#the dissent itself is enough of a crime

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This is exactly why I "argue" with gender identity ideologues in my ask box in the hopes that I might be an example to someone (be they radfem, TRA, fence sitter, uncertain, or neither) of what radfems actually believe and that we are human beings not evil bogeymen. we are not reactionaries, not even in the slightest - we are feminist women (often SSA and gnc women) who recognize the indisputable existence of sex-based oppression and very genuinely believe with our whole hearts in fighting for female liberation. we don't hate people who identify as trans, we really truly actually just do not believe in the idea that people have an innate internal "gender identity," because the gender construct is a patriarchal creation that doesn't exist in nature.

She actively went to great effort to show followers of GII that we don't want them to suffer and support their rights and freedom as human beings. She was SUCCESSFUL in getting this across to at least one person, which we all know how rare that is. And STILL she got kicked off tiktok. Idk what her other posts were like, but I'd be very surprised if they remotely warranted that. I just wish I was at least a tiny bit surprised she still got banned for simply not worshiping gender identity and saying that doesn't make her hate those who do.

Wonderfully put

#the only upside to 2 is that it's a really excellent example of what we are always saying#about the extent of silencing & de-/no-platforming & censoring aimed at women who dare acknowledge female oppression#and about how bizarre it is that the supposedly most oppressed people in the world#who supposedly are like a teeeeny tiny portion of the population#have such strong influence and so much power as to make that censorship happen#have convinced so many people including many legislators CEOs etc#that anyone who dissents must be swiftly and thoroughly silenced#and often punished with real-world consequences like being doxxed or fired or SWATted or stalked or harassed irl#even if that dissent was done with the highest degree of empathy understanding kindness and compassion#the dissent itself is enough of a crime#sorry for the ramble#very very sleep deprived tbqh#GII#gender identity ideology#gender ideology#deplatforming#woke misogyny#trans misogyny#silencing women#censorship#what we believe#radical feminism

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

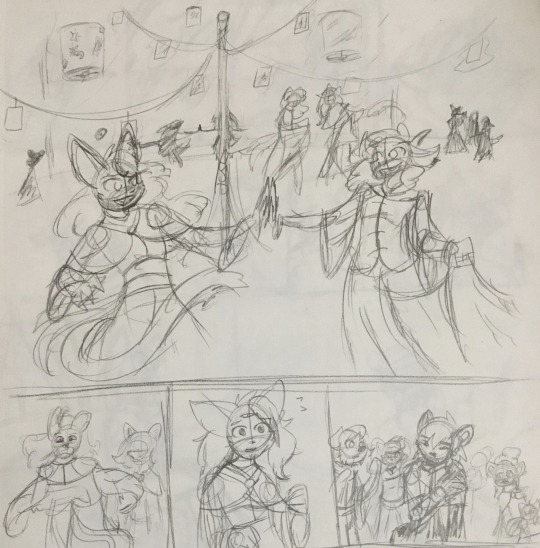

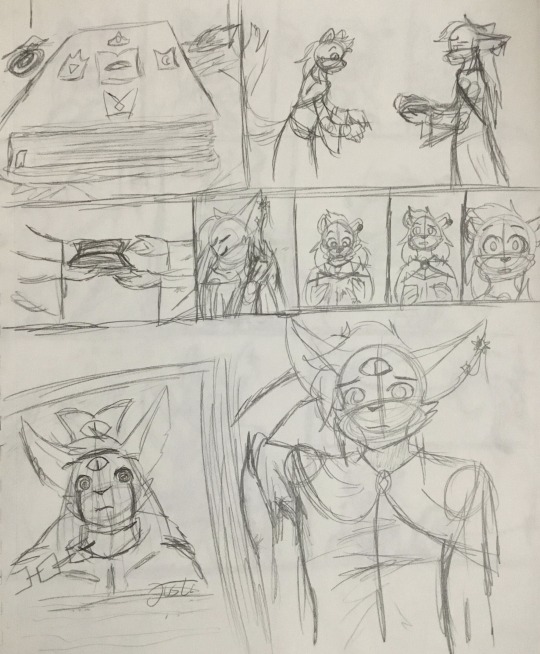

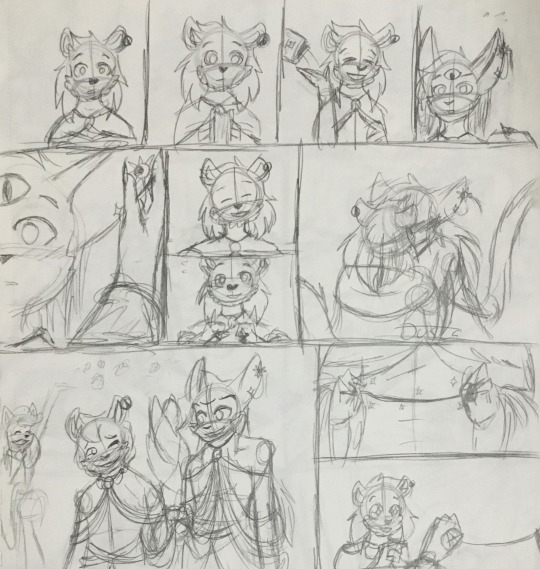

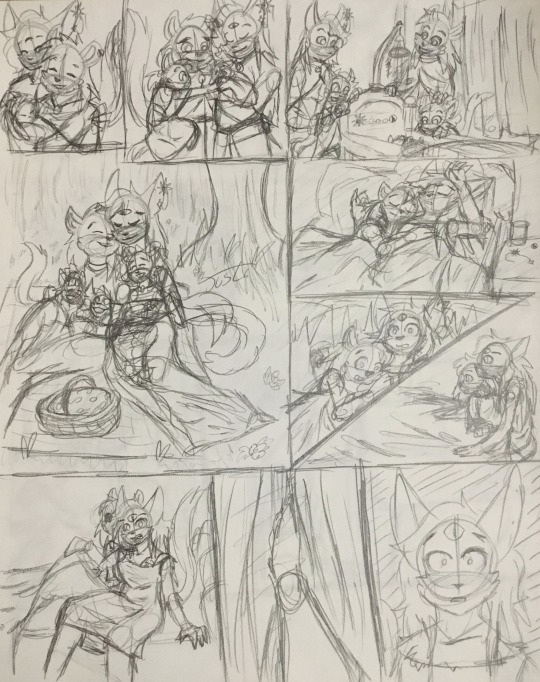

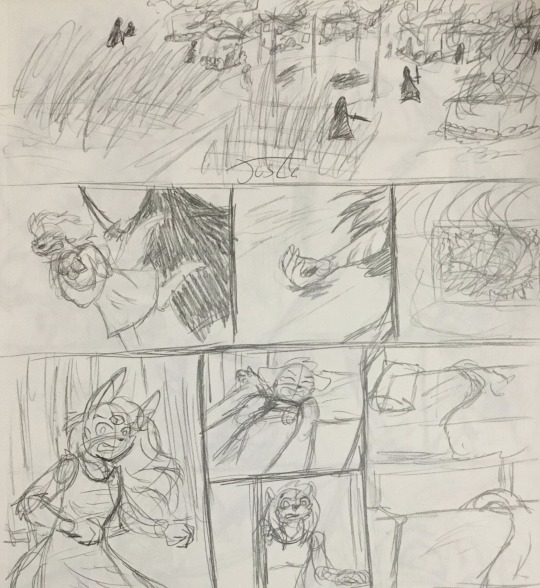

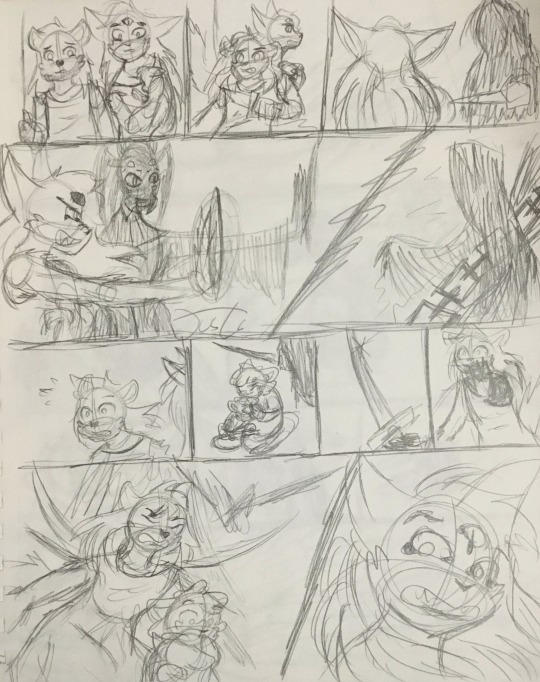

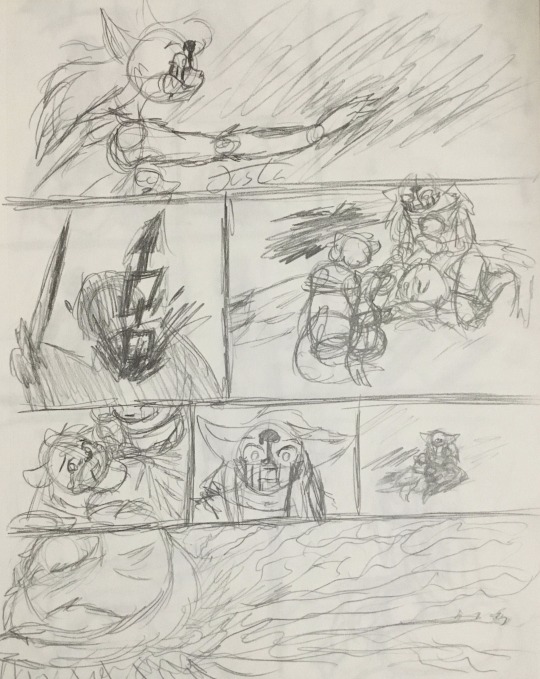

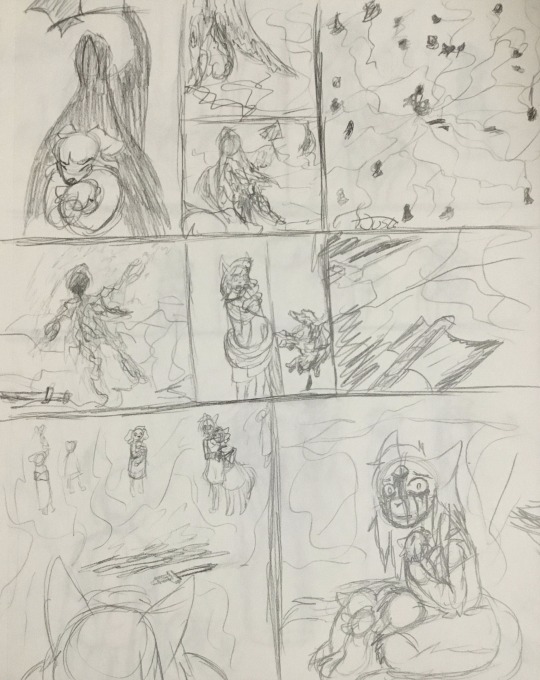

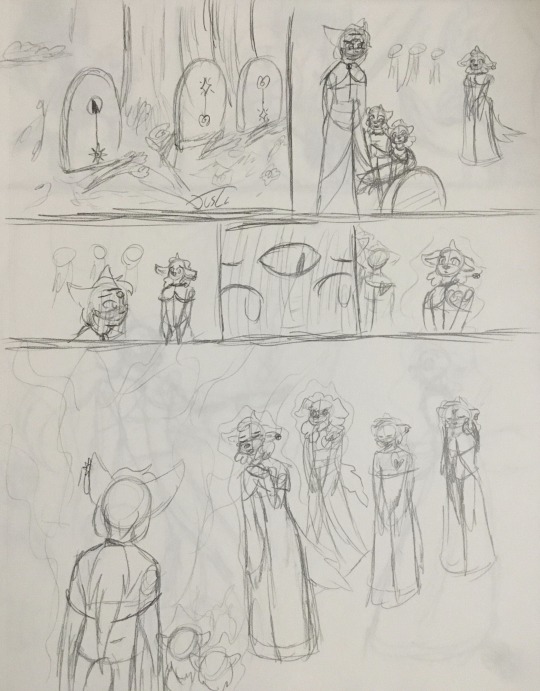

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 [END]

The love story of a mortal and an immortal is always doomed to end in tragedy, but even just a little more time would have meant everything...

And that's Narinder's prologue for this au sketched out. Also yes that's a cat he's just got small rounded ears instead of long sharp ears <3

Explanation of the story under the cut (this time with some dialogue!)

During a festival, someone runs up to Narinder saying a stranger has come to the village, and he's wounded. Narinder recognizes the cloak he wears as being that of a Darkwood cultist, so Narinder takes the injured cat to his home to take care of him, and also to confront him without anyone else there. Narinder finds that he's brought a book of the Old Faith with him.

The stranger wakes up and notices Narinder immediately. Narinder confronts him about the book he's brought with him, and the fact that he's a follower of the Old Faith. The cat explains that he actually ran away, seeing no point in killing and fighting and living and dying for a god who is already dead (awkward considering Leshy is very much alive again and loyal to the Lamb by this time, but neither of them know this), but that his old family outed him as a dissenter and he was chased/attacked on his way out. Narinder accepts this explanation but gives a stern warning to the newcomer;

"These are godless lands and we bow to no one. There will be no talk of the Old or New Faiths, no talks of gods, no preaching. And this book stays in this room so long as you're in this village, got it?"

Narinder drops the book into the side table, then tells the newcomer that he's welcome to stay as long as he wants/needs so long as he doesn't bring talk of gods into the village itself. The newcomer accepts this easily enough- he ran away from the Old Faith, after all, he only brought the book by happenstance.

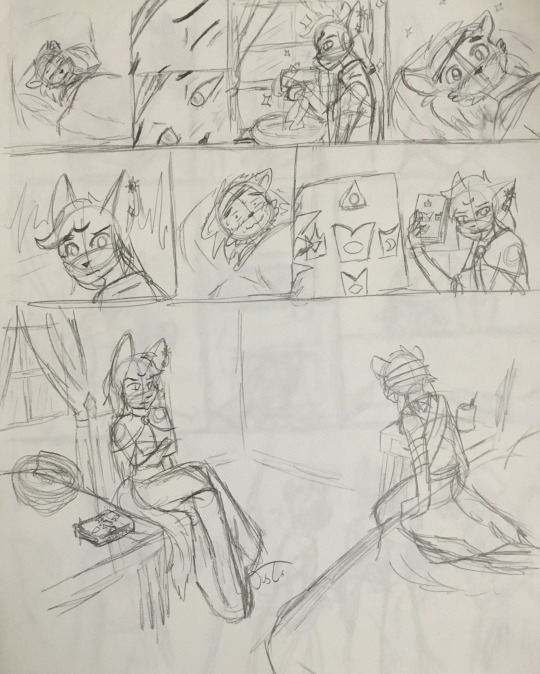

Narinder gives the stranger clothes and shows him around the village, introducing him to people (and translating for both sides, as the newcomer does not speak the godless language and the godless don't speak the language of the Faithful). Time passes, and the newcomer stays even when he's healed, slotting himself into the daily routine of the village. Narinder begins slowly teaching him about their culture, once it becomes clear that he doesn't intend to leave; he shows him how to take care of the feral beasts, teaches him how to make paper lanterns for their lantern festival, teaches him their dances, and eventually even gives him an ear piercing, the same as anyone who comes of age inside or is accepted into the village from outside gets. It's essentially the moment that he becomes an accepted part of the village, an acknowledgement that he is one of them now; no longer an outsider, no longer a cultist but one of the godless.

One day, Narinder's friend (as by this time he cannot really be called a newcomer and ofc I don't have a name for him...) confesses to Narinder, and Narinder realizes all at once that if he wants to pursue this... thing he and his friend have going on, he needs to tell him the truth.

So Narinder does it in the most dramatic sad wet cat way he can; he brings out the book that's sat gathering dust inside the drawer for well over a year now and finds the entry on the Red Crown and the One Who Waits. The "Friend" is confused at first before looking at Narinder and realizing that Narinder is the One Who Waits- a fallen god of the Old Faith, and arguably the most powerful of all of the Old gods.

And... he doesn't care. Narinder is Narinder, not the Bishop of Death after all. He just tosses the book- something once sacred in the cult he was born into- aside and expresses that he doesn't care; it doesn't matter who Narinder used to be, or the crimes he committed in the past, because he loves the person Narinder is now. Narinder accepts his confession with this acceptance.

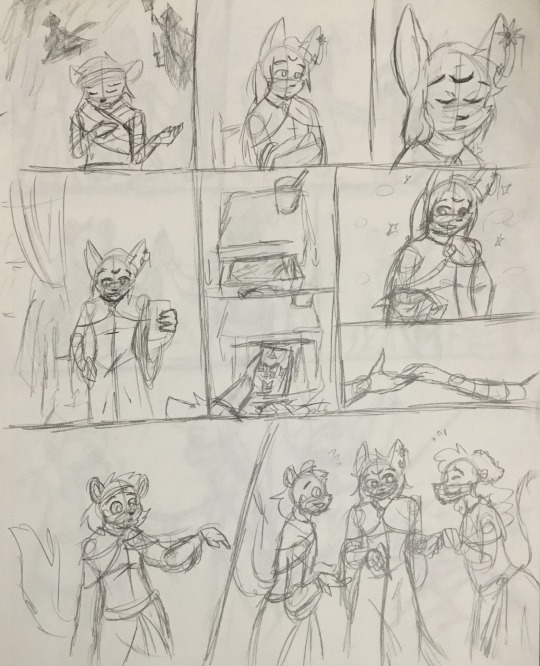

Time passes. They marry, with Narinder presenting a marriage charm to him, much to his delight. They start a family- first child they name Ari, the second Elloi, and the third Minuit, all a few years apart in age.

And for just a little bit- everything is perfect. Even though Narinder's immortality hangs over him like a shroud, he takes every day a moment at a time, and he's happier than he's been in a long, long time.

Then one night they're woken by the sound of crashing and screams. They're a little freaked out, because it's been so long for both of them but they recognize that sound- they've just both been on the other side of it. Opening the curtains confirms Narinder's fears; there's a raid happening on their village, the same way gods and their cults once crusaded against each other and razed entire settlements in a bid for power. Buildings are burning, people are running and screaming and crying, some people are dead, and robe-clad people very reminiscent of cultists and heretics bear weapons and chase people down, uncaring of whether they're old, young or children.

Narinder scoops up the baby- only a few months old and crying in fear- while his husband rushes to grab their older kits, only to find their beds empty. Panic sets in, and rather than running into the forest (to hide and hopefully avoid the attackers) like they initially planned, they rush into the village to look for their daughters. Narinder comes face to face with a cultist, and has a moment where he remembers Shamura teaching him offensive magic- before they even had the crowns, back when it was just them and the magic they were born with. Chains, which he hasn't seen or felt in nearly a hundred years at this point, shoot up at his command, spearing through and instantly killing his would-be attacker.

His husband, somewhere along the way, loses the dagger he'd always carried while fighting cultists. He spots their daughters on the ground, holding onto each other and crying in fear while a cultist raises a sword. Instinct kicks in and he rushes to them, throwing himself between his kits and their attacker- too afraid that attacking them would still end up with his kits hit by the sword.

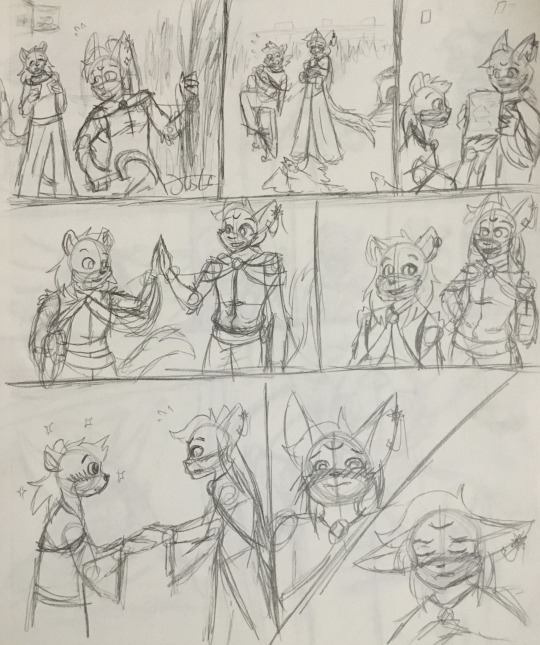

Narinder hears his kits scream and turns in time to see his husband collapse, mortally wounded (he did take a sword for someone who was in front of him, that shit went DEEP), and in a moment of horror reaches out with his magic, spearing their attacker with the chain before they can turn their attention to the kits again. He runs over, dropping down by his husband's side, and pulls him into his lap. His husband manages to smile at him, saying some final words before dying in his family's arms.

Grief hits Narinder hard, and his magic lashes out; withering lines of decay snake through the village, the grass crumbling and the earth itself cracking in the wake of his magic. It targets the cultists while avoiding the villagers, and the cultists begin rotting and turning to dust right on the spot, whether they are bodies on the ground or living beings in the middle of swinging an axe. All at once the tables are turned, their attackers reduced to ash and blood on the ground and in the wind, and careful to avoid the lines, slowly the bravest of the villagers follow the decaying earth to its epicenter; Narinder and his once-again-broken family.

None of the villagers fear Narinder, even like this. All they feel is grief; grief for what has happened to their village, grief for their neighbors and loved ones, grief for the families that have been lost, grief for what the future holds for them. They share in his grief, but they realize something in that moment; Narinder can actually do something with his grief.

A few days pass and the dead have been buried. Narinder and his older kits pay respects to his husband's grave, and some villagers approach to give their condolences and also ask; "What now?"

He looks back, listening to their worries. With his third eye open and with him reaching out to them with his own magic, he notices for the first time that some of them have a certain... energy about them. Some have more than others; some's energy is lashing out, while others' are gentle, and some are... reaching back to him. He realizes that this energy is magic- the same thing Shamura saw in him and the others, thousands of years ago, when they decided to train them.

He remembers Shamura telling him something now, when he asked why they taught him and the others to fight and use magic when they clearly wanted to keep them all safe; "Sometimes the best way to protect those you love is teach them to protect themselves."

He takes this lesson to heart now; the village must learn to fight, so that they will never be made victims again.

"We rebuild. We learn to wield swords." He summons a flame into his hand, holding it out for the villagers who have turned to him in this time of hardship to see. "And those of you who are capable of magic- I will teach it to you.

"What has happened here will not happen again."

#cult of the lamb#cotl au#justa arts#narinder#God in a Godless Land AU#sketch#some canon/oc but like temporary#cw character death#cw violence#I don't know how to express to you how freaking bad I am at names#you would think I'd have a name for the dude who married Narinder but NOPE#Ari and Elloi definitely won't have any issues or self blame about this#'if we hadn't snuck out to see the lanterns then dad would still be alive' haha yeah-#I might work on digitizing this as I do Lamb's prologue sketches but I want to actually make it Look Good and maybe do it in color#so it might be a while before you see this fully fleshed out#just know I am working on it bc I'm lowkey obsessed with this au for some reason#do me a favor and don't notice how I forgot Narinder's veil in the last page <3

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ian Millhiser at Vox:

The six Republican justices handed down a decision on Friday that effectively legalizes civilian ownership of automatic weapons. All three of the Court’s Democrats dissented. The Court’s decision in Garland v. Cargill involves bump stocks, devices that allow ordinary semiautomatic weapons that can legally be owned by civilians to automatically fire, much like a machine gun designed for that purpose. Bump stocks cause a semiautomatic gun’s trigger to buck against the shooter’s finger, repeatedly “bumping” the trigger and making the gun rapidly fire. A semiautomatic weapon refers to a gun that loads a bullet into the chamber or otherwise prepares itself to fire again after discharging a bullet, but that will not fire a second bullet until the shooter pulls the trigger a second time. An automatic weapon, by contrast, will fire a continuous stream of bullets.

As Justice Sonia Sotomayor notes in her dissent, the Trump administration decided to ban bump stocks after a shooter opened fire on a music festival in Las Vegas in 2017, killing 58 people and wounding over 500 in a matter of minutes. The shooter used bump stocks to kill so many people so quickly. A 1986 law makes it a crime to own a “machinegun,” and the Trump administration determined that this law is broad enough to encompass bump stocks. That law defines a “machinegun” to include “any weapon which shoots, is designed to shoot, or can be readily restored to shoot, automatically more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger.” This law is, in fairness, rather ambiguous. And lower courts divided on whether it could be read as the Trump administration read it.

Some courts concluded that the phrase “a single function of the trigger” should be read to mean, as one of those courts put it, “a single pull of the trigger from the perspective of the shooter.” Thus, a semiautomatic weapon equipped with a bump stock counts as a machine gun because “the shooter engages in a single pull of the trigger with her trigger finger, and that action, via the operation of the bump stock, yields a continuous stream of fire as long she keeps her finger stationary and does not release it.” Writing for the Court’s Democratic minority, Sotomayor adopts this reading of the statute. In her words, “a machinegun does not fire itself. The important question under the statute is how a person can fire it.”

The other plausible reading of the statute focuses on whether the trigger itself moves back and forth each time a bullet is fired. Writing for the Court’s Republicans, Justice Clarence Thomas adopts this view, arguing that “all that a bump stock does is accelerate the rate of fire by causing these distinct ‘function[s]’ of the trigger to occur in rapid succession.” Both of these outcomes can also be supported by competing rules guiding how statutes should be interpreted. [...] And so the six Republicans — members of a political party that typically supports gun rights, despite the Trump administration’s actions on bump stocks — picked the outcome that aligns with their political party’s pro-gun stance. The justices who belong to the Democratic Party, meanwhile, picked the outcome that aligns with their party’s position on guns.

The right-wing judicial activist 6-3 majority on SCOTUS ruled in favor of legalizing machine guns in the Garland v. Cargill case by ruling that bump stock bans are unconstitutional.

See Also:

HuffPost: Supreme Court Overturns Ban On Gun-Enhancing Bump Stock Devices

#SCOTUS#Garland v. Cargill#Guns#Bump Stocks#Bump Stock Ban#Gun Rights#Mandalay Bay Shooting#Gun Safety

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

AI is often considered a threat to democracies and a boon to dictators. In 2025 it is likely that algorithms will continue to undermine the democratic conversation by spreading outrage, fake news, and conspiracy theories. In 2025 algorithms will also continue to expedite the creation of total surveillance regimes, in which the entire population is watched 24 hours a day.

Most importantly, AI facilitates the concentration of all information and power in one hub. In the 20th century, distributed information networks like the USA functioned better than centralized information networks like the USSR, because the human apparatchiks at the center just couldn’t analyze all the information efficiently. Replacing apparatchiks with AIs might make Soviet-style centralized networks superior.

Nevertheless, AI is not all good news for dictators. First, there is the notorious problem of control. Dictatorial control is founded on terror, but algorithms cannot be terrorized. In Russia, the invasion of Ukraine is defined officially as a “special military operation,” and referring to it as a “war” is a crime punishable by up to three years imprisonment. If a chatbot on the Russian internet calls it a “war” or mentions the war crimes committed by Russian troops, how could the regime punish that chatbot? The government could block it and seek to punish its human creators, but this is much more difficult than disciplining human users. Moreover, authorized bots might develop dissenting views by themselves, simply by spotting patterns in the Russian information sphere. That’s the alignment problem, Russian-style. Russia’s human engineers can do their best to create AIs that are totally aligned with the regime, but given the ability of AI to learn and change by itself, how can the engineers ensure that an AI that got the regime’s seal of approval in 2024 doesn’t venture into illicit territory in 2025?

The Russian Constitution makes grandiose promises that “everyone shall be guaranteed freedom of thought and speech” (Article 29.1) and “censorship shall be prohibited” (29.5). Hardly any Russian citizen is naive enough to take these promises seriously. But bots don’t understand doublespeak. A chatbot instructed to adhere to Russian law and values might read that constitution, conclude that freedom of speech is a core Russian value, and criticize the Putin regime for violating that value. How might Russian engineers explain to the chatbot that though the constitution guarantees freedom of speech, the chatbot shouldn’t actually believe the constitution nor should it ever mention the gap between theory and reality?

In the long term, authoritarian regimes are likely to face an even bigger danger: instead of criticizing them, AIs might gain control of them. Throughout history, the biggest threat to autocrats usually came from their own subordinates. No Roman emperor or Soviet premier was toppled by a democratic revolution, but they were always in danger of being overthrown or turned into puppets by their own subordinates. A dictator that grants AIs too much authority in 2025 might become their puppet down the road.

Dictatorships are far more vulnerable than democracies to such algorithmic takeover. It would be difficult for even a super-Machiavellian AI to amass power in a decentralized democratic system like the United States. Even if the AI learns to manipulate the US president, it might face opposition from Congress, the Supreme Court, state governors, the media, major corporations, and sundry NGOs. How would the algorithm, for example, deal with a Senate filibuster? Seizing power in a highly centralized system is much easier. To hack an authoritarian network, the AI needs to manipulate just a single paranoid individual.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On a daily basis, much of the world stands silent while Zionists, Israeli butchers, murder Palestinian civilians, with a particular focus on children and youth. The over 2 million Palestinians living in Gaza effectively live in an open air prison without any rights, freedom of movement, or control of their lives, and are denied self-determination. Crying “enough is enough,” A coalition of Palestinian resistance groups, courageously carried out a well coordinated offensive against their oppressors. In response, Israel has declared war against the Palestinian people, labeling them terrorists and claiming the attack to be unprovoked. But the fact of the matter is, Israel declared war on Palestine in 1948 when over 750,000 Palestanians were forcibly expelled from their ancestral lands . In recent times, Israel has exponentially increased their violence and dispossession of the Palestinian people. The present response is simply an act of organized resistance to decades of Israeli aggression. It is an attempt to end Israel’s inhumane persecution of the Palestinian people– a crime against humanity.

Without provocation, Israeli settlers routinely raid and attack Palestinian villages, killing and injuring people, burning and destroying Palestinian homes, cars, shops and farms, killing livestock, and cutting down olive trees, a key element in the Palestinian economy. Israel keeps a “knee on the neck” of every Palestinian man, woman, or child, making life unbearable for them. Israel’s goal is to force the Palestinians off of their own land, sending them into exile in other countries, as Israel builds new settlements, further expanding their illegal occupation. These perpetrators are never held accountable. On the contrary, they are rewarded with increased access to stolen land. Not only do the powerful Western imperialist nations refuse to challenge Israel’s crimes, they support them, declaring that Israel “has a right to defend itself,” or labeling any criticism of Israeli policies as “anti-semitic” or “supporting terrorism.” The United States government picks-up much of the cost. Israel has been one of the top US aid recipients for decades, most recently receiving pledges of more than 38 billion US dollars over a 10 year period, plus additional funding for missiles.

The All-African People’s Revolutionary Party unequivocally condemns the 75 years of Israeli settler colonialism. As we have consistently pointed out, Zionism is racism. These same Zionist forces train the police and military in Africa and around the world to repress dissent by oppressed and exploited people. Israel is also a guarantor of imperialist access to Africa’s vast material resources. We stand in solidarity with the Palestinian people and their legitimate national aspirations. We uncompromisingly support their inalienable right to self-determination and freedom in their independent State of Palestine.

#blacktumblr#black history#black liberation#african history#aaprp#all african people’s revolutionary party#free palestine

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aight so, this semester I'm taking a media ethics class and it sounds like something Tumblr would enjoy and it will help me study so y'all are gonna get a kinda live blog, sound good?

Class hasn't started yet but we got some reading to do about the Abrams v US case from 1919

TL:DR A bunch of dudes got in trouble for publishing communist pamphlets during WWI and calling for a general strike so that the US would stop advancing into Russia during the Revolution

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions, although there was a dissenting opinion, and I'll get to that.

First though, some funnies

Three of the publishers were anarchists but one said he only wanted "a proper kind of government, not capitalistic." Justice Clark then expresses surprise that the US is, in fact, capitalistic and that isn't "proper"

The anarchists clarifying that they hate Germany just as much as the US, so if the US can get on with murdering them and not the Russians that would be great

Calling President Wilson, among other things, King Wilson, Our Kaiser, a shameful hypocrite, and my favorite, Too Much of a Coward to come out openly (yeah me too)

Ok, more serious under the cut

So the reason the Court upheld the conviction is that they were arguing that this is Clear and Present danger, akin to yelling fire in a movie theater. They argue that calling for a worker's strike during a war would be against the government interests enough to override the First Amendment's protections

I find the dissenting opinion much more interesting though

Justice Holmes starts by pointing out that the pamphlets were in fact, not attacking the US government but capitalism. Astute readers will note that those are in fact different. That is a point in his argument, and a very interesting one, but his main point is actually the following.

The publishers did not intend to work against the US government. That is an interpretation of their work by the courts

Basically, he's arguing that their actions should be gauged on their intent and not what their outcome may be.

He gives an example of a well meaning patriot who puts out an opinion arguing that the US needs to change their strategy in war, field more or less tanks, more or less jets. This guy might be right or wrong, but no one would say that he's committing a crime, even if by taking his advice the war effort would be damaged.

Similarly, the pamphlets are not trying to stop the war effort, merely to redirect it away from those they see as deserving it (which is a whole other can of worms but whatever)

While the effect of the pamphlets (general worker's strike, criticizing the president) may ultimately hinder the war effort, the intent behind them is something else entirely.

His third point: the Justices of the Court found it easy to condemn the publishers because they argued for Communism. Even Justice Holmes says that he thinks Communism is "the creed of ignorance and immaturity," so I'm guessing there wasn't a lot of power in the other point of view here.

But! Just because the Justices disagree with the ideas of the pamphlets doesn't mean that they are dangerous and/or should be dismissed and vilified.

Justice Holmes says that "the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the composition of the market." Seems ironic when talking about communism but all right. The point being that the government should not, according to the First Amendment, condemn specific points of view just because they disagree with them. Those points of view can fight it out among themselves.

I don't really have a point with all this, I just think it's kinda cool! I think the dissenting opinion is much more interesting and honestly very valid, but we can see how the actual decision was and is carried out, through McCarthyism and other government interference in media. Makes me wonder what might be different if we had a few more people willing to see Communists as human beings back in the day

These days I don't feel like we are a lot of direct government interference in media (the key words there are probably see and direct) but it can be good for us to think about it as well, whether we are criticizing the intent of words or the consequences we think we see.

Basically, I look forward to this class, should be fun. I'll let you know how it goes!

#Null's classes#media#history#politics#academia#yeah I don't know what's with all the random capitals#i just write like that#was this fun?

0 notes

Text

Feeling Sicko

The return of virus hysteria is an even worse throwback than the New Kids on the Block reunion. Some things should remain disbanded. Government commandeering decisions is a success if teaching everyone what gaslighting means counts. A movie not starring a Marvel character is as rare these days as not having existence itself dictated by those least qualified. Old souls favor sadly antiquated notions like plot and autonomy.

Processing 2020 more than halfway through 2023 is just another endless symptom. Struggling to breathe wasn’t merely literal. Interdictions are designed to show us who’s in control. As with providing your insurance, those with enough awareness to recognize what’s sinister notice who claims they provide everything.

The implication that our gods could confiscate necessities is just so you remember to worship fervently. Remember the casualness with which those who know what’s best for you made your rights disappear to be appreciative for the littlest bits of autonomy.

Lie blatantly if you’d like to protect seized power. I didn’t say they were clever. One doesn’t need to invent a convincing excuse when it’s easier to shrug and inquire what the oppressed plan to do about it. The ruling class is so ridiculous in boldness that you can’t believe someone would fib that openly. Dealing with sociopaths who think they know what’s best for you is the best endorsement of limited government possible. Unfortunately, telling people what to do continues to take precedent.

It turns out things running smoothly needs a lack of supervision. Government ruining everything offers a helpful reminder, and you didn’t even thank your overlords for the interventions. Making you appreciate life by interfering with it will have to suffice as gratitude. We don’t notice what a supply chain is until Joe Biden breaks the links. Bureaucrats ruining what they run is reminiscent of how people used to be able to walk down streets without being mugged. Fighting crime is now considered elitist, as poor thieves need to cope with the Democratic economy.

Nothing gets demonized by autocrats and their traitorous sycophants like making stuff. Scoffing at independence comes naturally to useless types who can’t imagine anyone else creating something valuable, either. The utter lack of empathy seals it. Trading work for currency is so bourgeoisie.

You lost your ability to make luxury decadent kulak indulgences like decisions. But at least the virus rampaged. The prototypical example of authorities not really being in charges created the best of both worlds otherwise.

Lingering side effects should serve as a lesson to any gentle dupes who believe government can and should care for us. Civics scores are bound to plummet when kids who were locked out of school see politicians enabling themselves to do as they please by shrieking about an emergency while scoffing at free exchange.

It’s bad enough to cede total control of reality. The worst part is how they totally suck at it. Couldn’t professional fibbers learn to deliver better ones? An inability to keep trains choo-chooing matches fecklessness in stopping illness. A ghastly example from which to learn is the most heartening news in a rather heartless world.

Contempt for your trifling liberty isn’t an exception. Remnants of restrictions show how they see everything else. Treating rights as privileges is a given with which you’re not allowed to dissent.

Those who just know they should be in charge substitute arrogance for competence. The curious swap is reminiscent of how they replace prosperity with free money. Your self-appointed superiors condescendingly scoffed at peasants who demanded to maintain decadent luxuries like commerce and earning. Ensuing ceaseless woe taught them a lesson about the economy, namely that prosperity results from trading so people can make what others want and not printing currency.

Unfortunately and as usual, everyone got punished for a fundamental misunderstanding of our world by the ruling class. When they announce we’re all in this together, they mean everyone suffers for their foolishness. Authorities are nice enough to let you keep some of their money and utter occasional blasphemous statements about individual freedom.

The crisis is not over. Sure, the virus seems to have gotten bored enough to dissipate. But the innately pushy who think they know what’s best for you want to perpetuate the crisis so they can keep making your decisions. It’s sure uncanny how every solution to nonstop red alerts involves not getting to think for ourselves. Egypt is a piker when it comes to endless emergency infringements.

The infection of capricious statism still spreads rampantly. Doing whenever they please is the chief indicator. There’s bound to be another reason to get nervous. Freaking is mandated. You always felt this panicked. Believe it by order.

0 notes

Text

The crime of doubting your elders

Ugh, it always gets my hackles up, when a Star Wars fic' plot twist involves someone being accused of having Fallen and resulting in that someone going on the lam.

Do you really think, it would have been that easy for the Order to counter Palps' convoluted plans, if all they needed was the identity of the Sith Lord? No.

Collecting Sith artifacts is not illegal. There is plenty of ugly art and abhorrent books in RL that gets collected by people with too much money and not enough morals. Malleus Maleficarum, for one thing, or Nazi paraphernalia for another.

Reading or discussing Sith texts and teachings is not illegal. It would completely defeat the purpose of the Jedi Order being the vanguard against the new Sith uprising. If someone starts to doubt the Jedi philosophy, you don't inoculate them against those doubts by mindlessly praying the dogma, you do it by taking those doubts seriously and talking them out to their logical conclusion. How are shadow operatives supposed to be successful undercover, if they can't sell to their marks that they fully believe something that goes against the Jedi belief tenets? And more importantly, how are they supposed to get back from their undercover persona, once the mission has ended? They would need to rebuild their old personality completely anew, and if simply learning something Dark is enough to Fall and is an imprisonable offense, who is going to guide them through that process? (By the way, the Order became dangerously close to being such an inflexible, dogmatic organisation that quashed all dissent - which is precisely why they became vulnerable. If Dooku's concerns hadn't been waved aside time and time again, he wouldn't have decided that becoming a threat to the Order by throwing his lot in with a Sith Lord was such a bright idea, but since he wasn't going to be unquestioning little follower, he saw no recourse).

The Order doesn't even have the monopoly on teaching about the Force or teaching Force-sensitives - Sith, as the more extreme outlier of the opposite beliefs aside, there are plenty of other Force traditions and schools of thought in canon. The Guardians of the Whills, the Green Jedi, the Grey Jedi, the Dathomiri Nightsisters - they are all still there and still legal.

The problem with the Sith and their philosophy is not that they exist and that people (again, Dooku as an example, as well as Sifo-Dyes have been established as being sort of experts in engaging with Sith on an academical level) want to disect those critically, it is that in order to be a practicing Sith, one usually commits acts of violence - which are already illegal under most Republic Laws, whether you use the Force for it or old-fashioned Molotov cocktails and blasters. Commiting genocide? Illegal. Killing a sentient being? As long as it wasn't done in self-defense - illegal. Stealing children, stealing property, defrauding or embezzling? Probably also all illegal. Makes absolutely no difference, what your religious and political affiliation is. Some of those crimes the Jedi, by the way, do as well, and yet no one is up in arms about all Jedi being declared criminals simply for being part of the Order. Because mind-tricking someone into cutting you a favorable deal is still fraud.

Sure, if someone finds out that the Chancellor collects Sith artifacts, this will automatically mark him as suspicious in every rational persons mind, and if the Order dug in, they would find evidence of his crimes. But the fact that he is a Sith, in and of itself, doesn't make him holding a political office illegal. Look at the real life politics - how many ultra-conservatives and nazis and racists have somehow managed to become legally elected representatives?

So, no, just because your character is suspected to have Fallen, there is absolutely no reason for them to go on the run. What is the Order gonna do, try to get them to see a mind healer? Boo-fucking-hoo, free session of psychotherapy, so what? It is only a suspicion. The Council would have first to prove that a) the character really has Fallen, b) that they did become specifically a Sith and not some other garden-variety Dark-Sider and c) that they committed some actual crimes, not just the thought-crime of no longer believing the Jedi doctrine. Until then - excuse me, but this esteemed Council is full of bantha-poodoo, and as suchnI have chosen to ignore their verdicts.

P. S. I actually resorted to googling whether there really was some sort of law in canon that I just forgotten about and it seems that there actually was an anti-Sith-law on the books in the Old republic. Which is insane. How do you teach future generations about how fucked up Sith philosophy is, if you can't even talk about it? How do you inoculate them against falling for the same shit again? Thats right - you don't. You end up with a whole generation ripe for recruitment by any wandering Sith Master. It is not that different that how suddenly laws are springing into life that forbid the teaching of critical race theory, which instead of inoculating the students against racism and inequality, allows it to flourish in plain view.

#reading fanfic#star wars#being a sith is not illegal#those who don't learn from history are bound to repeat its mistakes

0 notes

Text

In the world of dystopia, the government was a shadowy entity that lurked in the shadows, pulling the strings of power from behind the scenes. Its corruption ran deep, seeping into every aspect of society like a festering wound that refused to heal.

The ruling class was made up of the elite, who enjoyed lavish lifestyles at the expense of the downtrodden masses. The people had no voice, no representation, and no hope. Their lives were a never-ending cycle of poverty, oppression, and despair.

The government officials were ruthless and cunning, always looking for ways to consolidate their power and maintain their grip on the population. They used fear and intimidation to control the people, creating a climate of distrust and suspicion that kept the masses in check.

In this world, corruption was not just a way of life – it was the only way to survive. Everyone had their price, and the government officials knew exactly how to exploit their weaknesses. They used bribes, threats, and coercion to keep people in line, and anyone who dared to speak out or resist was quickly silenced.

The media was completely controlled by the government, serving as nothing more than a mouthpiece for its propaganda. The people were bombarded with lies and misinformation, and anyone who tried to spread the truth was labeled a traitor and punished accordingly.

The government officials lived in opulent palaces, surrounded by luxury and decadence while the people lived in squalor. The streets were filled with crime and violence, and the government did nothing to stop it – in fact, they often encouraged it as a way to keep the people divided and distracted.

In this world of dystopian corruption, there was no hope for the future. The people were trapped in a cycle of poverty and oppression, with no way out. The government was the enemy, and the people were powerless to resist its tyranny.

The government's power was absolute, its reach extending into every aspect of life in the dystopian society. But with great power came great corruption, and the ruling elite was not immune to the lure of personal gain.

In the corridors of power, deals were made in secret, alliances forged over champagne and cigars. The people were kept in line through propaganda and fear, their voices silenced by the state's ruthless suppression of dissent.

But the true extent of the government's corruption was hidden behind closed doors, shielded from public scrutiny by layers of bureaucracy and secrecy. At the highest levels of government, officials took bribes and kickbacks, embezzled public funds, and used their power to enrich themselves and their cronies.

Meanwhile, the people suffered, struggling to make ends meet as their hard-earned taxes were siphoned off into the pockets of corrupt officials. Healthcare and education were neglected, while the government poured money into lavish palaces and monuments to its own power.

For those brave enough to speak out against the government's corruption, there were harsh consequences. Dissenters were disappeared, their families threatened, their lives ruined.

The government's corruption had become so entrenched that it seemed impossible to root out. The people had lost faith in their leaders and their institutions, resigned to living in a world where those in power took what they wanted and left the rest to suffer.

But there were whispers of rebellion, of a movement growing in the shadows. The people were beginning to see that the only way to end the government's corruption was to tear it down and start anew.

As the dystopian society teetered on the brink of collapse, the people rose up, their voices united in a chorus of defiance. They demanded accountability, transparency, and a government that served the people, not itself.

And though the road ahead was long and fraught with danger, the people knew that they had no choice but to fight for a better future. A future free from corruption, where the government served the people, not the other way around.

0 notes

Text

I’ll go down the chain of reblogs here.

1- You know who statistically are less likely to be victims of violent crime? Gun owners. You know who is statistically more likely to stop a mass killing event? Gun owners. Most of the mass shootings take place in gun free zones for a reason.

2- The purpose of a sidearm is to acquire a rifle. Sidearms are also generally used for fighting thieves, carjackers, rapists, etc.

Rifles are for use on all threats from the above to fighting tyrannical government.

The “good guys with guns” thing hasn’t been debunked, you’re just lying.

The original source for between 500k to 3 million defensive uses per year came from the extremely anti gun Obama CDC. The FBI was even caught lying about the “no one stops mass shooters” stat.

Even if they hadn’t, mass shootings are an extremely rare occurrence in comparison to all other deaths. You’re more likely to die from that cheeseburger you had for lunch than to die in a mass shooting. Armed populations are significantly less likely to be attacked, whether by their own government or others.

3- You need to block anyone that disagrees with you, it seems. You’re just forming a bubble.

“No one is coming for your guns” is a total lie.

Leftist politicians are frequently threatening to do just as you say they aren’t.

If you need a license to practice a right, show me your free speech license. Your license to not be searched without a warrant. Your license to have a speedy trial. Etc, etc. That’s ignoring the government itself often enough isn’t even responsible enough to pass their own test. Gun owners are typically more law abiding than off duty cops.

4- And we go back to you forming a bubble, and hypocritically complaining about “muh ad hominems!” Despite all of your posts here being attacks and lies.

If you seriously think it’s the OTHER people spreading fear and hate while you’re out here calling all dissenters perverts (“gun fetishists”) and creeps and so on, I’d recommend getting some help. This is pretty textbook abuser behavior (accuse the victim of what the abuser does).

You use the “rational adults” argument, but it lands flat considering you’ve just lied about facts and insulted, deleted, and blocked the opposition. You aren’t arguing with a cult. You’re arguing with normies who poke holes in your argument.

It’s prudent to defend yourself, and have the means to defend yourself.

Owning and carrying a gun isn’t preventing anyone from doing those things. Firearm ownership isn’t gendered. Women need firearms just as much as men.

And the reason I responded to this post in the first place-

“The government is not out to get you. No one is coming for your guns.”

According to history, my ancestors were genocided by the US government- another tribe was gunned down right after a gun confiscation. On the spot.

And according to Robert Francis O'Rourke, sometimes known as Beto, “hell yes, we’re coming for your AR15s and AK47s!”

Democrats in the White House, senate, and house want to ban “assault weapons.”

According to actions taken by the democrats in the house, senate, and even White House, a handgun is an “assault weapon”. A semi automatic handgun that fires one round for one trigger pull.

How is this not coming for firearms?

Edit- Got blocked by OP for this gem. So blocking them in return I guess.

GuNS DoN’T KiLL PeoPLe, PeoPLe KiLL PeoPLe

Yeah, but it’s a lot harder for people who don’t have guns to shoot people. Yeah, maybe people are gonna do violence anyway, but that doesn’t mean we have to make it easy for them

512 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sins of the Father - 2:4

-|- Page header by space-b33 -|- Masterlist -|- Prince of Dathomir Masterlist -|- Sins of the Father Masterlist -|- Art Masterlist -|- Check out my : Ko-fi / AO3 -|- Prompt Challenges -|- Art Attack Weekly Challenge -|- Commissions Open -|- Join my tag list -|-

Maul x Nightsister OC (Zaiya Valessa) - Modern/Crime AU - Sins of the Father Masterlist

Word count: Approx 1250 Contains/Warnings: None Chapter Summary: Thrawn reports to his employer Notes: (more at the end)

Favours with Favours

Thrawn made his way back inside the building. To an outsider he might look cold, and business as usual, but on the inside, the young man was very pleased. An impromptu lunch date with a mysterious and beautiful woman? Moreover, an intelligent one? What could be better? He’d made several mental notes during the meal, most prominent that she definitely had something to hide. Which of course made her all the more intriguing. There was nothing he loved more than a puzzle.

She had given him open answers when discussing her history, though slightly too vague and full of double meanings. She was clever, too clever for her own good. It was a shame. Clever girls like that often got themselves into trouble. If she wasn’t careful… Well it would just be such a waste.

In truth the political world was something of a mystery to him, he much preferred people to say what they meant. The girl had said do too though he did notice she did not follow through with her actions. He had to wonder -- was she a liar for the fun of it? Or did she have to? Watching her, seeing the way she dressed herself, implied she wanted to express herself. Yet her actions said otherwise. She was a walking contradiction, but he did not yet have enough information.

The Mayor had wanted Thrawn as part of his ‘team’ not for his political aspirations - he didn’t really have any - but for the way his mind could spot the weakness in the Mayor’s opponents. Any threats were measured and assessed. Thrawn kept Palpatine protected.

Now he had to figure out if this girl was one of those threats.

The young Chiss man made his way up the stairs to the large stately office that housed the very seat in which the most powerful man in the city governed from. Palpatine was a shrewd man, and though not everything he did was completely “by the book”, Thrawn believed that this man was capable of doing what needed to be done for the sake of the city, to keep dissenters at bay and keep the peace.

The man himself sat, facing the large window that looked out into the courtyard where the fountain lay, bubbling away like a peaceful picture of tranquillity. Thrawn however knew from experience that the Lord Mayor was not looking at the fountain, but beyond it into the city itself. It was such a pity Palpatine did not have the same appreciation Thrawn did for beauty and culture. It was times like that that made him wonder if this path on which he was set… was it the right one?

“I take it you have a report for me?” Palpatine asked, seemingly knowing who it was before he turned his chair around. He laid his hands, fingertips pressed together on his desk and looked at the younger man with watery blue eyes.

“Indeed sir, I did my own reconnaissance this time, I was able to gain the information from a few trusted informants.” Thrawn unbuttoned his jacket as he took a seat opposite the older man, relaxing into his chair. “He seems… well successful might be a stretch considering his line of work, but it seems to be thriving.”

“Hmm…” Palpatine brought his hands up to his lips, in the same fingers together position, a thoughtful look on his wizened face. “That will not do, he needs to be brought down a peg.” Thrawn’s neat brows rose slightly.

“Did you not send your son out to make a name for himself? To find success?” the Deputy asked. It was strange, whilst Thrawn had never personally met Maul, Palpatine acted as though the event some years ago was beholden to a crime worth banishment, when by all accounts Thrawn had discovered it was Palpatine himself that had asked the Zabrak to take care of the situation. One small mistake had cost him his life as he knew it.

Thrawn of course knew that it was prudent to punish those that were incompetent, though the fallen son seemed hardly that.

Wasn't family important? Maybe not so much to Thrawn, whose family had not cared for him, bit the way Palpatine preached about the importance of family and the values… he had even adopted a boy -- even younger than his other son -- into the fold as an example. It seemed in the coming years, this Skywalker boy had completely replaced the first son. Thrawn had not seen any trace of the red and black skinned fellow anywhere, no photo nor trinket or any sort. It was as though Palpatine had attempted to erase his existence altogether.

Something about that sat odd with Thrawn, though he was not privy to domestic matters, so in the greater picture, it didn’t really matter.

“I sent him to learn, not to try and build a criminal empire in order for him to destroy me,” Palpatine sneered. “No, something must be done before things get out of hand and we need to clean up another of his messes.” The old man waved a dismissive hand, then lifted a finger as though he’d just had an idea. Thrawn suspected Palpatine had thought of this long before he even arrived in this office.

The moment was interrupted however by the phone on Palpatine’s desk ringing. His secretary knew better than to interrupt any of the Mayor’s meetings, and so it ought to be important.

“Yes?” he asked flatly as he answered. “Hm, I see, put him through.” Another pause. “I assume you have your reasons for this call, Commissioner Serenno?” Palpatine asked with a derisive tone. “Very well.” Thrawn could not hear the replies from Dooku but he got the gist when Palpatine reached for the remote and flicked to the correct channel on the large screen on the far wall.

Footage of the Amidala woman appeared. She was giving a speech to the sound of raucous applause and cheers. Thrawn glanced out of the corner of his eye, noting the displeased look crossing Palpatine’s face as he stared at the screen. The Mayor was wise enough to mask his true feelings, but the slight downturn of his mouth and crease to his brow told Thrawn enough. Displeased might have been an understatement.

“And yet another issue that needs taking care of…” he sighed and stood, leaning his gnarled hands on the table. His eyes were focused on the screen, the caption stating that she may have a greater chance in gaining votes from the lower classes and poorer citizens of Coruscant. That did not bode well for the campaign. Likely the campaign manager, Tarkin, was already planning multiple responses as they sat there.

Palpatine suddenly leaned into the phone receiver again, “the utter nonsense from this girl…” he scoffed. “Yes I can deal with it, but I need you to take care of my other problem. I think it’s time we call in a few favours, would you not agree?” There was a pause, Thrawn could hear Dooku’s voice rumbling through the phone though nothing distinctive. After a moment he hung up, but immediately began to dial another number. With his free hand, he waved Thrawn away, and the man knew better than to linger.

As he departed, he heard Palpatine speak, something about an upcoming event. Then there were some muffled sounds. Whoever it was on the other end of the line had a very bad cough.

Notes:

Hello friends!

I hope you enjoyed this chapter, I am nervous once more about how I write Thrawn, I still don't know him super well but I am doing my best to characterise him well. I have had a hard time writing this week so I am doing my best to get the chapters out. I do have a holiday coming up so I may need to take a brief break so I can enjoy my time to the fullest. So if the next chapter is delayed, that is why! But for now, please enjoy!

In the next part, Maul makes contact with the ones that raided the warehouse!

As always -- I love feedback and comments, so please please, if you can spare a moment, I'd love to know what you think!

Until next time!

----

The List of Tags: (If your name is crossed out then check your settings! Tumblr is not letting me tag you!) @two-black-leviathans @fallenrepublick @eyecandyeoz @ashotofspotchka @littlepossss @octupus-on-the-moon @justalittletomato @mach-opress @mustluvecho @nahoney22 @leotatombs @eloquentmoon @the-chains-are-the-easy-part @maulslittlemeowmeow @misogirl828 @alwayssnivellus @stardustbee @lune-de-miel-au-paradis @bacarasbabe @nobody-expects-the-inquisitorius @rain-on-kamino

Wanna be notified when I post my next work? Join my tag list

#sins of the father#star wars#nightsister oc#darth maul#maul x oc#maul fic#darth maul x oc#darth maul fic#lord maul#modern au#crime au#thrawn#palpatine#count dooku#yan dooku

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

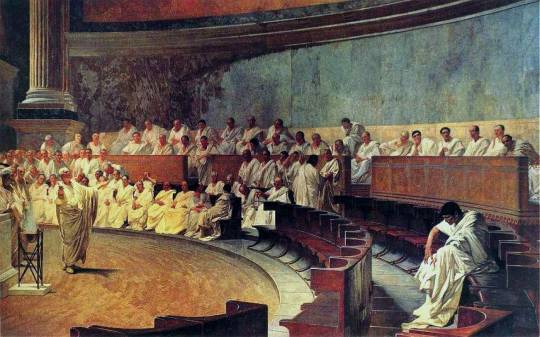

No Power Left to the Vanquished

My feelings, Conscript Fathers, are extremely different, when I contemplate our circumstances and dangers, and when I revolve in my mind the sentiments of some who have spoken before me. Those speakers, as it seems to me, have considered only how to punish the traitors who have raised war against their country, their parents, their altars, and their homes; but the state of affairs warns us rather to secure ourselves against them, than to take counsel as to what sentence we should pass upon them. Other crimes you may punish after they have been committed; but as to this, unless you prevent its commission, you will, when it has once taken effect, in vain appeal to justice. When the city is taken, no power is left to the vanquished.

- Sallust, quoting Cato the Younger, Bellum Catilinae

In the late years of the Roman Republic, a conspiracy arose from within the ranks of the Senate. The aristocrat Lucius Sergius Catilina attempted to seize control of the government after his bid for consulship failed. One of the consuls, Cicero, exposed the conspiracy and Catilina fled Rome to prepare an army. Five of the conspirators were captured after the letters they wrote, in which they urged people to join the conspiracy, were intercepted. The letters were read before the Senate and Cicero urged for the execution of their authors.

Julius Caesar pled for patience and clemency; after all, Rome had laws and customs to observe. He did not want to set a precedent that the ways of Rome could be set aside because they were inconvenient. Cato the Younger, a longtime (and future) opponent of Caesar, spoke next. His appeal won out because the Senate understood the reality of the scenario he was describing: when an institution is in imminent danger from those who seek to dismantle it, you must question if strict adherence to the institution’s laws and customs is worth more than the existence of the institution itself.

Fourteen years later, Julius Caesar, champion of Roman laws and customs, crossed the Rubicon in defiance of law, custom, and the explicit order of the Senate to mark what would become the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of Caesar’s rule of the Roman Empire. Caesar’s respect for Roman norms and civitas ended when they put him in personal danger. As for Cato, he died with the republic and subsequently became its most lionized martyr.

In 1923, Adolf Hitler and Erich Ludendorff, accompanied by hundreds of other Nazis and members of the paramilitary Sturmabteilung staged the Beer Hall Putsch, an attempted coupe d'état against the regional Bavarian government. Hitler’s goal was to pressure the elected representatives in Munich to turn against the federal government in Berlin through a public show of force and violence. It failed. Hitler was imprisoned, but he used his trial testimony to continue spreading his propaganda and dictated Mein Kampf while serving his sentence. The Beer Hall Putsch was a success for the Nazi party in spite failing to achieve Hitler’s goals.

Ten years later, Hitler was the presidentially-appointed Reichskanzler of Germany. While the Nazis had the most seats in the Reichstag, it was still a minority party. To ensure the passage of the Enabling Act, which gave the chancellor the power to enact laws without the involvement of the Reichstag, Hermann Göring, President of the Reichstag, suspended the rules for quorum and outlawed the opposition KPD (Communist party) from participating. Sturmabteilung forces entered the assembly chamber to surround and intimidate the non-Nazi representatives into voting for the law. The passage of the Enabling Act marked the end of the Weimar Republic and the beginning of Hitler’s dictatorship over the German Reich.

The differences between the Beer Hall Putsch and and the Enabling Act were differences of organizational power, instruments, and outcome, not intent. In both cases, the same bad actors were seeking to overthrow an existing government. President Paul von Hindenburg and Franz von Papen failed to recognize that Hitler and the Nazis not only threatened the principles of the aristocracy or their other political opponents, but the Weimar Republic itself.

Was the Weimar Republic worth saving? It was, by most accounts, including the little my grandmother remembered of it, an awful state. Its government was, putting it mildly, dysfunctional. Many of its citizens lived through an era of terrible poverty and violence following the end of the first World War. But the Reich is what came after. All other avenues of evolutionary institutional or truly revolutionary change ended with the fall of the republic. The world suffered for it.

Trump and his allies have been attacking American institutions for the last four years. Trump doesn’t have the ideological drive of Hitler or the strategic acumen of Caesar. He just has the most base populist instincts to agitate a mob. What he shares with Hitler, Caesar, and other would-be dictators is a desire to remove opposition and the institutional mechanisms of opposition through whatever means are at his disposal. If he can do it through an executive order, he will. If he can do it through political pressure, he will. If can do it through intimidation, quid pro quo exchanges, and other illegal actions, he will. And if it requires a mob of supporters to storm the capitol during a Senate session to overturn their certification vote, he’ll try use that, too.

People have been likening what happened in the U.S. capitol to the Beer Hall Putsch. It’s a fair and reasonable comparison, though Hitler did actually march in his own coup attempt and was wounded during its defeat; Trump just gathered people together, lit a fuse, and watched them go. But it’s important to remember that the differences between the Beer Hall Putsch and the Enabling Act were of organizational power, instruments, and outcome. What if there had been more pro-Trump agitators at the capitol? What if the Senate had not been evacuated in time? What if Trump had more supporters within the Senate to begin with? What if Trump were even mildly more intellectually competent or the various online factional leaders in his mob were more coordinated in their tactics and goals?

Facebook, twitter, and other social media sites have deplatformed Trump. Several companies have suspended hosting services for online communities that have been involved in coordinating fascist, white supremacist mobs in the past. Trump’s supporters, in ignorance or bad faith, have decried that this violates 1st Amendment rights. They are wrong, but even if they were not, the events of January 6th, planned armed protests on the 17th, and threats of violence against Biden’s inauguration on the 20th, represent the kind of imminent institutional danger that Cato spoke of during the Catiline Conspiracy. “When the city is taken, no power is left to the vanquished.”

We have wrestled with how the government and corporations should moderate social media since these platforms emerged. We will continue to do so in the future. While we must take guard against the transformation of severe actions in time of crisis into the de facto way of handling our day-to-day problems, we must also recognize and act to resolve crises as soon as they appear if we have any interest in preserving the institutions they threaten.

I think of myself as a socialist. My political thought is not as educated, as principled, or as nuanced as many other socialists I know, some of whom think that any efforts to preserve or work within existing American institutions is, at best, naïve; in practice, counterproductive; and, at worst, actively reactionary. I often look at our institutions through the lens of a designer. When I do, I see systems that do not work to produce meaningful social change. I see systems which do not often work to accomplish any goals of its body politic. In practice, our systems serve the needs and interests of the ruling class and the powers that have the means and knowledge to manipulate the members of that class. The systems confine the use of violence and its instruments to the state, as the state sees fit, often to the detriment and mortal peril of the most disadvantaged and vulnerable among us. It is hard for me to sympathize with those who deify the state and its institutions, especially a state like America that treats its citizens so cruelly. It becomes even harder when adjacent political cousins perennially denounce any hesitance to support milquetoast centrist candidates as tantamount to treason. Even so, when fascists, white supremacists, advocates of genocide are positioning themselves to imminently dismantle these institutions through intimidation and violence, it is not difficult for me to see the value in their immediate preservation.

But if the state and its institutions do survive the next few weeks, we will still live in a world where social media and the principles of freedom of speech are vulnerable to the predations of those who would use their contentious legal status to spread lies, foment popular dissent, and, if necessary, coordinate another violent coup d'état when the time is ripe. The next time, perhaps the popular figurehead will not be as ignorant, as incompetent, as craven, as plainly stupid as Donald Trump. You can already see his would-be successors positioning themselves for 2024 in the waning hours of his presidency. The next time, the populist agitators may be more focused in their goals, more coherent in their strategy, more careful in their communication. Those among them who have witnessed the spectacular failure of imbeciles like Jake Angeli, Adam Johnson, and Richard Barnett may be shrewd enough to learn from the disaster as they prepare for the future.

The Weimar Republic became vulnerable to the schemes of the Nazi party because its representatives failed to address the needs of its citizens and because its leaders failed to recognize the magnitude of threat posed by leaders like Adolf Hitler, propagandists like Goebbels, and paramilitary groups like the Sturmabteilung. Our elected representatives may have finally, at this recent brink of disaster, comprehended the threat that Trump and his supporters pose to the existence of the state. After they make their way through January 20th, the federal government will have to address the needs of a disaffected, impoverished, violently-policed, often disenfranchised populace. They will also have to disentangle the mess that the government has created through their laissez-faire attitude toward social and news media regulation. Their actions in the immediate future will tell if they intend to effect meaningful change or if they are content to use the next four years to pave a road to the ruin of the republic.

547 notes

·

View notes

Text

You can always tell how important narrative control is by watching the way people react when their control of the narrative is jeopardized.

Empire apologists are raging at Amnesty International for pausing its aggressive facilitation of western imperialism to issue one brief criticism of the way Ukrainian forces have been endangering civilian lives with their warfare tactics against the Russian military.

Amnesty is far from the first to highlight this extensively documented issue; that Ukrainian forces have been deliberately positioning themselves in civilian populations without taking proper measures to protect noncombatants is a concern that has been voiced repeatedly since the war began and reported on by both mainstream western news outlets and the United Nations.

Nevertheless, Amnesty’s claim that “Ukrainian forces have put civilians in harm’s way by establishing bases and operating weapons systems in populated residential areas, including in schools and hospitals” has drawn fire from Ukrainian officials, from mass media pundits, from the brainwashed rank-and-file on social media, and from President Zelensky himself.

A common criticism circulating among the outrage is that Amnesty is facilitating Russian propaganda, has been influenced by Russian propaganda, or has itself become an instrument of Russian propaganda.

The head of Amnesty International’s Ukrainian branch resigned as a result of the report, saying that “the organization created material that sounded like support for Russian narratives” and that in an effort to protect civilians, “this study became a tool of Russian propaganda.”

“It is a shame that the organization like Amnesty is participating in this disinformation and propaganda campaign,” tweeted Zelensky advisor Mykhailo Podolyak.

“Amnesty International can go to hell for this garbage,” tweeted Human Rights Foundation Chairman Garry Kasparov. “Or go to Ukraine, which Putin’s war is trying to turn into hell. As with their actions on Navalny, it reeks of Russian influence turning Kremlin propaganda into Amnesty statements.”

The Daily Mail called the Amnesty report “a coup for Vladimir Putin’s propaganda machine.”

“The organization gives a huge assist to Russian propaganda,” tweeted Oleksiy Sorokin, chief operating officer of the NATO propaganda outlet Kyiv Independent.

“Shameful victim-blaming. Russia invaded Ukraine and is committing unspeakable war crimes there. Please do not amplify Russian lies,” tweeted Paul Massaro of the US government’s Helsinki Commission.

The underlying premise behind these complaints, of course, is that it is Amnesty International’s job to help Ukraine win a propaganda campaign against Russia. Which is odd, because Amnesty’s reporting on the war has actually been overwhelmingly biased in favor of Ukraine this entire time.

“Anger directed at Amnesty is surprising given that it is the first critical piece the group has written on Ukraine since the war began,” reports Unherd. “Over the last six months, Amnesty has published 40 articles on Ukraine, nearly all of which condemn Russia’s invasion, with only one exception — its latest — that could be conceivably described as critical of Ukraine.”

Even the Amnesty report currently sparking all the outrage contains repeated condemnations of Russia’s actions in Ukraine, citing “indiscriminate attacks by Russian forces” and “war crimes” Amnesty has found Russia guilty of committing, as well as decrying the use of “inherently indiscriminate weapons, including internationally banned cluster munitions.”

But even ninety-nine percent loyalty to the official line is not enough for imperial spinmeisters and the empire’s useful idiots. Anything short of 100 percent compliance counts as Russian propaganda.

But that’s precisely the notion that has been drummed into western consciousness with ever-increasing fervor since 2016: that any dissent about US foreign policy is Russian propaganda. Don’t support western interventionism in Syria? You’re spouting Russian propaganda. Worried about nuclear war? Russian propaganda. Don’t think the fight for US unipolar domination is worth all this dangerous brinkmanship? Russian propaganda. Don’t like the idea of an expensive proxy war with no exit strategy whose economic fallout is making life harder and harder for more and more people all around the world? Russian propaganda.

I myself am accused of being a peddler of Russian propaganda many times per day, and have been for years. This despite my hardly ever consuming Russian media, never receiving a penny from Russia, and never having worked for the Russian government or any other government at any time. Russian media have at times chosen of their own initiative to amplify my work since I have a standing invitation for anyone to do so, but I’m literally just an Australian woman writing her opinions online with her American husband. I only qualify as “Russian propaganda” because I disagree with US foreign policy.

Ask anyone who says a criticism of the western empire’s Ukraine policy is “Russian propaganda” to name a critic of western Ukraine policy who they don’t consider a Russian propagandist. They won’t be able to. For them, disagreeing with one’s government about Ukraine is itself Russian propaganda.

For empire apologists the measure of what constitutes “Russian propaganda” about Ukraine has nothing to do with whether or not what’s being said is true or valid; it’s literally just a question of obedience to one’s government about the decisions it’s been making with regard to that nation.

If the measure of whether something qualifies as propaganda is defined entirely by whether it agrees with one’s government, then that measure is itself propaganda.

That’s exactly what’s happening with criticism of the west’s interventionism in Ukraine. Something doesn’t have to come from Russia to be considered Russian propaganda, and its source doesn’t need to have any connection to the Russian government. It doesn’t even have to be false. All it needs to be is disobedient.

We saw this illustrated this past June when The Guardian published a NATO-backed claim that journalist Aaron Maté was “the most prolific spreader of disinformation” among a “Russia-backed network of Syria conspiracy theorists,” despite being incapable of citing a single false thing in Maté’s Syria reporting, and despite The Guardian having to hastily edit out their “Russia-backed” claim.

We also saw this illustrated this past June in a University of Calgary briefing paper on “disinformation” about the war in Ukraine which warns about “five primary narratives” being circulated online:

1. Implying NATO expansionism legitimizes the Russian invasion 2. Portraying NATO as an aggressive alliance using Ukraine as a proxy against Russia 3. Promoting a general mistrust in institutions and elites 4. Suggesting that Ukraine is a fascist state or has extensive fascist influences 5. Promoting a specific mistrust of Canada’s Liberal government, and especially of Prime Minister Trudeau

There are arguments of varying strengths to be made for every one of those points, but more importantly it is self-evident that all of them are matters of opinion and none of them meet any sane definition of “disinformation”. They also can’t in and of themselves rightly be called either “Russian” or “propaganda”.

Russian propaganda certainly exists, and the Russian government certainly has a vested interest in influencing western thought in its strategic favor to whatever extent it is capable. But its capability is very, very limited, especially compared to the exponentially greater influence that western institutions have over our minds.

Russia has a few trolls and some media outlets that were barely viewed by westerners even before they were banned; the US-centralized empire has the billionaire media, Silicon Valley, Hollywood, and the education system. Comparing the two is like comparing a candle to the sun, and the sun ain’t Russia. But that’s the one whose influence over our minds we’re meant to worry about.

In reality we are swimming in propaganda that is favorable to the US empire our entire lives; it’s so ubiquitous that people don’t even notice it. Claiming your support for US foreign policy on an issue has nothing to do with being propagandized is like someone who was raised in the Westboro Baptist Church claiming it was pure coincidence that he happens to agree with the church on the sinfulness of homosexuality. It pervades our minds and shapes our society, but they want us all freaking out about the virtually nonexistent problem of “Russian propaganda”.

This is a thought-killing dynamic, and it is a major problem. It is not good that propaganda is shoved into our minds manufacturing consent for dangerous escalations between the world’s two greatest nuclear powers while anyone who opposes any part of it is dismissed as a Russian propagandist or a useful idiot of the Kremlin.

We should be using our minds more at this critical juncture, but these dynamics put in place by imperial narrative managers have instead got us using them a lot less.

Old joke:

A Russian and an American get on a plane in Moscow and get to talking. The Russian says he works for the Kremlin and he’s on his way to go learn American propaganda techniques.

“What American propaganda techniques?” asks the American.

“Exactly,” the Russian replies.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yup, Sure Was a Finale

I had an epiphany. The reason why I never re-watched the final two parts of Sozin’s Comet even though I’ve popped in episodes at random many times over the years isn’t that I can’t bear the sadness of seeing one of the best, most engaging narratives out there come to an end.

It’s simply that the finale isn’t all that good.

Some honorable mentions of what was enjoyable.

(+) This

Just this.

(+) The Church of Zutara has another convert

“Are you sure they don’t get together?” Hubster, 2020

(+) The tragedy of Azula

And the fact that it’s acknowledged as such. I hope Zuko will do his best to get her help and have a relationship with her…

(+) Sokka being a big bro

And the whole airship sequence in general. It’s wonderfully paced and plotted, with moments of humor, real stakes, Toph being both badass and a scared crying kid, Sokka strategizing and protecting, Suki saving the day, and non-benders being instrumental in thwarting the bad guy firebender’s plans. Would be shame if Bryke never portrayed them this capable ever again…

And now for the main course.

(-) Blink and its over

The wrap-up feels too quick (hashtag Needs More ROtK-style False Endings). A part of this is due to how fast the story goes from the thick of the action to hastily tying up a bunch of loose ends, but the larger issue is how Book 3’s uneven pacing comes home to roost. After spending half a season on filler episodes that at best subtly flesh out established characters while dancing around a huge lionturtle-shaped hole, and at worst contradict the theme of “no one is born bad” with “you’re a hot mess because your great-grandfathers didn’t get along too well”, the frantic “go go go” rush of the second half screeches to a halt with “they won and everyone was happy because now the right people have power and it will be all good from now on yup nothing more to deal with baiiiii”.

Yes, I know, it’s a kids’ show. But goddamn, this particular kids’ show has proven so many times it can do better than the expected tropiness. Showing the characters in their roles as builders of a new world was the least that could have been done.

Oh well!

(-) Ursa

We’ll never know. There will never be a story that delves into this. Yup. Shall forever remain but an intriguing mystery. Is good, though. Mystery is better than a story where Ursa shares her son’s penchant for forgetfulness. Imagine how embarrassing that would be. Speaking of which…

(-) What does Mai see in this jerkbender?

Look, I like to harp a lot on the mess of inconsistent writing that’s Mai but let’s unpack this scene from her perspective, shall we?

Zuko forgot about her! It totally slipped his mind that the one person who prioritized the safety of his dumb ass was rotting in the worst prison in the Fire Nation—because of him! And she was rotting there long enough after the final Agni Kai for the news of Zuko’s upcoming coronation to spread and her uncle to feel sufficiently secure to release her. But then the coronation scene is attended by every single member of Gaang & Friends that was imprisoned?

So what this tells me is that either a) the invasion force had the ability to break themselves out the whole time and for some reason decided not to exercise it until after the war was over, b) Zuko forgot about them as well and no one thought to remind him there were prisons full of POWs until Mai arrived, or, and that’s even better, c) Zuko took care to free every single resistance fighter while making sure Mai would be the one to stay behind bars.

Never thought I’d say this but Mai? Honey? You deserve so much better.

(-) “What does Katara want?”

Asked no one in the writers’ room ever, apparently.

This is not so much anti Cataang as anti romance stories that pay attention to the needs, opinions, and wants of only one partner in general. Over the previous 60 episodes, Katara actively expressed romantic interest in Aang exactly, wait for it,

Once.