#stephan gladieu

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Stéphan Gladieu/National Geographic

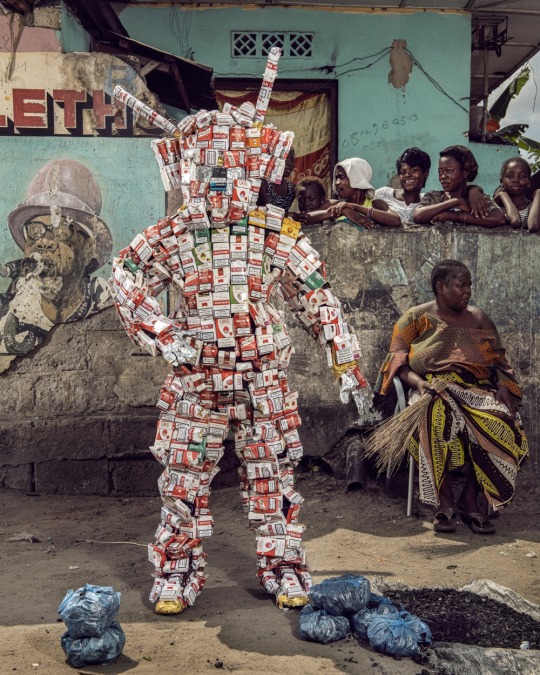

Congolese Artists Transform Garbage Into Garb To Take A Stand

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, artists’ creations protest the country’s plight as a dump for global waste. After years studying at the Academy of Fine Arts, Kinshasa — following teachers’ advice on creating work with “proper” materials, such as resin and plaster of paris — some students in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) decided to do something different.

#democratic republic of congo#artists#garbage#art#academy of fine arts - kinshasa#congolese artists#global waste#stephan gladieu

1 note

·

View note

Text

Maï-Maï warriors, Democratic Republic of the Congo, by Stephan Gladieu

#congolese#democratic republic of the congo#africa#central africa#folk clothing#traditional clothing#traditional fashion#cultural clothing

606 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WILL SMITH 📷 Stephan Gladieu

#will smith#wsmithedit#willsmithedit#mensource#dilfsource#flawlesscelebs#flawlessgentlemen#mancandykings#brunettessource#dcmultiverse#dccastedit#useryauch#usercelebs#userthing#dmenedit#by elena

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stephan Gladieu -

; Ouvrir dans un nouvel onglet

Stephan Gladieu egungun le culte des ancêtres ancester cult Benin yoruba stephangladieu.fr

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stephan Gladieu's portraits of Egun, a Yoruba cultural practice where "the family clans, exclusively male, summon Egun from the realm of the dead and take care of his needs on earth. Egun is the intermediary between this world and the souls beyond. He appears to certain families days after a death or during ceremonies to commemorate the deceased. He may also come to bestow the blessing of the ancestors on the marriages of their descendants or sometimes to welcome a newborn. His appearance is always accompanied by offerings of food, drink, and money. Egun speaks in a deep, hoarse voice and eagerly dances to the Bata or Ogbon drums. Contact with Egun’s loin-cloth can be fatal to the living, and the Mariwas, or guardians of the Egun society, armed with formidable engraved wooden canes (Ishan) take care to keep the foolhardy away. These canes symbolize the border between the world of the living and the realm of the dead (Ku-tome). The wind rustling through his loincloth as Egun whirls in dance is, however, beneficial."

In Africa, dead family members must be honoured. Because in many African cultures, death doesn’t exist, the spirit leaves the body to continue to live in the world of the dead, where the ancestors are. For the Yoruba, the dead reveal themselves to their descendants via an intermediary know as Egun. The spirit of the dead returns to earth in a striking loin- cloth of embroidered material decorated with shells, spangles, bone, and magic wood.

One mustn’t confuse the cult of the ancestors with the practice of Vodun. Vodun is a religion in its own right. Ancestor worship is an animist cult that is not directly related to vodun. The African cult of ancestors applies only to those family members within the dynastic line of the village or household’s founders. Royal families are an exception, as their members are often accorded divine status and thus enjoy a more prestigious lineage. This cult occupies itself with divinized ancestors and comprises a vast system uniting the living and dead in a familial, coherent whole. The gods and the dead mix with the living, hearing their complaints, giving counsel and blessings, and alleviating their distress and misfortunes. The heavenly realm is neither distant nor superior, and believers can directly address their gods and ancestors and take advantage of their benevolence. Each Yoruba clan honours its dead ancestors in the hope of eliciting protection and profit, avoiding their wrath, and banishing ghosts from the world of the living. Thus the spirit of the ancestor is regularly summoned from the world of the dead (Ku-tome).

Each family clan in the cult of ancestors has access to a sacred space where the masks of the ghosts are kept. Their adepts are educated in secret and don their ceremonial masks. For this task, the clan appoints certain members to be initiated and take on the responsibility of lending their bodies to the ancestral spirits, thus assuring dialogue with ancestors who have become protective deities. One or more members of the family are chosen, sometimes at a young age, to be messengers from the beyond. They follow secret training with fellow initiates that may last years, even decades. They learn the trance states that summon the gods to possess them, and the language of the invisible, they become their concrete form. They emerge as Egungun initiates. Only initiates know who the Egungun is, since during trances he appears masked, his body wholly disguised by the ceremonial garb.

This space or monastery is reserved for the initiated, exclusively man, under the pain of death. The monastery is directed by the Bale, typically the head of the family. The Alagba, or supreme leader, is the king of the village’s Egungun and keeps the monastery in order.

Masks

The garments worn by the ghosts are called masks. The shape of these masks, like the colour codes and symbols that compose them, are among the secrets of this society. I have not always been able to obtain precise information on how they are made and their symbolism. The masks are probably created in the monastery by families that specialize in mask fabrication. (I have yet to gain access to them). The original masks were made by weavers who made thick, colourful loincloths without trinkets. However, the Europeans obtained slaves in return for shards of glass, mirrors, and other trinkets that impacted the evolution of masks, sometimes even altering their shape.

According to the religion’s taboos, no one should see any part of the body of the person wearing a mask, because the spirit has no face. It is up to the oracle to transmit the wishes of the revenant to the one who will embody his spirit by wearing his mask. He will have to follow instructions in order to make it, or have it made by families specialized in their creation.

A mask costs between 400 and 8,000 euros. The material expense is not important, but it gives us two pieces of information: Masks are a reflection of the social class of the families that wear them. And also – of most significance, in my view – the cost of these masks indicates the enormous importance given to veneration of the ancestors.

Gaston Aniambossou told me the first day:

“You must do everything you can to make your papa come back one day and say hello.”

“He lived before me, I must honour him.”

And “My papa can not go out dressed in just anything.”

Yet Gaston probably earns less than 200 euros per month... But isn’t the important thing to be together, living alongside the ancestors?

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

week 3 photographers study 3

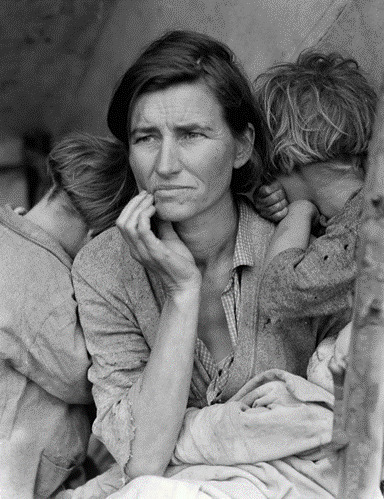

Dorothea Lange

With Dorothea Lange what draw my attention is the focus on the characters faces and the emotion that is portrayed. The first photo does really well with the mothers dark hair and only her face being visible.

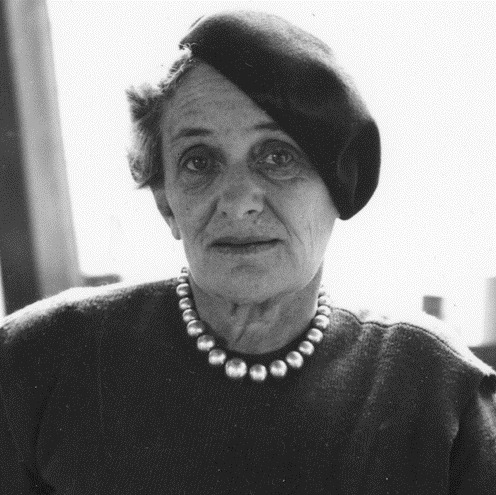

Jonathan Mannion

Jonothan Mannion is arguable one of my favorites in the photos I love the composition in the middle of the picture posing like the own the picture. And the second photo with the vibrant background and the silver jewelry matching it makes it come together so well.

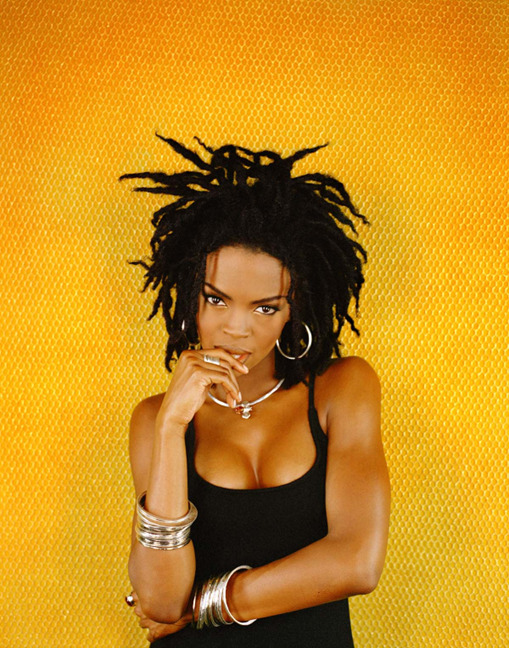

Stephan Gladieu

These photos are interesting because the first one has a lot of detail in the background and the pants blend into the bottom of the photo almost turning it into a mid shot portrait. The framing makes it almost look like two different photos merged. The second photo looks more along the lines of a club photo but the balls are nice I would’ve preferred the red in the middle but I’m not the photographer.

0 notes

Text

North Korea - Stephan Gladieu

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Egungun,” Sakété, Benin by Stephan Gladieu

#Egungun#egun#eggun#ancestors#Africa#Stephan Gladieu#African Traditional Religion#ATR#African Spirituality#spirituality#Black spirituality#Orisa#Orisha#Benin#Alagba Odje Lazard Adémola#Sakété

227 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Transforming Trash into Protest Art

The second largest country in Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo has one of the richest sub-soils in the world in gold, coltan, diamonds, cobalt, oil... and yet remains the 8th poorest country on the planet.

The Congolese are among the biggest losers of globalisation. They rarely benefit from the products manufactured with the resources drawn from their country. In general, these products reappear in Africa in the third or fourth generation; at best they are outdated, but more often than not, they are no more than the waste products of industrialised countries that prefer to relocate their processing.

The DRC is experiencing an ecological scandal, but just as an alchemist transforms lead into gold, "Ndaku, la vie est belle" was born from these tons of rubbish. It was founded six years ago in Kinshasa by the artist Eddy Ekete, and today it brings together nearly 25 artists, almost all of whom were trained at the Kinshasa Academy of Fine Arts.

Painters, singers, visual artists and musicians have joined forces to denounce the tragedy of their daily lives, the wars that have resulted from them, the exploitation of women and men that stems from them and ferments the unfathomable misery that robs them of their dignity.

Originally, these artists had in common that they had no resources, no support and that they lived in a shanty town in Kinshasa, built on land filled with tons of untreated waste. Naturally, they found an abundance of free raw material in these remains.

Mobile phones, plastic, corks, everything is raw material - and yet already industrialised! - to denounce the chaos in which the country is kept.

If Congo Kinshasa has partly lost its animist and mystic traditions under the pressure of Catholicism and colonisation, the artists of the collective "Ndaku, la vie est belle" return to the traditional source of the African mask.

Courtesy of Stephan Gladieu

#art#congo#DRC#trash#sustainability#equal rights#stephan gladieu#mask#africa#sustainable development#eddyekete#upcycling#recycling#streetart#human rights#ecology#fashion#costumes#kinshasa#globalisation#ndaku#poetry#hope

219 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stéphan Gladieu/National Geographic

Congolese Artists Transform Garbage Into Garb To Take A Stand

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, artists’ creations protest the country’s plight as a dump for global waste. After years studying at the Academy of Fine Arts, Kinshasa — following teachers’ advice on creating work with “proper” materials, such as resin and plaster of paris — some students in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) decided to do something different.

#democratic republic of congo#artists#art#congolese artists#garbage#global waste#academy of fine arts - kinshasa#stephan gladieu

1 note

·

View note

Text

Maï-Maï warriors, Democratic Republic of the Congo, by Stephan Gladieu

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If your name’s not down, you’re not going out.

33 notes

·

View notes