#queer historian

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

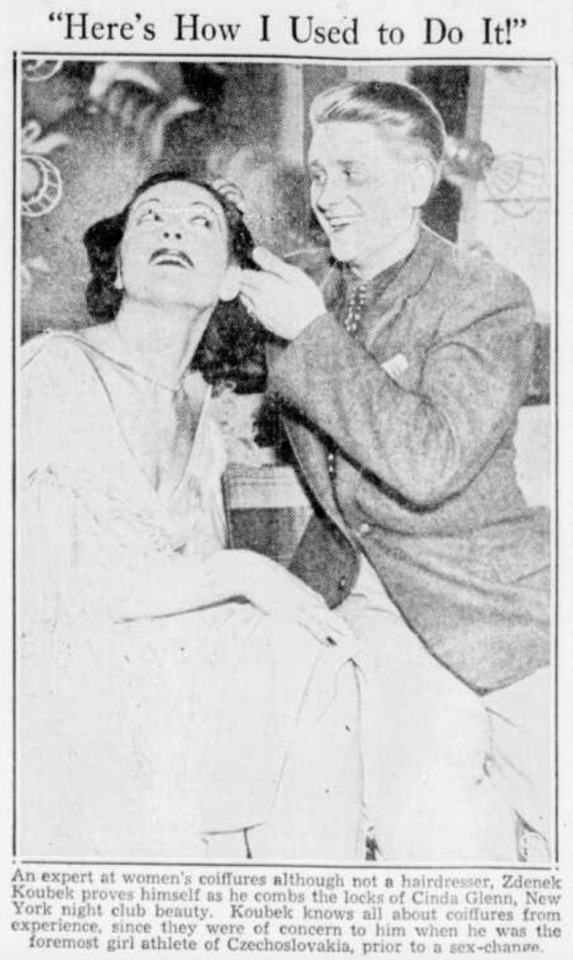

ID: a black and white photo and caption from a newspaper showing a young white trans man with light hair wearing a tweed jacket and high collar smiling at a young white woman in a pale dress as he brushes her mid-length dark hair. She is smiling at him from the slightly complex angle as he brushes her hair. The photo is faded and not great quality but their faces are clear.

The headline over the photo is “Here’s How I Used To Do It!”

The caption below reads “An expert at women's coiffures although not a hairdresser, Zdenek Koubek proves himself as he combs the locks of Cinda Glenn, New York night club beauty. Koubek knows all about coiffures from experience, since they were of concern to him when he was the foremost girl athlete of Czechoslovakia, prior to a sex-change.”

Zdenek Koubek was born in Paskov, Czechoslovakia (at the time) in December 1913, one of eight siblings, and competed as an athlete. With minimal formal training, he began running at age 17, decided to pursue it formally aged 19, and broke two world records at the 1934 world olympics.

Because queer and gender-diverse history is complex, I’m genuinely unsure if Zdenek was intersex. He seems to have been pretty gender-nonconforming when read as a woman in his early life and seems to have retired from athletics because he was harassed by people wanting him to undergo invasive “gender checks” after his gold medals at the 1934 Olympics.

Apparently the current obsession with “defining gender in sport” has roots back to the 1930s. Athletes competing in female athletics have been forced to undergo a variety of examinations for the purpose of declaring them “female enough”. They seem to have never been pleasant, appropriate, or anything other than invasive and dehumanising, and they seem to have always focused on a) defining gender by physicality b) defined that physicality in fairly arbitrary ways that are actually incredibly difficult to relate to anything objective, despite a veneer of scientific objectivity.

I can entirely see why the threat of such harassment would have caused Zdenek to decide an athletic or adjacent career wasn’t worth undergoing it, whether he personally believed himself to be intersex or whether we would recognise him as such today. The term “intersex” has many definitions, and is often challenged by medical professionals if it could potentially cover too many people - e.g. medical professionals have repeatedly challenged the term when used by AFAB people with PCOS, which can cause fertility issues, hirstutism etc, purely on the grounds of “that would make around 10% of women intersex”. Zdenek simply publicly stated “I was wrongly assigned as female at birth” without giving any other details - as he had *every* right to. Some historians have characterised him as intersex based on this, and others simply as trans; he appears, very reasonably, to have preferred to preserve his privacy on the details.

Zdenek went on a lecture tour of the US talking about his life and transitioned in 1936. At the time of this photo, he was pursuing a career in cabaret in the US. He seems to have been reasonably successful but never settled there, returning home and marrying a cis woman with whom he lived happily for the rest of his life, dying in Prague aged 72 in 1986.

He joined a local rugby team along with his brother Jaroslov after WWII and seems to have been an enthusiastic amateur player. I hope he got a lot of joy out of it, which he does seem to have.

Like so many queer and trans histories, Zdenek’s is somewhat obscured because so much of what has been written about him is always skewed by the writer’s own perspectives about gender and transness. Including the drive to impose a false binary on trans experience - which I as a nonbinary person know is certainly not universally present.

There are, of course, *absolutely* trans people who always have a strong feeling of gender equating to “knowing they are a boy/girl from an early age”, and I in no way wish to erase them or their experiences, but it must also be noted and acknowledged there are plenty of us with different experiences. There are people like me who feel “wrong” in our assigned gender from pretty early in life, all the way down to having quite strong dysphoria in puberty and afterwards, but don’t strongly ID as the “opposite” binary gender either. There are people who rub along fine in their assigned gender, or who have many issues with it but don’t know what they equate to, until they have some experience presenting otherwise and suddenly experience strong gender euphoria for the first time in their lives. There are people who never feel anything much at all about gender and only ever do any identifying purely as a matter of convenience because a very binary society requires it.

Cis people seem to find the “always knew/born in the wrong body” narrative the easiest to relate to, and I can only assume that is because it is the narrative that allows them to challenge our society’s gender-essentialist, binarist worldview the *least*. It is considerably easier, and requires much less thought and critical attention, to say “I guess sometimes the occasional person is just mistakenly assigned to the wrong category” than to question those categories, why they exist, what they actually are, how they are imposed, and whether they actually mean anything at all in an objective sense.

I have no idea where Zdenek fell on any of this, or if his experience was very different in another way.

I posted this to, as ever, note that we are not a new phenomenon. Trans people are part of human history. We have always existed. We have always contributed. The way the society we lived in perceived us *and* how the societies our stories have passed through perceived us affect how our stories are told today, and those things can make it complex to uncover the lived experience of the trans person behind all of that. Queer and trans history must always be about acknowledging those facts and uncertainties while doing our best to find out as much as possible about the actual lived experiences of our siblings in the past.

#trans#trans history#queer history#czech history#sports history#historiography#nonbinary#trans historian#nonbinary historian#queer historian#trans man#historical trans man#historical trans person#20th century history#modern history

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y llyfr heddiw yw 'A Practical Guide to Searching LGBTQIA Historical Records' gan Norena Shopland, a gyhoeddwyd yn 2021.

Mae'r llyfr hwn yn wych iawn ar gyfer ymchwilio i hanes LHDTC+. Mae'r hwn yn llawlyfr defnyddiol i unrhyw ymchwilydd a fy hoff lyfr wrth ymchwilio hanes LHDTC+. Mae pob adran yn dangos enghreifftiau mewn archifau papurau newydd, llyfrgelloedd, amgueddfeydd ac yn y blaen. Os ydych chi'n ansicr sut i chwilio am ddogfennau hanesyddol LHDTC+, mae'r llyfr hwn yn dangos sut i ddefnyddio gorchmynion Boolean i chwilio archifau ar-lein ac yn dangos sut i ddefnyddio fethodau eraill i ffeindio unrhyw ddogfennau hanesyddol LHDTC+. Un o fy hoff lyfrau ymchwil!

Ydych chi wedi darllen y llyfr hwn?

/

Today's book is 'A Practical Guide to Searching LGBTQIA Historical Records' by Norena Shopland, published in 2021.

This book is very great for researching LGBTQ+ history. This is a useful handbook for any researcher and a favourite book of mine when researching LGBTQ+ history. Each section showcases examples found in newspaper archives, libraries, museums and so on. If you are unsure how to search for LGBTQ+ historical documents, this book shows how to use Boolean commands to search online archives and shows you how to use other methods to find any LGBTQ+ historical documents. One of my favourite research books!

Have you read this book?

#cymraeg#welsh#lhdt#cymblr#Norena Shopland#A Practical Guide to Searching LGBTQIA+ Historical Records#lgbt history#lgbt historian#queer history#queer historian#Llyfrau Mawrth

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recap of the Irish War of Independence

One cannot talk about or understand the Irish Civil War without understanding the Irish War of Independence. In fact, I’ve seen more and more historians argue that we can think of the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War as one big civil war, since the Royal Irish Constabulary, the IRA’s main enemy before the Black and Tans arrived, were Irish themselves and IRA intimidated, harassed, and executed Irish people who they considered “informers and traitors.” Additionally, many of the hopes, dreams, and aspirations initiated by the women’s liberation moment of 1912, the Lockout of 1913, and Easter Rising were further refined by the Irish War of Independence, and contributed to the violent schism in Irish Society following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. These aspirations and goals would further be redefined by the Irish Civil War with participants of all sides feeling like they lost more than they gained from the entire affair.

Thus, why I feel it’s important to recap the major events of the Irish War of Independence

Leading Up to the Irish War of Independence

Ireland has always been a place of debate, uprisings, and desire for change, but in the early 1900s there were three movements that paved the way for the Irish War of Independence: the Suffragette Movement of 1912, the Gaelic Revival, the 1913 Lockout, the Home Rule Campaign and Easter Rising. I’ve discussed all four movements in great detail in the first season, but in summary, the Suffragette Movement, the Gaelic Revival, and the 1913 Lockout created an environment of mass organizing and brought together many activists and future revolutionaries. The Home Rule Campaign, combined with WWI, created the conditions for a violent uprising.

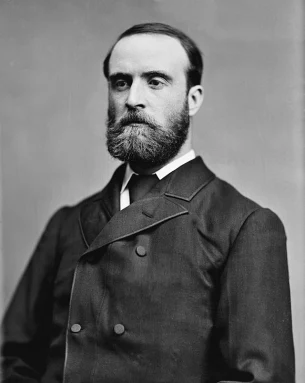

Charles Parnell

[Image description: A black and white photo of a white man with a high forehead and a thick, round beard. He is wearing a white button down and black tie and a grey double breast jacket.]

British Prime Minister Gladstone introduced the concept of Home Rule in 1880, with support from one of Ireland’s most famous statesmen: Charles Parnell. The entire purpose of Home Rule was to grant Ireland its own Parliament with seats available to both the Catholic majority and the Protestant minority and current power brokers). However, Parnell destroyed support for Home Rule by being involved in a messy and scandalous divorce and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), the precursor to the Irish Republican Army (IRA), scared the British government with their terrorist attacks. Home Role went through another failed iteration, but John Redmond was confident he would get the third iteration passed. This newest iteration was introduced to Parliament in 1914 and have created a bicameral Irish Parliament in Dublin, abolished Dublin Castle (the center of British power in Ireland), and continued to allow a portion of Irish MPs to sit in Parliament. It was supported by many nationalists in Ireland, barely tolerated by the Asquith Administration, and despised by the Unionists.

The Unionists believed they had a reason to worry. They had not forgotten the Protestants slaughtered during the 1798 Uprising nor the power they lost through the machinations of O’Connell and Parnell. Facing a massive change in their lives should Home Rule pass, the Unionists took a page out of the physical force book and created their own paramilitary organization: the Ulster Volunteers. The Asquith government knew of the Ulster Volunteers, their gun smuggling, and their drilling, but did nothing except delay Home Rule as long as possible.

Asquith’s delaying tactics and the creation of the Ulster Volunteers made Irish Nationalists nervous and they took matters into their own hand. Arthur Griffith, an Irish writer, politician, and the source of inspiration for many young rebels created the political party, Sinn Fein. Griffith argued for a dual monarchy approach, similar to the Austrian-Hungary model. He believed Ireland and England should be separate nations, united under a single monarchy. He also introduced the concept of parliamentary absenteeism i.e., Sinn Fein was a political party that would never sit in British Parliament, because the parliament was illegitimate.

Eoin MacNeill

[Image description: A black and white picture of a tall man in a courtyard. He has a high forehead, wire frame glasses, and a shortly trimmed beard. He is standing with his hands behind his back holding a hat. He is wearing a white button down, a tie, a vest, and a suit jacket and grey pants.]

In response to the Ulster Volunteers, Eoin McNeill and Bulmer Hobson created the Irish Volunteers. Both men believed that the Irish wouldn’t stand a chance in an uprising against the British government and their best bet was to trust Redmond to pass Home Rule. The Irish Volunteers were created in order to defend their community from Unionist attacks. Things were tense in Ireland, but it seemed that parliamentary politics could save the day and the extremists would be pushed to the sidelines.

Then World War I began.

The British used the war to pass Home Rule but delay it taking affect for another three years. To add insult to injury, John Redmond encouraged young Irishmen to enlist in the British Army and fight for the Empire. McNeill and Hobson tried to convince its members to continue to trust Redmond, although they were angry that he was recruiting for the war. Yet, there was a handful of Irish Volunteers, who were also members of the resurrected IRB believed England’s difficulty, Irish opportunity.

They were Tom Clarke, Sean MacDiarmada, Padraig Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, Eamonn Ceannt, and Joseph Plunkett. These men, plus James Connolly of the Irish Citizen Army, would sign the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and it would serve as their death warrant.

They knew they would not be able to win without arms and support, so, keeping their plans to themselves, they sent Roger Casement to Germany to present their plans for a German invasion that would coincide with an Irish rising. The Germans rejected this plan (maybe remembering what happened in 1798, when the French made a similar landing, weeks after a massive Irish uprising), but promised to send arms.

The Irish Volunteers were often seen drilling and practicing for some vague rebellion, so it wasn’t suspicious to the authorities or to MacNeil and Hobson to see units marching around. When Pearse issued orders for parade practice on April 23rd, Easter Sunday, MacNeil and Hobson took it at face value while those in the know, knew what it really meant. This surreal arrangement would not last for long and the committee’s secrecy nearly destroyed the very rising it was trying to inspire.

The first bit of trouble was Roger Casement’s arrest. The Germans were less than supportive of the uprising, and Casement boarded the ship Aud to return to Ireland to either stop or postpone the rising. However, when he arrived in Ireland on either April 21st or 22nd, he was pick up by British police and placed in jail.

Pearse Surrenders

[Image description: A faded black and white photo of three men standing on a street in Dublin. There are two man on the left and they are wearing the khaki cap and uniform of the British army. On the right is a man wearing a wide brim hat and a long black jacket]

Then MacNeil and Hobson had their worst suspicions confirmed-Pearse and his comrades were secretly planning a rebellion without their support. MacNeill vowed to do everything (except going to the authorities) to prevent the Rising and sent out a counter-order, canceling the drills scheduled for Sunday. This counter-order took an already confused situation and turned it into a bewildering disaster. Units formed as ordered by Pearse and dispersed with great puzzlement and some anger and frustration. Pearse and his comrades met to discuss their next steps and decided the die had been cast. There was no other choice except to try again tomorrow, Monday, 24th, April 1916.

Easter Rising was concentrated in Dublin with a few units causing trouble on the city’s outskirts. The Irish rebels fought from Monday to Friday, surrendering Friday morning. The leaders of the rising were murdered, but many future IRA leaders such as Eamon DeValera, Michael Collins, Richard Mulcahy, Constance Markievicz, Liam Lynch, and others survived. They were sent to several different prisons, the most famous being Frongoch where Collins was held. The IRB turned it into a revolutionary academy and practiced their organizing and resistance skills while formalizing connections and relationships. When they were released starting in December 1916, they were ready to take those skills back to Ireland.

Creation of the IRA and the Dail

Their approach was two pronged: winning elections and rebuilding the Irish Volunteers/ Irish Republican Brotherhood.

When the prisoners were released, the Irish population went from hating them for launching a useless rebellion to cheering their return. The English helped flame the revolutionary spirit in Ireland by proclaiming Easter Rising a “Sinn Fein” rebellion and arresting many Sinn Fein members who had nothing to do with the Rising. This made it clear Sinn Fein was the revolutionary party while John Redmond’s party was out of touch.

Eamon de Valera

[Image description: A black and white photo of a white man with a sharp nose and large, circular glasses. He has black hair and is wearing a white button down shirt, a polka dotted tie, and a grey suit.]

Sinn Fein ran several candidates such as Eamon DeValera, Michael Collins, and Thomas Ashe. Ashe would be arrested while campaigning and charged with sedition. While in jail, he went on hunger strike and was killed during a force feeding. Following an Irish tradition, Sinn Fein and the IRB turned Ashe’s funeral into a political lightning rod. They organized the funeral procession, the three-volley salute, and Collins spoke over Ashe’s grave: “There will be no oration. Nothing remains to be said, for the volley which has been fired is the only speech it is proper to make above the grave of a dead Fenian.”

On October 26th, 1917, Sinn Fein would hold their first national convention. During the convention, Eamon DeValera replaced Arthur Griffith as president and Sinn Fein dedicated itself to Irish independence with the promise that after independence was achieved the Irish people could elect its own form of government. However, there was still tension between those who believed in passive non-violence and the militant Sixteeners. 1917-1918 was spent building a bridge between parliamentary politics and militant politics of the 1920s, with Sinn Fein’s large young membership pushing it in a more militant direction.

Constance Markievicz

[Image description: A sepia tone photo of a white woman looking to her right. She is leaning against a stool and holds a revolver. She wears a wide brim hat with black feathers and flowers. She has short hair. She is wear a military button down short and suspenders.]

Sinn Fein was also breaking social conventions, even though Cumann na mBan was still an auxiliary unit, Sinn Fein would allow four ladies on the Sinn Fein Executive and would run two women in the 1918 election-Constance Markievicz and Winifred Carney, with Markievicz becoming the first women to win a seat in parliament. Many of its supporters and campaigners were also women. In fact, many men would complain in 1917 and later that the women were more radical than the men. Cumann na mBan fully embraced the 1916 Proclamation and even had Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington deliver a message to President Wilson in 1918, asking him to recognize the Irish Republic. Cumann na mBan took the front line in the anti-recruitment campaign and the police boycott and the anti-conscription movement. Like the Volunteers, Cumann na mBan believed they were a military unit, although they never got arms for themselves and worked closely with Volunteer units and Sinn Fein clubs.

Irish Volunteers and IRB

While Sinn Fein was slowly rebuilding itself, the Irish Volunteers were also being resurrected from the ashes. It started with local initiatives led by men like Ernest Blythe, Eoin O’Duffy, and Sean Treacy. Units popped up in local communities, organized and armed by their local leaders and eventually contacting GHQ which consisted of men like Collins, Mulcahy, and Brugha. While local units were rebuilding themselves, Collins was using the IRB to form a strict corps of officers, a growing source of personal power as well as military power that men like Brugha and De Valera (who were IRB during Easter Rising, but renounced their membership after the rising failed) distrusted.

GHQ issued an order saying that units should only listen to orders coming from their own executive (in order to prevent the order-counter-order disaster that doomed Easter Rising) and swore the Volunteers would only be ordered into the field if commanders were confident of victory. No forlorn battles. Mulcahy, as Chief of Staff, worked hard to instill a military spirit and discipline into the Volunteers while understanding that their most effective unit at the moment was the company and local initiative. (The companies would expand into battalions and brigades as the war progressed, but the fighting and tactics would remain local and territorial) So, while trying to act like a regular army and expecting the Volunteers to respect their officers and GHQ, he also had to allow for local improvisation as well as trust the local executives to have control over their soldiers. It was a difficult balancing act he would struggle to maintain during the entire Anglo-Irish War and into the Irish Civil War and the formation of the Free Irish State.

The Irish Volunteers convention on October 26th, 1917, elected DeValera as president, Brugha as the chairman of the executive with Collins as director of organization and Mulcahy as director of training, Liam Lynch as Director of Communications, Staines, Director of Supply and Treasurer, O’Connor director of engineering.

All of this work could have been for nothing if the British hadn’t handed the IRA the greatest gift in the world: the 1918 conscription crisis.

Lightning Rod Issues

Food Shortage 1917-1918

Before conscription was the food shortages in the winter of 1917-1918. The shortage was created because of food being exported to Britain, invoking memories of the terrible famine. Sinn Fein could not stop all of the food being exported, but they did what they could to protest this newest version of starvation. For example, a member of Sinn Fein, Diarmund Lynch took thirty pigs meant to for exportation, killed them, and shared the food with hard hit families, earning him deportation to America, but becoming a local folk hero and increasing Sinn Fein’s prestige.

There were also agrarian tensions because grazers (those who used farmland for their cows to graze instead of growing crops) were given preference to available land so the Congested Districts Board could maximize profits. While this makes sense, it added to the great unease in the land, especially as the food shortage grew more acute.

The IPP grew out of the Land Wars of 1880s and Sinn Fein, ever aware of Irish history, decided it would be no different. It joined in the fight for land, arguing that all the ranch land should be broken up evenly. All over the country, Sinn Fein created commission to break up the land and figure out the pricing as well as organizing mass occupation of available land, but ranchers refused to acknowledge the prices Sinn Fein proposed.

1917 Electoral Victory March

[Image description: A black and white photo of several men and women marching together through a park with several tall green trees and a cobblestone wall. Leading the crowd are three men in long coats and wide brim hats playing bagpipes. Everyone else is wearing long coats, suit coats, or dresses and hats.]

The Irish Volunteers officially stayed out of the new land war, claiming it wasn’t military or political in nature, but local groups sometimes participated. This combined with Sinn Fein’s own land seizures could lead to painful confrontations with police and other anger Irish men, so it was a difficult job balancing non-violent and not starting a mass uprising.

Another tool Sinn Fein used was boycotting. Said to original in Ireland during the Land Wars and used to great affect by Charles Parnell, Sinn Fein boycotted the RIC. This was a serious threat to the British system, decreasing the pool of candidates it could recruit from for the RIC and training the people to view the RIC as “others,” the first step to making a population comfort with violent action.

Boycotting the RIC was an old idea, something Sinn Fein and the Irish Volunteers wanted to implement it as soon as they were released from prison. This became a strong tool of the Volunteers to ostracize those who were betraying the rebel cause by working for the British as well as prepare the citizens for a war mentality.

Conscription crisis

No one yet knew that World War I would be over by November 11th, 1918. British thought she was facing long years of further bitter sacrifices and they needed new blood. They looked at Ireland and its large set of unruly young men itching for a fight and introduced the Military Service bill, extending forced conscription to Ireland-giving the Volunteers a shot in the arm while also uniting the Irish political parties, for the first time ever.

The Sinn Fein, IPP, and the Catholic Church pledged to resist Britain’s efforts to conscript Irishmen. DeValera prepared a statement, meant for Woodrow Wilson, insisting that their resistance was a battle for self-determination and principles of civil liberty, similar to the American’s cause during America’s revolution. The Volunteers planned local actions as well, using the conscription crisis as a springboard for intensive recruiting and introducing the idea of militant resistance into the greater Irish consciousness. The boycott of the RIC increased tenfold during the anti-conscription movement, shocking the police and trapping them in their barracks in locations such as North Tipperary. Women were particularly effective implementers of the boycott. Eventually the boycott was expanded to include those who helped or associated with the police. The boycott didn’t force many police to resign, but it built a belligerent and hateful mindset against the police-allowing for later violence.

Anti-conscription Rally in Ballaghaderreen County

[Image description: A blur black and white photo of a large gathering of people. They are surrounding a wooden platform where as group of men stand. Above the platform there is a white banner that says: No conscription Stand United]

The Irish Volunteers were not as engaged with the conscription crisis as Sinn Fein, because they still didn’t have a doctrinal strategy in place. Instead, volunteers were told to avoid getting arrested and if the RIC tried to arrest them, to resist. The Volunteers held daily drills and parades and prepared for battle, should the order ever arrive. However, GHQ seemed more concerned with getting rifles and ammunition than ordering a massive uprising. Conscription allowed them to demand that the local area their units controlled give up their guns to the Irish Volunteers. Some Volunteers even bought rifles off RIC or local British soldiers. Lack of guns would be a problem that plagued the IRA through their war with the British. Conscription also saw a spike in people joining the Irish Volunteers. GHQ tried to manage this wave of volunteers by issuing orders regarding how men should be recruits and how they should be vouched for and accepted.

The Irish Volunteers allowed their own soldiers to elect their officers (how could this go wrong?) GHQ seemed to try and curb who could be elected like requiring that they be member of the IRB, but given the haphazard nature these units were created, but it was only somewhat successful, some units merging the Volunteers and IRB men seamlessly, while other companies were dominated by non-IRB men or vice versa.

They threatened mass slaughter should Britain try to enforce conscription and, apparently, there was a plan for Cathal Brugha to lead a group of men to assassin the British cabinet (relying on Collins and Mulcahy-who was now chief of staff-to recruit for this venture).

German Plot

The British back down on conscription in mid-May while also arresting 73 nationalist leaders from May 17-18 under the Defense of the Realm Act, including Eamon DeValera, Constance Markievicz, Arthur Griffith, and William Cosgrave. They claimed there was a German plot i.e., Sinn Fein was working with Germany-like the 1916 rebels did and the 1798 rebels with the French.

It quickly became clear how flimsy the excuse was, that there was scant information, and undermined the government’s credibility in Ireland. It successfully knocked Sinn Fein off its feet for a moment, especially since all nine of the twenty-one members of Sinn Fein’s Standing Committee were arrested, but the British failed to arrest some of the most dangerous rebels such as Collins, Brugha, Mulcahy, and Harry Boland. But in the long run, it boosted Sinn Fein’s cause and destroyed any chance IPP had of reclaiming the national narrative. As Constance Markievicz claimed, "sending you to jail is like pulling out all the loud stops on all the speeches you ever made…our arrests carry so much further than speeches.”

1918 Election

Sinn Fein had won a total of five elections between 1917 and 1918 (De Valera, Count Plunkett, Cosgrave, Patrick MacCartan, and Griffith) and lost two elections. 1918 was their first general election. The election was held on December 14th, 1918, and is considered one of the most important moments in modern Ireland’s history. It was the first election after the end of the First World War and, because of the Representation of the People Act, women over the age of 30 and working-class men over the age of 21 could vote, tripling the Irish electorate from 700,000 in 1910 to 1.93 million in 1918.

The IPP won only 6 seats, the Unionists took 26 seats, and Sinn Fein won 73 seats.

The Sinn Fein victory can be explained in three different ways:

The new electoral: women and working-class men: people who had been hardest hit by the war and the rising and the conscription crisis, as well as the good shortage in 1917.Not only was Sinn Fein and Irish Volunteers campaigning, but Cumann na mBan campaigned hard as well, possible driving people into the arms of Sinn Fein since Sinn Fein stood for a republic which was against everything as it currently was. iSinn Fein’s rivals: the IPP and Labour had been broken by WWI and needed to rebuild themselves and their reputations if they wanted to compete.

The clergy was on Sinn Fein’s side because of conscription. DeValera also went a long way to argue that anti-conscription was not anti-soldiers nor were they ignoring the sacrifice of the Irishmen who had fought in the war so far. But the crime was that Britain sacrificed the best Ireland had for a colonial war.

Curated candidates. Sinn Fein ran those it was confident would win and in seats that would not weaken its own position or risk schism with the Labor movement. Also, there was some election rigging and voter intimidation.

Instead of sitting in parliament, the Sinn Fein candidates would sit in a new parliament: the first Dail of Eireann.

The Dail

The First Dail was formed on January 21st, 1919. It held its first meeting in the Round Room of the Mansion house of Dublin and created a Declaration of Independence and the Dail Constitution. Only 27 minsters appeared because 34 were in jail or on secret missions. Sinn Fein invited the IPP and Unionists to participate but they refused. The declaration of independence ratified the Proclamation of the Republic of Easter Rising and outlined a socialist platform, but it was more of a propaganda message because there was only so much the Dail could realistically achieve while battling England.

Members of the First Dail

[Image description: A black and white photo of three rows of men. The first row of men are sitting down on chairs, the second and third rows of men are standing. Most men are wearing black suits with white button down shirts and ties. Others are wearing tan or grey jackets. Some men had beards and mustaches, but most are clean shaven. Behind the men is a metal staircase and a white building.]

The constitution was a provisional document and created a ministry of the Dail Eireann. The ministry consisted of a President and five secretaries. First ministers of the Dail were:

Chairperson of the Dail: Cathal Brugha (because DeValera was in jail and Collins and Harry Boland were planning how to break him out)

Minister for Finance: Eoin MacNeill

Minister for Home Affairs: Michael Collins

Minister for Foreign Affairs: Count Plunkett

Minister for National Defense: Richard Mulcahy

The Dail expanded the number of ministers in April. It now included nine ministers within the cabinet and four outside the cabinet as well as a mechanism to create substitute presidents and ministers in the realistic event someone was arrested or killed.

This second ministry members were:

President: DeValera

Secretary for Home Affairs: Arthur Griffith

Secretary for Defense: Cathal Brugha

Secretary for Foreign Affairs: Count Plunkett

Secretary for Labour: Constance Markievicz

Secretary for Industries: Eoin MacNeill

Secretary for Finance: Michael Collins

Secretary for Local Government: W. T. CosgraveAustin Stacks would become minster after his release from jail and then took over as secretary for home affairs after Griffith became deputy president.

Once the Dail was convened, the Irish Volunteers saw themselves as an army of an Irish Republic hence why they named themselves the Irish Republican Army. They were formally renamed the IRA on August 20th, 1919, and took an oath of allegiance to the republic and to serve as a standing army.

On June 18th, 1919, the Dail officially established the Dail courts which were meant to replace the British judiciary. They eventually created several series of courts including a parish-based arbitration courts, district courts, and a supreme court which the people trusted more than the British courts. On June 19th, the Dail approved the First Dail Loan to raise funds they couldn’t raise via taxes. Collins would also create a bond scheme which helped keep the Dail and the IRA financially afloat.

England declared the Dail illegal in September 1919, but it was too little too late to undermine Ireland’s shadow government. DeValera left Ireland to fundraise in the United States, leaving Griffith as his Deputy President. The conduct of the Dail fell to its ministers while the conduct of the war fell to Collins, Mulcahy, Brugha, and the field commanders.

BRIEF Summary of Guerrilla Warfare in Ireland

The IRA would be broken into General Headquarters (GHQ) and local commanders. GHQ was run by Chief of Staff Richard Mulcahy who answered to Cathal Brugha, the Minister of Defense. Mulcahy also worked closely with Michael Collins, Minister of Finance and Intelligence and this amorphous command structure created a lot of tension amongst the three men. While Mulcahy tried to install discipline and standardization from GHQ, he was only partially successful as conditions on the ground often trumped whatever master plan GHQ had cooked up.

Richard Mulcahy

[Image description: A sepia toned photo of a thin white man with a prominent nose. He is wearing the military cap and uniform of the Irish National Army.]

It's estimated that the IRA had 15,000 members but only 3,000 were active at one time. The members were broken into three groups: unreliable, reliable, and active. Unreliable meant they were members in name only, reliable meant they played a supporting role, and active meant they were full-time fighters. It’s believed at least 1/5 of the active members were assistants and clerks. Skilled workers dominated the recruitment while farmers and agricultural workers were a minority. About 88% percent of the IRA members were under thirty and a majority of them were Catholics. The most active units were in Dublin County and Munster County which includes the cities of Clare, Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Tipperary, and Waterford.

The local units were supposed to be organized along the lines of a battalion but it was up to the local commanders, who were originally elected by their men. Initially, GHQ tried to assign two to three brigades to a county, but it would take a while before those brigades solidified. For the first year, the IRA could only muster small units, which actually worked in their favor.

Local commanders adopted the “flying columns” method of attack and GHQ eventually gave it their blessing. Flying columns consisted of a permanent roster of soldiers who worked together in small groups in coordinated attacks. The flying columns performed two kinds of attacks: auxiliary and independent

In an auxiliary attack, the flying column was assigned to a battalion as extra support for a large local operation already taking place. In an independent attack, the flying column itself would strike the enemy and retreat. This type of attack included harassing small military camps and police stations, pillaging enemy stories, interrupting communications, and eventually ambushes. The flying columns would become an elite and coveted unit but its soldiers were always on the run and relied on local support to survive.

Michael Collins

[Image description: A black and white photo of a white man shouting to a large crowd. He is standing outside on a platform, in the middle of a city street. He has short hair and is clean shaven. He is wearing a white shirt and a black suit.]

The IRA would go through two different reorganizations. The first occurred in March 1921. It broke up the brigade structure into small columns, built from experienced men. The brigade staff existed to provide supplier of arms, ammunition, and equipment while battalions provided the men for the columns. During the same reorganization, GHQ broke Ireland up into four different war zones to encourage activity in quieter areas.

In late 1921, the IRA was organized a second time. This time, GHQ created divisions. Division commanders were responsible for large swaths of territory, similar to the war zones created earlier that year. The purpose of the divisional commanders was to increase the likelihood of brigade and battalion coordination, make the IRA feel like it was growing into a real army, but still allowed (and encouraged) independent command, and transplant some of the administrative burden from GHQ to the divisional commanders. This was especially important if something were to happen to GHQ.

You can listen to season 1 to learn about specific battles. For the purpose of this recap, all you really need to know is that the IRA went from singular ambushes lead by ambitious local commanders to coordinated ambushes, assassinations (the most famous being Bloody Sunday carried out by Collins’ personal assassins), prison riots, hunger strikes, and outright assaults on barracks in the rural areas of Ireland. In addition to these military developments, the Dail supported the war effort by retaining the people’s support and maintaining the functionality of the Dail Courts and the Dail Loans.

The British responded by implementing martial law, launching large scale searches and arrests, curfews, roadblocks, and interment on suspicion and by creating the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries. The Black and Tans arrived in Ireland on March 25th, 1920. They were meant to reinforce the RIC and recruited mostly British veterans. They were called black and tans because of their uniform (dark green which appeared black and khaki. They weren’t special forces, just normal reinforcements which may explain why they were known for their brutality and violence. The auxiliaries were founded in July 1920s as a paramilitary unit of the RICs. It consisted of British officers and were meant to serve as a mobile strike and raiding force. 2,300 men served during the war and they were deployed in the southern and western regions of Ireland – where fighting was the heaviest. They were absolute brutes, known for arson and cruelty.

The British wanted to subdue Ireland by the May 1921 election, so they sent over fifty-one battalions of infantry, however, confusion over the military’s role, the RIC’s role, an inability to coordinate amongst the army, RIC, Black and Tans, and Auxiliaries, and the implementation of martial law hurt British efforts.

The IRA were feeling the pressure. In early 1921, they suffered some of their most drastic defeats contributing to poor morale and disgruntlement with the Dail and GHQ. GHQ was losing control over local forces while also trying to maintain a guerrilla war on a shoestring budget. To make matters worse, DeValera returned from America in December 1920 and spent most of 1921 trying to reorganize the IRA and Dail according to his vision. His arrival exasperated already existing tensions amongst several ministers, including Collins, Mulcahy, and Brugha, and threatened to tear the IRA apart from the inside.

Cathal Brugha

[Image description: A sepia toned photo of a small and thin man in a military uniform and a white button down and stripped tie. He has short hair and is clean shaven. Behind him is a blank white wall.]

Despite all of this, by May 1921, the IRA had reached its peak and the crown forces suffered record losses. From the beginning of 1921 to July, the IRA killed 94 British soldiers and 223 police officers. This was nearly double the totals from the last six months of 1920. This was also when the IRA launched their most ambitious attacks such as their attack on the Shell factory which amounted to 88,000 pounds in damage and their assault on the Dublin Custom House destroying the inland revenue, stamp office, and stationery office records. In addition to these attacks, the IRA increased the number and sophistication of their attacks in what is now Northern Ireland. However, these attacks could be self-defeating as they only enraged the Ulster Volunteers and left the Catholic population at the mercy of angry Unionists. These attacks would convince the British that Ireland was already partitioned (even if Sinn Fein and the IRA refused to acknowledge the fact) and it was in their interest to protect Northern Ireland from IRA incursions. This meant another army and more money that could have been spent elsewhere.

It was clear that neither side could win this conflict through military efforts alone.

References:

The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence by Charles Townshend, 2014, Penguin Group

Fatal Path: British Government and Irish Revolution 1910-1922by Ronan Fanning, 2013, Faber & Faber

Richard Mulcahy: From the Politics of War to the Politics of Peace, 1913-1924 by Padraig O Caoimh, 2018, Irish Academic Press

A Nation and Not a Rabble: the Irish Revolution 1913-1923by Diarmaid Ferriter, 2015, Profile Books

Eamon DeValera by Ronan Fanning, 2016, Harvard University Press

#Irish War of Independence#Irish History#Michael Collins#Richard Mulcahy#Irish Republican Army#IRA#Eamon Devalera#Cathal Brugha#Constance Markievcz#easter rising#history blog#queer historian#podcast episode#Spotify

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Screaming rn,

I’m writing a paper and sometimes I just throw some random abbreviation as a place holder for my source citation.

And I scroll up and just see this:

#I’m laughing my ass off omfg#just HOMO SCARE#oh my fucking christ#I’m dying and I need to finish this paper#but this is so fucking funny#queer history#history major#queer historian#writing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creating the Transgender Flag

So today I'll be talking about the history and creation of the trans flag! This will probably be a shorter post but still equally as important of course

The transgender flag was originally created by Monica Helms, a trans woman from America, in 1999. She got the idea from Micheal Page who had created the bisexual flag a year earlier. Helms describes the meaning of each stripe in the flag as:

"The stripes at the top and bottom are light blue, the traditional color for baby boys. The stripes next to them are pink, the traditional color for baby girls. The stripe in the middle is white, for those who are intersex, transitioning or consider themselves having a neutral or undefined gender."

- Monica Helms

The original flag (pictured below) was later donated to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in 2014 by Helms.

Later on, in 2019, Helms published a book in which she expresses shock that her flag design has been adopted so wholeheartedly by the trans community. I'd like to end off this post with that quote.

The speed with which the flag’s usage spread never fails to surprise me, and every time I see it, or a photo of it, flying above a historic town hall or building I am filled with pride.

- Monica Helms

#historian#history#history facts#queer history#gay history#lgbt#lgbtq#lgbtq community#lgbtqia#pride#trans history#transgender history#transgender#trans flag#trans#transgender flag

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Gay pride happens in June and gay wrath happens whenever hbomberguy drops a 3+ hour video essay about a specific topic

#hbomberguy#Just watched the full 4 hour plagiarism video and go OFF you funky bisexual king#Also I feel like people casually mention that Internet Historian and that Blare chick should've gotten mentioned more but honestly#Good on him for taking down Luke Stephens too-- who is now afaik a huge channel for video game news#So anyway video good go watch it and go support queer content creators who are not James Somerton :)#See y'all in 2024 when he drops a 5 hour essay on Onion farming or whatever#Seta speaks#top posts#5k#10k

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

Downsides of becoming a queer historian you don't realise until you are in waaaaay too deep:

sometimes you have to read an article on "TrAnSvEsTiTeS" that was written by a white straight cis-man in, like, the seventies and it's just a guy who took Freud too seriously and is like: Men wear women's clothing because their mothers were ~homosexuals~ (if you know what I mean) who project on their little boys and their fathers were beta b#ches who let the household be run by a woman and didn't protest.

And all that while doing research for your paper that's due in four days that's about a really cool topic like - in this case the question of whether or not St. Mary/Marinos can be understood as a trans person and it's really fascinating because like, you can definitely read Marinos as a trans man from a modern point of view - even though it's always a curious discussion because obviously we can never know what Marinos would have chosen to call themselves. Except that we literally know that he would have rather been punished severely for fornication and fathering than child than tell people that he had a vagina. Like. As in Marinos told noone, they only found out after his death - so, I don't know what you want me to make with that, but that's not very cis. And that's basically what my essay is about. :D

And then there come the 80s and 90s scholars again and there all like this person is definitely a WOMAN - like, what do you mean, SHE lived her whole life as a male monk in a monastery and rather get expelled than tell people about HER vagina that made it impossible for HER to father a child and never told anyone and people only found out SHE was a WOMAN after HER death? Well Obviously SHE was in denial about HEr Womanhood.

Or- my favourite cishet interpretation of the story: well, obviously that story is written for cis men because St. Mary is a personification of the guilt men have for desiring women the shouldn't and acting on that because you see- she was punished for it and she couldn't have done it but it isn't revealed until after her death so men have stories that make them feel guilty and help them stay on the right path.

But like. Seriously. It's an absolut shit-show.

#history#queer history#queer historian#to save you some googgling:#fornication = sleeping with someone you are not married to#hagiography = fancy word of saying the lifestory of a saint#but really#I am having so much fun with this topic#and I am so grateful to my instructor for letting me write about this because it's actually interesting and I am only in my second semester#and my last paper had to be on exactly what my instructor wanted me to write about#not that I didn't bend that rule a little bit and got rewarded for it#but yeah - this is just so much better#well anyways#this is basically just a new way of procrastinating on my paper that's due on saturday :)#so bye#master of procrastination#I mean at least I kept myself from starting to write a dnd campaign or a whole ass new play instead of a paper#so I call that success#oy almost forgot#if you want to know more feel free to ask me questions I love to talk about this#or look up#cross-dressed saints#and especially Marina the Monk#that's yet another name of the person I am writing about#but the one that usually gets me to the right saint#sorry for spamming tags

1 note

·

View note

Text

Okay but like misogyny and gender division aside, I really like how lovers used to call each other friend. Soulmate, boy/girlfriend. Even married couples could say stuff like “ever your friend” and it wasn’t seen as friend zoning or lesser, but rather emphasising their bond and good standing with each other. Just gets me, man

#like the whole ‘historians will call them friends’ would just not be an issue then#like they WERE friends#but they were perhaps also other things to each other#not ‘more’ than friends. just maybe different#or maybe they were more. in a way you will not understand#in a way that isn’t a lover and isn’t a (modern) friend#but that is decidedly in love#not romantic not platonic but certainly love#‘there is no platonic explanation for this’#COWARD. you are admitting to being dumb#aroace#aromantism#asexuality#scatterbrained rambles#arospec#history#history student#historians will say they were close friends#queer

956 notes

·

View notes

Text

We took a wrong turn as a society when we entirely subordinated friendship to romantic love.

"They're just friends" ???

What about this profound human bond is so inferior to you? Must someone really be sticking their dick somewhere before you dare to call it love?

#posting like an 18th century gay man#i have seen one too many bad takes on here from “historians” sharing “”“facts”“”#“they literally said they were FRIENDS - checkmate shippers” and the like#this should not be big news in 2025 but you can love someone and not (want to) fuck them#idk but if two men express mutual love and concern and physical longing and call each other soulmates AND friends#that is love#to me#queer history

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

brought to you by "The Myth of Lesbian Impunity: Capital Laws from 1270 to 1791" by Louis Crompton

when you first start studying queer history: sapphic acts have basically never been criminalized in any western society! so queer women have always had it easier than queer men!

when you delve even the slightest bit deeper: why do we still believe this

(OP cannot control who does and does not reblog this post, but she firmly believes that trans women are women)

#history#lesbian#lgbt#queer history#queer#could it be...misogyny?#of earlier historians not caring enough about women to delve into legal cases concerning us?#and of a long tradition of 'women have it easy in society' fallacies?#I believed this too! for the record! nobody ever gave me reason to question it and I am a PROFESSIONAL HISTORY WORKER!

634 notes

·

View notes

Text

HOTD’s rhaenyra and alicent can act and talk like (ex) lovers, can have the tension and chemistry of two romantically involved people, can follow romantic themes and have an established romantic dynamic despite being two women in a pseudo-medieval setting because they can’t truly be lovers in the eyes of the general audience.

the text (as in the show), showrunners, and actors can insist all they want on the purposeful nature of the romantic codes that inform rhaenyra and alicent’s relationship (knight and lady, star-crossed, disrupted connection, love triangles, paralleled lives, etc.) but the pseudo-medieval setting comes with certain expectations for mainstream Western audiences to buy and the depiction of an explicit, sensitive, tragic female homosexuality has not yet married with this genre.

the show has a fascinating freedom with their interpretation of this adapted relationship. it’s queer because it can’t be queer, not really! rhaenyra and alicent will never kiss or confess love or even touch lest they betray the perceived rules of this pseudo-medieval period and the narrative that literally revolves around succession and birth and reproduction. It’s easy to brush off the intensity of their bond as oh they are literally just like that.

a thorough exploration of queerness in HOTD is seemingly hampered by the setting and the established source material, not to mention the conservative fans. but at the same time the show is afforded the freedom to play around with these queer limitations because:

1. the source material is literally a history book

2. the GA on autopilot will blink and miss the subtle-not-so-subtle implications

3. the narrative is filled to the brim with men to distract from the very explicit lesbian divorce at the center.

anyways. rhaenicent romantic dynamic is trail-blazingly real and purposeful in a show so popular and expensive but only because general audiences can cajole themselves into thinking that this romance is in fact not real nor purposeful. I mean, there’s a war!

#historians will literally call them roommates#never have I seen a show so intentional and acting performances so convincing about a romance but for some reason this is a daily debate#you better put your queer-viators on!#alicent hightower#rhaenyra targaryen#rhaenicent#rhaenyra x alicent#house of the dragon#house of the dragon season 2

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beans Velocci

Gender: Non binary (they/them)

Sexuality: Queer

DOB: N/A

Ethnicity: White - American

Occupation: Historian, biologist, activist, teacher

#Beans Velocci#queerness#nb#nonbinary#enby#lgbt#lgbtq#lgbt+#queer people#lgbt people#non binary#queer#white#scientist#biologist#historian#activist#teacher

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

my pet peeve is those "historians thought they were very good friends" jokes, like obviously for sure there are homophobic historians, but the study of same-sex desire and relationships of the past is also quite complex and you can't often go and simply label people's relationships or identities of time gone by, and sometimes it's more complicated and elusive than "they were a couple" or even "they were in love"

#nor's rambles#being a bit of a queer theorist here#note also that historical research is interpreting source material and source material seldom is straightforward#different historians will likely come to different conclusions#i would also say!!! that i don't think a lot of people really know the history of labels and lgbtq+ knowledge#like lady gaga saying BORN THIS WAY can be liked all the way back to sexologists like havelock ellis saying that homosexuality is innate an#hence not a disease or a crime

558 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russian Colonialism in Central Asia 1860-1890

From 1860 to 1890, Russia conquered Central Asia. What started as crafting a strong border along their Siberian territories grew into the conquest of most of modern day Central Asia.

Russia and Central Asia have a long, intertwined history that altered between coexistence and conflict. The Russians didn’t start expanding eastwards until the 1500s and they didn’t ’t really consider invading the region until the 1700s and even then, it’s contained to the Steppe lands. We don’t really see engagements with major Central Asian powers until the late 1700s/early 1800s. Their approach isn’t systematic or well planned. The Russians are responding to events unfolding, both in the region and from the around the world, as much as they are trying to shape events to fit their own priorities. They don’t fully subdue the region until the 1880s and roughly 30 years later WWI begins. By 1917 the Tsarist Empire collapses, and Russia loses all control over their conquered territories, including Central Asia. It would be up to the Bolsheviks and the various Central Asian republics to determine what relations would look like during the rest of the 20th century.

Early Russian Incursions (1580s-1700s)

As we mentioned, Russia and the various peoples of Central Asia traded and interacted with each other for most of their early history. The Russians did not consider expanding eastwards until the 1500s, starting with the overthrow of the Kazan khanate in 1552 and Astrakhan khanate in 1556 (two main centers of trade for people from all over the world). In 1580, they overthrew the Khanate of Sibr, opening up Siberia and introducing Kazakh peoples to Cossacks and Slavic merchants, and officials.

Peter the Great

[Image Description: A colored painting of a white man with curly brown hair and a mustache leaning against a chair. Behind him is a grey sky. The man is wearing a dark blue military frock coat with a light blue ribbon and a golden and green metal at his thought. His collar and cuffs are a bright red. He holds a sword with his right hand and a map with his left.]

Up until Peter the Great’s reign in 1682, the Russians and Central Asians spent their time learning about each other and establishing centers of trade. Neither saw each other as a source of danger since the Central Asians khanates were more concerned about fighting each other and resisting pressures from Safavid Iran and China whereas Russia was establishing itself as a state.

It was Peter the Great who turned Russia into an empire and pushed into the Central Asia region, sparking conflict with the Bashirs, Astrakhans, Khiva Khanate, and even Iran. Peter ordered several forts to be built along the current Kazakhstan border and took the Volga and Ural lands, encircling Central Asia. Their first proper incursion into the region was within Steppe lands. The Russians tried to implement tribute and oaths of loyalty, but the Kazakh people either resisted or manipulated Russian demands to fit their needs. They often played the Russians against their other enemies such as China, the Zunghar people, and the different Uzbek Khanates. However, the more involved they became with the Russians, the more restricted their political freedom became and by 1730 they officially asked the Russians for their protection.

Kazakhs and Kyrgyz peoples 1700s-1800s

The first Tsarina to truly interact with her Muslim subjects was Catherine the Great. She chose a position of tolerance while enforcing methods of police control. Catherine believed that if she could use the Islamic hierarchy to manage the people, she could instill law and order in the region. As long as she controlled who was recognized by the state as a legitimate source of religious authority, she could control the people and bind Islamic ideals to the Tsarist system. She implemented this policy with the Muslims in Siberia, the Volga and Ural regions, and the Crimea, utilizing the indigenous Tatars. When Russia tried to implement this system with the Kazakhs they ran into issues.

Catherine the Great

[Image Description: A colored painting of a white, big woman with grey hair pinned up and held in place by a golden crown. She is wearing a tan furred dress and a silver necklace with ornaments in the shape of snowflakes.]

Lack of knowledge is a key component in the Russian rule, and they were aware of this. As they incorporated the land, they sent several expeditions into the region to understand the territory, the people, and the benefits they could reap from the area. Ian W Campbell’s book Knowledge and Ends of Empire goes into great detail how much the Russians didn’t know as they conquered the Steppe lands and the efforts, they went through to fill in their knowledge gap.

Since the Kazakhs were nomads, they did not practice a type of Islam recognized by the Russians, so they were unable to utilize any existing religious structure, like they did with the Tatars. Instead, they had to engage with the different tribal leaders and indigenous informers and spies to manage the steppe peoples and enforce a form of sedentary lifestyle (with mixed results).

In an effort to “bring civilization” to the Kazakh people the Russians abolished the hordes and reorganized the land along tribal lines into three regions. They implemented a heavy bureaucracy consisting of auls, townships, and districts. In 1844, the Kazakhs traditional courts were stripped of authority over serious criminal cases and subjected Kazakhs to Russian military courts.

Authority was maintained by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and military governors, which tried their best to manage the theft and abuse the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz peoples experienced from Russians officials and the Cossacks. This abuse seems to have been driven by the lawlessness common to vast frontiers (one can think of the US’s own Wild West as an example) and because most Russians looked down on the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz as inferior people.

Uzbek Khanates 1800-1900

Driven by mistreatment, starvation, and fear of the Russians, many Kazakh peoples found shelter in the Uzbek khanates. By the 1800s, all three khanates were experiencing civil wars and intense rivalries with each other and either ignored or were disinterested in the Russian encroachment. They were vaguely curious about the increase of British visitors but didn’t seem to realize that it meant trouble for their people. To be fair, the British were notoriously bad at trying to enlist the aid of the khanates as can be seen with the Conolloy-Stoddart-Nasrullah affair.

Nasrullah, Khan of Bukhara

[Image Description: An ink drawing of a man in a turban and long, wispy black beards. He also had a drooping black mustache and a white long dress shirt. The paper the painting is drawn on is tan and below the man are words written in Arabic]

Charles Stoddart was sent to Bukhara by the East India Company to win over the emirate, Nasrullah. Instead Nasrullah found him so insulting, he threw him into a bug pit for a few days. Stoddart remained in Bukhara for three years before the Company sent Captain Arthur Connolly to rescue him. Connolly traveled disguised as a merchant, but the Emirate was on alert since Britain was invading Afghanistan at the same time. Around the time Connolly was arrested, the Afghans organized a revolt that drove the British out of their country (only one British survivor made it back to India). Nasrullah wasn’t impressed and felt even more insulted by Connolly’s and Stoddart’s behavior, so he beheaded them when he caught them trying to smuggle letters to India.

Modern historians have poked several holes into the Great Game narrative, and it may be safe to say that the Great Game is more of a reflection of Britain’s own insecurities and fears than reality (with the Russians taking advantage of said fears). At the same time, Russia was feeling insecure compared to the other European states, had a need to make up for the humiliating defeat suffered during the Crimean War, were concerned about the security of their southern frontier, and held racist beliefs about the inferiority of the Central Asian peoples.

Their first attempt was to invade Khiva in 1839, but that ended in disaster. They would not try again until 1858, pushing southward, along the Syr Darya. By 1860 they had taken and established forts in what is modern day Almaty, Kazakhstan and Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. In 1864 Colonel Mikhail G. Cherniaev finished the conquest of the land along the Syr Darya by taking the towns of Yasi and Shymkent. In 1865, he took Tashkent from Kokand, conquering the last bit of Kazakh land.

At this point, we can organize the Russian conquest around three major events: the subjugation of the Bukhara and Khiva Khanates, the abolishment of the Kokand Khanate, and the slaughter of the Turkmen people in the Ferghana valley

Conquering the Bukharan Khanate

However, conquering Tashkent dragged them into the rivalry between Kokand and Bukhara. The Russians wanted to turn Tashkent into a buffer state between themselves and Bukhara while Bukhara hoped the Russians would return the city to them. When Emir Muzzafar sent an envoy to embassy to the Tsar, he was arrested and Muzzafar was told he no longer had the right to speak to the Tsar directly. Muzzafar was stunned and furious so he arrested a Russian diplomat sent from Tashkent. The Russians attacked the Bukharan town of Jizza but returned from lack of supplies. The Bukharans responded by marching on Tashkent but were defeated by the Russians at Irjar. The Russians then took Khujand, cutting off communications between Bukhara and Kokand, preventing a coordinated resistance.

Konstantin Petrovich Von Kaufmann

[Image Description: A black and white lithograph of a white man with a receding hairline. He has a grey bushy mustache. He wears a grey military tunic with epaulettes and several medals. His hands rest on his shoulder hilt.]

To neutralized Kokand, further the Russians a treaty with Kokand granting Russian merchants free trade rights in the khanate and vice versa in Russian Turkestan. However, since Russia’s economy was bigger, this made Kokand an economic vassal.

Bukhara tried to resist the Russians but because of a divided military, internal rebellions, and antiquated technology, Muzzafar was forced to surrender in June 1868. The treaty restored Muzzafar’s sovereignty but took Samarkand away, controlling Bukhara’s main water source. Russian merchants were allowed to conduct business in Bukhara with the same rights as local merchants and Bukhara had to pay a compensation for Russia’s expenses during the war.

While the conquest of the Syr Darya basin and Tashkent had been approved by ministers in St. Petersburg, the Bukharan conflict was decided by officers on the ground. They actually recalled Cherniaev in 1866 only for his replacement, Romanovskii to attack Khujand. In 1867, Romanovskii was replaced by Konstantin Petrovich Von Kaufmann (who was a bit of an asshole) who served as Turkestan’s first governor-general. Despite the fact that its military had gone rogue, the Russians could not tolerate retreating or returning the land. Think about how it would affect its standing amongst the European powers (sarcasm)

Kaufman called his conquered territory Turkestan and made Tashkent as its capital. Given its distant from St. Petersburg, Kaufman enjoyed remarkable independence and was more like an emperor than a civil servant.

Conquering the Khivan Khanate

By 1859, Russia had conquered the North Caucasus and created a port in modern day Turkmenboshi, Turkmenistan. This allowed the Russians to transport goods via the river, instead of making the long and dangerous journey from Khiva to Orenburg. This deeply hurt Khiva’s income and cut into the incomes of the Turkmen who protected or raided the traveling merchants.

That, combined with the Russian conquest of Kokand and Bukhara and Khiva was in serious trouble. Khivan Emir Muhammad Rahim, learned from Bukhara, released all Russian prisoners, and negotiated with Russia for peace. Kaufman, however, wasn’t interested in peace. Instead, he sent message after message to Alexander II to complain about Khiva’s insolence and the danger it posed to Russian merchants, finally getting his permission to launch a military campaign to punish Khiva. In 1872, Kaufman led an invasion of four columns, consisting of over 12,000 men and tens of thousands of camels and horses and attacked Khiva from three directions. The Khivans did not resist vigorously whereas the Turkmen fought viciously.

On June 14th, Muhammad Rahim surrendered and Kaufmen forced him to govern under a Russian led council while he ransacked the palace for personal prizes. On August 12th, 1873, Rahim signed a stricter treaty then the one Muzzafar signed. The treaty forced the khan to acknowledge he was an obedient servant of the Tsar, granted control of navigation over the river Amu Darya to the Russians, and granted extensive privileges to Russian merchants. They also agreed to pay Russian 2.2 million rubles over the course of twenty years.

The Turkmen

While Khiva was subdued, the Turkmen were as rebellious as ever and Kaufman jumped at the opportunity to expand his power and earn more “glory”. In July 1873, he required that the Turkmen pay 600,000 rubles with only two weeks to deliver, knowing it would be impossible to do. When they failed, Kaufman launched an attack on the Yomut, a Turkmen tribe. American journalist Januarius MacGahan reported the following:

This is war such as I had never before seen, and such as is rarely seen in modern days…I follow down to the marsh, passing two or three dead bodies on the way. In the marsh are twenty or thirty women and children, up to their necks in water, trying to hide among the weeds and grass, begging for their lives, and screaming in the most pitiful manner. The Cossacks have already passed, paying no attention to them. One villainous-looking brute, however, had dropped out of the ranks and leveling his piece as he sat on his horse, deliberately took aim at the screaming group, and before I could stop him, pulled the trigger. Fortunately, the gun missed fire, and before he could renew the cap, I rode up and cutting him across the face with my riding-whip, ordered him to his sotnia. - Januarius MacGahan

By end of July, the Turkmen agreed to pay and Kaufman extended the deadline.

Even though Russian conquered Kokand, they had a hard time implementing political control, having to deal with a still strong khanate and an angry populace. The death of the old khan, Alim Qul, allowed Khudoyar Khan to return to rule. However, his close ties with Russia inspired a revolt amongst the Kokandi Kyrgyz nobles who drove him out in August 1875. The Russians placed his son, Nasruddin on the throne, but another revolt drove him out as well and Russia was stuck with a region deep in civil war with no clear factions.

Kaufman, worried that Bukhara or the British would take advantage, launched another military campaign. This campaign was particularly bloody, with Major-General Mikhail D. Skobelev making it a point of murdering civilians to crush all future rebellions. Vladimir P. Nalivkin, a young officer serving under Skobelev wrote the following of an incident where Skobelev ordered his Cossacks to charge fleeing civilians while their divisional commander countermanded the order. He then told Nalivkin to chase after a Cossack bearing down on an unarmed man carrying his child. Nalivkin wrote the following:

“With a cry “leave him alone! Leave him alone!” I rushed towards the man (sart), but it was already too late: one of the Cossacks brought down his sword, and the unfortunate two or three-year-old child fell from the arms of the dumbfounded, panic-striken man, landing on the ground with a deeply cleft head. The man’s arms were apparently cut. The bloody child convulsed and died. The man blankly stared now at me, now at the child, with wildly darting, wide eyes. God forbid that anyone else should have to live through the horror I lived through in that moment. I felt as though insects were crawling up my spine and cheeks, something gripped me by the throat, and I could neither speak nor breathe. I had seen dead and wounded people many times; I had seen death before, but such horror, such abomination, such infamy I had never been seen with my own eye: this was new to me.” - Vladimir P. Nalivkin

The war ended in 1876 with the bombing of Andijan, which Skobelev described himself as a pogram. Kaufman abolished the Kokand Khanate on February 19th, the same day as the anniversary of Alexander II’s ascension to the throne. He renamed the region the Ferghana District and named Skobelev its governor.

Finally, the Russians finished their conquest by subjugating the Turkmen Tekke tribes who lived around the oases in the Qara Qum desert. The reason for the attack was geopolitical. The Russians had won a war against the Ottoman Empire in 1878 but the British prevented the Russians from seizing Constantinople, so Kaufman was ordered to march on India.

Kaufman sent three columns towards Afghanistan and Kashmir and a fourth column heading towards the town on Kelif on the Amu Darya. To get there, they had to march through Tekke Turkmen territory. The attack was called off a week later, but the Russians continued south to establish a line of forts on the border of Iranian Khurasan. These forts were vulnerable to Turkmen attack, so the Russians laid siege to the town of Gok Tepe.

Their artillery was devastating but the Russians were defeated by fierce Turkmen fighting when they decided to storm the town. Skobelev led a revenge campaign in November 1880, finally blowing up the walls of Gok Tepe in January 1881. He ordered the Cossacks to pursue and kill anyone fleeing. The total cost was 14,500 Turkmen killed, including many non-combatants, destroying the Tekke Turkmen for decades and finalizing Russian control over Central Asia.

References

For Prophet and Tsar: Islam and Empire in Russia and Central Asia by Robert D. Crews Published by Harvard University Press, 2006

The Rise and Fall of Khoqand: Central Asia in the Global Age 1709-1876 by Scott C. Levi Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017

The Bukharan Crisis: a Connected History of 18th Century Central Asia by Scott C. Levi Published by University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020

Tatar Empire: Kazan’s Muslims and the Making of Imperial Russia by Danielle Ross Published by Indiana University Press, 2020

Russia and Central Asia: Coexistence, Conquest, Coexistence by Shoshana Keller Published by University of Toronto Press, 2019

Russia’s Protectorates in Central Asia: Bukhara and Khiva, 1865-1924 by Seymour Becker, Published by RoutledgeCurzon, 2004

Tournament of Shadows: the Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia by Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac Published by Basic Books, 1999

#Season 2: Central Asia#Central Asia#Central Asian History#Russian Colonialism#Podcast Episode#Blog Post#history blog#queer historian#queer podcaster#Spotify

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

I can’t stop imagining that Machete is briefly brought up in Dog 21st Century high school history class, and one student hyperfixates on him being gay with Vasco: historians and their Sapphos.

That would be awfully cute ;_;

But I don't know how likely it would be that either of them left any significant marks on history books, and if there were mentions of them somewhere, would there be enough documentation about their personal lives for people to connect the dots between them. They were, after all, extremely careful about keeping their relationship secret.

Vasco commissioned a few posthumous portraits of Machete after his death, those might've survived to modern day. If historians were able to trace their origin all the way to back to Vasco it could potentially back up theories about there having been something going on between the two.

They maintained active correspondence for over a decade, but written records are easily forgotten, lost and destroyed. It's fun to think about the possibility of a huge stack of some 400 year old deeply personal letters sitting abandoned somewhere, waiting to be rediscovered.

But if I wanted to go for the tragic route, I could also say that when Machete was starting to come apart at the seams and he was sure his enemies had caught him and he was moments away from the end, he burned all of Vasco's love letters in a fit of paranoia and paniced dread, hoping it would save Vasco from being exposed and incriminated with him. Then it turned out to be a false alarm. I don't think he'd ever recover from destroying something so irreplaceable with his own hands, it was like he had murdered Vasco himself. But I don't know if I have the heart to do that to them, to me it's so sad it borders on off-putting. But it would be tragic.

#answered#organchaos#Vaschete lore#I don't think they'd be ~queer icons~#either they left no traces or there's just enough material that some historians suspect that they could've been together#the classic they were very good friends scenario

227 notes

·

View notes

Text

women loving women, oil on canvas

sapphic love preserved in art eternally

#wlw#wlw post#wlw pride#lesbian#queer#wlw art#historians will say they were close friends#sapphic#lgbtqia#lgbtqia pride#credit to the artists

113 notes

·

View notes