#sometimes poverty or other things factor in

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Learning another language is another one!

#do what you can okay??#like eating healthy it's not something you can magically just do#sometimes poverty or other things factor in#it's easy to say don't eat just pasta every day if that cheap pasta is all you can afford#there are LOTS AND LOTS of free ebooks out there if you can't afford to get to a library#lots of language learning apps#or free language courses online#if you have a streaming service try seeing what other audio/subs they have#learn things by watching youtube documentaries or tutorials#a little bit a day is enough#health#mental health#brain health

24K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello!

I've seen you talk a few times about the dangers of over-warding, which I can certainly see the sense in; at the same time, wards can also certainly be useful things. I'd like to ask you: in your opinion, what is the most sensible amount of wards to have? Does it make sense to ward (oneself, one's home, whatever) at all if you don't have a reason to expect attacks or infringements?

Good morning!

We're at least in reference to this post.

The silly answer is, but I promise to explain it so that it's useful, the most sensible amount of wards to have is however many cover your needs.

I think the topic of warding is often framed in relation to attacks and retaliation, which it certainly relates to. But I think that also gives it a bit of a crusty patina, if you will: "I don't have main character syndrome; I'm not one of those witches who's so paranoid that everyone is going to attack them, and I don't mess around with spirits, so warding isn't for people like me."

Which is all well and good, but the idea of warding in and of itself is that it's just a barrier that stops things from coming through.

Wards can hypothetically block out anything: malifica and spirits, sure, but also unwanted guests, solicitors, debts, poverty, stress, illness, spam phone calls, and spiders.

"Attacks" may not be common, but tangles of unhelpful energy, the Evil Eye, and blustery storms of ill-effect aren't all that rare. Just because someone didn't aim at you and pull the trigger doesn't mean that your life will remain void of deleterious energies.

Spirits living their lives will infringe on you, not because you're the main character or because they're malicious, but because the two of you live in the same reality and sometimes your lives intersect in unwanted ways.

And you can accidentally infringe, and then spirits can be offended and decided to make it your problem.

So in a certain sense, not having wards because you don't expect attacks or infringements is like not having house rules because you don't expect your room mates to ever do anything upsetting:

On the one hand, it's perfectly fine to wait until something is happening before you deal with it.

On the other hand, some people prefer to say, "welcome to the house! Please don't invite your friends to stay the night without checking with us first."

Another confounding factor is whether or not you tend to draw spirits to you, as some people do; and whether or not you live in an area with very high spiritual activity. If you live in a paranormal activity desert, baseline wards might not be useful at all, whereas someone who has sensitive psychic perception and lives in an old converted mortuary might need lots of baseline protection just to feel comfortable.

But perhaps the most important deciding factor is whether or not you want to deal with it.

Early on in my education I heard a witch of great experience say, "the more experienced you get, the less wards you need. You get to a point where you can just deal with things as they arise instead of needing to stay walled in all the time."

Which is technically true. However they may manifest on the astral plane, the functional effect of a ward is like a bug screen: it's likely to stop or mitigate whatever it's meant to hold out.

The real question then becomes, what things would you prefer to never deal with, and what things are you comfortable dealing with as they arise?

Wards should be for that - the things that you would just like to not ever have to deal with, even if you don't particularly expect them to darken your doorstep.

Wards can be useful because they are proactive and preventative. A ward to stop bad energies and stress from your workplace following you home can help reduce the need for more regular spiritual hygiene. A ward against uninvited spirits can help stop you from getting distracted from the magical work you actually want to be doing.

So a ward is like a wall. Does it make sense to build a wall around your farm, even if you never expect a raid from the neighbors?

I don't expect raids from my neighbors. I still build walls.

88 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think the Yotsuba members thought of Kira before they got personally involved? Were any of them pro Kira?

ooh, good question.

higuchi, at least, was almost definitely pro-kira. in chapter 38 of the manga, he very explicitly says he wants to continue killing criminals. he points out white collar criminals specifically because they damage the economy, but he also talks about kira in terms of his mission to create a peaceful world, going so far as to say that everyone who wasn't a criminal wanted kira to return during his absence. this seems like a reflection of his own beliefs more than anything else: higuchi believes kira is building a peaceful world and wants kira to exist, even if it isn't him. but he was chosen to become kira, so it's not surprising that he'd support the original. rem probably wouldn't have chosen him if he was anti-kira.

other than higuchi, the most indicative lines here, i think, are from chapter 37:

Unseen Yotsuba Guy 1: Having Kira kill off criminals sure is something to be thankful for... Unseen Yotsuba Guy 2: Exactly, especially thieves. Nice for us rich folk not to have to worry about that as much.

we don't actually see who's talking, but we know at least two of the yotsubas are openly pro-kira. personally, i tend to pin these two down as hatori and ooi. "us rich folk" just sounds like an ooi line, and the first line just fits best with hatori's speaking patterns and attitudes, imo. after all, he's the one who talks about how great it is that one of their members is using kira's powers to benefit their group. i feel like this is partially posturing, but it's in a "trying to be strategic" way rather than just being dishonest.

but it makes sense for some of the yotsubas to support kira, after all. they're are a bunch of rich guys; most of them have never had to live in poverty, and i don't think they have much empathy for the those who do, so they're not really compelled to care about the socioeconomic factors that force people into crime. besides, laws tend to benefit the rich, so of course they want those laws enforced. even if they don't really care about peace and love etc., they still want to protect their own interests. and, as we can see, many of them don't mind if blood has to be spilled along the way, so kira's extreme methods wouldn't bother them too much as long as he's only killing off people who they can label as Bad. means justify the ends and all that.

so yeah, higuchi, ooi, and hatori belong in the pro-kira category, imo, although they probably wouldn't say so out loud since supporting kira pre-time skip wasn't super socially acceptable. i think kida would also feel this way for all the reasons described above, although killing his own (as in: other executives) doesn't sit well with him, even if he disguises it. namikawa also seems like someone who would support kira from a pragmatic angle, but i don't think he's that concerned with good and evil; it's more a case of "society functions better this way, and that's good for me". he's completely silent about that, though, and he probably looks down on your run-of-the-mill kira worshiper for being naive and... obnoxiously stupid is the best way to put it, i guess?

takahashi is conflicted. i think his knee-jerk response is just "killing people is bad", but he sometimes wonders if maybe it's for the best. sort of similar to matsuda, except without being as entangled in the conflict as matsuda is. his own personal involvement with kira turns him firmly against kira in the end, though. for what it's worth, i think kida also starts to question his previous stance on kira over the course of the meetings of death, but by that point he has more pressing things to worry about.

shimura and mido strike me as anti-kira. in shimura's case, i think he has a hard stance against killing people for any purpose, and he recognizes that simply killing criminals doesn't solve the circumstances that cause crime. mido, on the other hand, is more concerned with the implications that One Guy With The Power To Kill Anyone Without Repercussion has on democracy in the long-term, although she's kind of resigned to it as just... an absurd thing that's happening whether anyone likes it or not, oh well, she'll be fine regardless. haha, whoops.

but yeah, honestly, i don't think most of them care enough to start workplace discussions about kira, especially considering how polarizing it is and how outside the mainstream public support for kira is. when kira does come up before higuchi gets the death note, it's probably something along the lines of... takahashi mentions the most recent kira headline in passing, everyone sighs and looks uncomfortable, maybe kida or hatori or someone says something short and bland, namikawa changes the topic.

#asks#Yotsuba#Kyosuke Higuchi#Arayoshi Hatori#Takeshi Ooi#Masahiko Kida#Reiji Namikawa#Eiichi Takahashi#Suguru Shimura#Shingo Mido#anonymous

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: James B. Meigs

Published: Spring 2024

Michael Shermer got his first clue that things were changing at Scientific American in late 2018. The author had been writing his “Skeptic” column for the magazine since 2001. His monthly essays, aimed at an audience of both scientists and laymen, championed the scientific method, defended the need for evidence-based debate, and explored how cognitive and ideological biases can derail the search for truth. Shermer’s role models included two twentieth-century thinkers who, like him, relished explaining science to the public: Carl Sagan, the ebullient astronomer and TV commentator; and evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould, who wrote a popular monthly column in Natural History magazine for 25 years. Shermer hoped someday to match Gould’s record of producing 300 consecutive columns. That goal would elude him.

In continuous publication since 1845, Scientific American is the country’s leading mainstream science magazine. Authors published in its pages have included Albert Einstein, Francis Crick, Jonas Salk, and J. Robert Oppenheimer—some 200 Nobel Prize winners in all. SciAm, as many readers call it, had long encouraged its authors to challenge established viewpoints. In the mid-twentieth century, for example, the magazine published a series of articles building the case for the then-radical concept of plate tectonics. In the twenty-first century, however, American scientific media, including Scientific American, began to slip into lockstep with progressive beliefs. Suddenly, certain orthodoxies—especially concerning race, gender, or climate—couldn’t be questioned.

“I started to see the writing on the wall toward the end of my run there,” Shermer told me. “I saw I was being slowly nudged away from certain topics.” One month, he submitted a column about the “fallacy of excluded exceptions,” a common logical error in which people perceive a pattern of causal links between factors but ignore counterexamples that don’t fit the pattern. In the story, Shermer debunked the myth of the “horror-film curse,” which asserts that bad luck tends to haunt actors who appear in scary movies. (The actors in most horror films survive unscathed, he noted, while bad luck sometimes strikes the casts of non-scary movies as well.) Shermer also wanted to include a serious example: the common belief that sexually abused children grow up to become abusers in turn. He cited evidence that “most sexually abused children do not grow up to abuse their own children” and that “most abusive parents were not abused as children.” And he observed how damaging this stereotype could be to abuse survivors; statistical clarity is all the more vital in such delicate cases, he argued. But Shermer’s editor at the magazine wasn’t having it. To the editor, Shermer’s effort to correct a common misconception might be read as downplaying the seriousness of abuse. Even raising the topic might be too traumatic for victims.

The following month, Shermer submitted a column discussing ways that discrimination against racial minorities, gays, and other groups has diminished (while acknowledging the need for continued progress). Here, Shermer ran into the same wall that Better Angels of Our Nature author Steven Pinker and other scientific optimists have faced. For progressives, admitting that any problem—racism, pollution, poverty—has improved means surrendering the rhetorical high ground. “They are committed to the idea that there is no cumulative progress,” Shermer says, and they angrily resist efforts to track the true prevalence, or the “base rate,” of a problem. Saying that “everything is wonderful and everyone should stop whining doesn’t really work,” his editor objected.

Shermer dug his grave deeper by quoting Manhattan Institute fellow Heather Mac Donald and The Coddling of the American Mind authors Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, who argue that the rise of identity-group politics undermines the goal of equal rights for all. Shermer wrote that intersectional theory, which lumps individuals into aggregate identity groups based on race, sex, and other immutable characteristics, “is a perverse inversion” of Martin Luther King’s dream of a color-blind society. For Shermer’s editors, apparently, this was the last straw. The column was killed and Shermer’s contract terminated. Apparently, SciAm no longer had the ideological bandwidth to publish such a heterodox thinker.

American journalism has never been very good at covering science. In fact, the mainstream press is generally a cheap date when it comes to stories about alternative medicine, UFO sightings, pop psychology, or various forms of junk science. For many years, that was one factor that made Scientific American’s rigorous reporting so vital. The New York Times, National Geographic, Smithsonian, and a few other mainstream publications also produced top-notch science coverage. Peer-reviewed academic journals aimed at specialists met a higher standard still. But over the past decade or so, the quality of science journalism—even at the top publications—has declined in a new and alarming way. Today’s journalistic failings don’t owe simply to lazy reporting or a weakness for sensationalism but to a sweeping and increasingly pervasive worldview.

It is hard to put a single name on this sprawling ideology. It has its roots both in radical 1960s critiques of capitalism and in the late-twentieth-century postmodern movement that sought to “problematize” notions of objective truth. Critical race theory, which sees structural racism as the grand organizing principle of our society, is one branch. Queer studies, which seeks to “deconstruct” traditional norms of family, sex, and gender, is another. Critics of this worldview sometimes call it “identity politics”; supporters prefer the term “intersectionality.” In managerial settings, the doctrine lives under the label of diversity, equity, and inclusion, or DEI: a set of policies that sound anodyne—but in practice, are anything but.

This dogma sees Western values, and the United States in particular, as uniquely pernicious forces in world history. And, as exemplified by the anticapitalist tirades of climate activist Greta Thunberg, the movement features a deep eco-pessimism buoyed only by the distant hope of a collectivist green utopia.

The DEI worldview took over our institutions slowly, then all at once. Many on the left, especially journalists, saw Donald Trump’s election in 2016 as an existential threat that necessitated dropping the guardrails of balance and objectivity. Then, in early 2020, Covid lockdowns put American society under unbearable pressure. Finally, in May 2020, George Floyd’s death under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer provided the spark. Protesters exploded onto the streets. Every institution, from coffeehouses to Fortune 500 companies, felt compelled to demonstrate its commitment to the new “antiracist” ethos. In an already polarized environment, most media outlets lunged further left. Centrists—including New York Times opinion editor James Bennet and science writer Donald G. McNeil, Jr.—were forced out, while radical progressive voices were elevated.

This was the national climate when Laura Helmuth took the helm of Scientific American in April 2020. Helmuth boasted a sterling résumé: a Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience from the University of California–Berkeley and a string of impressive editorial jobs at outlets including Science, National Geographic, and the Washington Post. Taking over a large print and online media operation during the early weeks of the Covid pandemic couldn’t have been easy. On the other hand, those difficult times represented a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for an ambitious science editor. Rarely in the magazine’s history had so many Americans urgently needed timely, sensible science reporting: Where did Covid come from? How is it transmitted? Was shutting down schools and businesses scientifically justified? What do we know about vaccines?

Scientific American did examine Covid from various angles, including an informative July 2020 cover story diagramming how the SARS-CoV-2 virus “sneaks inside human cells.” But the publication didn’t break much new ground in covering the pandemic. When it came to assessing growing evidence that Covid might have escaped from a laboratory, for example, SciAm got scooped by New York and Vanity Fair, publications known more for their coverage of politics and entertainment than of science.

At the same time, SciAm dramatically ramped up its social-justice coverage. The magazine would soon publish a flurry of articles with titles such as “Modern Mathematics Confronts Its White, Patriarchal Past” and “The Racist Roots of Fighting Obesity.” The death of the twentieth century’s most acclaimed biologist was the hook for “The Complicated Legacy of E. O. Wilson,” an opinion piece arguing that Wilson’s work was “based on racist ideas,” without quoting a single line from his large published canon. At least those pieces had some connection to scientific topics, though. In 2021, SciAm published an opinion essay, “Why the Term ‘JEDI’ Is Problematic for Describing Programs That Promote Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion.” The article’s five authors took issue with the effort by some social-justice advocates to create a cute new label while expanding the DEI acronym to include “Justice.” The Jedi knights of the Star Wars movies are “inappropriate mascots for social justice,” the authors argued, because they are “prone to (white) saviorism and toxically masculine approaches to conflict resolution (violent duels with phallic light sabers, gaslighting by means of ‘Jedi mind tricks,’ etc.).” What all this had to do with science was anyone’s guess.

Several prominent scientists took note of SciAm’s shift. “Scientific American is changing from a popular-science magazine into a social-justice-in-science magazine,” Jerry Coyne, a University of Chicago emeritus professor of ecology and evolution, wrote on his popular blog, “Why Evolution Is True.” He asked why the magazine had “changed its mission from publishing decent science pieces to flawed bits of ideology.”

“The old Scientific American that I subscribed to in college was all about the science,” University of New Mexico evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller told me. “It was factual reporting on new ideas and findings from physics to psychology, with a clear writing style, excellent illustrations, and no obvious political agenda.” Miller says that he noticed a gradual change about 15 years ago, and then a “woke political bias that got more flagrant and irrational” over recent years. The leading U.S. science journals, Nature and Science, and the U.K.-based New Scientist made a similar pivot, he says. By the time Trump was elected in 2016, he says, “the Scientific American editors seem to have decided that fighting conservatives was more important than reporting on science.”

Scientific American’s increasing engagement in politics drew national attention in late 2020, when the magazine, for the first time in its 175-year history, endorsed a presidential candidate. “The evidence and the science show that Donald Trump has badly damaged the U.S. and its people,” the editors wrote. “That is why we urge you to vote for Joe Biden.” In an e-mail exchange, Scientific American editor-in-chief Helmuth said that the decision to endorse Biden was made unanimously by the magazine’s staff. “Overall, the response was very positive,” she said. Helmuth also pushed back on the idea that getting involved in political battles represented a new direction for SciAm. “We have a long and proud history of covering the social and political angles of science,” she said, noting that the magazine “has advocated for teaching evolution and not creationism since we covered the Scopes Monkey Trial.”

Scientific American wasn’t alone in endorsing a presidential candidate in 2020. Nature also endorsed Biden in that election cycle. The New England Journal of Medicine indirectly did the same, writing that “our current leaders have demonstrated that they are dangerously incompetent” and should not “keep their jobs.” Vinay Prasad, the prominent oncologist and public-health expert, recently lampooned the endorsement trend on his Substack, asking whether science journals will tell him who to vote for again in 2024. “Here is an idea! Call it crazy,” he wrote: “Why don’t scientists focus on science, and let politics decide the election?” When scientists insert themselves into politics, he added, “the only result is we are forfeiting our credibility.”

But what does it mean to “focus on science”? Many of us learned the standard model of the scientific method in high school. We understand that science attempts—not always perfectly—to shield the search for truth from political interference, religious dogmas, or personal emotions and biases. But that model of science has been under attack for half a century. The French theorist Michel Foucault argued that scientific objectivity is an illusion produced and shaped by society’s “systems of power.” Today’s woke activists challenge the legitimacy of science on various grounds: the predominance of white males in its history, the racist attitudes held by some of its pioneers, its inferiority to indigenous “ways of knowing,” and so on. Ironically, as Christopher Rufo points out in his book America’s Cultural Revolution, this postmodern ideology—which began as a critique of oppressive power structures—today empowers the most illiberal, repressive voices within academic and other institutions.

Shermer believes that the new style of science journalism “is being defined by this postmodern worldview, the idea that all facts are relative or culturally determined.” Of course, if scientific facts are just products of a particular cultural milieu, he says, “then everything is a narrative that has to reflect some political side.” Without an agreed-upon framework to separate valid from invalid claims—without science, in other words—people fall back on their hunches and in-group biases, the “my-side bias.”

Traditionally, science reporting was mostly descriptive—writers strove to explain new discoveries in a particular field. The new style of science journalism takes the form of advocacy—writers seek to nudge readers toward a politically approved opinion.

“Lately journalists have been behaving more like lawyers,” Shermer says, “marshaling evidence in favor of their own view and ignoring anything that doesn’t help their argument.” This isn’t just the case in science journalism, of course. Even before the Trump era, the mainstream press boosted stories that support left-leaning viewpoints and carefully avoided topics that might offer ammunition to the Right. Most readers understand, of course, that stories about politics are likely to be shaped by a media outlet’s ideological slant. But science is theoretically supposed to be insulated from political influence. Sadly, the new woke style of science journalism reframes factual scientific debates as ideological battles, with one side presumed to be morally superior. Not surprisingly, the crisis in science journalism is most obvious in the fields where public opinion is most polarized.

The Covid pandemic was a crisis not just for public health but for the public’s trust in our leading institutions. From Anthony Fauci on down, key public-health officials issued unsupported policy prescriptions, fudged facts, and suppressed awkward questions about the origin of the virus. A skeptical, vigorous science press could have done a lot to keep these officials honest—and the public informed. Instead, even elite science publications mostly ran cover for the establishment consensus. For example, when Stanford’s Jay Bhattacharya and two other public-health experts proposed an alternative to lockdowns in their Great Barrington Declaration, media outlets joined in Fauci’s effort to discredit and silence them.

Richard Ebright, professor of chemical biology at Rutgers University, is a longtime critic of gain-of-function research, which can make naturally occurring viruses deadlier. From the early weeks of the pandemic, he suspected that the virus had leaked from China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology. Evidence increasingly suggests that he was correct. I asked Ebright how he thought that the media had handled the lab-leak debate. He responded:

Science writers at most major news outlets and science news outlets have spent the last four years obfuscating and misrepresenting facts about the origin of the pandemic. They have done this to protect the scientists, science administrators, and the field of science—gain-of-function research on potential pandemic pathogens—that likely caused the pandemic. They have done this in part because those scientists and science administrators are their sources, . . . in part because they believe that public trust in science would be damaged by reporting the facts, and in part because the origin of the pandemic acquired a partisan political valance after early public statements by Tom Cotton, Mike Pompeo, and Donald Trump.

During the first two years of the pandemic, most mainstream media outlets barely mentioned the lab-leak debate. And when they did, they generally savaged both the idea and anyone who took it seriously. In March 2021, long after credible evidence emerged hinting at a laboratory origin for the virus, Scientific American published an article, “Lab-Leak Hypothesis Made It Harder for Scientists to Seek the Truth.” The piece compared the theory to the KGB’s disinformation campaign about the origin of HIV/AIDS and blamed lab-leak advocates for creating a poisonous climate around the issue: “The proliferation of xenophobic rhetoric has been linked to a striking increase in anti-Asian hate crimes. It has also led to a vilification of the [Wuhan Institute of Virology] and some of its Western collaborators, as well as partisan attempts to defund certain types of research (such as ‘gain of function’ research).” Today we know that the poisonous atmosphere around the lab-leak question was deliberately created by Anthony Fauci and a handful of scientists involved in dangerous research at the Wuhan lab. And the case for banning gain-of-function research has never been stronger.

One of the few science journalists who did take the lab-leak question seriously was Donald McNeil, Jr., the veteran New York Times reporter forced out of the paper in an absurd DEI panic. After leaving the Times—and like several other writers pursuing the lab-leak question—McNeil published his reporting on his own Medium blog. It is telling that, at a time when leading science publications were averse to exploring the greatest scientific mystery of our time, some of the most honest reporting on the topic was published in independent, reader-funded outlets. It’s also instructive to note that the journalist who replaced McNeil on the Covid beat at the Times, Apoorva Mandavilli, showed open hostility to investigating Covid’s origins. In 2021, she famously tweeted: “Someday we will stop talking about the lab leak theory and maybe even admit its racist roots. But alas, that day is not yet here.” It would be hard to compose a better epitaph to the credibility of mainstream science journalism.

As Shermer observed, many science journalists see their role not as neutral reporters but as advocates for noble causes. This is especially true in reporting about the climate. Many publications now have reporters on a permanent “climate beat,” and several nonprofit organizations offer grants to help fund climate coverage. Climate science is an important field, worthy of thoughtful, balanced coverage. Unfortunately, too many climate reporters seem especially prone to common fallacies, including base-rate neglect, and to hyping tenuous data.

The mainstream science press never misses an opportunity to ratchet up climate angst. No hurricane passes without articles warning of “climate disasters.” And every major wildfire seemingly generates a “climate apocalypse” headline. For example, when a cluster of Quebec wildfires smothered the eastern U.S. in smoke last summer, the New York Times called it “a season of climate extremes.” It’s likely that a warming planet will result in more wildfires and stronger hurricanes. But eager to convince the public that climate-linked disasters are rapidly trending upward, journalists tend to neglect the base rate. In the case of Quebec wildfires, for example, 2023 was a fluky outlier. During the previous eight years, Quebec wildfires burned fewer acres than average; then, there was no upward trend—and no articles discussing the paucity of fires. By the same token, according to the U.S. National Hurricane Center, a lower-than-average number of major hurricanes struck the U.S. between 2011 and 2020. But there were no headlines suggesting, say, “Calm Hurricane Seasons Cast Doubt on Climate Predictions.”

Most climate journalists wouldn’t dream of drawing attention to data that challenge the climate consensus. They see their role as alerting the public to an urgent problem that will be solved only through political change.

Similar logic applies to social issues. The social-justice paradigm rests on the notion that racism, sexism, transphobia, and other biases are so deeply embedded in our society that they can be eradicated only through constant focus on the problem. Any people or institutions that don’t participate in this process need to be singled out for criticism. In such an atmosphere, it takes a particularly brave journalist to note exceptions to the reigning orthodoxy.

This dynamic is especially intense in the debates over transgender medicine. The last decade has seen a huge surge in children claiming dissatisfaction with their gender. According to one survey, the number of children aged six to 17 diagnosed with gender dysphoria surged from roughly 15,000 to 42,000 in the years between 2017 and 2021 alone. The number of kids prescribed hormones to block puberty more than doubled. Puberty blockers and other treatments for gender dysphoria have enormous potential lifelong consequences, including sterility, sexual dysfunction, and interference with brain development. Families facing treatment decisions for youth gender dysphoria desperately need clear, objective guidance. They’re not getting it.

Instead, medical organizations and media outlets typically describe experimental hormone treatments and surgeries as routine, and even “lifesaving,” when, in fact, their benefits remain contested, while their risks are enormous. In a series of articles, the Manhattan Institute’s Leor Sapir has documented how trans advocates enforce this appearance of consensus among U.S. scientists, medical experts, and many journalists. Through social-media campaigns and other tools, these activists have forced conferences to drop leading scientists, gotten journals to withdraw scientific papers after publication, and interfered with the distribution of Abigail Shrier’s 2020 book Irreversible Damage, which challenges the wisdom of “gender-affirming care” for adolescent girls. While skeptics are cowed into silence, Sapir concludes, those who advocate fast-tracking children for radical gender therapy “will go down in history as responsible for one of the worst medical scandals in U.S. history.”

In such an overheated environment, it would be helpful to have a journalistic outlet advocating a sober, evidence-based approach. In an earlier era, Scientific American might have been that voice. Unfortunately, SciAm today downplays messy debates about gender therapies, while offering sunny platitudes about the “safety and efficacy” of hormone treatments for prepubescent patients. For example, in a 2023 article, “What Are Puberty Blockers, and How Do They Work?,” the magazine repeats the unsubstantiated claim that such treatments are crucial to preventing suicide among gender-dysphoric children. “These medications are well studied and have been used safely since the late 1980s to pause puberty in adolescents with gender dysphoria,” SciAm states.

The independent journalist Jesse Singal, a longtime critic of slipshod science reporting, demolishes these misleading claims in a Substack post. In fact, the use of puberty blockers to treat gender dysphoria is a new and barely researched phenomenon, he notes: “[W]e have close to zero studies that have tracked gender dysphoric kids who went on blockers over significant lengths of time to see how they have fared.” Singal finds it especially alarming to see a leading science magazine obscure the uncertainty surrounding these treatments. “I believe that this will go down as a major journalistic blunder that will be looked back upon with embarrassment and regret,” he writes.

Fortunately, glimmers of light are shining through on the gender-care controversy. The New York Times has lately begun publishing more balanced articles on the matter, much to the anger of activists. And various European countries have started reassessing and limiting youth hormone treatments. England’s National Health Service recently commissioned the respected pediatrician Hilary Cass to conduct a sweeping review of the evidence supporting youth gender medicine. Her nearly 400-page report is a bombshell, finding that evidence supporting hormone interventions for children is “weak,” while the long-term risks of such treatments have been inadequately studied. “For most young people,” the report concludes, “a medical pathway will not be the best way to manage their gender-related distress.” In April, the NHS announced that it will no longer routinely prescribe puberty blocking drugs to children.

Scientific American has yet to offer an even-handed review of the new scientific skepticism toward aggressive gender medicine. Instead, in February, the magazine published an opinion column, “Pseudoscience Has Long Been Used to Oppress Transgender People.” Shockingly, it argues for even less medical caution in dispensing radical treatments. The authors approvingly note that “many trans activists today call for diminishing the role of medical authority altogether in gatekeeping access to trans health care,” arguing that patients should have “access to hormones and surgery on demand.” And, in an implicit warning to anyone who might question these claims and goals, the article compares today’s skeptics of aggressive gender medicine to Nazi eugenicists and book burners. Shortly after the Cass report’s release, SciAm published an interview with two activists who argue that scientists questioning trans orthodoxy are conducting “epistemological violence.”

There’s nothing wrong with vigorous debate over scientific questions. In fact, in both science and journalism, adversarial argumentation is a vital tool in testing claims and getting to the truth. “A bad idea can hover in the ether of a culture if there is no norm for speaking out,” Shermer says. Where some trans activists cross the line is in trying to derail debate by shaming and excluding anyone who challenges the activists’ manufactured consensus.

Such intimidation has helped enforce other scientific taboos. Anthony Fauci called the scientists behind the Great Barrington Declaration “fringe epidemiologists” and successfully lobbied to censor their arguments on social media. Climate scientists who diverge from the mainstream consensus struggle to get their research funded or published. The claim that implicit racial bias unconsciously influences our minds has been debunked time and again—but leading science magazines keep asserting it.

Scientists and journalists aren’t known for being shrinking violets. What makes them tolerate this enforced conformity? The intimidation described above is one factor. Academia and journalism are both notoriously insecure fields; a single accusation of racism or anti-trans bias can be a career ender. In many organizations, this gives the youngest, most radical members of the community disproportionate power to set ideological agendas.

“Scientists, science publishers, and science journalists simply haven’t learned how to say no to emotionally unhinged activists,” evolutionary psychologist Miller says. “They’re prone to emotional blackmail, and they tend to be very naive about the political goals of activists who claim that scientific finding X or Y will ‘impose harm’ on some group.”

But scientists may also have what they perceive to be positive motives to self-censor. A fascinating recent paper concludes: “Prosocial motives underlie scientific censorship by scientists.” The authors include a who’s who of heterodox thinkers, including Miller, Manhattan Institute fellow Glenn Loury, Pamela Paresky, John McWhorter, Steven Pinker, and Wilfred Reilly. “Our analysis suggests that scientific censorship is often driven by scientists, who are primarily motivated by self-protection, benevolence toward peer scholars, and prosocial concerns for the well-being of human social groups,” they write.

Whether motivated by good intentions, conformity, or fear of ostracization, scientific censorship undermines both the scientific process and public trust. The authors of the “prosocial motives” paper point to “at least one obvious cost of scientific censorship: the suppression of accurate information.” When scientists claim to represent a consensus about ideas that remain in dispute—or avoid certain topics entirely—those decisions filter down through the journalistic food chain. Findings that support the social-justice worldview get amplified in the media, while disapproved topics are excoriated as disinformation. Not only do scientists lose the opportunity to form a clearer picture of the world; the public does, too. At the same time, the public notices when claims made by health officials and other experts prove to be based more on politics than on science. A new Pew Research poll finds that the percentage of Americans who say that they have a “great deal” of trust in scientists has fallen from 39 percent in 2020 to 23 percent today.

“Whenever research can help inform policy decisions, it’s important for scientists and science publications to share what we know and how we know it,” Scientific American editor Helmuth says. “This is especially true as misinformation and disinformation are spreading so widely.” That would be an excellent mission statement for a serious science publication. We live in an era when scientific claims underpin huge swaths of public policy, from Covid to climate to health care for vulnerable youths. It has never been more vital to subject those claims to rigorous debate.

Unfortunately, progressive activists today begin with their preferred policy outcomes or ideological conclusions and then try to force scientists and journalists to fall in line. Their worldview insists that, rather than challenging the progressive orthodoxy, science must serve as its handmaiden. This pre-Enlightenment style of thinking used to hold sway only in radical political subcultures and arcane corners of academia. Today it is reflected even in our leading institutions and science publications. Without a return to the core principles of science—and the broader tradition of fact-based discourse and debate—our society risks drifting onto the rocks of irrationality.

[ Via: https://archive.today/j03w3 ]

==

Scientific American now embodies the worst of far-left anti-science nonsense.

#SciAm#Scientific American#James B. Meigs#academic corruption#ideological corruption#ideological capture#wokeness#cult of woke#wokeism#wokeness as religion#woke#unscientific#anti science#antiscience#religion is a mental illness

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you give me examples of praxis, mutual aid and dual power I can do? If it helps anything, I live in Southern Sweden, but I just in general have no idea where to start.

Good question!

Just to emphasise, praxis is an action that intends to facilitate the fruition of one’s political ideals, so mutual aid, the facilitation of direct democracy and the creation of dual power are all modes of praxis. It sounds like you knew this already though.

There are loads of ways to get involved! In this post I’m going to talk about three things, namely;

1: theory

2: networking (how to meet up with other anarchists!)

3: mutual aid (the most important one)

1: Theory - Reading theory is a great way to understand what you’re doing and why you’re doing it

As I’m sure people will tell you, theory is not the be all and end all of being an anarchist. You can easily get away with being an anarchist without reading a drop of theory.

But it helps. When you’re exploring anarchism and your relationship with it, you’re probably going to have a lot of questions, and people have devoted novels and novels all to just answering those questions! Here’s a big directory of resources just for you!

If you’re looking for a good introductory book, I cannot recommend enough the ABCs of Anarchism by Alexander Berkman. It’s what got me into it. I would recommend reading some introductory stuff before you explore other important anarchists (Kropotkin, Bakunin, Goldman), since the older foundational stuff can be antiquated or difficult to read in places. Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid is a great praxis guide, though.

2: Networking - Go to local meets for anarchists in your area

Forgive me if I have this wrong, but Southern Sweden is fairly urban, right? If you live in a town or city, there’s a really good chance there’s anarchist organisations or at least mutual aid groups in your area that will hold meetings to discuss topics concerning anarchism and even leftism in general. They’ll also probably do a book club; anarchists famously love books.

(Hilariously, one factor that makes it so hard for the police to infiltrate anarchist groups is that the debate is so intense and various that they stick out like a sore thumb.)

These are the groups that Wikipedia has to offer.

I really have no idea what these guys are like; I’m from a tiny little village in the UK. It’s worth looking about. Anarchists tend to put up flyers for the organisations in their local area (provided they’re not super spicy lmao).

If you go to the meetups and the organisation seems like it’s got its shit together, join up! It’s a lot easier to help your community as a mutually interested collective than it is as an individual (obviously).

3: Mutual Aid - DO! MUTUAL! AID!

Many anarchists will tell you that the single most important way to get involved as an anarchist is to do mutual aid. I concur, honestly. Mutual Aid is the foundation of anarchist society. It is the sharing of resources and the collective commitment to respecting and supporting everybody you possibly can that forms the backbone of anarchist society.

Mutual aid is a form of direct action, i.e. tackling an issue by directly focusing on the material conditions that generated the issue. It relies on individuals coming together with their wider community to co-operate in order to mutually achieve a set aim.

I say this a lot! And I’ll say it again!

Mutual aid is for everyone, no matter your situation. Everybody needs help sometimes. The point is that we build networks of trust and reliability that will eventually come to fruition in full-fledged anarchist society. Given the scale of anarchist projects in western society at this point, though, many anarchists focus on specific and pressing issues in their area.

It’s important to remember that the nature of capitalism is such that almost everybody is two or three really bad months away from poverty. Capitalism hurts everyone and mutual aid is an effort to alleviate that suffering. Mutual aid is for everyone.

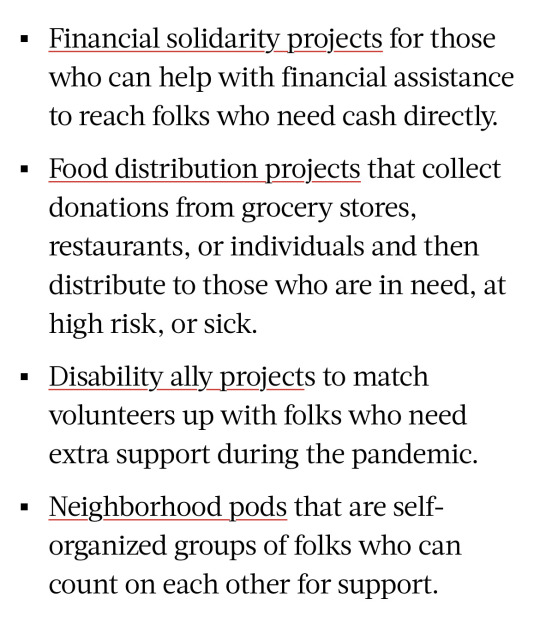

Here’s some examples of common mutual aid projects, taken from this article

mutual aid is various and complex, much like anarchist society.

One mutual aid group I heard about the other day is a group that helps alleviate loneliness in the elderly by visiting their homes and helping them with their groceries, etc.

mutual aid also played an important part in the Greensboro sit-ins movement and the wider struggle for civil rights in black communities in America throughout the 1950s-70s, and remains in that key role today.

It works so well for marginalised groups because it allows disempowered individuals to pool their resources in order to make a greater impact on the issue. It logically follows that it would be a huge axis of anarchist organisation.

94 notes

·

View notes

Note

Tell us.

*cracks knuckles*

Reasons Pantalone is husband material: a thread

So in the context of prev ask, literally anyone would make for a better spouse in an arranged marriage, it’s just that I think Pantalone would be the best because I love him

Because I love him also I’m going off my interpretations of him because where are my fucking crumbs Hoyo it has been a year since his appearance-

First and foremost, he’s a rich bitch. He cannot only provide for you, but he could also spoil you absolutely rotten.

Second, we know he’s very passionate about his work and ideas, going on and on about them. A passion for your craft is a very attractive trait but then you factor in that voice and yeah, even if you don’t know wtf he’s talking about you’re absolutely getting drawn into that discussion just to hear him talk.

He has many stories to share, some he’s more willing to discuss than others, but regardless the stories he has are rarely ever dull. The only dull ones would be business meetings but the voice does the heavy lifting.

From intellectual discussions to hearing him ramble about his day at the bank, no matter how active you are in that conversation, it’s rarely ever a dull one.

He’s the friendliest of the Harbingers save for Childe. His status and his jobs as Harbinger and founder of the Northland Bank means he’s had to learn and master etiquette and manners and how to sweet talk people. Even if it is just a front to get others to trust him, a polite tone and charming smile will get you anywhere if you know when and where to use them.

Getting him to actually open up to you would be a tricky job because childhood trauma is a bitch, but once you actually get him vulnerable you will have that man in the palm of your hand.

His empathy can be a little hit or miss sometimes because again, trauma is a bitch. It’s a side effect of the cynicism he’s developed as a result of growing up in poverty and having to get his hands dirty in one way or another to survive, let alone succeed in life. Still, when it comes to his partner, he takes their troubles and traumas very seriously because he knows what it’s like to be helpless and doesn’t want them of all people to feel that way.

You cannot tell me he isn’t touch starved. In private that man can and will find any way he can to get close to you. He will obvs respect boundaries, but he just finds comfort in your touch. This one is more up to you if it’s a good or bad thing but I like physical touch so it’s good to me.

The man is meticulous. He would want everything to be perfect. He’ll pull whatever strings he can to impress you, and would pay attention to all the things you like. Is there a particular gemstone you like? He’ll make sure all the jewellery he puts on you has them and that they match your attire. You mentioned offhand that there’s a specific dish from Sumeru you haven’t had in a while? Dinner the next day is that exact dish with the most authentic recipe he can have his cooks work from.

Could literally give you any wedding you want, at least as far as cost goes. If it’s some super ridiculous and tacky themed wedding he will more than likely shoot it down, but if we’re talking venues, decor, attire, food, etc, literally do not worry about it. Just tell him what you want and he’ll have it done and paid for yesterday. Small wedding, big wedding, does not matter, he can afford it.

What I’m trying to say is that even if you were to be in an arranged and probably loveless marriage with him, you’d still get a pretty good deal because you still get an interesting and polite man who will take care of your needs. It just happens that if you do marry him for love or eventually fall in love, he will just go all in on you because now he wants to keep you, impress you, and show his appreciation to you.

Anyways seriously hoyo where the fuck is he-

This would’ve been longer but I already shared a lot of my ideas in my domestic pants headcanons, and uh... the rest of my ideas are not pg-13 and I’m not in the smut writing mood (plus I think I’d rather have that in a separate post but I’m not doing it rn)

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abdallah Fayyad at Vox:

In an ideal world, everyone who qualifies for an aid program ought to receive its benefits. But the reality is that this is often not the case. Before the pandemic, for example, nearly one-fifth of Americans who qualified for food stamps didn’t receive them. In fact, millions of Americans who are eligible for existing social welfare programs don’t receive all of the benefits they are entitled to.

[...] Means testing a given social program can have good intentions: Target spending toward the people who need it most. After all, if middle- or high-income people who can afford their groceries or rent get federal assistance in paying for those things, then wouldn’t there be less money to go around for the people who actually need it? The answer isn’t so straightforward.

How means testing can sabotage policy goals

Implementing strict eligibility requirements can be extremely tedious and have unintended consequences. For starters, let’s look at one of the main reasons lawmakers advocate for means testing: saving taxpayers’ money. But that’s not always what happens. “Though they’re usually framed as ways of curbing government spending, means-tested benefits are often more expensive to provide, on average, than universal benefits, simply because of the administrative support needed to vet and process applicants,” my colleague Li Zhou wrote in 2021. More than that, means testing reduces how effective antipoverty programs can be because a lot of people miss out on benefits. As Zhou points out, figuring out who qualifies for welfare takes a lot of work, both from the government and potential recipients who have to fill out onerous applications. The paperwork can be daunting and can discourage people from applying. It can also result in errors or delays that would easily be avoided if a program is universal.

There’s also the fact that creating an income threshold creates incentives for people to avoid advancing in their careers or take a higher-paying job. One woman I interviewed a few years ago, for example, told me that after she started a job as a medical assistant and lost access to benefits like food stamps, it became harder to make ends meet for her and her daughter. When lawmakers aggressively means test programs, people like her are often left behind, making it harder to transition out of poverty.

As a result, means testing can seriously limit a welfare program’s potential. According to a report by the Urban Institute, for example, the United States can reduce poverty by more than 30 percent just by ensuring that everyone who is eligible for an existing program receives its benefits. One way to do that is for lawmakers to make more welfare programs universal instead of means-tested.

Why universal programs are a better choice

There sometimes is an aversion to universal programs because they’re viewed as unnecessarily expensive. But universal programs are often the better choice because of one very simple fact: They are generally much easier and less expensive to administer. Two examples of this are some of the most popular social programs in the country: Social Security and Medicare. Universal programs might also create less division among taxpayers as to how their money ought to be spent. A lot of opposition to welfare programs comes from the fact that some people simply don’t want to pay for programs they don’t directly benefit from, so eliminating that as a factor can create more support for a given program. In 2023, following a handful of other states, Minnesota implemented a universal school meal program where all students get free meals. This was in response to the problems that arise when means testing goes too far. Across the country, students in public school pay for their meals depending on their family’s income. But this system has stigmatized students who get a free meal. According to one study, 42 percent of eligible families reported that their kids are less likely to eat their school meal because of the stigma around it.

Vox explores the idea of how more people could benefit from changes to welfare qualifications by making such programs universal instead of means-tested.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

im a mutual sending this bc i saw you getting hate on that post again but im shy - honestly as a person who used to self-harm when i was younger and still does on infrequent occasions your post was deeply validating.

when i was in intensive care a lot of the time self-harming behavior was automatically conflated with suicidality, when that was never the case for me: i never cut deep enough or in locations where i could have hurt myself in a life-threatening way. cutting was a release valve for extreme stress or feelings of guilt and shame too big to deal with in a "healthy" way at the time because of the circumstances i was in.

ive had to lie to numerous professionals about my self-harming (either the details or that i do it at all) because they assume that i am in need of intensive care and sometimes attempt to institutionalize me instead of listening to me when i say that it's not a risk to my physical health and that there are other far more important factors putting my mental health at risk than the action of self-harm ("poverty" and "being abused", for starters).

also note on my second lil paragraph: although it wasn't the case for me, i feel it necessary to note that i believe people who self-harm due to suicidal ideation or are self-harming in a life-threatening way are also entitled to that agency over their behavior. something that was actually very important for me in dealing with my own suicidality was acknowledging the reality of it. rather than shying away from the question and the idea with "suicide isn't an option" type language, what helped me was framing it as just another choice that i was free to make or not make. it became less taboo and less scary, and therefore easier to deal with because there wasn't as much shame and fear in the mix. what made me stop wanting to kill myself as much as i had before was acknowledging that suicide WAS an option, it just wasn't my BEST option. a similar thing has begun to happen to me with self-harm, now that I've moved out of the abusive situation i grew up in - self-harm is still an option i have in my back pocket for emergencies to deal with feelings, and im allowed to do it, it's just not my best option now that i have more space and time to be myself.

^ 💕

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

Unfortunately I don’t think higher education helps when it comes to conspiracy theory. I know someone who has two diplomas: history of art and English. And doing its graduate studies. Has classes about intellectual history, history, philosophy etc etc. Full on believes Taylor Swift is secretly lesbian and has fake relationships and was in a relationship with Karlie Kloss. So yeah, at least on this case it didn’t help. When you’re convinced it’s hard to prove it other wise. Because everything proves you right, even if it doesn’t in reality. I think it’s called cognitive dissonance. But yeah, that what’s so scary

Ok so I'm assuming this is in reference to the post about the Hampstead Paedophile Hoax and the fact I said that "poor education is likely to leave people vulnerable to believing (conspiracy theories)." As you'll note there, I didn't mention higher education specifically. But also, what I said is accurate. Study after study has demonstrated a correlation between poor education and belief in conspiracy theories. I didn't say - nor do the studies state - that if you have a university degree you will never ever believe in conspiracies or that if you left school at 16 you'll always believe conspiracy theories. It's just correlation. It just means there's some kind of relationship between the two factors. This is why I said that it leaves people vulnerable to believing conspiracies, not that it alone causes conspiracy theory mindsets. Because there are other factors which can also influence your likelihood of believing conspiracies, like feelings of powerlessness. Anecdotal evidence doesn't change that. If I had said "no one with a degree has ever believed a conspiracy" then your friend's existence would be relevant. But I didn't. And you can't say that the correlation, the connection, doesn't exist at all because you have one friend who doesn't fit.

To use a different example, we know that there is a correlation between your economic status in childhood and your likelihood of having a mental illness as an adult i.e. if you grew up in poverty you're more likely to have a mental illness as an adult. That does not mean that every person who grew up in poverty has a mental illness or that every person who grew up wealthy doesn't have a mental illness, and it doesn't mean every person who has a mental illness grew up in poverty. We know that people are complicated and there are lots of other factors involved. But it's still true that there is a connection.

As for the last bit, sounds like confirmation bias. You see it a lot in people who believe in horoscopes, psychics etc as well. They take a standpoint and everything is either twisted to support what they already believe or they filter out and forget the things that don't support their belief and focus on things that do support it. Cognitive dissonance is the feeling you have when you hold two contradictory beliefs at the same time or when you do something even though it is contrary to a belief you hold. It's basically like your brain's error message. The idea goes that your brain likes things to be consistent and so when you have two opposing ideas or beliefs - and you know they're opposing - your brain doesn't like it and that feeling and the attempts to correct the imbalance is cognitive dissonance. Like I'm a smoker. I know it's gross, it's expensive, it's unhealthy. I still do it. And sometimes I'll sit and think "this is terrible and I should stop" but then I also think "but I like it and I need it and I want to continue." Which causes me distress. That's cognitive dissonance.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unit 10

As I develop as a nature interpreter, my ethics are based on the values my family taught me throughout my upbringing, what is morally right and wrong, lessons I've learned from life experiences, and courses I've taken involving religion, cultures, and the environment (such as this one).

Two things my parents have always been persistent in teaching me (regarding nature) were to always live in the present and enjoy your journey towards the future every day because you'll never get that time back, and never litter and never allow others around you to feel comfortable in doing so. My parents were the first of their family to immigrate out of Venezuela and into Canada because they were aware of the declining state of their government and wanted to ensure a safe future filled with infinite possibilities for their children and themselves. They often tell me stories from their childhood, and what it was like to live constantly surrounded by nature and see firsthand natural phenomena that aren't possible to see often in Ontario. Hearing about their experiences and the poverty surrounding Venezuela at the time helped me realize at a very young age, that life is what you make of it, and the actions following your interpretations of your life will determine your experience. Although my parents didn't have the accessibility as children to buy new toys every so often or didn't have the trendiest brands of fashion, they never once made those factors influence their view of their quality of life. Anytime they got the opportunity to travel with their families to the States on vacation or got any luxury out of the ordinary, they never once compared it to anything else and were always simply grateful and present for the moment.

One of my personal favourite photos of my family and me while visiting some cousins who had just moved to Montreal.

Being a highly observant person, I've always noticed people's attitudes in different and similar situations; comparing these unconnected people and their interpretation and perspective of where they are in life, I saw that the biggest factors to their happiness and emotional well-being were having a positive attitude and determination. As I've been growing, these two attributes have been my main lead through life and it has allowed me to grow better time-management skills to have a better work-life balance which I struggled with, during the early transition from high school to university life. The key to beginning habit stacking (a term I learned about on a TikTok video about uni life tips) was developing an early morning routine and staying relatively consistent. I found this trick perfect for me as I already had routines in place every morning and night, such as my face routine, that I could stack other habits on top of it. If you've read any of my past blogs, you'll know by now I like to interpret many things in my life through a more spiritual perspective; I've always felt that you can set the tone for the day with the energy you approach it, but being that I can sometimes wake up moody if I didn't get enough sleep, I found it hard to wake up between 7-8 am and get a productive start out of my day. After speaking with my mom about it, she reminded me about changing my "I have to" perspective into a "I get to" view. So, rather than waking up in the morning and immediately reminding myself about all the responsibilities I'd need to get done that day, I took those early moments of waking up to express and feel gratitude for a couple of minutes as I pushed myself out of bed. To be completely transparent, my first couple of attempts didn't work out as planned, but once I was determined to spend time with nature for at least a total of 45 minutes a day and incorporate my walking meditations during it, it became a set routine; I had completely underestimated the long term benefits and how much more productive, relaxed, and focused I would be throughout the day. Having this set routine of waking up and immediately going for a brisk walk while listening to a gratitude meditation, then after the simple sounds of nature and its early morning quietness, allows me to stop and take a pause in my day to myself to be consciously present, grateful and aware to not take things for granted and every day is a gift. Additionally, as mentioned, this morning routine completely changed my energy throughout my days, making me feel more spiritually grounded and connected to nature and its inhabitants; I also found myself much less stressed, more patient, and looking forward to my mornings.

Photo of my parents while the 3 of us were on our daily summer morning bike rides.

As for the second key lesson about having a strong stance on keeping our earth clean and not littering it, I feel the message ran deeper than expected for me personally. Since I had always felt a connection to nature and animals, those were the types of shows I enjoyed watching on a children's channel called TVOKids such as Zoboomafoo and Wild Kratts which added to the passion for recognizing our responsibility in caring for the environment even if it seems many don't. For my parents, the littering issue in the cities was a complete culture shock to them and they had never seen something so irresponsible be so normalized. But even after moving from Toronto to Mississauga to Oakville to then Stoney Creek throughout the years of our upbringing, they noticed that this wasn't just a "teen" problem, it was a problem with many people losing sight of how bad it is for the environment and selfishly not caring about everyone's due diligence in keeping our areas and the animals clean and safe. I would often walk my dog through many grassy areas and parks that had soccer fields, water park areas, swings, etc. but every time I would I'd feel stressed and worried, making sure he wouldn't step on broken glass, pick up and eat garbage thrown, or even get too close to general litter. I'd often mention it to my dad and the next day my entire family would go out to pick up and clean up the trash around the neighbourhood for around 3 hours. Of course, being sometimes a moody teenager at the time, I didn't appreciate the lesson my parents were trying to teach us, I found it unfair that others could mindlessly throw their trash just for us to voluntarily pick it up for them. But as I've grown, I've realized the message of putting action and change into something that is making you unhappy, standing up completely for what you want and believe in, as well as hopefully inspiring others to do the same, being the trailblazers.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't really understand where everybody's finances are, I guess technically, because sometimes it feels really weird to like... join a server to try and meet people and make friends or something and like.. abruptly have to deal with like. Wild accusations about like. The fact that I'm also in a patreon only server that their in, and like. Wow I much spend so much money. Hhmmmmm. Soooo interesting. How can you do that???

And like. I factor my patreons into my bills and budget around it. Like. I gotta be careful, and I can't just spend willy nilly, but like. It's like. A set of expenditures that I like. Plan around, and ultimately, I can make it manageable for the time being. Sometimes, I drop things when financial situations change.

People have gotten so extremely judgemental about other people's spending habits with absolutely no evidence whatsoever. Like. No one is eating the rich, y'all will be eating people who use Door Dash or like... have a hobby.

I live on disability. I'm below the poverty line, man. Other sacrifices get made. But literally, there is no way to know all this from the context of like... "subscribes to a handful of patreons"

Aaaaaa

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

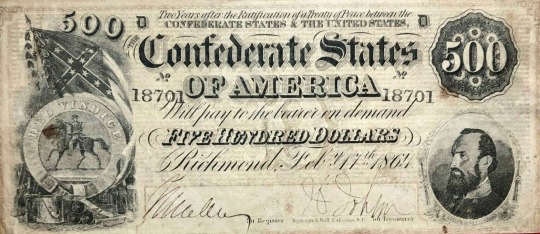

“We send our cotton to Manchester and Lowell, our sugar to New York refineries, our hides to down-east tanneries and our children to Yankee colleges, and are ever ready to find fault with the North because it lives by our folly. We want home manufactures and these we must have, if we are ever to be independent.

—Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph, 1859

This analysis of the Southern economy on the eve of war was classic. In 1861 the Confederate States had a population of just over 9 million, of whom about 3.5 million were slaves. The population of the United States was approximately 22 million. The South had less than half the railroad mileage of the North, and much of this track (of eleven different gauges) connected points of little military or industrial significance. More than four-fifths of the old Union's manufacturing had been carried on in the North. Southern manufactures in 1860 were worth $69 million, as opposed to $388.2 for the Middle states, $223.1 million for New England, and $201.7 million for the West. Moreover, Southern industries included such enterprises as cigar-making and the processing of chewing tobacco, which would not be very useful in making war on the Yankees. In 1860 the Southern states produced 76,000 tons of iron ore, compared to the 2.5 million tons extracted north of Mason and Dixon's Line. And in the same year Southern iron mills processed less than one-sixteenth of the 400,000 tons of iron rolled in the United States. At birth the Confederate South lacked not only an industrial base, but also the skills, raw materials, and transportation to establish war industries.

Southern capital had long been invested in land and slaves, singularly unliquid asserts. The land and slaves produced-they produced raw staples which were useless in the raw and which as a general rule were refined outside the South. On the eve of war Southern soil grew an estimated four-fifths of the world's supply of cotton. Yet Southern cotton mills were valued in 1860 at about one-tenth of the total valuation of cotton mills in the United States. And armies could neither wear nor shoot cotton bales. Southern farmers raised cattle, but Southern leather products in 1860 were worth $4 million as opposed to $59 million in the rest of the country. Southern farmers raised hemp, but the Confederacy suffered from a severe shortage of rope. There were some sheep in the upper South in 1860, but Southerners had invested $1.3 million in woolen mills compared to $35 million elsewhere in the United States. From the height of hindsight, then, we can see that the Southern agrarian economy in 1861 offered little to a blockaded Southern nation about to engage in protracted, total war. To grasp the economic revolution wrought by the Confederate experience we must constantly recall the military-industrial poverty of its origins.

We must emphasize also two other constants on the liability side of the Confederate balance sheet—the economic role of the Southern army and the rampant inflation which characterized Southern fiscal policy. Both of these factors are and were obvious, but so obvious as to be often overlooked.

Of the 9 million Confederates in 1861, approximately 1,280,000 were of military age, that is, white males between fifteen and fifty years old. Eventually the Confederacy mobilized approximately 850,000 men. With this army marched the Confederacy's hopes of nationhood. Yet an army is essentially a consumer; it produces only security and in the case of the Confederacy sometimes not much of that. The Southern army consumed food, clothing, ordnance, transportation, livestock forage, and more. And of course it consumed these things at a rate much higher than an equivalent number of civilians. Still in an economic context, every Southern consumer-soldier was one less badly needed producer. And this removal of producers from the Confederate economy hurt not only the South's incipient industrial efforts, but also her agriculture.

The other chronic crisis which plagued the Confederate economy involved the spiraling inflation of the currency. On this subject Charles W. Ramsdell has concluded, "If I were asked what was the greatest single weakness of the Confederacy, I should say, without much hesitation, that it was in this matter of finances. The resort to irredeemable paper money and to excessive issues of such currency was fatal, for it weakened not only the purchasing power of the government but also destroyed economic security among the people." The Confederate government, under the guidance of Secretary of the Treasury Christopher G. Memminger, tried to finance the war effort at one time or another by loans, bonds, taxation, and confiscation. When all else failed the Confederacy unleashed the printing presses, flooded the country with fiat currency, and then tried to stay the inflationary spiral by repudiating a portion of its own currency. The effect of the government's monetary policy on Confederate Southerners was incalculable. Wages never kept pace with prices, and salaried men knew genuine privation. Military reverses after 1862 further undermined what shaky faith was left in the currency. In desperation the Treasury Department issued currency "legal tender for all debts private," not public. A government which refused to accept its own money did not exactly inspire soaring confidence. Confederate fiscal policy was characterized by some realism, some blunders, and a pervading illusion that the war would soon be over. It is tempting to scoff at such chaos. But Ramsdell himself conceded, "If you then ask me how, under the conditions which existed in April, 1861, the Confederate government could have avoided this pitfall, I can only reply that I do not know."

Alongside the external problems posed by the length of the war and the federal blockade, the hard facts of Confederate economic life were: (I) the warring South inherited a staple-crop, agrarian economy; (2) inflationary currency was inevitable for a nation trying to carry on a war with only $27 million in "hard" money; and (3) to exist the South depended upon a large armed body of consumers. These liabilities, internal and external, conditioned the economic response to what became a war of attrition. Yet that response, when compared to the antebellum status quo, constituted nothing less than an economic revolution. In contrast to the economy of the Old South, the Confederate Southern economy was characterized by the decline of agriculture, the rise of industrialism, and the rise of urbanization.” - Emory M. Thomas, ‘The Confederacy as a Revolutionary Experience’ (1970) [p. 79 - 82]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i find it more useful to talk about the ways in which disability is made (in)visible (and ways in which disability is made hyper-visible) rather than sorting things into "invisible vs. visible disability" because like. i just don't that that's in line with most disabled people's experiences whether that person would be considered "visibly" disabled or not..? what truly makes someone visibly disabled vs. invisibly because "being able to tell if someone's disabled right off the bat" is way to vague and relies on far too many variables to be anything consistent.

like, some disabled people have very prominent, very noticeable effects from a condition that aren't guaranteed to be recognized as "disability" (just using myself as an example, reduced blood flow to my brain means visible signs like ataxia and slurred speech, but strangers are more likely to read that as intoxication/being under the influence rather than a result of a medical problem, which isn't exactly safe.) is that invisible disability? are my mild gait abnormalities that likely get me read as "weird" at most visible disability? am i invisibly disabled when i'm using a cane or a pair of crutches despite those things being markers of disability? are my variable difficulties with pronunciation due to my muscle condition invisible disability? was my classmate invisibly disabled when CRPS made their hand swell up but everyone still denied that there was anything wrong? at what point do the visible effects of a condition render someone visibly disabled vs. invisibly?

like, what is it that REALLY determines whether a person is visibly disabled vs. invisibly disabled? what if someone has a condition with visible effects that don't go away, but their condition isn't well-known so those effects are likely written off as something other than "they're disabled"?

this isn't about visible bodily differences because that's a different matter. but idk. just something i'm thinking about because people who identify as invisibly disabled and treat this as if its some solidly-evidenced binary and act as if visibly disabled people are this privileged category within our community when that is just now how disability or ableism even works. i don't wanna call it a "spectrum" because that's corny but visible vs. invisible disability is not nearly as clear-cut as some of these people act like it is and i don't think nearly as many disabled people fit into either/or as they think.

like, a pretty staple experience of disability is being disbelieved and doubted and denied care. this gets magnified by things like gender, race, poverty status, body size, etc. rather than by arbitrary standards of "invisible" or "visible." maybe it's that i don't relate at all to the idea that i'm supposed to be invisibly disabled even when the visible effects my disabilities have are mild and change depending on various factors.

i'm not gonna take issue with someone finding "invisible disability" a meaningful way to express their relationship to disability, or visible disability (esp in the case of things like limb differences and prominent gait abnormalities and full-time non-ambulatory mobility aid users, that's not really my place lol), but the way it's discussed sometimes seems annoying and inaccurate and sometimes is even weaponized against those deemed visibly disabled which is. really fucking ridiculous and ableist lol. like i think it should be basic logic that the ones who are the most visible amongst us are the ones that tend to be the most vulnerable to ableist violence and prejudice.

9 notes

·