#north mississippi all stars

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Pigpen’s Spirit and Songs Fill the Air at Terrapin Clubhouse

Phil Lesh has been thinking lately of Pigpen.

So he invited some Friends - guitarists Luther Dickinson, Stu Allen and Grahame Lesh; drummer Cody Dickinson; keyboardist Holly Bowling; and singer Elliott Peck - to Terrapin Clubhouse to conjure the late Grateful Dead frontman and resident bluesman’s spirit and songs.

The resulting seventh episode of the bassist’s “Clubhouse Sessions” is thus chunky, funky and spirited as rare songs fill the rarified air and Lesh’s young musical pals help the 84-year-old look back to his musical beginnings.

“Operator” kicks things off with Luther Dickinson on the mic and the band cooking up a Dead Mississippi All Stars gumbo of rootsy music both ancient and modern. And while the vocals leave something to be desired, the playing is focused, yet loose; a cover infused with in-the-moment freshness.

Peck steals the show with a staggeringly beautiful interpretation of “The Stranger (Two Souls In Communion).” Packed with emotion and supported by the band, Peck renders the ballad in a new, yet respectful, way and makes the case for adding it to her and/or Midnight North’s repertoire.

Lesh the elder sings “Alligator” and the swampy arrangement suits his baritone quite well. Though no one would ever accuse Lesh of possessing a technically solid singing voice, this showcase is an unexpected treat.

Which leads to “Caution (Do Not Stop on Tracks).” With Luther Dickinson back on the mic and the band both riding and melting down on the titular rails, it’s a fitting cap to a lovely nod to the man born Ron McKernan who “was and is now forever one of the Grateful Dead.”

Read Sound Bites’ previous Clubhouse Sessions coverage here.

8/8/24

#Youtube#phil lesh#phil lesh & friends#grateful dead#pigpen#ron pigpen mckernan#terrapin clubhouse#north mississippi all stars#luther dickinson#cody dickinson#stu allen#grahame lesh#elliott peck#midnight north#holly bowling#operator#the stranger (two souls in communion)#alligator#caution (do not step on tracks)

1 note

·

View note

Text

North Mississippi All Stars Cohoes Music Hall Oct 2023

0 notes

Text

Where Will All The Martyrs Go [Chapter 4: Read Between The Lines]

Series summary: In the midst of the zombie apocalypse, both you and Aemond (and your respective travel companions) find yourselves headed for the West Coast. It’s the 2024 version of the Oregon Trail, but with less dysentery and more undead antagonists. Watch out for snakes! 😉🐍

Series warnings: Language, sexual content (18+ readers only), violence, bodily injury, med school Aemond, character deaths, nature, drinking, smoking, drugs, Adventures With Aegon, pregnancy and childbirth, the U.S. Navy, road trip vibes, Jace is here unfortunately.

Series title is a lyric from: “Letterbomb” by Green Day.

Chapter title is a lyric from: “Boulevard Of Broken Dreams” by Green Day.

Word count: 5.6k

💜 All my writing can be found HERE! 💜

Let me know if you’d like to be added to the taglist 🥰

It is your first week of basic training at Great Lakes on the north side of Chicago, and as you lie in the top bunk of your assigned bed you wonder what the hell you’ve done. You enlisted right out of high school, eighteen, no driver’s license, no work history, never been more than fifty miles outside of Soft Shell, Kentucky. The drill sergeants are always yelling and you’re bad at push-ups; you can’t understand the recruits from big cities like Los Angeles, Miami, Las Vegas, Detroit, Houston, and they don’t seem to get you either, and aren’t interested enough to try. Sometimes you wish you hadn’t signed that five-year contract, but where would you be if you weren’t here? Home is not words but textures, colors, fumes that still burn in your sinuses: cigarette ash on rose pink carpets, red embers glowing in the wood stove, Hamburger Helper and Mountain Dew, coffee creamer in Hungry Jack potatoes, laughter and heavy footsteps and slamming doors, scratch-off games, dogs barking, collecting coins from couch cushions for gas money, scrubbing clothes in the bathtub when the washer quits, Mama taking gulps from her favorite cup—plastic, Virginia Beach, filled with equal parts Hawaiian Punch and vodka—when she thinks no one is looking, blue shows flickering on the television, Family Feud, Maury, Good Morning America, WWE SmackDown. For as long as you can remember you’ve known you couldn’t stay. Now you’re getting out, but nothing in life is free.

You are at Class A Technical School in Gulfport, Mississippi, and even though it’s hotter than some noxious, volcanic hellscape—Mercury, Venus, Io—you are beginning to like it. You taste the salt of sweat when you lick your lips, sugar in the sweet tea they serve in the chow hall. There’s a magic in building something where there was only empty space before, in patching roofs and painting walls. Here being quiet and watchful is exactly what they want from you: head down, hammer striking nails, measurements and angles and long hours under the sun with no complaints. You’re not just running away anymore. You are creating something new.

You are sitting beneath swaying palm trees and a full moon on Diego Garcia, draining cans of Guinness with Rio, and he’s telling you things he shouldn’t, too personal, too honest: Sophie wants to try for a baby next time he’s home on leave, and part of him wants that too but he’s terrified. As thunder rumbles in the distance and raindrops begin to patter on the waves of the Indian Ocean, you tell Rio you think he’d be a good father. He wonders how you figure that, and you say because he’s not like any of the men from home. He gives you one of his crooked smiles—a flash of teeth, knowing dark eyes—and doesn’t ask what you mean.

But of course, when you swim up from the inky currents of sleep you are in none of these places. You are curled up on the floor of a bowling alley in Shenandoah, Ohio, cheap worn black carpet peppered with stars and swirls in neon green, pink, blue. You stretch out with a yawn. Someone has left a Lemon Tea Snapple within reach; you twist it open and guzzle it, hoping to extinguish the pounding in your skull, a rhythmic thudding of warm maroon, half Captain Morgan and half misery. The music isn’t helping. From the green Toshiba CD player, a man is singing in Spanish. Aegon and Rio are sitting at the nearest table and playing Uno.

Aegon says as he ponders his cards: “You know Enrique Iglesias, right Rio?”

“You are so racist.” Rio puts down a wild. “And the new color is red. Racist.”

“So what’s he saying?”

“Aegon, buddy, I told you, I was born here. My grandparents came over in the 60s. I don’t speak Spanish.”

“You can’t understand any of it?” Aegon is skeptical. He plays a skip, a reverse, and a seven. “My dad never taught me a word of Greek but I can recognize plenty of phrases. Vlákas means idiot. Spatáli chórou is a waste of space.”

Rio sighs, relenting. He puts down a two. “The song is called Súbeme La Radio, Turn Up The Radio For Me. Bring me the alcohol that numbs the pain… I don’t care about anything anymore…You’ve left me in the shadows…”

“Damn, now I’m sad. Draw four, bitch.”

“When the night comes and you don’t answer, I swear to you I’ll stay waiting at your door…” Rio studies his cards. “What’s the new color?”

“Green.”

“Yes!” Rio slams down a skip. “Fleeing from the past in every dawn, I can’t find any way to erase our history…”

Everyone else is awake already. As muted late-morning daylight streams in through the small tinted windows, Aemond is weaving between tables, pointedly checking on each person. He glances at you, says nothing, turns around and walks the other way.

“That’s tough,” Rio says sympathetically, popping open the tab on a can of Chef Boyardee and shoveling ravioli into his mouth with a plastic fork.

Aegon gives you a smirk. “You want to fake date now?”

“I’ll think about it.” No you won’t.

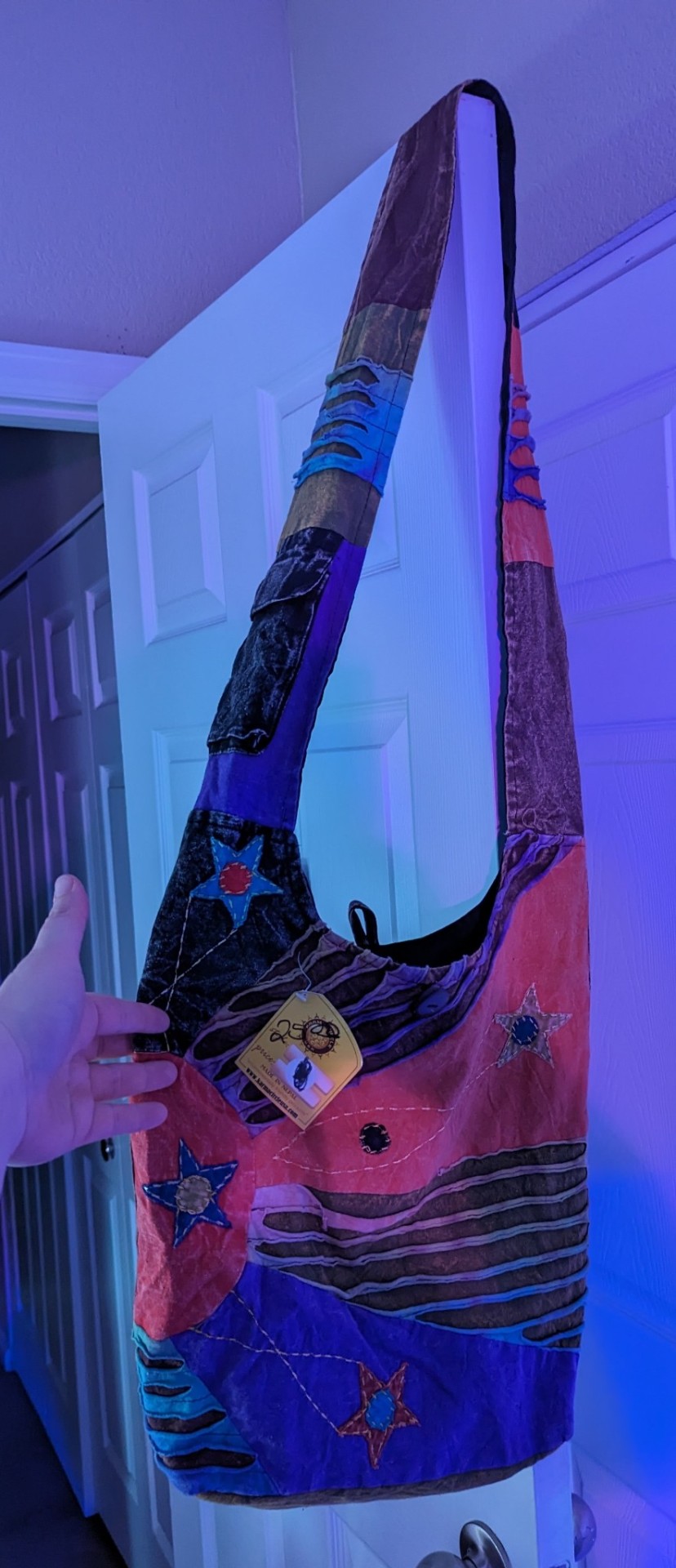

Helaena appears, a prairie girl vision in a modest blue sundress and with her hair tied back with a matching scarf. She reaches into her burlap messenger bag and offers you a choice between a ranch-flavored tuna pouch or a silvery pack of Pop-Tarts. “Strawberry,” she tells you.

“I’ll take the Pop-Tarts.”

Helaena gives them to you and then shakes a bottle of Advil. You’re so groggy it takes you a few seconds to figure out what she wants, then you obediently hold out a hand. Helaena lays two tablets in the center of your palm and moves on, soundlessly like a rabbit or a spider.

You wash the pills down with Snapple. As you nibble half-heartedly on a Pop-Tart—trying not to look at Aemond, multicolored sprinkles falling down onto the carpet—your eyes drift to the tattoo on the underside of Aegon’s forearm. It’s not over ‘til you’re underground. You’ve spotted it before. Only now do you remember where you recognize the lyric from. “Is that Green Day?”

“Yeah,” Aegon says, enthused that you noticed. “Letterbomb.”

“I love that whole album.”

“Me too. I could sing it front to back if you asked me to.”

“I’m not asking.”

Aegon cackles and resumes his Uno game with Rio. Baela is wearing denim shorts and a crop top, slathering her belly with Palmer’s cocoa butter from Walmart as she chats with Rhaena and eats Teddy Grahams. Daeron is waxing the string of his compound bow. Jace is gnawing on a Twizzler as he scrutinizes Aegon’s map, annotated with Xs and circles and arrows in sparkling gel pen green.

“I’m going to be a thousand years old by the time we get there,” Jace mutters.

Aegon hits the table with his fist. The discard pile collapses and cascades, an avalanche of Uno cards. Rio, undisturbed, continues contemplating his next move. “You know what, Jace? The cities are full of zombies, the interstates are blocked by fifty-car pileups, if we bump into anyone else who’s still alive they’re just as likely to rob and murder us as want to be friends, and on top of all that I’m trying to do you the favor of preventing you from getting so irradiated you turn into Spider-Man. If you have a better route in mind, I’d love to hear it.”

“Spider-Man…? You’re such a dumbass, what are you talking about?!”

Luke says from where he stands by a window: “Aemond, someone’s outside.”

“What?” Aemond stares at him. “Zombies?”

“No. People.”

Aemond bolts to the doors, the rest of you close behind him. Rhaena turns off the CD player. You, Rio, and Aegon squeeze together to peer out of one of the windows. There are men—three of them, no, four, all appearing to be in their forties—passing by on the main road through town. They are armed with what are either AR-15s or M16s, you can’t tell which.

Rio whistles. “If you get shot by one of those, the exit wound will be the size of an orange.” Everyone looks at him. This was not an encouraging thing to say.

You elaborate: “Thirty-round magazines. Semiautomatic, assuming they’re AR-15s for civilian use. I guess they could have gotten ahold of M16s somehow. Those have a fully automatic setting.”

“So regardless, we’re out-gunned,” Jace says.

“If they know how to use them. Some men think guns are wall decorations, like deer heads or fish.”

Aegon recoils. “Fish?! What the fuck. I’m glad the colonies left.”

“Maybe they’ll keep walking,” Daeron says hopefully. One of the men stops and points at the bowling alley, saying something to his companions. They laugh and begin crossing the small parking lot. They are less than two minutes from the door. “Oh, great…”

“There’s an emergency exit in the back,” Baela says.

Aegon snorts. “Yeah, that we stacked about twenty boxes of bowling pins in front of to zombie-proof.”

“We won’t be able to get out before they hear us,” Aemond says. Then he abruptly orders: “Grab your guns, let’s go. Helaena, Baela, Rhaena, you’re staying here.” Aemond’s remaining eye—briefly, reluctantly—skates over you as Rio, Aegon, Jace, Luke, and Daeron scatter to obey him. “You too.”

“But I’m the best shot.”

“I don’t want them to know we have women with us.”

“I’m of more use to you outside.”

Aemond rips his Glock out of its holster, pointing it at the floor. His frustration is palpable, an electric shock, heat that refracts light rays until they become mirages on the horizon. “You’re going to stay here, and if a stranger comes through those doors you’re going to kill them. Okay?”

His urgency stuns you; his eye is blue-white summer storm lightning. “Okay.”

“Now get back.”

You soar to the nearest table, duck under it, reach for your Beretta M9 and double-check the clip, fully loaded. You click off the safety.

“Aemond, wait, let me go first,” Aegon is saying by the door. “I’m better at de-escalation, I’m less…uh…intimidating.”

“Less socially incompetent, you mean,” Jace quips.

“I’ll lead,” Aemond insists. “Aegon can talk. Rio, you’re up front with me.”

Rio pumps his Remington 12 gauge. “I’d be delighted.��

Jace is amused. “I’ve been demoted, huh?”

“He’s bigger,” Aemond replies simply, then opens the door and vanishes through a blinding curtain of daylight. The others follow closely; Daeron, the last one out—his compound bow in hand, the strap of his Marlin .22 slung over his shoulder—shuts the door behind him.

Very faintly, you can hear Aegon: “Hey, guys! What’s happening? How’s the apocalypse treating you…?”

Baela, Rhaena, and Helaena are under the table with you. They deserve to have options. You tell them: “If you want to go hide behind the lanes or try to get out the back door, now’s your chance.”

Helaena shakes her head, clutching your t-shirt: black, Star Wars, pawed off a shelf at the Walmart. “I want to stay with you.”

“Same,” Baela says determinedly, gripping her Ruger. She barely knows how to use it, but she’ll try. Rhaena is shaking, her eyes filling up her face, small fragile bones like a bird’s.

You can’t hear voices from outside anymore, but there are no gunshots either. You keep your M9 aimed at the doors, your breathing slow and deep, your heart rate low. Your hands are steady. Your eyes hunt for the slightest movement, for the momentary shadow of someone passing by a window. Against your will, your thoughts wander to Aemond. I hope Aegon is on his left side. Aemond can’t see there.

“Rhaena, get your gun out,” Baela says sharply. “Come on. Turn the safety off. What if you were alone right now? What if we weren’t here to protect you?”

Rhaena nods, fumbling to free her revolver from its holster. “I’m sorry…I’m trying…”

Now there is a stranger’s voice, gruff and deep. He must be just beyond the door, the farthest one to the right. There is a creak of hinges, a sliver of sunlight. “That’s just too damn bad, fellas. You got a nice little hideout here, and you’re gonna have to share it—”

The door opens. Two unfamiliar faces, too shellshocked to raise their rifles in time. You close an eye, line up your sights, fire twice, and that’s all it takes: one headshot, one in the throat, blood like a fountain, spurting scarlet ruin, thuds against the carpet strewn with neon stars, gurgling and spasms as their brains send out those final electrical impulses: danger, catastrophe, apocalypse. Rhaena is screaming. Helaena is covering her ears with both hands.

You run to the doorway; there are more booms of gunfire out in the parking lot. You cross into the late-morning light to see the other two men on the pavement: one with an arrow through the eye, the other with a gaping, hemorrhaging hole where his heart once was. Rio is admiring his work, holding his shotgun aloft. He scoops a handful of Cheddar Whales out of his shorts pocket and shovels them into his mouth.

“Goddamn, I love Remington Arms Company.”

“Oh, that was awesome,” Aegon says, wan and panting, hands on his waist. “Yeah, that was…that was…” He bends over and vomits Snapple and Cool Ranch Doritos onto the asphalt.

“Everyone okay in there?” Rio asks you.

“Yeah.” Behind you, Baela, Rhaena, and Helaena are stepping through the doorway. Your thoughts are whirling sickly: I killed someone. I killed someone. “They wouldn’t leave?”

“We told them the bowling alley was ours,” Aemond says, not looking at you. “We asked them very politely to keep moving. They chose to try to intimidate us into letting them stay. They weren’t good people, and these are the consequences.”

You click on the safety and re-holster your M9. You’re wearing Rio’s on your other hip. They seem to weigh so much more than they did ten minutes ago. I’m not supposed to be a killer. I’m a builder.

“Aegon, are you okay?” Daeron asks, a palm on his brother’s back.

Aegon retches again. “Shut up. You can’t even buy fireworks.”

“Zombies.” Luke is peering through his binoculars. “Not many, just two. Way up the road.”

“There will be more.” Baela’s cradling her belly; you don’t even think she’s aware of it. “They heard the gunshots, the sound carries for miles.”

“We’re leaving,” Aemond says. “Right now. Everyone get your things.”

As backpacks are hastily zipped and Daeron and Aegon stand guard in the parking lot, you kneel down beside the men you murdered and check their rifles. They are M16s, either stolen or illegally purchased: there’s a little switch by the trigger to choose between semi-automatic or the so-called machine gun mode.

“They barely had any bullets left,” you tell Rio. Just like us when we were trapped on that transmission tower.

“Yeah, same story for the other two guys. Four bullets in one magazine, a half dozen in the other. But it only takes once. We don’t have any ammo that will work with M16s, do we?”

“No, we definitely don’t.”

“Fantastic. Well, we’ll throw them in a Walmart cart and take them with us just in case.”

You’re staring down at the man you shot through the head. His eternal resting place is a puddle of blood and brains in a bowling alley in rural Ohio; surely no one deserves that. “He was a real person,” you say, dazed. “Not a zombie. Just a person.”

“Hey.” Rio grabs your shoulders and spins you towards him. From where he is helping Luke gather up the remaining food, Aemond’s head snaps up to watch. “You hurt him before he could hurt us. You did the right thing.”

“Sure.”

“I killed a dude too. I blew his heart right out of his chest. You think I’m going to hell for that?”

“No,” you admit, smiling. “And if you’d be there with me, I guess I wouldn’t mind so much.”

Rio grins, wide and toothy. “Well alright then. Let’s finish packing.”

The ten of you depart from Shenandoah, Ohio heading northwest on Route 603 just like Aegon marked on his map, Jace chauffeuring Baela in one shopping cart, Rio pushing another loaded high with food and M16s.

“It looks like rain,” Helaena says.

Everyone else peers up into a clear, cerulean sky, wondering what she means.

~~~~~~~~~~

You’re a few miles north of Shiloh when the storm rolls in, cold rain and furious wind, daylight that vanishes behind dark churning thunderheads, jagged scars of lightning in an opaque sky. The road is only two lanes, surrounded by fields of wildflowers and ravaged crops and untilled earth; it would look like the patchwork of a quilt if you were gazing down from an airplane, but of course the FAA grounded all flights over a month ago when the world went mad: Revelations, Ragnarök, the fabric of the universe unweaving as death burned through families, cities, nations like a fever, like plague.

“Maybe we should cut across one of these fields,” Jace says, pointing. He is soaked with rain; it drips from his curls, runs into his eyes. Baela is in her cart again; each time she tries to get out and walk, she’s gasping and can’t keep up within half an hour. You’ve all taken turns pushing her, much to Baela’s dismay. She’d be humiliated if she wasn’t too exhausted to keep her eyes open.

“Here, let me do it,” you offer, and Jace gratefully relinquishes the cart. Baela gives you a frail wave of appreciation.

“We stay on the road,” Aemond insists, flinching as rain pelts his scarred face. “Farmhouses have driveways and mailboxes, we’ll pass one eventually. If we lose the road, we might not be able to find it again. We’ll end up wandering around in circles in the woods.”

“Just like the Blair Witch Project,” Aegon says glumly, his Sperry Bahama sneakers audibly soggy.

“There!” Luke announces, spotting something with his binoculars. “Up ahead on the left. Past the bridge.”

You can’t see what Luke does until there is an especially brilliant flash of lightning: a farmhouse, old but seemingly not derelict, and with a number of accompanying buildings, guest houses and stables and barns and towering silos.

“Home sweet home!” Rio says. “And I don’t care if I have to kill a hundred of those undead bastards to get in, it’s mine.”

“Well, hopefully not a hundred,” you reply, in better spirits now that a sanctuary has been found. Aemond keeps glancing back at you as you push Baela’s cart. If he wants to say something, he’s doing a good job of resisting the temptation. “We don’t have that much ammo.”

There is a concrete bridge over a river, probably unremarkable and only five or ten feet deep normally but now torrential with rain. Water rushes by beneath, a muddy incline on each side as the earth rises back up to meet the road. A reflective green sign proclaims that you are only two miles from Plymouth, which Aegon plans to skirt along the edges of. It’s a decent-sized town; he thinks you might be able to find a car to steal there, something with gas in the tank and keys on a hook just inside the house.

“I call the master bedroom,” Jace says craftily, rubbing his palms together. You’re near the center of the bridge now, another ten yards to go. “Nice big bed, warm cozy blankets, and I was up for half of last night keeping watch so tonight I am off duty, I am a free man, it’s going to just be me and my girl and eight glorious uninterrupted hours of sleep—”

Rhaena shrieks, and then you hear it over the noise of the storm, pounding rain and rumbling thunder: moans, growls, hisses like snakes. Not one zombie. A lot more than one. They’re crawling up from under the bridge, from the filthy quagmire at both ends. There was a hoard of them waiting, aimless, dormant, almost hibernating. But now they are awake. They are grasping for you with bony, dirt-covered claws. They are snapping with jaws that leak blood and pus and bile as their organs curdle to a putrid soup.

“Get off the bridge!” Aemond is shouting. He has his Glock in his right hand, a baseball bat in his left. He’ll shoot until he’s out of bullets, and then, and then…

Rio helps you get Baela out of the cart, then opens fire. His Remington doesn’t just pierce skulls, it vaporizes them. When he’s out of shells—there are more in his backpack, but no time to reload—he yanks the M16s out of the other Walmart cart and empties each of them, mowing down zombies as the rest of you scramble across the bridge. All around you are explosions of gunshots, thunder, lightning, zombie skulls crushed by bullets and blunt force trauma. Baela is firing her Ruger as you half-drag her, one arm hooked beneath hers and around her back. When the last M16 is empty, Rio starts clubbing zombies with the butt of it. You’ve all reached the north side of the bridge, except…

“Fuck off, you freaks!” Jace is screaming. They’ve backed him up against the guardrail, a swarm of ten or more. His Remington shotgun is out of ammo; he’s swinging it wildly, but he doesn’t even have enough room to maneuver. There are still more zombies emerging from under the bridge. You can hear them snarling and groaning. You swipe an M9 off your belt and put a bullet in the brain of a zombie as its fingers close around your ankle, then you start picking off the ones mobbing Jace. You aren’t fast enough. As they lean in to bite him, teeth gnashing at the delicious throbbing heat of his jugular, Jace throws himself over the barrier and into the surging water below.

“No!” Baela cries. She careens off the road and into the field, running parallel to the river as swiftly as she can. You are helping her, steadying her, firing at any zombies you have a clear line of sight on. The others are here too: slipping in the muck of the flooding earth, shouting for Jace. He surfaces through the frothing current, flails pitifully, disappears beneath the water again. You glimpse a white hand, a shadow of his dark hair, a kicking shoe. There are more zombies on the opposite side of the river, trailing after Jace, lurching and slobbering viscous, gory saliva. They cannot swim, but they can follow him until he washes ashore.

Jace bursts up through the waves, gasping. “Help! Aemond…Aemond, for the love of God, help me…” He blubbers and then is dragged under. Aemond and Luke are continuing frantically after him. Baela is hysterical, sobbing, trembling with adrenaline. Aegon is yowling as he swings at zombies with his bloodied golf club. Helaena is darting around almost invisibly, always cowering behind Daeron or Aegon or Rio.

You glance north towards the farmhouse, growing not closer but farther away. We can’t leave shelter. We can’t leave the road. You lock eyes with Rio. He’s thinking the same thing.

“Aemond, we have to go,” Rio says, but in the midst of the rain and the turmoil it barely registers.

“Jace, we’re coming to get you!” Aemond swears. The ground is increasingly sodden, deep, difficult to trudge through. Jace resurfaces, coughing and sputtering.

“Jace!” Aegon wails. He caves in the skull of a zombie who was once a registered nurse as Helaena crouches behind him. “Jace, I’m sorry! I’m gonna miss you, man!”

Jace splashes in the rising river, his arms flailing helplessly. He is being swept away far faster than any of you can move on foot. “Aegon, you dumb bitch!” Jace manages, then slips beneath the water and doesn’t reappear.

“Where is he?!” Baela is saying. “Aemond, where…?”

You are trying to soothe her, to bring her back to reality. She was always so pragmatic before; you have to wake her up. “Baela, listen, we can’t stay here, he would want you and the baby to be safe—”

“Aemond! Aemond, we have to go!” Rio catches him, wrenches him around, roars into his face as driving rain pummels them both: “We have to go, or we’re going to die here too!”

It hits Aemond all at once; he understands, horror and agony in his sole blue eye. “We have to go,” he agrees. And then louder, to everyone: “Get to the farmhouse!”

Baela collapses into the mud, howling, tears flooding down her face. “No, he’s still alive, he’s still alive, we can’t leave him!”

You and Rhaena are trying to haul Baela to her feet. Now Aemond is here, pulling you away from her—his fingers tight and urgent around your wrist—as he and Luke take your place. “Go,” he commands. “You run. Don’t wait for us. Rio?”

“I got her,” Rio replies, grabbing your free hand with an iron grip. Gales of wind rip at you; every millimeter of your skin is soaked with rain. As you flee across the fields towards the farmhouse, dozens of zombies pursue you. More are still staggering along the banks of the river, swept up in the hoards chasing Jace and the promise of his waterlogged corpse when it reaches its final destination. Daeron has run out of arrows and is shooting with his .22, which is very much not his preference. Aegon trips, getting covered in mud as he rolls, and Rio stops to help him. While he is distracted, you look back at Aemond. He, Luke, and Baela are moving quickly, but not quickly enough. A drove of zombies is closing in on them. You have a spare few seconds at last. You yank your backpack off, grab a box of ammo inside, and reload your M9.

“Chips?!” Rio calls over his shoulder.

“I’m fine.”

He knows you well enough to listen. The world goes quiet as your finger settles on the trigger. There’s a rhythm one slips into, an impassionate lethal efficiency. It’s easier to keep going than to stop and have to find it again. You fire over and over, dropping eight zombies. You sheath your M9 and whip Rio’s out of your other holster, the sights finding grotesque decaying faces illuminated by lightning. You pull the trigger: blood, bones, brains, corpses jerking and convulsing as they fall harmlessly to the mud. Aemond is here; when did he get here?

“I told you to run!” he’s shouting through the storm, furious. He’s shoving you towards the farmhouse. You resist him.

“Let me kill as many as I can—”

“Go! Now!” Aemond orders over the clashing thunder, and then sprints with you all the way to the front porch to make sure you listen. Everyone else is already there. Helaena has fetched a spare key from under the doormat and is turning it in the lock.

Daeron observes her anxiously. “We don’t know if it’s safe in there, Helaena.”

“Not in,” she says, insistent. “Through.” Through this building, and maybe through the next one too. The average zombie is not terribly clever. If they lose sight of you, without the benefit of the momentum of a hoard they are lost. Helaena opens the door. The living rush inside, and she locks it behind you. As you are bursting out the back door, you can hear zombies pounding their rotting palms against the front one. You soar through a stable full of dead horses and donkeys, leaving the doors open; this should keep the zombies distracted if they make it this far. Then you race to the farthest guest house. Luke, swiveling with his binoculars, spies no zombies approaching as you steal inside. There is no spare key this time; Rio punches out a first-floor window for you to climb through. Once everyone is inside, he and Aegon move a bookshelf to cover the opening.

You all stand in the living room, gasping and shivering, dripping rain down onto the rug and the hardwood floor. The air is dusty but clean of any trace of vile, swampy decay. Outside, thunder booms and lightning flashes bright enough to illuminate the lightless house. The sky is so dark it might as well be nightfall. Baela sinks to her knees, clamping both hands over her mouth so she won’t sob loudly enough for a zombie to hear. Rhaena and Luke are beside her, both weeping quiet rivulets of tears, trying to comfort her in whispers. Helaena is rummaging around searching for candles; she has already taken a lighter out of her soaked burlap messenger bag.

“Daeron, bro, come over here,” Aegon chokes out. He embraces Daeron, clutches him tightly and desperately, doesn’t let go. Rio is reloading his Remington 12 gauge.

Jace is dead. Jace is dead.

Aemond says to you, his voice low but seething: “What the fuck was that?”

You blink the raindrops out of your eyes as you stare at him, bewildered. “You needed help.”

“I told you to run.”

“I’m an asset, I have skills that can keep you alive, why am I here if I’m not going to be useful—?”

“You’re not in the fucking Navy anymore!” he hisses. “When I tell you to run, you run, you don’t stop, you don’t look back, because I can’t worry about you and take care of everyone else.”

“Nobody asked you to worry about me.”

“But I do.”

“Aemond,” Aegon pleads, waving him over. Aegon’s plump sunburned cheeks are glistening with rain and tears. “Man, it doesn’t matter. Nothing else matters now. Please come here.”

“I’m going to clear the house,” Aemond says instead.

Rio raises an eyebrow at you—this is one fucked up guy, Chips—and then pumps his shotgun. “Me too.” He sweeps with Aemond through the main floor and then vanishes up the staircase.

Helaena is lightning candles she found in the kitchen and arranging them around the living room. Daeron starts gathering food from the pantry. Rhaena and Baela are murmuring to each other softly, mournfully. It doesn’t feel like something you should intrude on. Luke is peeking out of a window with his binoculars, vigilant for threats. Aegon sniffles, wanders over to you with large, sad, shimmering eyes, pats your shoulder awkwardly.

“Hey, Chocolate Chip. You doing okay?”

“No,” you answer honestly.

“Yeah. Me either.” Then he flops down on the hideous burnt orange couch and lies there motionless until Daeron brings him a can of Dr. Pepper. Aegon pops the tab, slurps up foam, and then begins singing to himself very quietly, a song so old you can remember your grandfather saying it was one of his favorites as a boy: A Tombstone Every Mile.

When Rio comes back downstairs—heavy footsteps, he can’t help that—you meet him at the bottom of the steps. “The house is good,” Rio says. “And Aemond’s in the big bedroom on the right if you’d like to go up there and talk to him.”

“I don’t think he wants to see me right now.”

“I could not disagree more,” Rio says with a miserable, exhausted smile. Then he goes to the couch to check on Aegon.

You pick up one of the flickering candles, white and scentless, and ascend the staircase. You find Aemond in the master bedroom, the same accommodations that Jace laid claim to when he was still alive. He is sitting at the edge of the bed and staring at the wall, at nothing. Tentatively, you sit down beside him, placing the candle on the nightstand.

“Aemond…what happened to Jace…it wasn’t your fault.”

“Criston said I was in charge, that’s the very last thing he told me. They might be the last words I ever hear from him, and I just…” His voice breaks; he wipes the rain and tears from his face with open palms. “I really wanted to get everyone home.”

“I’m so sorry about what I said at the bowling alley,” you confess, like it’s a dire secret. “I don’t want to fight with you, Aemond, I…I want to help you. I can see what you’ve done for everyone here, me and Rio included, and I believe in you. I want to be a part of this.”

He nods, an acceptance of peace, but he still doesn’t look at you.

“Can we start over? I’ll never bring it up again, okay? I wasn’t trying to guilt you or upset you or anything. I should have just dropped it. I overreacted. And I understand why being with someone like me maybe wouldn’t be…super appealing.”

“It’s not about that.”

“Then what’s it about?”

Aemond wrings his hands, shakes his head, at last turns to you, golden candlelight reflected in his eye, his scar cloaked in shadows. His words are hushed, clandestine, soft powerless surrender. “I’m already so afraid of losing you.”

He cares, he hopes, he wants me too? “I’m here right now, Aemond. I don’t know what else I can say. I’d promise you more if I could.”

He reaches out to touch you, to ghost his thumb across your cheekbone, wet with rain. Then he kisses you, so gently you cannot help but imagine the wispy borders of calm white summer clouds, the rustle of leaves as wind blows down the Appalachian Mountains. You don’t have to ask him what he’s thinking, what it feels like. You can read it in the startled, firelit wonder on his face.

You taste like the beginning of something, here at the end of the world.

#aemond targaryen x reader#aemond x you#aemond targaryen#aemond one eye#aemond x reader#aemond x y/n#aemond targaryen x you#aemond targaryen x y/n

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

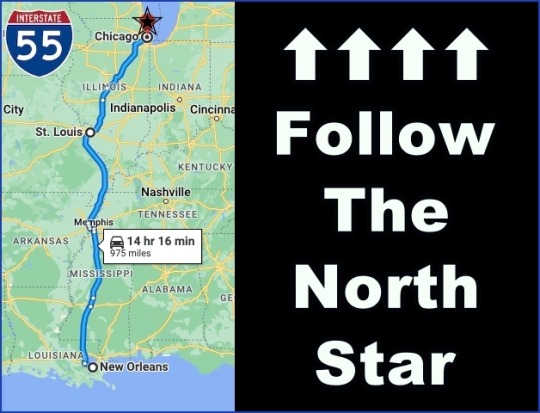

Billboards supporting women seeking abortions are popping up along I-55 heading north

"People make mistakes," says Queen, a Memphis hairstylist whose clients often confide those mistakes in her. [ ... ] Today, Queen says distance has become the biggest hurdle to getting the procedure in the southern United States. Hundreds of miles and multiple state lines can separate women from providers, which is why she's an enthusiastic proponent of a new abortion-rights billboard campaign along one stretch of rural Interstate 55 running across eastern Arkansas from Memphis, Tenn., to Southern Illinois. "Yes!" she shouts when she sees the first billboard, which reads "GOD'S PLAN INCLUDES ABORTION." [ ... ] The new billboard is one of six paid for by Seattle-based Shout Your Abortion. Its founder Amelia Bonow says this route in particular — leading to the only legal providers within hundreds of miles — needed a counterpoint to the billboards opposing abortion. "I-55 is just covered with these hateful, judgmental, shaming, intentionally traumatizing anti-abortion billboards," says Bonow of why the group focused on this segment of highway. Some anti-abortion rights billboards invoke the Bible. Others, like those placed by Minnesota-based Pro-Life Across America, have pictures of smiling babies and a phone number. [ ... ] "That's what these laws do," contends Bonow. "They don't actually stop people from having abortions, but they make people struggle in order to have abortions." Other Shout Your Abortion billboards say "Abortion is okay," and "Abortion is normal, you are loved." Some former abortion providers now offer what are called "navigational services." Ashley Coffield, CEO of Planned Parenthood of Tennessee and North Mississippi, says for some young clients living in poverty it's their first time ever traveling beyond the city limits. "We're handing out gas cards," she says. "We're making hotel arrangements. We're buying plane tickets, train tickets, bus tickets, whatever works best for the individual. We're meeting them where they are."

In the days of slavery Illinois was a North Star of freedom and featured many stops along the Underground Railroad. Since the Dobbs decision it has assumed a somewhat similar role for reproductive freedom.

Interstate 55 runs from New Orleans to Chicago. Illinois is the only state along I-55 which offers reproductive freedom.

Of course it's not necessary to go all the way up to Chicago for healthcare. If you are driving north on I-55, get on I-57 at Sikeston, Missouri and then exit I-57 at Illinois Route 13 westbound to Carbondale. Carbondale is the largest town in the southern tip of Illinois. It has several women's health clinics and a fully staffed hospital. It's also home to Southern Illinois University.

#abortion#i-55#billboards#tennessee#arkansas#missouri#shout your abortion#women's healthcare#a woman's right to choose#reproductive freedom#illinois#roe v. wade#dobbs v. jackson women's health organization#wkno#npr#election 2024

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

RAIDER OF THE LOST ARTS

Jeff Buckley Revisited

by Simeon FlickMarch 2023

Remember me, but oh, forget my fate. ––Henry Purcell, “Dido’s Lament”

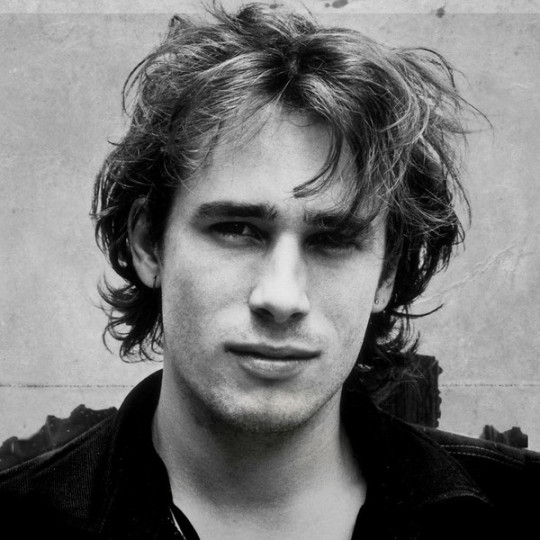

Jeff Buckley

When Jeff Buckley drowned in the Wolf River tributary of the Mississippi on May 29, 1997, just as his band was arriving at the Memphis airport to start helping him finally nail down the long-awaited and already agonized-over second album, music lost not only one of its most singular and revolutionary of raw talents, but also the most mythologized—even during his lifetime—since Kurt Cobain’s death just three years prior. Buckley bore the boon and bane of being the scion of an also semi-famous and ill-fated folk/jazz/soul singer named Tim, and spent his entire life and career—following a single week-long reunion just before Tim’s 1975 death from an accidental heroin overdose—futilely trying to distance himself from the wayward father he never knew apart from the music of nine mostly half-baked studio albums. That an ever-growing number of people, the majority having discovered Jeff’s music post-mortem, feel they know the son better than he or anyone else knew his father, and still feel his loss as acutely as one would a dear family member, is a testament to the unparalleled emotional conveyance and lasting legacy of Jeff’s music despite having released only one official studio album during his lifetime (1994’s hauntingly gorgeous, seamlessly diverse Grace, which has found a home on innumerable “Greatest” lists and has been declared a personal favorite by many of his idols). Jeff Buckley’s influence lives on in the burgeoning underground cult of posthumous acolytes, and in the hyper-emotive, falsetto- and vibrato-laden, multi-octave vocal histrionics of so many subsequent singers, which only seem to come off as pale and obvious allusions that smack more of imitation than assimilation, much less embodiment, and we may never see his like again.

**************

Jeff Buckley entered the world during a meteor shower on the evening of November 17, 1966, the son of an already absent father and a mother, Mary Guibert, who at 18 wasn’t much more than a child herself. Like Cobain, who would arrive only three months later, Jeff had a typical Gen X childhood, replete with divorce, paternal estrangement and maternal domination, often violently reinforced alienation from his formative peers and unstable itinerancy (Mary dragged him through virtually every backwater town in California for all too short stints before he finally put his foot down in Anaheim, where both parents had grown up, and where extended family awaited). The sole refuge, besides the brief but stabilizing presence of the occasional father figure like stepdad Ron Moorhead, was the music men like him turned Jeff onto: Led Zeppelin, Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, and countless others who would seemingly become part of his DNA. Music became his north star, his raison d’être, and when things went wrong, which was all too often (Jeff had to be a rock for flighty mother Mary, taking on too many of her responsibilities too young), he would escape into it for hours.

This would compound once he took up the guitar. Like many children of musicians do, in order to carve out a distinct musical identity (and to maintain a healthy generation gap), Jeff—or Scotty, as he was known by his middle name then––gravitated towards Gen-X’s chosen instrument: the electric guitar, to the exclusion of his mother’s classical piano and his father’s acoustic guitar and vocalizations. Aside from the occasional lead vocal in a high school cover band, mostly for the high-ranged prog-rock and new wave classics none of his other bandmates could pull off, he considered himself just a guitar player in the ’80s. But not just any player; with Al DiMeola as one of many paragons, Jeff threw himself headlong into the world of virtuosic technique, teaching himself complicated licks by ear as he worked diligently to master not just the instrument but music itself.

This trajectory was maintained after his 1984 high school graduation with a stint at the derided Los Angeles organization, MIT (Musician’s Institute of Technology), with its many specialized subsidiaries, including GIT (Guitar Institute of Technology), where Jeff continued his musical edification. After obtaining his virtually useless professional certificate from GIT but with his gun-slinging reputation solidified a year later, he gigged in various area bands and worked as a studio rat, arranging and recording demos for other aspiring artists. But the lead vocalist in him remained as of yet dormant.

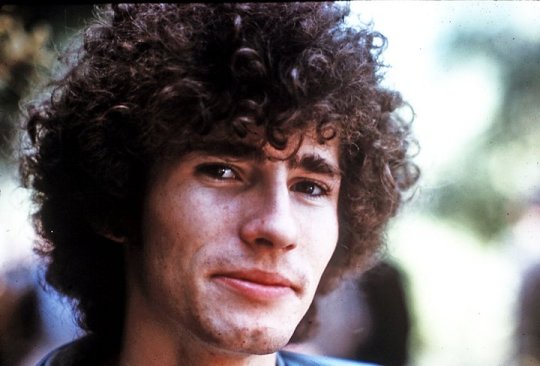

Jeff’s father, Tim Buckley.

By the late ’80s it was already soul-crushingly evident that Los Angeles was a dead-end cesspool of intolerable immersion in other people’s music, and that a drastic change was required to sweep away the bad influences and external white noise to finally get him in touch with his own muse. New York City beckoned—just as it had to Tim in the ’60s—as a locus were people could become the epitome of themselves, get as weird as they wanted, and be unconditionally accepted or ignored as merely part of the scenery, and reach their full, rewarded potential in whatever their chosen field. Jeff tested the waters for a few months in 1990, but his money and options ran out, and he reluctantly returned to Los Angeles.

It wasn’t until April 26, 1991, when he performed as part of the Hal Willner-curated Greetings from Tim Buckley tribute show at Brooklyn’s St. Ann’s Church that he was able to lay the groundwork for a permanent relocation, having garnered the interest of several music industry types offering tangible professional succor, not to mention his first real girlfriend. That night marked the beginning of Jeff’s mythology-building not only as an artist in his own right, but also as an inextricable extension of his father’s legacy; many of the concert’s attendees were blown away not just by Jeff’s supposedly similar voice and delivery, but also by his physical resemblance (apparently there were some eerie backlit cheekbone shadows cast against the church hall walls that heightened the drama).

That there was so much defensiveness and/or mandated avoidance in so many subsequent interviews seems very bite-the-hand-that-feeds, but everyone has to break free from their parents at some point; that it often requires the assistance of those selfsame parents is a frustratingly ironic aspect of adulthood most of us have to face and embrace. Jeff simply had the misfortune of doing it in a highly scrutinized industry with zero—or even negative—expectations or tolerance of rock star progeny. He was also not only abandoned by his father, to whose funeral he was not even invited, but also projected on by Tim-obsessed fans and former love interests expecting the son to deliver on the father’s failed promise(s).

Jeff set up shop, and with the assistance of a demo tape of original songs he had recorded while still languishing in Los Angeles (courtesy of father Tim’s old manager, Herb Cohen), and a threadbare press kit (the only news clipping being a photocopied review of the Tim memorial show), he began beating the Manhattan pavement to drum up gigs and busk on the streets.

As of yet, short on original material, he leaned on sophisticated covers that resonated with his emphatically empathic and emotive spirit as he wall-pasta’d in search of a unique artistic identity. Songs by more recently assimilated influences like Nina Simone, Edith Piaf, and Leonard Cohen stood side by side with pitch-perfect deep-cut gems by Van Morrison and the beloved Zeppelin, with all-inclusive guitar arrangements that cast his different-every-time performances in full-blown Technicolor. His self-accompaniment on electric guitar as opposed to the acoustic form usually favored by the often excessively earnest—if not outright cheesy—solo folk artists of the past (including early-phase Tim), differentiated him from obsolete traditions, and it also broadcast the implicit message that this lone performer would eventually have a band behind him.

But the comprehensive guitar skill was just a tripod for the potent weapon his voice was becoming.

It’s difficult for most laypeople to differentiate between learned technique and natural timbre. Jeff didn’t inherit his father’s vocal gift; his was high-ranged and effeminate instead, with a thick palate and some huskiness occasionally muddying up his tone production. But what he did with it despite or because of the confines of those “limitations” is absolutely astounding. Instead of self-consciously diluting his delivery, he threw the book at it, almost as a diversionary tactic, like a magician smoke-and-mirror distracting his audience from an otherwise debunkable prestige move. With his uncanny imitative abilities and concomitant penchant for self-pedagogy, he adopted a rapid vibrato in accordance with essential influences (Simone, Piaf, Garland, and even father Tim, as was his undeniable birthright), nicked tricky classical and R&B trills and phrasing, turned his angelic upper register into a strength by frequently, often breathily leaning into his falsetto, incorporated various operatic (chromatic glissandos) and jazz (scatting) effects, learned how to push a full chest voice into his higher register like Robert Plant (and Tim) and to raggedly scream like Cobain and others of his generation. He ran sustain drills as he traveled across the city in cabs or on foot, drawing out his notes as long as possible to hone his deftly rationed breath support (just try holding out along with the 25-second E4 at the end of Grace’s “Hallelujah”). Tim had set the bar high for the younger Buckley, and Jeff rose mightily to the challenge, developing a comprehensive technique that kept pace with his guitar mastery, which had been pared down to unassailable jazz progressions and Hendrixian blues tropes and, like Cobain, would feature downplayed––if any––solos for the duration. If Jeff’s musical continuo was a haunted house, his voice had become the ghost that lingered within it.

(There’s something more compelling about the resulting output of singer/songwriters who start out exclusively as instrumentalists; it makes for more effective and meaningful musical accompaniment and better structured songs, and they tend to work more diligently and eruditely at mastering vocal technique. Tim leaned almost exclusively on his phenomenal voice, and insufficient thought was given to structure and harmony in his songs, and the lyrics were by turns predominantly unremarkable or unwieldy, the main drawback of being able to sing the phonebook. The resulting chord changes and accompaniment were more limited, derivative, yet ironically more obtrusive. Jeff had harnessed hooks, vivid and compelling lyrical imagery, and upper harmony into underlying works that left room for everything important, but especially the vocals. Thus, Jeff managed to achieve with one album what Tim failed to do in nine; he produced a timeless classic.)

Jeff’s most crucial influence––his self-declared Elvis––was the Qawwali singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. Qawwali singing introduced Jeff not only to its mystical eastern harmony, which was a subtle but unmistakable undercurrent in his guitar parts and his music in general, but also to a highly freeing ilk of vocal improvisation he would use to sparing but profound effect in his live performances, most notably in his wordless vocal warm-ups for things like “Mojo Pin” and “Dream Brother,” and in the way he would subtly tweak the songs’ melodies from show to show.

With all of this gelling within and beginning to burst out of him, Jeff flogged his wares at many a Manhattan venue, but he would find his symbiotic Shangri La at Sin-é, a hole-in-the-wall café run by a fellow man of Irish descent, ex-pat Shane Doyle. Jeff crystalized into the self-accompanying male diva he had been striving to become there at Sin-é and found a home away from home not only on the small stage, where he reveled in an unparalleled, as-of-yet anonymous freedom within the material, but also behind the counter, where he could often be found washing dishes.

This is where Jeff’s buzz began to build, thanks to his Monday night residency, the impression he had made on the industry folk at Tim’s memorial concert (including several Columbia employees who started showing up on the regular), and the steadily growing crowds comprised predominantly of young women. As word of mouth spread and audiences began to overflow onto the sidewalk, the higher-ups at several major labels started circling to investigate the fresh blood in the water. A hilarious bidding war ensued, with record company execs actually trying to make table reservations at the tiny walk-in café, and the street’s curbs clogging with limousines. Jeff would end up signing with Columbia, a Sony subsidiary that was home to many of his heroes, and that made all the right overtures and promises to this hot young talent who was desperately intent on accomplishing the impossible feat of using and defeating the music industry from the inside, as opposed to being consumed by it like his father had been.

**************

Jeff’s “million dollar” deal––consisting of a $100,000 advance, a higher than normal royalty rate, and a three-album guarantee––was unusual for a solo artist of that time, considering there were scant few original songs, no band, and no official demo tape to speak of (the L.A. recordings, which Jeff in his humorously nihilistic cups had dubbed The Babylon Dungeon Sessions, technically fulfilled the applicable criteria but weren’t aurally suitable). Columbia knew they had a hot property on their hands, the Gen-X manifestation of a Dylan or Springsteen-esque heritage artist, and Jeff made sure they knew, mostly through intentional late arrivals to countless business meetings. But because his talents spanned so deep and wide, everyone was initially at a loss as to what form his recorded output should take. What the hell do you do with an artist that has the chops and versatility to go in any direction??

The logical first step was to try and capture the solo version of Jeff on tape and issue it as a soft introduction. Live At Sin-é was culled from two performances recorded during the summer of 1993 and released on November 23 as a perfunctory, slightly disappointing four-song EP consisting of two originals (“Mojo Pin,” and “Eternal Life,” both of which would get definitive, full-band versions on Grace), and two covers (a rhapsodically incendiary rendition of Van Morrison’s “The Way Young Lovers Do” and a transcendent reading of Edith Piaf’s “Je N’en Connais Pas La Fin,” complete with a fingerpicked merry-go-round guitar waltz for the French-sung refrain).

In Columbia’s posthumous ambition to exploit remaining vault caches to continue paying down Jeff’s sizable debt to the label, the original release’s felonious dearth was rectified with 2003’s Legacy Edition, a two-disc, one DVD set that was a much more complete representation of Jeff not just as an artist during that pre-fame period, but as a person. Along with scads more songs from the same shows, the expanded set includes between-song banter that manages to do what his scant, more visceral studio work couldn’t: put his pronouncedly nerdy, madcap, sometimes salacious sense of humor on full display.

Meanwhile, Jeff had also begun working toward his only completed studio LP. Sony had brought him in to record the lion’s share of his repertoire in February of ’93 as a way to gently kick off the A&R cataloguing and selection process for the album (these were later released as part of the 2016 compilation You And I), and recording sessions were scheduled for September at Bearsville Studios, which was located near Woodstock in upstate New York. The only problem––and it was a big one––was that he didn’t have a band. Like so many other aspects of Jeff’s career, this got rectified at the last possible moment; he met and connected with bassist Mick Grondahl first, then drummer Matt Johnson less than a month out from the initial recording dates.

A tall, dark, and handsome Dane, Grondahl had an ideal combination of low-key receptiveness and musical adventurousness that allowed him to be the perfect on- and offstage wingman: he was interesting in an unobtrusive way. Johnson was a wet-eared Texan who had the ideal balance of power and precision (a slight and diminutive presence, Johnson’s physicality was bolstered by his construction day job) and the breadth of taste and experience to match the extreme dynamic variations of Jeff’s sonic palette (Johnson could crush it like Bonzo or play pindrop-soft like a seasoned jazz pro––whatever the music required).

Columbia was less than pleased that Jeff had recruited a rhythm section with virtually no stage or studio experience, but he would eventually be proven right in his selection of introverted, lump-of-clay rookies that doubled as a gang of friends who could hang with him in every sense, especially through all the spontaneous twists and turns he threw at them. This was one of many battles he would actually win for the better against Sony, though he would initially come off as the loser (it took a few months for the band to get up to speed on the Grace repertoire, because they rarely if ever played the album’s songs during rehearsals or soundchecks, preferring to fill that time with “jamming,” since they needed to build an intuitive rapport. They also knew they would be playing the same emotionally demanding songs night after night for the next year or two).

The trio began work on Grace at Bearsville Studios, which had been pre-rigged with several different recording environments to spontaneously capture whatever came out of Jeff and his band in any permutation and style, whether it was solo, low-key jazz combo or full-on rock group. Andy Wallace, who had dialed in the mixes for Nirvana’s Nevermind, wore the coproducing and engineering hats for these sessions, along with providing a regimented lens through which to focus and refract Jeff’s chaotic genius. Recording proceeded slowly and steadily, without too much fanfare, but then, again at the last minute there was an explosion of prodigious productivity. Among other developments, German vibraphone prodigy Karl Berger was in town, and with the assistance of a local quartet, he and Jeff co-arranged string parts for “Grace,” “Last Goodbye,” and “Eternal Life.”

The eleventh-hour burst of creativity suddenly began transforming Jeff’s modest debut into something more akin to the fully produced masterpiece that usually doesn’t happen until later in a discography. More studio time was booked for intensive overdubbing of additional layers, which pushed costs beyond the initial budget, and though Columbia held Jeff in high esteem and generally handled him with kid gloves (full artistic control was implicit), the majority of expenses went into his recoupable fund, which had to be paid down by Jeff through album sale royalties. Though Grace would eventually prove itself beyond worthy of the investment, this was one of the first major manifestations of Jeff’s Sony-sourced headache that would plague him for the duration.

Grace, which was finally released on August 23, 1994, tends to vex the neophyte at first blush. There’s so much to unpack, the resulting bottleneck can be off-putting. Only through repeated listens will it reward those who “wait in the fire,” as the title track has it. Once that rote assimilation has inured you to Jeff’s eccentric voice and anachronistically innovative affectations, and Grace has dilated your emotional receptivity wider than you ever thought possible, you will tend to listen obsessively for a while before you realize you need to take a break so your strung-out, wrung-out heart can snap back to normal. You will probably only be able to listen to it every once in a while thereafter, as the lachrymose music makes demands of your psyche that require exceptional equanimity to withstand (the irony is that while Grace might help you grieve a breakup or death, listening to its ten tracks can also exhume that grief long past the time you have worked through it). The fact that Jeff is no longer here but still sounds undeniably alive in the speakers, and that the making of this album led to insurmountable expectations for a satisfactory follow-up that added to his pre-death stress, only augments the album’s haunting intensity.

The sonic progeny of Robert Johnson, Nina Simone, Edgar Allan Poe, and John Dowland, Jeff comes off as the wide-amplitude, tragic-romantic, card-carrying Scorpio that he was, irresistibly obsessed with love and death, singing often of the moon and rain (and yet also of burning and fire), and bedroom-as-sanctuary-and-wellspring, and a melancholic, nearly heart-rending yearning for absent lovers past and present. All of this can’t help but feed into his steadily growing mythology, not to mention strike he’s-all-alone-and-vulnerable-go-save-him reverberations of longing through the heartstrings of every heterosexual female within earshot, while also getting straight men of all walks gratefully as in touch with their feminine side as he was. In the age of grunge––which force-fed emotion through intimidating volume and distortion––Grace was an anomaly, delivering a wider range of feeling through a listener’s induced surrender to its heightened peaks and valleys, with Jeff’s by turns angelic and demonic voice keeping pace, and, unlike Cobain, with absolutely no irony to lean on, hide behind, or use as disclaimer.

“Mojo Pin” is the perfect overture for an audiophile quality album with such wide yet still somehow cohesive style and dynamic oscillations, with softly looping guitar harmonics fading in, followed by a wordless melody delicately sung over a fingerpicked folk/jazz guitar pattern. The music rollercoasters from there, with dramatic stops featuring vocal melismas that proceed into straight 4/4 time, finally crescendoing in a loud, climactic buildup, and a ragged scream from Jeff that tapers seamlessly back into the jazz feel.

The first stanzas tell us so much about the author:

I’m lying in my bed, the blanket is warm This body will never be safe from harm Still feel your hair, black ribbons of coal Touch my skin to keep me whole

Oh, if only you’d come back to me If you laid at my side I wouldn’t need no mojo pin To keep me satisfied

Here we find a vividly lovelorn artist who tends to compose from the subconscious (as with many of his original songs, “Mojo Pin” was inspired by a dream he had had) has already begun confronting his mortality, equates love with addiction like so many troubadours before him (“mojo pin” is a euphemism for a shot of heroin, which, inspired in part by his father, Jeff used for a short time during the tour in support of Grace), and feels hopelessly separated from it all, with a heightened sense of longing that can’t help but garner the listener’s sympathies.

The title track picks up the thread in more ways than one; along with “Mojo Pin” it is the second of two pre-Sony songwriting collaborations with former Captain Beefheart guitarist Gary Lucas—as part of his short-lived Gods and Monsters project (that’s Lucas’s guitar-noodle wizardry on both). And with lines like “Oh, drink a bit of wine––we both might go tomorrow,” it ups the mortality-as-enabler-and-aphrodisiac ante.

With its churning 6/8 groove, and with Jeff starting the song in typical fashion––toward the bottom of his discernable vocal range (D3), “Grace” culminates cathartically on a sustained, heavily vibrato’d, full-chest E5 bad-assedly blasting from his manic larynx and also marks the first of several ominous allusions to being harmed by water (“…And I feel them drown my name…”).

“Last Goodbye” was supposed to be the big first single. It even got an MTV video treatment (just look at his dour expression as he and the exhausted band take a precious day off from a European tour to do this exorbitantly expensive production of a compromised artistic concept in a despised medium), but with no real chorus to speak of, its chart success was modest at best. A Delta blues slide glides across an open-tuned electric 12-string guitar before dropping into a mid-tempo dance groove and a lyric full of bittersweet memories of a failed relationship with an older woman in L.A.

Not only was Jeff a bit shorthanded when it came to filling an entire 52-minute album with originals, but it also would have been a shame not to round out the running order with some well-chosen and interpreted covers in emulation of the intimate immediacy of Jeff’s Sin-é days. The first of these appearing on Grace is “Lilac Wine,” a torch-song standard written by James Shelton and adopted by Nina Simone. Jeff gives the distant-lover-as-intoxicant lyrics the hyper-emotive treatment, with perfectly sustained vibrato on the drawn-out notes and with his voice occasionally breaking into a heartrending sob, especially on the line, “…Isn’t that she, or am I just going crazy, dear?”

“Lilac Wine” is a significant indication of the barely fathomable depth of Jeff’s––and by extension, the band’s––versatility and their ability to do exactly right by the artist and repertoire (it’s difficult, in that sense, to listen to any of Tim’s records without taking umbrage with the musicians in the various band incarnations smothering Tim’s voice and stepping all over his 12-string guitar with their ego-fulfilling and poorly––if at all––thought-out parts).

“So Real” represents not only the successful search for a second guitarist, but also a tenacious battle fought and won against Columbia for the very soul of the album.

Michael Tighe, a mutual friend of Jeff and his ex Rebecca Moore (the one he had met and fallen in love with at the Tim tribute, and whom “Grace”s lyrics supposedly feature) joined the band on second guitar after most of the work on the album had been completed, and he brought an intriguing set of chord changes with him. When it came time to record B-sides and possible non-album singles (a cover of Big Star’s “Kangaroo”, which, to Sony’s consternation would often stretch out to 15 or 20 minutes in concert, was also laid down), Tighe’s progressions, which were inordinately sophisticated considering he hadn’t been playing guitar for very long, were dusted off, tracked with engineer Cliff Norrell, and Jeff did the lead vocal in one take after a last-minute walk to finish the lyric.

Distinguished by the verses’ seamless changes in meter (back and forth from duple to triple time), its by-now standard mélange of tragic-romantic imagery in the lyrics (“I love you / But I’m afraid to love you,” and the foreboding “And I couldn’t awake from the nightmare that sucked me in and pulled me under…”), another wildly climactic E5 at the end, and a massive chorus hook, the song fit Jeff’s MO––accessible innovation and wide-amplitude expression––perfectly.

So much so that it quickly shed its B-side status and usurped a coveted spot on the record from another, highly contested original: The excessively personal and harsh “Forget Her,” which in retrospect would have been the sole manifestation of irony on the album. Jeff was justifiably dissatisfied with this disingenuously caustic 12/8 blues-pop dirge waltz he had allegedly penned about the aforementioned, hapless Moore, upon whom the lyric displaced Jeff’s own culpability for the relationship’s dissolution. But the label was head over heels with it, as the song’s melodramatic, Michael Bolton-esque chorus made it the one and only potential crossover smash in their minds. Columbia exec Don Ienner, who was essentially Jeff’s boss, tried everything short of bribery to futilely sweet-talk Jeff into keeping it on the album, which, in itself, was a tangible reason for Jeff to dig in, though he also feared that the slightly smarmy song would be a one-way ticket to One-Hit-Wonder-ville. As it turned out, “So Real”s chorus was hookier anyway, enough to warrant its own video treatment, though its subsequent commercial impact was also negligible.

A plaintive sigh kicks off what is now widely regarded as the definitive recording of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” the second cover of the album, performed solo and glued together from multiple takes into a solemn paean to the ecstatic pain of long-term relationships. Inspired by John Cale’s 1991 reading, Jeff sticks to the ultra-romantic verses that find love and suffering linked in paradox, and the guitar tone and reverb augment the song’s church hymn vibe, almost as though it was recorded at a service or funeral. If you’ve heard this recording or noticed it in myriad movies and TV shows and haven’t cried at least once, you’re not human.

“Lover, You Should Have Come Over” is a classic swinging blues adagio, perhaps the best known and most covered original on the album. Water and death are linked once again (“Looking out the door, I see the rain fall upon the funeral mourners / Parading in a wake of sad relations as their shoes fill up with water…”), and then Jeff abruptly breaks that train of thought to do right by Moore in recognizing his role in their breakup (“…Maybe I’m too young / To keep good love from going wrong”). Again, his vocal starts low and builds to another E5 at the end. In the hands of another artist, all of this would have sounded forced and over the top, but somehow Jeff was able to make it work. That’s his genius/madness; he himself was fully dilated and committed in a way that wasn’t healthy or sustainable, but damn, did it make for visceral listening.

“Corpus Christi Carol” reaches even further back than 1950’s “Lilac Wine” and completely blows the listener away with its expectation-defying display of musical depth. He becomes a bona fide classical singer here, exhibiting total immersion in the anonymous 16th-century lyric that the aptly named English composer Benjamin Britten incorporated into 1933’s Choral Variations for Mixed Voices (“A Boy Was Born”), Op. 3, finally arriving at Jeff’s adolescent ears through the version for high voice recorded by Janet Baker in 1967. Jeff completely inhabits the allegory of a bedridden, Christ-like knight endlessly bleeding, witnessed by love and the purity of his cause, with the empathic delicacy that was already his trademark. The stark arrangement for electric guitar and scant overdubs is superbly matched by the lamenting vocal, which ends on a ghostly, falsetto’d E5 that is utterly cathartic in its climactic glory.

Jeff wanted to make an album that compelled rock fans to forget about Zeppelin II, and “Eternal Life” delivers on the heavier side of that promise. Written during his time in L.A., the creepy intro stops on a dime before a bludgeoning, yet highly danceable groove drops in and a reactive lyric confronts applicable listeners to wake up and smell the mortal coffee:

Eternal life is now on my trail Got my red-glitter coffin, man––just need one last nail While all these ugly gentlemen play out their foolish games There’s a flaming red horizon that screams our names…

Racist everyman, what have you done? Man, you made a killer of your unborn son Oh, crown my fear your king at the point of a gun All I want to do is love everyone…

There’s no time for hatred––only questions What is love, where is happiness What is alive, where is peace? When will I find the strength to bring me release?

With distorted bass as well as guitar alongside complementary strings and a killer groove featuring a highly effective, accelerating hi-hat pattern from Johnson on the verses, the song successfully proselytizes for universally incontestable causes, and reinforces Jeff’s projected mythology as a doomed soul whose seemingly relished fate awaits him sooner rather than later.

“Dream Brother” may be the last song on the album, but it was the very first idea Jeff and the band had worked up together. At the risk of overusing the word, and just like the album as a whole, it is haunting from start to finish, with a droney, string-cranking intro giving way to an eastern-inflected guitar motif. Jeff’s more static but no less sublime vocal melody goes beyond complementary; it builds tension by hanging on or around the fifth for most of the verse stanzas before resolving to the tonic on the last note of the phrase. Grondahl’s bass line, as with all his work on the album, is a sublime treat; here we find him working his way through the exotic Phrygian mode, recasting the guitar parts into a harmonically complex, emotionally compelling accompaniment that perfectly underpins the vocal.

The song features another penned-and-sung-at-the-last-possible-minute lyric, the chorus of which admonishes dear L.A. friend Chris Dowd (of Fishbone) not to abandon his new family like Tim had Jeff and Mary: “Don’t be like the one who made me so old / Don’t be like the one who left behind his name / ‘Cause they’re waiting for you like I waited for mine / And nobody ever came.” Grace’s only allusion to Jeff’s father builds in intensity to an instrumental bridge with wordless Qawwali wailings that are utterly bone chilling in their echoing-into-eternity saturation. The album’s final line puts an ominous capstone on the pyramid of the untimely-death-by-water preoccupation: “Asleep in the sand, with the ocean washing over…”

PART TWO

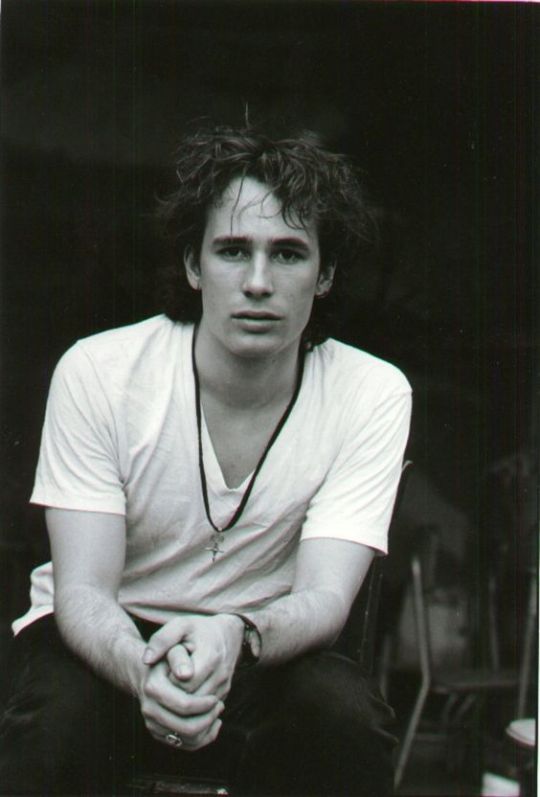

Jeff Buckley

From ’94 to ’96, both solo and with the band, Jeff Buckley toured the world and elsewhere. Those two years were highly transformative; he met and/or was lauded by so many of his personal heroes (including Zeppelin’s Page and Plant, Paul and Linda McCartney, U2’s Bono and The Edge, David Bowie, and he had a brief affair with Elizabeth Fraser of Cocteau Twins and This Mortal Coil, who had covered Tim’s “Song to the Siren” [for aural proof of the romance, go to YouTube and check out their unfinished, embarrassingly smitten PDA duet on “All Flowers in Time”]), picked up an all but unshakeable smoking habit as a late-blooming extension of delayed formative-year rebellion and as a temporary, self-harming relief from the stresses of touring and just-shy-of-A-list fame (he managed to make People magazine’s 50 most beautiful list in May of ’95, which mostly appalled him, and also had an eye-opening night out with Courtney Love), turned down numerous primetime opportunities—SNL, Letterman, and acting roles and commercial placements—in favor of “underground” platforms like MTV’s “120 Minutes,” and was constantly at odds with his record label.

Australia and France embraced him like a returning hero, with the latter country’s Académie Charles Cros presenting Jeff with the rarely-awarded-to-an-American Grand Prix International Du Disque in honor of Grace on April 13, 1995 (two live shows, the second representing a career peak, were recorded during a French leg of the tour and later released as 1995’s Live at the Bataclan EP and 2001’s Live à l’Olympia).

The tank ran dry on March 1, 1996, which marked not only the final date of a hastily booked Australian/New Zealand tour to capitalize on Jeff’s surging popularity there and subsequently the last in official support of Grace, but also the final show with percussionist Matt Johnson, who had reached his hard limit with the band leader’s exacerbated lifestyle excesses and reckless behavior, not to mention Jeff’s escalating hazing of him.

Drummerless and exhausted, a different Jeff Buckley returned to a different New York. Though it suited his dysfunctionally nomadic, reactively noncommittal spirit, touring is not conducive to one’s mental or physical well-being nor is any level of fame, which is unfortunately what moves the units at the cost of anonymous normalcy. As a result, Jeff could no longer frequent any of his old haunts without being recognized and approached by strangers who thought they knew and deserved a piece of him beyond his timeless music. But then even his friends couldn’t help but feel jilted in their wanting a less ephemeral friendship with him, as he made them feel like the undeniably corroborated center of the universe when he was around, having given of himself interpersonally as completely and unadvisedly as he did in his music.

With inchoate fame now cutting him off from his usual decompression options, Jeff couldn’t recharge his psychic batteries. That coupled with the fact that Columbia and the press had been persistently hounding him regarding a follow-up to Grace piled even more pressure on the stress heap, further hampering his creative process and making The Big Apple taste more of the cyanide within the seeds than the once novel fruit of clandestine self-discovery.

There’s an industry saying: a recording artist has their entire life to make the first album and six months to make the second. Already no stranger to writer’s block under normal circumstances (he was inherently a better interpreter than a composer and understandably loath to commit to locked-in versions of anything), Jeff found himself hitting the creative wall in the midst of his increasingly stifling paradigm. The new songs were coming, albeit more slowly than everyone preferred, and in a different, more current vein than Grace. Having kept an ever-vigilant ear to the cultural ground, Jeff had met the Grifters and the Dambuilders while on tour, gaining a new love interest—Joan Wasser, to whom he related early on that he was going to die young—from the latter band and befriended Nathan Larson of Shudder to Think, and their contemporary alternative rock vibes ignited a light bulb over Jeff’s head, giving him the inspiration to pursue a rawer sound, much as Cobain had for Nevermind’s 1993 follow-up—In Utero.

It wasn’t necessarily Sony’s cup of tea. Though the label was by no means dead-set on putting out Son of Grace, they were a bit befuddled by the significant shift in musical mores away from the classic heritage artist sound toward the aural marriage of the Smiths and Soundgarden evident in the newer material. His sagacious selection of classic solo repertoire, and Grace by extension, had gotten Jeff’s foot in the door, as their sophisticated old-school values were arguably a premeditated affectation on Jeff’s part to woo the industry’s boho Boomer gatekeepers into signing and unconditionally supporting him. Now that he was more or less ensconced on the inside, and having gained more than a little leverage from all the hard work of the past year and a half, Jeff wanted to change things up to reflect more of what he’d been listening to and writing as an artist of his own generation. Though jumping high through Jeff’s hoops was by now second nature, Columbia was nevertheless befuddled.

This vexation next manifested as bewilderment over the choice of legendary Television alum Tom Verlaine (RIP) to aid and abet his alt-rock vision as the inexperienced coproducer for the second album. No one at Sony thought Verlaine was the right man for the job; they would just as soon have gone with Andy Wallace again rather than someone who, as with Grondahl, Johnson, and Tighe, didn’t have a track record to speak of. Whether or not Jeff’s choice was ill informed was irrelevant; it became his new crusade against the label, a pyrrhic war waged solely on the principle of getting his way even if it ended up biting him in the ass.

Columbia green-lit some bet-hedging recording with Verlaine to humor Jeff, but also to surreptitiously gather leverage as a failed, debt-enlarging investment, as the odds were slim that he could pull another rabbit out of his hat within the limited, impossible-for-Jeff parameters. Two brief as they were dissatisfying sessions occurred at various New York studios in 1996 and then a third at Memphis’s Easley McCain studios with Johnson’s permanent replacement, Parker Kindred, in early 1997. Jeff had become interested in recording at Easley through Grifters guitarist and Memphis resident Dave Shouse, and in relocating to that hallowed town for its legendary status in the history of blues and rock ‘n roll, and yet also as an escape from the lost anonymity, label pressure, and detrimental distractions of New York.