#the book is called ‘governance feminism: an introduction’

Text

There’s this quote by author Janet Halley that goes “the line between prophetess and madwoman is very thin and constantly moving,” and although it speaks of how women must go to greater lengths than men to earn their credibility, it always makes me think of Elain.

“The line between prophetess and madwoman is very thin.”

#my entries#janet halley#elain archeron#acotar#a court of thorns and roses#the book is called ‘governance feminism: an introduction’#it has some really good nuggets of information#but it isn’t the most interesting read...#someone from our team please score soon

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

10.02.2024

Worldbuilding: Worked on a post on the geography, flora & fauna of The Sorcerer's Apprentice universe which I meant to publish last week, but was unable to finish due to life circumstances (my favourite aunt went to intensive care, and I caught a nasty stomach bug while visiting her). At any rate, it's almost done, so it should go up sometime next week.

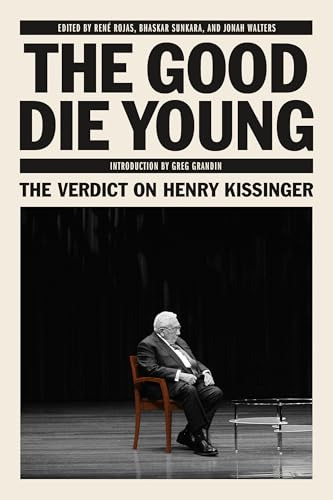

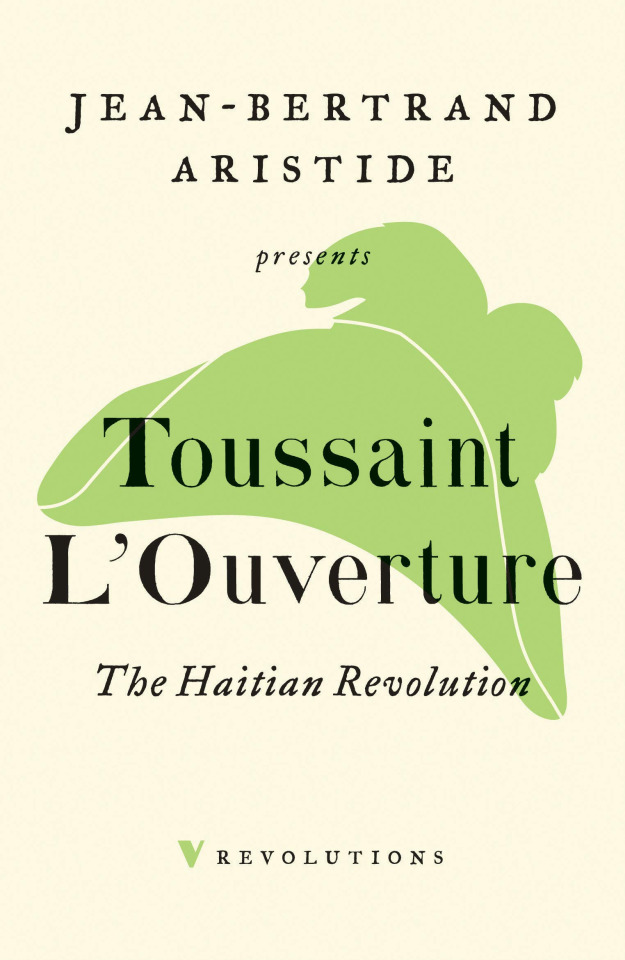

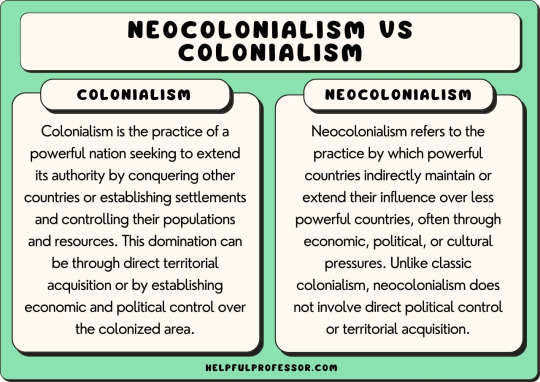

Continued Researching Colonialism, Neocolonialism, Coloniality as a Concept and Decolonial Practices: I've been reading Edward W. Said's Culture and Imperialism for the last few weeks and I'm making slow but steady progress. My plan is to pick up Said's Orientalism next, which I've heard is also a go-to text on colonialism. In addition, I also read A Decolonial Feminism by Francoise Verges, which I found quite eye-opening and will be incorporating into Altaluna's storyline (namely, I'll be showcasing how some forms of feminism are used to further colonial aims through interactions between Altaluna and her supposedly 'transgressive' peers); The Good Die Young: The Verdict on Henry Kissinger, a compilation of essays on how Kissinger (who I met in his declining years) used and abused human rights discourse to further US economic control (capitalism with US supremacy incorporated) over so-called 'third-world' regions, and how this is the standard practice for US foreign policy to this day (I'm borrowing this two-pronged approach for interactions between the Empire and it's subordinate 'independent' states); and Toussaint L'Ouverture: The Haitian Revolution, a compilation of Toussaint's (and a couple others, including Napoleon's) correspondence during Toussaint's fight for independence. The book features an outstanding introduction by Jean-Bertrand Aristide and offers a stark contrast to Kissinger's views on Human Rights; in Toussaint's letters and speeches, these rights come with no strings attached and are pursued on principle, out of the genuine belief that they are inalienable to all (at one point the British offered to 'make him' King of Haiti and he refused, which I have to admit, I was pretty impressed by). I also did quite a lot of follow-up reading on Haiti, as an example of the colonialism-to-neocolonialism pipeline. Given that The Sorcerer's Apprentice is set in a neo-colonial world, reading up on Haiti's history helps me better portray the continuity between these two systems and indirectly criticize the idea that today both my readers and I live in a post-colonial world. BTW, if you're unfamiliar with the horrors visited upon the Haitian people (did you know that up until 2015, when France 'forgave' them their debt, the government of Haiti had been paying the French compensation for their loss of slave labour?), check out this article. Likewise, if you're unfamiliar with the difference between colonialism and neo-colonialism (as I was for 99.9% of my life lol), take a look at the iconographic below.

Researched Fiction Genres in 'Post-colonial' Literature: The various iterations of The Sorcerer's Apprentice I've written so far have experimented with two main genres, fantasy and horror. The first iterations were straight-up typical high fantasies with Kings and Queens and dragons in a UK-style setting; the second were more realistic but much more eerie psychological horror stories set in modern-day New York City (if you scroll back far enough on this blog, you'll find evidence of both). Although I like some elements/scenes from both genre adaptations of The Sorcerer's Apprentice and, indeed, although I intend to incorporate some of these in the current draft, ultimately I abandoned the aforementioned versions because, at their core, they failed. Why? Because, while they nailed the interpersonal struggle between Valeriano and Altaluna, they did so without addressing the reason that struggle even exists in the first place. Namely, they failed to go beyond the personal relationship, to its systemic causes. The truth is that a person like Valeriano doesn't exist in a vacuum. He's a product and embodiment of a world with certain values. Yes, Altaluna may have defeated him in a high-fantasy royal skirmish for power or its modern-day equivalent inheritance drama, but engaging (even embracing) the system that produced him (royalty, birthright, etc.), undermines her victory. What was she in these earlier versions of The Sorcerer's Apprentice, but another shade of Valeriano? What did she represent, in her victory if not the desire to be the oppressor? The deep self-depreciation of the oppressed? Even the aesthetics of these earlier versions glorified Valeriano's world, with little mention of Altaluna's. This was my fault. I did not understand that these things were in me. I am beginning to. In any case, I don't intend to make the same mistake twice, so I'm doing a little research into how different literary genres have been used to tell stories about colonialism/neocolonialism/post-colonialism. I read a pretty good article from Globalization, Utopia, and Postcolonial Science Fiction: New Maps of Hope by E. Smith entitled "Third-World Punks, or, Watch out for the Worlds Behind You," and I'm trying to look into Afrofuturism and Latinfuturism.

REMINDERS:

Answer pending asks. Yes, I am bad. I admit it, I am very bad. (why am I so bad *sobs*)

Publish that promised worldbuilding post on the geography, flora & fauna of The Sorcerer's Apprentice universe.

Survive this stomach bug.

TAG LIST: (ask to be + or - ) @the-finch-address @fearofahumanplanet @winterninja-fr @avrablake @outpost51 @d3mon-ology @hippiewrites @threeking @lexiklecksi @achilleanmafia

© 2024 The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. All rights reserved.

#writeblr#writeblr community#progress update#biweekly progress update#worldbuilding#writeblr cafe#writers on tumblr#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#original fiction#wip#writer community#writing blog#creative writing#writer stuff#writblr#writblr community#WIP: THE SORCERER'S APPRENTICE#WIP: The Sorcerer's Apprentice

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recommended reading for leftists

Introduction and disclaimer:

I believe, in leftist praxis (especially online), the sharing of resources, including information, must be foremost. I have often been asked for reading recommendations by comrades; and while I am by no means an expert in leftist theory, I am a lifelong Marxist, and painfully overeducated. This list is far from comprehensive, and each author is worth exploring beyond the individual texts I suggest here. Further, none of these need to be read in full to derive benefit; read what selections from each interest you, and the more you read the better. Many of these texts cannot truly be called leftist either, but I believe all can equip us to confront capitalist hegemony and our place within it. And if one comrade derives the smallest value or insight herefrom, we will all be better for it. After all... La raison tonne en son cratère. Alone we are naught, together may we be all. Solidarity forever.

***

(I have split these into categories for ease of navigation, but there is plenty of overlap. Links included where available.)

Classics of socialist theory

~

Capital (vol.1) by Karl Marx

Marx’s critique of political economy forms the single most significant and vital source for understanding capitalism, both in our present and throughout history. Do not let its breadth daunt you; in general I feel it’s better to read a little theory than none, but nowhere is this truer than with regards to Capital. Better to read 20 pages of Capital than 150 pages of most other leftist literature. This is not a book you need to ‘finish’ in order to benefit from, but rather (like all of Marx’s work) the backbone of theory which you will return to throughout your life. Read a chapter, leave it, read on, read again.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Capital-Volume-I.pdf

The Prison Notebooks by Antonio Gramsci

In our current epoch of global neoliberal capitalism, Gramsci’s explanation of hegemony is more valuable than much of the economic or outright revolutionary analyses of many otherwise vital theory. Particularly following the coup attempt and election in America, as well as Brexit and abusive government responses to Covid, but the state violence around the world and the advent of fascism reasserts Gramsci as being as pertinent and prophetic now as amidst the first rise of fascism.

https://abahlali.org/files/gramsci.pdf

Imperialism: The Highest Stage Of Capitalism by V.I. Lenin

Like Marx, for many Lenin’s work is the backbone of socialist theory, particularly in pragmatic terms. In much of his writing Lenin focuses on the practical processes of revolutionary transition from capitalism to communism via socialism and proletarian leadership (sometimes divisively among leftists). Imperialism is perhaps most valuable today for addressing the need for internationalist proletarian support and solidarity in the face of global capitalist hegemony, arguably stronger today than in Lenin’s lifetime.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc/imperialism.pdf

Socialism: Utopian And Scientific by Friedrich Engels

Marx’s partner offers a substantial insight into the material reality of socialism in the post-industrial age, offering further practical guidance and theory to Marx and Engels’ already robust body of work. This highlights the empirical rigour of classical Marxist theory, intended as a popular text accessible to proletarian readers, in order to condense and to some extent explain the density of Capital. Perhaps even more valuable now than at the time it was first published.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/index.htm

In Defense Of Marxism by Leon Trotsky

It has been over a decade since I have read any Trotsky, but this seems like a very good source to get to grips with both classical Marxist thought and to confront contemporary detractors. In many ways, Trotsky can be seen as an uncorrupt symbol of the Leninist dream, and in others his exile might illustrate the dangers of Leninism (Stalinism) when corrupt, so who better to defend the virtues of the system many see as his demise?

https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/idom/dm/dom.pdf

The Conquest Of Bread by Pyotr Kropotkin

Krapotkin forms the classical backbone of anarchist theory, and emerges from similar material conditions as Marxism. In many ways, ‘the Bread book’ forms a dual attack (on capitalism and authoritarianism of the state) and defence (of the basic rights and needs of every human), the text can be seen as foundational to defining anarchism both in overlap and starkly in contrast with Marxist communism. This is a seminal and eminent text on self-determination, and like Marx, will benefit the reader regardless of orthodox alignment.

https://libcom.org/files/Peter%20Kropotkin%20-%20The%20Conquest%20of%20Bread_0.pdf

Leftism of the 20th Century and beyond

~

Freedom Is A Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, And The Foundations Of A Movement by Angela Davis

This is something of a placeholder for Davis, as everything she has ever put to paper is profoundly valuable to international(ist) struggles against capitalism and it’s highest stage. Indeed, the emphasis on the relationship between American and Israeli racialised state violence highlights the struggles Davis has continually engaged since the late 1960s, that of a united front against imperialist oppression, white supremacists, patriarchal capitalist exploitation, and the carceral state.

https://www.docdroid.net/rfDRFWv/freedom-is-a-constant-struggle-pdf#page=6

Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic Of Late Capitalism by Frederic Jameson

A frequent criticism of Marxism is the false claim that it is decreasingly relevant. Here, Jameson presents a compelling update of Marxist theory which addresses the hegemonic nature of mass media in the postmodern epoch (how befitting a tumblr post listing leftist literature). Despite being published in the early ‘90s, this analysis of late capitalism becomes all the more pertinent in the age of social media and ‘influencers’ etc., and illustrates just how immortal a science ours really is.

https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/jaro2016/SOC757/um/61816962/Jameson_The_cultural_logic.pdf

The Ecology Of Freedom: The Emergence And Dissolution Of Hierarchy by Murray Bookchin

I have not read this in depth, and take issue with some of Bookchin’s ideas, but this seems like a very good jumping off point to engage with ecosocialism or red-green theory. Regardless of any schism between Marxist and anarchist thought, the importance of uniting together to stem the unsustainable growth of industrialised capitalism cannot be denied. Climate change is unquestionably a threat faced by us all, but which will disproportionately impact the most disenfranchised on the planet.

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/murray-bookchin-the-ecology-of-freedom.pdf

Why Marx Was Right by Terry Eagleton

I’ve only read excerpts of this; I know Eagleton better for his extensive work on Marxist literary criticism, postmodernity, and postcolonial literature, so I’m including this work of his as a means of introducing and engaging directly with Marxism itself, rather than the synthesis of diverse fields of analysis. But Eagleton generally does a very good job of parsing often incredibly dense concepts in an accessible way, so I trust him to explain something so obvious and self-evident as why Marx was right.

https://filosoficabiblioteca.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/EAGLETON-Terry-Why-Marx-Was-Right.pdf

By Any Means Necessary by Malcolm X

Malcolm X is one of the pre-eminent voices of the revolutionary black power movement, and among the greatest contributors to black/American leftist thought. This is a collection of his speeches and writings, in which he eloquently and charismaticly conveys both his righteous outrage and optimism for the future. Malcolm X’s explicitly Marxist and decolonial rhetoric is often downplayed since his assassination, but even the title and slogan is borrowed from Frantz Fanon.

Feminism and gender theory

~

Sister Outsider: Essays And Speeches by Audre Lorde

The primary thrust of this collection is the inclusion of ‘The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master’s House’, probably Lorde‘s most well known work, but all the contents are eminently worthwhile. Lorde addresses race, capitalist oppression, solidarity, sexuality and gender, in a rigourously rhetorical yet practical way that calls us to empower one another in the face of oppression. Lorde’s poetry is also great.

http://images.xhbtr.com/v2/pdfs/1082/Sister_Outsider_Essays_and_Speeches_by_Audre_Lorde.pdf

Feminism Is For Everybody by bell hooks

A seminal addition to Third Wave Feminist theory, emphasising the reality that the aim of feminism is to confront and dismantle patriarchal systems which oppress - you guessed it - everybody. This book approaches feminism through the lens of race and capitalism, feeding into the discourse on intersectionality which many of us now take as a central element of 21st Century feminism.

https://excoradfeminisms.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/bell_hooks-feminism_is_for_everybody.pdf

Gender Trouble: Feminism And The Subversion Of Identity by Judith Butler

Butler and her work form probably the single most significant (especially white) contribution to Third Wave Feminism, as well as queer theory. This may be a somewhat dense, academic work, but the primary hurdle is in deconstructing our existing perceptions of gender and identity, which we are certainly better equipped to do today specifically thanks to Butler. Vitally important stuff for dismantling hegemonic patriarchy.

https://selforganizedseminar.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/butler-gender_trouble.pdf

Trans Liberation: Beyond Pink Or Blue by Leslie Feinberg

Feinberg is perhaps the foundational voice in trans theory, best known for Stone Butch Blues, but this text seems like a good point to view hir push into mainstream acceptance where ze previously aligned hirself and trans groups more with gay and lesbian subcultures. A central element here is the accessibility and deconstruction of hegemonic gender and expression, but what this really expresses is a call for solidarity and support among marginalised classes, in a fight for our mutual visibility and survival, in the greatest of Marxist feminist traditions.

The Haraway Reader by Donna Haraway

Haraway is perhaps better known as a post-humanist than a Marxist feminist, but in all honesty, I am not sure these can be disentangled so easily. My highest recommendation is the essay ‘A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century‘, but it is in many ways concerned more with aesthetics and media criticism than anything practical, and Haraway’s engagement with technology has only become more significant, with the proliferation of smartphones and wifi, to understanding our bodies and ourselves as instruments of resistance.

https://monoskop.org/images/5/56/Haraway_Donna_The_Haraway_Reader_2003.pdf

Postcolonialism

~

The Wretched Of The Earth by Frantz Fanon

Perhaps my highest recommendation, this will give you better insight into late stage (postcolonial) capitalism than perhaps anything else. Fanon was a psychologist, and his analyses help us parse the internal workings of both the capitalist and racialised minds. I don’t see this work recommended nearly enough, largely because Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks is a better source for race theory, but The Wretched Of The Earth is the best choice for understanding revolutionary, anti-capitalist, and decolonial ideas.

http://abahlali.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/Frantz-Fanon-The-Wretched-of-the-Earth-1965.pdf

Orientalism by Edward Said

This is probably the best introduction to postcolonial theory, particularly because it focuses on colonial/imperialist abuses in media and art. Said’s later work Culture And Imperialism may actually be a better source for strictly leftist analysis, but this is the groundwork for understanding the field, and will help readers confront and interpret everything from Western military interventionism to racist motifs in Disney films.

https://www.eaford.org/site/assets/files/1631/said_edward1977_orientalism.pdf

Decolonisation Is Not A Metaphor by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang

In direct response to Fanon’s call to decolonise (the mind), Tuck and Yang present a compelling assertion that the abstraction of decolonisation paves the way for settler claims of innocence rather than practical rapatriation of land and rights. The relatively short article centres and problematises ongoing complicity in the agenda of settler-colonial hegemony and the material conditions of indigenous groups in the postcolonial epoch. Important stuff for anti-imperialist work and solidarity.

https://clas.osu.edu/sites/clas.osu.edu/files/Tuck%20and%20Yang%202012%20Decolonization%20is%20not%20a%20metaphor.pdf

The Coloniser And The Colonised by Albert Memmi

Often read in tandem with Fanon, as both are concerned with trauma, violence, and dehumanisation. But further, Memmi addresses both the harm inflicted on the colonised body and the colonisers’ own culture and mind, while also exploring the impetus of practical resistance and dismantling imperialist control structures. This is also of great import to confronting detractors, offering the concrete precedent of Algerian decolonisation.

https://cominsitu.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/albert-memmi-the-colonizer-and-the-colonized-1.pdf

Can The Subaltern Speak? by Gayatri Spivak

This relatively short (though dense) essay will ideally help us to confront the real struggles of many of the most disenfranchised people on earth, removing us from questions of bourgeois wage-slavery and focusing on the right to education and freedom from sexual assault, not to mention the legacy of colonial genocide.

http://abahlali.org/files/Can_the_subaltern_speak.pdf

Wider cultural studies

~

No Logo by Naomi Klein

I have some qualms with Klein, but she nevertheless makes important points regarding the systemic nature of neoliberal global capitalism and hegemony. No Logo addresses consumerism at a macro scale, emphasising the importance of what may be seen as internationalist solidarity and support and calling out corporate scapegoating on consumer markets. I understand that This Changes Everything is perhaps even better for addressing the unreasonable expectations of indefinite and unsustainable growth under capitalist systems, but I haven’t read it and therefore cannot recommend; regardless, this is a good starting point.

https://archive.org/stream/fp_Naomi_Klein-No_Logo/Naomi_Klein-No_Logo_djvu.txt

The Black Atlantic: Modernity And Double Consciousness by Paul Gilroy

This is an important source for understanding the development of diasporic (particularly black) identities in the wake of the Middle Passage between African and America, but more generally as well. This work can be related to parallel phenomena of racialised violence, genocide, and forced migration more widely, but it is especially useful for engaging with the legacy of slavery, the cultural development of blackness, and forms of everyday resistance.

https://dl1.cuni.cz/pluginfile.php/756417/mod_resource/content/1/Gilroy%20Black%20Atlantic.pdf

Imagined Communities: Reflections On The Origin And Spread Of Nationalism by Benedict Anderson

This text is important in understanding the nature of both high colonialism and fascism, perhaps now more than ever. Anderson examines the political manipulation and agenda of cultural production, that is the propagandised, artificial act of nation building. This analyses the development of nation states as the norm of political unity in historiographical terms, as symptomatic of old school European imperialism. Today we may see this reflected in Brexit or MAGA, but lebensraum and zionism are just as evident in the analysis.

https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/jaro2016/SOC757/um/6181696/Benedict_Anderson_Imagined_Communities.pdf

Discipline And Punish: The Birth Of The Prison by Michel Foucault

Honestly, I am not sure if this should be on this list; I would certainly not call it leftist. That said, it is a very important source to inform our perceptions of the nature of institutional power and abuse. It is also unquestionable that many of the pre-eminent left-leaning scholars of the past fifty years have been heavily influenced, willing or not, by Foucault and his post-structuralist ilk. A worthwhile read, especially for queer readers, but take with a liberal (zing!) helping of salt.

https://monoskop.org/images/4/43/Foucault_Michel_Discipline_and_Punish_The_Birth_of_the_Prison_1977_1995.pdf

Trouble In Paradise: From The End Of History To The End Of Capitalism by Slavoj Žižek

Probably just don’t read this, it amounts to self-torture. Okay but seriously, I wanted to include Žižek (perhaps against my better judgement), but he is probably best seen as a lesson in recognising theorists as fallible, requiring our criticism rather than being followed blindly. I like Žižek, but take him as a kind of clown provocateur who may lead us to explore interesting ideas. He makes good points, but he also... Doesn’t... Watch a couple youtube videos and decide if you can stomach him before diving in.

Additional highly recommended authors (with whom I am not familiar enough to give meaningful descriptions or specific recommended texts) (let me know if you find anything of significant value from among these, as I am likely unaware!):

Theodor Adorno (of the Frankfurt School, which also included Herbert Marcuse, Erich Fromm, and Walter Benjamin, all of whom I’d likewise recommend but with whom I have only passing familiarity) was a sociologist and musicologist whose aesthetic analyses are incredibly rich and insightful, and heavily influential on 20th Century Marxist theory.

Sara Ahmed is a significant voice in Third Wave Feminist criticism, engaging with queer theory, postcoloniality, intersectionality, and identity politics, of particular interest to international praxis.

Mikhail Bakhtin was a critic and scholar whose theories on semiotics, language, and literature heavily guided the development of structuralist thought as well as later Marxist philosophy.

Mikhail Bakunin is perhaps the closest thing to anarchist orthodoxy. Consistently involved with revolutionary action, he is known as a staunch critic of Marxist rhetoric, and a seminal influence on anti-authoritarian movements.

Silvia Federici is a Marxist feminist who has contributed significant work regarding women’s unpaid labour and the capitalist subversion of the commons in historiographical contexts.

Mark Fisher was a leftist critic whose writing on music, film, and pop culture was intimately engaged with postmodernity, structuralist thought, and most importantly Marxist aesthetics.

Che Guevara was a major contributor to revolutionary efforts internationally, most notably and successfully in Cuba. His writing is robustly pragmatic as well as eloquent, and offers practical insight to leftist action.

Hồ Chí Minh was a revolutionary communist leader of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, and a significant contributor to revolutionary communist theory and anti-imperialist practice.

C.L.R. James is a significant voice in 20th Century (especially black) Marxist theory, engaging with and criticising Trotskyist principles and the role of ethnic minorities in revolutionary and democratic political movements.

Joel Kovel was a researcher known as the founder of ecosocialism. His work spans a wide array of subjects, but generally tends to return to deconstructing capitalism in its highest stage.

György Lukács was a critic who contributed heavily to the Western Marxism of the Frankfurt School and engaged with aesthetics and traditions of Marx’s philosophical ideology in contrast with Soviet policy of the time.

Rosa Luxemburg was a revolutionary socialist organiser, publisher, and economist, directly engaged in practical leftist activity internationally for a significant part of the early 20th Century.

Mao Zedong was a revolutionary communist, founder and Chairman of the People’s Republic of China, and a prolific contributor to Marxism-Leninism(-Maoism), which he adapted to the material conditions outside the Western imperial core.

Huey P. Newton was the co-founder of the Black Panther Party and a vital force in the spread and accessibility of communist thought and practical internationalism, not to mention black revolutionary tactics.

Léopold Sédar Senghor was a poet-turned-politician who served as Senegal’s first president and established the basis for African socialism. Also central to postcolonial theory, and a leader of the Négritude movement.

***

I hope this list may be useful. (I would also be interested to see the recommendations of others!) Happy reading, comrades. We have nothing to lose but our chains.

#original#leftism#leftist#Marxist#Marxism#socialist#socialism#literature#reading list#critical theory

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Joanna Moorhead

Culture of silencing any challenge to prevailing ideology is damaging academic freedom, says professor

The press release that accompanies Prof Kathleen Stock’s new book says she wants to see a future in which trans rights activists and gender-critical feminists collaborate to achieve some of their political aims. But she concedes that this currently seems fanciful. As far as she is concerned, the book, Material Girls, sets out her stall – and she knows a lot of people will find it distasteful.

Stock, a professor of philosophy at the University of Sussex, says the key question she addresses – itself offensive to many – is this: do trans women count as women?

Whatever else about her views is controversial, she is surely on firm ground when she writes that this question has become surrounded by toxicity. But the problem for her is, at least partly, that many people do anything they can to avoid answering it. “Very few people who are sceptical talk about it directly, because they’re frightened,” she says. “It’s so hard psychologically to say, in reply: ‘I’m afraid not.’”

Stock is at pains to say she is not a transphobe, and also that she is sympathetic to the idea that many people feel they are not in the “right” body. What she says she opposes, though, is the institutionalisation of the idea that gender identity is all that matters – that how you identify automatically confers all the entitlements of that sex. And she believes that increasingly in universities and the wider world, that is a view that cannot be challenged.

“There’s a taboo against saying this, but it’s what I believe,” she says. ��It’s fair enough if people want to disagree with me, but this is what I think.”

That last statement is loaded, too, because the gender identity row is closely linked, especially on university campuses, with freedom of speech. Campuses are a minefield for those wanting to discuss these issues, she says, and she has faced calls for her university to sack her. So she is supportive of the government’s controversial plans for a free speech bill, which critics including English PEN, Article 19 and Index on Censorship have argued will have the opposite effect.

In a joint letter, they argued that the legislation “may have the inverse effect of further limiting what is deemed ‘acceptable’ speech on campus and introducing a chilling effect both on the content of what is taught and the scope of academic research exploration”.

But Stock backs the bill: “I think vice-chancellors and university management groups have shown that they can’t manage the modern problems around suppression of academic freedom. I think there are some genuine instances of unfair treatment of controversial academics, and those academics should be able to seek meaningful redress.”

This week the University of Essex apologised to two professors, Jo Phoenix and Rosa Freedman, after an independent inquiry found the university had breached its free speech duties when their invitations or talks were cancelled after student complaints.

Stock grew up in Montrose, Scotland, the daughter of a philosophy lecturer and a newspaper proofreader, and studied for her degree at Exeter College, Oxford, going on to do an MA at the University of St Andrews and a PhD at Leeds.

Having come out as gay relatively late in life, she now lives in Sussex with her partner and two sons from her previous marriage. She regards her OBE, awarded earlier this year for services to higher education, as a signal that her views have at least some backing in the establishment.

“Academics being online, students being online – it’s introduced a whole new landscape for dealing with controversial ideas, especially when those ideas are controversial within your peer group or a student body. Threats to academic freedom don’t just come from China, or millionaires trying to buy a library wing for your college; they also come from students whipping up a petition within seconds of you saying something and trying to get you fired.”

Sometimes, she claims, it is more insidious than sackings: “For academics [the gender identity debate] has a chilling effect, because academics believe their careers may suffer in ways that are less visible: they don’t get promoted, or they’re removed from an editorial board.” The net result of all this, she says, is an impoverishment of ideas and knowledge, and damage to the dissemination of information.

Because another of Stock’s key arguments in her book is that her own profession, academia, has failed to look in detail at some claims made by trans activists. She questions some of the data that gets shared regarding violence against trans people, saying that a lot of it is produced by groups that adhere to a particular narrative.

“I don’t doubt that transphobic crime occurs, but I want to know to what extent it occurs in a way that could help the trans community better understand the problem it faces.” She’s disappointed, she says, in some fellow academics for not rising above the fray. “I thought the point of philosophy was that you would be able to argue things without resorting to ad hominem attacks – I thought that was the point of our training.”

How, then, in her view, have we got to where we are? Stock takes issue with Stonewall, the LGBTQ+ charity, which campaigns for trans inclusion and opposes the views of gender-critical feminists. The charity’s Diversity Champions programme is very popular on campuses, and Stock believes this has in part “turned universities into trans activist organisations” through their equality, diversity and inclusion departments.

Beyond this, the introduction of student fees has played its part in the current situation, Stock believes. “As soon as students started to pay, they became customers, and universities became much more deferential. They started talking about coproduction of knowledge, giving them much more choice over the whole experience.” The problem with that, she believes, is that “some young people come along with fixed ideas about gender identity theory, and it’s awkward – especially when universities are branding themselves as LGBT-friendly and queer-friendly.”

Philosophy is a vast space, most of it without risk of abuse. So what keeps her in this particular arena? “I was bullied as a child and I think that gave me experience of social ostracisation and toughened me up,” she says. “I’ve also got amazing support. Sure, some philosophers and colleagues are against my views, but others are very supportive.

“Plus it’s personal for me: I’ve struggled with my body in terms of femininity. I could easily aged 15 have decided I was non-binary or even a boy. And I feel very worried for teenagers who are now foreclosing reproductive possibilities and their future, or damaging their bodily tissues in irreversible ways, based on an idea that they may come to relinquish at a later date.”

One tragedy of the gender identity debate is how hate-filled and polarised it has become. Stock says she has suffered online abuse, but makes it clear that she is going to continue to state her case.

Material Girls: Why Reality Matters for Feminism by Kathleen Stock is published by Fleet

#Kathleen Stock#gender critical#material girls#radical feminism#philosophy#radfem safe#was pleasantly surprised to see this in the guardian#although jfc could you walk on egg shells more

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pagan Paths: Reclaiming

Many pagans and witches are also political activists. Pagan values — such as respect for the planet and for non-human forms of life, belief in equality regardless of race or gender, and personal autonomy — often lead people to social or political action. However, as far as I know, there is only one pagan religion that has actually made this social activism one of its core tenets: Reclaiming. Reclaiming combines neopaganism with anarchist principles and social activism.

This post is not meant to be a complete introduction to Reclaiming. Instead, my goal here is to give you a taste of what Reclaiming practitioners believe and do, so you can decide for yourself if further research would be worth your time. In that spirit, I provide book recommendations at the end of this post.

History and Background

Given Reclaiming’s reputation as a social justice-oriented faith, it’s not surprising that it grew out of activist efforts. Reclaiming began with well-known pagan authors Starhawk and Diane Baker, who began teaching classes on modern witchcraft in California in the 1980s. Members of these classes began protesting and doing other activist work together, and this pagan activist group eventually grew into the Reclaiming Collective.

Out of the founders of Reclaiming, Starhawk has probably had the biggest influence on the tradition. Starhawk was initiated into the Feri tradition by its founder Victor Anderson, but had also been trained in Wicca and worked with figures such as Zsuzsanna Budapest (founder of Dianic Wicca). These Feri and Wiccan influences are clear in Starhawk’s books, such as The Spiral Dance, and have also helped shape the Reclaiming tradition.

Like Feri, Reclaiming is an ecstatic tradition that emphasizes the interconnected divinity of all things. Like Eclectic Wicca, Reclaiming is a non-initiatory religion (meaning anyone can join, regardless of training or experience level) with lots of room to customize and personalize your individual practice.

However, to say that Starhawk is the head of the Reclaiming tradition, or even to credit her as its sole founder, would be incorrect. As Reclaiming has grown and spread, it has become increasingly decentralized. Decisions are made by consensus (meaning the group must reach a unanimous decision) in small, individual communities, which author Irisanya Moon calls “cells.” Each cell has its own unique beliefs, practices, and requirements for members, stemming from Reclaiming’s core values (see below). Some of these cells may stick very closely to the kind of paganism Starhawk describes in her books, while others may look very, very different.

As with any other religion, there are times where a governing body is needed to make widespread changes to the system, such as changing core doctrine. When these situations do arise, each individual cell chooses a representative, who in turn serves as a voice for that cell in a gathering with other representatives from other cells. BIRCH (the Broad Intra-Reclaiming Council of Hubs) is an example of this.

At BIRCH meetings, representatives make decisions via consensus, the same way decisions are made in individual cells. While this means changes may take months or even years to be proposed, discussed, modified, and finally passed, it also means that everyone within the tradition is part of the decision-making process.

Core Beliefs and Values

Like Wicca, Reclaiming has very little dogma. Unlike Wicca, the Reclaiming Collective has a public statement of values that clearly and concisely lays out the essentials of what they believe and do. This document, which is called the Principles of Unity, is not very long, so I’m going to lay it out in its entirety here.

This is the most recent version of the Principles of Unity, taken from the Reclaiming Collective website in February 2021:

“The values of the Reclaiming tradition stem from our understanding that the earth is alive and all of life is sacred and interconnected. We see the Goddess as immanent in the earth’s cycles of birth, growth, death, decay and regeneration. Our practice arises from a deep, spiritual commitment to the earth, to healing and to the linking of magic with political action.

Each of us embodies the divine. Our ultimate spiritual authority is within, and we need no other person to interpret the sacred to us. We foster the questioning attitude, and honor intellectual, spiritual and creative freedom.

We are an evolving, dynamic tradition and proudly call ourselves Witches. Our diverse practices and experiences of the divine weave a tapestry of many different threads. We include those who honor Mysterious Ones, Goddesses, and Gods of myriad expressions, genders, and states of being, remembering that mystery goes beyond form. Our community rituals are participatory and ecstatic, celebrating the cycles of the seasons and our lives, and raising energy for personal, collective and earth healing.

We know that everyone can do the life-changing, world-renewing work of magic, the art of changing consciousness at will. We strive to teach and practice in ways that foster personal and collective empowerment, to model shared power and to open leadership roles to all. We make decisions by consensus, and balance individual autonomy with social responsibility.

Our tradition honors the wild, and calls for service to the earth and the community. We work in diverse ways, including nonviolent direct action, for all forms of justice: environmental, social, political, racial, gender and economic. We are an anti-racist tradition that strives to uplift and center BIPOC voices (Black, Indigenous, People of Color). Our feminism includes a radical analysis of power, seeing all systems of oppression as interrelated, rooted in structures of domination and control.

We welcome all genders, all gender histories, all races, all ages and sexual orientations and all those differences of life situation, background, and ability that increase our diversity. We strive to make our public rituals and events accessible and safe. We try to balance the need to be justly compensated for our labor with our commitment to make our work available to people of all economic levels.

All living beings are worthy of respect. All are supported by the sacred elements of air, fire, water and earth. We work to create and sustain communities and cultures that embody our values, that can help to heal the wounds of the earth and her peoples, and that can sustain us and nurture future generations.”

The Principles of Unity were originally written in 1997, to create a sense of cohesion as the Reclaiming Collective grew and diversified. However, the Principles have not remained constant since the 1990s. They have been rewritten multiple times as the Reclaiming tradition has grown and the needs of its members have changed. Like everything else within the tradition, the Principles of Unity are not beyond scrutiny, critical analysis, and reform.

For example, in 2020 the wording of the Principles of Unity was changed to affirm diverse forms of social justice work — including but not limited to non-violent action — and to express a more firm anti-racist attitude that seeks to uplift BIPOC. This was a major change, as the previous version of the document explicitly called for non-violence and included a paraphrased version of the Rede (often called the Wiccan Rede), “Harm none, and do what you will.” This change was made via consensus by BIRCH, after a series of discussions about the meaning of non-violence and the need to make space for other types of activism.

Aside from the Principles of Unity, there are no hard and fast rules for Reclaiming belief. As Irisanya Moon says in her book on the tradition, “There is no typical Reclaiming Witch.”

Important Deities and Spirits

Just as with belief and values, views on deity within Reclaiming are extremely diverse. A member of this tradition might be a monist, a polytheist, a pantheist, an agnostic, or even a nontheist. (Note that nontheism is different from atheism — while atheism typically includes a rejection of religion, nontheism allows for meaningful religious experience without belief in a higher power.)

The Principles of Unity state that the Goddess is immanent in the earth’s cycles. For some, this means that the earth is a manifestation of the Great Goddess, the source of all life. For others, the Goddess is seen as a symbol that represents the interconnected nature of all life, rather than being literally understood as a personified deity. And, of course, there are many, many people whose views fall somewhere in between.

In her book The Spiral Dance, Starhawk points out that the deities we worship function as metaphors, allowing us to connect with that which cannot be comprehended in its entirety. “The symbols and attributes associated with the Goddess… engage us emotionally,” she says. “We know the Goddess is not the moon — but we still thrill to its light glinting through the branches. We know the Goddess is not a woman, but we respond with love as if She were, and so connect emotionally with all the abstract qualities behind the symbol.”

Here’s another quote from The Spiral Dance that sums up this view of deity: “I have spoken of the Goddess as a psychological symbol and also as manifest reality. She is both. She exists, and we create Her.”

In that book, Starhawk proposes a perspective on deity that combines Wiccan and Feri theology. Starhawk’s Goddess encompasses both the Star Goddess worshiped in Feri — God Herself, the divine source of all things — and the Wiccan Goddess — Earth Mother and Queen of the Moon. This Goddess’s consort, known as the God, is similar to the Wiccan God, but includes aspects of Feri deities like the Blue God.

For some, this model of deity is the basis of their practice, while others prefer to use other means to connect with That-Which-Cannot-Be-Known. Someone may consider themselves a part of Reclaiming and be a devotee of Aphrodite, or Thor, or Osiris, or any of countless other personified deities.

Reclaiming Practice

As I said earlier, Reclaiming began with classes in magic theory, and teaching and learning are still important parts of the tradition. The basic, entry-level course that most members of the tradition take is called Elements of Magic. In this class, students explore the five elements — air, fire, water, earth, and spirit — and how these elements relate to different aspects of Reclaiming practice. Though most members of the tradition will take the Elements of Magic class, this is not a requirement.

After completing Elements of Magic, Reclaiming pagans may or may not choose to take other classes, including but not limited to: the Iron Pentacle (mastering the five points of Sex, Pride, Self, Power, and Passion and bringing them into balance), Pearl Pentacle (mastering the points of Love, Law, Knowledge, Liberation/Power, and Wisdom and embodying these qualities in relationships with others), Rites of Passage (a class that focuses on initiation and rewriting your own narrative), and Communities (a class that teaches the skills necessary to work in a community, such as conflict resolution and ritual planning).

If you’ve read my post on the Feri tradition, you probably recognize the Iron and Pearl Pentacles. This is another example of how Feri has influenced Reclaiming.

Another place where the teaching/learning element of Reclaiming shows up is in Witchcamp. Witchcamp is an intensive spiritual retreat, typically held over a period of several days in a natural setting away from cities. (However, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, some covens are now offering virtual Witchcamps). Because each Witchcamp is run by a different coven, with different teachers, there is a lot of variation in what they teach and what kind of work campers do.

Each individual camp has a main theme — some camps keep the same theme every time, while others choose a new theme each year. Some camps are adults-only, while others are family-oriented and welcome parents with children. Typically, campers will have several classes to choose from in the mornings and afternoons, with group rituals in the evenings.

Speaking of ritual, this brings us to another important part of Reclaiming practice: ecstatic ritual. The goal of most Reclaiming rituals is to connect with the divine by achieving a state of ecstasy.

Irisanya Moon says that Reclaiming rituals often use what she calls the “EIEIO” framework: Ecstatic (involving an altered state of consciousness — the transcendent ecstasy of touching the divine), Improvisational (though there may be a basic ritual outline, there is an openness to acting in the spirit of the moment), Ensemble (rituals are held in groups, often with rotating roles), Inspired (taking inspiration from mythology, personal experience, or current events), and Organic (developing naturally, even if that means going off-script). This framework is similar to the rituals Starhawk describes in her writing.

There are no officially recognized holidays in Reclaiming, but many members of the tradition celebrate the Wheel of the Year, similar to Wiccans. The most famous example of this is the annual Spiral Dance ritual held each Samhain in California, with smaller versions observed by covens around the world.

Further Reading

If you are interested in Reclaiming, I recommend starting with the book Reclaiming Witchcraft by Irisanya Moon. This is an excellent, short introduction to the tradition. After that, it’s probably worth checking out some of Starhawk’s work — I recommend starting with The Spiral Dance.

At this point, if you still feel like this is the right path for you, the next step I would recommend is to take the Elements of Magic class. If you live in a big city, it may be offered in-person near you — if not, look around online and see if you can find a virtual version. Accessibility is huge to Reclaiming pagans, and many teachers offer scholarships and price their classes on a sliding scale, so you should be able to find a class no matter what your budget is.

If you can’t find an Elements of Magic class, there is a book called Elements of Magic: Reclaiming Earth, Air, Fire, Water & Spirit, edited by Jane Meredith and Gede Parma, which provides lessons and activities from experienced teachers of the class. Teaching yourself is always going to be more difficult than learning from someone else, but it’s better than nothing!

Resources:

The Spiral Dance by Starhawk

Reclaiming Witchcraft by Irisanya Moon

The Reclaiming Collective website, reclaimingcollective.wordpress.com

cutewitch772 on YouTube (a member of the tradition who has several very informative videos on Reclaiming, told from an insider perspective)

#paganism 101#paganism#pagan#neopagan#reclaiming#reclaiming witchcraft#starhawk#irisanya moon#goddess worship#witchblr#witch#witchcraft#witchy#baby pagan#baby witch#anarchy#activism#environmentalism#long post#my writing#mine

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mj’s Ultimate Political Reading List (that isn’t just crusty russian dudes)

Hello! Today I’m going to give you a list of books that I recommend that revolve around leftist politics!

Malcolm X Speaks by Malcolm X

Women, Culture, and Politics by Angela Davis

Women, Race, & Class by Angela Davis

Freedom is a Constant Struggle by Angela Davis

The Meaning of Freedom by Angela Davis

Abolition Democracy by Angela Davis

Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Davis

The Prison Industrial Complex by Angela Davis

Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde

Gender Trouble by Judith Butler

Performative Acts and Gender Constitution by Judith Butler

Imitation and Gender Insubordination by Judith Butler

Bodies That Matter by Judith Butler

Excitable Speech by Judith Butler

Undoing Gender by Judith Butler

The Souls Of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois

Black Reconstruction In America by W.E.B. Du Bois

Darkwater by W.E.B. Du Bois

This Bridge Called My Back by Cherríe Moraga

Ain’t I A Woman? by Bell Hooks

Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx

Socialism: Utopian and Scientific by Fredrich Engles

Fascism: What is it and How to Fight it by Leon Trotsky

Profit over People by Noam Chomsky

The Accumulation of Capital by Rosa Luxemborg

Reform or Revolution by Rosa Luxemburg

The Conquest of Bread by Peter Kropotkin

Discipline and Punish by Michel Foucault

Black Skins, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon

Orientalism by Edward Said

An Introduction to Marxist Economic Theory by Ernest Mandel

The Affluent Society by John Kenneth Galbraith

The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir

Anarchism and Other Essays by Emma Goldman

Go Tell It On The Mountain by James Baldwin

Black Women, Writing, And Identity by Carole Boyce Davies

Feminism Without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity by Chandra Talpade Mohanty

An End To The Neglect Of The Problems Of The Negro Women by Claudia Jones

Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life Of Black Communist Claudia Jones by Carole Boyce Davies

The Postmodern Condition by Jean François Lyotard

Capitalist Realism by Mark Fisher

Colonize This! by Daisy Hernandez and Bushra Rehman

Socialism Made Easy by James Connolly

Bad Feminist by Roxanne Gay

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander

The Sacred Hoop by Paula Gunn Allen

Black Feminist Thought by Patricia Hill Collins

Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower by Dr. Brittney Cooper

Heavy: An American Memoir by Kiese Laymon

How To Be An Antiracist by Dr. Ibram X. Kendi

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

Me and White Supremacy by Layla F. Saad

So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo

Notes Of A Native Son by James Baldwin

Biased: Uncover in the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do

Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America

The Color of Law: The Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

A Vindication of the Rights of Women by Mary Wollstonecraft

The Socialist Reconstruction of Society by Daniel De Leon

7 Feminist And Gender Theories

The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution

Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color by Andrea J. Ritchie

Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson

Lavender and Red by Emily K. Hobson

Raising Our Hands by Jenna Arnold

Redefining Realness by Janet Mock

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century by Grace Lee Boggs

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America by Ira Katznelson

Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affects Us and What We Can Do

The Common Wind by Julius S. Scott

The End Of Policing by Alex S Vitale

Class, Race, and Marxism by David R. Roediger

Yearning by Bell Hooks

Race, Gender, And Class by Margaret L Anderson

Ezili’s Mirrors: Imagining Black Queer Genders by Omise’eke Natasha Tinsley

Working At The Intersections: A Black Feminist Disability Framework” by Moya Bailey

Theory by Dionne Brand

Dora Santana's Work by Dora Santana

Property by Karl Marx

Wages, Price, and Profit by Karl Marx

Wage-Labor and Capital by Karl Marx

Capital Volume I by Karl Marx

The 1844 Manuscripts by Karl Marx

Synopsis of Capital by Fredrich Engels

The Principals of Communism by Fredrich Engles

Imperialism, The Highest Stage Of Capitalism by Vladmir Lenin

The State And Revolution by Vladmir Lenin

The Revolution Betrayed by Leon Trotsky

On Anarchism by Noam Chomsky

#reading list#leftist#leftism#black leftists#queer leftists#leftist reading list#communism#marxism#socialism#anarchism#communist#marxist#anarchist#socialist#politics#political theory#social justice

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

80 Books White People Need to Read

Here’s my next list! All links are now for Barnes and Noble! If you are interested in finding Black-owned bookstores in your area, check out this website: https://aalbc.com/bookstores/list.php ; I also have additional resources regarding Black-owned bookstores on my Instagram (@books_n_cats) if you are interested! As always, please continue to add books to these lists! ((please circulate this one as much as the LGBT one, these books are incredibly important)).

White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack by Peggy McIntosh

Killing Rage: Ending Racism by bell hooks

Where We Stand: Class Matters by bell hooks

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race by Jesmyn Ward

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander

Rethinking Incarceration: Advocating for Justice That Restores by Dominique DuBois Gilliard

Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women That a Movement Forget by Mikki Kendall

Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces by Radley Balko

Open Season: Legalized Genocide of Colored People by Ben Crump

The Black and the Blue: A Cop Reveals the Crime, Racism, and Injustice in America’s Law Enforcement by Matthew Horace and Ron Harris

From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America by Elizabeth Kai Hinton

Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Y. Davis

They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement by Wesley Lowery

White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide by Carol Anderson

A Promise And A Way of Life: White Antiracist Activism by Becky Thompson

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Robin DiAngelo

Disrupting White Supremacy From Within edited by Jennifer Harvey, Karin Ac. Case and Robin Hawley Gorsline

How to Be an Anti-Racist by Ibram X. Kendi

Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge

Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?: And Other Conversations About Race by Beverly Daniel Tatum

So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo

Uprooting Racism: How White People Can Work for Racial Justice by Paul Kivel

Witnessing Whiteness by Shelly Tochluk

Race Talk and the Conspiracy of Silence: Understanding and Facilitating Difficult Dialogues on Race by Derald Wing Sue

Towards the Other America: Anti-Racist Resources for White People Taking Action for Black Lives Matter by Chris Crass (be advised, this came out in 2015 and is not up to date with current events obviously)

Understanding White Privilege: Creating Pathways to Authentic Relationships Across Race by Frances Kendall

The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identify Politics by George Lipsitz

Waking Up White, and Finding Myself in the Story of Race by Debby Irving

How I Shed My Skin: Unlearning the Racist Lessons of a Southern Childhood by Jim Grimsley

Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi

White Like Me: Reflections on Race from a Privileged Son by Tim Wise

Benign Bigotry: The Psychology of Subtle Prejudice by Kristin J. Anderson

America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America by Jim Wallis

Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We Say and Do by Jennifer L. Eberhardt

Raising White Kids by Jennifer Harvey

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi

The Guide for White Women who Teach Black Boys by Eddie Moore Jr, Ali Michael, and Marguerite Penick-Parks

What White Children Need to Know About Race by Ali Michael

White By Law by Ian Haney Lopez

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

My Soul Is Rested: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement in the Deep South by Howell Raines

Race Matters by Cornel West

American Lynching by Ashraf H.A. Rushdy

Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century by Dorothy Roberts

White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism by Kevin Kruse

This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua

Me and White Supremacy: Combat Racism, Change the World, and Become a Good Ancestor by Layla F. Saad

Racism Without Racists by Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit From Identity Politics by George Lipsitz

Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment by Patricia Hill Collins

When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Inequality in Twentieth-Century America by Ira Katznelson

Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde

Habits of Whiteness: A Pragmatist Reconstruction by Terrance MacMullan

Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower by Brittney Cooper

Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America by Melissa V. Harris-Perry

Heavy: An American Memoir by Kiese Laymon

I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness by Austin Channing Brown

An African American and Latinx History of the United States by Paul Ortiz

Blueprint for Black Power: A Moral, Political, and Economic Imperative for the Twenty-First Century by Amos N. Wilson

The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre, and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood by Tommy J. Curry

Freedom Is A Constant Struggle by Angela Davis

Your Silence Will Not Protect You by Audre Lorde

Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America by James Forman

The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism by Edward E. Baptist

The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, From Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation by Daina Ramey Berry

Slavery by Another Name: The Re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II by Douglas A. Blackmon

The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America by Khalil Gibran Muhammad

The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein

The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit by Thomas J. Sugrue

From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

Give Us the Ballot: The Modern Struggle for Voting Rights in America by Ari Berman

One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression is Destroying our Democracy by Carol Anderson

Antiracism: An Introduction by Alex Zamalin

The Racial Healing Handbook: Practical Activities to Help You Challenge Privilege, Confront Systemic Racism, and Engage in Collective Healing by Anneliese A. Singh

Chokehold: Policing Black Men by Paul Butler

Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul by Eddie S. Glaude

Tears We Cannot Stop: A Sermon to White America by Michael Eric Dyson

Things That Make White People Uncomfortable by Michael Bennett

When They Call You a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir by Patrisse Khan-Cullors

#books#booklr#white privilege#black lives matter#text#nonhp#two more to go after this one!#again please circulate and reblog this one too!#the LGBT list got so much attention#but please pay attention to these books as well#and there's no way this list shows up in any tags#because of the links#so reblogs are very important!!!

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

Personal Project

What is it and why?

It’s a combination of things that have made me realised that working on home and more particularly bedrooms and myself would be interesting. I am going to use my own experience of bedrooms as a way to tell stories:, magical stories, dark and light stories.

I have just finished this book called “the Yellow Wallpaper” that my flatmate has lent me (she is good advice when it comes to books as she’s worked at Glasgow Women’s library) which I highly recommend. I must admit I have really struggled to read. I had to stop after a few pages as it was hard to read: hard to see how this woman trusted her husband’s thoughts about herself more than hers, hard to witness her crave for freedom through mental and physical work -whilst she was advised to rest and do nothing , hard to witness this woman becoming mad, and madness as a last resort against this oppressive, infantilising husband of hers (and brother).

No name woman:

This woman doesn’t have a name, and I think it’s very well done: this isn’t just about her but about all women, them behind the wallpaper, them readers or witness. And so should the woman in my pictures: she shouldn’t have a name, as she could be them all (or part of them).

Bedroom: hate and love

It’s a place of great intimacy and life for most women: birth, sleep, sex, tears, laugh and death. It’s a place, I sometimes seek, and sometimes hate. I wish at times, I could push away the walls of my bedroom to give myself more space for thoughts, more space when I feel constraint in my body, space and time, when I feel limited. Sometimes, I feel the urge of wrecking the place and leave nothing but broken nails and blood.

Other times, magic happens and the place, mostly because of its opening possibilities: windows. I can hear the world from outside and the outside world comes in: that’s a smell from the garden, a cool breeze, night sounds and whispers, a hot summer heat, kids playing in the street, conversation half-heard from afar. Then, my bedroom becomes a handy place to witness without being seen: hidden behind the walls, I pop my head out the window and find out about what’s happening.

Bed

Bed: that’s a place of assault. That’s a place of anger, and frozen body. That’s a place that let me down and it’s strange how I now get to sleep there too.

Bed: that’s a place of death too. I have seen bodies in bed, resting and being looked at. Close relatives, people who’d died slowly in front of my young eyes. Dying, I’ve learnt, doesn’t necessarily take a last breath. It can take years of last breaths, like an upside-down, dark, growing tree inside of your body.

Approach Essay:

Introduction:

With the recent outbreak of the Coronavirus, I have been trying to reorganise my thoughts and change my idea from shooting in a studio, to shooting wherever I’d be allowed to by the government. It also involved a lot of research towards a project that, realistically speaking, would have be to shot at home. While processing the idea of having to stay home for three weeks, I starting thinking about the broad meaning of home myself. When asking my friends and family what home meant to them, I got a large range of answers such as place of intimacy, residence but also social unit, origin. Most of them related their home to family but also mostly pleasant feelings.

With that in mind, I decided to explore different artist’s work, related to the ‘loose’ idea of home. I took the freedom of including not only photographers but also painters and writers ; mostly anyone whose own definition/work on home would somehow echo my own definition. I also kept in mind that shooting a project at home, with less material than usual would be more challenging and require more creativity from me. Therefore, this list of artists does not just include people working around the idea of home, but also artists whose techniques and composition seemed relevant and useful to me in order to help me grow a strong and powerful project.

I) Freedom of space and movement: Exploring techniques in photography

Francesca Woodman (1958-1981). She was an American photographer whose parents were both artists and professors at the Department of Art at the University of Colorado. She was surrounded with Art and artists and starting taking pictures at the age of 13. She also spent her Junior Year in Rome, Italy, where she frequented the Maldoror bookshop-gallery, that specialised in Surrealism. She committed suicide at the age of 22. Her artwork is mostly self-representation, as she explained “It’s a matter of convenience, I’m always available.” As noted by Jui-Ch’ i Liu in her essay on Francesca Woodman’s self-Images (Transforming bodies in the space of Feminity)

“The theme of Elusive Space, absorbed into a nostalgic space, is central to Woodman’s self-representation. [… For example,] in house #3, from her House series, Woodman displays herself in a transformational state. She is curled in a foetal position under a window frame […]. She hides behind the peeling sheets of wallpaper picked up from the pieces of debris scattered on the floor. These effects make her disappear into the wall.” (p.26)

Strangely enough, several specialists have linked Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892) to Woodman’s work. Themes such as madness, physical restriction and woman’s space in the household seem to be central in both artists’ work. The setting of most of the images I looked at were in what seemed to be an abandoned place. Although most pictures seemed to be shot ‘inside’, I felt that somehow, the space itself remained very open and bright (windows, light, fireplace, mirrors), almost ‘breathing’. She uses long-exposure, movement and composition in a very free manner. At times, I couldn’t understand if the picture was taken whilst she was attempting to merge with the house itself or whilst she was hiding herself.

From looking at her pictures, I could sense the need and search of physical but also mental freedom, refusal of constraints in the framing through the choice of space and movement in her shots. It’s also interesting to note that she uses time (for instance in the length of her exposure, time of the day but also investing her own personal time) to explore freedom. The construction of her photographic techniques (long exposure, use of light, props, space, movement and time) invites us not only ‘chase her’ almost physically and mentally (where is the model going? What does she want to say?) but also perhaps to pause and reflect on our own physical and inner boundaries: how do we access the content of the picture both in terms of visibility (elements of the picture we can physically see or not) and understanding (elements of the picture we need to process and analyse in order to understand what she means).

II) Women and home

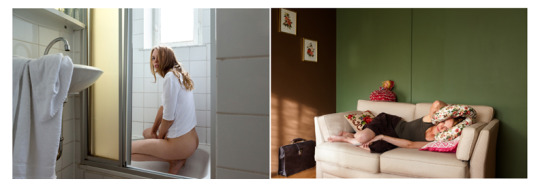

Satu Haavisto (1975 -) and Aino Kannisto (1973 - ). Delicate Demons is a collaborative, ongoing project between two Finnish photographers (Satu Haavisto and Aino Kannisto) who have made a series of photos staging women in domestic spaces. Although the shots are fictional and models play a part, some aspects of the pictures might resonate with most women’s experience of womanhood at different ages and moments in their life. I was impressed at how they’d chosen to depict women in very normal, almost dull and/or ‘embarrassing’ moments of their everyday life: getting dressed, washing the dishes, breastfeeding…

In her article for the British Journal of Photography, Clare Gallagher describes Space in the pictures as:

“[…] tight, with a room corner in most of the scenes, compressing the viewer and the subject into an uncomfortably proximal relationship and emphasising the sense of home as a potentially oppressive place.”

All throughout the series of photos, women always have a strong, intense gaze, expressing what appear to me as anger, sadness, reflection or anxiety.

When describing Woman on the balcony, Clare explains that “her stare out of the frame feels somewhat over-constructed until, with a jolt, we see in a reflection she is in fact gazing directly at the camera. Face on, her look is more vulnerable, more anxious and raw.”

Jo Alison Feiler (1951-): She is an American photographer who was born and successively studied in California at the University of California, at the Art Centre and at the California Institute of Art where she graduated in 1973. Specializing in Gelatine silver prints, she seems to have mostly picked home as a setting to shoot her photos. Most of the prints and photos I have been able to access to are dated back from the mid 70’s and beyond, after she graduated.

Untitled [Two women, two heater vents], 1975

Untitled, 1973

Untitled [Nude below Window]

Untitled [nude between 2 beds],US, 1975

I was impressed with the enigmatic aspect of most of her images: nudes or partially nude models, where you can’t see their face. Body position that are mostly lying on the floor or on diverse surfaces, use of horizontals and lines. Movement, unlike Francesca Woodman is rather static apart from the [two women, two heater vents] and show a position of vulnerability and abandon (both as in letting go and giving up). I was also interested in the way she has used windows as a link to the outside world through what we can see and how the scene is lit. Thanks to the Gelatine Silver Prints, her pictures have a high contrast, which accentuates the tension and dramatic effects of her prints.

III) Light and Cinema

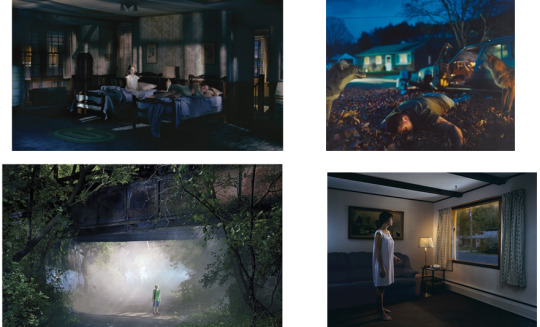

As a great admirer of the Italian painter Caravaggio (1571-1610), and more particularly his dramatic composition and use of the chiaroscuro, I have been delighted to be shown examples of Gregor Crewdson’s photos, which I thought, had a few things in common with Caravaggio’s paintings: the cinematic aspects of it (although when talking about Caravaggio’s paintings, it would be anachronistic), the use of darkness, light and shadows within their frame, the tension in the frame but also the narrative.

American photographer Gregory Crewdson is very likely one of today’s most famous artists specialised in tableaux photography. Crewdson has developed various techniques of lighting throughout long exposure, using a mix of natural lights but also staged lighting (described as “choregraph[ing] lights” by Crewdson in the video). He also mentions his great interest in “tensions [and the] collision between the familiar and the strange” as well as the “unexpected sense of mystery” and a great amount of preparation with his team.

As a conclusion to my Approach Essay, I asked myself a few questions on how to overcome the diverse challenges we are all going through. How can I, in these times of self-isolation and movement restriction, use home and my immediate, every-day life to document but also enable people to relate to my pictures? In this essay, I have chosen a few artists who had been working in similar places and on similar projects. I have also tried to think about challenges that might come up such as lighting a scene and working from home. I believe that I would want to reuse Francesca Woodman’s explorations of time, movement and frame, Satu Haavisto and Aino Kann’s dedication to ‘normal life’, composition and use of space at home to convey feelings, Jo Alison Feiler’s sense of abandon, strangeness and use of windows (especially the Two women, two heater vents picture), and finally Caravaggio’s and Crewdson’s use of daylight and darkness as well as tension in their respective art.

First Sketches

For each picture, I have documented myself on other artists and watched various tutorial videos on how to work with: long shutter speeds, mirrors, taking pictures from the ceiling, effective composition for your photos.

As a plan of action, I have drawn 10 first pictures, that I visually imagined. They are a way for me to start taking pictures, ‘visions’ of what the picture would be. They obviously need to be refined, and I do so by testing out the pictures and working on them. They start as ‘feeling’ ‘intuition’, ‘clear image’, ‘impression’ but always need a lot of work (most of them aren’t easy to realise as there is no limit to what is doable in the real world. A bit like a dream.

Here is a link to my Spark Page where I have decided to continue to develop my project.

https://spark.adobe.com/page/S9C6DpaFNNAVl/

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Four feminist law professors at Harvard Law School have been telling some alarming truths about the tribunals that have been adjudicating collegiate sex for the past five years. Campus Title IX tribunals are “so unfair as to be truly shocking,” Janet Halley, Jeannie Suk Gersen, Elizabeth Bartholet, and Nancy Gertner proclaimed in a jointly authored document titled “Fairness for All Students.” That document followed up on a previous open letter signed by 28 members of the Harvard Law School faculty in 2014 arguing that the updated sexual assault policy recently installed at Harvard was “inconsistent with some of the most basic principles we teach” and “would do more harm than good.”

I recently profiled Gersen and her colleagues in a piece for the Chronicle of Higher Education recounting their effort to defend the “most basic principles we teach” against a movement that is working tirelessly to subvert them. It is significant that they speak from within that movement—the feminist movement—not just because this gives them a margin of credibility within a discourse that tends to assign standing on the basis of identity, but also because their intimate knowledge of the antecedent and ongoing struggles within feminism helps them to understand the intellectual roots of what is happening, and where those ideas are taking us.

Though the four women find themselves opposed to visible tendencies within the movement, no one can doubt their standing within it. They are important theorists and practitioners who have made crucial contributions to historic feminist reforms. They represent a strain of longstanding internal critique that is native to the movement itself. Collectively, they have a stern message about the present course of the movement: As Halley, writing in the Harvard Law Review about a case in which a loud demand for punishment accompanied indifference to the guilt or innocence of the accused put it, “We have to pull back from this brink.”

…

When I spoke with her in her office in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Gertner acknowledged that activists seeking to combat sexual violence had resorted to extreme measures out of a justifiable sense that they were addressing a harm that had been ongoing for decades without remedy. “Exhorting people had not worked, nothing had worked,” she said.