#showing liberty leading the people for the French revolution

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I'm begging video essayists to read and cite actual history. You would not believe how many I've clicked off of for very basic errors. Not bad interpretations or arguments; just very basic factual errors.

#historian consumes media#i just clicked off of one for the tripple whammy of: calling the Pale of Settlement 'modern day Germany'#showing liberty leading the people for the French revolution#and calling Central Europe 'the former Russian empire '

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

African Americans in the American Revolution

On the eve of the American Revolution (1765-1789), the Thirteen Colonies had a population of roughly 2.1 million people. Around 500,000 of these were African Americans, of whom approximately 450,000 were enslaved. Comprising such a large percentage of the population, African Americans naturally played a vital role in the Revolution, on both the Patriot and Loyalist sides.

Black Patriots

On 5 March 1770, a mob of around 300 American Patriots accosted nine British soldiers on King Street in Boston, Massachusetts. Outraged by the British occupation of their city, as well as the recent murder of an 11-year-old boy, the crowd was filled with Bostonians from all walks of life; among them was Crispus Attucks, a mixed-race sailor commonly thought to have been of African and Native American descent. When the British soldiers fired into the crowd, Attucks was struck twice in the chest and was believed to have been the first to die in what became known as the Boston Massacre. He is regarded, therefore, as the first casualty of the American Revolution and has often been celebrated as a martyr for American liberty.

Five years later, in the early morning hours of 19 April 1775, a column of British soldiers was on its way to seize the colonial munitions stored at Concord, Massachusetts, when it was confronted by 77 Patriot militiamen on Lexington Green. Standing in this cluster of militia was Prince Estabrook, one of the few enslaved men to reside in Lexington, who had picked up a musket and joined his white neighbors in defending his home. In the ensuing Battles of Lexington and Concord, Estabrook was wounded in the shoulder but recovered in time to join the Continental Army two months later. He was selected to guard the army headquarters at Cambridge during the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775) and was freed from slavery at the end of the war.

Attucks and Estabrook were just two of the tens of thousands of Black Americans who supported the American Revolution. There was no single motivation for their doing so. Some, of course, were inspired by the rhetoric of white revolutionary leaders, who used words like 'slavery' to describe the condition of the Thirteen Colonies under Parliamentary rule and promised to forge a new society built on liberty and equality. These words obviously appealed to the enslaved population, many of whom were optimistic that, even if slavery was not entirely abolished, they might receive better opportunities in this new nation. Others enlisted in the Continental Army to secure their individual freedoms, as the Second Continental Congress had proclaimed that any enslaved man who fought the British would be granted his freedom at the end of his service. African Americans also enlisted to escape the day-to-day horrors of slavery, to collect the bounties and soldiers' pay offered by recruiters, or simply because they were drawn to the adventure of a soldier's life. Additionally, several Black Americans were forced to enlist by their Patriot masters, who preferred to send their slaves to fight instead of going themselves.

Of course, not all Black Patriots served in the Continental Army or Patriot militias. Some, like James Armistead Lafayette, were spies; posing as a runaway slave, Lafayette was able to infiltrate the British camp of Lord Charles Cornwallis and procure vital information that helped lead to the Patriot victory at the Siege of Yorktown. The French general Marquis de Lafayette was impressed with his service and helped procure his freedom after the war, leading James Lafayette to adopt the marquis' name.

Other Black Patriots showed their support for the movement with their words. Phillis Wheatley was an enslaved young woman who had been brought to Boston from Senegal, where she had been seized. She was purchased by the Wheatley family, who quickly recognized her literary talents and encouraged her to write poetry. By the early 1770s, Phillis Wheatley was already a celebrated poet. She began to write extensively on the virtues of the American Revolution, praising Patriot leaders like George Washington. Despite his status as a slaveholder, Washington was moved by Wheatley's work and invited her to meet him, stating that he would be honored "to see a person so favored by the muses" (Philbrick, 538).

Continue reading...

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEW BSD CHAPTER (120.5) SPOILERS because Fyodor's plans and logic are very interesting to me

So new chapter dropped and I wanted to look at Fyodor's conversation with Fukuzawa and his plan to eradicate ability users plays into hijacking Fukuchi's plan.

So Fyodor comes out swinging and immediately tells Fukuchi's dream of peace through a union of man (that Fukuzawa insists Fyodor stole...) is not feasable.

Notably Fyodor mentions that it is an "Unlearned outlook befitting of your short lives." This confirms that Fyodor's lifespan has been, as suspected, far longer than that of a normal man, likely hundreds of years (earliest confirmed sighting in the mid-1400s). It also confirms that because of his age Fyodor feels he is more learned and knowledgeable of a solution to humanity's divisiveness because of his longer lifespan. Mentioning the 'modern state' framework only being from around the 1700s also confirms his longer life span.

The key thing he mentions about the 'modern state' is that it's simply a 'toddling promise', confirming that he does not believe that the framework of a unified state is enough to keep the peace. He thinks that the framework of states will very heavily change, perhaps by government affairs moving to the private sector or extraterrestrial communities. Either way, new divisions will be created and cause conflict. And according to Fyodor there will always be those who will try and create these divisions - the new 'us' vs 'them' dynamics.

Fukuzawa meanwhile believes that humanity will be able to unite through 'benevolence' (kindness/well meaning) and 'virtue' (high moral standards). He holds the idea that if humans listen to their own morals they will be able to fully unite, by Fyodor says that this is the 'fatal flaw' of both Fukuzawa and Fukuchi. Fukuzawa's wholehearted belief in the goodness of others links well to his running of the ADA - helping his subordinates control their abilities in order to do good for the community, even hiring ex-mafia members. It is also Fukuzawa's belief in the goodness of others that has a huge impact of his relationship with Fukuchi. It is Fukuchi's belief in the goodness of others that fuels his plan, and his belief in the goodness of Fukuzawa in making him the theoretical leader of mankind.

However, Fyodor believes that despite their idealised views of man, mankind cannot bear this consistent high moral standard. How people cannot necessarily always follow their moral compass due to societal pressure - choosing the 'status quo' and whatever is easier for them over morals and kindness. He thinks that common people will not stand for a worldwide dictatorship, no matter how kind their leader, and would lead a revolution against the 'nation of man' for the sake of independence, starting the divisions and cycle of violence again.

The painting referenced is 'Liberty Leading the People' by Eugène Delacroix (thanks to @kyouka-supremacy 's post for pointing me in the right direction), a French Romantic artist. It is depicting the July Revolution of 1830, where a group of revolutionaries helped remove a constitutional monarchy (a monarchy with other advisors and a constitution (laws/rules) to follow) and replace it with a new system. (apologies for the vague explanations I'm not knowledgeable on this topic, I highly recommend you look into it yourselves if you're interested in further details). These events mirror Fyodor's theories of a group of people rising up to take down the system of the worldwide union of man and replace it with new divisions, causing the cycle of violence to re-emerge.

Fyodor actually turns Fukuzawa own belief system on its head with the example of Fukuchi's promise to only k!ll 500 people (and no more) to implement his plan of world peace. Since Fukuzawa isn't confidently able to verify this, it shows that people can be able to take advantage of those who express only kindness to their fellow man through lies or falsely forged trusts. This shows that the reliance on benevolence and virtue leaves the system of a union of mankind vulnerable to exploitation, meaning it is not foolproof enough to stand in the realm of feasibility.

Fyodor then goes to talk about how he is following Fukuchi's goals of world peace as his 'successor' or 'disciple'. I want to make special note of the use of 'disciple' due to its religious connotations, and Fyodor is also consistently paired with religious imagery. The religious connotations are strengthen by the fact that Fukuchi's body is currently the vessel for the Divine Being Amenogozen, a higher-dimensional being that appears god-like in its immense strength and powers.

Fyodor's idea of creating peace is by starting a world war between non-superpowered humans and ability users. He has used Fukuchi's vampire outbreak plan (and usage of the One Order) to show the humans the danger of ability users (and the ways to utilise One Order as well), creating/strengthening an 'us' vs 'them' mentality between the two. [Note last month's chapter's colour spread of Atsushi and Akutagawa - the quote it uses is "Fear of the enemy shall always drive us to take up arms." The people's fear of ability users shall cause them to turn of war.] This is ultimately going to cause a conflict between the two groups, using the 'hideousness of man' to bring peace to humanity, as he thinks humanity will be united after it rids the world of ability users. This idea could be founded in what he has seen in his lifespan, or founded from his own hatred of ability users. Either way the plan entails his own ideology against ability users emerging from the collapse of civilisation (saw a tweet talking about this being many characters' motivations like Fitzgerald and Agatha Christie as well).

Fyodor intends to use the more 'evil' elements of humanity to create world peace - the 'hideousness of man', which can entail their thirst for violence, the creation of conflict. Fukuchi (and by some extent Fukuzawa) intended that the inherent goodness of man would prevail - 'benevolence' and 'virtue', everyone caring for and looking out for their fellow man. They have polar opposite philosophies on the inherent morality of mankind which drive their solutions to the political matters at hand in pursuit of world peace.

Fyodor mentions this world peace either being around a thousand years long or on the next page "eternal peace". It may be purposeful to do so, as it could bring questioning to how founded/unfounded his philosophy/plan is.

"Such opposition, coupled with the threads of abhorrence, shall give rise to a united humanity." - The divide between everyday humans and ability users is strengthened through digust/repulsiveness of humans towards ability users will unite humanity against a common enemy, therefore creating peace once that enemy has been eliminated.

[I always find it really fun to focus on these types of conversations despite my lack of knowledge on philosophy and stuff like that but they are genuinely interesting. Once I find a way to read the new Yuumori chapter I could do something similar if anything really interesting comes up... i've also got an arcane s2 post in the drafts that I may or may not post, it's a long one about episodes 7-9 but idk if my points are all that good..]

#bsd#bungou stray dogs#bungo stray dogs#bsd spoilers#bsd 120.5 spoilers#bsd manga spoilers#bsd manga#bsd fyodor#bungou stray dogs fyodor#fyodor dostoyevsky bsd#bungo stray dogs fukuzawa#bsd fukuzawa#bsd fukuchi

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rapscallion

A/N - Day one of August's Tickletober! Anticipation is today's prompt, so here is a Deadpool and Wolverine fic! Please enjoy.

Word Count: 975

“My dearest fanfic readers, you have absolutely no idea how horny I am right now,” Wade let out an exaggerated moan as he stared deeply into Logan’s fiery eyes. Fiery was an understatement, the literal pits of hell could be seen if you looked into his pupils long enough.

“I have no fucking clue on why you keep talking to ‘the readers,’ but it's starting to piss me off,” Logan snarled, his to the running across his top row of teeth.

“Oh, you are such a tease, Peanut! Speaking of bits, mine has an itch that needs to be juiced.”

“You are one of the most revolting people I have ever met,” Logan's center claws slipped out from between his joints, lowering just enough for Wade’s wrists to feel pinpricks of anticipation. “What I wouldn't do to tear your bottom jaw off your disgusting face so you could never speak again.”

“Admit it, sweetheart,” Wade cooed, ready to recoil the second his statement was finished, “You'd miss the blowies way too much.”

As Wade turned his head away, burying his face in his shoulder, he waited for his wrists to be sliced like a fish filet. However, this didn't happen. Uncomfortably shifting underneath Logan's weight, wrists still trapped above his head.

It was a super-secret mission that they were on, Wade had told Logan. Knowing Wade, Logan presumed that this mission was to spy on the Avengers or some shit, especially as Wade kept humming this one “heroic” song that he had told Logan was “really fucking cool in 2012.” While there were no sightings of Thor or Hawkeye, the two, in traditional superhero fashion, did manage to stop some sort of evil entity that wanted to take over Philadelphia. Aside from the Liberty Bell now having a new crack, Wade's fault naturally, the day was saved and our heroes needed a place to crash. Despite saving the day and all, they were a bit short on pocket money, so a grungy Motel 6 was their destination. Logan stayed in to watch TV, which based on the size and shape of it, was miraculously showing films in color, while Wade went hunting for the perfect Philly Cheesesteak. This temporary separation worked exceptionally well until Wade returned and spoiled the end of the film Logan was watching.

“It's not my fault your universe was still waiting for Incredibles 2! I thought you'd seen it!”

“Why would I be watching it if I hadn't seen it yet?”

“Maybe it's your favorite movie, I don't know. You seem like the kinda guy that would prefer more manly movies like Top Gun, Bridesmaids, or Velocipastor, but who am I to judge?”

Naturally, Wade continued to push his luck and Logan's buttons, which lead them to our current situation. Logan pinning Wade on the bed, his wrists trapped between two of Logan's claws and Logan's entire weight on top of him.

Squirming as if he was wearing “grandma's surprise Christmas sweater,” Wade now looked back up at Logan, muscles tensing in the slightest.

“So, are you gonna do the stabby thing? Spaw my blood everywhere like a Quintin Tarantino film?”

“I'm not sure yet.”

“Ah, I see,” Wade clicked his tongue. “Well, we don't have to do the whole slicing me up like a sandwich thing. While this joint certainly isn't a Four Seasons, we don't need to Rudy Giuliani it all and spread mysterious liquids everywhere. Wait, who is the president in your universe?”

“Matthew Perry?”

“Ah, shit. Those kids from Smosh are psychic!” Logan let out a grumble, reminding Wade of his current predicament. “Shit, um, what should you do to me? Bondage? Sing songs of the French Revolution? Whisper sweet nothings in my ear? Hold me closer, tiny da-ack!” Wade was cut off by his own vocal tic. Logan released one of Wade's arms and when Logan repositioned his own, he accidentally grazed Wade's side. “What the shit, man? You didn't tell me I was gonna need to point out where the scary man touched me on a doll to my therapist this week!”

“What the fuck was that noise, bub?” Logan mused; one eyebrow cocked upward. Making a humming sound, Logan moved his hand back to Wade's side and squeezed. Once again, Wade made a strangled yelp.

“Okay, maybe we can get back to the stabbing and bleeding part again,” a wave of nervousness washed over Wade's words.

“Of course, why wouldn't you be ticklish too?” Logan said mostly to himself, and he continued to poke and prod Wade's side, slowly walking his fingers up to the lower rib cage.

“Marvel Jesus does not condone this level of violence!” The last two words were an octave higher as Logan decided that was the moment to stop holding back and quickly skitter his fingernails across the sides of his ribs. “Shit! Peanut!”

Logan continued his assault silently, trying not to smile as Wade writhed beneath him. Shouting out obscenities and references that went over Logan's head, Wade's laugh became increasingly hysterical and frantic as Logan's fingers journeyed upward.

“This is communist propaganda! A war crime! Don't you understand the Geneva Convention? You heathen. You rapscallion. A scoundrel. A hippocampus! A flou-!” Wade's words vanished from his tongue, replaced with loud cackles and hiccups.

“Damn shame this is the only way to shut you the fuck up, bub,” Logan broke his silence, his amusement of the situation now apparent by the upturned curl of his lips. He was thankful that Wade's eyes were as shut as they could be, Wade seeing this little bit of joy could be a catalyst to something bigger than Logan wanted to deal with any time soon.

What Logan didn't know was that Wade was already plotting his revenge. Something so devious, cruel, and sexy, that the world was not prepared for it.

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

🤚 ^^

🤚Book recs

This is hard because I had stopped reading for many years and I've been trying to get on track in the last year. Overall, I have read many books, but the only ones I feel like recommending are all historical essays about the French Revolution and despite some being in Italian and French I will mention them anyway, given that some of my followers are also from Italy and France ^^

1. P. McPhee's Liberty or Death.

This book is very dear to me, because it was my first ever frev book! I recommend it because it's heavily sourced, explains very clearly the causes and consequences of the Revolution and the history is told, through the quoting of primary sources and accounts, from the people's pov, something quite unique in frev historiography. Unfortunately, this last point can also be a downside, especially for those who know absolutely nothing of the French Revolution: some of the key events sometimes get discussed in a few lines to give much more space to how they were perceived by the population. Not only this may lead to an oversimplification of said events, but also to confusion regarding their chronological order. At the end of the book there's a timeline though, which I suggest to consult in case you feel lost while reading.

I would say it's accessible to everyone interested in the topic and who has an adequate level of English to understand it. Of course, the read will be much more fluid if one already knows a bit about the French Revolution.

2. M. Vovelle, La Révolution Française 1789-1799.

This book exists only in French and Italian sadly. I say sadly, because despite not having read it in full, it's an excellent and concise summary of the French Revolution. It's perfect for literally everyone: students who have to prepare an exam, historians who have to quickly revise it and amateurs who want to be introduced to the French Revolution through something that's not too big or overwhelming. What I like about it, it's the fact it's short, but it manages to perfectly highlight the main events and key figures, showing how important the Revolution was and its consequences in our present era.

I believe an English equivalent would be Soboul's The French Revolution 1789-1799.

3. M. Reinhard, Le Grand Carnot vol. I & II.

Yes, a specific biography, I mean it seriously. Lazare Carnot's life is truly fascinating, but in case you are not interested in him at all, I would still recommend it since it's a nice example of how it's perfectly possible to make an amazing, detailed, well sourced, as impartial as possible work on a beloved historical figure. Because Reinhard likes Carnot, but he cleverly manages to conceal it, by exposing his merits, epic fails and controversial actions; even when he enters the realm of speculation, he does it relying on sources, primary most of the time. Moreover, he is rather knowledgeable about the historical period Carnot lived through, thus the latter's words and decisions get explained in their relative historical context, making it easier to decipher Carnot's motives.

Lastly, it's godly and elegantly written. I genuinely can't wait to fully devote my reading sessions to it, because until now I have only read separate chapters and excerpts.

4. Anything about Nikola Tesla.

Seriously guys, I can't even find the right words to explain how important that genius was, and how unfairly poorly he was treated. Each of us would have something to learn from such a brilliant, devoted and altruistic mind.

#ask game#ask#someone should give me the Marcel Reinhard simp card#also the Vovelle one after what I have learnt about him :3#aes.txt#frev#book recs

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

A.1.5 Where does anarchism come from?

Where does anarchism come from? We can do no better than quote The Organisational Platform of the Libertarian Communists produced by participants of the Makhnovist movement in the Russian Revolution (see Section A.5.4). They point out that:

“The class struggle created by the enslavement of workers and their aspirations to liberty gave birth, in the oppression, to the idea of anarchism: the idea of the total negation of a social system based on the principles of classes and the State, and its replacement by a free non-statist society of workers under self-management. “So anarchism does not derive from the abstract reflections of an intellectual or a philosopher, but from the direct struggle of workers against capitalism, from the needs and necessities of the workers, from their aspirations to liberty and equality, aspirations which become particularly alive in the best heroic period of the life and struggle of the working masses. “The outstanding anarchist thinkers, Bakunin, Kropotkin and others, did not invent the idea of anarchism, but, having discovered it in the masses, simply helped by the strength of their thought and knowledge to specify and spread it.” [pp. 15–16]

Like the anarchist movement in general, the Makhnovists were a mass movement of working class people resisting the forces of authority, both Red (Communist) and White (Tsarist/Capitalist) in the Ukraine from 1917 to 1921. As Peter Marshall notes “anarchism … has traditionally found its chief supporters amongst workers and peasants.” [Demanding the Impossible, p. 652]

Anarchism was created in, and by, the struggle of the oppressed for freedom. For Kropotkin, for example, “Anarchism … originated in everyday struggles” and “the Anarchist movement was renewed each time it received an impression from some great practical lesson: it derived its origin from the teachings of life itself.” [Evolution and Environment, p. 58 and p. 57] For Proudhon, “the proof” of his mutualist ideas lay in the “current practice, revolutionary practice” of “those labour associations … which have spontaneously … been formed in Paris and Lyon … [show that the] organisation of credit and organisation of labour amount to one and the same.” [No Gods, No Masters, vol. 1, pp. 59–60] Indeed, as one historian argues, there was “close similarity between the associational ideal of Proudhon … and the program of the Lyon Mutualists” and that there was “a remarkable convergence [between the ideas], and it is likely that Proudhon was able to articulate his positive program more coherently because of the example of the silk workers of Lyon. The socialist ideal that he championed was already being realised, to a certain extent, by such workers.” [K. Steven Vincent, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and the Rise of French Republican Socialism, p. 164]

Thus anarchism comes from the fight for liberty and our desires to lead a fully human life, one in which we have time to live, to love and to play. It was not created by a few people divorced from life, in ivory towers looking down upon society and making judgements upon it based on their notions of what is right and wrong. Rather, it was a product of working class struggle and resistance to authority, oppression and exploitation. As Albert Meltzer put it:

“There were never theoreticians of Anarchism as such, though it produced a number of theoreticians who discussed aspects of its philosophy. Anarchism has remained a creed that has been worked out in action rather than as the putting into practice of an intellectual idea. Very often, a bourgeois writer comes along and writes down what has already been worked out in practice by workers and peasants; he [or she] is attributed by bourgeois historians as being a leader, and by successive bourgeois writers (citing the bourgeois historians) as being one more case that proves the working class relies on bourgeois leadership.” [Anarchism: Arguments for and against, p. 18]

In Kropotkin’s eyes, “Anarchism had its origins in the same creative, constructive activity of the masses which has worked out in times past all the social institutions of mankind — and in the revolts … against the representatives of force, external to these social institutions, who had laid their hands on these institutions and used them for their own advantage.” More recently, “Anarchy was brought forth by the same critical and revolutionary protest which gave birth to Socialism in general.” Anarchism, unlike other forms of socialism, “lifted its sacrilegious arm, not only against Capitalism, but also against these pillars of Capitalism: Law, Authority, and the State.” All anarchist writers did was to “work out a general expression of [anarchism’s] principles, and the theoretical and scientific basis of its teachings” derived from the experiences of working class people in struggle as well as analysing the evolutionary tendencies of society in general. [Op. Cit., p. 19 and p. 57]

However, anarchistic tendencies and organisations in society have existed long before Proudhon put pen to paper in 1840 and declared himself an anarchist. While anarchism, as a specific political theory, was born with the rise of capitalism (Anarchism “emerged at the end of the eighteenth century …[and] took up the dual challenge of overthrowing both Capital and the State.” [Peter Marshall, Op. Cit., p. 4]) anarchist writers have analysed history for libertarian tendencies. Kropotkin argued, for example, that “from all times there have been Anarchists and Statists.” [Op. Cit., p. 16] In Mutual Aid (and elsewhere) Kropotkin analysed the libertarian aspects of previous societies and noted those that successfully implemented (to some degree) anarchist organisation or aspects of anarchism. He recognised this tendency of actual examples of anarchistic ideas to predate the creation of the “official” anarchist movement and argued that:

“From the remotest, stone-age antiquity, men [and women] have realised the evils that resulted from letting some of them acquire personal authority… Consequently they developed in the primitive clan, the village community, the medieval guild … and finally in the free medieval city, such institutions as enabled them to resist the encroachments upon their life and fortunes both of those strangers who conquered them, and those clansmen of their own who endeavoured to establish their personal authority.” [Anarchism, pp. 158–9]

Kropotkin placed the struggle of working class people (from which modern anarchism sprung) on par with these older forms of popular organisation. He argued that “the labour combinations… were an outcome of the same popular resistance to the growing power of the few — the capitalists in this case” as were the clan, the village community and so on, as were “the strikingly independent, freely federated activity of the ‘Sections’ of Paris and all great cities and many small ‘Communes’ during the French Revolution” in 1793. [Op. Cit., p. 159]

Thus, while anarchism as a political theory is an expression of working class struggle and self-activity against capitalism and the modern state, the ideas of anarchism have continually expressed themselves in action throughout human existence. Many indigenous peoples in North America and elsewhere, for example, practised anarchism for thousands of years before anarchism as a specific political theory existed. Similarly, anarchistic tendencies and organisations have existed in every major revolution — the New England Town Meetings during the American Revolution, the Parisian ‘Sections’ during the French Revolution, the workers’ councils and factory committees during the Russian Revolution to name just a few examples (see Murray Bookchin’s The Third Revolution for details). This is to be expected if anarchism is, as we argue, a product of resistance to authority then any society with authorities will provoke resistance to them and generate anarchistic tendencies (and, of course, any societies without authorities cannot help but being anarchistic).

In other words, anarchism is an expression of the struggle against oppression and exploitation, a generalisation of working people’s experiences and analyses of what is wrong with the current system and an expression of our hopes and dreams for a better future. This struggle existed before it was called anarchism, but the historic anarchist movement (i.e. groups of people calling their ideas anarchism and aiming for an anarchist society) is essentially a product of working class struggle against capitalism and the state, against oppression and exploitation, and for a free society of free and equal individuals.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Political Themes in Classic Literature

Alright, let’s dive into political themes in classic literature. For anyone who thinks old books are just dust-covered stacks of antiquated language, you are dead wrong. Let’s just take a step back and remember that some of the most impactful political ideas in history didn’t come from debates in dull government buildings—they came from books. Yes, literature! Think of classic novels as political soap operas, only with more existential crises and a lot fewer commercial breaks.

The political puppet show:

So, what do politics and classic literature have in common? Quite a lot, actually. Literature doesn’t just entertain; it holds up a mirror to society and shows us how messed up (or wonderful) things are. Whether it’s criticizing an oppressive regime, showing the chaos of revolution, or examining the moral dilemmas faced by those in power, classic literature doesn’t ( and literature in general should never) shy away from political themes.

One of the most intriguing things about classic literature is how authors use characters and plots to critique the political systems of their time. In George Orwell’s Animal Farm, we see the rise of a totalitarian regime, but with... animals. Yes, pigs. Orwell is talking about the Russian Revolution and the dangers of unchecked power. The pigs, who start out with lofty ideals of equality, end up becoming as corrupt and oppressive as the humans they replaced. The message? Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power tends to corrupt absolutely (a fancy way of saying that rulers, no matter how noble they start, can easily lose their way).

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx. Yes, it's not a novel, but it’s a key text in understanding political revolutions. Marx and Engels argued that class struggle would eventually lead to a proletarian revolution, where the working class would overthrow the bourgeoisie. While not a story in the traditional sense, its influence on revolutions around the world (hello, Russia, China, Cuba!) makes it an essential part of political literature.

When Chaos Reigns: The Politics of Revolutions:

Nothing gets the political waters flowing like a good old-fashioned revolution. Literature has long been a tool for expressing the chaos, confusion, and sometimes the sheer absurdity of these moments in history. Take 1984 by Orwell—again... This time, we’re in a world where Big Brother is always watching, and privacy is a thing of the past. Orwell’s vision of a totalitarian regime controlled by surveillance, propaganda, and fear was a warning about the dangers of political overreach. Fast-forward to today, and you’ll find that his bleak vision feels eerily close to the reality of modern surveillance states.

In The Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, we see the French Revolution through the eyes of characters who are caught up in the violence and turmoil. Dickens shows us how the revolution, meant to bring about liberty and equality, quickly devolves into chaos and bloodshed. People who were once oppressed now become the oppressors. It's the classic "be careful what you wish for" scenario—and it’s not just in the French Revolution. Many revolutions, whether political, social, or even technological, have shown us how easily things can spiral out of control when the old systems are overturned without a clear plan for what comes next.

Russian literature is a goldmine for political themes that dig deep into societal struggles, personal turmoil, and the larger forces that shape history.

Take War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy, for example. Set against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars, this epic novel isn’t just about battlefield drama—it’s about the political and social upheaval (violent or sudden change) that these wars bring. Through his huge cast of characters, Tolstoy critiques the Russian aristocracy, showing us how disconnected the wealthy and powerful are from the suffering of ordinary people. As young men are shipped off to fight wars they don’t fully understand, Tolstoy paints a picture of a society that is as chaotic as the battles it’s embroiled in. The violence and chaos of war seem almost tame compared to the political and social systems that allow such events to unfold. It’s a sobering reminder of the divide between the political power held by a few and the lives of the many.

Then there’s Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, which takes us to a different kind of chaos—the moral and philosophical kind. In this novel, Dostoevsky explores the dangers of ideology, faith, and authority, which in many ways are just as politically charged as any revolution. As his characters wrestle with questions of belief, power, and their own place in the world, the novel digs into the political tensions within Russian society and religion. The political impact of The Brothers Karamazov was so strong that the Russian government kept a watchful eye on Dostoevsky himself, fearing that his questioning of church and state could stir up trouble among the masses. This book isn't just a deep philosophical meditation; it's a warning about the consequences of unchecked authority and the destructive power of ideology.

In One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez critiques the political systems of Latin America, focusing on the cyclical nature of revolution and power. The corrupt political systems in the town of Macondo reflect the repeated failures of revolution, where every new regime promises change but ultimately falls into the same patterns of oppression and violence. The novel shows how revolutionary ideals can quickly turn into systems of corruption, highlighting the disillusionment many felt with political leaders who fail to deliver true change.

Morality and Ethics in Politics: the good, the bad, and the politician.

In the world of politics, morality is like that pesky little voice in your head saying, "Hey, maybe don't do that thing." Ethics are the rules you kind of wish everyone followed, but let’s face it, not everyone does. Now, throw these into the mix of political decisions and you get moral dilemmas, the ultimate "What would you do?" situations. And when you throw characters into this, suddenly, you’ve got a drama that’s better than any reality TV show.

In Les Misérables, Victor Hugo presents the story of Jean Valjean, who, after stealing bread to feed his family, faces a lifetime of punishment under a rigid legal system (basically for breathing <3). His internal conflict highlights the tension between legal justice and moral justice. As Valjean navigates his path toward redemption, Hugo critiques the harshness of the justice system and the ethical responsibility of individuals within a corrupt society.

Similarly, 1984 by George Orwell delves into the ethical struggles of Winston Smith as he navigates a totalitarian regime where the very concept of truth is manipulated. Winston's journey, filled with the desire for freedom and individuality, demonstrates the cost of rebellion in a society that controls every aspect of its citizens' lives. His moral battle—whether to remain loyal to his beliefs or submit to the Party's lies—serves as a haunting commentary on the oppressive nature of unchecked political power and the moral corruption it brings. In such works, the characters’ ethical decisions become not just personal, but political, reflecting broader questions about justice, freedom, and the consequences of betrayal.(There are so many books I could talk about rn I-)

Impact on Political Movements: how did these books affect real life revolutions:

In the case of Les Misérables, the themes of social injustice and the failure of the French government resonated deeply with the working-class revolutionaries of the 19th century. The novel’s portrayal of the barricades and uprisings, even though ultimately unsuccessful, inspired a generation of revolutionaries who sought to topple the entrenched social and political systems. Hugo’s work became an emblem of resistance, one that resonated not only in France but across Europe during times of political unrest.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, similarly, had a profound effect on the political landscape of the United States. Its depiction of the inhumanity of slavery galvanized the abolitionist movement, forcing many Americans to confront the moral implications of the system. Stowe's vivid portrayal of the brutal realities of slavery made it impossible for the North to remain indifferent to the plight of the enslaved, playing a crucial role in building support for the abolitionist cause. The book became a symbol of resistance and solidarity, one that ultimately contributed to the outbreak of the Civil War.

Universal relevance: Politics doesn't have an expiration date.

The political themes in classic literature touch on things like justice, freedom, and equality. These aren’t just problems from the past; they’re timeless issues...

In The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck explores the plight of migrant workers during the Great Depression, but its message about the exploitation of the poor is just as applicable to contemporary struggles against economic inequality (The exploitation of the poor doesn’t have an expiration date either, and it’s still something we’re fighting against in the modern world.).

Similarly, the themes in Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, though rooted in the social hierarchies of early 19th-century England, speak to universal themes of class, marriage, and individual agency. Austen critiques the limitations placed on women by society, calling attention to the ways in which economic power and social status restrict personal freedom. These concerns remain relevant today, as women continue to fight for gender equality and the right to autonomy in many parts of the world.

Why Does This Matter?

Okay, so we’ve explored how literature critiques political systems, critiques leaders, and explores the chaos of revolution. But why does all this matter to us today? Here’s the kicker: these books and their political themes still resonate. They’re not just dusty old novels you read in high school and promptly forget. They’ve got real-world implications.

Take a look around. What’s happening in the world today? Struggling to find decent healthcare? Check. Big corporations running the show? Check. Politicians who say one thing and do another? Double-check. We’re still grappling with the same political issues that have been explored in classic literature for centuries. Maybe we haven't had a Les Misérables-type revolution (yet), but we’ve certainly seen protests, uprisings, and calls for social justice echoing across the globe, just like in the pages of those old books.

And it gets worse...

Don’t think that the digital age has made these themes less important. If anything, social media and the internet have amplified the political issues that these classic books explored. Think about how politicians now use platforms like Twitter or Instagram to manipulate public opinion or deflect criticism. It’s almost like reading 1984 all over again, with the new-age "doublethink" of social media where truth is constantly bent and twisted. In a world of 24/7 news cycles, “alternative facts,” and fake news, it’s hard not to see the parallels with Orwell’s Big Brother.

Classic literature is not just for those who enjoy long-winded prose and tragic endings. It’s a treasure trove of political insight. From critiques of power to depictions of revolutionary chaos, these stories show us the triumphs and failures of human societies. They remind us that the fight for justice, fairness, and equality is far from over. So next time you crack open a classic novel, remember: it’s more than just a story—it’s a blueprint for understanding the political world we live in today.

The books mentioned and more if you're interested:

.Les Misérables by Victor Hugo

. 1984 by George Orwell

. Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe

. The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

. A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens

. The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

. Animal Farm by George Orwell

. The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

. The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli

These are some links to more articles about this subject or close to it if you wanna read more about what we already see in real life lol:

#writers#politics#politique#writing prompts#writers on tumblr#writing#my writing#drink it write it#rambles#writer#les mis#liturature#books and libraries#literature#themes#seriously#article#tumblr girls#writer's block#writeblr#writerscommunity#writer prompts#trump#fuck trump#america#usa politics#world news

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

bricktober day 12- ghosts

@lesmis-prompts

It's not going to work. no one will show up. Why am I trying so hard to make a difference for a few people?

I feel stupid, now. Oh sure, I know it's a good thing, what they're doing (what we're doing) but we read about the French Revolutions today and that's just so much more-

What I mean is that they were fighting for everything. For everyone. For freedom, for liberty, for their lives. They won. They made a difference. What can I do, me and my friends?

It's not a competition I hear and spin around.

There's- fading in and out of view, a few inches above the ground, is a ghost. Messy black hair and green coat, paler than he would have been in life. It's a shock. Sure, I know ghosts are real, but it's one thing knowing and another seeing.

"What?" I probably sounds stupid but I can't bother to care.

Revolutions, fighting battles that shouldn't have to be fought, they're not a competition.

I say nothing so the ghost continues.

I know some of us thought similar. Back then. We were thinking that really, what can we do? Dictatorships and monarchies? People were dying daily in the galley for crimes they didn't commit. Other places were torn by war. Thieves were sentenced to twenty years just for running away. Our government were bad but there were other things far worse that were taken for normal.

But you can't fight every cause at once. Just because there are worse things doesn't make your thing irrelevant. Injustice can be big or small. The important thing is that you are fighting it. I thought, when I was alive, that we wouldn't change anything. And if you looked at us, just us, we didn't. But after we fought and lost, others took up the banner. When they fought and lost, others took it up. After them others. After them more. Until one day some people fought and won.

It might not feel like anything now but there are people who will see what you are doing and be inspired. Or be happy. Or maybe their life will have changed because of it.

Let me tell you something. There will be fights after you. After this cause has been won there will be others. And they will look back and think that they aren't doing anything, that bigger causes have been fought. And then they will change more than they imagined.

It happens every fight. The people might doubt, the leader might doubt, but as long as they fight things will happen. Things will change. Je te promets.

"Who are you?" I ask.

Me? Nobody. Just Aire. R. That's me.

"You-The french revolution?"

It was never one revolution. A thousand different ones, sequencial and simultaneous. We called ours the June Rebellion, then. But yes, in a way.

"But then-really?"

Really.

"Wait!" I call, but he's already gone.

I sit on my bed, thinking about what he said.

Years later and I'm leading a rally through London. Waving rainbow flags, there must be thousands of us. Out of the corner of my eye I see a flash of green. I turn.

R is there, smiling sadly. When I blink he's gone.

I looked through as many books as I could, after that day. I know his name now. His revolution, his golden leader. I still don't know why he found me, nor why he gave me advice. I am glad he did, or I might not be here today.

It's 2013. I haven't seen R since that day, but so much has changed. Yesterday the Same-Sex Couples Act was passed. I'm already thinking on how we can celebrate it, make sure everyone knows. I see what R meant now. I would never have thought our battle would have become this big, but it did and we've just won it. There's still so much more to do though...

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every Rose Has Its Thorns: Vilifying female ambition in The Rose of Versailles

The Rose of Versailles is a shojo classic with a reputation as an LGBTQ+ work, mostly thanks to Oscar’s character and their relationships with women like Marie Antoinette and Rosalie. While that’s one of the show’s main draws and much can be said about it, this time I’m looking into a less-discussed side of the show: its portrayal of female anger, ambition and power, and how they exist within considerable limitations.

The show��which takes place in France in the years leading to the French Revolution—blends fantasy with history, keeping major historical events and figures while taking liberties in the way they fit in the story. Historical accuracy doesn’t matter much beyond following key events that culminate in the revolution and eventual execution of Marie Antoinette. The layers of fantasy give the story flexibility not only in the relationships it creates and the subplots it follows, but in the way the characters are portrayed.

As a main character, Oscar is an all-encompassing figure who struggles with gender roles and love, duty and upbringing, loyalty to the Queen and a growing empathy to the people. But with Marie Antoinette and the women who act as villains, we see a more traditional exploration of female power, ambition, and anger. Meanwhile, Rosalie is a sympathetic character who offers a combination of kindness with anger that, notably, lacks the ambition associated with the female villains.

Read it at Anime Feminist!

#rose of versailles#berubara#versailles no bara#lady oscar#rov#marie antoinette#madame du barry#articles

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

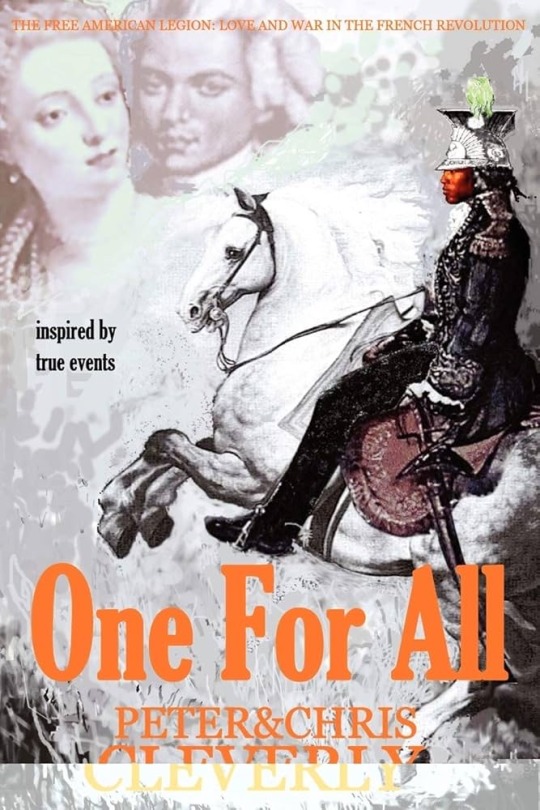

JACOBIN FICTION CONVENTION MEETING 39: ONE FOR ALL (2007)

1. The Introduction

Hello, Citizens! I’m back at it again, reviewing Frev media! Hope you’re happy to see me again in action!

Anyway, today we have an obscure book. A book I found by accident while looking for any media featuring people of color during Frev — which is an overlooked angle in my opinion.

I found this book on Goodreads and, unfortunately, it can only be purchased through Amazon so far… so I had to make an order and wait for the shipping to arrive. Let’s see if the money and the waiting were worth it though!

This review is dedicated to @saint-jussy , @revolutionarywig , @michel-feuilly , @theorahsart and @lanterne .

2. The Summary

I had to “borrow��� the summary from the Amazon page, because it includes some… INTERESTING details:

"In the bloody chaos of the French Revolution an exceptional man comes of age: Alexandre -romantic, intelligent, immensely strong, son of a slave-owning Count and his Haitian first wife.

He accidentally discovers the guilty secret of his new stepmother and her vicious brother. They conspire to destroy him. Cast out by his father, Alexandre is befriended by Chevalier de Saint-George - France's greatest swordsman, Marie-Antoinette’s lover - and falls in love with hot-tempered Marie Labouret.

When Saint-George is wounded helping the Royal Family escape, Alexandre leads the Free American Legion - 1,000 Black lancers - in a brave defence of the Republic against the invading Royalist armies. In ONE FOR ALL the most extraordinary people and amazing events are actual historical fact. Alexandre's son, world-renowned author Alexandre Dumas, found inspiration in the adventures of his father and his father's friend - the Black originals of the much loved characters Porthos and D'Artagnan in THE THREE MUSKETEERS."

I already see a few questionable choices done by the author, but let’s not judge the book too harshly just yet and proceed with the review! I do, personally, love a good swashbuckling story, so it might be a good piece of fiction despite the inaccuracies.

Just put a pin on the “inspired by true events” tidbit included on the cover. You’re going to need to remember this.

3. The Story

I do think that the book has a good prologue, showing Alexandre’s carefree childhood with his parents, where he is a typical child who pulls pranks and doesn’t want to adhere to rules yet. It does a good job of setting up the backstory of the character.

The story proper, I feel, is also doing a good job introducing the characters, especially the stepmother and the step uncle (more on them later). The pacing is also quite good, for the most part, although I really wasn’t that able to turn off my brain and ignore the numerous historical liberties taken by the authors.

Perhaps it would have been better to just make a book about fictional characters instead of the historical ones, but hey. We have what we have.

Also, I didn’t like the fact that the main two villains of the story sometimes lack motivation to do all the shit they pull in the book. As if they are Disney villains whose only trait is “evil”.

For example, the stepmother wants Alexandre cast out so his father doesn’t have him as heir. Pretty standard plotting for an “evil stepmother” type of character, but I occasionally got the feeling that she was only doing it for the evils, even when Alexandre’s father dies and she still attempts to murder her stepson, even though now she has the inheritance she wanted and technically doesn’t need to bother herself with Alexandre’s existence anymore.

But I guess villains just can’t chill out, can they?

Mostly, however, the adventures were quite interesting to follow and I did finish the book in one sitting.

4. The Characters

I do like Alexandre, although at times he seems a bit too idealized in the book. He is kind, brave and chivalrous, just trying to achieve justice and take back the inheritance that is rightfully his.

His stepmother, referred to as “the Countess” in the book, is a standard issue evil stepmother, similar to Madame de Villefort from “The Count of Monte Cristo”. Honestly, the authors do a pretty good job of portraying a vile aristo snake that you just want to see destroyed.

Her brother, de Malpas, is just as evil, and is even incestuous with his sister. As if those two weren’t gross enough. He also murders people left and right for fun, so there’s that.

Chevalier de Saint-George is a character I also liked. He is kind of like a mentor and a brother to Alexandre, and they have a sweet friendship going on!

Marie Labouret is an independent and fierce young woman, but she didn’t seem too modern for the most part.

I couldn’t care less for Alexandre’s father, though. Or rather sperm donor. When the Countess accused her stepson of unspeakable things, this ass immediately through Alexandre out and didn’t even bother to investigate the issue even AFTER the fact. Father of the Year, everybody!!!

5. The Setting

As I mentioned, there are inaccuracies and creative liberties. MANY OF THOSE. That being said, I was pleasantly surprised that the setting wasn’t too bad when it comes to portraying Frev.

There are mentions of mobs killing nobles, as usual, but it’s only mentioned by one character and so we don’t know if it’s true or not.

Also, both Alexandre and Saint-George are still republicans, despite the latter having romantic feelings for the Queen. So the authors at the very least are SOMEWHAT familiar with nuance.

6. The Writing

Sometimes the descriptions are lacking and sometimes the linguistic choices felt a bit too modern to me, but otherwise the writing was quite fine.

7. The Conclusion

All in all, this book is a hit in some ways and a miss in others. I don’t know why the authors twisted history so much when they could have made up their own characters, but the book was still a pretty enjoyable adventure and an interesting experiment.

Read at your own discretion, if you want, but I wouldn’t say I highly recommend it to everyone.

On this note, I declare the Jacobin Fiction Convention closed for now. Stay tuned for future updates!

Love,

Citizen Green Pixel

#general dumas#jacobin fiction convention#one for all#thomas alexandre dumas#joseph bologne#chevalier de saint george

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

l'aventure de canmom à annecy épisode DEUX - lundi partie 2

I ate a late "breakfast" at a cute little french café and made contact with @mendely (shout out to mendely btw, super talented animator) who said he was watching L'Armée des Romantiques*, which sounded pretty fun so I decided to give it a shot!

(*or to give it its clunky English title, Legends of Paris: A Tale of the 19th Century)

This turned out to be a documentary with a limited animation portrayal of a bunch of the artists, writers and composers active in the early 19th Century, framed through the conflict between Romanticism and Classicism. We meet characters like Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo as young up-and-comers trying to make a name for themselves in a France still bubbling with republican sentiment. We watch as these new Romantics are moved to tears by Shakespeare, and write a series of hit plays and novels, with the July Revolution providing some much needed spice in the middle.

It was pretty interesting history, though Mendely tells me they left out some of the spicier anecdotes about his favourite composers. On a presentation level, it does interesting things with paint textures in Revelle for all the BGs, and it was definitely at its strongest when the subject was a painting or symphony where it could actually show us what the big deal was rather than just showing reaction shots. As drama, it was a bit lacking in tension - each of these guys was pretty much guaranteed to cause a stir or they wouldn't feature in this documentary - but it was cool to learn a bit about some artists from this period I know less about, and learn something of the history behind works like Liberty Leading the People. (You know, the one with the titty.)

The next act for me was the world premiere(!) of the film version of Flavours of Iraq, adapting the life of Iraqi-French journalist Feurat Alani. This film was a treat, honestly. The framing device is his father Amir's funeral, and the film cuts between Feurat's life, returning to Iraq after growing up in France, and his communist father's life of political exile after a childhood in Fallujah, later increasingly despairing at the state of his country. Which is a hell of a lot of history to cover in one film, but it handles it very well, a compelling flow of events and reactions in the present unified by Feurat's personal story.

The film has broadly a left wing secularist bent, with little sympathy towards Saddam (seen from a child's eyes as a towering cyclops responsible for Amir's torture and exile), the Americans who cause the country's collapse as they hollow out the state to purge all influence of Saddam, or the Islamists of Al Qaeda and Daesh who flourish in their wake; a little more sympathy goes to the tribal judge who increasingly sides with them after being tasked with counterinsurgency by the Americans, but most of all, the film sympathises with the people low on the hierarchy tossed between all these geopolitical forces. The anchor in personal experiences of Feurat and his extended family avoids it simply becoming a polemic and gives the film a lot of emotional substance. Great soundtrack and stylish animation, later intercut with news footage, do a lot as well - this is edited tight.

Comparison with Persepolis is inevitable - both films use a similar limited colour palette, both films try to flesh out from personal experience a country viewed with ignorance in the west, both first saw publication as a BD before becoming a movie. The thrust of the films is a little different, if only because Iran is in a lot better shape than Iraq - this film is very much a tragedy, and its plea for an Iraq that is not divided by religion or tribe is coloured by the hopelessness of Amir, who unlike his son gives up on his country and applies for French citizenship after his childhood friend is shot as a suspected collaborator. Feurat, too, is haunted by ghosts, such as his cameraman friend Yasser who is killed while interviewing members of Daesh. It is, all in all, quite an overwhelming watch.

Unlike Persepolis, this film's director, also the author of the comic, is not writing autobiographically; apparently the real Feurat wrote about his life on Twitter which was adapted first as a comic and TV series then finally as this film with the funding of various European TV stations and art organisations. It's hard to know how much the real story has been abridged or simplified to make a more compelling narrative. But that's the way of these things, and it certainly felt far more grounded than the likes of The Breadwinner.

The style was also interesting - the flat graphical colours emphasising the eyes, but also moustaches, lips and teeth. The characters are often coloured red against a more desaturated field. For the most part, actual proportions and acting are naturalistic but often it will morph into fantastical symbolic imagery of dogheaded soldiers or a creeping centipede as a rather heavy handed symbol of islamism.

I'm curious how this would be received by Iraqi audiences because tbh it does kinda feel like it's written for westerners but so it goes.

All in all... big dose of history this afternoon, but compelling shit. Next up I'm trying to get into The Birth of Kitaro... no idea if this is going to be lighter, but at least it will be a bit more fantastical. Nevermind, Kitaro is full, going for TV films 5 lmao

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE PORTRAYAL OF THE JUNE REBELLION WE SEE IN LES MISERÁBLES

So, while trying to be funny I made a few posts about barricade day aaand, okay, might have used the term "fictional" when I shouldn't because now apparently some people think I didn't know the revolution actually happened, and while some people just pointed it out I also had to read a very offensive comment calling me a "dumbass" (for a minute I even thought I was using Twitter and not tumblr but anyways)

To clarify it and also to bring actual facts to this day I'm using the knowledge I actually do have on this matter (guess what, I love history) to show a few facts about the revolution we see in the novel and the one that actually happened

In both, the novel/musical and the actual rebellion the catalyst for the rebels was General Jean Lamarque, he was a favorite among the people because of how he appreciated the lower classes' desires and and needs

Historians believe that without Victor Hugo and his romanticism the June Rebellion would probably not even be remembered (make it an underground revolution) since it was such a fast act and since it was primarily a Parisian revolution rather than something that stirred the whole country

Although the starvation that the poor people of Paris were going through is mentioned in the musical and in the original novel there are some facts that influenced the Rebellion that Vicky did not mention, the best example of it is the huge cholera outbreak that swept the country in the spring of 1832

In Victor Hugo's work only one day separates the death of Lamarque from his funeral, in real life there was a 5 day gap between these events

When it comes to the course of the revolution, Les Mis is actually accurate, the shots during Lamarque's funeral happened and then it all lead to the barricades and the infamous cannon fires

Although the people did not rise and the revolution failed, Les Mis kind of reduces our understanding of how big the rebellion actually was, this happens because the book focuses on a group of students (our dear amis) and even for literary purposes it is the right choice, but it gives the impression that like, maybe 40 ou 50 people were hurt or died, while in real life the rebellion had something close to 800 people who were killed or injured

Victor Hugo might not know, but he probably saved a historical event from becoming lost in the world's vast history (and gave us our favorite characters

Les mis is actually only partially accurate if we look at whole context of the revolution and the whole depths of it, but the reason why this isn't a real problem is because it is a novel written by a French romanticist, so naturally he focused on individual redemptions and more simplified ideas of social justice, also, since the book focuses on a specific group of people for plot purposes we can't properly understand how there were actually more people involved than it seems, and that there were more barricades around the city

Some of the characters were actually inspired by people who took part in the real revolution, for example, there was, allegedly, a man who stood in one of the barricades and yelled "Liberty or death" while waving a red flag, and that, as we know, inspired the creation of Enjolras

I think this is it for now, might add something later tho, I hope this clarifies that I actually do know about the real revolution, what I meant was that the literary romanticized revolution we see in Vicky's work is not 100% accurate since it's filled with fictional characters from the novel

When the best fandom reunites to celebrate a non-official holiday based on a revolution mentioned in a 200-year-old novel

#classic literature#les miserables#les mis#victor hugo#les amis de l'abc#happy barricade day#barricade day#isgt im not stupid yall#can we not hate on me pls

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Why I Love The Song "Viva La Vida" By Coldplay

"Viva La Vida" by coldplay is the fourth album of the British Rock Band Coldplay which released on 12 June 2008 on the Parlophone label. Although Viva La Vida is the band's highest grossing album, Coldplay’s song “Viva La Vida” is an interpretation of king Louis’s lost last speech before his death. The song is written through King Louis point of view, as he apologizes to his people, accepting his fate.

The album cover art features the 1830 historical painting known as “Liberty Leading the People”. The art piece was painted by French artist Eugène Delacroix, depicting French revolutionaries marching and waving the French flag, led by the human manifestation of Lady Liberty. The painting serves to portray the revolutionaries in a heroic light, complementing the Album’s themes of life, death, war, and change.

“I used to rule the world Seas would rise when I gave the word Now in the morning, I sleep alone” — King Louis led one of the world’s most powerful countries, he commanded hundreds of ships with his simply words. However, now he was reduced to sleeping alone in a jail cell.

“Listen as the crowd would sing: “Now the old king is dead! Long live the king!” — King Louis XVI succeeded the throne after his grandfather had passed. Following the death of the beloved king, Louis XV, Louis XVI held much potential in his people’s eyes. Many celebrated his rise to kingship.

“Shattered windows and the sound of drums People couldn’t believe what I’d become.” — Although his people saw much potential in the new king, they were left disappointed. His early reign was that of reform and success, however, as time grew and promises were left unfulfilled, the French masses demanded a new order.

“Revolutionaries wait for my head on a silver plate. Just a puppet on a lonely string. Oh who would ever want to be king?” — Louis recognizes that revolution was now in full swing and that no amount of reform can help him now. Although Louis accepted his Kingship in eagerness, he looks back at his powers as a burden. He admits that the power he thought he wanted was not the same when he held it.

Unlike Delacroix’s “Liberty Leads the People”, which shows the revolutionaries as heros. The songs takes a complete 180 by showing sympathy for the fallen king. The song is a admittance of guilt by the king. This regret humanizes the King, showing understanding that he had ultimately failed his people.

Once a revolutionary himself, the first part of his reign was that of enlightenment reform, however, along his kingship he had lost sight of his values. Retreating to the comforts of his palace rather than facing his problems. The songs shows the regret of a man who once promised so much more but delivered none, accepting his fate as he knows it is well deserved.

This contrast is a deliberate choice to reinforce the album’s theme of change. With the revolutionaires fierce march and the King’s introspective review, the listener is not put onto a single side. Instead, it allows the listener to process both perspectives, allowing a completely new view of the revolution.

So people tell me what to do you feel about this song and the fallen king was he truly a villain or misunderstood man in a terrible time?

1 note

·

View note

Text

The 8 most famous French paintings of all time.

French art has created some of the world's most famous and important artworks, which captivate viewers with their beauty, emotion, and historical relevance. From the enigmatic grin of the "Mona Lisa" to the whirling stars of "The Starry Night," these works have made an unforgettable impression on art history. One of the most renowned French paintings of all time is Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa," which is displayed at Paris's Louvre Museum. This timeless depiction of a woman with a secretive grin has captivated audiences for ages, serving as a symbol of Renaissance creativity and mystery. Vincent van Gogh's "The Starry Night" is another well-known French artwork, distinguished by its vibrant colours and swirling brushstrokes. This masterpiece depicts the artist's emotional agony and creative talent. Other prominent French paintings include Eugène Delacroix's "Liberty Leading the People," Édouard Manet's "Olympia," and Théodore Géricault's "The Raft of the Medusa." Each of these pieces offers a distinct tale while reflecting the creative movements and cultural circumstances of the time. With their beauty, meaning, and historical relevance, the most renowned French paintings continue to inspire and enchant audiences all over the world, demonstrating art's eternal ability to transcend time and place.

Here are some of the most famous French paintings of all time.

1. "Mona Lisa" by Leonardo da Vinci: The "Mona Lisa" is possibly the world's most renowned painting, and it is kept in the Louvre Museum in Paris. During the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci painted this intriguing picture of a woman with a strange smile, which has fascinated audiences for ages.

2. Vincent van Gogh, "The Starry Night": A famous painting by Vincent van Gogh, "The Starry Night," shows the night sky over the hamlet of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. The famous artwork, renowned for its vivid hues and whirling clouds, is kept at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

3. Eugène Delacroix, "Liberty Leading the People": Eugène Delacroix's striking picture "Liberty Leading the People" portrays the July Revolution of 1830 in France. A representation of liberty personified a woman leading the populace over barricades has come to represent liberation and revolution.

4. Édouard Manet's "Olympia": Édouard Manet's controversial painting "Olympia" features a reclining, naked woman gazing straight at the observer. When this controversial picture was initially displayed in 1865, it created a stir and questioned accepted ideas of morality and beauty.

5. Théodore Géricault's "The Raft of the Medusa": Théodore Géricault's dramatic painting "The Raft of the Medusa" shows the aftermath of the French navy ship Méduse's 1816 crash. This enormous piece, which is kept at the Louvre Museum, is a poignant representation of the pain and resilience of people.

6. Sandro Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus": Sandro Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus" is a masterwork of the Italian Renaissance. This famous picture, which shows the goddess Venus rising from the sea on a shell, represents beauty, love, and the human form.

7. Édouard Manet's "The Luncheon on the Grass": Édouard Manet's controversial artwork, "The Luncheon on the Grass," shows a naked woman enjoying a picnic in a rural area with two fully dressed guys. This ground-breaking 1863 exhibition piece startled viewers with its unusual subject matter and realistic portrayal.

8. Auge Rodin's "The Thinker": Auguste Rodin is a well-known sculptor whose "The Thinker" was initially intended to be a component of his bigger piece, "The Gates of Hell." This famous sculpture, which shows a man lost in reflection, has come to represent intellectualism and introspection.

Conclusion

Finally, the most famous French paintings of all time remain eternal treasures of creative expression and cultural legacy. From the enigmatic grin of the "Mona Lisa" to the emotional brushstrokes of "The Starry Night," these works continue to captivate and inspire audiences across the world. For art fans who want to see these great masterpieces firsthand, acquiring a France visa from Delhi is the key to embarking on a trip through the rich tapestry of French artwork. With a France visa, travelers may explore the galleries of the Louvre Museum in Paris, which houses the "Mona Lisa" and numerous other treasures.

Aside from the "Mona Lisa," visitors may see the paintings of French painters such as Eugène Delacroix, Édouard Manet, and Vincent van Gogh, each with a unique viewpoint on art and society. Exploring the most renowned French paintings is not only about enjoying brushstrokes and colours; it's about digging into the tales, emotions, and historical circumstances behind each masterpiece. Whether you're gazing at the revolutionary zeal of "Liberty Leading the People" or delving into the complexity of "Olympia," these paintings urge us to consider the human experience and the eternal power of imagination. The most renowned French paintings, with their beauty, complexity, and cultural relevance, serve as reminders of art's global language and its tremendous effect on our lives.

Read More -: France Tourist Visa From Mumbai, France Tourist Visa From Bangalore

#France Visa From Delhi#France Visit Visa From Delhi#France Tourist Visa From Delhi#France Visit Visa Processing Time From Delhi#France Tourist Visa Cost From Delhi#France Tourist Visa Price From Delhi#France Visa Appointment In Delhi

0 notes

Text

gotta love showing my best friend art. it’ll be liberty leading the people, a major romantic work that used allegory to capture the ideals of the French Revolution, and she’ll ask me “are those her titties”. priorities I guess

0 notes

Text

vincenzo: anti-capitalism, moral greyness, and katharsis

or, why watching vincenzo is both satisfying and blood-thirst-inducing

this analysis is a response to the wonderful discussions on this topic already flourishing in the fandom, and an attempt to synthesize and expand on the points already raised by others. let’s dive in!

anti-capitalism

vincenzo’s aim as a work of art is not only to engage and delight an audience, but more importantly to inspire a civic consciousness among it. by building the central conflict around the crimes of a capitalist conglomerate easily exchanged with any big company anywhere in the world, the writer directs our attention towards the violation of human rights that such enterprises commit in our everyday reality. by explicitly showing the atrocities orchestrated by its boss and his underlings time and again - their tireless, shameless suppression and falsification of the truth in the name of greed and ambition, their disregard for the lives of people they deem to be ‘lesser’ - the narrative inspires the anger and contempt we should direct towards the perpetrators of this system in our daily lives. by making both people who are far and close to the protagonists the direct and indirect victims of this company’s tyranny and portraying side and main characters’ pain in the aftermath of these crimes, the series makes us bear witness to the ‘casualties’ of unchecked economic growth and realize its inherent inhumanity. by demonstrating how members of the private sector, the jurisdiction, and the media all contribute to the upholding of the company’s myth and conspire to prevent each other’s downfall, vincenzo exposes the rotten state of the system along with its relentless oppression of those who refuse to play by its crooked rules.

this message is underlined by the series’ explicit, frequent references to the class war in the form of its symbolic invocation of the french revolution through the reconstruction of liberty leading the people and the name of the ‘guillotine’ file as well as its off-hand references to parasite, a film which illuminates the horrific consequences of the struggle between the rich and the poor. it is even directly addressed through the conversation between the tenants after prosecutor jung’s betrayal in ep.15, in which they wonder about their newfound awareness of corruption and corporate propaganda, and understand that the political is personal and the personal is political.

one of the chilling ways in which vincenzo reminds us of how vulnerable we are to the abuse of power perpetuated by big corporations is through the fact that the four relatives of babel’s victims are targeted and murdered thanks to the retrieval of their text messages from their phone providers, an extreme example of the privacy violation that data collectors and controllers are capable of committing at any time.

the audience’s warranted anger against capitalism is focused towards the characters of han seok and myung hee, and the extremity of our bloodlust for their suffering demonstrates how successful the series has been in achieving its aim. while han seok’s diagnosis as a psychopath almost provides an excuse for his nonexistent understanding of basic human morality, the character of myung hee is a fascinating case study of the moral corruption caused by extreme ambition and blind commitment to climbing the corporate ladder. her introduction as a potentially positive character is telling of her capacity to be one in different circumstances, but her deliberate steps over corpse after corpse of her creation demonstrates her willingness to cross any boundary on her way to accumulate more power as quickly as possible. the recurring scenes of myung hee’s gratuitous consumption of food during or after a murder of her planning provide a visual metaphor for her symbolic devouring of her victims’ life forces on her way to the top. while oppressors at the bottom of the chain like the bye bye balloon crew can read the wake-up call of their own abuse by the system, those at the very top like myung hee have to fully embrace the position of exploiter in order to thrive.

moral greyness

who is bold and tenacious enough to not only defeat these monsters, but return the suffering they have caused tenfold?