#post modern moral cowardice

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Esto

#this#esto#feeling good about yourself is not the same thing as doing good#regressive mentalities#intellectual dishonesty#post modern moral cowardice#secular ayatollahs#giving in to sentimentality#bullshit unlivable ideologies#bullshit religion#self expression with no self examination#denying reality by screaming at it#punkass parents#reaping what we sow#society#learn how to be good ancestors#social score settling narratives#identity politics#Marie Antoinettism#conservative#peer pressure is a bitch#luxury beliefs#terminally online western adolescent bubble pov#bullshit

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Post-Futurist Fossils of LITCHI HIKARI CLUB In a somewhat recent research tangent, while considering the possible “genealogy” of the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s themes and aesthetics, I made an interesting personal discovery regarding Litchi Hikari Club. Specifically some distinct thematic parallels that the play shares with the Italian futurist movement, less in relation to the art of the movement itself, but rather the ideologies of the movement’s controversial founder, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and his relation to the Italian fascist party. This is all of course in the context of understanding Litchi as a transgressive/dystopian horror story. This is less of an absolute statement than it is a sort of open train of thought, so take things with a fair grain of salt. This is more or less just my own personal analysis of all the materials I could gather of the original play. Beyond inspecting the play as a possible allegory for futurism, there's also just a lot of general analysis of the play in relation to Ameya's overall body of work, both with the Tokyo Grand Guignol and also as a performance artist. I rarely put a 'keep reading' tag on these things since I'm an openly shameless product of the early days of blogging, but this one's a doozy (both in the information but also just the gargantuan length). Hopefully others will find it just as interesting. The full essay is below...

The futurist movement itself was nothing short of an oddity. In their time, the futurists were pioneers of avant-garde modernist aesthetics, with their works ranging from deconstructive paintings to reality-bending sculptures and even early pathways to noise music with the creation of the non-conventional Intonarumori instruments of Luigi Russolo. Russolo’s own futurist-adjacent manifesto, The Art of Noises, would go on to influence such artists as John Cage, Pierre Henry, Einstürzende Neubauten and the openly left-wing industrial collective Test Department. When visiting the MOMA in New York City as a child, I was fascinated by Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, a sculpture that appeared to be a spacetime malformation of the human figure encapsulated in a continual state of forward motion while in total stillness. Despite this, the futurists were also a social movement of warmongering misogynists, with their own founding manifesto by Marinetti describing the bloodshed and cruelty of war as being “… the only cure for the world”. Their manifesto would also feature quotes such as “We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice”. They would originally pin anarchism as being their ideological ground in the manifesto, but shortly thereafter Marinetti would pick up an interest in fascism along with the politics of Benito Mussolini, going on to be a coauthor for the Italian fascist manifesto alongside the futurist manifesto. In consideration of how throughout most of World War II, modernist and post-modern works were considered “degenerate” forms of art in contrast with traditionalism, a whole avant-garde movement founded from fascist ideals is paradoxical. But for a period of time, that parallel wasn’t only in existence, but backed by Mussolini himself with there being a brief effort by Marinetti to make futurism the official aesthetic of fascist Italy. One of the draws of futurism for Marinetti was an underlying sense of violence and extremity. According to Marinetti, his initial inspiration for the movement was the sensations he felt in the aftermath of a car accident where he drove into a ditch after nearly running over a band of tricyclists. He conceived his works to be acts of social disruption, intending to put people in states of unrest to cause riots and similar bouts of violence. “Art, in fact, can be nothing but violence, cruelty, and injustice”. He sought to destroy history to pave the way for a rapid acceleration to futuristic technological revelation.

“As shown in Edogawa Rampo’s Boy Detectives Club, young men like to hide from a world of girls and adulthood to form their own secret societies.” - June Vol. 27 In Litchi Hikari Club, a group of middle school-aged boys are faced with a crisis on the brink of puberty. At the twilight of their childhoods, they form a secret society known as the Hikari Club (or Light Club), a collective that’s devoted to the active preservation of their shared youth and virginity. The boys naively mimic an authoritarian organization and its hierarchy as they seek a means to preserve their boyhood, which they see as being idyllic in contrast to adulthood, a dreary state of existence that they call old and tired in the Usamaru Furuya manga version of the story. Similarly, in the Litchi Hikari Club-inspired short manga Moon Age 15: Damnation, the boys go on to liken their hideout with the paradisiacal garden of Eden. In said story, Zera would directly name the poem Paradise Lost in reference to the discovery of their hideout by adults (arriving in the form of ground surveyors) and the wide-eyed daughter of a land broker, with their contact to the virgin industrialized land being an ideological tainting of the sacred lair. In their mission, they seek refuge in technological inhumanity by having their penises replaced with mechanized iron penises, symbolic devices of power and violence that can only procreate with other items of technology. Working in absolute secrecy, they collectively manufacture a robot known as Lychee. The purpose of Lychee, previously only known to Zera, isn’t revealed to the other club members until its completion. It’s when they unveil their “cute” robot in a scene that parallels the 1920 German expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari that Zera tells the other members of Lychee’s purpose as a machine that would kidnap women for them. The robot's efforts are assisted by the girl capturing device, a strange rice cooker-shaped mask that’s laced with a sleeping drug. When questioned about the fuel source for the robot, Zera explains how it will run off the clean fuel of lychee fruits rather than an unsavory yet plentiful substance like electricity or gasoline as a means to further match the robot’s perceived beauty.

While the club share a general disdain for adulthood, they hold a special hatred to girls and women. Going off the dogmatic repulsion to sexuality that Kyusaku Shimada shows as the teacher in the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s prior play, Mercuro (1984), it could be assumed that the Hikari Club hold a similar dogmatic viewpoint about the vices of sex. In this context, it’s likely that they would’ve perceived women as being parasitic by nature as spreaders of the “old” and “tired” adult human condition through pubescent fixation and procreation. Sexual thoughts are inherent to aging for most people, given the process of discovering and exploring your identity throughout puberty. It’s that exact pubescent experience the club seek to eradicate. Further insight is given to the Hikari Club’s dystopian psyche through their open allusions to nazi ideology. While Zera travels out to gather lychees from a tree he planted, the club get a special visit from a depraved elderly showman known as the Marquis De Maruo, performed by none other than Suehiro Maruo himself in the 1985 Christmas performance. Despite the club’s disposition to adults, they hold an exception for the Marquis for his old-timey showmanship and open pandering to the children’s whims. He always comes with autopsy films to show the young boys, and as they watch the gory videos he hands out candies that he describes as being a personal favorite of the late Adolf Hitler. He was said to also be the one to convince the boys to name their robot after the lychee fruit. It isn’t until Zera returns that the Marquis is removed from the hideout on Zera’s orders. Just before his exiling, he foretells to Zera the prophecy of the black star as both a promise and a warning to the aspiring dictator. It should be noted that there is a fascist occult symbol known as the black sun.

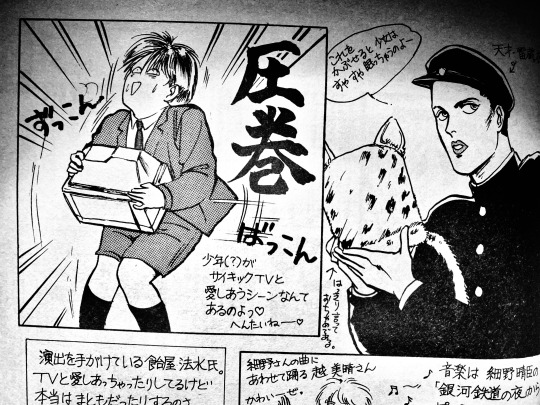

Suehiro Maruo as the Marquis De Maruo. On the right side is a caricature of Maruo as drawn by a contributor to June magazine, excerpted from an editorial cartoon in June Vol. 27 covering Litchi's 1985 Christmas performance. In addition, the Marquis’ role alongside Jaibo’s appearances in the play (which I’ll get to later) show distinct parallels with the presence of the hobo in the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s first play, Mercuro. In Mercuro’s case, the hobo (performed by Norimizu Ameya, who would go on to also act as Jaibo) visits the classroom in secrecy to lecture the students his depraved ideologies. Whilst the hobo in Mercuro was a figure of perversion that existed in contrast to the teacher’s paranoid conservatism, in Litchi both Jaibo and the Marquis are enablers of the club’s fascistic leanings, with the Marquis being a promoter whereas Jaibo is a direct representation of the underlining perversions of fascist violence. Though completely omitted from the Furuya manga, the element of the autopsy films shines a unique light on Zera’s death at the end of the story. In both the play and the manga, Zera is gutted alive by Lychee when the robot undergoes a meltdown after being forced to drown Kanon (Marin in the original play) in a coffin lined with roses. In the manga, Zera appears deeply unsettled when realizing his intestines resemble the internals of an adult. It’s unknown if this aspect is present in the theater version, as the full script remains unreleased to this day. It would fit however knowing not just the club’s repulsion to adulthood, but also how they retreat to technological modification to eradicate the human aspects they associate with adulthood. What is described of Zera’s death in the theater version has its own disquieting qualities as, from what’s mentioned, when confronted with his own mortality he appears to regress to a state of childlike delirium, a demeanor that’s drastically different from his usual calm and orderly presentation. Upon seeing his intestines, one of the responses he is able to muster is “I’m in trouble”. He says this as he questions whether or not he can fit his organs back inside the cavity before eventually telling himself that he’s just tired, that he “need(s) to sleep for a while”.

While never directly stated, it’s heavily implied that the club’s ideologies and technological fetishism ultimately root back to Jaibo, an ambiguously European transfer student who secretly manipulates the club’s actions from behind the scenes. Referred to by Hiroyuki Tsunekawa (Zera’s actor) as the “true dark emperor” of the Hikari Club, he was said to haunt the stage from the sides, closely inspecting the Hikari Club’s activities while keeping a distance. The iron phallus was first introduced by Jaibo through a monologue where he reveals how he fixed one to his own person, carefully describing its inner mechanisms and functionality before demonstrating its inhuman reproductive qualities by using the phallus to have sex with a TV. A television that he affectionately refers to as Psychic TV Chan, in reference to the post-industrial band fronted by Genesis P’Orridge. In the same scene, he promises the other members that they would all eventually get their own iron penises just like his own. In a subsequent scene, he reveals the iron phallus’ use as a weapon when, arriving to the club’s base with a chained-up female schoolteacher who accidentally discovered the sanctuary, he uses the device to brutally kill the teacher through a mocking simulation of sexual intercourse. Just before raping her, he likens her to a landrace, bred for the sole purpose of reproducing and being processed into meat for consumption. He menacingly tells her that he will make her as “cut and dry” as her role in society before carrying out her execution. While there was some confusion on whether or not the iron phallus was a machine or solely a chastity device, it was found in bits of dialogue that the iron phallus at least shares the qualities of a pump with a described set of rubber hinges. The teacher’s death gruesomely reflects the death of Kei Fujiwara’s character in the later film Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), with the iron phallus mangling her insides as blood splatters across the stage. While the club treats adult sexuality as a plague, they manage to find through the iron phallus a way to convert their own states of chastity into a form of violence, stripping all humanity away from the penis and rendering it to a weapon of absolute power through desolate mechanized cruelty.

JAIBO: “Length, 250 mm, with a weight of 2.4 kilograms. Arm diameter, 30mm. Cylindrical thrust, 170mm… With pins, plates and rods of die-cast alloy. And hinges of rubber… the rest is pure iron. It is the iron phallus.” - June Vol. 27 In the same interview, Tsunekawa would go on to recall how the members of the Hikari Club were effectively Jaibo’s guinea pigs. In both the play and the manga, an after-school night of the long knives ensues with the slow collapse of the Hikari Club as Jaibo influences the exiling of certain club members, with Zera left ignorant to the social engineering as a mere extension of Jaibo’s elaborate puppeteering. Left embittered by a chess match where he lost to Zera, Tamiya is easily tricked by Jaibo into burning the lychee field as a way to get vengeance. Upon being caught, Tamiya is castrated of his iron phallus, resulting in his exiling from the club as a traitor while also being mockingly likened to a woman in the process. In another scene, it’s recalled that Jaibo and Zera exchange a conversation about the Hikari Club’s loyalty to Zera as they observe the outside world through their periscopes. By all contemporary recollections, Jaibo was the club’s puppet master. He would’ve been the likely source of the club’s ideologies, the underlining hatred to women and fixation on technological violence, replacing mankind with a race of humanoid weapons. Zera would be a shell without his influence. The presence of futurism could arguably even be rounded down to Lychee’s presence in the story. Beyond his theoretic work, Marinetti was also a playwright. He would be most well known for his futurist drama La donna è mobile, a story riddled with similarly perverse renditions of sexual violence. The play notably featured the presence of humanoid automatons a full decade before the term “robot” would be coined by Czechoslovakian author Karel Čapek in the play R.U.R., with the French version of Marinetti’s script referring to the machines as “puppets” for their visual similarity to humans.

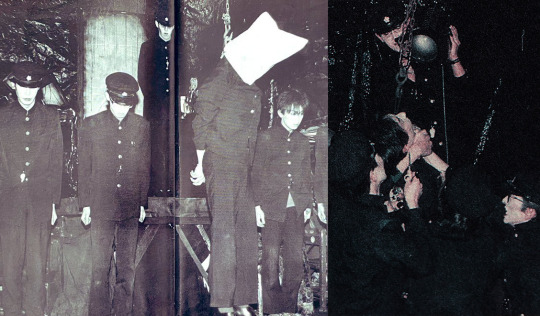

All of this plays out over a soundscape that’s dominated by unnatural electronic frequencies and synthesized percussion. The sound design was arguably one of the most important aspects of Ameya’s plays, with Ameya at one point describing the Tokyo Grand Guignol productions as being an ensemble of his favorite sounds. The setting further compliments the atmosphere, made to resemble the internal of a junkyard or factory warehouse where heaps of technical jump decorate the stage around the monochrome cabinet that would eventually birth Lychee. Some of the featured artists in the play’s first act include Test Department, The Residents, 23 Skidoo and Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft. The play’s opening, which depicts the capturing and subsequent torture of a student named Toba through a so-called “baptism of light”, is underscored by the S.P.K. song Culturcide, a grim primordial industrial dirge that paints the image of a dystopia where the genocide of ethnic cultures is likened to the infection of human cells by parasitic pathogens. Instead of being hung with a noose, Toba is suspended by a meathook, left as a decoration amidst the heaps of mechanized excrement. He would eventually be joined by the lifeless bodies of various women the Hikari Club abduct as they’re steadily gathered in a small box at the back of the stage. “Membrane torn apart, scavenging with the nomads. Requiem for the vestiges. Dissected, reproduced. The nucleus is infected with hybrid’s seed. Needles soak up, the weak must destroy. Cells cry out, cells scream out. Culturcide! Culturcide! Culturcide! Culturcide!” - Culturcide (from S.P.K.'s Dekompositiones EP)

“We are now entering an era which history will come to call ANOTHER DARK AGE. But, in kontrast to the original Dark Age, defined by a lack of information, we suffer from an excess of information, which has been reduced to the repetition of media-generated signs. Through this specialization, it is no longer possible for an individual to attain a total view of society. Edukation is struktured to the performance of a limited number of funktions rather than for kreativity.” “Kommunications systems are designed for the passive entertainment of the konsumer rather than the aktive stimulation of the user’s imagination. Through the spread of the western media, all kultures come to stimulate one another. By the end of the millennium, this biological infektion will have penetrated the heart of the most isolated traditions - a total CULTURCIDE.” “Yet in every era, a small number of visionaries rise above the general malaise. Those who will succeed, will resist the pressure to become kommercialized “images”, demanding identifikation and imitation. They will uphold their principles in the face of impossible odds. By remaining anonymous, they will be free to develop their imagination with maximum diversity. For this is the TWILIGHT OF THE IDOLS, - the end of the proliferation of the ikons and the advent of a new symbolism.” - From the back cover of S.P.K.’s Dekompositiones EP (released under the moniker SepPuKu) Over the course of the play, the story undergoes a drastic tonal shift as the focus moves from the Hikari Club’s hierarchical order and internal conflicts to the relationship between Lychee and Marin. Marin (performed by synthpop musician Miharu Koshi) was the first girl the Hikari Club successfully kidnap through Lychee after implementing the phrase “I am a human” in Lychee’s coding so it can understand the concept of human beauty. This small implementation causes a full unraveling in Lychee’s personality as it quickly forms a close bond with Marin, convinced that it is also a human like Marin. The soundscape changes alongside the overarching atmosphere, going from cold industrial drones and percussive electronica to ambient tracks. Some of the major scenes play out over moving piano-focused pieces and music box tunes from Haruomi Hosono’s soundtrack for Night on the Galactic Railroad. Originally created a weapon like the iron phalluses and the girl capturing device, Lychee is eventually defined in how he transcends from being a weapon to a conscious being with feelings. In this context, the play can be read as a juxtaposition of human emotion against inhuman futurist brutality.

This split was likely the product of the radically different creative ideologies of Norimizu Ameya (the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s founder and lead director) and pseudonymous author K. Tagane (the playwright for the group from Mercuro to Litchi). Ameya had come into the group with radical intentions, holding Artaudesque aspirations to transgress the literary limits of modern theater to achieve something deeply subconscious. Meanwhile, Tagane was a romantic who was known for their poetic and lyrical screenplays. Ameya purportedly sought out Tagane’s screenplays specifically to find a literary base he would “destroy” in his direction, deconstructing the poeticisms in his own unique style. He describes it briefly in an interview regarding the stage directions of Mercuro, stating how he took elaborate descriptions of a lingering moon and ultimately deconstructed them to the moon solely being an illusion set by a screen projector, mapping out the exact dimensions of the projection to being a 3-meter photograph of the moon rather than a “fantastic moon”. It’s believed by some that the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s formation and ultimately short run were the product of a miraculous balance between Ameya and Tagane’s ideologies. It’s possible that Litchi could’ve been a last straw between the two artists. After Litchi, Tagane left the group, with Ameya having to write the troupe’s final screenplay on his own. LYCHEE: “Marin is always sleeping… all she does is sleep. She doesn’t eat anything. Why does Marin sleep all day?” MARIN: “When you’re asleep, all the sadness of the world passes over you.”

"The second half of Litchi was predominantly driven by the sounds of Ryuichi Sakamoto and Haruomi Hosono. During a scene that featured a piece from the Galactic Railroad soundtrack, Miharu Koshi sang to Kyusaku Shimada while dancing like a clockwork doll to the sounds of a twisting music box. The scene lasted for a while and was very romantic, the interactions between Lychee and Marin were all very sweet and cute. The second act of Litchi was all a product of Tagane’s making. By the time of the following play, Walpurgis, I was told by a staff member that Ameya had written the screenplay by himself because Tagane had left.” “… While the first half was filled with repeated mantras and the unfolding aesthetics of an aspiring militia, the second half was immersed in the world of shoujo manga. It did appear that through the intermission, much of the junk and rubble around the podium was sorted out.” “… The Tokyo Grand Guignol’s plays were always defined by a strong nocturnal atmosphere. But in Litchi’s second half, it wasn’t a dark night, but a brightly lit one under the moonlight and plentiful stars in the sky shining through an invisible skylight. Marin doesn’t forgive Lychee immediately for his actions, responding to him harshly in a way that would confuse him and make him sulk. It came across as a somewhat bitter reimagining of a French comedy like Louis Malle’s Zazie dans le Métro or Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amélie, it was different that way in how it wasn’t only Maruo’s inferno.” - From a Twitter thread by user Shoru Toji regarding the 1986 rerun of Litchi Hikari Club Some questionable qualities do exist in the relationship between Lychee and Marin. What should be a peaceful retreat from the dystopian corruption still has a sinister undertone in the disparities between Lychee’s cold masculine features in contrast with Marin’s childlike girly innocence. It doesn’t help that Zazie dans le Métro (one of the mentioned films in the recollection) was directed by Louis Malle, who while known for such films as My Dinner With Andre and Black Moon was also responsible for the infamously discomforting Pretty Baby. Then again, Litchi was the product of a confrontational transgressive subculture, so the sinister undertones could be intentional. Keep in mind the contents of Suehiro Maruo’s prolific adaption of Shōjo Tsubaki and how it unflinchingly depicts abuse and manipulation through the eyes of a confused child. It could be possible that Lychee himself was intended to be childlike in its mannerisms. Throughout the existing descriptions, Lychee was shown as speaking in fragmented sentences while struggling to understand basic concepts. Zera was mentioned to also use certain phrases like “cute” when referring to the robot when it was unveiled. And it’s through Marin that Lychee learns morality like a child. The robot’s masculinity could be passed off as the cast all being adults. Hiroyuki Tsunekawa for instance shows distinctly sculpted features from certain angles when performing Zera.

In his aspirations to become a human, Lychee eventually “dies” like a human. With the burning of Zera’s lychee tree, the robot is left with a finite limit on its remaining energy before it totally loses consciousness. After his rampage, Lychee attempts to reunite with Marin, but he runs out of fuel. Before what should be a moment of resolution, things are cut short as the stage goes black, eventually illuminated to show an unpowered Lychee cradling Marin’s corpse in his arms. Zera reemerges to observe the remnants of Lychee and Marin. He speaks of how Lychee will crumble into nothingness alongside Marin for foolishly giving into human emotion, further implying the club’s views on humanity. After this, recollections of the play’s final lines differentiate somewhat. It was said that in the original Christmas performance, Zera calls out to Jaibo, posing the corpses of Lychee and Marin as being his seasonal gifts to Jaibo. Whereas in most popular recollections, it’s described that after his monologue, Zera shouts “Wohlan! Beginnen!” (German for “Now! Begin!”) before prompting the decorations across the stage to collapse, revealing a set of stepladders from behind that the remaining previously deceased club members stand, all drenched in blood with spotlights illuminating their faces from below. ZERA: “And with that, our tale of a foolish romance between woman and machine reaches its conclusion. It ends before me as I stand here, watching. Lychee, the machine, will rust away into dust. And Marin, a young girl, will rot away leaving behind only her bones, which too will crumble…”

Multiple readings can be deciphered from this conclusion. The most established theory is in relation to the Hikari Club’s aspirations for eternal youth, with the members technically achieving their goal through the stagnation of death. They will remain eternal children since they died as children, unable to ever grow into adulthood. In the context of futurism and mechanized fascism however, it could be read as a bitter observation of a lasting dictatorship. With how the Hikari Club members had rendered themselves less human than their own robot, they survive death to continue their work, seeking to one day eradicate humanity in favor of a race of sentient childlike weapons. “To admire an old picture is to pour our sensibility into a funeral urn instead of casting it forward with violent spurts of creation and action. Do you want to waste the best part of your strength in a useless admiration of the past, from which you will emerge exhausted, diminished, trampled on?” “… For the dying, for invalids and for prisoners it may be all right. It is, perhaps, some sort of balm for their wounds, the admirable past, at a moment when the future is denied them. But we will have none of it, we, the young, strong and living Futurists! Let the good incendiaries with charred fingers come! Here they are! Heap up the fire to the shelves of the libraries! Divert the canals to flood the cellars of the museums! Let the glorious canvases swim ashore! Take the picks and hammers! Undermine the foundation of venerable towns! The oldest among us are not yet thirty years old: we have therefore at least ten years to accomplish our task. When we are forty let younger and stronger men than we throw us in the waste paper basket like useless manuscripts! They will come against us from afar, leaping on the light cadence of their first poems, clutching the air with their predatory fingers and sniffing at the gates of the academies the good scent of our decaying spirits, already promised to the catacombs of the libraries.” - from the 1909 Futurist Manifesto by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

I forgot what exactly first caused the parallel to cross my mind. I do recall it being reignited when having a closer look over the poster and flyer for Litchi’s Christmas performance in December 1985. The flyer in particular is really a wonderful thing to look at. Predominantly featuring an art spread by Suehiro Maruo, a suited man with Kyusaku Shimada’s likeness is shown caressing a girl in front of a modernist cityscape with spotlights shining up to a night sky. Other suited men in goggles fly in the air with Da Vinci-reminiscent flying apparatuses between the beams of the metropolis’ spotlights. A student in full gakuran uniform flings himself into the scene from the far left side of the image with a dagger in hand, and a larger hand comes from the viewer’s perspective holding a partially peeled lychee fruit. While not based on any direct scene from the play, it perfectly instills the play’s atmosphere with an air of antiquated modernity, like the numerous illustrations of the early 1900s that show aspirational visions of what a futuristic cityscape might resemble. The bizarre neo-Victorian fashions of the future and its post-modernist formalities. The term futurism came to mind somewhat naively from this train of thought. It was a movement I recalled hearing about, but my memory of it was hazy. It wasn’t until I went in for a basic refresher that I felt the figurative lightbulb go off in my head. That was when the pieces started to come together, but then also strain apart from each other into tangents. Granted, many of these parallels could be read as coincidental. Many of them can even be passed off the play being a work of proto-cyberpunk, knowing how Tetsuo: The Iron Man would subsequently explore similar themes of cybernetics and human sexuality. It should still be noted however that in contrast with many of the Japanese cyberpunk films, Litchi was explicit in its connotations between technological inhumanity and fascism, with the machinery itself being the iconography of a dictatorship rather than a product of it. In addition, with Tetsuo the film has strong gay overtones, with the technology being an extension of the sexual tensions between the salaryman and the metal fetishist. For a period of time, efforts were made to make futurism the official aesthetic of fascist Italy, and modern fascism as we know it is in the same family tree of Italian philosophy as futurism. The Hikari Club are explicit in drawing from German aesthetics rather than Italian however, speaking in intermittent German and predominantly using German technology. The spotlight that they used when torturing Toba in the first act, for example, was a Hustadt Leuchten branded spotlight. And if that isn’t a German name I don’t know what is. It was also said that Jaibo’s outfit in the play was modeled after German school uniforms. Though then again, the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s works were a bit of a cultural slurry. Jaibo’s name for example is Spanish (derived from Luis Buñuel’s Los Olvidados), while the character is implied to be German.

Similar to the cited origins of futurism, Ameya stated in a 2019 tweet regarding the June 9th, 1985 abridged Mercuro performance on Tokumitsu Kazuo’s TV Forum that in the following August of that year, an airplane accident occurred that led to the conception of Litchi’s screenplay. The exact nature of the accident was never specified, but the affiliates he was communicating with all appeared to be familiar with it and expressed concern when it was brought up. This was however one of an assortment of influences that were cited behind Litchi’s production, with the two more established theories regarding the then-contemporary mystique around lychee fruit in Chinese cuisine along with the play being a loose adaption of Kazuo Umezu’s My Name is Shingo. For what it’s worth, the themes of Litchi, along with the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s other works, were closely tied with certain concepts that Ameya personally cultivated throughout his career. A frequent recurring topic Ameya would bring up in relation to his works was the nature of the human body in relation to foreign matter, need it be biological or unnatural. With Mercuro the students taught by Shimada are made into so-called Mercuroids by having their blood supplies replaced with mercurochrome, a substance that is referred to as the “antithesis of blood” by Shimada while in character. In an interview for the book About Artaud?, Ameya cites an interest in Osamu Tezuka’s manga in how certain stories of Tezuka’s paralleled Ameya’s observations of the body. He directly names Dororo and Black Jack, observing how both Hyakkimaru and Black Jack reconstructed their bodies from pieces of other people, going on to bluntly describe Pinoko as a “mass of organs covered in plastic skin”.

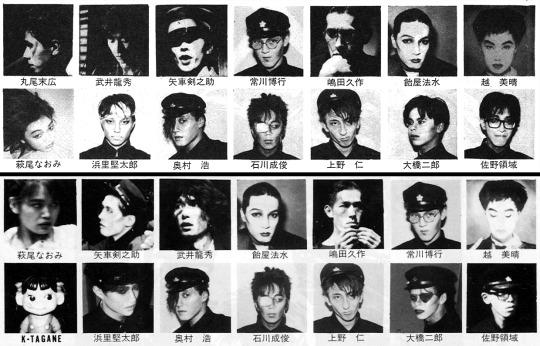

A section from June Vol. 27 highlighting some of the more established performers from Litchi's 1985 Christmas performance. The actors from left to right are Norimizu Ameya as Jaibo, Naomi Hagio as the female school teacher (best known in cult circles for her role as Kazuyo in the 1986 horror film Entrails of a Virgin), Suehiro Maruo out of costume and Miharu Koshi as Marin. During his temporary retirement from theater, Ameya would take up performance art, with some of his performances revolving around acts with his own blood. While my memories of these works are a bit hazy, I remember one action he performed that involved a blood transfusion, with the focus being on the experience of having another person’s blood coursing through your veins. While I didn't have much luck relocating this piece (probably from it not being covered in English), I did find on the Japan Foundation’s page for performing arts an interview where Ameya discusses being in a band with Shimada where Ameya had blood drawn from his body while he played drums. He would also describe an art exhibition where he displayed samples of the blood of a person infected with HIV. “After 1990 he left the field of theatre and began to engage himself with visual arts - still proceeding to work on his major topic - the human body - taking up themes like blood transfusion, artificial fertilization, infectious diseases, selective breeding, chemical food, and sex discrimination, creating works as a member of the collaboration unit Technocrat.” - Performing Arts Network Japan (The Japan Foundation) There are still an assortment of open questions I’m left with in regards to the contents of the original Litchi play. One of the most glaring ones is Niko’s eye. In consideration of Ameya’s interest in the body, the detail would fit perfectly with his ideologies. A club member who, to show his absolute loyalty to the Hikari Club, has his own eyeball procedurally gouged out to be made a part of the Lychee robot. Despite this perfect alignment, none of the contemporary recollections mention this element. While Niko does have an eyepatch in certain production photos, it never seems to come up as a plot point. He isn’t the only one to bear an eyepatch either, with Jacob also being shown with an eyepatch in flyers. More questions range from Jaibo’s motives in causing the dissolution of the Hikari Club to the true nature of Zera’s affiliation to Jaibo. While Tsunekawa has stood his ground in the relationship between Zera and Jaibo being totally sexless, in the cited volume of June the editor playfully refers to Jaibo as being Zera’s “best friend” in quotes.

A side-by-side comparison of the cast listings on the back of the flyers for the December 1985 performance of Litchi Hikari Club alongside its 1986 rerun. The 1985 run's lineup is at the top while the 1986 run is at the bottom. Much speculation is naturally involved when looking into the original Litchi Hikari Club since it is in essence a cultural phantom. There’s a reason I used the term genealogy in relation to my research of the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s works. It is an artistic enigma as while its presence lingers in subculture, the original works are now practically unattainable due to the inherent nature of theater. As Ameya himself would acknowledge in another interview, theater is an immediate medium that can only be perceived in its truest form for a very short span of time before eventually disintegrating. So with the Tokyo Grand Guignol’s plays, you are left to scour through the scattered remnants and contemporary recollections alongside the figurative creative descendants of the plays. You analyze the statements of both the original participants and the people they openly dismiss, as even those people were original audience members before reinterpreting the plays to their own unique visions. Despite the apparent differences, I still feel that Furuya’s manga gives a unique perspective to the story when viewed under dissection. That is if you want to see it in strict relation to the play. Outside that, I feel it firmly stands on its own merits. I like the manga no matter what Tsunekawa says, that’s what I’m trying to say. Ameya approved it anyway. It took me a full day to write all this out, and like the first time I went down this train of thought, I’m pooped. During that first excursion, after excitedly spiraling through these potential connections, I noticed in passing mention something about Marinetti’s cooking. You see, later in his life Marinetti aimed to apply futurism not just to art and theater, but cuisine also. As an Italian, Marinetti openly despised pasta, seeing it as being an edible slog that weighs down the spirits of the Italian people. Just further evidence that I would never get along with the man, no matter my liking of the Boccioni sculpture I saw at MOMA all those years ago. Well, outside of him being a fascist and all obviously. I like pasta. Either way, he was on a mission to conceive all-new all-Italian cuisines that would match the vision he had of a new fascist Italy. Nothing could prepare me though for when I saw an image of what would best be described as a towering cock and ball torture meat totem. It is exactly as it sounds, a big phallic tower of cooked meat with a set of gigantic dough-covered balls of chicken flesh on the front and back where you have to stick needles through the thing to hold it together. Words cannot express just how big it is. The thing was damn well near falling apart from how unnatural its shape was, and you’re expected to eat it while it has honey pouring from the tip of the tower. I genuinely winced watching its assembly, I instinctively crossed my legs somewhat when it was pierced by wooden sticks and then cut into sections to reveal the plant-stuffed interiors. As a person with no interest whatsoever in cooking shows, I was on the edge of my seat watching a PBS-funded webisode of someone preparing futurist dishes. Seek it out for yourself, it’s an excessively batshit culinary freakshow. That is more than enough talk about penises for the rest of the week. I’m going to spend the next few days looking at artistic yet selectively vaginal flowers to balance things out, equal opportunity symbology.

206 notes

·

View notes

Note

I believe it was regarding futurism? I could be mistaken, though - Gort Inspo anon

Italian Futurism!

So going to preface this by saying I am very much a layman when it comes to art history this is just my own little interest. Gonna put a cool sculpture image for attention (and also like. Yeah) and then go under the cut:

So the manifesto for futurism was the following tenets (bolded for emphasis of particular themes by me:)

Manifesto of Futurism

1. We intend to glorify the love of danger, the custom of energy, the strength of daring.

2. The essential elements of our poetry will be courage, audacity, and revolt.

3. Literature having up to now glorified has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggressive action, feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the punch, and the slap.

4. We declare that the splendour of the world has been enriched with a new form of beauty, the beauty of speed. A race-automobile adorned with great pipes like serpents with explosive breath… a race-automobile which seems to rush over exploding power is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

5. We will sing the praise of man holding the fly-wheel of which the ideal steering-post traverses the earth impelled itself around the circuit of its own orbit.

6. The poet must spend himself with warmth brilliancy and prodigality to augment the fervor of the primordial elements.

7. There is no more beauty except in struggle. No master-piece without the stamp of aggressiveness. Poetry should be a violent assault against unknown forces to summon them to lie down at the feet of man.

8. We are on the extreme promontory of ages! Why look back since we must break down the mysterious doors of Impossibility? Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the Absolute for we have already created the omnipresent eternal speed.

9. We will glorify war – the only true hygiene of the world – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of anarchists, the beautiful Ideas which kill, and the scorn of women.

10. We will destroy museums, libraries and fight against moralism, feminism and all utilitarian cowardice.

11. We will sing of great message agitated by work pleasure or revolt: we will sing of the multicolored and polyphonic surf of revolutions in the modern capitals; the nocturnal vibration of arsenals and docks beneath their glaring electric moons; greedy stations devouring smoking serpents; factories hanging from the clouds by the threads of their smoke; bridges like giant gymnasts stepping over sunny rivers sparkling like diabolical cutlery; adventurous steamers scenting the horizon; large breasted locomotives bridled with long tubes, and the slippery flight of aeroplanes whose propeller has flag-like fluttering and applauses of enthusiastic crowds.

Futurism favoured the new, the machine, the strive for an almost post-human clarity of spirit. They were obsessed with the fragmentation and dissection of form, the impact of technological advancement, the shunning of what was perceived to be holding man back. It's probably no coincidence that the movement had a profound impact on Mussolini and the development of the fascist aesthetic in Italy.

And Gortash has SO many references to the future of Faerun, to the machine, to the Ultimate State of unity without free will, the feeding of brains to technology which we see in a number of prototypes, of a new age for Baldur's Gate through combining technologies and destroying the systems of the past. He is a man of the present and the future alone!

#this is such an intro to ideas#I am by no means more than a magpie of references and movements#but it struck me immediately

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is why we propose to maintain the concept of the act developed by Kant, and to link it to the thematic of 'overstepping of boundaries,' of 'transgression', to the question of evil. It is a matter of acknowledging the fact that any (ethical) act, precisely in so far as it is an act, is necessarily 'evil'.

We must specify, however, what is meant here by 'evil'. This is the evil that belongs to the very structure of the act, to the fact that the latter always implies a 'transgression', a change in 'what is'.

It is not a matter of some 'empirical' evil, it is the very logic of the act which is denounced as 'radically evil' in every ideology.

The fundamental ideological gesture consists in providing an image for this structural 'evil'. The gap opened by an act (i.e. the unfamiliar, 'out-of-place' effect of an act) is immediately linked in this ideological gesture to an image. As a rule this is an image of suffering, which is then displayed to the public alongside this question: Is this what you want? And this question already implies the answer: It would be impossible, inhuman, for you to want this!

Here we have to insist on theoretical rigor, and separate this (usually fascinating) image exhibited by ideology from the real source of uneasiness - from the 'evil' which is not an 'undesired', 'secondary' effect of the good but belongs, on the contrary, to its essence. We could even say that the ethical ideology struggles against 'evil' because this ideology is hostile to the 'good', to the logic of the act as such.

We could go even further here: the current saturation of the social field by 'ethical dilemmas' (bioethics, environmental ethics, cultural ethics, medical ethics … ) is strictly correlative to the 'repression' of ethics, that is, to an incapacity to think ethics in its dimension of the Real, an incapacity to conceive of ethics other than simply as a set of restrictions intended to prevent greater evil.

This constellation is related to yet another aspect of 'modern society': to the 'depression ' which seems to have became the 'social illness' of our time and to set the tone of the resigned attitude of the ' (post) modern man' of the 'end of history'. In relation to this, it would be interesting to reaffirm Lacan's thesis according to which depression 'isn't a state of the soul , it is simply a moral failing, as Dante, and even Spinoza, said: a sin, which means a moral weakness'.!" It is against this moral weakness or cowardice [lrichete morale] that we must affirm the ethical dimension proper.

Ethics of the Real Z. Zupancic

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

War. War May Finally Change...

In the immersive universe of "Fallout," we are presented with a disturbing reflection of our reality, filtered through the lens of speculative fiction and dystopian narrative. It's fascinating, then, to observe a certain faction of the audience—ardent followers of this series—shying away from the darker shades this narrative paints, preferring instead to bask in the deceptive comfort of nostalgia and simpler story arcs of yore.

Let's dissect this fear, this aversion to looking into the Black Mirror of our entertainment, which reveals more about us than the fictional worlds it portrays. The modern incarnations of "Fallout" under Bethesda's helm have been criticized for their apparent cynicism and focus on the ruins rather than the rebuilding. Critics lament what they perceive as a departure from the foundational themes of the original games, clinging to the idealized past of the franchise's earlier days. But this criticism is shallow and, frankly, misinformed.

Bethesda's "Fallout" has indeed maintained the spirit of its predecessors—it's still rich with wacky antagonists and absurd scenarios, all wrapped in a satirical critique of post-apocalyptic survival and the human condition. What has changed, however, is the depth and fidelity with which these themes are explored. The technical advancements in gaming have allowed for a richer narrative and a more immersive dystopian world, one that forces players to confront uncomfortable truths about society, governance, and morality.

The discomfort some viewers feel towards these narratives stems from their unflinching willingness to hold up a mirror to our society, revealing the twisted reality that we might one day face, or are already facing without even realizing it.

Why then, do some retreat from these reflections, choosing instead to reminisce about the supposedly 'better' and simpler days of older games or less confrontational narratives? It is because these darker, more complex stories demand introspection and often offer no easy answers. In a world increasingly fraught with uncertainty, there is a palpable desire to return to the safety of the familiar and the straightforward. But this desire is a form of escapism that borders on intellectual cowardice.

To reject the evolution of "Fallout" or to deride these narratives for their bleak but insightful observations is to reject the very essence of speculative fiction and its purpose. These narratives are designed not just to entertain but to challenge—to provoke thought, to question norms, and to inspire change. They hold up a mirror not just to what we could become, but to what we are now, the parts of ourselves we are too afraid to examine too closely.

So, to those who are 'scared of the Black Mirror,' who prefer the sugar-coated tales of yesteryears, I say: you are missing the point of our most profound stories. The discomfort you feel is a signal, not of the failure of these narratives, but of their success. It is a challenge to look deeper and to think harder about where we are heading as a society. These stories are a gift—a chance to see the future before it arrives and to steer our collective destiny toward a better outcome.

In conclusion, if you find yourself recoiling from the Black Mirror held up by these series, ask yourself why. Is it the darkness of the mirror you fear, or what you see within it? The answer, though perhaps unsettling, is necessary for true understanding and genuine appreciation of these masterful works of fiction. Denial will lead us nowhere but into the oblivion that these series so powerfully warn against. Embrace the discomfort, engage with the complexity, and perhaps, in the twisted reflections of these black mirrors, war may finally change.

#fallout#war never changes#bethesda#interplay#xbox#distopía#the critical skeptic#social sciences#critical thinking#black mirror#technoogy#future#critique#war may finally change#dark#introspection#hope

0 notes

Text

Lucky On the Homefront

Stephen Jay Morris

12/09/2023

©Scientific Morality.

It is grey and gloomy outside my house. The street is wet and tires splash as vehicles drive by. At night, while I sleep, I dream about what is now called, “The North Miracle Mile District.” I dream about the spring and summer days of my youth, about riding my bicycle, or the time I crashed my skateboard and almost cracked my head. I dream about the times I collected bottles and took them to the drug store for money. I’d watch mini bikers race in the empty Pan Pacific parking lot. I hung out at “Kosher Dog,” listening to the juke box while eating a Chile Dog with greasy fries, and gulping from a large, Dixie cup, full of crashed ice and Coke. Los Angeles in the 1950’s and 1960’s, and even in the 70’s, was a quiet, semi-desert town by the sea. Yes, Los Angelenos had bragging rights about the weather. If it rained half an inch, Angelenos would…let’s say…over-react.

My favorite activity was walking the sidewalks in my neighborhood. Everyone had manicured, green lawns. There were plenty of parking spaces along the streets and room to move. Houses had individualistic, architectural designs. Sorry, there were no post-modern designs. There was a house designed by renowned architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, on Highland Avenue and Beverly Boulevard. That was the most outlandish. To me, I was in the center of the universe. My dad told me how lucky I was to be living in L.A. He actually declared, over and over again, how he had to walk to school, daily, in 12 inches of snow.

During the Vietnam war, when the military was bombing the shit out of innocent men, women, and children in their modest villages, the American military propagandists said the Vietcong was to blame. If you criticized the war, you were Anti-American. Israel is now saying the same thing about its ongoing attacks on Gaza; that their relentless bombing of civilians is Hamas’ fault. Anyone who criticizes Israel is antisemitic. Sound familiar? It sounds like an abusive husband who tells his battered wife, “Why did you make me hit you?!” What did I learn from these historical experiences? Technology may have changed over the decades, but history remains the same. It doesn’t matter who is fighting a war or the political bent it’s about, war is inhumane and unjustifiable.

During the Vietnam era, I was lucky to be in an upscale neighborhood. The nearest evidence of a war that was thousands of miles away, was on college campuses. Antiwar protests were about 10, maybe 7 miles away. My family had made it into this neighborhood by happenstance. I’m certainly glad we didn’t end up in a trailer park! To be completely honest, during my preteens, I was glad to be far from any war, though in 1965, the Watts riots came close. Then in 1993, a riot erupted in my parents’ neighborhood (I had long since moved away). My mom was oblivious to the nature of it, but rioters had set ablaze a well-known business, Sammy’s Camera Shop. I remember my mom saying to me on the phone, as she watched from her back door, “Oh, look at that!” as if she was looking at a painting in a museum. I told my mom to stay safe, and she replied, “I will.” Thankfully, nothing happened to her or my family.

And now, here I am in this bucolic area known as the Catskill Mountains. The wars in Ukraine and Gaza are far, far away. Protests opposing and supporting Israel occur hundreds of miles away. For all of this, I thank my lucky stars. Every time there is a political conflict, the last place you want to be is in a city.

I’m glad that my draft number never came up during the Vietnam war, I would have never survived. Not that I am a coward; I would do anything to protect my family. However, when my country is wrong, it is not an act of cowardice to not participate in its battles. This country’s anti-communist hysteria of the ‘50s killed more American men than the Vietcong ever did.

There are no nuclear bombs in Heaven.

#stephenjaymorris#poets on tumblr#american politics#youtube#anarchism#baby boomers#anarchopunk#anarchocommunism#anti war#american history#united states#anarcho punk#anarchofeminism#anarcho syndicalism#anarcho communism#anarcho socialism#anarcho capitalism

1 note

·

View note

Note

For world building wednesday... Checkpea Chkepi! And/or maybe Vialex bc their name looks cool 👀

I’ll do both!!! Cuz now I’m really excited!! Also this would get Super Long if I did them both attached to this post, so I’ll just do Chkepi’s here.

WORLD BUILDING WEDNESDAY send me the name of a character, and i’ll reply with:

B A S I C S

full name: Chkepi Ahlven

gender: Genderfluid

sexuality: Ace, questioning romantic

pronouns: they/them, with a sprinkling of he/him

O T H E R S

family: The Offering (alleged ancestor), Vlazia Nostez (adoptive older sister)

hatchplace: Renascence

job: NA, weaver, freelance writer/artist

phobias: water/swimming, blood/injury, anything related to pailing

guilty pleasures: baking sweets just for themself

M O R A L S

morality alignment?: Neutral Good

sins - sloth? envy? Cowardice

virtues - patience, charity, humility

T H I S - O R - T H A T

introvert/extrovert: introvert

organized/disorganized: organized

close minded/open-minded: open-minded

calm/anxious: depends on circumstance

disagreeable/agreeable: agreeable

cautious/reckless: cautious

patient/impatient: patient

outspoken/reserved: depends on circumstance

leader/follower: follower

empathetic/unemphatic: empathetic

optimistic/pessimistic: optimistic

traditional/modern: ????

hard-working/lazy: puts a lot of effort into their work but does so at their own pace

R E L A T I O N S H I P S

otp: vvv

ot3: Cilvir/Chkepi/Rembet (Cilvir belongs to @deepwoodtrolls )

brotp: Vlazia / Chkepi (Sibling shenanigans)

notp: any jade or violet

#Asks#Answered asks#ask meme#Chkepi Ahlven#My trolls#also hi!! I love you thank you for sending an ask!!!#character lore

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Why George Orwell's Warning on 'Self-Censorship' Is More Relevant Than Ever

Just as George Orwell warned, governments don't have to be the censors for free speech and free expression to be fatally stifled. By Brad Polumbo Rule One: Speak your mind at your own peril. Rule Two: Never risk commissioning a story that goes against the narrative. Rule Three: Never believe an editor or publisher who urges you to go against the grain. Eventually, the publisher will cave to the mob, the editor will get fired or reassigned, and you’ll be hung out to dry.

The above is a quotation from George Orwell’s preface to Animal Farm, titled "The Freedom of the Press," where he discussed the chilling effect the Soviet Union’s influence had on global publishing and debate far beyond the reach of its official censorship laws.Wait, no it isn’t. The quote is actually an excerpt from the resignation letter of New York Times opinion editor and writer Bari Weiss, penned this week, where she blows the whistle on the hostility toward intellectual diversity that now reigns supreme at the country’s most prominent newspaper.A contrarian moderate but hardly right-wing in her politics, the journalist describes the outright harassment and cruelty she faced at the hands of her colleagues, to the point where she could no longer continue her work:

My own forays into Wrongthink have made me the subject of constant bullying by colleagues who disagree with my views. They have called me a Nazi and a racist; I have learned to brush off comments about how I’m ‘writing about the Jews again.’ Several colleagues perceived to be friendly with me were badgered by coworkers. My work and my character are openly demeaned on company-wide Slack channels where masthead editors regularly weigh in. There, some coworkers insist I need to be rooted out if this company is to be a truly ‘inclusive’ one, while others post ax emojis next to my name. Still other New York Times employees publicly smear me as a liar and a bigot on Twitter with no fear that harassing me will be met with appropriate action. They never are.

Weiss’s letter reminds us of the crucial warning Orwell made in his time: To preserve a free and open society, legal protections from government censorship, while crucial, are not nearly enough.

To see why, simply consider the fate that has met Weiss and so many others in recent memory who dared cross the modern thought police. Here are just a few of the countless examples of “cancel culture” in action:

— A museum curator in San Francisco resigned after facing a mob and petition for his removal simply because he stated that his museum would still collect art from white men. — A Palestinian immigrant and business owner had his lease canceled and restaurant boycotted after activists dug up his daughter’s old offensive social media posts from when she was a teenager. — A Hispanic construction worker was fired for making a supposedly “white supremacist” hand signal that for most people has always just meant “okay.” — A soccer player was pushed off the Los Angeles Galaxy roster because his wife posted something racist on Instagram. — The head opinion editor of the New York Times was fired and his colleague was demoted after they published an op-ed by a US senator arguing a widely held position and liberal colleagues claimed the words “put black lives in danger.’ — A random Boeing executive was recently mobbed and fired because he wrote an article 30 years ago arguing against having women serve in combat roles in the military. — A data analyst tweeted out the findings of a research paper (by a black scholar) about the ineffectiveness of protests and was fired after colleagues claimed their safety was threatened. — Led by progressives as prominent as New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, a woke mob tried to get a Chicago economist fired from his editorship of an economics journal for tweeting that embracing “Defund the Police” undercuts the Black Lives Matter movement’s chances of achieving real reform.

These are just a few examples of many. One important commonality to note is that none of these examples involve actual government censorship. Yet they still represent chilling crackdowns on free speech. As David French put it writing for The Dispatch, “Cruelty bullies employers into firing employees. Cruelty bullies employees into leaving even when they’re not fired. Cruelty raises the cost of speaking the truth as best you see it—until you find yourself choosing silence, mainly as a pain-avoidance mechanism.”

These recent observations echo what Orwell warned of decades ago:

Obviously it is not desirable that a government department should have any power of censorship... but the chief danger to freedom of thought and speech at this moment is not the direct interference of the [government] or any official body. If publishers and editors exert themselves to keep certain topics out of print, it is not because they are frightened of prosecution but because they are frightened of public opinion. In this country intellectual cowardice is the worst enemy a writer or journalist has to face, and that fact does not seem to me to have had the discussion it deserves.

Similarly, the British philosopher Bertrand Russell noted in a 1922 speech “It is clear that thought is not free if the professional of certain opinions makes it impossible to earn a living.”

Some might wonder why it’s really so important to protect speech and thought beyond the law. After all, if no one’s going to jail over it, how serious can the consequences really be?

While understandable as an impulse, this logic misses the point. Free and open speech is the only way a society can, through trial and error, get closer to the truth over time. It was abolitionist Frederick Douglas who described free speech as “the great moral renovator of society and government.” What he meant was that only the free flow of open speech can challenge existing orthodoxies and evolve society. From women’s suffrage to the civil rights movement, we never would have made so much progress on sexism and racism without the right to speak freely.

Silence enshrines the status quo. As John Stuart Mill put it:

If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.

This great discovery process through free-flowing speech first and foremost requires a hands-off approach from the government, but it still cannot occur in a culture hostile to dissenting opinion and debate. When airing a differing view can get you mobbed or put your job in jeopardy, only society’s most powerful or those whose views align with the current orthodoxy will be able to speak openly without fear.

Orwell and Russell were right then, even if we’re only fully realizing it now. Self-censorship driven by culture, not government, erodes our collective discovery of truth all the same.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is Deus Ex Machina always a bad thing? People who didn't like the finale of Avatar are always quick to point out the lion turtle, but I think we both agree the ending was both emotionally and thematically satisfying, and to me that's the most important thing. But my question is: if it IS satisfying, is it still a DEM? After all, DEM usually carries this idea that the ending is ruined and it leaves a bad taste in your mouth, which the Avatar finale doesn't.

Coincidentally, I was thinking about this just the other day, although I wasn’t considering making a post on it.

I think what makes this discussion troublesome is that there are two very different operating definitions for “deus ex machina.” I tend to think of it in terms of the classical definition, so I don’t personally have any problem with it when it’s done well, but most people seem to be operating with something like the same kind of shorthand that has turned “Mary Sue” into a meaningless complaint.

The term translates to ‘god from the machine.’ Wikipedia can give a functional summary of how it was originally employed and the criticisms that arose about it even amongst those old-timey Greeks. My own take is informed by those origins and the Greek myths that I’ve loved since I first learned about them in grade school. In a setting where gods and magic are in play, I don’t see a problem with a god being so moved by the events of the story or the character of the protagonist(s) that they intervene in otherwise impossible scenarios. The key here is that the story needs to justify why the god/power is intervening here and not in all kinds of other situations; if a god comes along and raises someone from the dead, or hands over a magic sword, or whatever, then it needs to be clear why people still die and magic swords aren’t sold at every corner market.

The Lionturtle is indeed a deus ex machina in that it is a god-like power suddenly entering the story to hand Aang knowledge that he would not otherwise have been able to attain. However, AtLA firmly establishes that there are spirits in the world with god-like power. Hei Bai is the first at a relatively small scale (and was another spirit moved by Aang’s steadfast purity to enact a happy ending, hmmm…), but we also see Koh having knowledge that predates the existence of the moon and the ocean, Koizilla being able to smash a whole fleet with the help of the Avatar State, Wan Shi Tong being able to move an infinitely-large library between the spirit and material worlds, and an eclipse of the sun shutting down all Firebending. These are all powers that the normal humans of the setting do not have, but they are all exercised as a result of the intervention of the protagonists, so I think they’re perfectly fine elements to have in the story.

Just about the only thing that might separate the Lionturtle from these other examples is that it seeks Aang out, rather than the other way around. However, I think that’s an oversimplification of the situation, in which we had just gotten an full episode of Aang holding fast to his belief in the sacredness of all life, despite disagreement and harassment from his friends. He meditates in search of an answer, and it’s then that the Lionturtle reaches out. So I think Aang ‘earns’ its attention by his unique beliefs, his steadfastness in the face of painful opposition, and his action in seeking a solution via meditation.

Why does the Lionturtle not reach out to other people? Well, the only pacifists in the franchise are Air Nomads like Aang, and there’s possible evidence that they weren’t all as steadfast when push came to shove. However, I don’t think the fate of the world hinged on whether Gyatso or some other random Air Nomad killed an enemy while fighting; Aang is in a fairly unique situation in that regard. Theoretically, a previous Avatar might have faced the same dilemma that could have been resolved with Energybending, but as we saw of Yanchen, perhaps those Avatars didn’t really seek out another solution besides violence. The Kyoshi novel does a great job handling this, showing Kyoshi struggling with similar questions but finding her own answers that do not match Aang’s. Perhaps Aang really is the first person in an Age who merited the Lionturtle’s intervention. It helps that the intention at the time of writing was for it to be a technique only available to the Avatar, so that definitely limits the potential situations where it might have been relevant.

So we’re left with the question of whether Energybending itself conforms to the established rules of the setting. I personally think it does, quite handily. We saw examples of bending being taken away before, at least on a temporary basis. The death of the Moon Spirit takes away all Waterbending. The eclipse on the Day of Black Sun takes away Firebending for its duration. Ty Lee pokes Qi-points to disable bending even while leaving limbs otherwise functional (sometimes). Those all help clearly establish that bending is tied to the physical body, and specifically the Qi energies flowing through it. We see esoteric manipulation of those energies by way of Waterhealing, Lightningbending, and the time Aang’s spirit is knocked out of his body by physically crashing into a bear-shaped shrine/idol.

So yes, the Lionturtle is a newly-arrived god who imparts special magic to solve a problem that couldn’t otherwise have worked out so neatly, but all the elements are there to make it a workable plot element. If the Day of Black Sun had worked out, would people be complaining about how Deus Ex Machina it is for the gAang to stumble across information on an eclipse coming before the return of Sozin’s Comet that will take away Firebending and allow Aang to confront Ozai without training up to the a higher fighting level?

Well, not if Aang kills Ozai in that scenario, I expect.

The root of the way most people use ‘deus ex machina’ in modern times, I think, links to what Aristotle is said to have been alluding to in that Wikipedia article, and what Nietzsche also seems to be getting at. Specifically, they seem to think it’s better when a tragic story is allowed to end in tragedy, rather than an audience-pleasing happy ending getting tacked on in an act of weakness and cowardice. It’s fair to criticize this (I enjoy tragedy as well as happy endings, when it’s done right), but I think it can be taken too far into a desire for bleak endings in general. It would be more ‘mature,’ the thinking goes, for Aang to have to kill Ozai, be tainted, scream his angst to the sky, and show the audience that Life Is Dark even though it’s a trite message that doesn’t really follow from anything that came before. The thing about Tragedy that a lot of people forget is that it needs to be set up with as much care and earnestness as Deus Ex Machina, or else it’s just as hackneyed and immature.

AtLA is not a tragedy. It is not about the mistakes and flaws of the protagonists piling up into chaos. So the complaint about ‘deus ex machina’ doesn’t even really apply, according to the original controversy about it. Aang is not freed from the consequences of a flaw, because his desire for peace and life is something that’s consistently portrayed as good throughout the rest of the series. It’s built up in his culture, the appreciation for the Air Nomads that’s conveyed despite their flaws, the focus on his being the last survivor of a genocide, and even the subtitle of the series (providing you don’t live somewhere that got the much more generic “Legend of..” title that fits Korra’s more generic legend so much better). It’s not a tragedy if everything is working out until a last minute swerve when all the good things suddenly become bad.

That’s a Comedy, according to certain modern definitions. ;)

The only story that could end with Aang giving up his ideals to kill Ozai using the philosophy and ways of the Fire Nation is a story about how the Fire Nation is right- that morality is secondary to strength and necessity. And if that’s the story being told, wouldn’t it have been easier to just make the Fire Nation the heroes in the first place, slaughtering corrupt pacifist hippies who would rather we all die than fight to improve the world?

No matter how you look at it, people who criticize AtLA’s ending by calling it a ‘deux ex machina’ aren’t doing so by using the text of the story at all. They’re either glossing over how the setup for all the plot elements is all right there in the story, or else they’re doing exactly what the ancient Greeks criticize bad deus ex machina for in the first place by putting the wrong ending on a story. So most who use ‘deux ex machina’ as a criticism aren’t thinking about the nature of Story at all, I think. They’ve heard the term, mistake it for general criticism of ‘unearned’ plot points, and/or use it as justification for their own pretentious fascination with bleak endings.

So, to summarize my answer- yes, DEM can be a criticism in and of itself, depending on the definition in play. It can apply to AtLA, also depending on the definition in play.

But applying DEM to AtLA as a criticism just doesn’t add up.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some thoughts I had on the Sequel Trilogy...

I was listening to a livestream @girllswithsabers did a few days ago, and they really had my gears turning. I've really been thinking about this recently, but until I listened to their livestream, I wasn't sure how to put it into words. And then it all finally kicked. Here's why Reylo is so much more important than just a "ship". It's the heart of this trilogy and the entire saga.

First, all abusive relationships exist on a foundation of a power imbalance. One person has all the power in an abusive relationship. That's not Rey and Kylo. It is impossible for them to be in an abusive relationship because they are EQUALLY powerful in the Force, and Kylo respects her for that. There is a mutual respect, despite opposing ideologies.

They BOTH have things they have to work on and maturing to do before they can come together. Yes, Kylo obviously has done horrible things and he has to come to terms with those things and atone for them, so it wouldn't be good if Rey stayed with him at the end of TLJ. But Rey's greatest strength is her compassion for people. The strongest thing you can do is choose to have compassion and forgive someone who has wronged you, especially if they are taking the steps to change. Any relationship they have will need to come after redemption, and it will.

Snoke and Kylo are the definition of an abusive relationship. Snoke was more powerful than Ben and took advantage of how vulnerable and hurt he was from his family. He made him think that he could rely on no one but him, until Rey came along. Kylo saw that there was someone exactly like him out there who wouldn't try to use him for his powers or his legacy because she is just as powerful as he is. Ben couldn't kill Snoke without Rey, and that's when he found the strength and opportunity to do so.

The biggest point of it all is this: this is Star Wars. It's a space fairy tale meant to be a monomyth not beholden to the laws and morals of our world. Yes, they are based off of real-life problems and scenarios, but it is meant to entertain, first and foremost. It is also meant to have us think about how we can treat people in real life and what happens when we come together as humanity.

Second, because Star Wars is a monomyth, it discussses the relationships between men and women, the masculine and the feminine, like other mythologies do. It does this starting with Anakin and Padmé and how their imbalanced relationship leads to an imbalance in the Force and an overwhelming amount of masculine and not enough feminine.

Episodes I-VI we see that imbalance, even after Vader dies. Nothing in the galaxy was solved. The Sequel Trilogy's sole purpose is to bring balance to the Force. How? By bringing together the Masculine and the Feminine, finally, as equals. It's told from a female gaze because it doesn't just embolden women, but it says that men and women can have both the Masculine and the Feminine and the world can be at peace if we just come together.

Women are also representative of life because we birth babies. It's the men of the Skywalker family that have caused the destruction of the galaxy, and they didn't have an equal woman to help bring balance back to the Force. What does Luke teach Rey in TLJ? That between life and death, cold and warmth, decay and growth there is a balance. Women represent life, men represent death. Both are necessary, both are equal, and both feed into each other. You can't have one without the other. Rey is Light, Kylo is Dark. Too much of either throws things out of balance. The Jedi Council of the prequels, the Empire of the originals.

All of this to say that, from this perspective, that's the story Episodes VII-IX are telling, and that's why it makes sense that Rey and Ben will be together at the end, that they have to be together at the end. Their relationship is deeper than just a romance, and it doesn't make sense for it to go any other way. In fact, if they didn't follow through with it, it would be a waste of a story and a cowardice move. But, as Kathleen Kennedy said, the Force is female! Thank goodness she was overseeing the making of this trilogy. She knows that you need both a man AND woman's perspective when telling stories. We had the male perspective with the other two trilogies. Now it's time for the female perspective.

Yes, a lot of mostly male and some female fans hate Reylo and hate these movies. But Star Wars is trying to shift the storytelling perspective and not only bring balance to the Force, but tell the audience that amazing things happen when women and men come together as equals, that there is peace when done so. And yeah, we are used to seeing romances from a male gaze perspective. We've been watching them for years, and it's hard to enact change. But of all the franchises that can do it and should do it, it's Star Wars because it's a modern mythology.

So yeah, some men and women are going to reject it initially, but the more we tell it the more it'll take root in people and change perspectives. I'm not bashing men at all, just trying to explain why Reylo is important. You certainly don't have to like it, but if you can try and understand why so many women and even men have clung to this trilogy, it's because it's speaking to us this time. And because of that, we can all learn important things from it.

Anyway, Rey and Ben are the Balance, and there is no doubt in my mind that they are going to be together at the end of TRoS. They have to be. From this particular storytelling perspective, it doesn't work any other way. And I suspect maybe that's why Kathleen Kennedy fired Colin Trevorrow in the first place. Maybe he just couldn't see and understand the female gaze story. So really, the fact that we have Kennedy really is the most reassuring reason that we're getting a Ben and Rey happy ending.

Anyway, enough rambling. Whatever your thoughts are on the Sequel Trilogy, whether you love it or hate it, I would encourage you to go in with an open mind in December and really pay attention to what the story is trying to say. Try and understand why so many women love this story, and some men, too!

A HUGE thank you to Girls with Sabers for inspiring this post with their livestream, and for encouraging me to post my thoughts! You should check out that livestream AND their YouTube channel. They have done amazing work, and really they are the ones that started making me think of Reylo from a literary and symbolic angle in the first place. Thanks ladies! 😊❤❤❤

Here's the link to that livestream:

youtube

#the rise of skywalker#reylo#reylo is endgame#reylo shippers#episode 9#star wars tros#star wars#episode ix#ep ix#ep ix speculation

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

DOING THE HARD WORK OF MAKING EVERYONE IN DORIAN GRAY LOOK LIKE A DICK EXCEPTING, WITH LIMITS, DORIAN GRAY