#relative clauses in Spanish

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Relative Clauses(oraciones relativas) with Subjunctive in Spanish

Introduction Relative clauses, or oraciones relativas, are an essential part of Spanish grammar. They allow us to add extra information about a noun without starting a new sentence. When combined with the subjunctive mood, relative clauses take on a more nuanced meaning, often expressing uncertainty, doubt, or hypothetical situations. Mastering this structure is key to sounding more fluent and…

#A1#A2#advanced Spanish grammar#B1#B2#blog#C1#C2#daily prompt#DELE#dios#English#espanol#examples of relative clauses in Spanish#how to use relative clauses in Spanish#Japanese language learning#latin america#learn Spanish grammar online#mexico#My English class#My Japanese class#my language classes#My Spanish class#oraciones relativas#relative clauses in Spanish#siele#spain#Spanish#Spanish examples#Spanish fill in the blanks

0 notes

Note

When looking at natural languages, have you ever found a feature that really surprised you?

All the time—and in every language! There is no language—even the big ones that are so widely spoken that they're thought of as "normal"—that can be described as basic or boring—no, not even languages like English or Spanish or German. Every language has something exciting—multiple somethings.

For the latest, here's something weird. In Finnish, numbers trigger singular agreement on the verb. Observe:

Hiiri juoksee. "The mouse is running."

Hiiret juoksevat. "The mice are running."

Viisi hiirtä juoksee. "Five mice are running."

Okay, this make sense so far? Hiiri is "mouse", hiiret is "mice", and we have the agreement on the verb as either juoksee for singular ("is running") or juoksevat for plural ("are running"). The number five is viisi and it causes the following noun to be in the partitive singular, which is hiirtä (think of it like "five of mouse"). "Partitive singular?" you say. "Why, that's why the verb is singular!" Okay. Sure. A fine hypothesis.

Now let's look at relative clauses.

How about "The mouse who is running is small"? Sure. Here it is in singular and plural:

Hiiri, joka juoksee, on pieni.

Hiiret, jotka juoksevat, ovat pieniä.

There we are. I am 99% sure that is correct (where I'm unsure is the predicative adjectival agreement and I won't speak to how common this type of relative clause structure is).

Now, knowing what we do about the five mice above, you might expect you'd get singular, but...

Viisi hiirtä, jotka juoksevat, ovat pieniä.

Okay, going out on a limb on this one, but I am fairly certain this is correct. That is you get singular plural agreement with the matrix verb suddenly (?!) but also plural agreement with the relative clause. You have to get a plural verb because it's agreeing with jotka, but why do you get jotka instead of joka?! It's plural enough for a relative pronoun but not for a matrix verb?! How weird is that?!

So yeah. Unbelievable stuff happening in every language every single day. Somewhere right this very moment some language is doing something no language could EVER possibly do—and yet there it is, happening all the same! What a wonderful world we live in. :)

Update: Finnish speaker has offered corrections and it’s just weirder now.

505 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction to Collective Seraphic

Now that Seraphic's at a stable place, I think I'm gonna take some time to delve into the basics of how it operates. For this post I'll only be going into the language itself and not the writing system, as that's going to need a post of its own to elaborate on. I'll try to keep this as concise as possible, but I may make separate posts expanding on topics discussed in this one. So, without further ado, onto the infodump!

Background

Collective Seraphic (which I'll be referring to as "Seraphic") is an artlang that I've created for a comic that as of this post I have not began yet, but am still developing. The majority of the comic will take place on the Seraph Homeworld, an alien planet some 3,000 lightyears from Earth populated by the seraph species (pictured below):

Within the story, Seraphic acts as the lingua franca of the Seraph Homeworld and the many colonized planets under Seraph control. It's used in the government, and among speakers of differing languages. As such, this language was the first one that I knew I would need to make as it will play a vital role in both the storytelling and narrative structure.

Syntax

Seraphic is largely a fusional language, employing affixes to modify the semantic role and meaning of morphemes. Seraphic does not, in the traditional sense, have verbs, so the sentence structure is strictly subject-object (will expand upon later). Nouns decline for number and tense, and are grouped into seven noun classes. Adjectives agree with nouns in number, except if derived from nouns themselves, in which case they'll also agree in class. Seraphic is very head-initial; with demonstratives, numerals, possesives, adjectives, genitives, and relative clauses following the noun the modify; and prepositions preceeding the nouns they modify. Auxiliaries preceed procedurals (again, will expand upon later).

Phonology

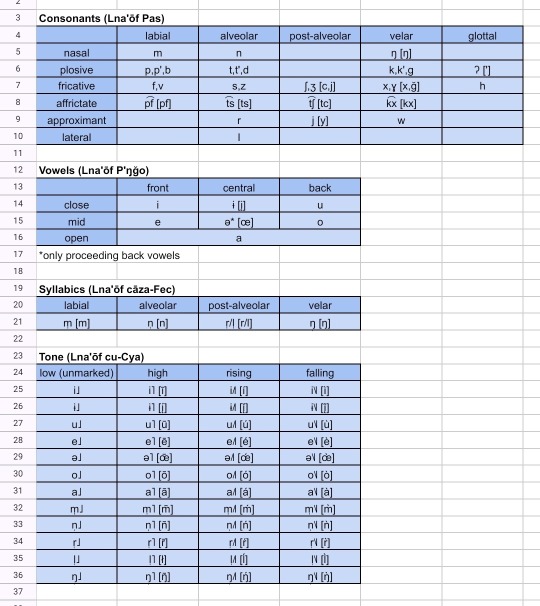

Here is the phonological chart for Seraphic:

It has a syllable structure of (CC)V(CC). Plosives cannot exist word finally, clusters of consonants of the same manner are illegal, and vowel clusters are also not permitted. Syllabic consonants are grouped with vowels and behave much like them, carrying tone and stress, so they together are grouped and referred to as vocalics. Seraphic is a tonal language, employing the use of four tones: rising (á), falling (à), high (ā), and low (a). Low tones remained unmarked in both the Seraphic script and in romanization. Stress is syllable-independant. It will take either the ultimate, penultimate, or rarely the antepenultimate. Stress always falls on the syllable with a voiceless initial obstruent nearest to the end of the word. If none are available, it will fall on the syllable with an initial sonorant within the same parameters. Stress will never fall on a voiced obstruent. For clarity, I'll provide a key describing the pronunciation of the romanization.

Sounds that are similarly pronounced as they're read in American English:

m, n, p, b, t, d, k, g, f, v, s, z, y, w, l

Sounds that have special pronunciations:

ŋ, like the ng in English "sing"

p', like the ጴ in Amharic "ጴጥሮስ"

t', like the t' in Navajo "yá'át'ééh"

k', like the კ in Georgian "კაბა"

', like the the space within English "uh-oh"

c, like the sh in English "sharp"

j, like the s in English "measure"

x, like the gh in English "ugh"

ğ, like the γ in Greek "γάλα"

pf, like the pf in German "Pfirsiche"

ts, like the z in Italian "grazia"

tc, like the ch in English "chain"

kx, like the kh in Lakota "lakhóta"

r, like the rr in Spanish "perro", although occasionally like the r in Spanish "amarillo"

i, like the ee in English "meet"

į, like the ы in Russian "ты"

u, like the oo in English "boot"

e, like the é in French "beauté"

œ, like the a in English "Tina"

o, like the o in Classical Latin "sol"

a, like the a in English "bra" although this can change to be more forward or more backward.

Another letter that might trip people up is ł, which is meant to represent the high tone syllabic 'l'. Otherwise, syllabics are written the same as their pulmonic counterparts, with tone markers written when applicable.

Nouns

Nouns make up the bulk of the Seraphic lexicon. Every noun is grouped into one of seven classes:

Solar class: nouns related to seraphim or seraph-like beings, and seraph body parts. Prefix appears as zā-, zō-, zē-, s-, or ts-.

sēr = "person"

Astral class: nouns related to non-seraph animate lifeforms (their equivalent to "animals"). Prefix appears as ğr-, x, or kx-.

xuc = "cherub"

Vital class: nouns related to inanimate lifeforms (their equivalent to "plants"). Prefix appears as wā-, wō, w-, ū-, wē-, or wī-.

wējlux = "tree"

Terranean class: nouns related to landscapes, locations, and natural phenomena. Prefix appears as va-, vo-, vu-, f-, and pf-.

voxāl = "sun"

Metallic class: nouns related to inanimate objects, both natural and artificial. Prefix appears as ja-, jo-, c-, or tc-.

jağrú = "rock"

Lunar class: nouns related to abstract concepts, and terms related to time. Prefix appears as la-, lo-, le-, li-, y-, or l/ł-.

levren = "job"

Oceanic class: nouns related to general words, tangible concepts, numbers, all adjectives, and non-incorporated loanwords. Prefix appears as a/ā-, o/ō-, or aw-.

awuf = "group"

Adjectives do not agree in class, due to the fact that nouns originally are derived from adjectives, and noun classes acted as a way to differentiate between nouns and adjectives.

fa = "warm, hot"

jafa = "fire" (lit. "a hot thing")

When adjectives are used as predicatives, they decline into the oceanic class in order to take the procedurals (once more, will expand upon later).

Nouns also decline for four numbers: singular (one thing, usually unmarked), dual (two things, both things; suffixes as -ac, -oc, -œc, or -c), plural (things, many thing; suffixes as -n, -an, or -in), and collective (every thing, all things; suffixes as -āf/ōf, -áf/-óf, or -'ōf).

Seraphic doesn't use pronouns. Everything and everyone is referred to by name, including yourself. From our perspective, the Seraphic language constantly speaks in the third person. However, it can be repetitive to use the same name over and over again in a sentence, and sometimes you don't know the name of things, so they'll apply what I've called pro-forms. They consist of the demonstrative adjectives fl "this", sl "that", and xl "yon" declined into the Solar class and taking the place of the first, second, and third person respectively. For ease of reference, I'll provide the forms and their declensions below.

zāfl (I/me), zāflc (both of us), zāvlin (we/us), zāfláf (all of us)

zāsl (you), zāslc (both of you), zāzlin (you guys), zāsláf (all of you)

zōxl (they), zōxlc (both of them), zōğlin (many of them), zōxláf (all of them)

Seraphic makes no distinction in the gender of the speaker, in this regard. Although these resemble pronouns, they're not meant to be used as often as regular pronouns, and whenever possible it's much preferred that you refer to someone or something by name.

Adjectives and Prepositions

Adjectives are fairly straightforward. Adjectives follow the noun they modify (e.g. sēr tan "big person"), and agree with them in number (e.g. sēr tan "big person" vs sērn t'aŋon "big people"). Adjectives agree in the singular form with singular and collective nouns, and they agree in the plural form with dual and plural nouns.

There are three main types of adjectives: native adjectives (e.g. cna "good"), borrowed adjectives (e.g. anzn "nice"), and noun-derived adjectives (e.g. arfi/ofi "new"). Native and borrowed adjectives don't agree with noun classes, but noun-derived adjectives do. It originated from the animacy-based adjective agreement system in Proto-Seraphic, which has been lost in all other adjective instances. When you want to make a noun into an adjective you'll affix one of two prefixes to it: ar- (if agreeing with Solar, Astral, and Vital nouns) and o- (if agreeing with Terranean, Metallic, Lunar, and Oceanic nouns). There are specific rules on the forms each prefix takes based on the noun they're attached to:

"ār-" when preceeding high or falling vocalic syllables (e.g. sēr ārzājna "popular person")

"ar-" when preceeding low or rising vocalic syllables (e.g. wēn arfe "local fruit")

"ó-" when preceeding high or falling vocalic syllables (e.g. lalel ówē "grassy flavor")

"o-" when preceeding low or falling vocalic syllables (e.g. lesar olvulvren "economic problem")

"ōw-" when preceeding words that start with a vocalic (e.g. lnin ōwāsāvbas "momentary event")

Prepositions occur before the nouns they modify, and don't change form in any circumstance. There are currently 19 prepositions in the modern language, and they are usually connected to nouns via a hyphen (e.g. e-fe "at (the) place"):

cu = of; indicates possession

pr̄ = indicates the indirect object, equivalent to "to" in the phrase "The man sends the letter to me."

in/īn = as or like; indicates similarity or resemblance. Will either be low or high tone depending on the tone of the following syllable.

e/ē = at or on; indicates location.

tsa = near or for; indicates relative distance from a location or an action performed for the sake of the referent.

cni = without; indicates a lack of possession or company.

wa = in or inside of; indicates interior position.

tn = on top of, above, or before; indicates superior position or a prior instance in time.

pux = under, beneath, or after; indicates inferior position or a following instance in time.

pi = with, together with; indicates being in company of or making use of the referent.

fān = from or away from; indicates the motion of leaving the referent.

ku = out of; indicates motion from within the referent towards the exterior.

tun = into or through; indicates motion from outside the referent towards the interior.

xel = to or towards; indicates the motion of approaching the referent.

kxun = across; indicates motion from one location to another

pn̄ = around; indicates location surrounding the referrent.

cāza = between; indicates location in the middle of the referrent.

tē = after, behind; indicates posterior position.

fr = during; indicates a moment in time

Prepositions aren't combined in Collective Seraphic, but may be in certain instances in colloquial speech.

Procedurals

Okay, this is probably the most complicated part of Seraphic, so I'm going to need to get into things individually. First, I'll start with defining a procedural itself. Procedurals are the term I use for the prefixes used to describe the relationship or process of and between the agent noun and the patient noun. These are what act as the equivalent to "verbs" in earth languages. There are three in use:

Existential: used to denote a state of being or equivalence between agent and patient, or to the patient and itself. Equivalent to English "to be" (e.g. A is B, there is B). Usually prefixes as some variant of n-, m-, or ŋ-.

Actional: used to denote an action or process between the agent and patient, or with the patient and itself. Equivalent to English "to do" or "to act upon" (e.g. A acts upon B). Carries a connotation of agency and intent. Usually prefixes as some variant of re-, ra-, or r-.

Resultative: used to denote an occurence or change in state between agent and patient, or patient and itself. Equivalent to English "to become", "to happen", or "to change into" (e.g. A becomes B, B happens to A). Carries a connotation of passiveness or motion. Usually prefixes as some varient of ed- or ez-.

The procedural will change its form slightly depending on the class and declension pattern of the noun it modifies. It always affixes to the patient noun, demonstrating a relationship of an action and what is being acted upon. In this way, the patient can be clearly identified. In transitive or causative clauses, the word order is always S(P)O, with the agent acting as the subject and the patient as the object. In intransitive and passive clauses, the word order is always (P)S, with the patient acting as the subject and the agent demoted to the indirect object or omitted entirely.

Although seemingly limiting, using these three procedural, as well as prepositions, nouns, and adjectives, altogether can be used to make all sorts of verb equivalents that are called "procedural phrases". I'll demonstrate how to build a sentence now. First thing we need to know is the subject and object:

Sāx ... jafa (The child ... the fire)

Next, I'll add the actional procedural in the present tense to this.

Sāx rejafa (The child acts upon the fire)

By itself this is technically grammatically correct, but it doesn't really mean anything. It's too broad. So we add a prepositional phrase to specify exactly what action the child is taking towards the fire.

Sāx pi-sīman rejafa (The childs acts upon the fire with (their) eyes)

Now we know that the child is performing an action involving the use of their eyes. Now of course this could mean many different things in English, but in Seraphic the first thing that comes to mind would be fairly obvious: to see! Thus, "Sāx pi-sīman rejafa" would be the same as saying "The child sees the fire" in English! There are a lot of set phrases that equate to verbs, and remain consistent in their arrangement. Often differing phrases are a useful way to ascertain where someone is from or what their first language is.

Tense and Aspect

Seraphic has six main tenses: two pasts, two presents, and two futures. The two pasts consist of the recent past (happening recently) and the remote past (happening a long time ago), and they prefix and/or combine with the procedural.

Sāx pi-sīman ğrejafa (The child just saw the fire)

Sāx pi-sīman eğrejafa (The child saw the fire a while ago)

Similarly, the future tenses consist of the near future (will happen soon) and the distant future (will happen eventually).

Sāx pi-sīman drejafa (The child will soon see the fire)

Sāx pi-sīman izrejafa (The child will eventually see the fire)

The present tenses consist of a general present tense (happens) and the infinitive (to happen) which is used with auxiliaries and copulae and carries no presence in time.

Sāx pi-sīman rejafa (The child sees the fire)

Pi-sīman ezrejafa (To see a fire)

Whether someone considers an event to be nearer or farther in time from them is completely up to their discretion. There's no set timeframe for when to use the recent vs. remote past, it's all fairly subjective. However, whether you decide to use the recent or remote can really indicate whether you believe something to be in the distant past or future, or just a few moments ago or soon.

Seraphic also makes use of two copulae, the perfective -r and the imperfective -l, helping clitics that expand on the aspect of the procedural, i.e. how the procedural happens over time instead of when in time. The copulae are separate from the procedural, being placed directly before it and conjugating on their own similarly to the lexical procedural. When the copulae are in use, they are conjugated instead of the lexical procedural, while the lexical will be put into the infinitive. The exception to this is if the point in time is considered necessary to be stated for the sake of clarity or emphasis, in which case the lexical verb will also conjugate (though this isn't considered to be the default). The two copulae each conjugate to six tenses, and give 12 individual aspects in total. They are as follows, starting with the perfective:

āgxōnr - Pluperfect: indicates that the action happened at a point before some time in the past either specified or implied (e.g. āgxōnr nidsl "that has happened")

xōnr - Preterite: indicates that the action happened in the past with no reference to if it was completed recently or remotely. A general past (e.g. xōnr nidsl "that happened")

nar - Relative: indicates relative clauses, i.e. clauses that act to modify a noun similarly to an adjective. Equivalent to "that", "who", or "which" (e.g. lsl nar nidsl "the thing that happens")

ednr - Gnomic: indicates general truths, common knowledge, and aphorisms (e.g. ednr nezłsl "things happen")

t'enr - Future Simple: indicates the action will happen in the future with no regard to how near or far it is from the present (e.g. t'enr nidsl "that will happen")

āt'ēnr - Future Perfect: indicates that the action will happen before a time or event in the future (e.g. āt'ēnr nidsl "that will have happened")

And the imperfective:

ŋ̄xōzl - Discontinuous: indicates that an action was happening in the past, but is no longer happening in the present (e.g. ŋ̄xōzl nidsl "that used to happen")

xōzl - Habitual: indicates that an action is done often or out of habit (e.g. xōzl nidsl "that always happens")

īzl - Progressive: indicates that an action is happening at the very moment of conversation (e.g. īzl nidsl "that is happening")

nizl - Prospective: indicates that an action will be starting to, or is in the process of happening (e.g. nizl nidsl "that is about to happen")

t'ezl - Iterative: indicates that an action happens again, repeatedly, or more than one time based on context (e.g. t'ezl nidsl "that happens again" or "that happens again and again")

nt'ezl - Continuative: indicates that an action happens continuously and without end (e.g. nt'ezl nidsl "that still happens")

With both tense and aspects, this largely expands the capability of Seraphic in referring to time.

Moods

Seraphic makes use of seven modal particles to denote seven moods. They are always placed at the beginning of clauses, and no two modal particles can exist in the same clause. They are grouped into four categories: the declaritive (indicative and negative), the inferential (evidential and interrogative), the deontic (volitive and imperative), and the epistemic (subjunctive and conditional). They add extra clarity in the speakers mood or opinion concerning the clause they modify, and are as follows:

Indicative: base form of a clause. Indicates that the speaker is stating a fact or what exists, and is unmarked (e.g. idsl "that happens")

tu - Negative: indicates that the speaker is stating a fact that is untrue or what doesn't exist. Usually only appears in formal, official texts, as the first syllable of the procedural will chage tone to contrast as well and leaves the particle unneccesary in colloquial speech (e.g. tu īdsl "that doesn't happen")

cuc - Evidential: indicates that the speaker is stating a fact that they believe or understand to be true, regardless of having experienced it or not. (e.g. cuc idsl "apparently that happens") Direct evidentiality is denoted using a different method.

an/ān - Interrogative: indicates that the speaker is confirming whether a statement is or isn't true. Forms questions (e.g. an idsl? "does that happen?")

tcān - Volitive: indicates that the speaker desires for the statement to be true (e.g. tcān idsl "that wants to happen" or "that needs to happen" or "that should happen")

má - Imperative: indicates that the speaker is giving a command or suggestion, to themselves and/or to other referents. Functions additionally as a cohortative and a jussive (e.g. má idsl! "let that happen!")

tir - Subjunctive: indicates that the speaker believes the statement to be possible or likely (e.g. tir idsl "that could/would/might happen")

nun - Conditional: indicates that speaker believes the statement to be possible under specific circumstances or conditions (nun idsl "if/when that happens..."

Miscellaneous

That's about the basics of the Seraphic language outline. I'd like to eventually get into things like comparison, evidentiality, declension forms and the like, but those are all topics that definitely need their own individual posts. Real quick, I want to provide one more additional fact about Seraphic.

Seraphic uses base-16, meaning it groups numbers in sets of 16 instead of sets of 10 like we do. 1-16 would be written 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, A, B, C, D, E, F, 10. 10 would be read as 16, and equally 20 would be 32. They're still counting the same amount of things, they're just dividing it up differently!

Anyways that's about it, I hope to share more about Seraphic soon, and when the comic gets released I hope you'll all be able to read it and pick out the many many lines of Seraphic I've poured into it!

ŋKowīci cu-stux 'ōf tsa-levp'ā cu-zāsláf pi-lizt'n ğōdjasa! (Thank you all so much for reading!)

#conlang#constructed language#artlang#grammar#phonology#syntax#linguistics#seraphic#collective seraphic#info post#hope i didn't make a fool of myself in front of the whole community#accidentally showed the world i dont know shit abt linguistics gotdamn#im sure itll be fine#writing system tutorial forthcoming

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twenty Questions

Thank you @cupofteaandstars for the tag!

1. How many works do you have on AO3? 16, plus a Spanish translation a friend did of one of my works.

2. What's your total AO3 word count? 73,165, for now.

What fandoms do you write for? Exclusively Stranger/Secret Forest and related crossovers, although there was that one Andor one that I just had to put out there to cope with the intensity of my feelings about the cliffhanger season ending.

What are your top 5 fics by kudos?

It's a close race among some of these, but:

gamsa

chilyo

chib

heonsin

haengbok (with maengse only one behind at the moment)

Do you respond to comments? Why or why not?

I do, always! I'm honestly always so astounded and delighted to think of someone reading my work while I'm just out here having a normal Monday or Tuesday, and want to express that delight.

What is a fic you wrote with the angstiest ending?

Oh boy, just you wait.

What's the fic you wrote with the happiest ending?

Since all things Si-mok and Yeo-jin related (or Stranger-in-general-related) are usually bittersweet, probably inyeon, a relatively recent one. However, the one that leaves me with the warmest feeling at the end is actually pyeongsaeng.

Do you get hate on fics?

Fortunately not! I've gotten a few weird comments once or twice but nothing mean-spirited.

Do you write smut? If so, what kind?

I do not, and the few times I've been tempted I have realized swiftly that I'm not cut out for it.

Do you write crossovers? What's the craziest one you've written?

Only within the Stranger/SF multiverse so far - in other words, AUs for Stranger/SF that are based on Bae Doona and CSW's other works, which I think of as other lives of Si-mok and Yeo-jin.

Have you ever had a fic stolen?

Ditto Cup, not that I know of. I would go absolutely off-the-charts feral in order to get the copycat fic taken down.

Have you ever had a fic translated?

I have! My IRL best friend of many years graciously wrote me a Spanish translation of chib.

What's your all-time favorite ship?

Eh, I'm not really a shipper...? HOWEVER, @ohyangchon has given me massive Changjae feelings and I love their relationship so much.

What's a wip you want to finish, but doubt you ever will?

Scenes just sort of seem to come to me, and once they're there I don't stop until they eventually coalesce into a complete story, no matter how long that takes to find its shape. I do have an extensively Yeo-jin and Si-mok inspired novel (low-key sci-fi? space opera?) that has been nagging at me for years, but I don't think that one will ever amount to anything.

What are your writing strengths?

I'd like to think I inhabit the voices of the characters well.

What are your writing weaknesses?

Pacing, probably?

Thoughts on writing dialogue in another language for a fic?

Similar to Cup's thoughts, this is difficult because I feel like sometimes names, titles, and terms of address in particular just don't have the same nuance and feeling translated from Korean into English-- especially the terms of address that Si-mok and Yeo-jin and others use for each other. Therefore, sometimes I do transliterate. Also, as I become a little bit more comfortable IRL speaking Korean, where practical I sometimes find myself wanting to mimic the Korean clause order/speech patterns of sentences even while writing in English.

First fandom you wrote for?

I think it must have been a gift fic in the Redwall fandom (never made it to AO3, but a cozy and comforting thing to work on)

Favorite fic you've written?

I love all my children equally!!! But I do think I did some really great character work in bohoja, one of my works on a more underrated duo (Si-mok and Mr. Kang). I usually am pretty self-critical, but there are a few lines in there that I always read and think "damn, who wrote that???" XD

Who hasn't been spoken for? Tagging @gottagobuycheese, @inkingtwice, and @michyeosseo as well as anyone else who's interested!

#my original fic#stranger#tvn stranger#forest of secrets#secret forest#stranger 2#tvn stranger 2#forest of secrets 2#secret forest 2#*gasp* personal information about me????#only Cupofteaandstars and ohyangchon could have dragged this out of me

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

26.11.24 | things done today:

📚 English

podcast

read In The Heart of The Sea by Nathaniel Philbrick (ch. 9)

clozemaster

📚 Spanish

clozemaster

read Diarios Completos de Sylvia Plath (p.268-274)

📚 French:

relative clauses (textbook grammar & lexicon)

read an article | louis pasteur & marie curie

clozemaster

📚 German

unit review (textbook vol. I)

reading & translation | Renaissance Literature (textbook literature & history)

clozemaster

📌 Extra activities

Women Who Run With The Wolves | ch. 6 + journaling

📖: The Druid of Shannara by Terry Brooks

📻: Radio Rapture 6 Ambiance {BioSHock} asmr by Steven PaulDark

1 note

·

View note

Text

Barcelona mayor backs ban tourist rental apartments

Barcelona’s mayor has defended a ban on flats for tourists, saying “decisive” measures are needed to cut housing costs. Jaume Collboni is determined to implement the plan, which he said would return 10,000 properties to the city’s residents, Spanish media reported.

The decision hit headlines around the world, prompting surprise and threats of lawsuits worth billions of euros but months after Barcelona officials announced plans to rid the city of tourist flats by the end of 2028, the city’s mayor called it a “radical” but much-needed step to curb rising housing costs.

Jaume Collboni said in one of his first interviews with international media since the June announcement:

“It’s a very radical step, but it’s necessary because the situation is very, very difficult. In Barcelona, as in other major European cities, the number one problem is housing.”

Over the past 10 years, rental prices in the city have risen by 68 per cent, while the cost of buying a home has risen by 38 per cent. As some residents complained about the high cost of living in the city, Colboni began looking into the 10,101 licences issued by the city allowing them to rent out accommodation to tourists through platforms such as Airbnb.

The Socialist Party mayor saw this as a relatively quick way to increase the number of residences in the city, while also reducing the number of some of the 32 million tourists who visit the city (1.7 million a year). The mayor added:

“Within the mass tourism model that has colonised the city centre, we have seen significant damage to two things: the right of access to housing, as housing is used for economic activities, and coexistence between neighbours, especially in areas with more tourist flats.”

Catalan city authorities have long tried to address the issue by setting limits on the number of tourist flats. Collboni claimed:

“After many years, we have come to the conclusion that doing something half-heartedly is useless. It’s very difficult to manage and make sure there are no illegal rentals. It’s much easier and clearer to say there will be no more tourist flats in Barcelona.”

While some criticised the years it would take for the measure to come into effect, Collboni set a timeframe of up to 2028 in line with regional legislation that last year limited the issuing of tourist accommodation licences to five years in restricted areas. It was in this clause that Barcelona officials saw their chance: in 2028, when Barcelona’s current number of licences expire, they plan to simply not renew any of them.

The idea has significant limitations, however. Collboni’s term as mayor of the Catalan capital ends in 2027, which could result in the plan being cancelled if elections result in a change of municipal government. Regional law also allows owners to request a one-off extension of up to five years if they can prove they have invested heavily in the property, although Collboni says such cases make up a “minority” of licences in Barcelona.

Instead, he hopes the plan will see more than 10,000 properties returned to the residential property market, where recent rent restrictions and an expected national register aimed at limiting short-term rentals will ideally prevent them from becoming luxury flats or monthly rentals. The city’s team of about 30 inspectors, which officials say identifies more than 300 illegal tourist flats a month, will be beefed up by 10 more positions in the coming months and will continue to operate at full capacity after 2028 to crack down on any illegal rentals that may arise.

The June announcement took many residents by surprise. Jaume Artigues of the Eixample Dreta Neighbourhood Association, which represents an area that contains about 17% of the city’s legal tourist flats – some 1,655 of which are located in the central district, known for its modernist architecture, said:

“We didn’t think it was so radical. I think it’s a very, very bold measure because it will be a tough legal fight against the economic interests of this sector.”

But Artigues is concerned about the protracted timeline, calling it a risky deal in a city where access to housing has already become an emergency. That view was echoed by Albert Freixa of the Eixample Housing Syndicate. He said:

“You can’t promise something for 2028, when there will be elections and you don’t even know if you will be mayor.”

In September, Apartur, an organisation representing management companies and owners of 85% of legal tourist flats in Barcelona province, announced plans to sue for compensation for lost revenue and investment. Describing the city’s plan as a “covert forced expropriation,” the organisation suggested that the claims could be as high as €3 billion.

The country’s constitutional court is also due to review the plan. In February, it agreed to consider a lawsuit filed by the conservative People’s Party, which argued that regional legislation had, among other things, overstepped its bounds when it came to how private property could be used.

Collboni compared the argument to someone trying to open a four-table restaurant in their home. He said:

“No one would do that. Because you have to meet hygiene standards, you have to pay taxes, you have to have full-time staff to operate there. We say no, you can’t do whatever you want with your property. The flat is meant for living, it’s not a business.”

The scandal comes as tensions around tourism in Barcelona continue to heat up. This summer, some people’s anger spilled out after several protesters with water pistols in hand sprayed water on tourists, while others held placards reading “Tourists, go home” and “You are not welcome here.”

According to Collboni, what happened was not a reflection of how most residents feel. He said, pointing to La Rambla, a tourist-infested boulevard with many souvenir shops, as an example of an area that some residents feel has been overtaken by mass tourism:

“But it is true that there is anxiety in the city because we are losing some areas of the city. Tourism has to be limited to what the city can really absorb. We can’t grow indefinitely at the expense of those who live in the city.”

Read more HERE

#world news#news#world politics#europe#european news#european union#eu politics#eu news#spain#spain 2024#spain news#spain politics#spain travel#spain trip#barcelona spain#tourism#tourist#rental service#rental apartments

0 notes

Text

Ch'ubmin Word Order Indecision

First Tumblr post ever! So I’m going to do a bit of conlang infodumping.

I’ve spent the last couple of weeks stuck on the main clause word order principles for Ch’ubmin (my current conlang). Ch’ubmin is a synthetic language, mostly verb-initial, with polypersonal agreement and incorporation, and somewhat inspired by Mayan and some other native North American languages.

The thing I’m most certain of is the function and structure of contrastive fronting. Like many verb initial languages, and like some Mayan languages, Ch’ubmin has both contrastive topic fronting and contrastive argument focus fronting. The difference between these is partly word order, intonational, and partly morphological.

Fronted Topics (Left-dislocated)

The topic can be offset from the clause by an intonation break

The topic is normally marked by a deictic particle / demonstrative that otherwise occurs clause finally

Topic fronting has no impact on the form of the following verb / clause, which behaves like any other clause. The topic can control zero anaphora or a resumptive pronoun

Fronted Focus

The focus is part of the same intonational contour as the clause

Extraction of the focus requires the verb to be in its conjunct form, which is the same form used for relative and adverbial clauses (i.e. this is a kind of cleft)

Resumptive pronoun highly marked / forbidden, but the extracted focus can control verb agreement and possessor agreement on ordinary nouns and relational nouns / prepositions

When both are combined, the order can only be topic - focus - verb. Examples:

Fronted topic only

in tacha' ai, rena'

DET man TOP, 3-thither-be

`As for the man, he went'

Fronted focus only

in tacha' nuyoha' o'

in tacha' nu-yo-ha' o'

DET man CONJ.PFV-VEN-be DEIC

`The man was (the one) who came'

`The man came'

Fronted Topic + Focus

in tacha' ai, il hemen nulít o'

DET man TOP, DET woman CONJ.PFV-see DEIC

`As for the man, he saw the woman'

`As for the man, the woman saw him'

The last example raises the unanswered question of role marking. In the specific case where the focus is on a single argument and the rest of the clause is backgrounded or presupposed I think the risk of ambiguity is lower in context, but that’s certainly not the case for the unmarked post-verbal clause structure and word order which I haven’t described yet.

The first thing to say here is that, if you have a highly synthetic language with polypersonal agreement, it’s likely to allow free dropping of arguments, and Ch’ubmin does. That means that if you have transitive verb + argument, in principle the argument could be either the agent or the patient. And, unlike some head-marking languages, Ch’ubmin does not have direct/inverse voice or pragmatically driven voice which would distinguish between the topical/dropped argument being the actor or patient.

Focusing on I guess there are three major options worth considering:

Rigid post-verbal word order, no case marking

Flexible post-verbal order, no case marking

Flexible post-verbal order, case marking

The Original Idea for the Post-Verb Domain in Ch’ubmin

I had originally planned (3). There is an ablative-instrumental preposition fe’ which contracts with the determiner to give forms bel~ben~ber, much like Spanish de+el = del or French de+le = du, which I had planned to be an ergative/marked nominative marker, combined with free word order. And there are languages with optional ergative or nominative markers, which generally surface under conditions of either focus / non-default information structure, or ambiguity. See:

Optional ergativity and information structure in Beria

The table above, taken from the article, illustrates that in Beria, =gu mostly occurs when A is focused or low-topicality, or when it is necessary for disambiguation.

Similarly for Tibetan languages with optional ergative/nominative markers:

“OPTIONAL” “ERGATIVITY” IN TIBETO-BURMAN LANGUAGES

“What we find, across Tibetan and in the majority of languages across the family, is that in elicited data we have something approximating a consistent ergative, aspectually split-ergative, or active-stative case marking pattern, while in natural discourse the ―ergative‖ marking is found only in some clauses, often a minority, usually with some pragmatic sense of emphasis or contrast.”

“Tournadre notes the same interaction with word order, and points out that there is no syntactic environment where ergative is truly obligatory, and that wherever it occurs it indicates contrastive focus (see also Zeisler 2004: 514ff). He shows that the presence or absence of ergative marking often seems to have a pragmatic (or ―rhetorical‖) force, such that the presence of ergative marking serves to emphasize the agentivity of the A argument, or to place it in discourse-pragmatic focus.”

“Not all TB languages have been described as ergative; a significant set, including many Lolo-Burmese and Bodo-Garo languages, appear at first glance to have a more nominative-accusative cast. But for Burmese, the best-known example, the case is by no means so simple. As in Tibetan and elsewhere, ―subject‖ marking is not syntactically obligatory, but is strongly determined by pragmatic factors; this has been a long-standing problem in Burmese linguistics.”

Finding examples of languages with flexible VSO / VOS word order is also not hard, although finding a detailed description for what motivates word order differences is harder. A number of factors seem to play into such word orders: Ojibwe seems to prefer verb initial verbs and for the obviative argument to be closer to the verb, which generally produces VOS orders but permits VSO especially when verbs are in the inverse voice. Only some Mayan languages have flexible word order, but those that do also tend to be VOS but with VSO permitted due to factors like animacy, definiteness, argument weight (heavy shift) etc. In both these examples, topic fronting and zero anaphora is common, so it has to be remembered that VOS really means a choice of S realisation between:

Highly topical S not overtly present in clause

Established afterthought topic S in VOS order

New topic or contrastive topic fronted to clause initial position

The VOS default order effectively keeps the predicate together and focal material early in the clause, with the normally topical S on the periphery (either last or fronted into topic position). S only gets sandwiched next to the verb if it is a defective subject in some way. The alternative, VSO as the default and VOS as a marked alternative when S is focal or non-topical, also seems to occur.

An example is Alto Perené, an Arawak language there happens to be a good grammar for. Elena Mihas’ grammar says:

“Definiteness of noun referents does not affect constituent order. Both definite NPs, typically active topics, and indefinite NPs, typically newsworthy information, tend to occur post-verbally in particular slots, as shown in (13.109)-(13.112). The post-verb position at the right periphery is occupied by a non-contrastive focus constituent, whereas topical NPs are located immediately after the verb.”

Thus the post-verbal order in Alto Perené is verb - topic - focus. There is no role marking of post-verbal NPs, so identification of actor and patient in transitive clauses relies quite heavily on context.

The interesting thing about this word order pattern is that, in the generally pragmatically unmarked predicate (VO) focus, the focus domain is split. The verb is fixed initially and may or may not be in focus, then you have some partly backgrounded material, then you have whatever argument is most foregrounded / focal at the end.

The language also, like many verb-initial languages, allows fronting to the immediately pre-verbal position for contrastive argument focus as part of a cleft-like construction, and it allows left-dislocation of topical arguments. You might recognise this general pattern from both Mayan and from my Ch’ubmin proposal above.

So my idea was to combine two basic principles:

Approximate default word order of V topic focus, i.e. VSO by default, but invertible to VOS under marked information structures like subject focus or thetic (entire clause) focus.

Case marking of the subject by fe’ or its fused determiner forms bel~ben~ber if and only if the S is in focus: i.e. in the inverted VOS transitive word order, or when a transitive patient is omitted or extracted but the agent is overt, or when an intransitive S is markedly focal (although maybe with a higher barrier in the intransitive case?)

This could approximately be thought of as a kind of word order or dependent marked passive, with information structure deficient subjects being marked by an oblique case marker even though verb agreement remains unchanged.

For example, with both arguments present:

transitive verb, absolutive subject, absolutive object

predicate (VO) focus

išaq' in tacha' in ch'om o'

3.PFV-grab DET man DET stick DEM

`The man grabbed the stick'

`The man grabbed the stick'

transitive verb, absolutive object, nominative subject

moderate subject focus or thetic/clause focus

išaq' in ch'om ben tacha' o'

3.PFV-grab DET stick NOM.DET man DEM

`The man grabbed the stick'

`The man grabbed the stick'

`The man grabbed the stick'

And with one argument omitted:

transitive verb, absolutive object

predicate (VO) focus

išaq' in ch'om o'

3.PFV-grab DET stick DEM

`He grabbed the stick'

`He grabbed the stick'

transitive verb, nominative subject

moderate subject focus or extracted / topical object

išaq' ben tacha' o'

3.PFV-grab NOM.DET man DEM

`The man grabbed it'

`The man grabbed it'

None of this would affect the preverbal domain, because I assume that the mechanisms that produce pre-verbal NPs, namely left dislocation and clefts (technically a kind of inverted pseudo-cleft), resist pied piping. Compare the English:

*As for by the man, the stick was grabbed

*By the man was the one who grabbed the stick

And actually this is, again, attested. Languages with some kind of case marking but a no case before the verb rule include Semelai (the actor marker la= is used post-verbally), and a number of African languages with marked nominatives or ergatives, whose argument fronting construction historically came from clefts like Päri, Teso, Shilluk, Dinka, Baale, etc. See Case in Africa by König for more details.

Hesitation and Concerns

I guess the main reason I’m not sure about this is because it feels busy. It combines:

Left-dislocation of topics

Argument focus via cleft-like fronting

More moderate information marking and role marking via a combination of post-verbal word order and presence/absence of an ergative / marked nominative preposition

On the other hand, having multiple devices to mark information structure distinctions is maybe not so unusual. As I described above, a number of verb initial languages have the first two (dislocated topics + pre-verbal foci), plus post-verbal word order sensitive to some kind of pragmatic concerns, plus other devices. Alto Perené lacks any kind of core case marking, but it does have special focus pronouns and markers which can be used to mark pragmatic distinctions.

The Alternative

The alternative would be either approximately fixed word order no case marking, which also provides role disambiguation because you can always add a pronoun instead of using zero anaphora if you need to clarify a transitive clause, or flexible order no case marking.

For the no marking case, Alto Perené seems to get by relying mostly on context, although verbal marking does distinguish the role of extracted contrastive foci.

For the rigid case, excluding topic/focus fronting, both rigid word order options are easily attested. In Mayan alone, Mam is rigidly VSO, whereas many other members of the family are reported to be either rigid VOS or VOS dominant with some flexibility, although in all cases zero anaphora is widespread.

Anyway, what do you all think?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hi again :D!

"Hola a todos. Hoy está es el segundo día de mi intento de escribir más en español. En el trabajo, escucho a los podcasts en español para ayudarme mejorar mi habilidad a de escuchar y comprender. También, intento hablar más con la gente de del trabajo quien que habla español . Hay mucha, pero tengo miedo porque no me gusta hacer cometer errores porque me siento tonto. Pero ahora, necesito practicar tanto como puedo pueda durante les las próximas tres semanas.

Empecé a buscar por información de los vuelos, trenes, y hoteles que necesitaré para llegar a España. Cuando estoy esté allí, quiero hacer amigos nuevos con quienes conocer la ciudad y especialmente la universidad. Quiero estudiar idiomas y lingüísticas lenguas (?), y encontré una un programa de esta universidad cuando tenía quince años . Me gustaría ser antropólogo lingüístico, pero me conformaría con ser profesor de inglés.

Si quieres ayudarme con mi español, para corregir errores o hazme hacerme preguntas en español, hazlo por favor."

"Hola a todos" the preposition "a" is required ("hello to everyone).

Wrong transitive verb, "ser", not "estar".

"Intento de escribir" the preposition is required, because "intento escribir" means "I try to write".

"Escucho podcasts" here you don't need the preposition or the article. The gender of the article was correct, tho, podcasts is masculine. Idk how to explain this one lol sorry. Sometimes you need the preposition + article and sometimes not, I have not found a clear explanation to when you do and when you don't.

"Habilidad de escuchar" wrong preposition. "A" = to ("de Madrid a Sevilla" = from Madrid to sevilla). "De" has several different uses, here it's working like "for" (ability for listening).

"Del" is a contraction of "de + el" (preposition "de" + masculine article "el"). "Gente de el trabajo" (not contracting it is incorrect tho).

"Que" and "quienes" (without the tilde) are both relative pronouns that are used to link sentences with a comon subject, but in this case "que" is the correct one. I haven't been able to find out why exactly, but with "quien" the sentence would be consturcted slightly diferent.

In Spanish you don't "make" mistakes, it's a collocation thing. (Beware, "cometer" =/= commit).

"Me siento tonto" here you need the reflexive pronoun.

Ahh yes, the subjunctive. "Pueda", besause it's a desire, not and objective (so to speak) action.

The definite articles are "el, la, los, las", "les" is not correct.

The preposition "a" is needed for the structure of this periphrasis: Verb "empezar" conjugated + a + verb in infinitive. (Empecé a comer, empiezan a jugar). It's the equivalent of English pronoun + to star conjugated + verb in -ing form (I started searching, they started playing).

We don't "search for information" we just "search information".

Wrong tense. "Estoy" is present of the indicative (presente del indicativo), but here we would use the present of the subjunctive (presente del subjuntivo). It's because you are talking about what you expect to happen. The subjunctive is it's own can of word worms.

"Amigos nuevos con quienes" here you need the preposition "con" (with).

"Lingüísticas" is an adjective, so we wouldn't use it here like a noun, but I'm not entirely sure what you are referring to.

Wrong gender, "programa" is masculine (absurd, I know).

"Ayudarme con mi español" without an adjective this sentence feels off, what spanish?

Because this is a subordinate clause and you are listing separate actions (you are not describing cause - efect), you want to keep the tense the same. "Ayudarme" is in infinitive (ayudar), but "hazme" is imperative.

Hope that was helpfull! If you have any questions I'm happy to answer!

Hola todos. Hoy está el segundo día de mi intento escribir más en español. En el trabajo, escucho a los podcasts en español para ayudarme mejorar mi habilidad a escuchar y comprender. También, intento hablar más con la gente de trabajo quien habla español . Hay mucha, pero tengo miedo porque no me gusta hacer errores porque siento tonto. Pero ahora, necesito practicar tanto como puedo durante les próximas tres semanas.

Empecé buscar por información de los vuelos, trenes, y hoteles que necesitaré para llegar a España. Cuando estoy allí, quiero hacer amigos nuevos quienes conocer la ciudad y especialmente la universidad. Quiero estudiar idiomas y lingüísticas, y encontré una programa de esta universidad cuando tenía quince años . Me gustaría ser antropólogo lingüístico, pero me conformaría con ser profesor de inglés.

Si quieres ayudarme con español, para corregir errores o hazme preguntas en español, hazlo por favor.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you help me with el que, la que lo que,los que,las que and el cual,la cual,lo cual,los cual,las cual.

What you’re talking about are “relative clauses”, and they’re much simpler than you’d think

The equivalents in English are “that” and “which”. This is because they’re related to the question words qué “what” and cuál/cuáles “which / which ones”

Secondly, this might help make it a little simpler:

el que = el cual

la que = la cual

lo que = lo cual

los que = los cuales

las que = las cuales

How it works is similar to English. You normally say “that”, but in formal or fancy situations you’d say “which” (or “whom”)

You use a relative clause in the context of adding some side description in your sentence. It’s called “relative” because it “relates” to the subject you just mentioned:

La mujer que conozco. = The woman that I know. La mujer que me dio el libro. = The woman that gave me the book.

La mujer que conozco, la que me dio el libro, es mi vecina. = The woman I know, the one that gave me the book, (she) is my neighbor.

El hombre que tiene traje puesto... = The man in the suit... El hombre alto y calvo... = The tall bald man...

El hombre alto y calvo, el que tiene traje puesto, es mi jefe. = The tall bald man, the one wearing the suit, (he) is my boss.

The use of el cual or la cual is more typically done with inanimate objects and it implies more distance and gets used as “which”

Motivo por el cual... = The reason for that / The reason for which / The reason being...

Razón por la cual... = The reason for that / The reason for which / The reason being...

Los países con los cuales cooperamos... = The countries with which we cooperate

Las empresas a las cuales se refiere... = The companies which are being referred to...

Los problemas de los cuales hablamos... = The problems we are talking about... / The problems of which we are speaking...

Los medios mediante los cuales obtenemos nuestra información... = The media by which we obtain our information...

La mesa, encima de la cual... = The table, upon which...

El sofá, debajo del cual... = The sofa, underneath which...

And so on. The el cual, los cual, la cual, las cuales is really good for sounding authoritative and making a point because you sound fancy

...

Where it’s a little more in depth is lo que vs lo cual

The lo que [neuter gender] is used as a stand-in for something, so usually when you see “what” as a noun, that’s lo que. It exists in the absence of a noun, so it’s neuter/neutral gender or agender:

Lo que no entiendo... = What I don’t understand... / The thing that I don’t understand...

Lo que el viento se llevó. = Gone With the Wind. [lit. “what the wind took with it”]

Eso no es lo que quiero decir. = That’s not what I mean.

Lo que me molesta... = What bothers me...

lo cual isn’t that common but it’s used to refer to a thing or concept that was discussed earlier

El hombre llevó a alguien a cuestas, lo cual me resultó extraño. = The man gave someone a piggyback ride, which I thought was weird.

Y la otra estudiante mintió y me echó la culpa, lo cual me enfadó mucho. = And the other student lied and she blamed me, which made me really angry.

I personally would have used y eso instead of lo cual... like y eso me resultó extraño “and that was weird to me”

I don’t usually use or see lo cual that often, it feels very fancy

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

What’s In A Name? The Courtroom Drama Surrounding Spring Grove’s Dexter Mausoleum

Few visitors to Spring Grove Cemetery fail to admire the stately yet threadbare Dexter Mausoleum, monument to one of Cincinnati’s dominant whiskey dynasties. So focused are visitors on the grandly decaying sandstone edifice, tantalizingly enclosed by rusting iron gates and adorned by nesting birds, that they may be forgiven for ignoring the headstones scattered among the encroaching trees and shrubs.

One headstone, in particular, implores further investigation. This modest marker, lying flat to the ground, reads in its entirety:

CHARLES DEXTER

born

CARROLL DEXTER WALKER

1906 – 1960

Charles Dexter, aka Carroll Dexter Walker, was the great-grandson of Edmund Dexter Sr., patriarch of the Cincinnati clan. Born in England, Edmund arrived in Cincinnati around 1830 and, after a very brief stint as a grocer, opened the liquor distribution company that generated his fortune. Edmund died in 1862, aged 61, and became the first interment in his new Dexter Mausoleum. Edmund left behind five sons, with three remaining in Cincinnati and retaining some connection to the family business. Edmund’s son, Charles, though initially involved in the business, suffered a series of infirmities and spent most of his life in the library of his Walnut Hills estate. He died in 1893, leaving a substantial inheritance to his three daughters, Annie, Mary and Alice.

Alice was the only daughter to marry. Mary died young and Annie, a quite eccentric character, lived most of her life in France, refusing to speak English. Alice married Paul F. Walker, a professor of Spanish at the University of Cincinnati. Alice’s only child was Carroll Dexter Walker. Or, he was Carroll Dexter Walker until his Aunt Annie died in Quebec in 1916.

When Annie’s will was read in Hamilton County Probate Court, it was discovered to contain the following bequest:

“I give, devise and bequeath to my nephew, Dexter Walker, the sum of twenty thousand dollars ($20,000) to be held for him in trust by my executor, the income therefrom to be paid him quarterly, for the use and benefit of my nephew's education, until he shall reach the age of twenty one years, when said amount shall be paid over to him for his own property, provided, he be willing to assume by law, the name of Charles Dexter, instead of Dexter Walker as he is now known.”

Annie intended to maintain her father’s legacy. Since Charles Dexter had no sons, and since two of his daughters had no children, Carroll was the only candidate to continue the Dexter line, but only if he changed his surname to Dexter. Should Carroll decline to comply with her request, the $20,000 would be redirected to the University of Cincinnati to create an endowment fund in her father’s name.

Annie’s sister Alice went apoplectic at her sister’s maneuver. From Alice’s perspective, Annie’s scheme was nothing short of a brazen attempt to steal her only son. From the grave, Annie communicated her utter disregard for Alice’s feelings. The very next clause in her will reads:

“To my Sister, Alice Dexter Walker, I leave nothing, for she has never shown me any affection.”

If Annie intended to piss off Alice, it worked. Alice spent the remaining 28 years of her life working to destroy all of Annie’s post-mortem intentions.

Alice mounted a full-scale assault on Annie’s will, trying every method she and her team of lawyers could imagine to get it thrown out. Alice claimed the will was void because Annie was not a resident of Hamilton County, that she was of unsound mind, that her requests were illegal, and so on. None of Alice’s objections survived legal scrutiny, and there is some evidence that the court found her to be a dreadful pain.

Carroll, meanwhile, took his time complying with his aunt’s demand. He was only 10 when Annie died. He turned 21 in 1927 and, when he did not immediately change his name, the University of Cincinnati pounced, claiming the $20,000. UC won the first round but, on appeal, the court ruled that Carroll’s aunt had not set time limit for changing his name. UC appealed that decision. The Ohio Supreme Court, however, determined that Carroll could change his name whenever he damn well pleased. He promptly did so, collected $20,000, and lived the remainder of his life as Charles Dexter. His friends called him “Dex.”

Another item in Annie Dexter’s will created a quandary for the executors. It read:

“I give and bequeath to the Spring Grove Cemetery Association, the sum of five thousand dollars ($5000) and direct that the income therefrom be used for keeping in good repair the Dexter Mausoleum in Spring Grove Cemetery.”

That appears to be a simple matter, cut and dried, and who would refuse $5,000? Spring Grove Cemetery did. Seven years after Annie’s death, executor Burton P. Hollister was still trying to get Spring Grove to accept the gift, but they steadfastly refused to accept the money, even though Hollister himself sat on the cemetery’s board of directors.

According to Spring Grove historian Phil Nuxhall, on 9 October 1924, the Spring Grove directors deferred action on a request by Alice Dexter Walker to demolish the Dexter Mausoleum entirely, referring the matter to – of all people – Burton P. Hollister for analysis.

As if she needed the money, Alice charged into court claiming the $5,000 rejected by Spring Grove. She found Harvard University ahead of her in line. Annie’s will named Harvard the beneficiary of any “residue” or assets not otherwise specifically bequeathed to an individual or organization. Harvard said the refused funds had become part of the residue. Alice claimed they returned to the estate and were therefore hers, as Annie’s only living relative – despite having been personally and unmistakably disinherited. Harvard won that round, pocketing an endowment while the Dexter Mausoleum deteriorated.

Alice Dexter Walker laid down her earthly burdens in 1944, leaving her entire estate to her son, no matter what name he answered to at the time. You can tell from the language of Alice’s will that she was still fuming:

“Throughout this instrument I have referred to my son by his baptismal name of Carroll Dexter Walker, realizing that he assumed by law the name Charles Dexter and is now known as such. I hereby direct that the benefits of this instrument shall inure to my son whether he be described by his baptismal name of Carroll Dexter Walker or by his assumed name of Charles Dexter.”

#spring grove cemetery#dexter mausoleum#charles dexter#edmund dexter#annie dexter#alice dexter walker#carroll dexter walker

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Relative Clauses (Oraciones relativos) with Indicative in Spanish

Introduction Relative clauses, or oraciones relativos, are an essential part of Spanish grammar. They allow us to provide additional information about a noun without starting a new sentence. When combined with the indicative mood, relative clauses are used to express factual or certain information. Understanding how to use them correctly can significantly improve your fluency and comprehension…

#100 example sentences#A1#A2#B1#B2#blog#C1#C2#daily prompt#DELE#dios#English#espanol#indicative mood in Spanish#Japanese language learning#latin america#Learn Spanish Online#learning Spanish grammar#mexico#My English class#My Japanese class#my language classes#My Spanish class#oraciones de relativo#relative clauses in Spanish#siele#spain#Spanish#Spanish grammar blog#Spanish grammar cheat sheet

0 notes

Note

Hello there! I was wondering if you could possibly translate this quote: (I know it's a different fandom, but I was wondering if you could translate it anyways. I think it would be neat to see it in High Valyrian.)... "Not all who wander are lost."

So listen… I know this wasn't the intent, and I know that you're kind of standing in for tons of people from my past, but like… When people ask to have something translated, do they really not give any thought to the grammatical complexity of what they're asking for? And 100% this is not just you, but like… Embedded clauses, relative clauses, counterfactuals…

Something I didn't realize till I started creating languages for a living is translation is my least favorite part of language creation—and it's what I spend the most time doing.

Okay, so, "Not all who wander are lost". Good lord. First, there's "lost", which has a literal and metaphorical meaning in English. Absolutely no idea if this would translate in High Valyrian, and I'm pretty sure I don't have a word for "lost", and I don't even know how to go about creating one. Spanish perdido essentially comes from "wasted" or "squandered". We know where English "lost" came from. There actually is a word for "to lose" in HV, but it's to lose a battle. Doesn't make sense to use it here. So I'm going with something that kind of evokes that mists that surround destroyed Valyria and use the locative of "fog", so to be sambrarra "in the fog" means "to be lost".

I also don't (or didn't) have a word for "wander", but I made a derivation based on one of my favorite words, elēnagon, which means to oscillate or swerve. Jorelēnagon now means "to wander". Seems to fit.

And that was the easy part. A relative clause is something like "The dragon that I saw is big". "Whoever I saw is big" also features a kind of relative clause—an indefinite relative clause. These things are absolute murder to create. But no. It's not just that. It's a modified indefinite relative, because it's not "Whoever wanders is lost", it's "All who wander are lost". BUT IT'S NOT JUST THAT. It's negated on top of that. NE. GA. TED. And not just in the usual way: It's the Mothra fumbling quantifier that's negated. It's not whoever wanders. It's not all who wander. It's NOT ALL who wander. This is like my nightmare—being asked to translate something like this. This is giving me flashbacks to season 1 of House of the Dragon when they asked me to translated "Would that it were", as if that was some reasonable thing for a human being to say in any language ever.

Anyway, if you type "indefinite relative clause" into my High Valyrian grammar, you come up with nothing, because I always forget to write down how the hell I decided to do them. I think because I have both relative adjectives and pronouns that I can just use the damn pronouns by themselves. God. "Not all…" Are you kidding me?! You know High Valyrian has a whole collective number to handle "all", right? What, do I just negate that? Will the meaning be the same as a negated quantifier?! Like it's [[not all] who wander], right? And you can bracket like that because they're all separate words. But what if "all who" is one word? What then?! BECAUSE THAT'S WHAT IT IS!

(By the way I just added a sentence to my grammar that includes the phrase "indefinite relative clause" so I can search for it. It's not like this wasn't written up, but I honestly probably forgot what the term was when I wrote the section the first time and I never revisited it.)

Okay. I'm calm and cool. So. Returning to the translation. There are two types of relative pronouns: One that refers to people or things, and another that refers to concepts or ideas or places. We're talking about people here, so we need the first one. And we need it in the collective. That's lȳr. Leaving the negation aside, this can be translated fairly easily:

Jorelēnus lȳr sambrarra ilza.

Okay, that's "All who wander are lost". I chose the aorist subjunctive for the relative because it's like "anyone who may wander"; I think it makes sense. Lȳr is grammatically singular, so it triggers third person singular agreement in both verbs. Since we're using ilagon as a locative copula here, I think (think) the present tense makes the most sense. So that is "All who wander are lost".

Now how the flarking frump do you say "not all" when "all who" is lȳr?!

So since lȳr is a pronoun it can be modified with an adjective, which would like like this:

Jorelēnus dōre lȳr sambrarra ilza.

But the problem with that is I don't think it gives us the intended meaning. I think that means "None who wander are lost", and that's not what the intended meaning is at all. It is basically "Some people who wander are indeed lost—perhaps many of them—but some of those who are wandering are not, in fact, lost". This is also why you can't negate the matrix verb. That would mean "Anyone that might be wandering is not lost"—again, not the intended meaning. This is the crux of the whole translation: Negating the quantifier and not what the quantifier is modifying.

For that reason, the only thing I can think to do is to go to a much more prolix, and, frankly, un-Valyrian-like expression. This would mean taking the relative pronoun out of the collective, putting it back in the singular, adding in a quantifier, and negating it. That would be this:

Jorelēnus dōre tolvie lȳ sambrarra ilza.

Is that it? I honestly don't know. It is a translation; I'm not sure if it's the best translation. Another possibility is to re-translate it and say "A few who may wander are not lost". That would look like this:

Jorelēnusy lȳn sambrarra ilosy daor.

The pronoun is now in the paucal, which triggers plural agreement on both verbs. (And, by the way, thank goodness sambrarra is a noun phrase; it doesn't have to agree with anything!) And this is, basically, "A few who may wander are not lost".

I feel like the second translation is better maybe…? It feels more Valyrianesque. But I'm not 100% sure it conveys the same sense.

Anyway, I started translating this a little over two hours ago. That's what this takes. That's how long something this complex takes. Granted, it didn't have my full attention at all times, because I was watching Booksmart, but this was my second time watching it, so I didn't have to give the movie my undivided attention (though it had been a few years; there were bits I didn't remember). But yeah. Translation. My god. Like…why. Creating languages is fun. Translation is work. (And if it's not work, you're doing it wrong. Mic drop; soap box kicked.)

#conlang#language#valyrian#high valyrian#valyrian grammar#grammar#high valyrian grammar#translation#asoiaf#grrm#hbo#hotd#house of the dragon#got#game of thrones#all the flipping tags#booksmart

477 notes

·

View notes

Note

So sorry if you've answered this, but is Dai Bendu similar to Spanish in that there's a different conjugation for gerunds? Like, would the sentence "I like running" and "I like to run" be the same, or different? Thanks!

No need to apologize, we love questions! And yes, they’re different!

Komlah foh kan would be “I love to run” while Komlah foh nev kanyth’ak would be “I love (the) running”.

The first one contains a non-finite clause - “I love” and “to run” being two clauses of which the first one is tensed and the second isn’t.

The second has nev kanyth’ak as the accusative object of the verb. This is only one sentence!

So while both sound relatively similar, they actually have a very different syntax :D

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vittoria Accoramboni and a Renaissance Revenge Tragedy – Part 3

Part 1

Part 2

Last week we have heard about Cardinal Montalto’s rough past. However, those youthful escapades were as nothing compared to the nature of the man who came to court his niece-in-law Vittoria.

Paolo Giordano Orsini, the Duke of Bracciano and one of the most powerful men in Rome, was smitten with Vittoria from the evening he first saw her, her finery valiantly cobbled together from her family’s modest resources. If there was any danger of him consigning her to the heap of the many lovely infatuations he’s had since his wife died in suspicious circumstances (more on that later), Vittoria’s brother Marcello was ever ready to work on his mind.

Marcello had to flee Rome after stabbing the brother of Cardinal Pallavicino in one of the scuffles young bloods of Italy engaged in when wearing a sword on the street was normal for everyone who could afford it. Then the young man went straight to Castle Bracciano to enroll into Paolo Giordano’s unofficial private army, and set to work talking about his sister’s beauty, as well as the misery of her reduced circumstances, straight away. Her husband Francesco Peretti might have counted Marcello as a friend – but for the latter, as for all Accorambonis, family ambition was above all. In this particular case, it was even understandable – if Vittoria were to become a widow (out of completely natural causes, of course) and marry Paolo Giordano, they would become kin to one of the first families in Rome.

The Orsinis’ brilliant position was above anything Marcello, Vittoria, or their mother could have ever hoped for. The clan had eleven European queens in their family tree, two popes, and innumerable cardinals. In the present day, King Philip II of Spain referred to Paolo Giordano as his kinsman. They also had the dubious fame of having one of their ancestors, Pope Nicholas III, consigned by Dante to Hell for his corruption.

One could say that, even all this great pedigree aside, Paolo Giordano didn’t have much in common with Vittoria. If she was a dark and glimmering beauty, his fatness stemming from the life of excess was so great that ordinary horses couldn’t bear him. In September 1575, he had to write to Cardinal Antonio Caraffa with a request to send him one of the muscular bay mares from his stables, since no other steed could suffice. If Vittoria had an ambitious and determined mother dedicated to the wellbeing of her family, Paolo Giordano had been raised by a spendthrift uncle who had killed his father in an ambush, and his own mother left him with relatives in order to remarry when he was still a child. Vittoria was not exactly modest in her habits, but she knew the value of money; Paolo Giordano’s unthinking largesse, on the other hand, was proverbial. He managed to get deeply into debt by the age of sixteen, and remain there for all his life despite the opulence of his lifestyle.

And then, of course, there was the little matter of his first wife’s death.

Paolo Giordano had married Isabella de Medici when he was seventeen and she sixteen. Naturally, it was a political marriage – however, one expected that he is going soon to be smitten with his bride, who was dubbed ‘the fairest star of the Medici’ for her beauty and her intellectual accomplishments. Isabella spoke Spanish, French and Latin, and wrote poetry herself. However, Paolo Giordano preferred the low milieu of whorehouses; as for intellectual accomplishments, he did not consider them that much of an adornment for a woman. Isabella paid him back with the same coin, taking his lissome and courteous relative Troilo Orsini to be her lover. She bore Troilo two illegitimate children, whom her servants then placed discreetly in orphanages, as she could not be seen to raise them herself.

This relative freedom of conduct was facilitated by the curious clause in the marriage: although Isabella and Paolo Giordano were now man and wife, she was to remain at her father’s court in Florence, where her husband would visit her. It was during these brief visits that they managed to conceive their legitimate children: the daughter Leonora and the heir Virginio.

Isabella’s father, Duke Cosimo de Medici, had a good reason to maintain this state of affairs: Isabella’s dowry consisted of 50,000 gold ducats and 5,000 ducats in jewels, which today would have been amounted to $20 million. Naturally, Cosimo didn’t want this vast sum to find its way into the hands of a man who would rather die than live within his means. Isabella was completely satisfied with the situation, and only wished her unwanted husband’s visits were even rarer.

However, this situation could only last while Duke Cosimo lived. Isabella’s brother Francesco (whom, to avoid confusion with Vittoria’s husband, we are going to be calling the Grand Duke from now on), who ascended the ducal throne after his father died, had no desire to protect her. If anything, he must have been somewhat gleeful that his brilliant sister, who has always overshadowed him both in the public life and in their father’s affections, would finally get what’s coming to her. Paolo Giordano couldn’t agree more.

Paolo Giordano took his wife to the villa of Correto outside Florence, supposedly to go hunting. She never left the villa alive.

According to the official version he put out afterwards, she suffered a heart attack while washing her hair. People were understandably reluctant to believe that about a healthy thirty-three-year-old. The Ferrarese Ambassador Cortile produced a completely different report. Isabella was strangled by her husband behind a bolted door, he claimed; or, rather, by an assassin named Massino, a Roman Knight of Malta, who was hiding under the bed at Paolo Giordano’s orders. Later that year, the same Massino killed the late Isabella’s lover Troilo, again at his master’s behest. The fact that Troilo was also an Orsini mattered not – personal pride and masculine honour were at stake.

That little detail of Paolo Giordano’s biography should have made Vittoria and her family at least pause. However, if they did, no historical record of them doing so survives.

To them, the greatest difficulty of all was the fact that Francesco Peretti was still annoyingly alive. However, that was the difficulty that Paolo Giordano was about to remedy.