzig).

Eea, Circe's island: Circeo promontory in Italy, that possibly used to be an island in the Bronze Age. Alternatively the nearby island of Ponza.

Land of the Cymmerians: Phlegraean Fields near Naples, Italy.

Entrance to the Underworld: Lake Avernus (lit. HADES LAKE) in the Phlegraean Fields. Presumably it was the closest entrance, considering the Acheron is an actual river in Greece...

Nest of the Syrens, western flock (the Argonauts faced another flock in the Black Sea): shoals near Sorrento, just south of the Phlegraean Fields.

Scylla and Charybdis: The Strait of Messina with its monstrous tidal waves. To be precise, Scylla is the Calabrian part of the strait, traditionally right under the town of Scilla (named after the nymph turned monster), while Charybdis is on the Sicilian coast an arrow shot away from Scylla, right where you can STILL find a small whirpool. And with this, Odysseus got past Italy, and, most importantly, avoided the fleet of TROJAN REFUGEES currently sailing toward the sacred land of Enotria, also in Italy - they had instructions from a prophet, and after spooking Ithaca to reach their prophet in nearby Epyrus took the long way around Sicily, stopping once in Sicily to pick up Achememeis (told you he got a stroke at who saved him), then at Carthage, and finally at Lake Avernus. Never knowing that Odysseus killing the Syrens left their passage safe.

Trinacria, where the cattle of Helios grazed: it's literally another name of Sicily. To be precise they're in the north east coastal plains, just north of the Land of the Cyclops.

Ogygia, Calypso's island: remember when I said that ALMOST every place could be identified? Well this is the reason, we only know Ogygia was a paradisiac yet isolated place somewhere in the Western Mediterranean, so far away from Olympus that Hermes complained - and the paradisiac part can be thrown away as Calypso was a goddess and free to modify her home as she pleased. Ancient traditions claim it's Gozo, an island near Malta, while others claim it's Perejil, a small rocky islet in the middle of the Straits of Gibraltar contended by Morocco and Spain (my money is on Prerejil, if only because how far it is).

Scheria, the many-named island of the Phaeacians that rescued Odysseus from Poseidon's last storm and ferried him to Ithaca on a magic ship: Corfu AKA Korkyra, modern day Greece.

Ithaca: Ithaca, Greece.

If you are a fan of the myths or a Winion, now you know where everything happened.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Opinion: I'm a Roman senator. I think Scipio Aemilianus went too far when he sacked Carthage.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

idril as aeneas carrying her son on her back and her husband out of the wreckage of her sacked city. turgon as the lost one who chose to remain behind idril-túor-earendil as the living lares of the gondolindrim. gondolin as troy breached by a false symbol of friendship. túor as cassandra whose warnings go unheard, gone away in the waves and never returned to her homeland.

elwing, her guards and the silmarillion as aeneas and the lares AGAIN. elwing as dido throwing herself from a tower in such despair that the gods themselves (her kindred) witness it mourn it and hold themsevles accountable for it. sirion as carthage where refugees come to rest the place of peace and love where mariners are not allowed to rest lest their divine quests be set aside and their people's hopes falter. classics side of the tolkien fandom is this anything.

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chronological framework of the Second Trojan War (1193-1184)

A rough chronology of the Second Trojan War, including events leading to it. This will be fleshed out as I develop the biographies of the main characters. Comments & criticism are welcome.

1215 | MARRIAGE OF PELEUS & THETIS on the slopes of Mount Pelion. Eris throws the apple of discord at their wedding feast and the goddesses quarrel for the prize of being the fairest. Zeus takes the apple and declares that the matter shall be settled later.

1214 | OATH OF TYNDAREUS in Sparta. Tyndareus announces it is time for his daughter Helen to marry. Many suitors show up. Tyndareus makes them swear an oath to assist Helen's chosen husband in time of need. Menelaus is chosen and marries Helen.

1209 | JUDGMENT OF PARIS on the slopes of Mount Ida. Zeus, impressed by Paris's fairness, sends him Hera, Athena and Aphrodite, for him to judge which is the fairest. Paris chooses Aphrodite, thus gaining the promise of the love of Helen.

1204 | PARIS ABDUCTS HELEN. Paris and Aeneas, with a contingent of men, visit Sparta. Menelaus welcomes him but must leave for Crete for his grandfather King Catreus's funeral. Helen is smitten with love and leaves with Paris, taking her treasury with her. They detour south of Crete, and go to Cyprus and Phoenicia. Menelaus invokes the oath of Tyndareus and summons his allies. Calchas predicts a war with Troy and that Achilles will be needed to win it. Thetis fears for her son's life and hides him in Scyros.

1200 | FIRST GATHERING OF THE FLEETS in Aulis. Calchas predicts the war against Troy will last ten years. EXPEDITION TO MYSIA. Thersander, king of Thebes, is slain. Telephus is wounded by Achilles. The Greek fleet is dispersed by a storm. Many ships are lost and the Greeks take time to recover.

1193 | SECOND GATHERING OF THE FLEETS in Aulis. Achilles heals Telephus, who reveals the way to Troy. Sacrifice of Iphigenia. Philoctetes is left in Lemnos. Achilles slays Tenes. Failed diplomacy attempt by Menelaus & Odysseus. Protesilaus is slain by Hector. THE WAR BEGINS. Cycnus is slain by Achilles.

1193-1185 | The Greeks, especially Achilles and Ajax the greater, carry out multiple campaigns around Troy to cut Troy off from supplies and allies. Many cities are sacked in both Thrace and Asia Minor. During that time, the Greek beachhead near Troy is fortified but never fully manned. Ajax the greater manages to secure and exploit farmland on the Thracian peninsula for the benefit of the Greeks.

1191 | Achilles ambushes and kills Troilus, young son of Priam, because of a prophecy saying that if he reached the age of 20, Troy would never fall.

1190 | Death of Palamedes. His father Nauplius, denied justice, encourages the Greek wives to be unfaithful.

1188 | A small earthquake hits Troy, killing Paris's sons.

1187 | Ajax the greater and Achilles play a game of petteia on the battlefield, saved in extremis by Athena.

1186 | Lack of supplies and mutiny among the Greeks. Intervention of the Wine Growers.

1185 | THE WRATH OF ACHILLES. Deaths of Patroclus and Hector. Intervention of the Amazons.

1184 | Intervention of the Ethiopians. Death of Achilles. The Trojan horse and the FALL OF TROY. Athena is angered against the Greeks.

1184-1175 | THE RETURNS. Many Greek commanders suffer tragedy and turmoil during their return from Troy.

1177 | Aeneas reaches Carthage.

1175 | Odysseus reaches his home in Ithaca at last, ending the longest of the returns.

#classical mythology#greek mythology#ancient greece#greek gods#greek heroes#mythology#trojan war#chronology#paris#achilles#ajax#helen

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

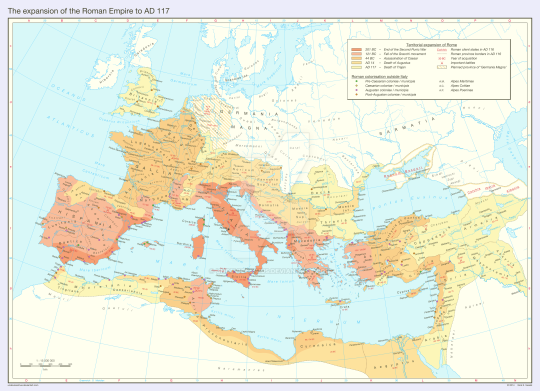

The expansion of the Roman Empire to AD 117.

by Undevicesimus

From its humble origins as a group of villages on the Tiber in the plains of Latium, Rome came to control one of the greatest empires in history, reaching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Tigris and from the North Sea to the Sahara Desert. Its extensive legacy continues to serve as a lowest common denominator not only for the nations and peoples within its erstwhile borders, but much of the modern world at large. Roman law is the foundation for present-day legal systems across the globe, the Latin language survives in the Romance languages spoken on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and beyond, Roman settlements developed into some of Europe’s most important cities and stood model for many others, Roman architecture left some of history’s finest manmade landmarks, Christianity – the Roman state religion from AD 395 – remains the world’s dominant faith and Rome continues to feature prominently in Western popular culture… Rome rose in a geographically favourable location: on the left bank of the Tiber, not too far from the sea but far enough inland to be able to control important trade routes in central Italy: southwest from the Apennines alongside the Tiber, and from Etruria southeast into Latium and Campania. In later ages, the Romans always had much to tell about the founding and early history of their city: tales about the twin brothers Romulus and Remus being raised by a she-wolf, the founding of Rome by Romulus on 21 April 753 BC and the reign of the Seven Kings (of which Romulus was the first). According to Roman accounts, the last King of Rome – Tarquinius Superbus – was expelled in 510 BC, after which the Roman aristocracy established a republic ruled by two annually elected magistrates (Latin: pl. consulis) with the support of the Senate (Latin: senatus), a council made up of the leaders of the most prominent Roman families. Often at odds with their neighbours, the Romans considered military service one of the greatest contributions common people could make to the state and the easiest way for a consul to gain both power and prestige by protecting the republic. The Romans booked their first major triumph by conquering the Etruscan city Veii in 396 BC and went on to defeat most of the Latin cities in central Italy by 338 BC, despite the Celtic sack of Rome in 387 BC. Throughout the second half of the fourth century BC, the republic expanded in two different ways: direct annexation of enemy territory and the creation of a complex system of alliances with the peoples and cities of Italy. Shortly after 300 BC, nearly all the peoples of Italy united to stop Roman expansion once and for all – among them the Samnites, Umbrians, Etruscans and Celts. Rome obliterated the coalition in the decisive Battle of Sentinum (295 BC) and thus became the strongest power in Italy. By 264 BC, Rome controlled the Italian peninsula up to the Po Valley and was powerful enough to challenge its principal rival in the western Mediterranean: Carthage. The First Punic War began when the Italic people of Messana called for Roman help against both Carthage and the Greeks of Syracuse, a request which was accepted surprisingly quickly. The Romans allied with Syracuse, conquered most of Sicily and narrowly defeated the Carthaginian navy at Mylae in 264 BC and Ecnomus in 256 BC – the largest naval battles of Antiquity. Roman fleets gained a decisive victory off the Aegates Islands in 241 BC, ending the war and forcing the Carthaginians to abandon Sicily. Taking advantage of Carthage’s internal troubles, Rome seized Sardinia and Corsica in 238 BC. Rome’s frustration at Carthage’s resurgence and subsequent conquests in Spain sparked the Second Punic War, in which the Carthaginian commander Hannibal crossed the Alps and invaded the Italian peninsula. The Romans suffered massive defeats at the Trebia in 218 BC, Lake Trasimene in 217 BC and most famously at Cannae in 216 BC where over 50,000 Romans were slain – the largest military loss in one day in any army until the First World War. However, Hannibal failed to press his advantage and continued an increasingly pointless campaign in Italy while the Romans conquered the Carthaginian territory in Spain and ultimately brought the war to Africa. Hannibal’s army made it back home but was decisively defeated by Scipio Africanus at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, securing Rome’s hard-fought victory in arguably the most important war in Roman history. Firmly in command of much of the western Mediterranean, Rome turned its attention eastwards to Greece. Less than fifty years after the Second Punic War, Rome had crushed the Macedonian kingdom – an erstwhile ally of Hannibal – and formally annexed the Greek city-states after the destruction of Corinth in 146 BC. That very same year, the Romans finished off the helpless Carthaginians in much the same way, burning the city of Carthage to the ground and annexing its remaining territory into the new province of Africa. With Carthage, Macedon and the Greek cities out of the way, Rome was free to deal with the Hellenic kingdoms in Asia Minor and the Middle East, the remnants of Alexander the Great’s empire. In 133 BC, Attalus III of Pergamum left his realm to Rome by testament, gaining the Romans their first foothold in Asia. As the Romans expanded their borders, the unrest back in Rome and Italy increased accordingly. The wars against Carthage and the Greeks had seriously crippled the Roman peasants whom abandoned their home to campaign for years in distant lands, only to come back and find their farmland turned into a wilderness. Many peasants were thus forced to sell their land at a ridiculously low price, causing the emergence of an impoverished proletarian mass in Rome and an agricultural elite in control of vast swathes of countryside. This in turn disrupted army recruitment, which heavily relied on middle class peasants who were able to afford their own arms and armour. Two possible solutions could remove this problem: a redistribution of the land so that the peasantry remained wealthy and large enough to be able to afford their military equipment and serve in the army, or else allowing the proletarian masses to enter military service and make the army into a professional body. However, both options would threaten the position of the Roman Senate: a powerful peasantry could press calls for more political influence and a professional army would bind soldiers’ loyalty to their commander instead of the Senate. The senatorial elite thus stubbornly clung to the existing institutions which were undermining the republic they wanted to uphold. More importantly, the Senate’s attitude and increasingly shaky position, in addition to the growing internal tensions, created a perfect climate for overly ambitious commanders seeking to turn military prestige gained abroad into political power back home. Roman successes on the frontline nevertheless continued: Pergamum was turned into the province of Asia in 129 BC, Roman forces sacked the city of Numantia in Spain that same year, the Balearic Islands were conquered in 123 BC, southern Gaul became the new province of Gallia Narbonensis in 121 BC and the Berber kingdom of Numidia was dealt a defeat in the Jughurtine War (112 – 106 BC). The latter conflict provided Gaius Marius the opportunity to reform his army without senatorial approval, allowing proletarians to enlist and creating a force of professional soldiers who were loyal to him before the Senate. Marius’ legions proved their efficiency at the Battles of Aquae Sextiae in 102 BC and Vercellae in 101 BC, virtually annihilating the migratory invasions of the Germanic Cimbri and Teutones. Marius subsequently used his power and prestige to secure a land distribution for his victorious forces, thus setting a precedent: any successful commander with an army behind him could now manipulate the political theatre back in Rome. Marius was succeeded as Rome’s leading commander by Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who gained renown when Rome’s Italic allies – fed up with their unequal status – attempted to renounce their allegiance. Rome narrowly won the ensuing Social War (91 – 88 BC) and granted the Italic peoples full Roman citizenship. Sulla left for the east in 86 BC, where he drove back King Mithridates of Pontus, whom had sought to benefit from the Social War by invading Roman territories in Asia and Greece. Sulla marched on Rome itself in 82 BC, executed many of his political enemies in a bloody purge and passed reforms to strengthen the Senate before voluntarily stepping down in 79 BC. Sulla’s retirement and death one year later allowed his general Pompey to begin his own rise to prominence. Following his victory in the Sertorian War in 72 BC, Pompey eradicated piracy in the Mediterranean Sea in 67 BC and led a campaign against Rome’s remaining eastern enemies in 66 BC. Pompey drove Mithridates of Pontus to flight, annexed Pontic lands into the new province of Bithynia et Pontus and created the province of Cilicia in southern Asia Minor. He proceeded to destroy the crumbling Seleucid Empire and turned it into the new province of Syria in 64 BC, causing Armenia to surrender and become a vassal of Rome. Pompey’s legions then advanced south, took Jerusalem and turned the Hasmonean Kingdom in Judea into a Roman vassal as well. Upon his triumphant return to Rome in 61 BC, Pompey made the significant mistake of disbanding his army with the promise of a land distribution, which was refused by the Senate in an attempt to isolate him. Pompey then concluded a political alliance with the rich Marcus Licinius Crassus and a young, ambitious politician: Gaius Julius Caesar. The purpose of this political alliance – known in later times as the First Triumvirate – was to get Caesar elected as consul in 59 BC, so that he could arrange the land distribution for Pompey’s veterans. In return, Pompey would use his influence to make Caesar proconsul and thus give him the chance to levy his own legions and become a man of power in the Roman Republic. Crassus, the richest man in Rome, funded the election campaign and easily got Caesar elected as consul, after which Caesar secured Pompey’s land distribution. Everything went according to plan and Caesar was made proconsul of Gaul for five years, starting in 58 BC. In the following years, Caesar and his legions systematically conquered all of Gaul in a war which has been immortalised in the accounts of Caesar himself (‘Commentarii De Bello Gallico’). Despite fierce resistance and massive revolts led by the Gallic warlord Vercingetorix, the Gallic tribes proved unable to inflict a decisive defeat on the Romans and were all subdued or annihilated by 51 BC, leaving Caesar’s power and prestige at unprecedented heights. With Crassus having fallen at the Battle of Carrhae against the Parthians in 53 BC, Pompey was left to try and mediate between Caesar and the radicalised Roman proletariat on one side and the politically hard-pressed Senate on the other. However, Pompey had once been where Caesar was now – the champion of Rome – and ultimately chose to side with the Senate, realising his own greatness had become overshadowed by Caesar’s staggering military successes and popularity among the masses. When Caesar’s term as proconsul ended, the Senate demanded that he step down, disband his armies and return to Rome as a mere citizen. Though it was tradition for a Roman commander to do so, rendering Caesar theoretically immune from any senatorial prosecution, the existing political situation made such demands hard to meet. Caesar instead offered the Senate to extend his term as proconsul and leave him in command of two legions until he could be legally elected as consul again. When the Senate refused, Caesar responded by crossing the Rubicon – the northern border of Roman Italy which no Roman commander should cross with an army – and marched on Rome itself in 49 BC. Pompey and most of the senators fled to Dyrrhachium in Greece and assembled their forces while Caesar turned around and conducted a lightning campaign in Spain, defeating the legions loyal to Pompey at the Battle of Ilerda. Caesar crossed the Adriatic Sea in 48 BC, narrowly escaping defeat by Pompey at Dyrrhachium and retreating south. Pompey clumsily failed to press his advantage and his forces were in turn decisively defeated by Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus on 6 June 48 BC. Pompey fled to Egypt in hopes of being granted sanctuary by the young king Ptolemy XIII, who instead had him assassinated in an attempt at pleasing Caesar, who was in pursuit. Ptolemy XIII was driven from power in favour of his older sister Cleopatra VII, with whom Caesar had a brief romance and his only known son, Caesarion. In the spring and summer of 47 BC, another lightning campaign was launched northwards through Syria and Cappadocia into Pontus, securing Caesar’s hold on Rome’s eastern reaches and decisively defeating the forces of Pharnaces II of Pontus, who had attempted to profit from Rome’s internal strife. Caesar invaded Africa in 46 BC and cleared Pompeian forces from the region at the Battles of Ruspina and Thapsus before returning to Spain and defeating the last resistance at the Battle of Munda in 45 BC. Caesar subsequently began transforming the Roman government from a republican one meant for a city-state to an imperial one meant for an empire. Major reforms were required to achieve this, many of which would be opposed by Caesar’s political enemies. This was a problem because several of these people enjoyed significant political influence and popular support (cf. Cicero) and while none of them could really challenge Caesar individually and publicly, collectively and secretly they could be a serious threat. To render his enemies politically impotent, Caesar consolidated his popularity among the Roman masses by passing reforms beneficial to the proletariat and enlarging the Senate to ensure his supporters had the upper hand. He then manipulated the Senate into granting him a number of legislative powers, most prominently the office of dictator for ten years, soon changed to dictator perpetuus. Though widely welcomed by the masses, Caesar’s reforms and legislative powers dismayed his political opponents, whom assembled a conspiracy to murder him and ‘liberate’ Rome. The conspirators, of whom Brutus and Cassius are the most famous, were successful and Caesar was brutally stabbed to death on 15 March 44 BC. Caesar’s death left a power vacuum which plunged the Roman world into yet another civil war. In his testament, Caesar adopted as his sole heir his grandnephew Gaius Octavius, henceforth known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (Octavian, in English). Despite being only eighteen, Octavian quickly secured the support of Caesar’s legions and forced the Senate to grant him several legislative powers, including the consulship. In 43 BC, Octavian established a military dictatorship known as the Second Triumvirate with Caesar’s former generals Mark Antony and Marcus Lepidus. Caesar’s assassins had meanwhile fled to the eastern provinces, where they assembled forces of their own and subsequently moved into Greece. Octavian and Antony in turn invaded Greece in 42 BC and defeated them at the Battles of Philippi. Octavian, Antony and Lepidus then divided the Roman world between them: Octavian would rule the west, Antony the east and Lepidus the south with Italy as a joint-ruled territory. However, Octavian soon proved himself a brilliant politician and strategist by quickly consolidating his hold on both the western provinces and Italy, smashing the Sicilian Revolt of Sextus Pompey (son of) in 36 BC and ousting Lepidus from the Triumvirate that same year. Meanwhile, Antony consolidated his position in the east but made the fatal mistake of becoming the lover of Cleopatra VII. In 32 BC, Octavian manipulated the Senate into a declaration of war upon Cleopatra’s realm, correctly expecting Antony would come to her aid. The two sides battled at Actium on 2 September 31 BC, resulting in a crushing victory for Octavian, despite Antony and Cleopatra escaping back to Egypt. Octavian crossed into Asia the following year and marched through Asia Minor, Syria and Judea into Egypt, subjugating the eastern territories along the way. On 1 August 30 BC, the forces of Octavian entered Alexandria. Both Antony and Cleopatra perished by their own hand, leaving Octavian as the undisputed master of the Roman world. Octavian assumed the title of Augustus in January 27 BC and officially restored the Roman Republic, although in reality he reduced it to little more than a facade for a new imperial regime. Thus began the era of the Principate, named after the constitutional framework which made Augustus and his successors princeps (first citizen), commonly referred to as ‘emperor’, and which would last approximately two centuries. Augustus nevertheless refrained from giving himself absolute power vested in a single title, instead subtly spreading imperial authority throughout the republican constitution while simultaneously relying on pure prestige. Thus he avoided stomping any senatorial toes too hard, remembering what had happened to Julius Caesar. Augustus and his successors drew most of their power from two republican offices. The title of tribunicia potestes ensured the emperor political immunity, veto rights in the Senate and the right to call meetings in both the Senate and the concilium plebis (people’s assembly). This gave the emperor the opportunity to present himself as the guardian of the empire and the Roman people, a significant ideological boost to his prestige. Secondly, the emperor held imperium proconsulare. Imperium implied the emperor’s governorship of the so-called imperial provinces, which were typically border provinces, provinces prone to revolt and/or exceptionally rich provinces. These provinces obviously required a major military presence, thereby securing the emperor’s command of most of the Roman legions. The title was proconsulare because the emperor enjoyed imperium even without being a consul. The emperor furthermore interfered in the affairs of the (non-imperial) senatorial provinces on a regular basis and gave literally every person in the empire the theoretical right to request his personal judgement in court cases. Roman religion was also brought under the emperor’s wings by means of him becoming pontifex maximus (supreme priest), a position of major ideological importance. On top of all this, the Senate frequently granted the emperor additional rights which enhanced his power even more: supervision over coinage, the right to declare war or conclude peace treaties, the right to grant Roman citizenship, control over Roman colonisation across the Mediterranean, etc. The emperor was thus the supreme administrator, commander, priest and judge of the empire – a de facto absolute ruler, but without actually being named as such. It is worth noting that Augustus and most of his immediate successors worked hard to play along in the empire’s republican theatre, which gradually faded as the centuries passed. The most important questions nonetheless remained the same for a long time after Augustus’ death in AD 14. Could the emperor keep himself in the Senate’s good graces by preserving the republican mask? Or did he choose an open conflict with the Senate by ruling all too autocratically? Even a de facto absolute ruler required the support and acceptance of the empire’s elite class, the lack of which could prove to be a serious obstacle to any imperial policies. The relationship between the emperor and the Senate was therefore of significant importance in maintaining the political work of Augustus, particularly under his immediate successors. The first four of these were Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero – the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Tiberius was chosen by Augustus as successor on account of his impressive military service and proved to be a capable (if gloomy) ruler, continuing along the political lines of Augustus and implementing financial policies which left the imperial treasuries in decent shape at his death in AD 37 and Caligula’s accession. Despite having suffered a harsh youth full of intrigues and plotting, Caligula quickly gained the respect of the Senate, the army and the people, making a hopeful entry into the Principate. Yet continuous personal setbacks turned Caligula bitter and autocratic, not to say tyrannical, causing him to hurl his imperial power head-first into the senatorial elite and any dissenting groups (most notably the Jews). After Caligula’s assassination in AD 41, the position of emperor fell to his uncle Claudius who, despite a strained relationship with the Senate, managed to play the republican charade well enough to implement further administrative reforms and successfully invade the British Isles to establish the province of Britannia from AD 43 onward. But the Roman drive for expansion had been somewhat tempered after Augustus’ consolidating conquests in Spain, along the Danube and in the east. The Romans had practically turned the Mediterranean Sea into their own internal sea (Mare Internum or Mare Nostrum) and thus switched to territorial consolidation rather than expansion. However, the former was still often accomplished by the latter as multiple vassal states (Judea, Cappadocia, Mauretania, Thrace etc.) were gradually annexed as new Roman provinces. Actual wars of aggression nevertheless ceased to be a main item on the Roman agenda and indeed, the policies of consolidation and pacification paved the way for a long period of internal peace and stability during the first and second centuries AD – the Pax Romana. This should not be idealised, though. On the local level, violence was often one of the few stable elements in the lives of the common people across the empire. Especially among the lowest ranks of society, crimes such as murder and thievery were the order of the day but were typically either ignored by the Roman authorities or answered with brute force. Moreover, the Romans focused on safeguarding cities and places of major strategic or economic importance and often cared little about maintaining order in the vast countryside. Unpleasant encounters with brigands, deserters or marauders were therefore likely for those who travelled long distances without an armed escort. At the empire’s frontiers, the Roman legions regularly fought skirmishes with their local enemies, most notably the Germanic tribes across the Rhine-Danube frontier and the Parthians across the Euphrates. Despite all this, the big picture of the Roman world in the first and second centuries AD is indeed one of lasting stability which could not be discredited so easily. The real threat to the Pax Romana existed not so much in local violence, shady neighbourhoods or frontier skirmishes but rather in the highest ranks of the imperial court. The lack of both dynastic and elective succession mechanisms had been the Principate’s weakest point from the outset and would be the cause of major internal turmoil on several occasions. Claudius’ successor Nero succeeded in provoking both the Senate and the army to such an extent that several provincial governors rose up in open revolt. The chaos surrounding Nero’s flight from Rome and death by his own hand plunged the empire into its first major succession crisis. If the emperor lost the respect and loyalty of both the Senate and the army, he could not choose a successor, giving senators and soldiers a free hand to appoint the persons they considered suitable to be the new emperor. This being the exact situation upon Nero’s death in AD 68, the result was nothing short of a new civil war. To further add to the catastrophe, the civil war of AD 68/69 (the Year of Four Emperors) allowed for two major uprisings to get out of hand – the Batavian Revolt near the mouths of the Rhine and the First Jewish-Roman War in Judea. Both of these were ultimately crushed with significant difficulties, especially in Judea where Jewish religious-nationalist sentiments capitalised on existing political and economic unrest. Though the Romans achieved victory with the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 and the expulsion of the Jews from the city, Judea would remain a hotbed for revolts until deep into the second century AD. The fact that major uprisings arose at the first sign of trouble within the empire might cause one to wonder about the true nature of the Pax Romana. Was it truly the strong internal stability it is popularly known to be? Or was it little more than a forced peace, continuously threatened by socio-economic and political discontent among the many different peoples under the Roman yoke? Though a bit of both, the answer definitely leans towards the former hypothesis. While the Pax Romana lasted, unrest within the empire remained limited to a few hotbeds with a history of resisting foreign conquerors. Besides the obvious example of the Jewish people in Judea, whose anti-Roman sentiments largely stemmed from their unique messianic doctrines, large-scale resistance against the Romans was scarce. It is true that the incorporation and Romanisation of unique societies near the empire’s northern frontiers led to severe socio-economic problems and subsequent uprisings, most notably Boudica’s Rebellion in Britain (AD 60 – 61) and the aforementioned Batavian Revolt near the mouths of the Rhine. Nevertheless, it is safe to assume that the Pax Romana was strong enough to outlast a few pockets of rebellion and even a major succession crisis like the one of AD 68/69. The Year of the Four Emperors ultimately brought to power Vespasian, founder of the Flavian dynasty (AD 69 – 96) and architect of an intensified pacification policy throughout the empire. These policies were fruitful and strengthened the constitutional position of the emperor, not in the least owing to the fact that Vespasian’s sons and successors Titus and Domitian were as capable as their father. However, their skills did not prevent Titus and especially Domitian from bickering with the senatorial elite over the increasingly obvious monarchical powers of the emperor. In the case of the all too authoritarian Domitian, the conflict escalated again and despite his competent (if ruthless) statesmanship, Domitian was murdered in AD 96. A new civil war was prevented by diplomatic means: Nerva emerged as an acceptable emperor to both the Senate and the army, especially when he adopted the popular Trajan as his son and heir. Thus began the reign of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty (AD 96 – 192). Having succeeded Nerva in AD 98, Trajan once more steered the empire onto the path of aggressive expansion, leading the Roman legions across the Danube to crush the Dacians and establish the rich province of Dacia in AD 106. Subsequently, the Romans seized the initiative in the east, drove back the Parthians and advanced all the way to the Persian Gulf (Sinus Persicus). Trajan annexed Armenia in AD 114 and turned the conquered Parthian lands into the new provinces of Mesopotamia and Assyria in AD 116. Trajan died less than a year later on 9 August AD 117, his staggering military successes having brought the Roman Empire to its greatest extent ever…

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Romans sacking Carthage

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

The haka is a traditional declaration of war , not just a face ..it is a dance saying they are going to colonize or kill & pillage your people, she is making a face saying "I've come to to kill you "....Over a bill

Depends on the specifics of the bill, but there are certainly things a government can do that deserve the "this is such offensive bullshit that my own disapproval is insufficient, I must invoke the rituals of my warrior ancestors to convey the gravity of the situation. If this bill were a rival city-state I would be sacking its treasury and burning its crops right now. I am Cato the Elder and this bill is my Carthage" response. Politicians can come up with some very bad ideas!

#no idea why this is showing up in my inbox? were you trying to send this to someone else?#i don't believe i've said anything about political haka discourse one way or another#also i'm not at all sure hakas should always be read as literal threats of serious violence considering people do them before sports matche#rugby's rough but it's not *that* lethal

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Meeting of Dido and Aeneas

Artist: Sir Nathaniel Dance-Holland (English, 1735–1811)

Date: 1766

Medium: Oil paint on canvas

Collection: TATE Britain

Description

The picture depicts the meeting of the Trojan prince Aeneas and the Carthaginian queen, Dido, as described in Book I of Virgil's Aeneid. Following the sack of Troy, Aeneas and his followers are shipwrecked on the coast of North Africa, near the city of Carthage. There, Aeneas meets his mother, Venus, disguised as a huntress. She tells him the sad history of Dido, who was forced to flee her home in Tyre and to build a new citadel at Carthage. Venus envelops Aeneas and his compatriot Achates in a shroud of mist to enable them to penetrate Dido's citadel undetected. Upon entering the temple of Juno, Aeneas sees Dido seated upon her throne, welcoming a number of his fellow Trojans whom he had believed drowned in the recent shipwreck, and expressing her desire to see their 'king' Aeneas. At that moment the mist clears and Aeneas reveals his identity to Dido. This is the precise moment portrayed by Dance.

#mythological art#painting#oil on canvas#trojan prince#aeneas#virgil's aeneid#greek mythology#meeting#dido#venus#trojans#queen#soldiers#sir nathaniel dance holland#english painter#fine art#english art#18th century painting

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

So re your tags on the pope post...

Where's the menorah krindor?

So, starting at the very beginning.

70 CE: Titus sacks Jerusalem and loots the Second Temple. In his triumph (fancy war parade) he has the Menorah, as is recorded by Josephus Flavius in 71 CE and by the Arch of Titus' reliefs in 81 CE

The Menorah is displayed in the Tempulum Pacis in Rome, and 2nd century CE Rabbis claim to have seen it in Rome, as well as various other artifacts from the desroyed temple including the parochet and the choshen.

Now here's the thing. This is the last time historical texts mention the Menorah by name so everything below here needs to be taken with an increasing pile of salt

410 CE: The Visigoths sack Rome. Procipius of Ceasarea (500-560), a Byzantine Historian, writes that the Visigoths take "treasures of Solomon the King of the Hebrews." If this includes the Menorah, the trail goes cold. So that's it right? The Menorah got taken to a secondary location and was lost forever, right?

Wrong, because that's not the only time Procipius mentions Jewish Temple loot.

425 CE: The Vandals sack Rome again, to the point where the word vandalize comes from it. Procipius notes that their leader, Geiseric, takes "a huge amount of imperial treasure" with him to Carthage, which was at that time the Vandal capital.

Trust me this is relevant

534 CE: The Byzantine Emperor Justinian sacks Carthage, and they hold a triumph in Constantinople. Among the paraded items are "treasures of the Jews, which Titus, the son of Vespasian, together with certain others, had brought to Rome after the capture of Jerusalem”

That these "treasures of the Jews" include the Menorah is not a new theory, as is indicated in the 19th century painting Geiseric sacking Rome by Karl Bryullov

(Note the Menorah)

So it's in Istanbul right?

Wrong, because our boy Procipius isn't done yet: according to him, Justinian sent the "treasures of the Jews" to Christian sanctuaries in Jerusalem, since he heard that they were cursed that any city save Jerusalem that held them was doomed to be sacked.

This is the last time the "treasures of the Jews" are mentioned in historical texts.

So for our next step, lets look at major churches in Jerusalem in the 6th century, and officially enter the cork-board and string section of this rant post.

As well as the extant Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Hagia Sion Basilica, and the Church of the Holy Apostles, Justinian built a church himself in the city, called the Nea, in 534 CE, just nine years after sacking Carthage. It would not be unreasonable that he'd send the Menorah to his own church, so we can theorize that it's in the Nea for the remainder of the 6th century (there are, of course, problems with relying on one historian's account of these things, but this is for fun, not a published article)

So that's it? It's in one of the churches of Jerusalem?

...

So in 614 CE Jerusalem gets sacked by the Sasanian/Persian Empire, who according to historical records destroy all the churches.

Now here's the thing. Recent archaeological evidence gives rise to the possibility that our Byzantine historical sources are trying to stir up outrage against the Sasanians: While mass graves dating to around 614 CE were found, the churches and Christian residential neighborhoods were barely, if at all, damaged, and the Nea itself was very possibly completely undamaged. This is, however, a recent theory, and the academics are still hashing it out.

So it may be in one of the churches of Jerusalem?

Tragically, even if the 614 siege didn't get the churches, in 1009 the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah destroyed all churches, synagogues, and many religious artifacts of both Christians and Jews in Jerusalem. So if by some miracle the Menorah had survived until this point, if it was in Jerusalem it was most likely destroyed.

But that's disappointing, and what's a good conspiracy theory without going a step or two beyond what is reasonable?

Apparently, while the churches, synagogues and most of the artifacts were destroyed, at least in the case of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, objects that could be carried away were looted, rather than destroyed. And if we know anything about the Menorah at this point, that thing is certainly able to be carried away by people.

If the Menorah was looted rather than destroyed, it's not unreasonable that it would have made it's way to the Fatimid capital of Cairo. However, as the historical record dried up some 500 years beforehand, beyond this point it's unreasonable to attempt to track the Menorah.

So that's it. If the Menorah wasn't destroyed it most likely made its way to Egypt and was lost or destroyed there.

Is what I'd say if I wasn't so far down this rabbit hole I was beyond reason. Because as we all know there's one place that has all the significant treasures of Cairo and a penchant for looting:

The British Museum

#i cant in good conscience call this either archaeology or history#anyway this is very unhinged but was fun to research#pseudoarchaeology#pseudohistory#jewish stuff

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you feel remorse for your participation in the 146 BC sack of Carthage?

Yes 😔

(Ask me anything and I can only respond yes or no!)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Randomly while mowing the lawn this evening, I suddenly had the opening scene for my Hosie gladiator/Roman Republic AU pop into my head, fully formed (like Athena from Zeus!)—as well as some of the backstory.

I have no idea what the proximate cause was, but I’m pretty sure chatting with @evilpenguinrika last night about our shared Classics background got something bubbling in my subconscious.

(It, uh, took me waaaay to long to write out said scene tonight…796 words in about 2 hours…I should have stuck to notes/sketches instead of veering off into researching and actually writing 😳)

“Carthago delenda est! Carthago delenda est! Carthago delenda est!”

A crowd one-hundred fifty thousand strong was chanting that vile phrase over and over as Hope Mikaelson, former Carthaginian princess and current Roman captive, was led into the Circus Maximus in chains. Daughter of Prince Klaus Mikaelson, one of Carthage’s ruling oligarchs, she had been captured by Scipio’s forces in the Roman general’s destruction of her homeland. Dressed in sandals and a silk stola befitting of her former station, the princess’s fiery auburn hair was woven in a long braid, and her head was topped with a wreath of laurel.

The chanting finally quieted as a Roman official began to speak. The man, whom Princess Hope had come to know as Alaricus Saltzmanus—a man who had declared himself a sworn enemy of her father and who was most likely responsible for her current situation—welcomed the assembled Romans to the climax of the day’s festivities—festivities that had seen dozens of her countrymen slaughtered for entertainment of the masses, the famed track of the Circus Maximus stained red with their blood.

As Saltzmanus introduced the day’s final contest, the chants of “Carthago delenda est!” began once more. Carthage had already been destroyed by these monsters, burned, sacked, looted, and its fields salted so that the grand civilization may never be reborn, but Hope knew that the chants now were calling for the destruction of every last vestige of Punic glory; to the Romans, Carthage could not be considered destroyed while a single Carthaginian still lived, and at this hour, for Carthage to be destroyed, Princess Hope Mikaelson must be slaughtered.

The crowd cheered as the Roman champion, a man known only as Ferus—wild, savage—entered the Circus, sword and shield in hand. The assembled people of Rome—patricians and plebeians, citizens and non-citizens alike—began chanting the man’s name, “Fer-us, Fer-us, Fer-us!” Bowing to the adoring crowds, the bear-like man reveled in their devotion. His toned chest bore the scars of his victories—undefeated in more than 100 fights.

One of the men holding Hope drew his sword and deftly sliced the shoulders of her stola, causing the fine garment to tumble to bloody ground around her feet. Rather than the traditional underclothes, she had been dressed in a skirt fashioned from strips of leather, the lower ends of each strip triangular-shaped. The former princess had also been fitted with a small leather breastplate, which provided some measure of modesty while still emphasizing her ample assets. With a thumbs up and a thumbs down, the man made a show of asking the crowd whether the auburn-haired captive should retain that bit of dignity or be made to fight bare-chested as the men. Despite the overwhelming cheers in favor of the Carthaginian being stripped of the garment, the man made no move to remove it. Hope breathed a sigh of relief; thank the Gods for small mercies. Still, the crowds had spoken, so the last daughter of Carthage knew it was in play.

The man then kicked Hope’s knees from behind, forcing her to kneel before those who had vanquished her and her homeland. She struggled to regain her stance, but the attending men (and their ropes) managed to keep her on her knees. The man finally yanked the laurel crown off her head, completing the show of stripping the Carthaginian of all symbols of her (former) status. The crowd cheered the man’s actions humbling the former princess before once again breaking into chants of “Carthago delenda est!”

Saltzmanus finished his speeches, propitiating the Gods and currying favor with the crowds, his every word calculated to advance his political career, and reminded the assembled masses that this was a battle to the death…“for the Glory of Rome.”

The crowd began chanting “for the glory of Rome!” repeatedly, and the men guarding Hope knew this was their cue to release their captive. Two men removed the manacles from her wrists and ankles, quickly scurrying away upon completion of their task. The remaining men had formed a circle around the princess-cum-gladiator, their spears keeping her at bay for these actions. In an instant, the men pivoted and reformed their circle, their bodies and spears now facing outward in defense of themselves, and they made a swift and practiced retreat to the safety of arena gates. Hope Mikaelson may have been a princess, but she was every bit her father’s daughter, a danger to anyone within reach….

As Saltzmanus tossed a sword and shield to the ground in front of him, the crowd again switched to chanting for Hope’s death, their thunderous cries echoing across the Circus Maximus. “Carthago delenda est! Carthago delenda est! Carthago delenda est!”

#status#hosie#Roman Republic Hosie#this is the way my mind works#My high school Latin teacher would be so proud 🙄#excerpt

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

would love some director's commentary on basically any part of Carthaginians you'd like to talk about, but my favourite part was the second last chapter/the siege itself and I'd love to know how you worked out what trajectory to take the characters on through all the historical records. would also love to know more of your thoughts on Yusuf and Nico's backstory and families, if you have thoughts!

Thanks! <3 All right, Carthaginians, let's go.

The siege - or, more specifically, the final Fall of Carthage - was definitely what came first in terms of planning out this fic. When I first had the idea of writing Joe & Nicky's backstory further back in history, the Punic Wars were a logical setting to start with due to simple geography - Carthage being in modern day Tunisia, and Rome being, well, Rome.

So as with any vague idea, I started with a wikipedia deep dive, kind of assuming that I'd stick to the general canon template of them killing each other for the first time in battle and then becoming lovers afterward. But I immediately stumbled across the fact that Carthage's final stand, after the city had surrendered, consisted of about 900 Roman defectors in the Temple of Eshmoun setting the temple on fire around them rather than allowing Rome to execute them. Which. So that was obviously going to Nicky's arc. Which meant he would have to defect to Carthage much earlier on. Which meant I could give him and Joe a much richer relationship build over the course of the war itself. At that point, there was no question that their first deaths would be more of a suicide pact due to having no other options. I thought about having them, IDK, leap off the temple roof together or something, but nah, it felt much stronger to have them kill each other directly, as per canon, but with a complete subversion of what got them to that point.

I wrote chronologically and posted as I went, but it definitely helped going in to know exactly where they had to end up. For example, I deliberately seeded their exact dialogue together in the temple at the end of the siege as lines in their very first idle political debate in Rome in chapter one, so that Nicky could do a complete 180 on his initial stance in the debate by the end.

Embarrassingly, while that was all planned out from the beginning, I was WELL into the middle of the fic before realizing that, uh, Eshmoun is literally the god of healing. I mean, I knew that from the start, but I literally had my own personal OH DUH moment that they would be dying and resurrecting for the first time in the temple of the god of healing, and would OF COURSE think that Eshmoun himself had literally healed them due to their sacrifice on his own figurative altar. So that was an incredibly lucky piece of historical fact to tie into the immortality narrative.

In terms of their family backstories there - I think Yusuf's is about as fleshed out in the fic as it's going to be, it's all his POV and I included all the family info/dynamics I'd thought about. Nicky's didn't get as much detail in the fic, since we're never in his head and he didn't talk about it as much, but his family was the rough equivalent of landed gentry back in Genua - relatively high status for his own tribe, but doesn't mean much to the Roman Republic as a whole. They were granted Roman citizenship when the Genuates allied with Rome, and Nicky received a formal education, but their family wealth took a huge hit during the second Punic War (when Carthage sacked the city) and never really recovered, which is why Nicky left to join the Roman army and make his own fortune. I think he's not the oldest of his siblings - not the one expected to inherit and carry on the family legacy - but probably the second son, with several younger siblings in the mix as well. He has a strained relationship with his father and a better one with his mother, who I imagine died before he left home. He misses his younger sibs, who he helped raise, but never returns to Genua in their lifetimes.

So...yeah! I spent all year with the world of this fic in my head, it's been hard to let go of it. Thank you for asking!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A model of the planned Welthauptstadt Germania

“We work beneath the earth and above it, under a roof and in the rain, with the spade, the pickaxe and the crowbar. We carry huge sacks of cement, lay bricks, put down rails, spread gravel, trample the earth . . . We are laying the foundation for some new, monstrous civilization. Only now do I realize what price was paid for building the ancient civilizations. The Egyptian pyramids, the temples, and Greek statues - what a hideous crime they were! How much blood must have poured on to the Roman roads, the bulwarks, and the city walls. Antiquity - the tremendous concentration camp where the slave was branded on the forehead by his master, and crucified for trying to escape! Antiquity - the conspiracy of free men against slaves!

You know how much I used to like Plato. Today I realize he lied. For the things of this world are not a reflection of the ideal, but a product of human sweat, blood and hard labour. It is we who built the pyramids, hewed the marble for the temples and the rocks for the imperial roads, we who pulled the oars in the galleys and dragged wooden ploughs, while they wrote dialogues and dramas, rationalized their intrigues by appeals in the name of the Fatherland, made wars over boundaries and democracies. We were filthy and died real deaths. They were 'aesthetic' and carried on subtle debates.

There can be no beauty if it is paid for by human injustice, nor truth that passes over injustice in silence, nor moral virtue that condones it.

What does ancient history say about us? It knows the crafty slave from Terence and Plautus, it knows the people's tribunes, the brothers Gracchi, and the name of one slave - Spartacus.

They are the ones who have made history, yet the murderer - Scipio - the lawmakers - Cicero or Demosthenes - are the men remembered today. We rave over the extermination of the Etruscans, the destruction of Carthage, over treason, deceit, plunder. Roman law! Yes, today too there is a law!

If the Germans win the war, what will the world know about us? They will erect huge buildings, highways, factories, soaring monuments. Our hands will be placed under every brick, and our backs will carry the steel rails and the slabs of concrete. They will kill off our families, our sick, our aged. They will murder our children.

And we shall be forgotten, drowned out by the voices of the poets, the jurists, the philosophers, the priests. They will produce their own beauty, virtue and truth. They will produce religion.” (p. 111, 112)

#borowski#tadeusz borowski#this way for the gas ladies and gentlemen#ladies and gentlemen to the gas chambers#auschwitz#germania#naziism#antisemitism#wwii#world war ii#slave labor#slave labour

7 notes

·

View notes