#that no film adaption has ever had queer subtext

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Do you ever see a post that is so next level infuriating it cancels itself out because the op so clearly doesn't know what they are talking about it becomes hilarious, actually?

#this is actually about me for reasons unknown#going through the Frankenstein tag#someone made a post there saying#that no film adaption has ever had queer subtext#WHILE TAGGING THE POST WITH JAMES WHALE'S NAME#for added hilarity they say they hope an actor who I believe is straight#can insert queerness into an upcoming production#again#in a post where James fucking Whale was tagged#like do you live in a weird au version of the world op???#where James Whale - director of the 1931 movie and the super camp and gay Bride of Frankenstein sequal#was somehow not an openly gay man throughout his entire career in film - starting in the 1920s up till his suicide in the 1950s?#like I am sorry it is so deeply funny#that someone doesn't think JAMES WHALE brought queerness to his work

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Master Recs: Horror Cinema!

Do you like Horror films? Yes, you do. Here is a modest selection of 13 cinematic offerings to quench your thirst for seasonal spooks, from lesser-known gems to entertaining schlock and everything in-between. I have good taste and you are welcome.

Renfield (2023), dir. Chris McKay

Renfield rules so hard it hurts, let me tell you. Nicolas Cage as Dracula is already the best selling point imaginable but if you look past the premise, you'll find a heartwarming story about overcoming abuse and codependency, with loads of great action and gore to boot. Good old Nic hams it up to eleven as the Prince of Darkness, channeling the verve of Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee and Lon Cheney all rolled into a deliciously evil sandwich. He's legitimately monstrous and intimidating in a way the character has not been in decades.

It's very effective when he's presented as the abusive "partner" from which Renfield (as in, classic Movie Renfield) is trying to escape. I'm surprised by the lengths the film goes into depicting the emotional trappings of such a relationship - amidst all the funny jokes, that is. It pulls off the unenviable task of being a tonally cohesive Horror comedy, one that leaves no room for doubt as to which moments deserve to be treated seriously or not. Its homage to Golden Age Hollywood cinema and unapologetic queerness are also appreciated.

The House (2022), dir. Emma De Swaef, Niki Lindroth von Bahr, Paloma Baeza, Marc James Roels

The House is a stunning work of stop-motion animation and a solid anthology that explores the existential hang-ups and anxieties of the "Middle Class", crafting solid Horror (and not-so Horror) stories in the process. It has dancing bugs too! I recommend it.

Cocaine Bear (2023), dir. Elizabeth Banks

The last film appearance by the late Ray Liotta. Cocaine Bear is a gruesomely delightful time: a spunky schlock with a killer premise that hooks you up from the start, taking a self-indulgent, humorous sniff at its own status of being "Based on a True Story." This film had the audacity to feature a Wikipedia quote. It's great!

Sweet Home (1989), dir. Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Delightedly, I beheld 1989's Sweet Home, as expertly remastered by Kineko Video. It's a cheesy good time with glorious practical effects and a few, effective low-budget trickeries. I personally give it props for an unexpected Laurel & Hardy's Fra Diavolo reference! This classic is mostly renowned for its videogame adaptation which became a major influence for decades to come.

At the time of writing, the film can be watched on YouTube, making it the most easily accessible entry in this entire column.

Jennifer's Body (2009), dir. Karyn Kusama

It took me this long to finally watch Jennifer's Body, an underrated Horror comedy starring Megan Fox that was unjustly dismissed back in the day. She plays as a literal man-eater, by the way.

There is definitely a lot to enjoy from a modern take on Carmilla whereas the delectably gory blood-feasting works as a backdrop for a toxic high school friendship as well as a commentary on the consequences of sexist exploitation, misogyny and trauma. Save for the occasional slur, it holds up very well.

The Color Out of Space (2019), dir. Richard Stanley

A proper skin-crawler based off the eponymous story by H.P. Lovecraft. Its psychedelic and Stuart Gordon-esque visceral interpretation of the source material is a clever way to circumvent the issue of portraying an "indescribable" alien entity. The Colour, being an unfathomable force outside our science and rationale, serves as a reminder of how insignificant we are in the face of a larger universe we can never hope to comprehend. It works as a metaphor for our atavistic fears.

The film is very much about powerlessness, losing control, losing oneself to the madness or, alternatively, to the realization that nothing was ever "under control." It's Cosmic Horror done right - and also without the racist subtext. Oh, and Nicolas Cage is also in it. I might have buried the lead there.

Gretel and Hansel (2020), dir. Oz Perkins

Here's a scary fairy tale that might have escaped everyone's radar, Gretel and Hansel: a beautifully crafted, meticulously composed film that drenches itself in a disquieting, surreal atmosphere subtly empowered by an alienating soundtrack. It's gripping, to say the least.

The Ritual (2017), dir. David Bruckner

Reviewing and discussing Horror cinema is hard as the truly notable films are best experienced without the burden of knowledge: the viewer should be blindsided by the unknowable terror as much as the characters. That is to say, I can't openly talk about why The Ritual (2017) is great. You should watch it for yourself and get absolutely smack-jawed by the experience.

Society: The Horror (1989), dir. Brian Yuzna

This is unpleasant on an existential level and that, in turn, makes it a really effective Horror. It builds itself as a Kafkian nightmare about the dread of Conformism, feeling out of place in a Society ruled by the white and wealthy, a classic Suburban nightmare scenario. It morphs into an indictment of Capitalism and Classism when the grotesque and revolting third act slimes its way into balls-to-the-wall satire. Bill Warlock (Eddie from Baywatch) puts on the performance of a lifetime as the justifiably paranoid teen protagonist. Shout out to the credited "surreal make-up artist", a man named Screaming Mad George. He did too much of a good job, let me tell you. Needless to say, I recommend this perturbing visual madness with all the content warnings imaginable.

Society waits for you.

Overlord (2018), dir. Julius Avery

I watched Overlord and you should too! It begins as a slickly directed World War II drama before it organically develops into a spectacularly gruesome, intense Action Horror punctuated by a Chef's Kiss of a climax. It gets a special recommendation for the cathartic abuse of nazies! This is the Wolfenstein adaptation you have always wanted.

Willy's Wonderland (2021), dir. Kevin Lewis

Since you can never have enough of Nicolas Cage, here's Willy's Wonderland: a self-aware, genre-flipping, D-grade schlock with the presence of our favourite actor silently and menacingly staring at things - which he does, in spades. The fact that he kills off a bunch of Not-FNAF animatronics is just the icing on the cake! Let me be clear: he does not speak a single word throughout the flick. He's effectively playing "Silent Videogame Protagonist" and his sheer magnetism carries this diegesis to the finish line. A lesser actor would have not been able to pull this off. In all seriousness, Willy's Wonderland works squarely because The Cage was onboard with it. The direction is otherwise unremarkable, the production is even cheaper that one might expect and the rest of the cast is mere fodder. The Cage was its only ace and it played the right hand! That's a whole lot more entertainment value than a film seemingly designed to anger Freddy Fazbear's gooners would realistically deserve. You should watch it if you really want to see Nicolas Cage make sweet love to a pinball machine. Apropos of nothing, did you know that pretentious hack/real life human piss stain Scott Cawthon is a top Republican donor and a pro-lifer? I thought that would be cool information to remember.

The Endless (2017), dir. Justin Benson e Aaron Moorhead

Here's another cosmically disconcerting recommendation for the Lovecraft crowd in the back: if you're looking for a uniquely scary film that deals with the Fear of the Unknown, drowns itself in breath-taking atmosphere and exquisite Uncertainty, I recommend you to watch The Endless. It might knock your existential socks off!

Calamity of a Zombie Girl (2018), dir. Hideaki Iwami

I have kept the "best" for last! Calamity of a Zombie Girl is the weirdest Slasher I have ever seen, mostly due to its inability to keep track of its own genre. It's a B-movie with guts, blood and nudity, a supernatural lesbian romance, a martial arts film and a screwy, goofy comedy all rolled into one cheap-looking animated feature.

The editing is atrocious, constantly abusing the fade-to-black transition without rhyme or reason, the dialogues are inane and contrived, the animation is abysmal (it's a low-budget production by Gonzo, you see) and tonal consistency is downright mythical. In spite of all that, or because of it, the aforementioned bizarre nature of its premise and execution makes it incredibly fun (and funny) to behold, especially when genres collide with each other in relentless, brutal fashion. From the victims' point-of-view (the especially idiotic and ultimately useless extras, I should say) this film plays out like a traditional Slasher flick but from the perspective of the killer, the re-animated zombie girl herself, this is her own action packed Ecchi comedy.

Her first kill occurs as a goof on her part: she shoves a man off like a "dainty dame" and accidentally cracks his skull wide open on a column. Soon after, she rips a guy's arm because he was getting "too friendly" with her and scolds him for his inappropriate behaviour. She then proceeds to have a fight scene with one of the expendable extras because her opponent just happened to be a self-taught Kung Fu master. Also, her undead maid (because of course there's an undead maid) gets kidnapped and she must rescue her! This string of barely held-together nonsense leads to a spectacularly convoluted third act that somehow involves an old abandoned church, a school gym, a game of Anime Sports Ball and a literal Saved by the Bell moment. Did I mention this is all supposed to take place in a non-specific university campus in Japan? Because otherwise you might think the film is happening in two completely different continents! Aside from the immensely idiotic fading transitions, Calamity of a Zombie Girl is hilarious and enjoyable. It's pure, untainted, excellently awful schlock carried to the finish line by the sheer strength of its befuddling ideas. Watch it and tell your friends about it!

Merry Spookmas, you little freaks! --- Follow Madhog on:

YouTube

Twitter

Bluesky

Blogger

Also, here’s a helpful website: https://arab.org/

#madhog thy master#horror#cinema#halloween#spooky season#gore#nicolas cage#anime#master recs#recommendation#calamity of a zombie girl#willy's wonderland#fnaf#the ritual#the color out of space#gretel and hansel#overlord#cocaine bear#the house#the endless#schlock#blood#spooky#society: the horror#baywatch#sweet home#1989#freaks#jennifer's body#renfield

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spoiler alert; the Maltese Falcon is literally a (secretly) gay icon.

So here’s the thing. I’m usually not one for talking about head canons. There’s no way we’ll ever really know why Crowley has the Maltese Falcon alongside his other two “winged statues” (wink wink, nudge nudge) in his flat. But in my little art director heart I really feel like some context could help people think about the historical implications of what the Maltese Falcon might represent for Crowley, and how life often imitates art.

So how is this mysterious black bird (ahem) a symbol of coded queerness in film?

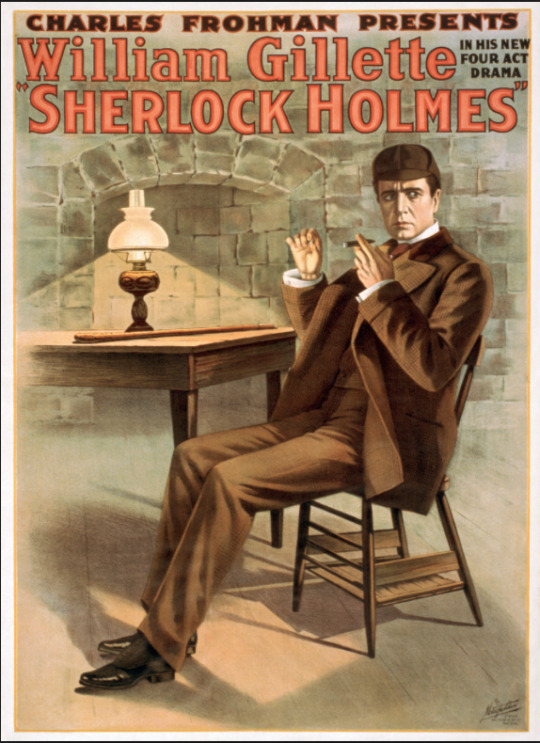

The Maltese Falcon, written & directed by John Huston and released in 1941 (ahem), is an adaptation of Hammett's 1930 novel, which features not one, but three openly gay villains in San Francisco. If you want to adapt this novel in 1940's Hollywood, you had to deal with the Hay's Code,

...A set of moral censorship guidelines for the American filmmaking industry, and was effective in place until 1968. There are several reprehensible facets to the Code, but the one most relevant here is Section 2 – titled simply “Sex” – Item 4: “Sex Perversion, or any inference to it, is forbidden.” While this does not explicitly forbid filmmakers from the use of homosexual characters in a narrative, the implication is transparent enough. Any positive gay representation was clearly made impossible.

Screenflipped (How Subtext Saved (and Damned) Homosexuality on Screen)

The Hays code effectively sublimated all the gay representation in the novel into subtle coded references (sound familiar?) that could be defended if taken out of context, but taken as a whole paint a very erotic gay picture:

Cairo’s calling cards and handkerchiefs are scented with gardenias. He also fusses about his clothes and becomes upset when blood from a scratch ruins his shirt. And if you look carefully, he makes subtle fellating gestures with his cane during his interview with Sam Spade (Bogart)...Some gay critics have also focused on the falcon as a phallic signifier; the way it is treated and touched by various characters.

Emanuel Levy

What's amazing about this is that, despite how coded the references have to be, and how negative the portrayal might be, this is probably "the first example of an explicitly gay-coded villain in American film." Think about it. Crowley loves movies, and in 1941, when the whole world was burning, and the object of his desire is so close for the first time in decades, and yet still so impossibly far away, he could go to a movie theatre and watch gay characters lust after an equally unobtainable Maltese falcon on the silver screen. Who wanted (like him), and were sexual and dark (like him). Who had to sneak around, and make innuendos and use coded signalling and double speak, just to exist.

And even though the hero of The Maltese Flacon finds a perfect straight-laced, alpha male rogue in Humphrey Bogart, "it's undeniable that Bogie was a gay ally -- or as allied as you could get in that era. He frequented gay bars and had close friendships with gay men throughout his life, including Charles Farrell, Spencer Tracey, William Haines, Noel Coward, and even a young Truman Capote (who beat him at arm wrestling)." And just one year later, arguably in his most famous film role, Bogart played another hero in the (also subtly queer coded) film Casablanca, alongside noted bisexual actor Conrad Veidt in his last ever film role before his death.

Veidt played the hero int the first positive gay romance ever featured on film, Different from the Others (1919). It was a SILENT FILM, that's how early it was. Why do I mention Casablanca and Veidt? Take a look at the posters on the wall in the backstage room after the bullet catch in season 2...

Queer history is, albeit quietly, woven into the very fabric of Good Omens. You can't hear it over the noise of the traffic, but it's there.

Why does Crowley have the Maltese Falcon?

My head cannon is that the 1941 Church/Magic Show/Zombie evening (date??) ended badly and Crowley did a geographic to Hollywood where he worked on the film (it would have been in production in 1941) and kept a souvenir.

#good omens 2#good omens meta#art director talks good omens#go season 2#good omens season two#go meta#good omens season 2#good omens#good omens analysis#gay history#queer#queer history#lgbtq history#queerness#queer culture

566 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the main reason I dislike Dracula/Mina being the accepted romance in many Dracula and just plain vampire media is because there's just no backup for it. Like it's so forced. You're telling me that you read Dracula right? And the possible pairing you got out of it was Dracula/Mina??? I mostly blame a century's worth of film adaptations for this.

You can get some mileage out of Dracula/Lucy at least, I think there's a lot of unsaid potential in how Lucy possibly felt; given that I believe she's the perfect parallel to Dracula, and what does it mean that he's turned the good version of himself into a monster? Hatred for the innocent person he never was? Or resentment for what he could’ve been? This is mostly speculation since the og text doesn't go into that kind of direction, but look at what I got just at the idea of them. Dracula/Mina have no depth, no layers and no hints at what they could be going forward had they actually gotten together.

And don't get me started on how much more Dracula/Jonathan have. The beginning of Dracula, with Jonathan's pov trapped the Count's castle, is the best part of the book in my opinion. It's the scariest and most tense section, and is where the queer subtext is at its most hefty. While I won't outwardly state Bram Stoker's sexuality, since there's really no way to know for certainty where his arrow pointed, there's good evidence that he wasn’t straight, and was in great agony about that. I think his internalized homophobia is what gave us that first part of Dracula. And I truly think that Dracula/Jonathan's relationship is both psychosexual and heartbreaking. There's just soo much you can do with the text given. Unlike Dracula/Mina, there's a story here. The struggles that Jonathan went through during his stay were so raw and emotional, him wrestling with both fearing and lusting for Dracula. Jonathan developed a friendship with Dracula on top of that, a friendship that was ultimately betrayed by the monster he was simultaneously repulsed and drawn to. This all culminates in my favorite line in the book (and maybe ever?): "I doubt; I fear; I think strange things which I dare not confess to my own soul."

I mean that line is just so real??? So obvious but so layered?? I'm surprised the British censors didn't burst in nightsticks a-blazin ala Picture of Dorian Gray style.

Jonathan could never understand his feelings around Dracula, he could only cry out against the allure that should be tucked away and hidden if it continues to dare to exist. Jonathan's stay in Count Dracula's castle is the rawest expression of doubt and horror at something society has told him is just as disturbing as a bloodsucking monster. Bram Stoker really showed his hand there. Jonathan discovered something about himself that he didn't understand, and lost a friend in the process. I truly think Dracula/Jonathan should be more recognized because all the pieces are there. But much like Bram Stoker's own take on queerness, movies and adaptations could never show a queer relationship to the people, that would be too much for a vampire film. So instead a constant stream of Dracula adaptations push a romance with the next best option, the man's wife. Despite the fact that there were no interesting ideas or consequences, like Dracula/Lucy, nor any of the sexual or even romantic tension, like Dracula/Jonathan.

Not to mention that Dracula doesn't really have a romance with anyone in the og book, but I get it, romance brings in the people. It's just really annoying that Mina has to be forced into something that just doesn't fit her at all. The fact that it's just widley accepted that the great vampiric romance is Dracula/Mina. Vampires have always been wrapped up in grey morality, queerness, and sex; human monsters. Their appeal is the release of society's barriers, to truly become the monster that everyone said we already were. Dracula/Mina have none of that.

#long post#queer horror#dracula#bram stoker#bram stokers dracula#jonathan harker#mina harker#lucy westenra#dracula x jonathan#dracula x lucy#internalized queerphobia#internalized homophobia#not sure if i got my point across im writing this at 3 am

826 notes

·

View notes

Text

MARCH 30: Nella Larsen (1891-1964)

On this day in 1964, famed author Nella Larsen passed away in her home in Brooklyn. Her most famous novel, Passing (1929), is often considered an early work of lesbian fiction.

Nella Larsen photographed by her friend and patron of the Harlem Renaissance, Carl Van Vechten, on November 23, 1934.

On April 13, Nellie Walker was born in a poor area of Chicago known as the Levee. Her mother was a white immigrant from Denmark and her father was an Afro-Caribbean immigrant hailing from the Danish West Indies, though he died not long after her birth. Her mother, Pederline, soon remarried a fellow white Danish immigrant. Nellie Walker then became Nella Larsen, adopting her stepfather’s surname. The couple had a second daughter and moved to a predominantly white immigrant neighborhood and often encountered discrimination from their neighbors due to Nella’s skin color. As the only black member of her family, critic Darryl Pinckney writes,

“[Larsen] had no entrée into the world of the blues or of the black church. If she could never be white like her mother and sister, neither could she ever be black in quite the same way that Langston Hughes and his characters were black. Hers was a netherworld, unrecognizable historically and too painful to dredge up.”

Nella began her adult life as a nurse, enrolling in school at the Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx. She began by treating elderly black patients at the Lincoln Nursing Home and then later cared for white patients inflicted by the Spanish flu. In 1915, she relocated to the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and eventually became the head nurse. After a few years, however, she became disillusioned with the poor working conditions for nurses and left the profession.

In her second act, Nella became the first black woman to graduate from the NYPL Library School. Stationed as a librarian in Harlem at the onset of the 1920s, she arrived at just the right time to witness the birth of the Harlem Renaissance. She began her writing career in 1925 and became friends with many key figures in the arts community, including photographer Carl Van Vechten. Throughout her life, Nella would publish two novels and one short story: the autobiographical Quicksand (1928), Passing (1929), and “Sanctuary” (1930).

While Nella never had any known relationships with women, her 1929 novel Passing has become a tenet of the lesbian literary canon. Set in Harlem, the novel focuses on the relationship between two childhood friends, Clare and Irene. After losing touch in adulthood, the two are later reunited in a chance encounter only for Irene to discover that Clare has been “passing” as white amongst her wealthy husband’s social circle.

When discussing Passing, scholars often focus on the novel’s homoerotic subtext. Upon their first reunion, Irene is struck by Clare’s beauty and is “drawn to Clare like a moth to a flame.” Throughout the novel, Irene becomes increasingly obsessed with Clare and imagines her to be having an affair with her husband Brian, who himself is coded as queer.

Literary critic Deborah McDowell argues that Irene’s jealousy and delusion is a product of her own “awakening of ... erotic feelings for Clare” and that Passing was an opportunity for Nella to "flirt, if only by suggestion, with the idea of a lesbian relationship.” Overall, many believe that that novel’s central metaphor of “passing” pulls double duty in relation to sexuality as well as race.

A film adaptation of Passing starring Ruth Negga and Tessa Thompson premiered at Sundance in January 2021 and will be released by Netflix later in the year.

#nella larsen#passing#ruth negga#tessa thompson#black lesbian history#lesbian history#lgbt history#gay history#lesbian literature#365daysoflesbians

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something I know no one will ever contend with when they just want to write a hit piece about us, but...

When Moffat said on the A Scandal in Belgravia commentary, “If you watch the show carefully, there’s subtext about John’s drinking,” what did he mean? He wasn’t being flippant, he’s said one of his favorite writers is William Goldman and writers should study him because he “knows everything.” Goldman’s Ten Commandments on Writing say to “put a subtext under every text” and not to be too on the nose.

So what is the “real” subtext to why John drinks, and why does John drink when he’s alone with Sherlock and trying to get him to open up, or otherwise thinking about Sherlock? If the subtext is not about John’s relationship with Sherlock, then like... who else is in the room in those scenes, what’s going on, who is John actually thinking about, and why is it so important to the story that Moffat would include it? What storyline does the subtext of John’s drinking pertain to? It must be pretty big to not have been revealed yet, so it shouldn’t be hard to make a case for.

Similarly: When Moffat and Gatiss say that The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, a movie noteworthy for depicting Holmes as a homosexual in love with Watson, is the inspiration for their adaptation, what do people imagine they adapted from it? Because it wasn’t the characterization, they don’t much resemble the BBC Sherlock characterizations. Barely any plot points were borrowed, and minor ones at that. Why did they pick the big overtly gay adaptation for the basis of their show from a hundred straight alternatives? Why did Gatiss say the thing he liked about it was that Holmes was in love with Watson?

I mean, I know people who hate us will never actually watch it, but the movie is not subtle. The movie isn’t a bunch of gay gags, the movie makes very clear that Holmes is genuinely homosexual and in love with Watson in a deeply painful way that queer people can recognize and relate to, and the same vibe is heavy in series 3 especially. For example, the endings of TSoT and HLV are not gay gags, they are things that happened in the plot and were not presented as remotely funny.

There are two reasonable perspectives on this:

1) It is not especially weird for people who pay attention to what the writers have said about their stories to think all the gay stuff is intentional, and its not weird to have fun chasing down things the writers have taken care to talk about. That’s what fans do, they try to predict where stories are going. No one made hit pieces ridiculing Jon and Daeneyrs shippers because they recognized what the foreshadowing in Game of Thrones was saying, and they were basing it off almost nothing compared to what the showrunners of Sherlock have said and taken care to include in the plot and subtext. People write hit pieces about us because they deeply believe it’s stupid for queer people to think a gay romance could be depicted, we had the misfortune of having a sense of humor about ourselves (calling it a “conspiracy” and ourselves a “cult”), and were enthusiastic about the show and writers whose fandom we’re a part of.

2) The gay stuff is intentional, but all a big joke despite appearances to the contrary. Most of the antis even argued that the gay stuff was intentional, they just thought it was to fuck with people or be provocative. Some of them were even dreading S4, including while it was airing, because they thought we were going to be proven right and we’d be insufferable. If people who hated us worried we could be right, then how delusional could we be?

I can understand someone thinking it all being a big joke is more likely than a TV show depicting a gay romance, but it does not follow that people deserve to be an object of public ridicule because they recognized a bunch of queer allusions and painful queer life experiences that resonated with them and considered that the writers, one of whom is queer and unabashedly obsessed with the works in question, may have positive motives for including those things. It feels like punishing people for doing their due diligence of actually researching the writers’ feelings about things and their influences, rather than just piling on and calling them homophobes. I’m not trying to invalidate anyone’s opinions if that’s how they feel about Moffat and Gatiss nowadays, I’m just saying it’s not some shameful thing for people to actually investigate these things and conclude differently. It’s okay to think writers are talented and clever, and their fandom should be a place where it’s okay to explore that.

What makes me most sad about this is that there is genuinely no area of life where people can just play around anymore without being hunted down. Like, politics is fucking miserable, the pandemic is miserable, I just had a friend kill himself a few months ago because of how bad life is lately, a close relative who I never thought would have suicidal ideation has it now, I have been fighting wanting to die for years, in the U.S. none of us have any idea if we’re ever getting any sort of pandemic stimulus again -- so many of us are suffering immensely right now, it should be okay to be goofy and creative in a fandom without someone deciding its their prerogative to profit off us because they think we’re weird, or whatever.

The reason there’s a lot of crazy meta analysis is because this was supposed to be a relatively safe, creative place where people can try their hand at analyzing stories without being graded or made to feel inadequate, so we treat metas a lot like fanfics where it’s not really appropriate to just rip people’s shit apart no matter how illogical it is, and we find things we like about analysis we don’t agree with in that same spirit: it’s a cool idea anyway, it’s artistically inspiring, it got close to a more compelling idea, etc. I have a big packet of fan mails where several people told me they had been scared and self-conscious to share their thoughts on things, and TJLC helped them open up and inspired them to major in literary or film-related majors. People start somewhere and it’s cruel to make fun of them because they weren’t great at something that doesn’t fucking matter.

FANDOM IS NOT SUPPOSED TO BE A SUPER SERIOUS SPACE. NO ONE PUTS ON A TUXEDO BEFORE THEY LOG IN TO TUMBLR. NO ONE NEEDS SOME OUTSIDER TAKING THE THINGS THEY OFFERED IN THE SPIRIT OF FUN OUT OF CONTEXT TO PRESENT TO A WIDER AUDIENCE THEY DELIBERATELY AVOID BECAUSE THAT AUDIENCE IS MEAN AND SENDS THEM DEATH THREATS AND HOMOPHOBIC AND MISOGYNISTIC SLURS AND SUICIDE ADVICE. IT IS ACTUALLY NOT AN ENORMOUS CHARACTER FAILING TO SHARE BAD ANALYSES OF A TV SHOW, AND SHOULD NOT BE A MATTER OF NATIONAL INTEREST.

But places where people can open up and try things out increasingly can’t exist anymore, because even in a low stakes environment like a fandom there are busybody ghouls who want to profit off being condescending about how people spend their leisure time. It doesn’t add anything to the world except their bank accounts.

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

This reminds me about the difference between queer representation in film and other forms of media. Like, recently When you Finish Saving the World came out and while I didn’t see it myself, I did see that people were saying Ziggy had an ex-boyfriend in the book that I don’t know whether or not it was mentioned in the film adaptation. I wouldn’t be surprised if it wasn’t. I’m thinking of how Simon vs. The Homosapiens Agenda was adapted in to Love, Simon, too. Leah’s characterization is very different in the movie than what it was in the book. It was changed to be less complex and more consumable to heteronormative audiences. Her character motivations shifted from being Simon’s best friend who was hurt that he didn’t come out to her before Abby, to her reaction to Simon being outed as a result of homophobia. Haven’t seen of read it in a hot minute but the point I’m trying to make here is that there is a lot of queer representation in media, it’s just boxed away where the average cis het person can’t find it. So, when we’re represented in places that aren’t strictly in that box (or outside of it, basically anywhere that counts as popular media) everything gets watered down.

Netflix is an important factor to consider in how Stranger Things is allowed to portray its queer characters. I don’t think that they would’ve let season four go any further than it did with queer representation because of a potential loss of viewership. It’s very probable that the Duffers have had to fight with Netflix about what they’re allowed to say and show in their story. Robin is the only explicitly queer character in Stranger Things. Every other character is up to interpretation. People can deny Will being gay, can deny Vickie being bi, because their identities aren’t stated or shown in a way that makes them undeniable to the audience. Will is heavily implied to have romantic feelings about Mike but no one ever says it. Not in the same way that Robin told Steve that she had a crush on a girl when they were high in season three. Vickie is the same. It’s implied that she might have feelings for Robin but never stated. Subtext is the main way that Stranger Things presents its queer characters. But I don’t think that it’s going to stay that way.

The subtext isn’t simple. It’s almost overwhelming complex and is telling an entire story that most people aren’t able to pick up on. The California/Road-trip plot-line in season four is probably the most extreme example of this. I think that the reason that Will is glowing whenever Mike looks at him, and why there’s a hidden confession behind a painting, and references to the rain fight in season three, and an entire plot-line dedicated to Mike and Will’s relationship development is because they weren’t allowed to explicitly tell the audience what was happening with them in season four. But they’re still telling the story they want to tell, just in a different way. I don’t think anyone puts that much effort into something for a plot twist. I think it might be because someone told them no. Robin and Vickie are already pushing what is generally allowed in popular media. They’re two queer characters with very human experiences. That people can relate to whether or not they’re queer themselves. Vickie isn’t as well developed as Robin, but Robin- even though she’s often used as comic relief- is a complex character. She’s a queer character with a potential romantic plot-line and has important relationships with other characters. She’s also heavily implied to be neurodivergent. And she’s not dead.

Stranger Things isn’t perceived as a queer story. It’s at a point where it has complex queer characters but not to the point where it’s been labeled as queer media. If Mike and Will were both explicitly shown to be queer in season four, that would have pushed Stranger Things over the edge. Mike, Will and El are three of the most important characters in Stranger Things. That’s why they had two out of the four plot lines in season four. If Mike and El’s romantic relationship ended, Stranger Things would potentially have more people thinking about whether or not Mike and Will are an actual option, and whether or not Stranger Things is made for a heteronormative audience. This has already started to happen even with Mike and El’s ending the season with the future of their relationship being ambiguous. Even though Robin has a romantic subplot, and Vickie has been introduced, and Will is heavily implied to have romantic feelings for Miek, Stranger Things has not yet been labeled as queer media. I think that has more to do with Netflix than the Duffer brothers.

Queer people aren’t found in film or popular media a whole lot. And more often than not people have to push to be able to have queer characters and representation and relevance to the story. It’s also not uncommon for queer stories to be hidden behind an allegory or in subtext. The story that Stranger Things wants to tell is a queer story, which automatically makes Stranger Things queer media. Being labeled as queer media shoves it away into a hidden box away from anyone who doesn’t want to see it. But, at this point, Stranger Things has become too popular to be shoved into the dark. From the way that everything has been handled with Mike and Will, and Robin and Vickie, it’s clear that they’re trying to tell a queer story. The effort put into Mike and Will in every season shows that while this story is currently still subtextual, it’s something they want to explore and something that they’re not allowed to fully show, but they want to. I remember thinking, who would put this much effort into lighting Will like this? Why would anyone spend this much time on subtext that most people would never notice? And now, I think it’s possible, that they’re trying to tell this story in whatever way they can. And while its still not enough, I don’t think it’s by choice. But I also think that they’re going to tell this story no matter what.

we have 3 queer characters that haven't even kissed anyone of the same gender but the show is full of straight ships that have whole scenes of them making out and holding hands and like I know we will get explicit queerness in s5 but it still feels like I can't expect too much and like I shouldn't hope to have Elmax or Elumax too even if it has semi-romantic subtext in the show but I should be glad if I get the ones we already have even if we will have one season against 4 of straight people being straight and like I just think it's fucked up that I feel like this and I feel like that if the show is not made explicitly queer from the beginning then we should be happy if we get even one queer character... plus all the other queer shows are getting canceled or end up killing one in the couple or they have depressing storylines... it's so fucked up

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feminist, Queer, Playboy, Philanthropist: Why Ironman Belongs to the Shes, Gays, and Theys

Introduction:

This material originally comes from a media critique project I did for an undergrad philosophy course and I've attempted to adapt it into a tumblr post that doesn't make your eyes bleed. I may or may not have been successful. Upfront, I'm giving you a trigger warning for discussion of sexual assault/rape. If you'd like to skip that part of the analysis, mind the red content warning [start/end].

Trix, what are you up to today? Well, I’d like to present an alternative narrative interpretation of the capstone of the MCU. At face value, Tony Stark shows us a wise-cracking, suave, and hyper-masculine superhero. His soundtrack is AC/DC and he arrives on the battlefield in a shower of gold sparks and hydraulics, wearing sunglasses that cost more than my uterus would fetch on the black market. However, this character presents us with so much more than just a hyper-masculine caricature of straight, cis heroism. Not only does he embody typically “feminine” film tropes—such as the hypersexualized “fighting-fucktoy” role, the policing of his body and promiscuity, and the climactic “rape scene” in which his predatory father-figure drugs him and steals his “heart”—additionally, he embodies classically queer film tropes. Unlike most male action-movie protagonists, his story line is an identity crisis at heart, culminating in a climactic “coming out” scene. His character is promiscuous and spurned for it, and camp is a constant underlying theme in his character design as a whole. I explore these themes in two main parts: the femme and the queer. We'll start with the femme.

Hyper-Masculinity & Tony Stark

In order to understand the subversive nature of Tony Stark, we must first establish the typical nature of hyper-masculine and the hyper-feminine character tropes. Before we can ask the question, “how is this character coded as femme?'' We must first ask, “how is this character coded as masc?”. Further, what do these tropes tell the audience about those characters? Ultimately, the hypermasculine caricature lends power to the subject while the hyperfeminine caricature strips the subject of all agency.

Hypermasculinity is defined, generally, as the exaggerated portrayal or the reinforcement of “typically male stereotypes” (typical male meaning, in this context, that of a Westernized man) such as aggression, strength and power (both physcial and otherwise), as well as sex appeal, and integrity. Hypermasculinity takes a keen focus on the physical male form as a dominating force (1). A hypermasculine character, then, would be one that portrays a domineering, powerful man that is above his peers in some way, and is sexually desirable, in that he exemplifies a pornified picture of a male physique. This desirable and desiring caricature of manhood “socializes boys to believe that being a man means being powerful and in control” (2).

In contrast to this idea of hypermasculinity is the media’s typical portrayal of women. The typical hyperfeminine characterization of women in media is that of a passive, pretty, and overtly sexualized side-character with little agency or autonomy within the story. This is true of both blockbuster hits starring men and movies starring women, too. “We had many more interesting characters on screen in the '20s, '30s, '40s than we do now… They could be the femme fatale and then turn around and be the mother and then turn around and be the seductress, and then turn around and be the saint, and we accepted that. They were complex human beings” (2). This is no longer the case for a typical role for women on screen.

The documentary Miss Representation (2) presents a common caricature that a woman in Hollywood might find herself portraying. Action movies with a female lead surely must exhibit agency in their own story lines. However, the female-action-movie-lead is dubbed the “fighting fucktoy” by Miss Representation. Although she makes her own decisions and it is her narrative that drives the story, she primarily exists as eye-candy. Thus, even the “fighting fucktoy” is just that to audiences--a “fucktoy”. She may be “strong” but primarily, she must be pretty. The MCU character Black Widow perfectly exemplifies the “fighting fucktoy”. Her physical strength may be unquestioned, but primarily it is her beauty that is the focus on-screen. Never do we see her fighting in a t-shirt and sweatpants. Even outside of the skin-tight deep-vee catsuit, Black Widow’s plain clothes outfits consist of tight jeans and even tighter shirts.

This is true for both hyperfeminine and hypermasculine stories. Both the men and women starring in mainstream productions are expected to exemplify a western ideal of peak beauty standards at all times. However, where the hypersexualization of male’s bodies is associated with power, dominance, and strength, the sexualization of women’s bodies is linked to submission, frailty, and possession. Hence the name, “fighting fucktoy”. Her beauty does not make her powerful, it makes her a “toy”, an object, a possession. The sexualization of men in media gives them power within their narratives. For women, it does the complete opposite. It makes them objects, even when they are strong. Beauty and sex make them the victims of their own stories. Ultimately, the hypermasculine male character is envied and emulated, not coveted.

Ironman: Femme Fatale

The storyline of the first Iron Man movie is one concerned with bodily autonomy in a way typically reserved for women--Tony Stark is presented as a fighting fucktoy with an unattainable heart. Not only that, he must struggle against the literal policing of his body by friends, family, and government agencies alike. This subversive, unexpected feminine story culminates in the pinnacle “rape scene” wherein a trusted older-male drugs and assaults Tony in order to take advantage of his “body”, the arc-reactor.

Let’s examine Tony’s coded “fighting fucktoy” persona in two parts: the “fighting” and the “fucktoy”. Miss Representation identifies what female leadership often looks like in movies. “When it comes to female leaders in entertainment media, we see the bitchy boss who has sacrificed family and love to make it to where she is” (2). Odd as it may seem, this perfectly encapsulates the metaphorical role of the arc reactor powering the Iron Man suits. First and foremost, the reactor represents Tony Stark’s heart. Not only is it literally located within his heart for the purpose of keeping it intact, it represents his rebirth as a caring, philanthropic man--it encapsulates Stark’s “fight”. Before his kidnapping and the subsequent implanting of the reactor, Stark was every inch the “bitchy boss who has sacrificed family and love” as well as morals themselves in order to be a war profiteer. His “fight” consists of standing up against the same system that had allowed him to amass his fortune. This “fight” is inextricably tied to his “bitchy boss” caricature as someone who has had to surrender love.

It is clear to the viewer that Stark has had to sacrifice love to get where he is in life. Many allusions are given towards the “will they won't they” nature of his relationship with Pepper Potts and Stark’s work is identified as the reason why they won’t. At the end of the movie, Stark attempts to seduce Potts, asking if she ever “thinks about that night” to which she replies, “Are you talking about the night that we danced and went up on the roof, and then you went downstairs to get me a drink, and you left me there, by myself?” The viewers are aware that the reason Stark ran off was because he had received news that Stark weapons had gotten into the wrong hands. Later, Potts will gift him the original arc reactor with the engraving: PROOF THAT TONY STARK HAS A HEART surrounding it. In an unconventional way, Stark portrays the frigid boss who sacrificed everything to get where she is in his titular fight against a war profiteering machine.

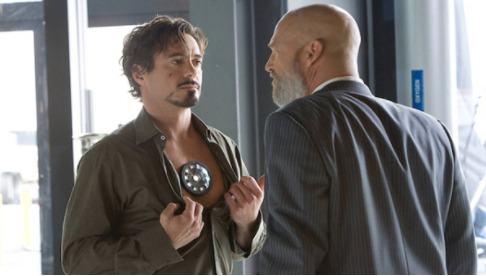

Next, let’s examine his role as the fucktoy. This is a more subtle theme throughout the film, present in body language and subtext. I will focus mainly on scenes which present a femme-coded sexualization--scenes where emphasis on Stark’s body does not lend Stark power, but instead strips him of his autonomy. Take for example the scene pictured below. In this scene, Stark bares his chest to Stane. He is quick to cover up and fruitlessly attempts to redirect Stane’s curiosity. Much like a scene where an attractive woman shows skin, the emphasis is placed on Stark redirecting Stane’s predatory interest. Notice the tension in Stark’s stance, the challenge in his eyes and the contrasting pose of Stane, mid-motion, pushing so close into Stark’s space. Stane is clearly coded as the aggressor once the reactor comes out. The same effect is observed as when a woman bares skin--an apparent loss of autonomy as other characters (and even the cinematography itself) takes a pornographic view of her body. Instead of a powerful male character baring his chest in the heat of a battle, giving the audience a glimpse of corded muscle and strength, this scene leaves the viewer feeling uncomfortable on Stark’s behalf.

[TW Start] This femme-coded sexualization that leads ultimately to a loss of autonomy again rears its head in the titular “rape scene”. This is the clearest instance of the reactor--a literal part of Stark’s body, symbolically present as his heart--lends itself to his victimization. Just as a hypersexualized female character with no bodily autonomy, Stark’s bodily autonomy is forcefully violated so that a powerful male figure in his life can exploit a part of him. This theme becomes horrifyingly clear when the scene is examined up close.

Notice the position of their bodies. Once again, Stane towers over Stark, pressing into his space on all sides. In the first image, to the right, he has an arm draped over the back of the couch--a parody of a romantic or perhaps affectionate gesture from one intimate partner to another. Stane visibly radiates power in this position, even if the viewer were unaware of Stark’s paralyzed state. Stane’s shoulders are squared, even sitting down. The position of the reactor in his hand is relaxed and undeniably taunting. Looking at Stark himself, the horror and powerlessness of his situation is clear. His eyes are open, but almost appear to be unseeing. He is not looking directly at the reactor nor at Stane. In fact, it seems as though his eyes are looking below the reactor and to the room at large. I can only describe his expression as hollow--the blank eyes fixed out to something the viewers cannot see, his mouth partially open, his skin sickly pale.

In the second image, pictured above, Stane leers over Stark’s body, cradling his head in, once again, a parody of a lover’s tenderness. He coaxes Stark’s now limp form down onto the couch, having just paralyzed him with a fictional, technological nerve agent. The horror is shockingly clear on Stark’s face and the perverse joy is just as clear on Stane’s. This scene itself is an undeniable parody of rape, or, at the very least, physical assault. [TW End]

Tony Stark presents us with a clear, femme-coded character as his story line draws upon classicly feminine tropes wherein the sexualization of the character’s body is exploitative at heart and leaves them vulnerable to physical predation. In this way, though he is strong, his “body” makes him the victim of his own story. Not only that, his character arc itself travels from the heart-less profiteer to the philanthropic man with a heart of gold, drawing upon another classically femme-caricature of the “bitchy boss”.

Queer Tropes & The Closet

Queer tropes are much harder to draw upon than that of feminine tropes. Queer tropes in film developed in a time of great censorship and as a result are often subtle. There are three main tropes I would like to reference for the purposes of this critique. Within the Iron Man franchise, there exists a distinct sense of camp, a problematized sexual promiscuity, and, ultimately, an identity-reveal/coming out storyline.

One of the most obvious of these tropes is camp. Camp is “defined as the purposeful and ironic adoption of stylistic elements that would otherwise be considered bad taste. Camp aesthetics are generally extreme, exaggerated and showy and always involve an element of mockery” (3). Camp is present in queer culture most commonly in the ball and drag scenes. Camp is the gaudy, the glitzy, the over-the-top, the classic-but-not, the in-your-face… Camp is all of the above and more. This is why it is so easily recognizable to audiences.

The Advocate identifies a series of seventeen queer caricatures in media for consideration, one of them being that of the “promiscuous queer”. Everyone knows the myth of the promiscuous bisexual, even when the reality is that bisexual individuals are no more or no less likely to view monogamy as “sacrificial” than gay or straight individuals (4). The stereotype of the promiscuous bisexual is inaccurate and harmful, and they are by no meals alone in being labeled overly promiscuous by a general audience. The “promiscuous queer” is defined as a character that may struggle with emotional intimacy and, as a result, sleeps around to mask the love they are missing in their life. “Films going back as far as the ’80s British period piece Another Country have featured gay male characters who use sex to cover for their inability to feel true intimacy with another human being” (5). Among their list of guilty perpetrators are Queer as Folk, The L Word, The Good Wife, and How to Get Away With Murder.

The last trope I’d like to present is that of the “coming out” story. Far from being problematic, the “coming out” is often necessary when telling a queer story. Coming out storylines can be problematized when they are presented as “Big Dark Secrets” that weigh heavily on a person until they are spoken. Ultimately, coming out is a choice. Many queer people choose to come out while many do not. There are many people who fall in between--some people may be comfortable being out to select individuals while not to others or to the world at large. In any case, people can be satisfied and fully fulfilled in any of those choices. Coming out stories are undeniably part of queer culture in media. Consider the recent hit, Love Simon alongside Transparent, Empire, Supergirl, and Glee.

Camp, Secrets & Sex

Through the camp of the Iron Man persona, the problematized sexuality of Stark, and the underlying theme of a “coming out” journey, Tony Stark presents audiences with a classically queer experience in film. Take the Iron Man suit itself. The iconic red and gold, the whine of the repulsors, the sleek metal edges and the furious glow of the arc reactor all scream camp. The red and the gold, the opening bars of Back In Black, the facial hair cut into odd spikes, and the sunglasses do, too. Each and every part of the Iron Man persona is camp. “Stylistic elements that otherwise would be bad taste”... talk about gold-plated biceps and a bright red, glowing chest piece! It's camp, baby!

The problematized sexuality of Stark is harder to see as reminiscent of a queer trope. Take, for example, one of the first scenes in the movie. “I do anything and everything that Mr. Stark requires, including, occasionally, taking out the trash”, Potts remarks in reference to a one-night stand she’s ushering out of Stark’s home. Here, Potts implies that Stark sleeps with “trash”. The following scene gives us the feeling that this is not a one-off occurrence. As Potts enters the room, Stark asks, “how’d she take it?” References to his repeated promiscuity are obvious. “Playboy” is an integral part of his persona. Equally obvious is Potts’ disapproval. Taking these inferences of his playboy lifestyle with what viewers know of Stark’s lack of attachments--his “bitchy boss” exterior, if you may--it appears as though his promiscuity is a symptom of the promiscuous queer stereotype.

“Don’t ever ask me to do anything like that ever again,” Potts says after removing the initial arc reactor model from Stark’s chest cavity. “I don’t have anyone but you,” Stark replies. The viewer has a clear picture of Stark as a playboy type who is truly lonely on the inside--who struggles with emotional intimacy. This struggle is evident, given that Potts, Stark’s secretary and co-worker, is the only person in his life he trusts to assist him in what is essentially open heart surgery. His playboy lifestyle mirrors the circumstances of the promiscuous queer trope in media.

Finally, we come to the last scene of the movie-- the climactic reveal. “I am Iron Man”, Stark says. This scene most clearly illustrates a queer story-line. Stark reveals his “identity”, shedding his last secret, and declares to reporters (and effectively the world) that he is Iron Man. To understand how this scene evokes such a strong sense of queer experience in viewers, I’d like to reference another recent in-universe identity reveal in the Marvel Cinematic canon. In Spiderman: Far From Home, the end-credit scene shows Peter Parker reacting in horror to his identity being leaked via doctored footage from the villain Mysterio. This scene can read as nothing but a deep violation. Even the main characters themselves react in abject horror at the news. The Spiderman identity reveal and the Iron Man identity reveal are two sides of the same coming-out process. In one, the character had full agency. In the other, the reveal was non-consensual, a complete violation. It is clear that both of these scenes draw explicitly upon themes that resonate particularly with queer audiences.

To Infinity(War) and Beyond

Growing up, I latched onto Iron Man and Tony Stark as an outlet for my “otherness”. I was well and truly obsessed with the character for reasons that I could not really put into words. He was weird, he was loud, and he was, frankly, unapologetic about any of it. I remember very clearly on my first day of tenth grade listening to Thunderstruck by AC/DC in the car and putting on the brightest shade of red lipstick I could find. Tony Stark gave me confidence. He gave me a voice. Throughout high-school I must have watched the first Iron Man movie upwards of twenty, maybe even thirty times. It was a comfort to me because it showed experiences I resonated with and it showed a strong character recovering from them. Tony Stark rose from the ashes every time and gave me the strength to rise from my own ashes every time he did.

Our heroes can be anything. And Tony Stark was mine.

#thechestnuthead#here you go#yall asked for it#long post#really fucking long post#meta#trixree speaks#ironman#tony stark#marvel meta#analysis#this took a long time rip#if yall want the full paper you can hit me up for a PDF#my posts#trixree gets meta

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

thots on little women (2019)

or, y’all are giving greta gerwig too much credit, part one

(Before y’all say anything, I know)

I have a lot of thoughts about the new Little Women movie.

I should probably start by saying that I loved the new movie. I thought most of the acting performances were good (Emma Watson’s accent notwithstanding), and it was a pretty faithful adaptation of the book; a lot of the quotes were lifted verbatim from the novel, and I often found myself mouthing along with the actors. I don’t usually like book-to-screen adaptation changes, but I actually didn’t mind most of the changes here. The two biggest things that were changed were the decision to start the story in the middle and jump back and forth, and the positioning Jo as the writer of Little Women who was forced to write in the “Jo marries Bhaer and gets a happy (married) ending” bit. I actually really liked both of those choices and thought they were good additions to the story, making this probably the only time I’ve ever liked any book-to-screen adaptation changes. Also, I am and have been since childhood an Amy March stan, and I liked that her character was more fleshed out and relatable to other viewers. I also think Florence Pugh did a superb acting job. Overall I liked it a lot, and I fully intend on rewatching it again.

I should also say that I read Little Women when I was very young, probably nine or ten, and I loved it, and it has been one of my favorite books since. Regardless of these facts, I never saw any of the live action versions, so the only version I have to compare the 2019 one with is the movie inside my head. With that said, as previously mentioned, I have a lot of thoughts.

Look, the movie was really good. I thought so, my family thought so, and clearly critics thought so too. But when I started reading the reviews after I had seen the movie, something about them kept rubbing me the wrong way. Something kept nagging at me, but it wasn’t until I read this particular review that I realized what it was: “here’s the thing about greta gerwig’s little women. it’s really not just about jo anymore...she showed the struggle and sacrifice and love that meg has. she gives beth one of the most beautiful story arcs ever. she lets beth exist in the movie and grow on us before her death.” But… she didn’t, I remember thinking. And that is the crux of my issue with the movie, or at least, the conversation around the movie. It feels like a lot of people are giving Gerwig credit for things she didn’t actually do, like fully fleshing out the non-Jo characters, or exploring Jo’s sexuality. And that is what I am going to discuss in this essay.

I imagine the Venn Diagram of people who read my first Descendants meta and people who will be interested in this is virtually nonexistent (probably just me, honestly) but just in case, this essay will be set up similarly to my last one. It will probably come in at least two parts, since I can already feel this getting away from me, and I will start with an unnecessarily long list of prefaces:

This meta is not, for the most part, about race. I do believe Greta Gerwig is a White Feminist™, which shows up in a lot of her work, up to and including this one. Obviously the racial diversity of Little Women is virtually nonexistent, but coming from a Greta Gerwig adaptation of Little Women, I’m not sure what y’all were expecting. Since I didn’t go into the movie anticipating any sort of racial diversity, I wasn’t disappointed, and for that reason I will be leaving racial dynamics and Gerwig’s fraught history with racial diversity out of this meta almost entirely.

As previously mentioned, I read Little Women when I was pretty young and loved it. I read it way before I knew anything about the internet or media discussion, so I formed my opinions on the story writ large independently of basically everyone else. With that said, it wasn’t until way later, like about 14 or 15, that I actually started reading online discourse about Little Women and discovered that my opinions ran contrary to just about everyone else’s.

For example, I have always loved Amy March. She was always my favorite character, her chapters of the book were always my favorite to reread, and I was ecstatic when she married Laurie and thought it made perfect sense.

Conversely, I have never been a huge fan of Jo. I know, in the book community that’s basically blasphemy, but whatever. This sense of apathy is probably due to the fact that Jo and I have virtually the same personality, and I get on my own nerves quite often, and also that even as a child I was never a huge fan of Jo’s “not like other girls” personality.

I am what some people would call hyper-romantic. Consequently, my favorite section of the book has always been the last half, with all of the romances and drama. I also didn’t have a huge problem with Jo’s marriage to Bhaer; I didn’t love it or anything, but given that I was never super attached to Jo’s character, I wasn’t super broken up when she married him, also partly because…

I never read Jo as queer. I know, I know, but as a bi woman, I never picked up on whatever subtext everybody else seemed to. I grew up around a lot of white women in the country, and they all acted exactly like Jo did, so maybe that’s why. Of course, it’s a perfectly valid interpretation/headcanon, I’m just telling y’all that I personally never saw it. With that said, I was excited to watch an interpretation where she was more explicitly queer, as all the reviews seemed to say she was, and boy, was I… disappointed.

To clarify, I’m not saying all of my opinions because I want to change anyone’s mind, or convince them that they’ve been reading the book wrong all these years. But I think it’s important to let y’all know where I’m coming from, since I’m sure it’s going to color the way that I view the movie, and the problems within it. In the same way, if my personal opinions about the book change the way you are going to read this essay, I suggest stopping now.

With all that said, I present: Thoughts on Little Women (2019). Also, spoilers, obviously.

Part One: The Sisters

A lot of the praise given to Gerwig’s Little Women centers around one thing: Jo’s sisters. Specifically, how the three sisters are given a much more prominent role in the storyline than in previous adaptations, almost to the level of Jo herself. Now, as previously mentioned, I have never seen another adaptation of Little Women, but I can speak for this adaptation and say that I feel supremely let down.

Let’s start with the obvious: Beth. The review that I cited claimed that Gerwig “gave Beth one of the most beautiful story arcs ever” and “let viewers get to know her so that you really feel her loss.” While of course this reviewer is entitled to their opinion on this movie; all media is up for interpretation, I can’t say that I agree with these statements, or even know where this interpretation came from.

Beth basically only has five major scenes in the film. Obviously she’s a part of many of the other girls’ scenes, but when I’m discussing her “major” scenes, I’m referring to ones where the main focus of the directing is on Beth and her feelings/behaviors. Anyone who read Little Women can tell you that the most memorable thing about Beth is her death. Unfortunately, in the movie, the scenes that deal with her sickness/death are more focused on Jo’s feelings than Beth’s. In the past, Jo mourns her hair with more concern than she shows for Beth, and in the present, the focus continues to be more on Jo’s emotions. Beth’s only actual major scenes are:

Beth is too nervous to talk to Mr. Laurence and hides behind Marmee

Beth is the only one of the March sisters to go visit and take care of the Hummels; she contracts scarlet fever

Beth overcomes her fear of Mr. Laurence and goes to play the piano in his house.

Mr. Laurence gifts Beth a beautiful grand piano; she goes to thank him.

Jo takes Beth to the beach where Beth confesses she is ready to die.

The problem with these scenes is that they tell us basically nothing about Beth’s characteristics. From those five scenes, we can glean that she is selfless, shy, until she isn’t anymore, and that she is a musician, which, contrary to what many musicians believe, is not a personality trait. In actuality, we cannot even concretely say that she is shy, since we only see this behavior through her interactions with Mr. Laurence. She seems to have no problem engaging with the Hummels, and it could just as well be that she is more nervous interacting with a rich older unmarried man, which would not be uncommon for a woman of her situation in her time period.

The only personality trait that differentiates Beth from her sisters is her selflessness, since all three of the other sisters have moments of selfishness that define their characters. But the only time this is ever contrasted with them is when she goes to visit the Hummels, (and then she contracts scarlet fever as a punishment?) One occurrence does not a personality trait make. We know virtually nothing about who Beth is. When viewers see Beth’s sickness and eventual death, they feel sympathy for Jo instead of mourning Beth’s character.

In fairness to Gerwig, much of this is the result of the source material instead of a directing choice. Beth was never given as much focus on Alcott’s Little Women as her sisters. For context, each of the sisters were given “chapters” that focused on their adventures and exploits. Meg has eight, Jo has fourteen, and Amy has ten. Beth has a grand total of five chapters actually centered around her point of view. So it seems obvious that in an adaptation of the source material, Beth would not have been given nearly as much precedence in the narrative.

BUT, and this is a huge but, we knew that Gerwig has no problem changing huge parts of the story she’s telling. This is not a bad thing; as I’ve already mentioned, I think it works to her advantage in many parts of this movie, namely the ending change. So it would not have been out of her scope of abilities or desires to change parts of the source material to flesh out Beth’s character in the same way she fleshed out Jo’s. The fact that she elected not to do that shows that she simply didn’t want to.

Again, this is not a bad thing. Even though it is always presented as a story of four sisters, it is no secret that Jo is the main character of both the book and basically every adaptation. It is no surprise that she is the most developed character because she is essentially the protagonist.

HOWEVER, with all of that knowledge, the thing that irks me about this movie is how the conversations around it has been giving Gerwig so much credit for how developed all of the sisters are when this just isn't true. As it turns out, it is untrue across the cases of all of the sisters.

The next most obvious is Meg. Meg’s case is arguably more egregious than Beth’s, because arc-wise, she is the one who lost the most in the book to screen adaptation. As before, let’s take a look at Meg’s major scenes:

Meg is invited to spend several weeks with her rich friends and she allows them to parade her around and turn her into someone she’s not (even if she wants to be.)

After Laurie sees her in at the party with her friends he judges her, then apologizes, and then they dance and he treats her like a lady.

When the sisters go with Laurie and company to the beach, John Brooke flirts with her, which she reciprocates.

Later on, John volunteers to go with Marmee to take care of Mr. March, and Meg kisses him on the cheek.

Before her wedding to John, Jo asks Meg to run away with her, and Meg responds that “Just because my dreams aren’t as big as yours doesn’t mean they aren’t important.”

Meg’s rich friend Sally convinces her to buy a length of expensive silk to have a dress made.

After purchasing the silk, we see Meg regretful outside her home, and she hugs her twin children.

Meg and John have a conversation about the silk, in which she tells him that she “is so tired of being poor.” When John looks hurt, she apologizes.

John comes to the March household to tell Meg that she should have her dress made. She tells him that she’s already sold it to Sally, and they make up.

Meg definitely has more focused scenes in this movie than Beth does, which makes sense, as she is clearly a more prominent character than Beth is. In the book, Meg has a total of eight focused chapters, to Beth’s five. However, proportionately, the ratio of Meg’s focused scenes to Beth’s is considerably less than the ratio of Meg’s focused chapter’s to Beth’s. This is because for whatever reason, many of the scenes that dealt heavily with Meg’s character, particularly in the second half of the book, were done away with in the movie. Meg’s lifelong dream in both the novel and the movie was to be a wife and mother, and she has an entire arc in the book that centers around that. In the movie, however, it was entirely cut out.

Look. I’m not here to pass judgements on the merits of Meg’s lifelong goal from a feminist perspective. Meg is allowed to have her dream just as Jo is. In the movie, Meg has a wonderful line right before her wedding, when Jo suggests that they run away together. “Just because my dreams are different than yours doesn’t mean they’re less important.” This is a lovely, sentimental, and even feminist take on Meg’s hopes. Desiring to be mother to a man and mother to children is not necessarily a feminist dream, but she is entitled to it just the same. Following that same logic, if you are going to go out of your way to include a line about how Meg and Jo’s dreams are equally important, they should be treated so in the narrative. At the bare minimum, Meg’s arc should be on par with the source material, but it simply isn’t.

In the second half of Little Women, Meg has several focused chapters where she learns to manage a household, comes to terms with being the wife of a poor man, and how to balance having children with having a husband. She has several important discussions with Marmee and with John that are entirely cut from the movie, and we only see her children, Daisy and Demi, twice.

To reiterate, none of this is bad filmmaking, per se. If Greta Gerwig set out to make an adaptation of Little Women that is more focused on centering Jo as the protagonist than the novel, that is perfectly fine. The problem is that Gerwig seems to think she made a more balanced adaptation than the source material, and so does everybody else.

#raetalks#little women#little women (2019)#greta gerwig#meta#saorise ronan#timothee chalamet#emma watson#florence pugh#jo march#amy march#beth march#meg march#eliza scanlen

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Subtext, character arcs, and tragedy in IT Chapter 2

Y’know, I really appreciate the positivity in the Reddie fandom right now when it comes to the likelihood of Eddie reciprocating Richie’s feelings. There IS evidence to suggest he felt the same way in the movies, but like... I gotta be bitter, because it wasn’t enough.

After a long-ass conversation with @skinks about this very bullshit, I tried to make it more meta-ish because I’m still pissed.

(Everything else below the cut because this is long and spoileriffic)

It baffles me that the creators of the film were able to look at the book and see Richie’s queer-coding, but somehow didn’t catch Eddie’s. That they saw the subtext suggesting Richie had feelings for Eddie, but missed the all the subtext suggesting that Eddie returned those feelings. Or, that they DID pick up on all of that, but chose to cut it because... why? I genuinely don’t understand why.

Eddie’s arc in Chapter 2 only makes sense when divorced from the rest of the text - not just the rest of Chapter 2, but from the book and from Chapter 1 as well. Book!Eddie was repressed, but not cowardly. His inner conflict revolved around his fear of himself, that there was something rotten and diseased in him, which was only exacerbated by his mother’s Munchhausen-by-proxy. But he was always ready to go all-out for his friends, and he did. The thing that got him in the end was a shaky belief in himself and his own power, not an inability to act despite his fear.

And Chapter 1!Eddie was a scrapper. He was still afraid of disease, etc., but he was always ready to fight, to help, to throw the fuck down to protect himself and his friends.

Who the fuck is Eddie in Chapter 2? You could argue that because he forgot who he was with the Losers, he buried the brave part of himself, but no, they go out of their way to show that he was always like this, the cowardice thing goes back to when he was a kid. Like, where the hell did that come from?

It makes sense as a self-contained thing, if you look at it as the writer/director trying to make his death feel like the conclusion of a character arc, rather than an abrupt tragedy as it was in the book & miniseries. I think that was what happened, honestly. But in the context of the wider text, it doesn’t fucking work. That wasn’t the Eddie King wrote and it wasn’t the Eddie they wrote in Chapter 1. Moreover, considering Eddie’s queer-coding and the tension between him and Richie... why choose that as your arc?

If you’re going to go all-out and canonize Richie being queer and having feelings for Eddie... why stop there? Why leave Eddie’s reciprocal feelings as subtext? Why not expand on what you already had, i.e. Eddie’s fear of disease - make it clear that it’s a metaphor for his fear of being broken/rotten/wrong inside, make it clear what that metaphor implies? Have him realize by the end that he’s not broken, there’s nothing wrong with him, that he’s loved, he’s IN love, and he’s willing to fight to keep it?

Hell, to be perfectly honest, I’ve never liked Eddie’s death, either as a fan of his character or narratively. As I said, it’s abrupt in the book and miniseries - it makes sense for his character, but only because his character is pretty static throughout the story. He lives repressed and miserable and dies repressed and miserable, only ever getting to glimpse who he might’ve been otherwise. Eddie is a rich, wonderful character, but a tragic one with no real arc. Some people like that, but I personally hate it.

I appreciate Muschietti & co. trying to give him an arc, but I just... wish that they had done so by expanding on who he was in the text, or the version of him that they wrote. I wish they had given him a storyline that made sense for the character, rather than re-writing his character to make sense with the ending. They already changed a LOT for this adaptation, why not change that?

And like, ultimately, canonizing Richie’s feelings and having Eddie die is just... hopeless. It doesn’t gel with the story’s overall theme of love overcoming hatred, fear, and bigotry. It works if Eddie’s story is meant to be a tragedy through-and-through, the story of a queer man who could never bring himself to admit and be happy with who he was - you get the idea that if he had been, he might’ve lived. It’s upsetting, but it works. But if his story is one of overcoming his cowardice, then that element is lost - his death is sad, but he died bravely, so his arc (as per Chapter 2) is complete. Because of this, suddenly the tragedy of his death is all about Richie losing the love of his life, in direct parallel to Adrian’s boyfriend Don, who lost his. But if that’s the story, then what are we meant to get from it? Being out didn’t save Don from heartbreak, and being closeted didn’t save Richie. And because Eddie’s queerness and feelings for Richie remain all subtext (and let’s be honest guys, it’s pretty meager subtext compared to what we get in the book & even the miniseries), we don’t even know whether Richie had a shot at happiness with him in the first place! If Eddie had lived, we don’t know that he and Richie would’ve been together. We don’t even know whether Eddie would’ve been hypothetically interested. He’s completely decentralized from his own story, because at the end of the day, what Eddie wanted and what Eddie felt for Richie isn’t treated like it matters. His death is about Richie’s grief and Richie being alone - out or on his way out of the closet, perhaps, but lonely and bereaved. It has nothing to do with Eddie anymore, and it’s hopeless and dissatisfying through-and-through.

Normally I’m iffy on characters being spared or killed in adaptations, when that’s not what happened to them in the source material. It can work, but usually I feel like it weakens the story. In this case, I think that saving Eddie would’ve strengthened the story. But if saving him wasn’t in the cards, the least - the very least - they could’ve done was give him a better arc, and canonize his coding the way they did for Richie. Without that, his story falls so, so tragically flat.

#it chapter 2 spoilers#it 2 spoilers#it chapter 2 meta#reddie meta#eddie kaspbrak#eddie kaspbrak meta#I am... sALTY

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

here’s the introductory essay I wrote about Can You Ever Forgive Me?

Gay people on screen have existed almost as long as movies themselves. But, because of what was deemed socially acceptable, and because of the Hays code that lasted from 1930 to 1968, gay characters could not be fully, canonically incorporated into the stories that were being told on screen.