#seleucid suggestions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Painted Scylla Statues Found in Turkey

Excavations in ancient Laodicea have revealed a rare collection of painted Scylla statues.

Laodicea was an Ancient Greek city on the river Lycus, located in the present-day Denizli Province, Turkey.

The city was founded between 261-253 BC by Antiochus II Theos, king of the Seleucid Empire, in honour of his wife Laodice. Over the next century, Laodicea emerged as a major trading centre and was one of the most important commercial cities of Asia Minor.

After the Battle of Magnesia during the Roman–Seleucid War (192–188 BC), control of large parts of western Asia Minor, including Laodicea, was transferred to the Kingdom of Pergamon. However, the entire Kingdom of Pergamon would eventually be annexed by the expanding Roman Republic in 129 BC.

The many surviving buildings of Laodicea include the stadium, bathhouses, temples, a gymnasium, two theatres, and the bouleuterion (Senate House).

Recent excavations led by Prof. Dr. Celal Şimşek from Pamukkale University have revealed a rare collection of painted Scylla statues during restoration works of the stage building in the Western Theatre.

In Greek mythology, Scylla is a man-eating monster who lives on one side of a narrow strait, opposite her counterpart, the sea-swallowing monster Charybdis. The two sides of the strait are so close (within an arrow’s range), that sailors trying to avoid Charybdis’s whirlpools would dangerously come into range of Scylla.

Scylla is first mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey, where Odysseus and his crew encounter both Scylla and Charybdis during their voyage back to Ithica following the conclusion of the Trojan War.

In a press statement by Nuri Ersoy, Minister of Culture and Tourism: “These extraordinary sculptures are quite important in terms of being rare works that reflect the baroque style of the Hellenistic Period and have survived to the present day with their original paints.”

The archaeologists suggest that the sculptures were made by sculptors in Rhodes during the early 2nd century BC and are the oldest known examples from antiquity.

#Painted Scylla Statues Found in Turkey#ancient Laodicea#ancient greek city#sculptures#ancient sculptures#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#greek history#roman history#roman empire#greek art#ancient art#art history

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

history of the hebrew bible

—1250-1000 bce israel emerges in the highlands of canaan, holding oral narratives of the pentateuch (abraham, if historical, ca. 1800, moses ca. 1250)

—1050 bce the united monarchy forms. saul's reign ca. 1050. david's ca. 1000. solomon's ca. 960. the latter erects the temple. the first former prophets are summoned

—ca 950 bce the oral narrative of the pentateuch is recorded in hebrew. some scholars name this earliest source the yahwist

—922 bce the kingdoms separate into israel in the north (capital samaria) and judah in the south (capital jerusalem). more former prophets are summoned, as well as the latter and the twelve

—ca 850 bce the so-called elohist source records oral narratives of the pentateuch. they may have access to the yahwist source

—722/21 bce assyria ruins samaria, exiles population. this exile affects prophets from the north such as amos and hosea

—621 bce josiah "finds" a scroll in the temple. this deuteronomist source reifies his reforms

—606 babylon and medes ruin nineveh

—597-596 bce babylon ruins jerusalem, namely, the temple. exiles population. this exile affects prophets from the south such as ezekiel and jeremiah

—ca 550 bce the priestly source, keen on re-membering in the midst of exile, records oral narratives of pentateuch. they made use of earlier written sources (so-called j, e, and d sources). some scholars suggest most, if not all, of the hebrew narrative is in fact recorded in this exile period

—539 bce persia ruins babylon, returns judean exiles, allows for temple to be rebuilt

—520-515 bce the temple rebuilt in jerusalem. this starts the 'second temple period'

—400 bce the torah section of the canon reaches its final form

—336-323 bce alexander the great ruins persia

—312-198 bce ptolemies of egypt reign over judah. the dead sea scrolls are composed ca. 300-100 bce. seleucids conquer jerusalem ca. 198

—200s bce LXX is composed in greek. the prophets section of the canon reaches its final form

—168/167 bce syria reigns over jerusalem. maccabean revolt

—33 ce a rabbi from nazareth with kind eyes hangs on a cross

—40s-60s ce a pharisee falls off a horse, sends letters to house churches (pauline epistles)

—66-70 ce the second temple is destroyed

—60s-110s the four gospels of the second testament are written. a fifth one, named q, may or may not be lost at this time

—100 ce the writings section of the canon reaches its final form

—300-400 ce codex vaticanus and codex sinaiticus composed

—600-900 ce the MT is rendered. hebrew is afforded vowels, finally. aleppo codex and cairo codex composed

#for anon#these are wellhausen's dates and for the record i dont subscribe wholly to any four source hypothesis but for the sake of our final exam#which i hope youre studying for#its good to know these#faq

83 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have any sources on the worship of the goddess inanna/Ishtar during the Seleucid/Hellenistic period to the Parthian period? i dont recall stumbling upon anything talking about her.

even though from what I've been reading mesopotamian deities were still popular (like bel-marduk in Palmyra and nabu in Edessa or shamash in hatra and mardin or sin in harran etc etc.. ) i dont recall reading anything about her or anything mention her worship (other than theories of the alabaster reclining figurines being depictions of her)

A good start when it comes to late developments in Mesopotamian religion is Religious Continuity and Change in Parthian Mesopotamia. A Note on the survival of Babylonian Traditions by Lucinda Dirven.

Hellenistic Uruk, and by extension the cult of Ishtar, is incredibly well documented and the most extensive monograph on this topic, Julia Krul’s The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk, is pretty much open access (and I link it regularly here, and it's one of my to-go wiki editing points of reference as well); it has an extensive bibliography and the author discusses the history of research of the development of specific cults in Uruk in detail. The gist of it is fairly straightforward: her status declined because with the fall of Babylon to the Persians the priestly elites of Uruk decided it’s time for a reform and for the first time in history Anu’s primacy moved past the nominal level, into the cultic sphere, at the expense of Ishtar and Nanaya. Even the Eanna declined, though a new temple, the Irigal, was built essentially as a replacement; we know relatively a lot about its day to day operations. An akitu festival of Ishtar is also well documented, and Krul goes into its details. All around, I don’t think the linked book will disappoint you.

An important earlier work about the changes in Uruk in Paul-Alain Beaulieu’s Antiquarian Theology in Seleucid Uruk. There’s also Of Priests and Kings: The Babylonian New Year Festival in the Last Age of Cuneiform Culture by Céline Debourse which covers Uruk and Babylon, but there is less material relevant to this ask there. Evidence from Upper Mesopotamia and beyond is more fragmented so I’ll discuss it in more detail under the cut. My criticism of this take on the reclining figures is there as well.

The matter is briefly discussed in Personal Names in the Aramaic Inscriptions of Hatra by Enrico Marcato (p. 168; search for “Iššar” within the file for theophoric name attestations). References to a deity named ʻIššarbēl might indicate Ishtar of Arbela fared relatively well (for her earlier history see here and here) in the first centuries CE. The evidence is not unambiguous, though. This issue is discussed in detail in Lutz Greisiger’s Šarbēl: Göttin, Priester, Märtyrer – einige Probleme der spätantiken Religionsgeschichte Nordmesopotamiens. Theophoric names and the dubious case of ʻIššarbēl aside, there are basically no meaningful attestations of Ishtar from Hatra, but curiously “Ishtar of Hatra” does appear in a Mandaic scroll known as the “Great Mandaic Demon Roll”. According to Marcato this evidence should not be taken out of context, and additionally it cannot be ruled that we’re dealing with a case of ishtar as a generic noun for a goddess (An Aramaic Incantation Bowl and the Fall of Hatra, pages 139-140; accessible via De Gruyter). If this is correct, most likely Marten (the enigmatic main female deity of the local pantheon), Nanaya or Allat (brought to Upper Mesopotamia by Arabs settling there in the first centuries CE) are actually meant as opposed to Ishtar.

Joan Goodnick Westenholz suggested that Mandaic sources might also contain references to Ishtar of Babylon: the theonym Bablīta (“the Babylonian”) attested in them according to her might reflect the emergence of a new deity derived from Bēlet-Bābili (ie. Ishtar of Babylon) in late antiquity (Goddesses in Context, p. 133)

In addition to Marcato’s article listed above, another good starting point for looking into Mesopotamian religious “fossils” in Mandaic sources is Spätbabylonische Gottheiten in spätantiken mandäischen Texten by Christa Müller-Kessler and Karlheinz Kessler; Ishtar is covered on pages 72-73 and 83-84 though i’d recommend reading the full article for context. The topic is further explored here.

In his old-ish monograph The Pantheon of Palmyra, Javier Teixidor proposed that the sparsely attested local Palmyrene goddess Herta (I’ve also seen her name romanized as Ḥirta; it’s agreed that it’s derived from Akkadian ḫīrtu, “wife”) was a form of Ishtar, based on the fact she appears in multiple inscriptions alongside Nanaya (p. 111). She is best known from a dedication formula where she forms a triad with Nanaya and Resheph (Greek version replaces them with Hera and Artemis, but curiously keeps Resheph as himself). However, ultimately little can be said about her cult beyond the fact it existed, since a priest in her service is mentioned at least once.

I need to stress here that I didn’t find any other authors arguing in favor of the existence of a supposed Palmyrene Ishtar. Joan Goodnick Westenholz mentioned Herta in her seminal Nanaya: Lady of Mystery, but she only concluded that the name was an Akkadian loanword and that she, Resheph and Nanaya indeed formed a triad (p. 79; published in Sumerian Gods and their Representations, which as far as I know can only be accessed through certain totally legit means). Maciej M. Münnich in his monograph The God Resheph in the Ancient Near East doesn’t seem to be convinced by Teixidor’s arguments, and notes that it’s most sensible to assume Herta seems to be Nanaya’s mother in local tradition. He similarly criticizes Teixidor for asserting Resheph has to be identical with Nergal in Palmyrene context (pages 259-260); I’m inclined to agree with his reasoning, interchangeability of deities cannot be presumed without strong evidence and that is lacking here.

I’m not aware of any attestations from Dura Europos. Nanaya had that market cornered on her own. Last but not least: I'm pretty sure the number of authors identifying the statuettes you’ve mentioned this way is in the low single digits. The similar standing one from the Louvre is conventionally identified as Nanaya (see ex. Westenholz's Trading the Symbols of the Goddess Nanaya), who has a much stronger claim to crescent as an attribute (compare later Kushan and Sogdian depictions, plus note the official Seleucid interpretatio as Artemis for dynastic politics purposes), so I see little reason to doubt reclining figures so similar they even tend to have the same sort of gem navel decoration are also her, personally.

A great example of the Nanaya-ish statuette from the Louvre (wikimedia commons). To sum everything up: while evidence is available from both the south and the north, the last centuries BCE and first centuries CE were generally a time of decline for Ishtar(s); for the first time Nanaya was a clear winner instead, but that's another story...

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

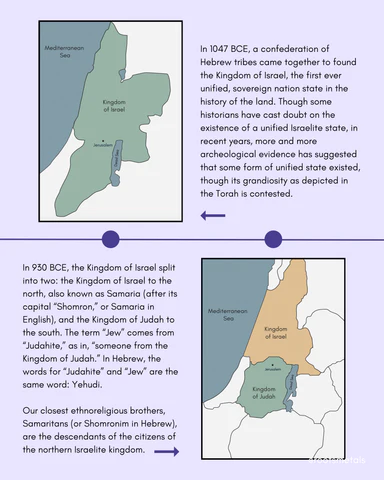

In 1047 BCE, a confederation of Hebrew tribes came together to found the Kingdom of Israel, the first ever unified, sovereign nation state in the history of the land. Though some historians have cast doubt on the existence of a unified Israelite state, in recent years, more and more archeological evidence has suggested that some form of unified state existed, though its grandiosity as depicted in the Torah is contested.

In 930 BCE, the Kingdom of Israel split into two: the Kingdom of Israel to the north, also known as Samaria (after its capital “Shomron,” or Samaria in English), and the Kingdom of Judah to the south. The term “Jew” comes from “Judahite,” as in, “someone from the Kingdom of Judah.” In Hebrew, the words for “Judahite” and “Jew” are the same word: Yehudi.

Our closest ethnoreligious brothers, Samaritans (or Shomronim in Hebrew), are the descendants of the citizens of the northern Israelite kingdom.

When the Babylonian Empire conquered Judah in 587 BCE, the territory of the Kingdom of Judah went on to become a province of the Babylonian Empire (587-539 BCE), the Persian Empire (539-332 BCE), the Seleucid Empire (332-37 BCE), and finally, the Roman Empire, which is depicted in green in the map to the left. “Judea” is merely a Romanized version of “Judah.”

After the Romans crushed the Bar Kokhba Revolt in the year 135, Emperor Hadrian carried out a retaliatory genocide against the Jewish people that took some 600,000 lives. Part of his genocidal agenda was to erase any trace of Jewish presence and autonomy in the land. To do so, he dissolved the Roman province of Judea and united it with Syria, creating Syria-Palestina. Syria-Palestina was then divided into Palestina Prima, Palestina Secunda, and Palestina Tertia. “Palestine” derives from “Philistines,” the ancient enemies of the Israelites in the Hebrew Bible. They were of Greek origin, unrelated to today’s Palestinians.

After the Arab conquest in the 7th century, what is now Israel and the Palestinian Territories became a part of Bilad al-Sham, or the province of Syria. There is a reason early Palestinian nationalists in the 20th century advocated for a unified Palestinian and Syrian Arab state in Greater Syria.

At this time, Jund Filastin, translating to “the military district of Palestine,” was a military district encompassing the green region surrounding Jerusalem.

All throughout 1280 years of Islamic rule, the territories now encompassing Israel and the Palestinian Territories belonged to some variation of a Syrian province.

The map on the left is of Ottoman Syria (1517-1917), which itself was further split up into various vilayets (administrative divisions).

In the wake of World War I, the British and French conspired to carve up the Middle East amongst themselves, thus creating the borders for much of the region as we know it today. The map that we are familiar with as Israel and the Palestinian Territories is a British invention.

The British also chose to revive the Roman name “Palestine” as a political entity for the first time since the year 636.

Transjordan, seen in brown above, was originally assigned to the British Mandate for Palestine (1917-1948), though in 1923, the British handed the territory over to the Hashemite family, an ancient dynasty that traces its origins to the Arabian Peninsula. Throughout the period of the Mandate, Jews were not allowed to settle anywhere in Transjordan.

Until 1920, early Palestinian nationalists wanted Palestine to become a province of the pan-Arabist Greater Syria, which would include Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and the Palestinian Territories.

At the first Palestinian Arab Congress 1919, the resolutions included statements such as, “We consider Palestine nothing but part of Arab Syria and it has never been separated from it at any stage…Our district Southern Syria or Palestine should be not separated from the Independent Arab Syrian Government and be free from all foreign influence and protection.”

ORIGINS OF ISRAEL

The earliest known mention of “Israel” in history — and the earliest mention of Israel outside of the Torah — is 3200 years old and was discovered in Thebes, Egypt, in 1896.

The mention is found in what is known as the Merneptah Stele, an inscription by the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah, who reigned between 1213 BCE to 1203 BCE. The Stele itself is dated to 1208 BCE. It’s written in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The Merneptah Stele mainly describes Merneptah’s victory over the ancient Libyans. However, three of the 28 lines talk about a separate Egyptian military campaign in Canaan. It reads:

“The Canaan has been plundered into every sort of woe:

Ashkelon has been overcome;

Gezer has been captured;

Yano’am is made non-existent.

Israel is laid waste and his seed is not;

Hurru is become a widow because of Egypt.”

The hieroglyphs used describe Ashkelon, Gezer, and Yano’am as city-states, whereas “Israel” is described as a foreign (to Egypt) people. This suggests that at this point in time, the Israelites did not rule over a unified state, but rather, were a nomadic or semi-nomadic tribe(s). This would corroborate the narrative of the Torah, as the Kingdom of Israel did not become a unified state until some 161 years later.

As a side note, it’s interesting that the first ever mention of Israel in history comes from a ruler bragging about our supposed destruction. Over three millennia later, here we are.

In 1040 BCE, a loose confederation of Hebrew tribes united to form the first centralized state in the Land of Israel, known as the Kingdom of Israel.

The Hebrew tribes originated -- and later split away -- from the Canaanites, a loose group of semi-nomadic tribes that lived during the second millenium BCE; they were the original inhabitants of the Land of Israel. Though depicted as the enemies of the Israelites in the Torah, archeologists, linguists, Biblical historians, and geneticists today widely agree that the ancient Hebrews were originally Canaanites themselves. The Tanakh itself even makes some vague references to the Hebrews’ Canaanite origins. Ezekiel 16:3 tells us, “Thus said the sovereign God to Jerusalem: by origin and birth you are from the land of the Canaanites — your father was an Amorite and your mother a Hittite.” The Amorites were a Canaanite people.

It was customary at the time and in the region for nations to name themselves after their most important deities. For example, Israel’s neighboring Assyria named itself after the Mesopotamian deity “Ashur.” “El” was the most important god in the Canaanite pantheon; over time, the cult of El and of the southern deity YHWH merged to form the Hebrew God as we know Him today. “Israel,” then, translates to “one who wrestles with El [that is, God].”

Until 1948, the United Kingdom of Israel (1047-930 BCE), the southern Kingdom of Israel (930-722 BCE), and the Kingdom of Judah (930-587 BCE) were the only ever sovereign nation states in the entirety of the land’s history. At all other times, the region was a colony, vassal state, or province of some foreign empire whose administrative center was elsewhere. The founding of the State of Israel in 1948 marked the first time that the land belonged to a fully sovereign, independent state in over 2500 years.

ORIGINS OF PALESTINE

Historians have long debated the origins of the name “Palestine.” Most believe that the word derives from the Hebrew and Ancient Egyptian word “peleshet,” translating to “invader” or “migratory.” “Peleshet” was used to describe the Philistines, who settled on the Mediterranean coastline above Egypt, in parts of what is now Israel and Gaza. The Philistines were a seafaring people of Greek origin, entirely unrelated to today’s Palestinians, who are an Arab ethnonational group. Some Palestinians, particularly Christian Palestinians and Palestinians from the city of Nablus, have Jewish and Samaritan ancestry, respectively.

The first use of the word “Palestine” to describe a geographic region was in the 5th century BCE, at least 700 years after the first use of the word “Israel.” Like the Land of Israel, “Palestine” was a loose region, describing the coastal strip that runs from Egypt to Lebanon. However, unlike “Israel,” Palestine was not a political entity until the Romans renamed Judea “Syria-Palestina” in the second century CE.

Another, newer, more controversial theory asserts that “Palestine” derives from the Greek word “Palaistes,” meaning “wrestler.” If you recall, the term “Israel” means “one who wrestles with God.” According to this theory, “Palestine” is a direct Greek translation of “Israel.”

For hundreds of years, the term “Palestinian” was virtually synonymous with “Jew.” In the 18th century, for example, Immanuel Kant described the Jews in Europe as “the Palestinians among us.” In the early 20th century, Jews used “free Palestine” as a rallying call to establish a Jewish state.

The first Arab Palestinian to identify as Palestinian was Khalil Beidas in 1898, though the term was not universally used until the 1960s. During the 1937 Peel Commission, Palestinian Arab nationalist Anwi Abd al-Hadi told the British, “Palestine is a term the Zionists invented!”

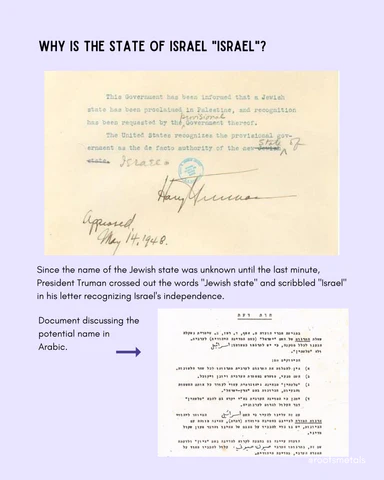

WHY IS THE STATE OF ISRAEL "ISRAEL"?

Though the second Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Assyrians in 722 BCE, both Jews and Samaritans continued referencing to the land as “Eretz Israel,” or the Land of Israel, for three millennia. When the Maccabees briefly gained a semblance of independence after the Maccabean Revolt (167-141 BCE), they referred to their new semi-autonomous kingdom as “Judea” and “Israel” interchangeably. During the Bar Kokhba Revolt against the Roman Empire (132-135 CE), the revolt leader, Simon Bar Kokhba, was known as the “prince of Israel.”

Even during the British Mandate (1917-1948), the official name of Palestine was the “British Mandate of Palestine (Aleph Yud).” Aleph Yud are the letters corresponding to the abbreviation for “Eretz Israel,” the Land of Israel.

Even so, most assumed that the new Jewish state would be called “Judea,” or “Yehuda” in Hebrew. In 1949, on the first anniversary of the State of Israel, Zeev Sharef, who had been present during the deliberations, explained why the name “Judea” was quickly discarded: “Most people had thought that the state would be called Judea. But Judea is the historical name of the area around Jerusalem, which at that time seemed the area least likely to become part of the state...So Judea was ruled out.”

The Provisional Government of the State of Israel also spent some time deliberating on what the name for the country would be in Arabic. Initially they considered Palestine, or "Filastin" in Arabic, to "take the feelings of the Arab minority into account." But the idea seemed too confusing, because they assumed an Arab state would be established alongside the Jewish state, and that Arab state would likely be called Palestine. As such, the idea was discarded. Instead, Israel is called "Isra'il" in Arabic.

Since a lot of you guys seem to have a problem with reading comprehension, let me comprehend this for you: the point of this post is *not* to say only Jews have a right to live in the land, or to say that I unequivocally support everything the Israeli government has done, is doing, & will continue to do forever into eternity.

the point is: (1) the idea that Israel is “colonial” is ahistorical & antisemitic because it is a blatant erasure of Jewish history & identity, (2) the idea that Palestine is “anti-colonial” is also ahistorical and also an erasure of Jewish history, & (3) the “river and the sea” that you’re so damn attached to in the name of “anti-imperialism”?Yeahhhh those borders were a British invention.

For a full bibliography of my sources, please head over to my Instagram and Patreon.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every time I try to tag some thing as trans whatever, Tumblr suggests #biblical trans shitposting, and every time I'm sad I don't have more content for that tag.

The world needs more biblical trans shitposting, damn it.

So, uhh.. Let me just do some biblical shitposting:

Jesus is obviously a trans man, so is Noah and Saul/Paul, Rahab was a trans woman, and God is non-binary.

Angels are too, but they don't have sex in either way. They're tools. And not like the kind you might talk about having in your pants.

And speaking of pants, Deuteronomy 22:5 (no cross dressing) , much like Leviticus 18 (no gay sex) were both intended as "don't do the weird shit those foreigners do" rules that were and are being taken out of context. They're not intended as eternal and universal commandments in what is morally right and wrong in the world.

Also when I said "Noah" up there, I meant Moses, because both Jesus and Moses were born at a time of KILL ALL THE BOY BABIES and survived. But fuck it... Noah is trans too now.

God said so. They called me up on my orange hotline phone. (I'm a pope, so I get a direct line to the big G)

Who else is trans... Eve, obviously, by the same reasoning as Jesus (they both only have one "parent" who could have given them chromosomes, and yet are a different gender to them).

Sarah (wife of Abraham) too. She's got it all: meaningful name change and she laughed when told she'd have a child. Was that just because she was already old... Or because she didn't have a uterus?

(well, through God all things are possible, so jot that down Sarah)

Joseph (of the many colored coats) is another trans man. Man (no pun intended), the Bible is just full of trans men.

As I've said before, the victim in the story of the good Samaritan is trans, especially now.

Also not to get off the subject of being trans (do I ever?) but I was just thinking that a running theme of the Bible is "The Empire".

There's aways the Empire. Who they are changes from book to book, but they're always there. Babylon, Egypt, the Seleucid empire, the Romans, the future world-spanning empire john talks about in Revelation... They're big and powerful and oppressive and cannot be fought in traditional ways, but they will not win. They can't. They won't. They may be horrible and causing so much pain right now but they will be overcome and we will be free and safe one day.

And really, if that's not a good message for trans people right now, I don't know what is.

285 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ardashir I

Ardashir I (l. c. 180-241 CE, r. 224-240 CE) was the founder of the Persian Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE) and father of the great Sassanian king Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE). He is also known as Ardashir I Babakan, Ardeshir I, Ardashir the Unifier, and Ardashir Papakan.

He was the son of the prince of Istakhr, Papak (also given as Babak and Papag, r. c. 205-210 CE) and the Princess Rodak of the Shabankareh tribe (suggested by some scholars as Kurdish) and born in Tirdeh, Persis c. 180 CE. He is also believed to have been grandson of the High Priest of Zoroastrianism, Sasan (c. 3rd century CE), after whom the Sassanian Empire is named, though some evidence suggests he was Sasan's son and later adopted by Papak.

Ardashir I was a general in the Parthian army under the reign of the king Artabanus IV (r. 213-224 CE). His family controlled the symbolically significant region of Istakhr where the ruins of the Achaemenid capital of Persepolis lay. Even though the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) was a distant memory, it still resonated powerfully throughout the region at the time of Ardashir I, and his family refused to relinquish control of it to Artabanus IV. Further complicating relations between the two, Ardashir I had made significant gains for himself in the region at the expense of Artabanus IV whose power was waning.

In 224 CE, Ardashir I defeated Artabanus IV in battle, toppling the Parthian Empire (247 BCE - 224 CE) and founding his own which he modeled on the success of the earlier Persian Achaemenid Empire. He soon after concentrated his efforts on urban development and military campaigns against Rome which were universally successful. He co-ruled with his son Shapur I toward the end of his reign and died peacefully after assuring that the empire he had founded would continue in good hands. He is considered one of the greatest kings of the Near East generally and of the Sassanian Empire specifically.

Failing Parthian Empire

After the fall of the Achaemenid Empire to Alexander the Great in 330 BCE, the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE) held the region until they were replaced by the Parthians. The Parthian king Arsaces I (r. 247-217 BCE) established an independent kingdom of Parthia while the Seleucids were still firmly in control but, as their power waned, Parthia took advantage and enlarged their territories, finally controlling the majority of what had once been the Achaemenid Empire.

Recognizing the weakness of a centralized government – and especially of a centralized military deployed from a set point (as in the case of both the Achaemenids and Seleucids) – the Parthians decentralized both to enable more efficient administration and defense. Parthians satraps had a greater degree of autonomy and could field armies for defense without having to consult with the king first.

This model worked well for the Parthians for most of the empire's history but, by the time Ardashir I was born, their vitality was being steadily drained through engagements with the Roman Empire and internal dissent. The decentralization which had worked so well earlier was now a liability because Rome could field more men which small armies from individual satrapies could not contend with. Further, the autonomy of the satraps by this time resulted in mini kingdoms within the empire which were more concerned with their own self-interest than the preservation of the empire.

Continue reading...

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! i’m writing an essay on the shift of helios as a sun god to apollo being the main sun god, and wondered whether you had any resources on it, or an opinion of why this happened! the topic is so so interesting to me since there are a lot of different perspectives on it, but it’s difficult to find concrete evidence on exactly when/what period it happened. if not don’t worry, but i’d love to hear your perspective on it.

hope you’re doing well, and thank you :))

Hi! Here are some suggestions for resources that might be useful to what you're looking for:

The Neglected Heavens: Gender and the Cults of Helios, Selene, and Eos in Bronze Age and Historical Greece by Katherine A. Rea: she places the switch in the 5th century BC and only cites Athenian evidence, and makes other interesting points on the topic.

In the common precinct dedicated to Apollo and Helios (Plato, Lg., 945 b-948 b) by Miguel Spinassi (in Spanish): This is mainly a philosophical analysis, but you might be able to find some interesting ideas concerning the syncretism through the philosophical lens.

The cult of Helios in the Seleucid East by Catharine C. Lorber & Panagiotis P. Iossif: this is more indirect and later down the timeline for you, but could give you leads as to the political role of the syncretism in the context of the Seleucid kingdom and why it spread so widely outside of "mainland Greece".

Two works by Tomislav Bilić might also be of indirect interest: this article and his book The Land of the Solstices: myth, geography & astronomy in ancient Greece. Bilić is an ethnoastronomer but he explores how different Greek traditions (Delphian, Athenian, Delian etc.) deal with Apollo and/or Helios through the link between astronomy and cult.

My personal opinion aligns more with what K. Rea brings up. I think that, if the syncretism between Helios and Apollo originates from the Athenian tradition or similar, it would have very easily spread through the centuries, but especially during the "Golden Age" of Athenian colonialism (the famous pentecontaetia). From there, it is easy to imagine how it could have spread to more territories through the Macedonian conquests etc. And then there's the case of Rhodes, which, as far as I know, had a very distinct Helian cult that doesn't seem to have been strongly infiltrated by Apollo. Whether Rhodes is an exception to the rule or evidence that the sync was originally a local tradition that gained popularity until becoming the norm is something I honestly cannot form a convincing opinion on.

This said, I hope the references above help you for your essay, and good luck!

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

(JTA) — This past week we entered the Hebrew month of Kislev, the month here in the Northern Hemisphere when we often experience the longest, darkest nights of the year. As the light contracts each day, I experience a tightening in my gut, an anxious fluttering of the heart. Time feels compressed, as if there aren’t enough hours in a day to do everything that needs doing. When the light fades at the end of these foreshortened days, I draw the blinds and turn on the lamps, wanting to make my home into an island of warmth and light in the face of the encroaching darkness.

My trepidation at the onset of night echoes the primal fear of the dark ascribed to the first mythic humans, Adam and Eve. A talmudic tale, found in Avodah Zarah 8a, imagines the two of them becoming frantic as darkness falls at the close of the first day of their lives. They’ve disobeyed God by eating from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil and now they’re terror stricken. “Woe is me,” Adam wails, “that because I’ve sinned, the world is darkening around me! The world will return to chaos and emptiness; this is heaven’s death sentence upon me!”

In this midrash, Adam experiences the arrival of darkness as punishment. His words conjure up the kind of existential shudder that can overtake a person in the dark, as the familiar shapes and colors of the daytime world dissolve into the trackless night. No wonder that darkness is often a metaphor for the scariest of times, times like the present, when awash in grief, fear and anger, we bear witness to the atrocities of war, to hatred unleashed and suffering magnified, to shattered dreams and dampened hopes. “These are dark times,” we tell one another.

Perhaps it’s only natural that humans try to beat back the dark with our hearths, campfires and brilliant winter light displays. We Jews do this beginning on the 25th of Kislev, when we kindle Hanukkah candles in remembrance of the Hasmoneans’ military victory over the Seleucid Greeks and the rededication of the Jerusalem Temple. But on a more primal level, we do this to remind ourselves that even a tiny flame instantly dispels the deepest dark, offering hope, a light at the end of the tunnel.

And yet it strikes me that many of our tradition’s most transformational and transcendent moments unfold in the dark, in a dream space rich with spiritual potency. In Toldot, this week’s Torah portion, for instance, we meet Jacob, whose journey toward self-realization is bookended by two stirring night episodes. Fleeing from his wrathful brother, he has a prophetic dream in which angels ascend and descend a ladder stretching between heaven and earth while God looms over him, promising protection. Returning home some 20 years later, he engages in an all-night wrestling match with a mysterious being, perhaps his own shadow self, who ultimately blesses him as the dawn breaks, renaming him Israel, the one who strives with God and prevails.

Despite the anguish that darkness evokes, the dark times offer unique opportunities. They slow us down, inviting us to rest in the moment. Sometimes they force us to face painful truths. They challenge us to deepen our prayer life, strengthen our faith and resolve, and discover inner resources and possibilities for transformation we might not know we possess.

Years ago, I practiced walking in the woods at night without a flashlight and discovered that when I could breathe deeply and relax into the darkness, over time my eyes would adjust and I could see much more than I thought possible. Not just my eyes, but my whole body began to see in the dark in ways that I couldn’t in the light of day. I could find my way.

Adam and Eve, so the story goes, sat across from one another on that first traumatic night, fasting and weeping. When the dawn finally broke, they realized that the freshly created world was not coming to an end and that the alternation of light and dark, day and night, was simply the way of the world. Had they not felt so guilty and terrified they might have been able to look around with curiosity as the light waned, noticing how their eyes were primed to pick up many subtle shades of gray, the palette of darkness. Their vision might have gradually adjusted to the dark and, in the subtle glow of starlight, they might have been able to pick out the familiar, reassuring features of the other’s face and been calmed and comforted, even in the midst of their distress.

Could it be that in our yearning for the resurgence of the light, we fail to recognize and fully receive the gifts of darkness? That in drawing my blinds against the terrors of the night, I also shut out the vastness of the cosmos, the glimmering pinpoints of distant stars, the radiant winter moon, and the intimate, enveloping quiet of the dark?

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"BMCR 2009.10.48

Ancient Greece and Ancient Iran: Cross-Cultural Encounters. 1st International Conference (Athens, 11-13 November 2006)

Seyed Mohammad Reza Darbandi, Antigoni Zournatzi, Ancient Greece and Ancient Iran: Cross-Cultural Encounters. 1st International Conference (Athens, 11-13 November 2006). Athens: National Hellenic Research Foundation; Hellenic National Commission for UNESCO; Cultural Center of the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2008. xxix, 377. ISBN 9789609309554. €60.00 (pb).

Review by

Margaret C. Miller, University of Sydney. [email protected]

[Authors and titles are listed at the end of the review.]

The volume commemorates a landmark occasion, when the national research centres of Iran and Greece collaborated in a multi-national interdisciplinary conference on the history of exchange between Iran and Greece. Its nearly 400 pages reflect a strong sense of its symbolic importance. Papers span the Achaemenid through the Mediaeval periods and address the theme of exchange from the perspective of many disciplines — history, art, religion, philosophy, literature, archaeology. The book thus brings together material that can be obscure outside the circle of specialists, and in a manner that is generally accessible; the wide range of topics and periods included is a strength. Excellent illustrations often in colour enhance the archaeological contributions, as does inclusion of hitherto unpublished material.

The volume commences with a brief section on what might be called Greek textual evidence (Tracy, Petropoulou, Tsanstanoglou), followed by papers on interaction in Sasanian through mediaeval Persia (Azarnoush, Alinia, Venetis, Fowden), four papers discussing Achaemenid, Seleucid and Parthian history (Weiskopf, Ivantchik, Tuplin, Aperghis), aspects of the archaeology of Persepolis and Pasargadae (Stronach, Talebian, Root, Palagia), and ends with essays on the receptivity to Achaemenid culture in the material culture of the western empire and fringes: Cyprus, Turkey, Greece (Zournatzi, Lintz, Summerer, Paspalas, Ignatiadou, Sideris, Triantafyllidis), followed by a paper on traces of Greek material culture in the archaeology of (Seleucid) Iran (Rahbar). The wealth of vehicles, contexts and levels of exchange attested through the ages is both eye-opening and exciting. While there is unfortunately little attempt at globalizing synthesis or theoretical modelling, the analytical methods and collections of data in the individual contributions will aid future work in the area.

Stephen Tracy starts the volume with a synchronic analysis of the ways in which first Aeschylus, then Homer, play upon the prejudices of their audience against ” barbaroi” and then show the human quality of the enemy. In Persai, the Athenians are anonymous in contrast with the delineated personalities of the Persian royal family; in the Iliad, Achilles is “not very likeable” but learns humanity from the sorrow of Priam. Both poets focus on common humanity that transcends short-term hostilities.

Angeliki Petropoulou offers a detailed analysis of Herodotus’ account of the death of Masistios and subsequent mourning (Hdt. 9.20-25.1). Herodotus played up the heroic quality of Masistios’ death, stressing his beauty and height, qualities appreciated by both Greeks and Persians. The fact that Masistios seems to have gained the position of cavalry commander in the year before his death, coupled with the likelihood that his Nisaian horse with its golden bridle was a royal gift, suggests he had been promoted and rewarded for bravery.

Kyriakos Tsantsanoglou discusses the Derveni papyrus’ mention of magoi (column VI.1-14). Though the papyrus dates 340-320, the text was composed late fifth century BC, making the apparently Iranian content especially important. Both the ritual described and the explanation for it cohere with elements known from later Persian sources as features of early Iranian religious thought. While the precise vehicles of transmission of such knowledge to the papyrus are unknowable, the papyrus is the first certain documentation of the borrowing of Iranian ideas in Greek (philosophical) thought.

On the Iranian side exchange of religious ideas is documented by Massoud Azarnoush in the iconography of a fourth-century AD Sasanian manor-house he excavated at Hajiabad 1979.1 Moulded stucco in the form of divine figures included dressed and naked females identified with Anahita. The very broad shoulders of the Hellenistically dressed Anahita fit an Iranian aesthetic; the closest parallel for the slender naked females is found not in the cognate Ishtar type but in the Aphrodite Pudica type. Reliefs of naked boys, of uncertain relationship with Anahita, have attributes of fertility cult in the (Dionysian?) bunches of grapes they hold and in the ?ivy elements of their headdress.

Sara Alinia offers a brief but fascinating account of the development of state-sponsored religion hand-in-hand with state-sponsored persecution of religious elements that were deemed to be affiliated with another state: the Christian Late Roman Empire and the Zoroastrian Sasanian Empire. She documents the rise of religion as a tool of inter-state diplomacy and vehicle for inter-state rivalry; religion was but one facet of the political antagonism between the two.

Evangelos Venetis studies the cross-fertilization between Hellenistic and Byzantine Greek romance and Iranian pre-Islamic and Islamic romantic narrative. Persian elements are found in Hellenistic romance; Hellenistic themes contribute to Persian epics. The fragmentary nature of texts ranging 2nd -11th/14th c. AD and the lack of intermediary texts are serious impediments which may yet be overcome. The Alexander Romance, known in Iran from a Sasanian translation, contributed to the form and detail of the Shahname, as well as to other Persian epics.

Garth Fowden outlines the complex history of the creation, translation, wide circulation and impact of the pseudo-Aristotelian texts on religious thought. Aristotle’s works were translated into Syriac in the 6th c. and in the mid 8th c. into Arabic. Arab philosophers, attracted to the idea of Aristotle as counsellor of kings, updated him. Owing to his remoteness in time, “Aristotle” offended neither Muslim nor Christian. The Letters of Alexander, Secret of Secrets and al-Kindi’s sequel of Metaphysics, the Theology of Aristotle, contributed significantly to the philosophical underpinnings of both Muslim and Christian theology; the last remains an important text in teaching at Qom.

Michael N. Weiskopf argues that Herodotos’ account of the Persian treatment of Ionia after the Ionian revolt constitutes “imperial nostalgia” — the popular memory of how good things were under a past regime, in the context of a new regime. Herodotos 6.42-43, stressing the administrative efficiency and fairness of Artaphernes’ arrangements, allows a reading of Mardonios’ alleged imposition of democratic constitutions (so dissonant with the subsequent reported governing of Ionian states) as imperial nostalgia, to be contrasted with the inconsistent and unfair treatment of the Ionians by the Athenians of Herodotos’ own day.

Askold I. Ivantchik publishes two Greek inscriptions from Hellenistic Tanais in the Bosporos (and reedits a third). Evidently private thiasos inscriptions, they confirm that the city was already in 2nd or 1st century BC officially divided into two social (presumably ethnic) groups: the Hellenes and the Tanaitai, presumably Sarmatians, on whose land the city was founded in the late 3rd century BC. A thiasos for the river god Tanais includes members with both Greek and Iranian names, showing that private religious thiasoi were an important vehicle for breaking down social barriers between the two populations of the city.

Two papers offer contrasting interpretations of the evidence for Seleucid retention of Achaemenid institutions. That there were parallels between structures of the different periods is uncontested; the question is whether the parallels signify a deliberate programme of Seleucid self-presentation as the “heirs of the Achaemenids.” Christopher R. Tuplin argues that acquisition of the empire involved adoption of the Achaemenid mantle in some contexts and maintenance of those structures that worked, but that the balance of evidence suggests no conscious policy of continuation, and considerable de facto alteration of attitude and form. He suggests that the evidence of continuity of financial (taxation) structures — a major part of Aperghis’ argument — is ambiguous, at best. The treatment and divisions of territory, most notably the “shift of centre of gravity” from Persis to Babylonia, argue more for disruption than continuity.

G. G. Aperghis gives the case for a deliberate Seleucid policy of continuation of many Achaemenid administrative practices. He points to the retention of the satrapy as basis of administrative organization; use of land-grants (albeit to cities rather than individuals); continuing royal support of temples; maintenance of the Royal Road system (n.b. two Greek milestones, one illustrated in this volume by Rahbar); the retention of two separate offices relating to financial oversight. He suggests that the double sealing of transactions in the Persepolis Fortification Tablets metamorphosed into the double monogram on Seleucid coinage. Further field work in Iran, like that outlined by Rahbar (see below), will settle such contested matters as whether the many foundations of Alexander had any local impact. At present, Tuplin offers the more persuasive case.

David Stronach, excavator of Pasargadae, gives his considered opinion on the complex nexus of issues relating to the date of Cyrus’ constructions at Pasargadae. Touching upon the East Greek and Lydian contribution to early Achaemenid monumental architecture in stone and orthogonal design principles, Cyrus’ conquest chronology and the Nabonidus Chronicle, Darius’ creation of Old Persian cuneiform, the elements of the Tomb of Cyrus, and new evidence confirming the garden design, he argues that the chronology of the constructions at Pasargadae indirectly confirms the date of the conquest of Lydia around 545.

Mohammad Hassan Talebian offers a diachronic analysis of Persepolis and Pasargadae, starting with a survey of the Iranian and Lydian elements in their construction. Modern interventions include the ill-informed and damaging activities of Herzfeld and Schmidt at Persepolis in the 1930s, the stripping away of the mediaeval Islamic development of the Tomb of Cyrus, and the damage to the ancient city of Persepolis in preparation for the 2500-anniversary celebrations in 1971. Recent surveys in the region compensate to some degree. Talebian urges the importance of attention to all periods of the past rather than a privileged few.

Margaret Cool Root continues her thought-experiment in exploring how a fifth-century Athenian male might have viewed Persepolis.2 Sculptural traits such as the emphasis on the clothed body and nature of interaction between individuals would have seemed to the hypothetical Athenian to embody a profoundly effeminate culture. Yet Root’s study of the Persepolis Fortification Tablet sealings, their flashes of humour and playfulness in their utilisation on the tablets, reveals a world in which oral communication — idle chit-chat — perhaps bridged the cultural divide. She concludes that a visiting Greek might well have learned how to read the imagery like an Iranian.

Olga Palagia argues that the most famous Greek artefact found at Persepolis, the marble statue of “Penelope”, was not booty but a diplomatic gift from the people of Thasos: its Thasian marble provides a workshop provenance. The “Polygnotan” character, seen also in the Thasian marble “Boston Throne,” possibly from the same workshop, suits the prestige of the gift: Thasos’ great artist, the painter Polygnotos, is also attested as a bronze sculptor. A putative second Penelope in Thasos, taken to Rome in the imperial period with the “Boston Throne,” would have served as model for the Roman sculptural versions.

Antigoni Zournatzi offers the first of a series of regional studies documenting receptivity to Persian culture in the western empire and beyond, with a look at Cyprus. Earlier scholarship focused on siege mound and palace design; receptivity can be tracked in glyptic, toreutic, and sculpture. Western “Achaemenidizing” seals may be Cypriote; Persianizing statuettes may reflect local adoption of Persian dress (or Persian participation in local ritual). The treatment of beard curls on one late 6th century head may reflect Persian sculptural practice. Zournatzi suggests that Cypro-Persian bowls and jewellery were produced not for local consumption but to satisfy tribute requirements.

Yannick Lintz announces a project to compile a comprehensive corpus of Achaemenid objects in western Turkey, an essential step in any attempt to understand the period in the region.3 Particular challenges lie in matters of definition, both of “Achaemenid” and “west Anatolian” traits. The state of completion of the database is not clear; one is aware of a volume of excavated material in museums whose processing and publication was interrupted and can only wish her well in what promises to be a massive undertaking.

Lâtife Summerer continues her publication of the Persian-period Phrygian painted wooden tomb at Tatarli in western Turkey with discussion of the different cultural elements of its iconographic programme.4 The friezes of the north wall especially present Anatolian traditions; the east wall friezes of funerary procession and battle (between Persians and nomads) offer a mix of Persian and Anatolian. New Hittite evidence clinches as Anatolian the identification of the cart with curved top familiar in Anatolo-Persian art; it carries an effigy of the deceased. Alexander von Kienlin’s appendix expands the cultural mix presented by the tomb with his demonstration that its Lydian-style dromos was an original feature.

Stavros Paspalas raises questions about the vehicles and route of cultural exchange between the Persian Empire and Macedon through analysis of Achaemenid-looking lion-griffins on the façade of the later fourth century tomb at Aghios Athanasios. He identifies a pattern of specifically Macedonian patronage of Achaemenid imagery also in southern Greece in the fourth century in such items as the pebble mosaic from Sikyon and the Kamini stele from Athens. Enough survives to suggest independent local Macedonian receptivity to Persian ideas rather than a secondary derivation through southern Greece.

Despina Ignatiadou summarises succinctly the growing corpus of Achaemenidizing glass and metalware vessels in 6th-4th century BC Macedon. Three foreign plants lie behind the forms of lobe and petal-decoration on phialai, bowls, jugs, and beakers: the central Anatolian opium poppy, the Egyptian lotus (white and blue types) and the Iranian/Anatolian (bitter) almond. The common denominator is their medicinal and psychotropic qualities; Ignatiadou suggests that their appearance on vessels has semiotic value and that such drugs were used in religious and ritual contexts along with the vessels that carry their signatures, perhaps especially in the worship of the Great Mother.

Athanasios Sideris outlines the range of issues related to understanding the role of Achaemenid toreutic in documenting ancient cultural exchange: production ranges between court, regional, and extra-imperial workshops, not readily distinguishable. The inclusion of little-known material from Delphi and Dodona enriches his discussion of shape types. He works toward identification of local workshops, both within and without the empire, based especially on apparent local preferences in surface treatment. The geographical range of production is one area that will benefit from further international research collaboration.5

Pavlos Triantafyllidis focuses on the wealth of material from Rhodes, both sanctuary deposits and well-dated burials, that attests a history of imports from Iran and the Caucasus even before the Achaemenid period. Achaemenid-style glass vessels start in the late 6th century with an alabastron and petalled bowl, paralleled in the western empire, and carry on through the fourth century. An excavated fourth-century glass workshop created a series of “Rhodio-Achaemenid” products that dominated Rhodian glassware through the early third century. This microcosmic case study brilliantly exemplifies a much broader phenomenon.

Mehdi Rahbar outlines and illustrates archaeological material, some not previously published, that will be fundamental in future discussions of Seleucid Iran. The as of yet limited corpus includes: modulation of Greek forms perhaps to suit a local taste (Ionic capital from the temple of Laodicea, Nahavand, known from an 1843 inscription of Antiochus III; fragmentary marble sculpture of Marsyas?), amalgam of Iranian and Greek (milestone in Greek with Persepolitan profile), Greek import (Rhodian stamped amphora handle ΝΙΚΑΓΙΔΟΣ from Bisotun);6 and Iranian adoption of Greek decorative elements (vine leaves, grapes, and acanthus patterns, for which compare Azarnoush’s stucco).

The volume concludes with a brief overview of ancient Iranian-Greek relations and their modern interpretation by Shahrokh Razmjou.

The inclusion of the texts of the introductory and concluding addresses made on the occasion of the conference in particular allow the reader to comprehend its aims: hopes of exchange in the modern world through assessing exchange in the past. A number of the papers make it very clear that collaboration between specialists of “East” and “West” in both textual and archaeological research could yield great gains for all periods of history and modes of analysis. The conference and its publication, therefore, succeed at a variety of levels.

Editing such a volume must have been a real challenge and it is to the credit of authors and editors that throughout the whole volume, I found only a handful of minor infelicities and typographical errors, none of which obscure meaning.7

Contents: Stephen Tracy, “Europe and Asia: Aeschylus’ Persians and Homer’s Iliad” (1-8) Angeliki Petropoulou, “The Death of Masistios and the Mourning for his Loss” (9-30) Kyriakos Tsantsanoglou, “Magi in Athens in the Fifth Century BC?” (31-39) Massoud Azarnoush, “Hajiabad and the Dialogue of Civilizations” (41-52) Sara Alinia, “Zoroastrianism and Christianity in the Sasanian Empire (Fourth Century AD)” (53-58) Evangelos Venetis, “Greco-Persian Literary Interactions in Classical Persian Literature” (59-63) Garth Fowden, “Pseudo-Aristotelian Politics and Theology in Universal Islam” (65-81) Michael N. Weiskopf, “The System Artaphernes-Mardonius as an Example of Imperial Nostalgia” (83-91) Askold I. Ivantchik, “Greeks and Iranians in the Cimmerian Bosporus in the Second/First Century BC: New Epigraphic Data from Tanais” (93-107) Christopher Tuplin, “The Seleucids and Their Achaemenid Predecessors: A Persian Inheritance?” (109-136) G. G. Aperghis, “Managing an Empire—Teacher and Pupil” (137-147) David Stronach, “The Building Program of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae and the Date of the Fall of Sardis” (149-173) Mohammad Hassan Talebian, “Persia and Greece: The Role of Cultural Interactions in the Architecture of Persepolis-Pasargadae” (175-193) Margaret Cool Root, “Reading Persepolis in Greek—Part Two: Marriage Metaphors and Unmanly Virtues” (195-221) Olga Palagia, “The Marble of the Penelope from Persepolis and its Historical Implications” (223-237) Antigoni Zournatzi, “Cultural Interconnections in the Achaemenid West: A Few Reflections on the Testimony of the Cypriot Archaeological Record” (239-255) Yannick Lintz, “Greek, Anatolian, and Persian Iconography in Asia Minor : Material Sources, Method, and Perspectives” (257-263) Latife Summerer, “Imaging a Tomb Chamber : The Iconographic Program of the Tatarli Wall Paintings” (265-299) Stavros Paspalas, “The Achaemenid Lion-Griffin on a Macedonian Tomb Painting and on a Sicyonian Mosaic” (301-325) Despina Ignatiadou, “Psychotropic Plants on Achaemenid Style Vessels” (327-337) Athanasios Sideris, “Achaemenid Toreutics in the Greek Periphery” (339-353) Pavlos Triantafyllidis, “Achaemenid Influences on Rhodian Minor Arts and Crafts” (355-366) Mehdi Rahbar, “Historical Iranian and Greek Relations in Retrospect” (367-372) Shahrokh Razmjou, “Persia and Greece: A Forgotten History of Cultural Relations” (373-374)

Notes

1. The site is fully published in: M. Azarnoush, The Sasanian manor house at Hajiabad, Iran (Florence 1994).

2. The first appears as “Reading Persepolis in Greek: gifts of the Yauna,” in C. Tuplin, ed., Persian Responses: Political and Cultural Interaction with(in) the Achaemenid Empire (Swansea 2007) 163-203.

3. Deniz Kaptan is similarly compiling a corpus of Achaemenid seals and sealings in Turkish museums.

4. Other studies: “From Tatari to Munich. The recovery of a painted wooden tomb chamber in Phrygia”, in I. Delemen, ed., The Achaemenid Impact on Local Populations and Cultures (Istanbul 2007), 129-56; “Picturing Persian Victory: The Painted Battle Scene on the Munich Wood”, in A. Ivantchik and Vakhtang Licheli, edd., Achaemenid Culture and Local Traditions in Anatolia, Southern Caucasus and Iran: New Discoveries (Leiden/Boston 2007: Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia 13), 3-30.

5. Considerable progress is being made, e.g., in Georgia: V. Licheli, “Oriental Innovations in Samtskhe (Southern Georgia) in the 1st Millennium BC,” and M. Yu. Treister, “The Toreutics of Colchis in the 5th-4th Centuries B.C. Local Traditions, Outside Influences, Innovations,” both Ivantchik / Licheli, edd., Achaemenid Culture and Local Traditions in Anatolia (previous note), 55-66 and 67-107.

6. For early 2nd c. date of this fabricant, see Christoph Börker and J. Burow, Die hellenistischen Amphorenstempel aus Pergamon: Der Pergamon-Komplex; Die Übrigen Stempel aus Pergamon (Berlin 1998), cat. no. 274-286; one example has a context of ca. 200 BC.

7. Except possibly the misprint on p. 357, line 8 up, where “second century” should presumably be “second quarter” (of the fourth century)."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To begin with, let me stress that the recent evidence indicates that Philometor’s permitting the settlement of (Jewish) mercenaries (including their role in the military and administration) and the erection of a (Jewish) temple, is not a singular case; it was by no means exceptional.⁵⁶ In fact, we encounter several other ethnic minorities in Ptolemaic Egypt around that time, which, like the Jews, were actively involved in the defense and administrative apparatus of the Ptolemies. So, for instance, we hear of Samaritans and Idumeans serving the Ptolemies.⁵⁷ More strikingly, however, and in addition to these affairs, our evidence also shows that the leaders of those minorities were referred to as high priests – much as Onias had been.⁵⁸ [...]

The recent studies referred to above are concerned with the involvement and relationship between the Ptolemaic military, Greek soldiers and Egyptian temples.⁶⁰ These studies have treated the phenomenon of an increased involvement of Ptolemaic military personnel – mostly of Greek and not native Egyptian origin – in the building or reconstruction of Egyptian temples. Oftentimes, we find that the Egyptian temples were overseen by Greek officers, who also served as high priests of those places of worship. In juxtaposition with their religious title/office, they also held important military positions such as strategos or commanders of a fortress (phrouarch).⁶¹ Dietze and Gorre’s studies reveal that Egyptian temples, usually the local center of a certain region, often served as fortresses too, and were deliberately erected for strategic domestic and foreign purposes, especially in the later Ptolemaic period, and specifically under Ptolemy VI Philometor.⁶² Dietze, in particular, has suggested that an Egyptian temple commonly housed a garrison and that the temple structures reflected their defensive purposes also in their architecture.⁶³ In addition, she has provided many examples of Egyptian temples which were built (or refurbished) during Philometor’s reign or shortly thereafter, and which were primarily located and erected in the southern part of Egypt.⁶⁴ The reason for this was Philometor’s (successful) attempts at calming the region following the persistent and irking civil uprisings which plagued the south of Egypt during his early reign. Calming the region was achieved by enforcing Ptolemaic military presence which also meant that more conscripts were needed to man those newly established garrisons. It seems that the Ptolemaic authorities championed the solution of placing military units in temples, by means of which they could bind the local inhabitants to the Ptolemaic state and its rulers through their religious practice. Pairing the security issues with religious matters greatly contributed to forestalling potential future outbursts of violence against the Greek ruling-class of Egypt. Along with those domestic concerns, this strategy also proved itself effective against possible external threats (as illustrated in the example of the south against spontaneous attacks of local Nubian warlords and tribes).⁶⁵ [...]

Viewed from a Ptolemaic perspective, we may once more turn to the Josephan reports on the building of the Oniad Temple and interpret them from a different angle.We recall that Philometor’s reign was plagued by two major security threats already mentioned, namely civil uprisings of the native Egyptian population in the south, and the second, perhaps more serious external threat of a Seleucid invasion from the north (which in fact materialized twice in 169/168 and 168/167 BCE). As I and others have often pointed out, Onias’ flight to Egypt around the time of Antiochus’ IV invasion of Egypt (i.e. in ca. 168/167 BCE) came exactly at the right moment for Philometor. Thus, Onias’ request to build his temple can perhaps be better understood in a Ptolemaic, rather than in a purely Jewish context. That is, the Ptolemaic perspective may explain some minor, yet important, details in the story Josephus relates on the erection of Onias’ Temple (and royal permission to erect it), which perhaps have hitherto been misunderstood.

As such, Josephus tells us in his longer account of Onias’ Temple in his Antiquities – in a much debated and controversial passage – that Onias asked for a specific territory for his temple project. Here we also learn that he erected his temple on the site of an abandoned and apparently damaged Egyptian one.⁶⁶ Seen from a Jewish halakhic perspective, such conduct would render Onias’ Temple impure, which is exactly the point bemoaned by Josephus. We may add that Onias’ actions must have been scorned not only by Josephus, but by other (Jews) too. However, if we set this narrative against the recent evidence from the Ptolemaic papyri and inscriptions, it seems that the refurbishing of pagan native Egyptian shrines and their re-settlement with foreign soldiers had been standard Ptolemaic practice.

It follows that Josephus’ ‘Epistolary Piece’ in fact attests to this specific Ptolemaic policy, but interprets it against the backdrop of Jewish halakhah. The aim was to portray Onias as an impious character, as I have illustrated in Chapter 1. Thus, Onias was given a specific territory by the Ptolemaic king – although he indeed seems to have had a word, as claimed by Josephus, on where exactly to establish his community – which contained a deserted or destroyed Egyptian temple, namely that of Bubastis.⁶⁷ Of course, he must have rejected the idea of actually reestablishing a foreign cult place. This fact emerges from his request to (re‐)build the former temple of Bubastis to make it fit for the worship of Onias’ domestic deity, the Jewish God.⁶⁸

This specific Ptolemaic defense policy may be considered as well to explain Josephus’ datum that Onias, next to his temple, had built “a fortress.”⁶⁹ Our evidence from comparable cases studied by Dietze suggests that temples simultaneously functioned as fortresses, and vice versa.⁷⁰ In that context, it should be noted that Josephus elsewhere writes (BJ 1.31) that Onias also founded (ἔκτισεν) a city which resembled Jerusalem. It is notable that Josephus only once mentions that fact, whereas the resemblance of Oniad edifices to Jerusalem (or the lack thereof – see BJ 7 .427) is noted by him once more in the context of the altar or the Oniad Temple.⁷¹ Josephus’ claim that Onias founded a city is a remarkable detail worth discussing, since, in a Ptolemaic context, the foundation of a city was a restricted act, usually reserved for the king only.⁷² However, recent papyrological and epigraphical evidence reveals that this rule did not necessarily apply generally. "

Pages 340-344 of Priests in Exile by Meron M Piotrkowski

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Well, the one part of the question I didn't answer yet is what isn't part of the Tanach. Which, while it's a group that contains a lot of books (Harry Potter and the Lord of the Rings aren't part of the Tanach, for example), we can still have a look at some books that potentially could enter but didn't. In addition, explaining why the Talmud isn't a part of the Tanach might also be helpful. So let us start talking about the codification and canonization of the Tanach!

Now, the codification of the Tanach, as in organizing the books that would enter and perhaps editing some of them, was a work done by Knesset HaGdolah - the Great Assembly of 120 Jewish rabbis and leaders that formed at the start of the 2nd Temple era, around 516 BCE (according to historians. There are some disagreement between them and traditional Jewish chronicles around this particular time frame). No decisive date can be put to the end of it, though. Some books that ended up in the Tanach were written around the early days of the Great Assembly - Ezra, for example - and the finalization of codifying and canonizing the Tanach likely happened some time after the books in it were written. It's likely that by the time Alexander the Great conquered the Land of Israel - around 332 BCE - there was a loose canon of texts, though I can't really say for certain. I would like to note, for example, that I've heard from Rav Aviah HaCohen that the book of Daniel contains words of Greek origin, indicating it has some degree of Hellenistic influence and thus was likely written when they controlled the land. From the perspective of a non-believer it also makes all the prophecies about the wars between the North and South kings more obviously about the Ptolemies and Seleucids. If it truly was written that late, it might well be the latest-written book of the Tanach.

Either way, there are evidence that by the time of the destruction of the 2nd Temple, the canon of the Tanach as we know it existed. It does not mean that it was undisputed - within the Pharisees, the 2nd Temple sect that gave rise to Rabbinic Judaism as we know it, there were still some disagreements about books that should be kept. Other sects (such as the Qumranites) wanted to add books, while yet others didn't accept the Tanach at all - the Samaritans still only consider the Torah as scripture, to this day. However, the Pharisees became the mainstream and thus based the canon.

So first, what disagreements were among the Pharisees? Well, for the most part, there were two books in dispute: Kohellet and Shir HaShirim. Now, there's also a disagreement regarding on which of them there was a dispute in the first place, which can get a little confusing. We'll just avoid that point for now and note that the problem with Kohellet was that it contradicted itself multiple times, and Shir HaShirim... well, it's kind of a romantic-erotic love song that doesn't exactly seem like it belongs in scripture, if we're being honest. However, both have stayed in canon - the Sages have explained the contradictions in Kohellet and Rabbi Akiva would have my head for suggesting the love song (commonly seen as a parable for G-d's love to the Israelites) doesn't belong in scripture. So that is that.

Now, another question that needs to be answered is what books could have entered, but didn't? There are many books that fit that title even if we only discuss Jewish religious books from that period (that aren't disqualified for reasons similar to the Talmud, elaboration on that later). To make things easier for me, I'm going to limit myself to talking about three particular books: the Book of Enoch, Ben Sirach and Maccabees. I could (and possibly should) stop here and not try explaining why they didn't enter the Tanach. However, if I had done that I could've just looked up a list of the Apocryphal book and paste it here. So, I'll attempt to get into the why. (In case you're wondering what apocryphal means, it appears the literal translation of the word is somewhere along the lines of dubious or inauthentic. In Hebrew those books are called Sefarim Ḥitzoniyim, meaning "outer books". Essentially - books that aren't a part of the Tanach's canon.)

The most problematic of these three is Ben Sirach. And I mean "problematic" in the sense it seems to have gotten the closest to entering. Ben Sirach is a book of proverbs and saying by a Jewish scholar, I think from Alexandria? Who wrote them around the time of the 2nd Temple. And this book is quoted in the Talmud a few times, with at least once that it's seemingly referred to as if it's a part of scripture. On the other hand, in the tractate of Sanhedrin (100B) Rav Yosef includes it among the books that reading in leads to exemption from having an afterlife. The weird part is that even he himself quotes from it a couple of lines later.

Well, a common explanation I've seen of that is that Rav Yosef there - as well as the Mishnah he comments on, which talks about Sefarim Ḥitzoniyim in general - don't actually mean one shouldn't read those at all. They merely mean that one shouldn't read it in the same way one reads scripture, and should remember it's not scripture. The reason Rashi gives to what the problem is with Ben Sirach is that it has some nonsensical or empty sayings (it's a little hard to translate, maybe it would be more accurate to say some of its sayings are rubbbish).

The Book of Enoch is an intersting one. It talks about the hierarchy of angels and the proper order of the world, from what I understand, and much of the lore in it is accepted as canon by both Christians and Jews (I think, though I didn't read the book). However, only one existing group in the world has it in their canonical Bible and those are Ethipean Christians. Well, I might be wrong - it could be that the Assyrian church also has it, as while modern editions lean heavily on the Ethipean version they still have other sources to lean on. Either way, this book - likely written during the Hellenistic period in the Land of Israel - is not a part of the canon of the Tanach. Why? I don't really know. Maybe the attribution of the book to such an old figure didn't sit well with the rabbis working on the canonization. Maybe they didn't believe it was written with any divine inspiration. Maybe it was written too late into the Hellenistic period, at a time when the canon was already set. Either way, it didn't get in, leaving Daniel as the only book in the Tanach that gives angels names.

Now, regarding the Book of Maccabees: there are actually four of them. I really don't want to get into all of them, so I'm going to focus on the first - which was likely written the closest to the actual Hasmonean rebellion, by someone who may have participated in it, and in Hebrew. And it still didn't get into the Tanach, though it gives much-needed context to the holiday of Hannukah. Why is that? Well, the most likely answer is that it wasn't written with divine inspiration. It's not something easily provable, and for a non-believer it's not going to mean much, so to rephrase - the people who canonized the Tanach didn't think it was divinely inspired. It just seemed like a chronicle of a war that was written after the prophecy was gone from among the Jews. Without prophecy, this book wasn't deemed a legitimate addition to canon and thus remained outside.

There are quite a few more books that didn't enter but you may have heard of - the book of Judith, the book of Jubilees, and many others. I have written a list in the first post of all the books in the Tanach - if it's not one of those, it's not inside. Usually under the assumption it wasn't written with Divine inspiration.

So, what about the Talmud? I am aware that you didn't ask this question. The Talmud is known to not be a part of the Tanach. But why is that? If it's a Jewish religious book, shouldn't it be included in the collection of our scripture? Well, to explain that we need to explain about the Oral Torah. This post is long enough as it is, however, so I'll try to keep it brief.

Basically, Orthodox tradition has it that Moshe got two Torahs on mount Sinai: one Written and one Oral, with the Oral one explaining the Written one and getting into the finer details of the law. Conservative Jews consider the Oral Torah to be a later addition by the Great Assembly, I think - if a Conservative JEw in the audience knows otherwise please do correct me. Its role doesn't change, however: it's always to explain the Written Torah, add some prohibitions to help avoid doing anything forbidden, and such things. The Oral Torah was codified into the Mishnah by Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi around the 2nd century CE, including in it various discussions and disagreements on details of the law. A couple of centuries later, a series of discussions and interpretations on the Mishnah were codified in the Talmud. In addition to these two books, the various Midrashim can probably also be considered a part of the Oral Torah.

You might notice I used the word "codify" and not "write". Even if you didn't, well, you should know that there's a reason for that: the Oral Torah truly is Oral, or at least was. It's very different in nature and purpose from the Written Torah and the Tanach. And that is why the Talmud isn't a part of the Tanach - because it's a part of the complex collection of interpretations on it.

I hope this was helpful! Thank you for asking (and for reading that), and have a good day! If you had trouble understanding something I wrote here, please don't hesitate to ask!

Secular jew here with a really stupid question about the tanach

What exactly constitutes the tanach? I think I've heard it's an acronym, so would the Torah be the t? what's the rest of the acronym? Which writings does it include? I'm pretty sure the talmud isn't part of it, what else isn't? Apologies if this is too basic of a question for you!

Hello! Thank you for the question!

The Torah indeed is the first part of the Tanach. Tanach is an acronym for the Hebrew words Torah, Nevi'im and Ketuvim. Roughly translated, those titles mean "Instructions", "Prophets" and "Writings", respectively. The Tanach, then, consists of 24 books divided into those three categories.

The Torah is the easiest one to define: it's the Pentateuch, the Five Books of Moses, however else you choose to call them, and they are generally known to be set apart. The books in it are Bereshit (Genesis), Shemot (Exodus), Vayikra (Leviticus), B'midbar (Numbers) and Devarim (Deuteronomy). Those are the books traditionally given to Moshe directly by G-d, and mostly focus on the formation of the Israelite people and its time under his leadership. It also includes all the commandments, basically.

Nevi'im are supposedly the books written by prophets, and half the books there are specifically books of prophecy (which is more messages from G-d than necessarily predicting the future). However, the first four books - Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings - are more historical in nature, chronicling the events from Moshe's death to the destruction of the 1st Temple. The last four books - Isaiah, Jeremaiah, Ezkiel and the Twelve prophets - are primarily books of prophecies and visions, with some stories sprinked in between. Most of them are concurrent with events in the book of Kings - except for the last three of the Twelve Prophets, who have lived around the building of the 2nd Temple. The Twelve Prophets are (by this order): Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Michah, Naḥum, Ḥabakuk, Zephaniah, Ḥaggai, Zacharias and Malachi. Names are written more or less in their traditional English spelling.