#parmenide

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Gloria al Padre...

"Il nulla non esiste", "il nulla non può esistere in alcun modo": è questa intuizione il fondamento del pensiero di Parmenide. Perciò l'unico discorso vero è quello che dice che "qualcosa è", e di conseguenza che "il tutto di questi qualcosa è". Se Cartesio avesse affermato "penso, perciò quello che chiamo il mio sé è" sarebbe arrivato alla medesima conclusione: "tutto ciò che appare è".

Il mutamento appare, anzi appare incessantemente. Ma non vuol dire che tutto ciò che è si stia svolgendo, perché, per esserci uno svolgimento, il presente avrebbe dovuto essere nulla, prima di apparirci presente. E dovrebbe finire nel nulla, per far posto all'apparire di un altro presente. Il mutamento, quindi, è incessante, ma nel suo complesso, nella sua immensa totalità, è immutabile. Il tempo appare, ma la totalità del tempo è eterna, esistendo tutta per intero. E nessun presente sì è mai svolto una prima volta. Infatti questa totalità dell'apparire è il sé del dio del cosmo, il sé dell'uno e del continuo, che non si è mai svolto né è mai divenuto, ma che torna incessantemente presente, cioè eternamente ad apparirsi, non solo perché è, ma anche perché senza alcuna discontinuità è. L'eterno riapparirsi di tutti gli apparire perciò non ne è lo svolgimento, ma ne è ciò che un tempo chiamavamo "la gloria".

(Omaggio a Emanuele Severino - di Gulcan Oruc)

#essere#divenire#parmenide#emanuele severino#spazio#tempo#nulla#gloria#natura della realtà#fisica quantistica#regno dei cieli#eternità

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parmenide e Zenone

Il terribile Parmenide che dal suo promontorio di Capo Palinuro osservò il vasto mare colore del vino ed ebbe l'illuminazione: l'essere è, il non-essere non è. Se il nulla non è, cioè non esiste per sua stessa definizione, tutto è costretto dalla legge del logos a permanere in eterno, immutabile, incorruttibile, e il divenire del mondo è soltanto un'opinione senza fondamento. L'essere è per Parmenide quella sfera ben rotonda in cui ogni ente è da sempre salvo e conservato stabilmente presso totalità delle cose che sono e non possono smettere di essere. È la ragione che indica la verità, non i sensi, che invece ci garantiscono un sapere solo soggettivo.

A difendere e diffondere le controverse tesi del maestro intervenne l'allievo Zenone (Zenone di Elea, da non confondersi con Zenone di Cizio, fondatore dello stoicismo) il quale divenne celebre per i suoi paradossi. Un primo paradosso è quello del bastone che ipoteticamente si può spezzare a metà all'infinito, sicché alla fine si riduce a un niente, questo per dimostrare l'illusorietà della consistenza della materia. Un altro paradosso è quello della freccia che viene scoccata e nel suo tragitto deve attraversare una serie infinita di fotogrammi e di stati immobili, fino a non raggiungere mai il suo bersaglio, sicché se ne deduce che il movimento è illusorio pure lui, e di conseguenza anche ogni cambiamento apparente degli stati del mondo.

Questi argomenti, detti della scuola eleatica, diedero del filo da torcere ai pensatori successivi che ce la misero tutta a dimostrare che invece la vera evidenza è il divenire, che è poi il leitmotiv di tutta la filosofia occidentale: la certezza del mutamento come creazione e distruzione dell'ente, che la scuola eleatica aveva deciso invece di negare così radicalmente per via razionale.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sacred Obscurity embodies that primordial light unapproachable, in which the divine essence, though profoundly veiled, resides manifestly with God. It is within this realm where the interplay of concealment and unconcealment unfolds, revealing the truth of Being in its most enigmatic and unattainable form. This light, though forever beyond the reach of human grasp, illuminates the divine dwelling as a site of the ultimate mystery, where God exists in the purest state of disclosed hiddenness. Here, in the radiant darkness, the foundational nature of truth as aletheia—unconcealed yet perpetually concealed—manifests itself, inviting those who approach to ponder the profound depths of existence and non-existence intertwined.

Dionysius the Areopagite: On the Divine Names (Heidegger Parmenides Narration)

44 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I will tell you which are the only routes of inquiry for thinking: the one, that which is and which it is not possible for it not to be, is the path of persuasion (for it attends upon truth), the other, that which is not and which it is right that it not be, this indeed I declare to you to be a path entirely unable to be investigated: for neither can you know what is not, nor can you say it.

Parmenides, Fragments, B2

#philosophy#quotes#Parmenides#Fragments#inquiry#investigation#necessary#truth#reason#being#nothingness

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

22. The Illusion of Trust: Decoding the Broken Bonds of a Widely Fractured Society

“It is right that you learn all things — both the unshaken heart of well-rounded truth and the beliefs of mortals, in which there is no true trust.” — Parmenides

In a world rife with superficial relationships and digital interactions, trust has become a currency that is both devalued and yet relentlessly sought after. This paradox creates an unsettling backdrop wherein individuals often mistake the vibrations of social media engagement for genuine connection. What is deemed “likeable” often outweighs what is “trustworthy,” leading to a collective condition where the heart of truth is obscured by the smoke and mirrors of curated online personas. One might argue that as modern society embraces the fleeting dopamine hit provided by attention, it simultaneously compromises the very essence of trust itself.

Authenticity, in its purest form, is rapidly becoming an elusive aspiration. Individuals engage in a dance of façade-building, projecting idealized versions of themselves that are far removed from reality. This self-betrayal extends beyond personal identity into relational exchanges, breeding a climate of codependency. Rather than forging genuine connections, individuals become entangled in webs of emotional manipulation and parasitism—using one another as means to end. The moral ramifications of such behavior create ripples that undermine the foundational ethos required for healthy, fulfilling relationships.

Amidst these dynamics, we must ask: What does it mean to trust in a world where vehement likes eclipse heartfelt conversations? The delicate weave of trust is frayed by fleeting validations that occur at the speed of a thumb swipe. Amid the echoes of endless notifications, the quest for authenticity often finds itself buried beneath layers of curated commentary and attentiveness that serve selfish ends. The gravity of these choices stretches our understanding of interpersonal agency, raising profound questions that challenge our very conception of morality and connection.

Paradoxically, the price of this social currency is steep; it demands the sacrifice of depth for breadth. In an age where every interaction is structured to serve the fickleness of engagement metrics, the more profound human experience—characterized by vulnerability, reciprocity, and, fundamentally, trust—stands endangered. As we deconstruct the intricate ties that bind us, it becomes imperative to reassess not only our motivations for engagement but also the ethical frameworks that sustain our relationships amid chaos.

The Currency of Connection: Emotional Dependency and Social Parasitism

As Parmenides reminds us, the beliefs of mortals are often steeped in treachery rather than truth. The manifestations of emotional dependency in contemporary society reveal a troubling trend: humans are increasingly reliant on one another, not for authenticity, but for mere affirmation. This reliance is amplified through the dynamic of social media, where validation occurs at the cost of genuine connection. It is a paradox of modern life, where the abundance of voices drowns out the quiet power of meaningful discourse.

In this milieu, one must confront the uncomfortable reality of social parasitism—the phenomenon where individuals derive their sense of self-worth from the accomplishments and affection of others rather than fostering their own identity. Individuals become emotional leeches, thriving on the accolades initially designed to bolster communal trust. However, this destructive dependency ultimately erodes the very fabric of society, stranding individuals in a quagmire of unsustainable relationships and hollow connections that masquerade as fulfilling bonds.

Emotional dependency breeds a toxic environment wherein the intention behind interactions becomes muddied. As individuals align their worth with social media engagement, they inadvertently reinforce cycles of manipulation and disengagement. Such practices serve to attenuate the intricacies of ethical decision-making, prioritizing personal validation over collective responsibility. The foundation of mutual respect is undermined, giving way to relationships characterized by a transactional mindset, where emotional debts replace real connection.

To disentangle ourselves from this emotional mire, we must re-establish a hierarchy of values that prioritize depth over superficiality. Authentic connections must revolve around more than mere acknowledgment; they must root themselves in a shared commitment to truth and vulnerability. As social currency continues to proliferate, so too must our defiance against the corrosive impact of emotional parasitism, which threatens not only our relationships but the very essence of humanity itself.

Deconstructing the Ethics of Engagement

The landscape of moral engagement is fraught with ambiguity. Trust, once the cornerstone of productive relationships, now teeters on a precipice of peril, challenged by the fragmented narratives that populate social media. In this kaleidoscope of opinions, the individual voice often becomes an empty whisper devoid of moral grounding. In a world where every tweet and post serves as both a weapon and shield, the ethical dimensions underlying our engagements fall victim to the whims of societal approval.

In tracing the contours of ethical betrayal, we must confront our role as actors within this dynamic. Each user is an architect of their digital identity, wielding the power to shape their perceptions and, by extension, influence others. However, the clash between genuine engagement and performance raises a new dilemma that demand both introspection and accountability. Are we crafting honest-hearted narratives with integrity, or are we merely participating in a tragic masquerade designed to satiate a hungering and insatiable audience?

To build a restoration of trust, it becomes paramount to reevaluate our incentives for engagement. As the boundaries between virtual interactions and tangible relationships continue to blur, the ethical implications of our choices carve marks into the social psyche. Every engagement bears the weight of intention, summoning us to reflect—are we there to uplift our fellow users or are we doing so merely to preserve our status? Amid this reckoning, it becomes increasingly evident that the loss of trust is a consequence of collective inaction as we falter under pressures to conform rather than embrace authenticity.

Rebuilding relationships calls for the courage to engage in uncomfortable conversations, the willingness to dismantle harmful patterns, and the strength to resist the palpable lure of superficial engagement. Only by courageously questioning our motives and the ethics underlying our interactions can we hope to regain the trust frayed by years of emotional neglect and social manipulation. Escaping the clutches of social media-induced isolation requires a steadfast commitment to fostering genuine connections born from realness, empathy, and transparency.

The Renaissance of Resilience: Redefining Trust in the Digital Age

In recognizing the deficiencies propagated by the viral age, we face the exciting challenge of redefining trust. This effort calls for a revival of resilience as a principle, wherein the reclamation of real human connection stands as a primary goal. Acknowledging the pervasive fragmentation necessitates a conscious divergence from the familiar patterns of codependency and emotional parasitism that have marred our collective experiences so far.

At the heart of this quest lies the recognition that we, as individuals, possess the power to effect change. By fostering emotional independence and resilience, we cultivate environments that prioritize authentic connections over hollow affirmations. Such a transformation germinates from collective introspection, where honesty becomes the cornerstone of our interactions, and the delineation between genuine engagement and superficial dialogue is sharply defined.

A call to resilience urges us to dismantle the external validation mechanism that has permeated our relationships. Trust should embody a principle that transcends individual engagement, spreading its roots into the fabric of societal ethics. Cultivating a climate of open communication and shared vulnerability becomes imperative in this transformation, ensuring that our relationships are not merely transactional engagements, but rather profound encounters that affirm our shared humanity.

As we navigate the tumultuous waters of trust in the digital age, we must champion a commitment to authenticity, instilling hope and renewal within the morass of emotional dependency. The path forward illuminates the potential for deeper relationships, urging us to cultivate an understanding of trust that transcends its superficial trappings. The arduous pursuit of this remarkable transformation demands immense strength; yet, in its wake lies the promise of reinstituted kinship founded upon cooperation, compassion, and collective resilience—a true renaissance of trust.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Trust as the Cornerstone of Meaningful Connections

As we reach the culmination of this discourse, it becomes evident that trust transcends mere abstraction; it stands as the essential force that fuels human connection. The disintegration of societal trust compels us to scrutinize our moral compasses, demanding unwavering introspection from both the individual and the collective. We must become acutely aware of our roles in perpetuating cycles of mistrust and ethical decline, while fervently striving to nurture authenticity in a world rife with superficiality.

The harsh truth of our present circumstances—a society plagued by codependency and social parasitism—necessitates a confrontation with our own complicity in this chaos. We are not merely observers; we are challenged to dismantle the walls that obstruct genuine connection. It is crucial to grasp that the cultivation of trust demands relentless effort, the audacity to embrace vulnerability, and a resolute commitment to mutual respect and accountability.

Ultimately, by reclaiming trust, we lay the foundation for relationships imbued with depth and meaning. In championing authentic connections while resisting the seductive lure of external validation, we awaken our potential for profoundly enriching interactions. As we embrace the path ahead, let us acknowledge the transformative potency of trust—an enduring force capable of bridging the divides that fracture us, empowering us to rise above the limitations imposed by social media and our own insecurities. We stand at a pivotal crossroads, where the imperative to restore trust and authenticity will shape the very essence of our future and the bonds we create within it.

#Parmenides#Trust#Truth#Connection#Codependency#Social Parasitism#Philosophy#writerscommunity#writers on tumblr

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I said "Plato was the Rúmil of Europe", and now my family is having a philosophical discussion of "which of them was first" (each of those two was before the other) and "therefore: time does not exist".

#we are all perfectly normal#now they discuss putting Parmenides on pasta#[makes the pasta immutable]#random#philosophy#[no not sir Palamedes it is a different guy]

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

sadelikte ne zaman haz bulacaksın?

marcus aurelius - meditations

#kitap#edebiyat#blogger#felsefe#kitaplar#blog#kitap kurdu#şiir#marcus aurelius#meditations#kendime düşünceler#stoa felsefesi#stoic felsefe#felsefe blog#lucius annaeus seneca#ahlak mektupları#stoa#stoic#sokrates#platon#sofist#kriton#menon#antik yunan#rabindranath tagore#epiktetos#epikuros#parmenides#herakleitos#friedrich nietzsche

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

What’s the significance of each color in Ancient Greece? So green is the only neutral color and it represents mostly natural and earthy things, thank you for telling me that part !! Anyway, as for my Hyacinthus design’s hair being brown, it’s due to the combination of it being a fairly common interpretation of his appearance and also because I find I like how it looks with his skin tone and the purple of his eyes.

Okay, firstly; thank you so much for answering my question too!

Admittedly you can't beat out good, old fashioned colour theory so that's completely fair haha! I still think it's very interesting that brown became the common interpretation of his features so I'm always glad to hear other people's view on it <3

With respect to what colours meant or symbolised in Ancient Greece, it's a super fascinating topic because the Ancient Greeks had a very different perception of colour than how a lot of people - and in this case I'll generalise and say english-speaking people - perceive colour. In a lot of languages, especially older ones, colour wasn't just a way to describe the physical perceptional reality of an observable object (that is, the light reflecting off the object that gives it its perceived hue - the way we perceive colour now) but colour was also used to describe the way in which the people experienced the world. A really good way to think about it is now, if you wanted to distinguish between two types of blue, you would instinctively make a distinction between their shades ("This blue is darker/lighter!") whereas these older people would distinguish based on things in their present, shared world that best matched what they were being asked to describe ("This blue is like the sky/the sea!")

That's an important concept to keep in mind because ancient greek was very unique in that, in addition to this concept of colour being completely intertwined with physical objects (and therefore also acquiring the properties of these objects in the minds of the people), the ancient greeks also did not particularly care about distinguishing between different colour hues (that is, differences in specific individual colour) but rather they were entirely focused on a colour's value - that is, whether it was considered light or dark.

Taking all of this into consideration, the question 'what is the significance of the different colours in Ancient Greece' is a bit of a tricky one to answer because unlike say, Ancient Egyptian which has very clear colours (red, white, green), very clear physical objects that give those colours their property (the desert sand, the sun, people's skin) and very clear symbolic meanings that arose from the natures ascribed to those physical objects due to their influence on the people's lives (hostility, power, new life), Ancient Greece's colours and the perception of those colours was much more abstract and poetic, contingent on their understandings and perceptions of things like light and dark, the sense of touch or taste (sweet and bitter/wet and dry) and what quality was ascribed to the object whose colour is being perceived. Colour was a matter of cosmology, of philosophy and there were many different schools of thought on it from Empedocles' physicalist theories to Anaxagoras' realist theories.

All of this is to say, take the meanings I outlined in this handy-dandy table with a tablespoon of salt! These are based on my understanding of the language used to describe things in classical writings that have survived and my own bias towards Empedocles' physicalist theory of colour and the nature of colour which I also think is very useful for people into greek mythology as a whole due to it making clear links between various gods creating things from mixtures of the four basic elements of nature and the colours that are the result of these mixtures.

I hope this helps even a little and I very much encourage you to do some research into different Greek schools of thought when it comes to colour and the perception of colour as well as how colour affects/reflects the innate nature of all things!

(Also, slight extra note, I left out Kokkinos (scarlet/blood-red) from the table because I didn't really think it was relevant for this outline despite it definitely being an ancient colour. It's a bit difficult to find examples of it with the kind of descriptors Empedocles outlines and I don't want to make assumptions based on third hand knowledge on the greek concept of the nature of things. I'd like to believe it was addressed in more detail in Empedocles' original document - only a fragment of the original some two thousand lines have survived after all - it is confirmed that Empedocles spoke on the recipe for blood and flesh, an equal mixture of all four elements as opposed to bones' four parts fire, two parts earth and two parts water (which is why bones shine white, there's more fire than earth or water) - and I don't want to conject or make assumptions.

I also left out Erythros or basic/primary red according to Plato's list of basic colours because that seemed to have specifically been preferred by Egyptian Greeks according to linguistic data. If I opened up that can of worms with respect to the shared Egyptian-Greek colour language including the way the Greeks like many early peoples did not culturally perceive blue until the invention of Egypt's blue dyes then I would be writing forever and you would never get an actual clear answer about Greek colour symbolism separate and apart from Egyptian cultural influence lmfao. )

A few of the documents that helped me consolidate this information include Sassi's 2022 Philosophical Theories of Colour in Ancient Greek Thought and Ierodiakonou's Empedocles on Colour and Colour Vision. There are also a fair few translations and discussions of the fragments of Empedocles' On Nature still floating about - my copy is a somewhat archaic volume of Leonard's 1908 translation but I never went out searching for updated interpretations and translations of the text since its constantly referenced in perceptional philosophy papers LOL

Anyway, yeah, hope this helps! :D

#ginger rambles#ginger answers asks#I don't know if this is what you wanted but I really really hope it helps!!#I wish I was able to find a way to actually have the table in this response but I'm just not good with stuff like that so I just decided#to link it instead; hopefully that's not too troublesome#There's a LOT to talk about when it comes to the greeks and their perception of colour#The discussion of colour and how languages evolved to accommodate them is also a very fascinating thing#Yes I am a historical linguist how did you know#Both kyanos and porphyrous are really fun because you can tell they were adopted later#because they come from the names for gemstones that were already in circulation and trading as opposed to words unattached to an observable#tangible feature in the world#Like pyrros is named after fire vs kokkinos which is named after the holly seeds#that were grinded up to make red dye that they used for their clothing#which is another reason I chose to use pyrros over kokkinos on the table#Seriously though#This stuff is mad interesting I highly suggest you take a day and just go down the rabbit hole a bit#Even small things like this can help massive recontextualise the often distant and detached way modern audiences are prone#to treating mythologies from the cultures that they were deeply ingrained in#greek mythology#linguistics#I guess LMFAO#Cosmology#Extra secret fun fact#My Hyacinthus is a realist aka he doesn't believe in all this four elements stuff#He quicker subscribes to the realist school of thought made apparent by sticks in the mud like Anaxagoras and Parmenides#ginger chats about greek myths

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

actually those first philosophers who denied the possibility that the void could exist were onto something

#how can Nothing exist#what is between a particle and another#Nothing?#so we and the whole universe are just a net of nearby particles and are 50% Nothing?#do you hear yourself#haven't you learned anything from Parmenides#how can you accept to exist in a logically and ontologically contradictory form

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

exploring amphoreus right now and THE PHILOSOPHY REFERENCES ARE ACTUALLY GIVING ME LIFE AAAA

#the diogenes reference?#THE PARMENIDES DEBATE???#AGEJROFJSOANFKSPE#i’m actually freaking out about this i love it SO MUCH#no doubt there are more references i have yet to find as well#it’s just SO COOL and that debate was actually so fun#r’s random thoughts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Time” understood in the Greek manner, χρόνος, corresponds in essence to τόπος, which we erroneously translate as “space.” Τόπος is place, and specifically that place to which something appertains, e.g., fire and flame and air up, water and earth below. Just as τόπος orders the appurtenance of a being to its dwelling place, so χρόνος regulates the appurtenance of the appearing and disappearing to their destined “then” and “when.” Therefore time is called μακρός, “broad,” in view of its capacity, indeterminable by man and always given the stamp of the current time, to release beings into appearance or hold them back. Since time has its essence in this letting appear and taking back, number has no power in relation to it. That which dispenses to all beings their time of appearance and disappearance withdraws essentially from all calculation.”

Martin Heidegger, Parmenides

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

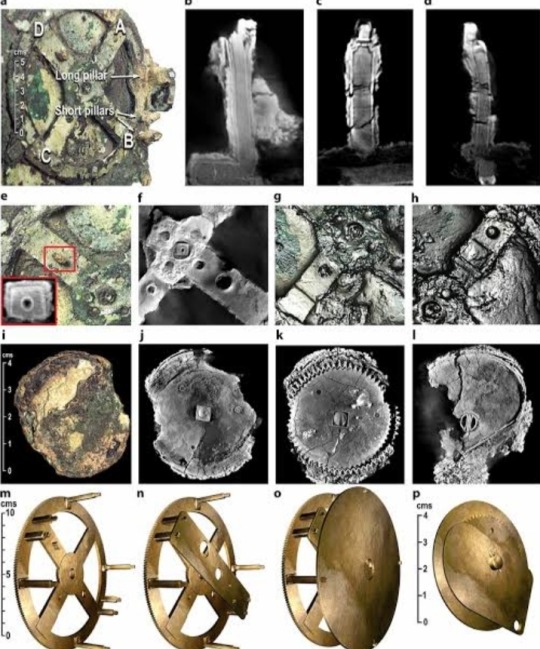

Antikythera Mechanism

Researchers claim breakthrough in study of 2000 year-old Antikythera mechanism, an astronomical calculator found in sea.

From the moment it was discovered more than a century ago, scholars have puzzled over the Antikythera mechanism, a remarkable and baffling astronomical calculator that survives from the ancient world.

The hand-powered, 2000 year-old device displayed the motion of the universe, predicting the movement of the five known planets, the phases of the moon, and the solar and lunar eclipses.

But quite how it achieved such impressive feats has proved fiendishly hard to untangle.

Now researchers at UCL believe they have solved the mystery – at least in part – and have set about reconstructing the device, gearwheels and all, to test whether their proposal works.

If they can build a replica with modern machinery, they aim to do the same with techniques from antiquity.

“We believe that our reconstruction fits all the evidence that scientists have gleaned from the extant remains to date,” said Adam Wojcik, a materials scientist at UCL.

While other scholars have made reconstructions in the past, the fact that two-thirds of the mechanism are missing has made it hard to know for sure how it worked.

The mechanism, often described as the world’s first analogue computer, was found by sponge divers in 1901 amid a haul of treasures salvaged from a merchant ship that met with disaster off the Greek island of Antikythera.

The ship is believed to have foundered in a storm in 1st Century BC, as it passed between Crete and Peloponnese en route to Rome from Asia Minor.

The battered fragments of corroded brass were barely noticed at first, but decades of scholarly work have revealed the object to be a masterpiece of mechanical engineering.

Originally encased in a wooden box one foot tall, the mechanism was covered in inscriptions – a built-in user’s manual – and contained more than 30 bronze gearwheels connected to dials and pointers.

Turn the handle and the heavens, as known to the Greeks, swung into motion.

Michael Wright, a former curator of mechanical engineering at the Science Museum in London, pieced together much of how the mechanism operated and built a working replica, but researchers have never had a complete understanding of how the device functioned.

Their efforts have not been helped by the remnants surviving in 82 separate fragments, making the task of rebuilding it equivalent to solving a battered 3D puzzle that has most of its pieces missing.

Writing in the journal Scientific Reports, the UCL team describe how they drew on the work of Wright and others.

They used inscriptions on the mechanism and a mathematical method described by the ancient Greek philosopher Parmenides to work out new gear arrangements that would move the planets and other bodies in the correct way.

The solution allows nearly all of the mechanism’s gearwheels to fit within a space only 25mm deep.

According to the team, the mechanism may have displayed the movement of the sun, moon and the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn on concentric rings.

Because the device assumed that the sun and planets revolved around Earth, their paths were far more difficult to reproduce with gearwheels than if the sun was placed at the centre.

Another change the scientists propose is a double-ended pointer they call a “Dragon Hand” that indicates when eclipses are due to happen.

The researchers believe the work brings them closer to a true understanding of how the Antikythera device displayed the heavens, but it is not clear whether the design is correct or could have been built with ancient manufacturing techniques.

The concentric rings that make up the display would need to rotate on a set of nested, hollow axles, but without a lathe to shape the metal, it is unclear how the ancient Greeks would have manufactured such components.

#Antikythera mechanism#astronomical calculator#ancient world#ancient civilizations#Antikythera#world’s first analogue computer#corroded brass#mechanical engineering#inscriptions#gearwheels#Parmenides#ancient greece#ancient history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hate how I can actually use Viktor's silly lil' glorious shenanigans for my metaphysics paper

#this is some parmenides and zeno type shit right here#arcane#arcane s2#arcane league of legends#viktor#the machine herald#viktor arcane#philosophy#philosophy major

5 notes

·

View notes