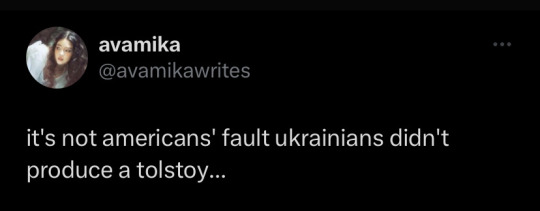

#soviet jails

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#stalinism#nkvd#soviet jails#Uman massacre#1941#soviet annexed polish lands#german invasion#russian imperialism#ukraine resistance#i stand with ukraine#slava ukraini#ukraine & poland

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Public Domain Tintin Day, everyone!!! ✨

Only very specific versions of these characters are free-range, just like Winnie the Pooh and Mickey Mouse - but our violently unhinged vodka-drinking Soviet convict isn't the only one to escape copyright jail this year! ⛓️💥

#tintin#the adventures of tintin#snowy#popeye#josie's art#(i drew the jailhouse at least lmao)#land of the soviets tintin is free to roam and that's going to be EVERYONE'S problem#bonkus of the conkus is highly contagious

361 notes

·

View notes

Text

My unpublished HP fanfictions don't even follow canon but it would be still considered transphobic and racist act to publish it to any place, eventhough most of my OCs are queer, diverse from many countries, and often not even humans. I don't even use canon characters or ships.

I can try and leave out the conservative british empire elements, even changing the worldbuilding entirely, it would still be considered transphobic and racist.

See how crazy this is?

Not because Harry Potter story is shit, it's because the author is doing horrible things to real people.

JK Rowling really ruined it for all of us. For those who are actually affected by her. For those who only just wanted a safe place to hide from reality.

Good people can make good art.

Good people can make shitty art.

Shitty people can make good art.

Shitty people can make shitty art.

People have got to get more comfortable with the fact that people with despicable moral values can create good art

"But Harry Potter was always shit-"

No. No it wasn't. It may have had its flaws, but people liked it for a reason. It was popular for a reason.

So many times people find out that the creator of something they liked was awful and then they go and claim that it was never good in the first place.

I think it's pretty dangerous to get into the mindset of horrible people can't create good things, because then you can't spot those people, or then you can use the fact that they obviously created something wonderful to deny that they've done anything wrong.

It's reductive. And it's dangerous.

#repcomm gets the same treatment from fans#my only luck is that I never was attached to HP characters#otherwise my grief would be much more deeper#but for repcomm...#well if you hate me for repcomm know that people always come and go but blorbos are eternal.#but I'm starting to doubt if Karen Traviss is really the monster people claim she is#given she wrote the first openy gay couple in SW written universe and now it's not even considered canon#First was actually a cathar jedi Juhani from KOTOR (2003) and Bioware still puts queer characters in SWTOR but that is also not canon#not just porthumously announced like JKR with Dumbledore and call it a day#you don't have power over the author so you yell with an average fan because this is the only control you have over the problem#and you won't go jail for it#living in a queerphobe rightwing aligned post-soviet country with dictatorship leaves me with a certain worldview I guess#my friends don't accept me. they tolerate me. I don't have patience for the first world's fictional problem bullshit.#shaming fans makes you believe you did something for the cause#but no. what you did is shaming one individual. while JK rowling still continue to support transphobic organizations#fandom activism don't help real people#At least I don't pretend that I'm doing a difference#i fucking hate couch-activists#... ejjj I've got really worked up haven't I?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

IWW Leader William D "Big Bill" Haywood, Mugshot Taken at the United States Penitentiary, Leavenworth, Kansas 1918

Big Bill Haywood, leader of the radical Industrial Workers of the World union, was arrested and tried, along with more than 100 other IWW members, for calling for international working class solidarity and urging young men to avoid the World War I draft. He was convicted to violating the Espionage Act and sentenced to serve 20 years in the prison at Leavenworth. Knowing he would not receive justice, he fled the country while he was out on bail during an appeals trial. He fled to the new, revolutionary Russian SFSR (predecessor to the USSR), where even though he was not a communist, he was greeted as a hero. He spent the brief remainder of his life in exile in Soviet Russia.

"You ask me why the IWW is not patriotic to the United States. If you were a bum without a blanket; if you had left your wife and kids when you went west for a job, and had never located them since; if your job had never kept you long enough in a place to qualify to vote; if you slept in a lousy, sour bunkhouse, and ate food just as rotten as they could give you and get by with it; if deputy sheriffs shot your cooking cans full of holes and spilled your grub on the ground; if your wages were lowered on you when the bosses thought they had you down…if every person who represented law and order and the nation beat you up, railroaded you to jail, and the good Christian people cheered and told them to go to it, how in hell do you expect a man to be patriotic? This war is a businessman's war and we don't see why we should go out and get shot in order to save the lovely state of affairs that we now enjoy." Big Bill Haywood, on IWW opposition to World War I.

68 notes

·

View notes

Note

Neil Gaiman: writes a book about a 7 year old raping her father to death

NG: writes a book where someone rapes a goddess for more power and fame

NG: writes a book where someone rapes their nanny

NG: literally provides funds to get someone with cp out of jail

Tumblr users: there were no signs!

He had more red flags than the Soviet Union.

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just letting you know the gfm you were working on met it’s goal and now has a new goal set

Yes! I wanted to wait until I got home so I could write something down about why supporting (and continuing to support) families through vetted fundraisers is so important—a lot of people have written compelling and incisive posts about why, but since many of of you have followed me for a while, I wanted to share a bit about my family’s experience and give some perspective that might encourage everyone to keep up the momentum.

185,000 Soviet Jews came to the United States between the 1970s and the 1990s. We were a kind of immigrant that’s known as a transmigrant, because we had to immigrate to several different countries before moving to the US permanently; since nobody could go to the US directly from the Soviet Union, we had to do it through a somewhat convoluted process called the Vienna-Rome pipeline.

My parents waited over ten years for an exit visa and were rejected several times, but were finally permitted to renounce their citizenship and leave Soviet Ukraine in the 1980s—there were three adults (my parents and grandmother) and two children (me and my older brother), all in good health. Things were a lot more relaxed in the Soviet Union by then, but my father had spent some time in jail for dissidence, so everyone involved in the process of obtaining the visas had to be bribed, and towards the end we were living in an communal apartment with eight other people to save money—that and because my parents were worried the Soviet authorities would find a pretext to arrest my father again (this had happened to our friends). When we got to the Odessa railway station (early in the morning, without saying goodbye to anybody, just in case), we were each allowed one suitcase, a very small sum of money, and our exit visa paperwork as identification.

We bought as little as possible on the train ride to Austria and only ate the cured meat my grandmother brought in her bag, but after two Soviet customs checks on the train, we couldn’t afford the tickets to Vienna, which was the entry point to the West, and where the Jewish relief services center was, and had to buy tickets for a station 40 kilometers outside of the city. When the train arrived, we stayed on board and were very quiet, and the ticket inspector either forgot us or showed us a small mercy by letting us stay. In Vienna, we lived in a migrant center (which, for us, was a hotel repurposed for migrant families) with other Soviet Jewish families while the JDC helped us put together our initial immigration applications to the United States, then made arrangements to get us to Rome so we could wait there for our various documents to get processed and approved, while applying for relief aid that would help us live from day-to-day in the meantime.

That was the most difficult part. We lived in migrant housing just outside Rome for 11 months. The Jewish relief aid services helped us out with almost everything—housing, groceries, social services, medical expenses—but it still wasn’t enough. When you have no steady income (and, as a sovereign citizen of nowhere at all, aren’t allowed to work), every expense is prohibitive, every setback is financially devastating. We got by because local churches gave us clothing, local students volunteered to teach us a little Italian—but when I got pneumonia (twice), when my mom needed another pair of dentures, when a translator who said he'd help streamline some paperwork took our money and disappeared, our case worker reached out to help us get sponsor families in America so they could help organize financial assistance (my dad would write to thank them in Russian because his English wasn’t very good, and their Russian friend would translate—we even got to meet one of the families when we moved here, and they’re still our close friends).

It was very fucking rough. By the time we were on the plane to America, I was pulling out my hair from stress, my grandma had developed a heart murmur, and we had almost nothing we brought from Odessa left in those suitcases.

Now read Bisan’s story. Or Mohammed’s. Or the stories of countless others. Tell me my family’s journey isn’t a fucking pleasure cruise compared to what they're facing. We fled political and religious persecution—but we weren’t sick, we weren’t starving, we weren’t being bombed, shot at, tortured, exterminated. The Jewish orgs helped us so much, but people—those American families and their friends—kept us going when we were waiting for faceless bureaucrats to approve our application to exist. And it didn’t stop when we got here, either. So many people kept on helping. They gave us money, time, referrals, opportunities, coached us through the process of getting naturalized.

As a matter of course, I donate to and platform fundraisers that are provided by a local mosque, and I probably won't be doing too many fundraising things like this on Tumblr because I don't (despite appearances) invest as much time and energy here as I do to my offline activism—but I want everyone to understand how important it is to support these families in addition to international relief organizations.

#we had a fundraising goal too and it increased as the situation kept changing and the situation kept changing all the time!#one of the things that helped us afford the plane tickets to nyc was the arrival of the holocaust reparations check from germany#your home. your uncles aunts and cousins. your mother. your fiance. your friends. your youth. $280 and you'll be fucking grateful.#anonymous#assbox

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the 1990s, the feel-good first decade after communism’s implosion, headlines in Central Europe were dominated by the likes of Vaclav Havel, the charming playwright-turned-Czech president who championed civic democracy. Yet, from the start, extreme-right rabble-rousers and brooding nativists lurked in the margins. Decades of Soviet rule had reinforced illiberal attitudes that surfaced in my discussions with ordinary people as I crisscrossed the region as a young correspondent, eventually writing a book about the far right in post-communist Central Europe.

At the time, I believed that Central Europe’s entry into the European Union, which was still far off and uncertain, would nullify the region’s most destructive tendencies. After all, the bloc had accomplished this for postwar Germany, Greece, Portugal, and Spain—all of which had emerged from radical dictatorships to become healthy democracies. Countries didn’t revert to despotism after acceding to the EU. Right?

But in Hungary the unthinkable happened: A state that jumped through all of the hoops to join the EU in 2004 commenced a rapid decline into authoritarianism just six years later. Other member states have endured stretches of democratic backsliding, including Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, and, notably, Poland during the 2015 to 2023 Law and Justice government. But their political systems and societies were resilient enough to fight back and depose strongmen. Hungary did not rise from the mat.

Two new books grant us vivid insight into Hungary’s descent into dictatorship—a feat pulled off so skillfully by Prime Minister Viktor Orban that it inspires awe—and uncover the mechanisms that made the regime’s rise possible, even as the undemocratic country has remained in a bloc designed to promote and deepen the liberal character of its members.

In Embedded Autocracy: Hungary in the European Union, Hungarian political scientists Andras Bozoki and Zoltan Fleck dissect the many-headed hydra of the Orban regime. Orban’s Hungary isn’t an old-school dictatorship that snatched power by a coup or jails opposition figures. As this astute book details, it possesses all the trappings of democracy, including regular, monitored elections; a multiparty opposition; and thus far, the peaceful transfer of power. Today, non-Fidesz mayors rule in the largest, western-most cities such as Budapest, Szeged, Pecs, and Gyor. For most Hungarians, this is evidence enough that their country is a democracy, regardless of the diagnosis of political scientists. This achievement is Orban’s magic, which relies not on spells but rather on the ruthless application of power.

Born in rural Hungary in 1963, Orban—a self-proclaimed “illiberal” politician—was once a liberal activist. He became an anti-communist student leader in the 1980s while studying law in Budapest and even took up a research fellowship at Oxford University on George Soros’s dime. Along with other activists, he founded the Alliance of Young Democrats (Fidesz) in 1988 as a Western-minded movement to promote freedom and democracy. (Bozóki was formerly a member of Fidesz but left the party in 1993.)

Orban has orchestrated every Fidesz twist and turn since, his keen populist instincts charting the course rather than any ideology. Between 1993 and 1994, he jerked the rudder to the right, and in 1998, Orban and Fidesz took the country’s highest office for the first time at the head of a center-right coalition. The Orban government, offering a taste of what the future held, stretched propriety to the limit by rallying the media to its cause, promoting loyalists in the state apparatus, and ingratiating itself with deep-pocketed bankers and industrialists.

In 2002, Orban committed a rare gaffe that resulted in defeat: playing more forcefully to the emerging middle class than to the much larger pool of older, uneducated, poor, rural voters—those ravaged by International Monetary Fund (IMF) and EU-driven market reforms. This group either shied from the polls or voted socialist left. It was not a mistake Orban would make twice.

Fidesz was out of office for the next eight years, and by the late aughts, Orban had transformed it from a conservative party to a populist vehicle that appealed not to a class but to a nation. He purged Fidesz of critical minds, centralized it around himself, and polarized Hungary’s discourse by casting political opponents as the nation’s enemies.

By 2010—six years after Hungary secured EU membership—Orban was raring to pounce. Bozoki and Fleck, though critical of Fidesz’s first turn at governance, argue that the descent into autocracy fell into place that year when Fidesz staged a spectacular comeback with a supermajority in parliament. Orban wasted no time in employing this mandate to hollow out the judiciary, rewrite Hungary’s legal code, and promulgate a new constitution. New laws made it harder for upstart parties to win seats and even easier for a large party, like Fidesz, to capture a legislative supermajority with less of the vote. And the refashioned legal code saw to it that Fidesz’s cronyism and subsequent amassing of power fell close enough within the law that it would not be sanctioned domestically.

Today, Hungary is a flourishing dictatorship. The regime has curtailed press freedom, marginalized the opposition, dismantled democratic checks and balances, controlled civil society, fixed election laws, and neutered criticism—ensuring that only extraordinary events, not elections, could oust it from power.

In Bozoki and Fleck’s telling, Orban’s genius was that he intuited exactly how Hungary was susceptible to this turn. The country possessed next to no democratic tradition before 1989. After the Soviets’ brutal crushing of the 1956 uprising, when Hungarians challenged the Stalinist regime, they fell in line again—in contrast to the Poles who fought communism’s enforcers tooth and nail. These “deep-seated attitudes” continued into the 21st century and contributed to Orban’s ability to entrench authoritarian rule.

“He could change the regime because society was not much concerned with the political system,” the authors write. “What people learned over decades and even centuries was that political regimes … were always external to people’s everyday lives.”

Rather than heavy-handed repression, Orban relied on self-censorship, suppliance, and patronage to keep his subjects in line. Those who toed the line were rewarded with jobs, directorships, and contracts. And, of course, he leaned on his own special cocktail of nationalist rhetoric: “He has provided identity props for a disintegrated society using tropes in line with historical tradition: a Christian bulwark against the colonialism of the West, the pre-eminent, oldest nation in the Carpathian basin, a nation of dominance, a self-defending nation surrounded by enemies,” the authors write.

Fidesz received a tremendous windfall in the aughts when the left-liberal government botched an economic transition based on neoliberal principles, rashly introducing free-market conditions to a society that was woefully unprepared for their fallout. The government created ever greater wealth disparities as it followed the “shock therapy” prescriptions of Western institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF, as well as the EU. In 2007, Hungary’s own debt crisis sent the country into a tailspin, a meltdown that the global economic crisis turbocharged the next year.

The socialist-liberal coalition of those years heaped blunders on top of blunders—such as the prime minister’s recorded admission that he lied to win the 2006 election—before crumbling. So thoroughly did the liberal partner in the coalition self-destruct that for a decade afterward, Hungary fielded no liberal party at all.

In the eyes of many Hungarians, the economic collapse discredited market capitalism, and liberal democracy with it. They understood it as one bundle that foreign actors had foisted upon them. Twenty years after democracy’s debut, the population welcomed a strongman who claimed to cater to “Hungarian interests” rather than those of elites in Brussels and Washington.

It is in the name of “national unification,” Fidesz’s blanket legitimation for nearly all of its reforms, that the party re-nationalized much of the industrial sector, as well as banking, media, and energy. Over the 2010s, Bozoki and Fleck write, Orban would decimate civil society and end “autonomy in public education, universities, science, professional bodies, and public law institutions.” Under these conditions, it is impossible to call any election free or fair, even if ballot boxes aren’t being stuffed.

Bozoki and Fleck’s fine book is buttressed by David Jancsics’s narrower Sociology of Corruption: Patterns of Illegal Association in Hungary, another work that understands egregious corruption as integral to the regime. At the book’s start, Jancsics, a Hungarian-born sociologist at San Diego State University, makes a simple observation: that corruption in Hungary today is on a scale unthinkable in the Soviet era.

This is quite a claim—in the 1990s, one of the most repeated reasons for Central Europe’s disgust with the Soviet system was its prevalent corruption. But the author backs it up. Although graft is still despised in Hungary today, because most people don’t benefit from it, Jancsics makes the case that it has once again been accepted as the way things are done.

Since 2010, Jancsics writes, “the Fidesz regime has effected a radical transformation of grand corruption patterns … in which complex corrupt networks are professionally designed and managed by the very top of the political elite.” Networks dominated by members of Orban’s inner circle now control not only political institutions, but also the economy, and “uninterruptedly siphon off a huge amount of public resources from the government system.”

These networks of Orban’s cronies and relatives are protected by a thick layer of shell companies that disguise the real owners of the businesses that profit from their proximity to government, Jancsics writes. And like the changes to Hungary’s political structure, the regime has fashioned laws to make its corruption legal.

Jancsics uses the example of the country’s $2.5 billion tobacco industry to illustrate this stripe of corruption. In 2012, the rubber-stamp Hungarian parliament passed a law that turned the sector into a state monopoly—purportedly to stop underage smoking—and decreed that all cigarette sales must occur under new concessions contracts. The government then created the national Tobacco Nonprofit Trade Company to oversee the distribution of new licenses. The company doled these out to members of networks close to the government. Two years later, another law passed stipulating that shops could only buy tobacco products from a state-owned intermediary. According to Jancsics, investigative journalists revealed that one person—Lorinc Meszaros, the then-mayor of Orban’s hometown—stood behind much of this scheme, which more than 500 shell companies helped obscure. Today, Meszaros is Hungary’s wealthiest man.

The crumbs of this hugely lucrative operation trickled down to lower-level party clientele. “It seems the legislators used the restructuring and reregulation of the whole tobacco market not only for the benefit of a few powerful oligarchs or proxy oligarchs but also for rewarding a large number of party clientele,” Jancsics writes. “Family members, spouses, siblings, parents, in-laws, friends, or even neighbors of people linked to the governing party won several concessions.”

The EU has not only watched this level of corruption unfold. As Bozoki and Fleck show, Brussels has been complicit in Hungary’s metamorphosis, supplying the funds to grease the regime’s operations. Like all of the EU’s Central European members, Hungary has profited immensely from EU cohesion funds, which are designed to bring the economies of weaker member states up to scratch. Between 2014 and 2020, Hungary received around $34 billion in EU funds, which Bozoki and Fleck argue has only solidified the ruling elite’s hold on power.

The EU finally got tougher in 2018, when it sanctioned Budapest for breaching the bloc’s core values. The following year, the European People’s Party, the European Parliament’s grouping of center-right parties, finally expelled Fidesz from its ranks. Over the past three years, the EU has frozen more than $31 billion to Hungary, including COVID-19 recovery funds, over rule of law deficits.

But this hasn’t forced Budapest to significantly modify any of its most flagrant abuses. Although there were loud objections from within the European Parliament, Hungary took over the rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union in July. Orban has continued to veto EU aid to Ukraine and increased its reliance on Russian fuels at a time when the bloc is striving to quit Russian imports. Perhaps more than any moves Hungary has made as council president, Orban’s friendliness to the Kremlin in exchange for cheap energy has weakened the EU as a foreign policy actor.

The EU is paying an enormous price for indulging Orban, not least by sanctioning a template for populist takeovers elsewhere in Europe. The bloc’s clout in terms of its ability to shape commerce, values, and policy coordination is obviously not as great as I once imagined. Hungary’s brazen disrespect and power plays have weakened it even further.

Now, the EU as we know it is under siege across Europe, where Orban allies hold or share power in the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, Slovakia, Austria, and Croatia. These rightists want an EU with fewer powers and less centralization—a Europe of nations—and many look to Hungary for leadership. Even U.S. President-elect Donald Trump pays homage to Orban, whom he has called “fantastic” and a “great leader.” These other pretenders will hopefully come and go—as ruling parties and their leaders do in democracies—but history teaches us that Hungary’s embedded autocracy will not disappear anytime soon.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nearly as soon as the Bolsheviks took power, they began to execute anarchists and Socialist Revolutionaries, most of whom had fought alongside the Bolsheviks in the Revolution. They also purged elements of their own party deemed "anti-Soviet" or "counter-revolutionary." This state repression was well documented by the Soviet government, but here we have chosen to use journals and letters of those affected. Lithuanian-American Jewish anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman describe the Bolshevik betrayal: The systematic man-hunt of anarchists [...] with the result that every prison and jail in Soviet Russia filled with our comrades, fully coincided in time and spirit with Lenin's speech at the Tenth Congress of the Russian Communist Party. On that occasion Lenin announced that the most merciless war must be declared against what he termed "the petty bourgeois anarchist elements" which, according to him, are developing even within the Communist Party [...] On the very day that Lenin made the above statement, numbers of anarchists were arrested all over the country, without the least cause or explanation. The conditions of their imprisonment are exceptionally vile and brutal. (Boni, 253)

#anti-bolshevism#anti-leninist#anarchism#anti tankie action#crimethinc#emma goldman#alexander berkman#communism#marxism leninism

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

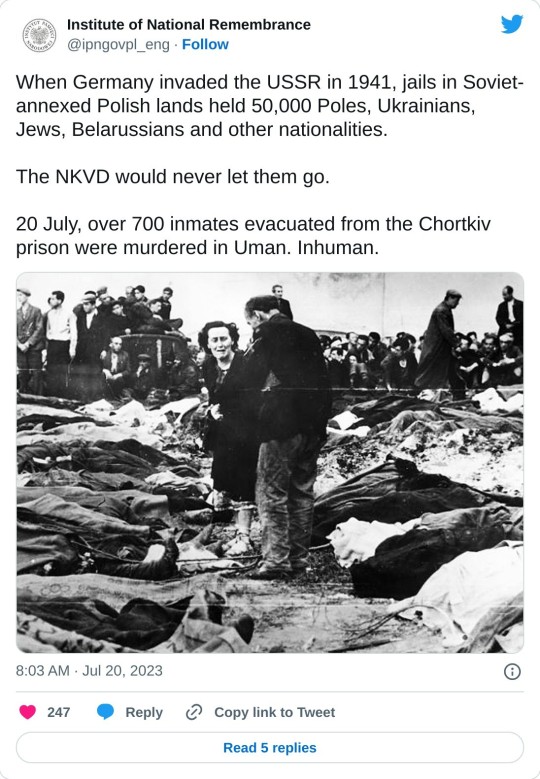

Why Ukrainians didn’t produce a Tolstoy?

there are a lot of things that can piss me off, today it was this tweet:

and all i wanted to do was to ask this person, why the fuck do we need a racist misogynistic piece of shit as a standout author if we have Shevchenko as our prophet?

but you don’t know who he is? of course, you don’t. that is the thing with imperialism: you destroy other cultures while promoting yours as the only way to legitimise your rule. even if those territories are of higher cultural development. but there is always a way out of it: kill them all. kill anyone who poses an existential threat to your hegemony. throw them into jail. forbid them to write and paint. send them to gulag. kill them. torture them. execute them.

if you don’t know Ukrainian literature, it doesn’t mean that it‘s nonexistent. if you don’t know "a Ukrainian Tolstoy", it means there is a Ukrainian Bahrianyi, who was sent to the gulag but ran away and was the first person in the world to openly criticise USSR in his pamphlet Why I am not going back to the Soviet Union. "I don't want to go back to the USSR because a person there is worth less than an insect"

there is a Ukrainian Symonenko and a Ukrainian Stus. there is a Ukrainian Lesya Ukrainka and Olha Kobylyanska. a Ukrainian Kotsiubynskyi, Ukrainian Drach, Ukrainian Olena Pchilka and Ukrainian Lina Kostenko. and so many more of the bravest people who despite all wrote in the Ukrainian language about Ukrainian people and for Ukrainian people.

there are thousands of beautiful texts that weren’t translated because this would’ve harmed the empire. that is why you are reading Dostoevsky and not Khvyliovyi.

but there are also thousands of texts that were never written. just how many more poems would’ve Stus written if he wasn’t killed by the Soviet regime? how many more texts would have Pidmohylnyi, Semenko, Yalovyi, Yohansen, Zerov written if they weren’t shot at Sandarmokh?

just how many texts have the world missed out on because Khvyliovyi committed suicide as he couldn’t live in the world with Stalin’s repressions. "today is a beautiful sunny day. I love life - you can't even imagine how much", - he will write in his death note as he shot himself with his friends waiting for him in the next room.

or maybe there was a Ukrainian Nobel Prize in Literature waiting for Tychyna? maybe, but he submitted to Soviet authorities and started writing hails for the regime, suddenly forgetting his own literary style and living his entire life in fear. fear of what? fear of getting caught. of getting destroyed just as all of the previous Ukrainian intelligentsia.

I’m tired of my people being silenced. I’m tired of my poets being undermined by "great” russian literature. it’s not worth a single Symonenko’s poem. it’s not worth a single paragraph of Bahrianyi‘s prose.

the greatness of russian literature lies on the bones of Ukrainian writers. to be this high, they killed hundreds and they are still doing it today.

the body of Ukrainian children’s writer Volodymyr Vakulenko was found in the mass grave in Izium in September 2022.

there will be a Ukrainian Nobel Prize in Literature, and there will be more Ukrainian books. there will be Ukrainian Zhadan and Zabuzhko, Liubka and Izdryk, Deresh and Kidruk. there will be Ukrainian literature.

another funny thing is that this person is Indian and let me tell you: the fact that you stand up for one empire even when your own country has suffered from the doings of another is evidence of deep colonial trauma and I hope you will cure yourself soon

577 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the olden times, before the internet, there was no other choice. If you were into something weird, and wanted to meet other weird people, you'd join a club. Sure, sometimes the club was through the mail, but that was the model for humanity for thousands of years. Then the bulletin-board systems showed up, and then we screamed at each other in all-caps.

Even with the aggressive push to move all communication online, car clubs are still going strong. This is mostly because it is difficult to drive your car on the internet (broadband isn't good enough yet.) You can take your car, and drive it in a parade, or to an ice cream place, or to another member's home in order to help fix their car. Don't worry, there is still lots of time for bullshitting, grousing, and development of strange little grudges on the internet afterward.

I joined a local Mopar club many years ago, in the hope that I would find another Volare enthusiast. Barring that, maybe one of those poor deluded fools with an Aspen. It never happened, possibly because my backyard was already full of an obscene hoard of several dozen of those cars, removing them from circulation for anyone else. Still, I found some camaraderie there, and every so often we got to bail one of the other members out of jail after getting busted for street racing.

Yes, street racing. Although every car club will tell you that they are not a dangerous street-racing gang, the menace of the innocent, a lot of the local ones do seem to happen awfully close to a big long stretch of straight road. Perhaps it's simply bad urban planning that has produced a city consisting nearly entirely of two-lane roads separated by stop lights approximately one quarter mile apart.

Personally, I would never engage in such reckless behaviour. It would imperil the legal existence of the club to get caught. And also the police don't believe me that my wheezing lawn ornament, seeping vital fluids from every hose and gasket, powered by a Soviet hit-and-miss engine out of an industrial plant, could achieve the speed limit, much less anything faster. Still, there is hope. If the cops accidentally rear-end me while trying to chase someone else in the club, they'll have to pull over in order to yank the chunks of my trunk out of their radiator. They'll get away scot free.

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

About a hundred Finnish Russians gathered at a pro-Ukraine, anti-war rally in Helsinki on Sunday 17th November 2024. They began the demonstration at the Kansalaistori Square and marched to the Russian Embassy, calling out "Victory for Ukraine! Jail Putin! Freedom for political prisoners!" At the embassy, they demanded immediate withdrawal of Russian forces from Ukraine and freedom for political prisoners.

Comments given to Yle:

"I came from Forssa because it's important to oppose the war. Everyone who can should be here." - Aleksandr Nesterov

"I want to show that Russians who oppose the war exist, and to meet others who think alike." - Nikolai Kutšumov

"I also want to show the people in Russia, that they are not alone. Even though they cannot take to the streets now and speak freely, we will instead. Our goal is a free Russia and the freedom of political prisoners. The prisoners are kept in horrific conditions and are tortured. This should not happen in the 21st century." - Darja Drobysheva

"We greatly wish that the Western nations continue actively supporting Ukraine regardless of what the United States does. It will save peace in Europe. We completely agree with the Ukrainians when they say support Ukraine, save peace in Europe." - Irina Vesikko

Full article by Yle in Finnish

Apart from the white-blue-white Russian anti-war flag and the Ukrainian flag, there is also an Ingrian Nordic cross flag. Ingria is the name of the area between Estonia and the Karelian Isthmus (St. Petersburg is located in Ingria). It is the homeland of the Izhorians, Votians, and Ingrian Finns. The Izhorians and Votians are the native residents of the land and Ingrian Finns are the descendants of Finnish immigrants introduced into the area in the 17th century.

Both Ingrian Finnish and Izhorian populations all but disappeared from Ingria during the Soviet period. 63,000 fled to Finland during World War II, and were required back by Stalin after the war. Most became victims of Soviet population transfers and many were executed as "enemies of the people".

From the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 until 2010, about 25,000 Ingrian Finns moved from Russia and Estonia to Finland, where they were eligible for automatic residence permits under the Finnish Law of Return.

#stand with ukraine#russian war on ukraine#russia is a terrorist state#ukraine#russia#finland#ingria#suomi#venäjä#inkeri#*

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The story goes like this

Earth is captured by a technocapital singularity as renaissance rationalitization and oceanic whoops sorry, wrong script

The story goes like this: during the Cold War, the USSR pumped vast amounts of resources to recruit sympathetic people as agents to attack and subvert the US government. Didn't hurt that FDR was largely sympathetic to Stalin. The early wave resulted in the Soviets getting important military plans, e.g. for the nuclear bomb.

This infiltration was an actual thing that happened. This is worth reiterating, because people often claim that McCarthy was fighting against nonexistent enemies. Because people in Hollywood were often captivated by the ideas of communism, as artistic types often do, in retaliation they vilified him forever in popular culture. (Although it's worth noting that he probably was an abrasive person, so that didn't help).

By the 70s, there were multiple active leftist terrorist organizations in the US. And we're not talking about some 21st century "riot around, semi-accidentally set fire to some buildings, is you kill a guy it makes national news" weaksauce. No, it was

The 1970s underground wasn’t small. It was hundreds of people becoming urban guerrillas. Bombing buildings: the Pentagon, the Capitol, courthouses, restaurants, corporations. Robbing banks. Assassinating police. People really thought that revolution was imminent, and thought violence would bring it about. [...] Most ’70s of the bombings were done as protest actions. Unlike today’s jihadists, ’70s underground didn’t try to max body count. And ’70s papers didn’t really give a shit. A Puerto Rican group bombed 2 theaters in the Bronx, injuring eleven, in 1970. NYT gave it 6 paragraphs.

(Source. I really should finally read that book.)

The endeavors at this scale can't be backed by revolutionary fervor alone. You need logistics, you need financing, you need friendly lawyers. Weather Underground (originally Weatherman, but that -man suffix was deemed sexist. Plus ça change) sprung out from a socialist student organization.

By the time the USSR fell, the radical organizations have metastasized into vast patronage networks. Many became academics, lawyers. In some cases it was almost dynastic - remember Chesa Boudin, a New York DA? His father was a Weatherman, in jail for felony murder. He was pardoned by Cuomo in 2021.

There were more pardons. Some made by Bill Clinton. Some made by Obama. Remember back 10 years ago, when Hamilton was the Apex of lib culture. Lin-Manual Miranda took care to reserve seats for FALN bombers.

The last link goes to David Hines' twitter. There's another drum he's been banging repeatedly: righties don't know how to organize and cargo-cult it. They see all the successful actions of the left and assume that they just happen, ignoring the fact that, again - those require logistics, money, and backing of a sympathetic press and lawyers. Instead of building a network and then utilizing it, they start from shouting their intent publicly then beclown themselves.

But what if that was the case because the left had a multi-decade headstart in networking, due to support from a now-dead rival empire? What if the patronage networks built over multiple generations were suddenly broken? What if they were growing unopposed by the neocons, who happily let them be as long as the Republicans got to bomb some brown people while in power during the 90s and 00s?

If this was true, then the current upheaval would mean that the current victory of the radical MAGA wing was a fluke, but that it also was a victory made in an insanely uphill battle. It would mean that if the existing patronages are broken, going forward you'd need much less activation energy to win. That hundreds of little things that tipped the scales in one direction would just... cease.

It's hard to be surprised that some people are getting downright giddy these days. Sure, the networks are embedded so deeply that it takes a lot of collateral damage to rip them, but can you imagine, for the first time in your life, an actual victory?

-------------------------------------

Well, that's a story. I mean, the in-between points are real: the Rosenbergs are real, all the bombings in the 70s are real, the pardons of those are real. But weaving the common thread through them, that's a story one may tell. Every political faction has a story that they like to tell about themselves. This one's may not even be the story that most MAGAs tell themselves, many are probably perfectly content with torching the commons to own the libs.

But I think that this is approximately the story many people would tell about the past two weeks. ESR, Travis Corcoran, the aforementioned Hradzka. Eigen.

And I think that it's important to understand the stories people tell about themselves and their beliefs, even if you don't believe them.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

LISTEN. Listen.

I was born in Russia, a country whose democracy was virtually eliminated, not in 4 years, not in 5, but by gradually, slowly stripping people of their rights to speak out and leaving every institution rotten and corrupted. The entire time I've been alive, Putin has been in power. 24 years. I'm 18. Me and my mother wouldn't be able to escape now if she didn't have enough foresight to leave the country before things went to shit completely. Many times I've wondered what would I be had we stayed. "I'd probably kill myself, haha", that's what I often said. But now, I'm thinking of all the young people, of all the queer people, of all the good people who have to wake up to a hopeless landscape of fascism in front of them. How they still live. Live, though they can't speak out, not even on internet. Live, even though they can go to jail for wearing a rainbow bracelet. How I never thought about them enough, because "oh, it's not my country anymore!".Please. Promise me to be loud. Promise you'll fight like your life depends on this. Russians allowed this to happen because they had zero political consciousness after almost a century spent under soviet oppression. But you are supposed to be a country of freedom. Try to live up to the title. Bite and scratch if you have to in order to defend it. Because maybe one of these days some transgender kid from Novosibirsk will look at you and feel hope. Hope that some things in this world can be saved after all.

#us politics#election 2024#donald trump#kamala harris#russia#adding my fifty cents#i love all of you. stay strong#i know i don't normally post politics but this shit's serious

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

When strikes occur in the American zone of South Korea, one of the workers’ demands is usually for a Labor Code like that in the Soviet zone of North Korea. This naturally annoys the American Military Government, which sees in such strikes the work of the Communists. The demand, however, raises the question: What are the labor conditions in North Korea? All the industrial workers I met in North Korea like to brag that they were the first workers in the Far East to enjoy a “fully modern labor law, with the eight-hour day, collective bargaining and social insurance.” Their claim is not strictly correct for the Liberated Areas of China and Manchuria just over their border have an equally good labor code. Nonetheless the North Koreans have the right to feel proud of their achievements. In one respect they can claim to surpass their Chinese brothers – their well-equipped social insurance. The Japanese had more health resorts and summer villas in Korea than in China and the present Department of Labor has taken them over. The North Koreans have also a larger amount of publicly owned industry than the nearby Chinese, for Korea was highly industrialized by the Japanese. Minister of Labor Oh Ki-sup, with whom I went on a four-day trip to health resorts, is one of those typical patriots who spent the greater part of his adult life in Japanese jails. At the age of sixteen he joined the underground movement for Korean independence. He has spent thirteen years and eight months in jail. In telling about his imprisonment he mentioned casually what seemed to me its most amazing feature. He had organized four revolutionary study circles inside four different jails and one outside at a time when he was in “solitary” confinement! Minister Oh’s account of how he did it throws sharp light on the inner weakness of imperialism. The facade of Japanese control seemed imposing and strong, but there were weak places in it ready to crack. The night watchmen and night warders in the jails were Koreans, because the Japanese conquerors disdained these least desirable jobs. Prisoner Oh played upon the patriotism and also upon the cupidity of these jailers. He would find some watchman who would take messages to his friends outside, either through anti-Japanese patriotism or for the money the outside friends would give. On this slender basis Oh built his study groups, one in each of the jails to which he was transferred. In all of this time Prisoner Oh was never permitted legally to have a pencil or a scrap of paper. He saved bits of toilet paper – of which he was allowed two pieces a day – and he had a tiny sliver of hidden lead that served as a pencil. Through such difficulties the revolutionary movement of the Korean patriots grew. Prisoner Oh managed to organize illegally right up to the day of national liberation. As soon as the Red Army arrived and liberated Oh and the other political prisoners, the liberated men hastened to the factories and workshops where they were known – others of course were hurrying to the farms – and called workers’ meetings. These workers’ meetings at once took part in setting up city and provincial government; they also organized trade unions, first by factories, then by cities, counties and provinces.

In North Korea: First Eye-Witness Report, Anna Louise Strong, 1949

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

...it was odd to hear the Soviet director, Colonel Lazarev, insisting that both prisoners were dominated by Rudolf Hess. 'He terrorizes them,' said the Russian. They did exactly what Hess - 'a mean and sneaky person' wanted them to do. Hess made a practice of 'devouring all the garden strawberries while his companions did the work', said Colonel Lazarev, 'swallowed them without even washing them.'

About Baldur von Schirach, Albert Speer, and Rudolf Hess in Spandau Prison.

Excerpt from Prisoner #7, Rudolf Hess : the thirty years in jail of Hitler's deputy Führer - by Eugene K. Bird, 1974,

#rudolf hess#baldur von schirach#albert speer#hess#von schirach#speer#prisoner number 7#eugene k bird#book excerpt#i am trying not to lose my Shit#reichblr

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

5 head cannons if NASA was sent to Star City for the Apollo-Soyuz (or in this case Soyuz-Apollo) mission.

OMG THE POTENTIAL OF THIS AU!

Margo is sent to Star City with two competing objectives: Tom Paine wants this to happen; Nelson Bradford would rather it didn't. And, quite frankly, Margo agrees with Bradford. So she handpicks a team full of the most stubborn people she knows to make all of this not happen. Molly is chugging whiskey on the plane ride. Aleida is ignoring Margo and barely saying a word. Perfect.

There is no brass band. Just softly falling snow as Margo descends the plane. Introductions are made. Looks are exchanged between the KGB agents hovering in the background and the CIA who would look out of place in Langley. As they head for the cars to take them to Star City, Margo slips on a patch of ice. She's caught by the head of the Apollo-Soyuz program, who holds her closer than she expects.

The first meeting is a disaster. As intended. Margo challenges everything that Sergei Orestovich Nikulov presents in an effort not to allow the Soviets access to their technology. She doesn't need to skim through the battered phrase book in her bag that the meeting is a bust. She almost feels bad for Nikulov. Almost. But he's cold, and detached, and he'll no doubt find something else to do.

He turns up at her hotel. The CIA agent guarding the door is in the bar and he's there, waiting for her. We need to make this happen, Margo. Please. Meet me here in one hour. Do not eat before you come. Margo is half-expecting to end up in a Soviet jail. She does not expect to find herself at the Nikulov family dinner, with good food and challenging board games and the heady laugh of one Sergei Nikulov.

They make their plans in Margo's hotel room, with Margo stealing Aleida from the hostel they'd stashed her in. Sergei is the one to present their plans for Apollo-Soyuz; Sergei is the one who gets the credit. Margo accepts a box of Russian sugar cookies as a thank you for letting him save face. They eat them, later, in her hotel bed as the sheets cool around them.

Send me a Margo/Sergei AU (either one I’ve mentioned before, created a gifset of, or one of your own devising) and I’ll give you 5 headcanons!

20 notes

·

View notes