#panisse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

RANDOM MUSING: For anyone who might be a "foodie."

This week I bought some used books at my local public library resale corner for $1 each. One is a soft cover version of Alice Waters' seminal Chez Panisse cookbook. I already have a hardback version, but want to replace it with an easier to use softback. I didn't really look at it when I picked it up at the library. When I got home, I opened it up to flip through. On the flyleaf I see:

For Ron. Alice Waters.

Handwritten in big black Sharpie.

LOL. So, for $1 I got a Alice Waters signed copy of Chez Panisse. Thank you, public library.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

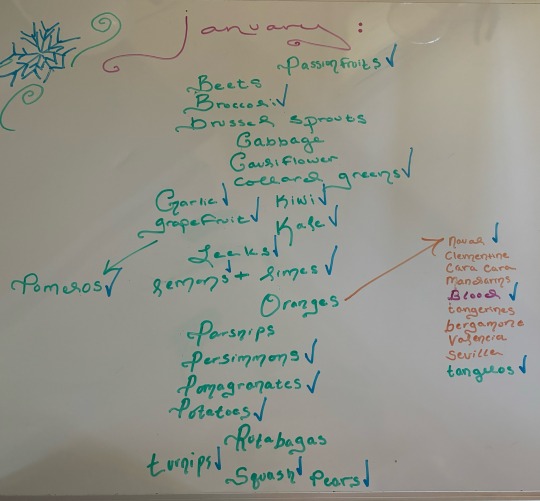

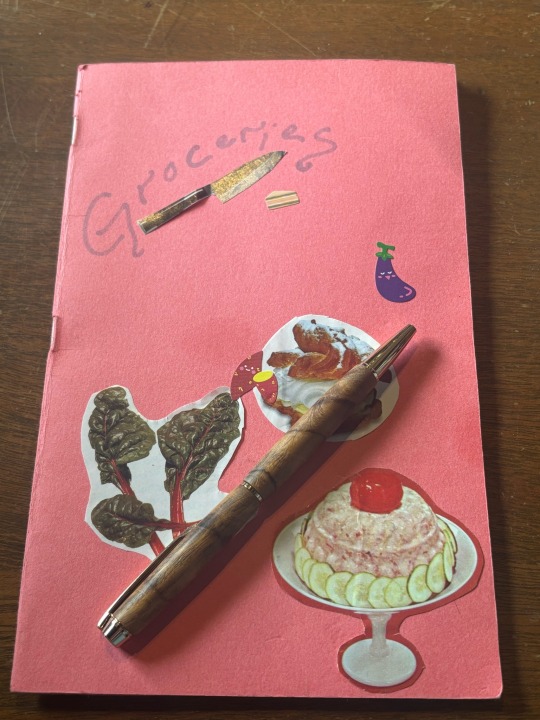

if grocery lists are poems, then the kitchen is an alter.

i’ve always had a fascination with food! my dad is a chef and everyday coming home from school i feared for my life as a picky eater with arfid because i never knew what food my dad was making for dinner that night because he loved cooking absolutely everything, it could be a random tuesday in march but coq au vin was on the menu for family dinner that night. i have a weird relationship with my dad now but i wouldn’t be doing what i do without him and his influence, all my le cruset was his, my favorite knives where his, i have all his chez panisses books…

one thing he was terrible at making where desserts- anything sweet he made was the worst dessert any of us had ever had each and every time, and as a little girl who LOVED dessert and sugar, i stepped in, i was the one making brownies and cookies every week because god forbid my dad step foot near a stand mixer and teaspoons.

as a professional baker now, looking back, signs that this was always destined to be my future where that when i was little making those box mix brownies/ cake every week, i was always trying to add something, or make the recipe better, i would approach every recipe with the intention of “how can i make this better” i couldn’t sit still with how easy it all was, there has to be room for improvement!!!!!!

and i still do that to this day, cute!

i really do think i am the best baker i personally know, even working with other bakers, i think people in the industry aren’t challenging themselves enough or wanting to do their research. in the beginning, before going through and doing a recipe, let’s say it’s marshmallows- i would go through every single recipe book i own and read each and every marshmallow recipe, then i will go on my phone and read recipes from substack and ba or nyt (never use those recipies google gives you, those make me sad) and i do my research !! i need to know all the pitfalls, all the possible techniques and people’s grandma’s secrets.

i think i’ll talk about cooking and baking on here often and post recipies i’ve been enjoying as a treat to the anonymous abyss that is tumblr

but what i actually wanna talk about it making dinner- i want to teach classes on how to make your grocery lists, how to grocery shop like a pro, and how to map out your weekly menus because i truly think when people start to cook their own food, they blossom, and they know it too !!

as a home cook, i also think it’s quite funny how you can always tell someone just started learning how to cook because they’ll proudly post things like, just some roasted vegetables they made, or an onion they chopped, or an ambiguous bowl of pasta on their instagram.. and they have so much pride in those simple things and i’m here for it !! yesss girl chop that onion and post those oven roasted Brussel sprouts and carrots !!!

they will soon hopefully feel the joy of doing things like saving all your vegetable scraps to make stock and the satisfaction of making their own bread or the absolute addiction it is to cook in a kitchen and have it feel like jazz, or a dance.

#cooking#food#baking#homecooking#pastry chef#seasonal produce#grocery store#groceries#chez panisse#anthony bourdain#reflection

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#illustration#drawing#camille de cussac#artists on tumblr#colorful#prada#sunglasses#panisses#south#france#marseille

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinner with friend | Placette | Marseille

Panisses maison.

0 notes

Text

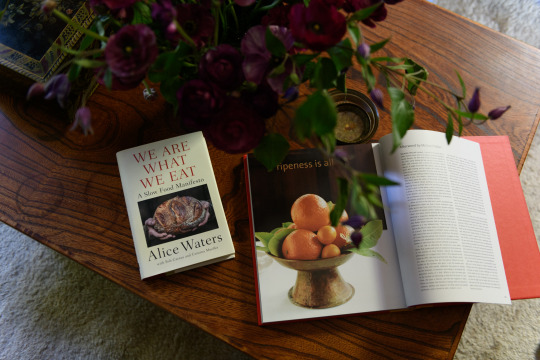

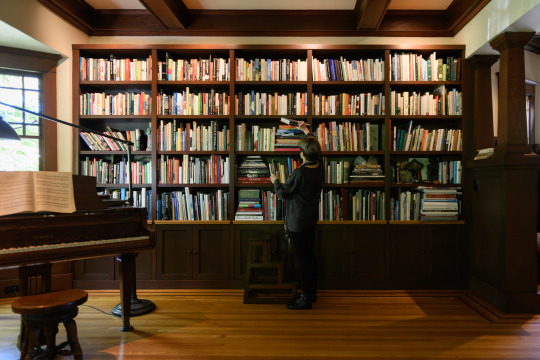

Alice Waters and Fanny Singer: Northern California Legacy Spotlight

Alice Waters needs no introduction but we'll introduce her anyway. In 1971, back from travels in the UK, France and Turkey, and channeling the counterculture, she opened Chez Panisse in Berkeley. The restaurant quickly became an icon of the farm-to-table movement with its menu of seasonal ingredients sourced directly from local farmers. Waters has remained at its forefront, expanding the movement through projects like Edible Schoolyard and the Chez Panisse Foundation. Despite her global success, Waters is for us one of Northern California’s true visionaries of the local, and it is hard to imagine our regional cuisine without her.

We spoke with Alice alongside her daughter Fanny Singer, an accomplished art critic, writer, new mom, and founder of Permanent Collection, a line of handcrafted homeware that tells the stories of the people who make each piece.

Studio AHEAD: How do you sit?

Alice Waters: I sit at the table and I like to sit in a chair. I love to be in front of the fireplace. It’s very important to be seated at a table. It can be oval or round. It doesn’t matter as long as everybody’s there together.

Fanny Singer: Sitting is something I either do a lot of or very little depending on the day. I have a one-and-a-half-year-old and spend a lot of time cajoling her at dinnertime into her seat. It’s become a new topic of conversation: How do we sit? How do we actually eat? How do we commune over this meal, because that was a very significant part of my childhood.

But the last year-and-a-half of having a baby, you’re standing eating out of the refrigerator, and not taking a moment to sit because you’re in between things. Recently we’ve made a real point to sit together with [Fanny’s daughter] Cecily, who loves to eat thankfully. We sit on either side of her and light candles, which she loves. She goes “candles, candles, candles” if we forget. So after a year-and-a-half of very frenzied never sitting down for a proper meal, we’ve reintroduced a real sense of ritual in how we wind down from our day and enjoy this moment of communal eating together.

Studio AHEAD: I love that both of you have fire—Alice with the fireplace and Fanny with the candles. It’s warmth. Fire always has that effect of calming.

Alice: I light candles, too! It’s the beauty of the light. When you light a candle at the table it’s like a ritual. You all are there. And in candlelight everyone looks good.

Studio AHEAD: Do ideas of space—of people being together in a room, whether at one of your restaurants or at home—influence your approach to cooking? To laying out a menu?

Alice: I love the connection between the kitchen and the dining room. It means that the people who are dining [at Chez Panisse] can see where their food comes from, and they can watch if they want to go into the kitchen. Just take a peek before they sit down. They're welcome. It’s not like you’re trying to hide something. There’s a big fireplace in the kitchen, so most people do want to take a look.

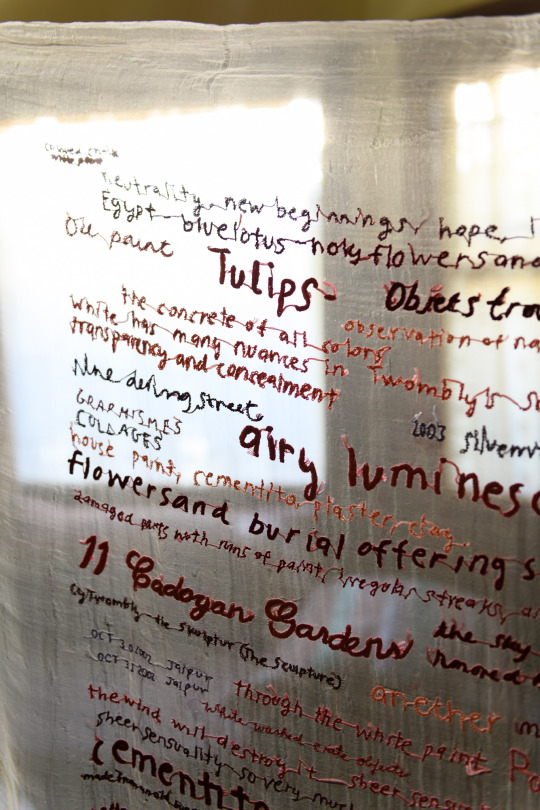

Fanny: I’m so fascinated by that question in terms of thinking about it relative to what is cooked. Permanent Collection recently launched a new project called the Platter Project. Most of the products that we make are kept in stock. We reissue them. The idea is to keep good design readily available. But we thought it would be nice to work in a more limited-edition capacity with artists and artisans to make something that stood apart from a design perspective or just felt different.

When I was thinking about the form that this idea could take, the platter was the only idea that made sense. There is something about that shape, generally oval or circular or round, that has this sense of generosity and compatibility with food. It’s the way we plate and the way that plates then convey accessibility: a round plate can be reached into and served out of from every side. There's always a family-style relationship to service and dining in our families and also at Chez Panisse.

I mean even the downstairs, which is more formal, doesn't feel like there's not a permeability. There’s an invitation to taste and share that’s always been the philosophy when I cook, too. My tables and those spaces in which I've cooked have varied widely over the course of my life, from graduate school kitchens—tiny, fluorescently lit spaces that my mom suffered through visits to, but always brought candles—to the home that I live in now in Los Angeles. I feel like platters and those shapes that we bring to the table are transcendent. There’s always a beauty to be found in how we bring food to the table.

Alice: I always love a big bowl of usually a fruit in the middle of the table. Whatever is in season. It’s full of oranges right now, apples. You’re probably going to eat some of it at some point but it’s so nice to see something beautiful when you sit down.

Studio AHEAD: I love at Chez Panisse you have the copper plate with the fruit for dessert. It’s an invitation to sharing. It’s changing boundaries.

We recently did an interview with Nobuto Suga who talked about different trees suggesting different objects to make with them and being true to the local wood. Fanny, I think this relates to Permanent Collection with your focus on the people who make what you sell.

Fanny: Absolutely. It was the raison d'etre of what we do: to bring the people who craft the things that we make into the foreground. It’s what distinguishes not just Permanent Collection, but any products that are artisanally produced and not mass manufactured. It’s evidence of the hand that makes the things.

The Japanese ceramicist who makes our beautiful green ceramic plates… the plates are immaculate, but there's always some slight difference. There's not a sense of them being pressed into a mold by a machine and turned out in perfect uniformity.

It’s the wabi sabi approach to setting the table and thinking about the things that you're putting into your mouth and the context in which they are delivered to you—the ethos around production for us absolutely stems from that. You want to understand the hand that's behind the carrots as much as you want to know the story of the hand behind the dishes.

Alice: Of course, the color of the dishes is always important to me. What I'm putting on the plate is enhanced by the color of the plate. It’s great to have all different shapes and cups. I like those charming irregularities.

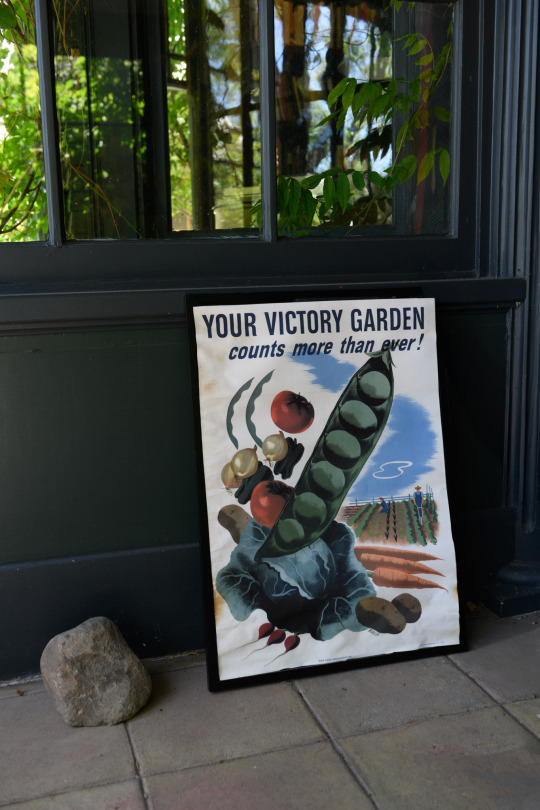

Fanny: That’s always been the defining philosophy of Chez Panisse: that very, very little needs to happen on the culinary side of things if what you're cooking with has been grown by people who are working in concert with nature, and that that connection between the people who grow the food and the natural world is something that you can taste, becomes manifest on the plate.

Studio AHEAD: Fanny, you have a PhD in art history. Has this guided how you choose which craftspeople to work with? The sculptural quality of the pieces is undeniable. I'm also curious about the name Permanent Collection, because so much of what the farm to table movement pays attention to is seasons. It's the opposite of permanent.

Fanny: I think I would quarrel with that or at least say there isn’t an exact one-to-one correlation in terms of how we think of the permanence of what we have on the table versus the perennial or the always changing nature of nature and agriculture.

There’s a deep sustainability infused in both, to have things that are heirloom quality that will last forever in your home. Objects that can be passed down from generation to generation are truly in tune with nature in the same way that tending the land and caring for the land displays that same respect and reverence for not wasting, not extracting totally.

That said, how could my PhD not play into it? I mean, I spent the better part of my professional life thinking about art and writing about it. Not just in my PhD, but also as an arts critic and culture reporter. It's part of what drew Mariah Nielson and I to one another. What first started Permanent Collection was this idea that we had really honed our sensibility and also sensitivity to what makes good design and good art. There was something in all that cumulative time of observing and learning that gave us maybe not a talent per se but an openness and an ability to discern what makes something feel like it might be timeless or it might resist trends or fads. That’s where the permanent in Permanent Collection comes in. It was meant to echo that ethos that governs how things are brought into the permanent collection of museums.

They have to stand. They have to prove they will stand the test of time and that they will be good examples of design at a certain time. They will teach us about what people cared about in that moment.

Alice: I think about what I’m using in my everyday life and people think that there are some things that are too precious to use. You put them in a cabinet over there, you never drink out of those beautiful glasses or one of them might break. I just feel like it's such a shame to not remember the person who gave it to you.

I'm just holding this sterling spoon. It was given to me by a friend in Ireland, and every time I use it, I think about her. The same way with my cafe au lait bowls; they're all different, but they come to me at different times in my life from different people. They always bring me a kind of sense of comfort and connection. I love that.

I think what Fanny's doing with Permanent Collection is helping to make that available to people in their everyday lives: the colors that they choose… to bring that beauty back to the table.

Studio AHEAD: Can you share a memory you have with a specific kitchen tool?

Alice: I think it’s a mortar and pestle for me because I make, every day probably, a vinaigrette. I always take a little bit of garlic and use that Japanese mortar and pestle that's grooved. Then I put my vinegar in, let it marry, calm the garlic down.

Fanny: Of course mine is the same tool. We made a mortar and pestle called Alice's Mortar and Pestle, which was an homage to the ones that were ever present in my mother's kitchen. The one that we make for Permanent Collection is made by a wonderful potter in Northern California called Colleen Hennessey.

I make salad dressing in it on a daily basis. It is also a tool that has this relationship to the huge mortar and pestle of Lulu Peyraud at Domaine Tempier who is my mom's mentor and a kind of surrogate grandmother to me. She used her mortar and pestle every day, too.

It was a much more rustic, almost molcajete-looking mortar and pestle, and she would use it to make aioli. She would pound the garlic and then bring the whisk. I think she would use the old school technique of whisking the olive oil with a little piece of potato on the end of a fork. [Alice laughs.] At least I remember seeing her doing that when I was little. There were so many other sauces that she would make in there, whether it was pounded anchovies or black olive tapenade. Or the monkfish liver, bready, aioli-y, delicious sauce that's made to add into bouillabaisse.

Studio AHEAD: Alice, you’ve spoken many times about the influence the Montessori School had on you. How do you follow recipes while also being open to experiment and imagination?

Alice: I have to say that I'm not somebody who follows recipes. I mean, I learned to cook from French cookbooks, but very, very simple ones like Elizabeth David's and Richard Olney's books. I liked knowing I could look at a longer recipe if I wanted to, like Julia Childs who could make it work.

But I'm looking mostly at the ingredient and what it needs to make it really something special at the table. Maybe it's just a tomato and needs vinaigrette, but maybe it wants to be stewed or made into a sauce. I'm sort of just letting the food speak to me.

Maria Montessori’s greatest gift was understanding that our senses are pathways into our minds. When you're not touching and tasting and smelling and looking at beautiful things… she wondered why the children who lived in poverty and hunger back in the 1880s didn't learn the way other children did in school. She created a way of learning by doing, a way of engaging children at a very early age with smell and taste and touch.

Studio AHEAD: This leads to my last question, which is that recently in a New York Times interview you talked about the tactile richness of food. Are you telling us to eat with our hands?

Alice: I certainly am! I don’t think I can eat a salad with a fork. I'm always picking up the leaves and putting them in my mouth. But there is something absolutely important about feeling and not just fruit. Just being able to touch the ingredient, like a string bean and dip it into the aioli or whatever you're doing and you're engaged in a very immediate way. You're not letting that fork in between you and the food. I eat that way all the time, even at the restaurant when I'm a guest. I think people around the world have always used their hands in some way when they're at the table. Something about the fork can get in the way.

Studio AHEAD: I love that. The fork can get in the way. That's my new motto when I'm eating with my hands.

Fanny: That's also Cecily’s motto!

Studio AHEAD: I was going to say. How has it been watching Cecily eat? Are you eating with your hands more?

Fanny: Absolutely. I'm not sure I ever stopped with my hands. Our family has always been a family of picking food up and touching it and sort of getting a sense of it. The tactility of it is the most immediate reaction. To pick up a lettuce leaf and to try it, or even when you're cooking a steak you're touching it to see, Is it done? Is it too rare? I watched my mom cook by finger-feel almost more than with implements in a way. It was the intuition around whether something was properly prepared or not.

So fingers are important utensils in our house. Cecily is learning how to use spoons or what she calls "boons." I'm not trying to rush her. There's a lot of intelligence in the tactility and the feeling of texture that helps you understand whether something is juicy or dry or liquid or solid.

I think it's part of the education of how you use your senses and how you eat.

Photos by Ekaterina Izmestieva

#alice waters#fanny singer#permanent collection#studio ahead#northern california#studioahead#california#san francisco#berkeley#chez panisse#edible gardens

1 note

·

View note

Link

where the serveware at Chez Panisse is made and sold

0 notes

Text

Chez Panisse ratatouille with crispy capers, fried sourdough & a rich, thick and spicy aïoli.

What I really really wanted was to go to my favourite bakery on sunday and get one of their crusty baguettes - the best in the city - and have a ratatouille & aïoli sandwich, but they didn't make any that morning. C'est la vie.

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

I went to an exhibition in the city that's like... It's set up so you buy a ticket and you get a glass and you go around a giant hall getting samples of wine and food from exhibitors, basically. I made three alcoholic beverage purchases (one was a little variety pack, oho) and also got a bottle of kombucha and a cute sample pack of tea! Yay. :)

Exhibitors are only allowed to pour you so much wine at a time, obviously, but it is nevertheless very easy to end up mildly tipsy. I have never even tried a montepulciano wine but I really liked the one I sampled today. How nice.

I also tried so many cheeses. Someone had a hard salty cheese with the perfect chilli infusion. That guy was a genius.

And there were two French guys who had panisse, which I've never tried before either. It's basically, like... chickpeas are to panisse as soy beans are to tofu? I guess? That's probably the best way I can describe it. It was nice, I really liked it.

So I did that today. It took 4 hours and I am so tired and my feet hurt because I foolishly wore heeled boots. Hoo.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Security for the Chickens: Alice Waters gushes about Meghan's garden complete with chickens!!! The kiddos can play hide and seek!! She grows corn! by u/wenfot

Security for the Chickens: Alice Waters gushes about Meghan's garden, complete with chickens!!! The kiddos can play hide and seek!! She grows corn! More comedy gold from the Daily Mail article about the bees. SeCurITAY for the chickens and plants!!! A quick note about Alice Waters: Anthony Bourdain did not like her:Bourdain sometimes publicly expressed frustration with Waters' approach, describing it as "Khmer Rouge-like" or "Pol Pot in a muumuu," implying that her focus on high-quality, expensive ingredients could be seen as elitist and unrealistic for the average person. *************Meghan’s passion for fine cuisine is such that she recently offered to work in a top restaurant’s kitchen, reveals famed American chef Alice Waters, who appears as a guest star in ‘With Love,’ Meghan.’‘ She said she would love to come and be in our kitchen,’ discloses Waters, aged 80, godmother of California cuisine, who pioneered the farm-to-table culinary movement at her famed restaurant Chez Panisse in Berkeley, Northern California.‘ I told her: “We take interns, and if you have time, please come, you could be an intern.” I think it would interest her. I hope she was serious about coming. I don’t know what she’s allowed to do. It’s very strict, her security. ""Her garden is beautiful,’ says Waters. ‘It’s substantial in terms of biodiversity. She has a whole herb garden, corn, every colour of tomato, cherry tomatoes and larger ones, beautiful purple radicchio, and all kind of fruit trees, orange and citrus. It was very impressive. She grows potatoes and carrots - we ate some of her carrots right there in the garden.‘She has chickens in the garden, and on the table were all different colours of eggs that she had collected with her kids. Meghan also composts, with discarded food scraps, the whole thing.‘ I always learn something from people’s gardens. Meghan’s had winding paths where you could play hide and seek. I loved that you could hide behind the raspberry bush. It seemed so charming.’Oh Dear GOD. Meghan's charming garden that I bet 999.999% is maintained by others? Can you even grow corn in a garden? Is it "normal" to have chickens in a garden? Since I am definitely a plant assassin (yes, I killed a cactus) I would love to hear if any of this is even possible. post link: https://ift.tt/wm7NTbJ author: wenfot submitted: February 28, 2025 at 03:38PM via SaintMeghanMarkle on Reddit disclaimer: all views + opinions expressed by the author of this post, as well as any comments and reblogs, are solely the author's own; they do not necessarily reflect the views of the administrator of this Tumblr blog. For entertainment only.

#SaintMeghanMarkle#harry and meghan#meghan markle#prince harry#fucking grifters#grifters gonna grift#Worldwide Privacy Tour#Instagram loving bitch wife#duchess of delinquency#walmart wallis#markled#archewell#archewell foundation#megxit#duke and duchess of sussex#duke of sussex#duchess of sussex#doria ragland#rent a royal#sentebale#clevr blends#lemonada media#archetypes with meghan#invictus#invictus games#Sussex#WAAAGH#american riviera orchard#wenfot

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poutargue (Cured Mullet Roe)

When Ava and I where in Marseille last year, enjoying a lingering Summer during the Rugby World Cup, we thoroughly enjoyed the local cuisine and tasting Provençal specialities. We ate navettes on Catalans Beach on the first evening there before watching the sun set on the Mediterranean Sea, we ate Pastis-flambéed prawns on the Frioul Islands, and dined on Bouillabaisse. We had a hard time finding panisses --chickpea flour fritters-- though and thought we'd leave without tasting them, but on one of the nights, we had dinner on le Vieux-Port, and hot and crispy panisses were brought with our cocktails. Panisses and Poutargue! This salty cured mullet roe pouch, cut into thin slices was a delicious discovery! Thus, when I bought beautiful fresh mullets at the market the other day, and the fishmonger inquired, while preparing the fish, whether I wanted the roe, I acquiesced enthusiastically! I knew I wanted to try and make my own Poutargue, and having a slice of this, with a glass of chill Pastis, even though this Sunday is awfully wet and rainy, it's almost as if I'm back under the cloudless azure skies of Marseille with my girl... Have a good one, friends!

Ingredients (makes 1):

the roe pouch of a fresh grey mullet

1/2 cup coarse sea salt

1/4 cup natural beeswax

Thoroughly and carefully rinse the roe pouch under cold water.

Gently pat it completely dry with paper towels. Set aside.

Place coarse sea salt in a mortar, and grind with the pestle until a fine texture (resembling coarse meal.

Spoon half of the salt into an even layer, roughly bigger than the pouch, onto a small plate. Place roe pouch onto the salt, and cover with remaining salt, making sure it's all hidden under it.

Set aside, to cure, 2 to 4 hours.

After four hours, rinse the salt off the roe pouch under cold water. It should have hardened by then, and taken on a golden hue.

Pat it thoroughly dry with paper towels, and place onto a small wooden board.

Place in a very cool place, not necessarily draught-free, but dry (a refrigerator is fine).

Flip poutargue every day, to ensure even drying, for at least a fortnight.

Once ready, melt beeswax in a small bowl fitted over a small saucepan of simmering water.

Once melted, dip poutargue into the beeswax, covering it entirely. Shake off excess beeswax, and return poutargue onto wooden board. Allow beeswax to dry and harden completely.

Serve Poutargue cut into thin slices, alongside Green Olive Tapenade, Anchoïade and glasses of Pastis for a truly Provençal apéritif. It is also apparently divine grated onto spaghetti!

#Recipe#Food#Poutargue#Poutargue recipe#Cured Mullet Roe#Cured Roe#Mullet Roe#Mullet Roe Pouch#Roe#Roe Pouch#Grey Mullet#Fish and Seafood#Coarse Sea Salt#Salt#Beeswax#Easy recipe#5 Ingredients or Less#Appetizer#Appetizer recipe#Appetizer and Entrée#Provençal Cuisine#Provencal Cusine#Cuisine de Provence#Provence Cuisine#French Cuisine#Regional Cuisine#Food and Travel#Marseille#Bouches-du-Rhône#Provence

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

what if instead of "chez panisse" it was spelt "chez penis". lol

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

17 and 23 for the end of year asks?

17. What are some hobbies that you developed?

i continued doing pottery after picking it up in 2023, and i actually miss it so so much now that we've moved and i'm no longer close to my old studio! i also tried to do a lot more cooking and actually make recipes from my cookbooks. my favorites were the chez panisse fruit and vegetable cookbooks and i came upon some really great dishes that are now standbys for me, like a swiss chard casserole and one for winter root vegetables.

23. One of the best meals you've had this year?

i went to get new year's oden with my roommates in january and as i was coming out of some pretty brutal stomach health woes (which still plague me somewhat) it was the first proper meal i had that didn't make me, like, sick. and it was at a restaurant we all love so so much and it was a beautiful night and the oden was so delicious and warm. and i remember kind of feeling like i was coming back into the world again after being sick.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does art make a difference?

Aw, sure. Of course there are degrees of extremity to the potential change that art can effect, depending on how many people are able to engage with it. The Beatles made a huge difference in the world. But Henry Darger, Jeff McKissack, Karen Dalton, Pauline Oliveros, Kenneth Patchen – there are so many folks who have made great art and not gotten massively famous for it, yet I think there are all sorts of ways their work informs and shapes other people’s work, and brains, and decisions.

Should politics and art mix?

Well, everything mixes, the New Statesman! That’s like asking if a knee-reflex hammer and a quadriceps tendon should “mix”.

Is your work for the many or for the few?

That’s for the many/few to say. I just crank out the hot jams.

If you were world leader, what would be your first law?

Gravity. I feel like we need to tighten up the constitutional protections that particular law enjoys. It’s a ticking time bomb, if you ask me.

Who would be your top advisers?

Cute angel on one shoulder, cute devil on the other.

What, if anything, would you censor?

Maybe we could all agree to not bust each other’s chops all cut-dang day.

If you had to banish one public figure, who would it be?

Don’t know, banishment might be a little extreme, but I’d sure like to take that Stephen Hawking dude down a notch or two. Right? Are you with me?

What are the rules that you live by?

Basically, “bros before hos”. I feel like if you stay true to that, everything else just kind of falls into place.

Do you love your country?

I love William Faulkner, Dolly Parton, fried chicken, Van Dyke Parks, the Grand Canyon, Topanga Canyon, bacon cheeseburgers with horseradish, Georgia O’Keeffe, Grand Ole Opry, Gary Snyder, Gilda Radner, Radio City Music Hall, Big Sur, Ponderosa pines, Southern BBQ, Highway One, Kris Kristofferson, National Arts Club in New York, Ruth Crawford Seeger, Joni Mitchell, Ernest Hemingway, Harriet Tubman, Hearst Castle, Ansel Adams, Kenneth Jay Lane, Yuba River, South Yuba River Citizens League, “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore”, “Hired Hand”, “The Jerk”, “The Sting”, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid”, clambakes, lobster rolls, s’mores, camping in the Sierra Nevadas, land sailing in the Nevada desert, riding horseback in Canyon de Chelly; Walker Percy, Billie Holiday, Drag City, Chez Panisse/Alice Waters/slow food movement, David Crosby, Ralph Lauren,San Francisco Tape Music Center, Albert Brooks, Utah Phillips, Carol Moseley Braun, Bolinas CA, Ashland OR, Lawrence KS, Austin TX, Bainbridge Island WA, Marilyn Monroe, Mills College, Elizabeth Cotton, Carl Sandburg, the Orange Show in Houston, Toni Morrison, Texas Gladden, California College of Ayurvedic Medicine, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Saturday Night Live, Aaron Copland, Barack Obama, Oscar de la Renta, Alan Lomax, Joyce Carol Oates, Fred Neil, Henry Cowell, Barneys New York, Golden Gate Park, Musee Mechanique, Woody Guthrie, Maxfield Parrish, Malibu, Maui, Napa Valley, Terry Riley, drive-in movies, homemade blackberry ice cream from blackberries picked on my property, Lil Wayne, Walt Whitman, Halston, Lavender Ridge Grenache from Lodi CA, Tony Duquette, Julia Morgan, Lotta Crabtree, Empire Mine, North Columbia Schoolhouse, Disneyland, Nevada County Grandmothers for Peace; Roberta Flack, Randy Newman, Mark Helprin, Larry David, Prince; cooking on Thanksgiving; Shel Siverstein, Lee Hazlewood, Lee Radziwill, Jackie Onassis, E.B. White, William Carlos Williams, Jay Z, Ralph Stanley, Allen Ginsberg, Cesar Chavez, Harvey Milk, RFK, Rosa Parks, Arthur Miller, “The Simpsons”, Julia Child, Henry Miller, Arthur Ashe, Anne Bancroft, The Farm Midwifery Center in TN, Martha Graham, Alvin Ailey, Jr., Eleanor Roosevelt, Clark Gable, Harry Nilsson, Woodstock, and some other stuff. Buuuut, the ol’ U S of A can pull some pretty dick moves. I’m hoping it’ll all come out in the wash...

Are we all doomed?

If we keep our expectations pretty low I think we might be fine. I mean, we’re definitely all dying at some point. There’s no getting around that. But between now and then, things might start looking up!

— Joanna Newsom for The New Statesman, 2008

#joanna newsom#isn't she simultaneously just the most hilarious and thoughtful person?#i love her so much#a few people have asked me for that one quote about loving her country but the whole interview is a real gem i hope y'all enjoy it#love joanna#jnew

20 notes

·

View notes