#rise of the empire

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

- Attack of the Clones, 2002

#star wars prequels#prequel era#rise of the empire#attack of the clones#obi-wan is the ''daddy'' in this case#as in an actual father-son relationship#read rogue planet and you'll know what i mean#obi wan is his dad#anidala#anakin and padme#this came to me while in class#not in a dream but it should have been#star wars#anakin skywalker#padme naberrie#padme amidala#padme skywalker

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

#star wars#attack of the clones#chancellor palpatine#bail organa#coruscant#fall of the republic#rise of the empire

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Force, if it had been willing to be more specific:

The end of the Jedi Order (which we knew until then), the Jedi genocide, the end of the Thousand Year Republic, the rise of the Empire, the end of "human rights", and the list goes on.

The Force: bad things are gonna happen

Jedi: ????? What bad things

The Force: watch out

#star wars#order 66#Jedi order#jedi#rise of the empire#star wars incorrect quotes#fight the empire#chancellor palpatine#galatic empire#star wars republic#star wars empire#star wars universe#the force#star wars quotes#star wars memes#star wars stuff

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Animated Morgan makes me question my sexuality……..in a am bisexual way…………

0 notes

Text

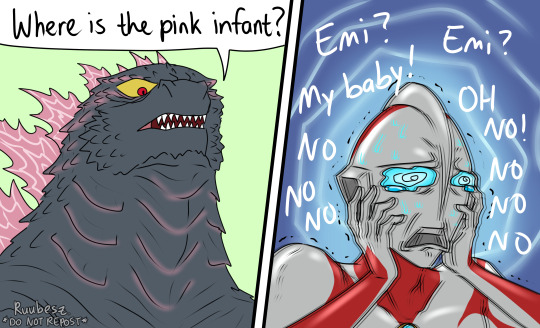

Showing off the babies

(I watched Ultraman Rising! It was good!)

Bonus:

From this

#godzilla#ultraman#godzilla x kong: the new empire#ultraman rising#godzilla minus one#netflix#kenji sato#emi ultraman#kong#suko#the bebes!#now my collection is complete#Finally#I have them all#the dads/big bro collection#also I watched Ultraman Rising#it was better than I expected!#loved the family bond and the story#Emi is a baby#she's a good baby#now what if I put her with Minus One....#hhhhhmmmmm#haha joking!#....#unless?#do not repost#my art

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok you know what, let's spread some positivity. Reblog this if you actually like Star Wars

And I am refering to all of star wars and not just select parts of it. Even if you have issues with parts of it, you still enjoy it.

#star wars#positivity#a new hope#the empire strikes back#return of the jedi#the phantom menace#attack of the clones#revenge of the sith#the clone wars#star wars rebels#the force awakens#rogue one#the last jedi#solo a star wars story#star wars resistance#the mandalorian#the rise of skywalker#the bad batch#star wars visions#the book of boba fett#obi wan series#andor series#tales of the jedi#ahsoka series#tales of the empire#the acolyte#star wars legends#star wars eu

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Literally every ninjago season in a nutshell 💀

Credit to original poster (not sure who)

#ninjago#ninjago rise of the snakes#ninjago legacy of the green ninja#ninjago rebooted#ninjago tournament of elements#ninjago possession#ninjago skybound#ninjago hands of time#ninjago sons of garmadon#ninjago hunted#ninjago march of the oni#ninjago secrets of the forbidden spinjitzu#ninjago prime empire#ninjago master of the mountain#ninjago the island#ninjago seabound#ninjago crystalized

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

'For one of the primary purposes of [the Clone Wars] was to brutalize the population of the galaxy... This war has to be more destructive, more chaotic, more disruptive, and more horrifying than they could have believed... Civilians had to die in huge numbers on besieged worlds. Property had to be destroyed. Economies had to collapse. Planets had to starve... Because when Palpatine was ready to bring about the end of the conflict, both populations had to be so desperate for that moment that they would gratefully embrace peace. They must be so grateful that they would not care about the price it came at or what was traded away to achieve it.'

- The Rise and Fall of the Galactic Empire, by Dr. Chris Kempshall

#star wars#star wars the clone wars#star wars lore#star wars prequels#star wars the rise and fall of the galactic empire#star wars politics

665 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm finally writing my star wars fic. I feel confident in doing so now that I've read 200 of the EU books (and annotated them). I didn't feel comfortable going off of only the few star wars books and comics I had read before doing my massive reading project because I wanted to make sure I do my ROTS fix-it right. I've pinpointed where I want to start to diverge from canon (because the Republic would have fallen whether Anakin fell to the dark side or not by the time ROTS is happening) and I think I'm going to set the fix it right before Yoda Dark Rendezvous, that way the threat of multiple worlds turning against the Jedi is still there BUT there is still enough political stability to reasonably take down Sidious. I know many people think that any changes have to begin before the battle of Geonosis to be able to take down Sidious, but I want Anakin's disability to still be there, so Anakin and Obi-wan need to still fight Dooku. I also Ahsoka because she is one of my favorite characters so it has to take place farther along into the clone wars. Despite Ahsoka being there, I will probably stick more closely to the 2003 clone wars specials as they're my favorite star wars animated media. This has been a year of prep for beginning writing this fic but I'm finally ready. Yes I reread several star wars books I had read previously just so I could annotate them for this fic. Yes I did the same for the comics. Yes all this star wars interaction gave me the urge to replay the old battlefront games and yes they were just as good as I remember them being when I was 5.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honestly, I don't think it even had to be the Jedi really. It was a test of the Senate and they failed. They heard that the Jedi were killed, wiped out completely, and they applauded. If Palpatine had announced that and barely anyone had clapped, and instead had started protesting, that may have been the downfall of the Empire before it even started (then again Palpatine is a sneaky bastard with many plans).

The Jedi had been there since the start of the Republic, and even if the Senators had a negative view of them and their work in the war, they heard they had all been killed and cheered. It doesn't matter how much you dislike someone, or a particular group, it shows something when you cheer to hear they had all been killed right down to the young ones (no guarantees whether random Senator Glup Shitto would know about the Jedi children being killed but they would have definitely known about the padawans).

And because the Senate showed they were more than happy to cheer for a massacre (whether out of glee or fear, it doesn't matter that much when it comes down to it), it let Palpatine know that he could commit a lot more atrocities and the Senate (and so the people) would accept it. After all, you cheer for one massacre, what's to stop you cheering for another? Or enslaving an entire group of people?

The symbolism of the empire being born on the day of the jedi’s slaughter is so raw TT

#star wars#rise of the empire#it's the whole thing isn't it#it always starts small and then leads to bigger things#(not the massacre of an entire people is a small thing)#(but the jedi were a small amount of people a way of life that seemed strange to others and an unpopular public image)#so ryloth and kashyyyk and so on

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

#star wars#the Phantom Menace#attack of the clones#revenge of the sith#a new hope#the empire strikes back#return of the Jedi#the force awakens#the last jedi#the rise of skywalker#the clone wars#star wars rebels#star wars andor#rogue one

450 notes

·

View notes

Text

jay seasons my beloved<33

772 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dooku being killed by Anakin is super thematically satisfying but I can't stop thinking about a slightly altered timeline where he is publicly executed on Coruscant instead. Can you imagine the SCENE

#definitely a good way to kick off the rise of the empire. banners flying clouds whirling big changes coming#let's behead the separatist leader on the senate square#dooku still gets robespierre'd and sidious still happily watches like in RotS. but now it's on live tv <3#and you know dooku would be so fucking angry and miserable and beaten#and you BET asajj would come watch it in person#is anyone else a little bit abnormal about this?#count dooku#star wars

636 notes

·

View notes

Text

father’s daughter

#star wars#anakin skywalker#leia organa#princess leia#darth vader#the phantom menace#attack of the clones#revenge of the sith#a new hope#the empire strikes back#return of the jedi#the force awakens#the last jedi#the rise of skywalker#anidala#vaderdala#padme amidala#padme naberrie#star wars anakin#anakin and padme#sw anakin#sw leia#luke skywalker

740 notes

·

View notes

Text

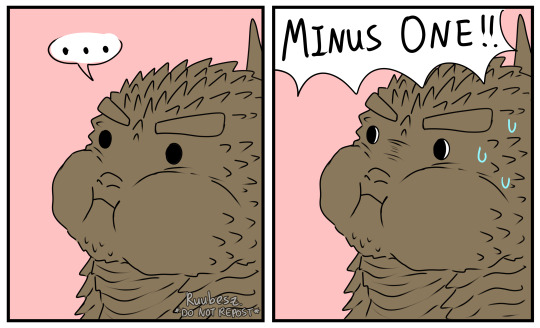

Minus One meets Emi

Emi is fine... just shooked

#godzilla#godzilla x kong: the new empire#godzilla minus one#ultraman#ultraman rising#ken sato#emi ultraman#fun fact: this is NOT minus one and emi's first meeting#fun FUN fact: this will not be their last either lol#emi is okay btw#she lives#but Ken probs need to go to hospital#since he nearly passed out from near heart attack#MV godzilla just tryna keep things peaceful#minus one is NOT helping tho#Emi will go through lots of... hardships ig#she'll grow up strong :')#do not repost#my art

3K notes

·

View notes