#reede imperial

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I decided to be funny and make this

Based on this, and also this

Also a good visual for Link and Reede's scene in the first link.

#low effort meme#hyrule's final stand#legend of zelda#tears of the kingdom#link imperial hyrule#reede imperial#reede totk#the imperial family hfs#link wolfbred king#not shown: zelda ivee hyrule#link is a wee bit grumpy right before TOTK#and a lot bit grumpy after zelda goes *poof*

1 note

·

View note

Text

#relevant#Palestine#history#Palestinian history#us politics#antisemitism#antisemitic#immigration#fascisim#indigenous#end the occupation#stop occupation#Johnson-Reed Act#Relatives Rule#immigrants#Ellis Island#colonialism#imperialism#empire

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#thirteen#thirteen original motion picture soundtrack#thirteen movie soundtrack#thirteen 2003#2000s#2003 film#characters#vivid#evan rachel wood#nikki reed#brady corbet#music credits#katy rose#imperial teen#y2k

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

God the fucking punchline made it all so perfect. just crazy, crazy good. Messy messy messy MESSY season which didnt all work but: lol. lmao. And sally. Oh, my darling sally....... Main character sally

#i won like no one's ever won before.#barry spoilers#barry won. which is the hilarious tragedy. barry's image won#but sally got out. Guys she fucking got OUT#in short order i will be going through the entire fake movie piece by piece because it's the funniest thing ive ever seen#The shows alsays been about this. American imperialism. Media. Male violence. And Sally Reed#barry#it’s always been HERRRRRRRR

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

ℜ𝔢𝔩𝔦𝔤𝔦𝔬𝔫 | chapter I

General Marcus Acacius x f!reader

"in her eyes shone the sweetness of melancholy."

summary: In the grandeur of ancient Rome, you are the secret daughter of Commodus, living a quiet life as a servant in the imperial palace. Everything changes when you meet General Marcus Acacius, Rome’s honorable and stoic leader.

Though devoted to duty and loyalty to the princess, Marcus is drawn to you in a way he cannot ignore. A forbidden passion ignites between you both, and an affair begins—one that threatens the very foundation of loyalty, power, and honor. As you fall deeper into your dangerous love for Marcus, each stolen moment becomes a fragile, dangerous secret.

warnings: 18+ only, 14 YEARS AFTER GLADIATOR 1, ANGST, Fluff, A LOT OF SMUT, Unprotected Sex, Exhibition Kink, Age-Gap, Ancient Rome, mentions of violence, Gladiators, Blood, Gore, Politics, Sexism, Forbidden Love, Loss of Virginity, mentions of death, Innocent and pure reader, Loss of virginity, Infidelity, more warnings will be added throughout the story

Chapter I

masterlist!

next | chapter II

The palace is alive with preparation, a beast of marble and gold that never rests. Its veins are the labyrinthine halls, pulsing with servants like you, carrying trays of delicacies, wreaths of flowers, and jugs of wine.

Its heart beats to the rhythm of whispered orders, clinking metal, and the distant echo of the marketplace beyond its gates. Tonight, the beast awakens for another feast.

You adjust the folds of your simple tunic, careful not to brush against the elaborate tapestries that line the walls. Each thread tells a story of conquest, glory, and power—legends you’ve only heard murmured by those old enough to remember.

You are not part of those tales, nor their lineage. You are a servant, a shadow cast by the towering figures who walk these halls.

The kitchen is a tempest. The air is thick with the scent of roasted meats, fresh bread, and sweet figs. Claudia, the head cook, barks orders, her voice slicing through the chaos like the edge of a Roman gladius.

You pass her with a nod, your arms laden with trays of fruit—gleaming apples, plump grapes, the kind of bounty the common people outside these walls could only dream of.

Livia catches your eye from across the room. Her presence is a steady anchor in the storm, her face worn but kind.

“Have you checked the wine?” she asks, her tone soft but urgent.

You nod. “It’s ready, Mother,” you reply, the word slipping out as naturally as breath.

She is not your mother—you know this much—but she is all you have.

The story of how you came to be here is one you’ve heard countless times: a baby abandoned at the servants' chamber door, cradled in a basket of woven reeds, with nothing to mark your origin save for a scrap of fine cloth that no one in your station would dare to own.

Livia found you there, swaddled in whispers of mystery, and against all odds, she chose to keep you.

Raised among the laboring hands of the palace, you were given no privilege beyond survival and no legacy but that of work.

The great marble halls and gilded frescoes became your entire world, a place as eternal and unmoving as the gods themselves—or so it seemed.

The servants’ quarters where you lived were nestled in the hidden bowels of the palace, far from the glittering feasts and marble statues.

You learned to scrub floors and pour wine long before you understood the language of wealth and power that filled these walls.

Your life had been carved out in the shadows, molded by the soft voices and calloused hands of those who raised you.

Today, like every other, begins in service to Rome's ever-churning hunger for spectacle.

The air hums with anticipation, thick with the scent of roasted meat and spiced wine, a stark contrast to the stench of poverty that lingers just beyond the palace gates.

“Are the platters for the atrium ready?” Livia’s voice cuts through your thoughts.

“They are,” you reply, glancing at the polished silver laden with grapes and apples, their skins shining like jewels under the torchlight.

“Good.” Livia’s sharp eyes soften, though her expression remains tense. “Take the fruit out yourself. And stay close to the kitchen. Today will bring trouble, I feel it.”

You nod, understanding the weight of her instincts. Years of serving in the palace have taught her to sense the storm before it strikes.

As you lift the platters, Claudia, calls over her daughter, Alexandra.

“Go with her,” Claudia orders, waving a ladle for emphasis.

Alexandra groans dramatically but obeys, rolling her eyes as she grabs one of the platters.

“She can’t let me rest for a moment,” she mutters, her tone more amused than annoyed.

You chuckle softly. Alexandra has always been like this—bold where you are cautious, quick to speak where you stay silent.

She is your only true companion here, older by four years and infinitely more daring.

As you and Alexandra arrange the fruits on a grand table in the atrium, she leans closer, her voice dropping conspiratorially. “The Princess will be here tonight.”

You nod absently, focused on ensuring the grapes cascade just so. “Of course, she will. She is the Princess after all.”

“No, I mean, I haven’t seen her in years,” Alexandra continues, ignoring your tone. “Not since I was a kid. That was ten years ago. You know she moved out of the palace after marrying the general.”

You don’t reply immediately, your hands steady as you arrange the fruit. Alexandra has always loved to gossip, but you prefer to keep your thoughts unspoken.

“Can you believe it’s been ten years, and she hasn’t had a child? Not one with him,” Alexandra muses.

“Maybe it’s their choice,” you say quietly. “It’s not our place to wonder.”

Alexandra scoffs lightly. “I’m just saying, after her son—what was his name? Lucius?—after he was taken and killed by her brother, Commodus…” She trails off, her voice tinged with something between pity and fascination.

You remember Lucius vaguely, a boy with a quiet demeanor and a sad smile.

You were too young then to understand the weight of his loss, but the servants whispered of curses and tragedies surrounding the imperial family.

“It’s not good to talk about the great emperors like that,” you murmur, hoping to steer the conversation elsewhere.

Before Alexandra can reply, the sound of heavy boots echoes through the atrium.

The guards step forward, their polished armor glinting in the firelight. “Make way for their majesties,” one announces, his voice carrying over the growing murmur of the guests.

You and Alexandra immediately bow your heads, the platters forgotten as the twin emperors enter the room.

Emperor Geta and Emperor Caracalla are a study in contrasts.

Geta, an imposing figure, commands the space with a cold and calculating gaze. His every step seems deliberate, as if the weight of the empire rests on his shoulders alone.

Caracalla, by contrast, walks with an erratic energy, his pet monkey perched on his shoulder. Dondus, the creature’s name, chatters and hisses, a mirror of its master’s unpredictable moods.

You feel the weight of their gazes as they sweep the room. Geta’s lips curl into a smile—or is it a smirk?—as his eyes linger on Alexandra.

There have been whispers, rumors of an affair, though Alexandra denies them with a laugh.

Caracalla’s gaze lands on you, and for a moment, his expression softens. Unlike his brother, he has always been strange but oddly kind to you.

When you were a child, he would find you in the halls, offering you small trinkets or asking you to keep him company.

“Your Majesties,” Alexandra says again, her voice like honeyed wine, sweet but strong.

She curtsies with practiced ease, her eyes cast downward, yet her boldness hangs in the air, unspoken but palpable.

You follow her lead, bowing deeply, but your heart pounds in your chest like the war drums of a distant legion. In the presence of the emperors, the room feels smaller, the air heavier.

To serve Rome, you think, is to breathe in the will of its rulers, no matter how suffocating.

Geta's gaze lingers on Alexandra, traveling from her head to her feet, as though she were a statue he might commission or a possession he already owns.

His smirk deepens, the corner of his mouth curving with an indulgence that unsettles you.

“Alexandra,” he drawls, his voice smooth as polished bronze. “Why do I find the table half-dressed? Are my guests to dine on the promise of fruit alone?”

You glance at the platters, perfectly arranged but not yet fully adorned with the remaining dishes. Your pulse quickens; you know the punishment for displeasing the emperors can be swift, unpredictable.

But Alexandra, bold as always, doesn’t flinch.

“Forgive us, Your Majesty,” she says, her tone measured yet edged with defiance. “The final trays are being brought out as we speak. The delay was unforeseen.”

Geta arches a brow, his smirk turning sharper, more dangerous. “Unforeseen,” he repeats, as though savoring the word.

“I wonder, Alexandra, if you’ve grown too accustomed to... distractions.”

You know the meaning behind his words. Everyone does.

The whispered rumors of their affair swirl through the palace like incense smoke, clinging to every corner.

Her mother Claudia knows, though she turns a blind eye, perhaps thinking it wiser not to provoke the wrath of an emperor.

Beside him, Caracalla shifts, uninterested in the exchange. His pet monkey, Dondus, chitters softly on his shoulder, its small, beady eyes scanning the room.

Caracalla’s gaze falls on you briefly, but it is not unkind. He has always been more erratic than cruel with you, there is a peculiar understanding in his glances—a shared knowledge of solitude.

“Forgive us, Your Majesty,” you say suddenly, your voice trembling like a bird caught in a net. The words tumble out before you can stop them, and the weight of the room shifts.

Geta’s eyes snap to you, sharp as a blade. For a moment, you wonder if you’ve made a grave mistake.

But then he laughs—a low, indulgent sound that sends shivers down your spine.

“Ah,” he says, leaning slightly toward you. “The little dove finds her voice. How curious.”

You stiffen under his gaze, your knees threatening to buckle. It feels as though he is peeling back your very skin, seeking something hidden beneath.

“You’re the youngest servant here, aren’t you?” Geta muses, his tone light but with an edge that cuts.

“A curious creature, so quiet and unassuming. And yet…” He trails off, his eyes narrowing, as if piecing together a puzzle.

The weight of unspoken rumors presses against your chest.

The whispers about your lineage, the murmurs that you are more than a servant—that you are the illegitimate daughter of Commodus himself, a shadow of Rome’s bloody past.

You’ve heard them before, though never directly. Livia, your steadfast mother in all but blood, dismisses them as lies, the gossip of bored tongues.

But in moments like this, when Geta’s piercing gaze locks onto yours, it feels as though the marble walls around you whisper secrets only they can hold.

Secrets of your origin, of what blood may or may not flow through your veins, encased in the silent austerity of Rome’s cold embrace. You feel the weight of it, a shroud both invisible and suffocating.

Geta doesn’t believe the rumors entirely, but he cannot ignore them either. To him, you are a thorn he cannot pluck without proof.

If the whispers are true, if you are indeed the hidden scion of Commodus and the only living grandchild of Marcus Aurelius, you would be a danger to his rule.

Rome, after all, has loved its Aurelius lineage fiercely.

The plebeians would rally to your name like vines twisting toward sunlight.

Still, no woman has ever ruled Rome.

The Senate, the soldiers, and the gods themselves would balk at such a notion. But Geta knows that power is not always rooted in precedent—it is rooted in the hearts of the people.

And the people would love a descendant of Marcus Aurelius far more than they could ever love him.

“You wear the palace well,” Geta says finally, his tone dripping with mockery. “A little too well, perhaps.”

You feel the heat rise to your cheeks but keep your gaze respectfully lowered. His words are like serpents coiling around you, their venom lying just beneath the surface.

Caracalla hums softly, breaking the tension. He strokes Dondus, the little monkey perched on his shoulder, as though soothing himself rather than the animal.

“Leave her, brother,” he mutters, his tone flat but carrying weight. “You scare the child.”

Geta casts his twin a glance, his smirk briefly faltering. With that, he straightens, clapping his hands once in finality. “Finish the table,” he commands, the sharpness of his tone slicing through the room.

“Yes, Your Majesty,” you and Alexandra reply in unison, bowing deeply as the emperors turn and walk away.

Their robes ripple like molten gold, catching the light as though the gods themselves had woven the fabric.

The moment they are gone, you exhale shakily, the breath you didn’t realize you’d been holding slipping from your lips.

The grandeur of the palace, so often a thing of wonder, now feels oppressive—a prison of marble and ambition.

Alexandra nudges you gently, her smile faint but reassuring. “It’s fine,” she murmurs, though the tightness in her voice betrays her unease.

You nod and return to your work, the routine motions of arranging platters grounding you once more. But the unease lingers, like a storm cloud that refuses to dissipate.

Later, after the feast preparations are complete, you retreat to the servants’ quarters. The hallways grow quieter as the palace begins to prepare for the night’s debauchery.

Your mother, Livia, finds you there, her expression tight with concern.

“Are you all right?” You nod quickly, not wanting to worry her further.

Livia’s sharp eyes search yours for a moment before she exhales heavily. “Stay away from them tonight,” she warns. “There will be soldiers, senators, politicians—men who think they own the world. And women and men from the brothels to entertain them. It will not be a place for a child like you.”

“I understand,” you say softly, though the thought of the gathering makes your skin prickle.

"Go to your chamber and stay there.” You nod, obedient as always, and Livia cups your face briefly before bustling away.

But as you walk toward your chamber, the stillness of the afternoon draws you elsewhere.

***

The sun bathes the palace gardens in a golden light, soft and warm, like an embrace from the gods themselves.

The sky is a flawless stretch of azure, and the air carries the faintest scent of blooming jasmine.

Unable to resist, you veer toward the gardens, seeking solace in their quiet beauty.

You make your way to the small pond at the edge of the grounds, where the world feels simpler, untouched by the weight of marble columns and imperial decrees.

This is your sanctuary, a place you’ve tended with your own hands.

The hedges are trimmed neatly, the flowers arranged in bursts of vibrant color—crimson roses, golden marigolds, and pale violets that seem to glow in the sunlight.

The pond reflects the sky like polished glass, its surface rippling gently in the breeze.

You settle onto the cool stone bench nearby, pulling out a small parchment and charcoal.

Writing has always been your escape, a way to make sense of the labyrinth that is your mind.

The words flow from you like water from a spring, each line capturing fragments of your thoughts and fears.

To live in the shadow of gods is to forget the warmth of the sun.

You stare at the words you’ve written, sentences about Rome and its people, the empire’s endless hunger that devours the poor while the rulers gorge themselves on the spoils.

It isn’t rebellion that drives you—at least, not yet—but a quiet, gnawing sense of wrongness.

You have lived your entire life within the confines of this palace, its gilded walls both a sanctuary and a prison.

Outside, beyond the Forum and its grand marble temples, the streets of Rome teem with despair. You’ve seen it, fleeting glimpses on the rare occasions you ventured beyond the palace gates.

Children with hollow eyes and grime-streaked faces.

Men broken by war or taxation, their shoulders bowed under invisible yokes.

Women clutching bundles of rags that you realized, with a sick lurch, were infants too still to be alive.

These thoughts weigh heavily on you as you sit by the pond, the garden’s beauty unable to shield you from the world’s harsh truths.

You lower your quill, pressing trembling fingers to your lips, when the sound of approaching footsteps pulls you sharply from your thoughts.

You stiffen, the air in your lungs turning to stone. It isn’t one of the servants; their steps are lighter, quicker.

This tread is deliberate, measured, carrying a weight of authority. When you glance up, your breath catches.

The man before you is not adorned with the opulence of the Senate nor the ostentatious silk of the emperors.

You know who he is. How could you not?

General Marcus Acacius.

Rome’s shield and sword, the hero of distant campaigns whose name is whispered with both reverence and fear.

You have never seen him in the flesh, for he seldom resides in the palace, choosing instead to live with Princess Lucilla far from its labyrinth of intrigue.

But his likeness is everywhere: etched in marble statues, painted in frescoes, immortalized as Rome’s protector.

Yet, here he stands, and for a fleeting moment, you wonder if the gods themselves have sent him.

The crimson cloak draped over his broad shoulders glints faintly in the golden light, its hem embroidered with intricate patterns that seem to tell the story of the empire’s conquests.

His tunic, simple yet stately, is cinched with a polished belt, a gleaming buckle bearing the proud insignia of the wolf of Rome.

Unlike the ornamental decadence of the Senate or the twin emperors, his attire speaks of purpose and practicality—beauty tempered by utility.

And his face—by Jupiter, his beautiful face.

It is a map of victories and sacrifices, weathered yet noble. The lines carved by years of sun and battle only enhance the sharpness of his features, as if the gods had personally molded him for their own designs.

His hair, dark and streaked with silver like the gleam of moonlight on a blade, curls faintly at his temples.

His beard, neatly trimmed, frames a mouth set in the hard line of a man who has spoken a thousand commands and swallowed a thousand regrets.

But it is his eyes that strike you most: deep, piercing, soulful-brown eyes.

They are the eyes of a man who has seen the best and worst of humanity and bears the weight of both.

Your breath catches as his gaze sweeps over you, taking in the sight of a young servant clutching a parchment like a shield.

He regards you with a sharp, assessing gaze, his eyes like iron tempered in fire—unyielding yet reflective.

His presence is commanding, a gravity that draws everything into its orbit. You are struck by how different he is from the emperors.

Where Geta and Caracalla exude indulgence and cruelty, Acacius carries himself with the disciplined grace of a man who has known the weight of true responsibility.

“Not many choose the gardens for their thoughts,” he says, his voice deep, steady, and tinged with curiosity.

It is a soldier’s voice, devoid of the honeyed pretense of courtiers.

You scramble to your feet, clutching your parchment to your chest. “General,” you manage, your voice trembling despite your best efforts.

He raises a hand, the gesture more commanding than any shout. “At ease,” he says, a faint flicker of something—amusement, perhaps—crossing his face. “You are Livia's daughter?"

His question hangs in the air like the distant clang of a bell. You nodded, your name feels small in your mouth when you finally say it, barely audible against the rustling of the garden’s leaves.

Acacius nods, as though filing the information away. His eyes flick to the parchment in your hands. “A poet?”

You hesitate, “I... I write, sometimes. Thoughts.”

He steps closer, his presence overwhelming yet strangely grounding. He does not reach for the parchment, but his gaze lingers on it as though he could read its contents by sheer will alone.

“Thoughts on Rome, perhaps?” he asks.

His tone is even, but there is an edge to it, a subtle weight that suggests he already knows the answer.

Your throat tightens. To speak of the empire’s flaws to a general of its armies feels like standing on the edge of a blade.

Yet something in his bearing—a quiet patience, a restrained curiosity—compels you to answer honestly.

“Yes,” you admit softly. “About Rome. And its people.”

Acacius’s expression shifts almost imperceptibly, a shadow crossing his face. He looks away, toward the pond, his gaze distant now, as if seeing not the still water but something far beyond it.

“The people,” he repeats, almost to himself. “The heart of Rome. And yet, the heart is always the first to be sacrificed.”

The words are spoken quietly, but they carry the weight of experience, of battles fought not just with swords but with conscience.

You watch him, your earlier fear now replaced by a cautious curiosity.

"Do you... believe that?" you venture, your voice barely above a whisper, the words trembling like a fledgling bird daring its first flight.

Marcus halts, his crimson cloak swaying like the banner of a legion stilled in the wind.

He turns to you, his eyes—sharp as a polished gladius—softening for the briefest moment, as if your question has reached a part of him long buried under layers of duty and steel.

“Belief,” he begins, his voice low and steady, carrying the weight of a man who has lived lifetimes in service to an empire, “is a luxury in the life of a soldier. I deal in action, not faith. But I have seen enough to know that Rome’s strength lies not in its emperors, but in its people. And we are failing them.”

The honesty in his words strikes you like the tolling of a great bronze bell, reverberating through the quiet garden and deep into your chest.

It is not what you expected from a man like him—a hero to some, a sword-arm to the empire—but here he stands, speaking not as a general but as a man, his voice laced with something unguarded. Regret, perhaps. Or hope—fragile and faint, but alive nonetheless.

“Do you believe in Rome, little one?” His question falls like a stone into still waters, and you startle, unprepared to have the conversation turned toward you.

“I—” Your words falter, and you look down at your hands, clutching the parchment that now feels like an accusation.

But then, something inside you stirs—something that refuses to shrink back beneath the weight of his gaze.

You lift your eyes to meet his, the courage in your chest kindled like a flame drawn from embers.

“I believe in what Rome could be,” you reply, your voice steadier now.

“I believe in the Rome that lives in the hearts of its people—the ones who work its fields, who build its roads, who kneel at its altars not out of fear, but out of love. That is the Rome worth fighting for. But the Rome I see now…” Your throat tightens, but you press on.

“...has forgotten its people. It worships marble statues and golden coins while the streets crumble and the people starve. How can an empire endure when its foundation is so neglected?”

Your words spill forth, unchecked and unmeasured, and it is only when you see the faintest flicker of something in his expression—respect, perhaps, or surprise—that you remember who stands before you.

The weight of your boldness sinks in like a gladiator realizing they’ve overstepped in the arena.

“Forgive me, General,” you murmur, lowering your gaze. “I forgot myself.”

But Marcus shakes his head, a wry smile playing at the edges of his mouth. “Do not apologize,” he says, his tone gentler now, though no less commanding.

“You are young, but your words carry the wisdom of one who has not yet been corrupted by power. Few speak with such clarity, and fewer still with such courage.”

His gaze lingers on you, searching, and you feel it like the sun breaking through storm clouds.

“You remind me,” he says, his voice quieter, almost reverent, “of someone. He believed, as you do, in the strength of Rome’s people. He would sit in gardens much like this one, speaking of justice and duty, and wonder aloud whether the empire could ever live up to its ideals.”

Your heart quickens, the weight of his words settling over you like the cloak of a goddess.

The way Marcus looks at you—as though he sees not the servant, but the soul beneath—makes you feel for a fleeting moment.

“I am no philosopher,” you say softly, your fingers tightening on the parchment. “But it is hard to remain silent when I see so much suffering.”

“A Roman citizen has every right to speak of their empire’s failings,” he says, stepping closer now.

“Do not mistake me for a politician, child. I am a soldier. My loyalty is to Rome—not to the men who rule it."

You nod, the words settling over you like a cloak woven of both gravity and reassurance.

The air between you feels charged, alive with the kind of understanding that is rarely spoken but deeply felt.

You watch him, his form cast in the golden hues of the setting sun, the crimson of his cloak vivid against the muted greens of the garden.

There is something about him that draws you—not merely his reputation, not the legends whispered in the palace halls of his valor and victories, but him.

The man behind the titles and statues.

You swallow, your heart a restless bird in your chest. You should not linger, not with him, not now.

And yet, you find yourself unable to walk away.

Words rise to your lips, hesitant at first, but then they spill forth, tentative and careful, like a child offering a wildflower to a god.

“Forgive me, my lord, but shouldn’t you be inside?” you say, your voice trembling under the weight of its boldness. “The palace is bustling with your celebration—wishing you fortune for your campaign, for Rome’s glory.”

He turns his gaze to you, the faintest flicker of amusement playing at the corners of his mouth. “Rome’s glory,” he repeats, as though tasting the phrase on his tongue, finding it bitter.

He lets out a soft chuckle, low and warm, a sound that feels oddly out of place amidst the solemn grandeur of the garden. “Let them feast. Let them toast. I’ve no appetite for gilded words tonight.”

You blink, surprised by his candor. He is not what you imagined—not the marble statue immortalized in the Forum or the hardened general whose name echoes in the chants of soldiers. He is… more human than that.

“I’m waiting for my wife,” he adds, his tone casual, though his eyes seem to linger on you as if measuring your reaction.

Princess Lucilla.

The name hangs in the air, heavy with the weight of legend. Rome’s Princess. The only daughter of Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-emperor. You’ve never met her, though her shadow looms large over your life.

“She was delayed,” he continues, glancing toward the palace, though his stance is relaxed, unhurried.

Princess Lucilla, her legend precedes her, a name spoken with reverence, and sometimes, in hushed tones, with fear.

Your mother, Livia, has served her since she was but a girl.

Livia, who moves through the world with a quiet dignity, has always spoken of the princess with unwavering loyalty. “She carries Rome on her shoulders,” your mother would say, her voice tinged with both pride and sorrow. “The weight of a crown rests on her brow, even though it does not sit there.”

Your thoughts drift, but his voice pulls you back to the present.

“Your mother,” Marcus says, his tone shifting to something softer, more contemplative, “she’s a loyal servant to our household, isn’t she?”

You nod, feeling a strange warmth rise to your cheeks. “She is, my lord. My mother adores the princess. She always speaks highly of her.”

At this, Marcus smiles faintly. His expression, though guarded, carries a warmth that feels rare, as if he’s allowing himself a brief reprieve from his usual stoicism.

“Livia is wise, then. Lucilla is… more than most know. Rome sees her as Marcus Aurelius’ daughter, but to me—” He pauses, his voice lowering to something almost reverent.

“She is a woman of strength, far greater than any man I’ve known. Her loyalty to Rome and its people… it humbles me.”

For a fleeting moment, his mask of a hardened general slips, and you glimpse something deeper.

A man bound not just by duty but by love.

His words hang in the air, gilded with affection, and you feel a pang of longing, though for what, you cannot say.

“I’ve never met her,” you admit, your voice quieter now.

He turns to you, curiosity flickering in his gaze. “Lucilla?”

You nod, feeling suddenly self-conscious beneath his scrutiny. “I’ve only heard stories. My mother always told me about her strength, her grace. But we’ve never crossed paths.”

Marcus regards you for a long moment, as if seeing something in you he had not noticed before. “She would like you,” he says at last, his voice steady, though something lingers in his tone, a note of intrigue.

“Are you coming to the feast tonight?” he asks, the question catching you off guard.

You hesitate, glancing toward the palace where the distant hum of celebration filters through the evening air. “Servants are not permitted to attend such events, my lord,” you say, lowering your gaze. “I am only a servant after all,"

His brows furrow slightly, as if the answer displeases him. “Rome is built on the backs of those it calls servants. Do not diminish yourself.”

You blink, unsure of how to respond. There’s a weight in his words, one that feels both heavy and freeing.

Before he can say more, hurried footsteps echo through the garden. You turn, and there stands Alexandra, one of the palace attendants, her expression tight with worry.

“My lord,” she says, bowing her head quickly as her wide eyes catch sight of Marcus.

The respect is immediate, almost reflexive. General Acacius commands not just authority but admiration.

Men respect him, but women… they speak of him in hushed tones, a figure both distant and impossibly magnetic.

“Forgive me for interrupting,” Alexandra continues, her voice trembling slightly under the weight of his gaze. “Your mother is looking for you,"

Marcus looks at you, his expression softening. He steps aside, the movement graceful despite his formidable frame, as though making room for your escape.

"Tell Livia my apologies for keeping her daughter here," he says, his voice low yet deliberate, as though each word is a promise carved in stone.

His gaze lingers on you, longer than it should, and it feels as though he is reading something beyond the surface—a map of your heart, perhaps, etched in the lines of your face.

For a moment, the world narrows to just this: the garden bathed in the golden light of a setting sun, the faint murmur of the distant feast, and the weight of his eyes, heavy yet strangely gentle.

There is something about you, his expression seems to say—something unspoken but undeniable.

You feel it too, a spark that flickers to life beneath the layers of duty, expectation, and fear.

“I’ll see you at the feast tonight,” he says, the words more a statement than an invitation, leaving little room for protest.

There is a finality to his tone, yet also a quiet insistence that stirs something within you.

Before you can respond, he dips his head ever so slightly—a gesture of respect, or perhaps acknowledgment—before turning and striding away, his crimson cloak flowing like a banner in his wake.

You bow reflexively, watching him disappear into the shadowed corridors of the palace, his figure swallowed by the grandeur of Rome itself.

Yet even as he leaves, his presence lingers, an echo in the air, a weight in your chest.

As soon as the sound of his footsteps fades, Alexandra is at your side, her face alight with barely contained awe.

“Was that… the general?” she whispers, her voice tinged with something between disbelief and reverence.

“Yes,” you reply, though your own voice feels distant, as though it belongs to someone else. Your thoughts are still tethered to the garden, to the quiet intensity of his gaze.

“By the gods,” she breathes, clutching your arm as though you might disappear. “He’s… he’s even more handsome up close.”

You chuckle softly, shaking your head. “Careful, Ale,” you chide gently, though there’s no malice in your words.

“I’ve heard so much about him,” she continues, her voice dropping to a conspiratorial whisper.

“About his loyalty to Maximus Decimus Meridius—the late general—and how he served under him during the great campaigns. They say he adored the princess even then. Some even whisper that his loyalty to Maximus was why he stayed so close to her after his death, marrying her to protect her.”

You glance at her, your brow furrowing slightly. “You know far too much for someone who spends their days in the laundry.”

She grins, unrepentant. “The laundry is where all the palace’s secrets come to dry.”

You shake your head, though her words gnaw at the edges of your mind.

You’ve heard the stories too, in bits and pieces from the older servants: tales of Lucilla’s love affair with Maximus, and Marcus’s steadfast devotion not only to his commander but to the empire itself.

A marriage born of loyalty, they say, not love. And yet, there’s something in the way Marcus spoke of Lucilla earlier that makes you wonder.

As Alexandra chatters on, her words a tide of gossip and speculation, your thoughts drift back to Marcus.

To the way he stood in the garden, his form framed by the soft glow of the setting sun. To the depth in his eyes, like wells carved by the gods themselves—deep enough to drown in, and yet you couldn’t look away.

You feel a strange restlessness in your chest, a stirring you can’t quite name. It isn’t admiration, nor fear, but something more complicated. Something heavier.

Marcus is unlike anyone you’ve ever known—unlike the indulgent senators with their honeyed words, unlike the cruel twin emperors whose laughter carries the sting of a whip.

He is a man of iron and fire, tempered by years of battle, yet beneath that hardened exterior lies something softer. Something… human.

And perhaps that’s what unsettles you most.

You’ve spent your life surrounded by women: your mother, Livia, with her quiet strength and unshakable loyalty; the other servants, who taught you to navigate the palace’s labyrinthine halls.

Men were distant figures, their power felt but never seen up close. Fathers, you’ve only heard about in stories—abstract concepts, not flesh and blood.

But Marcus is no abstraction.

He is real, tangible, a presence that feels larger than life yet undeniably mortal.

To see him, to feel him, is to glimpse a side of the world you’ve never known—a world shaped not by whispered orders or silent sacrifices, but by action, by conviction, by the weight of decisions made on the edge of a blade.

You shake your head, trying to banish the thoughts, but they cling to you like the scent of blooming jasmine in the garden. “It’s nothing,” you tell yourself, though your heart betrays you with its restless rhythm.

“Nothing at all,” you murmur, though even the words feel like a lie.

#marcus acacius#gladiator 2#pedro pascal#marcus acacius x reader#marcus acacius x you#marcus acacius x y/n#marcus acacius x female reader#smut#pedro pascal x reader#pedro pascal x y/n#pedro pascal x you#pedro pascal characters#ancient rome#gladiator#general acacius#general marcus acacius#general acacius x reader#general acacius x you#general acacius x y/n#female reader#pedrohub#pedro pascal smut#dark Marcus Acacius#Dark!Marcus Acacius#marcus acacius age gap#pedro pascal agegap#pedro pascal age gap#general marcus acacius age gap#age gap reader

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, could I mayhaps request your top ten funkiest/coolest/most interesting looking beetles? :]

10 Beetle is asking a lot... but I do love beetles...

Rainbow Weevil (Pachyrrhynchus congestus pavonius), family Curculionidae, SE Asia

photograph by Javier Rupérez

Rainbow Scarab (Phanaeus vindex), male, family Scarabaeidae, Pennsylvania, USA

a species of “true dung beetle”.

photograph by Michael Reed

Imperial Tortoise Beetle (Stolas imperialis), family Chrysomelidae, found in the Amazon and Atlantic Forests of Brazil

photograph by Sergio Monteiro Nature Photography

Purple Flower Beetle (Chlorocala africana oertzeni), EAT A TASTY BANANA!!!, family Scarabaeidae, found in Tanzania

Other subspecies are green.

photograph by Richard Nakamura (@richards_inverts)

Giant Flower Beetles (Genus Mecynorhina), family Scarabaeidae, from various parts of tropical Africa

M. savegei

M. torquata

M. polyphemus

M. obertheri

photograph by Ennis Fei (@ennisanna_fei)

Cloaked Warty Leaf Beetle (Chlamisus sp.), family Chrysomelidae, Curitiba, PR, Brasil

photograph by Sergio Monteiro

Great Diving Beetle (Dytiscus marginalis), male, family Dytiscidae, eastern Europe

photograph by Jan Hamrsky

828 notes

·

View notes

Text

something I do not understand is when we’re rightly complaining about Brian Reed’s Ms. Marvel run, why do we never mention the fucked up Monica Rambeau LMD stuff? Even in that run it stands out in its misogyny and disgust

#ms. marvel#ms. marvel 2005#monica rambeau#spectrum#photon#captain marvel#aaron stack#machine man#they're fighting on twitter again about pre-Kelly Sue DeConnick Carol and post- and they're clowning on the Brian Reed run for imperialism#and racism and misogyny#all fair and balanced#but no one EVER mentions the LMD thing?#EVER?

1 note

·

View note

Note

godddddd i have disliked becky chambers' work since long way to a small angry planet and I agree that that fish scene is SO much of what is wrong with contemporary SFF especially queer SFF. refreshing take, great review, thank you. would love to hear what authors or works you think of as the antidote to that sensibility.

The thing is, I enjoyed The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet when I first read it - it was a fun, light adventure, clearly a debut novel but I was excited to see where Chambers would go from there. And I actually really do think the sequel, A Closed and Common Orbit, was good! It did interesting things with AI personhood and identity.

... and then Chambers just kinda. Did not get better. She settled into a groove and has a set number of ideas that I feel like she hasn't broken out of, creatively. And they I M O kind of rest on an assumption that "human nature" = "how people act in suburban California."

As an antidote to that sensibility, I'd say... books where people have a real interrelationship with the land they inhabit, a sense of being present, and reciprocal obligations to that land; books that recognize that some things can never be taken back once done; books with well-drawn characters, where people have strong opinions deeply informed by their circumstances, that can't always be easily reconciled with others, and won't be brushed aside; books where these character choices matter, they impact each other, they cannot be easily gotten over, because people have obligations to each other and not-acting is a choice too.

And it's only fair that after all day of being a Hater I should rec some books I really did like.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke - A man lives alone in an infinite House, over an equally infinite ocean. Captures the feeling that I think Monk & Robot was aiming for. Breathtaking beauty, wonder at the world, philosophy of truth, all that good stuff, and actually sticks the landing. The main character's love, attention, and care to his fantasy environment shows through in every page. (Fantasy, short novel)

Imperial Radch by Ann Leckie - An AI, the one fragment remaining of a destroyed imperial spaceship, is on a quest for revenge. Leckie gets cultural differences and multiculturalism, and conversely, what the imposition of a homogeneous culture in the name of unity means. (Space sci-fi, novel trilogy)

Machineries of Empire by Yoon Ha Lee - An army captain's insubordination is punished by giving her a near-impossible mission: to take down a rebelling, heretical sect holing up in a space fortress and defying imperial power. She gets a long dead brain-ghost of a notorious criminal downloaded into her head to help. Very, very good at making you feel like every doomed soldier was a person with a past, with a family, with feelings, with hopes and dreams and frustrations and favorites and preferences and reasons to live, right before they brutally die in a space war. Also very much about the imposition of homogeneity of culture as a force of imperialism. (Space sci-fi, novel trilogy)

The Fortunate Fall by Cameron Reed - Maya Andreyevna is a VR journalist in high-tech dystopian future Russia, and she decides to investigate the truth that the government doesn't want her to. She might die trying. It's fine. Also has digital brain-sharing, this time in a gay way. It's bleak. It's sad. It feels real. Not making a choice is a choice. Backing out is a choice. And choices have consequences. Choices reverberate through history. About responsibility. (Cyberpunk, novel)

The Vanished Birds by Simon Jimenez - Nia Imani is a spaceship captain, a woman out of time, a woman running from her past, and accidentally adopts a boy who has a strange power that could change the galaxy. Spaceship crew-as-found-family in the most heartbreaking of ways. Also about choices, how the choices you make and refuse to make shape you and shape the world around you. How the world is always changing around you, how the world does not stay still when you're gone, and when you come back you're the same but the world has moved on around you. About how relationships aren't always forever, and that doesn't mean they weren't important. About responsibility to others. It's a slow, sad book and does not let anyone rest on their laurels, ever. There is no end of history here. Everything is always changing, on large scales and small, and leaving you behind. (Space sci-fi, novel)

Dungeon Meshi / Delicious in Dungeon by Ryoko Kui - A D&D style fantasy dungeon crawl that stops to think deeply about why there are so many dungeons full of monsters and treasure just hanging around. Here because it's an example of an author thinking through her worldbuilding a lot, and it mattering. Also because of the characters' respect for the animals they are are killing and eating, their lives and their place in the ecosystem, and the ways that humans both fuck up ecosystems with extraction and tourism, but also the ways that you can have reciprocal relationships of responsibility and care with the ecosystem you live in, even if it's considered a dangerous one. (Fantasy, manga series)

Stories of Your Life and Others by Ted Chiang and How Long 'Til Black Future Month by N. K. Jemisin and Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel by Julian K. Jarboe - Short story anthologies that were SO good and SO weird and rewired the way I think. If you want the kind of stuff that is like, the opposite of easy-to-digest feel-good pap, these short stories will get into your brain and make you consider stuff and look at the world from new angles. Most of them aren't particularly upbeat, but there's a lot of variety in the moods.

"Homecoming is Just Another Word for the Sublimation of the Self," "Calf Cleaving in the Benthic Black," and "Termination Stories for the Cyberpunk Dystopia Protagonist" by Isabel J. Kim - Short stories, sci-fi mostly, that twist around in my head and make me think. Kim is very good at that. Also about choices and not-making-choices, about going and staying, about taking the easy route or the hard one, about controlling the narrative.

The Murderbot Diaries by Martha Wells - Security robot with guns in its arms hacks itself free from its oppressive company, mostly wants to half-ass its job but gets sucked into drama, intrigue, and caring against its better judgement. This is on here because 1) I love it 2) I feel like it does for me what cozy sff so frequently fails to do - it makes me feel seen and comforted. It's hopeful and compassionate and about personal growth and finding community and finding one's place in the world, without brushing aside all problems or acting like "everybody effortlessly just gets along" is a meaningful proposal. also 3) because it is one of the few times I have yet seen characters from a hippie, pacifistic, eco-friendly, welcoming, utopian society actually act like people. The humans from Preservation are friendly, helpful, and motivated by truth and justice and compassion, because they come from a friendly, just, compassionate society, and they still actually act like real human beings with different personalities and conflicting opinions and poor reactions to stress and anger and frustration and fear and the whole range of human emotions rather than bland niceness. Also 4) I love it (space sci-fi, novella series mostly)

632 notes

·

View notes

Text

Four culturally significant aquatic birds in Imperial Wardin- the skimmer gull, the albatross, the reed duck, and the hespaean.

The skimmer gull is a small seabird, distinguished by bright red beaks and a single, trailing tail plume. These are sacred and beloved animals with a long history of symbiosis with local fishers. They will intentionally attract the attention of fishermen, bringing them to shoals of fish that are too deep below the surface for the birds to reach. They then will snatch fish fleeing or caught in the nets, and will often be directly fed by their human assistants in an act of gratitude. They benefit tremendously from their sacred status and a taboo against killing or harming them, and can become absolute food-stealing menaces in seaside towns and cities.

The albatross is a seasonal visitor to the region, with this population migrating to small rocky islands in the White Sea to breed. The specific species occurring in this region is on the smaller side, and has a pale pink beak and soft orange legs. Albatrosses are common characters in regional animal folktales (usually as foolish, romantic types), and sometimes appear in tales as shapeshifters, usually turning into young women who have tumultuous affairs with lonely sailors.

Skimmer gulls and albatross are the most sacred animals of Pelennaumache, the face of God which looks upon the ocean, the winds, storms, maritime trade, fisheries, and broader concepts of luck and the infliction and deflection of curses. Killing either of these birds is considered to bring about disastrous bad luck (unless in the context of a proper sacrifice, most commonly in rites to bless ships and/or sailors with good winds and against ill fortune). The eggs of skimmer-gulls are free game and considered delicacies, while the preciousness of the albatross' single egg clutch is recognized and their consumption is generally discouraged (this isn't to say it doesn't happen).

Feathers of rightly sacrificed albatross and skimmer gulls are minor holy relics (ESPECIALLY gull tail plumes), and considered to be the ultimate good luck charm. The fortuitous find of a shed feather can also impart good luck and can be very valuable (the birds are sometimes poached for their feathers, though fears of the consequences are enough that this poaching is limited in scope). You will often see wealthier people wearing the feathers in hats and headdress, and any seafaring vessel worth its salt should have at least one aboard.

Both birds are evoked in the apotropaic Skimmer-Woman motif (in practice it generally has albatross characteristics, though is sometimes depicted with the tail plume of the gull).

The hespaean is a very unusual bird with two distinct species native to the region, one found exclusively in the western Black river system and its estuaries, and one found in the eastern Brilla and Kannethod river systems. They have very small pointed teeth in their bills, a trait virtually unknown outside of the flightless, beakless classes of birds (most prominently qilik). Their wings are vestigial and virtually nonexistent (with only two bony spurs remaining). These birds are almost exclusively aquatic and do not normally emerge onto land (they cannot walk upright at all, and must push themselves on their bellies). The legs of the Black river hespean develop blue pigmentation from their diet (the brighter the blue, the better fed and healthier the bird), which are waved above the surface during elaborate courtship displays. Both species are known for their haunting, warbling cries (very much like a loon, but more of a howling noise that develops into a shrill warble).

Hespaean build their nests in dense beds of reeds or small, vegetation-heavy river islands that provide some protection from predators. They raise their young during the height of the dry season (when more nesting surfaces are available and they can feed their young with more concentrated fish populations), which is an image of hope and resiliency during harsh dry times and the promise of the river's eventual bounty.

It is known that hespaean used to be caught as chicks and raised to help people catch fish (with ropes around their necks to prevent them from swallowing their catch). This practice is now very rare in the Imperial Wardi cultural sphere (mostly still practiced by the Wogan people along the Kannethod river, to whom these birds are also venerated animals) and has been largely replaced with the import of domesticated cormorants from the Lowlands to the southeast (which are more easily trained and can Usually be trusted not to attempt to swallow their catch).

These birds require large rivers that flow year round and have healthy, dense fish stocks. The population is in decline and they are now relatively rare, largely due to development and overfishing around rivers (and on a much larger timescale, the region becoming drier and water levels more irregular, and their competition with more versatile freshwater tiviit).

The reed duck is a migratory freshwater duck whose coming heralds the beginning of the wet season. They come to mate along rivers and wetlands during the final stretches of the dry season, timing their eggs to hatch with the rise in water levels and growth of the vegetation and insects they feed on. They have striking red-brown and gray plumage and very little sexual dimorphism (though the male is somewhat brighter in color and the flesh around the bill turns bright red during the breeding season).

Reed ducks are not domesticated, but some populations are semi-tamed and encouraged to return to certain sites to breed (the riverside temple to Anaemache in Ephennos attracts a massive flock of the ducks every wet season, continually blessing it with their presence and coating its grounds in droppings), and these stocks are the primary source of sacrificial ducks and coveted shed feathers.

Hespaean and reed ducks are the most sacred animals of Anaemache, the Face of God which looks upon freshwater (particularly rivers), rains, seasonal flooding, fertile earth/seasonal fertility, and wild plant life.

The hespaean is representative of Anaemache as the River Itself and the river as a provider of fish. This association comes down to their all-seasons presence in the rivers, and their population density being a signal of a healthy, well-flowing river with good fish stocks. Lands adjacent to hespean territory is often the most reliable and bountiful for human subsistence.

The reed duck in particular is the most venerated sacred animal of Anaemache, as representatives of Anaemache as a Face of seasonal fertility. Its coming announces the return of the rains and seasonal flooding that the region's agriculture relies on, and their cycle of fertility closely matches the cycles of the rivers and that of the earth itself (with their new life emerging with rains, flooding, and new vegetation in the wet season). There is no prohibition on hunting reed ducks (though proper rites and respect are expected for a sacred animal), and their meat and eggs is said to support female fertility and a healthy pregnancy.

#Hespaean are what I've been repeatedly misspelling as hespiornis up until now (got kind of lazy with the 'hespaean' name but the -an root#is established and makes sense). They're derived hesperornithes that have survived up to the present day but near exclusively as#smaller freshwater birds (their larger marine counterparts have been mostly displaced by tiviit and uhrwal)#Hespaean species exist outside of this region and have a worldwide (but highly fragmented and isolated) distribution#creatures

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mast

One of the most important elements of a ship are the masts, because this is where the sails are attached that serve to propel the ship.

History

The oldest evidence for the use of one solid masts comes from the Ubaid site H3 in Kuwait, which dates back to the second half of the sixth millennium BC. There, a clay disc was recovered from a sherd that appears to depict a reed boat with two masts.

A painted clay disc with a diameter of 6.5 cm from site H3 with a design reminiscent of a boat with two masts, second half of the sixth millennium BC

In the West, the concept of a vessel with more than one mast to increase speed under sail and improve sailing characteristics developed in the northern waters of the Mediterranean: the earliest foremast was identified on an Etruscan pyxis from Caere (Italy) from the middle of the 7th century BC: A warship with a furled mainsail attacks an enemy ship and sets a foresail. An Etruscan tomb painting from the period between 475 and 450 BC depicts a two-masted merchant ship with a large foresail on a slightly inclined foremast.

Tomb of the Ship, mid-5th century BC

An artemon (Greek for foresail), which is almost as large as the main sail of the galley, is found on a Corinthian krater as early as the late 6th century BC; otherwise, Greek longships are uniformly depicted without this sail until the 4th century BC. In the East, ancient Indian kingdoms such as the Kalinga are thought to have been built in the 2nd century BC. One of the earliest documented evidence of Indian sail construction is the mural of a three-masted ship in the caves of Ajanta, which is dated to 400-500 AD.

This Ajanta mural depicts an ancient Indian ship with high stem and stern and three oblong sails attached to three masts. Steering-oars can also be seen. Location: Cave No. 2, Ajanta Caves, Aurangabad District, Maharashtra state, India, 400-500 AD

The foremast was used quite frequently on Roman galleys, where, tilted at a 45° angle, it was more like a bowsprit, and the scaled-down foresail attached to it was apparently used as a steering aid rather than for propulsion. While most ancient evidence is iconographic in nature, the existence of foremasts can also be inferred archaeologically from slots in the foremast feet, which were too close to the bow for a mainsail.

Fragment of mosaic depicting "navis tesseraria", a messenger and police boat of the African fleet, 2nd century AD

The artemon, together with the mainsail and the topsail, developed into the standard rigging of seagoing vessels in the Imperial period, which was supplemented by a mizzen on the largest cargo ships. The first recorded three-masters were the huge Syracusia, a prestigious object commissioned by King Hiero II of Syracuse and developed by the polymath Archimedes around 240 BC, as well as other Syracusan merchant ships of the time. The imperial grain freighters that travelled on the routes between Alexandria and Rome also included three-masted ships. A mosaic in Ostia (around 200 AD) shows a freighter with a three-masted rig entering the harbour of Rome. Specialised ships could carry many more masts: Theophrastus (Hist. Plant. 5.8.2) reports that the Romans brought in Corsican timber on a huge raft propelled by up to fifty masts and sails.

Throughout antiquity, both the foresail and the mizzen were secondary in terms of sail size, although they were large enough to require full rigging. In late antiquity, the foremast lost most of its tilt and stood almost upright on some ships.

By the beginning of the early Middle Ages, rigging in Mediterranean shipping had changed fundamentally: The spars, which had long since developed on smaller Greco-Roman ships, replaced the square sail, the most important type of sail in antiquity, which had virtually disappeared from the records by the fourteenth century (while remaining predominant in northern Europe). The dromon, the rowed bireme of the Byzantine fleet, almost certainly had two masts, a larger foremast and one amidships. Their length is estimated at 12 metres and 8 metres respectively, somewhat less than that of the Sicilian war galleys of the time.

Multi-masted sailing ships were reintroduced to the Mediterranean in the late Middle Ages. Large ships became more common and the need for additional masts to steer these ships appropriately grew with the increase in tonnage. Unlike in antiquity, the mizzen mast was introduced on medieval two-masted ships earlier than the foremast, a process that can be traced back to the mid-14th century based on visual material from Venice and Barcelona. To equalise the sail plan, the next obvious step was the addition of a mast in front of the main mast, which first appears in a Catalan ink drawing from 1409. With the establishment of the three-masted ship, propelled by square sails and battens and steered by the pivot-and-piston rudder, all the advanced ship technology required for the great transoceanic voyages was in place by the early 15th century.

In the 16th century, the cross-section of the masts was made up of several pieces of wood and held together with ropes and iron rings.

A lower mast with sections from 1773 to 1800

In order to achieve a greater height, the lower mast is extended, so that a total length of up to 60 metres can be achieved, measured from the keel. From lowest to highest, these were called: lower, top, topgallant, and royal masts. Giving the lower sections sufficient thickness necessitated building them up from separate pieces of wood. Such a section was known as a made mast, as opposed to sections formed from single pieces of timber, which were known as pole masts.

This is a section of HMS Victory's main mast

The forces of the sails on the mast construction are transferred to the hull construction by standing and running rigging, forwards and aft (stern) by stays, and laterally by shrouds or guys. In order to enable sailors to climb up into the rigging, which is particularly necessary for the operation of square riggers, rat lines are knotted into the shrouds like rungs of a ladder. The upper end of a ship's mast is called the masthead.

Mounting

The mast either stands in the mast track on the keel and is passed through the deck or it stands directly on deck. In the first case, the opening must be neatly sealed with a mast collar, otherwise water will penetrate into the living quarters. If the mast is on deck, it must be supported from below on the keel so that the loads do not bend the deck. Practically every sailing ship therefore has a more or less visible vertical support through the cabin.

Masts are usually supported by the standing rigging. The shrouds pull the mast downwards with several times its own weight and thus prevent it from tipping over.

Traditionally, when a sailing ship is built, one or more coins are placed under the mast as a lucky charm (according to my theory, the coins were also used as money to pay Charon the ferryman in the underworld if the ship sank); this custom is still practised today. Just as a horseshoe was nailed to the mast to bring good luck.

Mast types

For square-sail carrying ships, masts in their standard names in bow to stern (front to back) order, are:

Sprit topmast: a small mast set on the end of the bowsprit (discontinued after the early 18th century); not usually counted as a mast, however, when identifying a ship as "two-masted" or "three-masted"

Fore-mast: the mast nearest the bow, or the mast forward of the main-mast. As it is the furthest afore, it may be rigged to the bowsprit. Sections: fore-mast lower, fore topmast, fore topgallant mast

Main-mast: the tallest mast, usually located near the center of the ship Sections: main-mast lower, main topmast, main topgallant mast, royal mast (if fitted)

Mizzen-mast: the aft-most mast. Typically shorter than the fore-mast. Sections: mizzen-mast lower, mizzen topmast, mizzen topgallant mast

Some names given to masts in ships carrying other types of rig (where the naming is less standardised) are:

Bonaventure mizzen: the fourth mast on larger 16th-century galleons, typically lateen-rigged and shorter than the main mizzen.

Jigger-mast: typically, where it is the shortest, the aftmost mast on vessels with more than three masts. Sections: jigger-mast lower, jigger topmast, jigger topgallant mast

When a vessel has two masts, as a general rule, the main mast is the one setting the largest sail. Therefore, in a brig, the forward mast is the foremast and the after mast is the mainmast. In a schooner with two masts, even if the masts are of the same height, the after one usually carries a larger sail (because a longer boom can be used), so the after mast is the mainmast. This contrasts with a ketch or a yawl, where the after mast, and its principal sail, is clearly the smaller of the two, so the terminology is (from forward) mainmast and mizzen. (In a yawl, the term "jigger" is occasionally used for the aftermast.)

Some two-masted luggers have a fore-mast and a mizzen-mast – there is no main-mast. This is because these traditional types used to have three masts, but it was found convenient to dispense with the main-mast and carry larger sails on the remaining masts. This gave more working room, particularly on fishing vessels.

Cock, John. A treatise on mast-making , 1840.

Fincham, John. A Treatise on Masting Ships and Mast Making , 1854. Kipping, Robert. Rudimentary treatise on masting, mast-making, and rigging of ships , 1864.

Steel, David The Elements and Practice of Rigging, Seamanship, and Naval Tactics, Including Sail Making, Mast Making, and Gunnery , 1821.

Steel, David. Steel's Elements Of Mast-making, Sail-making and Rigging , 1794.

Layton, Cyril Walter Thomas, Peter Clissold, and A. G. W. Miller. Dictionary of nautical words and terms. Brown, Son & Ferguson, 1973.

Harland, John. Seamanship in the Age of Sail,1992

Marquardt, Karl Heinz, Bemastung und Takelung von Schiffen des 18. Jahrhunderts, 1986

#naval history#mast#parts of a ship#very long post#sorry#ancient seafaring#medieval seafarinh#age of discovery#age of sail#age of steam

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

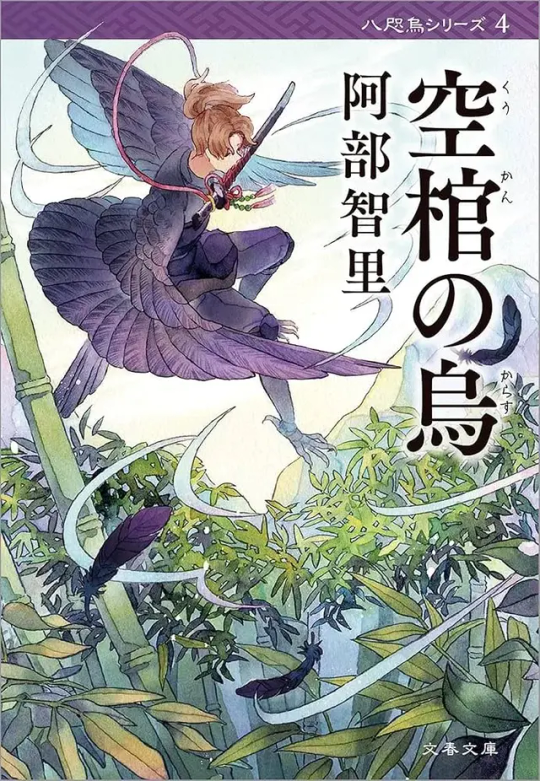

The Raven of the Empty Coffin: Prologue

Disclaimer: This is a fan-translation japanese-english of the original novel. The events of this novel follow after what's already covered by the anime. For an easier understanding, I recommend first reading the few scenes of previous books I've already translated.

Blog version

⊛ ⊛ ⊛

As the outer(1) books say: you shall know of the unbending reed in a gale, learn of the perennial tree in the heavy frost, and observe the great mountain in the storm.

Understand the strength of the grass that will not bend when the gale blows, of the tree that will not yield even when the frost falls, of the mountain that will not collapse when the storm rages.

In a peaceful land, many are those whose loyalty is no more than empty words; and few are the ones who act to prove their fealty in times of upheaval. It is only in troubled times when those truly loyal first become apparent.

Hence, I shall concede this place the name of Unbending Reed Monastery, as it is to become the place of learning for those in possession of genuine loyalty.

“The Golden Raven(2) Bestowing Unbending Reed Monastery Its Name”, from “Chronicles of the Temples of Yamauchi”

Prologue

“Hey, have you heard? It sounds like an unbelievable ‘monster’ is joining us this year.”

The rumors first reached him in the morning, the very same day the new trainees were scheduled to arrive.

“What do you mean by ‘monster’?”

“As in someone strong?”

Faced with the questions of a skeptical breakfast-eating crowd, the rumormonger answered. “That much I can’t say, but he seems to be the son of a very distinguished family. He outranks everyone here at the Monastery for sure.”

Oh, no wonder then, was the immediate general consensus. Nobody around the haphazardly placed four-legged trays, filled with an assortment of food, seemed to question it any further.

“I was thinking that the people from the Center seemed weirdly nervous lately. So that was the reason, huh.”

“Well, if they mess things up, they're going to lose all their privileges to the newcomer.”

“Eh, not like they need to mess anything up for that, you know? There’s no way they’ll be able to push people around anymore, not like they did before at least.” After all, they didn't have any talent whatsoever beyond their social status. Assuming a student with a higher rank did actually arrive, it would force them into paying court to him instead.

“Ridiculous,” Ichiryuu spat out in a low voice, in quite the contrast to his fellow students’ excitement. He had been listening with great interest at first, curious about this ‘unbelievable monster’, but in the end it was all complete rubbish.

“What's wrong, Ichiryuu?” One of his friends, who had somehow heard him complain, turned to him and asked.

Ichiryuu made a show out of snorting.

“As far as we know, the only thing he has going for him is his rank. To call someone like that a ‘monster’? It makes me laugh. We are warriors,” he added, a frown on his face as he looked around the room, “no matter how high your birth, it means nothing if you lack the skill with a sword. We really should leave the ‘monster’ talk for when we see his performance at the dojo.”

The Unbending Reed Monastery, the institution Ichiryuu and the others belonged to, was the training facility for the Yamauchi Guard: the organization in charge of protecting the Imperial Family.

The role of commanding the country and leading the Yatagarasu fell on the Golden Raven, who took residence in Central Mountain and the Imperial Court built inside of it, and protecting the Mountain and its surroundings from any harm was the job of the Feather Grove Heavenly Hosts(3).

Meanwhile, the Yamauchi Guard’s one and only job was to keep the Imperial Family—the Golden Raven's relatives—safe. Furthermore, while the Feather Grove had a Great General at the top, the Yamauchi Guard only took direct orders from the Imperial Family members they personally served.

The Guard was an elite organization; its warriors’ skill was leagues above the rest. As the position did of course come with matching privileges, it was stipulated that all members had to overcome the harsh training of the Unbending Reed Monastery. Your social status did not matter, only talent was required— at least in theory. A long time had passed since the last time that had actually been true.

Ichiryuu's words were born out of frustration towards his fellow trainees’ obsession with bloodlines. The other trainees, however, looked at him as if he had just grown three heads.

“What’s up with him? Did he eat something bad from the ground?”

“No, no, you got it wrong. He wants to be the cool senior, you see, so he's putting on airs already.”

“Just let him be,” people concluded in whispers, just loud enough for Ichiryuu to hear it all.

“You little—” Ichiryuu moved as if to stand up, but he was cut short by the rumormonger, who had just raised both his arms.

“Now, now, calm down, Ichiryuu. I wouldn't call someone a monster either just because they have high status. I have another good reason,” he said with a knowing smile. “Apparently, this newcomer was Wakamiya's close aide before this.”

“Wakamiya's close aide!?”

“Wait, is that true?”

“Now that's amazing!”

The trainees, their eyes wide open, started a ruckus. Wakamiya was the title of the Crown Prince, referring to the man that would one day shoulder all of Yamauchi. To be his close aide was a near guarantee to become one of the next Golven Raven's trusted vassals and hence seize power in the Imperial Court in the future. There was no mistaking it: this ‘monster' had one of the brightest futures possible for all Yatagarasu already promised to him.

“...... But, isn't that weird? He could have just joined the Imperial Court directly, why bother to come to the Monastery of all places?” someone said, skeptical.

Ichiryuu found himself frowning. As the Imperial Court stood at the moment, the On'i System was there to guarantee a rank fitting to their birthright for any noble. If Wakamiya had grown fond of someone with a low enough status then, yes, it would make some sense to send him to the Monastery so he could get a promotion through official means. However, this rumored ‘monster’ was supposed to be from the high nobility.

“Apparently, His Highness said that using the On'i System would be a waste of his talents, or something like that.”

“Really? It’s not like there’s any guarantee he'll even manage to graduate from the Monastery.”

The trainees, who knew better than anyone how brutal training at the Unbending Reed Monastery was, all exchanged glances at once.

“Well, there’s no way for us to know right now. No matter how talented they say he is, that's just by the standards of a Central Noble, am I wrong?”

“But, if the rumors are true and he has both the physical strength and the status, then that's truly a total monster.”

“Whatever, we should be fine as long as he isn't some snotty ass brat.”

While Ichiryuu's fellow trainees were all busy discussing the news animatedly, he stayed silent, too busy ruminating on the information he had just been given. The young son of an important noble family, and Wakamiya's close aide. He could have been given a high rank at the Court with no effort whatsoever, yet he still chose to come to Unbending Reed Monastery. Plus, he was young enough to join in the first place.

With a soft thump, the face of a certain boy came to mind.

——No. It couldn't be him, right?

After a moment, Ichiryuu shook his head. It was impossible. He made a point to take that image, that devious smile hiding under an airheaded facade, off his mind. After all, that guy had said so, hadn't he? That there was no way he was attending the Monastery, that he had no plans to enter the Imperial Court. It was the exact reason Ichiryuu had chosen to become a trainee.

As if to shake off the terrible feeling that had just overcome him, Ichiryuu scarfed down the white rice that remained in his bowl.

After breakfast, his entire group went to the dojo. Spring Break was yet to end, so morning training wasn't mandatory. And so, after a few light drills between those who had come on their own, they all set off to the nearby watering hole to clean off their sweat.

Then, at that precise moment—

“Hey, a newcomer has already arrived!” A fellow trainee, who had gone slightly ahead of the rest, called to them. Ichiryuu's group raised their voices in excitement.

“He sure is fast.”

“Is he truly a newcomer?”

“Most likely yes, and he's coming by flying carriage.”

A mode of transportation only available to the high nobility, it was kept in the air by huge horses. This had to be it. The so-called ‘monster’ that had everyone talking in the morning. Upon this realization, the group started to rush over there. Ichiryuu was in less of a hurry, still incapable of shaking off that bad feeling about the ‘monster'. His steps were heavy as he took his time with each one.

By the time he, the very last one to arrive, finally caught up with the rest, his friends were all crammed behind the azalea bushes, getting a look at their junior.

“I see. He arrived early to move all his furniture.”

“Look at that, he’s bringing so much luggage. I only brought a wrapping cloth worth of stuff with me.”

“And look where he's going too, isn't that the newest dormitory room?”

“The instructors must have gone out of their way to keep him happy.”

As his friends kept on with the half-mocking, half-joking remarks, Ichiryuu was busy thinking. As far as he knew, the person he thought of as the potential ‘monster’ was not the kind to enjoy luxury. Yet, still with fear in his heart, Ichiryuu took a look over the others’ shoulders at the teenager in question.

He first saw his back, his shoulder raised all high and mighty under the cherry blossoms in full bloom. His outfit shined impressively under the sunlight: it was a deep red, covered in white embroidery.

The servants kept on carrying his luggage, but the boy didn't move: he simply stood there imposingly. Instead, he gave them instructions with his folding fan, dyed into a light purple gradient with gold leaf speckles all over. His hair was a glossy reddish brown and neatly brushed.

The boy then turned around to talk with the servants, and Ichiryuu finally caught sight of his face. He was handsome, more than anyone he had ever seen before. His skin was the color of newly blossomed white peonies under dusk, his big eyes shone like reflections on a pond, and his face was soft like that of a woman. The boy was not only beautiful, but also had clear charisma. He was the kind that drew people in naturally, overflowing with pride and confidence.

If one of those poets from the Court had been here, his beauty would have called for a poem or two.

Not like any of that mattered to Ichiryuu, who was too busy experiencing relief. The so-called ‘close aide’ standing there wasn't that guy. Thank goodness, it wasn't him! The second he realized, his mood immediately lifted as if it had never dropped in the first place.

“What a face.”

“Well, nobles only take beauties as concubines, you see.”

“Dammit, wouldn’t it be nice if he fell on his face or something.”

Meanwhile, his friends were still watching the boy and whispering to each other. In stark contrast to them, however, Ichiryuu left the place behind with the lightest of hearts.

Once he had cleaned himself, Ichiryuu went on to his newly assigned dormitory room in the second building, tenth room. It would be his castle for the following year.

The trainees at Unbending Reed Monastery had to overcome three trials, one per year, through their education there. There was a proverb preserved in ancient documents that said as such: ‘you shall know of the unbending reed in a gale, learn of the perennial tree in the heavy frost, and observe the great mountain in the storm.’

It’s when the gales blow that the sturdy grass proves itself. The trees too prove their resilience by surviving the harsh frost, and so it's in times of genuine struggle that the truly strong become clear. The monastery based its trials on it, and thus they were referred to as the Trial of Gale, the Trial of Frost, and the Trial of Storm.

During their first year, trainees were referred to as Seeds(4), as they still had yet to even germinate. It was once they passed the Trial of Gale at the end of the year that they transitioned to Saplings. The Trial of Frost awaited them a year later, and those who managed to pass it would reach their last year and become Evergreens.

Although plenty of seeds sprout, few get to become fully grown trees. In this manner, very few trainees ever became Evergreens. On top of that, those Evergreens also had to overcome the harshest of the tests, the Trial of Storm, and get good enough results to even qualify for the Yamauchi Guard.