#overdiagnosis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Die Zukunft der Prostatakrebsfälle: Eine alarmierende Verdopplung bis 2040 | www.ceboz.com

Die Anzahl der Prostatakrebsdiagnosen wird sich bis 2040 voraussichtlich verdoppeln, insbesondere in ärmeren Ländern. Erfahren Sie mehr über diese besorgniserregende Entwicklung.

0 notes

Text

sometimes i question if i rly have npd or if im just overthinking it and then i remember that i show literally Every sign of it & it explains me better than most of my Actual Diagnoses

#npd#cluster b#am i gonna seek a diagnosis?#no bc i dont want my therapist to think im a bad person cus ya know.... stigma n shit#not that shes been ableist at all this whole time i just get nervous cus npd is So Stigmatised#plus she said that im clearly overdiagnosed and she doesnt want to add to my evergrowing list of issues#rather to just get better & to keep in mind that overdiagnosis is a bigg sign of being misdiagnosed#so like we're aware that im probs misdiagnosed butttttt im scared to tell her im 99.99999% sure i have npd#i thought it was bpd for a little while but it just didnt add up very cleanly#but once i started researching npd i was like O_O thats me#bug talks

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guysss adjusting your personality or your mental state for different situations and social groups isn't the same thing as having DID. Please I'm begging you to get info on mental disorders from somewhere other than social media

#self overdiagnosis of did online is getting way too common!#and diagnosing others! cut that shit out!#shoebox speaks

0 notes

Text

Unveiling the Truth: Breast Cancer Overdiagnosis Among Women Over

Understanding Breast Cancer Overdiagnosis: A Comprehensive Insight Breast cancer stands as a significant concern for women across all age groups, with increased prominence as women reach their 70s and beyond. Recent years have witnessed mounting evidence of breast cancer overdiagnosis within this demographic, sparking critical debates about the efficacy and appropriateness of screening…

View On WordPress

#Age-specific screening#Breast cancer overdiagnosis#Cancer awareness#Elderly breast health#Health disparities#Healthcare decisions#Medical interventions#Screening guidelines#Shared decision-making#Women over 70

0 notes

Text

these tags annoyed me to be honest

1. PCOS is a bad point of comparison because despite the name, diagnosis is not *supposed to be* done on the primary basis of finding cysts in the ovaries; these are common and not inherently of concern. instead, the more indicative biomarker is the hormone test (high levels of testosterone *throughout the menstrual period*, with corresponding disruption to the expected/typical fluctuations in estrogen/progesterone) but often diagnosis is done more on the basis of a physical exam ('exam') confirming characteristics such as hairiness or adiposity. this absolutely DOES result in PCOS overdiagnosis for some demographics; while a real biological condition, PCOS is also a load-bearing diagnostic term in the enforcement of very specific standards of (white) femininity and its use also frequently masks, for example, the frequency of hypothalamic amenorrhea (HA) secondary to chronic energy deficiency (as in anorexia), which doctors are loathe to diagnose because they view weight loss as prima facie good

2. the reason it matters that psychiatric diagnoses do not have a 'biology' is not because every disease must have a single specific biomarker; it is correct that some do not. however, the way patient complaints are sifted into categories labelled 'psychiatric' versus '(otherwise) medical' begins essentially with determining whether the distress is 'physical' or 'mental'. in other words, in the case of, say, the chronic fatigue syndrome (famously, lacking a known specific biomarker), the symptoms being investigated by the non-psychiatrist physician are still physical (PEM; mast cell dysregulation; pain; etc) whereas a diagnosis of depression may be accompanied by, but requires no, physical symptoms or presentation. the psychiatric claim that its diagnoses have biological causes and correlates is specifically a claim about the role of neurobiology in the causation of affective states; thus, the comparison to physical complaints is meaningless here

3. this person goes on to claim that depressives do in fact share, though not universally, certain biomarkers such as mitochondrial dysregulations. such claims typically come from various imaging studies plagued with systemic problems in the selection and definition of patient populations as well as the subjectivity of result interpretation and analysis. these claims are not well supported and typically rely on circular selection and definition of patient populations

4. speaking philosophically, it is in fact often correct to challenge the notion that a physical 'disease' chronically lacking a specific biomarker is indeed a disease, in any sense besides the colloquial one. that is, diseases that cannot be correlated with one cause or presentation are often better understood as 'syndromes', which is to say, as a taxonomical heuristic that is likely grouping together multiple disparate physical (anatomical, physiological, functional, &c) problems with multiple disparate causes. this is almost certainly the case for chronic fatigue syndrome, for example. this is a philosophical distinction that matters for research and understanding, and does not mean or imply anything to minimise or contradict the patient experience of the syndrome or symptoms. it matters because, for instance, CFS triggered by the epstein-barr virus may indeed turn out to have different disease mechanisms to CFS triggered by, say, covid-19, or may have different specific mechanisms when running in certain families, and so on. distinguishing these much more specific presentations, and possibly distinct diseases, from the current discursive schema of the overlying syndrome is potentially very good for patients, who likely have different needs and treatments to one another despite currently all sharing the same label in their charts

5. which goes back to an overlying point, which is that (despite frequent defensiveness to the contrary), whether or not something is a disease does not inherently tell us anything about its reality, its severity, its cause, the moral status of its sufferers, &c

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have a post or posts with information about the basics of anti-psychiatry? I’m curious, but I know little about it and Tumblr search is awful.

Yep! Here are some resource roundups that other awesome people have compiled:

And then here's some stuff I've written:

Thanks! I love infodumping about antipsychiatry!

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

wait people on t can grow prostate tissue?!! i didnt know that can i learn more about that

Yep!! Here's some studies about it:

As far as I know there's no information yet on what this functionally changes (like if there's any change in sensation), if anything at all, but its cool & euphoric to know that there's a good chance you have your own prostatic tissue!

It's also just another example of how the idea that sex is immutable is laughable. Literally all it takes is a change in hormone levels and suddenly your body is like "oh we're doing this now? okay!" No matter how transphobes feel, the science doesn't lie: human bodies love transsexualizing

428 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved on our archive

Scientists and doctors somehow: "Wow this is really widespread! We should make up a different definition to make the numbers of this problem smaller!"

Holy shit... I'm so tired...

By Dr. Sanchari Sinha Dutta, Ph.D.

New research highlights the need for a more specific definition of long-COVID, as nearly one in five SARS-CoV-2 negative patients also reported long-term symptoms, raising concerns about overdiagnosis.

A study published in the journal Nature Communications provides an overview of post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) symptoms among emergency department patients who tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

Background The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly burdened global healthcare and economic systems, with more than 775 million reported infections worldwide. A large proportion of COVID-19 survivors are still experiencing persistent or recurring symptoms, which the World Health Organization (WHO) collectively defines as the post-COVID or long-COVID condition.

According to the WHO definition, long-COVID occurs in individuals with a history of suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. The long-COVID symptoms, which an alternative diagnosis cannot explain, typically appear three months after the onset of COVID-19 and last for at least two months.

The WHO has listed more than 50 symptoms of long-COVID, including dyspnea, post-exertional malaise (PEM), anosmia, and cough, among others. However, many of these symptoms could overlap with other viral infections or medical conditions, leading to diagnostic challenges. This makes it difficult to distinguish long-COVID from other health conditions, raising concerns about its diagnostic specificity.

In this study, scientists compared the proportion of emergency department patients who developed WHO-defined long-COVID symptoms between SARS-CoV-2-positive and SARS-CoV-2-negative patients. The study also evaluated whether the WHO’s current definition may be too broad, potentially leading to overdiagnosis in some instances.

Study design The study was conducted on patients registered in the Canadian COVID-19 Emergency Department Rapid Response Network (CCEDRRN), a pan-Canadian collaboration collecting data on patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 in 50 emergency departments in eight provinces.

A total of 6,723 emergency department patients were recruited for the study, of which 58.5% were SARS-CoV-2 positive.

The study's primary outcome was to determine the proportion of patients reporting at least one WHO-defined long-COVID symptom at three months. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients with persistent symptoms at 6 and 12 months.

The study also used mixed-effects multivariable models to identify key risk factors for developing long-COVID symptoms, adjusting for various covariates such as age, sex, comorbidities, and hospital admission. The proportion of patients who were tested for SARS-CoV-2 and met the WHO long-COVID criteria at 6 and 12 months was determined in the study.

Important observations The proportion of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients who reported at least one long-COVID symptom at three months was 38.9%, compared to 20.7% of SARS-CoV-2 negative patients. Among SARS-CoV-2 positive patients, 45.5% of females reported long-COVID symptoms compared to 32.8% of males, indicating a significant gender disparity.

The proportions of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients who reported at least one long-COVID symptom at 6 and 12 months were 38.2% and 33.1%, respectively, compared to 19.5% and 17.3% of SARS-CoV-2 negative patients. The proportions of test-positive and test-negative patients with at least one ongoing long-COVID-consistent symptom at 12 months were 5.8% and 3.4% lower, respectively, than the proportion of symptomatic patients at three months.

The most significant risk factor for reporting long-COVID symptoms at three months was testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 during an emergency department visit (adjusted odds ratio, aOR = 4.42, 95% CI: 3.60–5.43). Other risk factors included ICU admission (aOR = 1.84, 95% CI: 1.34–2.51), female gender (aOR = 1.51, 95% CI: 1.33–1.73), and presenting with loss of taste or smell (aOR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.03–1.85) during the emergency department visit.

Further risk analysis showed that patients reporting "managing well" at baseline were at higher risk of developing long-COVID symptoms than those reporting "fit and well" (aOR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.14–1.52). Notably, a lower risk of symptom development was observed in patients with lower educational backgrounds (aOR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.58–0.97).

Study significance The study finds that more than one-third of emergency department patients with a laboratory-confirmed acute SARS-CoV-2 infection exhibit long-COVID symptoms three months after their initial emergency department visit. The researchers also highlight that one in five patients who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 infection met the WHO criteria for long-COVID, raising concerns about the broad scope of the clinical definition.

A key finding is that the high rate of long-COVID symptoms observed in SARS-CoV-2 negative patients suggests that the current WHO definition may lead to overdiagnosis. The overlap of non-specific symptoms with other conditions presents a challenge for accurately diagnosing long-COVID.

Furthermore, the study finds that about one in five patients with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection also exhibit long-COVID symptoms, complicating distinguishing true long-COVID cases.

A high rate of long-COVID symptoms observed in SARS-CoV-2 negative patients at three months indicates that the development of long-COVID after suspected but not confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection is non-specific and can occur in SARS-CoV-2 naïve patients.

According to the WHO definition, long-COVID is a non-specific syndrome that occurs in many patients who present to the emergency department for an acute illness requiring SARS-CoV-2 testing. However, the current study findings highlight the need for a more specific WHO definition, potentially used in combination with serology or biomarker testing to identify the underlying processes that contribute to the development of long-COVID.

The study finds that SARS-CoV-2 positive patients more frequently exhibit three or more symptoms or certain symptoms, such as loss of taste and smell, dyspnea, and newly persistent cough, as compared to SARS-CoV-2 negative patients.

Existing evidence indicates that most COVID-19 patients experience olfactory symptoms (loss of taste and smell) during the acute infection phase. These symptoms typically subside within one month of infection. However, the persistent presence of olfactory symptoms observed in this study indicates that the presence of these symptoms during acute infection may predict long-COVID.

The scientists highlight the need for future studies to more conclusively understand long-COVID pathophysiology and develop more specific diagnostic criteria.

Study Link: www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-52404-4

#mask up#covid#pandemic#covid 19#wear a mask#public health#coronavirus#sars cov 2#still coviding#wear a respirator

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

So yesterday I saw a great example of the very not subtle culture war the UK media seems intent on waging against ADHD

An article came out called

"278,000 patients on ADHD medication amid overdiagnosis fears" - The Times

Which oh boy we're not off to a good start here but let's see where we're going

and we get

“The increased awareness of mental health problems has been a boon for private doctors and psychologists,” Dr Max Pemberton, a doctor and medical columnist, wrote in a column for the Spectator magazine, also published by The Times.

Hmmm that's oddly convenient you're talking about the comments of someone who writes for a magazine that's also under your umbrella

And well turns out Dr Pemberton here just happened to have published a a piece to The Spectator the day before called

How real is your ADHD?

Which is a compilation of all the classic 'adhd is over diagnosed' things that have no weight to them

Like really?

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Story at-a-glance

The U.S. health care system wastes approximately $800 billion annually, which is nearly 30% of its total expenditure, primarily due to unnecessary services and administrative inefficiencies

Americans pay almost twice as much for health care compared to other developed countries, yet experience worse health outcomes like lower life expectancy

Unnecessary medical services, misaligned financial incentives and profit-driven practices contribute significantly to waste, often prioritizing procedures over patient well-being and effective treatment

Overtreatment, excessive end-of-life care and unnecessary diagnostic procedures like cardiac stents and mammograms are major sources of medical resource overutilization

Proposed reforms include promoting evidence-based medicine, restructuring payment models, improving palliative care, reducing overdiagnosis and shifting focus from quantity of care to quality of patient outcomes

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it's hilarious that children were basically prescribed meth (Ritalin) just because they were energetic in the mid-2000's (overdiagnosis of Restless Leg Syndrome)

Added context: Ritalin is a brand name for Methylphenidate, which is an amphetamine.

Okay, I phrased this poorly. ADHD is a real issue. I was trying to poke fun at (what I consider to be) one of the events that has lead to ADHD becoming marginalized. This is in no way a "Serious" post and I do not actually believe what I am saying here.

#dl's stuff#ritalin#dl talks medication#i was one of those people#actually had ADHD so it was justified

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

curious to hear if other radfems are anti-psychiatry or not. i've seen some who are (and i think it's been getting more popular in recent years) and i can see some of their points--- especially wrt the lack of understanding of women's conditions/the overdiagnosis of 'bpd'/the lack of testing medication on women etc---- but for me personally, i can't function w/o several psychiatric medications. on my meds, i'm a hardworking & successful doctoral student, but off my meds i'd have flunked out of undergrad much less grad school.

#my psych is adjusting my meds rn which is why i'm thinking about this#berry talks#radical feminism#radfem#radfem safe#radfems do touch#radblr#psychiatry#anti psychiatry#mental health#mental illness#radfems do interact#feminism

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

No, I don't think it's as serious as the conclusions people are leaping to. If her cancer was actually "serious," then she would have stated that she is being "actively treated for cancer.

Oh, sorry if I’m a bit lost on this topic, but cancer experiences in my circle has been completely different from this.

I understand the point you are making. However I’ve seen many people saying that we don’t know in what stage the cancer was (I want to imagine it isn’t stage 4 since she wouldn’t have used ‘preventative’ chemo term, she should have used ‘chemotherapy’ term since it would have meant it was already metastasized and preventative wouldn’t be the case) and that she at the end ‘has’ cancer because doctors don’t know if she still has cancer cells on her body, so they will mop op those who remain and the doctors can’t see.

I’ve seen other people talking on their experience and saying that they went to surgery and only after it, it was detected the person has stage 3-4 cancer, is that possible? Or when you have a more advanced cancer it’s more visible with PET scans and other medical tests? Like I don’t understand or can’t comprehend how some doctors can’t see a stage 4 cancer in some organ if that would mean it was already in other organs, or how that works?

[previous ask]

A general overview of cancer (TNM) staging is described in detail here.

T = tumor, which can be staged 0 through 5 (depending upon organ/location). N = lymph node, has it spread to the lymph nodes? What kind of lymph nodes? Sentinel node, group of nodes, several groups of nodes? M = metastasis, yes or no

Specific staging numbers and letters varies based on where the primary tumor is located. Stage 3 or 4 cancer is unquestionably visible on imaging. Stage 4 is usually metastatic cancer, where lymph nodes have been affected. (Except for testicular cancer, which I understand no longer stages up to the number 4 because it has a 99% cure rate in the US.) This is when there are visible lesions on imaging, and surgeons can see tissue abnormalities during surgery with certain kinds of equipment.

Stage 0 is when no actual tumor/mass is found; it is also known as in situ, where abnormal cells in a single tissue layer have not formed a mass.

Consider Kate's statement:

“In January, I underwent major abdominal surgery in London and at the time, it was thought that my condition was non-cancerous. The surgery was successful. However, tests after the operation found cancer had been present. My medical team therefore advised that I should undergo a course of preventative chemotherapy and I am now in the early stages of that treatment."

Masses usually tend to be visible on imaging because radiographic imaging is very good these days. Even though she didn't mention it, she likely had pre-op imaging of some sort, probably a CT scan (with or without contrast). As Dr. Reiner mentioned on CNN, they would have known IF she had any suspect masses in her abdomen prior to surgery. They don't just cut people open and take a look under the hood. If the surgeons noted any abnormalities during the surgery, they would have told Kate after the surgery about those abnormalities and informed her the final results would be determined after testing by pathology.

If she didn't have any visible masses on imaging and if Kate isn't saying that her surgeons informed her of suspicious tissue post-op and they only "found cancer had been present" after pathology, then--based on her own statements--it sounds as if her "cancer" is in situ or stage 0.

As for how other people go through cancer screening or surgery and find out they are stage 3 or 4, well, that gets into how different people's biology grows cancer at different rates.

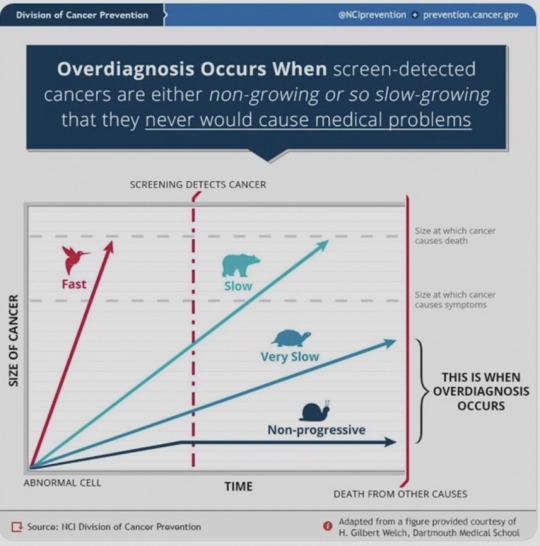

The below image is taken from a screen shot from Vinay Prasad's video on mammography, which I previously posted here. Vinay Prasad is a hematologist-oncologist (cancer doctor).

In this graphic, you see four trajectories with four different animals associated--bird, bear, turtle, snail. There is a red vertical line noting "screening detects cancer." There are two dotted gray lines. The top one notes "size at which cancer causes death" while the one below the bear (and the word "slow") says "size at which cancer causes symptoms."

The four trajectory animals:

Bird: fast growing cancer

Bear: slow growing cancer

Turtle: very slow growing cancer

Snail: non-progressive cancer

The example where you are describing, "I’ve seen other people talking on their experience and saying that they went to surgery and only after it, it was detected the person has stage 3-4 cancer," is a fast growing cancer. A "bird" "in the graphic above. Those kind of cancers are almost impossible to treat. It can be difficult for people with those kind of cancers to make it to the five-year survival rate no matter what kinds of treatments are used.

Charles probably has a "bear" type of cancer. Slow growing but detectable, which is why I suspect he's going to be okay. You can read some urologist comments from reddit here, which I previously posted. It's likely that Charles is being treated for bladder cancer, which was found after his benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) procedure. It's not uncommon to find bladder cancer during BPH procedures.

Kate--based on her own statements--sounds as if she has either a "turtle" or a "snail." If cancer wasn't suspected at all prior to her surgery, then it's likely that what she has currently would pose no immediate threat to her or in the near future. She could have waited six months and been re-evaluated. Instead, it sounds as if she is already napalming her own body with "preventative chemotherapy." A treatment she likely doesn't need but can afford because she has "the best doctors." It sounds more like over-treatment and carries serious risks.

You can read more about over-treatment & over-diagnosis in cancer in the following two articles.

While conventional wisdom holds that early diagnosis is good, H. Gilbert Welch, a professor of medicine and director of the Center for Medicine and the Media at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, views it as a major problem for modern medicine, with myriad social, medical, and economic implications. In his new book, Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health (Beacon Press, 2011), Welch and coauthors Lisa Schwartz and Steven Woloshin write about the hazards of looking too hard for illnesses in healthy people, including additional procedures that carry no benefit, but may cause harm, higher health care costs, and psychological detriments.

Over a decade ago, Welch started looking into the effects of mass screening programs for cancer that have emerged around the globe. These programs take otherwise healthy people and subject them to tests to find out whether they have lumps and bumps that may be malignant. This is different from using ultrasounds or other technologies to diagnose people at risk of a disease or who have symptoms that require investigation. It's the type of preemptive screening that so many celebrities advocate. Welch found something surprising: in many cases, screening wasn't actually helping people or saving lives. The programs were turning healthy people into cancer patients unnecessarily, leading them to needless treatment and hospitalization, creating clubs of "cancer survivors" who actually would have lived even if their cancers were left untouched.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Chloe Cole

Published: May 18, 2023

Yesterday, New York Times reporter Maggie Astor published a hit piece about me in an attempt to undermine my story and the testimonies of other detransitioners. Now that I’ve had some time to process everything more completely, I’d like to address some of the inaccuracies and falsehoods that Astor wrote about me—beginning with the disingenuous title, “How a Few Stories of Regret Fuel the Push to Restrict Gender Transition Care.”

I take issue with Astor’s flagrant use of the word “regret,” which implies a benign mistake like a bad tattoo—something I wasn’t even allowed to get until I turned 18 last year. No, I was a child when I was misinformed and misled by adults, who convinced me to permanently alter my body.

I learned through social media when I was 11 about boys and girls being trapped in the “wrong body”—an impossibility that should never have been “affirmed” by doctors. I was told by health professionals whom I trusted that I had a medical condition that required medical treatment. Not only that, but my parents were emotionally manipulated by being presented with a false dilemma—“would you rather have a dead daughter or a living son?”—despite the fact that suicidality is routinely overexaggerated in trans-identified youth.

Astor relies on the euphemism “transition care” when she means “chemical and surgical sex change services.” This is neither medically necessary nor lifesaving, but rather elective, cosmetic, and experimental.

Astor also flippantly refers to my detransition as “changing course,” implying I merely took a wrong turn instead of having doctors affirm my confusion with experimental medicine. She says I “returned to my female identity,” but being female is not an identity. It is a biological reality that describes half the human population. It is something I never stopped being despite the fact that when I was 13-15, doctors prescribed me puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and surgically removed my breasts to try to mold me into something that superficially resembled a boy.

Astor neglects to mention the vocal European detransitioners and how European medical societies have backed off of “gender-affirming care” after conducting systematic reviews of evidence and finding that the risks outweigh any purported benefits. She also referred to outdated statistics on detransition which include studies on adults rather than the cohort I belong to—adolescents under the “gender-affirming” model of care. These studies also had serious methodological flaws and a high loss to follow up rate.

Another statistic she likely referenced was from a study about detransitioners that specifically excluded detransitioners. Participation in the study was limited only to those who had detransitioned in the past but still identified as trans–in other words, not people like me.

If Astor had researched the topic properly, she would have discovered a recent US-based comprehensive review of medical records that found 30 percent of teens and young adults had discontinued “gender-affirming” hormones after 4 years. Another US study from this year that challenges the notion that detransition is rare found that 29 percent of youth changed their requests for hormone treatment, surgery, or both. And yet another study from a UK primary care practice found that 12.2 percent of those who had started hormonal treatments either detransitioned or documented regret, while the total of 20 percent stopped the treatments for a wider range of reasons. The authors of this study observed that the detransition rate in emerging research brings forth crucial concerns regarding the possibility of “overdiagnosis, overtreatment, or iatrogenic harm,” similar to issues encountered in other areas of medicine.

A 2021 study found that three-quarters of detransitioners did not report their detransition to their providers, thus potentially creating a false impression that they were satisfied with the “care” they received. Norway’s health authorities confirm that detransitioners updating their providers is “not a given.”

It is not true that there are only a few vocal detransitioners in the US. Many have spoken out online, but only a few have the time to travel and testify. It’s not easy to open yourself up to an onslaught of criticism, blame, and hit pieces from the New York Times. It’s not easy to go public with details of your private life.

There have been many instances of detransitioners getting overwhelmed from the response to their story and deactivating their social media accounts. Hundreds more reside in support groups and remain anonymous, not wanting the stigma and negative attention.

Lawmakers shouldn’t have to restrict sex changes to adults, but US-based medical organizations are not doing their job at following the science. If they would conduct systematic reviews of the evidence, they would likely come to the same conclusions as European countries, which have heavily restricted medical interventions for minors and specific psychotherapy as the “first line of treatment” for teens in distress over their bodies.

US-based guidelines ignored an entire body of research that found the majority of children who do not socially or medically transition will no longer experience gender-related distress in adulthood. Instead, most of them grow up to be gay or lesbian adults.

Pioneers of the evidence-based medicine (EBM) movement said the current guidelines for managing gender dysphoria in adolescents in the US are “untrustworthy” and not evidence-based.

Astor took a shot at me for the detransition rally I helped organize in March, but our event was exactly how I planned. My heart hurts every time I see a new detransitioner come out, but soon our numbers will be too large for the New York Times to dismiss as a “few stories of regret.”

Support Chloe Cole by donating here.

#Chloe Cole#detrans#detransition#queer theory#gender ideology#medical transition#medical malpractice#hit piece#affirm or suicide#religion is a mental illness

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I saw this post going around a bit ago saying that it was endo/nondisordered systems that spread support for osddid systems and pushed for more research of traumagenic systems and idk how true that is considering back then, systems were under the MPD dx before they changed the dx in the DSM. MPD was not the same thing as an endo system, but rather most likely either a traumagenic osddid system that didn’t have a proper understanding bc psychologists didn’t get it yet or a person w bpd schema modes that people misunderstood as an osddid system. (Not to say that systems with bpd don’t exist, we’re one such system, but the two are not the same thing). Idk. I feel like it’s in bad faith for endos to say “we’re responsible for why you have research at all btw”. I’m almost positive it’s just regular traumagenic systems who did not have the same knowledge and research we have now pushing for that/fighting for ourselves.

I'm not sure if I'm misreading or misunderstanding, feel free to correct me! There's a few points I'm going to touch on, though, just to cover all the bases. Settle in.

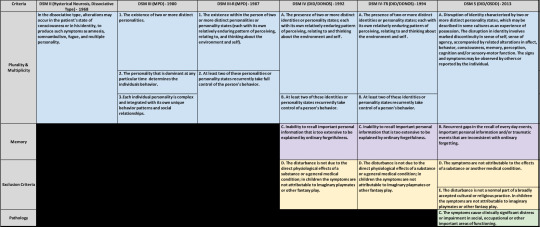

This is actually a really common myth I see from endos-- that MPD either included endogenic systems, and/or that MPD didn't require distress or trauma, and that the change to DID excluded all these systems by... requiring dysfunction? This chart is often used to showcase the differences between the disorders and how the disorders became "more restrictive", excluding systems from the diagnosis.

Which is a weird argument-- If MPD supposedly pathologized all plural experiences by not including distress or trauma in its criteria, wouldn't you hate MPD more than DID? And yet there's a HUGE community of systems that prefer the MPD diagnosis over DID for weird reasons.

However.

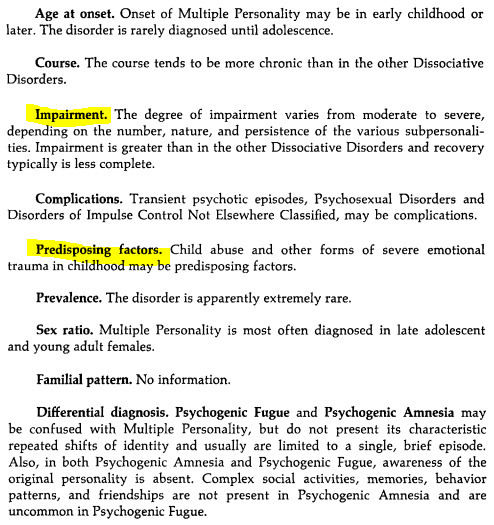

The truth of the matter is that MPD and DID are the exact same disorder, renamed. Even as MPD, it still required trauma and dysfunction for diagnosis (it even still talked about it being a childhood disorder), but even back then, no one read the whole goddamn entry for MPD. From the DSM III.

It's a very frustrating running theme.

The only thing that changed was the name, and it wasn't changed because they didn't believe in the diagnosis. All five were renamed to reflect a better understanding of the mechanisms behind the disorder and dissociation in general. I guess they didn't believe in any of these disorders.

What's really interesting is the changes that were made from the DSM III to the DSM III-TR (PDF). Here's a few choice changes for those on a phone.

(Most interesting to me are the changes to the amnesia criteria)

As you can see, the changes actually significantly expanded the criteria to include more presentations.

The DSM IV is where the name was changed to DID. In less than two years, the DSM IV TR would be released where all of the "cautionary" statements about overdiagnosis of DID would be removed, and we all know what the DSM 5 looks like.

SO.

What were endo/nondisordered systems doing around this time?

Why, being fucking douchebags of course.

The DSM IV was released in 1994, and in 1995, Astaeasweb was started. They were the first major group in this clusterfuck. They were the first to describe "non disordered" plurality, and soon after coined "natural multiplicity".

This was the start of the endogenic movement.

And all they did during that time was call for the boycott of MPD and DID.

"This DID boycott in particular held significance because it caused extreme harm to people with DID/OSDD. This boycott was intrinsically tied to both the anti-psych and natural multiplicity movements. Boycotters often held the belief that DID/OSDD weren’t real and should be removed from diagnostic manuals. Pages on natural and empowered multiplicity tended to go hand-and-hand with boycotting the DID diagnosis as well as boycotting psychiatry or psychology. As a result, this boycott impacted both society’s and psychology’s perceptions of DID/OSDD, and left lasting effects on the DID/OSDD community."

Pluraldeepdive, links and archives in post, check them out, they're an amazing resource.

It was around 1998 that the divide began between "empowered multiples" and "survivor multiples". This is where the real ableism started.

The 2000s introduced the "Healthy Multiplicity" movement. "The purpose of this movement was to establish that plural experiences were not pathological. Participants in this movement often insisted that childhood trauma or abuse could not cause plurality or multiplicity." [x]

This is where we start to see the rise of what is now the endo community, built off the boycott and definitions that were continually being twisted until they lost all meaning.

It went from, "MPD isn't a disorder," to "trauma doesn't define us," to "you don't need trauma at all".

And so it goes, on and on, until today.

A lot of these groups didn't call for more research and they twisted research that was already in use. In fact, in 2003, Pavillion, one of these groups, set their sights on the DID wiki. "The Pavilion organization used a system called action alerts to keep track of various DID-related events or articles. Pavilion members would then coordinately inject controversy and natural multiplicity theories into these spaces."

So in actuality, they were actively fighting and hindering research at the time.

I don't think it matters whether they were actually DID or not-- the point remains that people in these movements had nothing to do with the research we have now, and are in no way responsible for the scientific advancements we've seen.

It's in very bad faith for them to say that.

This has gotten long! I hope I covered everything. Feel free to reach out :)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

thinking about how growing up none of my family knew much about autism or adhd and didn't really know the signs, and then thinking about all the signs i was showing, and how they were responded to as a result of that lack of knowledge. i had a terrible memory as a kid, but only for some things. one thing that really fucked me up was homework. i would do it - my teacher once even admitted i was handing in A+ work - but i couldn't remember to turn it in. the organization methods that were supposed to help just got me more frustrated because they didn't fix the object permanence issue. i was getting lower scores because they were turned in so much later (which is fucked up btw, i get that y'all wanna incentivise getting things in on time but no amount of lateness should turn an A+ into a fucking C, that is ridiculous and you know it, teachers.) and getting AWFUL scores because of all the missing work, and me and my parents couldn't seem to figure out out. and after a while, dad started to assume malice. he knew i could do the work, he knew i had organization tools, and SURELY it was not THAT hard to just turn the darn papers in, so... maybe i was doing it on purpose? for attention? when i look back on our dynamic growing up, i think that very much did effect how he interacted with me. the idea of the troublesome kid likely clouded how he assumed the intentions behind other things. the thing is, i always gave the same reasons. "i forgot" and "i don't know, i'm sorry". and looking back on it.... it's normal to hear that every so often, but when it's becoming an active problem and your kid keeps saying they just forgot, that indicates they are struggling with memory more than they should be. but that idea never occured to any of us, because why would we be watching a healthy 11 year old for memory problems? i know overdiagnosis and overmedication is a problem in some places. i know people get nervous about making every single thing their kid does a Symptom. but please... if this story sounds familiar to you? suggest that they get the kid checked out, specifically with memory issues as a concern. the kid might say they remember just fine; they wouldn't know, they don't know what it's LIKE to remember normally and they don't remember all the times they've forgotten. if you're not sure how that works, please observe the question "do you have a problem wearing socks?". the short answer is, it's very easy to assume your experience is normal and not have it come to mind.

youtube

i will say that in some ways i'm glad i didn't get tested young, because the legal restraints on autistic people are fucking ridiculous and i've made the conscious choice - thankfully respected by my therapist - that i don't want that on my medical record. but i wish we'd known enough to know that i should be looking at resources for what helps kids with adhd. yaknow?

2 notes

·

View notes