#teatro carlo felice

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

youtube

Luke Howard / Hera Hyesang Park : While You Live (Breathe 2024)

The album Breathe, released under the prestigious Deutsche Grammophon label, presents "While You Live," a collaboration between pianist and composer Luke Howard and South Korean soprano Hera Hyesang Park. This piece achieves a delicate balance between Howard’s modern minimalism and the emotional intensity that defines Park’s vocal interpretation. From the opening chords, the work evokes an introspective soundscape, with a piano flowing like a river under a melodic mist. Park joins with a voice that seems to emerge from the depths of the soul, infusing each phrase with a moving vulnerability.

Howard’s composition stands out for its deceptive simplicity. The piano moves in a hypnotic loop, creating a minimalist structure that allows Park’s voice to shine in the foreground. The text, seemingly loaded with existential contemplation, finds an ideal vehicle for emotional resonance in her vocal performance. Hera Hyesang Park uses her impeccable technique to express not only the beauty of the words but also the despair and hope that seem to pulse within them. The production by Deutsche Grammophon highlights every detail with crystalline clarity, creating an immersive experience.

"While You Live" is, in essence, an intimate dialogue between voice and piano, managing to transcend genres and traditions. Howard and Park have created a piece that is both deeply personal and universally resonant, a testament to the fragility and beauty of life itself.

#youtube#luke howard#hera hyesang park#while you live#deutsche grammophon#Breathe#orchestra del teatro carlo felice

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scoperte ed eventi dublinesi legati alla vita e al genio di Oscar Wilde

Suggerimenti per una visita dublinese legata a uno dei cittadini dublinesi più famosi nel 125° anniversario della sua morte

Suggerimenti per una visita dublinese legata a uno dei cittadini dublinesi più famosi nel 125° anniversario della sua morte Nel 2025 si commemora il 125° anniversario della morte di Oscar Wilde, uno dei numerosi autori irlandesi che si contendono la scena dei più grandi scrittori di tutti i tempi. E tra i motivi per visitare l’Irlanda quest’anno ci saranno anche le iniziative dedicate a Wilde.…

#125° anniversario Wilde#Alessandria today#Arts Over Borders#Book of Kells#Cultura irlandese#De Profundis#Dublin Literary Pub Crawl#Dublin Shelbourne Hotel#Dublino#Enniskillen#eventi Oscar Wilde 2025#Fermanagh Irlanda#festival In Our Dreams#festival Oscariana#Google News#Happy Days Enniskillen#High Street Enniskillen#Il principe felice#Irlanda del Nord#italianewsmedia.com#letteratura inglese#MoLI Dublino#mostre Oscar Wilde#opere teatrali Wilde#Oscar Wilde#Oscar Wilde teatro.#patrimonio culturale#Pier Carlo Lava#Polo letterario Wilde#progetti Arts Over Borders

0 notes

Text

Opera on YouTube 5

Nabucco

Teatro alla Scala, 1987 (Renato Bruson, Ghena Dimitrova; conducted by Riccardo Muti; no subtitles)

Teatro di San Carlo, 1997 (Renato Bruson, Lauren Flanigan; conducted by Paolo Carognani; no subtitles)

Ankara State Opera, 2006 (Eralp Kıyıcı, Nilgün Akkerman; conducted by Sunay Muratov; no subtitles)

St. Margarethen Opera Festival, 2007 (Igor Morosow, Gabriella Morigi; conducted by Ernst Märzendorfer; English subtitles)

Rome Opera, 2011 (Leo Nucci, Csilla Boross; conducted by Riccardo Muti; English and German subtitles)

Teatro Comunale di Bologna, 2013 (Vladimir Stoyanov, Anna Pirozzi; conducted by Michele Mariotti; Italian subtitles)

Rome Opera, 2013 (Luca Salsi, Tatiana Serjan; conducted by Riccardo Muti; no subtitles)

Gran Teatro Nacional, Perú, 2015 (Giuseppe Altomare, Rachele Stanisci; conducted by Fernando Valcárcel; Spanish subtitles)

Metropolitan Opera, 2017 (Plácido Domingo, Liudmyla Monastyrska; conducted by James Levine; Spanish subtitles)

Arena di Verona, 2017 (George Gagnidze, Susanna Branchini; conducted by Daniel Oren; English subtitles)

La Cenerentola (Cinderella)

Jean-Pierre Ponnelle studio film, 1981 (Frederica von Stade, Francisco Araiza, Paolo Montarsolo; conducted by Claudio Abbado; English subtitles)

Glyndebourne Festival Opera, 1983 (Kathleen Kuhlmann, Laurence Dale, Claudio Desderi; conducted by Donato Renzetti; no subtitles)

Salzburg Festival, 1988 (Ann Murray, Francisco Araiza, Walter Berry; conducted by Riccardo Chailly; English subtitles)

Tokyo Bunka Kaikan, 1991 (Lucia Valentini-Terrani, Toshiro Gorobe, Domenico Trimarchi; conducted by Antonello Allemandi; Japanese subtitles) – Act I, Act II

Houston Grand Opera, 1995 (Cecilia Bartoli, Raúl Giménez, Enzo Dara; conducted by Bruno Campanella; no subtitles)

Rossini Opera Festival, 2000 (Sonia Ganassi, Juan Diego Flórez, Bruno Praticó; conducted by Carlo Rizzi; Italian subtitles)

Gran Teatre del Liceu, 2008 (Joyce DiDonato, Juan Diego Flórez, Bruno de Simone; conducted by Patrick Summers; German subtitles)

Romeo Opera, 2015 (Serena Malfi, Juan Francisco Gatell, Alessandro Corbelli; conducted by Alejo Pérez; Italian and English subtitles)

Lille Opera, 2016 (Emily Fons, Taylor Stayton, Renato Girolami; conducted by Yves Parmentier; English subtitles)

Boboli Gardens, Florence, 2020 (Svetlina Stoyanova, Josh Lovell, Daniel Miroslaw; conducted by Sándor Károlyi; no subtitles)

Lucia di Lammermoor

Tokyo Bunka Kaikan, 1967 (Renata Scotto, Carlo Bergonzi; conducted by Bruno Bartoletti; English subtitles)

Mario Lanfranchi film, 1971 (Anna Moffo, Lajos Kosma; conducted by Carlo Felice Cillario; English subtitles)

Bregenz Festival, 1982 (Katia Ricciarelli, José Carreras; conducted by Lamberto Gardelli; no subtitles) – Part I, Part II

Opera Australia, 1986 (Joan Sutherland, Richard Greager; conducted by Richard Bonynge; English subtitles)

Teatro Carlo Felice, 2003 (Stefania Bonfadelli, Marcelo Álvarez; conducted by Patrick Fournillier; Japanese subtitles)

San Francisco Opera, 2009 (Natalie Dessay, Giuseppe Filianoti; conducted by Jean-Yves Ossonce; English subtitles)

Amarillo Opera, 2013 (Hanan Alattar, Eric Barry; conducted by Michael Ching; English subtitles)

Gran Teatre del Liceu, 2015 (Elena Mosuc, Juan Diego Flórez; conducted by Marco Armiliato; French subtitles)

Teatro Real de Madrid, 2018 (Lisette Oropesa, Javier Camerana; conducted by Daniel Oren; English subtitles)

Vienna State Opera, 2022 (Lisette Oropesa, Benjamin Bernheim; conducted by Evelino Pidó; English subtitles)

Il Trovatore

Claudio Fino studio film, 1957 (Mario del Monaco, Leyla Gencer, Fedora Barbieri, Ettore Bastianini; conducted by Fernando Previtali; English subtitles)

Wolfgang Nagel studio film, 1975 (Franco Bonisolli, Raina Kabaivanska, Viorica Cortez, Giorgio Zancanaro; conducted by Bruno Bartoletti; Japanese subtitles)

Vienna State Opera, 1978 (Plácido Domingo, Raina Kabaivanska, Fiorenza Cossotto, Piero Cappuccilli; conducted by Herbert von Karajan; no subtitles)

Opera Australia, 1983 (Kenneth Collins, Joan Sutherland, Lauris Elms, Jonathan Summers; conducted by Richard Bonynge, English subtitles)

Metropolitan Opera, 1988 (Luciano Pavarotti, Eva Marton, Dolora Zajick, Sherrill Milnes; conducted by James Levine; no subtitles)

Bavarian State Opera, 2013 (Jonas Kaufmann, Anja Harteros, Elena Manistinta, Alexey Markov; conducted by Paolo Carignani; English subtitles)

Temporada Lirica a Coruña, 2015 (Gregory Kunde, Angela Meade, Marianne Cornetti, Juan Jesús Rodriguez; conducted by Keri-Lynn Wilson; no subtitles)

Opéra Royal de Wallonie-Liége, 2018 (Fabio Sartori, Yolanda Auyanet, Violeta Urmana, Mario Cassi; conducted by Daniel Oren; French subtitles)

Arena di Verona, 2019 (Yusif Eyvazov, Anna Netrebko, Dolora Zajick, Luca Salsi; conducted by Pier Giorgio Morandi; German subtitles)

Teatro Verdi di Pisa, 2021 (Murat Karahan, Carolina López Moreno, Victória Pitts, Cesar Méndez; conducted by Marco Guidarini; no subtitles)

#opera#youtube#complete performances#nabucco#la cenerentola#lucia di lammermoor#il trovatore#giuseppe verdi#gioachino rossini#gaetano donizetti

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

A great big Thank You goes to Pietro Bellantone, Presidente delle Associazioni EventidAmare!

Teatro Carlo Felice, l'evento "Genova nel Mondo e il Mondo a Genova" 21 giugno, 2022. Si è trattato di una iniziativa di networking, cultura e spettacolo, curata dal Corpo Consolare di Genova (articolato in 54 Consolati Generali ed Onorari che operano in Liguria) e tesa alla promozione dell'immagine della Città di Genova nel Mondo.

#moderndance#performer#stageperformance#IG_LIGURIA#spectacle#liguriagram#liguria_more_than_this#performance#genovamorethanthis#Genova#Genoa#dance#Italy#SouthAmerica#traditionaldance#picoftheday#genovacity#genovagram

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Verdi - Aida - Ritorna vincitor! - Celestina Boninsegna (Edison, 1911)

Boninsegna was born into a musical and financially comfortable family on 26 February 1877 and, by the age of fifteen was pursuing a course of musical studies at the Pesaro Liceo. She had just finished singing Norina in Don Pasquale at Reggio Emilia’s Teatro Ariosto and her reception was so encouraging that her parents decided, on the advice of several professional musicians, to afford her the formal training that her obvious talent deserved. The Liceo at that time was directed by Pietro Mascagni, who took an immediate interest in Boninsegna, and who, as we shall see, would have a profound influence on her career. On 29 February 1896 she sang in Rossini’s Piccola Messa Sollene at the Liceo with Fiorello Giraud and, a week later, with Alessandro Bonci. Her graduation lesson, on 12 August 1896, drew the following appraisal: “Boninsegna possesses a dramatic soprano voice and sings with great discipline and expression. The voice is of extraordinary equalization”. The next night, under Mascagni’s direction, she gave a recital at the Salon of the Liceo to a sold out house. Diploma in hand, she secured a contract at Fano, and on 25 December, our ‘dramatic soprano’ debuted as Gilda in Rigoletto. The reviewer noted that “Boninsegna, who is just beginning her career, warrants encouragement”. The Teatro Piccinni of Bari presented her as Marguerite in Faust on 28 January 1897 and the chronicle of that theatre declared her performance “excellent”.

Another year of study finally allowed her to make that to which she referred as her ‘official’ debut at the Comunale of Piacenza in December, 1899 as Goldmark’s Queen of Sheba , conducted by Bandini. She then appeared in Lohengrin and, near season’s end, in Yanko by Bandini. His opera proved to be less than successful and was replaced with further performances of Lohengrin. She was immediately engaged by the Dal Verme of Milan for Il Trovatore and Ruy Blas and after a summer vacation returned for Ernani and Petrella’s Ione. The year ended at Cremona with Ruy Blas and Faust.

On 17 January 1901, she opened the season at Rome’s Teatro Costanzi in one of the seven concurrent World Premières of Mascagni’s Le Maschere. The other theatres chosen were Milan’s La Scala, Turin’s Regio, Verona’s Filarmonico, Genoa’s Carlo Felice, Venice’s Fenice and Naples’s San Carlo, which delayed its opening by two nights because of the tenor’s indisposition. Mascagni chose to conduct at Rome and it was at that theatre alone that the opera was successful. Boninsegna sang all twenty performances at the Costanzi, and on the last evening, 24 March, in an on stage ceremony she was fêted to a shower of gifts and affectionate speeches by members of the ensemble. She returned in April to the Dal Verme for Il Trovatore, and after a brief vacation, embarked on her first tour to South America.

Boninsegna arrived in Chile several weeks into the opera season and debuted at Santiago’s Teatro Muncipal as Elvira in Ernani on 20 July. El Mercurio immediately hailed her as the “trump card” in the company’s deck. The newspaper’s critic went on to say:

La Señora Boninsegna is the most sympathetic soprano to have sung here in the last several years. She has an agreeable presence, a fresh voice, sweet in tone and naturally trained. The notes are pure and crystalline and the singing is without affectation. In sum, la Señora Boninsegna is a dramatic soprano of the first rank.

El Mercurio – 8 September – La Gioconda – Boninsegna sang with great sentiment, inspiration, profoundly felt artistry and with a most beautiful voice.

The Mefistofele premiere was a disaster for the tenor, Alfredo Braglia. “Open your eyes, Braglia”. “Learn to sing, Braglia” and “Follow the soprano, Braglia” were hurled at him from every section of the theatre. La Opera in Chile states that Boninsegna’s Margherita and Elena, on the other hand, were the objects of “rhapsodies” and “poetic adjectives” in the press.

On the evening of her Tosca, with Chile’s president in the audience, she and Giraud were asked to sing the National Anthem. The next day, newspapers recorded that they had sung it in “Perfecto Castellano, which we will remember with great affection”. She closed the season at Santiago with Cavalleria Rusticana and at Valparaiso, she sang an “exquisitely limpid Margherita”, a “superb Aida”, and a “triumphant La Gioconda”.

Several of Boninsegna’s Chilean reviews were telegraphed to Milan and in the course of reading them, the Director of Trieste’s Teatro Verdi observed that she had sung in La Juive and that she had received outstanding notices. The theatre was in the midst of preparing the opera, and he decided that it was she whom he wanted for the production. On 25 January 1902, L’Independente stated that Boninsegna “sang a truly lovely and heartfelt Rachel” in the company of Francesco Signorini and Luigi Nicoletti-Korman. After performances of Aida at Trieste, she returned to Chile, where, on 14 June she opened the Santiago season as ‘Aida’ to her usual superlative reviews. She added several operas to her repertoire, including ‘Lautaro’, a new Chilean work, which was severely protested by both press and public. El Mercurio: ‘even the talents of Celestina Boninsegna could not salvage this derivative miscalculation. Senor Ortiz’s opera is an insult to the intelligence of the audience’. The season included visits to Chillan, Talca and Valparaiso.

On Christmas Eve, she debuted at Parma’s Teatro Regio in a new Verdi role, Elena, in ‘I Vespri Siciliani’, and later, she sang the ‘Il Trovatore’ Leonora. Another debut in late January found her at Modena’s Comunale for Aida and Mefistofele, then at Bari, which would be the scene of her greatest failure. On 18 March she debuted in Il Trovatore. Giovine’s Il Teatro Petruzzelli di Bari states “Boninsegna was well applauded for ‘Tacea la notte placida’, but, after the second performance, Aida, Alloro was called in to substitute for Boninsegna, who was unprepared in the role”. I believe that it is from this engagement that a great deal of interesting, but inaccurate information about her has flowed. She took a well-needed break, and on 26 May, returned to the Dal Verme for Il Trovatore, where, she had a much better time of it, appearing seven times with Margherita Julia, Antonio Paoli and Vincenzo Ardito. In November, at Modena, she sang the first Normas of her career, and five months later, at Trieste, the last, according to any evidence that we have.

On 18 October, Boninsegna debuted as Aida at Covent Garden with the Naples San Carlo company. The cast included Eleanora de Cisneros, Francisco Viñas and Pasquale Amato. She had a fine success, and on the 26th she appeared in Un Ballo in Maschera with de Cisneros, Emma Trentini, Viñas and Mario Sammarco. The Times called it a “sterling revival”.

A debut at La Scala now waited. On 18 December, she opened the season as Aida with Virginia Guerrini, de Marchi, Stracciari and Gaudio Mansueto. At some point during the run, the other Italian débutante, Giannina Russ, stepped into the production and this has led to speculation that Boninsegna was ‘protested’ and ‘removed’. Stories surrounding it have created a legend that has become the defining event in her career. She actually sang twelve performances, including, on 29 January 1905, a gala celebration of the tenth revival of the opera at that theatre. Her reviews were excellent, generously praising “the exceptional beauty of her well trained voice, her brilliant top register and sweet mezza voce’” There is not a shred of evidence that she failed to please the Milan public. It is an interesting tale that has no foundation in fact.

She returned to the comfort of Covent Garden in October for repeats of Un Ballo in Maschera and Aid’ along with a new role for London, the Il Trovatore Leonora. She repeated her success and stayed for a total of thirteen performances. On 13 October, the Times critic wrote “this was a very fine performance of Aida, and that Boninsegna “has never sung the role better in London, perhaps, never as well”. On the 19th of November, she sang in a concert for the benefit of Italian Earthquake Victims, with Melba, Didur, Zenatello, Stracciari and Sammarco.

She debuted at Madrid’s Teatro Real on 16 December as Aida. The next day’s reviews bordered on the ecstatic and additional performances of the opera were immediately scheduled. El Liberal said of a later performance: “the third act resulted in a most tumultuous ovation for Paoli and Boninsegna. The curtain was raised an infinite number of times in honour of these two artists.” El Pais called the fourth act of Il Trovatore a “complete triumph, climaxing in an enormous ovation for the ‘Miserere’.” After appearing in Un Ballo in Maschera and Damnation de Faust she sang the only Siegfried Brünnhildes of her career. Il Palcoscenico observed that at the final curtain, she and the legendary Italian Wagnerian, Giuseppe Borgatti, “were awarded an ovation that was almost indescribable.” She ended her season on 24 February 1906 with scenes from Aida in a benefit concert.

In late April, Boninsegna sang in Aida and Il Trovatore at Lisbon’s Teatro Coliseu and with these performances, her career in Portugal came to an end.

The stage was set for the next big moment. She sailed from Genoa for New York in early December 1906, and on the 21st, debuted at the Metropolitan Opera House as Aida with Kirkby Lunn, Caruso, Stracciari and Plançon. Musical Courier reported:

Boninsegna has a sympathetic and serviceable voice, not large and hardly adequate to the heavy demands of a part like Aida. But, in less strenuous moments, Boninsegna did some singing that showed good schooling and musical intelligence. Her high tones were clear, and she sings in tune and phrases well, on the whole.

Her next performance did not take place until 13 January 1907 when she sang ‘Voi lo sapete’ and the Bolero from I Vespri Siciliani in a concert. On the 21st, she repeated Aida with Homer, Caruso, Scotti and Journet. Musical Courier was a great deal more complimentary:

Boninsegna is certainly a beautiful singer and she has a voice of unusual purity. She is scarcely, perhaps, a sufficiently powerful actress for the part, her methods savored somewhat of conventionality. She sang exquisitely however, and could have taken half dozen encores should she have been so minded.

I have quoted verbatim, so we can only wonder about the meaning of “encores”. She concluded her season with two performances of Cavalleria Rusticana (one in Philadelphia), a concert and a third performance of Aida.

Robert Tuggle, the archivist of the Metropolitan Opera, in his book, The Golden Age of Opera says, “Heinrich Conried…. had great hopes for Celestina Boninsegna, an Italian dramatic soprano whom he featured prominently in his plans and advertising. (She) signed for five months and forty performances” but “was ill throughout her stay …. Without her voice to carry her, Boninsegna in Aida was merely what one colleague recalled as a large woman in chocolate colored underwear”. We are left with another legendary failure that has its roots in circumstances seemingly unrelated to her art.

She returned to Italy in mid season, and, on 26 March debuted at Palermo’s Massimo, again as Aida. Tullio Serafin, who conducted the revival, declared her mezza voce to be “of a beauty rarely, if ever, heard.”

On 5 December she returned in glory to Pesaro for a concert in her honour. Every single piece of music had to be encored and the ovations were so enormous that a second concert was immediately scheduled for two days later, and sold out. In honour of her homecoming, an inscribed ceramic vase was presented to her from the City of Pesaro and placed in the main lobby of the Liceo. So famous had she become that when she stopped for a simple overnight visit in July of the following year, it was reported as news in L’Adriatico.

On 15 November 1908, she returned to Madrid for Aida, Mefistofele, Tosca and Lohengrin. Her receptions were those about which singers dream.

La Epoca – 16 Nov – “I confess frankly, I do not remember seeing at the Real, and I have been attending performances for some thirty five years with regularity, an Aida or an Amneris better than La Boninsegna or La Parsi. Where can adjectives be found to describe their artistry and insights”.

Tosca was withdrawn after one performance. The production, the tenor, Giraud, and the baritone, Francesco Cigada, had been mercilessly protested, but:

Il Teatro – Dated 2 January 1909, reported: “Only the famous Boninsegna with her voice of rare beauty and power was able to allay the storm of boos. ‘Vissi d’arte’ had to be repeated and was acclaimed by all, including generals and other dignitaries’.

On 13 February, she returned to Rome’s Costanzi for Aida with Maria Claessens, Scampini and Viglione-Borghese.

Il Messagero: “Celestina Boninsegna showed a voice of sweetest timbre, not of great volume but of a beautiful equalization in all registers, perfectly schooled to sing the full spectrum of the role. She could not have been more enthusiastically received”.

In April she returned to Spain for a debut at Seville’s Teatro San Fernando. After appearing in Aida and Il Trovatore, the overly optimistic impresario ran out of funds and performances of Tosca, Lohengrin’and Mefistofele were cancelled. In the Autumn Genoa’s Politeama hosted her in Il Trovatore and Aida, and, during the last week in October, she again sailed for the United States on a journey that would have a very different outcome from the first.

Several industrialists and financiers resolved to form a permanent opera company in the city of Boston and launched a subscription drive to fund both the building of the theatre and the cost of the first season. The plan was announced in early 1908; the guarantee was met, and the theatre was ready to do business on 8 November, 1909.

The Boston Opera Company inaugurated its era with La Gioconda. Lillian Nordica, Louise Homer, Florencio Constantino, George Baklanoff and Juste Nivette sang before a sold out house, and the reviews told us that while there was vocal wear in Nordica’s voice, it had been a most memorable event.

On 10 November, Boninsegna debuted as Aida to thunderstorms of applause, according to the Boston American. Her colleagues, Claessens, Enzo Leliva, Baklanoff and Jose Mardones, were similarly greeted by an audience whose happiness at the success of the new company knew no bounds. Of Boninsegna, the Boston Globe reported: “The voice is flexible and uniformly pure in the upper register …. Recall the exquisite upper A closing her aria in Act III before Amonasro’s entrance” There was disagreement in the press about her acting and her appearance. One commentator noted that she was “too tall and commanding in fact to be the Ethiopian slave girl, unless Amneris should be sung by a giantess”. In mid season, the company spent about a month touring the United States ‘Heartland’, with an extended stay in Chicago, where her Aida opened the engagement. The Chicago News noted: “Celestina Boninsegna visualized the title role heroically. She is a fine type of dramatic soprano, who captivated the audience early and kept them to the last’. The Chicago Journal wrote of her Il Trovatore Leonora: “Her singing deserves all praise because of its purity and freshness” and Musical Courier commented that her Valentine in Les Huguenots was “a remarkable vocal performance”. The company returned to Boston in early February and Boninsegna continued to perform until 7 March, when she sang a single Tosca. Thie Boston American, on 8 March said, “Celestina Boninsegna revealed herself as a Tosca compared to whom Farrar’s is a giggly schoolgirl. The second act revealed a queen of tragedy. All the emotions seemed at the command of the singer. She was vocally superb in this act”. Musical America reported that she encored the ‘prayer’. Unquestionably, these engagements had been extremely satisfying.

From Boston, she sailed to South America for the first visit in eight years and her debut at Montevideo was an enormous success. She appeared in seven operas and each one had to be repeated several times during her stay at Uruguay’s capitol. The tour visited Santiago del Estero and Tucuman, Argentina and continued performances into the mid summer. 1911 was to be the most important year in her career. She was invited by Pietro Mascagni to be the spinto prima donna on an extensive tour in South America, intended to showcase his operas. It would forever be known as ‘The Mascagni Tour’. On 15 April, 1911, the Teatro Carlo Felice of Genoa hosted a dress rehearsal of Mascagni’s soon-to-be-premiered opera, Isabeau. The theatre was closed to all but a few and the sessions went on for many hours. At the end of the day, Mascagni expressed his satisfaction, and the following morning, he left for South America with a formidable group of artists.

Boninsegna inaugurated the season as Aida at the Teatro Coliseo of Buenos Aires on 6 May with Hotkowska, de Tura, Romboli and Mansueto. The greeting for Mascagni as he stepped onto the podium was enormous, and at the end of the evening, he and the soloists received an ovation that lasted so long that the lights had to be lowered in order to clear the theatre (La Prensa). On 2 June, Mascagni conducted the World Premiere of Isabeau with Farneti, Saludas, Galeffi and Mansueto. There was such a crush for tickets that the performance had to be delayed while police attempted to restore order around the opera house. At the conclusion, the audience demonstrated its enthusiasm into the morning hours, first in the theatre and then in the surrounding streets. The newspapers declared it a complete triumph, comparing it to Debussy, Richard Strauss and other non Italian composers. It was called “brilliant”, a “new and fascinating direction” and “Mascagni’s finest achievement”. There were eight performances. Farneti also sang in Lohengrin, La Bohème and Iris, while Boninsegna appeared in Il Trovatore, Cavalleria Rusticana, Mefistofele and Guglielmo Ratcliff. Pagliacci, featuring Galeffi’s defining Tonio, rounded out the repertoire at Buenos Aires. On 21 June the season at the Coliseo ended and the company then toured to Rosario, Rio de Janeiro, São Paolo, Montevideo, Santiago (Chile) and Valparaiso.

At Rio – O Diario de Noticias – 21 July – Mefistofele: “If (Italo) Cristalli is neither better nor worse than the average Italian tenor of our day, Signora Boninsegna is clearly an artist of distinction. Undertaking both roles, Margherita and Elena, she not only rose to Boito’s melodies but also managed to differentiate vocally between the timid peasant and the reigning queen. Margherita sang the first two acts with a slender, lyrical voice, only letting it out in the prison scene, when madness overtakes reason. Elena, on the contrary, was imperial of manner and of declamation”.

The company travelled from Montevideo over the Andes through heavy snow, and, on 1 September, as the train approached Santiago, it was obliged to stop at several towns to hear local bands play the Italian and Chilean National Anthems, in honour, particularly, of Mascagni. The entourage finally reached the Estacion Alameda at about eleven in the evening where it was greeted by local dignitaries and thousands of fans, who had been waiting since midday. The following evening, in a theatre decorated with flowers of every description, Mascagni conducted Iris. Boninsegna’s first role was Aida.

El Mercurio: “Boninsegna was having one of her most inspired evenings and walked off with all of the applause. She only enhanced the impression of previous visits”.

On the evening of the Mefistofele premiere, Boninsegna was asked once again to sing the National Anthem. “An enormous and sentimental ovation ensued”. The tour ended on 24 October at Valparaiso, fittingly enough with Isabeau. When the company embarked for Europe, additional thousands appeared to wave them off, and the Chilean press declared that this season had been the most exciting in memory. Inexplicably, Boninsegna never sang in South America again.

On 10 Feb, 1912, Mascagni conducted another of Boninsegna’s important Italian debuts, Aida at Venice’s Fenice. It was so well received that four announced performances became six. In March, she appeared in Russia for the first time, singing seven roles at Kiev. March also saw her at Pesaro’s Teatro Rossini in the composer’s Stabat Mater and in April she debuted at the Barcelona Liceo as Aida. A week later she sang the Il Trovatore Leonora. Her reviews were generally exceptional, though her height was considered a detriment, especially in Aida.

In the Spring of 1913 she toured to Siena’s Chiesa San Francesco, Firenze’s Chiesa Santa Croce, Bologna’s Teatro Comunale and Ferrara’s Chiesa San Francesco in Verdi’s Messa di Requiem in commemoration of the Centenary of the composer’s birth. At Siena, five performances became six, and, at Florence, the church doors were left open so that overflow crowds could at least hear the music.

Just before the first performance at Ferrara was about to begin, an elderly woman was escorted to the front row and seated. A buzz filled the church as people pointed and whispered. She sat in silence, looking only at the altar, and, at the end, slowly stood and led the huge ovation. When the applause subsided, many rushed to her and were heard to tell her how wonderful it was to see her and to marvel that she had come to the event. “Have you not heard Boninsegna’s recordings? Who, in the World, would not be here if they could?” It is said that four weeks later she attended Aida at the Teatro Verdi, and that, at the end, she returned to the Palazzo Massari on Corso Parto Mare, to the seclusion that had been hers since the death of her husband in 1902, and which would again be hers until her death in 1920. She was Maria Waldmann Massari, who had sung Amneris in the Italian premiere of Aida and the mezzo part in the World Premiere of the Requiem. Maria Waldmann Massari had sung Amneris in the Italian premiere of Aida and the mezzo part in the World Premiere of the Requiem.

On 26 December, Boninsegna had the honour of another opening night at the Costanzi, this time with Le Damnation de Faust. La Tribuna reported: “Celestina Boninsegna, though in a range not totally congenial to her temperament, is an artist of great valour. In the ‘Song of Thule’ she sang with great expression, and in the passionate duet that follows, she won the full appreciation of the audience”. During this period, Boninsegna, programmed a number of concerts, including several with Bernardo De Muro and at least one fascinating outing with her renowned rival, Eugenia Burzio at Florence.

Boninsegna next debuted at St. Petersburg on 23 January in Un Ballo in Maschera and, after a month of performances, toured to Moscow, Kharkov, Odessa and Kiev in what may fairly be described as the last truly prestigious engagements of her career. De Luca joined the company in early February and Francesco Navarrini joined her and Battistini in Ernani during his last tour to Russia. She assumed the roles of Maria di Rohan and Mozart’s Donna Anna for the first and, apparently, the last times.

The road ahead was to be a very bumpy one for our heroine, as it would be for many singers. World War I was waiting on the horizon. For the next four years she appeared sporadically in several Northern Italian cities and towns. Conditions became very difficult and many theatres closed. A contemporary report in Il Teatro Reinach of Parma by Gaspare Nello Vetro describes the situation. Of a La Gioconda performance in 1918, it says: “the evening was exceptional for the performance of the grand Boninsegna, but the revival showed how difficult it is to mount a worthy performance among the male singers, orchestra and chorus in the middle of a war”. The Armistice was signed on 11 November and in early December, at Milan, she sang in a massive concert of celebration for the benefit of the Red Cross.

1919 was her last hurrah but it was a good one, encompassing some sixty performances. She returned to the scene of that early failure, Bari, and sang in Aida, Tosca and La Gioconda. The Petruzzelli chronology states: “La Boninsegna sang with great expression and received long and justly deserved applause in Aida”. She spent most of the year in well known Italian operatic centres, including an extended stay at Milan’s Teatro Lirico in La Forza del Destino and Il Trovatore.

By 1920, she was receiving very equivocal reviews, particularly addressing stress in the middle range. A final trip to the Western Hemisphere was undertaken in the autumn. She sang Il Trovatore and Aida at Havana and Mexico City, and, according to verbal reports, Tosca. Reviews were not kind and it became apparent that she could no longer sustain a career. In January of 1921 she left the opera stage after performances of La Forza del Destino at Modena. Her announced farewell was at Pesaro in a recital dedicated to her honour and in recognition of her achievements. The date was 6 November 1921. However, Charles Mintzer very recently found documentation of a concert at Sassuolo in August of 1938. There may still be more to tell. Before her death in 1947 she taught for a number of years at both Pesaro and Milan.

This has been an exciting journey for me as I hope it has been for the reader. For nearly half a century Boninsegna has been dismissed by vocal historians as an insignificant singer with a singularly unsuccessful career. The pictures that have been painted consistently portray a rather drab succession of mediocre engagements with less than laudatory receptions. That image is certainly not reflective of truth. She had one failure, at Bari, where she was reviewed as “unprepared” in her role. In fact, I am at a loss to know precisely what that means. The Scala and Met myths are exactly that. They are not and never were grounded in fact. What is the truth? She sang well over one thousand performances in a career that spanned twenty-five years. She appeared at most of the important theatres in the Latin World and was rapturously received almost everywhere she sang. Her excursions to London, Boston, Chicago and Russia were unqualified successes and her reputation in Italy was without blemish. When we listen to the manifest glories of her recordings, we don’t wonder for a moment about the extraordinary reviews she received at Madrid, nor about those at Santiago, Rio de Janeiro and Rome. We hear a grandeur that is breathtaking, a presence to which others of her generation could only aspire. When we marvel over the control at the top of the voice we don’t wonder why Boston, Chicago and, yes, even Met audiences were impressed. The clarity and beauty of her tone received unqualified praise in every city at which she appeared and her musicianship was universally admired. Boninsegna was a major talent who was lavishly praised in her own time, just as her recordings are, today. Her very name is, appropriately, a lovely poem. It has been my privilege and honour to revise one small piece of history.

I wish to express my thanks, first to the editor and Tom Kaufman for their encouragement and guidance, and to Juan Dzazopulos, Eduardo Gabarra, Stephen Herx, Charles Mintzer, Robert Tuggle and Peter Wilson for providing a great deal of additional information. I am particularly grateful for the research of the late Charles Jahant, whose archive of information on Boninsegna provided much of the framework for this article.

Various documents have stated that she sang Desdemona, Wally, and Lucrezia Borgia, but I have found no firm evidence of these roles after six years of looking around. If any readers can shed light on these or other roles not chronicled, it would be most appreciated and would help to complete her repertoire.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Aida#Giuseppe Verdi#Ritorna vincitor#Celestina Boninsegna#dramatic soprano#soprano#Royal Opera House#Covent Garden#La Scala#Teatro alla Scala#Metropolitan Opera#Met#Mariinsky Theatre#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians

0 notes

Text

Examen 2

Título: Historia del concepto de manierismo en arquitectura

Autor: Eugenio Battisti

Fecha de publicación: 1962

Idioma: Español

Análisis

En el texto, Battisti sostiene que, si bien no se hablaba propiamente de construir o proyectar según una "manera" en el siglo XVI, sí se registraron polémicas en contra de una actitud creativa análoga a la de los pintores y escultores manieristas. Esta actitud se caracterizaba por la elaboración y recombinación de modelos clásicos, el alejamiento de las normas lógicas de la naturaleza y los cánones de la arquitectura clásica, y una excesiva libertad, independencia, experimentación y búsqueda de la vanguardia.

Battisti cita ejemplos de estas críticas, como las acusaciones contra la cornisa de Miguel Ángel para el palacio Farnese, que se consideraba desordenada y desproporcionada, y las críticas contra los frescos de Pontormo en San Lorenzo, que se consideraban caóticos y sin orden.

Battisti también señala que, si bien estas críticas eran difusas, también había defensores de lo que podría definirse como el manierismo decorativo. Un ejemplo de ello es Sebastiano Serlio, quien en su Libro Extraordinario defendía el uso de la ornamentación para satisfacer el gusto de los clientes por las novedades.

Conclusión:

El texto de Battisti se centra en la arquitectura italiana del siglo XVI. Sin embargo, el manierismo también se desarrolló en otros países, como España y Francia.

El manierismo es un estilo complejo y controvertido que ha sido objeto de debate por parte de los historiadores del arte. Algunos lo consideran un período de decadencia, mientras que otros lo ven como un período de innovación y creatividad.

Países

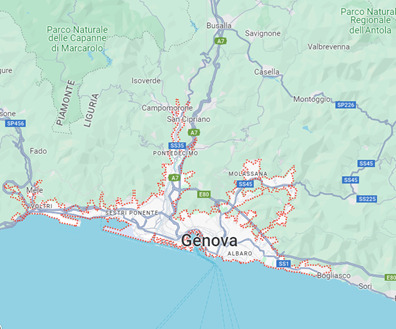

Italia Génova

(Vista panorámica aérea del puerto de Foto de stock 2291943323, s/f)

Vista panorámica aérea del puerto de Foto de stock 2291943323. (s/f). Shutterstock. Recuperado el 2 de junio de 2024, de https://www.shutterstock.com/es/image-photo/genoa-port-aerial-panoramic-view-genova-2291943323

Génova es una ciudad portuaria y la capital de la región de Liguria, en el noroeste de Italia. Es conocida por la función central que desempeña en el comercio marítimo hace varios siglos. En la ciudad antigua, se encuentra la catedral románica de San Lorenzo, con una fachada a franjas blancas y negras, y frescos en su interior. Tiene callejones angostos que llegan a plazas monumentales como la Piazza De Ferrari, donde hay una icónica fuente de bronce y se encuentra la sala de ópera Teatro Carlo Felice.

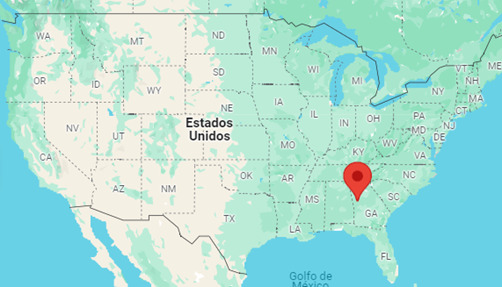

Estados Unidos

(Vista panorámica aérea del puerto de Foto de stock 2291943323, s/f)

Vista panorámica aérea del puerto de Foto de stock 2291943323. (s/f). Shutterstock. Recuperado el 2 de junio de 2024, de https://www.shutterstock.com/es/image-photo/genoa-port-aerial-panoramic-view-genova-2291943323

Turín es un pueblo ubicado en el condado de Coweta en el estado estadounidense de Georgia. En el censo de 2000, su población era de 165.

Manierismo

El manierismo fue el estilo que caracterizó el arte europeo entre los años 1520 y 1600, aproximadamente. Este surgió en Italia y desde allí se difundió hacia casi toda Europa, a través del trabajo de los artistas italianos en las distintas cortes reales.

(Maurizio, 2021)

Maurizio, P. (2021, febrero 9). Manierismo. Enciclopedia Iberoamericana. https://enciclopediaiberoamericana.com/manierismo/

Alumna: Scarlet Escobar

0 notes

Text

Giovanni De Luca, il giovane grande baritono che canta Puccini a Londra

Di Annalisa Valente Parla Giuseppe De Luca, il baritono che sta celebrando a Londra il centenario della morte di Puccini con il Maestro Antonio Morabito. Giovanni De Luca, il giovane grande baritono che canta Puccini a Londra Dal Teatro alla Scala di Milano al Bellini di Catania, dal Teatro Carlo Felice di Genova alle più belle e caratteristiche cattedrali del Regno Unito, partendo proprio da Londra. La carriera del baritono Giuseppe De Luca, da studente del Conservatorio di Reggio Calabria, ha spiccato il volo e nel corso degli anni è diventata sempre più prestigiosa e ricca di collaborazioni illustri. Ultima in ordine di tempo è quella che lo vede protagonista, in questo mese di Aprile, insieme al Maestro Antonio Morabito in una serie di concerti promossi in occasione del centenario della morte del compositore Giacomo Puccini. Le date, patrocinate dal Consolato Generale d'Italia a Londra, si stanno svolgendo a Londra (qui l'articolo). Dopo aver presentato nelle settimane scorse il ciclo di concerti proprio col Maestro Morabito (qui l'articolo), ora ne parliamo anche con il baritono Giuseppe De Luca. Non è la prima volta che nella sua carriera omaggia un mito come Puccini. Cosa l’ha convinta ad accettare la proposta del suo amico Antonio Morabito per esibirsi con lui nelle prossime date a Londra? Sicuramente la stima e l'amicizia che nutriamo l'uno per l'altro da molto tempo. Infatti io e Antonio ci conosciamo da diversi anni, come ex studenti del Conservatorio di Reggio Calabria. Quando mi ha proposto questo progetto ho accettato subito con grande piacere e felicità! E’ la prima volta che lavorate insieme a un tale livello artistico? Si, questo è il nostro primo progetto insieme e non nascondo che abbiamo parlato già di altri progetti futuri molto allettanti. Lei ha un curriculum davvero incredibile nonostante la giovane età. C’è un posto in Italia (o anche al di fuori) dove non si è ancora esibito e dove magari le piacerebbe cantare? In Italia ho coronato il sogno del Teatro alla Scala, ma vorrei esibirmi anche al Teatro San Carlo di Napoli, un vero gioiello italiano. Mentre all'estero mi piacerebbe esibirmi al Metropolitan Opera di New York. Qual è la collaborazione artistica che vorrebbe sperimentare ma non ha ancora avuto occasione? Ci sono molti nomi che mi vengono in mente, di cantanti che stimo tantissimo e con cui vorrei collaborare un giorno, ma ogni esperienza porta con sé nuove conoscenze e amicizie, quindi sono felice di tutte le collaborazioni. Ha mai pensato di insegnare canto alle nuove generazioni? Questo è un argomento per me molto importante. A me piace dare dei consigli, mi piace condividere quello che conosco, ma insegnare al momento credo di no. Spesso la diamo per scontata ma la figura dell'insegnante è davvero importante: è quella persona che ha il compito di, oltre che insegnare la pratica e la teoria, farti appassionare sempre e credere in te stesso. Questo vale ovviamente in ogni campo e materia di studio. Io sotto questo punto di vista sono stato sempre molto fortunato sin da quando ho iniziato. Quindi il ruolo dell'insegnante è davvero pieno di responsabilità e bisogna esserne consapevoli prima di dedicarsi a questo mestiere. C’è un modello artistico a cui si è ispirato nella sua professione? Chi è il suo maestro? Come dicevo prima, ho sempre avuto ottimi Maestri ma voglio citare colui a cui sono stato più legato, Rolando Panerai. Oltre ad un Maestro è stato anche un caro amico e mi ha dato davvero tanto! Tutt'ora, anche se non c'è più, lui continua a darmi, e prendo ispirazione da lui. Quali sono i suoi programmi dopo i concerti pucciniani di questo mese in UK? Subito dopo i concerti sarò impegnato a Reggio Emilia per una produzione de “La Serva Padrona” (Intermezzo di Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, n.d.r.) e subito dopo all'Accademia Rossiniana del Rossini Opera Festival (festival musicale lirico annuale che si svolge a Pesaro, città natale di Gioacchino Rossini, n.d.r.) nella produzione de “Il Viaggio A Reims”. ... Continua a leggere su Read the full article

1 note

·

View note

Text

Toti, Carlo Felice protagonista programmi culturali in Liguria

Il presidente della Regione Liguria Giovanni Toti ha assistito questa sera alla prima de “La bohème”, opera di Giacomo Puccini, in scena al Teatro Carlo Felice di Genova. Si tratta del settimo titolo del ricco cartellone della Stagione Lirica dell’Opera Carlo Felice e l’allestimento viene ripreso in occasione delle celebrazioni per il centenario della morte del compositore. “Il Carlo Felice è…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

150 anos da Ópera Salvator Rosa, de Carlos Gomes

Em março/2024 comemora-se 150 anos da ópera Salvator Rosa, de Carlos Gomes. Com estreia no dia 21 de março de 1874, no Teatro Carlo Felice, em Gênova, sua narrativa inspira-se livremente na vida do pintor de mesmo nome. Óperas que contam a vida de artistas eram comuns na época, e essa é talvez uma das mais bonitas.

Com melodias cativantes, e tendo como enredo a história de um herói italiano, a ópera agradou ao público já na sua estreia. Destaca-se a ária "Di sposo, di padre" interpretada pelo duque D’Arcos no segundo ato.

Ouça a gravação do Staatstheater Braunschweig 2012, com - Ray Wade Junior: Salvator Rosa - Maria Porubcinova: Isabella - Dae-Bum Lee: Duque d’Arcos

Para comemorar seu aniversário, que tal conferir também nos links abaixo as aberturas de óperas do compositor?

A noite do castelo (Prelúdio)

Condor (Prelúdio)

Fosca (Sinfonia)

Il Guarany (Sinfonia)

Joana de Flandres (Prelúdio)

Lo schiavo (Prelúdio)

Maria Tudor (Prelúdio)

Salvator Rosa (Sinfonia - Overture)

0 notes

Text

Grande evento musicale a Novi Ligure: l’Orchestra del Teatro Carlo Felice al Teatro Marenco

Un’occasione unica per gli appassionati di musica classica: giovedì 28 novembre il Novi Musica Festival 2024 ospita l’Orchestra del Teatro Carlo Felice di Genova.

Un’occasione unica per gli appassionati di musica classica: giovedì 28 novembre il Novi Musica Festival 2024 ospita l’Orchestra del Teatro Carlo Felice di Genova. Concerto-conc_Wiener Klassik_2811_A3_exeDownload La città di Novi Ligure si prepara ad accogliere un evento straordinario nell’ambito del Novi Musica Festival 24, organizzato dall’Associazione Novi Musica e Cultura. Il 28 novembre,…

#Alessandria cultura#Alessandria today#arte e musica Novi#Beethoven Sinfonia 1#biglietti concerto Novi#concerto violino#Cultura italiana#cultura Novi Ligure#eventi culturali Alessandria#eventi musicali 2024#eventi novembre 2024#Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Alessandria#fondazioni culturali Piemonte#Friends Novi Musica#Google News#italianewsmedia.com#Kolja Blacher#Kolja Blacher maestro#Ludwig van Beethoven#Mozart Concerto 5#Musica Classica#musica live Piemonte#Novi Ligure appuntamenti#Novi Ligure eventi#Novi Musica Festival#Orchestra Carlo Felice#Orchestra Sinfonica#Pier Carlo Lava#rassegna musicale Novi#Regione Piemonte

0 notes

Text

The Top 40 Most Popular Operas, Part 3 (#21 through #30)

A quick guide for newcomers to the genre, with links to online video recordings of complete performances, with English subtitles whenever possible.

Verdi's Il Trovatore

The second of Verdi's three great "middle period" tragedies (the other two being Rigoletto and La Traviata): a grand melodrama filled with famous melodies.

Studio film, 1957 (Mario del Monaco, Leyla Gencer, Ettore Bastianini, Fedora Barbieri; conducted by Fernando Previtali) (no subtitles; read the libretto in English translation here)

Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor

The most famous tragic opera in the bel canto style, based on Sir Walter Scott's novel The Bride of Lammermoor, and featuring opera's most famous "mad scene."

Studio film, 1971 (Anna Moffo, Lajos Kozma, Giulio Fioravanti, Paolo Washington; conducted by Carlo Felice Cillario)

Leoncavallo's Pagliacci

The most famous example of verismo opera: brutal Italian realism from the turn of the 20th century. Jealousy, adultery, and violence among a troupe of traveling clowns.

Feature film, 1983 (Plácido Domingo, Teresa Stratas, Juan Pons, Alberto Rinaldi; conducted by Georges Prêtre)

Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, Part VI

Mozart's Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio)

Mozart's comic Singspiel (German opera with spoken dialogue) set amid a Turkish harem. What it lacks in political correctness it makes up for in outstanding music.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 1988 (Deon van der Walt, Inga Nielsen, Lillian Watson, Lars Magnusson, Kurt Moll, Oliver Tobias; conducted by Georg Solti) (click CC for subtitles)

Verdi's Un Ballo in Maschera

A Verdi tragedy of forbidden love and political intrigue, inspired by the assassination of King Gustav III of Sweden.

Leipzig Opera House, 2006 (Massimiliano Pisapia, Chiara Taigi, Franco Vassallo, Annamaria Chiuri, Eun Yee You; conducted by Riccardo Chailly) (click CC for subtitles)

Part I, Part II

Offenbach's Les Contes d'Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann)

A half-comic, half-tragic fantasy opera based on the writings of E.T.A. Hoffmann, in which the author becomes the protagonist of his own stories of ill-fated love.

Opéra de Monte-Carlo, 2018 (Juan Diego Flórez, Olga Peretyatko, Nicolas Courjal, Sophie Marilley; conducted by Jacques Lacombe) (click CC and choose English in "Auto-translate" under "Settings" for subtitles)

Wagner's Der Fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman)

An early and particularly accessible work of Wagner, based on the legend of a phantom ship doomed to sail the seas until its captain finds a faithful bride.

Savolinna Opera, 1989 (Franz Grundheber, Hildegard Behrens, Ramiro Sirkiä, Matti Salminen; conducted by Leif Segerstam) (click CC for subtitles)

Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana

A one-act drama of adultery and scorned love among Sicilian peasants, second only to Pagliacci (with which it's often paired in a double bill) as the most famous verismo opera.

St. Petersburg Opera, 2012 (Fyodor Ataskevich, Iréne Theorin, Nikolay Kopylov, Ekaterina Egorova, Nina Romanova; conducted by Mikhail Tatarnikov)

Verdi's Falstaff

Verdi's final opera, a "mighty burst of laughter" based on Shakespeare's comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor.

Studio film, 1979 (Gabriel Bacquier, Karan Armstrong, Richard Stilwell, Marta Szirmay, Jutta Renate Ihloff, Max René Cosotti; conducted by Georg Solti) (click CC for subtitles)

Verdi's Otello (Othello)

Verdi's second-to-last great Shakespearean opera, based on the tragedy of the Moor of Venice.

Teatro alla Scala, 2001 (Plácido Domingo, Leo Nucci, Barbara Frittoli; conducted by Riccardo Muti)

#opera#top 40#21 through 30#video#complete performances#english subtitles#il trovatore#lucia di lammermoor#pagliacci#die entfuhrung aus dem serail#the abduction from the seraglio#un ballo in maschera#les contes d'hoffmann#the tales of hoffmann#der fliegende holländer#the flying dutchman#cavalleria rusticana#falstaff#otello

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoli milionaria! Tornano in tv le commedie di Eduardo De Filippo

Napoli milionaria!: da stasera, 18 dicembre, tornano in tv le commedie di Eduardo De Filippo. Prosegue la tradizione di Rai1 di proporre in prima serata, a una settimana dal Natale, la versione televisiva di una commedia del grande drammaturgo napoletano. Quest'anno tocca a Napoli milionaria!, appunto, interpretata da Massimiliano Gallo e Vanessa Scalera. Non finisce qui: da oggi, su RaiPlay saranno disponibili le commedie di Eduardo in versione originale. Napoli milionaria! le macerie della guerra nella commedia di Eduardo De Filippo Poche settimane dopo la liberazione, Eduardo si affacciò al balcone della sua casa al parco Grifeo a Napoli e la vista della città martoriata gli suggerì il soggetto di una nuova commedia. La scrisse, come lui stesso raccontò, tutta d'un fiato come fosse stato un "lungo articolo sulla guerra e sulle sue deleterie conseguenze". La commedia debuttò al teatro San Carlo il 15 marzo 1945 e fu rappresentata in molti Paesi europei. Nel 1950 divenne un film per la regia dello stesso Eduardo che firmò anche la sceneggiatura e selezionò il cast. Al ritorno dalla sua esperienza di prigioniero di guerra, Gennaro Jovine trova nella sua città e nella sua casa solo macerie. Una città distrutta dai bombardamenti e una famiglia disgregata dalla decadenza morale. Sono queste le conseguenze deleterie della guerra. Indimenticabile la battuta di chiusura da egli stesso pronunciata: "Ha da passa' 'a nuttata". L'attualità di Eduardo Le aberrazioni della guerra e il potere del denaro sono i grandi temi della commedia di Eduardo, considerata la più contemporanea, scelta quest'anno per quella che è diventata una consuetudine della Rai a ridosso del Natale. La felice tradizione è iniziata con Natale in casa Cupiello, e proseguita con Sabato, domenica e lunedì e Filumena Marturano. A inaugurarla è stato Sergio Castellitto che ha vestito i panni nel 2020 di Luca Cupiello affiancato da Marina Confalone e, l'anno dopo, di Peppino Priore con al suo fianco Fabrizia Sacchi. Nel 2022, è stato Massimiliano Gallo a interpretare il ruolo di Domenico Soriano, al fianco di Vanessa Scalera. La coppia, affiatatissima e già apprezzatissima dalla tv, torna quest'anno a interpretare altri due grandi personaggi dell'universo eduardiano: Gennaro e Amalia Jovine. La nuova versione televisiva è stata affidata alla regia di Luca Miniero. Le commedie di Eduardo su RaiPlay Il rapporto tra la Rai e il teatro di Eduardo De Filippo inizia, in realtà, molto tempo fa. Negli anni Cinquanta Eduardo intuì le potenzialità del mezzo televisivo, intuì che avrebbe raggiunto fette di pubblico più ampio e che le sue opere sarebbero state conosciute anche dalle generazioni future. Decise così non solo di affidargli il suo lavoro ma di creare un nuovo genere: quello del Teleteatro. Riprodusse le sue commedie in tv adottando uno stile di regia tutto suo, che potesse restituire almeno in parte l'emozione del teatro. La preziosa collezione sarà nuovamente visibile grazie all'iniziativa della Rai di rendere disponibili i titoli sulla sua piattaforma digitale. Sempre a partire da oggi, su RaiPlay sono disponibili: - Natale in casa Cupiello, la versione del 1962 con anche Nina De Padova e Pietro De Vico, e quella del 1977 con anche Luca De Filippo, Pupella Maggio, Gino Maringola e Lina Sastri; - Miseria e nobiltà (1955); - Bene mio e core mio (1955); - Il berretto a sonagli (1981); - Il contratto (1981); - Filumena Marturano nella versione del 1962 con Regina Bianchi nella parte della protagonista; - Napoli milionaria; - Non ti pago; - Uomo e galantuomo; - Il sindaco del rione Sanità; - Questi fantasmi; - Gli esami non finiscono mai; - Amicizia; - Lu curaggio de nu pumpiero napulitano; - Mia famiglia In copertina foto di ran da Pixabay Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Verdi - Un Ballo in Maschera - Re dell'abisso - Irene Minghini-Cattaneo (1930)

Orchestra e Coro del Teatro alla Scala di Milano Carlo Sabajno, conductor HMV, 1930

Irene Minghini Boschi was born at Lugo, Italy on 12 April, 1892 and was encouraged at the age of fourteen to pursue a musical career. Her studies continued for a number of years but were curtailed by the outbreak of World War I. In 1918 Irene made her debut at Savona in “Il Trovatore” and later in the season she appeared at Brescia in “Isabeau” and at Rome’s Teatro Adriano as the Countess in “Andrea Chenier”. She was dissatisfied with her own abilities and decided to move to Milan, where she was accepted as a student by Ettore Cattaneo, who was not only an eminent musicologist and conductor, but was the senior director of the house of Ricordi.

After a very brief period of study, Cattaneo announced that his protégé was ready, and in March of 1919 Irene debuted at Milan’s Teatro Carcano as Madelon in “Chenier” and a short time later, as Amneris. The Verdi opera was the subject of superb notices and before the year was out, she had also sung the Egyptian princess at Carrara and had appeared at Mestre.

Irene had, from the beginning, dropped her family name and appeared only as Irene Minghini, for reasons never explained. On 22 March, 1920 she married Maestro Cattaneo and immediately assumed his name for professional as well as personal reasons. After a very brief honeymoon, she appeared at Empoli on 6 April as La Cieca and in the summer she appeared at Siena in “Rigoletto” and later in “Aida” with Eva Pacetti. She returned to the Carcano in December for “Il Trovatore” with Ester Mazzoleni, Giovannoni and Francesco Maria Bonini and at year’s end in “Aida” with Oliva Petrella.

January of 1921 afforded her a very important debut, Preziosilla at the Teatro Petruzzelli of Bari and in the spring she appeared in “Il Trovatore” at Ravenna, Cesena and Forli. Milan’s Arena offered a contract for la Cieca and at Macerata she appeared as Amneris. The very prestigious Dal Verme of Milan presented Irene in “Il Trovatore” in October and on 29 December she debuted as la Cieca at Parma’s Teatro Regio with Tina Poli Randaccio, the young mezzo, Giannina Arangi Lombardi, Ismael Voltolini, Giuseppe Noto and Bruno Carmassi. There were ten performances and they served as Irene’s entry into the mainstream of Italian operatic life.

1922 was a very important year in her career, beginning at Spezia in “La Favorita” and continuing at Piacenza as Quickly in “Falstaff” with Mariano Stabile as well as la Cieca with Fidela Campigna, Arangi Lombardi, Francesco Merli and Vincenzo Guiccardi. At Florence, she appeared in “Falstaff”, at Palermo in “Aida” and at the Dal Verme, she again sang in “Il Trovatore” as well as with Alessandro Bonci in “Un Ballo in Maschera”. At Rome’s Teatro Augusteo in December she sang in the Manzoni Requiem with Mazzoleni, Bonci and Nazzareno De Angelis, and her name became headline news at the Italian capital, though she would never be engaged at that city’s premiere opera house. In 1923 Irene returned to Florence for “Falstaff” and sang at Cremona for the first time in “La Gioconda” and “Falstaff”. At Ancona in March she sang in “Falstaff” and in April she sang at the Naples Teatro San Carlo in the Manzoni Requiem. They would turn out to be her only appearances at that august theater. In May Irene returned to Ravenna for “Falstaff” after which she took an eight month sabbatical, reportedly for a pregnancy, though my research has uncovered no definitive information.

On 1 February 1924 Irene returned to the stage with appearances as Amneris at Cremona and a month later she debuted at Genoa’s Carlo Felice as Quickly in a cast that included Linda Cannetti, and Luigi Montesanto. At Vicenza she sang in the Manzoni Requiem with Lucia Crestani, Giuseppi Taccani and De Angelis, conducted by Sergio Failoni, and the engagement as so successful that all the soloists were immediately engaged for performances at Verona during the summer. Two performances were given at the Arena and two were moved to the Teatro Filarmonico when violent thunderstorms threatened Berrettoni conducted and Isora Rinolfi shared soprano honors with Crestani. The year also included performances of “Il Trovatore” at the Dal Verme, at Nice and at Genoa, “Aida” at Trieste’s Teatro Rossetti and the Manzoni Requiem at the Augusteo with Bianca Scacciati, Franco Lo Giudice and Bettoni.

Minghini Cattaneo returned to Genoa for additional performances of “Falstaff” in January 1925 and to the Augusteo for Beethoven’s Symphony #9 at the Augusteo in April. In May, at Pavia, she sang Dalila for the first time and in July she appeared in “La Gioconda” at the Verona Arena. Arangi Lombardi had graduated to the title role and Irene to the role of Laura for the first time. Bergamo heard her as Leonora de Guzman, Reggio Emilia was the scene of her first Adalgisas, partnered by Arangi Lombardi, and at Parma, she sang in “Tristan und Isolde” with Gina de Zorzi, Lavarello and Carlo Tagliabue and in “Norma” with Vera Amerighi Rutili, Renato Zanelli and Umberto De Lelio.

1926 began with performances of “Un Ballo in Maschera” at Parma and continued with “Norma” with Amerighi Rutili at Cremona, “Falstaff” at Modena, “Il Trovatore” at Como, and in March an extended stay at Catania’s Teatro Massimo Bellini. She debuted in “Norma” on 6 March with Amerighi Rutili, Cingolani and Manfrini, and on the 20th, she sang in “Aida” with Arangi Lombardi, Nicola Fusati, Armando Borgioli and Manfrini. At Ravenna, she sang Brangaene to the Isolde of Maria Llacer and Amneris to the Aida of Maria Carena and later in the season, Irene appeared in seven performances of “Il Trovatore” at Verona’s Arena. In the autumn, the Teatro Comunale of Modena offered a gala, extra season revival of “Norma” with Amerighi Rutili and at Bologna, Minghini appeared at Bologna in “Lohengrin” with Giuseppina Cobelli, Beniamino Gigli and Borgioli, in “Il Trovatore” with Arangi Lombardi, Aureliano Pertile and Borgioli and in “Aida” with Stani Zawaska, Merli and Angelo Pilotto. The year ended with eleven performances of “Il Trovatore” at Brescia’s Teatro Grande.

Her first engagement in 1927 was a stellar revival of “Aida” at Turin’s Teatro Regio. Eva Turner and Maria Carena shared the soprano role and Pertile sang Radames under the baton of Gino Marinuzzi. At Nice, Irene appeared in “Il Trovatore” with Llacer, Pedro Mirassou and Apollo Granforte and in “Aida” with Llacer, and Mirassou. In May, she sang in “Il Trovatore” with Arangi Lombardi, Merli and Gaetano Viviani at Florence. and while there, sang in two concert performances of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony. She was now the reigning mezzo at Verona and her season included eleven performances of “Aida” with Arangi Lombardi, Antonio Cortis and Viviani and two performances of the Beethoven Ninth.

The musicologist and commentator, Dr. Garcia Montes, reported of “Aida” in Record Collector: “What a wonderful voice and temperament that woman (Cattaneo) had. I will always remember her duet with Arangi Lombardi in the second act and her scene with Antonio Cortis in the last act. There existed some sort of rivalry or competition between the admirers of Arangi Lombardi and Minghini Cattaneo (both singers were good friends, though) and the storms of applause after each passage sung by the said singers lasted for minutes.”

At Cesena she appeared in the Manzoni Requiem and at Bologna she appeared in six performances of “La Gioconda”, again singing Laura. Those who attended the revival read in the program that Irene Minghini Cattaneo had been engaged to join the Melba-Williamson company on a six month tour to Australia in the spring of 1928, and that she would be joined by Giannina Arangi Lombardi, Toti dal Monte, Francesco Merli, Apollo Granforte and other Italian artists of the first rank in the most ambitious operatic undertaking in that continent’s history. The best laid plans!

Somewhere between Bologna and Australia, the Cattaneos made a very sharp turn. On 3 March 1928 Irene Minghini Cattaneo debuted at La Scala in “Il Trovatore” with Arangi Lombardi, Merli, Galeffi and Baccaloni under Ettore Panizza’s baton. On 16 May, as Arangi and Merli were singing at Melbourne before sold out houses, Cattaneo was engaged in the World Premiere of Pizzetti’s “Fra Gherardo” at La Scala with Florica Cristoforeanu, Trantoul and Baccaloni under Arturo Toscanini’s direction. Irene, at her husband’s urging, had accepted a contract to debut at London’s Covent Garden, and the Australian contract was dismissed. There were very serious and negative implications to this decision, and as we shall later see, though she remained attached to the Milan theater at intervals, her career at Italy’s important venues was pretty much at an end. On 15 June, Irene appeared at Covent Garden for the first time, singing in “Aida” with Dusolina Giannini, Pertile, Borgioli and Manfrini under the leadership of Vincenzo Bellezza. Her reviews were more than respectful. “Amneris was played with much dignity…by Madame Cattaneo” – Daily Telegraph. On the 28th, she sang Marina in a revival of “Boris Guduonov” with Feodor Chaliapin and her reviews were less kind, complaining of a much too broad Italianate approach. “It required Chaliapin to restore balance” – Daily Telegraph. In August Cattaneo appeared at Rimini in “Il Trovatore” with Carena and Giacomo Lauri Volpi and on Christmas Night, she returned to Parma for “La Gioconda” with Arangi Lombardi, Luigi Marini, Borgioli and Contini.

La Scala welcomed Irene for three important revivals in 1929: “Lohengrin” with Rosetta Pampanini, Pertile and Galeffi, “Un Ballo in Maschera” with Scacciati, Carosio, Pertile and Galeffi and “Aida” with Arangi Lombardi, Pertile and Galeffi. Elizabeth Rethberg appeared as “Aida” in several performances. When Toscanini brought the Scala company to Vienna and Berlin later in the spring, Cattaneo was not invited to perform, to the surprise of many. She was a difficult colleague, and the resentments over her failure to honor contracts were reaping their unhappy rewards. She did have a contract for Covent Garden, where she appeared in “Norma” and “La Gioconda” with Rosa Ponselle and as Marina with Chaliapin. Her reviews in the two Italian operas were quite exceptional. The Times: “In Madame Cattaneo was found a mezzo soprano whose rich tones could both contrast and combine with those of Ponselle.” They, however, did not get along at all and there were skirmishes behind the curtain as well as unpleasant exchanges at the footlights.

In late June, Irene returned to Italy, to a very long “vacation”. It was not until December that she appeared on stage. On 26 December Novarra’s Teatro Coccia presented her in “Samson et Dalila”. The career was a shambles. The winter of 1930 provided her with only one engagement in Italy, “Il Trovatore” at Padua. On 2 May, Ettore died at Milan and Irene observed a fifteen day mourning period before returning to Covent Garden for “Norma” with Ponselle and “Aida” with Turner. This time, bridled anger became open hostility. Ponselle received a number of reviews that commented on intonation problems in softer passages while the vocalism of Minghini Cattaneo was lavishly praised. There were very ugly scenes between the two divas, and though the revival was completely sold out, there were only two performances. With this engagement, Cattaneo’s career in London came to an end. In September, she traveled to Zurich for the Manzoni Requiem with Arangi Lombardi, Roberto d’Alessio and Antonio Righetti and in December she appeared at Pavia as La Gioconda for the only time in her career. It was not a success. On New Year’s Eve, Irene sang Azucena at Bologna’s Teatro Duse. It was in 1930 that she recorded “Il Trovatore”, a defining performance which clearly shows that her problems upon the stages of the world had nothing to do with diminished vocal resources. As a compensation, it was known that Maestro Cattaneo, through his connections to Ricordi, had left Irene a great deal of money, an estate that allowed her to maintain an opulent villa at Rimini, where she would spend most of her time.

In April 1931, Irene appeared at the Duse in “Norma” and in May, she joined Amerighi Rutili in a spectacularly received revival of the Bellini opera at Forli. There were three performances and not a ticket was to be found. Cattaneo, in particular, was singled out for superlatives; Il Corriere Padano commented on “her commanding stage image, her gorgeous voice and her perfect intonation.” In June, she continued her succession of engagements as Italy’s minor theaters with “Il Trovatore” at Siena, and in August she returned in glory to Verona’s Arena for Elena in “Mefistofele” with Scacciati, Angelo Mighetti and De Angelis. Again, she decided after five performances that the role really had too high a tessitura, and she never again attempted it. In the autumn, Irene, appeared at Pistoia and at Athens in “Lohengrin”, and on 26 December she closed out the year at Catania in “Norma” with Campigna, Jesus de Gaviria and Antonio Righetti.

The winter of 1932 was spent at Cairo and Alexandria in “Aida”, “La Gioconda” and “Samson et Dalila” and in March she sang in “Norma” at Livorno with her nearly constant partner, Amerighi Rutili. It was not until December that she returned to the stage when she sang Ulrica at La Scala, partnered by Carena, Carosio, Pertile and Galeffi. There were five performances.

1933 was somewhat better for the nearly neglected mezzo. Parma hosted her in “Aida” and “La Gioconda”, Genoa’s Carlo Felice welcomed her back in “La Gioconda” with Gina Cigna, Alessandro Ziliani, Cesare Formichi and Corrado Zambelli, Pistoia offered Cattaneo and Cigna in “Norma”, and at Cagliari, in December, Irene sang in “Aida” with Amerighi Rutili, Luigi Marletta and Granforte. In January 1934 the ensemble brought the Verdi work to Sassari.

Piacenza engaged Cattaneo for “Aida” and “Il Trovatore, both with Arangi Lombardi, in February and in March there was a revival of “Il Trovatore” at Turin’s Regio with Carena, Lauri Volpi and Carlo Morelli. A long summer tour throughout Italy’s provinces took Irene’s time from the middle of June until September. The opera was “Norma”, the title role was shared by Amerighi Rutili and Maria Pedrini, and the towns visited were, Civitavecchia, Grosseto, Livorno, Siena, Montemarchi, Foligno, Frosinone, L’Aquila, Pescara, Foggia, Lecce, Avellino and four hugely applauded performances at Rome.

In September she returned to Bari for “Aida” with Pacetti and Giovanni Martinelli, who was making one of his very rare appearances in Italy, and in December she closed the year at Bologna’s Corso in “Lohengrin”. Where was the Rome Costanzi, where was the Naples San Carlo, why had Scala shunned her in the great mezzo roles for six years? Where were the Barcelona Liceo, the Lisbon Sao Carlo, the major German and Austrian theaters, where was Paris?

In fact, Paris was her next stop, but it did not happen until July of 1935. Tullio Serafin conducted a celebrated revival of “Falstaff” with Cattaneo, Ines Alfani Tellini, Pia Tassinari, Nino Ederle, Stabile and Ernesto Badini. In October she traveled to Venice, where, at the Palazzo Ducale she participated in the Manzoni Requiem with Margherita Grandi, Alessandro Granda and the bass, Ferrari. In November she finally sang at her birthplace, Lugo, in “Il Trovatore” with Pedrini, Breviario and Viviani. 1936 found Irene at only two theaters, Padua’s Verdi for “Aida” and Modena’s Comunale for “Lohengrin” with Licia Albanese, Pablo Civil, Viviani and Mongelli.

In 1937 she sang in “L’Arlesiana” and “Un Ballo in Maschera” at Como, in “Il Trovatore” at Modena and in the Manzoni Requiem at Trieste’s Teatro Verdi. 1938 included her only attempt at the Walkuere Brunnhilde, which was presented at Ravenna, “Aida” at Milan, Ostiglia, Genoa’s Piazza Vittoria, Catania and Ventimiglia, all outdoors. She also sang in “Norma” at Pesaro with Cigna, Ettore Parmeggiani and Flamini.

1939 was a rather interesting year for Irene. She sang in “L’Arlesiana” at Trieste with Tito Schipa, in “Re Hassan” at Venice’s Fenice with Cloe Elmo and Tancredi Pasero and in “Adriana Lecouvreur” for the first and only times in her career when she joined Pacetti, Galliano Masini and Gino Vanelli at Livorno’s Teatro Goldoni. “Il Trovatore” at Bologna and “Un Ballo in Maschera” at Milan’s Castello Sforzesco completed her season.

!940 saw her at only two cities; Pavia, where she sang in Vittadini’s “Anima Allegra” and “La Gioconda” when she returned to the role of La Cieca, and later in the year, Bolzano for additional performances as Cieca. Her farewell was assumed for many years to have been as La Cieca at La Scala in February of 1941, but she is known to have sung at San Sebastian, Spain in September of 1942. “Il Trovatore” was presented with Cigna, Irene and Lauri Volpi.

It was Lauri Volpi, in his “Voci Parallele” who wondered why Irene Minghini Cattaneo had achieved so little with such a prodigious talent. He praised her physical form, her acting abilities, and, most of all, her remarkable vocal talents. To leave this discussion with only a comment that she was the victim of an unpleasant disposition and bad decisions in the early years is not reasonable. Certainly, others were far more difficult, and they are among the giants of the twentieth century. No singer made unfailingly wise choices in unfolding their careers. I do not have an answer, except perhaps, that she knew best what she wanted from her career and her life, and that the picture is the one that she chose to paint.

It should be noted that, despite the fact that every previous biographical sketch has declared that she sang in South America, and that she did so with great success, neither statement is true.

Irene Minghini Cattaneo was found dead at her villa on 24 March 1944, the victim of a bombing attack by Allied forces just before the final surrender of the Italians.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Irene Minghini-Cattaneo#mezzo-soprano#Un Ballo in Maschera#Giuseppe Verdi#Verdi#La Scala#classical musician#classical musicians#classical voice#classical history#classical art#musician#musicians#music education#music theory#history of music#historian of music#diva#prima donna

1 note

·

View note

Text

#IdentitàPartenopea

NAPOLI 💙⚜

Città bistrattata, sottovalutata e abbandonata al giogo della criminalità organizzata. Ma Napoli non è così e non fu così. Lo è diventata. Metropoli brillante, aristocratica e colta, luogo d’incontro di svago e del bel mondo, viva e felice sotto la dinastia dei Borbone che inizia nel 1734 quando Carlo di Spagna conquista i regni di Napoli e Sicilia sottraendoli alla dominazione austriaca. Incoronato nel 1735 re delle Due Sicilie a Palermo, sceglie Napoli, come capitale del regno. Considerata dalla corte di Vienna un regno lontano e poco degno di prestigio…quasi fossero “le Indie”, Napoli in realtà era una magnifica metropoli di arte e cultura del Sud, per il Sud, per l’Europa, per il mondo, intorno alla quale si raccoglieranno ben presto letterati, filosofi e architetti provenienti da tutta Italia.

Il “buon re”, così come veniva chiamato Carlo di Borbone, farà venire a Napoli il toscano e saggio Bernardino Tanucci a cui affiderà le sorti finanziarie del regno. Pittori e architetti come Fuga e Vanvitelli per dare vita a teatri, porti, fortificazioni e ospedali. E’ l’inizio del gran settecento dei Borbone a Napoli e dintorni. La prima fabbrica di locomotive a Portici, e la vicina reggia dove insieme a Maria Amalia, sua sposa e figlia del re di Sassonia, si darà vita ad un maestoso progetto residenziale con due grandi parchi, l’orto botanico e il real museo delle antichità con i reperti e le sculture provenienti dagli scavi archeologici di Ercolano. E ancora, il palazzo reale a Napoli, il tunnel borbonico come via di fuga, il real albergo dei poveri, il Teatro San Carlo, il golfo di Napoli con la più grande acciaieria e i più grandi arsenali d’Italia.

Costretto a lasciare Napoli per tornare in Spagna, dopo 25 anni di regno, a Carlo succederà il figlio di otto anni, Ferdinando, che passata la reggenza, vedrà una Napoli all’apice del suo splendore con la regina Maria Carolina, severa e austera per amore della sua città. Centro di cultura e svago, la città partenopea attrarrà le più grandi corti d’europa e dei lumi, fino a quando con l’annessione al Piemonte e la successiva unità d’Italia nel 1861 si passerà dall’epoca d’oro settecentesca ad un periodo di brigantaggio nato dalla reazioni sanguinose suscitate dalla politica repressiva dei piemontesi e parallelamente l’avanzare della criminalità organizzata che approfitterà “… per accamparsi sul deserto delle istituzioni.”

“La storia dei vinti è scritta dai vincitori… ci saranno verità che i conquistatori vorranno nascondere“. E così, prima dell’arrivo dei Savoia, Napoli godeva di un’ ottima consistenza finanziaria. Il banco di Napoli contava 443 milioni di lire rispetto ai 148 dei piemontesi; il 51 %degli operai italiani erano occupati nelle industrie del Sud, la pressione fiscale sui cittadini meridionali era la metà rispetto a quella esercitata sui piemontesi dai Savoia, le produzioni agricole detenevano il primato grazie alla fertilità delle terra, alla salubrità dell’acqua e al clima mite. Finirà lo splendore, famiglie costrette all’elemosina, il commercio quasi del tutto annullato; opifici privati costretti a chiudere a causa di insostenubli concorrenze: tutto proveniva dal Piemonte, dalla carta finanche alle cassette della posta, non vi era faccenda con non era disbrigata da uomini e donne piemontesi che si prenderanno cura dei trovatelli…”quasi neppur il sangue di questo popolo più fosse bello e salutevole.”

Lina Weertmuller

1 note

·

View note

Link

Genova: Teatro Carlo Felice Fu il Congresso di Genova del 4-9 ottobre 1949 ad indicare, nelle sue linee generali, il lavoro da svolgere nel settore stampa

0 notes