#paleographic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

just finished rewatching go2, and while of course there is a lot to be said for heavenly brainwashing and a general lack of proper communication, and while that is of course a huge part of it, i've barely seen anyone talking about just how little aziraphale actually wanted to go to heaven. almost all the way through the whole last bit.

when aziraphale is first approached by the metatron, he says that he's made his position perfectly clear. he knows where he stands, and so does everyone else. he stands with crowley, they're on their own side. but he decides to hear the metatron out, because what could he possibly say that would change his mind?

(i also think it's worth mentioning that the metatron opened with coffee. i don't personally believe in the coffee theory, but he may have started with that to show aziraphale that he's on 'his side.' he's not like the other angels, he's consumed things. he's gone against what angels expect.)

and at first, when the metatron gives his offer, aziraphale turns it down completely. he said it clearly, he doesn't want to go back to heaven. even as the metatron continues to detail all of these reasons why aziraphale should lead, aziraphale still looks pretty uncomfortable.

but the metatron can clearly see this isn't working, so he uses what he knows will always get aziraphale. crowley. he offers to restore him.

so aziraphale starts thinking. what if he accepts the offer? as so many other people have pointed out, there is no way aziraphale could have even come close to completely breaking out of the way he'd been taught to think for millions of years. so he thinks, well, heaven are the good ones. it would certainly be better if they were on the right side of things, wouldn't it? and crowley is a good person, he's seen it.

not to mention that crowley seemed so much happier when he was an angel. and to aziraphale, of course, it's because heaven are the good ones. crowley was so angry because he got lumped in with the bad ones. he just doesn't understand that maybe crowley was so angry because of the whole idea of a 'great plan', of the 'good ones' and 'bad ones' in the first place.

and finally, his decision was about safety. of course aziraphale wants to be with crowley. but they've been hiding from heaven and hell this whole time. if the metatron was being completely honest (which he obviously wasn't, that was a suspicious offer, but in aziraphale's situation he couldn't tell), they wouldn't have to hide, they could be together.

and so of course he rushes home to tell crowley, and of course crowley refuses, and has his big confession.

which, to be perfectly honest, i don't think was a horrible coincidence, or incredibly tragic timing. setting aside the fact that it just happened after the whole 'gabriel and beelzebub' incident, the metatron planned that.

he knew that crowley would refuse, because he never would accept an offer like that. and maybe he gathered that crowley would confess from the gabriel/beelzebub scene, maybe he overheard nina and maggie talking, it could have been anything.

the point is, it was the metatron's plan all along to have crowley refuse, confess, and storm out, leaving aziraphale heartbroken. that way he could come into the bookshop, hear it from aziraphale that crowley left.

because when crowley confessed, he did something that neither of them were used to. he said (at least a lot of) what he was actually feeling. and aziraphale has had millions of years of practice of denying exactly that, the instinct kicks in. he says "i forgive you". they both leave, heartbroken.

and at this point, when crowley is gone, and the metatron comes back in, what else is aziraphale going to do? he denies it. he does the very thing he refused in the first place, he goes to heaven, leaving everything behind, without crowley.

and only a few seconds afterwards, we can see that aziraphale regrets it. he starts trying to come up with excuses. he can't leave the bookshop—no, don't worry, muriel has that taken care of. do you need to take anything with you?—there isn't anything he can think of to get him out of this. he's run out of excuses.

and so it's too late. aziraphale is about to get into the elevator to heaven. but before he does that, he asks what the great plan that he'll be helping with is.

and the metatron says the second coming.

aziraphale knows he's been tricked, after this. if the second coming truly is the great plan, straight from the metatron, he can't 'fix heaven.' he can't improve anything if god's will is the second coming.

but what can he do? he gets in the elevator.

through the credits, we can see his shock, anger, and heartbreak so incredibly clearly. of course, until the smirk at the end.

that was the very moment when aziraphale made a plan to tear it all apart.

#this is a complete mess of like five different theories mixed together#this post brought to you by my computer autocorrecting 'aziraphale' to 'paleographers'#good omens spoilers#good omens#good omens 2#ineffable husbands#crowley#aziraphale#aziracrow#good omens analysis#good omens thoughts#good omens meta

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thesis update: I have created a monster.

Behold: the Old Monk Handwriting Conspiracy Board

Every weird number/letter combination is a medieval manuscript that might (!) belong to the group of manuscripts that I'm trying to figure out for my thesis.

Every line denotes some sort of connection various paleographers and art historians (color-coded) have drawn between these manuscripts.

(this isn't even technically all the connections, and it absolutely isn't even remotely all the manuscripts)

Also, "Reichenau" is not a manuscript but a monastery; notably not the one my academic blorbo scribe lived at, so essentially any line that ends up there is the academic equivalent of "idk what all these other dipshits were on about"

(also fun: all the codices with the most lines are also the fanciest codices, and it's a real pain to sort "this pretty book was genuinely influential in those monasteries back when it was made because let's be real, it fucks" from "this pretty book is well-known and researched and it's tempting to compare shit to it because of that")

#paleography#guardy commits paleographic atrocities#for dubiously effective science or some shit idk#thesis hell#guardy's paleography tag

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think that script is protogothic. or gothic. The feet of the letters are pointing right, so it’s probably written after 1100 or 1200CE?

Capital C from the first page of Catullus manuscript G.

#medieval manuscripts#paleography#does manuscript tumblr exist?#will these tags find the paleographers of tumblr?#let’s hope so

589 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday, September 27.

Langblr.

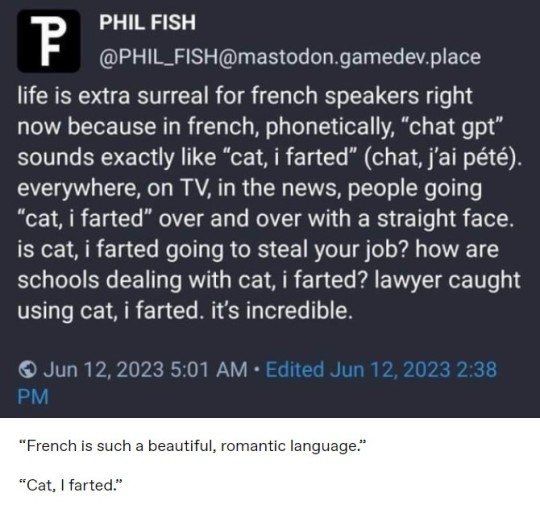

If ever you're in France, accompanied by your kitty cat, and you find yourself unintentionally (and quite unexpectedly) projecting intestinal gas produced within the body by bacteria that has broken down food, and said kitty cat looks a little alarmed, and you don't know what to say, well. Fortune smiles upon you this day. Consider #langblr your knight in shining linguistic armor. Chat, j'ai pété.

It really can happen to anyone. But langblr is here for all your polyglot needs: learning how to say chai tea in Czech, the frankly adorable etymology of peninsula, Greek paleographic fonts, for words of support for those underway with their language-learning adventures, or if you're in need of some support yourself. It is a particularly wholesome corner of Tumblr, for those with an interest in the slow-burn magic of learning another language.

#today on tumblr#langblr#french langblr#language learning#polyglot#foreign languages#learning languages#french language#language#language blog#languageblr#languages#langblog#bilingual#studyblr#catblr#cat#i farted#cat i farted#farty cat#linguistics#etymology#language stuff

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

As a knight, I was defeated.

As a monk, I was defeated.

As Grand Master, I was defeated!

I was reduced to ashes without having accomplished anything.

I will do it here and now!

———————-

The Chinon parchment was found in 2001 by Barbara Frale, an Italian paleographer at the Vatican Secret Archives. It contains the absolution of Jacques de Molay and the Knights Templar of all charges brought against them by Philip IV of France.

Eyewitness accounts said he went to his death ’… with easy mind and will that they brought from all those who saw them much admiration and surprise.’

———————–

I finished Knightfall last year and am about to finish reading my book about them and then suddenly he is brought forth as a character in FGO.

A strong feeling overcame me to draw him. To think that I had a long art block spell for months.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

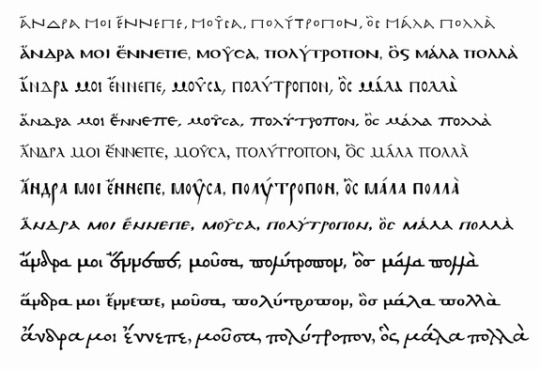

Greek paleographic fonts.

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Furfur Moments, Compiled

Ok I have been wanting to do this for a while because I think it is HILARIOUS. Here are my misspellings of “Aziraphale” from the most recent draft of my fic, in order of appearance:

Aziraphel

Azirapahle

Azirpahel

Aziraphle

Azirapahel

Azirpahle

Azirapahale

Azirpahale

Azirpaahle

Azriapahle

Azirpahael

Azirawpahle (ok now I'm just getting sloppy. “w”? Really?)

Aziraphrale

Followed by the suggestions that my poor spellcheck made to try and correct these heinous errors:

Aphelia

Arapahoes

Telegraph

Paleographer

Aziraphale (because I have indeed added this to my dictionary)

Triathlete (pls, can you imagine)

Paraphrase

And of course, the one and only, Airplane (iykyk)

#I hope this amused someone else today too#good lord spelling is hard#thank god for spellcheck#good omens#Aziraphale#We are all Furfur

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ségurant, the Knight of the Dragon (1/4)

In order to do my posts about Ségurant, I will basically blatantly plagiarize the documentary I recently saw - especially since it will be removed at the end of next January. If you don't remember from my previous post, it is an Arte documentary that you can watch in French here. There's also a German version somewhere.

The documentary is organized very simply, by a superposition of research-exploration-explanation segments with semi-animated retellings of extracts of the lost roman.

0: The origin of it all

The documentary is led by and focused on the man behind the rediscovery of Ségurant, the Knight of the Dragon – Emanuele Arioli, presented simply as a researcher in the medieval domain, expert of the Arthurian romances, and deeply passionate by the Arthurian legend and chivalry. If you want to be more precise, a quick glimpse at his Wikipedia pages reveals that he is actually a Franco-Italian an archivist-paleographer, a doctor in medieval studies, and a master of conferences in the domain of medieval language and medieval literature.

It all began when Arioli was visiting the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, at Paris. There he checked a yet unstudied 15th century manuscript of “Les prophéties de Merlin”. Everybody knows Monmouth’s Prophetiae Merlini, but it is not this one – rather it is one of those many “Merlin’s Prophecies” that were written throughout the Middle-Ages, collecting various “political prophecies” interwoven with stories taken out of the legends of king Arthur and the Round Table. And while consulting this specific 15th century “Prophéties de Merlin”, Arioli stumbled upon a beautiful enluminure (I think English folks say “illumination”) of a knight facing a dragon. Interested, he read the story that went with it… And discovered the tale of Ségurant, a knight he had never heard about during the entirety of his studies.

Here we have the first fragment of Ségurant’s story: “Ségurant le Brun” (Ségurant the Brown, as in Brown-haired, you could call him Ségurant the Dark-haired, Ségurant the Brunet), a “most excellent and brave knight”, sent a servant to Camelot, court of king Arthur, and in front of the king the servant said – “A knight from a foreign land sends me there, and asks you to go in three days onto the plain of Winchester, with your knights of the Round Table, to joust. You will see there the greatest marvel you ever saw.”

Checking the rest of the manuscript, Arioli found several other episodes detailing Ségurant’s adventures, all beginning with illuminations of a knight facing a dragon. And this was the beginning of Arioli’s quest to reconstruct a roman that had been forgotten and ignored by everybody – a quest that took him ten years (and in the documentary he doesn’t hide that he ended up feeling himself a lot within Ségurant’s character who is also locked in an impossible quest).

I: Birth of king, birth of myth

The first quarter of the documentary or so is focused on Arioli’s first step in his quest for Ségurant: Great-Britain of course! However, slight spoiler alert, Arioli didn’t find anything there – and so the documentary spends a bit more time speaking about king Arthur than Ségurant, though it does fill in with various other extracts of Ségurant’s story.

Arioli’s first step was of course the National Library of Wales, where the most ancient resources about king Arthur are kept, and where old Celtic languages and traditions are still very much alive, or at least perfectly preserved. The documentary has Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan presenting the audience with the oldest record of the name Arthur in Welsh literature – if not in European literature as a whole. The “Y Gododdin”, where one of the characters described is explicitly compared to Arthur in negative, “even though he was not Arthur”. The Y Gododdin is extremely hard to date, though it is very likely it was written in the 7th century – and all in all, it proves that Arthur was known of Welsh folks at the time, probably throughout oral poems sung by bards, and already existed as a “good warrior” or “ideal leader” figure.

From there, we jump to a brief history lesson. Great-Britain used to be the province of the Roman Empire known as Britannia – and when the Romans left, it became the land of the Britons (in French we call them “Bretons” which is quite ironic because “Breton” is also the name of the inhabitants of the Britany region of France – Bretagne. This is why Great-Britain is called Great-Britain, the Britany of France was the “Little-Britain”, and this is also why the Britain-myth of Arthur spreads itself across both England and France – but anyway). However, ever since the 5th century, Great-Britain had fallen into social and political instability, as two Germanic tribes had invaded the lands: the Angles and the Saxons. In the year 600, the Angles and the Saxons were occupying two-thirds of Great-Britain, while the Britons had been pushed towards the most hostile lands – Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. This era was a harsh, cruel and dark world, something that the Y Gododdin perfectly translates – and thus it makes sense that the figure of Arthur would appear in such situation, as the mythical hero of the Briton resistance against the Anglo-Saxons.

However we had to wait until a Latin work of the 12th century for Arthur’s fate to finally be tied to the history of the kings of England: Geoffrey of Monmouth, a Welsh bishop, wrote for the king of England of the time the “Historia Regum Britanniae”, “History of the Kings of Britain”, in which we find the first complete biography of Arthur as a king – twenty pages or so about “the most noble king of the Britons”. Geoffrey’s record was a mix of real and imagination, weaving together fictional tales with historical resources – it seems Geoffrey tried to make Arthur “more real” by including him into the actual History with a big H, and it is thanks to him that we have the legend of Arthur as we know it today ; even though his Arthur was a “proto-Arthur”, without any knight or Round Table. The tale begins in Cornwall, at Tintagel, where Arthur was conceived: one night, Uther Pendragon, with the help of Merlin, took the shape of the Duke of Cornwall to enter in his castle and sleep with his wife Igraine. This was how Arthur was born.

The documentary then has some presentations of the archeological work on Tintagel – filled with enigmatic and mysterious ruins. The current archeological research, and a scientific project in 2018, allowed for the discovery of proof that the area was occupied as early as 410, and then all the way to the 9th and 10th century, maybe even the years 1000. There are many elements indicating that Tintagel was inhabited during the post-Roman times when Arthur was supposed to have lived: post-Roman glass, and various fragments of pottery coming from Greece or Turkey and other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea – overall the area clearly was heavily influenced by Mediterranean commerce and cultures. Couple that with the fact that we have the ruins of more than a hundred buildings built solidly with the stone of the island – that is to say more buildings than what London used to have during the same era – and with the fact that there are scribe-performed inscriptions for various families and third parties (meaning people were important or rich enough to buy a scribe to write things for them)… All of this proves that Tintagel was important, wealthy and connected, and so while it does not prove Arthur did exist, it proves that a royal court might have existed at Tintagel – and that Geoffrey of Monmouth probably selected Tintagel as the place of birth of Arthur because he precisely knew of how ancient and famous the area was, through a long oral tradition.

2: After birth, death

The next area visited by the documentary is Glastonbury. “On a Somerset hill formerly surrounded by swamps and bogs”, medieval tradition used to localize the fabulous island of Avalon – where Arthur, mortally wounded by his son Mordred, was taken by fairies. Healed there, he ever since rests under the hill, and will, the story says, return in the future to save the Britons when they need it the most… More interestingly fifty years after Monmouth’s writings, the actual grave of king Arthur was supposedly discovered in the cemetery of the abbey of Glastonbury, and can still be visited today. It is said that in 1191, the monks of the abbey were digging a large pit in their cemetery, 12 feet deep, when they find a rough wooden coffin with a great lead cross on which were written “Here lies king Arthur, on the island of Avalon”. Now, you might wonder, why were monks digging a pit in their cemetery? Sounds suspicious… Well it is said that Henry II was the one who told the monks that, if they dug in their cemetery, they might find “something interesting”… Why would Henry II order a research for the grave of king Arthur? Very simple – a political move. Henry II was a Plantagenet king, aka part of a Norman bloodline, from Normandy, and the House of Plantagenet had gained control of their territory through wars. The Plantagenet was a dynasty that won large chunks of territory through battles (or through marriage – Henri II married Aliénor d’Aquitaine in 1152, which allowed him to extend his empire so that it ended up covering not just all of Great-Britain but also three quarters of France). But as a result, the Plantagenet House had to actually “justify” themselves, prove their legitimacy – prove that they were not just ruling because they were conquerers that had beaten or seduced everybody. They needed to tie themselves to Briton traditions, to link themselves to the legends of Britain – and the “discovery” of king Arthur’s tomb was part of this political plan. And it was a huge success – Glastonbury became famous, and so did king Arthur, who went from a mere Briton war-chief that maybe existed, to a true legend and symbol of English royalty.

However, so far, there are no traces of Ségurant in the Welsh tradition, and here we get our second extract of Ségurant’s roman, which actually seems to be the beginning of his adventures.

Ségurant comes from a fictional island (or at least going by a fictional name): l’île Non-Sachante. There Ségurant le Brun was knighted on the day of the Pentecost by his own grandfather. There was great merriment and great joy, and after the party, Ségurant openly declared he wanted to see the court of king Arthur and all the great wonders in it that everybody kept talking about. He claimed he would go to Winchester – and thus it leads to the invitation mentioned above. Yep, he decided that the best way to go see king Arthur’s court and his wonders was to basically challenge the king and his knights…

3: No place at the Round Table

Of course, the next step of the documentary is Winchester, former capital of Saxon England. Some traditions claim that it was at Winchester that Camelot was located, king Arthur’s castle and the capital of his Royaume de Logres, Kingdom of Logres. Logres itself being actually clearly the dream of a land rebuilt and given back to the Britons, once all the Germanic invaders are kicked out.

The documentary goes to Winchester Castle, built by William the Conqueror, and takes a look at the famous “Round Table” kept within its Great Hall – a table on which are written the name of 24 Arthurian knights, with a painting of king Arthur at the center… Above the rose of the Tudors. Because, that’s the thing everybody knows – while the Round Table itself was built in the 13th century and presented as an “Arthurian relic”, it was repainted in the shape it is today during the 16th century, by Henry the Eight (you know, the wife-killer), who used it as yet another political tool to impose and legitimize the rule of the Tudor line – and he wasn’t subtle about it, since he had Arthur’s face painted to look like his… On this table you find the names of many of the famous Arthurian knights: Galahad, Lancelot of the Lake, Gawain, Perceval, Lionel, Mordred, Tristan, the Knight with the Ill-Fitting Coat… They were organized according to a hierarchy (despite the very principle of the table being there was no hierarchy): at the top are the most famous and well-known knights, with their own stories and quests, such as Galahad, Lancelot of Gawain. At the bottom are the less famous ones: Lucan, Palamedes, Lamorak, Bors de Ganis…

And Ségurant is, of course, absent. Which can be baffling when you consider what the story about Ségurant actually says…

NEW EXTRACT! We are on the field of Winchester. All the tents are prepared for the greatest tournament Logres ever knew. The tent of Ségurant is very easy to spot, because there is a precious stone at the top, that shines day and knight, constantly emitting light as if it was a flaming torch. In front of king Arthur, all the bravest and most courageous knights of the Round Table appear and joust between them: Lancelot and Gawain are explicitly named. Suddenly, Ségurant appears and defies them all in combat! One by one, the knights of the Round Table battle with Ségurant – but all their spears break themselves onto his shield, and in the end, no knight wants to defy him, realizing they could not possibly defeat him. And in the audience, a rumor start spreading… “For sure, it will be him, the knight who will find the Holy Grail!”

So we have a knight who managed to defeat all the knights of the Round Table, in front of king Arthur, and yet nobody talks about him? But as the documentary reminds the audience – the Winchester Round Table only contains knights that the British tradition is familiar with. There many Arthurian knights with their own story and quests, such as Erec or Yvain the Knight of the Lion, who are absent from it… Because they are part of the French tradition, and thus less popular if not frankly ignored by England (a specific mention goes to Erec who was only translated very recently into English apparently, and for centuries and centuries stayed unknown in the English-speaking world).

Anyway – the conclusion of this first part of the documentary is simple. Ségurant is not from Great-Britain, he is not British nor Welsh, and so his origins lie somewhere else.

ADDENDUM

In the first part of this documentary, they stay quite vague and allusive about the story of Ségurant (because the documentary is obviously about the quest and research behind the reconstruction of the roman, not about what the roman contains in every little details). So to flesh out a bit the various extracts above I will use some information from the very summary Wikipedia page about this recently rediscovered knight (I didn’t had the time to get my hands on the book yet).

In the version that is the “main” one reconstructed by Arioli and that is the basis for the documentary’s retelling, soon before being knighted, Ségurant had proved his worth by performing a successful “lion hunt” onto the Ile Non-Sachante. Said island is actually said to have originally been a wild and deserted island onto which his grand-father, Galehaut le Brun, and his grand-father’s brother, Hector le Brun, had arrived after a shipwreck – they had taken the sea to flee an usurper on the throne of Logres named Vertiger (it seems to be a variation of Vortigern?). Galehaut le Brun had a son, Hector le Jeune (Hector the Young), Ségurant’s father. However, unlike the documentary which presents Ségurant as immediately wishing to see Camelot and defy its knights as soon as he is knighted, the Wikipedia page explains there is apparently a missing episode between the two events: in the roman, Ségurant originally leave the Ile Non-Sachante to defeat his uncle (also named Galehaut, like his grandfather) on the mainland. After beating his uncle at jousting, rumors of his various feats and exploits reached Camelot, and it was king Arthur himself who decided to organize a tournament in Ségurant’s honor at Winchester, so that the Knights of the Round Table could admire Ségurant’s exploits.

The fact that the documentary presents a version of the story when the Knights of the Round Table are already in search for the Holy Grail when Ségurant arrives at Winchester is quite interesting because according to the Wikipedia article, Ségurant’s name is mentioned in a separate text (a late 15th century armorial) as one of the knights of the Round Table who was present “when they took the vow of undergoing the quest of the Holy Grail, on Pentecost Day”. The same armorial then goes on to add more elements about Ségurant’s character. Here, instead of being the son of “Hector the Young”, he is son of “Hector le Brun” (so the whole family is “Brown” then), and this title is explained by the color of his hair, which is actually of a brown so dark it is almost black. Ségurant is described here as a very tall man, “almost a giant”, and to answer this enormous height, he has an incredible and powerful strength, coupled with a great appetite making him eat like ten people. But he is actually a peaceful, gentle soul, as well as a lone wolf not very social. He also is said to have a beautiful face, and to be “well-proportioned” in body. A final element of this armorial, which is the most interesting when compared to the main story given by the documentary (where the dragon comes afterward) – in this armorial, Ségurant is actually said to have killed a dragon BEFORE being knighted, a “hideous and terrible” dragon, and this is why his coast of arms depict a black dragon with a green tongue over a gold background.

Again, this all comes from an armorial kept at the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal – which has a small biography and drawing of Ségurant over one page (used to illustrate the French Wikipedia article). It is apparently not in the “roman” that Arioli reconstructed – especially since in the comic book adaptation, and the children-illustrated-novel adaptations, not only is Ségurant depicted as of regular size, but he is also BLOND out of all things…

As for the name of the island Ségurant comes from, “l’île Non-Sachante”, it is quite a strange name that means “The Island Not-Knowing”, “The Unknowing island”, “The island that does not know”. This is quite interesting because, on one side it seems to evoke how this is an island not known by regular folks – this wild, uncharted, unmapped island on which Ségurant’s family ended up, and from which this mysterious all-powerful knight comes from (and you’ll see that the fact nobody knows Ségurant’s island is very important). But there is also the fact that the adjective “Sachante” is clearly at the female form, to match the female word “île”, “island”, meaning it is the island that does not “know”. And given it is supposed to be this wild place without civilization, it seems to evoke how the island doesn’t know of the rest of the world, or doesn’t know of humanity. (Again I am not sure, I haven’t got the book yet, I am just making basic theories and hypothetic reading based on the info I found)

#ségurant#segurant#the knight of the dragon#le chevalier au dragon#arthurian myth#arthuriana#arthurian literature#arthurian legend#king arthur#arthurian romance

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

Pyon and Kurapika interacting is so interesting as well because Pyon is a Paleograph Hunter which is described as a Hunter who specializes in learning and translating ancient and lost languages. So she would be VERY interested in learning Kurtish from him but I'm not sure how interested he would be in teaching her.

OMG IVE ACTUALLY THOUGHT ABOUT THIS BEFORE. I'd really love to do something with the idea I'm just not sure I'm a good enough writer for a comic about it 😭 I have ideas though!!!!!! Just less confident in my ability to write dialogue for a more serious interaction

#really at a when youre skills dont match your vision impass#sorry for such a rambly answer lmao#this idea just scratches my brain really good

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have been kindly informed that 417 semicolons is too many semicolons for 118 pages of thesis

...

Y'know, I normally don't edit my academic bullfuckery much because I'm usually cutting it way the fuck too close for that and while I'm very happy that my unmedicated-turbo-ADHD ass actually managed to get the thesis done with enough time to spare to have TWO long-suffering friends* read over it, I'm also currently switching out about 250 semicolons for alternative means of punctuation and discovering all-new spheres of boredom.

Almost done, though. ALMOST. I'll finish whacking semicolons today, tomorrow I'll get the last round of edits in, and then it'll be off to printing on Friday. Which is good, because as much as I genuinely enjoyed writing the thing, I'm about ready to be done with it for now.

*and one father, who went from "are you sure this is scientific enough? it seems so… comprehensible" to "how on god's green earth do you live like that" real fast as soon as he got out of the introduction and into the paleographic weeds, lmao

#thesis hell#half my social circle is poking fun at my punctuation abuse lmao#The problem is that I write like I think#welcome to my internal monologue where everything is connected and full stops do not exist

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

All right, y'all. I'm instituting Scorpion Sundays. Every Sunday I'm going to make a post rating one of the scorpions from the original effortpost, until we get through the whole list. In the meantime, I'll keep posting any scorpions other people send me (or tag me in) on other days -- I'll just schedule any of those I get on the soonest day that doesn't already have a scorpion.

I'm trying to do this in an organized fashion -- I have a spreadsheet and everything. It looks like this:

Anyway, I want to start with this one. I know there are two scorpions in it, but I'm not splitting them up because they're friends. Plus they're getting the same rating.

This is from Harley MS 3244, which the British Library refers to as a "theological miscellany" and has fully digitized. (Link here.) The bestiary section is apparently titled "Liber de Natura Bestiarum" and begins on f.36r. These scorpions are on f.64r.

The reason I'm doing this one first is because I made an error in my initial post. I said, describing this image, "A scorpion is definitely either a mouse or a fish. Either way it has six legs." However, as keen-eyed readers may have noted, this description is inaccurate: the "fish" has seven visible legs. (I'm assuming the legs are the colored rectangles and that the artist didn't just draw a series of stick-legs then blob some color on top of them.) So either these two have different numbers of legs or this version of the scorpion actually has twelve legs -- since the drawing depicts it from the right side, the left legs are hidden behind the right legs, and the "fish" seems to have seven legs because it's stepping slightly forwards and we can see the front left leg.

I guess it's also possible, based on the illustration, that these have no legs and are just perched on top of some sort of rugose stalk like sea anemones. I'm going to give the artist the benefit of the doubt and go with the twelve-legs theory, since that gets them closest to correct.

Also, you have to respect an artist who draws two of the same animal visibly different from each other, right next to each other in the same little box. "Do scorpions have ears? Dunno, this one does and that one doesn't." Is it sexual dimorphism? Different stages in the life cycle? I'd try and work out the answer from the text, but the text looks like this:

Even if my Latin was decent, I don't have the paleographic skills to decipher that. Also, considering that this is the manuscript with four illustrations of scorpions (five if you count the two animals in this illustration separately), no two of which look like the same animal, I'm not willing to assume that the depictions have strong textual support.

So, points.

Small Scuttling Beaſtie? ✔

Pincers? ✘

Exoskeleton or Shell? ✘

Visible Stinger? ✘

Limbs? 12

Now. I think y'all can guess what I think of the vibes of these things. They're tiny and cute. I would pet one and feed it treats. 5/5.

They barely dodge the "identifiable real-world animal" penalty, though. If the one on the left had been drawn with four legs, it would get -1 for being just a regular mouse -- which would then incur a second -1 penalty for being a mammal. But the leg situation is what it is, so they keep their points.

Total points:

6.8 / 10

The leg and ear situations remain ambiguous.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fictober 2023 #7

Prompt #7 - "Do you recognize this?"

Fanfiction: Good Omens

Rating: G

Warnings: None

Pairing: Ineffable Husbands/Aziracrow

Other Notes: In which they clean the bookshop, and Aziraphale finds something he'd almost forgotten. 467 words!

Crowley had finally convinced Aziraphale to do something about at least some of the clutter in the bookshop— using the reasoning, of course, that while it might keep the customers away, it also made it harder for the angel himself to find things. This argument had the benefit of being true, and Aziraphale agreed, resulting in the pair of them spending the day amidst clouds of dust, stacks of books that hadn’t been disturbed in who knows how long, and attempting to decipher handwriting on old scrolls and ledgers that would have made the best of paleographers cringe.

At the moment, Aziraphale was tackling an old desk on the circular balcony that had been piled high with books, bric-a-brac, and various literary paraphernalia for decades. At one point it had been his primary desk, positioned to overlook the front door, but this had led to the impression of being welcoming to those who wished to purchase books, and he’d abandoned it. Aziraphale was making quite good headway, and the desk now contained only a single layer of various stuff. He exhaled with a contented “ha!” before reaching out at random to pick up an object.

Crowley, who had been attacking a dangerously unstable bookcase nearby, leaned around it at the sound of Aziraphale’s satisfied noise, feather duster in hand. His lighthearted tease died on his lips as he saw the angel cradling something in a posture that he seemed to remember, with a look of deep sadness on his face.

“Angel?” Crowley asked, sliding out from behind the bookcase and heading towards the desk, “What’ve you got there?” Aziraphale looked up, and showed Crowley the object: an old glass wide-mouthed bottle, with a grisly-looking object inside.

“Do you recognize this?” Crowley peered at it for a moment before it came back to him.

“Oh, yes! That’s from good old Mister Dalrymple’s house of medical horrors, isn’t it. You went back for that? What of earth for?” Aziraphale returned to tenderly cradling to jar, and sank onto the tall stool beside the desk. He stroked the glass gently with one finger, all the details of the tumor inside returning to his memory from the many hours he had spent staring at it at this very desk.

“As a reminder,” he said in a low voice, “that I am frequently wrong and do not know best.” Aziraphale looked up at Crowley, and his lip trembled. The demon strode to his side and put a hand on his shoulder, squeezing it comfortingly.

“Come on, Angel. Let’s find him a new place in the window downstairs. I think there’s a sunny spot on the sill above your desk currently occupied by a horrible ceramic Pekingese.” At once Aziraphale’s expression transformed into one of horrified protestation.

“Oh, but I love that dog!”

#fictober23#fictober#good omens#gomens#ineffable husbands#aziracrow#aziraphale#crowley#fanfic#fanfiction

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Devotion to the Holy Face

THE NAME "(J)ESU(S) NAZARENE" FOUND ON THE SHROUD

A Paris-based organization CIERT, the International Center for the Study of the Shroud, found writing on the cloth. Below and to sides of the chin, there are three regular lines where no imprint is present. When the official photographs of the Shroud were divided into tens of thousands of squares, each square was given an optical density and was put into a visualization program, some letters gradually began to appear. They were in Latin and Greek: under the chin was written “Jesus” and on one side “Nazarene”.

This was possible because the Romans employed an Exactor Mortis whose task was to make sure a condemned man was dead. After examination of the corpse, the Exactor Mortis would use a cloth with glue to write a person’s name on the face. Where these strips were drawn, the face was not affected by the process that made the imprint.

A recent study by French scientist Thierry Castex has revealed that on the shroud are traces of words in Aramaic.

Barbara Frale, an Italian paleographer at the Vatican archives, told Vatican Radio on July 26 2009 that her own studies suggest the letters on the shroud were written more than 1,800 years ago. She says in a a bulky, 392-page volume called La Sindone di Gesù Nazareno that she used computer-enhanced images of the shroud to decipher faintly written words in Greek, Latin and Aramaic scattered across the cloth. She asserts that the words include the name "(J)esu(s) Nazarene" — or Jesus of Nazareth — in Greek. She also believes that Jesus’ death certificate read: “Jesus Nazarene. Found guilty (of inciting people to revolt). Put to death in the year 16 of Tiberius. Taken down at the ninth hour.”

Note on the 3D image:

Thierry Castex is a French geophysicist specializing in seismic processing for a big oil company. He started working on the Shroud in 2009 especially focused on the 3D attributes. His specialized imaging software produced a most astonishing view of the frontal image of the Shroud.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mesha Stele, a three-foot-tall black basalt monument dating to nearly 3,000 years ago, bears a 34-line inscription in Moabite, a language closely related to ancient Hebrew—the longest such engraving ever found in the area of modern-day Israel and Jordan. In 1868, an amateur archaeologist named Charles Clermont-Ganneau was serving as a translator for the French Consulate in Jerusalem when he heard about this mysterious inscribed monument lying exposed in the sands of Dhiban, east of the Jordan River. No one had yet deciphered its inscription, and Clermont-Ganneau dispatched three Arab emissaries to the site with special instructions. They laid wet paper over the stone and tapped it gently into the engraved letters, which created a mirror-image impression of the markings on the paper, what’s known as a “squeeze” copy.

But Clermont-Ganneau had misread the delicate political balance among rival Bedouin clans, sending members of one tribe into the territory of another—and with designs on a valuable relic no less. The Bedouin grew wary of their visitors’ intentions. Angry words turned threatening. Fearing for his life, the party’s leader made a break for it and was stabbed in the leg with a spear. Another man leaped into the hole where the stone lay and yanked up the wet paper copy, accidentally tearing it to pieces. He shoved the torn fragments into his robe and took off on his horse, finally delivering the shredded squeeze to Clermont-Ganneau.

Afterward, the amateur archaeologist, who would become an eminent scholar and a member of the Institut de France, tried to negotiate with the Bedouin to acquire the stone, but his interest, coupled with offers from other international bidders, further irked the tribesmen; they built a bonfire around the stone and repeatedly doused it with cold water until it broke apart. Then they scattered the pieces. Clermont-Ganneau, relying on the tattered squeeze, did his best to transcribe and translate the stele’s inscription. The result had profound implications for our understanding of biblical history.

The stone, Clermont-Ganneau found, held a victory inscription written in the name of King Mesha of Moab, who ruled in the ninth century B.C. in what is now Jordan. The text describes his blood-soaked victory against the neighboring kingdom of Israel, and the story it told turned out to match parts of the Hebrew Bible, in particular events described in the Book of Kings. It was the first contemporaneous account of a biblical story ever discovered outside the Bible itself—evidence that at least some of the Bible’s stories had actually taken place.

In time, Clermont-Ganneau collected 57 shards from the stele and, returning to France, made plaster casts of each—including the one Langlois now held in his hand—rearranging them like puzzle pieces as he worked out where each of the fragments fit. Then, satisfied he’d solved the puzzle, he “rebuilt” the stele with the original pieces he’d collected and a black filler that he inscribed with his transcription. But large sections of the original monument were still missing or in extremely poor condition. Thus certain mysteries about the text persist to this day—and scholars have been trying to produce an authoritative transcription ever since.

The end of line 31 has proved particularly thorny. Paleographers have proposed various readings for this badly damaged verse. Part of the original inscription remains, and part is Clermont-Ganneau’s reconstruction. What’s visible is the letter bet, then a gap about two letters long, where the stone was destroyed, followed by two more letters, a vav and then, less clearly, a dalet.

In 1992, André Lemaire, Langlois’ mentor at the Sorbonne, suggested that the verse mentioned “Beit David,” the House of David—an apparent reference to the Bible’s most famous monarch. If the reading was correct, the Mesha Stele did not just offer corroborating evidence for events described in the Book of Kings; it also provided perhaps the most compelling evidence yet for King David as a historical figure, whose existence would have been recorded by none other than Israel’s Moabite enemies. The following year, a stele uncovered in Israel also seemed to mention the House of David, lending Lemaire’s theory further credence.

Over the next decade, some scholars adopted Lemaire’s reconstruction, but not everyone was convinced. A few years ago, Langlois, along with a group of American biblical scholars and Lemaire, visited the Louvre, where the reconstructed stele has been on display for more than a century. They took dozens of high-resolution digital photographs of the monument while shining light on certain sections from a wide variety of angles, a technique known as Reflectance Transformation Imaging, or RTI. The Americans were working on a project about the development of the Hebrew alphabet; Langlois thought the images might allow him to weigh in on the King David controversy. But watching the photographs on a computer screen in the moments they were taken, Langlois didn’t see anything of note. “I was not very hopeful, frankly—especially regarding the Beit David line. It was so sad. I thought, ‘The stone is definitively broken, and the inscription is gone.’”

It took several weeks to process the digital images. When they arrived, Langlois began playing with the light settings on his computer, then layered the images on top of each other using a texture-mapping software to create a single, interactive, 3D image—probably the most accurate rendering of the Mesha Stele ever made.

And when he turned his attention to line 31, something tiny jumped off the screen: a small dot. “I’d been looking at this specific part of the stone for days, the image was imprinted in my eyes,” he told me. “If you have this mental image, and then something new shows up that wasn’t there before, there’s some kind of shock—it’s like you don’t believe what you see.”

In some ancient Semitic inscriptions, including elsewhere on the Mesha Stele, a small engraved dot signified the end of a word. “So now these missing letters have to end with vav and dalet,” he told me, naming the last two letters of the Hebrew spelling of “David.”

Langlois reread the scholarly literature to see if anyone had written about the dot—but, he said, no one had. Then, using the pencil on his iPad Pro to imitate the monument’s script, he tested every reconstruction previously proposed for line 31. Taking into account the meaning of the sentences that come before and after this line, as well as traces of other letters visible on RTI renderings the group had made of Clermont-Ganneau’s squeeze copy, Langlois concluded that his teacher was right: The damaged line of the Mesha Stele did, almost certainly, refer to King David. “I really tried hard to come up with another reading,” Langlois told me. “But all of the other readings don’t make any sense.”

In the sometimes contentious world of biblical archaeology, the finding was hailed by some scholars and rejected by others. Short of locating the missing pieces of the stele miraculously intact, there may be no way to definitively prove the reading one way or another. For many people, though, Langlois’ evidence was as close as we might get to resolving the debate. But that hasn’t stopped him from inviting competing interpretations. Last year, Matthieu Richelle, an epigrapher who also studied under Lemaire, wrote a paper arguing, among other things, that Langlois’ dot could just be an anomaly in the stone. He presented his findings at a biblical studies conference in a session organized by Langlois himself. “This says something about how open-minded he is,” Richelle told me.

— How an Unorthodox Scholar Uses Technology to Expose Biblical Forgeries

#chanan tigay#michael langlois#how an unorthodox scholar uses technology to expose biblical forgeries#history#religion#christianity#judaism#languages#linguistics#translation#palaeography#museums#archaeology#technology#digital technology#bible#torah#israel#jordan#bedouin#moab#biblical hebrew#moabite language#mesha stele#charles simon clermont-ganneau#king mesha#andré lemaire#king david#matthieu richelle

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

the very sad reality of living in a world that is opening up to the prospect of AI substituting everything it shouldnt is really getting to me at the point it hurts the most:

i follow, on twitter, a researcher of technology in japan that developed a program that will, one day, help me so so much in my research. she made this program to help identify characters in cursive archaic japanese, which is absolutely amazing from a perspective of the western application of paleography methods will never be able to let or help me understand a single line of text in japanese manuscripts, something that most japanese paleographs have problems with to this day

this WILL, one day, make or break my research, when i get to that point. BUT. this researcher is also supporting machine learning for AI created art. which, as an artist and a human being, im absolutely against.

so. inside of me are two wolves. one with the future of their research on the line. the other with their actual work being affected already.

i hate this reality

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who or What is the Ark of the Covenant?

Eli Kittim

The Ark of the Covenant was a gold-plated wooden chest that housed the two tablets of the covenant (Heb. 9:4). Jewish folklore holds that the ark of the covenant disappeared sometime around 586 B.C. when the Babylonian empire destroyed the temple in Jerusalem. Throughout the centuries, many writers, novelists, ufologists, and religious authors have invented two kinds of wild and adventurous stories about the ark of the covenant. They either talk about fearless treasure-hunters, archaeologists, and paleographers who went hunting for the Lost Ark of the Covenant, or about ancient alien civilizations that made contact with humans in prehistoric times. This has led some authors to the startling conclusion that the ark of the covenant may have been part of a highly advanced ancient-alien technology. But the Biblical data do not support such outrageous and outlandish conclusions.

From a Biblical standpoint, both the “ark of the covenant” and “Noah’s Ark” are symbols that represent salvation in the death of the Messiah. Isaiah 53:5 reads thusly:

he was pierced for our transgressions;

he was crushed for our iniquities;

upon him was the chastisement that

brought us peace, and with his wounds we

are healed.

We can also call it the covenant of salvation based on the atoning death of Christ (Heb. 9:17). If you pay close attention to the biblical symbols and details, you’ll notice that both Noah’s ark and the ark of the covenant represent some type of casket, which signifies the atoning death of the Messiah (that saves humanity). Christ’s covenant is based on his death. Without Christ’s death there is no salvation. That’s what ultimately redeems humanity from death and hell, and allows for resurrection and glorification to occur. Christ, then, is the ark of the covenant, also represented by Noah’s ark (which saves a few faithful humans who believe in God). The caskets are of different sizes. The smaller casket (the ark of the covenant) could only carry one person (the Messiah), whereas the larger one (Noah’s Ark) can accommodate all of humanity (symbolizing those who are baptized into Christ’s death). According to the Book “After the Flood,” by Bill Cooper, “The Hebrew word for ark, tebah, may be related to the Egyptian word db't, = ‘coffin.’ “ Romans 6:3 declares:

Do you not know that all of us who have

been baptized into Christ Jesus were

baptized into his death?

In other words, it’s not Christ’s incarnation but rather his death that saves humanity. All those who follow him and are baptized into his death are saved!

How is Christ the “ark of the covenant”? Christ is the Word of God (Jn 1:1), the Logos, or the Law of God (the Torah)! That’s why the ark of the covenant doesn’t dwell on earth but in heaven. Rev 11:19 reads:

Then God’s temple in heaven was opened,

and the ark of his covenant was seen within

his temple. There were flashes of lightning,

rumblings, peals of thunder, an earthquake,

and heavy hail.

Who dwells within God’s throne-room, within God’s temple, and is represented by the ark of the covenant? Answer: Jesus Christ! A similar scenario takes place in Revelation 21:2-3:

And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem,

coming down out of heaven from God,

prepared as a bride adorned for her

husband. And I heard a loud voice from the

throne saying, ‘Behold, the dwelling place of

God is with man. He will dwell with them,

and they will be his people, and God himself

will be with them as their God.’

Notice that the terms “God” and “the dwelling place of God” are used interchangeably. In other words, the metaphors of the dwelling place, the tent of meeting (ἡ σκηνὴ τοῦ θεοῦ; i.e. the tabernacle), the temple and its sacrificial system, as well as the ark of the covenant, all represent God and signify the blood of the covenant or the blood of the lamb (1 Pet. 1:19; Rev. 7:14; 12:11)! Christ is not only the mediator between God and man (1 Tim. 2:5), but also the high priest who offers up his own life for the salvation of humanity (Heb. 7:17). According to Acts 4:12, there is “no other name under heaven given among men by which we must be saved”: not Moses, or Muhammad, or Buddha, or Krishna, or Confucius, or Allah, or Yahweh. According to Philippians 2:10-11:

at the name of Jesus every knee should

bow, in heaven and on earth and under the

earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus

Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the

Father.

Therefore, he who is within the throne-room of God, and “among the people,” is none other than the Second person of the Trinity, Jesus Christ, who “will dwell with them” forevermore (Rev. 21:3). It’s a throwback to Leviticus, which prophesied the incarnation of God, but which the Jews misunderstood and misinterpreted. Leviticus 26:12:

I will be ever present in your midst: I will be

your God, and you shall be My people.

Compare Revelation 21.3:

He will dwell with them, and they will be his

people, and God himself will be with them

as their God.

#ark of the covenant#atonementtheology#noahsark#messiah#Christsdeath#covenant#ufology#elikittim#τομικροβιβλιοτηςαποκαλυψης#ark#ancient civilizations#ancient aliens#extraterrestrial life#law of god#the little book of revelation#Logos#ΚΙΒΩΤΟΣΤΟΥΝΩΕ#ηκιβωτόςτηςδιαθήκης#mediator#torah#MessiahbenJoseph#word of god#jesus christ#salvation#ελικιτίμ#coffin#ΚΙΒΩΤΟΣ#incarnation#casket#highpriest

2 notes

·

View notes