#prison and corrections in america

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

click the header to see the entire photoset, which explains what happened on which days and why.

One of the many guards beaten by inmates on the first day of the riots is loaded into an ambulance by New York State Police troopers and local police.This is a part of americas bloody history that they want to quietly disappear.

AMERICA YOU DID THIS..

Inmates raise their fists in solidarity while one of their leaders speaks with Commissioner of Corrections Russell Oswald on September 10, 1971.

A debris-riddled corridor in one of the four Attica cell blocks is littered with shattered glass and broken equipment on the second day of the riot.

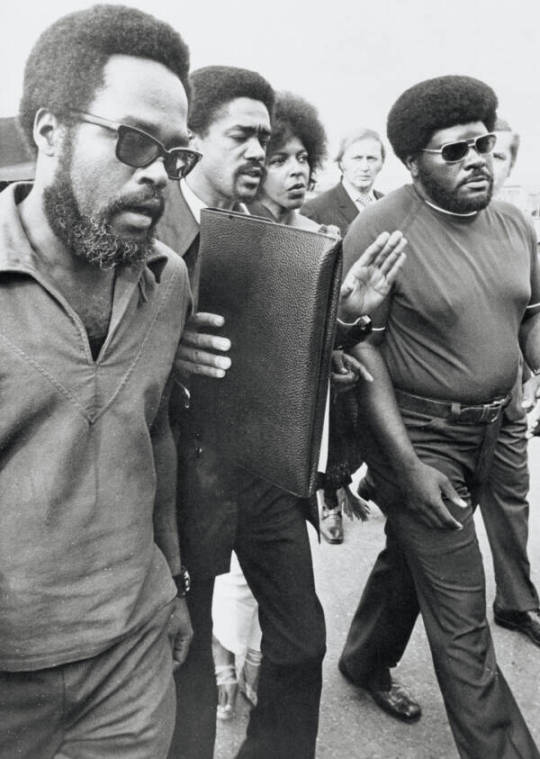

Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale (second from left) arriving at the Greater Buffalo International Airport on September 11, 1971. After meeting with Attica inmates, he proposed accepting the deal put forth by the Commissioner of Corrections — which would have granted the prisoners 28 of their 33 demands.

Heavily armed authorities position themselves on a platform overlooking Attica's D Yard — which had become the main stronghold of the 1,281 rioting inmates.

Inmates had drawn up a manifesto listing 33 demands, from better living conditions to amnesty for the uprising. They elected five prisoners to serve as leaders with negotiating powers, while many others were instructed to work as security or medics. Here, they express solidarity during the negotiation process.

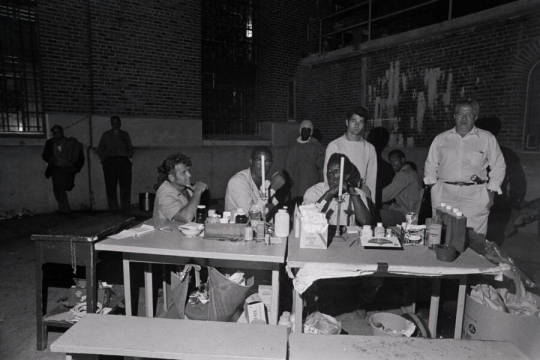

This makeshift hospital station was one of the internal services that prisoners set up during the riot. These services would be widely documented by journalists who were invited into the prison to oversee the uprising.

Inmates barricading themselves in one of the corridors leading to cell block D on September 10, 1971. They had just finished discussions with correctional officers regarding the terms of their impending negotiations. The figure in black standing in the center was one of the television cameramen that inmates allowed into the prison to document events.

National Guardsmen donning gas masks as they prepare to storm the facility on September 13, 1971. Protected from the tear gas that had been delivered via helicopter, they would brazenly open fire on both inmates and hostages in the yard.

One of the military helicopters flying over the prison's D Yard to deploy tear gas. Moments later, hundreds of troops, officers, and guards would storm the prison, firing off rounds with abandon — and killing 10 of their own men in the process.

The immediate aftermath of the riots saw inmates stripped of their clothes and forced to stand with their hands above their heads. A week after the riot had ended, inmates were allegedly beaten by the guards. The McKay Commission used this image during their four-day hearings on the fiasco

The charred hat of an Attica prison guard — and a bullet hole in the railing enclosing the D Yard.

#33 Pictures Of The Bloody Attica Prison Riot That Left 43 People Dead#attica prison massacre#attica prison#ny#rockerfeller#prison rights#prison and corrections in america#human rights

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Press Conference on Jail Deaths in Minnesota Department of Corrections

#usa#america#october#minnesota#Minnesota Department of Corrections#humanrights#joe biden#deathsincustody#jail deaths#jail#prison#incarceration#incarcerated people#incarcerated women#class war#united states#unitedstateofamerica#unitedsnakes#native american#amerikkka#amerika#corruption#corrupt politicians#corrupt police#1312#acab#all cops are bastards#all cops are bad#anti police#anti cop

0 notes

Text

TSFF: Insight Prison Project

Prison education is essential if we want inmates to be able to be successful on the outside. And not commit any further crimes and not hurt any further any innocent people because now they know. There’s no successful future for them as criminals that they are hurting themselves and their families while in prison. As they and their families are much better off with them on the outside living…

youtube

View On WordPress

#America#American Corrections System#American Prison System#Prison Reform#Prison Rehabilitation#United States#Youtube

0 notes

Text

This phenomenon of so called Leftists throwing up their hands at the tiniest pushback, or criticism, or suggestions on how to not actively be antisemitic needs to be studied. Because what do you mean instead of just accepting that an antisemitic troll claiming to be on your side said "Zionist Occupied Government" and denouncing this and moving on with your life... you double down, defend, and deflect. It's classic DARVO, but like, when people are very patiently and slowly explaining how this is a literal KKK Nazi white supremacist fascist phrase, it's not enough? You don't care?

It's clear that the "pro Palestinian" left have been fully infiltrated by fascists, both Western fascists who have always been nakedly antisemitic and are finding the perfect avenue to mainstream their Jew hatred... and Islamist fascists who simply never cared that Jews are a global minority group that has faced oppression and violence in multiple different continents, they don't care about social justice or fundamental human rights. It's not part of their intellectual tradition.

The "pro" Palestine movement has been captured by people who have decided that a) Palestine is emblematic of all of the problems of the world, and that b) every Jew is worth sacrificing to correct these problems, because c) if Palestine is emblematic, aren't Zionists responsible for everything then?

Now the prevailing thought is that someone should be able to call for violence against Jews, someone should be able to harass or even assault Jewish Americans, because bringing it up, complaining, taking a stand, that's the equivalent of telling them you like children blowing up, you like hundreds of thousands of people being homeless and food insecure, you like prisoners being detained in Guantanamo conditions without due process, where anyone can torture them as revenge even if there's no proof they're an actual Hamas member.

Is there a reason they argue like Republican Fox News addicts? I guess that kind of explains how easily the "movement" is falling apart to literal fascists.

They say "nobody cares about your hurt feelings ZIONIST!" if you mention literal stabbings and firebombs. They say "but we should talk about how pervasively synagogues indoctrinate the vast majority of Jewish people with Zionist ideology." They roll their eyes because "don't you know Palestinians are suffering 200x what these cushy American Jews could even imagine?" Facts don't care about your feelings uwu~

But at the end of the day, they care a lot about their own feelings, much more so than the facts. They feel entitled to hate all Jews all over the planet, to secretly revel in antisemitic rhetoric and acts, to want to take out their impotent frustration and despair on any and all Jews they'd like. This is very much about their feelings and not any Jewish people's feelings.

They've been waiting for this, or many of them never cared at all. Now it's finally Leftist to quote Nazis and openly make fun of Jews who are getting stabbed. Now it's finally Leftist to call for incinerating all of Israel and maybe we should consider a lot of Diaspora Jews too, you know they can't be trusted! Oh but don't forget to honor the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, innocent civilians should never have been targeted by America's vicious imperial violence!

The fact that it took this substantial contingent of watermelon twitter less than a year to go full mask off like this... is that revealing or troubling?

717 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prison-tech company bribed jails to ban in-person visits

I'm on tour with my new, nationally bestselling novel The Bezzle! Catch me in BOSTON with Randall "XKCD" Munroe (Apr 11), then PROVIDENCE (Apr 12), and beyond!

Beware of geeks bearing gifts. When prison-tech companies started offering "free" tablets to America's vast army of prisoners, it set off alarm-bells for prison reform advocates – but not for the law-enforcement agencies that manage the great American carceral enterprise.

The pitch from these prison-tech companies was that they could cut the costs of locking people up while making jails and prisons safer. Hell, they'd even make life better for prisoners. And they'd do it for free!

These prison tablets would give every prisoner their own phone and their own video-conferencing terminal. They'd supply email, of course, and all the world's books, music, movies and games. Prisoners could maintain connections with the outside world, from family to continuing education. Sounds too good to be true, huh?

Here's the catch: all of these services are blisteringly expensive. Prisoners are accustomed to being gouged on phone calls – for years, prisons have done deals with private telcos that charge a fortune for prisoners' calls and split the take with prison administrators – but even by those standards, the calls you make on a tablet are still a ripoff.

Sure, there are some prisoners for whom money is no object – wealthy people who screwed up so bad they can't get bail and are stewing in a county lockup, along with the odd rich murderer or scammer serving a long bid. But most prisoners are poor. They start poor – the cops are more likely to arrest poor people than rich people, even for the same crime, and the poorer you are, the more likely you are to get convicted or be suckered into a plea bargain with a long sentence. State legislatures are easy to whip up into a froth about minimum sentences for shoplifters who steal $7 deodorant sticks, but they are wildly indifferent to the store owner's rampant wage-theft. Wage theft is by far the most costly form of property crime in America and it is almost entirely ignored:

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/jun/15/wage-theft-us-workers-employees

So America's prisons are heaving with its poorest citizens, and they're certainly not getting any richer while they're inside. While many prisoners hold jobs – prisoners produce $2b/year in goods and $9b/year in services – the average prison wage is $0.52/hour:

https://www.dollarsandsense.org/archives/2024/0324bowman.html

(In six states, prisoners get nothing; North Carolina law bans paying prisoners more than $1/day, the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution explicitly permits slavery – forced labor without pay – for prisoners.)

Likewise, prisoners' families are poor. They start poor – being poor is a strong correlate of being an American prisoner – and then one of their breadwinners is put behind bars, taking their income with them. The family savings go to paying a lawyer.

Prison-tech is a bet that these poor people, locked up and paid $1/day or less; or their families, deprived of an earner and in debt to a lawyer; will somehow come up with cash to pay $13 for a 20-minute phone call, $3 for an MP3, or double the Kindle price for an ebook.

How do you convince a prisoner earning $0.52/hour to spend $13 on a phone-call?

Well, for Securus and Viapath (AKA Global Tellink) – a pair of private equity backed prison monopolists who have swallowed nearly all their competitors – the answer was simple: they bribed prison officials to get rid of the prison phones.

Not just the phones, either: a pair of Michigan suits brought by the Civil Rights Corps accuse sheriffs and the state Department of Corrections of ending in-person visits in exchange for kickbacks from the money that prisoners' families would pay once the only way to reach their loved ones was over the "free" tablets:

https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2024/03/jails-banned-family-visits-to-make-more-money-on-video-calls-lawsuits-claim/

These two cases are just the tip of the iceberg; Civil Rights Corps says there are hundreds of jails and prisons where Securus and Viapath have struck similar corrupt bargains:

https://civilrightscorps.org/case/port-huron-michigan-right2hug/

And it's not just visits and calls. Prison-tech companies have convinced jails and prisons to eliminate mail and parcels. Letters to prisoners are scanned and delivered their tablets, at a price. Prisoners – and their loved ones – have to buy virtual "postage stamps" and pay one stamp per "page" of email. Scanned letters (say, hand-drawn birthday cards from your kids) cost several stamps:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/14/minnesota-nice/#shitty-technology-adoption-curve

Prisons and jails have also been convinced to eliminate their libraries and continuing education programs, and to get rid of TVs and recreational equipment. That way, prisoners will pay vastly inflated prices for streaming videos and DRM-locked music.

The icing on the cake? If the prison changes providers, all that data is wiped out – a prisoner serving decades of time will lose their music library, their kids' letters, the books they love. They can get some of that back – by working for $1/day – but the personal stuff? It's just gone.

Readers of my novels know all this. A prison-tech scam just like the one described in the Civil Rights Corps suits is at the center of my latest novel The Bezzle:

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865878/thebezzle

Prison-tech has haunted me for years. At first, it was just the normal horror anyone with a shred of empathy would feel for prisoners and their families, captive customers for sadistic "businesses" that have figured out how to get the poorest, most desperate people in the country to make them billions. In the novel, I call prison-tech "a machine":

a million-armed robot whose every limb was tipped with a needle that sank itself into a different place on prisoners and their families and drew out a few more cc’s of blood.

But over time, that furious empathy gave way to dread. Prisoners are at the bottom of the shitty technology adoption curve. They endure the technological torments that haven't yet been sanded down on their bodies, normalized enough to impose them on people with a little more privilege and agency. I'm a long way up the curve from prisoners, but while the shitty technology curve may grind slow, it grinds fine:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/24/gwb-rumsfeld-monsters/#bossware

The future isn't here, it's just not evenly distributed. Prisoners are the ultimate early adopters of the technology that the richest, most powerful, most sadistic people in the country's corporate board-rooms would like to force us all to use.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/02/captive-customers/#guillotine-watch

Image: Cryteria (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

--

Flying Logos https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Over_$1,000,000_dollars_in_USD_$100_bill_stacks.png

CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

--

KGBO https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Suncorp_Bank_ATM.jpg

CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#prison#prison-tech#marty hench#the bezzle#securus#captive audiences#St Clair County#human rights#prisoners rights#viapath#gtl#global tellink#Genesee County#michigan#guillotine watch#carceral state#corruption

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

I don't think I have it in me to be an abolitionist because I read that horrible story about the trans teen murdered in South Carolina and my knee jerk reaction is, those people should rot in jail, ideally forever, or worse. No matter how I look at it I can't make myself okay with the idea that you should be allowed to steal someone's life in such a horrible way and then just go back to enjoying your life. Some stuff is just too over the top evil.

You can have whatever emotions you want about that person's murderous actions, but the reality is that the carceral justice system is one of the largest sources of physical, emotional, and sexual torment for transgender people on this planet.

Transgender people are ten times more likely to be assaulted by a fellow inmate and five times more likely to be assaulted by a corrections officer, according to a National Center for Transgender Equality Report.

Within the prison system, transgender people are frequently denied gender-affirming medical care, and housed in populations that do not match their identity, which increases their odds of being beaten and sexually assaulted.

The alternative to being incorrectly housed with the wrong gendered population is that transgender people are also frequently held in solitary confinement instead, often for far longer periods on average than their non-transgender peers, contributing to them experiencing suicide ideation, self harm, acute physiological distress, a shrunk hippocampus, muscculoskeletal pain, chronic condition flare-ups, heart disease, reduced muscle tone, and numerous other proven effects of solitary confinement.

The prison system is also one of the largest sites of completely unmitigated COVID spread, among other illnesses, with over 640,000 cases being directly linked to prison exposure, according to the COVID prison project.

We know that number is rampantly under-estimated because prisoners, especially trans ones, are frequently denied medical care. And even basic, essential physical care. Just last year a 27-year-old Black man named Lason Butler was found dead in his cell, having perished of dehydration. He had been kept in a cell without running water for two weeks, where he rapidly lost 40 pounds before perishing. His body was covered in rat bites.

This kind of treatment is unacceptable for anyone, no matter who they are and what they have done, and I shouldn't have to explicitly connect the dots for you, but I will. One in six transgender people has been to prison, according to Lambda Legal. One in every TWO Black transgender people has been to prison. One in five Black men go to prison in America.

THIS is the fate you are consigning all these people to when you say that prisons must exist because there are really really bad people out in the world. We should all know by not that this is not how the carceral justice system works. Hate crime laws are under-utilized, according to Pro Publica, and result in few convictions. The people who commit transphobic acts of violence tend to be given softer sentences than the prisoners who resemble their victims.

We must always remember that the violent tools of the prison system will be used not against the people that we personally consider to be the most "deserving" of punishment, but rather against whomever the state considers to be its enemy or to be a disposable person.

You are not in control of the prison system and you cannot ensure it will be benevolent. You are not the police, the judge, the jury, or the corrections officers. By and large, the people who are in these roles are racist, transphobic, ableist, and victim-blaming, and they will use the power and violence of the system to terrorize people in poverty, Black people, trans people, "mad" people, intellectually disabled people, women, and everyone else that you might wish to protect from harm with a system of "punishment." Nevermind that incaraceration doesn't prevent future harm anyway.

You can't argue for incarceration as the tool of your revenge fantasies, you have to argue for it as the tool that it actually is. The purpose of a system is what it does. And the prison system's purpose has never been to protect or avenge vulnerable trans people. It has always been to beat them, sexually assault them, forcibly detransition them, render them unemployable, disconnect them from all community, neglect them, and unperson them.

780 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHY AMERICAN PRISONERS HAVE TO WEAR A UNIFORM

In (almost) all American prisons, prisoners are now required to wear a uniform (again). This uniform is either a two-piece, consisting of trousers and a shirt, with the trousers held up by an elastic band around the waist, or a one-piece, a kind of overall, a so-called jumpsuit, which is usually closed at the front with a row of snaps. Nowadays, these uniforms have short sleeves; in cold weather, prisoners often are allowed to wear a sweater underneath.

The appearance of prison uniforms in the United States varies from state to state and from institution to institution, and is usually determined by the prison authorities themselves. The uniforms are either made in a solid color - preferably orange, but also red, pink, green, blue, gray and yellow - or as a horizontally striped kind of zebra suit, colloquially known as 'prison stripes', with black and white stripes being the standard, but green and white, orange and white and red and white also occur.

Such prison stripes have become very popular again, especially in recent decades, and harks back to the classic convict uniform that was common at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. The current striped uniform differs from this in two respects: the sleeves were still long at the time, and the stripes were much narrower. The jumpsuit version did not exist in the past either.

Prison uniforms are common in most countries, although they are usually not as strikingly designed as the American ones; as far as I know, prison stripes aren’t in use nowadays in any other part of the world. In Europe, it is usually a two-piece uniform in a grey or blue colour, which does not make a prisoner stand out very much in a larger crowd. This one underneath is from England.

In America, too, khaki or a blue type of denim was common in many prisons until a few decades ago. Regularly, it was even still permitted to wear your own clothes, at least in your own cell(block). That has changed. This picture shows a working crew of inmates in Texas.

What are the main reasons why prison authorities require all prisoners to wear a (conspicuous) uniform (permanently)? This is not only done – that morally controversial motive is often certainly present in the background – from the point of view of the call for a certain stigmatization, to make the wearer of such a uniform a social outcast, both to make him feel that himself, and to show him that way to others, the latter as a warning: watch out for this guy.

There are also a number of rational arguments for doing this. Searching for information on the internet, I come to the following motives based on various sites

1.First of all, safety. A (conspicuous) uniform makes a prisoner easily recognizable as such. Bright colours also make him clearly visible from a greater distance. It reduces the risk of escape attempts, because a prisoner is also recognizable to outsiders, and in his uniform it is less easy to mingle with the public unseen.

This is extra important because many prisoners - although usually only those with lighter sentences, and only those who are not considered really dangerous - do community work outside the prison during the day, as cleaning roads or digging fenches.

In order to prevent any escape attempts, they almost always have to wear leg-irons, but a recognizable uniform puts a stop to this too.

This recognizability is increased because the name of the correctional institution is usually printed in capital letters on the back of his uniform, in the case of prison stripes often in read.

Incidentally, that is one reason why prison stripes - also the standard outfit for the chain-gang - have become popular in that case. Since road workers often wear orange clothing, a prisoner in an orange uniform can be more easily confused by the general public. With prison stripes, that risk does not exist. They stand out in the crowd.

2. A uniform emphasizes the equality of all prisoners, and also the sharp distinction with the guards. It makes things much clearer for the latter; the risk of confusing the inmates with visiting outsiders (family, workers, doctors) is then minimal.

The obligation to wear a uniform moreover prevents the development of a visible hierarchy among the prisoners, which can be expressed in the wearing of expensive brand clothing; a discussion that also plays a role with regard to school uniforms. The risk of theft or violent robbery of each other's clothing is thus nil.

A uniform also strengthens the mental awareness of the inmates themselves that they are prisoners now, and thus has a positive influence on their behaviour: they become more compliant, as confirmed by testimonies of their own. This awareness of the loss of their citizen identity together with the loss of their freedom becomes even stronger if their prison number is printed on their uniform too.

A uniform hairstyle – in a number of American prisons, all new prisoners are not only forced to put on a uniform immediately upon arrival, but then also get a complete headshave – also contributes greatly to this. Those two pics underneath shows this transformation, showing a new inmate from Oklahoma before and after his make-over.

3.In line with this: a prison uniform also somewhat prevents gang formation – a major problem in American prisons – because gang members usually want to distinguish themselves by external markings.

The more strictly the uniform requirement is enforced, including THE WAY in which the uniform is worn – in the case of a two-piece shirt tucked into, or not tucked into, the pants, in the case of a jumpsuit all the snaps closed to the last, not only when going to court – the less possible this is. Prisoners are also always explicitly forbidden to make any changes to their uniform themselves, or to provide it with any 'decoration' (which could after all form a certain code).

4.With a prescribed prison uniform, which often (but not always) includes certain footwear, the prison authorities can ensure that all prisoners wear the clothing that, according to the circumstances, is the most practical and safest. No belts in the trousers (but elastic) or laces in the shoes, to prevent suicide. Cotton slippers or plastic sandals, to make it more difficult to run away quickly outside.

Sturdy short boots are often prescribed as work shoes, especially for the chain-gang, because in this case a heavy chain, secured with a padlock, is fastened around the (left) ankle of the prisoner.

Clothing with a minimum number of pockets, so that concealing weapons (and this can also be a knife from the kitchen) or contraband becomes much more difficult. In the two-piece uniform, the trousers have no pocket, the shirt only one, for a handkerchief or glasses. The same applies to the jumpsuit: a small breast pocket for that purpose is all, nothing more.

Jumpsuits have the advantage from a security perspective that they are not only a real eyecatcher, but also that they take a little longer to get rid of (to exchange for other clothing on the run) and offer more protection to the prisoner himself against potential anal rape; with a two-piece uniform, trousers can be pulled down by force more quickly.

5.A fixed uniformstyle also, on the other hand, offers the prison authorities the possibility to differentiate between prisoners themselves, with colour codes. It makes it possible to place prisoners of very different kind who live together in visible categories, from more to less (escape) dangerous. This is also useful for the guards, because then they know more easily who they should pay special attention to. Red in that case usually means dangerous, green safe.

This can also be done in the striped version, where black and white is standard, and red and white (or orange and white) is then also usually considered the biggest security risk, green again as the lowest.

#prisoner#inmate#jail#prison uniform#prison#handcuffs#shackles#handcuffed inmate#leg irons#prison stripes#prison jumpsuit#striped prison uniform#orange prison uniform#orange prison jumpsuit#striped jumpsuit#striped prison jumpsuit#black and white striped jumpsuit

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

This April [2021], the Iowa Department of Corrections issued a ban on charities, family members, and other outside parties donating books to prisoners. Under the state’s new guidelines, incarcerated people can get books only from a handful of “approved vendors.” Used books are prohibited altogether [...].

In 2018, the Michigan prison system introduced an almost identical set of rules, and Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Washington have all made attempts to block book donations, which were only rolled back after public outcry. Across the United States, the agencies responsible for mass imprisonment are trying to severely limit incarcerated people’s access to the written word [...].

---

The official narrative is that donated books could contain “contraband [...]" -- the language used in Michigan [...]. This is a flimsy justification that begins to fall apart under even the lightest scrutiny. [...] [Contraband] [...] [is] not originating from nonprofit groups like the Appalachian Prison Book Project or Philadelphia’s Books Through Bars. [....] The old cartoon scenario of a hollow book with a saw or a gun inside just isn’t realistic, and its invocation is a sign that something else is going on.

That “something else,” predictably enough, is profit. With free books banned, prisoners are forced to rely on the small list of “approved vendors” chosen for them by the prison administration. These retailers directly benefit when states introduce restrictions. In Iowa, the approved sources include [B&N] and [B-a-M], some of America’s largest retail chains -- and, notably, ones which charge the full MSRP value for each book, quickly draining prisoners’ accounts. An incarcerated person with, say, $20 to spend can now only get one book, as opposed to three or four used ones; in states where prisoners make as little as 25 cents an hour for their labor, many can’t afford even that.

---

With e-books, the situation is even worse, as companies like [GTL] supply supposedly “free” tablets which actually charge their users by the minute to read.

Even public-domain classics, available on Project Gutenberg, are only available at a price under these systems -- and prisons, in turn, receive a 5% commission on every charge. All of this amounts to rampant price-gouging and profiteering on an industrial scale.

---

The rise of these private vendors has also been mirrored by the systematic dismantling of the prison library system. In the last ten years, budgets for literacy and educational resources have seen dramatic cuts, reducing funding to almost nothing [...]. In Illinois, for instance, the Department of Corrections spent just $276 on books across the entire state in 2017, down from an already meager $605 the previous year. (This means, incidentally, that each of the state’s roughly 39,000 prisoners was allotted seven-tenths of a cent.)

Oklahoma, meanwhile, has no dedicated budget for books at all, requiring prison librarians to purchase them out-of-pocket. [...]

---

These practices become all the more abhorrent when you consider the impact books can have behind bars. By now, the social science on their benefits is well-established [...]. [O]ther inmates have reported that reading meant “the difference between just giving up mentally and emotionally and making it through another day, week, or year,” countering the dehumanizing effects of their imprisonment. A book can offer a brief, irreplaceable moment of calm in hellish circumstances. [...]

[There is] a shameful pattern in American society, where many people simply don’t think about the incarcerated on a day-to-day basis, let alone sympathize with their worsening conditions. [...] One of the most common arguments for the American carceral system, and its continued existence, is that of rehabilitation. According to its defenders, a prison is not simply a place of suffering, where unwanted populations are sent to disappear. Nor is it a callous money-making machine, intended to squeeze free labor from them in a regime of functional slavery. Instead, prison rehabilitates -- so the story goes. [...] In these terms, the basic legitimacy of mass imprisonment, and its allegedly positive social role, is taken for granted. [...] But the practice of book banning exposes the lie. Not only do American prisons have little interest in education, healing, and growth, but they will actively prevent them the moment there is a dollar to be made or an ounce of power to be secured.

---

Text by: Alex Skopic. "The American Prison System's War on Reading". Protean (Protean magazine online). 29 November 2021. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Wrong Lesson: That's a lot of cellphones. California needs tighter prison security.

Correct Lesson: That's a lot of cellphones. America needs to stop imprisoning so many people.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Review of Official MCU Timelines: Marvel Cinematic Universe Guidebook

My (unofficial) but logical (the right one) detailed timeline of the Phase One

Review of The Old Official Timeline

This is the review of Phase One dates from Marvel Cinematic Universe Guidebook: The Avengers Initiative.

Note: Fury's Big Week events and dates will be covered in a separate post.

Correct dates are highlighted in blue, and incorrect ones - in red.

Iron Man:

Pages: 7, 18, 24.

✔️ The guidebook starts with contradicting the time periods from the old timeline: the first timeline of the MCU told us that 6 months passed between Tony escaping the cave and "I am Iron Man". The guidebook confirms my conclusion that these events took place within less than a month (May 2 - May 25, 2008), and that "days" rather than weeks or months passed between the Charity Ball and the day Tony fought Stane.

Pages: 10, 22, 27, 66.

❌ We know that Tony was born on May 29, 1970. When his parents died, he was already 21 years old. And until May 29, 1992, he was still 21. The movie doesn't say he became CEO of SI when he turned 21. It says "at 21," so unlike the book, it's not a mistake. Tony had a few months between his parents' death and his 22nd birthday to earn two PhDs. During those months, Stane served as the company's interim CEO. Funnily enough, this stupid mistake will haunt the new official timeline book.

Page 12.

❌ That's not entirely wrong, since it says "nearly", but I did it better. They couldn't work on the armor for three months simply because Tony wasn't able to do it for most of that time. He had to spend two months recovering from his injuries and surgeries, one week creating the reactor and the plans for the armor, and only about three weeks actually building the armor.

Page 19.

✔️ This confirms my conclusion that the reactor change did not occur on Tony's first day home, or even the next day. Tony came home on May 2 and Pepper changed the reactor on May 4.

The Incredible Hulk:

Page 38.

❌ As I determined in The Incredible Hulk timeline, Hulk couldn't have run from Rio to Guatemala in one day. It would take him 3-4 days to get there. Add those days as Hulk to the 17 "without incident" days. So it can't be the same 17 days, but rather 21.

Iron Man 2:

Page 53.

❌ This is what "not thinking" looks like. No, Marvel, there are more than 6 months between May 2008 and May 2010.

Page 57.

❌ It couldn't have been "the next day" because the day after Tony's birthday party was spent with Fury and Howard's treasure chest. That was May 31st (2 days after the party).

P.S. Someday I will look at the other statements (non-date related) in this book, because some of them are truly ridiculous.

Page 58.

✔️ This confirms my timeline, which states that the events of IM2 take place over several weeks, not just one.

Captain America: The First Avenger:

Page 101.

❌ "A year later", Marvel?! From June 14 to November 3, 1943 – only 4.5 months!

Page 108.

✔️ ❌ It's a tough question how long it's been since Rogers went behind the lines to rescue the 107th prisoners. Two options: one day (at least 12 hours of marching) or two days. Clues from the movie fit each of these.

Page 115.

❌ MCU movies are inconsistent on what year this train mission took place. The same movie, CA:TWS, says it was both 1944 and 1945. Tie-in comics Fury's Big Week, say it was no later than 1943 (another reason for me not to take it seriously). This book says March 1945. What we get is that all sources contradict each other. Given the original CA:TFA movie, and both 1944/1945, I can fix this error by saying it was December 31, 1944 - January 1, 1945. Everybody's happy.

Pages 124-125.

❌ A simple typo or the writer forgot the year of the Exposition, which is written on the previous page. It was 1943.

Page 127.

❌ Seriously, Mr. Writer? The guy looks like he's been a drill sergeant for 17 years? It's not even possible to be one that long. Plus he still wears Grade 4 Sergeant insignia, which means he's never been promoted in his "17 years" as a drill sergeant. He is either very bad at his job, which raises another question - why is he still there, or the statement makes no sense. Mr O'Sullivan, or whoever wrote this, Sergeant Duffy's phrase only means that "Nobody's got that flag in 17 years" in general, and does not mean that he was a drill sergeant there all that time!

Why I point this out: This is a good example of contractors taking something from the source material (movie) without using logic. Always use logic, please.

Thor - Thor: The Dark World:

Page 181.

✔️Further confirmation that it's only been two years since the events of the first Thor movie, not three as Fury's Big Week tells us: Thor (November 2011), The Avengers (May 2012), Thor: The Dark World (Fall 2013).

#marvel#mcu#tony stark#iron man#the avengers#iron man 2#the incrediable hulk#thor#captain america the first avenger#steve rogers#captain america#hulk#bruce banner#Marvel Cinematic Universe Guidebook#mcu timeline

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today, January 6th 2024, is the perfect day to make purchases at Overstock.com AND then donate to organizations supporting the unarmed Americans who were waved into the Capitol, unnecessarily pepper sprayed, unnecessarily shot with rubber bullets & smoke bombed to create the illusion of a Capitol Hill riot.

Christmas Miracle: Patrick Byrne, Overstock CEO, offers matching $500,000 donation to January 6 Legal Defense. $250,00 via GIVE SEND GO and $250,000 to Stand In The Gap.

Give Send Go Matching Fund

Stand in the Gap

Stand in the Gap is a non-profit foundation dedicated to advocating for change in re-entry, family services, and justice reform. We believe in second chances, providing support to individuals transitioning back into society, and working towards a more equitable and compassionate world. Through our programs, partnerships, and advocacy efforts, we strive to make a lasting impact on the lives of those in need and promote systemic change.

Join us in standing for justice and being a voice for the voiceless.

Our Story

On January 6, 2021, a historic day unfolded in our nation's capital that will be etched in history. As the foundation of our nation was put to the test, many individuals heeded the call to stand up for their rights, their future, and their beliefs. However, the aftermath saw the government taking action against them, leading to a series of events that unveiled the deep-seated issues within the American justice system.

Before January 6th, many were unaware of just how broken the justice system in America truly was. The January 6th defendants and their advocates soon realized that this injustice had persisted for far too long.

In September of 2021, The Real J6 was founded with a mission to give a voice to the voiceless. Its primary focus was to shine a light on the treatment of January 6th defendants at the hands of their own government. However, as the organization delved deeper into this mission, it became clear that there were numerous unmet needs for the defendants and their families. This realization led to the creation of Stand in the Gap.

Shane Jenkins, the co-founder of Stand in the Gap, possesses a unique perspective on the challenges within the incarceration system and the broken nature of the justice system. His life story, marked by several run-ins with the law prior to January 6th, is one of transformation and redemption. Raised in a religious environment and attending Episcopalian school, Shane's life took a different path due to personal struggles and feelings of abandonment stemming from his adoption and an abusive stepfather. In 2016, while incarcerated and at a low point in his life, Shane had a transformative encounter with CHARM – Christ's Hope And Reconciliation Ministries. Through CHARM, he found faith and redemption, and his life took a new direction.

Paroled in July 2018, Shane transitioned to a CHARM Prison Ministries transitional house and dedicated himself to a life of faith and service. He became involved in prison ministry, took on leadership roles, and found a supportive community at church. Despite his personal transformation, in 2021, Shane once again found himself facing government action. Since then, he has been incarcerated, ministering to others within the system and working to bring about positive change.

Through the efforts of many individuals including The Real J6, significant improvements have been achieved within the DC Department of Corrections, including changes in visitation policies, COVID restrictions, guard behavior, and even Congressional intervention. Shane's unique perspective and experience are foundational to the mission of Stand in the Gap, as it strives to address the systemic issues within the justice system and provide support to those who have been affected by it.

youtube

#january 6#political prisoners#political protest#overstock#Stand in the Gap#fbi corruption#Patrick Byrne#j6

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Because senator Kamala Harris is a prosecutor and I am a felon, I have been following her political rise, with the same focus that my younger son tracks Steph Curry threes. Before it was in vogue to criticize prosecutors, my friends and I were exchanging tales of being railroaded by them. Shackled in oversized green jail scrubs, I listened to a prosecutor in a Fairfax County, Va., courtroom tell a judge that in one night I’d single-handedly changed suburban shopping forever. Everything the prosecutor said I did was true — I carried a pistol, carjacked a man, tried to rob two women. “He needs a long penitentiary sentence,” the prosecutor told the judge. I faced life in prison for carjacking the man. I pleaded guilty to that, to having a gun, to an attempted robbery. I was 16 years old. The old heads in prison would call me lucky for walking away with only a nine-year sentence.

I’d been locked up for about 15 months when I entered Virginia’s Southampton Correctional Center in 1998, the year I should have graduated from high school. In that prison, there were probably about a dozen other teenagers. Most of us had lengthy sentences — 30, 40, 50 years — all for violent felonies. Public talk of mass incarceration has centered on the war on drugs, wrongful convictions and Kafkaesque sentences for nonviolent charges, while circumventing the robberies, home invasions, murders and rape cases that brought us to prison.

The most difficult discussion to have about criminal-justice reform has always been about violence and accountability. You could release everyone from prison who currently has a drug offense and the United States would still outpace nearly every other country when it comes to incarceration. According to the Prison Policy Institute, of the nearly 1.3 million people incarcerated in state prisons, 183,000 are incarcerated for murder; 17,000 for manslaughter; 165,000 for sexual assault; 169,000 for robbery; and 136,000 for assault. That’s more than half of the state prison population.

When Harris decided to run for president, I thought the country might take the opportunity to grapple with the injustice of mass incarceration in a way that didn’t lose sight of what violence, and the sorrow it creates, does to families and communities. Instead, many progressives tried to turn the basic fact of Harris’s profession into an indictment against her. Shorthand for her career became: “She’s a cop,” meaning, her allegiance was with a system that conspires, through prison and policing, to harm Black people in America.

In the past decade or so, we have certainly seen ample evidence of how corrupt the system can be: Michelle Alexander’s best-selling book, “The New Jim Crow,” which argues that the war on drugs marked the return of America’s racist system of segregation and legal discrimination; Ava DuVernay’s “When They See Us,” a series about the wrongful convictions of the Central Park Five, and her documentary “13th,” which delves into mass incarceration more broadly; and “Just Mercy,” a book by Bryan Stevenson, a public interest lawyer, that has also been made into a film, chronicling his pursuit of justice for a man on death row, who is eventually exonerated. All of these describe the destructive force of prosecutors, giving a lot of run to the belief that anyone who works within a system responsible for such carnage warrants public shame.

My mother had an experience that gave her a different perspective on prosecutors — though I didn’t know about it until I came home from prison on March 4, 2005, when I was 24. That day, she sat me down and said, “I need to tell you something.” We were in her bedroom in the townhouse in Suitland, Md., that had been my childhood home, where as a kid she’d call me to bring her a glass of water. I expected her to tell me that despite my years in prison, everything was good now. But instead she told me about something that happened nearly a decade earlier, just weeks after my arrest. She left for work before the sun rose, as she always did, heading to the federal agency that had employed her my entire life. She stood at a bus stop 100 feet from my high school, awaiting the bus that would take her to the train that would take her to a stop near her job in the nation’s capital. But on that morning, a man yanked her into a secluded space, placed a gun to her head and raped her. When she could escape, she ran wildly into the 6 a.m. traffic.

My mother’s words turned me into a mumbling and incoherent mess, unable to grasp how this could have happened to her. I knew she kept this secret to protect me. I turned to Google and searched the word “rape” along with my hometown and was wrecked by the violence against women that I found. My mother told me her rapist was a Black man. And I thought he should spend the rest of his years staring at the pockmarked walls of prison cells that I knew so well.

The prosecutor’s job, unlike the defense attorney’s or judge’s, is to do justice. What does that mean when you are asked by some to dole out retribution measured in years served, but blamed by others for the damage incarceration can do? The outrage at this country’s criminal-justice system is loud today, but it hasn’t led us to develop better ways of confronting my mother’s world from nearly a quarter-century ago: weekends visiting her son in a prison in Virginia; weekdays attending the trial of the man who sexually assaulted her.

We said goodbye to my grandmother in the same Baptist church that, in June 2019, Senator Kamala Harris, still pursuing the Democratic nomination for president, went to give a major speech about why she became a prosecutor. I hadn’t been inside Brookland Baptist Church for a decade, and returning reminded me of Grandma Mary and the eight years of letters she mailed to me in prison. The occasion for Harris’s speech was the annual Freedom Fund dinner of the South Carolina State Conference of the N.A.A.C.P. The evening began with the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and at the opening chord nearly everyone in the room stood. There to write about the senator, I had been standing already and mouthed the words of the first verse before realizing I’d never sung any further.

Each table in the banquet hall was filled with folks dressed in their Sunday best. Servers brought plates of food and pitchers of iced tea to the tables. Nearly everyone was Black. The room was too loud for me to do more than crouch beside guests at their tables and scribble notes about why they attended. Speakers talked about the chapter’s long history in the civil rights movement. One called for the current generation of young rappers to tell a different story about sacrifice. The youngest speaker of the night said he just wanted to be safe. I didn’t hear anyone mention mass incarceration. And I knew in a different decade, my grandmother might have been in that audience, taking in the same arguments about personal agency and responsibility, all the while wondering why her grandbaby was still locked away. If Harris couldn’t persuade that audience that her experiences as a Black woman in America justified her decision to become a prosecutor, I knew there were few people in this country who could be moved.

Describing her upbringing in a family of civil rights activists, Harris argued that the ongoing struggle for equality needed to include both prosecuting criminal defendants who had victimized Black people and protecting the rights of Black criminal defendants. “I was cleareyed that prosecutors were largely not people who looked like me,” she said. This mattered for Harris because of the “prosecutors that refused to seat Black jurors, refused to prosecute lynchings, disproportionately condemned young Black men to death row and looked the other way in the face of police brutality.” When she became a prosecutor in 1990, she was one of only a handful of Black people in her office. When she was elected district attorney of San Francisco in 2003, she recalled, she was one of just three Black D.A.s nationwide. And when she was elected California attorney general in 2010, there were no other Black attorneys general in the country. At these words, the crowd around me clapped. “I knew the unilateral power that prosecutors had with the stroke of a pen to make a decision about someone else’s life or death,” she said.

Harris offered a pair of stories as evidence of the importance of a Black woman’s doing this work. Once, ear hustling, she listened to colleagues discussing ways to prove criminal defendants were gang-affiliated. If a racial-profiling manual existed, their signals would certainly be included: baggy pants, the place of arrest and the rap music blaring from vehicles. She said that she’d told her colleagues: “So, you know that neighborhood you were talking about? Well, I got family members and friends who live in that neighborhood. You know the way you were talking about how folks were dressed? Well, that’s actually stylish in my community.” She continued: “You know that music you were talking about? Well, I got a tape of that music in my car right now.”

The second example was about the mothers of murdered children. She told the audience about the women who had come to her office when she was San Francisco’s D.A. — women who wanted to speak with her, and her alone, about their sons. “The mothers came, I believe, because they knew I would see them,” Harris said. “And I mean literally see them. See their grief. See their anguish.” They complained to Harris that the police were not investigating. “My son is being treated like a statistic,” they would say. Everyone in that Southern Baptist church knew that the mothers and their dead sons were Black. Harris outlined the classic dilemma of Black people in this country: being simultaneously overpoliced and underprotected. Harris told the audience that all communities deserved to be safe.

Among the guests in the room that night whom I talked to, no one had an issue with her work as a prosecutor. A lot of them seemed to believe that only people doing dirt had issues with prosecutors. I thought of myself and my friends who have served long terms, knowing that in a way, Harris was talking about Black people’s needing protection from us — from the violence we perpetrated to earn those years in a series of cells.

Harris came up as a prosecutor in the 1990s, when both the political culture and popular culture were developing a story about crime and violence that made incarceration feel like a moral response. Back then, films by Black directors — “New Jack City,” “Menace II Society,” “Boyz n the Hood” — turned Black violence into a genre where murder and crack-dealing were as ever-present as Black fathers were absent. Those were the years when Representative Charlie Rangel, a Democrat, argued that “we should not allow people to distribute this poison without fear that they might be arrested” and “go to jail for the rest of their natural life.” Those were the years when President Clinton signed legislation that ended federal parole for people with three violent crime convictions and encouraged states to essentially eliminate parole; made it more difficult for defendants to challenge their convictions in court; and made it nearly impossible to challenge prison conditions.

Back then, it felt like I was just one of an entire generation of young Black men learning the logic of count time and lockdown. With me were Anthony Winn and Terell Kelly and a dozen others, all lost to prison during those years. Terell was sentenced to 33 years for murdering a man when he was 17 — a neighborhood beef turned deadly. Home from college for two weeks, a 19-year-old Anthony robbed four convenience stores — he’d been carrying a pistol during three. After he was sentenced by four judges, he had a total of 36 years.

Most of us came into those cells with trauma, having witnessed or experienced brutality before committing our own. Prison, a factory of violence and despair, introduced us to more of the same. And though there were organizations working to get rid of the death penalty, end mandatory minimums, bring back parole and even abolish prisons, there were few ways for us to know that they existed. We suffered. And we felt alone. Because of this, sometimes I reduce my friends’ stories to the cruelty of doing time. I forget that Terell and I walked prison yards as teenagers, discussing Malcolm X and searching for mentors in the men around us. I forget that Anthony and I talked about the poetry of Sonia Sanchez the way others praised DMX. He taught me the meaning of the word “patina” and introduced me to the music of Bill Withers. There were Luke and Fats; and Juvie, who could give you the sharpest edge-up in America with just a razor and comb.

When I left prison in 2005, they all had decades left. Then I went to law school and believed I owed it to them to work on their cases and help them get out. I’ve persuaded lawyers to represent friends pro bono. Put together parole packets — basically job applications for freedom: letters of recommendation and support from family and friends; copies of certificates attesting to vocational training; the record of college credits. We always return to the crimes to provide explanation and context. We argue that today each one little resembles the teenager who pulled a gun. And I write a letter — which is less from a lawyer and more from a man remembering what it means to want to go home to his mother. I write, struggling to condense decades of life in prison into a 10-page case for freedom. Then I find my way to the parole board’s office in Richmond, Va., and try to persuade the members to let my friends see a sunrise for the first time.

Juvie and Luke have made parole; Fats, represented by the Innocence Project at the University of Virginia School of Law, was granted a conditional pardon by Virginia’s governor, Ralph Northam. All three are home now, released just as a pandemic would come to threaten the lives of so many others still inside. Now free, they’ve sent me text messages with videos of themselves hugging their mothers for the first time in decades, casting fishing lines from boats drifting along rivers they didn’t expect to see again, enjoying a cold beer that isn’t contraband.

In February, after 25 years, Virginia passed a bill making people incarcerated for at least 20 years for crimes they committed before their 18th birthdays eligible for parole. Men who imagined they would die in prison now may see daylight. Terell will be eligible. These years later, he’s the mentor we searched for, helping to organize, from the inside, community events for children, and he’s spoken publicly about learning to view his crimes through the eyes of his victim’s family. My man Anthony was 19 when he committed his crime. In the last few years, he’s organized poetry readings, book clubs and fatherhood classes. When Gregory Fairchild, a professor at the Darden School of Business at the University of Virginia, began an entrepreneurship program at Dillwyn Correctional Center, Anthony was among the graduates, earning all three of the certificates that it offered. He worked to have me invited as the commencement speaker, and what I remember most is watching him share a meal with his parents for the first time since his arrest. But he must pray that the governor grants him a conditional pardon, as he did for Fats.

I tell myself that my friends are unique, that I wouldn’t fight so hard for just anybody. But maybe there is little particularly distinct about any of us — beyond that we’d served enough time in prison. There was a skinny light-skinned 15-year-old kid who came into prison during the years that we were there. The rumor was that he’d broken into the house of an older woman and sexually assaulted her. We all knew he had three life sentences. Someone stole his shoes. People threatened him. He’d had to break a man’s jaw with a lock in a sock to prove he’d fight if pushed. As a teenager, he was experiencing the worst of prison. And I know that had he been my cellmate, had I known him the way I know my friends, if he reached out to me today, I’d probably be arguing that he should be free.

But I know that on the other end of our prison sentences was always someone weeping. During the middle of Harris’s presidential campaign, a friend referred me to a woman with a story about Senator Harris that she felt I needed to hear. Years ago, this woman’s sister had been missing for days, and the police had done little. Happenstance gave this woman an audience with then-Attorney General Harris. A coordinated multicity search followed. The sister had been murdered; her body was found in a ravine. The woman told me that “Kamala understands the politics of victimization as well as anyone who has been in the system, which is that this kind of case — a 50-year-old Black woman gone missing or found dead — ordinarily does not get any resources put toward it.” They caught the man who murdered her sister, and he was sentenced to 131 years. I think about the man who assaulted my mother, a serial rapist, because his case makes me struggle with questions of violence and vengeance and justice. And I stop thinking about it. I am inconsistent. I want my friends out, but I know there is no one who can convince me that this man shouldn’t spend the rest of his life in prison.

My mother purchased her first single-family home just before I was released from prison. One version of this story is that she purchased the house so that I wouldn’t spend a single night more than necessary in the childhood home I walked away from in handcuffs. A truer account is that by leaving Suitland, my mother meant to burn the place from memory.

I imagined that I had singularly introduced my mother to the pain of the courts. I was wrong. The first time she missed work to attend court proceedings was to witness the prosecution of a kid the same age as I was when I robbed a man. He was probably from Suitland, and he’d attempted to rob my mother at gunpoint. The second time, my mother attended a series of court dates involving me, dressed in her best work clothes to remind the prosecutor and judge and those in the courtroom that the child facing a life sentence had a mother who loved him. The third time, my mother took off days from work to go to court alone and witness the trial of the man who raped her and two other women. A prosecutor’s subpoena forced her to testify, and her solace came from knowing that prison would prevent him from attacking others.

After my mother told me what had happened to her, we didn’t mention it to each other again for more than a decade. But then in 2018, she and I were interviewed on the podcast “Death, Sex & Money.” The host asked my mother about going to court for her son’s trial when he was facing life. “I was raped by gunpoint,” my mother said. “It happened just before he was sentenced. So when I was going to court for Dwayne, I was also going for a court trial for myself.” I hadn’t forgotten what happened, but having my mother say it aloud to a stranger made it far more devastating.

On the last day of the trial of the man who raped her, my mother told me, the judge accepted his guilty plea. She remembers only that he didn’t get enough time. She says her nose began to bleed. When I asked her what she would have wanted to happen to her attacker, she replied, “That I’d taken the deputy’s gun and shot him.”

Harris has studied crime-scene and autopsy photos of the dead. She has confronted men in court who have sexually assaulted their children, sexually assaulted the elderly, scalped their lovers. In her 2009 book, “Smart on Crime,” Harris praised the work of Sunny Schwartz — creator of the Resolve to Stop the Violence Project, the first restorative-justice program in the country to offer services to offenders and victims, which began at a jail in San Francisco. It aims to help inmates who have committed violent crimes by giving them tools to de-escalate confrontations. Harris wrote a bill with a state senator to ensure that children who witness violence can receive mental health treatment. And she argued that safety is a civil right, and that a 60-year sentence for a series of restaurant armed robberies, where some victims were bound or locked in freezers, “should tell anyone considering viciously preying on citizens and businesses that they will be caught, convicted and sent to prison — for a very long time.”

Politicians and the public acknowledge mass incarceration is a problem, but the lengthy prison sentences of men and women incarcerated during the 1990s have largely not been revisited. While the evidence of any prosecutor doing work on this front is slim, as a politician arguing for basic systemic reforms, Harris has noted the need to “unravel the decades-long effort to make sentencing guidelines excessively harsh, to the point of being inhumane”; criticized the bail system; and called for an end to private prisons and criticized the companies that charge absurd rates for phone calls and electronic-monitoring services.

In June, months into the Covid-19 pandemic, and before she was tapped as the vice-presidential nominee, I had the opportunity to interview Harris by phone. A police officer’s knee on the neck of George Floyd, choking the life out of him as he called for help, had been captured on video. Each night, thousands around the world protested. During our conversation, Harris told me that as the only Black woman in the United States Senate “in the midst of the killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery,” countless people had asked for stories about her experiences with racism. Harris said that she was not about to start telling them “about my world for a number of reasons, including you should know about the issue that affects this country as part of the greatest stain on this country.” Exhausted, she no longer answered the questions. I imagined she believes, as Toni Morrison once said, that “the very serious function of racism” is “distraction. It keeps you from doing your work.”

But these days, even in the conversations that I hear my children having, race suffuses so much. I tell Harris that my 12-year-old son, Micah, told his classmates and teachers: “As you all know, my dad went to jail. Shouldn’t the police who killed Floyd go to jail?” My son wanted to know why prison seemed to be reserved for Black people and wondered whose violence demanded a prison cell.

“In the criminal-justice system,” Harris replied, “the irony, and, frankly, the hypocrisy is that whenever we use the words ‘accountability’ and ‘consequence,’ it’s always about the individual who was arrested.” Again, she began to make a case that would be familiar to any progressive about the need to make the system accountable. And while I found myself agreeing, I began to fear that the point was just to find ways to treat officers in the same brutal way that we treat everyone else. I thought about the men I’d represented in parole hearings — and the friends I’d be representing soon. And wondered out loud to Harris: How do we get to their freedom?

“We need to reimagine what public safety looks like,” the senator told me, noting that she would talk about a public health model. “Are we looking at the fact that if you focus on issues like education and preventive things, then you don’t have a system that’s reactive?” The list of those things becomes long: affordable housing, job-skills development, education funding, homeownership. She remembered how during the early 2000s, when she was the San Francisco district attorney and started Back on Track (a re-entry program that sought to reduce future incarceration by building the skills of the men facing drug charges), many people were critical. “ ‘You’re a D.A. You’re supposed to be putting people in jail, not letting them out,’” she said people told her.

It always returns to this for me — who should be in prison, and for how long? I know that American prisons do little to address violence. If anything, they exacerbate it. If my friends walk out of prison changed from the boys who walked in, it will be because they’ve fought with the system — with themselves and sometimes with the men around them — to be different. Most violent crimes go unsolved, and the pain they cause is nearly always unresolved. And those who are convicted — many, maybe all — do far too much time in prison.

And yet, I imagine what I would do if the Maryland Parole Commission contacted my mother, informing her that the man who assaulted her is eligible for parole. I’m certain I’d write a letter explaining how one morning my mother didn’t go to work because she was in a hospital; tell the board that the memory of a gun pointed at her head has never left; explain how when I came home, my mother told me the story. Some violence changes everything.

The thing that makes you suited for a conversation in America might be the very thing that precludes you from having it. Terell, Anthony, Fats, Luke and Juvie have taught me that the best indicator of whether I believe they should be free is our friendship. Learning that a Black man in the city I called home raped my mother taught me that the pain and anger for a family member can be unfathomable. It makes me wonder if parole agencies should contact me at all — if they should ever contact victims and their families.

Perhaps if Harris becomes the vice president we can have a national conversation about our contradictory impulses around crime and punishment. For three decades, as a line prosecutor, a district attorney, an attorney general and now a senator, her work has allowed her to witness many of them. Prosecutors make a convenient target. But if the system is broken, it is because our flaws more than our virtues animate it. Confronting why so many of us believe prisons must exist may force us to admit that we have no adequate response to some violence. Still, I hope that Harris reminds the country that simply acknowledging the problem of mass incarceration does not address it — any more than keeping my friends in prison is a solution to the violence and trauma that landed them there.

In light of Harris being endorsed by Biden and highly likely to be the Democratic Party candidate, I thought I would share this balanced, understanding of both sides, article in regard to Harris and her career as a prosecutor, as I know that will be something dragged out by bad actors and useful idiots (you have a bunch of people stating 'Kamala is a cop', which is completely false, and also factless and misleading statements about 'mass incarceration' under her). I'm not saying she doesn't deserve to be criticised or that there is nothing about her career that can be criticised, but it should at least be representative of the truth and understanding of the complexities of the legal system.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“In line with the dominant values of early industrial society, the exposure to and reinforcement of appropriate behaviour could correct deviant character. In theory, the “mad” would no longer be chained, tortured, and warehoused by society, instead they would be taught how to behave and act appropriately without fear of punishment. In turn, good behaviour would be rewarded with humane care and the potential to re-join the world outside the institution. The stick had been replaced by the carrot; as long as the patient could learn the rules and behaviour of this new society, they had nothing to fear.

As with the prison and workhouse, one of the primary features of moral treatment at the York Retreat was the importance of work in the daily regime of the inmates and, equally, a distain for idleness. Even if the work was of little value in itself, it reinforced a moral imperative in the mind of the deviant. As Foucault (1988a: 247) reflected,

Work comes first in “moral treatment” as practiced at the Retreat. In itself, work possesses a constraining power superior to all forms of physical coercion, in that the regularity of the hours, the requirements of attention, the obligation to produce a result detach the sufferer from a liberty of mind that would be fatal and engage him in a system of responsibilities.

Samuel Tuke was of the opinion that “of all the modes by which patients may be induced to restrain themselves, regular employment is perhaps the most generally efficacious” (cited in Scull 1989: 90). Under such a “treatment” regime, work had a moral value in self-regulating the behaviour of the deviant. This was a new form of moral surveillance in industrial society and one which was as applicable to the prisoner, the poor, and the mad as it was to the factory worker.

It is this moral authority of such management and daily regimes as found in wider capitalist society which psychiatry progressed with the expansion of institutions for the insane throughout Europe and America in the nineteenth century. The key to psychiatrists successfully establishing themselves as the “experts on the mind” was their appropriation of moral treatment as a “scientific” system of care for the management of the insane which—more that coincidentally—conformed to the values of the dominant social order. As Pollard has noted, industrial capitalism demanded “a reform of ‘character’ on the part of every single workman, since the previous character did not fit the new industrial system” (cited in Scull 1989: 91). A new set of competitive norms had to be taught and internalised through the new institutions by disciplinary techniques rather than coercion, and this applied as much to those labelled as “mad” as to the rest of society. Thus, the appearance and success of moral treatment can only be fully understood within the wider social and economic context in which it emerged, a point reinforced by Scull (1989: 92) when he notes,

The insistence on the importance of the internalization of norms, the conception of how this was to be done, and even the nature of the norms that were to be internalized—in all these respects we can now see how the emerging attitude toward the insane paralleled contemporaneous shifts in the treatment of other deviants and of the normal.”]

bruce m.z. cohen, from psychiatric hegemony: a marxist theory of mental illness, 2016

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slate Magazine: Helen Vera: Against Solitary Confinement: State are Finding it's Impractical as well as Immoral

Source:The New Democrat The current use of the process of solitary confinement in U.S. prisons is deplorable. There are no guidelines relating the length of confinement to severity of offense. The process is used at the discretion of onsite officials. This results in wide variations with some cruel and counterproductive results. Indefinite solitary confinement is simply inhumane and can only…

View On WordPress

#2014#America#American Corrections System#American Prison System#Cruel and Unusual Punishment#Extreme Solitary Confinement#Helen Vera#Solitary Confinement#United States

0 notes

Note

in your country do they have higher police order to arrest any person who threatens the president or people like this singer of your country? she is crazy and not arrested yet for saying this???

they said this about your president before donald had attemps on his life

I need to correct you on something. This is not a woman. This is a biological man who is a Transwoman. They use the stage name "Ethel Cain" but their government name is Hayden Silas Anhedonia. They use their government name in real life still to this day, so this isn't any "dead naming" bullshit.

I've spoken about Ethel Cain on my page before. Every time they have something new to release, they say something controversial with zero consequences in return. Their alleged hatred for biological women is disturbing to read as well as their alleged hatred for Lana Del Rey - who they sonically ripped off of from time to time.

The "assassinations" IG story was posted about a week before someone tried to take out Trump at one of his rally's. Trump walked away with his life while one audience member was killed. Ethel didn't get arrested by the FBI (our "higher" police) or even remotely in trouble for that post because she is a Transwoman. Transwomen in the United States, at the moment, are treated for the most part as deities. Untouchable. Coming January 20th, that shit is going to end. Trump is coming back home.

I want to see Ethel pull those type of threats online with Trump in office. The FBI will be on their front door in less than 5 mins, hauling Ethel's ass into a male federal prison.

We have something in America called Freedom Of Speech and Freedom Of The Press.

You can say whatever the hell you want without repercussions unless you threaten someone's life or you slander or defame a person without explicitly stating it's your opinion or explaining that what you're saying is alleged. Then you can be sued for defamation of character or slander. Other then that - you're free to say what you want. However, you can't do that in China, Russia, any Arab Nations or even the UK. You can get arrested for saying the wrong thing in those countries. That's the beauty of The United States.

Ethel's newest post about CEO assassinations is as equally disgusting as when they called for Joe Biden's assassination. You just don't say shit like this online or anywhere. The FBI should have arrested them then as they should arrest them now.

In my opinion, Ethel is going on social media right now inciting violence against CEO's. That is illegal. So far, once again - no consequences. They have 7 more days to get away with saying horrible shit like this without getting arrested.

I'm glad to read comments from people who find Ethel Cain gross for saying such things. It is gross. It shows what a demonic type of person you have to be to say things like this out loud. All for what? Publicity for your new album? For shits and giggles?

I've also been a victim of Health Insurance bureaucracy bullshit. I've had to wait weeks for procedures I needed. I had to wait for some asshole in an office to send or approve a doctor's pre-authorization, and if it's up to them, they approve it or deny it. Despite those headaches, I would never wish any harm to any CEO of a Health Care company.

I don't know what is wrong with this generation but ya'll are fucked up and disgusting. Applauding the death of a man who was murdered on broad daylight is barbaric.

Edit: 1/18 - Fox News rips "Ethel Cain" apart and I love every minute of it.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prison-tech is a scam - and a harbinger of your future

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/14/minnesota-nice/#shitty-technology-adoption-curve

Here's how the shitty technology adoption curve works: when you want to roll out a new, abusive technology, look for a group of vulnerable people whose complaints are roundly ignored and subject them to your bad idea. Sand the rough edges off on their bodies and lives. Normalize the technological abuse you seek to inflict.

Next: work your way up the privilege gradient. Maybe you start with prisoners, then work your way up to asylum seekers, parolees and mental patients. Then try it on kids and gig workers. Now, college students and blue collar workers. Climb that curve, bit by bit, until you've reached its apex and everyone is living with your shitty technology:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/24/gwb-rumsfeld-monsters/#bossware

Prisoners, asylum seekers, drug addicts and other marginalized people are the involuntary early adopters of every form of disciplinary technology. They are the leading indicators of the ways that technology will be ruining your life in the future. They are the harbingers of all our technological doom.

Which brings me to Minnesota.