#some days i think my political views are highly polished and progressive

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hot take, but... yeah, that makes sense

I mean, we should always do our best to reduce harm where we can, but if it's not our choice whether or not someone must seek treatment for a condition, then it makes sense for it to be not our choice whether or not someone is allowed to hurt themselves.

Like with drugs, where addiction can be incredibly harmful - it's not a new idea that decriminalizing drugs and people with addictions helps lower rates of addiction when implemented properly, so I suppose it can be the same with others.

I guess it probably falls under informed consent - if a person knows what they're doing and understands the consequences, expected or otherwise, there's really no reason we should be taking away their right to choose. People who self harm from mental illness should be offered help, people who are addicted should be offered support, someone who needs an abortion should be offered alternatives by pro-life logic (but we all know how that goes - besides, abortion is usually the safer, less harmful alternative), someone who transitions - well, that's pretty much proven to be harmless and incredibly helpful but they should still be offered support in the case of detransitioning.

All that aside, though, it's not up to us what other people can do with their bodies. I mean, if I got sent to a mental hospital every time i picked my skin, I'd never be able to leave.

As for the 'of sound mind' thing, I think it's vital indeed that we specify that the choice to harm oneself (or "harm" oneself in the case of things that aren't harmful but have been defined as such) is not an indication that someone is of sound mind. I mean, what else are we supposed to do when someone harms themselves than offer support - arrest them? Are we going to arrest everyone that drinks, that cuts/burns, that picks, that pulls hairs, that intentionally triggers themselves? It's kind of ridiculous to think of.

I feel like it's kind of like free speech: the government shouldn't be allowed to regulate what you do with your body any more than what you do with your words. On that note, though, if your "harm"/harm interferes with, say, your ability to work safely at your job, it might be time to switch careers - but it first needs to be proven that it's an issue.

i feel like a lot of people kinda don't realise bodily autonomy also must include the right to harm yourself. yeah genuinely. and it makes no difference whether that harm is likely or unlikely, objectively real or ideologically imagined. if you want the government to define what it'll allow you to do with your own body and enforce what you cannot "for your own good" you are 1) basically begging to live in a police state 2) a huge idiot because it will inevitably bite you in the ass when something you do gets defined as harmful

#this is. a really hot take.#i tried explaining it as best as I could#correct me if im wrong#i know i wrote like. an entire essay abt it in this post#but that's not bc i'm sure that i'm right#i'm absolutely not sure about that#it's because i'm trying to make sense of this#some days i think my political views are highly polished and progressive#and usually they are! i think#but then something like this smacks me in the face#and i remember how fallible i am.#i remember that there is always room for improvement#and i remember how important it is to be on the lookout for things like this#because if i don't#i'll become stagnant and in a matter of decades i'll be the -ist old person yelling at the people on the tv#or the hologram whatever#and i don't want that#keep posting y'all#you never know when you'll say something that. really needed saying#that someone needed to hear#seriously though if anybody wants to put this into words better be my guest because i just spit this out of my keyboard in a few minutes

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcus Rashford and the rise of the political influencers

By Tom Westgarth and Walter Pasquarelli

Politicians are not known for their humility. However, as the second wave of the coronavirus swept through Britain, Conservative MP Steve Baker wasn’t afraid to show some on social media.

Baker had been asked by Manchester United footballer Marcus Rashford to allow him to reply to the MP’s Tweet about extending the school meals vouchers given to children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds to a later date (Baker had turned off the ‘reply’ function). Baker replied, arguing that these measures would cause severe economic harm.

But the most interesting part of Baker’s response wasn’t the economic claim. His response stated: “You have 3.4 million followers Marcus, to my 96k. The power is yours here”. The white flag of surrender had been raised; Baker’s relatively smaller following meant that he had lost the online argument. The government later pledged £400 million to tackle living costs over the next 12 months for the most disadvantaged families.

Despite being one of the most influential backbenchers in the country, somebody who has one-to-one’s with prime minister Boris Johnson; how did Steve Baker succumb to feelings of powerlessness in the face of a footballer? At what point did a combination of an inspirational backstory and enormous online presence become more pivotal to shaping public policy than being an elected official?

The answer to this question cannot be realised without understanding ‘influencers’. Defining an ‘influencer’ is actually surprisingly hard to do, but they can essentially be described as individuals or small groups that exert a topical influence over a certain group of people through their online presence.

This could take the form of vloggers via their YouTube channel, or celebrities who are highly active on social media. Whilst Rashford’s initial celebrity came from a more traditional background (as a sports star), his consistent online activities mean he likely falls into such a bucket. Vlogging to a camera and casual tweeting evoke a sense of ‘relatability’ that distinguishes influencers from regular celebrities.

Internet sensations of this kind are highly sought after by brands, who pay them handsomely to promote various kinds of products. What gives these brands the bang for their buck is not the influencer’s industry knowledge, but the charismatic authority they exercise.

Despite this, many may dismiss influencers as irrelevant to social affairs. Critics lambast them as superficial figures that care more about views than values. They are often seen as symbolic of a generation glued to their screens on platforms that are eviscerating adolescent mental health.

But what these attacks on influencers appear to miss isn’t to do with their values. It is that their power is significantly underestimated. Part of the reason why the British government made such a hash of the Rashford-school meals saga was that they failed to predict the cut-through that a young, black footballer would have with the wider public.

Not every influencer has the sort of power Marcus Rashford has. But the political domain has evolved to a point where there are more than a handful of Rashford-like individuals out there. Governments and political parties need to recognise this, as influencers will increasingly start to engage in political activity.

***

At the heart of this trend is an ongoing seismic shift as to whom we trust and ascribe authority of knowledge production. Now, this did not happen overnight of course, but it is part of an ever changing historical process.

In the beginning there was God. For centuries the church and its representatives were seen as the sole and only fountain of truth.

Then came science. In a large part of the West, science replaced religious belief as the main source of truth. The scientific method offered an alternative to the dogmatic teachings of the church, allowing flexibility to approve and reject previously-held beliefs as our methods and accuracy of inquiry evolved.

Such progress produced the internet. This provided everyone with a voice and ability to both obtain as well as disseminate information. But online, often authority can be associated with whoever shouts the loudest.

Academic and intellectual institutions, seen as the bastion of scientific progress, now come under fire. Facing charges of group think and reductive analysis, they no longer possess the same authority as they did in previous decades.

Simple analysis, and social media platforms that prefer disseminating information through retweets, shares and followers, are what makes the age of influencers so prevalent. It is under these environments that influencers are emerging as a new voice of trustworthiness, providing an alternative source of truth and knowledge. The follower count, amount of engagement and interaction have become a direct source validating their credibility akin to academic citations.

The internet and digital technologies created a vacuum as to who should be wearing the crown of trust. With traditional sources of authority becoming ever-less relevant, influencers have become credible actors for filling this gap.

*** It would be a mistake to ascribe influencers' success merely to some shallow numbers though. There is a much deeper connection, a unique relationship that they build with their followers, which makes them crave for new content like the new season of a real-life character from their favorite Netflix series. The intimate nature of this informational distribution, where a creator is speaking down the lens of their camera, makes viewers feel as if they have a special relationship with the influencer - which is a trait that fundamentally distinguishes them from celebrities who are perceived as being polished, even from another planet.

Kenneth Burke described this phenomenon in his 1969 piece “A Rhetoric of Motives”. Burke explained that humans have an urge to identify with other groups and people. As biologically separate beings, humans seek to overcome this state of separateness through communication, music, red MAGA caps, you name it.

In times of identity politics, when voters formulate their political priorities based on the identity they espouse, influencers are set to accumulate increasing power over setting the tone. Influencers speak like you and I, fire updates in a continuous loop, broadcasting a shared sense of identity unifying a critical mass of people under a common purpose.

It is this cocktail of omnipresence and relatability that creates a weird attachment and ultimately loyalty - the most valuable currency in the political casino.

***

The UK government thought they had seen the last of Rashford over summer, once they had awarded him an MBE. Many viewed this honour as a cynical but deserved ploy to keep the Manchester striker on side. Of course, somebody as driven by the issue as Rashford ploughed on, forcing the prime minister to call the 23 year-old in order to assure him that the government was on the right track. This should serve as a case study for governments worldwide trying to work out how to engage with powerful influencers on matters of public policy.

Should they bring them on side, early doors, in order to keep them within touching distance? People are less likely to decry governments if they have a seat at the table.

The answer to this depends on several factors. One is, of course, the issue at hand. A less controversial issue may warrant greater collaboration. For example, the Sidemen, a group of British YouTubers with over 10 million subscribers, made a widely shared ‘Stay at Home’ video during the first wave of COVID-19. However, anti-establishment parties, in turn, could use influencers to destabilise the status quo from the outside.

Eventually, there may well be a point where such influencers decide to become politicians themselves. In the game of politics, the ability to carry millions with you on issues that one cares about is a highly valuable currency. If it is possible to have the adoration that many have for the likes of Trump, Farage and Johnson, without the detractors, then this makes for unbelievably powerful leadership qualities.

Objections to this belief are reasonable. Currently, influencers curry favour with a young audience that is widely geographically dispersed. In many voting systems, this will mean that building a significant coalition of support would be tough.

However, many influencers are moving away from youth-facing platforms into the ‘mainstream media’. KSI, a British YouTuber who came to fame playing FIFA in his bedroom, is now a chart-topping rapper. He twice sold out huge arenas to have a boxing bout against American vlogger Logan Paul (whose own charisma helped him recover from major controversies). These stars are by no-means ‘staying in their lane’, meaning they will capture both traditional and new forms of public life. When will we have our first YouTuber politician?

Finally, there seems to be little sign that Marcus Rashford is stopping. Not only has he released a BBC documentary on food poverty, he has partnered with publisher Macmillan to promote reading for economically disadvantaged children. Maybe he will stand for parliament one day, maybe he won’t. What is clear, though, is that influencers have the potential to become serious political players in the issues of tomorrow. But perhaps this time the politicians in question won’t come of age playing at Eton, but playing Esports.

Tom Westgarth and Walter Pasquarelli are policy consultants at Oxford Insights. They specialise in understanding trends in emerging technologies and AI.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cold War (2018) | Directed and Written by Pawel Pawlikowski

Before getting into Cold War, as a prelude, I’d like to mention a funny documentary the filmmaker Pawel Pawlikowski released back in 1991 called Dostoevsky’s Travels. It follows the great-grandson of the famous Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky who died in 1881. Fyodor is generally known as one of the greatest writers of all-time and possibly one of the first modern psychologists, deeply probing the human soul in his work. Great-grandson Dmitri drives a tram in Leningrad, Russia and agrees to go on a speaking tour about his “prophet” Grandfather. He doesn’t do this to pay his respects, but only because he dreams of scraping together enough money to buy a used Mercedes to impress his friends. And he is OBSESSED with buying a Mercedes and knows nothing about his Great-Grandfather. He talks to crowds of intellectuals and hardly has anything to say about his kin Fyodor and just wants to get paid. He buys one Mercedes and it breaks down immediately. He then buys another at the end of the documentary and it gets stolen by bandits. As the doc progresses you see Dmitri is a bit of a numb-skull and a scoundrel. I liked it due to the irony of Dmitiri’s complete uncaring attitude towards Fyodor’s highly regarded esteem, and obviously this absurd infatuation with acquiring a used car as a status symbol compared to his novelist grandfather, who is held up so highly for his spiritual profundity and depth. It’s a great piece of work no one has heard of...part-cautionary Capitalist tale at the end of the Soviet Union, while Cold War is part-cautionary Communist tale post World War II.

Official Trailer for Cold War

youtube

Intro and Technical Specs

To start, my main fear of writing about films I love is that it will suck the joy out of the film itself by looking at it so closely. I have only written in depth about two films, and thus far, am finding it to be the opposite. When going under the microscope, I am just becoming more aware how great a truly well-made film is when breaking it down.

Cold War may be the most beautiful black-and-white film I’ve seen. The category Amazon has placed it in is “Arthouse Drama”. Amazon Studios also is the distributor of the film. My guess is because it did very well at the Cannes Film Festival and Pawlikowski won the Oscar for his previous film Ida in 2013. Sometimes they get it right. To give some more context, I am very familiar with Ida and studied it for research for making my latest short film. I found it interesting Pawlikowski implemented a particular style similar to filmmaker Paul Schraeder’s book, “Transcendental Style in Film”. One aspect of this style pertaining to Ida is the cinematic framing for the action and not moving the camera until the end. He framed his subjects in a squared 4:3 aspect ratio while leaving lots of headroom, sometimes leaving them in the bottom corner of the frame, which carried over to Cold War. I don’t exactly know why he does this, but I have some theories that I will flesh out within the post in depth. While watching, I immediately noticed the grain in the 4K version. I looked it up and the film was shot with an Alexa digital camera and also a 35mm film camera, so apparently they were able to mimic film grain with the Alexa in post to match. A 32mm lenses was used for almost all the shots. According to Pawlikowski it was because this focal length closely mimics the viewing width of the human eye and allows a wide space of action that can fit around the subject(s) in the frame. Similar to Ida, there is no non-diegetic music in the film (music added outside of the film’s music itself) until the closing credits, reminiscent of the French director Bresson.

Opening in Rural Poland

The film opens on the hands of a man playing an instrument that resembles bagpipes, looks handmade and I assume is indigenous to Poland. The camera tilts up to reveal a bright-eyed rural man, and eventually pans over to another interesting looking character playing a violin as they sing together. We soon learn that Wiktor (one of the protagonists) is traveling with two others (Irena and Kaczmarek) and they are recording various forms of folk music unique to the Polish people. Kaczmarek immediately degrades this type of music as “possibly crude” or “too primitive” immediately marking a divide in perspective compared to Irena and Wiktor, who visibly enjoy interacting and recording the villagers’ authentic music.

They soon come to a house where a unique-looking dirty village girl sings a song not accompanied by any instruments. She has deep-set eyes and looks slightly haunted, and the lyrics of the song are about unrequited love. Not a happy song. Wiktor and Irena are enraptured by the raw singing and are recording this. In contrast, Kaczmarek disinterestedly eats soup in the next room, spoon klanking against the bowl, probably interfering with the recording. Kaczmarek is representative of the Communist State for this film, high on bureaucracy and lacking in soul. The song being sung by the little girl is a huge part of the film as a whole. Little do we know (and probably not evident to most who have seen the film) the lyrics tell the story of what happens between the protagonists we are about to follow in the film. The song is called Dwa Serduszka (Two Hearts) and is an authentic Polish folk song like much of the music in the movie. After watching for the first time (I commonly do this) I went online to look up background information and found a very well-made youtube video essay describing the song as being the “Leitmotif” for the film. Leitmotif is a term defined as “a recurrent theme throughout a musical or literary composition, associated with a particular person, idea, or situation”. In this case, the song operates as a direct pointing of what is to happen. The song pops up several times throughout the course of the film, forecasting the fates of the two protagonist lovers, Wiktor and Zula, who are brought together by music.

This “forecasting” I believe goes deeper. It’s as if it is pre-determined. Pre-determined due to the current political environment in Poland and the two characters’ difference in personality and upbringing. Also, most importantly, is because they love each other in a way that seems beyond their control and not a choice, eventually becoming impossible for them to live life without one another. The leitmotif reminds us throughout the film of Wiktor and Zula’s inability to escape their fate, which is already etched in stone by powers beyond their will: Two hearts four eyes Crying all day and night long Dark eyes, you cry because you can't be together You can't be together My mother told me You mustn't fall in love with this boy But I went for him anyway and love him until the end I will love him until the end

youtube

Folk Ensemble

Now we are at a large building which looks to still be in the rural area. Auditions are going to be held here for singers and dancers for a folk ensemble performance. A couple of trucks haul the commoners in and Kaczmarek gives a stately speech to the bunch before cutting inside to everyone waiting to audition for Wiktor and Irena.

We then meet Zula waiting. She elects to audition with another girl, naively, rather than shine in the audition solo. They enter the room to sing for Wiktor and Irena. Wiktor is immediately transfixed and asks Zula to hold on and asks her to sing another song alone. She sings with an authentic, untrained beauty. We also see her feistiness here. It’s obvious Wiktor is smitten and she is marked down to be selected as one of the singers after they exchange a parting look. By now, the framing style of the cinematography is noticeably unique compared to other films. As mentioned in the intro, characters are often framed with lots of headroom and sometimes placed in the bottom of the frame, leaving it mostly open space. My theory on this is that the environment the characters inhabit are shaping their destiny more than the characters’ own free will, therefore their heads are often seen at the bottom with action on top and around them. For example, Communism looms larger than the individual, tamping he or she down (literally) to the bottom of the frame. Not only Communism, but their uncontrollable love for one another, the characters’ upbringing and the people around them with their general wants and needs. These factors shape their present and future more than their own willful, self-determination and I think the filmmaker is aware of this fatalism, yet doesn’t just come and say it because that wouldn’t be interesting. We just see that Wiktor and Zula are never able to comfortably settle anywhere with their love nor escape the love they feel for one another, making their situation impossible due to the circumstances. In Ida, duty to God looms large and so does the characters’ Jewish unknown family past (to only name two) and the shots are framed accordingly as well. On a broad level stepping outside of the film, what’s interesting to me is how much free will do humans actually have and how much is self-determinant? After studying the film closely, this is the deep question (not answer) that I came to that transcends the surface story.

Wiktor watches Zula from a distance outside that evening. Irena then tells him Zula killed her father and did some prison time for it. After rewatching, I suspect that Irena loves Wiktor, and there are a few subtle cues later on that I noticed as well. During private lessons, Wiktor curiously asks Zula what happened between her and her father while Wiktor plays scales on the piano and she matches the notes with her voice. Zula says her father tried to be sexual with her so she stabbed him. It is a very matter-of-fact and short answer. Wiktor doesn’t say anything and continues playing the piano. I’ve thought about this scene more so than any other scene after rewatching. I think it is because of the dialectical nature of Zula saying she stabbed here Dad because he tried to have sex with her, one of the darkest things you could imagine, then the slight humor of Wiktor’s reaction while seamlessly transitioning back to the softness of the piano and her soft voice syncing. Wiktor is very watchful, internal, reserved, most likely from a more refined family and musical background. Zula is tough, spirited, tenacious and has lit a fire in Wiktor. Wiktor is tall and dark-haired. Zula is short and blonde. Opposites!

It is now time to perform for a large audience in a theatre. Wiktor conducts. Zula and about 20 other girls in Polish folk attire sing the leitmotif song that was sung by the young girl earlier. The group sings beautifully. Zula shines in front. Even Kaczmarek on the side of the stage behind the curtain seems to be in awe and carefully walks about as if not to disturb the magic.

Afterwards there is a reception. Wiktor and Irena lean against a large mirrored wall and everyone else in the room is seen in the reflection. When you first watch it, it takes awhile to figure out the orientation of the room due to the mirrored wall. I think this is the most interesting shot of the film. Kaczmarek then gleefully enters frame and says that the performance was so beautiful, calls Wiktor a genius and says it’s the most beautiful day of his life. He really means it and is the most authentic emotion we see from him in the whole film. Previously, Kaczmarek thought all this “folksy stuff” was foolish. There is a funny moment between the three. Wiktor and Irena are obviously moved by this but not sure how to express it as the stately Kaczmarek leans against the mirror with the two. On a second viewing, one sees Zula in the reflection staring at Wiktor the entire time. The two make love soon after in a bathroom at the party.

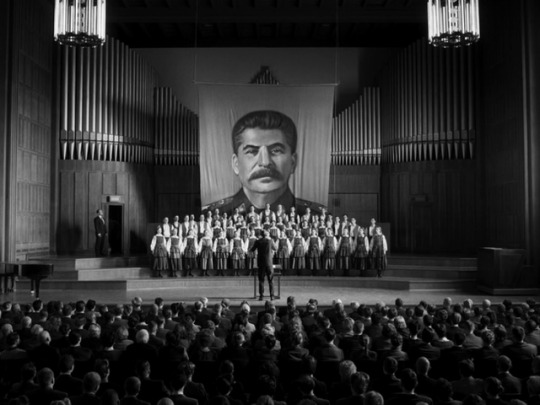

The Ensemble + The State

The performance is so good, now the State wants to get involved and meets with Wiktor, Irena and Kaczmarek. The government wants to turn the repertoire into a “calling card for our Fatherland” and incorporate “Land Reform”, “World Peace” and a strong number about the “Leader of the World Proletariat”. In return the group will be held in high favor, able to travel to other countries to perform, etc. Irena and Wiktor are visibly uncomfortable with this. Irena speaks first and says thank you but the ensemble is about authentic folk art and the rural population doesn’t sing nor understand these difficult issues. Kaczmarek quickly intervenes and calls the man from the state “comrade” and says the ensemble, on the contrary, will do this after given proper direction. Irena stares him down. Wiktor says nothing. The next performance is stained by a huge tapestry of Stalin behind the singing ensemble. The tone now is more dutiful rather than soulful, as if singing a church hymn they are forced to sing. Zula’s face while singing now lacks the life it possessed in the performance before. The State must extinguish all individuality and uniqueness with the goal to homogenize. Irena’s heart looks broken in the audience. Everyone dutifully rises for applause afterwards and Irena walks out. We do not see her again in the film. Everything has changed.

The stuffiness of the singing troops is saved afterwards by a beautiful shot of Wiktor and Zula laying in a golden wheat field together at dusk. Golden?? The film is in black and white but my mind says “golden”. Birds and crickets sing. Tranquility away from the group.

But it doesn’t last long, as they are unable to run from the larger outside factors. Zula soon confesses that she reports on Wiktor to Kaczmarek about their relationship and the things he tells her. She says it’s because she’s on probation for something and assures Wiktor that it’s nothing that will hurt him, but Wiktor gets up and walks off angrily at a loss for words. As mentioned, the scene starts with their eyes closed as if in a dream, beyond the State, but it's inevitable that the state has to enter their relationship at some point, infecting the dream, and will remain a problem for the rest of their lives. Zula calls him a “bourgeois wanker” as he walks away and she reacts oddly by jumping in a nearby river. As soon as she hits the water, Wiktor stops and turns around. She floats in the river and begins singing the leitmotif song.

The next shot is of the two silently sitting together again in the wheat field at nightfall with a campfire going. Zula’s hair is wet. The two just stare at each other and never say a word. What are they thinking? I think Wiktor is thinking that he can not escape her because of his love and that they are stuck! Zula knows this too. This is a type of love that transcends choice. Just like the State, their love controls them. The silent shot in nature cuts to black, then diverges to a busy train station with a brass band as the ensemble leaves to go to Berlin for a show. Kaczmarek gives a stately speech to the group about their trip. Wiktor meets Zula privately in a train car and lays out a plan for their escape once in Germany to go to France. Zula is nervous she will not be able to make it somewhere other than her homeland Poland due to her inability to speak French and lack of experience. I doubt she has any family to rely on, and at the moment has the ensemble in Poland as a decent occupation. Wiktor assures her she has talent to learn and the most important thing is they’ll be together. They kiss. The performance in Berlin is shot very uniform and proper, perhaps further pointing to its newfound soulless rigidity. Afterwards, Wiktor goes to the meeting place to cross the border. Zula remains at the reception with the comrades and Kaczmarek (as if in a trance) and never shows. Wiktor waits until nightfall and eventually stiffly walks across without her.

Defection

Wiktor is now playing piano in a cool jazz night club in Paris with a band. It is 1954. His beard is now grown out a bit and his hair messier than before. He is now in an empty cafe at closing time and speaks French with the waitress. He seems to have assimilated well here. It is revealed he is waiting for someone. That someone is Zula. She eventually walks in and they stare at one another for a few moments. One look at Wiktor while sitting across from her shows how much he still loves her and has missed her. The actor playing Wiktor, Tomasz Kot, really shows this wonderfully. He is very good at being still yet showing so much. Regarding the performances, this is one of the most authentic love films I’ve seen in a long time. And an expert director and writer doesn’t hurt. The film never feels sappy, in my opinion, while simultaneously remaining very romantic. Zula doesn’t show much and stays cold during this scene, but can’t help but ask, “Are you with someone?” Wiktor is. So is she. He asks if she’s happy. She isn’t, but doesn’t say it. Wiktor knows and walks her to the hotel. She says she wasn’t good enough, not as good as him, to make the escape from Poland to Paris. Wiktor says he believes love is enough. Zula coldly kisses his cheek and then stolidly walks away. Wiktor watches her go. But eventually Zula breaks! She turns back around, walks quickly back and they kiss passionately for a few moments before she leaves again. If one just read this and didn’t watch the film, you might think it seems like any other love story you’ve seen a million times. But to me, because of the authenticity of the performances and lack of constant soundtrack music, it really felt great to see these two embrace again. And I think it proves that moments in movies that may look cliche on paper can be pulled off with a skilled filmmaker and actors. Also, there’s only a few angles that the camera covers in this scene and ALL the scenes really! There’s a graceful economy and no superfluous closeups with unnecessary dialogue. And as mentioned, no outside music booms in like most films commanding you to feel something! You feel it because you feel it, not because you’re told to feel it with an over-bearing soundtrack trying to compensate for lack of performance or direction. Wiktor now walks into his apartment, smokes a cigarette alone deep in thought, then gets in bed with his girlfriend. He tells her he’s just been with the woman of his dreams. She doesn’t seem to care and turns around to go to sleep, highlighting the lax and blase nature of their relationship and possibly Paris artist life as a whole. Wiktor then turns off the lamp and looks up at the ceiling in lovestruck thought.

We are now in Yugoslavia in 1955, which looks much more lush than I would’ve imagined Yugoslavia. Wiktor gets off the train to attend a performance of the ensemble. Kaczmarek quickly greets him at the front of the theatre and is oddly cordial and confident in a sharp suit. Once inside, Zula sees Wiktor in the audience and looks startled. Wiktor looks side to side and men are watching him from the aisles. He is escorted away by authorities yet remains adamant to see Zula rather than be afraid of being thrown in jail or hurt. The first time I watched I thought he was definitely going to be thrown in prison. Kaczmarek obviously ordered the men to take him away and send him home in a train before he could see Zula, because of Kaczmarek’s interest in Zula.

Zula and the ensemble are shown singing the leitmotif song now. Zula notices Wiktor is no longer in his seat. Perhaps he was escorted out at the intermission. She sings with a melancholic intensity. The black-and-white contrast is especially beautiful here, maybe more so than anywhere else in the film. There is a black back drop and all of the singers’ alabaster skin glows, as well as their folk costumes.

Wiktor is back in Paris now and has gotten work as a Film Composer. Two years has passed since the Yugoslavia concert. While in the middle of working on the soundtrack, the side door of the sound stage opens. Wiktor is spellbound as a smiling Zula is revealed.

Zula has married an Italian so she could legally move to France. She says the marriage doesn’t count though because it wasn’t in a church. Neither seem worried about it. This time Zula does not hold back her feelings and, obviously, neither does Wiktor. They make love. They ride on a boat down the Seine at night past the buildings and cathedrals. They messily and drunkenly dance alone at a night club in rapture. Heaven for a moment.

Which begins Zula’s vast transition from the performing rural ensemble in Communist Poland to a solo singer at the Paris jazz club with Wiktor’s band. She sings the emblematic Dwa Serduszka most wonderfully here. Order. Everything in it’s right place. She is luminous as the camera slowly dollies around her, eventually revealing a packed club. Everyone is captivated and still. Then at the end is a lovely moment, maybe my favorite moment of the film, where Wiktor is staring at her intensely and she turns to check in with him and he gives her a nod of approval. It’s almost corny, riding the edge, but is powerful, conveying a silent understanding between the two seeing one another perfectly clearly.

Poles to Parisians

We now are at where Wiktor and Zula live, which looks like a cool version of a converted attic with a Paris view. Juliette, Wiktor’s ex, has translated Dwa Serduszka from Polish to French and Zula is unhappy with the translation, which most likely includes some self-consciousness about her pronunciation. The manner is which the leitmotif song appears here runs parallel to the first step in the descent of the relationship in Paris. Zula is defensive and anxious about the Parisian artistic circle Wiktor has introduced her to and she drinks to ease the anxiety of feeling inferior. Wiktor tells her not to because she is “charme slave” as they say, alluding to how everyone has a narrative role and label in these circles. Zula is becoming difficult and insecure. Wiktor is becoming caught up in the scene and ignorant of Zula’s dramatic change of environment.

The film director at the party looks Zula up and down when they arrive. Wiktor allows this without rebuke, most likely due to the nature of the sexually-lax Parisian art culture. Everyone is beautiful and chic at the party. Zula immediately goes for the drinks. She then sees Juliette and approaches her abruptly (yet with restraint for Zula), subtly challenging her French translation of Dwa Serduzska. Juliette calmly explains her reasoning according to the lyrics’ metaphors. It’s obvious Juliette sees through what’s happening in the situation here.. Juliette’s part is small but the actress is excellent and conveys a lot. She eventually mentions how the transition to Paris must’ve been a shock...the cafes, cinemas, shops, restaurants. Apparently Juliette sees this shock more than Wiktor does. Zula tries to play it cool here but you can see she’s flustered. This is a game she’s not used to playing. She then retorts that her life in Poland was better.

Wiktor is talking to someone and looks over and sees Zula and the Film Director sitting closely, flirting. Zula glances back over at him to see if he cares, but Wiktor stays put. Then later she aggressively confronts him about giving her story “more color”. It is apparent now that he has enhanced her Polish story to seem more dramatic in order to captivate his French friends and colleagues. Wiktor shrugs this off. Zula’s vibe is not carefree and cool like the rest of the party with her straightforward, intense rawness which creates an isolation for herself. She sits in the bathroom now alone, drinking from a bottle, talking to herself in the mirror. She calls Wiktor a jerk, but then says she loves him. She calls herself an idiot at one point. She continues to talk in the mirror as if to console herself. And I can’t help to mention how much she looks like a young Gena Rowlands here. It reminds me of the 1968 film Faces, which is also black and white. They look so much alike, and both fantastic actresses that are blonde, voluptuous and troubled.

Gena Rowlands in Faces (1968)

Joanna Kulig in Cold War (2018) Wiktor, unknowingly and excitedly, opens the bathroom door and says that they’re all going to the Jazz Club now. Zula says she’s a bit sad and wants Wiktor to come in the bathroom with her, but he ignores this and says let’s go. She takes a moment to herself and then it cuts to the club. She looks miserable and wasted sitting at the bar. As we go, I am still noticing the framing I mentioned at the beginning with the subject at the bottom, but for this shot she really seems low!

Her melancholy is interrupted by an upbeat, American song (”Rock Around the Clock Tonight”) and she gets up reinvigorated and starts dancing enthusiastically with a few different guys. The camera goes handheld and is the messiest camerawork of the film (a good messy). She eventually gets sloppy and gets on the bar and almost falls and people drunkenly cheer as Wiktor exasperatedly watches.

youtube

We then see Wiktor carrying her into their room. Zula says he is no longer a man in Paris like he was in Poland, and says she and the director get along well in attempt to get under his skin further. He then sits alone in the dark and smokes a cigarette.

It now cuts to Zula in a sound studio singing into a mic in French. I don’t speak any French, but her accent and pronunciation feels correct, but her spirit is muted...and we soon see one reason why. Wiktor’s voice ominously interrupts her over a speaker behind glass in the recording booth. Now the shot is on him and he looks disheveled and dark and tells Zula they only have 40 minutes left and not to blow it. There is a deep hate in his eyes we haven’t seen yet, perhaps retribution for calling out his manhood and their recent relationship woes. An engineer and the film director are also in the booth. There is just a bad energy in the room and anyone that’s ever tried to perform anything would be able to detect how difficult it would be to bring a great performance here. The music starts back up and Wiktor looks down as if disappointed right before she starts singing.

We are at a listening party now for Zula’s record at the French Director’s apartment. Zula is standing in the middle of the room alone, listening intently as several others sit around in the background drinking champagne. Dwa Serduszka plays, but now in French. It’s okay but not great. It doesn’t have the soul that it had before in Polish. I’m trying to put my finger on it, but the French seems a little stiff and the vocal track seems extra-produced. Too loud and too clear when mixed with the band’s instruments and it’s just not what it was before like the first time at the jazz club, for example. Again, this leitmotif song is also a metaphorical indicator for the stage in the relationship. She looks over at Wiktor who is cooly leaning on the wall off to the side (maybe too cool) and gives Zula a nod similar to his nod after the jazz club performance. But this nod doesn’t have the effect it did then and seems oddly forced. The record playing here in this posh Paris apartment compared to the Polish rural girl singing at the beginning of the film is night and day. It’s obvious why, if you think about it. They’ve taken a folk Polish song, translated it to French for a rural Polish singer, then recorded and produced it in a slick Paris sound studio under difficult conditions. How could the quality not suffer a bit?! Another example of the larger outside obstacles making it impossible for them, even in a free society like Paris, France.

It cuts to them now walking home afterwards. Immediately it’s apparent Zula is unhappy. Wiktor recognizes this but apparently didn’t know while at the party. As they pass a fountain next to the street, Zula throws the record in <splash> yet continues to mostly hold her sadness in, which has become more of a depression at this point. Assimilating is one thing, but they have gotten into this habit of holding back and not being up front, maybe due to the social circles they run in now. Zula cooly mentions that the French Director has fucked her well 6 times and "not like a Polish artist in exile,” which causes an eruption in Wiktor (what she wanted) and he slaps her.

This is strange to mention but, technically, the slap doesn’t sync with the sound. Lol. I watched this part 3 or 4 times to make sure and it just doesn’t (unless there was a lag in the internet connection). Maybe nobody else notices this, but I’ve had to edit-sync slaps, kicks and punches before many times on this very computer and immediately saw something didn’t look/sound right. After the hard slap, Zula raises up and says, “Now we’re talking”, which is sarcastic but also the truth. Often one needs a crisis moment to break out of a behavioral habit and apparently the French translation broke the camel’s back. The next day Wiktor frantically goes to the Director’s apartment looking for Zula. He stomps through the rooms looking for her. The Director then says she went back to Poland. Wiktor slowly walks out of the apartment with a terrified look on his face. Wiktor has become unhinged and plays maniacally on the piano at the Jazz Club. The other band members just stop playing and look at him as he bangs on the keys in isolation. There is some slight comical levity here for a couple of seconds due to the look on the clarinet player’s face. You assume Wiktor has lost his job. He is now miserably pumping coins in a phone booth for talk time to find out where Zula is in Poland. Afterwards, Wiktor goes to what I assume is an embassy. A Polish man at a desk tries to dissuade him from leaving Paris and going back to Poland. You can see the Eiffel Tower outside the window as the man asks Wiktor why he would ever want to leave this place. He says Wiktor doesn’t exist anymore to Poland because he left and let down all the young people he worked with. The man takes a drink from his cup and reacts as if he’s spiked it with something strong, perhaps how he’s able to get through his job. He then mentions there is a way Wiktor can go back if he truly regrets what he has done.

The Exiles Return

It is 1959 and we see Zula back in Poland on a dreary, crowded train with peasants. Soldiers whistle at her as she walks on a snowy road. She has come to visit a very broken, gaunt Wiktor who is being held prisoner by the military for being an exile. He says he has to be here for 15 years and got off lucky. Zula gives the guard what I assume are cigarettes which buys them 10 minutes alone.

His right hand has been beat severely. They kiss and Zula says she will wait for him. Wiktor tells her to find someone else, but Zula says she will get him out.

Cuts to 1964, 5 years later. A performing Zula is on stage singing a ridiculous Latin-infused song with a black wig on, resembling a late Judy Garland. She looks overweight and drunk with her comical, sombrero-wearing band. We now see an older Wiktor backstage with Kaczmarek who is holding an unhappy, despondent child. Kaczmarek doesn’t look like he’s aged a bit and still has a detached soullessness about him. With Kaczmarek, you wait for him to be rude or mean but he is not. He always stays at a steady, robotic hum of cordiality. It is revealed Wiktor can no longer play music because he can no longer use his right hand. It is also now apparent that Zula married Kaczmarek in order for Wiktor to be released. Zula now comes off stage and walks quickly toward them but drunkenly falls down. She manages to rapidly get up and falls directly into Wiktor’s arms, completely disregarding Kaczmarek and her son. They go off to the restroom together and sit on the floor staring at one another. Zula pulls off her wig, perhaps finally able to shed this horrible identity she's had to create to survive.

She asks him to get her out of here...for good.

The two take a crowded bus and get dropped off on a country road next to a lovely field. They look slightly rejuvenated but stolid.

Early in the film, Irena and Wiktor sat in the van while Kaczmarek took a walk to take a pee. Kaczmarek then aimlessly walked into the ruins of this old church. He looked around, then left...point being we’ve seen this place before. And earlier, even Kaczmarek’s face showed a certain amount of reverence for this old church and felt the power it gave off. Wiktor and Zula now enter this same church. There is a circular hole in the ceiling, perhaps so God can see them.

They now kneel with a candle lit in front of them on an alter with a row of white pills. They have a brief, simple marriage ceremony. They both have a glow to them. They cross themselves and mention God. They ingest the pills.

They kiss.

They then sit on a bench at dusk and look out into the field, holding hands, quiet.

You can hear the insects and an occasional bird chirp. Both have dark circles under their eyes. It’s so beautiful yet so sad. Zula then says, “Let’s go to the other side. The view will be better there”. They stand and go, leaving an open frame. A gentle gust blows the wheat from behind where they were sitting. Perhaps God’s sigh...

This last time I watched, the ending really got me...and is powerful now as I write about it. As mentioned in the intro, Pawlikowski’s last film Ida incorporated a particular style. Pawlikowski never moved the camera until the end of that film, so when he did the viewer would be raised up in a transcendental way as the first external music came in, lifting us from the real world for a few moments. I think he did the same thing here with Cold War in a different way. The moment of transcendence for this film comes at the end also but not with the movement of the camera but with the movement of the wheat behind the bench before cutting to black. This film is high on realism, but this gust is something otherworldly, therefore a powerful contrast from the stark, real world tribulations previously in the entirety of the film up to this point. This is what makes it so heartbreaking and beautiful and poetic all at the same time. And also, for a moment, the viewer might weigh whether the fate of Wiktor and Zula is so horrible after all. “for my parents” appears before the credits, pointing to the fact that the story is based on the filmmaker’s parents’ true experience during that time period. Bach’s Goldberg Variations comes in and you know it’s Glen Gould when you hear the humming, which I don’t necessarily like but it doesn’t ruin the mood. Bach was also used for the ending of Ida and is also the only non-diegetic music used for Cold War.

In conclusion, I think every great film has to have a surface story that one can follow and then a large idea hidden within that story (or as a result) to meditate on which includes something deep about the human condition. With some films, one has to work to find out what that larger idea is. For future posts, I may try to specifically focus on this “larger idea” rather that breaking down the entire film. This often appears as a question, not an answer, and Cold War does this masterfully.

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Sen. Elizabeth Warren played to a friendly crowd when she visited Brooklyn last week. The rally at King’s Theatre on Flatbush Avenue — an ornate people’s palace kind of joint with fleur de lis in the molding and vaudeville ghosts in the rafters — was a 4,800-person shot in the arm for her campaign, which had been flatlining of late. Julián Castro, young, Latino and recently out of the presidential race, had just endorsed Warren and there seemed to be a sense in the air — with a heavy hint from the mass-produced “We Julián” signs circulating — that the campaign was looking for a little good news out of the evening. The crowd scanned as largely young and professional, and a little girl sitting just in front of me waved another sign: “I’m running for president because that’s what girls do.”

Just under a week later, the Warren campaign would be at war with Sen. Bernie Sanders over Warren’s claim that Sanders told her in a private 2018 meeting that he didn’t think a woman could win the 2020 presidential election. This salvo from Warren’s camp was seen as a response to reports that talking points for Sanders volunteers characterized Warren as the choice of “highly educated, more affluent people,” a demographic both key to Democratic electoral success and associated with Hillary Clinton’s supposed out-of-touch elitism. Within a few hours, what had been a cold-war battle to define the left wing of the Democratic Party had gone hot. The handshake-that-wasn’t between Sanders and Warren at Tuesday night’s debate seemed to inflame tensions even more.

What’s curious, though, is that the rift isn’t over policy particulars. The Warren vs. Sanders progressivism fight seems to be more stylistic, an unexpectedly tense class war of sorts within the broader progressive class war. Should progressive populism be wonky and detail-oriented and appeal to college-educated former Clinton voters? Or a more contentious outsider assault on the powers-that-be from the overlooked millions of the middle and lower-middle class?

The groundwork for more open hostilities was perhaps laid at the start of last weekend with some numerical tinder. As I boarded a plane for Des Moines, Iowa, on Friday night, I scanned the results of the just-released Des Moines Register poll. The survey showed Sanders leading in the state with 20 percent of the vote, a notable shuffle in the race from the last poll from that pollster, which showed former Mayor Pete Buttigieg in the lead and Sanders scrapping for third place with former Vice President Joe Biden. Saturday afternoon I found myself in Newton, Iowa, listening to Larry Hurto, 68, reciting the full results of the poll to me from memory as he waited for Sanders to arrive at a rally. With Sanders, Hurto told me, “What you see is what you get.” Kim Life, 60, told me she’d voted for Clinton in 2016 but felt that, this time around, Sanders was the man for our times. “Things in the world are so unstable,” she said. “He hasn’t changed in 40 years.” Warren, she told me, was more influenced by corporate America than she let on.

Variations on this theme — Sanders as credible progressive curmudgeon and Warren as vaguely deceptive opportunist — popped up as I followed Sanders across the state. America is a country whose politics are pheromonal; voters are largely attracted to certain candidates not for their policy positions but for the cut of their jib or the familiarity of the story at the heart of their self-mythology. And among the Sanders-committed, there seemed to be a sense that the candidate’s famous frankness was his greatest asset — and it could well be with certain groups.

The other part of the controversial Sanders campaign talking points on Warren was that her supporters — the wealthy, well-educated ones — would already “show up and vote Democratic no matter what … she’s bringing no new bases into the Democratic Party.” At his rallies, Sanders was putting his electability foot forward — supporters waved “Bernie beats Trump” signs while he spoke. In November, The New York Times polled battleground state voters and found that persuadable, white working-class voters had policy views that aligned with some Sanders/Warren proposals, but ��by a margin of 84 percent to 9 percent, they say political correctness has gone too far. They say academics and journalists look down on people like them.” Nonwhite persuadable voters supported systemic change candidates and single-payer health care, but 50 percent approve of Trump, a man known for pushing the boundaries of correctness, political or otherwise.

The anti-political-correctness voters and Trump-approvers are perhaps the demographics where Sanders has the greatest chance to make inroads. While his trademark directness isn’t anti-PC, it’s of a sympatico strain, in a way: “I don’t care what you think, I’m going to say and do what I please.” The Sanders brand is based entirely on that slippery, overused quality that politics so prizes: authenticity. He has believed in the same things for decades and advocated for them in the same polemical style. Even his heavy Brooklyn brogue remains unchanged despite his having left the borough in the ’60s. It speaks to being from a place, not a rootless cosmopolitan class.

Of course, Warren still has the flatness of the plains in her voice, but maybe that’s harder to pick out of the American pantheon of dialects and accents. Plus, the patina of Harvard elitism might stick more to a woman, with voters being more apt to see her as overly liberal in a cultural sense rather than an economic one — ironic, in Warren’s case, given that the cornerstone of her candidacy is radical economic reform. Her tightly constructed, loosely delivered stump speech in Brooklyn — Warren likes to pump her fists while she talks and bend down as if she might jump across a stage — was adept at connecting her famous plans together as a bid for “big, structural change.” Whatever issue brought people to the rally, Warren said, “I guarantee it’s been touched by money.” It was a solutions-oriented 45-minute verbal march; though, of course, both Warren and Sanders know that unless Democrats win the Senate in 2020 (unlikely) and hold onto the House, much of their potential agenda as president would be stymied from the get-go.

But each know that rhetoric wins the day. While they share so many policy goals, it’s obvious their appeal is somewhat divergent. There is certainly a gap between the demographics of Sanders and Warren supporters. According to FiveThirtyEight/Ipsos polling, conducted using Ipsos’s KnowledgePanel,1 about 34 percent of people considering voting for Warren’s have household incomes of over $125,000, compared to around 22 percent of potential Sanders supporters. And Warren’s potential backers are particularly skewed toward college-educated Democrats, while people considering Sanders and Biden are more evenly distributed across education levels.

Sanders is not wrong in pointing out that Warren’s populism — and make no mistake, it is that; she does her fair share of billionaire-bashing — has resonated with a different audience than his. In part, it’s because her packaging of populism is meant to extend an ideological hand to the establishment Democratic voters who cottoned to Clinton in 2016 but regretted, perhaps, their inability to see that the country was ravenous for system-busting talk. She scratches the itch of big ’ole change but understands that the Democratic Party is filled with people who are still comfortable within the system, even if they have intellectual critiques of it.

Sanders’s selling of populism is conscious of its place in the sweep of progressive history. In Iowa, he talked about how not so long ago, public education was seen as a radical idea and cited the aphorism, “It always seems impossible until it’s done,” to explain the mental block the country could overcome to accept Medicare for All.

On Saturday evening, Sanders held a rally in Davenport that opened with performances by a collegiate singer-songwriter — “This one is about my babysitter and how as you get older your relationships change” — and Rep. Rashida Tlaib of Michigan. Tlaib’s voice rose in emotional peaks and cracks as she spoke of her childhood in Detroit, which in her memory is perfumed with the rotten-egg smell of hydrogen sulfide. She bemoaned the building of “bougie” condos in her city. “We need somebody that’s courageous, that won’t sell us out,” she said. “I’m exhausted about the broken promises, these polished speeches — I don’t care if you said the same thing.” With Sanders, she said, “you see this person and he’s real.” It was as succinct an endorsement as a 2020 Democratic candidate could ask for; though, as we all well know by now, what’s “real” is ambiguous and mutable and very much according to one’s taste.

But of course, the crowd cheered; there was no higher praise.

Laura Bronner contributed analysis.

Make sure to check out FiveThirtyEight’s Democratic primary forecast in full; you can also see all the 2020 primary polls we’ve collected, including national polls, Iowa polls, New Hampshire polls, Nevada polls and South Carolina polls.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Allie frowned slightly, watching the events of the Knockouts Title match unfold on the monitor backstage while she nervously manipulated her fingers and wrung at her hands. She'd been pulling for Rosemary to get the win. The Demon Assassin was her best friend, after all, and Laurel Van Ness had spent nearly an entire year making her life absolute misery. It wasn't in Allie's nature to wish ill of anyone, but as the number one contender? She could say she'd sleep much easier at night if she or "her demon friend" were the one to lead the Knockouts locker room now that Gail Kim was gone.

But it didn't happen that way. Allie was crushed, practically deflated when it was the broken bride who had her hand raised highly into the air, announcing victory over Rosemary and the title match now set: Allie versus the new champion, Laurel Van Ness. Champion... how? How was that fair? How could Laurel treat people the way she had, and be rewarded with someone as prestigious and meaningful as a championship? Disappointment flooded her gaze as she pushed away from the small crowd of backstage workers who had surrounded the monitor as well, politely trying to excuse herself. She wanted to check on Rosemary. She had to get some kind of validation that this was real life... that her story with Laurel was going to get yet another chapter written...

As she frantically made her way down the hall, another shocker had come her way: her beau, Jimmy Havoc, standing there in a black dress shirt and tie, and a pair of black slacks that had been tailored to fit on his skinny legs in a snug fashion. The shellshock wore off for a moment, a small, overwhelmed smile on the blonde's face for just a moment; actually reaching out to touch him. Havoc chuckled once or twice as her fingers dusted him and an excited squeak escaped her. Allie was different from the others he'd spent nights with. She viewed the world in a way that had it been anyone else, he'd have found sickeningly positive and saccharine. With Allie? It came from a place of respect and wonder.

"It's really me, luv." He couldn't resist a smile as her face lit up like a Christmas tree, his arms opening for the embrace he knew she'd give, grunting just slightly when he felt her deceptively strong arms cling to his lanky body. "Easy... it's been ten shows in as many days and a red-eye to get here. Those fucks cut me off after three drinks... they obviously don't know who they're dealing with."

"I just can't believe you're here!" She snuggled into his chest, ignoring his momentary whining.

This was what he liked. Someone genuinely happy to see him. Not someone who wanted something - not someone who wanted him to bleed or fight for them. Someone happy to see him, regardless of the horrible things he did - the horrible things he was proud of doing. Allie practically oozed a delectable innocence and a sense of loyalty he'd not known before. She wanted nothing from him, but him. He pecked the top of her head, only groaning slightly as he stood up to his proper height afterwards from his hectic schedule.

"Can... can you wait right here just a sec? I need to go and check on my demon friend..." Allie said, slowly, hesitantly in fact, pulling herself away from him.

"Already? I just got here and you're lookin' to ditch me?" He guilt-tripped her with his big, baby blues.

"No! No, I just... I hope she's okay, is all..." She frowned, tucking one of her blonde curls behind her ear and lowering her head.

"What's with the look?" He asked, as she shifted from foot-to-foot in an antsy manner. "Answer me, luv. Hey. Would you look at me?"

She frowned, hugging herself under her chest. Nerves kept her grounded. Allie adored Jimmy. He'd ignited an entirely new spark into her life that she wasn't sure she'd ever feel again after Braxton left. Braxton had been the source of all of her problems with Laurel. He was out of the picture now. But, Allie knew "Hot Mess" Van Ness. Even if Braxton had shown his true colors and walked out on Allie, Laurel was not going to be the kind of person to allow bygones to be bygones. Havoc's ghostly pale hand lifted Allie's face by the chin, his large thumb that was painted with chipped black polish on the nail gently pushing into the small cleft in it.

"Now," he commanded her attention in a sultry, thick British accent. "Tell me what's got you fretting."

It wasn't a request. "I... I hoped that it would be Miss Rosemary and I fighting for the Knockouts Championship. I... I don't want to go through this whole thing with Miss Laurel again. It was so difficult the first time..."

"That big, bald cunt isn't even in the picture anymore!" Havoc said, and as he searched her green eyes he knew it could be validated, only making him grin more - he loved being the central focus to her world. "Why would it be a bad thing to beat the shit out of Laurel after all that she put you through when he was?"

"Miss Laurel..." she frowned, anxiety making her tremble, until his hands gripped her shoulders and held her steady. "Miss Laurel doesn't play by the rules. She doesn't play fairly! She's so mean. She's treated me just awful, and... and... I-I know it's cruel, but I don't think she deserves to be the champion. Good is supposed to win... right?"

Perplexed was the best way to describe Allie right now. She hated the way she'd been treated in the past by Laurel, and while things had changed tremendously: Laurel being knocked off of her perch and Allie being a more confident, seasoned competitor, it didn't change what had happened in the past. The wounds were there, and right as they began to heal, they were going to be pulled open at the seams again. Jimmy crouched down a bit to her level, though his aching body hated him for it, it was important for his oceanic-colored gaze to lock onto hers.

"Your biggest mistake, darling, is thinking that the world owes you shit for behaving one way over another."

He gently tufted with one of her blonde curls, before watching the way she pouted. He wasn't one to partake in too many cute, sweet things, but her pout was something he found adorable. Not that he'd ever say it. The grin on his face spoke volumes where his words were mute, however.

"Fortune belongs to those who don't give a fuck about who is standing in their way when they seek it. There's no good and evil. Do you think I was Progress Champion for over six hundred days by being a good person? I obliterated anyone who dared to stand in my way and defy me, and I did it through blood, flames, and war with a motherfucking smile on my face and my middle finger raised to anyone who even dreamed of getting the next spot in line for MY title. I'm not a good person and success didn’t give a shit about it. No one truly is a good person, luv. Not completely."

"Even me?"

"You're pretty close..." He admitted, giving her a once over. "But you could be so much more. And the first thing you're going to learn is that it's so much easier to knock the fuckin' head off of someone who you cannot fucking stand, than someone you respect and admire. And once you learn that anyone who stands in your way of getting the title belt you want is expendable? THAT is when you will capture your prize."

She contemplated his life lesson with a disturbed expression. A million and one thoughts ran through her head and for someone as easily overwhelmed as Allie, that was asking a lot of her to process it all. Her fingers went to her temples, beginning to massage them while she muttered to herself, trying to piece together what he'd told her. She'd gotten just a few steps away, pacing being a part of her process. Turning around in a snapping direction, anxiety painted her pretty features.

"But..." She paused, a glassiness taking over her green eyes. "What if I let you down? I... I don't want to fail. She plays so dirty..."

Jimmy examined her, and his pokerface came into play. Having someone who so genuinely cared about what he thought of them was foreign. He'd always been a pawn. He'd been a weapon. He'd been a bargaining chip. He'd never been admired by someone so completely without them wanting something, but Allie was different. She thought the world of him, and she'd been up and down this Knockouts Championship road before. Jimmy could see the concern making her full lips tremble. Approaching her and closing the distance between them, he tilted her head again in the bend of his finger, pressing his forehead to her own.

"So play dirtier." He answered, as if it were the simplest question he'd ever been asked. "You get your pound of flesh from that bitch... and I promise, luv. You will never let me down as long as you do that."

She nodded her head, not daring to repeat the filth that he said but definitely more than willing and more able than ever to take the fight to the person who'd made her miserable. If it meant she brought home the title as well? It would be that much sweeter to finally lay this bad blood to rest. Allie leapt onto Jimmy, her arms around his neck and his arms instantly flung around her waist to keep her safe and supported in spite of his aching body. Her toes barely dusted the floor. She pecked his lips softly, a blush covering her cheeks the moment it was over, followed by a goofy smile.

#fluffish?#jimmy havoc#allie#goth bunnies#otp#crackship#i love them so much#my manip#it sucks though cause i'm still really sick#ship post#drabble

5 notes

·

View notes

Link