#not danmei btw but still fandom so

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This isn’t danmei related but it still baffles me how angry people were at the ending of A Plague Tale: Requiem, calling the game pointless because so many people died for Hugo and I’m like???? Y’all do realize Requiem wasn’t about Hugo, right? It gives you the illusion that it is but it’s clearly about Amicia, her inner turmoil and the horrific trauma she’s been through all while trying to save her baby brother while she’s still a baby herself. It’s about her self-destructive spiral of desperation and the consequences her obsession with saving her brother has on the rest of the world. That was the point. That was the lesson. It was intentional.

Also why are y’all expecting a 16-year-old girl who basically thinks she has nothing to live for aside of her brother to think about saving the same people who are actively trying to terrorize and kill them both and prioritize these people over saving her brother lmfaooo pls be fr

#i have way more articulate thoughts on this im just lazy rn#but APT is one of my fave franchises#and I’ve spoken with the devs and writers one on one about their vision for the game#i just don’t understand how it flew over people’s heads when it was so clearly expressed#like sorry i may not have siblings#but if i was a 16 yr old girl with a baby brother everyone wanted to treat like a lab rat#and steal from me so they can use him for their own selfish power trips#i wouldn’t give a fuck about saving them either lmaooo#she’s not a leader or a politician or a goddamn freedom fighter#she’s a teenage girl with a sling and only 1 person left in her life who hasn’t been slaughtered brutally in front of her#ajdhajhdAJDHAJD#anyway sorry been watching some playthroughs on yt and made myself mad ahahaHAHAHA#apple babble 🍎#not danmei btw but still fandom so

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

You know since I see this constantly brought up when anyone talks about Chinese novels, especially danmei and the tropes used, and one of the asks brought this back to the forefront again.

It's great that some of you have read MXTX's works, but you do realize that you're allowed to read danmei novels from other Chinese authors. And you're also allowed to talk about them. Just because MXTX's novels have the biggest fandoms out there in the West, doesn't mean that literally every vague mention of Chinese tropes or any mention of danmei is by default and exclusively about MXTX.

I love MXTX's novels as well, I enjoy rereading them, but I've also read and am reading novels from other Chinese danmei authors. Recently I'm reading the official Priest and Meatbun translations, and it's getting ridiculous with how many people take any vague mention of a danmei novel, or even just a mention of Chinese novels and common tropes in general and with full conviction claim it must be about MXTX instead of some of the hundreds of fan translated danmei or some of the tens of officially translated novels you can find. Especially when trying to avoid spoilers by being a bit vague.

There are actually small fandoms for these other novels as well, yeah maybe there are only a few hundred or thousand fics for them instead of like 100k+ combined, but that doesn't mean they don't exist.

I completely get that if you mention something that also happened in MXTX's work that most people will probably immediately point towards her works. But that doesn't mean that her works are 100% the answer just because in the West she has the biggest following. MXTX's works also have several common tropes that you can find in the works of other authors, that doesn't mean every time one of those tropes is mentioned it's about her works, or at least not JUST about her works. I think the main reason this irks me so much is because people start building a huge strawman because they've convinced themselves that it must be MXTX no matter what you say and there's just no way that it could be anything but MXTX, because they just don't read anything else. Don't get me started on show-series only people, they often don't even seem to realize that other Chinese danmei authors and stories exist period.

Spoilers used as an example: If I say "Shizun fucker pining after his dead Shizun." Of course people are gonna point at SVSSS first because it's a bigger fandom. Well but maybe this was about Mo Ran and Chu Wanning from Husky and his white cat Shizun instead, a smaller but still comparatively big fandom. But you have even smaller fandoms around novels with that premise. You'd actually be surprised about how many Shizun fuckers pining for their dead Shizun novels there are out there tbh. You can do the exact same thing for transmigration btw.

--

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

here to save your life.

Mo Dao Zu Shi (alternate names: Founder of diabolism, Grandmaster of demonic cultivation or mdzs for short) is an danmei novel written by Mo Xiang Tong Xu also known as mxtx in the fandom (we love you our god) which was originally published in 2016. Till now it has had multiple adaptations including an donghua, manhua, live action as well as a chibi version and an audio drama.

I highly suggest to send your support for the novel through official sites but since a lot of people can't afford to buy the books or watch and listen to the adaptations because of different issues of their own, I will be linking the places where these are available for free so that no one has to go through much trouble finding them.

Just a reminder that some of these are not official sites where the adaptations were aired which technically makes them (slightly) illegal but that's too common in the fandom so if you're new no you're not going to jail. The websites are safe and I will give specifications to avoid ads just in case.

𝗡𝗼𝘃𝗲𝗹

The novel has a total of 126 chapters. The main story consists of 113 chapters and the other 13 are extras. Reading the novel was my best decision ever and I can bet my life that you won't be disappointed with it. The characters, the storyline, the freaking lines. Everything is perfect from the top and to the bottom. It has been rated mature as it includes explicit content and slight non-con?? It wasn't really non-con but then also maybe it was. It's debatable really trust me on this. You can read it here. Happy reading!!!

𝗗𝗼𝗻𝗴𝗵𝘂𝗮+𝗖𝗵𝗶𝗯𝗶 𝗩𝗲𝗿𝘀𝗶𝗼𝗻

To put it simply donghua is Chinese animation. Most people say that it's just anime but Chinese. But from experience I can say that don't say it out loud cause it makes some people really angry. The mdzs donghua has 3 seasons having 15, 8 and 12 episodes respectively. The chibi version is called Mo Dao Zu Shi Q and has 30 episodes consisting of 5-6 mins each.

Season 1 can be watched here.

Season 2 can be watched here.

Season 3 can be watched here.

Chibi version can be watched here.

(Tip: Download the brave browser from playstore before clicking the links as it blocks the ads completely so you can watch in peace. It is safe.)

𝗠𝗮𝗻𝗵𝘂𝗮

Manhua refers to a Chinese comic. The mdzs manhua has a total of 259 chapters. But due to our luck they have been censored which have left a few people banging their head on the wall (including me). But do not worry cause those chapters can be found on twitter. But really tho how hard is it to uncensore a kiss?? Nvm moving on from my despair you can read the manhua here.

And if you have the unquenchable thirst to read the uncensored scenes then you can find them by just searching on Google tho it has been said that the manhua publishing company will publish them soon enough.

Edit: THANK YOU TO THAT ONE ANGEL ON INSTA i got to know about the website which has been posting about the uncensored scenes here.

𝗟𝗶𝘃𝗲-𝗮𝗰𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻

This part is my fav I swear. The live-action is called The Untamed and has a total of 50 episodes consisting of 43-45 mins each. They are all available on youtube for free!! I will still link them all here. They are absolutely breathtaking. Due to the Chinese censorship the plot has been altered but there's not much of a difference according to me. I do think that the romance is a bit subtle but it's there. You can feel it through the screen and it makes you swoon so bad. I'm completely in love with the drama. It's so beautifully done.

There is also a special edition of the drama with the same name which consists of 20 episodes with the duration time of almost an hour on each episode. It was made for international fans with a different ending and focuses more on the relationship btw our male leads instead of the plot. Some scenes have been cut and some have been added. It's just as amazing. It's available here. The first 3 episodes are also available on youtube.

(Again don't forget to use the brave browser to remove ads)

𝗔𝘂𝗱𝗶𝗼 𝗗𝗿𝗮𝗺𝗮

Man the audio drama is just....perfect. There is not a single thing I can complain about. The emotions are perfectly conveyed. The audio effects of fighting or the sound of their breathing, even the slightest sounds have been added so make it as real as possible and it certainly does it's job. Earlier the audio drama was fully available on YouTube but unfortunately it has now been deleted. You can access it by joining the discord server of Treasure Chest Subs. Here is the link along with the steps on how to join on their website.

𝘐 𝘳𝘦𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘦𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘵𝘰 𝘶𝘴𝘦 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘯 𝘢𝘴 𝘪𝘵'𝘴 𝘦𝘢𝘴𝘪𝘦𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘸𝘢𝘺 :

Novel

Manhua

Audio Drama

Donghua+Chibi version

Live Action+Special Edition

The rest is up to you of course!!! Hope you have fun with MDZS. I love it so much and I hope you will too now. This is my top danmei and there definitely is a reason for that. Happy journey to MDZS hell ;) P.S. If the links do not work or if you're having any problems with it please let me know. I will keep on updating the links if they are changed by any chance so it won't be much of a hassle.

-with love, rose

#mo dao zu shi#wei wuxian#the untamed#mdzs#mxtx#lan wangji#lan zhan#grandmaster of demonic cultivation#wei ying#danmei#lan sizhui#lan xichen#lan sect#nie huaisang#founder of diabolism#audio drama#donghua#mo xiang tong xiu#manhua#hanguang jun#yiling patriarch#yiling laozu#yiling burial mounds#gusu lan#cloud recesses

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

tldr: censorship fucking sucks and word of honor and xena are mlm/wlw solidarity

okay this was a random thought that came to me during a combo of rewatching of Word of Honor and reading a post that declared Word of Honor “didn’t count” on their BL list of whatever the fuck and here’s the thought, here’s the vibe, Word Of Honor has a lot in common with Xena: Warrior Princess

Hear me out

Everyone kinda knows that Xena - and by extension Lucy Lawless - as a bisexual/queer woman icon, and that Xena/Gabrielle is probably still one of the most prominent wlw ships in western canon. That’s a huge part of the shows iconography in pop culture. But like, if you rewatch the show, things between Xena and Gabrielle are kept pretty ambiguous but in that ambiguously totally gay way (like WenZhou!).

The network was actively against Xena and Gabrielle being more than, what fans would probably call nowadays, bait. An executive told producer Rob Tapert that by making Xena and Gabrielle explicit there would be a surge of interested followed by a sharp decline.

It should be noted that Xena was already a controversial show for it’s era - not just for the gay subtext but under fire from religious groups, anti-feminist groups, and others.

The showrunners and producers also didn’t intend for Xena and Gabrielle’s relationship to, eh, blossom the way it did. Fans ran with it. Ironically, the intention of the show was to push Xena’s men of color love interests which also made the network gun shy (remember folks racism exists alongside homophobia!).

Xena and Gabrielle operated in a highly censored space (that still exists in American media btw!! Take it from someone who knows first hand) that was beholden to network hand-wringing, capitalism, and societal homophobia at large. So their relationship could only live within an ambiguous space. Ironically enough, just like WenZhou, Xena and Gabrielle are also referred to as “soulmates” in the text of the show. But ya know, sometimes soulmates are platonic, sometimes romantic. Which are WenZhou and Xena/Gabrielle? Well that’s up for the viewer to decide b/c the production teams hands are tied.

Even so, even with the censorship, we all still view Xena as legitimate queer representation within the pop culture space. Why? Why Xena and not Word of Honor?

For me, they both count, especially WoH because it’s source material IS queer. But the filter of censorship snipped and cut the text away so everything would be forced to live within that ambiguous “up to the audience aka gotta make the advertisers comfortable” space.

I don’t think it’s fair to throw WoH out because the production couldn’t, like they were not allowed, to showcase text on screen. Similar to Xena queer fans knew that her and Gabrielle were in love, soulmates (romantic) by the end (where Xena dies, like literal for reals death she’s ashes carried on by Gabby at the end btw spoiler alert for a 20 year old show at least WK got silver hair and immortality out of his death experience).

Queer fans appreciated and cultivated what Xena gave us because, no offense but what the fuck else was there? Not a lot, and even less in the fantasy space. Hell, there’s still not a lot of queer representation in the fantasy space we’re only just now going “hey maybe Tolkien’s ultra white British view of things is not the only way to do things?" And now House of Dragon has Black actors in terrible wigs (they’re so fucking bad rip) in 2022. Woooo~ most queer chars in western fantasy media are mainly found in kids cartoons - which, fucking aces there but also - probably why there’s so many adults in those spaces in fandom (not my bag personally) and why I think the popularity of danmei, c-dramas, and k-dramas is on the rise. People are hungry for epic fantasy content, epic romance content, and queer content.

but like, I think about queer folks who live in China, who watched WoH (ya know, the intended audience, not Americans) who are probably feeling the same thing people felt when they watched Xena. Yeah, Mr. Advertiser Xena and Gabrielle are soulmates (platonic) wink wink, Yeah Mr. Network ZZS and WKX are soulmates (platonic) wink wink

and I think that’s still valuable. idk I just don’t think it’s right for foreigners to be like “no you’re queer media doesn’t count actually because I deem it so” when the reason for the relationship being subtextual is literal censorship. And yet the text is hella gay anyway!! like at the end of the day we’re all battling the crushing weight of homophobia but not everyone’s fight is exactly the same especially country-to-country and I think that should still be respected. given how damn gay WoH is anyway I imagine the producers fought really fucking hard to give audiences what they did. Just like the producers of Xena fought against the network to do what they could.

anyway, thoughts and shit

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you!

I think it is partly, but I have thoughts to add? because I love shonen The comparison to shonen is interesting because yes there are people who dismiss all anime as sexist because they watched dragonball or whatever (I love dragonball btw. childhood nostalgia), but there's also plenty of debate within the shonen community about it's representation of women... and things are changing! There are more female mangakas writing shonen, shonen mangakas are more aware of feminist issues, and I think magazines like Shonen Jump do appreciate that women make up a good chunk of its readership, despite still primarily aiming its work at young boys. There's still a long long way to go, but compared to shonen (or even Shonen Jump in particular) 30 or 50 years ago, you see a shift. Within shonen, there are better and worse examples for this. I think HxH does it's female characters pretty well, despite being a story primarily about male characters. Yu Yu Hakusho (same author, written earlier) does it less well.

BL is changing too! I'm less familiar with how danmei has shifted over time because most my knowledge of BL history is based on a great talk I went to about Japanese BL/yaoi history, but anyway, BL mangakas have been aware of lots of issues from very early on. BL has expanded massively, both in the sheer volume of content produced and in the kind of stories that are portrayed. Subversions of tropes are common. Subversions of tropes are now becoming tropes.

Women in BL is interesting, because unlike women in shonen, women have always been at the heart of BL. Even stories that don't have female characters can very much be about women (this generates all kinds of other discussion). But you're right - BL focuses on male characters and their relationships. So when we discuss female characters, we're discussing side characters, and comparing side characters to protagonists is unfair. Then again, side characters are things we have discussed before, even in the west - the whole 'not like other girls' and the 'mean girl' thing in YA for example.

I don't know where I'm going with this in tbh but I guess the point is that raising the issue of female representation in BL is (I think) completely valid. Ofc there are stupid ways to go about this. To add to your point, at least in the western fandom, I think maybe the problem is that gay stuff is put under the umbrella of 'progressive' and is thus held to higher expectations. Or maybe it's part of a larger trend to complain about everything in everything (not that this is inherently bad but I feel like people forget the discussions are different in different places and holding everything to the same standard is unhelpful). And maybe (as with sexism in anime) there's an element of screaming into the void here because most the people who write this stuff just don't interact with the English speaking fandom. But I think having a healthy amount of discussion within a fandom is important (not least because it gives you a full set of counterarguments when people disagree with your interests lol)

Sorry about the length of this. And if you noticed, the spelling mistakes upstairs😛

MXTX's women

Let's do ✨discourse™✨

Addendum: I checked out twitter (x now?) for the first time in ages and... um... maybe this isn't a good time for discourse. But hey, I love mxtx so I'm just going to do a Shen Yuan and pretend absolutely everything is fine.

I feel like a lot of the discourse around MXTX and sexism don't hit the mark? Things like 'there are few female characters', 'the female characters die', 'the female characters don't hold positions of power' are not indications as to whether a piece of work standing on its own is sexist. For example, you could write an entire novel about a sexless robot (which miserably fails the Bechdel test because there is only one character) and that says nothing about whether the work itself is sexist. This is an caricature of an example and of course, overall trends give a very different picture to individual works, so its not to take such works off the hook either. Similarly, including sexist troupes isn't inherently sexist, but equally arguing something is a 'critique' isn't a shield against criticism. Critique can be done badly, critique can become outdated, critique itself can be critiqued.

But equally the counterargument to this can't entirely be 'but look at x, y, and z - aren't they great female characters?'. Look, I love mxtx's women. I can write essays (plural) about mxtx's women. Many people already have. Then again, Eowyn from lotr is arguably a pretty deep character, but I would have problems if lotr was the best example of female representation we could come up with. The point being, the existence (or lack thereof) of strong female characters isn't (entirely) the point, even though it's often made out to be. Don't get me wrong, good female representation without strong female characters is... erm... hard. But if it was the crux of the argument, the discourse could be killed in three tumblr posts.

The bigger question(s) (possibly) is: What is its intent? How is that intent received?

SVSSS, MDZS, and TGCF are all extremely different pieces of work. SVSSS in particular stands out, because at its heart, it is satire. While debates around what kind of comedy is and isn't good exist independently of SVSSS, needless to say, judging satire in the same way you would say a murder mystery or a romantic fantasy is not advisable. Sha Hualing is a sexy demon lady whose clothes rip off in the middle of a battle. Why? Because that's saying something about a particular troupe of a particular genre.

(Side note: I have opinions on how we shove different BLs together when they really shouldn't be under the same umbrella and how this muddies the discourse unnecessarily. I'm talking about Killing Stalking btw)

For SVSSS, if you get it, you get it (it's impossible to read without understanding this). While some loose threads exist about how female characters could have been more developed... man, do you know how much development my boy Mu Qingfang got? You're not sexist if you punch everyone (only half ironic here). (In terms of character development I also think this might be a fandom thing as well as a SVSSS thing.) But I think more relevantly, SVSSS tells you something about the way MXTX writes critique.

If you didn't notice, SVSSS is critique on two levels. First is the blatant critique of the harem genre, and the second is more subtle critique on BL, on fandoms, on webnovels, on literature. But while we get Shen Qingqiu's commentary guiding us through the first bit, this drops during the second bit. It takes Shen Qingqiu so long to realise that what he's living through is a crazy mishmash of BL troupes that the only narration you get on this is Pure Confusion. To realise Luo Binghe and Shen Qingqiu's early interactions is commentary on the 'dark and obsessive love' troupe, you need to immediately realise that Shen Qingqiu telling you Luo Binghe is trying to kill him is just... Wrong. So (possibly, ofc I've no idea what's going on in the author's head) the intent is critique. But intent is meaningless without it being conveyed to the reader. So how are we meant to 'realise' what is going on?

Firstly, MXTX tells you. Shen Qingqiu goes: 'damn Luo Binghe isn't acting like in those weird danmei novels' and you're meant to go 'oh weird danmei novels I know about those'. Second is her very obvious use of troupes (even flagged!). 'Clothes rip/disappear in the middle of a serious situation, isn't this weird? Where have we seen that before?'. And thirdly, by introducing a sense of absurdity. Luo Binghe and Shen Qingqiu's relationship is presented in such an unconventional way (the master-disciple pair which generated a famous porno!) that it forces you to engage with it critically.

Okay, so what does that have to do with sexism? Take MDZS. We have a set of very troupy characters - 'the older sister', 'the scary mother', 'the strong independent woman', 'the damsel in distress'. We have explorations and subversions that go beyond troupes: Jiang Yanli's character shaped by her experiences in an abuse household, Yu Ziyuan's pride and loyalty, Wen Qing's well... everything, and Mianmian needs no explanation. We have flags to tell us we are meant to care about these issues: most obviously Mianmian experiencing gendered harassment for speaking up. All the women die! Yeah, isn't that a problem. Because it's the women sacrificing themselves, women silently taking on burdens, women chained by the circumstances of the world around them and still making choices about what is important to them (and it's often not themselves). The women aren't in positions of power/aren't shown to be as competent as the men! They're literally put down when they speak up, and don't the wives have a great time with their husbands. MDZS is critique of society. MDZS's women too are a critique of the society they (we) live in.

But not all critique is good critique! The first way that critique can fail is if it just isn't registered as critique by the reader. And this isn't always on the reader. If the author isn't clear enough on this, then they have failed to execute the intent of their work. And to this extent, I've heard enough people say that MDZS is maybe sexist as a first reaction (myself included) to think that yeah, maybe this wasn't well done. The flags are scarce. The subversions of troupes are subtle enough to be missed in it's entirety. Then again, MDZS often ends up as people's gateway piece into danmei, when it is probably better understood with more context - for me, coming back to MDZS after a big BL reading spree was exceptionally enlightening. As to whether it could have been better done in the bounds of the genre, without detracting from the banging story it was... I honestly don't know.

One way to go about it is, well... TGCF. Here everything is laid out to you to an almost bizarre degree. 'Look, isn't this a Hard Question' the narrative stops to tell you at multiple points, from Bai Wuxiang and Xie Lian's back and forths, to 'I don't know if what I did was right' speeches on a regular basis (maybe not regular but it was enough to notice). The troupes are still there but their twists are far more obvious. Xuan Ji is the 'deranged woman' who is (we are told multiple times) surprisingly normal and competent when she isn't around Pei Ming. Yushi Huang and Banyue are just obviously strong, competent, and in positions of power. Shi Qingxuan shines in all of her wonder, kindness, and unfortune. The flags are more glaring as well: Just Pei Ming's Existence, Ling Wen's whole backstory, Jian Lan's tragedy... And it probably worked? Since people seem to complain significantly less about any supposed sexism of TGCF.

Do I like it? I like elements of it. Ling Wen is honestly great.

But I love the subtlety with which MDZS weaves its themes and tbh I think some of the magic was lost there. (I love TGCF to bits for different reasons but yeah)

Does MXTX's writing of women merit discussion? Of course, everything merits discussion. Particularly MXTX's works which rely so heavily on genre troupes to craft themes. Is MXTX's work sexist? Idk, I would say no, but these things are Hard Questions.

But my feeling? My true feeling? At the very least, it is So. Much. Better. than a huge amount of work that tries to be feminist and pitifully fails.

My current pet peeve is the 'strong independent woman'. Depicting a sexist society then including a 'strong independent women' with no true appreciation of the realistic struggles she would face, as if the only barriers that we face within these societies is to stop being a loser... is worse in my books than not including any women at all. Or 'strong independent women' who turn out to be utterly pathetic and in constant need of saving. Or 'strong independent women' who have no other personality than being the 'strong independent woman'. The intent here is to come across as feminist and progressive without critically engaging in anything. It's paper thin.

Ultimately, the core theme of MDZS and TGCF isn't about women's experiences (whereas SVSSS is, I would argue, right into the nooks and crannies). Do these works explore such themes to the extent it explore privilege, conflict, and oppression? Not really. But you can't do everything - the role of an author is inherently about choosing what to prioritise. And given what it does do, I think it does some pretty neat things.

85 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you talk more about the usage of the word "wife" to talk about men in the BL context? I've noticed it in BJYX (particularly with GG), in the (English translations) of MDZS, and then it came up in your recent posts about Danmei-101 (which were super helpful btw) with articles connecting the "little fresh meat" type to fans calling an actor "wife." My initial reaction as a westerner is like "this is very problematic," but I think I'm missing a lot of language/cultural context. Any thoughts?

Hello! First of all, for those who’re interested, here’s a link to the referred posts. Under the cut is arguably the 4th post of the series. As usual, I apologise for the length!

(Topics: seme and uke; more about “leftover women”; roster of feminisation terms; Daji, Bao Si & the origin of BJYX; roster of beautiful, ancient Chinese men; Chairman Mao (not part of the roster) ...)

[TW: feminisation of men]

In the traditional BL characterisation, the M/M (double male) lead pairing is essentially a cis-het relationship in disguise, in which one of the M leads is viewed as the “wife” by the creator and audience. This lead often possesses some of the features of the traditional, stereotypical female, but retaining his male appearance.

In BL terms, the “wife” is the “uke”. “Seme” and “uke” are the respective roles taken by the two male leads, and designated by the creator of the material. Literally, “seme” (攻め) means the dominant, the attacking / aggressive partner in the relationship and “uke” (受け), the passive / recipient (of actions) partner who tends to follow the seme’s lead. The terms themselves do not have any sexual / gender context. However, as male and female are viewed as aggressive and passive by their traditional social roles, and the attacker and recipient by their traditional sexual roles respectively, BL fandoms have long assigned uke, the passive, sexual “bottom”, as the “woman”, the “wife”.

Danmei has kept this “semi” and uke” tradition from BL, taking the kanji of the Japanese terms for designation ~ 攻 (”attack” is therefore the “husband”, and 受 (”receive”), the “wife”. The designations are often specified in the introduction / summary of Danmei works as warning / enticement. For MDZS, for example, MXTX wrote:

高貴冷豔悶騷 攻 × 邪魅狂狷風騷 受

高貴冷豔悶騷 攻 = noble, coolly beautiful and boring seme (referring to LWJ) 邪魅狂狷風騷 受 = devilishly charming, wild, and flirty uke (referring to WWX)

The traditional, stereotypical female traits given to the “uke”, the “wife” in Danmei and their associated fanworks range from their personality to behaviour to even biological functions. Those who have read the sex scenes in MDZS may be aware of their lack of mention of lube, while WWX was written as getting (very) wet from fluids from his colon (腸道) ~ implying that his colon, much like a vagina, was supplying the necessarily lubrication for sex. This is obviously biologically inaccurate; however, Danmei is exempt from having to be realistic by its original Tanbi definition. The genre’s primary audience is cishet females, and sex scenes such as this one aren’t aiming for realism. Rather, the primary goal of these sex scenes is to generate fantasy, and the purpose of the biologically female functions in one of the leads (WWX) is to ease the readers into imagining themselves as the one engaging in the sex.

Indeed, these practices of assigning as males and female the M/M sexual top and bottom, of emphasising of who is the top and who is the bottom, have been falling out of favour in Western slash fandoms ~ I joined fandom about 15 years ago, and top and bottom designations in slash pairings (and fights about them) were much more common than it is now. The generally more open, more progressive environments in which Western fandomers are immersed in probably have something to do with it: they transfer their RL knowledge, their views on biology, on different social into their fandom works and discourses.

I’d venture to say this: in the English-speaking fandoms, fandom values and mainstream values are converging. “Cancel culture” reflects an attempt to enforce RL values in the fictional worlds in fandom. Fandom culture is slowly, but surely, leaving its subculture status and becoming part of mainstream culture.

I’d hesitate to call c-Danmei fandoms backward compared to Western slash for this reason. There’s little hope for Danmei to converge with China’s mainstream culture in the short term ~ the necessity of replacing Danmei with Dangai in visual media already reflects that. Danmei is and will likely remain subculture in the foreseeable future, and subcultures, at heart, are protests against the mainstream. Unless China and the West define “mainstream” very similarly (and they don’t), it is difficult to compare the “progressiveness”—and its dark side, the “problematic-ness”—of the protests, which are shaped by what they’re protesting against. The “shaper” in this scenario, the mainstream values and culture, are also far more forceful under China’s authoritarian government than they are in the free(-er) world.

Danmei, therefore, necessarily takes on a different form in China than BL or slash outside China. As a creative pursuit, it serves to fulfil psychological needs that are reflective of its surrounding culture and sociopolitical environment. The genre’s “problematic” / out of place aspects in the eyes of Western fandoms are therefore, like all other aspects of the genre, tailor-made by its millions of fans to be comforting / cathartic for the unique culture and sociopolitical background it and they find themselves in.

I briefly detoured to talk about the Chinese government’s campaign to pressure young, educated Chinese women into matrimony and motherhood in the post for this reason, as it is an example of how, despite Western fandoms’ progressiveness, they may be inadequate, distant for c-Danmei fans. Again, this article is a short and a ... morbidly-entertaining read on what has been said about China’s “leftover women” (剩女) — women who are unmarried and over 27-years-old). I talked about it, because “Women should enter marriage and parenthood in their late 20s” may no longer a mainstream value in many Western societies, but where it still is, it exerts a strong influence on how women view romance, and by extension, how they interact with romantic fiction, including Danmei.

In China, this influence is made even stronger by the fact that Chinese tradition places a strong emphasis on education and holds a conservative attitude towards romance and sex. Dating while studying therefore remains discouraged in many Chinese families. University-educated Chinese women therefore have an extremely short time frame — between graduation (~23 years old) and their 27th birthday — to find “the right one” and get married, before they are labelled as “leftovers” and deemed undesirable. (Saving) face being an important aspect in Chinese culture introduces yet another layer of pressure: traditionally, women who don’t get married by the age agreed by social norms have been viewed as failures of upbringing, in that the unmarried women’s parents not having taught/trained their daughters well. Filial, unmarried women therefore try to get married “on time” just to avoid bringing shame to their family.

The outcome is this: despite the strong women characters we may see in Chinese visual media, many young Chinese women nowadays do not expect themselves to be able to marry for love. Below, I offer a “book jacket summary” of a popular internet novel in China, which shows how the associated despair also affects cis-het fictional romance. Book reviews praise this novel for being “boring”: the man and woman leads are both common working class people, the “you-and-I”’s; the mundaneness of them trying build their careers and their love life is lit by one shining light: he loves her and she loves him.

Written in her POV, this summary reflects, perhaps, the disquiet felt by many contemporary Chinese women university graduates:

曾經以為,自己這輩子都等不到了—— 世界這麼大,我又走得這麼慢,要是遇不到良人要怎麼辦?早過了「全球三十幾億男人,中國七億男人,天涯何處無芳草」的猖狂歲月,越來越清楚,循規蹈矩的生活中,我們能熟悉進而深交的異性實在太有限了,有限到我都做好了「接受他人的牽線,找個適合的男人慢慢煨熟��再平淡無奇地進入婚姻」的準備,卻在生命意外的拐彎處迎來自己的另一半。

I once thought, my wait will never come to fruition for the rest of my life — the world is so big, I’m so slow in treading it, what if I’ll never meet the one? I’ve long passed the wild days of thinking “3 billion men exist on Earth, 0.7 of which are Chinese. There is plenty more fish in the sea.” I’m seeing, with increasing clarity, that in our disciplined lives, the number of opposite-sex we can get to know, and get to know well, is so limited. It’s so limited that I’m prepared to accept someone’s matchmaking, find a suitable man and slowly, slowly, warm up to him, and then, to enter marriage with without excitement, without wonder. But then, an accidental turn in my life welcomes in my other half.

— Oath of Love (餘生,請多指教) (Yes, this is the novel Gg’d upcoming drama is based on.)

Heteronormativity is, of course, very real in China. However, that hasn’t exempted Chinese women, even its large cis-het population, from having their freedom to pursue their true love taken away from them. Even for cis-het relationships, being able to marry for love has become a fantasy —a fantasy scorned by the state. Remember this quote from Article O3 in the original post?

耽改故事大多远离现实,有些年轻受众却将其与生活混为一谈,产生不以结婚和繁衍为目的才是真爱之类的偏颇认知。

Most Dangai stories are far removed from reality; some young audience nonetheless mix them up with real life, develop biased understanding such as “only love that doesn’t treat matrimony and reproduction as destinations is true love”.

I didn’t focus on it in the previous posts, in an effort to keep the discussion on topic. But why did the op-ed piece pick this as an example of fantasy-that-shouldn’t-be-mixed-up-with-real-life, in the middle of a discussion about perceived femininity of men that actually has little to do with matrimony and reproduction?

Because the whole point behind the state’s “leftover women” campaign is precisely to get women to treat matrimony and reproduction as destinations, not beautiful sceneries that happen along the way. And they’re the state’s destination as more children = higher birth rate that leads to higher future productivity. The article is therefore calling out Danmei for challenging this “mainstream value”.

Therefore, while the statement True love doesn’t treat matrimony and reproduction as destinations may be trite for many of us while it may be a point few, if any, English-speaking fandoms may pay attention to, to the mainstream culture Danmei lives in, to the mainstream values dictated by the state, it is borderline subversive.

As much as Danmei may appear “tame” for its emphasis on beauty and romance, for it to have stood for so long, so firmly against China’s (very) forceful mainstream culture, the genre is also fundamentally rebellious. Remember: Danmei has little hope of converging with China’s mainstream unless it “sells its soul” and removes its homoerotic elements.

With rebelliousness, too, comes a bit of tongue-in-cheek.

And so, when c-Danmei fans, most of whom being cishet women who interact with the genre by its traditional BL definition, call one of the leads 老婆 (wife), it can and often take on a different flavour. As said before, it can be less about feminizing the lead than about identifying with the lead. The nickname 老婆 (wife) can be less about being disrespectful and more about humorously expressing an aspiration—the aspiration to have a husband who truly loves them, who they do want to get married and have babies with but out of freedom and not obligation.

Admittedly, I had been confused, and bothered by these “can-be”s myself. Just because there are alternate reasons for the feminisation to happen doesn’t mean the feminisation itself is excusable. But why the feminisation of M/M leads doesn’t sound as awful to me in Chinese as in English? How can calling a self-identified man 老婆 (wife) get away with not sounding being predominantly disrespectful to my ears, when I would’ve frowned at the same thing said in my vicinity in English?

I had an old hypothesis: when I was little, it was common to hear people calling acquaintances in Chinese by their unflattering traits: “Deaf-Eared Chan” (Mr Chan, who’s deaf), “Fat Old Woman Lan” (Ah-Lan, who’s an overweight woman) etc—and the acquaintances were perfectly at ease with such identifications, even introducing themselves to strangers that way. Comparatively speaking then, 老婆 (wife) is harmless, even endearing.

老婆, which literally means “old old-lady” (implying wife = the woman one gets old with), first became popularised as a colloquial, casual way of calling “wife” in Hong Kong and its Cantonese dialect, despite the term itself being about 1,500 years old. As older generations of Chinese were usually very shy about talking about their love lives, those who couldn’t help themselves and regularly spoke of their 老婆 tended to be those who loved their wives in my memory. 老婆, as a term, probably became endearing to me that way.

Maybe this is why the feminisation of M/M leads didn’t sound so bad to me?

This hypothesis was inadequate, however. This custom of identifying people by their (unflattering) traits has been diminishing in Hong Kong and China, for similar reasons it has been considered inappropriate in the West.

Also, 老婆 (wife) is not the only term used for / associated with feminisation. I’ve tried to limit the discussion to Danmei, the fictional genre; now, I’ll jump to its associated RPS genre, and specifically, the YiZhan fandoms. The purpose of this jump: with real people involved, feminisation’s effect is potentially more harmful, more acute. Easier to feel.

YiZhan fans predominantly entered the fandoms through The Untamed, and they’ve also transferred Danmei’s “seme”/“uke” customs into YiZhan. There are, therefore, three c-YiZhan fandoms:

博君一肖 (BJYX): seme Dd, uke Gg 戰山為王 (ZSWW): seme Gg, uke Dd 連瑣反應 (LSFY): riba Gg and Dd. Riba = “reversible”, and unlike “seme” and “uke”, is a frequently-used term in the Japanese gay community.

BJYX is by far the largest of the three, likely due to Gg having played WWX, the “uke” in MDZS / TU. I’ll therefore focus on this fandom, ie. Gg is the “uke”, the “wife”.

For Gg alone, I’ve seen him being also referred to by YiZhan fans as (and this is far from a complete list):

* 姐姐 (sister) * 嫂子 (wife of elder brother; Dd being the elder brother implied) * 妃妃 (based on the very first YiZhan CP name, 太妃糖 Toffee Candy, a portmanteau of sorts from Dd being the 太子 “prince” of his management company and Gg being the prince’s wife, 太子妃. 糖 = “candy”. 太妃 sounds like toffee in English and has been used as the latter’s Chinese translation.) * 美人 (beauty, as in 肖美人 “Beauty Xiao”) * Daji 妲己 (as in 肖妲己, “Daji Xiao”).

The last one needs historical context, which will also become important for explaining the new hypothesis I have.

Daji was a consort who lived three thousand years ago, whose beauty was blamed for the fall of the Shang dynasty. Gg (and men sharing similar traits, who are exceptionally rare) has been compared to Daji 妲己 for his alternatively innocent, alternatively seductive beauty ~ the kind of beauty that, in Chinese historical texts and folk lores, lead to the fall of kingdoms when possessed by the king’s beloved woman. This kind of “I-get-to-ruin-her-virginity”, “she’s a slut in MY bedroom” beauty is, of course, a stereotypical fantasy for many (cis-het) men, which included the authors of these historical texts and folklores. However, it also contained some truth: the purity / innocence, the image of a virgin, was required for an ancient woman to be chosen as a consort; the seduction, meanwhile, helped her to become the top consort, and monopolise the attention of kings and emperors who often had hundreds of wives ~ wives who often put each other in danger to eliminate competition.

Nowadays, women of tremendous beauty are still referred to by the Chinese idiom 傾國傾城, literally, ”falling countries, falling cities”. The beauty is also implied to be natural, expressed in a can’t-help-itself way, perhaps reflecting the fact that the ancient beauties on which this idiom has been used couldn’t possibly have plastic surgeries, and most of them didn’t meet a good end ~ that they had to pay a price for their beauty, and often, with their lowly status as women, as consorts, they didn’t get to choose whether they wanted to pay this price or not. This adjective is considered to be very flattering. Gg’s famous smile from the Thailand Fanmeet has been described, praised as 傾城一笑: “a smile that topples a city”.

I’m explaining Daji and 傾國傾城 because the Chinese idiom 博君一笑 “doing anything to get a smile from you”, from which the ship’s name BJYX 博君一肖 was derived (笑 and 肖 are both pronounced “xiao”), is connected to yet another of such dynasty-falling beauty, Bao Si 褒姒. Like Daji before her, Bao Si was blamed for the end of the Zhou Dynasty in 771 BC.

The legend went like this: Bao Si was melancholic, and to get her to smile, her king lit warning beacons and got his nobles to rush in from the nearby vassal states with their armies to come and rescue him, despite not being in actual danger. The nobles, in their haste, looked so frantic and dishevelled that Bao Si found it funny and smiled. Longing to see more of the smile of his favourite woman, the king would fool his nobles again and again, until his nobles no longer heeded the warning beacons when an actual rebellion came.

What the king did has been described as 博紅顏一笑, with 紅顏 (”red/flushed face”) meaning a beautiful woman, referring to Bao Si. Replace 紅顏 with the respectful “you”, 君, we get 博君一笑. If one searches the origin of the phrase 博 [fill_in_the_blank]一笑 online, Bao Si’s story shows up.

The “anything” in ”doing anything to get a smile from you” in 博君一笑, therefore, is not any favour, but something as momentous as giving away one’s own kingdom. c-turtles have remarked, to their amusement and admittedly mine, that “king”, in Chinese, is written as 王, which is Dd’s surname, and very occasionally, they jokingly compare him to the hopeless kings who’d give away everything for their love. Much like 傾國傾城 has become a flattering idiom despite the negative reputations of Daji and Bao Si for their “men-ruining ways”, 博君一笑 has become a flattering phrase, emphasising on the devotion and love rather than the ... stupidity behind the smile-inducing acts.

(Bao Si’s story, BTW, was a lie made up by historians who also lived later but also thousands of years ago, to absolve the uselessness of the king. Warning beacons didn’t exist at her time.)

Gg is arguably feminized even in his CP’s name. Gg’s feminisation is everywhere.

And here comes my confession time ~ I’ve been amused by most of the feminisation terms above. 肖妲己 (”Daji Xiao”) captures my imagination, and I remain quite partial to the CP name BJYX. Somehow, there’s something ... somewhat forgivable when the feminisation is based on Gg’s beauty, especially in the context of the historical Danmei / Dangai setting of MDZS/TU ~ something that, while doesn’t cancel, dampens the “problematic-ness” of the gender mis-identification.

What, exactly, is this something?

Here’s my new hypothesis, and hopefully I’ll manage to explain it well ~

The hypothesis is this: the unisex beauty standard for historical Chinese men and women, which is also breathtakingly similar to the modern beauty standard for Chinese women, makes feminisation in the context of Danmei (especially historical Danmei) flattering, and easier to accept.

What defined beauty in historical Chinese men? If I am to create a classically beautiful Chinese man for my new historical Danmei, how would I describe him based on what I’ve read, my cultural knowledge?

Here’s a list:

* Skin fair and smooth as white jade * Thin, even frail; narrow/slanted shoulders; tall * Dark irises and bright, starry eyes * Not too dense, neat eyebrows that are shaped like swords ~ pointed slightly upwards from the center towards the sides of the face * Depending on the dynasty, nice makeup.

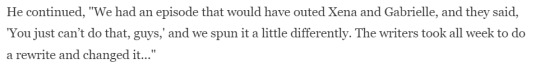

Imagine these traits. How “macho” are they? How much do they fit the ideal Chinese masculine beauty advertised by Chinese government, which looks like below?

Propaganda poster, 1969. The caption says “Defeat Imperialist US! Defeat Social Imperialism!” The book’s name is “Quotations from Mao Zedong”. (Source)

Where did that list of traits I’ve written com from? Fair like jade, frail ... why are they so far from the ... “macho”ness of the men in the poster?

What has Chinese history said about its beautiful men?

Wei Jie (衛玠 286-312 BCE), one of the four most beautiful ancient Chinese men (古代四大美男) recorded in Chinese history famously passed away when fans of his beauty gathered and formed a wall around him, blocking his way. History recorded Wei as being frail with chronic illness, and was only 27 years old when he died. Arguably the first historical account of “crazy fans killing their idol”, this incident left the idiom 看殺衛玠 ~ “Wei Jie being watched to death.” ~ a not very “macho” way to die at all.

潘安 (Pan An; 247-300 BCE), another one of the four most beautiful ancient Chinese men, also had hoards of fangirls, who threw fruits and flowers at him whenever he ventured outside. The Chinese idiom 擲果盈車 “thrown fruit filling a cart” was based on Pan and ... his fandom, and denotes such scenarios of men being so beautiful that women openly displayed their affections for them.

Meanwhile, when Pan went out with his equally beautiful male friend, 夏侯湛 Xiahou Zhan, folks around them called them 連璧 ~ two connected pieces of perfect jade. Chinese Jade is white, smooth, faintly glowing in light, so delicate that it gives the impression of being somewhat transparent.

Aren’t Wei Jie and Pan An reminiscent of modern day Chinese idols, the “effeminate” “Little Fresh Meat”s (小鲜肉) so panned by Article O3? Their stories, BTW, also elucidated the historical reference in LWJ’s description of being jade-like in MDZS, and in WWX and LWJ being thrown pippas along the Gusu river bank.

Danmei, therefore, didn’t create a trend of androgynous beauty in men as much as it has borrowed the ancient, traditional definition of masculine Chinese beauty ~ the beauty that was more feminine than masculine by modern standards.

[Perhaps, CPs should be renamed 連璧 (”two connected pieces of perfect jade”) as a reminder of the aesthetics’ historical roots.]

Someone may exclaim now: But. But!! Yet another one of the four most beautiful ancient Chinese men, 高長恭 (Gao Changgong, 541-573 BCE), far better known by his title, 蘭陵王 (”the Prince of Lanling”), was a famous general. He had to be “macho”, right?

... As it turns out, not at all. Historical texts have described Gao as “貌柔心壮,音容兼美” (”soft in looks and strong at heart, beautiful face and voice”), “白美類婦人” (”fair and beautiful as a woman”), “貌若婦人” (”face like a woman”). Legends have it that The Prince of Lanling’s beauty was so soft, so lacking in authority that he had to wear a savage mask to get his soldiers to listen to his command (and win) on the battlefield (《樂府雜錄》: 以其顏貌無威,每入陣即著面具,後乃百戰百勝).

This should be emphasised: Gao’s explicitly feminine descriptions were recorded in historical texts as arguments *for* his beauty. Authors of these texts, therefore, didn’t view the feminisation as insult. In fact, they used the feminisation to drive the point home, to convince their readers that men like the Prince of Lanling were truly, absolutely good looking.

Being beautiful like a women was therefore high praise for men in, at least, significant periods in Chinese history ~ periods long and important enough for these records to survive until today. Beauty, and so it goes, had once been largely free of distinctions between the masculine and feminine.

One more example of an image of an ancient Chinese male beauty being similar to its female counterpart, because the history nerd in me finds this fun.

何晏 (He Yan, ?-249 BCE) lived in the Wei Jin era (between 2nd to 4th century), during which makeup was really en vogue. Known for his beauty, he was also famous for his love of grooming himself. The emperor, convinced that He Yan’s very fair skin was from the powder he was wearing, gave He Yan some very hot foods to eat in the middle of the summer. He Yan began to sweat, had to wipe himself with his sleeves and in the process, revealed to the emperor that his fair beauty was 100% natural ~ his skin glowed even more with the cosmetics removed (《世說新語·容止第十四》: 何平叔美姿儀,面至白。魏明帝疑其傅粉,正夏月,與熱湯餅。既啖,大汗出,以朱衣自拭,色轉皎然). His kick-cosmetics’-ass fairness won him the nickname 傅粉何郎 (”powder-wearing Mr He”).

Not only would He Yan very likely be mistaken as a woman if this scene is transferred to a modern setting, but this scene can very well fit inside a Danmei story of the 21st century and is very, very likely to get axed by the Chinese censorship board for its visualisation.

[Important observation from this anecdote: the emperor was totally into this trend too.]

The adjectives and phrases used above to describe these beautiful ancient Chinese men ~ 貌柔, 音容兼美, 白美, 美姿儀, 皎然 ~ have all become pretty much reserved for describing beauty in women nowadays. Beauty standards in ancient China were, as mentioned before, had gone through significantly long periods in which they were largely genderless. The character for beauty 美 (also in Danmei, 耽美) used to have little to no gender association. Free of gender associations as well were the names of many flowers. The characters for orchid (蘭) and lotus (蓮), for example, were commonly found in men’s names as late as the Republican era (early 20th century), but are now almost exclusively found in women’s names. Both orchid and lotus have historically been used to indicate 君子 (junzi, roughly, “gentlemen”), which have always been men. MDZS also has an example of a man named after a flower: Jin Ling’s courtesy name, given to him by WWX, was 如蘭 (”like an orchid”).

A related question may be this: why does ancient China associate beauty with fairness, with softness, with frailty? Likely, because Confucianist philosophy and customs put a heavy emphasis on scholarship ~ and scholars have mostly consisted of soft-spoken, not muscular, not working-under-the-sun type of men. More importantly, Confucianist scholars also occupied powerful government positions. Being, and looking like a Confucianist scholar was therefore associated with status. Indeed, it’s very difficult to look like jade when one was a farmer or a soldier, for example, who constantly had to toil under the sun, whose skin was constantly being dried and roughened by the elements. Having what are viewed as “macho” beauty traits as in the poster above ~ tanned skin, bulging muscles, bony structures (which also take away the jade’s smoothness) ~ were associated with hard labour, poverty and famine.

Along that line, 手無縛雞之力 (“hands without the strength to restrain a chicken”) has long been a phrase used to describe ancient scholars and students, and without scorn or derision. Love stories of old, which often centred around scholars were, accordingly, largely devoid of the plot lines of husbands physically protecting the wives, performing the equivalent of climbing up castle walls and fighting dragons etc. Instead, the faithful husbands wrote poems, combed their wife’s hair, traced their wife’s eyebrows with cosmetics (畫眉)...all activities that didn’t require much physical strength, and many of which are considered “feminine” nowadays.

Were there periods in Chinese history in which more ... sporty men and women were appreciated? Yes. the Tang dynasty, for example, and the Yuan and Qing dynasties. The Tang dynasty, as a very powerful, very open era in Chinese history, was known for its relations to the West (via the Silk Road). The Yuan and Qing dynasties, meanwhile, were established by Mongolians and Manchus respectively, who, as non-Han people, had not been under the influence of Confucian culture and grew up on horsebacks, rather than in schools.

The idea that beautiful Chinese men should have “macho” attributes was, therefore, largely a consequence of non-Han-Chinese influence, especially after early 20th century. That was when the characters for beauty (美), orchid (蘭), lotus (蓮) etc began their ... feminisation. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which started its reign of the country starting 1949, also has foreign roots, being a derivative of the Soviets, and its portrayal of ideal men has been based on the party’s ideology, painting them as members of the People’s Liberation Army (Chinese army) and its two major proletariat classes, farmers and industrial workers ~ all occupations that are “macho” in their aesthetics, but held at very poor esteem in ancient Chinese societies. All occupations that, to this day, may be hailed as noble by Chinese women, but not really deemed attractive by them.

Beauty, being an instinct, is perhaps much more resistant to propaganda.

If anything, the three terms Article O3 used to describe “effeminate” men ~ 奶油小生 “cream young men” (popularised in 1980s) , 花美男 “flowery beautiful men” (early 2000s), 小鲜肉 “little fresh meat” (coined in 2014 and still popular now) ~ only informs me how incredibly consistent the modern Chinese women’s view of ideal male beauty has been. It’s the same beauty the Chinese Communist Party has called feminine. It’s the same beauty found in Danmei. It’s the same beauty that, when witnessed in men in ancient China, was so revered that historians recorded it for their descendants to remember. It doesn’t mean there aren’t any women who appreciate the "macho” type ~ it’s just that, the appreciation for the non-macho type has never really gone out of fashion, never really changed. The only thing that is really changing is the name of the type, the name’s positive or negative connotations.

(Personally, I’m far more uncomfortable with the name “Little fresh meat” (小鲜肉) than 老婆 (wife). I find it much more insulting.)

Anyway, what I’d like to say is this: feminisation in Danmei ~ a genre that, by definition, is hyper-focused on aesthetics ~ may not be as "problematic” in Chinese as it is in English, because the Chinese tradition didn’t make that much of a differentiation between masculine and feminine beauty. Once again, this isn’t to say such mis-gendering isn’t disrespectful; it’s just that, perhaps, it is less disrespectful because Chinese still retains a cultural memory in which equating a beautiful man to a beautiful woman was the utmost flattery.

I must put a disclaimer here: I cannot vouch for this being true for the general Chinese population. This is something that is buried deep enough inside me that it took a lot of thought for me to tease out, to articulate. More importantly, while I grow up in a Chinese-speaking environment, I’ve never lived inside China. My history knowledge, while isn’t shabby, hasn’t been filtered through the state education system.

I’d also like to point out as well, along this line of thought, that in *certain* (definitely not all) aspects, Chinese society isn’t as sexist as the West. While historically, China has periods of extreme sexism against women, with the final dynasties of Ming and Qing being examples, I must (reluctantly) acknowledge Chairman Mao for significantly lifting the status of women during his rule. Here’s a famous quote of his from 1955:

婦女能頂半邊天 Women can lift half the skies

The first marriage code, passed in 1950, outlawed forced marriages, polygamy, and ensured equal rights between husband and wife. For the first time in centuries, women were encouraged to go outside of their homes and work. Men resisted at first, wanting to keep their wives at home; women who did work were judged poorly for their performance and given less than 50% of men’s wage, which further fuelled the men’s resistance. Mao said the above quote after a commune in Guizhou introduced the “same-work-same-wage” system to increase its productivity, and he asked for the same system to to be replicated across the country. (Source)

When Chairman Mao wanted something, it happened. Today, Chinese women’s contribution to the country’s GDP remains among the highest in the world. They make up more than half of the country’s top-scoring students. They’re the dominant gender in universities, in the ranks of local employees of international corporations in the Shanghai and Beijing central business districts—among the most sought after jobs in the country. While the inequality between men and women in the workplace is no where near wiped out — stories about women having to sleep with higher-ups to climb the career ladder, or even get their PhDs are not unheard of, and the central rulership of the Chinese Communist Party has been famously short of women — the leap in women’s rights has been significant over the past century, perhaps because of how little rights there had been before ~ at the start of the 20th century, most Chinese women from relatively well-to-do families still practised foot-binding, in which their feet were literally crushed during childhood in the name of beauty, of status symbol. They couldn’t even walk properly.

Perhaps, the contemporary Chinese women’s economic contribution makes the sexism they encounter in their lives, from the lack of reproductive rights to the “leftover women” label, even harder to swallow. It makes their fantasies fly to even higher, more defiant heights. The popularity of Dangai right now is pretty much driven by women, as acknowledged by Article O3. Young women, especially, female fans who people have dismissed as “immature”, “crazy”, are responsible for the threat the Chinese government is feeling now by the genre.

This is no small feat. While the Chinese government complains about the “effeminate” men from Danmei / Dangai, its propaganda has been heavily reliant on stars who have risen to popularity to these genres. The film Dd is currently shooting, Chinese Peacekeeping Force (維和部隊), also stars Huang Jingyu (黄景瑜), and Zhang Zhehan (張哲瀚) ~ the three actors having shot to fame from The Untamed (Dangai), Addicted (Danmei), and Word of Honour (Dangai) respectively. Zhang, in particular, played the “uke” role in Word of Honour and has also been called 老婆 (wife) by his fans. The quote in Article O3, “Ten years as a tough man known by none; one day as a beauty known by all” was also implicitly referring to him.

Perhaps, the government will eventually realise that millennia-old standards of beauty are difficult to bend, and by extension, what is considered appropriate gender expression of Chinese men and women.

In the metas I’ve posted, therefore, I’ve hesitated in using terms such as homophobia, sexism, and ageism etc, opting instead to make long-winded explanations that essentially amount to these terms (thank you everyone who’s reading for your patience!). Because while the consequence is similar—certain fraction of the populations are subjected to systemic discrimination, abuse, given less rights, treated as inferior etc—these words, in English, also come with their own context, their own assumptions that may not apply to the situation. It reminds me of what Leo Tolstoy wrote in Anna Karenina,

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Discrimination in each country, each culture is humiliating, unhappy in its own way. Both sexism and homophobia are rampant in China, but as their roots are different from those of the West, the ways they manifest are different, and so must the paths to their dissolution. I’ve also hesitated on calling out individual behaviours or confronting individuals for this reason. i-Danmei fandoms are where i-fans and c-fans meet, where English-speaking doesn’t guarantee a non-Chinese sociopolitical background (there may be students from China, for example; I’m also ... not entirely Western), and I find it difficult to articulate appropriate, convincing arguments without knowing individual backgrounds.

Frankly, I’m not sure if I’ve done the right thing. Because I do hope feminisation will soon fade into extinction, especially in i-Danmei fandoms that, if they continue to prosper on international platforms, may eventually split from c-Danmei fandoms along the cultural (not language) line due to the vast differences in environmental constraints. My hope is especially true when real people are involved, and c-fandoms, I’d like to note, are not unaware of the issues surrounding feminisation ~ it has already been explicitly forbidden in BJYX’s supertopic on Weibo.

At the same time, I’ve spent so many words above to try to explain why beauty can *sometimes* lurk behind such feminisations. Please allow me to end this post with one example of feminisation that I deeply dislike—and I’ve seen it used by fans on Gg as well—is 綠茶 (”green tea”), from 綠茶婊 (”green tea whore”) that means women who look pure / innocent but are, deep down, promiscuous / lustful. In some ways, its meaning isn’t so different from Daji 妲己, the consort blamed for the fall of the Shang dynasty. However, to me at least, the flattery in the feminisation is gone, perhaps because of the character “whore” (婊), because the term originated in 2013 from a notorious sex party rather than from a legendary beauty so maligned that The Investiture of the Gods (封神演義), the seminal Chinese fiction written ~2,600 years after Daji’s death, re-imagined her as a malevolent fox spirit (狐狸精) that many still remembers her as today.

Ah, to be caught between two cultures. :)

229 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I... I don’t often call out anyone specifically using social media before, but... I saw this among the reblogs in my first post about MXTX novels English release announcement and I feel that this is just too much...

I’m not going to tag this with the fandom tags because this is literally just my personal rant, and I don’t want unpleasant things to appear when people are happily browsing the tags.

I also censored the person’s blog name. It’s not like I want people to mass attack them.

But I do have some things I want to say about this kind of mindset.

And this is gonna be a long post, so I’ll cut it with "Read More” later below as not to disturb anyone’s browsing experience.

Why do they have to split the books into multiple volumes?

First, you do realize that the original Chinese version and other languages versions are also in multiple volumes that don’t always be published on the same date, right?

SVSSS has 3 volumes, MDZS has 4 volumes, TGCF has 5 volumes.

With the English release, both SVSSS and MDZS get +1 volume while TGCF gets +3 volumes.

Why you ask?

Have you ever considered how long a single Chinese word would be if written in alphabets?

The word “人” in Chinese only needs 1 (one) character, while in English it would translate to “P E O P L E” = 5 (five) characters.

The word “知己” in Chinese only needs 2 (two) characters, while in English it would translate to “C O N F I D A N T E” = 10 characters, or “S O U L M A T E” = 8 characters.

Now apply this to an entire novel. FYI, TGCF has more than 1 million word count in Chinese, so you can do the math by yourself.

I mean, just go watch the donghua or live action in YouTube. One single sentence in the Chinese sub is often translated to two or more lines in the English subtitle.

And have I mentioned that the English release will have:

Glossary

Footnotes

Character Guides

And I’m going to repeat this once again: In China and other countries that already get their official releases, it is also NOT always all released on the same date as a single set/box.

So yes, (not) surprise! For the Chinese release and official releases in other countries, you also often need to purchase multiple times, pay shipping fee multiple times, and wait for certain period of times until all volumes are released.

It doesn’t only happen to MXTX novels, it happens to almost all novels, be it danmei or not.

Why don’t they just wait for translations to finish and release it all at the same time/as a box set? Why the span of two years?

On my part, I already say above that in China and other countries that already get their official release, it’s also not always published all on the same date.

Other than that, I’m not an expert at book publishing, much less when the publisher is not from my own country. But maybe consider the following:

They’re releasing 3 (three) hugely popular IPs all at the same time. Maybe the preparations take more time and effort to ensure everything is flawless?

Since it is very rare (or maybe never, cmiiw) for danmei novels to be published in English, maybe the publisher is testing the market first? Because if they already release them as a huge bundle from the start and it somehow flops, the loss would be very big. If it works well, then good! Maybe for future danmei release, they will consider making a box set or releasing them within shorter timeframe.

In terms of marketing, if they wait another 2 years to release it all at once, will the momentum still be there? You can say “so in the end it’s all about money”, but if not sales number and money, what else should the publisher expect to receive for their work? They’re already putting a lot of effort buying all three IPs from the Chinese publishers, proofread or even translate some from scratch, pay translators, editors, illustrators, printing companies, etc. If it’s not selling well simply because they release it at the wrong time, aren’t all these efforts going to be wasted? And you can bet there will be no more danmei published in English if their first try already flops merely because of losing the momentum.

Are there any other rules or regulations they need to comply that prevents them from releasing everything in one go? But once again, even in China and other countries, it is also not always all released in one go, so this argument is already invalid from the start.

But they make it so expensive like this!

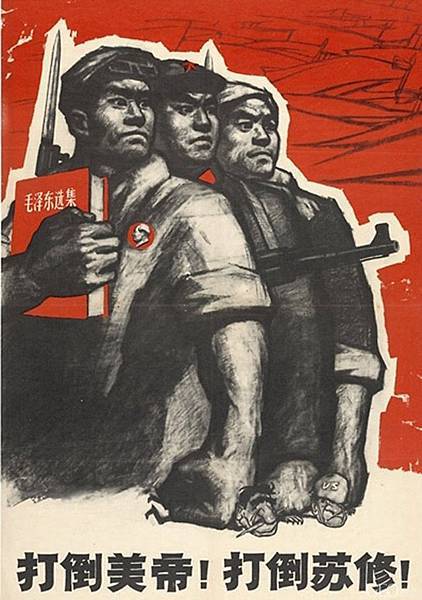

I’m sorry to break it to you, but I’ve compared the prices to MDZS Japanese release + TGCF Thai release and... The price isn’t really that much different.

Btw, I’m using Google’s currency converter, in case anyone wants to know where does my calculation comes from.

Okay, so here’s MDZS Japanese version from CD Japan:

One volume of MDZS Regular ver. cost 1760 yen. This is 15,96 USD before shipping. There’s only like $4 difference.

There’s also the Exclusive ver. that cost 3660 yen (32,92 USD) but we’re not gonna talk about that because they’re basically making you pay for the bonus, which is some acrylic panels and illustration cards.

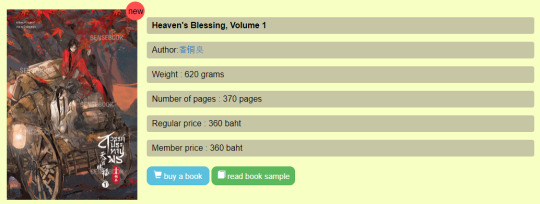

Now here’s TGCF Thai version from Sense Book:

Translation using Google Chrome page translate:

One volume of TGCF costs 360 baht. This is 10.77 USD before shipping. So there’s about $9.22 difference.

Again, notice the difference of word/sentence length in the Thai words and English alphabet.

"But there’s still difference in price and other releases usually gets merchandise!” - Correct me if I’m wrong, but the US is probably one of the most expensive countries in the world. Do you think the materials, printings, and manpower cost is the same with other countries? Especially compared to one in Southeast Asia.

“But it’s xxxx times more expensive than the original Chinese version!” - Excuse me, the original Chinese version doesn’t need to pay for translators, proofreaders and editors with multilingual skills, and purchase the IPs? If you think it’s more worth buying the Chinese version, then by all means go ahead.

------------

Some last words...

I’m not looking down on those in difficult financial situation, but hey, I’m not filthy rich either? I come from a third world country and even if I’m a working adult, I’m still in working middle class + I got my parents to take care of. My country’s currency is literally just a tiny 0.000069 USD per 1 Indonesian Rupiah.

Every single fandom merchandise that you see me bought, either I’ve saved up for that or I sacrificed other things to buy that. I just don’t show the struggle to you guys because why should I? I’m just here to have fun about the fandom I love, not to flex my struggling financial condition.

These official English release of MXTX novels? All 17 books are going to cost me almost HALF of my monthly salary. But hey, I think it’s a good thing that they didn’t release it all at once, so that I can save up between months to purchase them all and plan my spending better.

If you feel the price is expensive, especially if you have to ship from outside North America, consider the following:

Book Depository provide free worldwide shipping

The books’ ISBN numbers are all available in the publisher’s website, just show it to you local bookstore and ask if they can order it for you

Plus, there are already hundreds of generous fans doing free giveaways in Twitter, even the publishers are helping to signal boost this. You can go and try your luck if you’re really desperate.

Lastly, I know how much love we all have for our favorite fandoms, but remember that fandom merchandise is NOT your primary needs.

You are NOT obliged to purchase any fandom merchandise if you can’t afford it and you should ALWAYS prioritize your primary needs.

Also, if you still want to read the fan-translations that are still available, alright go ahead. But remember that the translators themselves already said fan translations in English are now illegal. You can read it. We all consume pirated contents at one point. But don’t flex about it and diss the official release just because you can’t afford it.

I don’t know if the person who made that reblog tags are going to come at me or not, but even if they do, I literally don’t care. I’m not gonna waste my time arguing with someone with that kind of mindset and will block them right on the spot.

Also Idgaf if they call me out or talk behind my back, I literally don’t know them, so I don’t care.

End of rant.

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please please do write the post about wwx not being dumb/oblivious. Those posts were just funny at first but somehow it's now become accepted fact. Meanwhile whether cql or mdzs wwx is a very competent, savvy protagonist who's actually pretty observant! It's getting pretty tiring to see him reduced to genki oblivous magical girl (not that I don't like those, it's just wwx is not one).

Hey anon!

I do plan on writing a more elaborate meta post exploring what arguments there are in the novel to support my wwx is not dumb/oblivious agenda.

But for now I just want to address one factor I think plays a big part in shaping the fandom’s perception of wwx as oblivious/dumb, regardless of how wwx was actually written in the novel. That is, the creative liberties taken by (or forced onto) the cql production team, which have had in my opinion two consequences: 1) cql does not manage to establish how quick-witted and savvy wwx is, which is compounded by the fact that it chose to play the troublemaker persona straight 2) the fact that wwx and lwj’s relationship is entirely subtext actually ends up making wwx look oblivious (at least to people applying a queer reading/bl-danmei reading to their interactions--people who are obvious to or choose to ignore the subtext certainly wouldn’t come to the same conclusions).

So, the first issue. In the novel, wwx’s intelligence is more of a focal point in the narrative because it is a crucial part of the dramatic irony/tragedy of his death: as a result it cannot help being more important to the themes of the novel. After all, he is ultimately hunted down because of and killed by his inventions. The man created an entirely new field of cultivation! In cql, this is somewhat lost due to the fact that he does not invent modao nor does he create the yin hufu, and his death is more of a suicide than a sacrifice (i am still not over the fact that he throws the yin hufu at the crowd to let them wage war over it? that’s the complete thematic opposite of his death in the novel...).

The novel, as well, is better at establishing that wwx’s antics are generally not because he’s just being a troublemaker, but that they are a way in which he garners information, gets people to act the way he needs them to or misdirect them. For instance, in cql, when lwj destroys wwx’s (well, nhs’s) spring book in the library, wwx looks genuinely pained and affronted--in the novel, it is clearly shown that, when wwx realized lwj intended to bring the spring book to lqr, he intentionally made him angry so that he would destroy the evidence himself. the point of the prank was also to not only get a reaction out of lwj, but also (reading btw the lines) wwx’s way of trying to leave a lasting impression on lwj now that his punishment was over. Differently put, while wwx can do directionless pranks, more often than not, they have an underlying meaning/goal instead of just being for Attention(TM) in general. In contrast, the web series is full of missed opportunities in terms of characterisation, and is so from the very beginning (I find extremely disappointing how they decided to adapt the mo mansion and dafan mountain arcs because of how important they are to establishing wwx’s character for the readers/viewers. Through these arcs, we get acquainted with the way he thinks and deduces information, and how he uses people’s perceptions of him and others to his advantage. If you can only read English, @pumpkinpaix‘s translation of the first few chapters might help get a better sense of the nuances).

I’m not saying that wwx is portrayed as dumb in cql: but that his characterization is a lot more fuzzy and inconsistent, and that his intelligence is utilized mostly when wwx goes into his detective mode. As a result, I do feel like it undermines how analytical wwx is in all aspects of his life, making it easy to see him as, you know, someone who’s, like, half-smart, half-super-dumb.