#old occitan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Église, chiesa, iglesia, igreja

The English word ecclesiastical is derived from Ancient Greek ekklēsíā, which meant 'assembly, congregation', and later 'church'. You wouldn't say it at first glance, but it's ekklēsíā that became French église, Italian chiesa, Spanish iglesia, Portuguese igreja – and many more. Click the infographic to learn more.

What are semi-learned forms?

In the infographic several words are called semi-learned. What does that mean? You'll learn all about it on my Patreon (750 words, tier 1). If you subscribe to tier 2, you also get an audio file with the reconstructed pronunciations of the Ancient Greek, Latin, and historical Romance words featured in the infographic.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#latin#french#spanish#old french#old spanish#old catalan#catalan#old occitan#occitan#italian#old galician portuguese#portuguese#galician#ancient greek

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

a fun thing about the devil's crown i noticed is how Richard and Bertran call each other by the Old Occitan versions of their names (Richartz, Bertranz, Richard also introduced himself as "Bertranz" when he "adopts" Milo) I thought they were just playing around like poetic licence but was looking through some old docs and lists comparing the old French/occitan names taken from late 12th early 13th century docs and it finally clicked. Fascinating attention to detail, even if idk if that's exactly what they would have used

#the devil's crown#Richard the Lionheart#bertran de born#old occitan#I'm no expert but I'm sure the show writers probably used a similar source

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mal ai ièu, s'anc còr volatge

Vos aic ni·us fui camjairitz,

Ni drutz de negun paratge

Per me non fo encobitz;

//

E s'anc fetz vas me falhida,

Perdon la·us per bona fe

God doom me if I've ever shown

A fickle heart or been untrue,

I have not wanted anyone,

However noble, who was not you.

//

If you have sinned toward me, oh dear,

Then in good faith I pardon you

0 notes

Text

No one: ....

Literally no one:...

Me, a 21st century person sitting on a bus stop scrolling on my smartphone:

🎶Ai vist lo lop, lo rainart, la lèbre

Ai vist lo lop, lo rainart dançar

Ai vist lo lop, lo rainart, la lèbre..🎶

#When a song is like 700 years old and still slaps#Music#Medieval banger#Ai vist lo lop#Occitan#Humans have always been human

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

watching the rai adaptation of the name of the rose. for research purposes

#I’ve actually already seen episode one so: again. berengar is way too old. he and adelmo were The. Same. Age. hello !!!!#also adso’s actor is way too pretty lol#I know they’re going to develop his relationship w the village girl more which I’m still divided about. because I do like the way the book-#-handles it#(also she speaks Occitan!!!!! so cool)#overall i like it til now. will report back later.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My 2019 obsession with Le Roman de Flamenca has been reborn . . . .

#this 13th-century occitan anonymous romance is the kind of story sansa stark (& grrm) would love#it's courtly love#it has a lady in a tower#it has a tourney (but we don't know its end)#it involves lovers meeting in hotsprings#it has it all!!!#i'm obsessed#blame powderpowderblue for introducing me to labour by paris paloma which reminded me of rosalía's el mal querer#rosalía's el mal querer was inspired by le roman de flamenca#but the real origin of this renaissance is sophie turner who is living the same old story of being a woman trapped by an awful man#and then everything comes back to sansa stark

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel that one of the most overlooked aspects of studying the French Revolution is that, in 18th-century France, most people did not speak French. Yes, you read that correctly.

On 26 Prairial, Year II (14 June 1794), Abbé Henri Grégoire (1) stood before the Convention and delivered a report called The Report on the Necessity and Means of Annihilating Dialects and Universalising the Use of the French Language(2). This report, the culmination of a survey initiated four years earlier, sought to assess the state of languages in France. In 1790, Grégoire sent a 43-question survey to 49 informants across the departments, asking questions like: "Is the use of the French language universal in your area?" "Are one or more dialects spoken here?" and "What would be the religious and political impact of completely eradicating this dialect?"

The results were staggering. According to Grégoire's report:

“One can state without exaggeration that at least six million French people, especially in rural areas, do not know the national language; an equal number are more or less incapable of holding a sustained conversation; and, in the final analysis, those who speak it purely do not exceed three million; likely, even fewer write it correctly.” (3)

Considering that France’s population at the time was around 27 million, Grégoire’s assertion that 12 million people could barely hold a conversation in French is astonishing. This effectively meant that about 40% of the population couldn't communicate with the remaining 60%.

Now, it’s worth noting that Grégoire’s survey was heavily biased. His 49 informants (4) were educated men—clergy, lawyers, and doctors—likely sympathetic to his political views. Plus, the survey barely covered regions where dialects were close to standard French (the langue d’oïl areas) and focused heavily on the south and peripheral areas like Brittany, Flanders, and Alsace, where linguistic diversity was high.

Still, even if the numbers were inflated, the takeaway stands: a massive portion of France did not speak Standard French. “But surely,” you might ask, “they could understand each other somewhat, right? How different could those dialects really be?” Well, let’s put it this way: if Barère and Robespierre went to lunch and spoke in their regional dialects—Gascon and Picard, respectively—it wouldn’t be much of a conversation.

The linguistic make-up of France in 1790

The notion that barely anyone spoke French wasn’t new in the 1790s. The Ancien Régime had wrestled with it for centuries. The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, issued in 1539, mandated the use of French in legal proceedings, banning Latin and various dialects. In the 17th and 18th centuries, numerous royal edicts enforced French in newly conquered provinces. The founding of the Académie Française in 1634 furthered this control, as the Académie aimed to standardise French, cementing its status as the kingdom's official language.

Despite these efforts, Grégoire tells us that 40% of the population could barely speak a word of French. So, if they didn’t speak French, what did they speak? Let’s take a look.

In 1790, the old provinces of the Ancien Régime were disbanded, and 83 departments named after mountains and rivers took their place. These 83 departments provide a good illustration of the incredibly diverse linguistic make-up of France.

Langue d’oïl dialects dominated the north and centre, spoken in 44 out of the 83 departments (53%). These included Picard, Norman, Champenois, Burgundian, and others—dialects sharing roots in Old French. In the south, however, the Occitan language group took over, with dialects like Languedocien, Provençal, Gascon, Limousin, and Auvergnat, making up 28 departments (34%).

Beyond these main groups, three departments in Brittany spoke Breton, a Celtic language (4%), while Alsatian and German dialects were prevalent along the eastern border (another 4%). Basque was spoken in Basses-Pyrénées, Catalan in Pyrénées-Orientales, and Corsican in the Corse department.

From a government’s perspective, this was a bit of a nightmare.

Why is linguistic diversity a governmental nightmare?

In one word: communication—or the lack of it. Try running a country when half of it doesn’t know what you’re saying.

Now, in more academic terms...

Standardising a language usually serves two main purposes: functional efficiency and national identity. Functional efficiency is self-evident. Just as with the adoption of the metric system, suppressing linguistic variation was supposed to make communication easier, reducing costly misunderstandings.

That being said, the Revolution, at first, tried to embrace linguistic diversity. After all, Standard French was, frankly, “the King’s French” and thus intrinsically elitist—available only to those who had the money to learn it. In January 1790, the deputy François-Joseph Bouchette proposed that the National Assembly publish decrees in every language spoken across France. His reasoning? “Thus, everyone will be free to read and write in the language they prefer.”

A lovely idea, but it didn’t last long. While they made some headway in translating important decrees, they soon realised that translating everything into every dialect was expensive. On top of that, finding translators for obscure dialects was its own nightmare. And so, the Republic’s brief flirtation with multilingualism was shut down rather unceremoniously.

Now, on to the more fascinating reason for linguistic standardisation: national identity.

Language and Nation

One of the major shifts during the French Revolution was in the concept of nationhood. Today, there are many ideas about what a nation is (personally, I lean towards Benedict Anderson’s definition of a nation as an “imagined community”), but definitions aside, what’s clear is that the Revolution brought a seismic change in the notion of French identity. Under the Ancien Régime, the French nation was defined as a collective that owed allegiance to the king: “One faith, one law, one king.” But after 1789, a nation became something you were meant to want to belong to. That was problematic.

Now, imagine being a peasant in the newly-created department of Vendée. (Hello, Jacques!) Between tending crops and trying to avoid trouble, Jacques hasn’t spent much time pondering his national identity. Vendéen? Well, that’s just a random name some guy in Paris gave his region. French? Unlikely—he has as much in common with Gascons as he does with the English. A subject of the King? He probably couldn’t name which king.

So, what’s left? Jacques is probably thinking about what is around him: family ties and language. It's no coincidence that the ‘brigands’ in the Vendée organised around their parishes— that’s where their identity lay.

The Revolutionary Government knew this. The monarchy had understood it too and managed to use Catholicism to legitimise their rule. The Republic didn't have such a luxury. As such, the revolutionary government found itself with the impossible task of convincing Jacques he was, in fact, French.

How to do that? Step one: ensure Jacques can actually understand them. How to accomplish that? Naturally, by teaching him.

Language Education during the Revolution

Under the Ancien Régime, education varied wildly by class, and literacy rates were abysmal. Most commoners received basic literacy from parish and Jesuit schools, while the wealthy enjoyed private tutors. In 1791, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand (5) presented a report on education to the Constituent Assembly (6), remarking:

“A striking peculiarity of the state from which we have freed ourselves is undoubtedly that the national language, which daily extends its conquests beyond France’s borders, remains inaccessible to so many of its inhabitants." (7)

He then proposed a solution:

“Primary schools will end this inequality: the language of the Constitution and laws will be taught to all; this multitude of corrupt dialects, the last vestige of feudalism, will be compelled to disappear: circumstances demand it." (8)

A sensible plan in theory, and it garnered support from various Assembly members, Condorcet chief among them (which is always a good sign).

But, France went to war with most of Europe in 1792, making linguistic diversity both inconvenient and dangerous. Paranoia grew daily, and ensuring the government’s communications were understood by every citizen became essential. The reverse, ensuring they could understand every citizen, was equally pressing. Since education required time and money—two things the First Republic didn’t have—repression quickly became Plan B.

The War on Patois

This repression of regional languages was driven by more than abstract notions of nation-building; it was a matter of survival. After all, if Jacques the peasant didn’t see himself as French and wasn’t loyal to those shadowy figures in Paris, who would he turn to? The local lord, who spoke his dialect and whose land his family had worked for generations.

Faced with internal and external threats, the revolutionary government viewed linguistic unity as essential to the Republic’s survival. From 1793 onwards, language policy became increasingly repressive, targeting regional dialects as symbols of counter-revolution and federalist resistance. Bertrand Barère spearheaded this campaign, famously saying:

“Federalism and superstition speak Breton; emigration and hatred of the Republic speak German; counter-revolution speaks Italian, and fanaticism speaks Basque. Let us break these instruments of harm and error... Among a free people, the language must be one and the same for all.”

This, combined with Grégoire’s report, led to the Décret du 8 Pluviôse 1794, which mandated French-speaking teachers in every rural commune of departments where Breton, Italian, Basque, and German were the main languages.

Did it work? Hardly. The idea of linguistic standardisation through education was sound in principle, but France was broke, and schools cost money. Spoiler alert: France wouldn’t have a free, secular, and compulsory education system until the 1880s.

What it did accomplish, however, was two centuries of stigmatising patois and their speakers...

Notes

(1) Abbe Henri Grégoire was a French Catholic priest, revolutionary, and politician who championed linguistic and social reforms, notably advocating for the eradication of regional dialects to establish French as the national language during the French Revolution.

(2) "Sur la nécessité et les moyens d’anéantir les patois et d’universaliser l’usage de la langue francaise”

(3)On peut assurer sans exagération qu’au moins six millions de Français, sur-tout dans les campagnes, ignorent la langue nationale ; qu’un nombre égal est à-peu-près incapable de soutenir une conversation suivie ; qu’en dernier résultat, le nombre de ceux qui la parlent purement n’excède pas trois millions ; & probablement le nombre de ceux qui l’écrivent correctement est encore moindre.

(4) And, as someone who has done A LOT of statistics in my lifetime, 49 is not an appropriate sample size for a population of 27 million. At a confidence level of 95% and with a margin of error of 5%, he would need a sample size of 384 people. If he wanted to lower the margin of error at 3%, he would need 1,067. In this case, his margin of error is 14%.

That being said, this is a moot point anyway because the sampled population was not reflective of France, so the confidence level of the sample is much lower than 95%, which means the margin of error is much lower because we implicitly accept that his sample does not reflect the actual population.

(5) Yes. That Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand. It’s always him. He’s everywhere. If he hadn’t died in 1838, he’d probably still be part of Macron’s cabinet. Honestly, he’s probably haunting the Élysée as we speak — clearly the man cannot stay away from politics.

(6) For those new to the French Revolution and the First Republic, we usually refer to two legislative bodies, each with unique roles. The National Assembly (1789): formed by the Third Estate to tackle immediate social and economic issues. It later became the Constituent Assembly, drafting the 1791 Constitution and establishing a constitutional monarchy.

(7) Une singularité frappante de l'état dont nous sommes affranchis est sans doute que la langue nationale, qui chaque jour étendait ses conquêtes au-delà des limites de la France, soit restée au milieu de nous inaccessible à un si grand nombre de ses habitants.

(8) Les écoles primaires mettront fin à cette étrange inégalité : la langue de la Constitution et des lois y sera enseignée à tous ; et cette foule de dialectes corrompus, dernier reste de la féodalité, sera contraint de disparaître : la force des choses le commande

(9) Le fédéralisme et la superstition parlent bas-breton; l’émigration et la haine de la République parlent allemand; la contre révolution parle italien et le fanatisme parle basque. Brisons ces instruments de dommage et d’erreur. .. . La monarchie avait des raisons de ressembler a la tour de Babel; dans la démocratie, laisser les citoyens ignorants de la langue nationale, incapables de contréler le pouvoir, cest trahir la patrie, c'est méconnaitre les bienfaits de l'imprimerie, chaque imprimeur étant un instituteur de langue et de législation. . . . Chez un peuple libre la langue doit étre une et la méme pour tous.

(10) Patois means regional dialect in French.

#frev#french revolution#cps#mapping the cps#robespierre#bertrand barere#language diversity#amateurvoltaire's essay ramblings

764 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to say "grape" in Romance and Germanic languages in Europe

From Latin ūva (“grape”):

uva (Spanish/Castilian)

uva (Asturian)

uva (Italian)

uva (Portuguese)

uga/uba (Aragonese)

uva (Galician)

uva (Judaeo-Spanish)

uva (Piedmontese)

uga (Lombard)

iva (Romansch)

úa (Sardinian)

ùa/ova (Venetian)

auã (Aromanian)

From Latin racēmus ("cluster or bunch of grapes"):

raisin (French)

racina (Sicilian)

raïm (Catalan)

rasim (Occitan)

resim (Franco-Provençal)

roésin (Picard)

roejhén (Walloon)

Unknown origin:

strugure (Romanian)

---------

From Old French grape (cluster of fruit or flowers, bunch of grapes"):

grape (English

grape (Scots)

Literally "wine-berry":

Wiitrybel (Alemannic German)

Weinba/Weinbeer (Upper/Southern German)

vínber (Icelandic)

From Proto-West Germanic *þrūbō ("cluster" or "grape"):

Traube (German)

drue (Danish)

druva (Swedish)

drue (Norwegian)

druif/wijndruif (Dutch)

druif (Afrikaans)

troyb (Yiddish)

Druve/Druuv (Low German)

drúf (West Frisian)

Drauf (Luxembourgish)

#map#maps#cartography#latin america#history#religion#folklore#spain#langblr#romance#germanic#latin#german#english#grape#latina#europe#language#languages#idiomas

495 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since my big Languages and Linguistics MEGA folder post is approaching 200k notes (wow) I am celebrating with some highlights from my collection:

Africa: over 90 languages so far. The Swahili and Amharic resources are pretty decent so far and I'm constantly on the lookout for more languages and more resources.

The Americas: over 100 languages of North America and over 80 languages of Central and South America and the Caribbean. Check out the different varieties for Quechua and my Navajo followers are invited to check out the selection of Navajo books, some of which are apparently rare to come by in print.

Ancient and Medieval Languages: "only" 18 languages so far but I'm pretty pleased with the selection of Latin and Old/Middle English books.

Asia: over 130 languages and I want to highlight the diversity of 16 Arabic dialects covered.

Australia: over 40 languages so far.

Constructed Languages: over a dozen languages, including Hamlet in the original Klingon.

Creoles: two dozen languages and some materials on creole linguistics.

Europe: over 60 languages. I want to highlight the generous donations I have received, including but not limited to Aragonese, Catalan, Occitan and 6 Sámi languages. I also want to highlight the Spanish literature section and a growing collection of World Englishes.

Eurasia: over 25 languages that were classified as Eurasian to avoid discussions whether they belong in Europe or Asia. If you can't find a language in either folder it might be there.

History, Culture, Science etc: Everything not language related but interesting, including a collection of "very short introductions", a growing collection of queer and gender studies books, a lot on horror and monsters, a varied history section (with a hidden compartment of the Aubreyad books ssshhhh), and small collections from everything like ethnobotany to travel guides.

Jewish Languages: 8 languages, a pretty extensive selection of Yiddish textbooks, grammars, dictionaries and literature, as well as several books on Jewish religion, culture and history.

Linguistics: 15 folders and a little bit of everything, including pop linguistics for people who want to get started. You can also find a lot of the books I used during my linguistics degree in several folders, especially the sociolinguistics one.

Literature: I have a collection of classic and modern classic literature, poetry and short stories, with a focus on the over 140 poetry collections from around the world so far.

Polynesia, Micronesia, Melanesia: over 40 languages and I want to highlight the collection for Māori, Cook Islands Māori and Moriori.

Programming Languages: Not often included in these lists but I got some for you (roughly 5)

Sign Languages: over 30 languages and books on sign language histories and Deaf cultures. I want to highlight especially the book on Martha's Vineyard Sign Language and the biography of Laura Redden Searing.

Translation Studies: Everything a translation student needs with a growing audiovisual translation collection

And the best news: the folders are still being updated regularly!

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

hi mr sawyer! i have a couple questions on the eoran languages

do the languages contain grammatical structures?

what are the different languages' real-world basises? for example, i recognize the influence of other celtic languages (i.e. alphabets) on some of the engwithan text here, but the language largely corresponds to irish.

thank you for your time!

Hello. While the Eoran conlangs don't have fully developed grammar, they do borrow elements from real world languages.

Eld Aedyran borrows vocabulary and grammar from Old English and Icelandic.

Glanfathan uses a lot of Cornish vocabulary, but also some Welsh and Irish.

Vailian is a blend of Italian, Occitan, and French but with inflected grammar.

Huana is dominantly Māori but with a few elements of Japanese.

Seki is based on Akkadian.

Engwithan is inspired by Gaulish.

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feuer & feu

The German word Feuer looks a bit like French feu and both mean 'fire'. That's a coincidence, because they're not etymologically related in any way. Feuer, like English fire, comes from West Germanic *fuir, while feu stems from the unrelated Latin word focus, 'hearth', which only later came to mean 'fire'. Focus was borrowed into English and many other languages as focus, its meaning 'focus (of a lens; of an ellipse)' created by Johannes Kepler. My new infographic tells you all about these words.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#latin#french#dutch#german#spanish#proto-germanic#proto-west germanic#frisian#low saxon#old norse#icelandic#occitan#italian#romanian#portuguese#catalan#lingblr#gothic

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

But seriously, what did the people of medieval times listen to?

Let's answer this post :

The short answer is : the things they listened to were FAR MUCH WORSE than anything in our Spotify playlists.

The long answer is :

In the 12th century, southern France knew an exceptional cultural and linguistic wealth. It is in medieval Occitanie that the fin'amor took roots and these stories of courtly love inspired a whole literature of archetypal romances between a queen and a knight, of an inferior rank, who surpasses himself to reach the object of his desires while knowing his romantic goal to be vain and inaccessible. These stories advocating qualities of respect, honour and chastity were very popular at the court of the county of Toulouse.

These love stories were sometimes in the form of poems and always sung by musicians who mastered the local language, the langue d'oc: the troubadours. Very influential in the local nobility, the troubadours were allowed to take certain liberties that in other courts, further north in the country, would be offensive: for example, they could sing a melody proclaiming their love for the queen.

The Occitan ballad "A l'entrada del temps clar" (meaning "at the beginning of the warm season") was written and sung during the 12th century, supposedly in honour of the late Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine. It tells the story of a "queen of April" or "queen of spring" who leaves the king, deemed too old, and prefers him a handsome young man. The song tells that the queen organizes festivities and invites the whole kingdom to dance and eventually a night of general debauchery.

Now, to the actual lyrics:

A l'entrada del temps clar, eya Per jòia recomençar, eya E per jelós irritar, eya Vòl la regina mostrar Qu'el' es si amorosa

In English:

At the beginning of warm weather, indeed To bring back joy, indeed And to anger the jealous, indeed The queen wants to show That she's in love

Who are "the jealous" here? If we stick to the theory saying that the song is about Eleanor, it’s probably the king of France and his court, particularly pious and austere (so not a very conducive place for celebrations and festivities). They struggled to understand and accept the queen’s strong character and the southern Occitan education she had received.

Moving on.

Lo reis i ven d'autra part, eya Per la dança destorbar, eya Que el es en cremetar, eya Que òm no li vòlh emblar La regin' aurilhosa [...] Mais per nïent lo vòl far, eya Qu'ela n'a sonh de vielhart, eya Mais d'un leugièr bachalar, eya Qui ben sapcha solaçar La dòmna saborosa

In English:

Furthermore, the king is coming, indeed To put an end to the dance, indeed Because he is afraid, indeed That another man would steal from him The Queen of April […] But his efforts were in vain, indeed As she doesn’t care about an old man, indeed But rather for an ardent young man, indeed Who knows how to satisfy The savoury lady

Here, the king is openly mocked and ridiculed: he disturbs the festivities and refuses to join it, he is reduced to his old age and his inability to satisfy his wife and nobody cares for him, preferring his more handsome and entertaining rival.

Qui donc la vezés dançar, eya E son gent còrs deportar, eya Ben pògra dir de vertat, eya Qu'el mont non aja sa par La regina joiosa

In English:

Anyone who sees her dance, indeed And show off her beautiful body, indeed Can say without lying, indeed That there is no equal in this world To the merry queen

Here, praise is made on the beauty of the queen but especially the beauty of her body, in a rather licentious way. As said earlier, it is a privilege that only troubadours of Occitanie can indulge without fearing repercussions.

Nonetheless, the King is not the only person that can be subject to critics and mock in medieval times. No one is untouchable, including the church.

"Ai vist lo lop" (I saw the wolf) is a popular song from the 13th century, also of Occitan origin. Here, animals are used to represent real-life people: the wolf is the king, the fox is the churchman and the hare is the tax collector. These three representatives of power are accused of being responsible for the misery of the people.

Ai vist lo lop, lo rainard, la lèbre Ai vist lo lop, lo rainard dancar Totei tres fasiàn lo torn de l’aubre [...] Fasiàn lo torn dau boisson folhat

In English:

I saw the wolf, the fox, the hare I saw the wolf, the fox dancing All three went around the tree I saw the wolf, the fox, the hare All three went around the tree They went around the leafy bush

Seen like this, the lyrics sound rather cryptic. But the next lyrics are extremely explicit:

Aqui triman tota l'annada Pèr se ganhar quauquei soùs Rèn que dins una mesada Ai vist lo lop, lo rainard, la lèbre Nos i fotèm tot pel cuol Ai vist lo lèbre, lo rainard, lo lop

In English:

Here we slave away all year To earn a few pennies And in a month I saw the wolf, the fox, the hare We have it in the ass (meaning that we have nothing left) I saw the hare, the fox, the wolf

And then everything becomes clear. People work hard and the few coins they receive go directly into taxes, first those of the king, then of the church, and other unjust taxes that existed at the time. The wolf, fox and hare will then waste this money on useless parties ("All three went around the tree") and orgies between themselves ("They went around the leafy bush").

So yeah... They definitely can handle your Spotify playlist lol.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In “Memory Voids and Role Reversals,” Palestinian political science professor Dana El Kurd writes of her jarring experience, hearing of the October 7th massacres by Hamas while visiting the Holocaust Tower at the Jewish Museum in Berlin. She notes the historic irony of Holocaust survivors seeking security from future oppression by expelling another people from their homeland by the hundreds of thousands, ghettoizing them in enclaves enforced by military checkpoints, and controlling them with collective punishment.

The irony of a state formed as the “antithesis” to the ghetto using ghettoization as a strategy of control is not lost on Palestinians. This infrastructure of coercion went hand in hand, of course, with ever-present physical violence — imprisonment, home demolitions, air strikes and more.

She quotes Aristide Zolberg’s observation that “formation of a new state can be a ‘refugee-generating process.’”

This is not only true of Palestinians. The Westphalian nation-state, which has been the normative component of the international system since the Treaty of Westphalia, necessarily entails (especially since the post-1789 identification of nationalism with the nation-state) the suppression of ethnic identity to a far greater extent than the expression of any such identity. Every constructed national identity associated with a “State of the X People” has necessarily involved the suppression and homogenization of countless ethnicities present in the territory claimed by that state. At the time of the French Revolution, barely half the “French” population spoke any of the many langue d’oil dialects of northern France, let alone the dialect of the Ile de France (the basis for the official “French” language). The rest spoke Occitan dialects like Provençal, or non-Romance languages like Breton (whose closest living relative is Welsh). The same is true of Catalan, Aragonese, Basque, and Galician in Spain, the low-German languages and now-extinct Wendish in Germany, the non-Javanese ethnicities of Indonesia, and so on. Heads of state issue sonorous pronouncements concerning the “Nigerian People” or “Zimbabwean People,” in reference to multi-ethnic populations whose entire “identity” centers on lines drawn on a map at the Berlin Conference.

When I say official national languages were established through the suppression of their rivals, I mean things like the residential schools of the United States and Canada punishing Native children for using their own languages. Or schools around the world shaming students with signs reading “I Spoke Welsh (or Breton, or Provencal, or Catalan, or Basque, or Ainu, or an African vernacular instead of the English, French, etc., lingua franca). And so on.

And when we consider the range of artificial national identities that were constructed by suppressing other real ethnicities, we can’t forget the “Jewish People” of Israel. Its construction occurred part and parcel with the suppression of diasporic Jewish ethnic identities all over Europe and the Middle East. The “New Jewish” identity constructed by modern Zionism was associated with the artificial revival of Hebrew, which had been almost entirely a liturgical language for 2300 years, as an official national language. And this, in turn, was associated with the suppression — both official and unofficial — of the actually existing Jewish ethnicities associated with the Yiddish, Ladino, and Arabic languages.

The centuries-old languages and cultures of actual Jewish ethnicities throughout Europe were treated as shameful relics of the past, to be submerged and amalgamated into a new artificially constructed Jewish identity centered on the Hebrew language.

Yiddish, the language spoken by the Ashkenazi Jews of Europe — derived from an archaic German dialect and written in the Hebrew alphabet — was stigmatized by Zionist leaders in Palestine and by the early Israeli government. According to Max Weinreich’s History of the Yiddish Language, the “very making of Hebrew into a spoken language derives from the will to separate from the Diaspora.” Diasporic Jewish identities, as viewed by Zionist settlers, were “a cultural morass to be purged.” The “New Jew” was an idealized superhuman construct, almost completely divorced from centuries worth of culture and traditions of actual Jews: “Yiddish began to represent diaspora and feebleness, said linguist Ghil’ad Zuckermann. ‘And Zionists wanted to be Dionysian: wild, strong, muscular and independent.’”

This “contempt for the Diaspora” was “manifested . . . in the fierce campaign against Yiddish in Palestine, which led not only to the banning of Yiddish newspapers and theaters but even to physical attacks against Yiddish speakers.” From the 1920s on, anyone in Palestine with the temerity to publish in Yiddish risked having their printing press destroyed by organizations with names like the “Battalion of the Defenders of the Hebrew Language,” “Organization for the Enforcement of Hebrew,” and “Central Council for the Enforcement of Hebrew.” The showing of the Yiddish-language film Mayn Yidishe Mame (“My Yiddish Mama”), in Tel Aviv in 1930, provoked a riot led by the above-mentioned Battalion. After the foundation of Israel, “every immigrant was required to study Hebrew and often to adopt a Hebrew surname.” In its early days Israel legally prohibited plays and periodicals in the Yiddish language. A recent defender of the early suppression of Yiddish, in the Jerusalem Post, argued that Diasporic languages threatened to “undermine the Zionist project”; in other words, an admission that actually existing ethnic identities threatened an identity manufactured by a nationalist ideology.

If this is true of Yiddish — the native language of the Ashkenazi Jews who dominated the Zionist settlement of Palestine — it’s even more so of the suppression of Jewish ethnic identities outside the dominant Sephardic minority. Golda Meir once dismissed Jews of non-Ashkenazi or non-Yiddish descent as “not Jews.”

Consider the roughly half of the Israeli population comprised of Mizrahi Jews from Middle Eastern communities (including those living in Palestine itself before European settlement). Although the Mizrahim are trotted out as worthy victims when they are convenient for purposes of Israeli propaganda — the majority of them were expelled from Arab countries like Iraq after 1948, in what was an undeniable atrocity — they are treated the rest of the time as an embarrassment or a joke, and have been heavily discriminated against, by the descendants of Ashkenazi settlers. For example former Prime Minister David Ben Gurion described Mizrahim

as lacking even “the most elementary knowledge” and “without a trace of Jewish or human education.” Ben Gurion repeatedly expressed contempt for the culture of the Oriental Jews: “We do not want Israelis to become Arabs. We are in duty bound to fight against the spirit of the Levant, which corrupts individuals and societies, and preserve the authentic Jewish values as they crystallized in the Diaspora.”

Current Prime Minister Netanyahu once joked about a “Mizrahi gene” as his excuse for tardiness. And an Israeli realtor ran a commercial appealing to “there goes the neighborhood” sentiments by depicting a light-skinned family having their Passover celebration disrupted by uncouth Mizrahi neighbors.

Nationalism and the nation-state are the enemies of true ethnicity and culture, and built on their graves. There’s no better illustration of this principle than the Zionist project itself."

-Kevin Carson, "Zionism and the Nation-State: Palestinians Are Not the Only Victims"

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dispatch from Absurdist France

Just so you know we're still living in our own weird Kafka/Ionesco fusion timeline.

Macron's a pompous authoritarian dick and we hate him, so the good people of France started a little informal competition amongst ourselves to see which city or town can fuck his redemption tour of public appearances the most. Besides the usual booing, heckling (shoutout to the two old guys that called him a butthole to his face and called his government corrupt while shaking his hand on live TV yesterday, dudes rock!) etc, we've seen a revival of the ancestral tradition of the casserolade/cacerolazo. Which is basically bringing pots and pans and banging on them to make as much noise as you can to drown out government bullshit, thanks to our Latin brothers and sisters for keeping that one warm for us.

Since he's also very sensitive and his minions the préfets -kinda like a local police chief+mini-governor thing- are very attentive to his feelings, they're taking Measures. This morning he went on a visit in the beautiful, beautiful Languedoc backcountry, my only true love, and the local préfet wasn't about to be outdone in fascist shit by his colleagues.

He invaded the small town of Ganges (4000 souls) with 600 riot cops, not a typo, and illegally used an anti-terror law to forbid the carrying of various things in the municipality, including "portable sound devices".

WHICH, Y'ALL, APPARENTLY INCLUDES FUCKING POTS AND PANS!

Irony and parody are dead, here's the video of popo opening people's bags and seizing saucepans. Also they got manhandeld by a buch of dads with an average of around 0,64 baldspots per scalp and then threw CS gas from 5m away while being downwind.

To top it off, the word for saucepan (casserole) is actually slang for a political scandal, which Macron and his gov are full of (2 or 3 ministers in exercice and his Chief of Staff currently under indictement and 4 or 5 former ones still under indictment or convicted, I lost count)

All of that happened before noon.

I'm done with this clown state, I'll start an Occitan independentist guerilla, this is too stupid.

#upthebaguette#no saucepan is illegal#keep going buddy you're doing great!#south of france#how rambling was that rant seriously#there so much more to the whole thing I didn't even mention#Macron is in his Trump-era#france

587 notes

·

View notes

Text

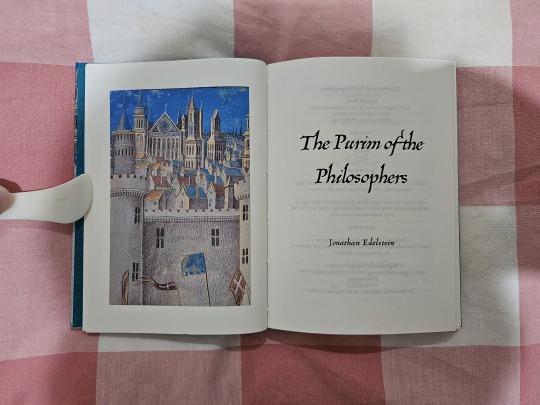

The Purim of the Philosophers by Jonathan Edelstein

Jonathan Edelstein has cropped-up in this blog for several times now, and not without good reason. I knew him from almost a decade ago on an internet forum and his stories - short and long-form - have captivated me by their depth and ingenuity.

So no surprise, I decided to bind yet another short fiction of his. After my first two binds of his work, I actually made a promise to myself to bind two more stories of Jonathan's before the year closes out.

One of them was Of Letters They Are Made, and the other is this: The Purim of the Philosophers.

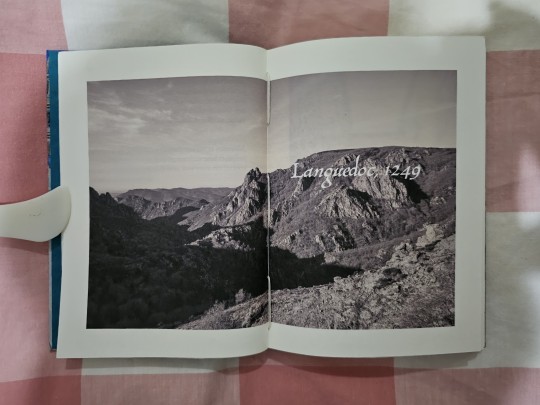

Set in an alternate France where the Albigensian Crusade went unfinished, the Languedoc is its own kingdom, and the political situation is still explosive, The Purim of the Philosophers tells of a Jewish official sent by the Languedoc king to the city of Marseilles to quell tensions between the Jewish communities, all while the French north is gearing up for another war with the south...

Now, while this all sounds fascinating, I doubt I will remember all the background context in 20 years' time. That was why I decided to write a preface to explain the bewildering history of the region, balancing out the need to explain history with the constraints of a small page.

To be honest, I think there is enough historic oddness about southern France to make an original compendium, but I digress.

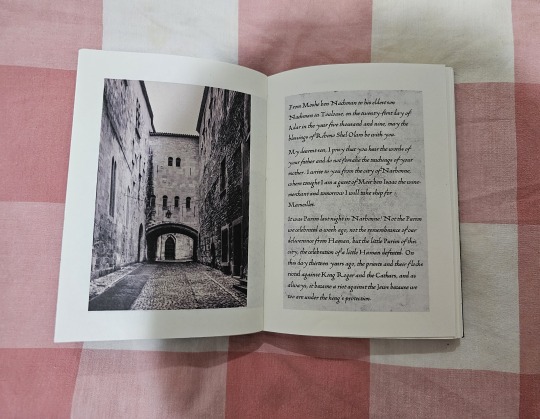

As with previous binds, I have a love for filling in pages with images that capture the feel and mood of the story, and this bind is no exception.

Additionally, parts of the tale is told in the form of letter correspondence between the Jewish official and his son, which I formatted using the 1475 Humanistica Cursiva font. I love the old-timiness of the letters so much that I eventually used it for multiple other things in this book, including the chapter headers and title strip.

The main body text is Alegreya, with a large drop cap of Harrington colored red to give an impression of illuminated manuscripts.

And as always with me, I added-in a comments section to preserve what people thought and discussed of this story when it was first published on alternatehistory.com.

But after all of that, I still feel like giving the background stuff of this tale more justice. So with some consultation from the author, I put-in two more sections denoting the main characters of the story and their real-life counterparts, as well as minor Jewish, French, and Occitan terms that were sprinkled throughout the book.

I have to say, it was quite an experience Googling up which terms meant what to a faith that is not really known to the general public east of India. I think I learned more about Judaism in the last 3 weeks than I ever had in the last 5 years, or even 10!

All in all, this bind was one of the more easier ones to make. I would have made this quicker if not for stuff at work and home delaying progress for a bit. I so wish I could make more than 1-2 books a month, but better to have those 1-2 books than no books at all.

#my bookbinds#bookbinding#fanbinding#jonathan edelstein#The Purim of the Philosophers#alternate history#short story

122 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi!! do you think lestat and louis primarily speak french or english together? did this change over the years for them?

also, i wonder how armand would relate to languages, since he’s had to move between at least four throughout his life (ukrainian, italian, french, english). i know he’s doing his telepathy thing whenever possible, but when he has to speak what does he use and with whom?

i guess this raises a larger question of how language works for vampires with pReTeRnATuRaL AbiLiTy who can read people’s minds, (sometimes) communicate telepathically, and also learn stuff really fast. it’s been a second since i’ve revisited the books, so maybe i’m forgetting something, but in my memory this wasn’t often explicitly described.

thanks <3

Hello!!! I'm sorry this took so long, I'm catching up!

I think Louis and Lestat started off speaking French, but as New Orleans started becoming more American after the Louisiana Purchase, they probably ended up speaking some kind of French-English hybrid. I'm sure by the modern day it's kind of incomprehensible, especially as Lestat picks up new slang that neither of them knows how to use and Louis refuses to stop talking like the cryptkeeper. And neither of them likely spoke standard Old World French to begin with so their shared French dialect is probably a weird love child of 18th century Auvergnat/Occitan and Creole French.

Armand is a little freak so who knows what he has going on, especially since Anne gave him like three canonical accents before she decided where he was from. I think he (along with other vampires of his age and broad experiences) probably speak a very unique form of weird. Because they live so long, my hypothesis is that by a certain age most vampires develop a "vampire accent" that varies by general region and I imagine Armand has this to a pretty extreme degree. I'm sure he's perfectly able to switch between languages based on who he's speaking to, but I think the accent probably carries over.

This is just a headcanon, but I think he would prefer speaking English since he most likely has very negative associations with Ukrainian, Italian, and French (same reason I hc that he doesn't like any of his names). The people he speaks to most in the books are Louis, Daniel, Sybelle, and Benji so English is an easy default anyway. He probably speaks French with Lestat and Italian with Marius and Bianca though.

In general it seems like vampires would have a pretty easy time with languages, like it's not instant but they only have to hear a word or phrase once to know it permanently. I'm not sure if telepathy has to take place in a specific language, but I always assumed that it kind of transcends human speech, like a vampire rosetta stone. Anyone who receives a telepathic message from a vampire will intuitively understand and, if it's another vampire, respond. IF that makes sense. Kind of like how pop culture Thor has Allspeak?

47 notes

·

View notes