#poor little rich girl (1965)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#Poor Little Rich Girl#edie sedgwick#1960s#60s#1965#1960s vintage#femcel#femme fatale#hyper feminine#vintage#vintage america

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

poor little rich girl (1965) dir. andy warhol on archive.org and on youtube

"A young, jobless woman stays in bed, reads, talks on the phone, smokes cigarettes, makes fresh coffee, and tries on some clothes from a large wardrobe." synopsis via tmdb

#poor little rich girl#poor little rich girl (1965)#andy warhol#edie sedgwick#american film#film#archive#1960s#60s#my post#uploads

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

୨WHIMSICAL MOVIES୧

……………………………………………………………

my letterboxd-deminetly

The Secret of NIMH 1982

The Spiderwick Chronicles 2008

Return to Oz 1985

Mr. Magorium's Wonder Emporium 2007

The Secret Garden 1993

City of Ember 2008

Crimson Peak 2015

The Dark Crystal 1982

Pan's Labyrinth 2006

A Wrinkle in Time 2003

The NeverEnding Story 1984

The BFG 2016

Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events 2004

Strawberry Mansion 2021

Labyrinth 1986

Where the Wild Things Are 2009

Bridge to Terabithia 2007

Beetlejuice 1988

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children 2016

Song of the Sea 2014

Veronica 1972

I Believe in Unicorns 2014

Alice in Wonderland 2010

Stardust 2007

The Little Mermaid 1976

Moonrise Kingdom 2012

The Shape of Water 2017

Belladonna of Sadness 1973

The Last Unicorn 1982

Poor Little Rich Girl 1965

Alice in Wonderland 1999

The Company of Wolves 1984

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝙛𝙞𝙡𝙢𝙨 𝙩𝙤 𝙬𝙖𝙩𝙘𝙝 𝙞𝙛 𝙮𝙤𝙪 𝙡𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙚𝙣 𝙩𝙤…

the velvet underground

✧ ‘Peeping Tom’ (1960) dir. Michael Powell

✧ ‘Poor Little Rich Girl’ (1965) dir. Andy Warhol

✧ ‘Belle de Jour’ (1967) dir. Luis Buñuel

✧ ‘Venus in Furs’ (1969) dir. Jesús Franco

✧ ‘Blue Velvet’ (1986) dir. David Lynch

✧ ‘Velvet Goldmine’ (1998) dir. Todd Haynes

#films to watch if you listen to…#the velvet underground#velvet underground#60s#60s film#films#cinema#movies#film#film frames#cinematography#cinephile#film stills#film is not dead#film tag#screencaps#peeping tom

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

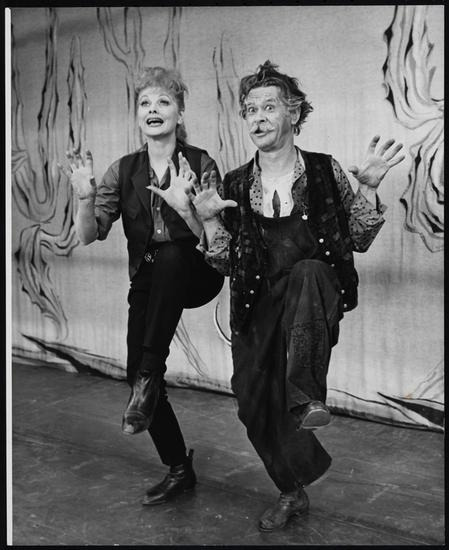

Edie Sedgwick in Poor Little Rich Girl (1965) - directed by Andy Warhol.

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

19 July 2018

Film: POOR LITTLE RICH GIRLS (d. Andy Warhol, 1965, USA).

Forum: Doc Films Format: 16mm

Observations: Pretty good turn out (about 40 or so), the norm for a Warhol screening in Chicago. Doc projected a MoMA print without a hitch.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edie Sedgwick

The 1960s sees a big shift for “it” girls. Instead of focusing on the high society women in America, the public turns to women in the entertainment industry. As Diana kicks off this switch, Edie Sedgwick encompasses the crossover between high society and movie star. Sedgwick is launched to “it” girl status after she becomes one of Andy Warhol’s “Superstars”, a muse and friend to Warhol (Watson). Sedgwick moved to NYC to become a model after inheriting a family fortune, and shortly after, in 1965, she met Andy Warhol. Warhol quickly became enamored by her, calling her “so beautiful but so sick” according to Lester Persky (Revolver, n.p.). He gave her cameos in his films, Vinyl (1965) and Horse (1965), which piqued the underground’s interest in Sedgwick (Watson). Similar to Clara Bow, she seemed to have a silent, dark charisma paired with petite, feminine features catching the public’s intrigue. Warhol began to place her in starring roles, the first being Poor Little Rich Girl (1965) a rather intentional callout of the earlier “it” girls’ socialite status. Her roles were frequently unscripted, promoting her authenticity and allowing Warhol and his audience to fall more in love with her (Revolver). While Warhol’s films were only shown in underground theaters and at Warhol’s The Factory, talk of Sedgewick trickled into the mainstream press. This relationship with Warhol was fleeting and begins to decline in 1965 after she becomes close with Bob Dylan (Stein and Plimpton). Similar to other “it” girls, she swings from one famous man to another. Bob Dylan reportedly had a distaste for Andy Warhol and The Factory and it’s speculated that Edie Sedgwick was the cause (Bals). Another common aspect among “it” girls is the public speculation of their relationships and Sedgwick is no exception. The boundaries of her relationship with Dylan are murky and it’s been speculated Sedgwick was enamoured with Dylan, which he did not reciprocate as he secretly married Sara Lownds in 1965 (Stein and Plimpton). Edie’s relationship with Warhol ended around 1966. Edie was led to believe that Albert Grossman would represent her and she would star in a movie with Dylan, however, none of this came to fruition, and sadly, her career opportunities began to dwindle as her drug use and eating disorder are on the rise (Revolver). Her life and career continue to be defined by men as her story is largely told through Warhol’s or Dylan’s narrative. She overdoses at the age of 28, but her “it” girl legacy remains.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jughead → Betty, A Collection (Part 1)

From Occupy Riverdale, Archie #635 (2012).

From Just Desserts, Archie and Friends #43 (2000).

From Potion Notion, Archie’s Pal Jughead #117 (1999).

From To Play or Not to Play, Archie’s Double Digest #193 (2008).

From Missed Kiss, Archie’s Pal Jughead #181 (2007).

From Message Center, Archie’s Girls Betty and Veronica #116 (1965).

From Goodbye Ol’ Paint, Archie Giant Series #153 (1968).

From Secret Pals, Betty and Me #8 (1967).

From She Needs a Little Christmas, Betty and Veronica #132 (1999).

From Ducat Dupes, Archie’s Girls Betty and Veronica #36 (1958).

From You Never Know..., Archie's Girls Betty and Veronica #128 (1966).

From Vain Campaign, Betty and Me #12 (1968).

From To Sleep, Perchance to Dream, Betty’s Diary #16 (1988).

From Pie in the Sky, Betty and Me #12 (1968).

From Relatively Speaking, Betty and Me #164 (1988).

From Bringing Up the Rear, Archie’s TV Laugh-Out #90 (1983).

From Decisions, Archie’s Girls Betty and Veronica #282 (1979).

From this pin-up, Archie Giant Series #168 (1970).

From Words and Music, Archie’s TV Laugh-Out #79 (1980).

From Fossil Fun, World of Archie #7 (1994).

From The Easy Way Out!, Jughead and Friends #23 (2007).

From The Inspiration, Archie… Archie Andrews, Where Are You? #113 (1998).

From Turnabout, Archie #296 (1980).

From Bye Bye Birdie, Archie COmics Digest #141 (1996).

From Keeping Up Traditions, Betty and Veronica #213 (2006).

From Too Much Love, Betty and Me #14 (1968).

From Something Extra, Archie’s Girls Betty and Veronica #140 (1967).

From Riverdale’s Sweetheart, Betty and Veronica Double Digest #234 (2015).

From Shell Belle, Betty #193 (2011).

From Love Showdown: Part Two, Betty #19 (1994).

From Cheers to You, Betty and Veronica Double Digest #296 (2021).

From Teach Thanks!, Archie Double Digest #319 (2021).

Another from Teach Thanks!, Archie Double Digest #319 (2021).

From Teacher Torture, Betty and Veronica Spectacular #11 (1994).

From Stranger than Fiction, B&V Friends Double Digest #262 (2018).

Another one from Potion Notion, Archie’s Pal Jughead #117 (1999).

From Riverdale Love it or Leaf It, World of Betty and Veronica #8 (2021).

From Comparisons, Archie’s Girls Betty and Veronica #264 (1977).

From Cookout Lookout, Betty’s Diary #13 (1987).

From Catch a Wave, Archie and Friends Double Digest #23 (2013).

From To an Antique Freak, it’s an Obsolete Treat, Jughead #16 (1990).

From Saved by the Bell, Archie Giant Series #506 (1981).

From Scrambled Egghead, PEP Comics #303 (1975).

From Age Before Beauty, Archie Giant Series #13 (1961).

From PEP Digital #87: Need for Speed (2014).

From Blame that Tune, Betty and Veronica Annual #14 (1996).

From Read Between the Lines, Archie and Friends #103 (2006).

From Friends ‘til the End, Betty and Veronica Spectacular #50 (2001).

From Twilite, Archie and Friends #147 (2010).

From The Alternative Whirl, Betty #6 (1993).

From Stuck in the 80s!, Veronica #193 (2009).

From Beautiful Dreamer, Betty #80 (1999).

From Getting Some Smarts, Archie #565 (2006).

From Study Buddy?!, Archie #507 (2001).

From Where in the World are The Veronicas?, Archie and Friends #100 (2006).

From The Grub Grudge, Archie and Friends #26 (1997).

From The Naughty Clause, Archie #639 (2013).

From I Want to be Alone, Betty’s Diary #6 (1987).

From Making It, Everything’s Archie #142 (1989).

From Costume Clash, Archie's TV Laugh-Out #84 (1982).

From Loco Motivated, Everything’s Archie #149 (1990).

And this next panel still from Loco Motivated, Everything’s Archie #149 (1990).

From What's in a Name, Archie at Riverdale High #16 (1974).

From History of Arch, Archie #180 (2001).

From Stamp of Approval, Archie and Friends Double Digest #1 (2011).

From Egology, Tales from Riverdale #37 (2010).

From Weather Vain, Betty and Veronica #58 (1992).

From Blondes Have More What, Betty and Me #38 (1971).

From Out of Sight, Everything’s Archie #11 (1970).

From I Trust Him (As Far as I Can Throw Him!), Archie’s Girls Betty and Veronica #54 (1960).

From Poor Little Rich Whirl, Archie Annual #8 (1956).

From Snowball Effect, Archie’s Funhouse Double Digest #1 (2014).

From The Fall of Jughead and Archie, Jughead and Archie Double Digest #6 (2014).

From My Father’s Betrayal, Archie New Look Series #4 (2010).

From Archie Marries Veronica: The Proposal, Archie #600 (2009).

From Matching Hats, Archie #25 (2017).

From Big Ethel Energy: Episode 5 (2021).

From Blossoms 666 #2 (2019).

From Vampironica #3 (2018).

From Riverdale #8 (2017).

From Like A Tiger, Archie #20 (2017).

From Fall, Betty and Veronica: Senior Year #2 (2019).

And of course there’s this gem from Who Am I, Betty’s Diary #34 (1990).

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hallo Hanna as u kno I’m reading Wuthering heights (I just got 2 the part where she dies........ screammmmmmmmmmm) and I’ve had some tulio on my watchlist for a while :’) + some silent dramas u recommend a lot and I would love some more melodrama recs, bonus points if it’s gothic and I love screaming and blood etcetera so... do your magic ❤️

well definitely watch tulio’s restless blood (1946)!! the way you wanted me (1944) and in the grip of passion (1947) are amazing too. some of my favorite melodramas are the goddess (1934), the wind (1928), the white sister (1924), japanese girls at the harbor (1933), women of the night (1948), the dying swan (1917), after death (1915), apart from you (1933), a woman's sorrows (1937), the poor little rich girl (1917), a geisha (1953), stella maris (1918), rapsodia satanica (1917), shoes (1916), outrage (1950), time to love (1965), alraune (1952), sisters of the gion (1936), one girls confession (1953)...... as for gothic melodramas there’s the curse of the cat people (1944), the ghost and mrs muir (1947), ladies in retirement (1941), the spiral staircase (1946), daughter of darkness (1948), christmas holiday (1944), leave her to heaven (1945), my name is julia ross (1945), born to kill (1947), gaslight (1944), caught (1949)... there are truly so many and tons on my watchlist and countries that i’ve yet to begin exploring

#twink-rights-activist#ask#soo many italian silent melodramas to watch..#ive kind of stayed away from the canon not bc those arent good or anything but yk me

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andy Warhol's Poor Little Rich Girl (1965)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Mile or Two in Joe South’s Shoes

My 2016 Joe South career retrospective, restored from Internet Purgatory.

**********

If you know anything about the true breadth of Joe South’s talents, it’s remarkable to consider that if he is known for anything at all today, it’s for just two songs.

For a hot minute in 1969-70, South looked like he was on the way to a major career. “Games People Play,” the tune that introduced him to the public at large, rose to No. 12 on the national singles chart; a radio ubiquity, it captured two Grammy Awards in 1970, as song of the year and best contemporary song. A year after that breakout hit, he rose to the same chart slot with the stomping, soulful “Walk a Mile in My Shoes,” a number that would be covered in short order by Elvis Presley.

After those two signature songs, Joe South pretty much disappeared off the American pop landscape. It was an astonishing vanishing act, for, in terms of sheer reach and ability, he came as close to genius as a musician can get. He was one of those cats who could do it all.

He wrote almost all of his own material; before his late-‘60s emergence, he had already made his mark writing for others – most notably fellow Georgian Billy Joe Royal – and one of his songs, “Rose Garden,” became one of the biggest country hits of 1970-71 in Lynn Anderson’s hands.

South had all the chops to put across his material. He was a terrific, expressive baritone vocalist. Perhaps more importantly, he was a dynamite guitar player who had honed his craft as an A-list session man in New York and Nashville. And he knew his way around the studio booth, too. He produced nearly all of his own records, and they were big, opulent sides, dressed with strings, horns, and chorales (in the manner of Chet Atkins’ countrypolitan sessions, Atlantic Records’ castanet-snapping R&B outings, and Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound). Yet at the core of South’s early records was the gutbucket sound produced by his family band, the Believers.

Though you could broadly categorize South’s music as “pop,” there was nothing weak or watered-down about his stuff. Like any musician who grew up in the South, he was reared on country music, and all his singing and picking reflected those roots. His style also had a strong R&B backbone and backbeat – not surprising, since one of his early hits as a songwriter, “Untie Me,” was for the Atlanta beach music act the Tams. And he could rock hard, and was unafraid to use the studio tools at his disposal for up-to-the-minute effects: Many of South’s most interesting tracks are overtly psychedelic.

Joe South was primed to go places – almost anywhere he wanted to go, really – but a predisposed dislike for the necessities of the music business, the usual rock ‘n’ roll pitfalls of drugs and alcohol, and, most critically, a devastating family tragedy knocked him out of the game when a brilliant career appeared his for the taking.

He was born Joseph Souter in Atlanta in 1940. His family was attuned to music and the arts: His father played guitar and mandolin, and his mother wrote poetry. He began playing guitar at an early age, while his younger brother Tommy took up the drums. Like many Southern households, the Souters tuned in to the Grand Ole Opry on Nashville’s WSM, as well as the popular local DJ Uncle Eb Brown on WGST.

“Brown” was the air name of Bill Lowery, who had been a mover and shaker in Atlanta’s music community since the early ‘50s as a broadcaster, station executive, and music publisher. It’s said that in an attempt to advance his musical aspirations, young Joe Souter boldly went to visit Lowery during his radio shift. No doubt impressed by his spunk, Lowery took the wannabe performer under his wing. One of his first pieces of advice was that Souter should change his name to the regionally reflective Joe South.

Beginning a professional and personal relationship that would survive for nearly five decades, Lowery brought 18-year-old college dropout South on board at his new independent record label, National Recording Corporation. The young picker was at first employed as a member of NRC’s house band, which also included the future recording stars Jerry Reed and Ray Stevens.

South began cutting singles in his own right for NRC, in varying pop, rock ‘n’ roll, and rockabilly settings. His lone chart record for the company came in 1958: “The Purple People Eater Meets the Witch Doctor,” a sort-of-sequel to two recent novelty smashes, Sheb Wooley’s “Purple People Eater” and David Seville’s “Witch Doctor.” Bouncing onto the chart briefly at No. 47, it was the only bright spot during his time on the label, which went bankrupt in 1961.

He continued to work as a performer, cutting singles unprofitably for the indies Fairlane and AllWood and for MGM, the former home of Hank Williams. But he began to hone his chops as a behind-the scenes player with his writing, playing, and production. He made his first mark with “Untie Me,” which became a No. 12 entry on the U.S. R&B charts in 1962.

He made his biggest impact in 1965-67 as writer and producer of Marietta, Georgia-born Billy Joe Royal’s hits on Columbia Records. Their partnership was announced with the propulsive poor-boy-loves-rich-girl saga “Down in the Boondocks,” which climbed to No. 9 in 1965. Royal road-tested such other South compositions as “Leanin’ On You,” “Rose Garden,” “Yo-Yo,” and “Hush.” The latter track reached No. 52 on the Hot 100 in 1967, but became better known in a 1968 cover by British hard rockers Deep Purple.

South also left his imprint via several noteworthy sessions. He played guitar on Simon & Garfunkel’s first bona fide electric sessions, which became the bestselling 1966 folk-rock album Sounds of Silence. He contributed guitar and bass during the Nashville recording dates for Bob Dylan’s groundbreaking two-LP 1966 set Blonde On Blonde. And in 1967, in the company of FAME Studio’s crack Alabama rhythm section, he laid down the signature guitar licks on Aretha Franklin’s hit “Chain of Fools.”

By 1968, Joe South had little left to prove, and Bill Lowery helped midwife a deal for his protégé at Capitol Records, already the home of such progressive pop-country talent as Glen Campbell and Bobbie Gentry. South was given extraordinary latitude for his first album: He produced the collection, wrote all of the material, and played lead guitar, backed by the Believers, a group that included his brother Tommy on drums and his wife, Barbara, on keyboards.

The resultant LP, Introspect, is an impressive piece of work that didn’t sound quite like anything else on the market. It was a widescreen sound, immense and layered, but at bottom down-home and funky. It drew from several stylistic tributaries. Its lead-off track “All My Hard Times” was an updated rewrite of the old spiritual “All My Trials.” The mocking “Redneck” was a loping countrified lampoon that can be seen as an early anthem of the New South; “These Are Not My People” was an alienated piece of similarly styled, Dylanesque social commentary. The strikingly trippy “Mirror of Your Mind” bore a startling out-of-time passage in its middle, while the equally expansive “Gabriel” was a psychedelic parable cut straight out of the Old Testament.

As great and unique as it was, Introspect was a marketplace failure, and Capitol’s accountants yanked it off the market just as a single drawn from it was beginning to make some noise.

Sporting a unique lead guitar line -- fabricated by South on either, depending on which source you believe, a Coral electric sitar or a Gibson Bell guitar fed through an outboard Echorette echo unit -- and a lyrical hook derived from the title of Eric Berne’s 1964 pop-psychology bestseller, “Games People Play” became a slow-rolling hit. Realizing they may have deleted Introspect prematurely, Capitol decided to capitalize on the song with a hybrid new album.

The Games People Play album – essentially a second debut album for South – resuscitated the title track, “These Are Not My People,” and, in an expanded psyched-up version, the song “Birds of a Feather” (which would appear on three of South’s six Capitol collections). To these were added a couple of new originals (including “Hole in Your Soul,” a frenzied vocal version of the Believers’ two-sided psychedelic instrumental single “Soul Raga”), remakes of several early-‘60s compositions for the Tams and Royal, and a potent rendition of South’s Brill Building-styled 1963 single for MGM, “Concrete Jungle.”

This bizarrely reconfigured opus failed to make any waves, but South gained some name recognition with his “Games People Play” Grammys. Moreover, he made some longer commercial strides with 1969’s Don’t It Make You Want to Go Home? The LP, which ultimately reached No. 60, sported not one but two hit singles: the title cut, a poignant look at the toll wreaked by modern life upon the Southern landscape, and the visceral, gospel-styled “Walk a Mile in My Shoes.” It also contained the most hallucinogenic entry in the South catalog: “A Million Miles Away,” a dense instrumental overlaid with a recitation of the album’s personnel and an extract from a telephone call between South and some staffers at the Nixon White House.

These ambitious records might have suggested to some that South’s potential was unlimited. But there was a problem: He didn’t like to tour, and was at heart a studio animal. He also didn’t respond well to the intense pressure of coming up with material that wouldn’t just equal the sales of his chart records, but would better them.

Perhaps in a hope of shaking things up, the 1971 album Joe South was recorded on home turf at Atlanta’s Studio One, where the Atlanta Rhythm Section was the hot session band of the hour. But -- save for “Rose Garden” (included to cash in on Anderson’s enormous hit with the song) and the “Brown Eyed Girl”-like “Birds of a Feather” (it was the third time around for this belated single release) -- the material, a mix of tepid new tunes and recut warhorses, was scarcely South’s best. The disinterest seemed to carry over on the second LP South issued that year, So the Seeds Are Growing; only seven of the album’s 10 tracks were original compositions.

The disenchanted South’s drug use had begun to escalate, and his brother Tommy, who suffered from depression, was also self-medicating. A turning point came on Oct. 11, 1971, when the younger South took his own life.

The immediate result of this tragedy was South’s final Capitol album, A Look Inside, released in 1972. The LP jacket bore a cover photo of South with an open window in his skull, and the most confessional songs on this dark, unsettling record mirror the graphic perfectly. Its first two songs, “Coming Down All Alone” and “Imitation of Living,” are candid and frightening reflections on drug addiction, and they have lost none of their power. But the record’s true killer, which kicks off with a tart quote of the “Game People Play” melody, is the ironically titled “I’m a Star,” possibly the most blunt, world-weary, and self-reflective deflation of the music industry ever released.

It was a record made by an artist at the end of his tether. As South said frankly in the notes to what proved to be his final album, “I flipped out. I just went completely into the ether in the wake of my brother’s death. I just had to get away, so I went out to the islands, caught Polynesian paralysis and just lived in the jungles of Maui for a couple of years.”

He returned, briefly, in 1975, for his lone release for Island Records, Midnight Rainbows. Though it began promisingly with the fittingly introspective original medley of “Midnight Rainbows” and “It Got Away,” the album – again employing members of the Atlanta Rhythm Section – is disappointingly short on new original material; its strongest tracks are wrenching covers of Jerry Butler’s “For Your Precious Love” and Johnny Adams’ “You Can Make It If You Try.”

The last track on Midnight Rainbows is an instrumental titled “Cosmos,” and that’s exactly where Joe South headed. He was virtually invisible on the public stage from the release of that last LP until his death on Sept. 5, 2012, in Flowery Branch, Georgia. Before Bill Lowery’s death in 2004, he issued a couple of singles on his old sponsor’s independent labels: “Jack Daniels On the Line” for 1-2-3 Records in 1981, “Royal Blue” for Southern Tracks in 1986.

The last work he released during his lifetime arrived as a bonus track on the Australian label Raven’s 2010 repackaging of So the Seeds Are Growing and A Look Inside. Sung by South in a charred latter-day voice, “Oprah Cried” is an apparently faithful account of his appearance on Oprah Winfrey’s talk show, where his story of life’s hard knocks moves the hostess to tears. “Son, I thought I’d heard it all,” she tells him.

Considered in light of what might have been for Joe South, it’s one of the saddest damn songs ever written.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

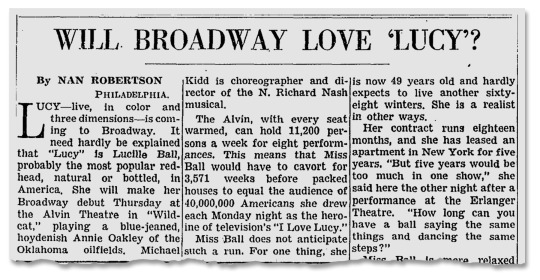

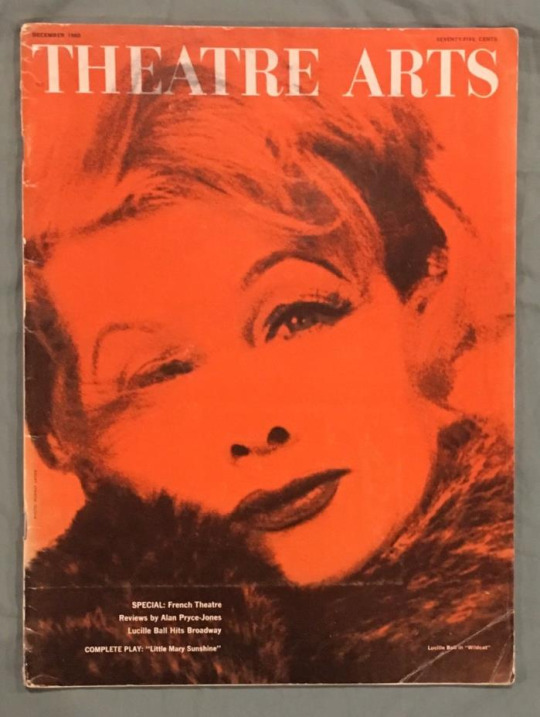

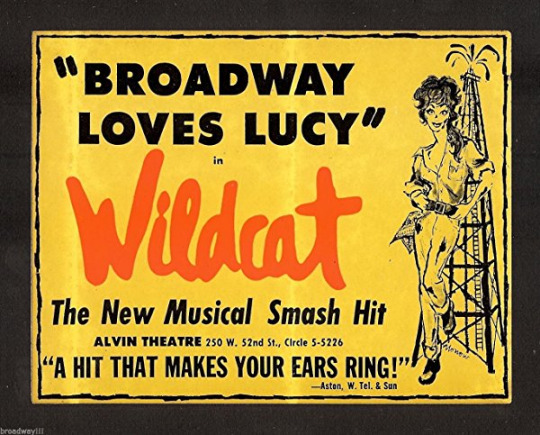

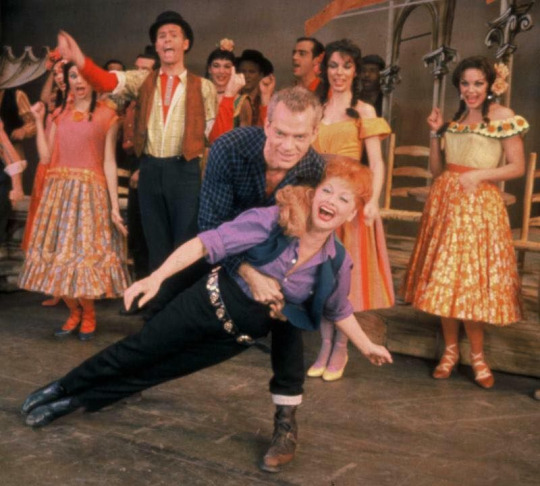

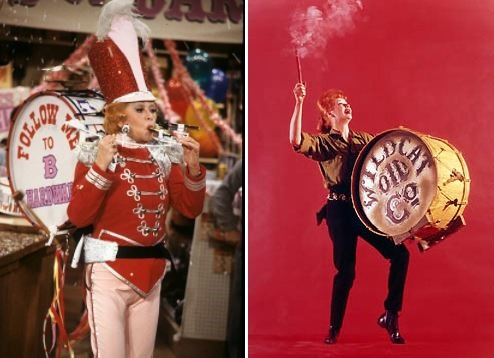

WILDCAT

December 17, 1960

Wildcat is a musical comedy about Wildcat Jackson and her sister who come to oil country in 1912 to strike it rich. She runs into the prowess of Joe Dynamite, and a battle of the sexes and the oil tycoons ensues.

Wildcat wasn’t written with the 48 year-old queen of comedy in mind so when she showed interest, the script by N. Richard Nash had to be radically re-written.

At the start of the 1960’s Ball’s career was taking a new direction. She was leaving her TV personae Lucy Ricardo (as well as her real-life husband Desi Arnaz) behind for newer horizons. It was their company Desilu that would produce Wildcat with Lucy having say over who would be cast as her co-star. After several of her first choices proved not available (including Clint Eastwood), she settled on Keith Andes.

Although Ball was not known for her singing (a fact she traded on in “I Love Lucy”) or her dancing (which she was far better at), she had the determination of Wildcat Jackson to attempt it eight times a week.

Director and choreographer Michael Kidd – known for his athletic dances – would put Ball through her paces. The score was by Cy Coleman with lyrics by Carolyn Leigh, giving Ball the rousing anthem “Hey, Look Me Over!” and the tuneful “What Takes My Fancy.”

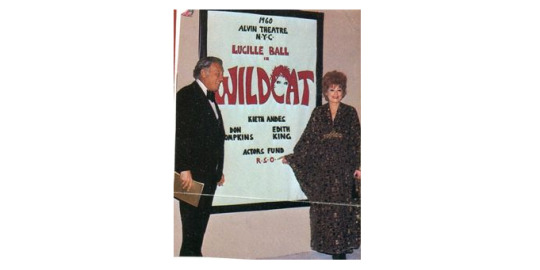

The out-of-town critics were mixed, but obviously adored the red-headed star. The show was headed up the New Jersey Turnpike in trucks headed for Broadway when a serious blizzard stranded the caravan, causing the opening night to be delayed.

With just two previews under their belt, the show opened at the Alvin Theatre (now the Neil Simon) on December 17, 1960. Box office sales were buoyed by audiences expecting to see Lucy Ricardo, not Lucille Ball as Wildy Jackson, so eventually Ball interpolated more and more of her trademark comic inflections into her character.

Then Ball took ill. She left the show for a bit with the idea to return and continue the run. But upon her return she collapsed on stage. Producers decided to close the show for as long as it took her to recover and resume when her strength and health had returned. But the musicians union insisted upon payment during the hiatus, which made the wait financially unfeasible.

All in all, Wildcat lasted 171 performances. It wasn’t Ball’s only musical, however. In 1974 she took on the title role in the film of Mame with mixed to poor critical reactions.

"Then I go to New York with the two children, my mother and two maids. We have a seven-room apartment on 69th Street at Lexington. I’ll start rehearsals right away for a Broadway show, 'Wildcat.’ It’s a comedy with music, not a musical comedy, but the music is important. I play a girl wildcatter in the Southwestern oil fields around the turn of the century. It was written by N. Richard Nash, who wrote 'The Rainmaker.’ He is co-producer with Michael Kidd, the director. We’re still looking for a leading man. I want an unknown. He has to be big, husky, around 40. He has to be able to throw me around, and I’m a pretty big girl. He has to be able to sing, at least a little. I have to sing, too. It’s pretty bad. When I practice, I hold my hands over my ears. We open out of town - I don’t know where - and come to New York in December.” ~ Lucille Ball, TV Guide, July 16, 1960

THE SCORE

Lyrics by Carolyn Leigh and Music by Cy Coleman

Act I

I Hear - Townspeople

Hey, Look Me Over - Wildy and Jane

Wildcat* - Wildy and Townspeople

You've Come Home - Joe

That's What I Want for Janie* - Wildy

What Takes My Fancy - Wildy and Sookie

You're a Liar - Wildy and Joe

One Day We Dance - Hank and Jane

Give a Little Whistle and I'll Be There - Wildy, Joe, The Crew

Tall Hope - Tattoo, Oney, Sadie, Matt and Crew

Act II

Tippy Tippy Toes - Wildy and Countess

El Sombrero

Corduroy Road

You've Come Home (Reprise) - Joe

(*) Songs cut sometime after opening night.

THE CAST

Lucille Ball (Wildcat Jackson) was born on August 6, 1911 in Jamestown, New York. She began her screen career in 1933 and was known in Hollywood as ‘Queen of the B’s’ due to her many appearances in ‘B’ movies. With Richard Denning, she starred in a radio program titled “My Favorite Husband” which eventually led to the creation of “I Love Lucy,” a television situation comedy in which she co-starred with her real-life husband, Latin bandleader Desi Arnaz. The program was phenomenally successful, allowing the couple to purchase what was once RKO Studios, re-naming it Desilu. When the show ended in 1960 (in an hour-long format known as “The Lucy-Desi Comedy Hour”) so did Lucy and Desi’s marriage. In 1962, hoping to keep Desilu financially solvent, Lucy returned to the sitcom format with “The Lucy Show,” which lasted six seasons. She followed that with a similar sitcom “Here’s Lucy” co-starring with her real-life children, Lucie and Desi Jr., as well as Gale Gordon, who had joined the cast of “The Lucy Show” during season two. Before her death in 1989, Lucy made one more attempt at a sitcom with “Life With Lucy,” also with Gordon, which was not a success and was canceled after just 13 episodes.

Keith Andes (Joe Dynamite) was born John Charles Andes in Ocean City, New Jersey, in 1920. Andes played Lucy Carmichael’s boyfriend Bill King on “The Lucy Show” in “Lucy Goes Duck Hunting” (TLS S2;E6) and “Lucy and the Winter Sports” (TLS S3;E3) and played Brad Collins in “Lucy and Joan” (S4;E4) co-starring Joan Blondell. Andes took his own life in 2005 after being diagnosed with terminal cancer.

Valerie Harper (Dancer, right) became one of television’s most recognizable stars as “Rhoda” (1974-78) a spin-off of “The Mary Tyler Moore Show.” She appeared in at “Kennedy Center Presents” honoring Lucy in 1986. She died in August 2019 after a long battle with brain cancer.

Paula Stewart (Janie) appears in the fourth of her six Broadway musicals between 1951 and 1965. Her only series television appearance opposite Lucille Ball was in “Lucy and Harry’s Tonsils” (HL S2;E5) in 1969. In 2017, she published a memoir titled Lucy Loved Me, about her friendship with Lucille Ball.

Hal Linden (Matt, replacement) became one of television’s most recognizable stars as “Barney Miller” (1974-82). He appeared at an “All-Star Party for Lucille Ball” in 1984 and at “Kennedy Center Presents” honoring Lucy in 1986.

Howard Fischer (Sheriff Sam Gore)

Ken Ayers (Barney)

Anthony Saverino (Luke)

Edith King (Countess Emily O'Brien)

Clifford David (Hank)

HF Green (Miguel)

Don Tomkins (Sookie)

Charles Braswell (Matt)

Bill Linton (Corky)

Swen Swenson (Oney)

Ray Mason (Sandy)

Bill Walker (Tattoo)

Al Lanti (Cisco)

Bill Richards (Postman)

Marsha Wagner (Inez)

Wendy Nickerson (Blonde)

Betty Jane Watson (Wildy Understudy)

Dancers: Barbara Beck, Robert Bakanic, Mel Davidson, Penny Ann Green, Lucia Lambert, Ronald Lee, Jacqueline Maria, Frank Pietrie, Adriane Rogers, John Sharpe, Gerald Tiejelo

Singers: Lee Green, Jan Leighton, Urylee Leonardos, Virginia Oswald, Jeanne Steele, Gene Varrone

MRS. MORTON

Lucy met Gary Morton while doing Wildcat on Broadway. She put off their first date due to her rigorous performance schedule. Eventually, he showed up with a pizza just when Lucy was craving one. They married on November 19, 1961.

Comic Jack Carter served as best man at Lucy and Gary’s wedding in 1961. A few weeks later he married Paula Stewart, who played Lucy’s sister Janie in Wildcat. He acted in “Lucy Sues Mooney” (TLS S6;E12).

“HEY LOOK ME OVER!”

On June 4, 1976 Lucille is joined by Valerie Harper and Dinah Shore on “Dinah!” to sing her signature song from Wildcat, “Hey, Look Me Over.”

When Lucille Ball was celebrated at “The Kennedy Center Honors” in December 1986, Valerie Harper, Beatrice Arthur, and Pam Dawber sang a song parody of the “I Love Lucy” theme expressing their affection for Lucy. The medley ends with a specially-tailored “Hey Look Me Over”.

In “Lucy and Carol Burnett: Part 2″ (TLS S6;E15) on December 11, 1967, Lucy, Carol, and the ensemble perform “Hey, Look Me Over” with specially written lyrics to suit the episode’s theme of air travel.

In “Lucy Meets Danny Kaye” (TLS S3;E15) on December 28, 1964, the opening of “The Danny Kaye Show” is underscored with the music to “Hey, Look Me Over.”

While David Frost is trying to sleep during a transatlantic flight, Lucy wears her headset and hums along to “Hey Look Me Over” while tapping it out on the glasses with her cutlery. The scene is from “Lucy Helps David Frost Go Night-Night” (HL S4;E12) aired on November 12, 1971.

In “Lucy and Petula Clark” (HL S5;E8) in 1972, Lucy Carter leaves the office singing “Hey Look Me Over.”

On “Life With Lucy,” Lucy’s grandson Kevin plays on the YMCA soccer team The Wildcats. The name of the team is probably a reference to Lucille Ball’s only Broadway show.

In the second scene of “Breaking Up Is Hard To Do” (1986), an un-aired episode of “Life With Lucy”, Lucy comes down the stairs of the living room singing “Hey Look Me Over.”

WILDCAT WILDCARDS

In April 1961, Lucille Ball played softball in Central Park for the Broadway Show League when she was appearing in Wildcat. Julie Andrews (starring in Camelot) was the catcher! The catcher was Joe E. Brown.

In the play Love! Valour! Compassion! Buzz, a gay musical theater aficionado (Nathan Lane on Broadway) breaks the fourth wall (a common conceit of the play) to tell the audience something personal about himself.

The song title was also the title of a 2018 revue about rarely produced musicals at City Center in New York City. Performer Carolee Carmello called it her “hair homage to Lucille Ball.”

~ From the memoir Under the Radar by Clifford David, who played Hal in Wildcat

#Wildcat#Lucille Ball#Lucy#Broadway#Musical#Keith Andes#Gary Morton#Paula Stewart#Valerie Harper#Clifford David#Cy Coleman#Hey Look Me Over#Alvin Theatre#Hal Linden#Richard Nash#Life With Lucy#Here's Lucy#The Lucy Show#TV

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Audition songs for Women “Of a Certain Age”

This one is specifically for the ladies who are no longer ingenues (or who never really were and are finally growing into their character type...more or less the 40+ crowd)! Not all of these are solos, but I’m fairly certain all can be cut to be a good 16 or 32 bars.

List is under the cut for length

Golden Age:

“The Words” from Anne of Green Gables (1965 Charlottetown Festival)

“June is Bustin’ Out All Over” from Carousel

“You’ll Never Walk Alone” from Carousel

“Do You Love Me” from Fiddler on the Roof

“Sunrise Sunset” from Fiddler on the Roof

“Who Taught Her Everything She Knows” from Funny Girl

“If A Girl Isn’t Pretty” from Funny Girl

“Adelaide’s Lament” form Guys and Dolls (overdone, but not so much so that I’d completely discourage its use)

“Everything’s Coming up Roses” from Gypsy

“Rose’s Turn” from Gypsy

“You Gotta Get a Gimmick” from Gypsy

“Before the Parade Passes By” from Hello Dolly

“World Take Me Back” from Hello Dolly

“I Hate Men” from Kiss Me Kate

“So In Love” from Kiss Me Kate

“Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered” from Pal Joey

“Somehow I Never Could Believe” from Street Scene

Late 60s through 1980

“Compliments” from 1776

“Little Girls” from Annie

“So What?” from Cabaret

“What Would You Do?” from Cabaret

“The Ladies Who Lunch” from Company

“Could I Leave You” from Follies

“Losing My Mind” from Follies

“One More Kiss” from Follies (This can also be done by a young soprano as it’s a duet between an older performer and her younger self in the show)

“Say A Little Prayer” from Gigi (the time period’s correct, but is more of a 2015 revival thing than from the original production)

“Thank Heaven for Little Girls” from Gigi (This was a man’s song in the original, but the 2015 revival changed it to being a woman’s)

“Liaisons” from A Little Night Music (for a MUCH older actress)

“Send in the Clowns” from A Little Night Music (a bit overdone from my understanding, so if you’re gonna do it, knock the acting out of the park)

“By the Sea” from Sweeney Todd

“Worst Pies in London“ from Sweeney Todd

1980s through 2000

“Patterns” from Baby

“Tale as Old as Time” from Beauty and the Beast

“I Remember How Those Boys Could Dance” from Carrie the Musical

“When There’s No One” from Carrie the Musical

“Memory” from Cats is NOT going on this list cause it’s wayyyyy too overdone (don’t sing it is what I’m saying)

“Some One Else’s Story” from Chess (Sorry belt-y teens, Svetlana should be older)

“Ain’t it Good” from Children of Eden

“Children Will Listen” from Into the Woods

“The Last Midnight” from Into the Woods

“Stay with Me” from Into the Woods

“Perfectly Nice” from Jane Eyre (yes, it was on Broadway in 2000, but it was written in the 90s)

“A Slip of A Girl” from Jane Eyre

“And the Moon Grows Dimmer” from Kiss of the Spider Woman

“I Do Miracles” from Kiss of the Spider Woman

“Mamma Mia” from Mamma Mia

“Like it Was” from Merrily We Roll Along

“The Garden Path to Hell” from The Mystery of Edwin Drood

“Puffer’s Confession” from The Mystery of Edwin Drood

“My Husband Makes Movies” from Nine

“I Just Wanna Be A Star” from Nunsense

“A Word from Reverend Mother” from Nunsense

“Mama Will Provide” from Once On This Island (While versions of the show exist that don’t focus on race, the show is set in the Caribbean--specifically on Hispaniola)

“Ti Moune” from Once on This Island

“Back to Before” from Ragtime

“The Stuff” from Reefer Madness

“I Hate Musicals” from Ruthless

“Teaching Third Grade” from Ruthless

“Just One Step” from Songs for A New World

“Stars and the Moon” from Songs for A New World

“Children and Art” from Sunday in the Park with George

“As If We Never Said Goodbye” from Sunset Boulevard

2000 through the Present

“5 to 9″ from 9 to 5

“My Favorite Moment of the Bee” from The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee

“Lucky” from A Little Princess

“Just Around the Corner” from The Addams Family

“Close the Door” from Anastasia

“Land of Yesterday” from Anastasia

“Omar Sharif” from The Band’s Visit (This is pushing it a little--Dina is like late 30s-ish iirc)

“Everything Happens” from Bandstand

“Always Better” from Bridges of Madison County

“I Hate the Bus” from Caroline or Change (another one where the character’s race should really be considered before you choose to use this piece)

“I’m Here” from The Color Purple (another great piece for a black actress)

“Me and the Sky” from Come From Away

“As We Stumble Along” from The Drowsy Chaperone

“Days and Days” from Fun Home

“The Cake I Had” from Grey Gardens

“Will You” from Grey Gardens

“I Know Where I’ve Been” from Hairspray (you really shouldn’t use this for an audition if you’re white...or even white-passing--I say this as a white-passing POC)

“Miss Baltimore Crabs” from Hairspray

“Always Starting Over” from If/Then

“Enough” from In the Heights (You guys are smart, don’t make me say the thing about racial sensitivity again)

“Paciencia y Fe” from In the Heights

“Forgiven” from Jagged Little Pill

“Smiling” from Jagged Little Pill

“Uninvited” from Jagged Little Pill

“Ireland” from Legally Blonde

“Ireland (Reprise)” from Legally Blonde

“Beautiful Boy” from Lestat

“The Beauty Is (Reprise)” from Light in the Piazza

“Dividing Day” from Light in the Piazza

“Fable” from Light in the Piazza

“I Want the Good Times Back” from The Little Mermaid

“Poor Unfortunate Souls” from The Little Mermaid (putting this in this section because this is when the stage show was created)

“Poor Unfortunate Souls (Reprise)” from The Little Mermaid

“Days of Plenty” from Little Women

“Here Alone” from Little Women

“Feed the Birds” from Mary Poppins

“Brimstone and Treacle” form Mary Poppins

“What’s Wrong With Me (Reprise)” from Mean Girls

“That’s Rich” from Newsies

“I Miss the Mountains” from Next to Normal

“There is Music in You” R+H’s Cinderella

“Haven’t Got a Prayer” from Sister Act

“My Most Beautiful Day” from Tuck Everlasting

“A Privilege to Pee” from Urinetown

“An Old Fashioned Lesbian Love Story” from The Wild Party (Lippa)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

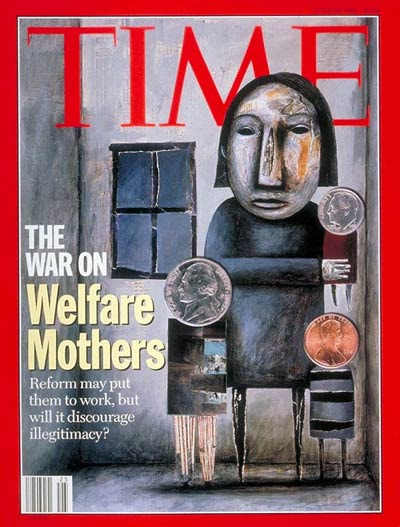

The Mommy Myth: The War Against Welfare Mothers (Part One)

This gif is from the 1970s film Claudine, a romantic comedy starring James Earl Jones and Diahann Carroll about a garbage man and a welfare mother trying to make the relationship and where he helps provide for her home and kids without the social worker checking in.

We check in with The New Yorker, who took a break from their cartoons to cover a welfare mother named Carmen Santana (not her real name): she is Puerto Rican American (and judging by the text’s descriptions of her “wide nose”, complexion, curly dark hair, and thick lips, she must be Afro-Latina) who weighs over 200 lbs and boy the writer was having a field day describing her heft and body. She has no interest in “national or international events” (common flaw that goes across class lines), she spends her day watching soap operas, cursing in Spanish and giving her many kids “a good cuffing” and they just throw the trash out the window. Her kitchen is filthy and her philosophy is “what will be, will be” (a common thing) and sits all the time even when she is cooking while her kids’ bedroom is decorated with obscene graffiti; she had her first child at age 15 and went on to have eight more kids by three different men and her mother had three children by different men and now Carmen’s daughter is also on welfare. She spends the money from Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) on makeup and perfume and hair (honestly wasn’t that a thing at some point? Like Midge Maisel and her mother make sure their husbands never see them without perfect hair and makeup) and junk food for the kids and she also plays the numbers where she spends her winnings on “jewelry , beer, and liquour” and “trips to Puerto Rico”. I guess we are not supposed to sympathize with this woman.

Carmen was an example of a stereotype that was used to represent and demonize welfare mothers. Johnnine Tillmon, the first chairwoman of the group National Welfare Rights Organization saw welfare and the stereotypes as a feminist issue.

I’m a woman. I’m a black woman. I’m a poor woman. I’m a fat woman. I’m a middle-aged woman. And I’m on welfare. In this country, if you’re any one of those things---poor, black, fat, female, middle-aged, on welfare---you count less as a human being.

She even said that the biggest reason that people believe the stereotype of the welfare mother is that they are “special versions of the lies that society tells about all women”, sadly she wasn’t listened to in the mainstream media where welfare mothers were deviants in a culture that valued the rugged individual, relentless hard work and sacrifice, slim bodies aided by Bowflex or Thighmaster, and shiny blond hair with perky smiles. Yo because of this stereotype, women of color with several children are considered suspect. It was also another way to pit moms against moms, the resentment of packing the kids’ lunch and work at a dull 9 to 5 job or scrub the kitchen floors while this stereotype gets to have sex with whoever and drink booze with tax dollars. Even Time magazine went in:

Here’s a few facts: the average welfare family in 1994 had three members, the mother and two children. 39% were White and 37% were Black, African Americans numbered 12% of the national population but were about 35-37% of the welfare population and African Americans were three times as likely as White Americans to live below the poverty level. Only 10% of AFDC mothers had four or more children and 80% had one or two kids and figures in 1993 shown 75% of adults left welfare within two years and 1/2 of single mothers worked while on welfare and 1/3 were working to supplement the minuscule allotment and get off from unemployment. But that was lost on the media that focused on families with two or more generations on welfare (a tiny fraction of welfare recipients) even focusing on unwed teen welfare moms because they were...SHOCKING! Only 1% were teen mothers. Welfare mothers were known only by first name and she lived in the urban decay of New York, Camden (New Jersey), Chicago, or Detroit; they were black and unmarried and had a bunch of kids who don’t share a common biological father and she smoked and painted her nails and gave soda to her baby (OMG imagine 2010s soda freaks) and her face was pixelated in the media. Some of them were depicted as cynical about life and motherhood, it wasn’t sexy for them and at least they felt ambivalence (which was soooooo disco era).

youtube

Then came the 1990s where the moderate Democratic Clinton administration introduced “Welfare Reform” where President Bill Clinton ended “welfare as we know it” and he was just following his predecessors: Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George Bush (the first) regarding their attitude towards welfare recipients. The Welfare to Work program who were being trained by job placement programs that prepared them for low-paying jobs in retail and in service and the resources for job training were limited (also if your hours took you away from your kids?). Also it was hard for welfare to work moms working to move up in their jobs and often mostly got gigs like seasonal retail.

The depiction of welfare mothers was different from the celebrity mom: she wasn’t ascribed emotions where her eyes welled up with tears or laughed, she wasn’t well lit with a light or a rosy focus, never seen holding her child up or clutching the child and magazines like Redbook or McCall’s never did a cover story with a welfare mom and her kids done up and showing the readers fun things they do with little or no money or touring New York City on $10 for a day or games to play while waiting in long lines (honestly that is a good idea, someone pay Susan and Meredith if the magazines do that). Also if you were a woman of color, especially a young one or a poor one (or both) you weren’t supposed to have the “baby lust” so gushed about in celebrity mom profiles; trust me I grew up a Latina kid in Central California and many older women like my mom would worry about the girls that want to have babies so bad or fall in love hard and fast, a young Karen Wheeler in 1967 can give all to family and babies and staying home but it is more precarious for a young girl of color.

The media depiction of poor people wasn’t always so negative: political scientist Martin Gilens found that when the “War on Poverty” began, where the Lyndon B. Johnson administration focused on eliminating poverty and started programs like Head Start rather than piss on poor people, coverage focused on poor white people in rural areas like Appalachia or in the Rustbelt where mines or factories closed down, these were the faces of The Grapes of Wrath, the Joad family who fought against hardship on their way to a better life. After Michael Harrington published his book The Other America, public support for ending poverty was strong. But then came the riots in Watts, Newark, and Detroit (just a few) where mostly people of color fought back against law enforcement and the media used images of African-Americans to illustrate their pieces on welfare, which reinforced stereotypes about welfare and as the coverage became more negative, the skin color got darker (even though statistics then and now showed many more white recipients of welfare)

How about how the face of welfare became so feminized? In the 1930s, when the Welfare program and Social Security began under the New Deal by President FDR, a lot of women of color were barred from welfare because of discriminatory practices, this changed with the Civil Rights Movement which opened up some doors for women of color to get assistance for their children and households. Before the Welfare recipient was faceless or usually a man, who got rich off welfare and bought Cadillacs with the money, something that Richard Nixon really clung to and he asked Johnny Cash to perform the song “Welfare Cadillac” at a White House event sparking controversy. Indeed when Cash met with Nixon, he gave him a private concert with songs that were more compassionate and less reactionary than what Nixon wanted. In the early 1960s, magazines like Look or Reader’s Digest wrote to readers about women who sent their many children to beg for money while the mother ate steak with their boyfriend, or worse, spent the money on narcotics and kept giving birth to more than 10 kids. The image of poor, fertile mothers on taxpayer money was more infuriating than that of a able-bodied man getting the money, but making welfare moms work was shocking (as the system was designed for widows to stay home with their children and not worry about money), even a stinging David Brinkley chafed at leaving kids at a daycare center...it would cost the taxpayer more.

Ronald Reagan coined the term “welfare queen” (look it up) and made exaggerated anecdotes and given how people were drawn to him (looking at you Mike and Nancy’s parents), he was believed despite him not citing sources or studies. Reagan voters fell for the image of a welfare mother who spent money for fancy cars, vacations, designer clothes, and played the system (there were a few like Dorothy Woods, but again if this were common, the landscape of the inner city would look a lot different...) It was a dark time, the Religious Right took control, Proposition 13 in California put a limit on property taxes and started many tax revolts to limit government spending, and let’s not forget Ronald Reagan opposed the following:

Civil Rights Act of 1964

Voting Rights Act of 1965

Fair-Housing Legislation in California

Legislation to declare Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday as a national holiday

How does that Reagan/Bush ‘84 sign look Ted and Karen?

Stay tuned.....

#The Mommy Myth#susan j douglas#meredith michaels#women in media#motherhood#motherhood in media#1970s#1980s#1990s#2000s#Welfare Mothers#women of color#racism#sexism#fat shaming#classism#The New Yorker#Johnnie Tilllmon#Time magazine#Aid to Families with Dependent Children#Unemployment#sensationalism#Sensationalization#Teen Moms#Clinton Administration#Bill Clinton#reagan administration#bush administration#Nixon Administration#Ronald Reagan

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Follow me on INSTAGRAM @demidelanuit

Andy Warhol classic from 1965, Poor Little Rich Girl...

9 notes

·

View notes