#patrick leigh fermor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Live, don't know how long, And die, don't know when; Must go, don't know where; I am astonished I am so cheerful.

- Patrick Leigh Fermor, Between the Woods and the Water

#fermor#patrick leigh fermor#quote#poem#literature#writer#author#travel#traveller#explorer#exploration#wanderlust#british#icons

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patrick Leigh Fermor

These summer nights are short. Going to bed before midnight is unthinkable and talk, wine, moonlight and the warm air are often in league to defer it one, two or three hours more. It seems only a moment after falling asleep out of doors that dawn touches one gently on the shoulder, and, completely refreshed, up one gets, or creeps into the shade or indoors for another luxurious couple of hours. The afternoon is the time for real sleep: into the abyss one goes to emerge when the colours begin to revive and the world to breathe again about five o'clock, ready once more for the rigours and pleasures of late afternoon, the evening, and the night.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summary: In 1933, young Patrick Leigh Fermor began walking from the Netherlands to Constantinople, his journey taking him through the heart of Europe during the last days before WWII.

Quote: “The notion that I had walked twelve hundred miles since Rotterdam filled me with a legitimate feeling of something achieved. But why should the thought that nobody knew where I was, as though I were in flight from bloodhounds or from worshipping corybants bent on dismemberment, generate such a feeling of triumph? It always did.”

My rating: 4.0/5.0 Goodreads: 4.06/5.0

Review: It takes some time to get immersed in the dense but lovely prose of Fermor’s reminiscences, but it is time worth spending. Fermor is charming and full of wonder, his observations covering his natural surroundings and the people he encounters are poignant and unpretentious. He journeys to parts of Europe I’ve never heard of, but am now totally in love with. As it’s a retrospective memoir, there’s also a bittersweet nostalgia for a version of Europe that has been lost forever. This short volume only takes Fermor as far as Hungary—it takes another two for him to finish his journey—but I’m not sure that I’ll read the sequels. This volume feels perfectly complete on its own.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Time of Gifts

A Time of Gifts—Patrick Leigh Fermor’s classic travel book takes you to a lost world, and a lost time. New post on Around The Edges.

Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts was published in 1977, more than 40 years after the events it describes, and after Leigh Fermor had published a lot of other travel books. It tells the story of a walk across Europe as a teenager, starting just before Xmas 1933, from Rotterdam to Constantinople, as it was called then. (It takes two more books to get all the way to Constantinople). It’s a…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camminando fra i boschi e l’acqua: Un viaggio a piedi in Europa sulle tracce di Patrick Leigh Fermor. Recensione di Alessandria today

Da Hoek van Holland al Corno d'Oro, un cammino alla scoperta dell'Europa e della sua anima profonda, narrato da Nick Hunt

Da Hoek van Holland al Corno d’Oro, un cammino alla scoperta dell’Europa e della sua anima profonda, narrato da Nick Hunt. Camminando fra i boschi e l’acqua di Nick Hunt è un libro di viaggio che rievoca l’impresa del leggendario viaggiatore Patrick Leigh Fermor, il quale attraversò l’Europa negli anni ’30. Settant’anni dopo, Hunt decide di ripercorrere lo stesso itinerario, partendo da Hoek van…

#Viaggio interiore#Camminando fra i boschi e l’acqua#cammino attraverso l’Europa#Corno d&039;Oro#cultura europea#Esperienze di viaggio#esplorazione a piedi#esplorazione culturale#Europa orientale#Hoek van Holland#identità europea#Incontri culturali#Istanbul#itinerario storico#leggende di viaggio#Libri di Viaggio#libro su Patrick Leigh Fermor#libro sul viaggio a piedi#libro sulla cultura europea#narrativa di esplorazione#narrativa di viaggio#natura e avventura#Neri Pozza#Nick Hunt#paesaggi europei#Patrick Leigh Fermor#riflessioni personali.#riflessioni sul viaggio#Stile poetico#storie di viaggio

0 notes

Text

Book Review

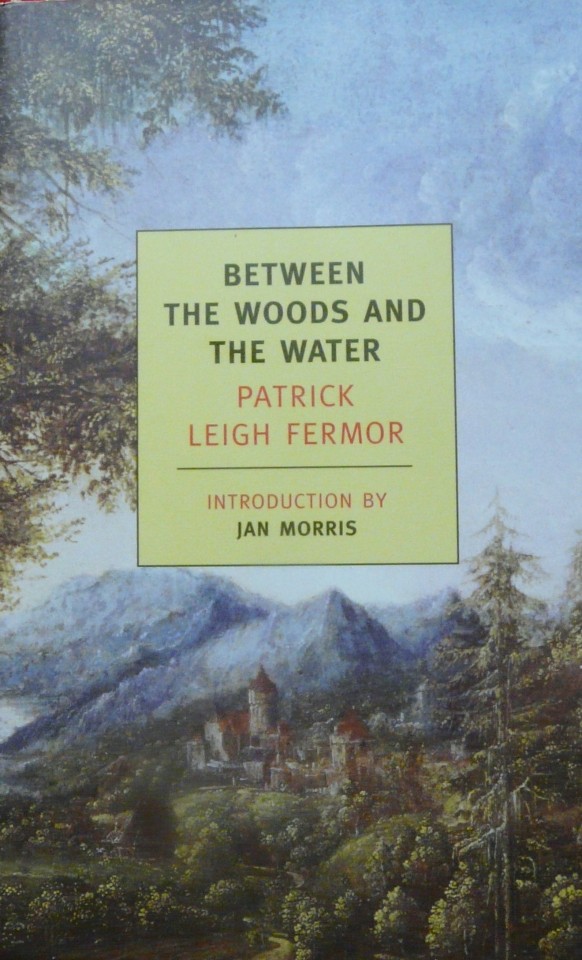

Between the Woods and the Water by Patrick Leigh Fermor

Patrick Leigh Fermor was an English college dropout who walked across Europe between the two world wars and wrote a trilogy of books about the experience. The first volume, A Time of Gifts, was poorly written and often a chore to read although it did pick up momentum in the second half of the book. The second volume, Between the Woods and the Water, is a vast improvement.

Leigh Fermor begins this book by crossing the Danube River from Slovakia into Hungary. He is immediately greeted with warm welcomes and taken to a procession and celebratory mass in a Catholic church for the end of Lent. He proceeds on to Budapest, has an amazing time, and moves on to hike across the Great Hungarian Plain, the western most steppe of that geographical feature spreading all the way to Mongolia. He continues to have interesting encounters with the country folk and even spends a night with a camp of Romani people. Despite all he has heard about their criminal tendencies, the night passes without incident to his pleasant surprise. As he gets closer to the border with Romania, he starts staying in upper class villas owned by people he made contact with during his previous travels. What is great about this whole section is the vivid description of the landscape, something that he improves on as he goes farther along. His portrayal of the upper classes, as well as the other people he meets, is of higher quality too. Maybe Hungarians are just more exciting people than the Germans he writes about in the previous volume, but they are more interesting and lively in these chapters than anything he had written before.

One interesting part of his journey through Hungary is the intellectual curiosity and passion for reading that Leigh Fermor shows while he stays with the Hungarian aristocrats. One thing he does when he visits them is read the books they have collected in their personal libraries. Some of the weakest and most muddled passages of A Time of Gifts are those where he struggles to explain historical events from the places he visits. It is some seriously bad writing, but here in Between the Woods and the Water he does a far better job of explaining with clarity all the entanglements of people who either migrated to Hungary, traveled through it, or tried to conquer it. This is tough subject matter including tribes of Avars and Goths, later settlements by Huns and Magyars, invasions by Mongols, Germans, and Ottoman Turks, and eventual collaboration with the Habsburg kingdom. He makes some sharp observations about the Magyar language too. His ability to comprehend and describe the syntaxes of all the languages he encounters while traveling is impressive even if he never fully masters the complexities of Magyar. Being able to explain what an agglutinative language is is good enough.

As Leigh Fermor continues into Romania, he keeps calling on contacts he made through others he met in Hungary. His original plans to sleep in forests, fields, and farms gets scrapped as he continuously gets invited into the homes of aristocrats, living a high and leisurely life with them. They enjoy his company so much that their hospitality seems to be without end. The downside of this is that as he travels southwards into Transylvania, most of the people he associates with are ethnic Hungarians and Swabians, but he encounters far fewer Romanians. Transylvania was formerly part of Hungary and Romania incorporated it into their country when the Habsburg Empire broke up after World War I. The author is acutely aware of the tensions between the two groups as, yet he continuously maintains optimism in the possibility of them all uniting under the banner of one nation despite their separate identities.

Socially speaking, he spends a lot of time with an interesting character named Istvan who takes him on a series of adventures. One interesting part is when the two are swimming nude in a river and two farm girls see them, taunt them, and encourage them to chase after them where something or other happens behind a hay rick. What happens there is left to your imagination, but if it involves two naked men it shouldn’t be hard to figure out. Istvan also takes Leigh Fermor and Angela, a married woman from Budapest, on a car ride around the western edge of Transylvania. Leigh Fermor and Angela are having a fling and Istvan wants to make sure they are out of the sight of nosy neighbors who won’t mind their own business. Along the way, the author continues to expound his knowledge about Romanian history as they visit castle ruins in the mountains. He clearly informs his readers about the lives of John Hunyadi and Vlad Tepes, the count who inspired Bram Stoker to write Dracula.

Leigh Fermor then goes off on foot again, trekking through the western edge of Transylvania along the Mures River, connecting again later with the Danube before crossing over into Bulgaria. His descriptions of the mountains are incredible. He uses language to capture the weather, the running water, the plants, the trees, the sounds, the mist,and various other people he meets along the way. Some of the best descriptive writing involves animals; he wakes up one morning to look over a cliff where he sees a golden eagle stretch its wings before taking off in flight, being joined by another eagle. This passage is magnificent.

There isn’t much to dislike about this book. Not all of the writing is perfect, but there are so many more high points in comparison to the first volume of this trilogy that the low points ca be easily overlooked. It is interesting to see how the author’s literary skills grow before your eyes as he continues to write. It also helps that Hungary and Romania are far more interesting countries than Germany or Austria where the author traveled in A Time of Gifts.

Between the Woods and the Water is an exciting travelogue and work of descriptive prose. In it, we see where Patrick Leigh Fermor improves on all the problems he had in the previous book and watching this process of growth unfold is one of this book’s charms. The author is a Romantic at heart and by that I refer specifically to the Romantic movement that preceded the Victorian literary style. But Patrick Leigh Fermor’s Romanticism is a little different; he has the sublimity of nature, the castle ruins, the passage of time, and the push towards transcendence, but at the young age of nineteen, he is too young to wallow in a hopeless longing for the past and the melancholia that the Romantic poets insisted on indulging in. He travels and writes in the here and now as if he loves every minute of it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Me: *logs on to tumblr to see what’s going on*

Tumblr dash: Here’s Jared Leto in a giant fucking cat suit.

Me:

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lucas van Valckenborch (1535-1597) Winter landscape (January or February) 1586. Detail, oil on canvas.

Patrick Leigh Fermor on walking through Germany in the 1930's:

"Vague speculation thrives in weather like this. The world is muffled in white, motor-roads and telegraph-poles vanish, a few castles appear in the middle distance; everything slips back hundreds of years. The details of the landscape - the leafless trees, the sheds, the church towers, the birds and the animals, the sledges and the woodmen, the sliced ricks and the occasional cowmen driving a floundering herd from barn to barn - all these stand out dark in isolation against the snow, distinct and momentous. Objects expand or shrink and the change makes the scenery resemble early woodcuts of winter husbandry. Sometimes the landscape moves it further back in time. Pictures from illuminated manuscripts take shape; they become the scenes which old brevaries and Books of Hours enclosed in the O of Orate, fratres. The snow falls; it is Carolingian weather…"

From A Time of Gifts, 1977.

#this saddens and worries me to no end#those medieval times were still within the imagination horizon of Patrick Leigh Fermor#he could grasp back in time via the unbroken connection of similar winter weather circumstances#but that connection to those earlier times is lost to me#because that kind of winter won't be seen on this planet anymore until maybe far after the end of humanity as a species#which unmoors me in the same way as the hapless scientists circling the planet Solaris in Tarkovsky's movie#looking at that Bruegel winter painting#longing for an earth that is forever out of reach

0 notes

Note

I must have missed it recently but from a post I read yesterday I think you have you left your position and are moving? Or is this something that happens often in your line of work?

Dear Position Anon,

When you are a diplomat, you must also be ready to change places on the regular. Staying indefinitely in a country is not really encouraged, as the longer you stay, the more biased or blasé you can become: it's called 'going native' (I know, that's an idiom, nothing more).

Before the Industrial Revolution, the world was a much bigger place than now. People like Ruy González de Clavijo were not expected to return anytime soon to Madrid, from his embassy to Tamerlane, in 1403. Others were posted for life to Venice, to Versailles or to Munich, especially from the Renaissance and until the Congress of Vienna, in 1815. But this (bad) habit was gradually abandoned, thank God!

Five years and a half spent here are more than enough, even if I will always feel like three of them were robbed by COVID (and, unlike many other colleagues, I did go on holiday in the islands in 2020, because otherwise my brain would have burst). Anyways, all this time flies by in a jiffy.

Where next? I wish I knew and, despite the general fantasy, you never get to choose the where and when. Also, you are rarely sent to familiar places and stepping into the unknown is one of the greatest appeals of this job, to me. Until then, I am homeward bound, for a while. That is a much, much needed decompression chamber moment.

I will always, always come back to this view, Anon, but I prefer to do it without the extra daily life pressure, to be honest. This is a lazy summer evening in Kardamyli, in the sublime Mani Peninsula, a place Patrick Leigh Fermor never left:

Taken by me, in 2021. As for the rest, I'll keep you posted. I am ready to say good-bye. Farewell? Never.

103 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Dickensian Bookshop

Each time I pass through this small town I try to spend some time at the Dickensian Bookshop, one of my favourite second hand booksellers.

As I approached the store I saw an old man (not the guy in my photo) clinging to a Give Way sign across the street.

I browsed the shop window display and didn’t need to look to know that he would be closing in on me. I’m a magnet for the unusual.

When I did look up he was a metre away and intense with energy. I looked into him but I didn’t sense any malice, at least not for me.

“I’m looking for HOODS!” he said. He pronounced the word hoods with considerably more emphasis than the rest of the sentence, which I found interesting.

In this once English colony, the word hood is easily recognised as a variant of hoodlum. It’s just that we stopped using the words hood and hoodlum a long time ago.

Anyway, I’ve found from my experience with interesting people that mirroring is comforting for them.

“HOODS?” I yelled back at him.

“Yes, HOODS! I’m looking to rough me up some HOODS!”

“Rough me up” of course means to hit and otherwise treat roughly, people in need of ill treatment. In this context, HOODS.

“Well I’m sure you’ll find plenty of HOODS in this town.” I said.

I could see that this was new information for him and also, that I was probably the most agreeable person he’d met recently.

He considered things for a moment, his clenched fists churning in a low ready position, as if remembering what it was like to be a boxer from a long time ago, and then suddenly, he went blank.

With the right equipment I could probably have shown you the exact place in his brain where a tangle of malignant protein was blocking the vital connection to the spot where he had saved those memories of his youth as a boxing man.

Instead, I took his cerebral misfire as an opportunity to gracefully slip into the bookstore and I closed the door deliberately behind me. I didn’t want to discover, upon his reanimation, that I now looked like a hoodlum to him.

“He’s looking for hoods.” I said to the lovely person behind the little desk by the door.

“Oh dear. I saw him hanging onto a sign over there.” and they motioned vaguely with their head. “I hope he’s okay.”

“I think he has dementia. He’s quite hunched and kind of shuffles when he walks but it doesn’t feel too bad yet. I mean, I don’t think he’s lost or anything and ... I didn’t sense any fear in him.”

I spent 20 minutes in this wonderful bookstore, in the midst of this wonderful life and grateful that it was not yet my turn to cling to signs.

I bought a biography of Patrick Leigh Fermor, a book of photographs by the painter Alphonse Mucha and the graphic novel/anthology American Splendor - The Life and Times of Harvey Pekar.

Of course, none of this ends well for us. I watched one of my best friends die in mortal fear and my father suffered panic attacks as his end drew near. I hope to be brave, I hope to laugh in the face of death and, if given the opportunity, I hope also to cling to many signs, in particular, those that instruct me to Give Way and to Yield.

- One Kindred Spirit

Silver Print

#silver gelatin#original photography#original words#film photography#secondhand bookshops#darkroom#photographers on tumblr#original writing#monochrome#black and white

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

'They are wild and shy and not accustomed to talk.' He pointed straight up into the air. The canyon was closing round us. 'They see nothing but God.'

Patrick Leigh Fermor, Mani

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I first read Fermor's book on walking to Constantinople.

‘Pimpernel of the Hellenes’, ‘Major Paddy’, ‘Enchanted maniac’: Will the real Paddy Leigh Fermor please stand up?

Paradox reconciles all contradictions. - Patrick Leigh Fermor

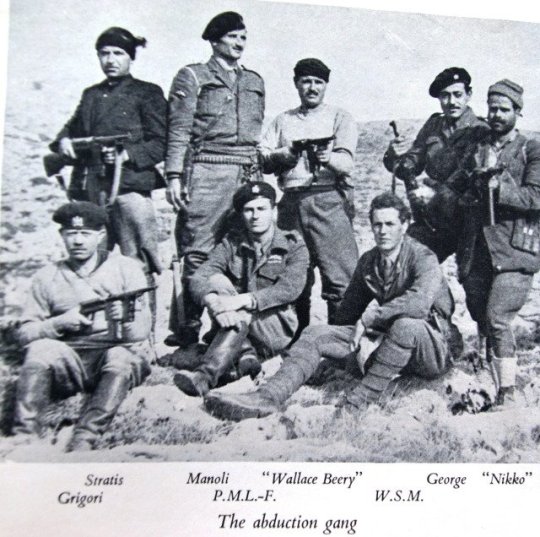

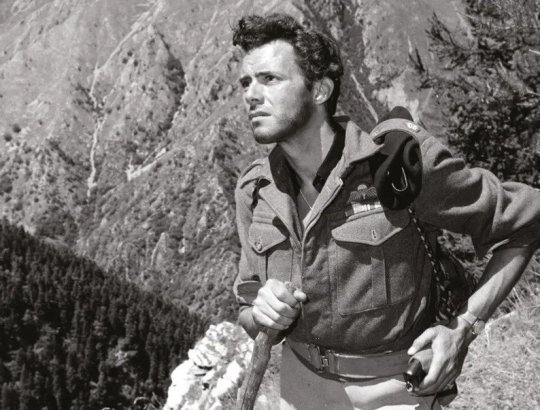

So one evening I was baby sitting my nephews and nieces here in our family chalet in Verbier, high up in the Swiss Alps. It was my turn to baby sit as the rest of my family enjoyed the fantastic classical music concerts and events showcased at the two week long Verbier 30th Festival. The little scamps had gone to bed and my father and I watched an old British war movie on DVD, ‘Ill Met By Moonlight’ (1957). It was filmed by the legendary team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger based on the 1950 book ‘Ill Met by Moonlight: The Abduction of General Kreipe’ by W. Stanley Moss.

I’ve seen the film a couple of times before, but until now never really paid attention to where the title came from. My father said it was from Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream’ And so it was. In the play, Oberon, the king of the fairies and the Queen are having a fairly bitter drawn-out fight over custody of a changeling Indian child, and this is how the pissed off king greets the queen when they run into each other, “Ill met by moonlight, proud Titania”. Oberon is basically saying “Oh Lord, it’s you…” and Titania’s response is basically a flippant middle finger. One of the best modern reasons to read Shakespeare: to throw playful erudite shade at others.

Anyway, the historical background of the film is the German invasion of Crete in May 1941. After an intense ten-day battle, Allied troops were driven back across the island, and many were evacuated from beaches along the southern coast. Some Cretans and British officers took to the mountains to organise resistance against the occupying forces. The German occupation that followed was especially brutal. Dreadful reprisals followed every act of resistance. The German commander, General Müller, insisted on taking 50 Cretan lives for every German soldier killed; he became known as ‘The Butcher of Crete’.

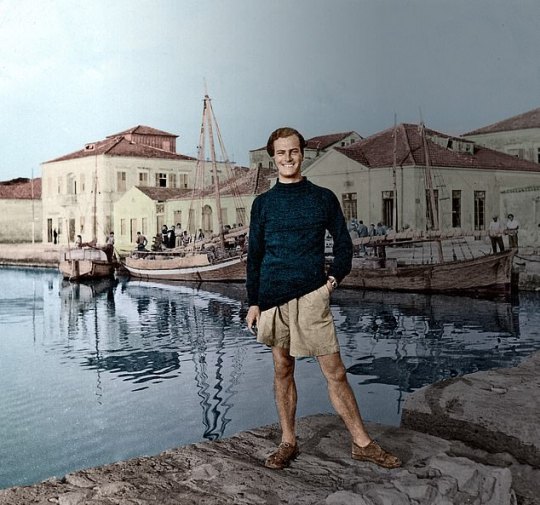

As a Classicist side note, there had been a close association between Britain and Crete since the early 20th century, when archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans had uncovered the sensational remains of a Minoan palace at Knossos. The headquarters of the British archaeological school in Crete was a large villa alongside the site, known as Villa Ariadne. Several archaeologists, who knew the island and its people well, went underground after the German occupation to aid the Cretan resistance. Continuing in this tradition, scholar and travel-writer Patrick Leigh Fermor, who had got to know Greece in the 1930s, joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

During the German occupation, Major Paddy Leigh Fermor travelled to Crete three times to help organise local resistance against the hated German occupation. On the third occasion, in February 1944, he was parachuted in with a specific mission to kidnap German commander General Müller, to boost morale on Crete along with his erstwhile SOE comrade Capt. W. Stanley Moss MC (aka Billy Moss) of the Coldstream Guards. However, just after they parachute in, General Müller was replaced by General Heinrich Kreipe, who transferred from the Russian Front. Thinking that capturing one general was as good as another, Fermor merrily go ahead with the daring kidnap operation.

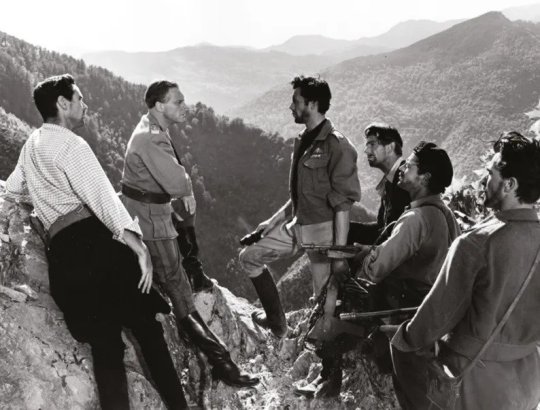

It’s at this point that the narrative of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s ‘Ill Met by Moonlight’ (1957) picks up. Dirk Bogarde plays Paddy Leigh Fermor, David Oxley plays Moss, and Marius Goring plays the taciturn German paratroop general. Blink and you’ll miss the late great Christopher Lee making a cameo appearance as a German officer in the dentist’s room scene.

The film naturally takes some liberty with the facts but it’s a cracking yarn of high adventure and drama. Xan Fielding, a close friend of Leigh Fermor from the SOE in Cairo, was taken on as technical adviser. The fact the film was shot in in the Alpes-Maritimes in France and Italy, and on the Côte d'Azur in France, far away from the craggy valleys and mountains of Crete itself. The director Michael Powell spent some time walking in Crete to get to know the island, but decided that, with the confused and volatile state of Greek politics, it was not suitable to film there.

Looking back years after he had directed it Powell didn’t think much of his own film. By contrast, Paddy Leigh Fermor, who was on set throughout the film shoot, was very happy with Bogarde’s portrayal of him with Byronic glamour. Watching the movie again ‘Ill Met by Moonlight’ remains a classic and stands out from many British war films of the 1950s because of its realism. The British SOE men and the Cretan guerrillas look absolutely right for their parts. It is dramatic and full of suspense while filled with much boyish humour.

I was disappointed with one notable omission in the film that did happen in real life. According to Patrick Leigh Fermor, at dawn one day during the journey across the mountains, General Kreipe was looking at the mist rising from Mount Ida and began to recite, in Latin, the opening lines of Horace’s ninth ode:

Vides ut alta stet nive candidum Soracte nec iam sustineant onus silvae laborantes geluque flumina constiterint acuto?

Behold yon Mountains hoary height, Made higher with new Mounts of Snow; Again behold the Winters weight Oppress the lab’ring Woods below: And Streams, with Icy fetters bound, Benum’d and crampt to solid Ground

(John Dryden 1685)

Leigh Fermor picked up on the General, and recited the remaining stanzas of the Ode. ‘Ach so, Herr Major,’ said Kreipe when Leigh Fermor had finished. Both men were amazed to realise they shared a classical education and a love of ancient Latin poetry.

Leigh Fermor later wrote that it was as though the war had ceased to exist for a moment, as ‘We had both drunk from the same fountains before.’ It brought captor and captive together with a strange bond. The scene was not reproduced in the film, as Powell and Pressburger probably thought it would make the men sound too academic for a popular cinema audience.

Leigh Fermor and Kreipe met again in the early 1970s, on a Greek television show, and got on famously together. The General said Leigh Fermor had treated him chivalrously as a captive. They remained friends until Kreipe’s death.

After sharing a late night drink with my father after the film, I began to muse on the figure of Paddy Leigh Fermor, a family friend and someone I met along with his wife, Joan, as a little girl. My grandparents, and especially my grandmother, knew Paddy briefly from their days during and after the Second World War.

My father shared a few stories about him when he and my mother visited his beautiful home in Greece, where even at his advanced age he remained the most generous of hosts and the most outrageous flirt.

One of my memories was getting into his battered old Peugeot in the drive way and trying to drive it when my feet could barely touch the pedals. It wouldn’t have mattered in any case as the brakes didn’t work as he cheerfully said later as we careened around a dirt road to go around the mountains for a drive.

Many years later in April 2022, I tried to visit the home of the late Patrick and Joan Leigh Fermor - a sort of pristine shrine to their memory that one can also stay in any of the rooms as a vacation rental - in the coastal fishing village of Kadarmyli in the Peloponnese, as part of a hiking and mountaineering sojourn around Greece with ex-Army friends. We couldn’t stay there as it was already rented out to other guests, and so we stayed higher up the mountain in a villa, but we swam in front of the Fermor’s home which was on the water’s edge.

You could never put your finger on Paddy Leigh Fermor. He hid behind his gift for telling yarns, and pulling Ancient Greek verses out of the thin air, as well as boisterously singing local Greek songs with a drink in his hand.

Even after his death in 2011, the question keeps nagging as to who was Paddy Leigh Fermor?

Keep reading

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

not feeling great but trying to take care of myself with soup and vitamins and all the other illnes attributes. started patrick leigh fermor's a time of gifts which i bought in a tiny book shop on amorgos last summer but hadn't read yet. it's beautifully written! what a jewel. i think this is going to be a new favourite.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books read in 2024

What if? 2 by Randall Munroe

The Culture Map by Erin Meyer

1984 by George Orwell

Being a Beast by Charles Foster

Das Leben ist kurz by Jostein Gaarder

Beowulf by Maria Dahvana Headley

Erebus by Michael Palin

Rooted by Sarah Langford

The Flow by Amy-Jane Beer

Changes in the Land by William Cronon

Wendy, Darling by A.C.Wise

How to Blow Up a Pipeline by Andreas Malm

Tough Women Adventure Stories Edited by Jenny Tough

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

Frankenstein by Mary Shelly

Surrounded by idiots

A Woman looking at men looking at women by Siri Huvstedt

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

Das Recht auf Faulheit by Paul Lafargue

Gebrauchsanweisung für Häuser

Know This by John Brockman

Roumeli by Patrick Leigh Fermor

The Quiet Moon by Kevin Parr

Rewild Yourself by Simon Barnes

Calling Bullshit by Bergstrom and West

Patrick Leigh Fermor by Artemis Cooper

A far cry from Kensington by Muriel Spark

A Disorder peculiar to the country

Sleep Smarter by Shawn Stevenson

Before Scotland by Alstair Moffat

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The slow fall of the evening among this smashed and shattered masonry, the decrescendo and then the silence of the cicadas, the wide unruffled gleam of the sea below and the nerve-stilling quietness of the air, hold a different message. A spell of peace lives in the ruins of ancient Greek temples. As the traveller leans back among the fallen capitals and allows the hours to pass, it empties the mind of troubling thoughts and anxieties and slowly refills it, like a vessel that has been drained and scoured, with a quiet ecstasy. Nearly all that has happened fades to a limbo of shadows and insignificance and is painlessly replaced by an intimation of radiance, simplicity and calm which unties all knots and solves all riddles and seems to murmur a benevolent and unimperious suggestion that the whole of life, if it were allowed to unfold without hindrance or compulsion or search for alien solutions, might be limitlessly happy.

[Patrick Leigh Fermor, Mani]

0 notes