#numinous World Series

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#Jo Graham#hand of Isis#this bit is very padme and her handmaidens#cleopatra and her half sisters#heir and handmaidens#historical fiction#fantastical fiction#numinous World Series

0 notes

Text

2024 Book Review #14 – And Put Away Childish Things by Adrian Tchaikovsky

This book I basically came across by chance. Or, well, not exactly chance, but I’d never even heard of it before until I checked what Tchaikovsky books my local library system had copies of and saw it. Which in a sense is a terrible way to come into this – it’s an incredibly dramatic swerve from any of Tchaikovsky’s other stuff that I’ve read – but coming in totally blind pretty much worked, I think. Genuinely very fun read.

The story follows Harry Bodie, a children’s TV presenter facing down middle age with a career that’s never really lived up to expectations. Somewhat desperately, he signs on to a tabloid-ish program about digging into the family tree, hoping to use the residual fame of his grandmother and her fairly famous and successful series of postwar children’s fantasy novels as a career boost. Instead he gets his face rubbed in the fact that his great-grandmother is only recorded as an indigent madwoman, and the famous author was born in a sanitarium. That the famous Underhill stories were, in fact, based in large part on delusions told as childhood fables and family histories.

Somewhat unsurprisingly, the stories turn out to be less delusional than previously reported. Bodie is in quick succession accosted by a faun, approached by a suspicious PI, and kidnapped by a surprisingly moneyed fan-club-cum-occult-coven. Soon enough he’s getting his first taste of Underhill first hand – or, at least, what’s left of it after a century and change of economizing and entropy.

I’m on record as being fairly dismissive about the whole category of ‘stories about stories’, and I guess I need to eat my words a bit because I actually really enjoyed this. To an extent that’s probably just because it doesn’t get too meta – storyland is a work of deliberate artifice, the stories themselves don’t shape the world or do magic, it just generally never tries to get too cute or didactic about it – but still. This is a book where the hero at one point describes his situation as ‘Five Nights at Aslan’s’ so there’s no real principled distinction for me to cut here. One of the main characters is literally a folklorist.

Though, it’s less about stories than one specific story in particular. The unremarkable schlub plucked out of their mundane life and told that they’re special, that they’re the hero or the true heir and possess some inherent numinous essence that makes them the most important person in the world. This is a terribly appealing story, and one Harry feels the lure of very keenly – he’s self-aware enough to say quite clearly that he goes back to the frozen, decaying world full of half-dead monsters less out of morality or rationality than simply because it was a place where he mattered, for good or ill.

It’s probably not reading too deeply into the book’s themes to note that the story is a lure in a fairly literal sense, or that the true heir is destined to ‘save’ the world by being hollowed out and possessed by those who came before them.

Of course as much as this is in conversation with Narnia et al, it owes at least as much to whole genre of ‘what is nostalgic children’s property, but fucked up?’ creepypasta. Fairyland is choked with fungal growths and creepy, staticy not-snow. The scampering, troublemaking faun is miserable and worn out with bad knees. The Best Of All Dogs is a rotting, terrifying hellhound. There’s even a titanic evil scary clown. Aesthetically the book owes far more to r/nosleep than Lewis Carroll.

Harry himself is an absolute delight as a main character. By which I mean he just sucks so bad, but in very mundane and endearing ways. Who among us can not relate on some level to a failing middle-aged actor who always made a point of not trading on his family name but is secretly pretty resentful it hasn’t helped him more? He refuses the call to adventure then decides his life’s kind of shit and he’d rather get stabbed to death by goblins, so he comes crawling back and begs for a second chance. He’s left a glowing magic sword that will defeat all enemies, but it’s stuck in the body of one of his kidnappers so he just runs screaming and it spends the rest of the book in an evidence locker somewhere. I love him.

I really have no idea to what degree it was intentional, but it also does rather muse me that – okay, you know the standard bit of feminist media analysis where male characters are the actors, while female characters are generally walking set decoration and plot devices? It really deeply amuses me that Harry spends the better part of the story as a magical blood bank getting led around or terrified and awaiting rescue, whereas Seitchman (our counterfeit PI/folklorist) repeatedly forces herself into things through obsessive research skills and a complete disregard for her own safety (and at one point an enthusiastic if unpracticed willingness to sword people). Though to be clear this was mostly amusing to me because it was absolutely never highlighted or commented upon.

This is probably the first book I’ve read that’s recent enough to be set during lockdown without really being a COVID novel, if that makes sense? You could set this the year before or the year after without really losing much, and it lacks the ‘this was written in quarantine’ vibe of a lot of books I read last year. But it definitely adds a sense of specificity and timeliness to it that I rather enjoyed.

So yeah, do not open it expecting anything like Children of Time, but good book!

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animation Night 195: több magyar

Back on Sunday. Apologies for confusion with time, but maybe by alternating days to a degree, I can entertain people who are limited to each day...

So first up, thanks for all the sudden appreciation from Hungarian tumblr for Animation Night 157. @70snasagay, @leafthesheep and @critterofthenight, it means a lot!

In that spirit, and since it's been long enough for certain films to get a release beyond film festivals, I'm gonna follow it up tonight with more Hungarian animation! Last time we gave an overview of the Hungarian school of animation with a focus on absolute legend Marcell Jankovics, and there is still much more of the historical story to tell, tonight I'll be focusing on the most recent animated films of Hungary. (Sadly I am limited in time and can't dive quite so in-depth, but the films I have are quite special.)

youtube

If any of you were reading my writeups on the Annecy festival last year, you might recall how taken I was with a film called Four Souls of Coyote (Hungarian: Kojot négy lelke, tho the film is in English). Here's what I wrote back then...

This is a Hungarian movie based on (nonspecifically…) Indigenous stories, with the framing device of the story being told by an old man at the Standing Rock pipeline protests. The bulk of the film is an origin story for the world: Old Man Creator - not the top god in this situation - creates Turtle Island and fills it with creatures. In a dream, he creates Coyote, and mistreats him at once; Coyote, an obligate carnivore in a world that does not yet know death, steals the creation mud and creates humans So most of the film then tells how, through a series of events, Coyote ends up complicating the idyllic scenario by introducing death into the world, and sexual reproduction, and inspiring the creation of lightning and fire before being betrayed by the humans he created, eaten, and on his final life, driven away. It’s a really interesting sort of mythological schema: even Old Man Creator doesn’t know the why of it all, and there’s this kind of idea that a lot of the way things work happened not by design but by mistake (perhaps according to the ineffable design of a higher, more numinous power), and once something is created it’s irrevocably part of the world, so we just have to make do. I have no idea what’s based on mythology and what was created by the Hungarians, but what makes this all work is the incredible animation. This is just a really really strong work of traditional animation, with fantastic colour and compositing to boot. It might genuinely be the best looking film I’ve seen this whole festival so far, which is nuts. There are all sorts of characterful touches in every shot, the magic is presented in a really elegantly straightforward way, and the whole story unfolds with a compelling degree of intricacy and tension, setup and payoff. Coyote, the famous trickster, is certainly the main character of this movie. He’s a fascinating character; arrogant, quick to lie and in love with his own cleverness but also we can see his pride comes from the rough circumstances of his creation, where he’s chewed out by his creator from the get go and everyone pushes him away.

The last arc of the film, which I won't spoil here, is where it really goes hard: bridging the gap from a mythological past to the ugly conflict of modern history and elegantly weaving the Europeans into the story it's telling. It is the moment of Coyote's greatest mistakes, but also the most character development. Absolutely incredible to watch. Kind of devastating! That's the way of it!

youtube

Alongside that, our second act is another flavour of Hungarian film entirely. This is White Plastic Sky, a full-rotoscope scifi film in the fashion of A Scanner Darkly. Its world conceit is that the ecosystem has collapsed, leaving humanity contained in small cities whose oxygen is provided by the ingenious expedient of transforming humans into trees. The main character sees his wife volunteer to become a tree, a decision he refuses to accept, and he pulls all the strings he can to first free her against her wishes, and then as two fugitives, journey to the origin of the tree system to find the scientist who created it. Which is to say: classic high-concept science fiction, with some gorgeous imagery and a fantastic mood.

This film is kind of hell to acquire in the UK. There's no official release, it's not on any pirate sites in usable quality, and in the end the only way I managed to get my hands on it was to VPN into the Czech Republic in order to buy a download using google pay. But I did that! And I found some subs which were only mistimed by 40,700ms. So we can watch this movie too!

Besides that, we have a really cool first-person short film about a fly, an amazing work of background animation. Thanks to a wonderful article by Animation Obsessive (drink), you can read about this film in parallel to another from Yugoslavia. Director Ferenc Rofusz, following in the footsteps of his mentor Jankovics, managed to convince the state it was worth producing, but struggled to find the resources to singlehandedly animate this crazy ambitious project.

There are no characters in Rofusz’s film — instead, the whole screen animates. Where the Zagreb Fly is an exercise in limited animation, this is a frenzy of movement. We take the fly’s perspective as it goes from forest to yard to house, only to be trapped inside with an unseen human. The sound design is anxiety-inducing: the endless buzzing, the footsteps, the human’s swings. We, as the fly, are hunted.

The whole short is available on Youtube, right here:

youtube

There are many more stories to tell about Hungarian animation - honestly Hungary rivals France for the number of interesting films drawn there, an animation tradition unique and all the more remarkable for continuing to today. but for now, I am running late already, and this will have to suffice!

Animation Night 195 will begin very shortly at twitch.tv/canmom - I hope you can join me!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bill Viola

Video artist who melded the material and the spiritual and applied modern technology to Renaissance subjects

In 1957, on a family holiday, Bill Viola fell in a lake. He was six years old. Sixty years later, Viola, who has died aged 73, recalled the event. “I didn’t hold on to my float when I went into the water, and I went right to the bottom,” he said. “I experienced weightlessness and a profound visual sense that I never forgot. It was like a dream and blue and light, and I thought I was in heaven as it was the most beautiful thing I had seen.” And then … “my uncle pulled me out.”

It seemed an unpromising start to an artistic career. However, in 1977 Viola began a series of five works called The Reflecting Pool. Four years out of university, this was his first multipart artwork, its constituent films occupying their maker for three years. In the title piece, a shirtless man – Viola – emerges from a wood, walks toward a pond, makes as if to jump into it and freezes in mid-air. The pool registers his entry nonetheless, its surface rippling as though disturbed; the flying man fades slowly away; and, after seven long minutes, Viola emerges, dripping, from the water and walks back into the woods. The Reflecting Pool drew on the near-drowning of his six-year-old self. It was also classic Viola, its most notable features – slowness, water, a numinous spirituality – recurring in his work of the next half century.

It was the subaqueous blue glow of the screen of a Sony Portapak video camera, donated to his high school in Flushing, New York, that first attracted Viola to the medium. He was raised in the neighbouring lower-middle-class suburb of Queens. It was not, recalled Viola, a cultured household, but his mother, Wynne (nee Lee) “had some ability and sort of taught me how to draw, so when I was three years old I could do pretty good motorboats”. A year before his near death by drowning, a kindergarten finger-painting of a tornado won public praise from his teacher. It was then, Viola said, that he decided to be an artist.

His father, a Pan Am flight attendant turned service manager, had other ideas. Fearing that an art school education would leave his son unemployable, Viola senior insisted that he study for a liberal arts degree at Syracuse, a respected university in upstate New York. “And in saying that,” Viola would admit, “he saved me.”

As luck would have it, Syracuse, in 1970, was among the first universities to promote experimentation in new media. A fellow student had set up a studio where projects could be made using a video camera. Signing up for it, Viola was instantly converted: “Something in my brain said I’d be doing this all my life,” he remembered. He spent the following summer wiring up the university’s new cable TV system, taking a job as a janitor in its technology centre so that he could spend his nights mastering the newfangled colour video system. In 1972, he made his first artwork, Tape I, a study of his own reflection in a mirror. This, too, would be trademark Viola, bewitched by video’s ability simultaneously to see and be seen, but also by his own image. The I in the work’s title was not a Roman numeral but a personal pronoun.

Tape I and works like it were enough to catch the eye of Maria Gloria Bicocchi, whose pioneering Florence studio, ART/TAPES/22, made videos for Arte Povera artists. When Viola took a job there in 1974, he found himself working alongside such giants as Mario Merz and Jannis Kounellis. By 1977, his own reputation in the small but growing world of video art led to his being invited to show his work at La Trobe University in Melbourne, his acceptance encouraged by the offer of free Pan Am flights from his father.

The invitation had come from La Trobe’s director of culture, Kira Perov. The following year, Perov moved to New York to be with Viola, and they married in 1978. They would stay in the house in Long Beach, California, that they moved into three years later, for the rest of their married lives. In 1980-81, the couple spent 18 months in Japan, Viola simultaneously working as the first artist-in-residence at Sony Corporation’s Atsugi laboratories and studying Zen Buddhism.

This melding of the sacred and technologically profane would mark Viola’s work of the next four decades. Viola listed “eastern and western spiritual traditions including Zen Buddhism, Islamic Sufism and Christian mysticism” as influences on his art, although it was the last of these that was the most apparent. At university, he said, he had “hated” the old masters, and proximity to the greatest of them in Florence had not changed that view. It was only with the death of his mother in 1991 that he began to feel the weight of western art history, and to acknowledge it in his own work.

Having struggled with a creative block since the late 1980s, he found that the grief of his mother’s death freed him. Summoned to her side by his father, Viola filmed first the dying woman and then her body lying in an open coffin. This footage would be used in a 54-minute work called The Passing, and then again the following year in the Nantes Triptych, its three screens concurrently showing a woman giving birth, Viola’s dying mother and, in between them, a man submerged in a tank of water.

The first of Viola and Perov’s two sons had been born in 1988. Nantes Triptych was, or appeared to be, a meditation on birth, death and rebirth through baptism. If the subject was traditional, so too was Viola’s use of the triptych form. His references to the old masters would soon become more direct still. In 1995, Viola was chosen to represent the US at the Venice Biennale. One part of the work, Buried Secrets, that he showed in the American pavilion drew openly on a painting by Jacopo da Pontormo of the visitation of the Virgin Mary to her elderly cousin, Elizabeth.

Not surprisingly in these secular times, Viola’s subject matter was not universally popular. The art world was particularly divided. When his videos were shown among the permanent collection of the National Gallery in London in an exhibition called The Passions in 2003, one outraged critic dubbed Viola “a master of overblown, big-budget, crowd-pleasing, tear-jerking hocus-pocus and religiosity”.

The pairing at the Royal Academy in 2019 of his work with drawings by Michelangelo from the Royal Collection drew the barbed comment from the Guardian critic that “Viola’s art is so much of its own time that it is already dated, dead in the water”.

Predictably, he was more popular with the public at large, a survey at a Viola retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris showing that visitors had spent an average of two-and-a-half hours at the exhibition. Churchmen, too, were won over by Viola’s work, particularly those of the Church of England. In 1996, the artist was invited to make a video piece, The Messenger, for Durham Cathedral. In 2014, the first part of a two-part commission called Martyrs and Mary was installed at St Paul’s, the second joining it two years later. The project, thanks to ecclesiastical wrangling, had been a decade in the making. “The church works kind of slow,” remarked Viola, mildly. “But then I also work kind of slow.”

That mildness, and the religiosity of his subjects, may have led critics to underestimate the rigour of his work. Like Viola’s art or not, he was a master of it. His appreciation of the promise – and the threat – of technology was profound. Viola chafed against the primitiveness of early video, seeing each development in the medium as an opportunity to be grasped. The close-up portraits of The Passions series, for example, made use of flatscreen technology almost as it was invented.

By contrast, the binary nature of the modern world bothered him. “The age of computers is a very dangerous one because they work on ‘yes or no’, ‘1 or 0’,” Viola mourned. “There’s no maybe, perhaps or both. And I think this is affecting our consciousness.” The dissemination of video as an art form had not been like the spread of oil painting by the Van Eyck brothers 500 years before, he said, video having appeared everywhere and at once. True to these beliefs, Viola saw no contradiction in treating Renaissance subjects, and a Renaissance belief system, with the latest inventions from Sony. “The two are actually very close,” he said. “I see the digital age as the joining of the material and the spiritual into a yet-to-be-determined whole.”

In 2012, Viola was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s disease. His work after this was increasingly made with the help of Perov, a fact that lent a new poignancy to the themes of memory and loss that often ran through it.

Viola is survived by his wife and their sons, Blake and Andrei, and by his siblings, Andrea and Robert .

🔔 Bill (William John) Viola, video artist, born 25 January 1951; died 12 July 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eight Chants to Reach Yggdrasil

A while back, I wrote a series of poetic chants meant to enter a meditative state as magical practitioner. I recently realized that I would be better served with chants focused on connecting to Yggdrasil, the cosmic tree in Nordic-Germanic mythos, as a means to mentally enter the wider numinous reality. Thus, I worked on a new batch centered around world tree in mind. Some have rhymes and others have alliterations, while a couple break from the pattern of quatrains. I intended to focus on different thematic and symbolic aspects of Yggdrasil.

I walk towards the World Tree

As a pilgrim seeking power, wisdom,

And healing along the heights and the depths.

With sincere respect I receive the gifts.

Like the old volvas and wizards,

Along with shamans of different lands,

Along with Odin and his twin birds,

I bond with the tree as my mind expands.

I gaze upon the greatest tree

Holy wells water the roots.

Deities gather to fulfill their duties.

The branches reach and embrace all.

My ancestors worship at sacrosanct trees.

Gods and kindred join their reality.

A birthright resides within my flesh.

I am ready to approach the powers and be blessed.

Yggdrasil, the cosmic ash, is the key.

Four stags feed on the leaves

Near the top of the World Tree.

Dewdrops that gather on the antlers of Durathor,

Dwalin, Dain, and Duneyr fall

To the rivers flowing within our realm,

Where the kindred wait for human contact.

Yggdrasil grows among the stars,

Deep in the heart of the glittering cosmos.

My mind and heart will travel far

And also find Yggdrasil close.

For now, I leave everyday life,

Abandoning the comforts of common reality.

I find my way through the fertile dark.

Now I approach the magnificent ash.

Through windy nights, Odin hanged,

Thirsting and bleeding, from a massive tree.

Upon revival, he joyfully sang

Runic songs to share with everybody.

#yggdrasil#chants#original verse#original poetry#poetry#verse#pagan#heathenry#heathenism#animism#rhymes#alliterative verse#rhyme#alliteration#world tree

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

With regard to R. Scott Bakker's Second Apocalypse books:

i'd be very interested in hearing why you both really like that series and also think it would be super alienating/what its target audience is

Yeah. So. OK.

The short version is "these are books for philosophy and history nerds, who love dense complicated worldbuilding, and who are lacking a lot of common social/ideological allergies."

They are fantasy books that take ideas seriously, in a way that will appeal to a lot of the people reading this. They're built on top of some really really cool metaphysical premises, and they explore those to the utmost. They do Big Sweep of History better than most fantasy books purporting to do that thing; the first trilogy in the series is essentially about a crusade, of the real Reclaim the Holy Land style, and it does a bang-up job capturing both the grandeur and the grotesquerie entailed in that kind of endeavor.

They have a lot in common with rationalist fiction, in a "descended from a common intellectual ancestor" kind of way, but they do a lot of important things very differently from capital-R Ratfic in a way that I like. They have a much darker moral and cosmological tone, with the gee-whiz take-us-to-the-stars optimism replaced by a kind of profound historical and cosmological horror. They are also, overall, much more literary and just-plain-weird in style. One of our protagonists is basically a rationalist supergenius raised in isolation who's just now encountering the world and learning to bend it to his will, and...well, the process is cool and maybe even overall good (maybe) (very maybe) but it sure is unsettling in basically every conceivable way.

The worldbuilding is also top-notch, in my opinion, not only in terms of depth but in terms of tone and style. It's a big, sprawling setting that feels like it was created by someone who honest-to-God knows how to channel Tolkeinian numinousness and someone who knows and appreciates pulp fantasy and someone who's actually read a goddamn history book.

But.

...look, I don't even know where to start here. Let me just list a grab-bag of things that are true about these books:

In the first trilogy, we have two major POV characters. One of them is a very sweet, angsty, relatable dude who also understands a lot of key facts about the setting history and the magic system. The other is a ruthless sociopath who engages with literally everyone and everything in a purely manipulative way. Guess which one we get to spend hundreds of pages with first, before meeting the other?

The ultimate bad guys of the setting, the Mordor faction, consists of aliens whose culture is built around the idealization of rape. Their hordes of minions, the orc-analogues, are genetically engineered rape monsters.

...there's a lot of conspicuously offputting sex stuff in general, in fact.

Long stretches of the narrative are basically misery porn, in which we get to see close-up just how grindingly awful it is to be part of a crusading army on the march / to be a prostitute in a city through which a crusade is passing / etc.

The metaphysics, which are the conceptual foundation of the series and also its coolest feature, do not get revealed in significant depth until halfway through the third volume. A friend of mine read the series on my recommendation, and kept asking me questions that amounted to "...are you sure these are the books you keep talking about?"

You do not find out until at least six books in whether our sociopathic rationalist supergenius protagonist is essentially benevolent or not. Despite spending an awful lot of time in his head.

Plus, y'know, there's generally a lot of philosophical jawing.

Plus...even I have to admit that, especially starting with the second trilogy, the series starts making a number of unforced errors. (There's a moment where we go back to the Monastery of Rationalism whence our protagonist dude sprang, and we learn a lot more about what went on there, and...sense-making gets sacrificed for shock horror in a big way.)

In sum: there's something to offend just about everyone, deeply. Old-school fantasy lovers will dislike the constant nasty subversions of classic numinous Cool Fantasy Stuff. Contemporary nu-fantasy types will dislike the extent to which the series is about the powerful wreaking their will upon the powerless, the general (extremely deliberate) sexism of the setting, etc. People who are there for the setting will be annoyed by how much is concealed for a very long time; people who are there for the characters will be annoyed by how unlikeable many of the key characters are. Almost everyone will be wigged out by the sloggy unpleasantness, the sexual grossness, or both.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review Conversations with the Tarot:

Bewitching Meditations on Reading the Cards

by Maria DeBlassie

My thoughts…

Tarot cards have always been part of my life and I have never looked at them as something evil or dark. It is quite the opposite. For me, they are a form of inspiration and a tool for self care. I can also appreciate how reading tarot cards is a very personal thing to each individual.

What moved me with this particular tarot book was the author’s explanation about their own personal use of tarot cards. It was the author’s approach and the feeling of talking with a friend. What the tarot means to them and the heartfelt insights for each card. This approach felt real to me, something I could actually apply to my own life.

It feels the world around us has changed and is changing daily since covid. The author addresses this. I felt a close connection to everything I was reading. This book really opened me up to a new way to look at my tarot cards. It also offers a brighter way to envision these times that can feel so bleak.

Conversations with the Tarot has a gentle and welcoming tone that kept me engaged while also teaching me something about tarot. The author makes it clear they are sharing their experience, not instructing. That felt really good and comforting to me. That concept also allowed me breathing room to work with my own personal take on tarot.

Due to lack of space and costs, I usually buy the kindle edition first and then if I really want the book for my collection, I will purchase the book. That is what I’m doing with this title. This book is beautifully written. Easy to enjoy and understand. One I absolutely want to have on hand to work with daily.

Conversations with the Tarot: Bewitching Meditations on Reading the Cards by Maria DeBlassie

Bewitching tarot meditations by bruja and award-winning writer Maria DeBlassie.

One part prose poetry, one part witchy insights, and one part study in learning the tarot, this book explores this mundane divination form for beginners and experts alike.

This cartomancy book was birthed from DeBlassie’s creative tarot studies in which she wrote 78-word prose poems for each of the 78 cards in the deck, using synchronicity, everyday magic, and her budding understanding of tarot symbolism and meanings to craft her tales.

It’s not your basic how-to-read tarot book, but more a how-to begin a conversation with this divination tool. As any tarot reader can tell you, dealing the deck is more than interpreting cards. It’s about building a relationship with this mystic tool and learning how you and the tarot can work together to discover numinous revelations.

This book is a series of proverbial spells. A series of stories. A series of synchronous messages and mystic musings. A journey into learning the tarot. Are you ready to start your adventure?

0 notes

Text

My Favorite 2022 Reads - #6

#6 -- The Thread That Binds by Cedar McCloud

Ohhhh my gosh, okay so Cedar McCloud is an indie artist primarily known for their divination decks like The Numinous Tarot which is how I was introduced to them. But they also write and have started to publish the Eternal Library Series. This first book, The Thread That Binds, was published in 2020 alongside a tie-in oracle deck, The Threadbound Oracle. The deck both features characters from the story and is used within the story -- it’s so cool! Though neither is required to enjoy the other.

I am a huge fan of Cedar’s artwork! I own all three of their published decks and am eagerly awaiting the fourth they’re working on. But I sat on my copy of The Thread That Binds for two years because reading during the pandemic? Just wasn’t working for me. I mentioned I read 42 books last year but that was mostly a big Doctor Who surge in January and a cozy fantasy surge in October-December with nothing in between.

Well, that cozy fantasy surge was jump-started by The Thread That Binds. I’m so glad I finally got my soupy brain to load it up on my Kindle and actually read it, because Cedar is just as good of a writer as they are an artist. This book begins with two protagonists competing for a prestigious apprenticeship at a magical library where they’ll learn to care for the books spelled to last forever and even learn to write and bind their own eternal books. While both get accepted for the apprenticeship, they get thrown in the deep end of library politics when the Head Librarian passes away and their book-binding mentors put their names in the running for the position. Because of course, there’s someone else in the running whose plans for the library’s future are much more nefarious, and of course, it’s not a simple vote that will determine the next Head Librarian, but a much more magical one.

The official summary is far better than mine, but just know it is indeed very cozy and queer and magical and has a really cool and interesting world. It felt like it was written by a peer, which I suppose makes sense given that Cedar is millennial aged and reads cartomancy in a similar way to me (which is one of the reasons I love their decks so much).

Note: Most of the characters use the pronoun ‘e/ey/em’ because their language doesn’t have a concept of gender. I thought a singular letter ‘e’ would get lost in the text, and I would have trouble reading it, but with the Kindle font and spacing, I actually adjusted really quickly. It was far easier to read than the excerpts I had seen previously through newsletters and Patreon posts. (Though, I still have to wonder if capitalizing the ‘E’ like how the pronoun ‘I’ is captialized would make it even easier.... But that’s just me musing.)

In summary, 12/10 would recommend. The Thread That Binds by Cedar McCloud was my 6th favorite read in 2022. And you can learn more about the series and book 2 The Tale That Twines which will be coming to Kickstarter sometime in 2023 in this blog post here.

#my 2022 favorite reads#I should probably make these recommendations shorter so they're easier to read#but I'm going to be brutally honest#I'm primarily writing these for myself so if no one reads them because they're too wordy that's fine#I'm just trying to make original posts again#I'm so out of practice with it that my anxiety thinks it's safer to not share anything anymore#so I'm attempting to change that

0 notes

Note

📨aaaaassssskkkk (it's like a piece of paper floating down from the mail slot, back and forth)

what's your favorite flower?

do you have a best of all time book/movie/game rec?

If you could take a spaceship up to the International Space Station (presuming all training occurs) would you do it?

roller coasters, yes or no?

what's your favorite flower?

OK, for smells alone... I love gardenia and jasmine.

For looks, I like tulips, especially the ones that are like orange red gold. I love certain Dahlias as they are so sculptural. And Ranunculus too - so ruffly. I have geraniums and nasturtiums in my front yard. As a kid, I had a little African violet on my window. I loved its purple color and fuzzy leaves. And my cousin's wedding had stargazer lilies so I am fond of them for the happy memories. And lilies of the valley are like delicate little bells but they don't grow where I am at. (SoCal dessert-ish).

do you have a best of all time book/movie/game rec?

Hmmm... I try and curate books based on taste of the recipient. I have a few that I think generally are good for everyone.

The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell is beautiful, fun, tragic, hopeful, witty, and will stick with you. It's about Jesuits in Space! Making first contact! Language and Translation! Love and devotion! God and Doubt! An agnostic priest? It's complicated!

if someone is at all fannish, I love:

Gideon the Ninth

The Thief / The Queen of Attollia / The King of Attolia by Megan Whalen Turner. Go in unspoiled, do not even read the back covers. They are a perfect experience to unfold. You can only read it for the first time once but ooooo such good. (The first one may seem a bit middle grade but don't let the possibly slow start get you. It's a cracking good book).

Paladin's Grace by T. Kingfisher

Penric and Desdemona Novellas by Lois McMaster Bujold

C. L. Polk - The Midnight Bargain is like a better fantasy Bridgerton

Sharon Shinn - Troubled Water is a fun Mary Sue romance with like astrology. Total treat.

I feel like Melissa Caruso should be read more. Her trilogies have some nimble inventiveness you don't see elsewhere. I love that the required YA love triangle at least all sat and had an honest conversation about polyamory. Decided it didn't work but hey it was on the table. Which was such a surprise!

Oh and the Numinous World books by Jo Graham need to have a resurgence since people went wild for Song of Achilles. I love "Hand of Isis" and "Stealing Fire" in particular. It's like a set of characters reincarnating through history. It's very cool.

More info here: https://www.goodreads.com/series/53677-numinous-world

And here: https://jo-graham.livejournal.com/258739.html

"A couple of people have asked how reincarnation works in the Numinous World. How can Gull be Lydias be Charmian be Elza? How can she remember? How can she forget? What stays constant? Why?

Ok, think back to when you were fifteen. That person was you. But that person was probably very different from you now (unless you're currently sixteen).

Or maybe you've gone through a crisis and rejected the religion you practiced then, or devoutly found a faith you scoffed at then. Whatever your journey, that person you were at fifteen is still you. And so are you now. There's no "which one are you really." You're both equally. Just at different times.

That's Gull/Lydias/Charmian/Elza's experience. Elza was Gull, just as you were that person at fifteen. She was Lydias, just as you were who you were at seventeen. She was Charmian, just as you were who you were at twenty.

Imagine every year as a different life. Ones that are closer together are more alike. How much difference is there between you at fifteen and at seventeen? Gull and Lydias are very alike. They're both quiet, devoted, certain in their loves. They both yearn for grace. They both see beyond the edges of the world. But they have different experiences and they make different choices.

And that's where Michel is in The Emperor's Agent. He's been Agrippa. He's been Hephaistion. He's been Leicester. He remembers the mistakes he made at least in part and he's trying not to make them again. When he says, "I never listen to you," he's right. That was Agrippa's mistake. He didn't listen to Charmian. He didn't ask her what she wanted. He just assumed. He decided for them both and then was blindsided when she didn't want the life he had planned for them. And so now, knowing that, he's trying to make a different decision. He's trying to not have this story be Hand of Isis. He's trying to not have this end with "Was this well done of your lady?" That's his nightmare -- watching her die again. That's his nightmare -- being the destroyer, the one who kills it all. We we see that in the last scene of Hand of Isis with Lucia. She tells him, "Don't do it again." And he promises he won't. In a way, all of the Elza books are the story of how Michel doesn't. And why.

If you could take a spaceship up to the International Space Station (presuming all training occurs) would you do it?

Yes, if medical cleared me. I would so do it. I might cry but I would go. For Science!!

roller coasters, yes or no?

Yes! I love them!

#asks and answers#book recs#Jo Graham#Numinous World Series#C. L. Polk#lois mcmaster bujold#The Sparrow#Mary Doria Russell#Sharon Shinn#Stealing Fire#Lydias of Miletus#Megan Whalen Turner

1 note

·

View note

Photo

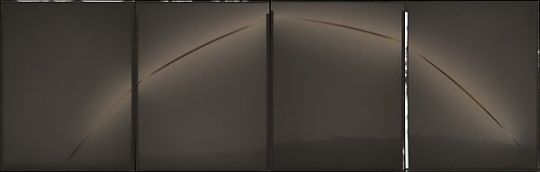

Capturing the Mystic of Natural Phenomena

By Christie Neptune

Abstract.

The 18th century was a pivotal moment within the global history of Astronomy. It was a period marked in the West by scientific enlightenment, discovery, and national competitiveness. Yet, despite the era's advancements, investigative research in astronomy rendered inaccurate singularities that encumbered progress. This essay will examine how the convergence of photography and astronomy in the 19th century led to new developments that advanced fundamental constants, aesthetics, and our understanding of the universe. To that end, I will show how a shift in methodological approach and philosophy engendered a new generation of scientists working across mathematical, cinematographic, and experimental mediums in modern and contemporary times. Finally, the gesture will show how the collision of art and science in the documentation of natural phenomena nuanced the field of photography and astronomy. Can scientific documentation of natural phenomena serve as art and conversely, can art and aesthetics influence scientific discovery?

Capturing the Mystic of Natural Phenomena.

The sun etches itself across light-sensitive paper producing a numinous image of solarization in Chris McCaw's photograph, Sunburned, GSP #166, Mohave/Winter Solstice, (2007, Sunburn Series). The positive gelatin print documents the winter solstice, a natural phenomena highlighting the earth's maximum tilt away from the sun during its orbit. The image is visually alluring and collapses the binaries of art and science. It visualizes the world as it is perceived and, in the same instance, alters such reality through aesthetics, a performativity that transcends. Can McCaw's print serve as a model of analogical reasoning imbued in empirical observation and speculative truth? Can Sunburned, GSP #166, Mohave/Winter Solstice serve as scientific documentation? Conversely, can scientific documentation serve as art?

The emergence of photography in 19th-century astronomy embodied the epistemological tenets of scientific realism. The era generated a series of visually compelling celestial images that illuminated unobserved truths of the universe. It is what Ian Hacking calls the two aims of science: Theory and experiment. "Theories try to say how the world is. Experiment and subsequent technology change the world" (Hacking 31). A shift in methodological approach and philosophy engendered a new generation of scientists working across mathematical, cinematographic, and experimental mediums. Although an interdisciplinary approach in 19th-century astronomy led to alternative observational instruments that advanced the universe's fundamental constants, do the astronomical photographs of research produced during this era meet the criteria for art?

In Capturing The Mystic of Natural Phenomena, I will examine the collision of art and science in Chris McCaw's Sunburned, GSP #166, Mohave/Winter Solstice (2007, Sunburn Series). I will further explore how the singularities of 18th-century Astronomy influence new developments in photography and aesthetics. Finally, the gesture will show how the collision of art and technology in the natural sciences was critical to new knowledge formations that proffered a greater understanding of the world around us.

In an address to the Royal Society in 1716, English Astronomer Edmond Halley formulated a method for measuring the Solar Parallax, the earth's distance from the sun, using the Transit of Venus. His predictions would rally a global quest to capture the Transits of 1761 and 1769 and engender national pride within Britain and British colonies. In British Preparations for Observing the Transit of Venus of 1761, Harry Woolf writes, "Once this was accomplished, other distances in the solar system then known only relative to one another could be computed, and the Newtonian system of the world could be brought closer to completion by the determination of its exact scalar dimensions,"(Woolf 400). The 18th century’s call to define astronomical units of the universe would change the branch of astronomy and conventional methods of scientific observation in the century ahead.

In 1761, John Winthrop, Hollis Professor of Mathematics and Natural philosophy at Harvard College, led an expedition to northeastern Newfoundland to observe the Transit of Venus. Although promising, Winthrop's venture was unsuccessful. It highlighted a global collective of singularities within 18th-century Astronomy. Utilizing the apparatus and other necessaries: an astronomical regulator, hadley's octant with nonis divisions, a refracting telescope with crosshairs, and a reflecting telescope adjusted with cross levels, Winthrop and his two assistants observed the Transit of Venus around the sun. One assistant counted the clock, and the other wrote down observations as Winthrop described it. The process was unexacting. In a written account addressed to the Royal Society, Winthrop reflected on his observations:

"There were but two of their eclipse that could have been visible there while I was on island; and though I watched for both of them, I was disappointed of both by unfavorable weather. Neither was I fortunate enough to get so much as one occultation of a fixed star by the moon though I spared no pains for it. The only observation I could get for this purpose was of the right ascension of the moon, which I endeavoured to find, by comparing with that of a fixed star. But whether any mistake was committed in counting the clock, or in writing down the observations or whether the position of the telescope was disturbed by any accident in the interval between the moon's and stars paffing, I am not able to say. However, as I am sensible that observation is not to be depended on,"(282-283 Winthrop).

Winthrop's observations of the 1761 Transit were part of a collective of disparities obscured by external interference and unreliable instruments. Traditional methodologies of observing the venus transit around the sun employed a persistence of observation and calculations over several hours. The most unstable tool within Winthrop’s scientific observation was the naked eye. Each observer posited a singularity that illuminated the subjective nature of perception. The 18th-century transits highlighted the need for alternative instruments that rendered invariable truths. Could an interdisciplinary approach to astronomy resolve such singularities? The 19th century's approach to astronomy fostered the development of alternative instruments that advanced scientific documentation of natural phenomena. A shift in methodological approach and philosophy engendered a new generation of interdisciplinary astronomers working across “physics, photography, cinematography, pedagogy, and mimetic experimentation” (Canales 587). The emergence of photography in astronomical observations allowed scientists to produce embodied representations of scientific theory. The exactness of form posited through photographic documentation superseded the human eye.

French astronomer Herve Faye advocated for the application of photography in scientific research. He called for the "suppression of the observer," a necessity in astronomical observations. Faye believed "the observer does not intervene with his nervous agitations, anxieties, worries, his impatience, and the illusions of his senses and nervous system." Through photography, "it is nature itself that appears under your eyes"(Canales 597). Could the emergence of new technology and the integration of photography in the field of astronomy answer the call brought forth by Halley at the beginning of the 18th century?

Although a photographic turn in 19th-century astronomy resolved a number of the issues encountered in the previous century, it faced much criticism. Photography's technical limitations in standardization led many scientists to question its efficiency in research. To eliminate observational singularities, astronomers would have to develop new standardization processes to strengthen the precision of documentation. Thus, astronomers in essence would have to become astronomical photographers. For instance:

"During the 1890s, Professional astronomers began to make significant contributions to both the development of photographic instrumentation and the chemistry of photographic materials. They also perfected methods for modifying existing telescopes. Astronomers pioneered in the use of dyes and filters to increase the sensitivity and spectral range of photographic emulsions, and they sought to apply photography to the solution of a number of important problems in astronomical research. " (Lankford 656).

In light of new developments, photography became widely accepted as a reliable instrument of scientific inquiry within the field of astronomy. Canadian-American Astronomer Simon Newcomb's photographic method for measuring the aberration of light contributed towards global efforts in defining the first system of astronomical units. The photographic process employed in Newcomb's observations was unique. "A heliostat tracked the sun and reflected its light through a fixed telescope, where the image was focused onto a photographic glass plate. Another glass, ruled with a grid of lines and a thin vertical wire attached to a plumb bob, immediately in front of the focal place, created lines on the Sun's image" as pictured in the 1882 photographic plate documenting Venus at the midpoint of its transit around the sun (Carter and Carter 47). Utilizing the photograph's scale, he converted linear to angular measurements of the solar parallax. Newcomb used an instrument developed by Joseph Winlock of Harvard College Observatory to calculate his conversions. Newcomb's calculations of the Solar Parallax from a constant of aberration "was adopted internationally at a Paris conference in 1896" (Dick 107). Newcomb's research contributed to ongoing efforts by astronomers to accurately measure the earth's distance from the sun [1]. It proffered observable data that confirmed much of the theories brought to fore by Halley in 1716.

The convergence of photography in 19th-century astronomy highlights the shift in scientific research from a realism of theory towards the realism of entities. Hacking defines this as "a drift away from representing and towards intervening" (Hacking 29). If photographic intervention in astronomy does not contort scientific data but posits a continuity of knowledge, does the aesthetic choices employed within McCaw's photograph fit within the schema of scientific observation?

McCaw's Sunburned, GSP #166, Mohave/Winter Solstice traces the sun's arc in the sky across four sequential exposures on expired light-sensitive paper during the Winter Solstice. The process is laborious and occurs over several hours of observation. The Artist constructs four large format cameras that he positions outdoors in the Mojave desert. In exposures ranging from 15 minutes to 24 hours, MacCaw produces photographic materiality documenting natural phenomena. "As the sun moves in the sky, it literally burns a hole in the fiber of the paper, leaving a physical scar of where the sun has been across the desert sky or abstracted mountain range, and making tangible trajectory of the earth's orbit around the sun in scored markings," (Dea K., Widewalls). In addition, the intensity of the sun's rays produces a positive print that reverses the tonal values embedded within the paper. McCaw's photograph does not distort the science of the solstice. Instead, it serves as a photographic intervention, one that models the sun's angle in the sky during the shortest day of the year. Perhaps elements of aesthetics employed within photography can inform scientific content. Contemporary scientific photographer Felice Frankel addresses this matter in The Art of Scientific Photography:

"By addressing the aesthetic component, you actually add data," contends scientific photographer Felice Frankel. '[The images] also allow you to get the concept without needing to know the language.' The resulting photographs become a legitimate part of the scientific investigation rather than just decorative trophies, she adds. Such images play a significant role in the data collection process and later in communicating the findings" (Peterson, 395).

For example, the sun's scorched mark on light-sensitive paper communicates its intensity and positioning in space during the winter solstice. However, it does not proffer an exactness essential to scientific research, a quantitative numerical representation of the sun's intensity. Although McCaw's photograph does not encapsulate an astronomical unit, it serves as a model of analogical reasoning, generating knowledge in its relations to a more extensive system. In McCaw's Sunburned, GSP #166, Mohave/Winter Solstice, one understands the solstice without knowing the specificity of its functioning. Such is the Artist's intent, visual language communicated through aesthetic, material, and compositional choices. However, can the astronomical photographs of the 19th-century transit observations fit within this schema of art? Singularities evidenced in the 18th-century transits conveyed the limitations of insular thinking devoid of creative intervention. Although the photographic shift in astronomy advanced astronomical knowledge of the universe, can the images produced by astronomers of this time be considered art? Does it employ the fundamental elements of visual language?

Like language, the visual image postulates how one communicates and perceives reality. It is the embodied form of creative integration governed by the fundamental laws of organization:

"It can interpret the new understanding of the physical world and social events because dynamic interrelationships and interpenetrations which are significant of every advanced scientific understanding of today, are intrinsic idioms of contemporary vehicles of visual communication: photography, motion pictures, and television" (Kepes 13).

Thus, visual language mobilizes one to reimagine and take action. It is positioned at the junction of three guiding principles: plastic organization, visual representation, and dynamic iconography. Within the field of attention of Newcomb's Photographic plate, Venus, at the midpoint, is presented as a dark spot superimposed upon the sun, a white circular form ten times its size. A stable relationship of proximity, similarity, and tonal opposites is established within the spatial structure between Venus and the Sun. A black border produces a visible boundary separating the circular forms from their surroundings. The plate is a plastic image that mobilizes our responses beyond the sensory range. "From the perception of sensory patterns, one moves to corresponding structures in emotional and intellectual realms. The experience becomes complete. To reach balance in this wider dimension, the dynamic bases, the spacetime span of the plastic experience must be secured" (Kepes 15). Newcomb's plate is the visual representation of the 1882 transit of Venus, a spacetime event orbiting the sun, and dynamic iconography of the first system of astronomical units. If the plate conveys an aesthetic, a plastic organization of relationships, does Newcomb's photographic plate of Venus at the midpoint of its 1882 transit meet the visual criteria for art?

In 2019, Mia Fineman of The Metropolitan Museum of Art curated an exhibition of astronomical photographs and drawings surveying visual representations of the moon. The exhibit, entitled: Apollo's Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography featured film excerpts and over 300 images and objects conveying the marriage of art and science[2]. Photographs displayed within the exhibition provided "scientific views of the lunar surface, which allowed for a better understanding of the topography of the moon" (Fineman, The Met 2019). What is unique about the exhibition is that it provided the opportunity to explore the relationship between art and science. It examines how scientific documentation of natural phenomena and lunar surfaces influenced speculative fiction and aesthetics in art.

The exhibit features Two Views of the Moon, in Siderius Nuncius (1610), a published drawing of the moon's rugged surface by Galileo. The illustration is from "The Starry Messenger," a catalog of work surveying his recorded observations of the moon over the course of nineteen nights. Gallelio's scientific documentation of the lunar surface inspired the artistic development of speculative fictions that blurred the boundaries between fantasy and fact. Filippo Morghen's Plate 7 (...) , [3] an etched print created using the aquatint process, is a speculative fiction inspired by Gallelio's lunar drawings. The work reimagines life on the moon.

In the print, lunar inhabitants resemble depictions of Native Americans and are surrounded by flora and fauna associated with the Americas. Moon people are shown living in giant pumpkins and hunting oversized possums, the smaller versions of which are indigenous to the New World. The similarities between depictions of these two territories previously unknown to Europeans are no coincidence, and they emphasize the way artists use the moon to reflect the anxieties, preoccupations, and fantasies of the times" (Fineman, The Met 2019).

In Apollo's Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography visual representations of the moon through drawing and photography highlight the growing influence of art and aesthetics on science. Can this dichotomy work inversely? Can art and aesthetics influence scientific experimentation and discovery?

A century before Gallelio's lunar drawings there was Adoration of the Shepherds with Saint Catherine of Alexandria, (1599), an oil painting by Italian Artist, Cigoli. The painting depicts an infantile Christ surrounded by figures beneath the moon's reflective light. Upon closer examination, one can see the details of the moon's rugged surface. The painting blends the study of nature with renaissance aesthetics[4]. "Cigoli had merely happened to portray the moon in a manner that suggested the ashen light before he knew of the existence of the phenomenon, and precisely in the period just before Galileo began to regard it as evidence of the Copernican world system" (Reeves 50). The Adoration of the Shepherds with Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Illustrated the natural phenomena of secondary light long before it was investigated in scientific theory and observation. Thus, one can argue that Cigoli's painting, the embodiment of scientific realism, proffered the ability to describe the world as it perceived and alter such reality in the same instance, influenced the lunar theory of Galileo [5]. Cigoli's Adoration of the Shepherds with Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Galileo's Two Views of the Moon, in Siderius Nuncius, and Filippo Morghen’s Plate 7 (...), exist within an entanglement of representation and intervention. Each work serves as a model of analogical reasoning that posits the continuity of knowledge, both speculative and empirical. Both astronomical photography and photography capturing natural phenomena contain the essential elements of visual language. They are "devices of orientation; a means to measure and organize spatial events. The mastery of nature is intimately connected with the mastery of space; this is visual orientation" (Kepes 14). What links Newcomb's photographic plate of Venus in the midpoint of the 1882 Transit and McCaw's Sunburned, GSP #166, Mohave/Winter Solstice are their visual orientations. Both works convey the mastery of nature and space. Newcomb's plate freezes the orientation of Venus, a small circular form, as it moves around the inner contour of the sun. Through a succession of exposures, McCaw's print is scorched by the visual orientation of the sun in space as the Earth orbits on an angled axis. The works are visual representations of natural phenomena oscillating between scientific documentation and artistic expression. Both works proffer a greater understanding of the world around us through modeling.

"The generative power of models lies in the degree to which they afford opportunities to be equivocal about questions of identity, to elide or blur the extent to which you are positing an underlying continuity of force or matter (a homology of substrate), and the extent to which you are reasoning analogically. And every time you permit a trepidation between those very different fundamental claims ("as" and "is"), every time you allow for an oscillation between referents, important thinking happens—That's how ideas change" (Burnett and Solomon 49).

In science, astronomical photography does not work as a totalizing representation. Newcomb's plate and McCaw's print do not explain the solar parallax. However, they posit a visual model for scientists to "think with" in their understanding of the earth's relationship to the sun.

The muddying of boundaries evidenced in Newcomb's photographic plate and McCaw's gelatin print demonstrates the inseparable nature of Art and Science. The 19th century marked a significant shift in scientific methodology and observation. The emergence of photography in scientific documentation of natural phenomena catalyzed an era of scientific advancement, discovery, and aesthetics. Photography allowed scientists to document the unseen, cosmic events invisible to the naked eye. In addition, the medium provided precision and consistency, an element crucial to scientific research and measurement. An interdisciplinary approach to astronomy across physics, photography, cinematography, pedagogy, and mimetic experimentation produced alternative instruments that advanced fundamental constants of the universe. "By the end of the nineteenth century, there was not a single branch of astronomy in which photography had not proven itself to be far superior to visual observations [...] The great new science of astrophysics unqualifiedly owes its development, it not also its origin to photography" (Norman 590). Through the application of photography, Newcomb fulfilled Halley's 1716 prediction and produced the first astronomical unit. But, could the advancements of 19th-century astronomy have happened without the aid of Photography?

McCaw's gelatin silver print and Newcomb's photographic plate functions as scientific realism. The photographs demonstrate a shift from doctrine and scientific theory towards a new materialism of knowledge formations. Astronomical photography posits a new way "to think about the content of natural science" (Hacking 26). Traditional tools of visualization encumbered 18th-century observations on the Solar Parallax. The creative integration of Photography into research allowed scientists to define celestial bodies beyond the human scope of vision. Like all vehicles of visual communication, Photography is restricted to the plastic laws of organization in visual language. Hence, there is a great deal in common between the Newcombs photographic plate documenting the transit of Venus and McCaw's gelatine silver print documenting the Winter Solstice. Both images can be perceived as poignant works of art. Embedded within the framed image are the values of aesthetic and praxes of plasticity. Although much of science concerns itself with precision, measurement, and empirical data, it is the intervention of art (photography) in science that proffered the continuity of knowledge.

Notes:

Using previous research and new adjustments, German Astronomer, William Harkness produced the first astronomical unit of the Solar Parallax in 1894. However, it was Newcomb’s system of astronomical units that was “adopted internationally at a Paris Conference in 1896.” See Steven J. Dick, “The American Transit of Venus Expedition of 1874 and 1882″ in Transits of Venus: New Views of The Solar System and Galaxy, No. 196, 2004. International Astronomical Union.

The Moon Sits for it’s portrait. The New York Times. Vicki Goldberg. July 3, 2019.

Full title is Plate 7 from 'The collection of the most notable things seen by John Wilkins, erudite English bishop, on his famous trip from the Earth to the Moon... (Raccolta delle cose più notabili Vedute da Giovanni Wilkins erudito Vescove Inglese nel suo famoso viaggio dalla Terra alla Luna...): 'Pumpkins used as dwellings to secure against wild beasts' (Zucche che servono d'abitazioni per garantirsi dalle fiere), after 1783. Filipp Morghen (Italian, Florence 1730–after 1807 Naples). Etching and aquatint. Plate: 10 13/16 × 15 3/16 in. The MET.

“Cigoli’s work blends the study of nature with the work of the High Renaissance artists,” The Adoration of the Shepherds with Saint Catherine of Alexandria, 1599. Cigoli (Ludovico Cardi). Oil painting on canvas. 121 3/8 x 76 1/4 in. The MET.

“There is certainly no mention of the phenomenon, much less of its origin, in his earliest astronomical writing, the somewhat lackluster Tratto della sfera of 1586-1587, though this treatise does not involve an extended discussion of the appearance of the crescent moon when that light was most readily visible.” (Reeves, Painting the Heavens, pg 24).

Bibliography:

D. Graham Burnett and Jonathan D. Solomon, “Masters of the Universe” in Models, ed. by Emily Abruzzo, Eric Ellingsen, and Jonathan D. Solomon (New York: 306090 Books, 2007).

Canales, Jimena. “Photogenic Venus: The ‘Cinematographic Turn’ and Its Alternatives in Nineteenth‐Century France.” Isis, vol. 93, no. 4, [The University of Chicago Press, The History of Science Society], 2002, pp. 585–613, https://doi.org/10.1086/375953.

Carter, William E., Carter, Merri S.. "Simon Newcomb:America’s First Great Astronomer." Physics Today, Vol 62, Issue #2, 2009, 46-51. American Institute of Physics, doi: 10.1063/1.3086102

Cigoli, Ludovico. “The Adoration of the Shepherds with Saint Catherine of Alexandria,” 1599. Collections, MET Museum. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435900. 2021

Dick, S. J. “The American transit of Venus expeditions of 1874 and 1882.” Transits of Venus: New Views of the Solar System and Galaxy, Proceedings of IAU Colloquium #196, held 7-11 June, 2004 in Preston, U.K.. Edited by D.W. Kurtz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p.100-110.

Donald A. “Transits of Venus and the Astronomical Unit.” Mathematics Magazine, vol. 76, no. 5, Mathematical Association of America, 2003, pp. 335–48.

Galileo Galilei, “Two Views of the Moon, in Siderius Nuncius (The Starry Messenger)”, 1619. Collections, MET Museum. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/778099. 2021

Goldberg, Vicki. “The Moon Sits for Its Portrait:A trailblazing exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum explores our fascination with the moon, from the first time Galileo trained his telescope on it to the present." New York Time, July 3 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/03/arts/design/apollos-muse-moon-metropolitan-museum-review.html. 2021

Gyorgy Kepes. Language of Vision, with introductory essays by S. Giedion and S. I. Hayakawa (Chicago: P. Theobald, 1944): 6–14, 44–51, 218–228.

Fineman, Mia and High, Rachel. "Only a Paper Moon? Curator Mia Fineman on Fact, Fantasy, and Photography in Apollo’s Muse,” blog, MET Museum, https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2019/apollos-muse-interview-with-curator-mia-fineman. 2021

Fridlund, Mats, et al., editors. “The Many Ways to Talk about the Transits of Venus: Astronomical Discourses in Philosophical Transactions, 1753–1777.” Digital Histories: Emergent Approaches within the New Digital History, Helsinki University Press, 2020, pp. 237–58, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1c9hpt8.19.

Ian Hacking, Representing and Intervening (Cambridge University Press, 1983), read Ch. 1, “What is Scientific Realism?,” 21–31.

Johnson-Groh, Mara. “The Surprising Ways Art Has Advanced Astronomy.” TIME Magazine, June 04, 2019. Online Article

K. Dea. "Chris McCaw." Widewalls, April 2015, https://www.widewalls.ch/artists/chris-mccaw 2021

Lankford, John. “Photography and the 19th-Century Transits of Venus.” Technology and Culture, vol. 28, no. 3, [The Johns Hopkins University Press, Society for the History of Technology], 1987, pp. 648–57, https://doi.org/10.2307/3104996.

McCaw, Chris. "Sunburned, GSP #166, Mohave/Winter Solstice, 2007,” Collections, MET Museum, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/289113. 2021

Morghen, Filippo. "Plate 7 from 'The collection of the most notable things seen by John Wilkins, erudite English bishop, on his famous trip from the Earth to the Moon... (Raccolta delle cose più notabili Vedute da Giovanni Wilkins erudito Vescove Inglese nel suo famoso viaggio dalla Terra alla Luna...): 'Pumpkins used as dwellings to secure against wild beasts' (Zucche che servono d'abitazioni per garantirsi dalle fiere),” after 1783. Collections, MET Museum, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/811200. 2021

Norman, Daniel. “The Development of Astronomical Photography.” Osiris, vol. 5, [Saint Catherines Press, The University of Chicago Press, The History of Science Society], 1938, pp. 560–94, http://www.jstor.org/stable/301575.Peterson, Ivars. “The Art of Scientific Photography.” Science News, vol. 152, no. 25/26, [Society for Science & the Public, Wiley], 1997, pp. 394–96, https://doi.org/10.2307/3980916.

Peterson, Ivars. “The Art of Scientific Photography.” Science News, vol. 152, no. 25/26, [Society for Science & the Public, Wiley], 1997, pp. 394–96, https://doi.org/10.2307/3980916.

Reeves, Eileen. Painting the Heavens: Art and Science in the Age of Galileo (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).

Winthrop, John. “Observation of the Transit of Venus, June 6, 1761, at St. John’s, Newfound-Land: By John Winthrop, Professor of Mathematicks and Philosophy at Cambridge, New England.” Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775), vol. 54, The Royal Society, 1764, pp. 279–83, http://www.jstor.org/stable/105563.

Woolf, Harry. “British Preparations for Observing the Transit of Venus of 1761.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 13, no. 4, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1956, pp. 499–518, https://doi.org/10.2307/1917021.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

'Hand Of Isis' by John Jude Palencar.

Cover art for the paperback edition of the novel, book 2 in the 'Numinous World' series written by Jo Graham, published in 2010.

#Art Of The Day#Art#AOTD#John Jude Palencar#Hand Of Isis#Jo Graham#Female#Feminine#Goddess#Priestess#Mythology#Egyptian#Egyptian Mythology#Books#Book Cover#Book Cover Art#Cover Art#Fantastical Art#Imaginative Realism

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Choosing Kindness Book Recs

I’m been thinking about stories and the types of things I like to read. I usually think in terms of genre, I love fantasy and space opera and very specific types of romance to name a few. But one type of story I really gravitate to isn’t tied to genre at all (though most of my examples are fantasy). I love stories about genuinly good people doing their best to make the world a better place. Now that doesn’t mean I don’t enjoy stories about anti-heroes, rogues or very flawed characters, I do. But there is a very unique flavor to these stories despite wildly different settings so thought I’d make a list of these types of stories. Characters who, when given a choice, choose kindness. I’ll add more as I think of them but please feel free to add on to this list with your own recs.

The Young Wizards series by Diane Duane Book 1: So You Want to Be A Wizard

All the Heralds of Valdemar books by Mercedes Lackey Book 1: Arrows of the Queen

The Order of the Air by Melissa Scott and Jo Graham Book 1: Lost Things

Stealing Fire by Jo Graham (I don’t know if this trait carries over to the rest of the Numinous World books, I only just started reading the series, but Lydias is such a great character. There are so many moments were he could be selfish or cruel and the world he lives in would excuse or even encourage it but he chooses kindness instead.)

#mercedes lackey#Diane Duane#melissa scott#jo graham#Young Wizards#heralds of valdemar#the order of the air#numinous world#stealing fire#lost things#arrows of the queen#so you want to be a wizard

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

i meant to sent this earlier but i want to hear more abt your space opera wip (if you’re comfortable sharing ofc)!! i see you tag posts w/ it sometimes n the aesthetics seem really fun plus the fact that it’s in space (i assume shdjfjsjs) ????? i’m intrigued

HI BESTIE U JUST MADE MY BRAIN GO "!!!!"

anyway space opera is just a general tag for a wip that has already absorbed another wip and will simply become a series of wips inevitably (also spellcheck has a vendetta against the word wip)

it's set in a futuristic world where there's More Planets That People Live On. also aliens. and they use the Cyrillic alphabet (or perhaps a futuristic adaptation) because Worldbuilding and I Say So

the main one right now is gonna follow Cordelia Sebastian Beatrice, Crown Princess of the country of Numin on the planet uhhh name pending but potentially Portani??

and I have VERY little notion about the plot but at one point an annoying prince shows up for Diplomacy and he's the fourth son of like six kids so he just does whatever and annoys her to death bc she is Responsible. All Business. BUT she loves her family!! and loosens up around them!! she's got a younger brother and an even younger sister, and then her parents. and she's got a few friends too, like a cousin and older lady in the court (every girl needs an older bestie it's Contractual)

and then?? I think there will be Threats so she has to leave and she goes to the research center at Portani's North Pole that monitors air quality and there she meets her three roommates and she's got herself a whole room full of besties. but she also finds her BEST bestie who is a lovely lovely lady named Jane Prescott but who goes by Prescott (friends call her Scott) (best friends–and Cordelia–call her Scottie). editing to add that this base was inspired/based off of one of the maps in Among Us, just looked it up it was the Polus map. I'm gonna definitely work on it so I'm not plagiarizing (one of my biggest fears tbh 😭) but yea I love that map sooo much it gave me Much To Think About

some other ideas were like?? the idea of the people voting on their next monarch?? that's a potential and there could be Drama there

the general overarching space opera has already absorbed a sci-fi wip called Runners. that one follows a ship full of teenagers led by a single tired early-ish adult (autocorrect hates me and my fun and sexy way of speaking) and they're tracking down the Devourer (which they mockingly call the Waddler) which is. a mouth with eyes and legs. that goes around space eating stuff. this sounds weirder when I type it but it was a fun sorta collab with some friends when we were bored in school so I'm keeping it for now

and then later wips will expand to other planets and other Shenanigans and I'm very much looking forward to it

this is sorta my pet wip bc I can go Ham with everything (there's already an amicably arranged marriage story brewing where they're friends and slowly fall in love and make each other laugh at parties) (and then enemies to lovers bc it's my wip and I can do what I want)

also there's three moons on Portani because I say so

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Taxonomy of Magic

This is a purely and relentlessly thematic/Doylist set of categories.

The question is: What is the magic for, in this universe that was created to have magic?

Or, even better: What is nature of the fantasy that’s on display here?

Because it is, literally, fantasy. It’s pretty much always someone’s secret desire.

(NOTE: “Magic” here is being used to mean “usually actual magic that is coded as such, but also, like, psionics and superhero powers and other kinds of Weird Unnatural Stuff that has been embedded in a fictional world.”)

(NOTE: These categories often commingle and intersect. I am definitely not claiming that the boundaries between them are rigid.)

I. Magic as The Gun That Can Be Wielded Only By Nerds

Notable example: Dungeons & Dragons

Of all the magic-fantasies on offer, I think of this one as being the clearest and most distinctive. It’s a power fantasy, in a very direct sense. Specifically, it’s the fantasy that certain mental abilities or personality traits -- especially “raw intelligence” -- can translate directly into concrete power. Being magical gives you the wherewithal to hold your own in base-level interpersonal dominance struggles.

(D&D wizardry is “as a science nerd, I can use my brainpower to blast you in the face with lightning.” Similarly, sorcery is “as a colorful weirdo, I can use my force of personality to blast you in the face with lightning,” and warlockry is “as a goth/emo kid, I can use my raw power of alienation to blast you in the face with lightning.”)

You see this a lot in media centered on fighting, unsurprisingly, and it tends to focus on the combative applications and the pure destructive/coercive force of magic (even if magic is notionally capable of doing lots of different things). It often presents magic specifically as a parallel alternative to brawn-based fighting power. There’s often an unconscious/reflexive trope that the heights of magic look like “blowing things up real good” / “wizarding war.”

II. Magic as The Numinous Hidden Glory of the World

Notable examples: Harry Potter, The Chronicles of Narnia, H.P. Lovecraft’s Dream Cycle

The point of magic, in this formulation, is that it is special. It is intrinsically wondrous and marvelous. Interacting with it puts you in a heightened-state-of-existence. It is -- ultimately -- a metaphor for The Secret Unnameable Yearnings of Your Soul, the glorious jouissance that always seems just out of reach.

It doesn’t so much matter how the magic actually functions, or even what outcomes it produces. The important thing is what magic is, which is...magical.

This is how you get works that are all about magic but seem entirely disinterested in questions like “what can you achieve with magic?,” “how does the presence of magic change the world?,” etc. One of the major ways, anyway.