#polynesian voyagers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

DID POLYNESIAN VOYAGERS REACH THE AMERICAS BEFORE COLUMBUS?

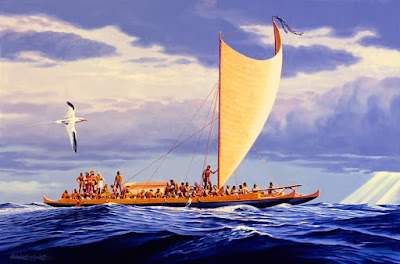

History.com - May 25, 2023 According to science, voyagers from Moananuiākea reached America around 800 years ago. “A 2020 study found that Polynesians from multiple islands carry a small amount of DNA from indigenous South Americans, and that the moment of contact likely came some 800 years ago…” Polynesian voyagers sailed without a compass or any other nautical instruments. Yet by reading the stars, waves, currents, clouds, seaweed clumps and seabird flights, they managed to cross vast swaths of the Pacific Ocean and settle hundreds of islands, from Hawaii in the north to Easter Island in the southeast to New Zealand in the southwest. Evidence has mounted that they likewise reached mainland South America—and possibly North America as well—long before Christopher Columbus. “It’s one of the most remarkable colonization events of any time in history,” says Jennifer Kahn, an archeologist at the College of William & Mary, who specializes in Polynesia. “We’re talking about incredibly skilled navigators [discovering] some of the most remote places in the world.” Tracing Polynesian Ancestry Based on linguistic, genetic and archeological data, scientists believe that the ancestors of the Polynesians originated in Taiwan (and perhaps the nearby south China coast). From there, they purportedly traveled south into the Philippines and further on to New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago, where they mixed with the local populace. By around 1300 B.C., a new culture had developed, the Lapita, known in part for their distinct pottery. These direct descendants of the Polynesians rapidly swept eastward, first to the Solomon Islands and then to uninhabited Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Fiji, and elsewhere. “The Lapita were the first ones to get into remote Oceania,” says Patrick V. Kirch, an anthropology professor at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, and author of On the Road of the Winds: An Archeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact. “It was really a blank slate as far as humans were concerned.” By the 9th century B.C., the Lapita had made it as far as Tonga and Samoa. But then a long pause ensued without further expansion. Researchers note that, beyond Tonga and Samoa, island chains are much further apart, separated in some cases by thousands of miles of open ocean, and that the winds and currents generally conspire against sailing east. Perhaps Lapita boats simply weren’t up to the task. Moreover, as Kirch points out, the closest coral atolls had not yet stabilized by that time. “It’s possible that there was some voyaging past Samoa,” he says, “but they would have found just coral reefs and not actual land they could settle.” Double-Hulled Canoes Accelerate Expansion During the long pause, a distinct Polynesian culture evolved on Tonga and Samoa, and voyagers there gradually honed their craft. In time, they invented double-hulled canoes, essentially early catamarans, lashing them together with coconut fiber rope and weaving sails from the leaves of pandanus trees. These vessels, up to roughly 60-feet long, could carry a couple dozen settlers each, along with their livestock—namely pigs, dogs and chickens—and crops for planting. “They now had the technological ability and the navigational ability to really get out there,” Kirch says. Though the exact timeline has long been disputed, it appears the great wave of Polynesian expansion began around A.D. 900 or 950. Voyagers, also called wayfinders, quickly discovered the Cook Islands, Society Islands (including Tahiti), and Marquesas Islands, and not long after arrived in the Hawaiian Islands. By 1250 or so, when they reached New Zealand, they had explored at least 10 million square miles of the Pacific Ocean and located over 1,000 islands. “You can fit all of the continents into the Pacific Ocean,” Kahn explains. “It’s a huge, huge space to traverse.” Even the tiniest and most remote islands, such as Pitcairn, did not escape their notice. As Kirch points out, no one else in the world was remotely capable of such a feat at that time. “Around 1000 A.D., what were Europeans doing?” Kirch says. “Not much in the way of sailing.” He adds that, as late as the 15th century, even the most accomplished European seamen, like Vasco da Gama, were merely hugging the coast. Easter Island Among Many Inhabited by Polynesian Voyagers The Polynesians did not have a system of writing to record their accomplishments. But they did pass down stories orally, which tell, for example, of how Hawaiian settlers came from Tahiti, more than 2,500 miles away. “Where the sun rises, in Hawaiian understanding anyway, is a place where the gods reside and our ancestors,” says Marques Hanalei Marzan, cultural advisor at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. “To get to that place is probably one of the reasons why the migration east continued.” (As an April 2023 study confirms, Polynesian voyagers sometimes sailed west as well into what’s commonly referred to as the Polynesian Outliers.) Each island chain developed its own unique characteristics. On Easter Island, for instance, the inhabitants constructed giant stone statues. Yet all Polynesians spoke related languages, worshipped a similar pantheon of gods, and built ritual sites with shared features, Kahn explains. The various islands also maintained at least some ties with each other, particularly during the heyday of Polynesian expansion. “It’s not just that they came from a place and left and never made their way back,” Marzan says. “They actually continued those relationships.” Evidence that Polynesian Sailors Reached Americas Most experts now believe the Polynesians crossed the entire Pacific to mainland South America, with Marzan saying it happened “without question.” Stanford University biologist Peter Vitousek has similarly told HISTORY that “we’re absolutely sure,” putting the odds of a South American landfall in the 99.9999 [percent] range.” For one thing, experts note that Easter Island (also known as Rapa Nui) lies only about 2,200 miles off the South American coast, and that Polynesian voyagers, capable of locating a speck of rock in the vast Pacific, could hardly have missed a giant continent. “Why would they have stopped?” Kahn says. “They would have kept going until they couldn’t find any more.” Genetic evidence backs up this assertion. A 2020 study found that Polynesians from multiple islands carry a small amount of DNA from indigenous South Americans, and that the moment of contact likely came some 800 years ago (not long after the Vikings, the best European sailors of their era, made landfall on the Atlantic coast of the Americas). Archeologists have likewise found the remains of bottle gourds and sweet potatoes, both South American plants, at pre-Columbian Polynesian sites. Some scientists speculate that the sweet potato could have dispersed naturally across the Pacific, but most agree that the Polynesians must have brought it back with them. “Try to take a sweet potato tuber and float it,” Kirch says. “I guarantee it won’t float very long. It will sink to the bottom of the ocean.” Poultry bones from Chile appear to show that Polynesians introduced chickens to South America prior to the arrival of Columbus, though some scientists have disputed these findings. Meanwhile, other researchers analyzing skulls on a Chilean island found them to be “very Polynesian in shape and form.” Less evidence ties the Polynesians to North America. Even so, some experts believe they landed there as well, pointing out, among other things, that the sewn-plank canoes used by the Chumash tribe of southern California resembled Polynesian vessels. What Happened to Polynesians in Americas? No Polynesian settlement has ever been unearthed in the Americas. It therefore remains unclear what happened upon arrival, particularly since, unlike the Pacific islands, these landmasses were already populated. Perhaps, Kahn says, “they got up and left and went back.” When Captain James Cook explored the Pacific in the late 1760s and 1770s, thus ushering in a wave of Western imperialism, he recognized the Polynesians’ exemplary sailing skills. “It is extraordinary that the same nation should have spread themselves over all the isles in this vast ocean, from New Zealand to [Easter Island], which is almost a fourth part of the circumference of the globe,” he wrote. Eventually, however, as they colonized the islands and suppressed native languages and cultures, Western powers began to downplay Polynesian achievements, according to Marzan, who says they assumed “that the people of the Pacific were less than.” Some falsely claimed, for instance, that Polynesian sailors had merely drifted along with the winds and currents. (It didn’t help that, at the time of European contact, many Pacific Islanders no longer used large, oceangoing canoes. Some, like those on Easter Island, had already chopped down all the tall trees needed to produce them.) Worst of all, European diseases decimated the Polynesian population. “It was this massive, devastating loss,” Kirch says. “And when you have that, your society really falls apart.” Before long, most remaining Polynesians began sailing with Western techniques. More recently, though, the old traditions have been revived, starting around 1976, when the Polynesian Voyaging Society sailed, without instruments, from Hawaii to Tahiti. They have since embarked on numerous other expeditions, including a worldwide voyage from 2013 to 2017. “The Polynesian Voyaging Society has really inspired many cultures across the Pacific to reconnect with their traditional practices,” Marzan says. Once again, double-hulled canoes are plying the ocean.

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

These four movies were peak disney/pixar animation. The storytelling, magical realism, and cultural exploration of diversity was everything!

so i really love disney/pixar + intergenerational healing

#encanto#turning red#coco#moana#pixaredit#disneyedit#mirabel madrigal#moana waialiki#meilin lee#miguel rivera#the madrigals#the riveras#the red pandas#polynesian voyagers#storytelling#intergenerational trauma#intergenerational relationships#intergenerational healing#❤️🩹#magical realism#cultural diversity

391 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Moananuiākea voyage starts on 6/15

The Hōkūleʻa, a traditional-style double-hulled oceanfaring canoe, is about to start a 4-year circumnavigation of the Pacific Ocean! They've been sailing around Alaska lately, where they're going to start the official journey on 6/15.

(Map from this announcement post [link]) The journey is planned by the Polynesian Voyaging Society [link], which is keeping alive Polynesian wayfinding (navigating on the ocean without instruments) and voyaging. They're super cool, check out their website. They have a bunch of neat videos about the journey so far on their Youtube channel [link]. Here's one with some absolutely gorgeous shots of this giant double-hulled Polynesian canoe hanging out around glaciers and huge snowy mountains.

youtube

I'm really excited to keep an eye on this.

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another spot we finally got to visit on a trip to Denver was ADRIFT🗿 In contrast to Hell or High Water, ADRIFT is going for a more classic (but definitely elevated) Polynesian Pop dining experience in the vein of Trader Vic’s, and manages to do a lot with a fairly small location! The food we had was great, there was a good mix of classic tiki drinks & new school cocktails and they even served the drinks in tiki mugs, which is always a plus to me.

This spot has a two-hour visit limit & I would love to visit again, just sit at the bar & try a couple more of their cocktails! 🍹🍹🍹

#tiki#tiki bar#tiki drinks#cocktails#denver#colorado#Polynesian pop#tropical drinks#don the beachcomber#trader vic#trader sams#tiki revival#jungle river boat voyages

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

How the Night Sky Was Key to Our Survival | BBC Ideas

For most of human history, understanding the night sky was not the preserve of scientists, but a precious tool for our survival. Animation: Oliver Smyth, Heather Gratton, Ceri Barnes Narration: Kanishk Tharoor, academic consultant: Prof Clive Ruggles With thanks to Virginia Mills & Rupert Baker at the Royal Society Made in partnership with @royalsociety Subscribe to BBC Ideas 👉 https://bbc.in/2F6ipav

____________________________ Do you have a curious mind? You’re in the right place. Our aim on BBC Ideas is to feed your curiosity, to open your mind to new perspectives, and to leave you that little bit smarter. So dive in. Let us know what you think. And make sure to subscribe! 👉https://bbc.in/2F6ipav Visit our website to see all of our videos: https://www.bbc.com/ideas

#Youtube#night sky#constellations#stars#galaxy#planet#navigation#voyage#sea faring#polynesian#celestial enrichment#the night sky#starry night#night under starry skies#night under the stars#under the starry skies#starry sky#horizon#celestial odyssey#the celestial odyssey#stellar enrichment#voyages#marine voyages#celestial ceiling#under the heavens#under the milkyway#under the stars#the heavens above#the heavens#seasons

1 note

·

View note

Text

I support this product idea on LEGO Ideas, and you should, too!

#lego#lego ideas#product idea#polynesian#wayfinder#maritime#sailors#sailing#explore#exploration#ocean#pacific islander#pacific islands#hawaii#hawaiian#canoe#voyage#voyager#manta ray

0 notes

Text

Worldwide Voyage: History of Hokule’a and Polynesian Voyaging

0 notes

Text

YES!!!!! Thank you so much for writing this up, @jinlinli. I've been obsessed with this story for years and every time I buttonhole unsuspecting friends and acquaintances and bellow

"OKAY BUT DID YOU KNOW MOANA IS PRACTICALLY A TRUE STORY?"

in the most normal way possible, none of them know about it. It baffles me! It ASTOUNDS me! I want everyone to know!

I so appreciate that you collected all these names in one place and gave credit to the lineage of seafarers who shaped so much of the Second Hawaiian Renaissance.

Also: the crew of Hōkūleʻa have been doing a great job documenting her current circumnavigation on their blog if you wanna get teary-eyed about the power of seafaring and community. I managed to catch a glimpse of her in Juneau before she left and it was a bucket list-level item for sure.

The Hawaiian History Behind Moana

Buckle in kids, this is going to be a long one.

So the story of Moana fits very very neatly with the Disney formula for coming of age stories, and it’s drawn some flak for that. But I would argue that it’s a very Polynesian story. True, the story only really has figures and elements of the traditional myths of Polynesia’s oral history. And true, the directors ultimately chose not to use Taika Waititi’s early script and instead chose to write their own. However, that still doesn’t mean that Moana isn’t a Polynesian story because I believe it very much is. A very specific one in fact.

Keep reading

#hokulea#Hōkūleʻa#polynesian voyaging society#moana#Moananuiākea#traditional seafaring#boat stuff#history#maritime history#hawaiʻi#hawaii#cultural history#voyaging canoe

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the outset of H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898), Wells asks his English readers to compare the Martian invasion of Earth with the Europeans’ genocidal invasion of the Tasmanians, thus demanding that the colonizers imagine themselves as the colonized, or the about-to-be-colonized. But in Wells this reversal of perspective entails something more, because the analogy rests on the logic prevalent in contemporary anthropology that the indigenous, primitive other’s present is the colonizer’s own past. Wells’s Martians invading England are like Europeans in Tasmania not just because they are arrogant colonialists invading a technologically inferior civilization, but also because, with their hypertrophied brains and prosthetic machines, they are a version of the human race’s own future.

The confrontation of humans and Martians is thus a kind of anachronism, an incongruous co-habitation of the same moment by people and artifacts from different times. But this anachronism is the mark of anthropological difference, that is, the way late-nineteenth-century anthropology conceptualized the play of identity and difference between the scientific observer and the anthropological subject-both human, but inhabiting different moments in the history of civilization. As George Stocking puts it in his intellectual history of Victorian anthropology, Victorian anthropologists, while expressing shock at the devastating effects of European contact on the Tasmanians, were able to adopt an apologetic tone about it because they understood the Tasmanians as “living representatives of the early Stone Age,” and thus their “extinction was simply a matter of … placing the Tasmanians back into the dead prehistoric world where they belonged” (282-83). The trope of the savage as a remnant of the past unites such authoritative and influential works as Lewis Henry Morgan’s Ancient Society (1877), where the kinship structures of contemporaneous American Indians and Polynesian islanders are read as evidence of “our” past, with Sigmund Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1913), where the sexual practices of “primitive” societies are interpreted as developmental stages leading to the mature sexuality of the West. Johannes Fabian has argued that the repression or denial of the real contemporaneity of so-called savage cultures with that of Western explorers, colonizers, and settlers is one of the pervasive, foundational assumptions of modern anthropology in general. The way colonialism made space into time gave the globe a geography not just of climates and cultures but of stages of human development that could confront and evaluate one another.

The anachronistic structure of anthropological difference is one of the key features that links emergent science fiction to colonialism. The crucial point is the way it sets into motion a vacillation between fantastic desires and critical estrangement that corresponds to the double-edged effects of the exotic. Robert Stafford, in an excellent essay on “Scientific Exploration and Empire” in the Oxford History of the British Empire, writes that, by the last decades of the century, “absorption in overseas wilderness represented a form of time travel” for the British explorer and, more to the point, for the reading public who seized upon the primitive, abundant, unzoned spaces described in the narratives of exploration as a veritable “fiefdom, calling new worlds into being to redress the balance of the old” (313, 315). Thus when Verne, Wells, and others wrote of voyages underground, under the sea, and into the heavens for the readers of the age of imperialism, the otherworldliness of the colonies provided a new kind of legibility and significance to an ancient plot. Colonial commerce and imperial politics often turned the marvelous voyage into a fantasy of appropriation alluding to real objects and real effects that pervaded and transformed life in the homelands. At the same time, the strange destinations of such voyages now also referred to a centuries-old project of cognitive appropriation, a reading of the exotic other that made possible, and perhaps even necessary, a rereading of oneself.

John Rieder, Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction

#words#hg wells#fiction#science fiction#colonialism and the emergence of science fiction#john rieder

480 notes

·

View notes

Text

find it insane that the terror/erabus expedition and shackleton expedition have so much clout here on tumblr but the hms bounty voyage doesn't. i know none of the adaptations seem that fandomable but there are a lot of them to choose from and the actual event was imo way crazier than any adaptation can capture.

22 y/o upstart with an anxiety disorder mutinies against captain he has a weird psychosocial obsessive bond with who then completes an impossible shackleton-esque journey to save his mens lives. succeeds. majority of the mutineers mutiny again and choose to stay in tahiti while the remaining few take a band of polynesians and go form a colony on a tiny borderline unliveable island in the middle of nowhere.

one of the loyalist survivors then leads a ship to hunt down the mutineers. finds the ones who stayed on tahiti and brings them back to be tried in england but then that ship is dramatically wrecked and several of the mutineers die. few who lived were put on trial and some executed.

while all that is going on, all the men on the remote island are killing each other so the women end up inheriting the place keeping only one male alive and turning the island into a genuinely functioning society with literacy and a schoolhouse and female voting (their descendants are still there today). meanwhile the original captain became governor in australia and got mutinied yet again and imprisoned causing the overthrow of the australian government and the start of the rum rebellion.

and that's just a brief summary leaving out all of the weird stuff...

#hms bounty#age of sail#oceancore#piratecore#english history#mutiny#the bounty 1984#the terror#erabus#polar exploration#ernest shackleton#shackleton expedition#ross expedition#pictairn island#pictairn islands#age of discovery#royal navy#british royal navy#sailing#history#weird

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

The European approach to ocean exploration was brute force: building ships bigger and bigger, scaling up the Mediterranean and coast-hugging ships of prior eras. This made sense for the things these ships were used for: bulk long-distance trade, as the scale and complexity of medieval trade grew; and warfare, where it turns out putting cannons on a boat makes you one of the deadliest things on the ocean.

But there is something that feels much more romantic and elegant about the Austronesian outrigger canoes and the Polynesian catamarans. These don't require massive expenditure of resources and manpower to build, which your society, being smaller in population, doesn't have anyway. You can equip them for long voyages still--Polynesian navigators crossed similar distances as the European navigators. They're fast. And you can still conduct trade with them, although at a smaller scale--which again makes sense, since the Pacific is more lightly populated than the important coastal regions of Afro-Eurasia, and you're trading on behalf of, like, small island polities and not large empires.

The Atlantic has many fewer small island chains, but it still did develop a culture with similar naval technology--the Norse! What was the longship but a war-canoe with a sail? And it served a similar economic function--a platform for small-scale entrepreneurs, generally from small polities (including small island polities like the Faroes and Iceland), also capable of managing transoceanic distances.

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

Website: “here we have some staples of hawaiian cuisine. First: Fruits! Second: SPAM!”

God it sucks when i wanna look up stuff about hawaiian culture and i get this white washed tourist shit

#sorry but i’m not gonna count that#i dont care if modern hawaiians like spam thats a result of WW2#so not originally hawaii#surprise surprise there wasnt canned meat back when the polynesians were voyaging

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the outset of H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds (1898), Wells asks his English readers to compare the Martian invasion of Earth with the Europeans' genocidal invasion of the Tasmanians, thus demanding that the colonizers imagine themselves as the colonized, or the about-to-be-colonized. But in Wells this reversal of perspective entails something more, because the analogy rests on the logic prevalent in contemporary anthropology that the indigenous, primitive other's present is the colonizer's own past. Wells's Martians invading England are like Europeans in Tasmania not just because they are arrogant colonialists invading a technologically inferior civilization, but also because, with their hypertrophied brains and prosthetic machines, they are a version of the human race's own future.

The confrontation of humans and Martians is thus a kind of anachronism, an incongruous co-habitation of the same moment by people and artifacts from different times. But this anachronism is the mark of anthropological difference, that is, the way late-nineteenth-century anthropology conceptualized the play of identity and difference between the scientific observer and the anthropological subject-both human, but inhabiting different moments in the history of civilization. As George Stocking puts it in his intellectual history of Victorian anthropology, Victorian anthropologists, while expressing shock at the devastating effects of European contact on the Tasmanians, were able to adopt an apologetic tone about it because they understood the Tasmanians as "living representatives of the early Stone Age," and thus their "extinction was simply a matter of … placing the Tasmanians back into the dead prehistoric world where they belonged" (282-83). The trope of the savage as a remnant of the past unites such authoritative and influential works as Lewis Henry Morgan's Ancient Society (1877), where the kinship structures of contemporaneous American Indians and Polynesian islanders are read as evidence of "our" past, with Sigmund Freud's Totem and Taboo (1913), where the sexual practices of "primitive" societies are interpreted as developmental stages leading to the mature sexuality of the West. Johannes Fabian has argued that the repression or denial of the real contemporaneity of so-called savage cultures with that of Western explorers, colonizers, and settlers is one of the pervasive, foundational assumptions of modern anthropology in general. The way colonialism made space into time gave the globe a geography not just of climates and cultures but of stages of human development that could confront and evaluate one another.

The anachronistic structure of anthropological difference is one of the key features that links emergent science fiction to colonialism. The crucial point is the way it sets into motion a vacillation between fantastic desires and critical estrangement that corresponds to the double-edged effects of the exotic. Robert Stafford, in an excellent essay on "Scientific Exploration and Empire" in the Oxford History of the British Empire, writes that, by the last decades of the century, "absorption in overseas wilderness represented a form of time travel" for the British explorer and, more to the point, for the reading public who seized upon the primitive, abundant, unzoned spaces described in the narratives of exploration as a veritable "fiefdom, calling new worlds into being to redress the balance of the old" (313, 315). Thus when Verne, Wells, and others wrote of voyages underground, under the sea, and into the heavens for the readers of the age of imperialism, the otherworldliness of the colonies provided a new kind of legibility and significance to an ancient plot. Colonial commerce and imperial politics often turned the marvelous voyage into a fantasy of appropriation alluding to real objects and real effects that pervaded and transformed life in the homelands. At the same time, the strange destinations of such voyages now also referred to a centuries-old project of cognitive appropriation, a reading of the exotic other that made possible, and perhaps even necessary, a rereading of oneself.

John Rieder, Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction

683 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Polynesian Navigation & Settlement of the Pacific

Polynesian navigation of the Pacific Ocean and its settlement began thousands of years ago. The inhabitants of the Pacific islands had been voyaging across vast expanses of ocean water sailing in double canoes or outriggers using nothing more than their knowledge of the stars and observations of sea and wind patterns to guide them.

The Pacific Ocean is one-third of the earth's surface and its remote islands were the last to be reached by humans. These islands are scattered across an ocean that covers 165.25 million square kilometres (63.8 million square miles). The ancestors of the Polynesians, the Lapita people, set out from Taiwan and settled Remote Oceania between 1100-900 BCE, although there is evidence of Lapita settlements in the Bismarck Archipelago as early as 2000 BCE. The Lapita and their ancestors were skilled seafarers who memorised navigational instructions and passed their knowledge down through folklore, cultural heroes, and simple oral stories.

The Polynesian's highly developed navigation system impressed the first European explorers of the Pacific and since then scholars have been debating several questions:

was the migration and settlement of the Pacific islands and into Remote Oceania accidental or intentional?

what were the specific maritime and navigational skills of these ancient seafarers?

why has a large body of indigenous navigational knowledge been lost and what can be done to preserve what remains?

what type of sailing vessels and sails were used to cross an open ocean?

Ancient Voyaging & Settlement of the Pacific

By at least 10,000 years ago, humans had migrated to most of the habitable lands that could be reached on foot. What remained was the last frontier – the myriad islands of the Pacific Ocean that required boat technology and navigational methods be developed that were capable of long-range ocean voyaging. Near Oceania, which consists of mainland New Guinea and its surrounding islands, the Bismarck Archipelago, the Admiralty Islands, and the Solomon Islands was settled in an out-of-Africa migration c. 50,000 years ago during the Pleistocene period. These first settlers of the Pacific are the ancestors of Melanesians and Australian Aboriginals. The small distances between the islands in Near Oceania meant that people could island-hop using rudimentary ocean-going craft.

The so-called second wave of migration into Remote Oceania has been an intensely debated scholarly topic. Remote Oceania is the islands to the east of the Solomon Islands group such as Vanuatu, Fiji, Tonga, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Society Islands, Easter Island, and the Marquesas. What is debated is the origins of the first people who settled in this region between 1500-1300 BCE, although there is general agreement that the ancestral homeland was Taiwan. A dissenting view has been that of Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002 CE) who set out in 1947 CE on a balsa raft called Kon-Tiki that he hoped would prove a South American origin for Pacific islanders. Archaeological and DNA evidence, however, points strongly to a southeast Asian origin and seafarers who spoke a related group of languages known as Austronesian who reached Fiji in 1300 BCE and Samoa c. 1100 BCE. All modern Polynesian languages belong to the Austronesian language family.

Collectively, these people are called the Lapita and were the ancestors of the Polynesians, including Maori, although archaeologists use the term Lapita Cultural Complex because the Lapita were not a homogenous group. They were, however, skilled seafarers who introduced outriggers and double canoes, which made longer voyages across the Pacific possible, and their distinctive pottery – Lapita ware – appeared in the Bismarck Archipelago as early as 2000 BCE. Lapita pottery included bowls and dishes with complex geometric patterns impressed into clay by small toothed stamps.

Between c. 1100-900 BCE, there was a rapid expansion of Lapita culture in a south-east direction across the Pacific, and this raises the question of intentional migration.

Continue reading...

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tikopia house names

For context, the Tikopia are a hunter gatherer group on the small island of Tikopia in Melanesia, but are Polynesian by ancestry and culture. The following excerpts are from Firth's "We, the Tikopia".

Houses in Tikopia bear names, and these are not mere casual appellations given for show, according to a rather stupid European habit, but are intimately related to the native social organization. In fact the name belongs not so much to the building itself as to the site; when one house decays and another is built in its place it bears the same name, even if several generations have elapsed in the interval. For this reason also subsidiary houses are assigned no distinct name; they are described simply as "the cook-house of —" or "the bachelor house of —".

Many house-named are ancestral, used by the family groups for many generations, perhaps since their founding. Some of them are identical with the group name. In a study of kinship the name of a house then invites comparison with that of the residents, and of the family group, know also as the "house", to which they belong.

The usual custom is for the married couple who live in a house to bear the house-named with the terms Pa and Nau preposed for husband and wife respectively. These correspond to the English usage of Mr and Mrs, though they are really kinship terms of address signifying father and mother. Once people have married they are given a house name immediately, and the general public, with the exception of their parents, brothers and sisters, ceases to use their former's names. Together they are known as sa Nea, the name of the house being used in each cases. Only in a few cases have bachelor men been assigned house-names with the usual prefix. This is decidedly exceptional, and occurs only when such a man runs his own household instead of living with married relatives

When a married pair have died, then their eldest son usually assumes the house-name if he has been living with them, or if he moves into the family dwelling, and this process is repeated with each generation. The name of the house (ingoa paito) remains; the name of the individual men (ingoa tangata) disappear, the natives say.

The device of giving permanent names to house-sites has provided the Tikopia with a most valuable mechanism for the preservation of social continuity. Houses decay, men perish, but the land goes on forever. Hence, whatever may be the vicissitudes of the human groups, the dwelling-site name furnishes always a basis of crystallization of kinship units in residential terms. Though the married pair who reside their may change their name in conformity with the needs of the political and religious organization, personal inclination, or the desire for children, the place is known as before. In European society it is the family name which tends to remain constant, whatever be the changes in the name of their house. In Tikopia the opposite obtains, a state of affairs apparently to be correlated with the small society which allows of an intimate personal knowledge of the kinship affiliations of everyone, no matter what name they bear. The permanency of dwelling names, combined with that of orchard names., tends to emphasize that feeling to which every Tikopia gives expression now and again, of the stability of land as compared with the human beings who inhabit it. It would be easy to over-emphasize the importance of this rather superficial native philosophical attitude, but it has its effect in such situations as a quarrel over lands between members of a clan.

Bonus detail: Names often come from far-away places!

All the house-names mentioned so far are regarded as being of local origin. But the Tikopia show a very catholic spirit in their personal nomenclature: voyagers to other lands are prone to bring back foreign names to bestow on themselves and their dwellings; stay-at-homes indulge their thirst for travel by taking over names which they hear from visitors or from their returned kinsfolk, and so endow themselves with at least the semblance of romance. For the desire to voyage overseas, to see strange countries, new lands, is the ambition of every youth or man in the little island, and rarely is it gratified.

Names derived from modern contact with European civilzation are Niukaso, Potiakisi, Pangisi, Melipani, Taone. The first two are expressions for Newcastle and Port Jackson, places visited by men of Tikopia when carried off on labor vessels [Note: he discusses elsewhere that this is rare, in part because Tikopia get physically sick with longing for home after away from long periods]. The third is the phonetic equivalent of Banks, the homeland of the native mission teacher Ellison Tergatok, who is known under the name of Pa Pangisi. His former dwellings of this name in Ravenga is now occupied by a relative of his wife's, Pa Teva. His own house is Taone, in other words Town, so named, probably, because he considered his residence to be the center of civilization in an uncouth land. Melipani is an adaptation of the name of the cruiser Melbourne of the Australian squarian, which visited Tikopia about 1926. The name so attracted one man that he took it for himself and his dwelling without further ado.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

As we start getting more information on the new Narnia adaptation, I see people worrying it won't stay true to C. S. Lewis's vision. Now, as a white British man writing in the 1950s, if Lewis imagined POC characters in his books, it was as

*checks notes*

nobles and royals, leaders and officers, heroes and legends, friends and love interests and protagonists.

Caspian X is a main character in Prince Caspian and The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, and the title character of Prince Caspian. He begins the story as a prince, and ends it taking his rightful place as "lawful King under [Peter] in Narnia both by [Peter's] gift and by the laws of the Telmarines" (Prince Caspian, chapter 13: The High King in Command). Caspian leads a war, overthrows a tyrant, and sails on a journey across the Eastern Ocean to save the lords who had been tricked into being lost at sea because they would have supported Caspian. Brave and loyal, he earns not one, but two, epithets through his actions: "Caspian the Seafarer" (The Silver Chair, chapter 12: The Queen of Underland"; the title is also used several times in The Last Battle) and "Caspian the Navigator" (The Silver Chair, chapter 16: The Healing of Harms").

He is also a Telmarine. The Great Lion himself explains what this means.

"You, Sir Caspian," said Aslan, "might have known that you could be no true King of Narnia unless, like the Kings of old, you were a son of Adam and came from the world of Adam's sons. And so you are. Many years ago in that world, in a deep sea of that world which is called the South Sea, a shipload of pirates were driven by storm on an island. And there they did as pirates would: killed the natives and took the native women for wives, and made palm wine, and drank and were drunk, and lay in the shade of the palm trees, and woke up and quarrelled, and sometimes killed one another. And in one of these frays six were put to flight by the rest and fled with their women into the centre of the island and up a mountain, and went, as they thought, into a cave to hide. But it was one of the magical places of that world, one of the chinks or chasms between that world and this. There were many chinks or chasms between worlds in old times, but they have grown rarer. This was one of the last: I do not say the last. And so they fell, or rose, or blundered, or dropped right through, and found themselves in this world, in the Land of Telmar which was then unpeopled." (Prince Caspian, chapter 15: Aslan Makes a Door in the Air)

Nowadays, we would say Caspian is Polynesian.

The Silver Chair features "the King's son of Narnia, Rilian, the only child of Caspian, Tenth of that name" (The Silver Chair, chapter 12: The Queen of Underland"). One of the protagonists of The Last Battle is Tirian, whose "great-grandfather's great-grandfather" was Rilian. Like Caspian, they are heroes and kings, and Telmarines of Polynesian descent. Caspian and Rilian had such golden reigns that Tirian remembers them, and specifics of their stories, hundreds of years later (The Last Battle, chapter 9: What Happened That Night).

Calormen is a large kingdom to the south of Narnia. While its origins are never given, both the text and the original illustrations (by Pauline Baynes, with input and approval from Lewis), clearly show it is based on the Middle East; its citizens are described as dark-skinned. Tarkheena is a Calormene title, the feminine version of Tarkaan, meaning "great lord", while Tisroc is the Calormene equivalent of king or emperor (The Horse and His Boy, chapter 1, How Shasta Set Out On His Travels).

One of the protagonists of The Horse and His Boy is "Aravis Tarkheena ... the only daughter of Kidrash Tarkaan, the son of Rishti Tarkaan, the son of Kidrash Tarkaan, the son of Ilsombreh Tisroc, the son of Ardeeb Tisroc who was descended in a right line from the god Tash. [Her] father is lord of the province of Calavar and is one who has the right of standing on his feet in his shoes before the face of the Tisroc himself (may he live for ever)" (The Horse and His Boy, chapter 3: At the Gates of Tashbaan). In the book, Aravis is brave, quick-thinking, and independent, with a strong character arc based around pride and generosity without ever losing her fierce spirit; afterwards, she marries another protagonist, Prince Cor, "and after King Lune's death they made a good King and Queen of Archenland and Ram the Great, the most famous of all the kings of Archenland, was their son" (The Horse and His Boy, chapter 15: Rabadash the Ridiculous).

Lasaraleen Tarkheena plays a supporting role in The Horse and His Boy. Aravis's friend, she is earnest, friendly, and loyal, risking herself to help Aravis even when she can't see the appeal in Aravis's chosen life. (The Horse and His Boy, chapter 7: Aravis in Tashbaan; chapter 9: Across the Desert)

Emeth is a minor character in The Last Battle. A Calormene officer, he is brave, pious, and honorable; he is also courteous, well-spoken, and learned, quoting "the poets" (The Last Battle, chapter 10: Who Will Go Into the Stable; chapter 14: Night Falls on Narnia; chapter 15: Further Up and Further In).

As for other characters, there is very little in the books indicating they are of one ethnicity or another. Cor is explicitly stated to be "white and fair", because he has to be; it is a plot point (The Horse and His Boy, chapter 1: How Shasta Set Out on His Travels). Jadis is repeatedly described as very pale as a way to indicate how strange and otherworldly she looks (The Magician's Nephew, chapter 13: An Unexpected Meeting; The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, chapter 3: Edmund and the Wardrobe). Many characters have minimal or no physical description. Lewis's writing style leaves a great deal to imagination; a clear image of all the characters simply cannot be formed from textual evidence alone.

What can be said is that a truly book-accurate adaptation of Narnia, as envisioned by C. S. Lewis, will have a diverse cast.

#the chronicles of narnia#narnia#tcon#narflix#netflix narnia#caspian the tenth#caspian x#prince caspian#rilian#rilian (narnia)#tirian#tirian (narnia)#aravis tarkheena#lasaraleen tarkheena#emeth#emeth (narnia)#diversity#nova actually posts stuff#i should hope a movie made in 2025 manages to be at least as diverse as books written 70 years ago#some of the writing around poc in the narnia books does not hold up but that does not change the fact#that if you removed every character of color you'd lose half the cast

48 notes

·

View notes